Abstract

We are pleased and honored to include the keynote address delivered by award-winning Sičáŋǧu Lakota artist, Dyani White Hawk Polk at the Native American Art Studies Association Conference (NAASA) on 2 October 2019. The NAASA is the leading professional and scholarly organization supporting and promoting the study and exchange of ideas related to Indigenous arts in the United States and Canada. At the organization’s biennial conference in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and while standing on Dakota traditional lands, Dyani White Hawk Polk delivered her important address, “The Long Game.” In it, she movingly and powerfully explores her life experiences, the history of and ongoing effects of colonialism, and how both inform her artistic practice. Her address traces the roles of mentors in her life, including the late Ho-Chunk artist, Truman Lowe, who taught at the University of Wisconsin, Madison during her time in the MFA program. She eloquently speaks to the challenges she has faced in tackling head-on hierarches in the art world that have continuously sought to diminish the significance of Indigenous art. She also provocatively addresses how artists, scholars, and critics can build the field of Indigenous art and support Indigenous artists. The address was widely praised at the conference, owing to the power and beauty of her words, as she spoke to how the past effects the present and as she illuminated a path for the future. We are grateful to be able to include her address in this Special Issue of Arts journal. Her thought-provoking address is both an artistic statement and a profound and moving commentary on the state of the Indigenous art world.

I’m really grateful to be here today among all of you. I am grateful for the work that you do. Wopila tanka for your commitment to the field and, through this, to the health and well-being of our communities.

There are infinite ways that art contributes to the well-being of our world, and so many things I’d love to talk about with this particular group of people. It took me many anxiety-ridden days to decide what to talk about today. So, I defaulted to tackling this talk with the same strategy I use in the studio. I have learned that I do my best work when I start from the center, examining my own life experiences and then building outwards, using what I have learned to connect with other people, to culture, to community, and to our world. Through sharing some of the stories that have helped shape my practice, I hope to illustrate the importance of the work we are all here to celebrate, support, nurture, and further.

I will start by telling a couple stories about the man to be honored with the Native American Art Studies Association’s 2019 Lifetime Achievement Award, Truman Lowe. I was lucky enough to be a graduate student during Truman’s last two years of full-time teaching at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He was not my teacher in a formal sense, as he was faculty in the sculpture department, and I was in the painting department. Nonetheless, he was a mentor, and had profound impact on my graduate experience.

1. Truman Story #1

I was in a senior seminar class during which one of our assignments was to deliver a PowerPoint presentation on our lives. We were then supposed to tie our life experiences to the ways in which our lives affected our artistic expression. For me, this was pretty natural. My life experiences were, and continue to be, imbedded in my artistic practice in very direct ways. As a Native student, who came into graduate school after eight years of tribal college experiences, it was second nature for me to talk about my life as a Lakota woman—a Lakota woman who is also mixed, my father being German and Welsh American, who grew up in the city, got into hip-hop, rave, skate, and snowboarding youth culture; whose life story was affected by the adoption era and the long lineage of policies affecting Native people—and about how I learned how to bead before I learned to paint, and the multiple means of creative expression and life experiences, Native and non-Native, that influenced my practice.

Part of this assignment included an anonymous critique of our presentations by our peers. These critiques were handed to us as individual typed responses in a single envelope. The anonymity allowed my classmates to speak freely without the constraints of political correctness or potential judgment of their character. Through this exercise, I learned that some of my peers, although they all seemed respectful on the surface, harbored racist and prejudice views. I will never know for certain which ones they were. One response said that they simply didn’t buy my mixed-race identity and experiences as enough. There were a few more that really shocked me in how dismissive they were about my life experiences and the ways in which these were reflected in my work, but what really pushed this experience over the top was how my older, white male teacher responded to my presentation. He facilitated about fifteen minutes for group discussion and response to each of my classmates’ presentations, but mine was the only one that he took the remainder of the seminar class time to pick apart. It was at least two to three times the amount of time allowed for response to everyone else’s presentations. He asked me “What if all my art was about me being Polish?” in a manner that was condescending and meant to devalue the validity and worth of my story and my work.

I was livid, shaking and angry that I was subject to a class debate on whether or not my life experiences were valid, worthy of discussion, or strong enough to base my artistic practice on. Later that week I asked Truman if we could meet for lunch. I brought the envelope of student responses with me to show him. I remember shaking as I explained what happened, still so angry and hurt as I told the story to Truman.

For those of you who know Truman, you will understand why I’ve explained his persona to others as “Buddha-like”. He had the most soothing, calming, and serene presence. He emitted this Zen-like quality. My mind was spinning over all that had happened. I was on hyper drive, trying to figure things out. I was hurt that my peers had these undercover feelings and judgments towards me. I was caught in a mental loop, debating in my own mind, fighting for my own self-worth and the validity of my story.

Truman, on the other hand, just calmly shook his head, and in his Buddha-like way, he told me, “Dyani, don’t give these people any of your energy.” I don’t remember his exact words, but I remember his message. He argued that I needn’t spend any of my energy because, ultimately, their opinions on my story, my life, and my work would be inconsequential. Something about the delivery of this very simple message calmed me and made me instantly realize that he was right; that I did not need to take on or own their poor opinions and negative energy, and so I did not.

As a result of this experience, I formed some of my strongest arguments as to why my artistic voice is important, valid, and needed in the thread of Indigenous, U.S., and global artistic histories. During my years in tribal college, we studied how the government has systematically, and how the nation has consequently, ignored, diminished, and resisted the validity of our cultures, languages, world-views, life-ways, spirituality, families, and tribes, and now I was faced with the ways in which this history has permeated the arts as well. Once I was grounded again, in great part through Truman’s compassion and mentorship, the adversity I faced through this experience prompted me to dig in and begin to question and critique the rationales that had devalued and othered Native art and people.

In response, I started thinking about the value systems imposed over time to maintain the hierarchies of people and, therefore, the hierarchies of people’s art forms. It was through this that I realized how very absurd and groundless these arguments are. One of the fundamental ideas of why European and European–American (predominantly male) art has been understood as “high art”, and art forms made by women, black, and brown folks have been, more often than not, deemed as “craft” or “decorative”, is the idea that “high art” is founded in concept, and that these all-important concepts (male genius) have created generations worth of conversations over time, each generation building off and responding to the previous. These are the “art movements” we understand today. It was thought that our work, artistic expression created by Native artists, is “craft”. In their eyes, it’s functional and decorative, and therefore void of the greater conceptual underpinnings that denote “high art”. Furthermore, according to their value systems, Native art is also void of the materials that Euro and Euro–American societies have designated as valuable.

I was forced to deeply consider why my voice and my experiences were valid in relation to how the institutions of art (museums, academia, and the market) have defined and maintained hierarchical categorization through terms such as “high”, “low”, “craft”, “functional”, and “outsider” art.

It was an extremely freeing moment when I realized that these arguments are simply unfounded. Our art, like theirs, is deeply conceptual. It has always carried worldviews, profound knowledge, cosmologies, histories, family, tribal and regional stories, and these too are intergenerational conversations, each generation responding to and building off the previous. Like their art movements, we too have learned from masters. We learn the traditions of our art forms and create individual voices from within this lineage and build off those practices. Our works also respond to current trends, conversations, new materials and relationships. We too respond to the current environment. Native art also pushes back against old standards and continues to evolve and develop, and just as necessarily so, it also holds dear to traditions and knowledge passed down over generations.

Our works also speak through the elegant human language of abstraction and contain deep thought and meaning within coded and beautiful artistic practices, and like their work, we utilize elements and materials of deep value in our work. Porcupine quills, an art form gifted to the Lakota people from Anunk Ite, Double Face woman, is a sacred gift to our people. Buckskin, buffalo everything, elk teeth, are gifts from the deer, elk, and buffalo. They are gifts from life, from our relatives. Medicinal elements such as sweet grass in our baskets, copper in our adornment and vessels. Valuable gifts from the sea, such as dentalium, wampum, and abalone. The earth itself in clay, stone, and bark. Over time, this value system has extended to respond to new relationships that introduced new trade items such as beads, cotton calico fabric, wool, and snuff-can lids. Today, still trading for items of value through which we continue these intergenerational conversations within our art, we have thoroughly incorporated items such as fine satin fabrics, shawl fringe, ribbon, rhinestones, canvas, acrylic and oil paint, paper, pens, bronze, glass, digital media, film and video; the list goes on.

Their work, like ours, has function. Even if the function is simply to pick apart the last art movement, it too serves a function. Its function is often intended to provoke and move an artistic conversation forward. The idea that functional art cannot carry deep and significant concept and thought, and that conceptual art is devoid of function, is shortsighted at best.

Another important realization during graduate school that continues to inspire my work today is the general ignorance on behalf of the American and international public about our histories and existence as Native people. One of the biggest barriers Native artists and Indigenous people at large face is the public’s lack of exposure to our histories, communities, culture, and the full spectrum of our artistic lineage. The vast majority of non-Native people have not been privy to the language and stories embedded in our art forms. Curators, panelists, jurors, collectors, and the public are not familiar with the generations of conversations stitched, carved, woven, painted, sung, danced, and written into these works. Therefore, they often cannot see and unpack the concepts. They cannot pick up on the visual cues and knit the ideas together that help them “read” the work and, through this, recognize the deep worth and value of what is presented.

This often feels like an insurmountable obstacle, until I realized this is, once again, similar to mainstream arts. The group of people that truly understand all that is embedded in those intergenerational conversations within mainstream art movements is also a privileged, small, and particular group of people. It is limited to those who have invested time into studying, learning, and actively participating in mainstream artistic culture—which also means that, through education and effort, the histories and context to understand Indigenous art can also be learned. Our work, like theirs, has a great deal to offer, and I would argue that the work of Native artists, Indigenous artists globally, and those who provide educational opportunities based on this work, is desperately needed today.

This is not meant to say “Hey, look, we’re just as good as you because we’re doing the same thing!” It is not meant to hold our work up against their standards and value systems in order to prove the worth of our own. The context of our artistic pursuits historically was, without a doubt, very different. Our value systems then and now are, more often than not, conflicting, but it is meant to counter the arguments used within the field that have positioned Native art as lesser than, or something to put in another room. The arguments simply do not stand up, and any curators or museum administrators that continue to perpetuate this segregation of Native art from the art of the rest of the world are not thinking deeply enough. Do we have a unique story to tell through our work that, at times, is deserving of its own stage? Without a doubt! However, we are also a part of the global community and our artistic expression is a part of a global human conversation. Therefore, it too should be among the galleries simply labeled as “Art”.

In my heart, I already knew this. I know the power, strength, and worth of our work, but it is freeing and beneficial to learn the language and stories within the mainstream arts field in order to be able to argue in the language and begin to break down divisions so that the “arts” in the future are recognized as a valuable human practice. It is useful so that we can push back and begin to break down and dismantle the ideas of “us” and “them”. Our art institutions are public spaces, funded through public funds, meant to cater to the public. They should do just that—reflect and cater to us all.

About seven years after that senior seminar class, I returned to the University of Wisconsin as a visiting artist and guest lecturer. That same faculty member saw me in the hall, walking with a colleague of his. He greeted his colleague and pretended he didn’t see me. He did not attend my talk. He most obviously still was not fond of me. It made me laugh a bit at the absurdity of the situation, and made me sad for him, knowing that he had to live with that kind of bitterness, but I had learned not to reciprocate his negative energy with any of my own. I learned to save it for positive opportunities to build and connect, and yet, it felt good to know, and for him to see, that my story does matter. My invitation to speak as visiting artist was proof that his racist, curmudgeonly ways were not going to win the battle.

2. Truman Story #2

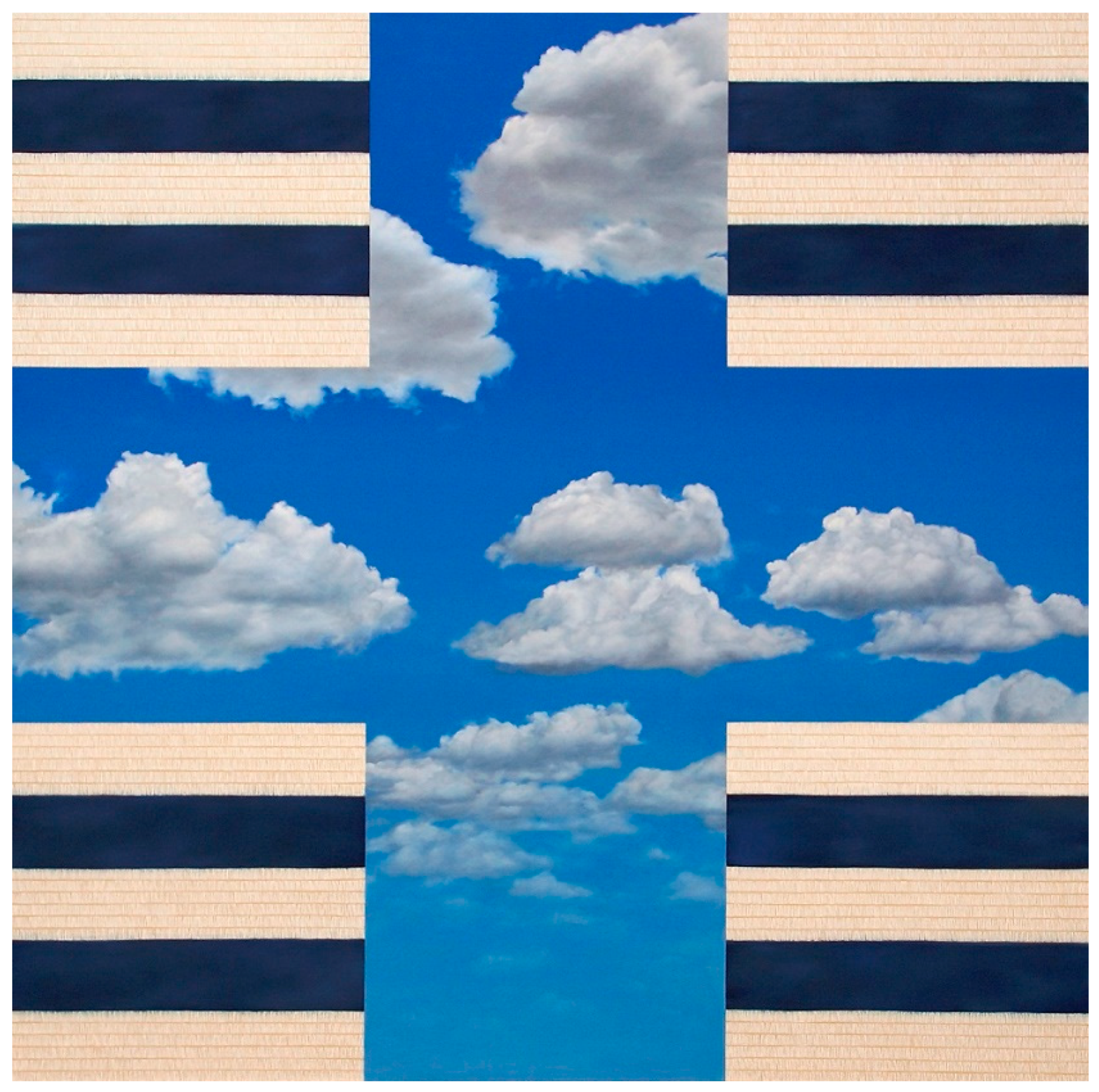

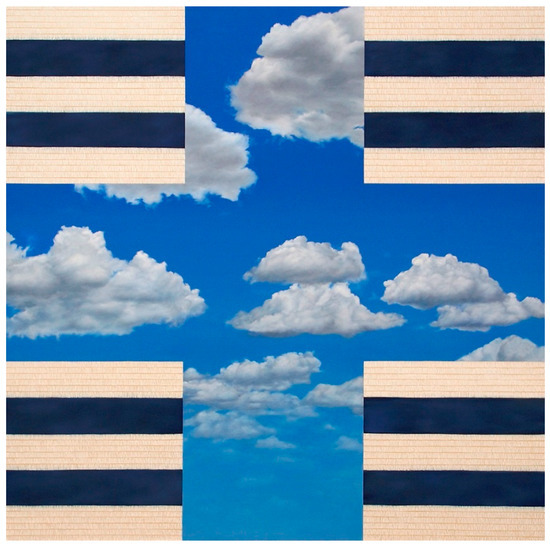

On the night of my MFA exhibition, Truman stood in front of my painting titled “Seeing” (Figure 1). He was standing there alone, taking it in. I walked over to greet and visit with him, grateful that he was there. He had already retired by this time. I stood next to him as he stood looking at the work. He had a sense of joy and awe in his expression. He handed me a little tin box. He had sanded this box down to a beautifully brushed tin surface and made a perfectly formed padded bed inside the box with just enough room to lay a single quill. As I held that box in my hand, already filled with gratitude for receiving such a meaningful gift, with a smile on his face, looking up at that painting and then back to me, with that same Zen energy he told me, “You never have to quill again, if you don’t want to.” He didn’t mean that I shouldn’t. He wasn’t dismissing or devaluing quillwork. That amazing box dedicated to a single quill demonstrated that, but I believe that, through that gesture, he was validating the strength of my painting and the legitimacy of its connectivity to our cultural continuity.

Figure 1.

Seeing, oil on canvas, 2011, courtesy of the artist.

I didn’t realize it fully until I wrote this speech, but in that single gesture, he exampled to me the concrete truth of the very arguments that I had to formulate in order to defend my work within and navigate a mainstream academic environment.

Truman’s presence was a gift. I cried when I learned he passed, knowing how much so many others and I would miss his good energy and leadership, but I went out, I put my tobacco down, I prayed for his journey, and I thanked him deeply for all he did.

3. Mentorship and Role Models

Like Truman, it is imperative that we have Native and Indigenous mentors and role models. Truman was one of a small but strong group of mentors I had through my graduate school experience. I was lucky enough to attend the University of Wisconsin–Madison at a time when we had three Native faculty in the art department and one in art history. Truman Lowe, Tom Jones, John Hitchcock, and Nancy Mithlo collectively created a grounding foundation as I learned to navigate the broader art world and turbulent, problematic, deeply flawed, and simultaneously wonderfully inspiring and enriching waters of mainstream higher education.

I am thrilled to sit in this room today, filled with Native scholars and artists and non-Native scholars excited about supporting Native artists, because I know how desperately important it is that our youth have people they feel a connection with to look up to. As humans, we need to see ourselves reflected both within and beyond our immediate communities. We need to be able to look at an instance when someone like us has achieved similar dreams, and I believe it is important that we see instances when both our communities and the world responded.

The reality is, for Indigenous people in the arts, the opportunities for this are few and far between. The accessibility to role models who have been highlighted and celebrated in our larger public institutions is very limited. The same can often be said for our local arts communities. We can’t turn on the television, go to the movies, look in Art in America, Art Forum, ArtNews, etc., stroll the halls of MOMA, the Guggenheim, National Portrait Gallery, the Walker, or, until this year, the Whitney and regularly see examples of Native folks like us that have received support for their practices, parallel to that of their peers.

There have indeed been tremendous strides made by Native artists and arts practitioners, especially in these past couple of years. The inclusion of Nicholas Galanin, Laura Ortman, Jeffery Gibson, Sky Hopinka, and Jackson Pollys in this year’s Whitney Biennial is an example of this. As is the tremendous recognition of the MacArthur Fellowship that Jeffery Gibson just received, Candice Hopkins’ curation of Documenta 14 and the Toronto Biennial, the recent media attention and support of the Hearts of Our People exhibition, Post Commodity’s recent commission by the Art Institute of Chicago, the recognition of Beyond Buckskin, the B. Yellowtail Collective, and other Native designers in the fashion industry. I am preaching to the choir here, but it is important to celebrate these awesome achievements and emphasize that these achievements are wildly overdue. They only just begin to crack the surface of what Native artists have to offer. Likewise, these accomplishments only just begin to present the level of support these artists deserve. These examples are also limited and present only a very small sample of the abundant population of Indigenous artists out there doing important work, deserving of wider recognition and support.

I am so damn grateful to have attended the Institute of American Indian Arts where I had the opportunity to be introduced to artists like Oscar Howe, Arthur Amiotte, Truman Lowe, Helen Hardin, Maria Martinez, Juan Quick-to-See Smith, Joyce Growing Thunder Fogarty, Jamie Okuma, Roxanne Swentzell, T.C. Cannon, Fritz Scholder, Emmi Whitehorse, Brian Jungen, Marie Watt, C.Maxx Stevens, Rosalie Favell, Teri Greeves, Rebecca Belmore, Jim Denomie, Harry Fonseca, etc., etc., etc., and the countless artists whose names were not recorded whose works I have studied in collections. I so needed these role models during the development of my own artistic voice, but, it was glaringly apparent when I began grad school that none of my peers had heard of any of my art heroes.

Meaning, there is still much work to be done!

But, we all know this, right? So, how do we tackle it? Well, unfortunately, I don’t have the answer, but I do have a list of a few points I would like to encourage you all to consider as you go forward and pave the way for others to follow.

We absolutely need to uplift and support one another. I can’t talk about the why, but I do know that a part of our historical trauma plays out in jealously in our communities. We tear each other down. We have become quite good at the art of neo-colonialism. We compare, pick apart, and find reasons to diminish or devalue our work or one another. We suffer from crabs in the bucket syndrome, the “Gee, she’s too much” syndrome, but when we do this to one another, it’s not just the crab that got pulled down that suffers. It’s all of us. We need to see the light of others so that we might feel permission to shine ours. We need those role models, those mentors, teachers, and colleagues. We need to work on lifting one another up, collectively hoisting one another so that we can turn around and offer that hand to help pull up the next climber. We must work to break down patterns of jealously so that we can collectively thrive. What are you doing to lift up the climber behind you, or your colleague sitting next to you? How are you championing and cheerleading the work of your peers? How are you providing opportunity for other artists? To our male relatives, how are you actively supporting the recognition and support of your woman relatives? How are all of us supporting our LGBTQ and non-binary relatives? How are we collectively building our self-worth? After generations of oppression, this work is vital, and folks, there’s room for all of us. There’s not a Native artist or Native academic cut-off. We won’t be penalized for having more than five players on the field.

- We can be supportive of one another without loving one another’s work. We can champion success and acknowledge the worth and value of another’s contributions without committing to hanging the work in our own living room. I don’t have to love your work for me to want to see you succeed and prosper. It doesn’t have to be my favorite for it to have value.

- We can be supportive of one another without being one another, mimicking one another, or forcing others to fall in line with our particular beliefs and practices. We do not need to collectively agree in order to still be respectful, compassionate and supportive. I was visiting with a friend, fellow artist and poet, Layli Long Soldier this summer. We were discussing how, as Native artists, we can, at times, over identify with one another. This can become another form of crabs in the bucket. We are quick to criticize someone if it seems their way of walking through the world or their ideas on artistic production are not in line with ours. She talked about how she had been thinking about the fact that there is no one way to be Lakota. Just as there is no single way to be Choctaw, Anishinaabe, Menominee, etc. We are tribal citizens, we are connected to our communities in very real ways, but we are also individuals. The ways in which we receive our tribal names and the recognition of our individual roles within our communities through these names is a beautiful example of the ways in which our tribal structures recognize the worth of the individual as it pertains to the collective. We are not autonomous, but we are unique. I was talking with another friend and fellow artist, Inkpa Mani, last week. He mentioned that, in his research, he ran across a name of someone in the past whose name translated to “Doesn’t Make Them Happy”. We both chuckled at the realization that the name given to that man may have sounded negative but, as our names honor our roles, in reality it possibly signaled a strength within that individual to speak the truth or act on what they believed in, whether or not it made people happy.

- On that note, constructive criticism can be a form of support. As we work on communal support, we can foster and grow increasing self-worth and confidence. We can build each other up and become tough through that love, as opposed to the toughness and defensiveness we develop in response to trauma and rejection. We would then be in a better place to receive constructive critiques. We need this kind of writing on our work. We need critical thinking and introspection within the field and amongst our peers, but also to position our work among the field at large within the global discussion. When done in a way that encourages growth, the importance of constructive criticism cannot be underestimated. We need to cheerlead and champion one another, but this does not mean it is helpful to apply this as a blanket practice for every situation. There are times we need to be willing to participate in tough discussions and listen to one another for the sake of growth. We should be collectively striving for growth, holding one another accountable for a commitment towards excellence, and supporting one another on that path. Our work should be continuously evolving and, at times, the voices of our peers can help us get there.

- Get that degree. Write that application. Submit that article. Apply for that residency. Write that book. Even when, and especially if, you don’t see any Native people previously represented in that space. It is entirely possible to base your entire career off and survive within the Native arts field, and if that is what feels right to you, and you know it’s your calling, then I fully support you, but if you feel this world has not given Native artists their due recognition, and if you crave to see our artists, authors, curators, directors in public spaces outside of our immediate field, then you must be willing to reach beyond the cozy familiarity of places and people that have already committed to supporting us. I crave to see Native voices among the national and global dialogue, and, not every once in a while. I want a regular diet of it, but that means that I, and others, must be willing to go into those unsure waters and make our voices heard. We’ve got to be willing to take the risk and push beyond our comfort zones.

4. The Importance of Historic and Contemporary Art Forms and Everything in between

My mom was born during what is now understood as the Adoption Era. She, along with approximately one-third of all Native children between about the 1940s through 1978, the year the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) was enacted, were adopted into non-Native, European–American homes. My mother and her siblings all experienced some form of removal, whether it be through adoption, foster care, or boarding school. As most of you in this room know, the lasting effects within our communities as a result of these governmental assimilationist policies have been devastating.

It is also important to note that the removal of Native children continues. In Minnesota, a Native child is twenty-four-times more likely to be removed from their home than any other race in the state. This is the highest in the nation. In speaking to my mother, she shared that child welfare workers are reporting that removal rates are nearing what they were pre-ICWA. My mother’s life experiences have now become her life’s work as she advocates for Native adoptees. She works with judges and social workers to help educate them on the unique circumstances and needs of Native children and works with tribes to help facilitate efforts to welcome back their relatives that have been adopted out.

Before all of the work she does today, she experienced the trauma of adoption. My mom was adopted off the Rosebud reservation at eighteen months old and relocated to a small town in Wisconsin. Adoption stories are widely varied, but my mother’s was not a happy or healthy placement. Her adopted father died when she was six and she was left with a mentally unstable and abusive adopted mother. Like many people who endure trauma in their youth, she turned to self-medication. She fell into addiction and this was the time in her life in which she also met my father.

Her life had become very unhealthy and it wasn’t until I was five years old that she began her journey of healing. She realized she didn’t want to continue with life as it had been and decided she needed to get sober. It was during the work that it takes to maintain a life of recovery, which included divorcing my father, who at the time was not ready to join her in sobriety, that she finally realized a huge part of the hole and pain in her life was the disconnect from her biological family. So, when I was eleven, my mom made her first trip out to Rosebud to meet our family. She has done everything in her power since then to make sure that I did not suffer the same disconnection from who I am as a Lakota woman that she endured.

I was raised in Madison, WI, in the city, ten hours from our family in South Dakota, but I was raised among the Native community in Madison and surrounding reservations. Our childhood and lives today continue to be an ongoing cycle of traveling back and forth between the Midwest and the Plains.

Art has helped facilitate much of our healing. As a teenager I sat with Ho-Chunk and Diné, friends of my mother’s in Madison and learned to bead and sew. Many people within the Madison area Native community ate together every Sunday, gathering at the Wilmar Center for weekly potlucks where men and boys would practice singing, boys and girls would practice dancing, while others of us beaded, worked on our regalia, or just visited and played. I still bead using the same beading tray Mary Funmaker gave me when I was a young teen.

My mom started dancing and learned to make her dress and regalia. I helped her in this process. She was later asked to join the Oneida Nation Color Guard. My mom is a Navy veteran. By the leadership of Dan King, the Oneida Nation Color Guard was the first color guard to recruit women veterans. My mom was one of those women veterans. Her participation in the circle, the ability to dance, hearing and moving to the drum, the ability to wear her regalia and fully embrace who she is as a Sičangu Lakota woman facilitated much of her healing. She now knows the value of being welcomed into the circle and she utilizes that experience to offer opportunities for returning adoptees to also be welcomed back into the circle in their home communities.

I believe in many ways art has saved my life. I was always drawing as a young person, always making things. The first art competition I ever entered was through the National Indian Gaming Association. I received a first-place prize in photography for photos I had taken while at home in Rosebud.

I received my Associate in Arts degree from Haskell Indian Nations University and then my Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA). While at IAIA, I immersed myself in the painting program as I knew for many years that I desperately wanted to paint, but I was also so grateful to be able to take traditional arts classes and continue to gain new skills and refine those I had previously learned. I learned how to make parfleche boxes and envelopes, learned how to do porcupine quillwork, made my moccasins, leggings, hair ties, and bag that I wore during my graduation and still dance in today. At the same time, I was learning Native history and Native art history. I was simultaneously practicing our long-standing artistic practices while also forging my own voice as a practicing studio artist. All of this helped heal the pain in my own heart of our removal from our family and the realities of what it means to grow up being a mixed kid.

Because of our separation, I did not go through our Isnati or womanhood ceremony, but I cried at the table as I made all the items necessary for my oldest daughter to participate in hers. I cried because it was an illustration of how we had come full circle; how they were not successful in this assimilation project. My mother did not, but I knew how to make it all. I made my daughter’s dress, her moccasins, leggings, awl case, and parfleche belt and hair ties. Then I taught her how to make her parfleche knife sheath, earrings, and bag. I taught my husband how to make her a necklace and our friend gifted her with a shawl.

I, like so many of us, am tired of the dichotomy of traditional and contemporary. My friend Joe Horse Capture and myself wrote essays, created a catalog, and curated an exhibition in 2011 titled Mni Sota, Reflections of Time and Place. In this work, we emphasized the reality that all work is contemporary when it is made. The work of our ancestors was contemporary. All work is a reflection of time and place. I do not believe our work is either or.

We have long standing artistic practices—traditions—that are of utmost importance to continue to practice, nurture, and learn from. These practices bring with them teachings that ground us in who we are, that directly connect us to our ancestors, our relatives, and the land. To abandon these practices, quite literally, is cultural suicide. We would inevitably loose fundamental knowledge and teachings that support our cultural practices as Native people.

Likewise, we also have long standing practices of experimentation, continuous adaption, and incorporation of new elements and ideas into our artistic practices, and these are just as vital to cultural continuity as the older practices. Culture must move to live. If a culture becomes stagnant, it is no longer reflective of its environment and, most likely, will no longer thrive. I love looking in collections and finding those pieces by artists who busted out and tried something new. Beaded Mary Janes, hot pink quills, designs that are so original you laugh when you see them simply because they get extra cool points for their innovation. Our ancestors fully incorporated new items like beads, wool, sequins, ribbons, and now, elements like Jamie Okuma’s, Louie Boutin’s, or Razelle Benally’s camera equipment support the ongoing artistic expression and cultural continuity of our people.

We need all the artists. Those dedicated to ancient knowledge. The ones that know how to harvest, tan hides, gather clay, weave, care for sheep, pull and clean quills, sing, dance, etc. We need those folks because those teachings are such a fundamental part of who we are as a people. We also need the artists who push the boundaries and experiment; shake it up and try all the new things. We need these folks so that we can continue to adapt, evolve, and grow. So that we do not stagnate. So that we do not lose our youth in the mix and appeal of the fast and the new. We also need all the artists on the entire spectrum between these extremes. We need them all.

If I could just make a quick plug, we also need Native art historians. We seem to have fairly steady growth of younger Native curators entering the field, and this is so exciting! We need you too, but we also need those that will dig into and learn about Native art history and art history at large. We need Native people with this knowledge so that anthropologists don’t continue to be our primary source of curators in large institutions. No offense to our friends, because we are grateful for your work, but Native voices as leading curators of historic collections, as well as curators of and leading academics addressing both historic and contemporary arts, is a gap and a need.

5. The Unique Gifts We Have to Offer from Work Rooted in Our Value Systems

I mentioned earlier that I believe the world desperately needs the work of Indigenous artists. Most of you in this room can easily draw your own conclusions as to why it’s important that the world hears from Native voices.

I want to emphasize the importance of work that is rooted in our value systems. I’m going to utilize a story that doesn’t seem as directly related to the arts, but bear with me. My family plays takapsičapi, or Creator’s Game. It is the original, indigenous version of the modern game of lacrosse.

The teachings of this game essentially promote the acknowledgement of the worth of everyone. In the story of the game, the smallest most seemingly insignificant animal, who no one wanted on their team, scores the game winning goal. It speaks to the value we all bring, no matter our size, inherent gifts or talents. We all have something to offer. When we play this game, we are to remember that everyone on the field is valuable. The game is very competitive, but it is grounded in ceremony, so it is competitive and tough, guided by respect for our relationships, between male and female, young and old, small and large, etc. The game is rooted in prayer and treated with the respect of ceremony. Like art, it has medicinal qualities and the ability to lift our spirits, bring joy and inspiration, and cultivate community connectivity.

This past weekend, a game was hosted by the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior in Cloquet, Minnesota. After the games, our hosts provided a feast and a give-away, but instead of the usual give-away protocol, this time one of our hosts, Roxanne DeLille, told us to pick a gift, keeping in mind that we too would gift that item to someone else after our meal. We were instructed to put our prayers and good intentions into that item and think about the person we would gift the item to. After we ate, we gifted the items to the people we chose, now filled with prayer and thoughtfulness. I noticed that many gifts kept circulating as people felt inspired to continue to recognize the value of the relatives and community that surrounded them. Roxanne then spoke about the practice of sending knowledge forward, as it was done for us. She explained the proof that this was done was in the very game we had just played. The knowledge of that game and the teachings that accompany it were sent forward to us. It was in the song she had just sung for us and the practice of the giveaway. Listening to her, I thought about how it related to our ancestors’ knowledge of the need to think and make decisions with at least seven generations in mind. It also made me think about their deep understanding of concepts such as Mitakuye Oyasin, the Lakota language used to express the understanding that we are all related. This concept recognizes that the health and well-being of one individual affects the health and well-being of an endless network of people and all life. The arts have the ability to influence thought, to broaden one’s consciousness, to sway public opinion, and promote critical thinking.

Our ancestral teachings provide us with a set of value systems that guide our lives. I strive to make my life choices guided by Lakota values. I, like many Native people, recognize there is no separation between art and life. Therefore, these same values guide my work.

So, I ask you all to consider, how are you incorporating your value systems into your work? Do you find yourself adhering to mainstream or western art values when you are writing? When you are painting? When you get ready for the day? When you address an audience, do you cater to those value systems, or do you uphold your own? Do you think about when it is ideal to strike a balance?

What teachings do we hold that we can let guide our work in a way that benefits the world at large? For me, the value of being a good relative is a compass. I think about how I want my work to operate in the world. What do I want it to do? What do I want it to do for Native audiences? What do I want it to do for non-Native audiences? What do I want it to do beyond my lifetime, as I send it forward?

For me personally, the goal is healing. Embedded within the abstraction of my work are hard conversations about the truth of our nation’s history, tribal and federal government relations, within and beyond the arts. I believe it is important to speak about these truths because it is not being taught. I believe we cannot heal unless we recognize the entire truth. There is no healing in half-truths. I believe facing the reality of our history is beneficial and necessary, not only for Native people, but also for the nation and our world.

Being a good relative is an inclusive understanding. So, I utilize my work as an effort to create opportunities for education and conversation. I prioritize Native audiences because, for me, that is home, but it is also where I see the largest gap of representation. I also speak to non-Native audiences and strive to create opportunities for cross-cultural education and engagement. I strive to create opportunities for connection and healing. This is why my work speaks first through beauty. Beauty possesses medicinal qualities. It is a common human language we all speak. It is something we all crave and we are filled by. This is part of the work I want my work to continue to do. I feel it when I visit the collections and see the work of our ancestors and I know how impactful that feeling is. I seek to create work that we recognize first in our bodies and second in our minds. All of these decisions are guided by our value systems. This is just my example, but there are countless numbers of Native artists that understand and carry out this practice in their own way. This is the kind of work that teaches us how to respect one another, the land, our human and non-human relatives; how to think critically about our value systems and how we assign value; how to recognize the value and worth in the spectrum of human experiences; how to seek balance and recognize and cherish the intricate balance and the infinite mysteries of creation. Our world needs this now more than ever. How do we push back against the inherent elitism, pretentiousness, and hierarchical practices within the art world and stay grounded in our values?

This is the long game. It is all too easy to get caught up in the trends of the day. The art world, and our daily consciousness now, is polluted with ever-shifting trends. We must continue to push ourselves towards the greatness we know our people possess and have demonstrated for time eternal. The ability to inspire change is necessary on a small scale, a large scale, and everywhere in between. Activism comes in many forms. We can’t all play the same role, but like Creator’s Game teaches us, we can all contribute.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).