Abstract

This paper investigates a case of historical co-emergence between a modern system of dance notation and the rise of geometric abstraction in the applied arts during the first decades of the 20th century. It does so by bringing together the artistic careers of the choreographer Rudolf von Laban and the visual artist Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Comparing their pedagogical agendas and visual aesthetics, this paper argues that the resemblances between Laban’s Kinetography and Taeuber-Arp’s early geometric compositions cannot be a matter of pure coincidence. The paper therefore presents and supports the hypothesis of a co-constitutive relationship between visual abstraction and the dancing body in the European avant-garde.

1. Introduction

Perhaps it is sheer chance that the geometrical shapes of Laban’s visual dance scores matched Taeuber’s previous compositions uncannily.—Jill Fell (1999, p. 274)

This essay lingers on the apparent contingency of what appears to be a striking visual resemblance: that between a modern system of dance notation and early modernist abstract art. To do so, it brings together the lives and works of the choreographer and dance theoretician Rudolf von Laban with those of the artist and pedagogue Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Today, Laban’s name is famous not only for his contributions to German expressionist dance, but also for his invention of Kinetography, a system for the recording of dance using abstract symbols, which he developed in the first decades of the 20th century. Known today as Labanotation, it continues to be amongst the prevalent systems of movement notation and analysis.1 During the early stages of its development, Laban frequented similar artistic circles as Sophie Taeuber-Arp, who at the time was developing her abstract visual language in textile design and other media of the applied arts. Jill Fell is not alone in having drawn attention to a potential artistic conversation between these two artists,2 but up to now no thorough research into the nature of this connection between Rudolf von Laban and Sophie Taeuber-Arp has been undertaken.

The present study is an attempt to move from speculation to an evidence-based approach that can account for the undeniable visual parallels between these two artists; parallels that are all the more striking once it becomes clear that they cannot simply be reduced to the question of direct artistic influence. This will be shown in three parts. A first section sketches an outline of Laban and Taeuber-Arp’s educational backgrounds and early career paths in Munich, Ascona and Zurich during the first two decades of the 20th century. It further discusses the fruitful encounters between the Laban dance school and Dada circles in Zurich, for which Taeuber-Arp is considered one of the most significant connecting links. The second section contextualizes Laban’s development of Kinetography and offers a brief introduction to its main structural components. This prepares the reader to detect its resemblances with a selection of Taeuber-Arp’s early work in the applied arts. A third section finally returns to the question of influence, discussing Laban’s educational agenda in conjunction with Taeuber-Arp’s pedagogical writings to demonstrate how the resonances between these two artists run deeper than a mere visual affinity. At stake is not only a more precise account of the presence of movement in nonfigurative compositions, but also a more nuanced understanding of the relationships between abstraction and the dancing body in the European avant-garde.

2. A Series of Encounters: Munich, Ascona, Zurich

The lives of Rudolf von Laban and Sophie Taeuber-Arp intersect in three significant geographical locations. Born 20 years apart and into considerably different socio-economic circumstances,3 Laban and Taeuber-Arp both spent formative years receiving their artistic education in Munich, at the time a “crucible of European cultural experiment” (McCaw 2011, p. 5). Laban came to Munich in 1889 and enrolled in the Kunstakademie—he initially wanted to become a painter—while also taking classes at the renowned Debschitz School.4 The latter is the school Sophie Taeuber-Arp attended when she came to the city in 1910. By then, Laban had completed his education, but remained in Munich and turned his creative interests towards dance; he was developing his harmonic movement theory, opened his first dance school, staged performances and hosted several carnivalesque dance parties. While there is evidence that Taeuber-Arp attended similar events during her Munich years, it remains a speculation to imagine her at one of Laban’s early performances or festive gatherings (Krupp 2017, pp. 156–57).

Laban left Munich for Ascona in May 1913, where he founded an artistic summer program in the experimental life reform colony on Monte Verità. He moved near Zurich in 1915 and opened a School for Art in the city center. Like the Ascona summer course, the Zurich school was organized around a syllabus entitled Tanz Ton Wort Form, which, offering lessons in movement art, acoustic art, verbal art and formal art, became a key center for expressionist dance at the time.

By this time, Sophie Taeuber-Arp too had been living in Zurich for several months, working as a teacher of applied arts at the Kunstgewerbeschule while continuing to expand her multifaceted artistic practice. A new discipline that had recently sparked her interest was dance. After some initial misgivings, she had taken up gymnastics lessons in Munich, where she learned about Laban’s dance school through the dance theoretician Hans Brandenburg; she enrolled in classes at the newly-founded Laban school in Zurich in the summer of 1915 (Krupp 2017, p. 157).

Since Laban was not actively involved in the teaching activities at his school until 1917, it is not clear how much direct contact Taeuber-Arp would have had with the dance master himself (Dörr 2008, p. 57). It is indeed more likely that she received lessons from Mary Wigman, Käthe Wulff, or from other members of the teaching staff. Taeuber-Arp attended the summer course that continued to be held at Monte Verità in 1915 and returned there in 1917 (Fell 1999, p. 270; Krupp 2017, p. 154). She further appeared in at least one of the Laban school’s Tanzabende (dance evenings) in 1916, ostensibly performing alongside Mary Wigman and Claire Therval in solo, duo or trio shows and choreographing her own work (Dörr 2004, p. 95).

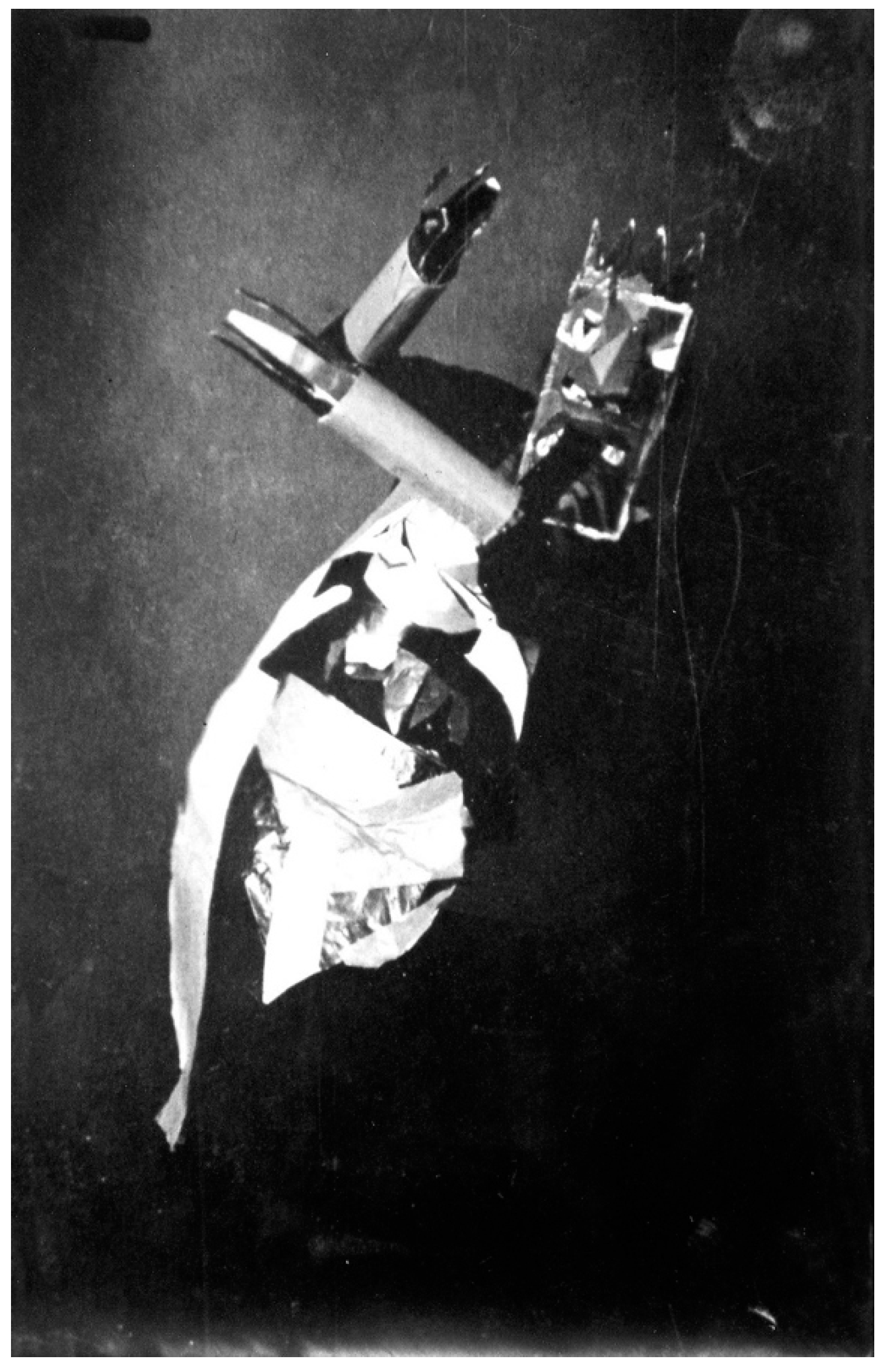

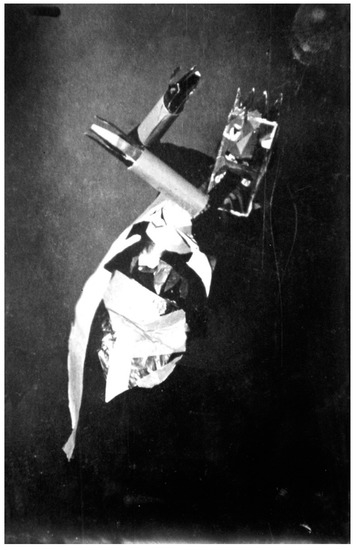

The beginning of the year 1916 also marked the opening of the Cabaret Voltaire, a performance venue for the newly-founded Dadaist group.5 The mention of Sophie Taeuber-Arp as one of the first “Laban students” (Dörr 2008, p. 65) to participate in these soirées attests to her affiliation with the dance school by the time she appeared in Dada contexts. A somewhat dubiously credited photograph (see Figure 1), some notes by Tristan Tzara and Hugo Ball and a commemorative poem by her husband Hans Arp are the sole testimonies that remain of Taeuber-Arp’s Dada performances. Given the nature of this documentation, the present essay refrains from teasing out yet another speculative reconstruction from such semi-reliable traces.6

Figure 1.

Photograph of Sophie Taeuber-Arp dancing at the Cabaret Voltaire/Galerie Dada, ca. 1916/1917. Unknown photographer. Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth, used by permission.

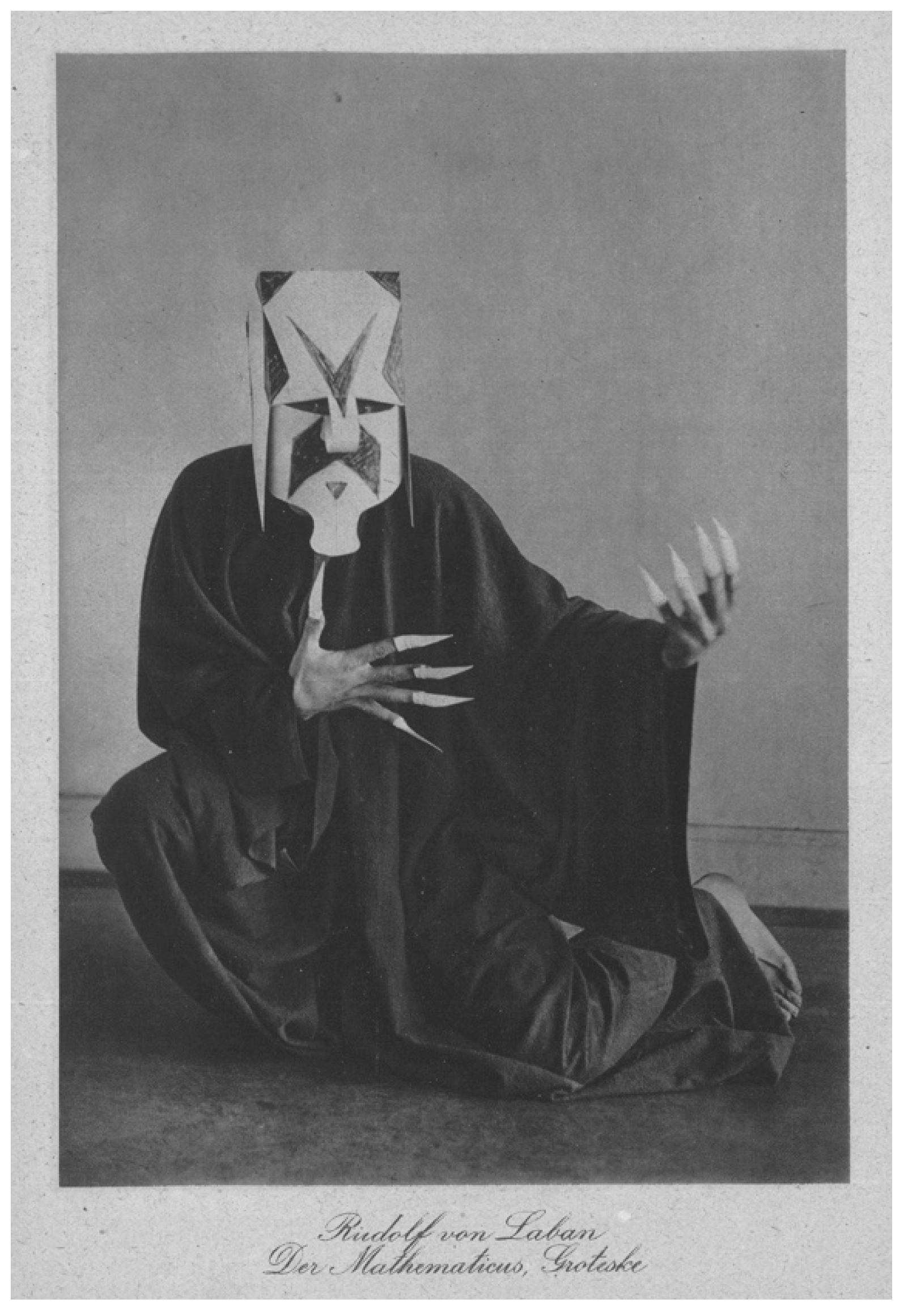

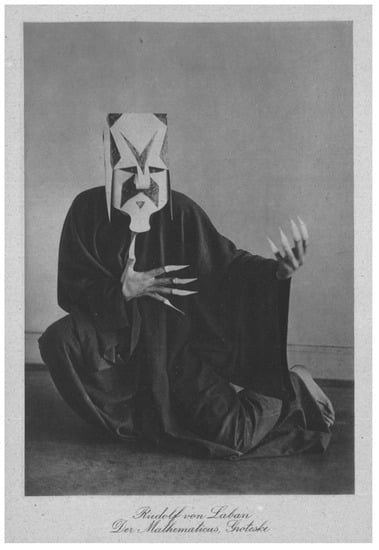

Despite our lack of knowledge about the precise aesthetics of Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s dance activities, there can be no doubt that she moved back and forth between the Laban dance school and the activities of the Dada circle between 1916 and 1919. The aesthetic, ideological and romantic exchanges between these artistic groups have recently been the focus of growing scholarly research.7 Their shared interest in the cultic, ritualistic and the primitive indeed sanctions an emphasis on the strong parallels between the groups’ performance aesthetics. Both, for instance, used gong sounds and word particles to generate movement from inside the dancer rather than imposing dance steps from without, and both included masks as performance props within their artistic repertoire (De Weerdt and Schwab 2017, p. 18). Some scholars argue that Rudolf von Laban could have been influenced by the costume design in the photograph associated with Sophie Taeuber-Arp (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).8 Others are less certain about this potential connection.9

Figure 2.

Photograph of Rudolf von Laban as Mathematicus, ca. 1915–1918. In Rudolf von Laban, Die Welt des Tänzers: Fünf Gedankenreigen. Stuttgart: Verlag von Walter Seifert, 1920.

Costume, moreover, is one of the most immediately apparent points of divergence between the Dadaist and Laban performance styles. Dada’s material aesthetic of montage turns costume into an autonomous performance element which at times purposefully inhibits movement. Laban’s costuming, in turn, is entirely subordinate to the free expression of the body’s full potential for locomotion; garments were wide and flowing, if garments were worn at all.10

A point which the artistic projects of Dadaism and Labanist expressionism share is a recourse to natural movement. As Lucia Ruprecht argues, both circles turned to rhythm and vibrations as a means of connecting with a vitalist energy beyond the purview of the corrupted intellect (Ruprecht 2017, p. 125). Despite this shared privileging of bodily intuition and spontaneity, Laban conceives of such vibrations as a means of achieving harmony and synchrony between groups of moving bodies, whereas the Dadaists foregrounded “the asynchronic, the disharmonic, the cacophonous and the arrhythmic” in their movement style (Ruprecht 2017, p. 129; translation by the author). Indeed, if Hal Foster describes the shaking Dadaist as miming “the bliss of the epileptic” (Foster 2003, p. 168), the Laban dancer is much better characterized as miming the bliss of man reunited with nature.11

Despite their diverging aesthetics, the Dada circle and the Laban school thus both emerged out of a comparable rejection of bourgeois moral and artistic standards as an acute reaction to the devastations of World War I.12 Evelyn Dörr pits the Dadaists’ investment in shock-inducing spectacle, fragmentation, anarchism and nihilism against Laban’s harmonious group choreographies geared not towards “an overthrow of order but instead at a cultural renewal of society” (see Dörr 2008, p. 66). Scholarship on Dada, however, has questioned the supposed nihilism commonly associated with the movement. T.J. Demos, for instance, detects in Dada’s collaborative performances a utopian drive towards a renewal of mankind—a wish for renewal that is perhaps not unlike Laban’s project of a Lebensreform. “Dada evinced a commitment to publicness […] that implies a desire for social relations beyond the finality of their destruction. If Dada rejected conventional modes of community, it also imagined experimental ways of collectivization,” Demos writes (Demos 2005, p. 11).13

The perhaps most compelling point of divergence between the Dadaists and Rudolf von Laban, however, is their respective relation to language. On the side of the Dadaists, the sound poems of Hugo Ball and Tristan Tzara “deracinated” language in deep suspicion of its complicity with a belligerent bourgeois social order (Demos 2005, pp. 7, 17). Laban’s goal, on the other hand, was not the demolition of an existing linguistic order, but precisely the creation of a new sign system based on a holistic philosophical-ideological theory: and this aspiration will materialize in his development of Kinetography. And while Laban and Mary Wigman formed part of the audience at the Cabaret Voltaire and Galerie Dada in 1916 and 1917, as much as we know, they never actively participated in any Dada events themselves (Dörr 2008, pp. 65–66).

The task at hand, then, is neither to collapse the Labanist and the Dadaist styles into a single shared aesthetic, nor to treat them as two mutually exclusive phenomena. Rather, this paper sees them as two parallel movements in productive friction with each other. And Sophie Taeuber-Arp, neither fully a Dadaist nor a Labanist herself,14 must be understood to inhabit a unique position in between the two.15

3. The Writing of Dance

By the time Laban left Zurich for Germany in 1919, he claims to have given over 200 performances.16 It is less clear to what extent his dance notation system was developed by then. But despite the fact that Laban did not publicize a fully formulated version of his Kinetography before 1928, several sources indicate that his interest in the problem of capturing dance on the page dates back much earlier than the late 1920s.17 Evelyn Dörr for instance mentions that Laban studied older systems of movement notation as early as 1904 when he was a student in Paris, and again in 1912 in Munich (Dörr 2008, p. 43). His student Mary Wigman recounts performing a series of swinging movements in front an indefatigable Laban during the summer of 1914 at Monte Verità: “Every movement had to be done over and over again until it was controlled and could be analyzed, transposed and transformed into an adequate symbol” (Wigman 1983, p. 303). The transposition of the body’s motions into a standardized and repeatable semiotic sign evidently preoccupied Laban from the early stages of his career. In a letter to his friend Hans Brandenburg from February 1919, Laban writes that he had finally invented a sign system that made “movement in all its interrelationships ‘much more visualizable’”.18 It is thus not justified to treat the formalization of Kinetography as an interest exclusive to Laban’s post-Zurich career.

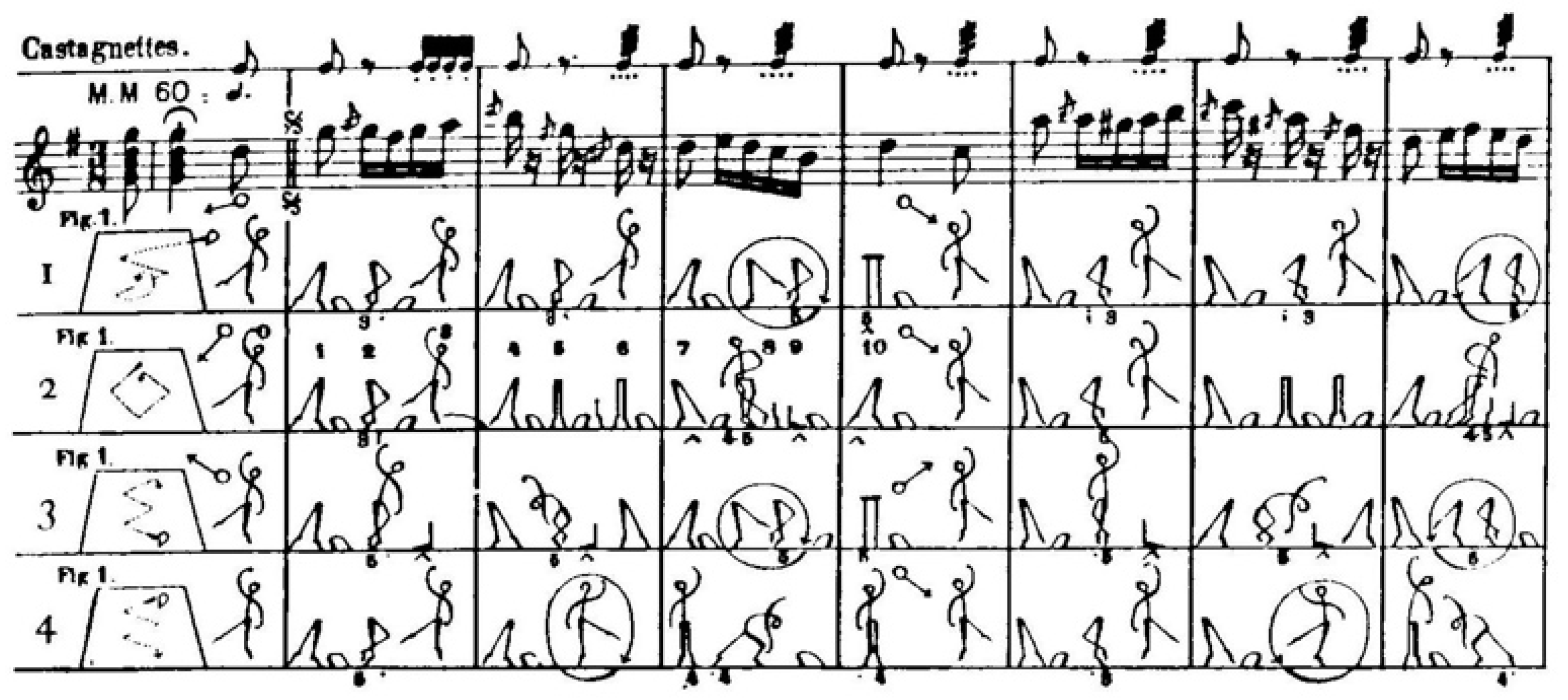

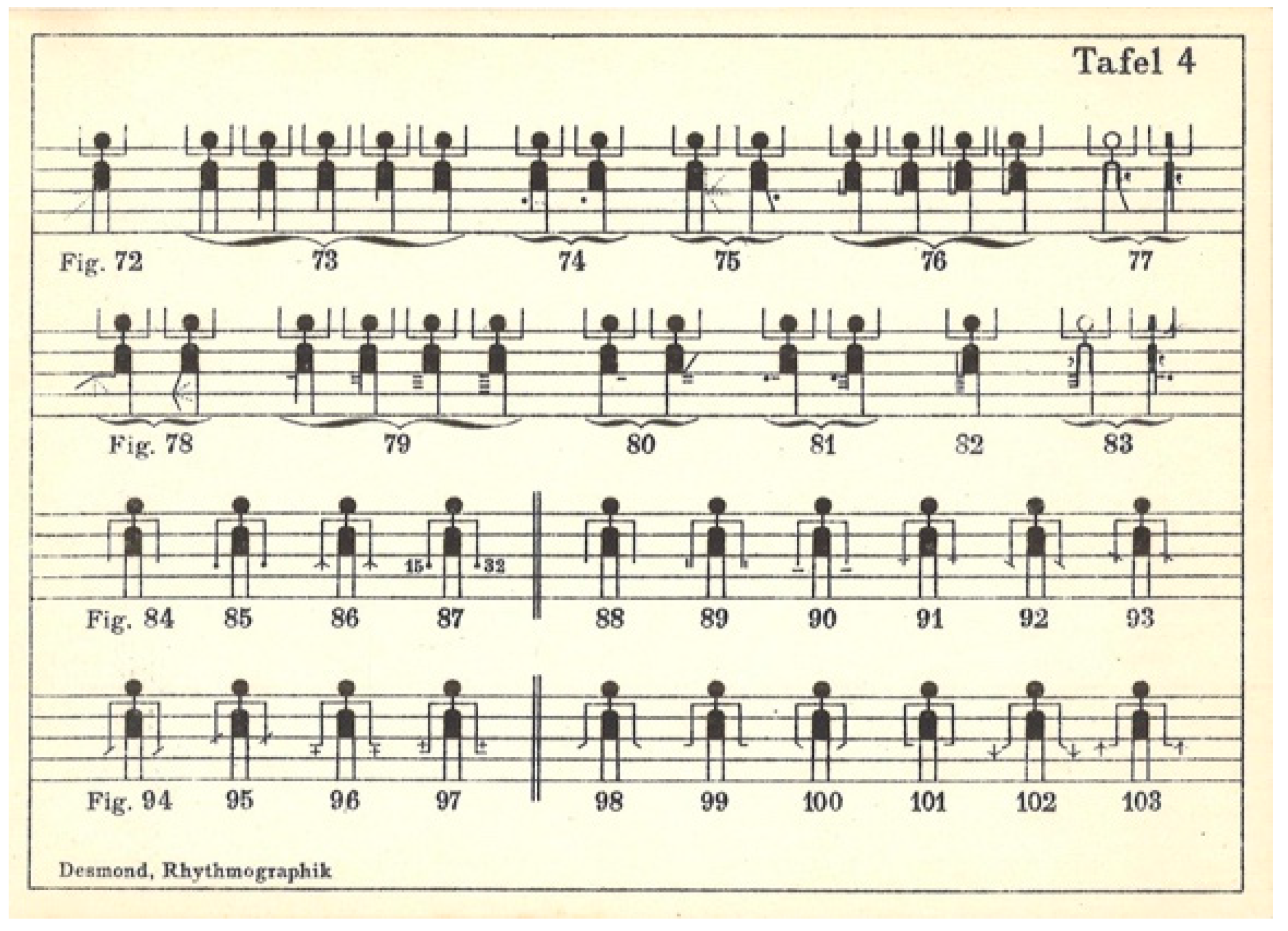

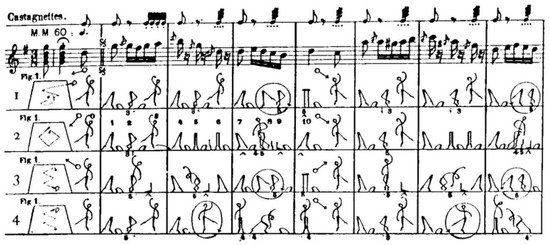

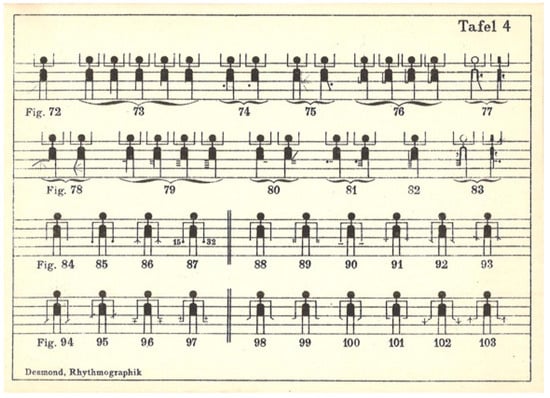

Rudolf von Laban was of course not the first to take up the challenge of devising a script that records the movements of bodies in time and space. Yet, as Roderyk Lange observes, “the area of dance is a latecomer to literacy” (Lange 2011, p. 155). The origins of this process are often traced to the use of letter codes as abbreviations for dance steps in the Renaissance, while one of the most highly developed attempts to systematically record dance dates to the reign of Louis XIV and is known as Feuillet notation.19 Widespread throughout Europe for nearly a century, this notation is organized around the floor pattern traced by dancers’ steps, using elaborate step signs to indicate the kinetic quality of each movement. Later notation systems since the 19th century employ stick figures or other schematized representations of the body, placed on a single line or on an adapted music stave (see Figure 3 and Figure 4). These dance notations, however, indicate primarily a series of positions to be occupied by the dancing body at certain moments in time. The ancillary indications linking the positions give only a rudimentary idea of the detail and continuity of movement between them (see Hutchinson Guest 1989, p. 64).

Figure 3.

Excerpt from the Cachucha in Friedrich Albert Zorn, Grammar of the Art of Dancing. Boston: Heintzemann Press, 1905.

Figure 4.

Excerpt from Olga Desmond, Rhythmographik (Tanznotenschrift) als Grundlage zum Selbststudium des Tanzes. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1919.

These early codifications of movement—whether letter codes, floor patterns or stick figure models—took for granted a considerable amount of prior knowledge about the recorded dance from the part of their readers. Not only did this limit the scope of what they could record, it also meant that such notation systems were “very much a product of, and suited to, the dance of their own period” (ibid., p. 21).

Kinetography did not come with such limitations. Its notation system is made up of a relatively small set of basic elements—similar to linguistic morphemes—that can be combined ad infinitum to record an endless variety of bodily movements. In a re-publication of his notation system from 1956, Laban recapitulates: “Just as poetry, in every language, can be written down phonetically, so every stylised movement can be written down ‘motorically’. The motor movement notation is the equivalent of the alphabet” (Laban 1956, p. 15). Kinetography deserves the name Bewegungsschrift (movement writing), as it truly functions like a fully-fledged language.20 A brief overview of its mechanics will prove this point.

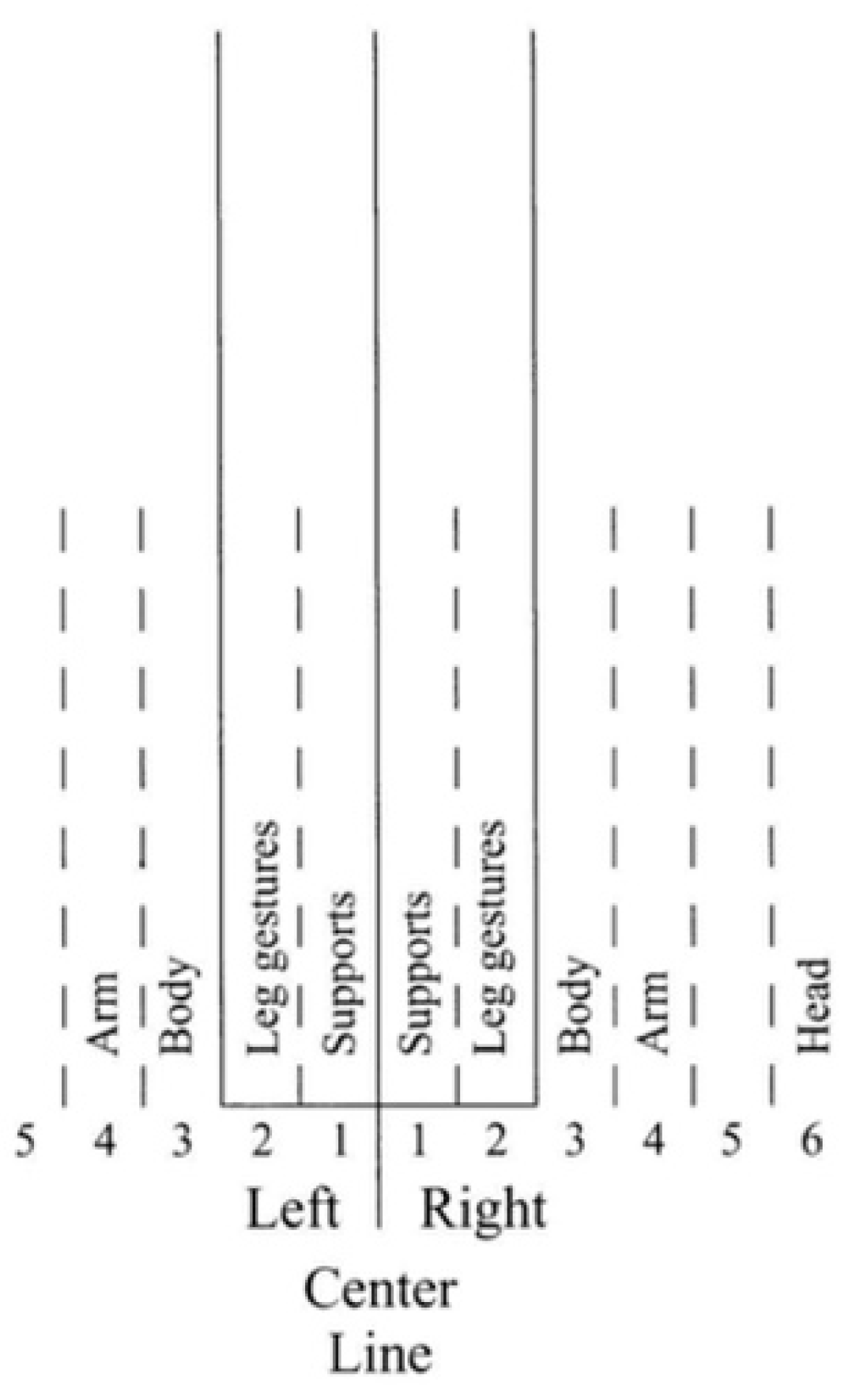

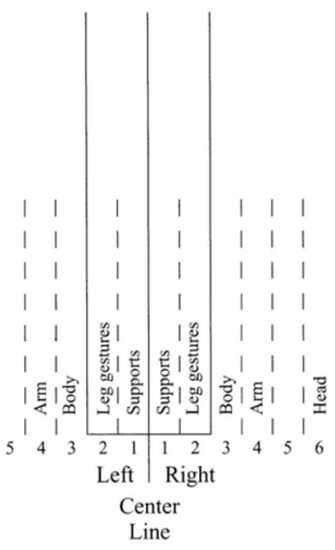

The most elementary component of Labanotation is a vertical staff which is read from the bottom to the top of the page (see Figure 5). A central line divides the right side of the body from the left side. Different columns in this staff stand for different areas of the body: moving outward from the center line, these columns indicate the body’s weight supports (column 1), the legs (column 2), the upper body (column 3), the arms (column 4) and finally, on the outer right side of the staff, the head (column 6).

Figure 5.

Standard staff of Kinetography. Created by Ann Hutchinson Guest, used with permission from the author.

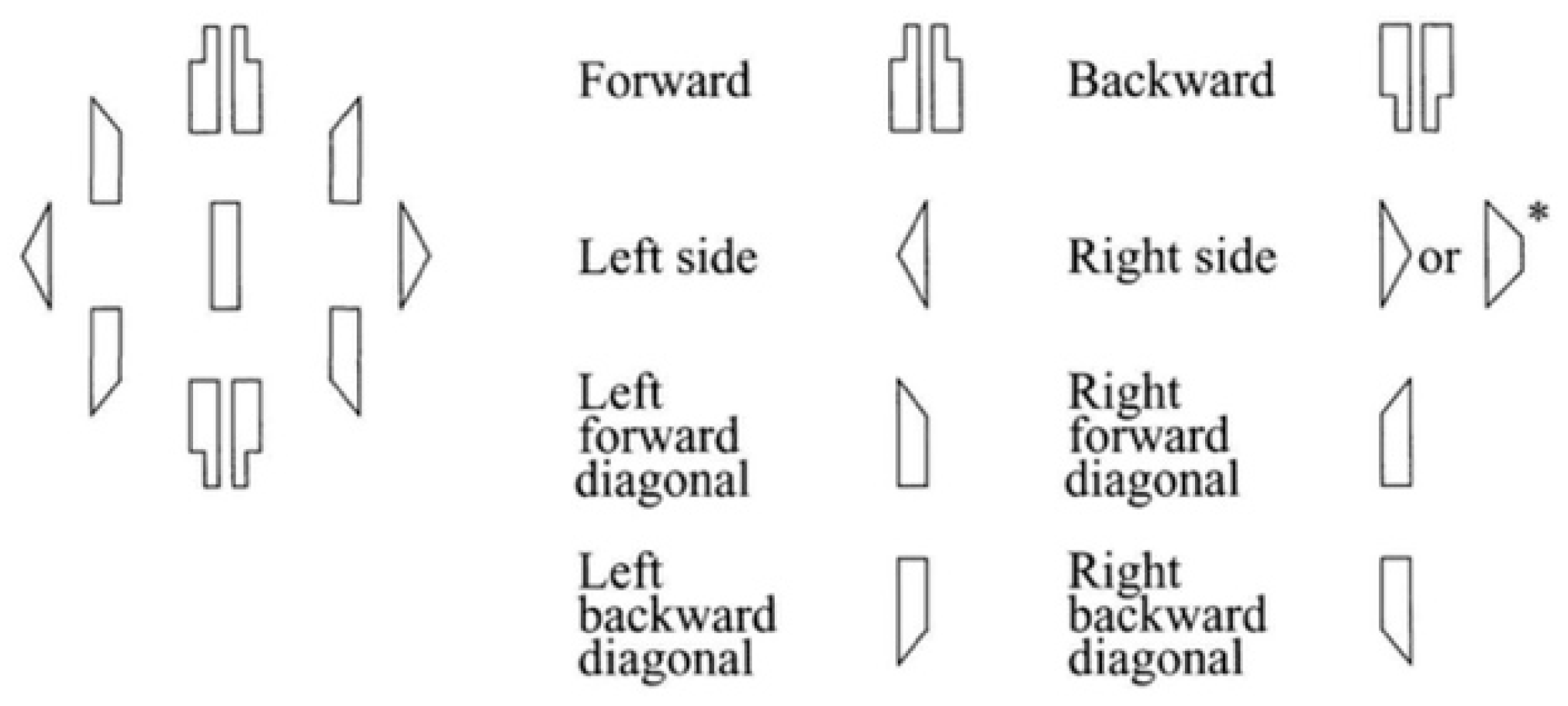

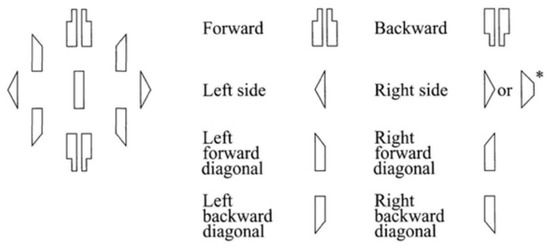

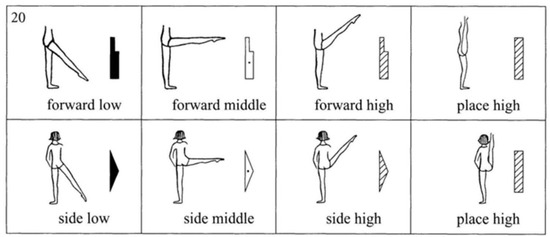

Various symbols can be inserted into these columns to indicate that movement of any of these body parts is required. The shape of the symbols determines the direction of their movement (Figure 6). A ‘chimney’ shape stands for forward-movement, its reverse indicates backward-movement. A triangle pointing to the right means movement in or towards the right side of the body, and vice versa. A rectangle with one slanted side signifies diagonal displacement, either forward or backward in space. A regular rectangle stands for movement in place.

Figure 6.

The eight main directions of Kinetography. Created by Ann Hutchinson Guest, used with permission from the author.

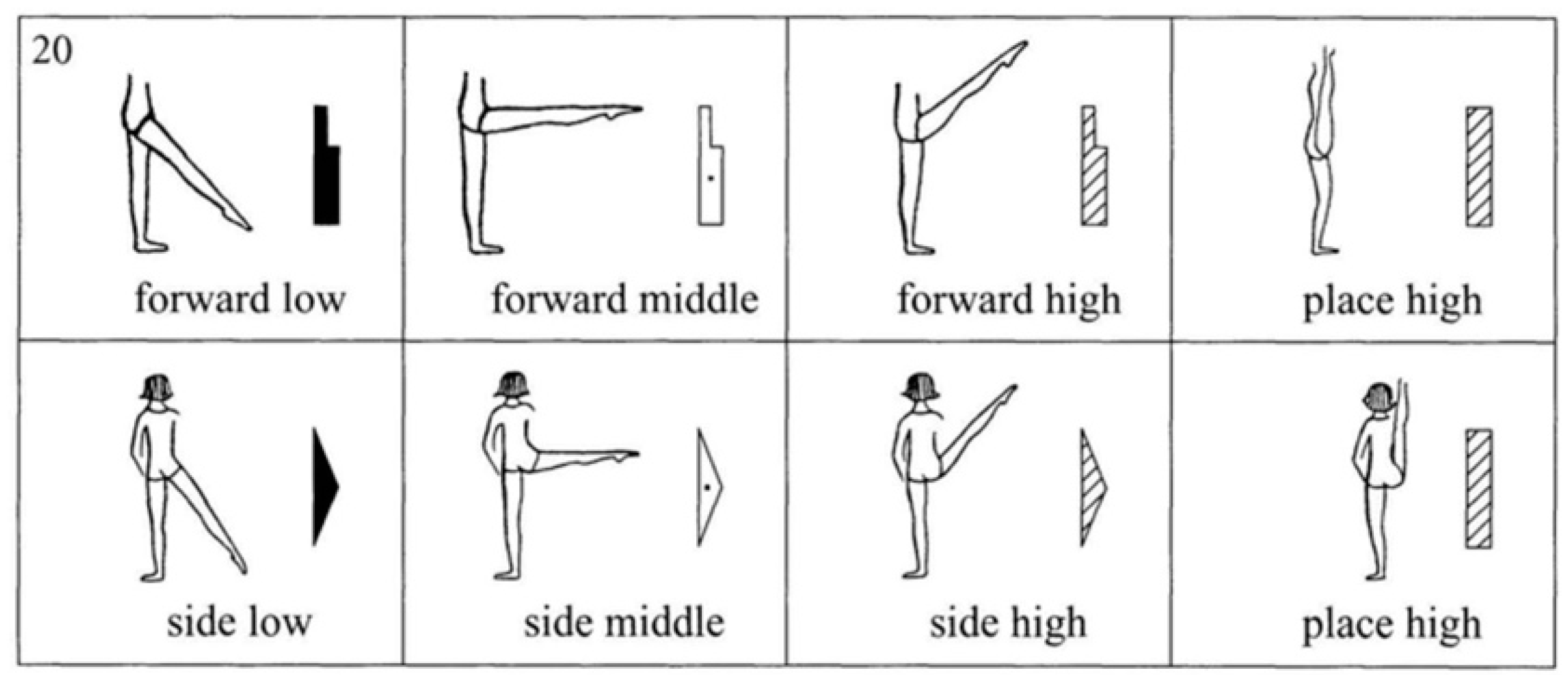

These basic shapes can subsequently take three different types of shading to indicate three possible levels of movement (Figure 7). A hatched shape means movement at a high level or limbs extended straight upwards, an empty shape with a dot in it means movement at a middle or horizontal level, and a filled shape means movement at a low level or limbs extending straight down.

Figure 7.

Levels for leg gestures in Kinetography. Created by Ann Hutchinson Guest, used with permission from the author.

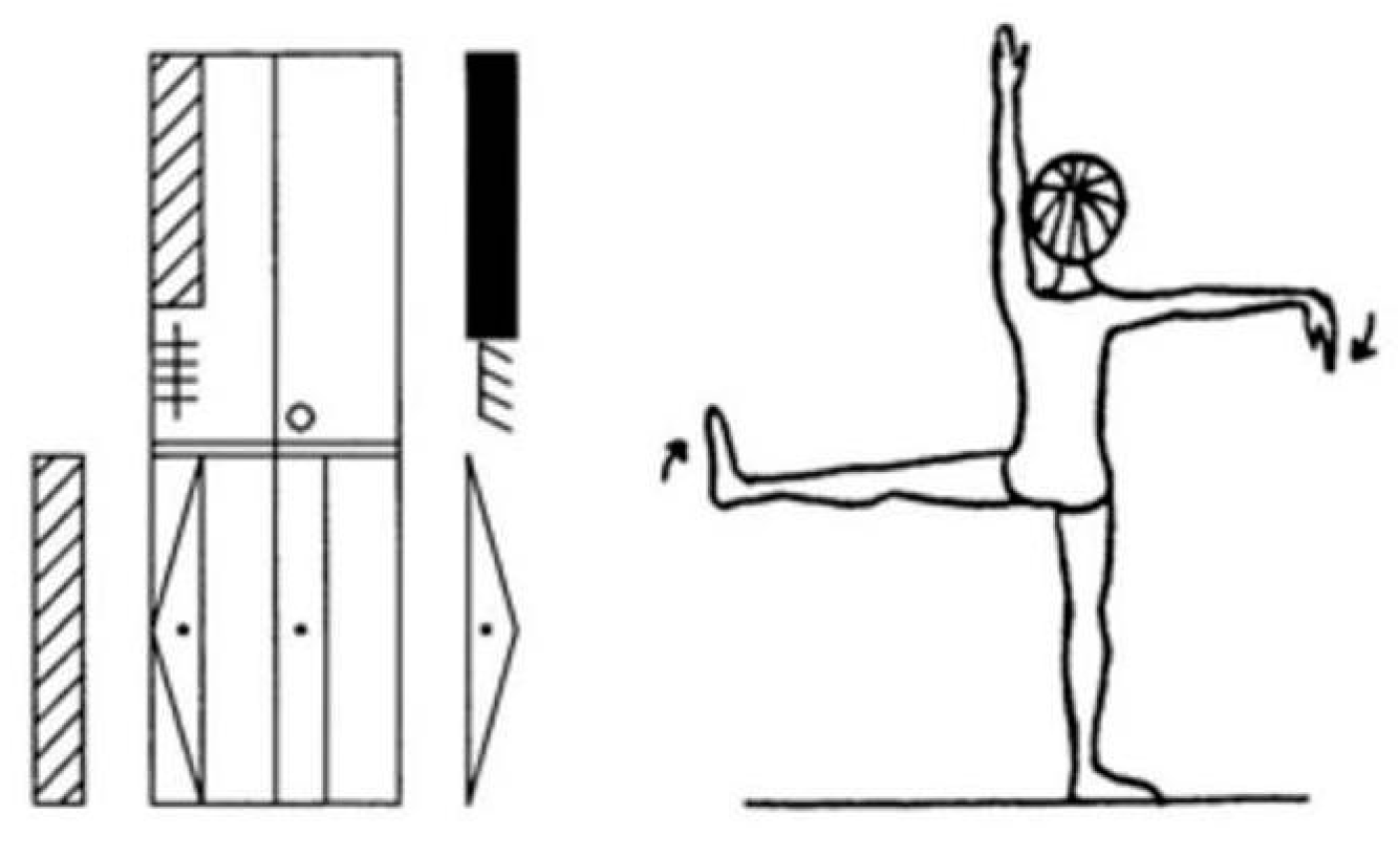

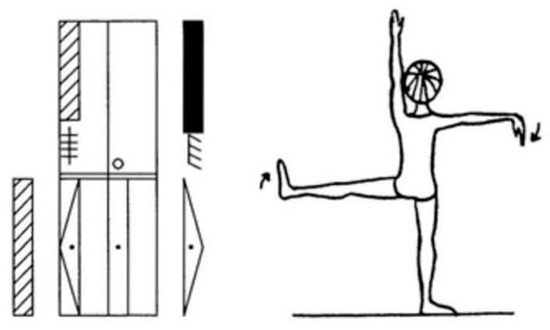

Smaller body parts can be activated using a variety of supplementary symbols, such as a slanted E-shape for movement of the hands or four small horizontal lines for movements of the feet (Figure 8). The detail of this information can be extended as far as individual fingers and toes.

Figure 8.

Example of hand and foot actions notated in Kinetography and shown in context. Created by Ann Hutchinson Guest, used with permission from the author.

Finally, different lengths of these shapes indicate the duration of each movement. More elongated shapes stand for prolonged gestures, while shorter shapes indicate fast progressions. The length of a musical note corresponding to that of a Laban rectangle can be determined at the beginning of a score; a quarter note usually corresponds to 1.25 cm in kinetographic notation. Unlike other dance notation systems, Kinetography hence already incorporates metered time into its script and does not need to be accompanied by a musical score. While Laban thus took musical notation as his point of departure, in its final stage, Kinetography is no longer reliant upon musical codifications of time.21 With this overview of its basic elements in mind, we can now turn to works from Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s early oeuvre and place them in direct comparison with examples of Rudolf von Laban’s Kinetography.

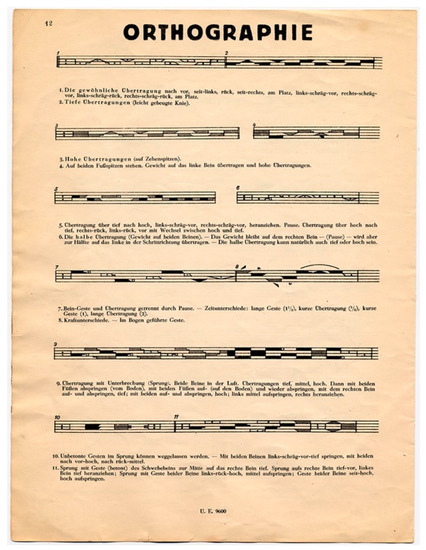

4. Curious Resemblances

Both in Taeuber-Arp’s Composition from ca. 1918 and in excerpts from Laban’s Schrifttanz publication, the viewer or reader is immediately reminded of musical staves (Figure 9 and Figure 10). Horizontal bands made up of five lines structure each composition. What is more, both appear to take an interest in the negative space between the lines. While in musical notation, notes can appear both on and between any two lines, Laban places his kinetic shapes solely into the interstices. Taeuber-Arp, in turn, broadens her lines into bands so that they become interchangeable with the interstice. In her Composition, space is treated not as a container to be filled, but as a shape in its own right.

Figure 9.

Excerpt from Rudolf von Laban’s journal Schrifttanz, volume 1. Vienna: Universal Edition, 1928.

Figure 10.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Composition, ca. 1918. Pencil and coating paint on paper. 30.7 × 25.6 cm. Kunst Museum Winterthur. Donation by Marguerite Arp-Hagenbach, 1977. © SIK-ISEA, Zürich (photo Philipp Hitz), used by permission.

Yet the reference to musical notation is only partially appropriate, since the excerpts from the journal Schrifttanz are a rather unique example of kinetographic notation in five horizontal lines. These initial presentations are most likely intended as an introduction for the novice by way of an analogy to music. In more comprehensive versions intended for dance practitioners, Laban’s notations are always arranged vertically, with staffs consisting of three lines rather than five (Figure 11). Taeuber-Arp’s embroidery design Composition à motifs d’oiseaux from ca. 1927–1928 features a vertically-oriented spatial arrangement reminiscent of this script (Figure 12 and Figure 13). The embroidery itself could of course also be viewed horizontally, but her handwritten notes suggest that she conceived of it as an upright composition. Bands of elongated rectangles are the main compositional structuring device. As opposed to her Composition from 1918, they here serve as containers for semi-circles, rectangles and triangles. Their spatial distribution further invites a reading of the elongated rectangles as arranged in pairs of two, and divided by a central axis—almost as if one indicated the left side, and the other, the right side of the body.

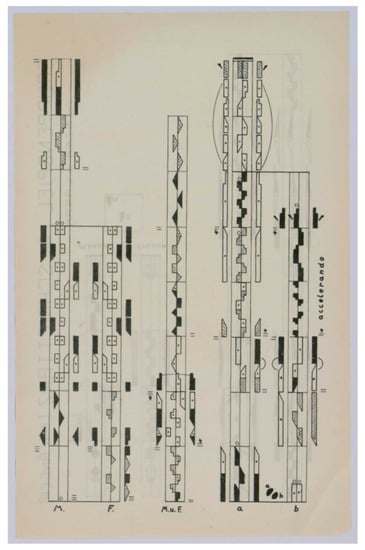

Figure 11.

Azra von Laban, Gruppenspiel für Schrifttanz, notated 1930–1931. Médiathèque du Centre national de la danse. Fonds Albrecht Knust. Donation by Roderyk Lange, used by permission.

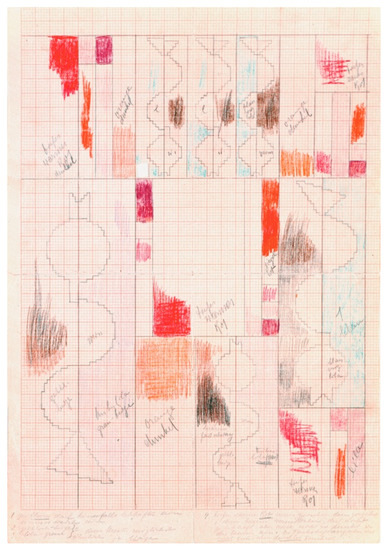

Figure 12.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Untitled (embroidery design for Composition à motifs d’oiseaux), ca. 1927–1928. Pencil and colored pencil on graph paper. 25.8 cm × 37.5 cm. Private collection. Deposited in Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau (photo Peter Schälchli), used by permission.

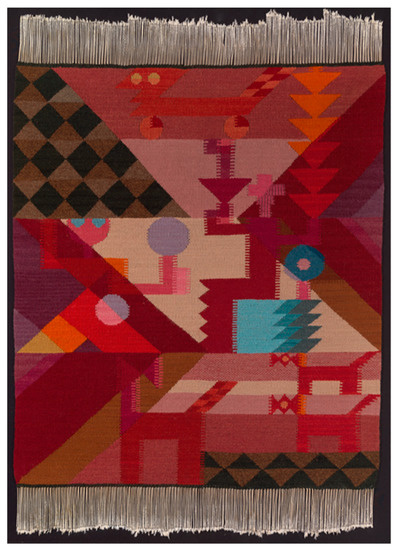

Figure 13.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Composition à motifs d’oiseaux, ca. 1927–1928. Petit-point embroidery, wool on linen ground. 25 cm × 35.5 cm. Private collection, used by permission.

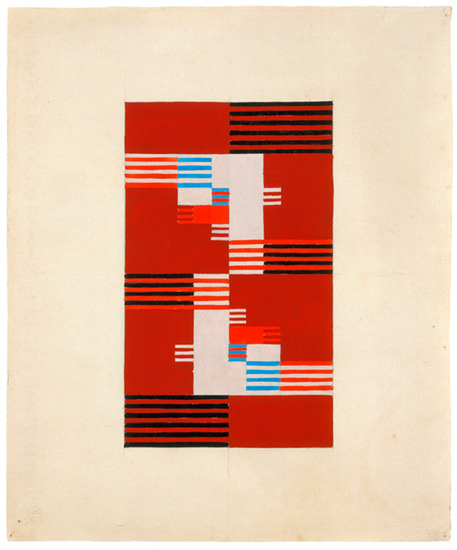

Other works from the same period contain symbols that would be immediately recognizable to a kinetographically literate eye. The red shapes in Composition pathétique à plans rectangulaires from 1928 (Figure 14), for instance, recall two “chimneys” that would indicate low-level forward movement on both supporting limbs. In Taeuber-Arp’s rug from 1921 (Figure 15), on the other hand, small hatchings around the outlines of her shapes repeat not only the rug’s physical structure, but also remind one of the hatchings that designate high level movement in Kinetography. Even more strongly do the diagonal hatchings in the lower right hand corner of the rug resemble the slanted E-sign indicating movements of the hand (compare Figure 8).

Figure 14.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Composition pathétique à plans rectangulaires, 1928. Colored yarn. 50 cm × 50 cm. Stiftung Arp e.V., Berlin/Rolandswerth, used by permission.

Figure 15.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Rug, Untitled, 1918. Wool, woven. 80 cm × 69.5 cm. Fondazione Marguerite Arp-Hagenbach, Locarno. © SIK-ISEA, Zürich (photo Philipp Hitz), used by permission.

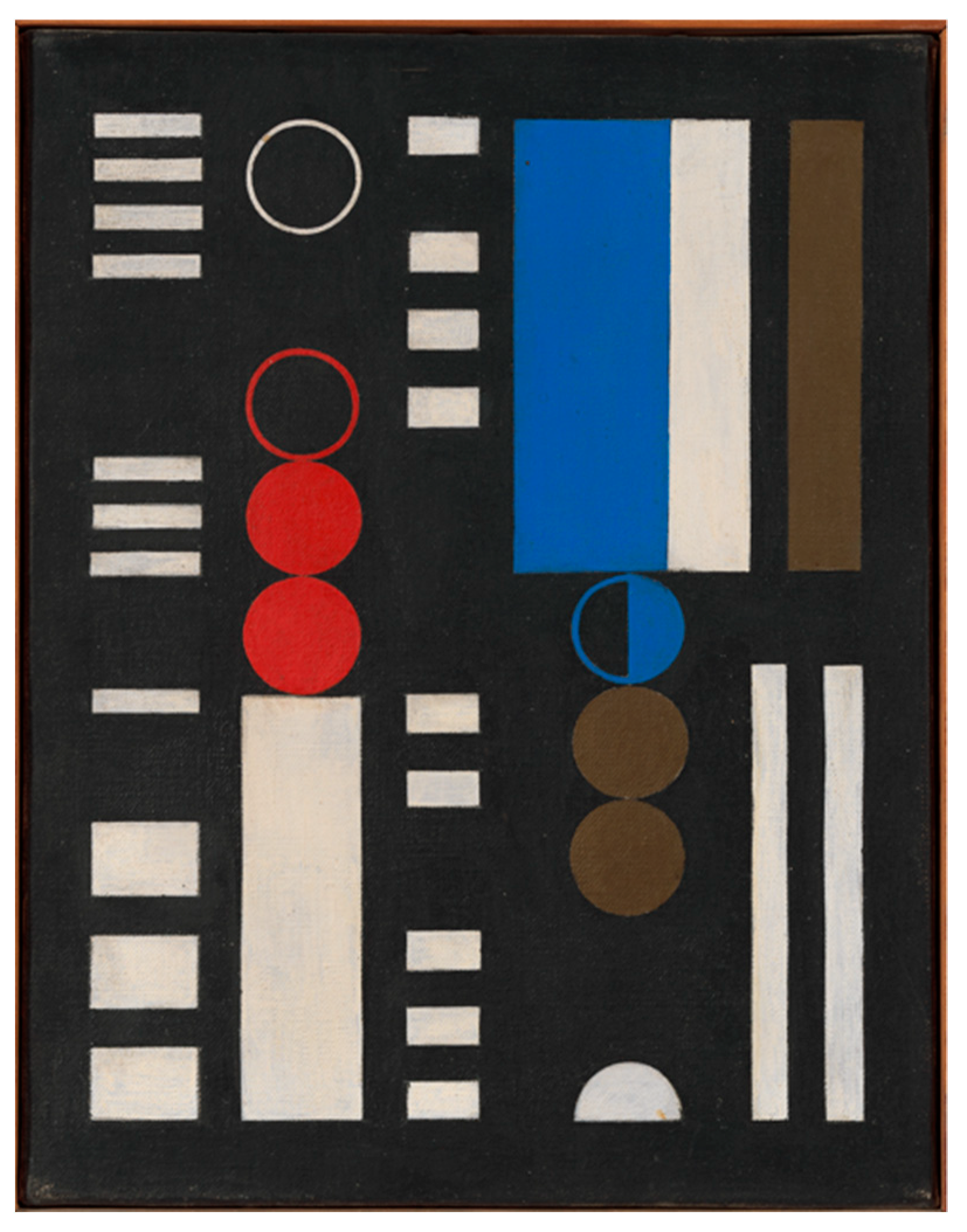

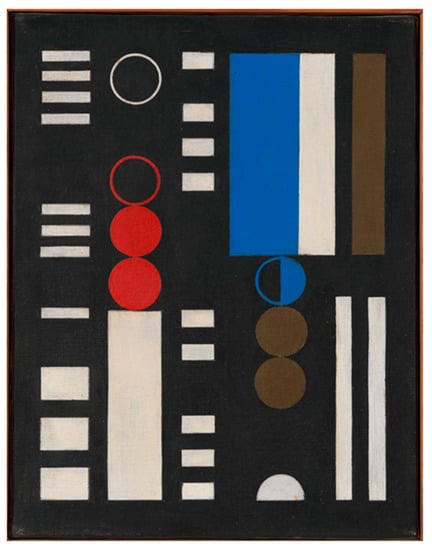

At times, themes carry over from one medium to another in Taeuber-Arp’s oeuvre. Her oil-on-canvas Composition verticale à rectangles, cercles et barres from 1930 continues to be structured by elongated rectangles and a quick, unevenly spaced succession of smaller geometric elements (Figure 16). Additionally, the introduction of a clear distinction between full and empty shapes, as it is the case with the circles, recalls Laban’s use of shading to indicate different levels of movement.

Figure 16.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Composition verticale à rectangles, cercles et barres, 1930. Oil on canvas. 29 cm × 22.5 cm. Fondazione Marguerite Arp-Hagenbach, Locarno. © SIK-ISEA, Zürich (photo Philipp Hitz), used by permission.

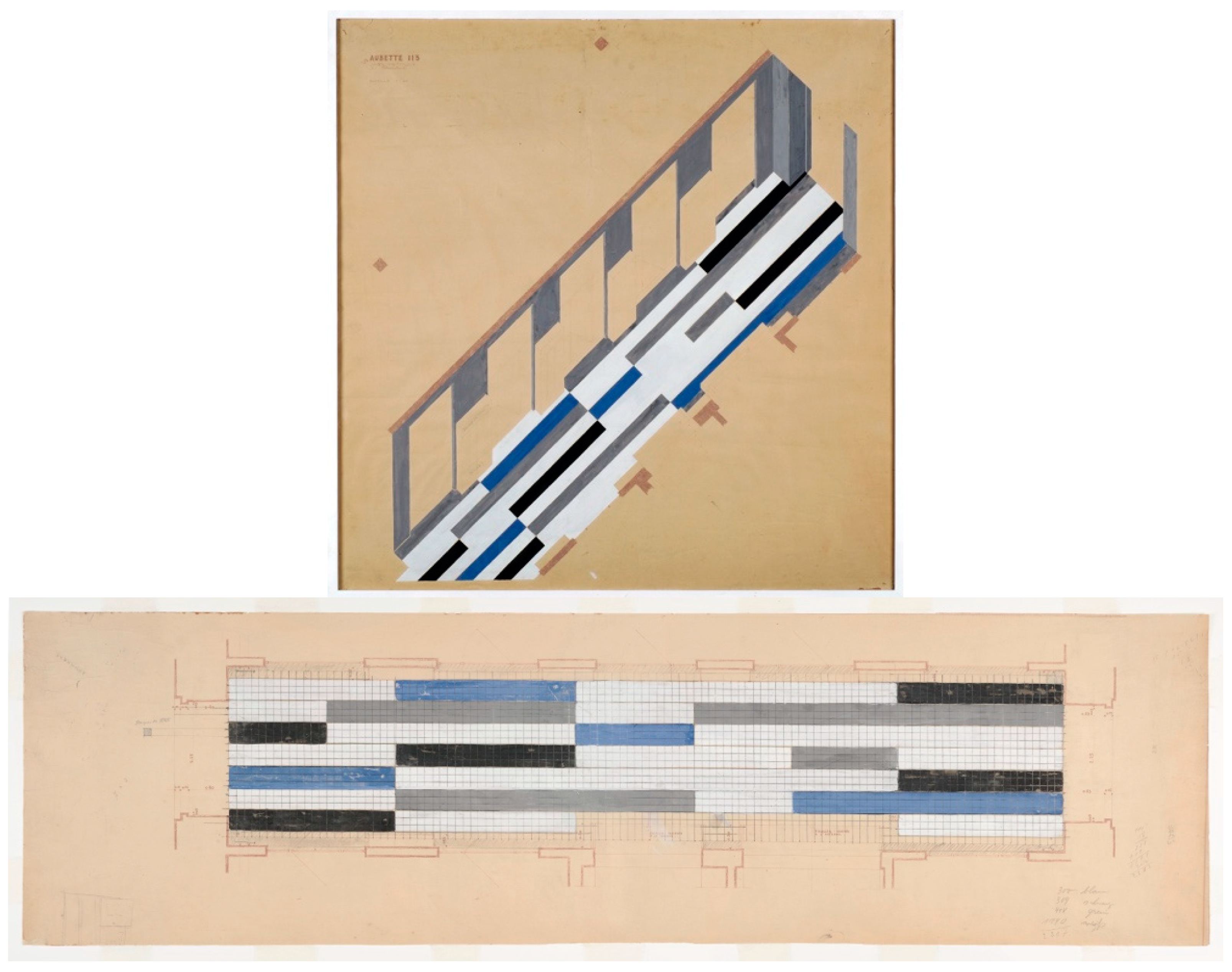

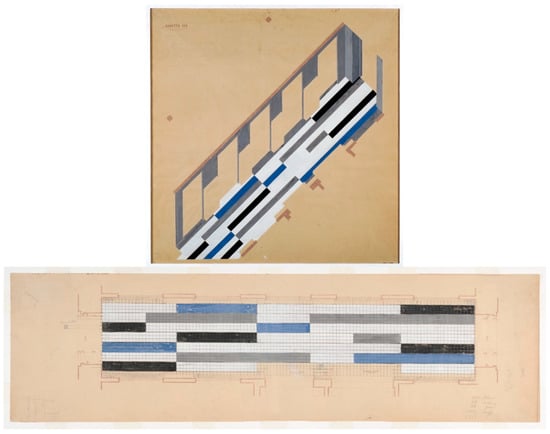

Finally, Sophie Taeuber’s plans for the hallway at the Aubette entertainment complex in Strasbourg from 1927 invite a final enticing comparison within an architectural context (Figure 17). Featuring a similar irregular arrangement of elongated rectangular shapes in blue, black and grey, her plans design a space to be moved across by visitors on their way to and from the Aubette’s dance hall. That this displacement of bodies is choreographed through a floor pattern of vertical bands—even if they are not further filled with geometric symbols—testifies one year before the publication of Schrifttanz to the strong parallels between Laban and Taeuber-Arps respective oeuvres.

Figure 17.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Aubette 113, 1927. Pencil and gouache on paper. Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain de Strasbourg, used by permission.

What is one to make of such striking parallels? Is it sheer chance, to return to Jill Fell, that Rudolf von Laban’s movement scores and Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s geometric abstractions exhibit such uncanny degrees of visual similarity? By now it will have become apparent that the most serious challenge that meets any attempts at establishing certainty over a direct influence is that of chronology. Laban did not publish his movement script until the late 1920s, when he was already living in Germany and no longer in Zurich. Whatever evidence we have about a potential direct influence often turns out to be questionable. A case in point is Hans Richter’s recollection of a ballet “drilled and written down by Käthe Wulff and Sophie Taeuber in Laban’s system of notation”, which would suggest that the latter was familiar with both its method and its aesthetics (Richter 1965, p. 71). Walburga Krupp, however, is right to caution us against an over-reliance on the Dadaist’s memories as historical documents (Krupp 2017, p. 158). Moreover, it is unlikely that Laban’s symbols of the mid-1910s were identical with those published in 1928. The question about Rudolf von Laban’s influence on Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s visual practice can therefore not be answered with certainty.

More fruitful might be the reverse question. We know of several occasions in which Taeuber-Arp exhibited her work in Zurich between 1917 and 1919; Laban’s wide-ranging creative endeavors and his personal interest in the visual arts substantiate the assumption that Laban had encountered his dance student’s work in the applied arts.22 It would be less far-fetched, then, to claim a place for Sophie Taeuber-Arp as a prominent figure amongst the ranks of Rudolf von Laban’s influences.23

The approach this paper takes, however, is yet a different one. The most productive solution, it argues, is to go beyond any attempt at enforcing strict causal connections, no matter their directionality. Bibiana Obler has taken such a stance with respect to the parallel careers of Sophie Taeuber-Arp and her husband Hans Arp. She writes that “it is easy to become mired in questions of influence, but the attempt to distinguish their contributions is not only futile, it is beside the point” (Obler 2014, p. 138).24 A similar case can be made about the connections between Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Rudolf von Laban. The final section of this paper thus turns away from questions of influence, proposing instead to understand these visual resemblances as indicators of underlying convergences in the artists’ creative values and approaches to artmaking. In both cases, these most clearly emerge in their respective pedagogical writings.

5. Pedagogical Juxtapositions

One of the primary functions of Kinetography was of course as a device to facilitate the learning of choreography. To understand not only the full degree of innovation but also some of the theoretical underpinnings of Laban’s invention, four central aspects deserve to be highlighted. First, Kinetography distinguishes itself from preceding models of dance notation insofar as it is both comprehensive and universal: every form of movement can be captured and all types of dance can be recorded. In the introductory notes to the 1928 user manual from the journal Schrifttanz, Laban asserts that Kinetography provides the reader with a “full and complete presentation of all movement recording possibilities” (Laban 1928b, p. 3). Not only the highly skilled dance master, but anyone who has become literate in this script can teach themselves the recorded steps, which are of course not restricted to modern expressionist dance.

Second, Kinetography, according to Laban, ensures the regulated and accurate transmission of dance from one body to another because it “keeps choreographic invention free from distortion by busy imitators… [to] the effect of preserving the integrity of original works” (Laban 1956, pp. 18–19).25 Laban’s objective is to eliminate imitation from the ways dance is circulated; in other words, his pedagogic model is anti-mimetic. Movement no longer travels from one body to another through the imprecise and uncontrollable act of copying the steps of the dance master. Rather, the originality of a choreography is preserved in a script and can be activated at a later point only through a meticulous and professional hermeneutic effort.

Third, this careful analysis necessarily makes the “movement progression more precise and relieve[s] it of any indistinctness, which [would] make the dance idiom unclear and additionally monotonous,” so Laban (Laban 1928a, pp. 4–5). Kinetography not only allows dance to be reproduced with a much higher fidelity, but it makes the quality of the movement itself more refined. Recall here Mary Wigman’s account from 1914 that “every movement had to be done over and over again until it was controlled and could be analyzed” (Wigman 1983, p. 303). Laban refers to this aspect of refining dance through its notation as the “mental aspect”, and emphasizes it as “far more important” than the comparatively straightforward task of scripting gestures (Laban 1928a, pp. 4–5).

The fourth point is not explicitly formulated in Laban’s writings, and yet it is perhaps the most remarkable aspect of his invention. This is the fact that Kinetography no longer contains even a vestige of anthropomorphism. While prior movement notation systems featured symbols with a strong likeness to the shape of the human body—no matter how stylized—, such figures are thoroughly eliminated in Laban’s model.26 An uninformed viewer encountering such a score out of context could not fathom that it describes the displacement of human limbs. Ann Hutchinson Guest, Laban-student and founder of the American Dance Notation Bureau, explains: “While the direct visualization of stick figure drawings or visually based systems appeal to many people, direct representation is impractical for converting movement into drawings on paper except at a simple level. In any comprehensive system, information must be abstracted and converted into symbols” (Hutchinson Guest 2005, p. 11). At the heart of Kinetography thus lies an impulse to abstract information about the body’s motions into simple, repeatable geometric shapes.

This impulse to abstract movement seems, at first glance, to stand in contradiction with expressionist dance’s investment in corporeality. There exists indeed a paradoxical relation between the attempt to refine and control movement through writing and expressionist dance’s aspirations to free the dancing body by allowing it to move to its own rhythms. Mark Franko has already noted this tension: “But, movement was inconceivable in these terms [of improvisation and of ecstasy] without movement analysis, through which one separates out and considers in isolation the body’s relation to space, time, qualities of energy” (Franko 2012, p. 294). It is ironically only the meticulous scrutiny of isolated movement that allows for the improvisatory freedom of expressionist dance. A similar tension can be observed to run through Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s artistic oeuvre. In her case, this is usually posited as the contradiction between the freewheeling lawlessness of her performances in Dada contexts and the conscientious labor invested in her seemingly static textile creations. But before we can turn to this paradox, a closer reading of Taeuber-Arp’s own writings is called for.

The only extant publications by Taeuber-Arp are two pedagogical texts. Although these writings deserve a closer study for their own sake, spatial limitations make a comprehensive engagement with these texts impossible in this paper. The following paragraphs will thus merely single out four salient points, and demonstrate their resonances with the central elements of Laban’s teaching highlighted above.

First, Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s writing is underpinned by a conviction that the urge to beautify is deeply rooted in humankind. It is a primeval, or one could add, a universal attribute. Offering a set of composition exercises, she reassures her readers that they will “increase students’ expressive abilities in form and color, as different as their innate talents may be” (Taeuber-Arp and Gauchat [1927] 2009, p. 170). With a basic training in color theory and compositional strategies, anybody has the creative capacities to devise embellishment.

Second, imitation once again appears as the foe of all honest and pure creation. “Lifeless, embarrassing copying” does not allow students to grasp the essential beauty inside any object, Taeuber-Arp writes; the aim is rather to give expression to the way this beauty is “truly, personally experienced” (Taeuber-Arp [1922] 2009, p. 163). Whereas her overall pedagogical program leaves ample space for freedom to experiment, the facile and unimaginative approach of mimesis is excluded from the gamut of legitimate creative strategies.27

Third, a sense of diligence and attention to the most minute detail pervades her didactic texts. For example, Taeuber-Arp writes in praise of “conscientious labor” (Taeuber-Arp and Gauchat [1927] 2009, p. 167) and emphasizes the need to “distinguish between the essential and the inessential” (Taeuber-Arp [1922] 2009, p. 163). She is convinced of the existence of an “instinct for perfection” (Taeuber-Arp and Gauchat [1927] 2009, p. 168), and any closer analysis of her work reveals that this instinct was very much her own.

Finally, it is perhaps surprising that the word “abstract” is never explicitly mentioned in Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s texts. The interpretative leap this calls for, however, is a rather small one. Throughout the introduction to the 1927 Guidelines for Drawing Instruction, Taeuber-Arp and her co-editor Blanche Gauchat advocate against a superficial, pasted-on ornamentation imitative of patterns in nature, and in favor of “pure—and therefore beautiful—functional form” (Taeuber-Arp and Gauchat [1927] 2009, p. 167). In Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s own work, this call for purity, beauty and functionality translates primarily to forms that are abstract rather than representational, even if it does so less as a matter of dogma than one of inclination.28

Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Rudolf von Laban thus share in their pedagogical-theoretical writings a belief in the universality of creative expression, a valuing of precision, a rejection of mimesis and an impulse towards abstraction. It is these overt resonances between the artists’ respective pedagogical agendas—and not merely the visual resemblances between their works—that put Taeuber-Arp’s abstract compositions into an intrinsic relation with Laban’s contemporaneous engagements with bodily movement.

The convergence of these two artists through their pedagogical writings is significant for several reasons. First, such an approach provides a more concrete understanding of the relationship between movement and form in Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s artistic career. Other studies have already attempted to overcome an overly neat separation between the artist’s interest in bodily movement and that in nonfigurative composition as two entirely distinct forms of artmaking. However, the prevalent narrative in current scholarship claims that Taeuber-Arp’s dance practice manifests itself in the incorporation of dynamic lines, slanting shapes, and the more animated quality of her work.29 Instead, the visual and pedagogic resemblances with Laban’s movement notation reveal that the dancing body is implicated precisely in Taeuber-Arp’s most exacting and static abstract geometrical compositions.

This is not to argue that her work therefore contains a hidden Kinetography waiting to be activated; the latter would, admittedly, be quite a spectacular example of over-interpretation. At most, one could understand Taeuber-Arp’s abstractions as a movement script in a very expanded sense: along such lines, her applied artworks would figure as the material traces of her compositional exercises—notating, so to speak, the movement of her hands as they carefully cross-stitch, embroider, and arrange patterns on the page.

Whether Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s abstract works express movement through some form of notation or not was not this paper’s aim to decide. It did attempt to show, however, that both Laban and Taeuber-Arp’s aesthetic values give rise to a seemingly paradoxical co-presence of an impulse to abstract and an investment in corporeality in their respective oeuvres. What is at stake in such a reading is to demonstrate that the turn to nonfigurative shapes in early twentieth-century Europe was not a matter of the elimination of the human body. The asymptotic relationship between the lives and works of Rudolf von Laban and Sophie Taeuber-Arp instead disrupt a common notion of early abstraction as cerebral rather than corporeal: in the work of both artists, bodily movement and geometric form are co-constitutive, and not mutually exclusive phenomena.

6. Conclusions

Given the arguments presented in this paper, we may conclude that Sophie Taeuber-Arp occupies a unique role in the complex relationships between the Dada movement and the work of Rudolf von Laban. While aspects of Taeuber-Arp’s oeuvre are certainly influenced by her involvement in the circles of Zurich Dada, her pedagogical writings about the applied arts resonate much more strongly with the theoretical investments of Rudolf von Laban. Both emphasize dedication and practice over chance creation, individual virtuosity over anonymity, and precision over chaos. It is these pedagogical and conceptual concordances that finally make clear why the resemblances between Taeuber-Arp’s and Laban’s visual languages are not a matter of pure coincidence.

Putting this main conclusion in a larger context, this sheds new light on the manifold interactions between Dada and expressionist dance, asking us to revise our assumptions about their supposedly distinct artistic agendas. Most importantly, however, this paper hopes to have added insights to early geometric abstraction’s intimate ties not only to the applied arts, but also to the dancing body. This is only one possible way in which to reconsider the role of the corporeal in the history of modernism.

The claims of this paper are based on evidence derived from comparisons of the creative work and theoretical writings of the two artists it discusses. The validity of its claims thus does not depend on any speculations about direct influences of Rudolf von Laban on Sophie Taeuber-Arp or vice versa. Instead, the paper made use of an alternative framework for thinking about the vexed question of artistic influence in the history of art and dance. Regarding the experimental environments of Munich, Ascona and Zurich in the early 20th century as the common ground for the joint emergence of a system of dance notation and of geometric abstraction, one might understand them as simultaneous, co-responding, different but not separate, artistic phenomena.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Anne Umland and her research assistants for their encouragement to publish this text. Thank you also to the students in the seminar on Sophie Taeuber-Arp for their feedback and stimulating discussions. This paper has benefited greatly from the incisive comments by its reviewers and by the editors of this Special Issue, as well as the proofreading of Andrea Lindmayr-Brandl and Johannes Brandl. I am grateful to Ann Hutchinson Guest for her responsiveness and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interests.

References

- Andrew, Nell. 2014. Dada Dance: Sophie Taeuber’s Visceral Abstraction. Art Journal 73: 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhalter, Sarah. 2014. Kachinas and Kinesthesia: Dance in the art of Sophie Taeuber-Arp. In Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Today Is Tomorrow. Edited by Thomas Schmutz. Aarau: Aargauer Kunsthaus, pp. 226–32. [Google Scholar]

- De Weerdt, Mona, and Andreas Schwab, eds. 2017. Monte Dada—Ausdruckstanz und Avantgarde. Bern: Stämpfli Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Demos, T.J. 2005. Zurich Dada: The Aesthetics of Exile. In The Dada Seminars. Edited by Leah Dickerman and Matthew S. Witkovsky. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, pp. 7–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dickerman, Leah. 2005. Introduction. In The Dada Seminars. Edited by Leah Dickerman and Matthew S. Witkovsky. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dörr, Evelyn. 2004. Rudolf Laban: Das choreographische Theater. Norderstedt: Books on Demand. [Google Scholar]

- Dörr, Evelyn. 2008. Rudolf Laban: The Dancer of the Crystal. Lanham: The Scarecrow Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fell, Jill. 1999. Sophie Täuber: The Masked Dada Dancer. Forum for Modern Language Studies 35: 270–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, John. 1977. The Influences of Rudolph Laban. London: Lepus Books. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, Hal. 2003. Dada Mime. October 105: 166–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franko, Mark. 2012. Danced Abstraction: Rudolf con Laban. In Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925: How a Radical Idea Changed Modern Art. Edited by Leah Dickerman. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson Guest, Ann. 1989. Choreo-Graphics: A Comparison of Dance Notation Systems from the Fifteenth Century to the Present. New York: Gordon and Breach. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson Guest, Ann. 2005. Labanotation: The System of Analyzing and Recording Movement, 4th ed. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Krupp, Walburga. 2017. Sophie Taeuber-Arp als Tänzerin und Dadaistin: Eine Wunschvorstellung der Rezeption? In Monte Dada: Ausdruckstanz und Avantgarde. Edited by Mona de Weerdt and Andreas Schwab. Bern: Stämpfli Verlag, pp. 149–64. [Google Scholar]

- Laban, Rudolf. 1928a. Grundprinzipien der Bewegungsschrift. Schrifttanz 1: 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Laban, Rudolf. 1928b. Vorwort. Schrifttanz 1: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Laban, Rudolf. 1956. Principles of Dance and Movement Notation. London: Macdonald and Evans. [Google Scholar]

- Lanchner, Carolyn. 1981. Sophie Taeuber-Arp: An Introduction. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, Roderyck. 2011. Laban and Movement Notation. In The Laban Sourcebook. Edited by Dick McCaw. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 155–66. [Google Scholar]

- McCaw, Dick, ed. 2011. The Laban Sourcebook. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Obler, Bibiana K. 2014. Intimate Collaborations: Kandinksy & Münter, Arp & Taeuber. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, Hans. 1965. Dada: Art and Anti-Art. New York: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Ruprecht, Lucia. 2017. Vibrierende Körper in Dada und Ausdruckstanz. In Monte Dada: Ausdruckstanz und Avantgarde. Edited by Mona de Weerdt and Andreas Schwab. Bern: Stämpfli Verlag, pp. 121–31. [Google Scholar]

- Stroeh, Greta. 1989. Biographie. In Sophie Taeuber. Paris: Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. [Google Scholar]

- Taeuber-Arp, Sophie. 2009. Remarks on Instruction in Ornamental Design. In Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Avant-Garde Pathways. Málaga: Museo Picasso, pp. 162–65. First published 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Taeuber-Arp, Sophie, and Blanche Gauchat. 2009. Guidelines for Drawing Instruction in the Textile Professions. In Sophie Taeuber-Arp: Avant-Garde Pathways. Málaga: Museo Picasso, pp. 166–73. First published 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Vögele, Christoph. 2002. “You beheld the world with devotion”: On the Question of Reality in the Works of Sophie Taeuber-Arp. In Variations: Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Works on Paper. Heildberg: Kehrer Verlag, pp. 26–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wigman, Mary. 1983. My Teacher Laban. In What Is Dance? Edited by Marshall Cohen and Roger Copeland. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | In this essay, I am using the term Kinetography instead of Labanotation, since this was the terminology used at the time. For a discussion on the evolvement of Labanotation since its invention, see (Hutchinson Guest 2005, pp. 434–39). |

| 2 | Compare, for instance, Carolyn Lanchner’s observation that “notations for the dance can resemble the patterns of abstract painting” (Lanchner 1981, p. 11). Likewise, Mark Franko asserts that dance “notation itself is a visual abstraction of movement” (Franko 2012, p. 293). While Franko does mention that “the artist Sophie Taeuber… was also one of his students”, he does not explore the potential exchange between the two (ibid., p. 292). I am grateful for a reviewer of this paper for bringing this note to my attention. |

| 3 | Rudolf von Laban was born in 1879 in Bratislava, in the former Austria-Hungary, into an aristocratic family. He continued to receive financial support from his mother during his economically adventurous artistic endeavours which brought him onto the verge of bankruptcy more than once. Taeuber-Arp was born in 1889 in Davos, Switzerland, into a middle-class family. She spent much of her early career teaching at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Zurich to ensure her own and her husband Hans Arp’s financial security. |

| 4 | For a more thorough account of Rudolf von Laban’s early career, see (Dörr 2008, pp. 9–78). |

| 5 | This group comprised Hugo Ball, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco, Richard Huelsenbeck, Jean Arp, Emmy Hennings, Hans Richter and others. |

| 6 | Nell Andrew justly cautions against such an over-emphasis on the performance ephemera, as they run the risk of diminishing “the significance of her dancing body” (Andrew 2014, p. 17). Walburga Krupp equally warns against a historical over-reliance on the recordings and recollections of the Dadaists, whose memories, she writes, often remained vague and heavily informed by their own aesthetic agenda (Krupp 2017, p. 158). |

| 7 | See, for example, (De Weerdt and Schwab 2017). |

| 8 | For instance, (Fell 1999, p. 277). Laban was indeed in the audience when Taeuber-Arp supposedly performed with this mask at the opening night of Galerie Dada. This is the only mention I have come across of a potential direct visual influence of Taeuber-Arp on Laban. However, since Marcel Janco most likely designed the costume, this cannot truly be counted as an influence of Taeuber-Arp herself. |

| 9 | For instance, (Krupp 2017, p. 154). |

| 10 | If one does decide to trust the credits of the one extant photograph documenting her dance performances (Figure 1), it is important to note that the Laban student Sophie Taeuber-Arp is depicted in a highly restrictive costume typical of Dada. What this conjunction meant for her dance style cannot be determined with any certainty, but one might imagine her performance as the moment in which two diverging aesthetics intersected in a single dancing body. Indeed, Jill Fell acknowledges the conflicting testimonies that describe her performances as both taking “a mocking stance more appropriate to Dada” and in terms of a “more Labanesque style, representing natural phenomena” (Fell 1999, p. 277). If anything, these accounts are proof to Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s liminal position between the circles of Laban and those of the Dadaists. |

| 11 | The respective relationships of the Dadaists and the Laban circle to mimesis will be discussed at a later point in this paper (see footnote 29). |

| 12 | For a study of the ways in which the condition of exile influenced the Dadaist aesthetics, see (Demos 2005). |

| 13 | Leah Dickerman, too, pushes back against the adjectives “nihilistic”, “antibourgeois” and “antiart” that are often unthinkingly reproduced by Dada scholarship, in favor of a more nuanced investigation of its “formal procedures” and “social semiotics (Dickerman 2005, p. 2). |

| 14 | In “Sophie Taeuber-Arp als Tänzerin und Dadaistin: Eine Wunschvorstellung der Rezeption?”, Walburga Krupp (2017) argues that the labelling of Taeuber-Arp as a Dada dancer is a posthumous phenomenon occasioned by the celebratory yet vague reminiscences of her male colleagues. In reality, Krupp argues, it was only with her marionettes from 1918, and not so much through her dances, that Taeuber-Arp gained recognition in the Dada circles (Krupp 2017, p. 163). |

| 15 | Bibiana Obler has argued for a similar liminal position of Sophie Taeuber-Arp between the poles of individuality and anonymity. While it is true that the artist’s collaborative works with her husband Hans Arp question individual authorship and erase the intervention of the artist’s hand, Obler writes that these works “stand apart from even their closest counterparts in the respective oeuvres of their makers” (Obler 2014, p. 140). Indeed, while Taeuber-Arp’s masked performances in Dada circles did evince a desire for anonymity, in her applied arts practice she did not shy away from “identify[ing] her art with her name”, for instance by “advertis[ing] her name prominently” through a signature (ibid., p. 151–52). The authorship she staked a claim to, however, is “not that of artistic genius, but of an egalitarian model of competence” (ibid., p. 144). This paper is aligned with Obler’s careful attempts to resist the conflation of Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s work with that of her husband and his Dada colleagues. |

| 16 | In a letter to his friend Hans Brandenburg from 1918, quoted in (McCaw 2011, p. 5). |

| 17 | These documents were first published in the essay “Grundprinzipien der Bewegungsschrift” in the journal Schrifttanz (Laban 1928a, pp. 4–5). Schrifttanz was founded in 1928 and comprised eleven issues and two additional booklets, explaining and publicizing the new movement notation. |

| 18 | Quoted in (Dörr 2008, p. 43). |

| 19 | For an overview of the history of dance notation, see (Hutchinson Guest 1989). |

| 20 | Of course, Kinetography does not have a complex grammar as other human languages, and speakers are not able to communicate a full range of thoughts or feelings through it. Nevertheless, the claim that dance can be conceived as a form of language cannot easily be dismissed. For some introductory notes on this long-standing debate, see (Hutchinson Guest 2005, p. 14). |

| 21 | This overview of the mechanics of Kinetography is a condensation of the helpful introduction by Ann Hutchinson Guest (2005, pp. 17–33) in Labanotation. |

| 22 | These include the exhibition “Raumkunst” at the Alte Tonhalle Zurich and the exhibition “Schweizerische Expressionisten” at the Kunsthaus Zurich in late 1918 and early 1919 (Stroeh 1989, pp. 124, 127). |

| 23 | In The Influences of Rudolf Laban, John Foster (1977) provides such a genealogy consisting of a series of all-male dance masters with the exception of Isadora Duncan and Loie Fuller. |

| 24 | Methodologically, this paper thus shares Bibiana Obler’s critique of attempts to write a history of women artists that reproduces uncritically the masculine values of originality and uniqueness. Obler writes that “the tendency to champion underappreciated artists also lends itself to skewed perspectives, turning anxieties of influence into games of one-upmanship” (Obler 2014, p. 18). It is a game of one-upmanship that this paper intends to bypass by turning its back to a debate about influence between Rudolf von Laban and Sophie Taeuber-Arp. Thank you to a reviewer for pointing me to Obler’s text. |

| 25 | This and all following passages quoted from Laban’s Principles of Dance and Movement Notation (1956) are translations taken from (McCaw 2011). |

| 26 | It is of course possible to argue that the central symmetrical line that divides the script into a right and a left body side is still a sign of anthropomorphism. Nevertheless, comparisons with earlier notation systems such as the stick figure model, convey a sense of the extent to which direct representations of the body have been eliminated in Kinetography. |

| 27 | In this rejection of uncritical copying, the pedagogic projects of both Taeuber-Arp and of Laban overlap with the aesthetic-political values of the Dadaists. Dada’s fraught relation to imitation, understood as a reproduction of the “outside world, which, in 1916, was propelled into the catastrophe of World War I” has been the subject of prior scholarly debate (Demos 2005, p. 7). In this context, Hal Foster, conceives of Dada’s use of mime as a device for parody and mockery in the face of wartime trauma. Miming in Dada, Foster writes, was a “dialectic strategy” that risked “excessive identification with the corrupt conditions of a symbolic order” so as to “expose this order as failed, or at least as insecure” (Foster 2003, pp. 169–70). Whether a similar political stance motivated Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s or Rudolf von Laban’s rejection of ‘busy imitation’ and ‘lifeless copying’, however, remains open to speculation. |

| 28 | See Christoph Vögele’s observations that “only a few representatives of the early Moderns permitted the representational to coincide with the nonrepresentational so undogmatically as Sophie Taeuber-Arp” (Vögele 2002, p. 26). |

| 29 | See, for example, (Burkhalter 2014, p. 231). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).