Abstract

Shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, the American government impressed upon the media industry and corporate advertising the cooperative need to boost morale and enlist nationalist support for the war effort. Public opinion was shaped through an active campaign of visual propaganda and media censorship in which the social trauma of war, in particular, representations of death and destructive disorder, was erased from official news reports. However, avant-garde art and writing in View magazine during the early 1940s can be analyzed as a radical form of counter-discourse that challenged the media’s representation of the war. View had been founded in 1940 by the poet Charles Henri Ford, who vowed to create a magazine devoted to what he called the “new journalism”, a form of international reporting by poets and visual artists that would provide visionary critical insight on the forthcoming political catastrophe in Europe. Lacking their own publishing forum, a number of Surrealist émigrés and American adherents of Surrealism gravitated towards View. As this article will examine, Surrealist imagery and prose in View evoked a profound sense of the bodily trauma and physical destruction omitted from mass media, subverting the government’s highly sanitized and ideologically manipulated representations of World War II.

1. Introduction

View magazine had been founded in 1940 by the American poet Charles Henri Ford, who had fled Europe in 1939 when Germany invaded Poland. Upon returning to the United States, he vowed to create a vanguard journal devoted to what he called “the new journalism”, a form of international reporting by poets and visual artists that would provide visionary critical insight on the forthcoming political catastrophe in Europe. Lacking their own publishing forum in the early forties, a large number of Surrealist émigrés and younger American adherents of Surrealism gravitated towards View. Shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, the American government impressed upon the media industry and corporate advertising the cooperative need to boost morale and enlist nationalist support for the war effort. Public opinion was shaped through an active campaign in which the social trauma of war, in particular, representations of death and destructive disorder, was erased from official news reports and other forms of mass media. However, as this article will examine, Surrealist art and writing that appeared in View can be analyzed as a radical form of counter-discourse that challenged the visual propaganda and media censorship of World War II.

With the exception of the recent exhibit “Monsters & Myths: Surrealism and War in the 1930s and 1940s,” the scholarship on Surrealism and war has largely focused on the Surrealists’ response to World War I (Shell and Tostman 2018; Stich 1990; Lyford 2007). In many respects, the psychological concerns and symbolic themes within the early Surrealist movement had been directly shaped by the psychic traumas of this wartime experience. One of the major socio-cultural developments of the Second World War was the massive expansion of commercial media, which was used to dispense information to an American public eager for news on the war. In contrast to the direct involvement of many Surrealists in World War I, the majority of exiled Surrealists in the United States had only perceived the later conflict through news reports and visual propaganda circulated on the home front. However, no study has attempted to analyze the artistic and ideological response of the Surrealists to the mass visual culture of World War II. This is a crucial issue in light of Paul Fussell’s argument on the burgeoning power of media in the 1940s to determine the perception of reality within American wartime culture (Fussell 1989, p. 165). Moreover, despite the prevalence in View of Surrealist imagery and writing about the war, there has been virtually no research on the role of the magazine as a radical forum for political dissent against the war or the media’s representation of the conflict.

2. War Propaganda and Strategies of Media Censorship

Censorship of the American press actually began before the United States’ official entry into the war. Roosevelt declared the need to protect highly sensitive military information as early as 1939 and established the Censorship Branch in the Military Intelligence Division in June of 1941. With the onset of American involvement in the war, the government created official agencies to monitor what images and reports on the conflict were presented through the news and entertainment media. Due to their powerful emotional and visceral impact, visual images were more strictly censored than written commentary (Tashjian 1996, p. 722). While propaganda in WWI had taught the government that Americans were skeptical of overly idealized images of war, it was also feared that graphic representations of military losses and combat deaths would incite the public to demand an early end to the war. The Office of War Information was formed in June 1942 as the chief propaganda agency that was responsible for coordinating the official release of war images. War correspondents had to submit their film to field censors, who then sent the classified photographs to Washington D.C., where they were subjected to further review by the War Department’s Bureau of Public Relations before being approved for media distribution. The most graphic images were relegated to a secret file unofficially labeled “the chamber of horrors” that was housed in the newly-created Pentagon. Censorship was defended by the government as a means to enforce expansive security measures to protect military information and ensure the safety of troops and civilian populations. In actuality, it was seen as beneficial to American morale to withhold information on demoralizing wartime realities and appeal to the nation’s patriotic support through propaganda campaigns for silence, social unity, economic frugality, and disciplined production on the home front (Roeder 1993, p. 10). As Roeder stressed, the news media “could document the meaningful sacrifices that Americans made for the larger cause, …but (it) could not demonstrate how thoroughly war could disorder—rip asunder—their individual lives and bodies” (Roeder 1996, p. 59).

Rather than bombard citizens with blatantly patriotic forms of visual propaganda, the government’s media policies focused more extensively on varied strategies of censorship. Although the Office of War Information had pledged a policy of truthful reporting and openness, the new morale culture carefully orchestrated a selective release of photographs that suppressed and erased from public perception any images of the conflict that depicted extreme forms of military violence and disorder, which potentially could have induced a pervasive anxiety and undermined American confidence in striving for military victory (Casey 2014, p. 57). This informational vacuum was filled instead by visual reportage on the war that sought to demonize the Axis enemies by contrasting the heroic goodwill and controlled discipline of American soldiers with the irrational brutality and bestiality of Japanese and German troops. For the first twenty-one months of the war, it was prohibited to publish any images of American war casualties and, throughout the conflict, the government sought to suppress photographs of soldiers maimed in combat, as well as troops suffering from the psychic traumas of war. Moreover, it banned any images of victims of allied bombing raids and U.S. chemical warfare experiments. Despite the disruptive and unpredictable forces of global war, the ideological effect of this media censorship was to construct illusions of control, assuring Americans of maintaining the normalcy, stability, and rational social order of home front life (Roeder 1996, p. 48). Within Roosevelt’s administration, definitions of public morale included personal values for maintaining this stable home front society, such as steady self-control, determined conduct. and a resolute and confident spirit (Fussell 1989, p. 143). In providing this overview of censorship strategies, it is important to note John Whiteclay Chambers’ observation that the power of government propaganda through censorship in World War II was comparatively limited. Political persuasion and support for the war were more indirectly carried out by commercial media and the advertising industry through the auspices of the War Advertising Council and the OWI’s Bureau of Campaigns (Chambers 2010, p. 184). This follows Fussell’s insightful point that the government’s media campaign created a fictive world that was constructed by wartime public relations officers, an image of “pseudo-war and pseudo-human behavior not too distant from the familiar world of magazine advertising and improving popular fiction” (Fussell 1989, p. 163).

During the early stages of the war, the American public naively hoped the conflict would be carried out with mechanized efficiency and the government exploited the nation’s deep deficiency of imagination regarding the harsh realities and insensate violence of modern warfare (Fussell 1989, p. 38). As noted previously, press censorship was most vigilant around suppressing any images of bodily wounding and mutilation of American war dead. Wounded soldiers were always shown with their bodies intact and covered with uniforms or blankets to shield injuries; their facial expressions often alert and smiling (Figure 1). Despite the visual control exercised over such images, they could still induce for many American viewers a threatening sense of the psychological permeability of home front and war front. As James J. Kimble has explained, WWII visual propaganda often encouraged Americans to identify with images of fighting men, deploying the “civilians as soldiers” metaphor. In an effort to enlist citizens to support the national war effort, the government urged them to take part in such supportive activities as scrap drives, working in munition factories, buying war bonds, and maintaining codes of silence on military matters. Through these patriotic efforts and forms of sacrifice, civilians viewed themselves as a domestic fighting force who were conceptually united with troops fighting abroad. However, as the conflict escalated with mounting injuries and body counts, this propagandistic association created a troubling tension for Americans. By censoring visual depictions of military casualties, the government was able to retain the persuasive ideology of the “civilian as soldier” metaphor without intensifying its visceral links to actual wartime wounding and death (Kimble 2016, p. 544).

Figure 1.

An Injured Man in a Stretcher on Board USS Minneapolis, 1 December 1942. National Archives photo no. 80-G-211222. Used with permission.

While national fears of bodily wounding in war were dealt with through censoring and erasure, they were also countered by more idealized depictions of the male fighting body in propagandistic imagery. A prime example is the figure of the comic-strip superhero Captain America. Timely Comics introduced the character in 1941 in an attempt to tap into an awakening patriotic consciousness sparked by the war (Dittmer 2005, p. 629). On many of the comic book covers published during the conflict, Captain America is shown in dramatic combat scenarios overpowering Nazi or Japanese enemy forces. The glorified muscular figure of Captain America literally embodied the nation and was intended to signify its invincible military strength. As can be seen on the cover of Captain America from January 1943, American soldiers often accompanied the superhero in these scenes as able-bodied military comrades, and their presence served to reinforce the symbolic fusion of the individual body with the larger body politic.1

In sustaining national support for the war, another challenge faced by the government was the need to continuously promote the sense of danger and threat from Axis enemies while also alleviating these anxieties. Much of the aim of censorship and propaganda was to assure Americans of maintaining protective order and security, which would extend to the home front. Visual reportage on the war and propagandistic advertising focused on the organizational efficiency of U.S. military operations and the superiority of American industries to create scientifically advanced forms of weaponry. An effective element of morale culture was preserving illusions of rational planning and order through a misplaced faith in the power of military technology (Fussell 1989, p. 14). Precision bombing was a major trope within the government’s arsenal of visual propaganda. As indicated, many of these propagandistic messages were transmitted through advertising imagery, which allowed the capitalist industry and manufacturing companies to market their commercial products while also demonstrating their patriotic support of the war. A prime example is a 1942 advertisement for the Gruen Watch Company, which features its line of “precision watches.” The ad promotes Gruen’s contribution to the war effort by applying its technology to the designing of aviation equipment to enhance the destructive accuracy of military fighter planes (Figure 2). The crisp rendering of the dramatic aerial perspective from the vantage point of the cockpit demonstrates the persuasive benefits of illustration over photography for wartime visual culture.

Figure 2.

Gruen watch advertisement, 1942. In public domain.

A different tactic was employed in a Camel cigarette advertisement from 1942, which also found a way to position its product within the propagandistic theme of precision bombing.2 Featuring aviation engineer Tom Floyd, it depicts an intriguing space-age image of technicians testing high altitude bombing equipment. With its prominent tagline to “steady nerves,” this ad was part of a larger wartime campaign by the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company to advocate the health benefits to servicemen of smoking cigarettes with lower amounts of nicotine. In this way, the ad was also closely aligned with propagandistic efforts to downplay the emotional and physical toll of military service, promoting idealized representations of robust soldiers in a perpetual state of mental readiness and control. This strategy served to bolster strict censorship policies that banned any visual or written reference to servicemen suffering the psychological effects of war trauma, which during World War II was more commonly labeled as “shell shock” or “combat fatigue” (Glenn 2014, p. 30).

American bombing capabilities were also glorified and further popularized by the Walt Disney film “Victory through Air Power.” Based on Alexander P. de Seversky’s 1942 book of the same title, Disney’s animated documentary was produced and released in 1943. The film played a pivotal role in helping to convince both the American and British governments to more fully develop technologies of long-range bombing. An illustrated poster for the film features a screen capture of aerial bombing and depicts a squadron of bombers flying in formation over the exploding forms of enemy warplanes.3 The propagandistic tropes of technological precision and military prowess are symbolized through the regularized gridlike pattern of elevated planes that fills the pictorial frame and contrasts with the flaming, fragmented wreckage below. Despite the government’s promotion of advancements in precision and long-range bombing, the reality was that bombing was so inaccurate that planes had to fly well within anti-aircraft range to actually strike a target. Censors regularly suppressed photographs showing numerous incidents of missed targets, accidental destruction, and civilians killed due to the inability of American bombers to achieve the precision extolled in media and advertising (Fussell 1989, p. 14). However, due to the reassuring fictions of morale culture, belief in a conflict carried out through rational, remote-controlled systems helped to convince the nation of its distance and safety from the destructive turbulence of war.

3. World War II and the Re-Entrenchment of Surrealism

While Surrealism emerged from the earlier Dada movement and was influenced by a variety of philosophical and artistic sources, its origins can also be traced to the political crisis of World War I and its cultural aftermath in France in the late 1910s and early 1920s. A large number of Surrealist artists and writers had directly participated in the war as either part of fighting forces or as medics (Lyford 2007, p. 7). André Breton and Louis Aragon, two of the principal founders of Surrealism, had met while training as military physicians in 1917. Breton’s interest in many of the psychological theories underlying Surrealist aesthetics had their basis in his observation of war trauma suffered by French servicemen. Prominent artists like André Masson and Max Ernst fought in the war and later produced works that referenced the devastating emotional and physical realities of their wartime experience.

As Sidra Stich has argued, the presumed fanciful imagery of Surrealist art was actually inspired by the unprecedented violence and calamities of World War I (Stich 1990, p. 27). The disturbing deformed bodies in works by Masson and Salvador Dali reflected the extreme disfigurements of wounded war veterans, whose social plight was largely ignored in official French media (Lyford 2007, p. 55). Moreover, the stark dreamlike environments and enigmatic fragmented forms in paintings by Yves Tanguy or Max Ernst referenced war-torn landscapes. While wartime realities were encoded in Surrealist art, it is important to note that Surrealist theories and iconographies were, in large part, a critique of the French nation’s cultural response to the war. Attempting to engineer a political, economic, and cultural reconstruction in France following the war, the government of the Third Republic promoted a conservative patriotic crusade, often referred to as the “return to order”. Official right-wing ideology promoted war as an abnormal state of disorder attributable to the corrupting barbarous influence of German culture. The “return to order” called upon the French nation to reaffirm its association with the cultural ideals of Mediterranean classicism and reflected a craving for order, stability, and the calming forces of tradition that would follow the unparalleled disruption of war (Cowling 1990, pp. 11–12). As a means to aid reconstruction, French citizens were exhorted through propaganda to conform to a personal regimen of compliance and restraint and to affirm cultural values of stability, rationality, and cooperative unity. The conservative advocacy of rational virtues even influenced the work of avant-garde artists like Le Corbusier, Léger, and Picasso, who contributed to this nationalist agenda by employing classical traits of order and clarity. With his tract Towards a New Architecture from 1923, Le Corbusier aligned classicizing design with modern rationalist theories to envision a new postwar society based on technological efficiency and industrial production.

The Surrealists understood that conservative national reconstruction in France depended on ideological indoctrination and they sought to destabilize the traditional cultural, social, and gender norms being promulgated by the government. This included traditional ideas regarding family, patriotic duty, and productive industrial labor that were key to French national identity in the early twentieth century (Lyford 2007, pp. 4–5). Surrealist art and theory represented a profound shift in Western thinking that resulted from World War I. Influenced by the revolutionary psychological theories of Jean-Martin Charcot and Sigmund Freud, the founding members of the movement embraced new insights on irrationality and unconscious aggression as reflective of human nature. In opposition to the idealism of the Republic, the Surrealists rejected reason and Cartesian principles of order as preeminent attributes of modern society and no longer viewed conflict and destruction as aberrant conditions. Breton’s radical concepts in the First Surrealist Manifesto (1924) regarding psychic automatism and engagement with the psyche “unimpeded by the control of reason” was an anarchic rejection of the prevailing ideologies of rationalism (Silver 1989, p. 391). Much of the Surrealist imagery of bodily violence and disruption also represented a disavowal of the government’s repression of wartime realities, in particular, illusions of social order through the regulating power of reason and technological control.

Many of the European Surrealists immigrated to New York City with the advent of World War II, a group which included Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, André Masson, Marcel Duchamp, and Kurt Seligmann. While prominent members of the Surrealist community during the war remained in Europe or had fled to other international locales like Mexico and the Caribbean, the artists in New York did form a coterie around Breton. Breton sought to reassert the significance and relevance of the movement by reiterating its crucial alignment with the cultural conditions of modern war. His major pronouncements on the relation of Surrealism to World War II were voiced in an interview conducted with Nicolas Calas in View in November 1941 and in a lecture delivered at Yale University in 1942 titled “The Situation of Surrealism Between the Two Wars” (Breton 1948). Calas’ interview promoted the idea that Breton’s resolve as leader of the Surrealist movement had actually been strengthened by the adverse conditions of war (Calas 1941). Echoing some of the movement’s original premises, Breton saw the war as the product of the failure of multiple belief systems ranging from Christian religion to rationalist philosophy. However, he adopted a more apocalyptic and visionary tone and predicted World War II would lead more fully to the destruction of outmoded cultural norms. This would provide an opportunity for Surrealism to erect radical new forms of thought towards the creation of a liberated and spiritually reconstructed social order. Breton asserted that the crisis of the war absolved these goals of “any utopian aspect” and reaffirmed the core Surrealist principles of automatism, “objective chance”, and black humor as having scientific importance in this socio-political quest. With regard to social factors accounting for the war, he was particularly adamant that the world was in the process of dying from closed rationalism, a problem he especially equated with an American mentality. He stated “I am assured that in this sense a strong current exists in America—…the salvation of man … (demands) his ‘disintellectualization’ for the sake of a reevaluation of his prime instincts” (Calas 1941, p. 2).

Breton’s Yale lecture the following year emphasized the primacy of the First World War in the formation of the Surrealist movement, which included its strong ongoing antiwar stance. He stated, “I insist on the fact that Surrealism can be understood historically only in relation to war; I mean—from 1919 to 1939—in relation at the same time to the war from which it issues and the war to which it extends” (Breton 1948, p. 74). Breton’s talk coincided with the one-year anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. At the onset of the lecture, he addressed the students as young men about to go to war, identifying their perilous position with that of his own Surrealist generation of 1917 (Sawin 1997, p. 245). He proclaimed that World War I “had transformed the mental life of an entire generation, undermining the positivism of the prewar ruling order and giving Surrealism the mission to rethink every accepted truth” (Shell and Tostman 2018, p. 9). He also repeated his unwavering denouncement of rationalism as a false and misleading creed, which the Surrealists rejected for obscuring the violent and psychoneurotic nature of modern society and its propensity towards war. As he asserted, “one would have us believe that humanity knows how to rule itself…. But what, …is that narrow ‘reason’ which has been taught us if that reason must … yield place to the unreason of wars?” (Breton 1948, p. 68). This was the only public lecture Breton delivered during his exile in the United States, but it was regarded as a significant political document and was published multiple times, most notably in the review Fontaine, and was circulated as a revolutionary tract in Nazi-occupied France.

It is important to call attention to Breton’s repeated attacks against rationalism as a social ill associated with wartime culture in the 1940s, particularly its prevalence within American society. No doubt Breton and other exiled Surrealists would have discerned parallels between the ideological ideals of the earlier Third Republic’s “return to order” and those of the conservative morale culture of World War II that were forming in the United States. In both political periods bracketed by war, nationalist programs promoted rational values of social order and technocratic control to help quell anxieties associated with the disruptive forces of war. Another significant parallel that would have been encountered by the Surrealists is the role of avant-garde art in the United States as an ideological emblem of social stability in a time of political distress. During the early forties, the major progressive style was the geometric abstraction associated with the American Abstract Artists group, which included the Constructivist and Neoplasticist paintings of artists like Burgoyne Diller and Harry Holtzman. Writing in Partisan Review in 1941, the art critic George L. K. Morris maintained that classicizing forms of geometric abstraction could serve as a paradigm of order and rational purpose in a modern world overrun by various forms of political and social chaos (Morris 1941, p. 414). As Oliver Shell and Oliver Tostman noted in the exhibition catalogue Monsters & Myths: Surrealism and War in the 1930s and 1940s, such parallels (as well as the disastrous return of global war itself) must have made the Surrealists feel “trapped in an inescapable cycle of repetitive history, not unlike the Minotaur in his labyrinth…” (Shell and Tostman 2018, p. 12).

In the final double issue of the Surrealist journal Minotaure in May 1939, which coincided with the Fall of France, Breton issued a mandate of political engagement for all avant-garde artists in a time of war, proclaiming their responsibility to resist false, comforting visions of order and security. He exclaimed, “At the very hour … where elsewhere the days of freedom seem to be numbered, … (many artists’) work utterly fails to reflect the epoch’s tragic sense of dread…. We condemn as tendentious and reactionary any image in which the painter or poet today offers us a stable universe…” (Breton 1939, p. 13). In his 1942 essay “Life and Liberty,” Masson also insisted on the responsibility of the artist to respond to the disquietude of his epoch. It needs to be considered how these radical views would have shaped the Surrealists’ response to the state-sanctioned visual culture of World War II in the United States, which promoted the kind of idealized social images being condemned within the movement.

4. The Wartime Mission of View

In addition to its emphasis on Surrealist art and writing, View offered an eclectic mixture of modernist poetry, editorials on mass culture, philosophical essays, and eccentric features on all manner of Americana. Although there has been little writing on the political issues and war content associated with View, a case can be made for the magazine’s strong sense of political purpose during the tumultuous years of World War II. The diverse array of editorials and articles in View does reflect the magazine’s attempts to develop a political position towards the war based on an uneasy alliance between Trotskyism, opposition to U.S. involvement in the war and theoretical shifts within the Surrealist movement (Dimakopoulou 2012, p. 743; Neiman 1991, p. xiv).

Charles Henri Ford’s extended stay in Europe had ended abruptly in September 1939 when Nazi Germany invaded Poland and American citizens were advised to return to the United States. Upon returning to New York City, Ford made it his mission to found a magazine, which he originally planned to call “The Poetry Paper.” His new journal was later renamed View when it was first published in September 1940. Ford vowed to devote View to what he termed “the new journalism,” a radical form of international writing by politically engaged poets. Feeling traditional journalism was inadequate in times of crisis, Ford claimed “contemporary affairs should be seen through the eyes of poets,” implying they were capable of a more insightful vision of the political disasters unfolding in Europe (Tashjian 1995, p. 177). An important vanguard poet in his own right, Ford had won critical acclaim in 1939 for his first book of collected poems The Garden of Disorder. He had also successfully edited an earlier journal of poetry titled Blues: A Magazine of New Rhythms, which was published from 1929 to 1930. Ford published and edited View in collaboration with the poet and film critic Parker Tyler. In developing both the editorial approach and visual styling of View, Ford and Tyler claimed as precedents other vanguard magazines, such as transition, Verve, and the London Bulletin. During View’s early years, the magazine evolved from a newspaper format to a little magazine and finally to a glossy-magazine style patterned after Minotaure’s provocative combination of avant-garde features and luxury advertising (Suárez 2007, p. 261). This final evolution in the magazine’s format reflected Ford’s ambition to position View within the domain of mainstream publishing in which he continued his polemical campaign to challenge the conservatism of national wartime media.

Ford and Tyler launched View into an exceptionally fraught political environment. That same year, Nazi Germany invaded France and the United States initiated its first peacetime military draft. Moreover, political isolationists and interventionists across the nation were fiercely debating the United States’ military involvement in the escalating political conflict in Europe (Latimer 2017, p. 79). In later years, Ford was quoted as wanting to “stonewall the war” from View and “just do poetry” in order to avoid the general hysteria of patriotism that gripped the nation (Nessen 1986, p. 12). However, more importantly, he also later referred to View as “his war work” and it is clear that ignoring the war was impossible for a topical journal during the politically charged years of the early forties (Wolmer 1987, p. 16). Beginning with its earliest issues, View was committed to serving as a platform for numerous communiques, articles, and images devoted to wartime topics. Prior to his actual publishing of View, Ford received a letter in March of 1938 from the poet William Carlos Williams, who encouraged the writer in his goal to establish a journal with the liberal mission of allowing poets and artists to speak out on political events. Williams wrote “Let’s hope you get started before a war engulfs us all again. The times are too like those of 1913 to suit me…. And there are too many who don’t want the artist to speak as he can. They’ll slaughter the world before they’ll let a Lorca live” (Charles Henri Ford Papers, Series I. b. 2, f.189). After the successful establishing of View, Williams aligned himself with the journal due to his strong belief that new magazines needed to be launched that would issue statements on the crucial role of the arts in a time of war. Williams believed that war allowed for the productive alliance of divergent aesthetic groups and cultures for the shared purpose of creative freedom that could not be “seduced by political urgencies” (Tashjian 1995, p. 208). Other radical poets in the 1940s affirmed the political engagement of View towards wartime issues. In his 1947 article “Reviewing View, an Attack,” which was originally published in the vanguard journal The Ark, Robert Duncan was largely disparaging towards the editorial sensibility of Ford and what he saw as the sensationalism of the later issues of View. However, referring to the magazine’s early years, Duncan commended Ford for his anarchistic hostility towards the “State and its war” and his rejection of the violence and “cruelties of modern social institutions” that supported what he called the “Permanent War Economy” (Duncan 2014, pp. 26, 28).

The earliest issues of View broadcast news on the grave military situation in Europe, such as Kay Boyle’s “Communique” written from Megéve, France near the French–Swiss border, which appeared in the October 1940 issue and expressed the prevailing mood of political uncertainty after the Nazi invasion of Paris. Ford printed similar political communiques from writers in Sweden, Cuba, and Great Britain, providing insights on the social and cultural effects of the war that were often not available through standard news media. These communiques followed the publishing practice of Partisan Review in the 1940s, which featured reports from European intellectuals imperiled by the war and the repressive cultural policies of Fascist regimes. Like Partisan Review, View felt a moral commitment to maintain vital lines of communication between European and American intellectual communities divided by the upheaval of the war (Nessen 1986, p. 227). In addition, View published longer reflective essays on political topics pertinent to the war, such as the Nazi persecution of avant-garde culture and the use of Hollywood war films as nationalist propaganda. In the February–March 1942 issue of View, the eminent playwright and essayist Lionel Abel published a notable article titled “The Politics of Spirit.” Published shortly after the Roosevelt administration instituted its war propaganda and censorship policies, Abel’s piece is an important indication of the magazine’s critical concerns regarding American morale culture. Abel analyzed how political morale and support of war is often generated in a culture in which societal values and major institutions have been weakened, leaving a populace dispirited and feeling that only war can provide a sense of purpose and meaning. However, he questioned whether the U.S. government could actually foster a true sense of wartime morale, which requires a revolutionary populace willing to subordinate itself to the political demands of the state and accept death as indispensable to military victory. In contrast, the American public had placed its faith in the nation’s industrial power and the remote-controlled efficiency of its weaponry, which reflected the misplaced “hope of a spirited people who have not yet become revolutionary, who are used to playing while their machines suffer” (Abel 1942, p. 4).

The wartime mission of View was similar to that maintained by the English literary journal Horizon, which was edited by Cyril Connolly. More elitist and conservative than View, Horizon also featured an eclectic mix of pieces on art, philosophy, and music and published many of the same avant-garde poets like Wallace Stevens and Marianne Moore. Connolly promoted the magazine as offering an alternative to the patriotic mediocrity of mainstream media and argued that its large educated readership of English servicemen saw the preservation of elevated culture as a cause to fight for (Fussell 1989, p. 212). This paralleled the political position of View, as Tyler frequently sent copies of the journal to American fighting forces as a symbol of opposing totalitarianism by defending intellectual and artistic freedom. The magazine also issued promotional flyers during the war with quotes by famous poets like Edith Sitwell, who claimed that View was “the most courageous magazine being published during the war” (Charles Henri Ford Papers, Series III. b. 36. Scrapbook 1944–1947).

5. View, Surrealism and Wartime Media

In defining the wartime mission of View, it is especially important to consider the complexities of the exiled Surrealists’ political response to the war. Although scholars like Catrina Neiman have argued that View lacked any defined political position towards the war, its critique of wartime media needs to be considered as a clear agenda of political dissent (Neiman 1991, p. xiv). In her writing on the émigré Surrealists, Romy Golan has asserted that they tended to Romanticize their exile in America. In expressing their political plight, they viewed their new home in more lofty and mystical terms as a place of spiritual refuge and regeneration. As a result, they ignored the world of popular, everyday experience in the United States, relocating their new wartime mythologies outside the realm of mass culture (Golan 1997, p. 137). However, this article argues that Surrealists affiliated with View did establish a strong form of critical engagement with American mass culture and sought to subvert the media’s highly sanitized and ideologically manipulated representations of the war. With the failure of Surrealism’s alignment with the Communist party in the mid-1930s and its forced relocation to the United States in the early 1940s, the movement lacked its earlier political structures for organized agitation and critique. As a result, it should be noted that exhibitions and especially journals increasingly served as alternate forums for the movement’s strategies of political engagement.

The poet and critic Nicolas Calas had been the most instrumental in aligning View with Surrealism in the early forties and adhered to many of the more orthodox tenets of the movement established by Breton. Calas’ advocacy of Surrealism through View helped to popularize the movement in the United States and earned a larger supportive readership for the magazine. As Tashjian has argued, Calas was especially crucial in gearing his selection of material in View to the critical issues that gripped Surrealism at the time of the war (Tashjian 1995, p. 190). As a result, View became a major platform for highlighting the Surrealists’ ideological perspectives towards the war, which served as a radical counter-discourse to the conservative nationalistic narratives on the conflict. In discussing the institutional reception of Surrealism in the United States in the early 1940s, Angela Miller and Sabine Eckmann have noted that art critics and museum curators tended to depoliticize the movement, stripping the art of its ideological content (Miller 2007, p. 62). Attempting to avoid political controversy or public rejection of Surrealism, writers like James Johnson Sweeny and James Thrall Soby focused on the progressive formal values of Surrealist art, ignoring much of its contemporary relevance and troubling war references (Eckmann 1997, pp. 157, 172). However, this conservative tendency was countered by writers in View, most notably Calas and Julien Levy, who used their analysis of works by Yves Tanguy and Max Ernst to reinstate a strong political awareness of wartime content and meaning (Nessen 1986, p. 259).

Prior to American entry into the war, various pieces in View referenced the conflict waging in Europe, most likely in response to the general apathy in the United States regarding the plight of war victims overseas. In January 1941, Kurt Seligmann published a print titled The Golem, which depicts a bizarre metamorphic figure that is composed of flayed and bandaged anatomical parts. The image accompanied an article that described the “madness” of British stoicism in the face of the German air raids. Echoing other Surrealists like Breton and Masson, several articles strongly advocated that artists and writers have a responsibility to acknowledge the political and social crisis of the war in their works. In his essay “An Eye for a Tooth” that appeared in November 1941, Seligmann asserted that artists must project the anguish of the period by relying on familiar symbols of violence and death, such as massacres, executions, faceless heads and ghostly apparitions (Seligmann 1941, p. 3). While this was advocated as an ethical duty, it was also a means for artists to maintain their own psychic health by giving individual expression to collective forms of social trauma. Along these same lines, Alain Bosquet argued in a later issue that poetry in wartime must address the issues of exile and modern apocalypse typified by Breton’s Fata Morgana and the writing of Aimé Césaire.

As early as 1940, Roosevelt had spoken out against what he termed the delusion of believing in the safety of the United States as a “lone island” in a world increasingly dominated by force. With the war escalating in Europe, Roosevelt’s government made the decision to provide democratic European Allies with military aid and increase war production to ready the nation for defense. By 1941, debates intensified in the United States between isolationists and interventionists on the need for American involvement in the conflict. The growing political power and military aggression of Germany bolstered the interventionist argument over the imminent threat of Nazi invasion. Media reports in 1941 invoked the specter of possible German air raids on major metropolitan centers like New York City and Los Angeles. With the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December of 1941 and American involvement in World War II, the government began to implement its full-scale media censorship and propaganda programs. The most stringent phase of censorship extended from early 1942 through September of 1943. As noted previously, this was accompanied by massive forms of official propaganda and propagandistic advertising campaigns in popular media. These programs were given the complex task of both shoring up national morale towards the conflict and alleviating the public’s growing anxiety over the destructive forces of technological war. In her writing on the moral implications of viewing war photography, Susan Sontag noted the most disturbing issue is not necessarily the violence that is depicted, but what violence and death are not shown. She raises important questions concerning the role of political structures in choosing what visual horrors the public is exposed to and for what ideological purposes (Sontag 2002). As Roeder observed, American media in the early forties developed into a “journalism of reassurance, not information” (Roeder 1993, p. 13).

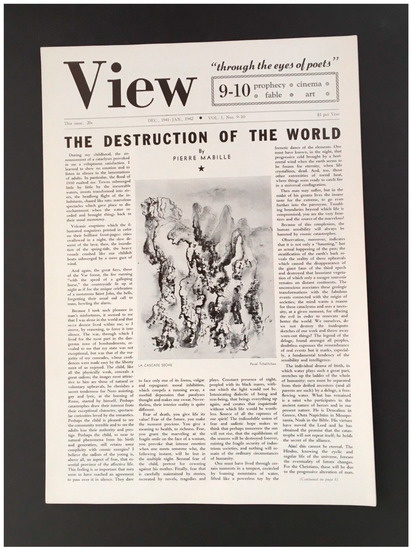

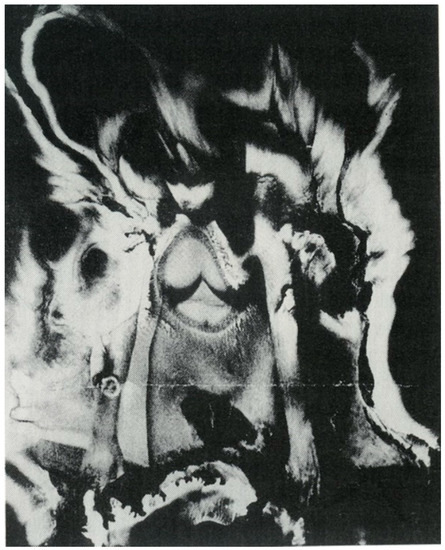

The January 1942 issue of View is an early indication of the Surrealist response to both the growing crisis of global war and the conservative agendas of an incipient morale culture. Two major pieces in this issue reflect the magazine’s commitment to bear witness to the catastrophic realities of war. The cover article titled “The Destruction of the World” was written by Pierre Mabille, an expert on anthropology and editorial director of the Surrealist journal Minotaur. It was accompanied by an image titled La Cascade Sèche by Pavel Tchelitchew (Figure 3). Mabille’s essay was excerpted from his 1940 book Mirror of the Marvelous, which reflects the interest he shared with the Surrealists in ancient religions, supernatural modes of knowledge, and the history of collective mythologies. Following the psychological theories favored by the Surrealists, Mabille viewed World War II as stemming from a fundamental sadistic drive in humanity and he regarded the poet as the prophet of “that indispensable destruction.” In the essay, he used the destructive forces of geologic evolution and spiritual apocalypse as metaphors for wartime violence, lamenting these poetic allegories had been rendered meaningless by the overwhelming reality of modern war. He stated, “…the mangled children, the tortured bodies, the cities disemboweled in the name of civilization…. The cries … rising from the concentration camps more lugubrious than those in Dante…” (Mabille 1942, p. 8). In relation to his discussion of spectacles of disaster, Mabille wrote on the child’s fearful delight in destruction, which can be likened to the Romantic sublime. In light of the prevailing anxiety over the war in the early forties, Mabille exalted fear as “that essential province of the affective life,” seeing it as a fundamental element in the perceptual understanding of reality (Nessen 1986, p. 49). With regard to his aberrant, dreamlike visions of wartime violence, it should be recognized that Mabille’s essay was linked to his larger cultural theories on the marvelous. A central tenet within the Surrealist movement, the marvelous was related to the aesthetic concept of convulsive beauty, an anti-classical ideal that runs counter to Enlightenment theories of beauty as harmony and order. In the context of a wartime culture devoted to reason and order, the promotion of the marvelous by Mabille and other Surrealists was a subversive means to re-enchant a ruthlessly rational and conformist capitalist society (Ferentinou 2017, p. 206). The trope of the mirror in his writings references the perceptual space of the marvelous, which involves a constant dialectic between outer reality and inner imagination, disrupting any sense of objective fixity and certainty. View’s publishing of Mabille’s essay can be seen as a call to challenge the authority of official representations of wartime realities through the transforming powers of the marvelous.

Figure 3.

Pavel Tchelitchew, La Cascade Sèche, View, January 1942. In public domain.

The Surrealist imagery of Tchelitchew’s La Cascade Sèche that accompanies the article is rendered with loose, scumbled strokes and depicts figures merging with an abstract pattern of jagged rocks. The illustration appears to follow the essay’s theme of describing wartime destruction in the symbolic terms of a geologic upheaval. The fragmented design and simulation of Surrealist decalcomania reinforce a sense of random disorder and destruction. An artist closely identified with the movements of Magic Realism and Surrealism, Tchelitchew had executed a large number of imaginary metamorphic landscapes in the thirties and early forties that resemble La Cascade Sèche. Yet, the broken terrain of this scene evokes a landscape destroyed by battle or aerial bombardment, an idea that is strongly reinforced by its pairing with Mabille’s essay. While such jarring images would have been a very real vision of the military destruction the Surrealists had left behind in Europe, View’s publishing of this work would have breached some of the sense of safety and distance the American public felt towards the threat of military conflict.

Within the context of wartime culture, it is also possible to read the image as reflecting other underlying social anxieties related to the war. A distinctive feature of the work is the vague sense of figural forms that merge with the fragmented landscape. Twisted figures and disembodied heads blend with the blasted formations of rock. This symbolic element signifies dual meanings of destruction and protective concealment that may relate to the strong interest in issues of military camouflage during the early forties. Later that same year, Tchelitchew had completed a painting titled Hide-and-Seek, which was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art for its permanent collection in 1942. Similar to La Cascade Séche, Hide-and-Seek depicts a bizarre metamorphic landscape in which translucent figures become absorbed into the organic form of a massive tree. In the painting, the child’s game takes on a frightening aura that suggests the need for concealment against a menacing force. The work’s ambiguous imagery exhibits signs of disappearance, spatial incoherence, and disorientation through doubling. Art historians have related these traits to techniques of military camouflage and have argued the painting’s strong connection to forms of visual experience and perception coextensive with wartime culture (Elias 2013, p. 371). As evidence of the painting’s association with camouflage in the early 1940s, it was reproduced in a special 1942 issue of the magazine ARTnews that was devoted to the topic of military camouflage and its various artistic applications. It should be noted that the publishing of Man Ray’s photograph Dust Breeding in a 1920 issue of Breton’s journal Littérature set an important precedent for Surrealist images referencing wartime landscapes. Depicting an elevated view of Duchamp’s The Large Glass coated with dust, the bizarre caption for the photograph noted it was glimpsed from an airplane and was no doubt intended to evoke an aerial view of a WWI battlefield.

The stylistic innovations of various modernist movements contributed to the visual techniques used for military camouflage from World War I through World War II. Although this influence began with Cubism, Surrealism was the most closely aligned with the theory and practice of military camouflage due to its emphasis on mimetic deceptions and metamorphic conceptions of form (Kavky 2018, pp. 1–2). Roger Caillois’ famous writings on mimicry in nature through the blending of insects with their environment were also an important aspect of Surrealist theory that influenced techniques of camouflage. Yet, in a more accessible form, the Surrealist writer and painter John B.L. Goodwin published similar ideas to Caillois in his article in View in 1942 titled “Remarks on the Polymorphic Image” (Elias 2012, p. 19). In May of 1941, Roosevelt had established the Office of Civilian Defense, which was tasked with developing tactics for protecting civilian populations in periods of military emergency. It was a massive bureaucratic apparatus that contained the Engineer Section, which was part of the Protection Branch that devised plans for blackouts and camouflage. In an age of modern warfare, there was a growing fear over the difficulty of escaping the threat of technological weapons. These anxieties were stoked further in the early forties by the growing military power of Germany, which led to national debates and media reports on the possible danger of air raids on major American cities. In response, a special Camouflage Unit was formed that established programs to educate the public on the effective use of military camouflage and a series of camouflage schools were planned that sought to enlist artists to devise new methods (Blakinger 2015, p. 38). The topic of camouflage was popularized in numerous mass-market books and in newspaper and magazine articles. Beginning in May of 1941, a series of three exhibitions on military camouflage was presented by the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The first was “Britain at War,” which showcased a variety of camouflage techniques that had recently been developed for wartime use. The exhibit catalog also included an essay on the unique role of the abstract artist in camouflage and stressed a main purpose for the display was to inform the American public on “strange new examples of camouflage” that would soon be seen throughout the United States (Wheeler 1941, pp. 90–94). In his study on the American government’s Camouflage Unit, John Blakinger has speculated that there might not have been a real need for widespread use of camouflage in World War II, especially in the United States. Even in the European theater, most bombing was over widespread areas intent on large-scale damage rather than precision hitting of targets. The camouflage education programs and schools may have been an essential part of wartime propaganda campaigns. Both were symbolic efforts to sustain national morale by creating the semblance of military protection and giving the impression that civilian populations were actively supporting the war effort (Blakinger 2015, pp. 49–50).

The publishing of Tchelitchew’s La Cascade Sèche in View coincided with this period of fear over military invasion, which was countered by the widespread circulation of information and propaganda in the media on the defensive benefits of camouflage. As noted, the work features strange permutations based on the merging of figures with the forms of a ravaged landscape. The image shifts between a sense of presence and absence, destruction and protection. Tchelitchew’s illustration captures the contradictions of wartime media in which an anxious public was offered both political warnings and forms of reassurance regarding the threat of aerial attacks.

In this same issue of View, David Hare’s photograph Marine Fire (Figure 4) served as an illustration for an article on the war and the Fascist attacks against Surrealism. Created using the radical automatist method of “heatage” (the melting of a photographic negative), it depicts a fragmented and deformed figure seemingly surrounded by an explosive swirl of flame. Mona Hadler observed that the figure partially consumed by fire “revealed a cataclysmic metamorphosis of flesh, fire and water so pertinent to the war years” (Hadler 2011, p. 101). Hare’s approach emulated the similar brûlage technique of the Surrealist photographer Raoul Ubac, who developed automatist forms of photography as a means to combat the rationalist objective properties of the medium. A prime example is Ubac’s 1939 photograph The Battle of the Amazons, which suggests the destructive workings of fire with a series of formless, disintegrating figures. Rather than promoting a positive sense of the creative discovery associated with automatism, techniques like heatage and brûlage emphasize its subversive and destabilizing qualities. Moreover, while automatist images of convulsed bodies traditionally represent internal states of psychic ecstasy, Hare’s and Ubac’s figures indicate an assault of destructive outside forces (Krauss and Livingston 1985, p. 24). It is important to note that Ford had planned to use Ubac’s brûlage photograph Agrégat humain to illustrate Mabille’s essay “The Destruction of the World” for an anthology of Surrealism in View, which was never published (Charles Henri Ford Papers, Series III. b. 14. “Surrealism in View” 1970). Hare continued to use the heatage technique in the early forties for photographs of formless abstracted figures, which resemble charred bodies mutilated by the violence of war. One of these works was included in a 1943 portfolio published by the Surrealist journal VVV, which Hare edited in collaboration with André Breton. By forcing the viewer to confront a sense of the bodily trauma and wounding suffered by American soldiers, Hare’s images opposed the aim of government censorship to control and sanitize the visual experience of war. With the extreme distortions and jarring alterations of his own photographs, Hare’s technical assault on the medium is itself significant and reflects a radical effort to subvert the documentary status and truth value of the official media’s photographic reportage.

Figure 4.

David Hare, Marine Fire, View, January 1942. In public domain.

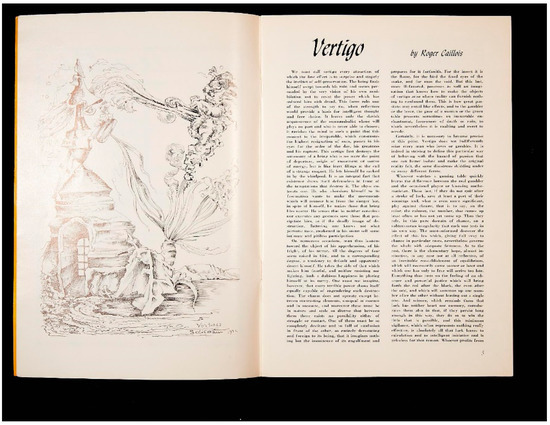

In other issues of View during the early 1940s, prominent French intellectuals allied with Surrealism offered polemical sociological and philosophical reflections on modern war, such as Roger Caillois’ famous essay “Vertigo” that was published in October 1942. It was paired with a fanciful illustration by Kurt Seligmann titled Vertiges (Figure 5). Caillois is notable for attempting a new political and social theory rooted in religious, philosophical, and mystico-surrealist studies on the instinctual. He was part of the radical Collège de Sociologie cofounded in the 1930s by Georges Bataille and Michel Leiris. All three were particularly interested in the social effects of the sacred, particularly in the vertiginous limit-experiences of attraction and repulsion that serve desublimatory functions within modern society. Their views resulted from their political disenchantment with the rationalism and conservative ideologies of the Third Republic following World War I. Caillois saw the social urge towards reason, restraint, and technological control in the modern age as a destructive element. In “Vertigo,” he argued such urges towards self-preservation and repression in modern society are counteracted by moments of unreasoned, self-destructive passion like gambling or unrequited love. However, he cited war as the ultimate form of vertiginous excess and release. He stated that “The being finds himself swept towards his ruin and seems persuaded by the very vision of his own annihilation not to resist the power which has seduced him with dread” (Caillois 1942, p. 5).

Figure 5.

Kurt Seligmann, Vertiges, 1942, View, October 1942. © 2020 Orange County Citizens Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Used with permission.

Vertigo most often involves feelings of dizziness and the sensation of falling or spinning in space; these symptoms are often accompanied by nausea and emotional distress. In writing on the avant-garde’s concern with the metaphysics of space perception, Caillois cited a tendency in vertigo towards disorientation and the subject’s lack of sensing their own physical placement in space (Lomas 2006, p. 84). Seligmann’s enigmatic image depicts a mechanized tower with heraldic emblems that is juxtaposed with a strange vaporous being. Its tendrilled arms are extended out into space and it appears to be struggling against the magnetic pull of the tower. The apparent conflict between the two forms suggests Caillois’ emphasis on the dialectic between a restraining force and vertiginous release. Yet, the amorphous structure of the floating figure evokes the profound sense of perceptual dislocation and lack of control associated with vertigo. It is crucial to note that for Caillois and Bataille, their conception of vertigo and even their aesthetic and social definitions of its effects were strongly tied to medical and psychological theories of war trauma stemming from World War I. They had been introduced to these ideas in the early thirties through the discovery of a textbook titled Les Vertiges (1926), a neuro-psychiatric primer that explained the treatment of soldiers suffering from shellshock (Lomas 2006, p. 83). Many of these military patients exhibited the hysterical symptoms and subjective disorientation associated with vertigo. Of the Surrealist artists who fought in World War I, Masson is the most well-known for producing works that referenced his recurring experience of war trauma, which included feelings of fearful disorientation that he notably ascribed to vertigo (Poling 2008, p. 52). Surrealist theorists like Breton and Aragon, who had studied war trauma as medical trainees, used their knowledge of vertigo and other pathological symptoms to valorize hysteria as a form of psychic release that rejected the conservative social dictates of reason and control. These ideas were influential for Caillois in his own analysis and valorization of vertigo as a nihilistic reaction to repressive social mechanisms.

During the early forties, government censorship of media suppressed any reports or images of American soldiers suffering psychic traumas inflicted by warfare. The War Department Bureau of Public Relations deemed what it called “psychoneurotic” war casualties as even more disturbing to the public than physical wounding and death (Roeder 1993, p. 2). As a means to maintain national morale, any evidence of war trauma or even emotional fatigue in combat were censored in both print media and Hollywood war films as late as 1944. Military manuals dispensed to troops did acknowledge fear and apprehension as natural in wartime but advised soldiers to suppress their anxiety and feign emotional strength in order to not spread panic in battle and to support morale (Fussell 1989, p. 274). The military tended to downplay the serious effects of war trauma and commonly referred to the condition with such innocuous terms as “combat exhaustion”. The common view on treatment was that psychological symptoms would naturally heal themselves after soldiers returned home to the normalcy of civilian life. As discussed previously, even examples of advertising, such as the 1942 ad for Camel cigarettes, advocated the need for American fighting forces to maintain mental fortitude and control. Continuing through World War II and the postwar years, the American public associated vertigo with war trauma, which is most famously reflected in Alfred Hitchcock’s cinematic thriller “Vertigo” from 1958. As Colleen Glenn has argued, Jimmy Stewart’s character John “Scottie” Ferguson suffers from forms of psychological trauma that represent ongoing anxieties over the residual effects of wartime trauma that were widespread in American society (Glenn 2014, p. 27). For the Surrealist vanguard, Caillois’s essay on the dissolution of control and reason in wartime would have had strong critical resonance, particularly within a conservative morale culture that promoted rationality and social order as a means to cope with political and military crises. Moreover, View’s publishing of “Vertigo” can be regarded as a provocative, even agitational, gesture that challenged prohibitions in American media to address issues of psychological distress related to war.

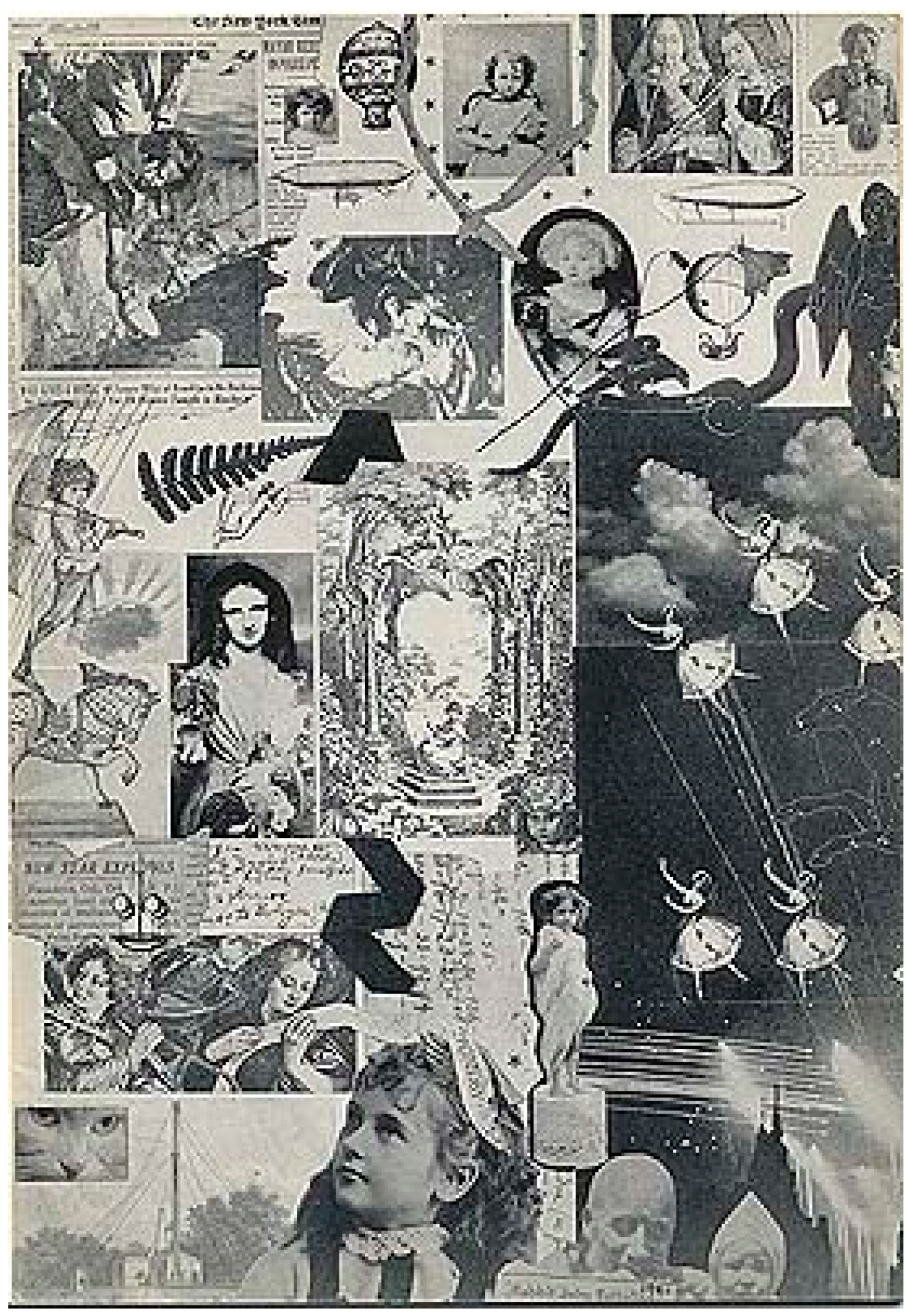

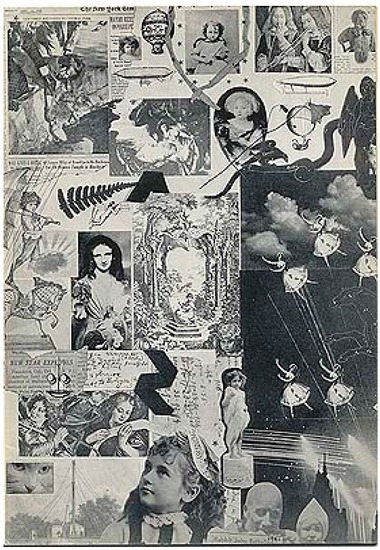

Joseph Cornell, who was aesthetically and conceptually aligned with the Surrealist movement, can also be seen as participating in the Surrealist critique of wartime media in the pages of View. The prime example is Cornell’s contribution to the “Americana Fantastica” issue, which was published in January 1943 and edited by Parker Tyler. This issue contains a diverse array of eccentric and ephemeral American literature and visual culture that includes the obscure science fiction of Alva N. Turner, poems by children, and the street photography of Helen Levitt. In his introduction, Tyler praised the untutored and anarchic qualities of the fantastic as a means to resist and contest forces of social order and convention. His definition of the fantastic within an American context is aligned with Bretonian Surrealism, in particular the role of the marvelous in Surrealist thought. Moreover, Tyler’s conceptual agenda for the issue intersects with the larger political mission of View to oppose wartime media, as he promotes the fantastic as a subversive, decentered element that acts as an antidote to the reality constructed and naturalized in official forms of visual culture (Latimer 2017, p. 83).

Cornell designed the cover for the “Americana Fantastica” issue and also created a story in text and images titled the Crystal Cage (Portrait of Berenice). It centers on the theme of an imaginary child protagonist named Berenice, who reflects his fascination with the spiritual innocence of children and their powers of imaginative insight. Cornell’s narrative recounts the adventures of a young girl who is both a precocious scientist and visionary. While visiting France, Berenice becomes enamored of an abandoned eighteenth-century architectural folly (the legendary Pagode de Chanteloup). Designed in the form of a Chinese pagoda, the structure is moved to her family home in New England, where it is transformed by Berenice into a crystal observatory and laboratory for carrying out her scientific studies. As part of his story in View, Cornell created a calligram in the shape of the observatory, using the words to describe her fantastical research viewing constellations and other celestial phenomena.

One of the major works in the Crystal Cage is a collage portrait of Berenice that can be analyzed for intriguing wartime content. This reading is supported by the scholarship of Analisa Leppanen-Guerra, who has interpreted this collage as well as a larger range of Cornell’s boxes from the 1940s as containing symbolic meanings referring to World War II. For example, she discusses his assemblage box Habitat for a Shooting Gallery from 1943 as one of the artist’s most overtly political works. According to Leppanen-Guerra, Cornell created the piece as a rebuke to a dismissive review by Edward Alden Jewell, who castigated the artist for devoting himself to escapist works of decorative whimsy during a period of war. One of his “Aviary” boxes, it features two cockatoos and two parrots, which are arranged and numbered like targets in a Cooney Island shooting gallery. The box also contains collage elements with French phrases, signage, and architectural motifs that reference the Nazi occupation of France. In addition, it includes the disturbing details of broken glass and splatters of colored paint that indicate several of the birds have been shot. These details not only make clear that the European theater had become a deadly “shooting gallery,” but they also reflect Cornell’s awareness that the violent reality of World War II had penetrated and shattered the hermetic dreamworld of the Surrealists (Leppanen-Guerra 2016, p. 265).

While the Crystal Cage collage has been analyzed for wartime meanings, it is possible to discuss a more specific critical response to wartime propaganda and media in this work (Figure 6). The dense layering of images, many cut from newspapers and commercial magazines, evokes the explosion of mass media in the United States that accompanied World War II. The collage represents the multitude of Berenices that Cornell encountered in popular visual culture, as well as symbolic references to her many scientific preoccupations and fanciful interactions with modern urban reality. Berenice was raised in a severe atmosphere of scientific rationalism and her glistening observatory becomes an alternate ideal world for conducting her romantic research into astronomical wonders. Echoing the subversive intent of the Surrealist marvelous during wartime, this theme of anti-rationalism has significance for the war references in the collage.

Figure 6.

Joseph Cornell, Collage, The Crystal Cage (Portrait of Berenice), View, January 1943. © The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Used with permission.

Several of the collage elements refer specifically to war, which clearly connects the work to topical issues of World War II. For example, in the upper left corner, a newspaper photo shows Berenice rescuing a duckling in Central Park and the caption underneath reads “WAR GIVES A BREAK TO … BOY.” Along the bottom edge of the work there is another newspaper clipping that states “Rabbit Joins Battalion.” However, one of the most important symbolic references to the war is a vertical image that extends from the bottom right corner to the middle of the collage. It depicts a tower silhouetted against a night sky that contains shooting stars and the constellations Pegasus, Virgo, Hydra, and Corvus. Cornell’s depiction of constellations serves as a reminder that Berenice’s namesake is the constellation Coma Berenices, which means “Berenice’s Hair” in Latin. This refers to the ancient Egyptian queen Berenice II, who sacrificed her hair as a votive offering in return for the king’s success in war.

In her discussion of the collage and its wartime meanings, Leppanen-Guerra has argued that the primary theme of the work is the role of Berenice as an agent of peace and spiritual wonder in a world overrun by the destructive forces of technological war. She links this theme to Cornell’s pacifism and religious faith as a Christian Scientist, who adhered to a spiritual philosophy of mind over matter and in purifying one’s thoughts to disavow the existence of evil and war (Leppanen-Guerra 2011, p. 83). Jodi Hauptman has also related Cornell’s preoccupation with the theme of childhood through Berenice to Christian Science, which promoted the idea that children held out the possibility of spiritual renewal and guidance for adults (Hauptman 1999, p. 166). This theological belief was used by Cornell in fashioning the antiwar message of the collage, as Berenice derives hope even in the midst of wartime and strives to use the powers of imagination for positive invention. This point is most evident in the collage image depicting the constellations in the nighttime sky. In addition, the sky is crossed by lines representing shooting stars that resemble the illuminated arc of tracers from military gunfire. Cornell’s dossier for the Celestial Theater (c. 1940–1958, a collection of images and textual notes devoted to astronomy) contains photographs from Life magazine of German tracer fire during a nocturnal aerial battle in World War II (Housefield 2018, p. 13). Such photographs of aerial warfare were widely published throughout the conflict in the popular press. However, the reference to aerial gunfire in the collage is paired with fanciful images of floating dancing girls that leap across the night sky. Cornell’s use of this motif for a wartime scene was most likely inspired by his reading of Guillaume Apollinaire’s calligrams from World War I (Leppanen-Guerra 2016, p. 273). Many of these image poems were written in the trenches while fighting with the French army and several refer to military flares as resembling the beautiful flashing forms of dancing ladies. Evoking lyrical images of grace and beauty was a form of resistance and protest against the inhuman carnage of war. Cornell undertook a similar symbolic strategy in his collage by likening deadly military gunfire to the wondrous beauty of shooting stars, which are also represented as glowing, fairylike dancers. It also needs to be understood that this transformed symbolic vision of war must be ascribed to Berenice, who attempts a marvelous re-enchantment of the heavens. Through her romantic science, she promotes the peaceful practice of stargazing and attempts to reclaim the skies as a site of celestial beauty and serene spiritual contemplation.

During World War II, Cornell himself was concerned that the threat of air raids and the emphasis on the prowess of the military’s aerial weapons would transform the skies into a space of terror rather than wonder. In a note from the Celestial Theater dossier, Cornell wrote “Alarmed by the scientific innovations of our age, …the barbarity of bombings whereby the surface of the earth has almost come to resemble the craters of the moon, in protest against the desecration of the skies was this assemblage drawn…” (quoted in Leppanen-Guerra 2016, p. 273). However, it needs to be stressed that Cornell’s pacifist critique against aerial warfare in this statement and in the Crystal Cage collage would have largely been in response to propagandistic wartime media. As discussed previously, the American public was inundated with patriotic forms of advertising that extolled technological advancements in military weapons, in particular the power of U.S. fighter planes and precision bombing. This advertising was an essential part of morale culture, which aimed to lessen the nation’s fears by creating both a sense of distance and defensive safety against the destructive threat of war, particularly aerial attack. Moreover, the emphasis on the rational scientific basis of technological weaponry was used to normalize and promote military violence. Cornell sought to counter this brutal and deadly rationalist ideology through Berenice’s brand of visionary science, which rejected modern instrumental forms of perceptual knowledge in favor of poetic, enriching discovery.

The collage also contains two other elements with wartime content that have yet to be discussed in Cornell scholarship. Adjacent to the newspaper caption that reads “WAR GIVES A BREAK TO … BOY” there is another line of printed text that contains the partial phrase “45 Square Miles of Brooklyn to Be Darkened.” It was also clipped from a newspaper and most likely refers to the program of blackouts enforced by the government in New York City to protect civilian populations from aerial attacks. During the war, the media was largely responsible for inciting public fears regarding the threat of aerial bombing through articles that promoted the defensive strategies of blackouts and military camouflage. However, this reference follows the collage’s theme of the symbolic inversion of wartime content through the transformative power of Berenice’s stargazing. In darkening electric lights out of fear of aerial assault, the forgotten beauty and spiritual power of the starlit sky would be revealed, serving to reverse and ameliorate the terrifying reality of war. The playful newspaper caption along the bottom edge that reads “Rabbit Joins Battalion” may also allude to wartime media, specifically the use of popular cartoon characters like Bugs Bunny for war propaganda. A specific example is a 1942 animated musical short titled “Any Bonds Today?” that featured the iconic rabbit. The title of the film was based on the song “Any Bonds Today?” by Irving Berlin and was used to promote the Treasury Department’s war bond drive. In addition to Bugs Bunny, the patriotic short also featured Porky Pig and Elmer Fudd wearing military uniforms. The trio of characters sings Berlin’s tune against a shifting backdrop of patriotic imagery that includes a panoramic view of American military power in the form of combat vehicles, bombers, and naval ships.4 After the showing of these shorts, the lights of the movie theater were turned on and ushers would collect monetary contributions from the audience to help finance the war effort. An avid moviegoer (and filmmaker himself), Cornell was no doubt familiar with this short and other propagandistic fare commonly shown in theaters during wartime. An oblique reference to this cartoon film would have been in keeping with the collage’s theme of juxtaposing childhood experience with the darker realities of war. However, unlike the other examples, it is not purified and transformed by Berenice’s sense of hopeful wonder. In contrast, Cornell’s caption was most likely intended as a satirical critique of the government’s political exploitation of the innocent pleasures of children’s culture. Due to his antiwar leanings, Cornell would have also resented these war shorts, seeing them as the noxious intrusion of a corrupt reality into what he regarded as the tranquil, dreamlike realm of moviegoing.

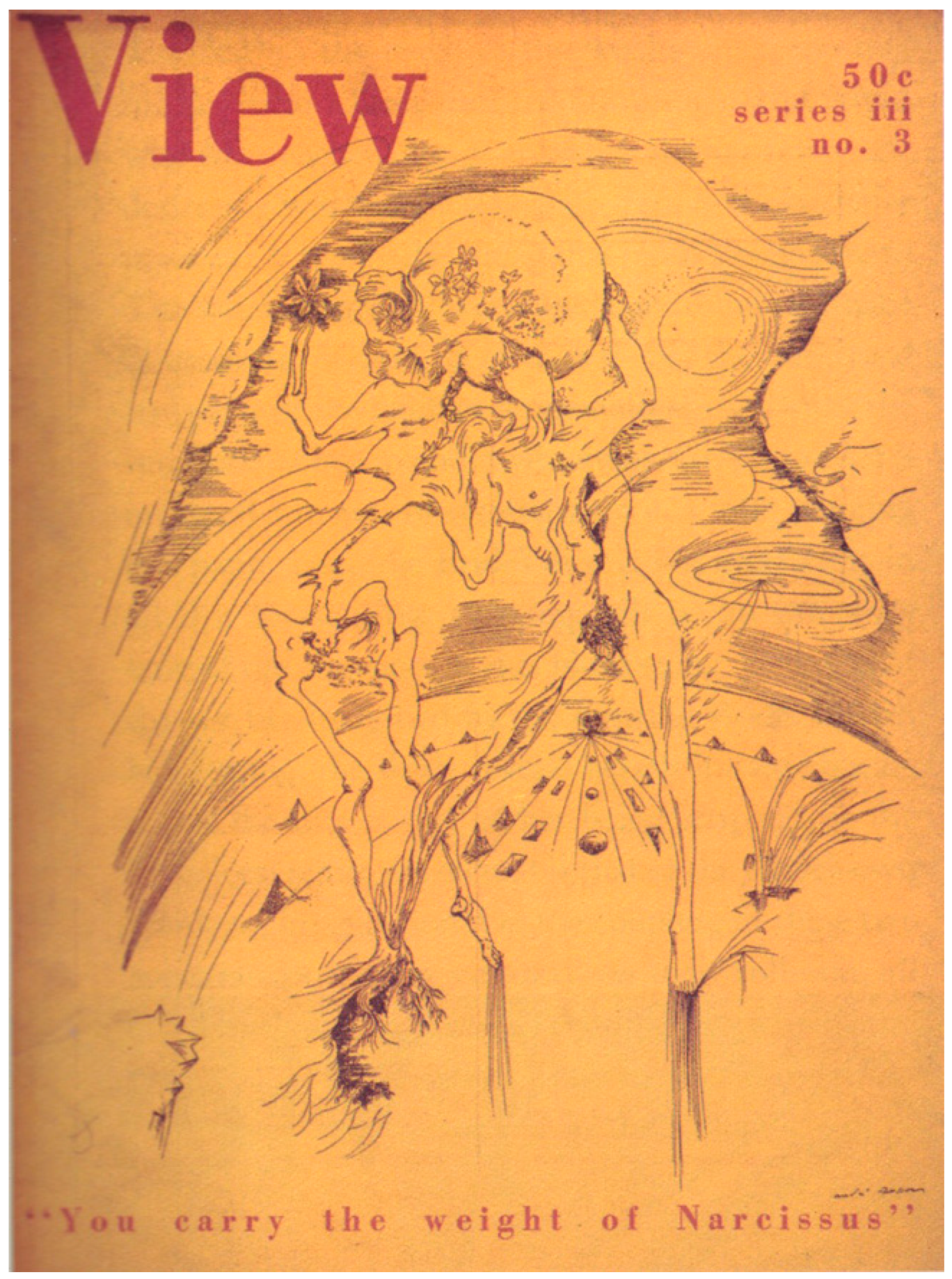

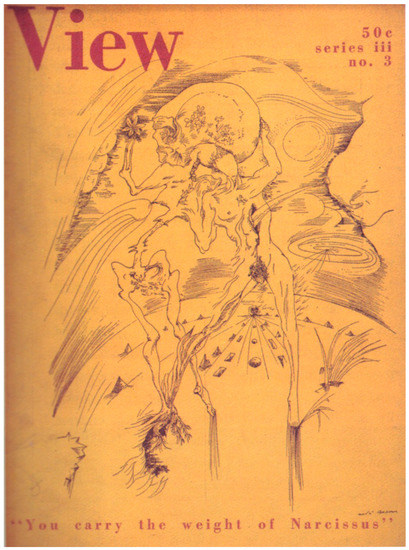

The final image to be discussed is André Masson’s drawing You Carry the Weight of Narcissus. It was used for the cover of the October 1943 issue of View, which was devoted to the Narcissus myth and its relevance to wartime culture (Figure 7). One of the major articles is by Wallace Fowlie. Simply titled “Narcissus,” it analyzes the theme of the mythical character’s self-absorption as symbolizing the psychocultural need for modern humans to examine and question their own complex inner natures “during the terrible present moment of living” (Fowlie 1991, p. 74). Following the myth of Narcissus’ reflection, Masson depicts his doubled image, which includes a somewhat frayed idealized body paired with a ravaged skeleton. During the period Masson executed this work, he advocated the political responsibility of artists to express the “disquietude” of their epoch. While living near New York, he also lent his support to various political activities at the Society of American Friends of France that opposed the German occupation of his home country (Poling 2008, p. 153). However, it is also important to establish the wartime meaning of this drawing through its connection to Masson’s larger production of Surrealist images that referenced his traumatic experience serving in the First World War.

Figure 7.

André Masson, You Carry the Weight of Narcissus, View, October 1943. © 2020 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris. Used with permission.

In his La mémoire de monde (1974), Masson presented a harrowing account of fighting in the trenches during World War I. After being shot and suffering a punctured lung, he lay in a trench alongside the ossified body of a dead German soldier. An attempt to remove him from the front lines was interrupted by an enemy barrage and the artist spent a terrifying night exposed and bleeding on the battlefield with gunfire and rockets exploding overhead. Suffering from shellshock and acute anorexia, Masson convalesced in psychiatric hospitals during the final months of the war (Shell 2018b, pp. 60–61). He never fully recovered from his war traumas, which continued to be expressed in the violence and brutality of his art from the 1920s through the 1940s. A prime example is his Massacre series of the mid-1930s; yet the violence and emotional intensity of his works increased during the early forties with the onset of World War II and his subsequent exile in the United States beginning in 1941.

To return to Masson’s View cover, it contains various symbolic traits that reflect the traumatic recurrence of the artist’s war experience. Narcissus, in particular the skeletal figure, exhibits extreme forms of bodily wounding. Throughout the 1930s, Masson’s figures contain recurrent references to butchered flesh, which he sometimes contrasted with invincible forms of bodily beauty, such as in Pygmalion (1938). Masson also acknowledged that the male figures in his works were seldom free of wounds, injuries, and mutilations (Poling 2008, p. 52). The drawing also depicts the figures standing on a curved barren landscape that is illuminated by the sharp, intense light of a radiant sun. According to David Lomas, similar forms of light in other ravaged landscapes by Masson resurrect the piercing memory of the detonation of a bomb or grenade (Lomas 1999, p. 41).

Masson’s symbolic treatment of Narcissus can be traced to many of the Surrealists’ depictions of the human body following World War I. As a means of acknowledging the human suffering and wounding resulting from the war, they rejected traditional bodily ideals of corporeal wholeness. As Amy Lyford has observed, the disfigured bodies in Surrealist art in the 1920s also countered the Third Republic’s conservative “return to order,” which ignored the actual bodily sacrifices made by French forces in the war (Lyford 2007, p. 6). Stemming from their knowledge of the socialist theories of Émile Durkheim, the Surrealists conceived of the political and the bodily as necessarily intertwined. This political somatics involves a dialectical mirroring where the health and vitality of the individual body refracts and reflects upon the integrity and robust strength of the larger abstract social body (Mukherjee 2010, p. 120). These Durkheimian notions lent themselves to more conservative ideologies that promoted ideals of a rational, stable, and unified social body, which were mirrored in the utopianism of the Third Republic. Many of these ideals were challenged by Surrealist artists through their radical and violent treatment of bodily form. This involved graphic imagery of bodily evisceration, which served as a metaphorical embodiment of wartime trauma and psychological disorder. The Surrealist poet Antonin Artaud wrote that one of the primary effects of psychic trauma is the fear of visceral abjectness that results in the loss of a unified bodily self (Juler 2016, p. 1). Images of the fragmented and eviscerated body were also employed by the Surrealists to represent disjunctive realities that defied rational visions of a secure and controlled social order.