Abstract

“Metaphor to Métier: Kerry Tribe’s Aphasia Poetry Club and the Discourse of Disability in Contemporary Art” explores a 2015 video work by Los Angeles-based artist Kerry Tribe. Tribe’s “The Aphasia Poetry Club” embodies a shift in contemporary artistic discourse around concepts of physical and cognitive disability. Created by a neurotypical artist, the work uses the medium of the moving image to interpret the experience of aphasia, a neurocognitive language disorder frequently associated with traumatic brain injury. Three distinct visual idioms capture the particular neurological profiles and linguistic patterns of Tribe’s chosen participants. Tribe’s representation of people living with aphasia disrupts ableist conceits about the human capacity for memory and language. Rather than stigmatizing individual impairments, the work is indicative of a new aesthetic arising from disability experience. The article argues that disability no longer functions in the contemporary art world as a political or spiritual metaphor, but rather has become a site of formal invention and conceptual research.

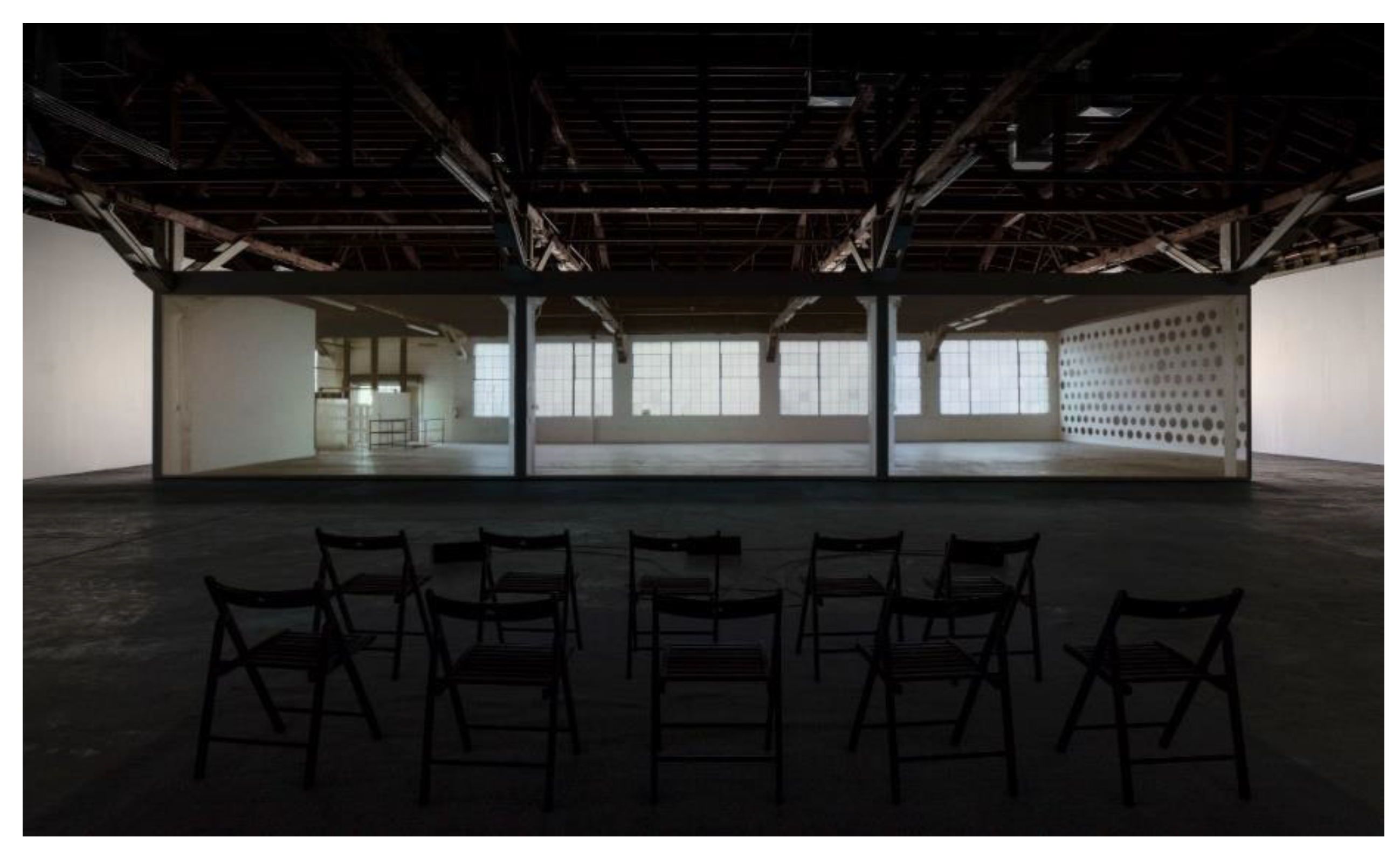

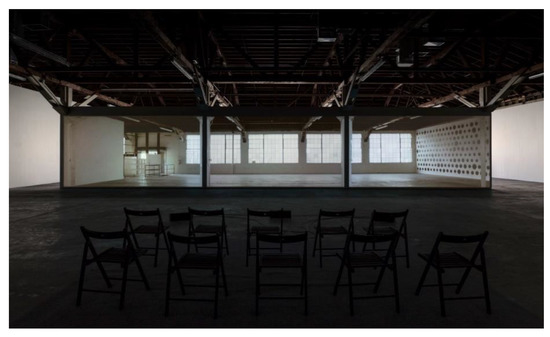

“Five six seven eight nine zero test out.” So begins Kerry Tribe’s three-channel video, The Aphasia Poetry Club. A male voice counts up from five against a panoramic shot of the same open warehouse space in which the work was originally shot, the now shuttered Los Angeles gallery 356 Mission, as shown in Figure 1. The sound test that introduces the work bears a double significance within the context of Tribe’s film. Sound testing exists as part of the filmic apparatus—a self-conscious nod to the mechanisms of the medium in which the artist works. But a sound test is also a hearing test from a position of privilege, when what is being tested is not the reception of sound but its production. Tribe’s test situates the film in a phenomenological horizon in which the medium of film comes to express the physical difficulties and compensations experienced by individuals with aphasia, a neurocognitive language disorder frequently resulting from strokes or serious brain injury.1

Figure 1.

Installation view of Kerry Tribe, The Aphasia Poetry Club (2015), 356 Mission, Los Angeles. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

After a brief cut to black, the same narrator introduces an animation sequence, as seen in Figure 2, set to old-timey music with the words, “I was born in Kindiana. My mother was Comanche painting. She could speak with only birds, but birds for sure.” Evident in the first two lines are examples of paraphasias, common indicators and products of aphasia, where difficulties with word finding result in the substitution of an incorrect word (painting for person) or neologism (Kindiana) (Sarno 1998, p. 29).2 An animated yellow bird hops and flutters cheerfully along a chalky white landscape outline as the narrator, in language that switches between halting and melodic, describes his mother’s quasi-Franciscan gift.

Figure 2.

Kerry Tribe, still from The Aphasia Poetry Club (2015), three-channel video with sound, 28:27 min.

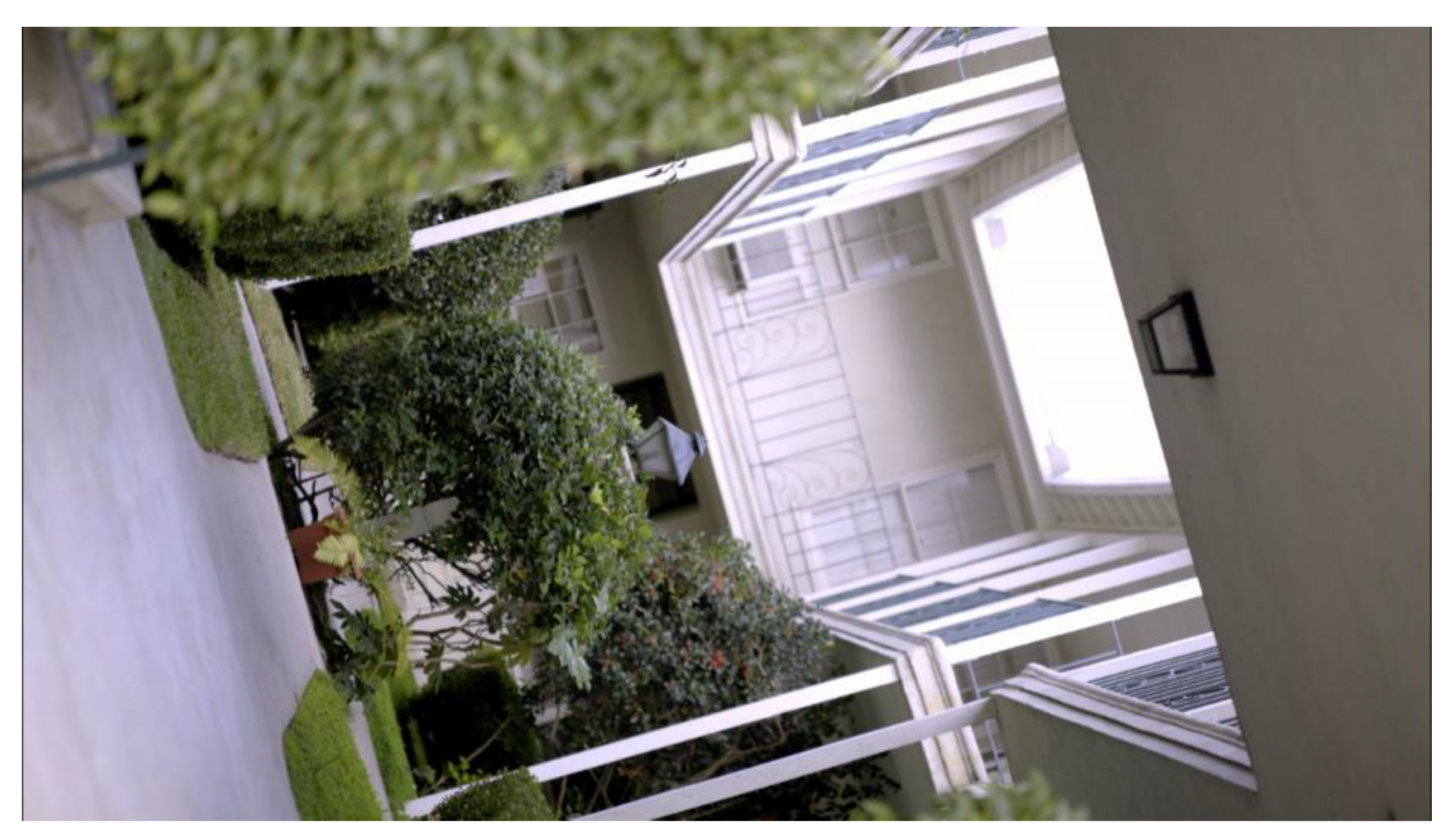

After a brief fade to black, a female voice begins speaking over sequenced shots of a domestic interior. She offers a very different origin story, which begins not with tales of a magical childhood but rather a fall in the shower. Images of the apartment interior and exterior alternate on the screen as the speaker talks about another incident where she fell into a bush, not realizing that the bush was in fact upright, but she was “actually going crooked”, as depicted in Figure 3. An image of the offending bush fades into a sequence of rocks and meteor formations as another male voice states, “I collect rocks.” His statement is straightforward, but his speech is more audibly slurred than that of the other two speakers. The viewer can by now surmise that none of these voices belong to neurotypical individuals.

Figure 3.

Kerry Tribe, still from The Aphasia Poetry Club (2015), three-channel video with sound, 28:27 min.

As the film continues, the voices of the three speakers alternate. Laura Romero, a woman suffering from a rare stroke disorder known as Moyamoya, narrates specifics of her clinical experiences. She recounts having “strokes after strokes after strokes.” She describes undergoing cognitive testing and confronting the limits of her own word-finding abilities with self-deprecating humor, interjecting “come on, starfruit?” when describing an early diagnostic scenario where she was unable to name any other fruit.3 Yet Romero goes on to associate star fruit, as seen in Figure 4, with a recollection of her mother, thereby subverting the more obvious concept of language deficit in favor of something more psychologically and figuratively allusive.

Figure 4.

Kerry Tribe, still from The Aphasia Poetry Club (2015), three-channel video with sound, 28:27 min.

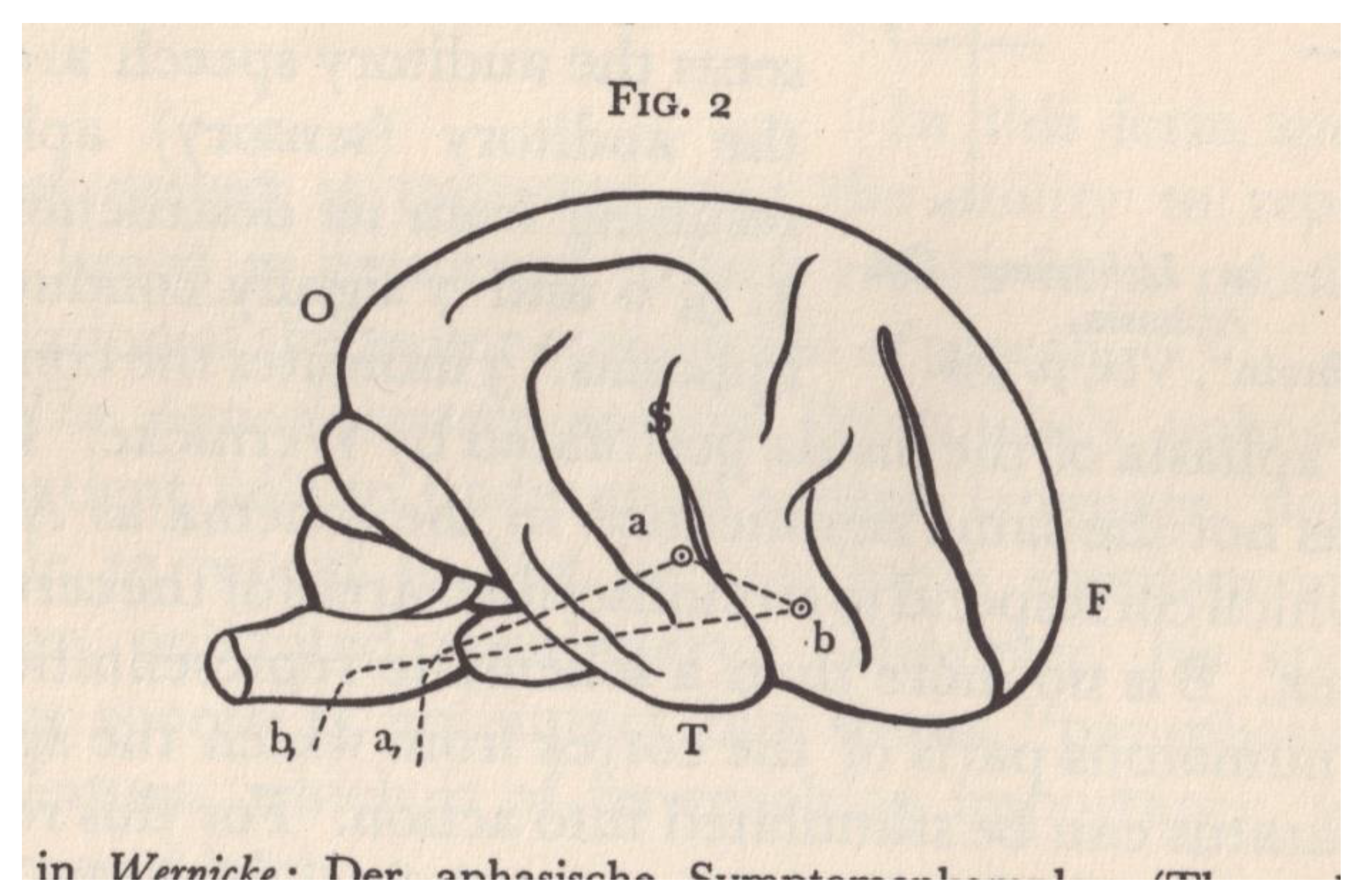

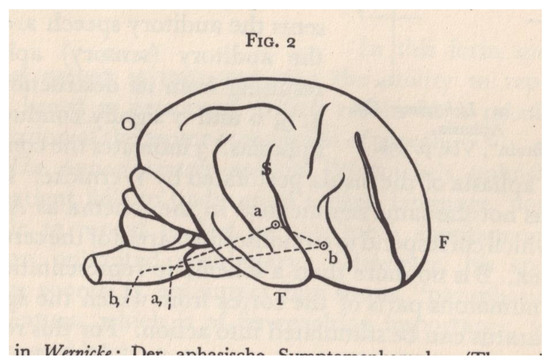

Romero explains the variations in the neurocognitive language disorder, known as aphasia, that the three speakers share, distinguishing between impairments affecting the production and reception of language. She is the only speaker to describe her diagnosis and aphasia’s physical symptoms in detail, so her fluent speech functions as a sort-of stand-in for the clinical voice. Reinforcing her expository role, diagrams from Freud’s landmark early study “On Aphasia” accompany some of her testimony, as shown in Figure 5 (Freud 1953). The situated nature of the images that accompany her speech seem commensurate both with her distinctive viewpoint and the concreteness of her language, which even when speaking figuratively is imagined in physical terms: “I want to get there,” she repeats, when referring to her attempts at word selection and language recovery.

Figure 5.

Kerry Tribe, still from The Aphasia Poetry Club (2015), three-channel video with sound, 28:27 min.

In the opening sequences, kaleidoscopic, multiplying images of the windows in the gallery where the work was originally screened mimic Romero’s vertiginous de-orientation, yet her concerns are more psychological than physical. She remembers thinking, after a doctor tells her 50% of her auto-processing has been lost, “Am I half myself now?” But this is not a film in which disability figures as loss or lacunae, and Romero insists, “there’s more of me there…I know it’s degeneration, but, I dunno, I’m up for it.”

While Romero’s voice modulates the diagnostic with the diaristic, Dale Benson’s alternates between the realm of fantasy and personal experience. After the initial maternal fairy tale, he speaks of the wanderlust that ultimately led to sneaking through the jungle—a dense thicket of plants filmed in the gallery—while fighting in the Vietnam war, and the trauma that his tour involved. He also describes working in the film industry in the 1980s. Much of his narrative is animated, a choice which seemed appropriate to both Tribe and Benson, whose long-standing passion project has been a children’s TV show around the theme of music.4 Nevertheless, the traumatic nature of Benson’s war experience belies its cartoonish presentation. The penultimate segment of Tribe’s film is imagined as a mini-episode of Benson’s series, where his cartoon avatars, including a bird, a seal, and a leech, sing of togetherness on the idyllic Watermill Pond in the shadow of a smiling ‘Volocano’, as shown in Figure 6. Tribe’s husband voices Benson’s solos, crooning, “I can’t speak but I can sing/I have seen some awful things/but it’s ok when we play beautiful music together…”.5 Tribe borrowed Benson’s paraphrastic episode title, “The Loste Note,” for the exhibition as a whole.

Figure 6.

Kerry Tribe, still from The Aphasia Poetry Club (2015), three-channel video with sound, 28:27 min.

The speech of the film’s third participant, Christopher Riley, differs from the other two, being largely agrammatical and at times indecipherable. Riley identifies himself as a photographer (see Riley 1996, with texts by David Chandler and Sarah Colm), and describes visiting the Killing Fields in Cambodia, which led to a celebrated series of images from found negatives of political prisoners awaiting execution. Riley’s photographic practice has since been quite literally turned on its head: “Now I turn and capture negatives upside down.” His garbled narrative encompasses both the very small (he mentions brain molecules and his rock collection) and the very large (including a cheeky enumeration of the planets in the solar system and a brief comment on the intensity, immensity, and history of space), collapsing and telescoping personal and universal themes. What Tribe dubs the “epic” nature of his distinct elocution is captured in the filmic visual register through images of the natural world—the daytime sky viewed through tree branches as well as close-ups of geological specimens, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Kerry Tribe, still from The Aphasia Poetry Club (2015), three-channel video with sound, 28:27 min.

On the one hand, the film echoes the ways that aphasia has been frequently theorized—as a structural, (post-)modern disease.6 Romero’s illness manifests when her fundamental sense of direction is compromised—she “goes crooked” and falls into a plant. Similarly, Riley responds to his linguistic deficit by reversing the angle of his photographic lens, shooting his negatives upside down. As he explains this, contact prints of Cambodian monuments appear on screen perpendicular to their actual physical orientation. Clinically, aphasia is largely identified with damage to the left hemisphere of the brain and is historically rooted in discourses of bi-polarity.7 Tellingly, the Oxford Handbook of Aphasia and Language Disorders classifies types of aphasia using plus and minus signs to signify intact and deficient language functions. Aphasia’s links to modernity are historical as well as linguistic. While references to aphasia can be traced back to the Renaissance, the research became data-substantive largely due to large numbers of wounded troops in Germany, Russia, and the United States in the wake of two world wars (Raymer and Rothi 2018, p. 308; Jakobson 1971, p. 39).

Yet there is a fundamental difference in intention between Tribe’s project and that of other artists who have worked with aphasic individuals. In Luca Buvoli’s 2007 video project Excerpts from: Velocity Zero (as well as its longer Italian-language counterpart, Velocità Zero, also from 2007), individuals with aphasia read points from FT Marinetti’s famed 2019 Futurist manifesto.8 While Buvoli describes his project as one that attempts to undermine the violence and machismo of Futurist rhetoric, as Merjian (2012, p. 104) points out, “Against the grain of its own intentions, then, the video approximates—precisely at the moment that language breaks down—Futurism’s attempted demolition of linguistic sense.” Yet Tribe did not intend to use aphasia as a metaphor for modernity or any of its corresponding incarnations. As she points out, the Aphasia Poetry Club project began simply, and perhaps naïvely, with the intention of making a work about aphasia itself.9

When writing about aphasia, the linguist Roman Jakobson couched its effects as twofold—at once a deficit and a compensation (Jakobson 1971, p. 37 “Aphasia as a Linguistic Topic”).10 Yet for Jakobson, the ‘compensation’ was typically expressed through a shift along the metonymic axis in terms of language substitution (as in substituting painting for person) that in his analysis ultimately left the aphasic individual lacking: “Aphasic regression has proved to be a mirror of the child’s acquisition of speech sounds; it shows the child’s development in reverse” (ibid., p. 40).11 The paternalism of such a statement is immense, especially given that language disorders do not in fact necessarily entail a loss of all cognitive function.12 Tribe’s work instead looks to the ways in which the brain’s right hemisphere, which loosely-speaking governs social and emotional behaviors, can be amplified and ameliorated after loss of left-brain activity. This intuitive well-being is expressed within the work by its subjects. In his typically abrupt manner, Riley periodically interjects in reference to his condition, “So what? Happy.” For Tribe, the real-life aphasia support club, which she attended as part of the research for the project, provided a radical model of togetherness and social cooperation. One of the fundamental thematics of the film is how we come to know each other and arrive at mutual understanding when language is not available, and in this aphasia offers a new paradigm for intersubjective exchange.13

Tribe’s thesis supports a social model of disability in which the subjective experiences of the aphasic individuals who participate in the project are validated and affirmed.14 Tribe was highly aware of the “ethically thorny” nature of such a project, and did make a series of choices in the editing and presentation of her materials that were intended to minimize the feelings of pity or alienation that otherwise might arise in a neurotypical audience.15 The audio is edited to minimize repetitions and interruptions in speech, and voices are not anchored to talking-head style images of individuals. This might be understood as a means to “retain the specificity of the embodied identity” without invoking the “dismissal” that certain labels or features of that identity “invites within the privileged aesthetic community”, with the latter referring to the neurotypical art world (Klages 2012, p. 105). Yet she was careful not to exploit or misrepresent her subjects, who whenever possible were interviewed in the presence of their loved ones to avoid misrepresentations of their own experiences as well as of Tribe’s project.16

The Aphasia Poetry Club was envisioned as a highly site-specific part of a larger exhibition which came to be titled The Loste Note, an epithet which is itself a paraphasic (lowest + lost) quotation from Benson’s afore-mentioned TV project. Details borrowed from previous exhibitions at the gallery, including Jonathan Horowitz’s 2014 590 Dots installation, appear in the film, reinforcing the highly self-referential nature of the project, as shown in Figure 1. The Aphasia Poetry Club was also accompanied in its original presentation by two related films and a group of sculptures and works on paper which similarly drew on the mechanics of film and cognitive testing. The gallery was conceived as two separate zones, with a bright and a dark hemisphere conjuring the physiology of the mind itself. Yet The Loste Note was as much about poetry as it was about its own institutional or discursive framing. Much of the film was shot in situ, and it was displayed on screens that maintained the dimensions of the original space. To create the sculpture that accompanied the film, Tribe worked with paraphernalia that are often invisible to the viewer, but that are no less essential to the filmic enterprise. Apple boxes and c-stands (“c” being an abbreviation for century) are materials that film crews use to capture and manipulate sound. Tribe recalls how grips often have a bodily understanding of how those objects work, unlike the artist herself, making them an active source of embarrassment for someone who works in the medium of film primarily. For Tribe, a parallel exists between the way these objects function on a film set and language itself—both are used intuitively but can cause communication problems if interrupted or lost. Using a pipe-binder, Tribe manipulated these basic building blocks of cinematic representation in such a way as to render them functionally useless (generating, in Tribe’s mind, a sculptural counterpart to aphasic language), as shown in Figure 8. The straight and curved lines of the c-stands take on the contours of written letters. Yet the evocative potential of their quasi-industrial, quasi-organic forms far outstrip the narrow phonetic or semantic boundaries of the alphabet.

Figure 8.

Kerry Tribe, sculptural installation from The Loste Note exhibition at 356 Mission, 2015.

Within the exhibition, aphasic language figures as an excess of poetry, rather than as a loss of language. Take, for example, Benson’s origin story. The ‘slip of the tongue’ that identifies his mother as a “painting” functions as a metaphor which emphasizes the fugitive nature of her existence within Benson’s memory—she is an image of herself, a pneumonic representation. Her gift of speaking “only with birds” prefigures in magical fashion Benson’s unique access to language as a product of indigenous heritage rather than as an impairment. The parallels between Tribe and her subjects, rather than their differences, were a source of inspiration for the artist. Tribe has recounted finding an old photograph of her own grandmother speaking with birds during the making of the film, and she shares Riley’s fascination with geology.17 Romero voices a similar sentiment within the film, insisting on the difficulty of access to language shared both by artist and her subjects:

Thus ‘word-finding’ is merely an anodyne clinical expression that masks the speakers true aim—self-expression. Aphasic language may be categorized as fluent or non-fluent, as loghorrea or jargon, as apraxic or agrammatical—yet ironically the farther it veers from ‘conversational’ speech, the closer it comes to pure poetry.18 After all, metaphor is, by definition, a paraphasic process: according to its early Aristotelian definition it “consists in giving the thing a name that belongs to something else” (Sontag 1990, p. 93).I’m aphasic and you’re an artist, but we have a commonality of trying to express ourself [sic]. …that’s why, I dunno, we entrust you, to use you through it, because it’s like two layers deep… even now I know what I want to say but I want to say it more eloquently and write it down or try to figure out all these ways. It’s not coming the way I want to but regardless it’s the same experience, right?

In understanding the narrative mechanics of Tribe’s work, the interdisciplinary questions neurologist Rachelle Smith Doody applies to clinical examination of aphasic patients are particularly fruitful. Doody (1991, p. 288) asks, “If speech is meant to be turned into history, what then happens with aphasic patients?” The Aphasia Poetry Club offers multiple answers, eschewing the limitations of empiricism and layering and alternating between literal and figural, metaphoric and metonymic, prosaic and symbolic speech, and visual modes. Furthermore, in Tribe’s work, the cinematic image adjusts to the dialogical asymmetry of aphasic speech that in medical discourse has forced studies of aphasic language into narrowly-conceived clinical or linguistic models (ibid., pp. 286, 296). Thus Dale Benson’s animated tale instantiates his own professional filmic aspirations by mimicking the style and format of his planned television program. Conversely, the disjointed imagery of the cosmos and massive high-resolution images of individual crystal formations mimic the clipped and garbled, yet still metaphysical and historical, patterns of Riley’s speech. In thinking through the limitations of the “joint and separate ventures” of neurology and linguistics to analyze aphasic language, Doody suggests that “Aphasia has become a ‘secondary orality,’ modelled on written speech, that can only reflect back the metaphors and allegories of representation” (ibid., p. 297). In other words, aphasia expresses the figurative processes through which communication, and by extension the act of signification, transpires. It instantiates the act of interpolation—one subject naming another, more or less obliquely—on which all human language is predicated. Thus, the intersubjective nature of aphasic language cannot truly be encapsulated or categorized either clinically or linguistically, becoming instead the instrumentalized representation of incomplete semantic systems designed to contain it. This understanding of aphasia as the embodiment of the function of representation (of language, of thought, of discourse) itself is a profound reversal of the typical function assigned to disability in the visual arts as a metaphor for moral or social disorder, and it is part of what makes Tribe’s oeuvre so distinct.

A fundamental premise of Tribe’s work is that communication is by its very nature troubled. Glitches (interruptions, repetitions, etc.) in the transmission or reception of information are not peculiar to the individuals featured in The Aphasia Poetry Club, but rather are endemic to the workings of both communication and memory. This notion, and its transference into a filmic register, is the stock in trade of Tribe’s oeuvre as a whole. Her 2010 project Critical Mass captures an argument between a male and female speaker. The two actors repeat their phrases with an exaggerated, Woody Allen-esque affectation, underscoring in dark comedic fashion how ‘dialogue’ functions as a neurotic process (both within mainstream cinema, and beyond it)—a feedback process that is constantly ‘hung-up’ and hobbled. Defending himself against the woman’s complaints, the man stutteringly insists, “I had no way of getting in touch with you.” Though on its face innocuous, the statement is rather a telling summation of the problem that Tribe’s work confronts.

The double-valence of the term episodic—at once a structuring envelope for narrative fiction, and the designation of a type of long-term memory that involves conscious recollection of prior experiences—is also at the forefront of her work. Thus in her work the literal mechanics of moving film function as mirrors of the brain’s activity (Ellegood and Fogle 2011, p. 146).19 One of Tribe’s most celebrated works, a two channel film installation titled HM (2009), is based on the story (understood to encompass both the personal as well as the wider political resonances of the term) of a man who was left unable to make new long term memories after undergoing an experimental brain operation (described as a bilateral medial temporal lobe resection) intended to cure his worsening seizures. The film runs through a pair of synchronized 16 mm projectors such that the image on the right replays the image already viewed on the left with a carefully timed interval of 20 s in between, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Kerry Tribe, H.M. (2009), double projection of a single 16 mm film, 18:30 min loop. Installation view, Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Thomas Griesel.

The interval is designed to match the length of time HM could retain information after his procedure, effectively, in other words, marking the distance between presence and pastness, when experience passes from the realm of the now and into the horizon of the then (Goulish 2013, pp. 15–22). Yet even viewed ‘singly,’ the film generates moments of looping and repetition, belying the notion that time can be understood in such a linear and direct way. Memory is a function of both repetition (in that we re-experience past in the present) and interruption (in that memory is necessarily partial, incomplete, framed by absence). In one of the early moments of the film, a cartoon-like image is projected of two tin cans on a string. It functions on a basic level as a sort of illustration of the distance between past and present that is thematized in the filmic delay—an ideogram of memory as a low-tech communication device. However, it also anticipates a recollection offered later in the film by the neuroscientist who studied HM (on whose account the film depends) of playing telephone with her neighbor as a child—a neighbor whose father, she would later learn, was responsible for HM’s doomed surgery. Recurrence is thus the psychic flaw that both disrupts and defines memory, narrative, and language.

The interstitial nature of recollection (a term that encompasses both memory and speech) is a thematic present in Tribe’s earliest explorations of time-based media. In her first publicly exhibited video, The Audition Tapes (1998), Tribe filmed actors reciting first person recollections of an unstated family conflict. The actors play members of Tribe’s own family, and their divergent accounts follow on an earlier attempt to create an ‘actual’ home movie about traumas from the family’s past.20 Thus the title card describes the project, with a mix of asperity and humor, as “another home movie.” Yet its self-consciousness as a work-of-art distinguishes it from an actual home movie. Instead, it functions in seemingly contradictory fashion as a preproduction sequel to the previous work, FAMILY/MEMORY/ROUGH/CUTS (1996), marking its status as artifice while also eliding past and present, filmic and personal registers. Even Tribe’s seemingly abstract works, such as the 2010 film installation Parnassius mnemosyne, are concerned with linguistic delay and the instability of memory. Comprised of double-perforated 16 mm film installed in the form of a mobius strip, the work visualizes the feedback loops which condition all cultural and scientific productions. The film animates a series of stills taken by a high-resolution microscope of a butterfly found in the Ural Mountains, the titular Parnassius mnemosyne, known colloquially as the “clouded Apollo.” Yet the fleeting images, which recall specs of white dust moved by wind against an indeterminate black ground, evoke the feeling not of remembering, but of forgetting. The work’s name also refers intertextually to the would-be title of a Nabokov memoir (he was, as it happens, an avid lepidopterist)—thus the unfathomable complexity of the wing of a butterfly named for the mother of the muses conjures the gaps and spaces in the delicate tissue of memory.

In its emphasis on the essential fallibility of all memory and language, Tribe’s The Loste Note exhibition overturns inherited notions of disability as lack or impairment. Perhaps more significantly, however, it redresses centuries of metaphorical thinking in the visual realm around the concept of disability. Susan Sontag confronted this way of thinking in her famous treatise, Illness as Metaphor, and its follow-up, AIDS and Its Metaphors, stating bluntly that illness is precisely not a metaphor.21 Yet the entwined histories of visual art and cultural discourse writ large are rife with examples. Since the early modern period, melancholy and madness have been seen as the hallmark of the creative personality, thanks to a theory of the humors derived from the ancient Greeks. The trope of the dispirited intellectual persisted such that in the 19th century the association became even more pronounced (Dixon 2013, pp. 2, 11–19, 117–21, 183–92). Sontag (1990, p. 30 “AIDS and Its Metaphors”) enumerates how the “tubercular look” came to symbolize “an appealing vulnerability, a superior sensitivity” befitting a modern romantic hero. Sontag (ibid., p. 36) points to the romanticizing of madness prevalent in contemporary culture, which she deems “the current vehicle of our secular myth of self-transcendence.” The romantic tradition lives on, filtered through the lenses of psychoanalysis and Marxism, in Deleuze and Gauttari’s notion of schizophrenia as meaningful social critique (Kuppers 2007, pp. 17–18).

The Aphasia Poetry Club can be understood as revisiting the relationship between art and medicine at the root of both disciplines. Physical disabilities in particular have been invoked by countless artists to express inward, immaterial states in exterior, plastic form. Blindness is a particularly well-worn hobby-horse in the visual arts: take for example Bruegel’s famous images of beggars, cripples, and blindmen, such as The Parable of the Blind Leading the Blind (1568), where sightedness (or lack-there-of) stands in for spiritual enlightenment (McDonald 2018, p. 41).22 Throughout the history of art, physical and mental disability have been presented either as allegories of the senses or invested with assumptions about leprosy, poverty, and social stigma.23 Illness and disability have, almost inescapably, been caught up in attempts to illustrate a larger moral dialectic of good and bad (Sontag 1990, pp. 48–85).

Tribe’s work embodies an aesthetic shift in attitude towards disability taking place in the wider field of contemporary art, treating it as a métier through which to make art rather than as a metaphor for genius or enlightenment, debility or difference. In part, this change can be attributed to the increasing visibility that artists with lived experience of disability are receiving in mainstream arts institutions (Persimmon Blackridge, Park MacArthur, and Christine Sun Kim being prominent but by no means exclusive or necessarily representative examples). As those with disabilities become less marginalized, actual impairments become less available as objects of speculation for those who have no experience of them. This shift is also reflective of a new-found theoretical and discursive emphasis on process that has impacted ideas about privilege and power. Since the early modern period, the western concept of authority—be it political, religious, or medical—has lost its status as predetermined, totalizing, or unassailable and has been rendered increasingly assigned, partial, and flawed. Divinity fades to utility. The in situ nature of the Aphasia Poetry Club, along with the self-reflexivity regarding the nature of film as a normative enterprise borne out by the exhibition installation as a whole, places the project within the broader evolution of institutional critique. That critique is itself predicated on the Foucauldian notion that power is not an eternal truth but a temporal exercise. Similarly, disability no longer functions as a totalizing metaphor within the art world, not only because postmodern theory has exposed such single-minded ideas as privileged fictions, but also because disability experience belies ableist fictions regarding the perfectibility of human language and representation. Yet cognitive difference can offer a rich ground for figurative play, both linguistic and visual. The experiences of negotiation and translation inherent to human neurodiversity structure The Aphasia Poetry Club and inform the poetics of disability on which so many of Tribe’s films are based.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

All images courtesy of the artist and 1301PE, Los Angeles.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Chandler, Eliza, Nadine Changfoot, Carla Rice, Andrea Lamarre, and Roxanne Mykitiuk. 2018. Cultivating Disability Arts in Ontario. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies 40: 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasio, Antonio R. 1998. Signs of Aphasia. In Acquired Aphasia, 3rd ed. Edited by Martha Taylor Sarno. New York: Academic Press, pp. 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, Laurinda. 2013. The Dark Side of Genius: The Melancholic Personal in Art, ca. 1500–1700. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Doody, Rachelle Smith. 1991. Aphasia as Postmodern (Anthropological) Discourse. Journal of Anthropological Research 47: 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellegood, Anne, and Douglas Fogle. 2011. All of This and Nothing. Los Angeles: Hammer Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Freud, Sigmund. 1953. On Aphasia: A Critical Study. New York: International Universities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goulish, Matthew. 2013. ‘A Clear Day and No Memories’: Neurology, Philosophy, and Analogy in Kerry Tribe’s HM. Art Journal 72: 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, Bree, and Donna McDonald. 2019. The Routledge Handbook of Disability Arts, Culture, and Media. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman, Kenneth M. 2018. Aphasia Syndromes and Information Processing Models: A Historical Perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of Aphasia and Language Disorders. Edited by Raymer Anastasia M. and Leslie J. Gonzalez Rothi. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobson, Roman. 1971. Studies on Child Language and Aphasia. Paris: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Karp, Diane. 1985. Ars Medica: Art, Medicine, and the Human Condition. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Klages, Mary. 2012. An Other Order of Discourse. English Language Notes 50: 103–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppers, Petra. 2007. The Scar of Visibility: Medical Performance and Contemporary Art. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, Donna. 2018. Visual narratives: contemplating the storied images of disability and disablement. In The Routledge Handbook of Disability Arts, Culture, and Media. Edited by Bree Hadley and Donna McDonald. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Merjian, Ara H. 2012. ‘Those ars all bellical’: Luca Buvoli’s Velocity Zero (2007–2009) and a post/modernist poetics of aphasia. Word & Image: A Journal of Verbal/Visual Enquiry 28: 101–16. [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau, Stephen E., Leslie J. Gonzalez Rothi, and Bruce Crosson, eds. 2000. Aphasia and Language: Theory to Practice. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pafunda, Danielle. 2012. The Subject in Pain: A Poetics. English Language Notes 50: 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarno, Martha Taylor, ed. 1998. Acquired Aphasia, 3rd ed. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Raymer, Anastasia M., and Leslie J. Gonzalez Rothi, eds. 2018. Aphasia Syndromes: Introduction and Value in Clinical Practice. In The Oxford Handbook of Aphasia and Language Disorders. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, Christopher. 1996. The Killing Fields. Santa Fe: Twin Palms. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, Susan. 1990. Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Alastair. 2018. On Not Seeing Tahiti: Gauguin’s Noa and the Rhetoric of Blindness. In Gauguin’s Challenge: New Perspectives after Postmodernism. Edited by Norma Broude. New York: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | My thanks to Kerry Tribe for her lively collaboration and ready responses to my questions. Aphasia syndromes vary significantly in both causes and effects, and aphasia cannot be understood in a monolithic way. For a detailed breakdown of the most common designations and their related pathologies, see (Sarno 1998, pp. 34–40). |

| 2 | The substitution of painting for person is a form of semantic paraphasia, where the thing being substituted bears a meaningful relationship (say, chair for table, or in this case, portrait for person) to the intended object. When a single phoneme is substituted or added, as in Kindiana, it is known as a phonemic or literal paraphasia. The speaker’s agrammatical omission of the indefinite article before Comanche is also a common aspect of aphasic speech in which functor words, such as articles, prepositions, and conjunctions, are dropped (ibid., p. 28). See also (Nadeau et al. 2000, p. 51). |

| 3 | Neurologist Rachelle Doody uses such name-testing to criticize the level of verbal organization expected from aphasics, particularly given the illogical and disorganized nature of many human speech acts (Doody 1991, pp. 292–93). |

| 4 | Kerry Tribe in conversation with the author, 20 September 2019. |

| 5 | Ibid. |

| 6 | On the coincidence of early aphasia research and the emergence of the European modernist avant-garde, see (Merjian 2012, pp. 107–3). As Merjian points out, as modernism became increasingly understood as symptomatic of aphasic degeneration, “Absence and loss (of meaning, of sense) served no longer as the dialectical, structuring opposite of modernist aesthetics, but rather its hollow core” (p. 108). For a nuanced critique of aphasia studies’ indebtedness to structural linguistics, see (Doody 1991, pp. 288–93). |

| 7 | As Doody (1991, p. 286) points out, “centuries worth of information has gone into neurological representations of the aphasic syndromes and their underlying localizations. See also (Raymer and Rothi 2018, pp. 3–7). In his discussion of Broca’s aphasia, one of the earliest-described aphasia syndromes, Kenneth Heilman (2018, p. 14) notes: “The reason the left frontal lobe lesion induces the syntactic deficit associated with Broca’s aphasia is not fully known; however, syntax is based on the ordering of symbols, characterized by categories such as agent and patient. Individuals with frontal lobe dysfunction are often impaired at ordering and sequencing. In addition, whereas the left hemisphere appears to be dominant for mediating categorical relationships, the right hemisphere mediates continuous relationships. Thus, because syntax requires the ordering of categorical relationships, damage to the left frontal lobe would impair these processes and lead to the agrammatism associated with Broca’s aphasia.” As Heilman points out, nineteenth-century studies of aphasia were predicated on the notion of brain modularity-specialization previously introduced by the inventor of phrenology, German physician and anatomist Franz Joseph Gall (11–12). Interestingly, two of the earliest researchers on aphasia, Paul Broca and Carl Wernicke, were both able to predict forms of aphasia that they themselves had not actually observed based on correctly postulating relationships between brain function and geography. |

| 8 | Excerpts from: Velocity Zero. 2007. Single-channel DVD, 5 min, color, sound. Edition of 5 (plus two artist’s proofs). |

| 9 | Kerry Tribe in conversation with the author, 20 September 2019. For her research into a planned project on aphasia funded by a 2012 Creative Capital grant, Tribe began attending stroke support groups in Southern California, including one established at Cedars Sinai Hospital called the Aphasia Support Group (ASG), which had an active Facebook presence. Tribe chose ten people to interview from within this community of individuals, all of whom had creative backgrounds. She subsequently began attending another group hosted by the Echo Park library called the Aphasia Book Club, an outgrowth of the ASG that launched during the making of the film. |

| 10 | Jakobson (1971, p. 41) referred to aphasia in terms of two opposite tropes, metaphor and metonymy, which he understood as presenting “the most condensed expression of the two basic modes of relation: the internal relation of similarity (and contrast) underlies the metaphor; the external relation of contiguity (and remoteness) determines the metonymy”. He developed categories of aphasic disorders based on these poles which can be partially mapped onto current clinical nomenclature, such that Broca’s or motor-efferent aphasia was in Jakobson’s terminology a form of encoding disorder affecting the metonymic functions of combination and contiguity; whereas Wernicke’s or sensory-efferent aphasia was understood as a type of decoding disorder affecting the word-selection functions governed by metaphoric substitution and selection. See (ibid., pp. 44–48 “Aphasia as a Linguistic Topic”, pp. 49–73 “Two Aspects of Language and Two Types of Aphasic Disturbances”, p. 80 “Toward a Linguistic Typology of Aphasic Impairments”, pp. 97–98 “Linguistic Types of Aphasia”). |

| 11 | Elsewhere Jakobson, ever attempting to subordinate language to the two poles of metaphor and metonymy, uses his discussion of aphasia as a pretext for a literary aside, pointing out, “The principle of similarity underlies poetry; the metrical parallelism of lines, or the phonetic equivalence of rhyming words prompts the question of semantic similarity and contrast; there exist, for instance, grammatical and anti-grammatical but never agrammatical rhymes.” In contrast, metonymy is structurally prosaic—“prose… is forwarded essentially by contiguity.” Jakobson even goes so far as to differentiate literary modes, linking romanticism with metaphor and realism with metonymy (Jakobson 1971, p. 73 “Two Aspects of Language and Two Types of Aphasic Disturbances”). Tribe’s work bridges these poles, however, as is discussed in greater detail below. |

| 12 | Written and spoken language and auditory comprehension can each function independently, so certain aphasic syndromes will impact aspects of one area while leaving other abilities more-or-less intact. Furthermore, language deficit does not imply mental deficit or defect (Damasio 1998, pp. 26–29). |

| 13 | Kerry Tribe in conversation with the author, 20 September 2019. |

| 14 | It is important, given the working distinctions drawn in the field of disability studies, to acknowledge Tribe’s project as a form of “integrated arts,” wherein a non-disabled artist is working with people with cognitive disabilities without “amplifying boundaries, binaries, and power relations” between disabled and non-disabled individuals involved, while at the same time distinguishing it from the disability-led practice advocated by those in the field who want to foreground artists and makers with lived experience of disability. See (Hadley and McDonald 2019, p. 6; Chandler et al. 2018, pp. 251–3). |

| 15 | Leading disability scholar and activist Petra Kuppers has framed the practical ethics of disability arts as a question of how to create art in the presence of pain and alienation without causing it. Kuppers also investigates “disability culture and art-framed performance work that refused to disclose any notion of the fundamental essence of disability while setting up a seductive curiosity toward different forms of embodiment,” which might also be taken as a formulation of Tribe’s project (Kuppers 2007, p. 3). |

| 16 | Kerry Tribe in conversation with the author, 20 September 2019. |

| 17 | Kerry Tribe in conversation with the author, 20 September 2019. |

| 18 | Or, as Doody (1991, p. 297) points out with no small irony, to Derrida’s dream of the free play of the signifier, released from the strictures of signification. |

| 19 | Technically I am citing the artist entry by Corrina Peipon. The book is distributed by Prestel, NYC. |

| 20 | Kerry Tribe in conversation with the author, 20 September 2019. |

| 21 | In response to Sontag’s anti-magical thinking, Danielle Pafunda asks whether there might indeed be some utility to metaphors of the body and its condition: “But what about metaphors that help us communicate our otherwise inarticulable experiences of illness and disability? To critique the power dynamics between the kingdoms of the well and the ill? To deconstruct the border between ill and well, and refuse the idea that either is a unified land? Perhaps we find that illness is a metaphor, insofar as every human thing is” (Pafunda 2012, p. 97). |

| 22 | To this we might add as a more modern example Gauguin’s written accounts of Tahiti and his invocation of blindness to express his outsider status. See (Wright 2018, p. 130). |

| 23 | For a survey of relevant examples, see (Karp 1985). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).