Abstract

The decline of commercial letterpress printing and technological advances in industry were major influential factors with respect to the establishment of independent small presses in the United Kingdom (UK). Although unlike work from commercial, private or fine press printers, utilisation of the letterpress process embedded a phenomenological approach to artist-led publishing where physicality and experience of using the letterpress process was reflected within the practice of making artists’ books and printed matter. Major concepts and inclusion of tools, equipment, technologies and studio methods used in historical small publishing practice can be considered in relation to today’s practitioners making letterpress-printed artists’ books to understand how skills are learnt and developed to support the evolution of a reflexive approach within contemporary practice.

1. Introduction

In this essay, I examine the practice of letterpress printing within small press publishing and artists’ books to understand how practitioners learn and develop their creative work through their own bodies, by observation, experience, emotion and intuition. United Kingdom (UK)-based practitioners who set up their presses during the 1960s and 1970s had a particular position on letterpress printing within the small publishing practice. Many of the methods experienced interconnect with the physicality of space in terms of engagement within the scale of haptic practice. Through interviews, projects and observations of contemporary practitioners,1 it is evidenced that there is still a constant relationship between the perceiving body and intrinsic value in the construction of a letterpress-printed publication, positioning this practice as an integral part of current letterpress and book arts culture in the UK.

2. Background

In the cultural, political and social landscape of post-war Britain, creative and literary communities began to use new methods to commentate effectively, developing from “the world of sequence and connections into the world of creative configuration and structure” (McLuhan [1964] 2010). This broader definition and extension of art practice and visual expression subsequently led to new genres and art movements, thus creating, “a climate where verbal artworks could flourish, as well as intensive concern over theory for art” (Phillpot 2013). Innovators, often with a background of art school education (and thus an awareness of historical art movements and literary influences within the book) were drawn to the book form as artistic expression and began to practice non-traditional art forms, such as concrete poetry, mail art, performance and experimental music. They also sought alternative methods to the established gallery system in order to disseminate and exhibit their work.

At that time, typesetting within letterpress print production (which had been the dominant method of printing text-based matter since the fifteenth century) began its shift to becoming fully automated and then computerised. As industrial and commercial space was at a premium, the need arose for traditional older (slower) machines to be disposed of. This allowed creative practitioners access to presses and equipment and, in turn, had a major impact on freedom of expression and creative publishing practice, enabling total control over what could be produced, edition size, portability, autonomy, frequency of publication and inevitably bringing down publication costs for small press publishing.2 Therefore, throughout subsequent decades, sourcing machinery and print room tools and equipment for artist publishers became not only accessible but also available at knockdown prices or sometimes even free to the collector.

3. Small Publishing Practice and Artists’ Books: Developing the Field

Early creative engagement with the book by UK-based practitioners was demonstrated in a directly fluid, physical sense—setting up presses, publishing collectives and exhibition spaces—not only to engage with self-publishing practice but also to provide further commentary via artefacts and critical dialogue to a genre of word, image and print that had begun to surround the form of the book. Discussions through the literature began in the early 1970s around the book, as a space and artform (Phillpot 1972; Ehrenberg et al. 1972; Carrión 1975; Attwood 1976).

There were a number of presses set up in the 1960s and 1970s using letterpress printing as a process of production. These included the following: Wild Hawthorn Press est. 1961, Edinburgh: Ian Hamilton Finlay (1925–2006)/Jessie McGuffie (moved to Stoneypath in 1966); Tarasque Press est. 1964, Nottingham: Stuart Mills (1940–2006), joined in 1965 by Simon Cutts; Openings Press est. 1964, Gloucestershire: John Furnival/Dom Sylvester Houedard (1924–1992); Circle Press est. 1967, London: Ron King, Guilford, joined by John Christie, Ian Tyson, Roy Fisher (1930–2017), Birgit Skiöld (1923–1982) et al. (moved to London in 1988); Tetrad Press est. 1969, London: Ian Tyson, (closed in 1995, established ed.it 1995–); Weproductions est. 1971, London: Telfer Stokes, joined in 1974 by Helen Douglas (moved to the Scottish Borders in 1975); Moschatel Press est. 1972, Gloucestershire: Thomas and Laurie Clark (moved to Pittenweem, Scotland in 2002); Coracle Press est. 1975, London: Simon Cutts/Kay Roberts, joined in 1988 by Erica van Horn (moved to Tipperary, Ireland in 1997).

Many practitioners who were involved in artist-publishing during this time were not working in isolation. A network of practice was formed over time, and practitioners would publish each other’s work. Despite a sustained following with small press, alternative press, poetry press publications, etc. (since the 1960s), these practices were not extensively documented, as they existed outside the criteria that governed the majority of mainstream journals. So, the work produced and its surrounding dialogue tended to appear in little magazines3 or under individual press imprints.4,5 Helen Douglas of Weproductions explains6 the conditions that fuelled the decision to acquire printing presses and early publishing activities,

At that time publishing a book (via a printers) cost £500–£600 for 1000 copies (1976). Printing costs were going up, so having our own presses matched our own economic constraints—time was our investment—it would take a whole summer (3 months) to print a book. We never made 1000 copies when it was our own production. We would print 500–600.

[Letterpress] printing has an important quality to give. Litho does have an aesthetic but back then [in the 1970s] it seemed to have more of a bland normality to it [similar to digital printing now, in saturating the market]. It [litho] wasn’t talking about the hand as an expressionist tool in the making, of the printing. There’s no doubt that once we started printing our own books, the way that we printed (the books) became part of the aesthetic. The first press that we got was the letterpress, in 1978/79.7

The practice of publishing became a meeting place for all disciplines—poetry, art, writing, design, illustration, etc.—producing a global output of practice via small press publications, little magazines, etc. Practitioners who ran presses came from a variety of educational backgrounds with similar approaches to the book/artists’ books. This can be seen as contributing towards a breakdown of disciplinary boundaries or an encapsulation of them within this practice.

4. Embodiment of the Letterpress Process

The (letterpress) printing process, shifting from an industrial process to an artistic one, had implications on the application of the process in terms of its relationship to the printing press and the practitioner, progressing the associations of letterpress printing from historical notions of craft to contemporary theories of bodily experience and phenomenological perspectives. This way of thinking emulates how practitioners learnt the process of letterpress printing. So, rather than an elevated form or a process to only be used after one has many years of experience, they adopted the process into their way of life through physical practice and experience (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Helen Douglas (Weproductions) (2014) printing on her Vanderook no.4 at Deuchar Mill, Yarrow, Scotland. Photos courtesy of Helen Douglas.

In discussing Noë (2004) in regard to acting out and enacting our perception, Carreiro (2017) states that, “our bodies can formulate an understanding through physical engagement with a work, but also through the repetition of this action”. The movement of the body generates new perspectives by repetitive actions. This learning experience is integral to the craft of making letterpress-printed matter: the moving body adjusts practice over time through the repeated processes within letterpress printing and bookbinding.

The emergence of artists’ books and practitioners (during the 1970s) who employed a phenomenological approach to the letterpress process united the maker, process and form and emerged as a studio practice. This practice involved immediate surroundings, local and wider communities and reflected a creative and independent approach to the developing genre of the artist’s book and small publishing practice.

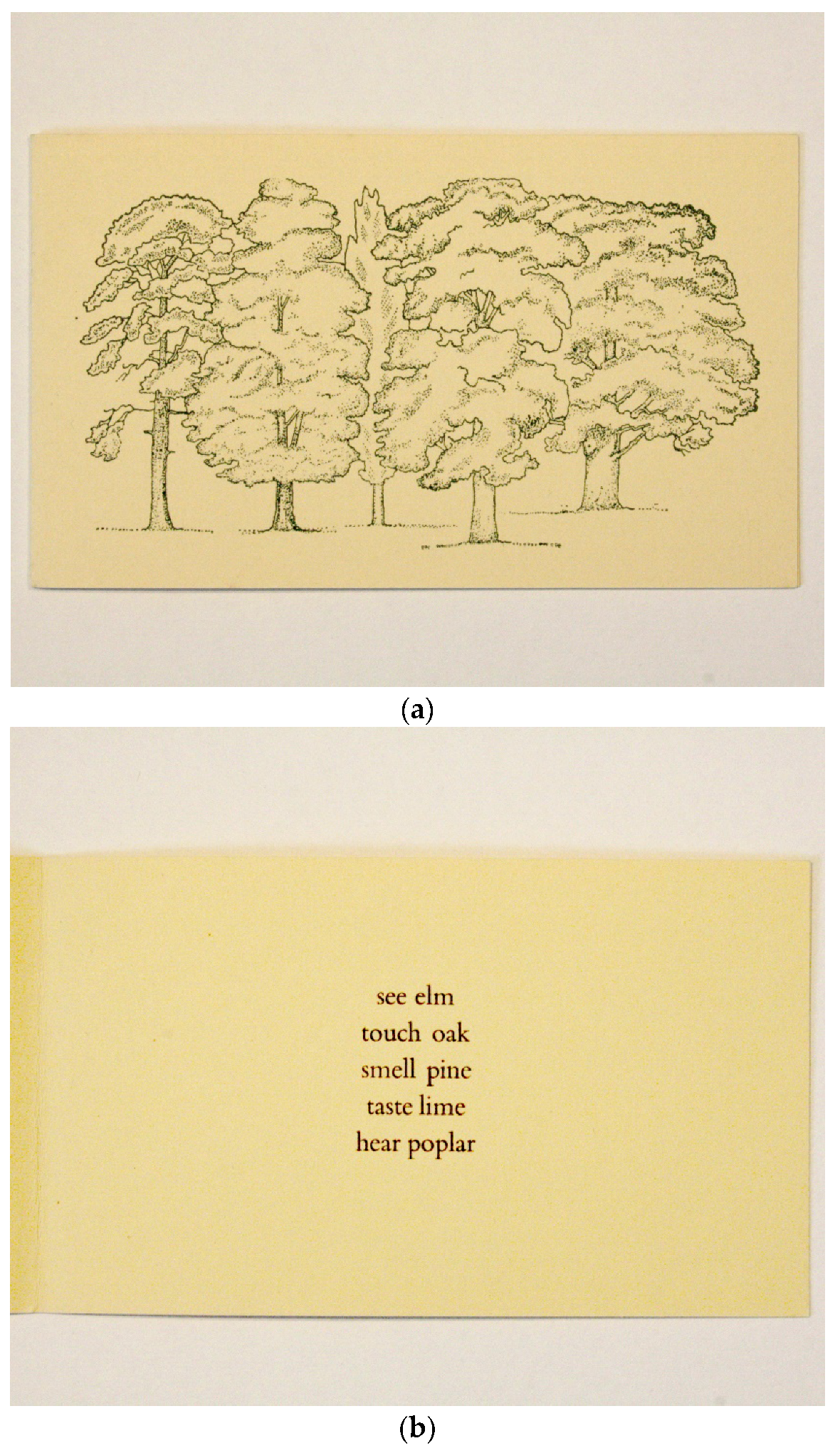

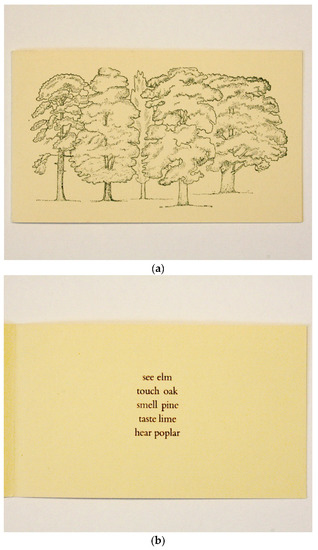

To evidence this new practice, we can examine a work by practitioners who embodied a phenomenological approach to making their work. The typesetting and letterpress printing process (physical and experiential practice) was embedded as part of Moschatel Press’ (Thomas A Clark and Laurie Clark) conceptual approach to making poetry, feeling the weight of each letter, the physicality of making words. As Laurie Clark attests, “the point was not to produce fine printing, we just wanted to print”.8 The evidence of this embodied experience is twofold in the resulting work, The Bright Glade, 1977 (Figure 2), in the artefact itself (the idea of time, the experience of making, in relation to words and sentences) and in the subject matter.

Figure 2.

(a) Clark, T.A. and Clark, L. (1977) The Bright Glade. [folded card printed letterpress] Moschatel Press: front. Photo courtesy of Laurie Clark. (b) Clark, T.A. and Clark, L. (1977) The Bright Glade. [folded card printed letterpress] Moschatel Press: interior. Photo courtesy of Laurie Clark.

The image and words are of equal importance, as is the structure of the card, the pacing of words, the position of words, colour and weight of paper stock, etc. One is forced to go backwards and forwards with the reading (experiencing) of the work, as a page separates image from word. The haptic space that surrounded the book was an important factor in its creation. The book was a tangible space—one that could be understood by physical making, feeling the weight and shape of each letter and the space of the printed word on the page, understood critically by reading, turning pages, feeling and looking, the body in close proximity with the object of the book.

To differentiate between the approach of the fine press printer and that of the letterpress practitioner within small press publishing and artists’ books, we can use Heidegger’s explication of the techné of practice (1977). Here, technology is seen and discussed as more than instrumentality or a set of practical skills (fine press); it exists as a way of understanding the world as part of poeisis:9 a way of bringing forth or a mode of revealing (small publishing practice/artists’ books). He explains poiesis as, “the blooming of the blossom, the coming-out of a butterfly from a cocoon, the plummeting of a waterfall when the snow begins to melt” (Heidegger and Stambaugh 1996)—the unfolding of a thing unto itself or when something moves away from itself to become another.

In breaking the boundaries and traditions of the process itself, artists and poets were using the same equipment and materials but not to print in the fine press tradition nor the large commercial edition. Books and printed matter were largely produced entirely by practitioners unlike many fine press or commercial editions, which were sent on to a professional bookbinder. This practice was practitioner driven (rather than publisher driven) with publications that imbued a bodily and visual language. This reflected the creative potential of the letterpress process within the artistic publishing practice. Fine press printing held a responsibility for the reading experience and the text in terms of skilled typography and good impression.10 In contrast, although using the same equipment and materials, this new approach evidenced an embodied experience with an alternative emphasis on process, content, use of materials and interdisciplinary practice, together within a conceptual framework. Practitioners were beginning to use their presses as creative tools to extend their practice.

There is also a connection here regarding the production of books from a social and collegiate-like perspective,11 as being part of practice not separate to it. Although there were complications with the notion of the ‘democratic multiple’ (Lyons 1985), as the physical possibilities of the whole hands-on production process of a book, card, printed object, etc. had to be taken into consideration from the outset, such as the edition size being bound up with what is feasible within one’s own set up, the priorities of these practitioners were, and still are, the physicality of the book, treating the book as imaginative space, the page as a framing device and the relationship of text and image, of turning pages, of narrative and of working together.

5. Contemporary Methodologies

Now, in our post-digital culture, letterpress-printed artists’ books position craft skills and tacit knowledge in a symbiotic relationship with digital media and the global social network. These practices give us a different type of focus when we engage with tangible materials, placing a higher value on craft, skills and the reflexive creative process (thus aligning a connection with the lineage of artist-publishers and artist’s bookmaking). This approach values taking time, looking, reading, creating with hand, eye and mind and considering the value of each element being integral to the understanding of the whole (explored in research of the photobook, Daly 2016). It also forms a direct link to craft and haptic aesthetics (interrogated by Mosely 2014), phenomenological approaches to letterpress printing (Pope 2004—The Bad Air Smelled of Roses) and how we engage with artists’ books. There is constancy between the perceiving body and the building of a letterpress-printed artist’s book, ‘building’, as so many of the processes experienced interconnect with the physicality of space. In terms of engagement within the scale of haptic practice, Tim Mosely (2014) discusses ‘assembling’ a book,

The depth of connection between the practitioner and all the associates (tools, materials, machines, etc.) of making is passed on to the reader in their experience of the book. It is known that someone has been there before them.Assembling a book involves firstly a phenomenal form perceived by the book’s maker(s) through the immediate experience of their senses; secondly, a material form that is the culmination of its making; and thirdly, the phenomenal forms perceived by the book’s readers. A book’s assembling is undertaken within a spectrum between haptic perception (involving all the senses) and optic perception (privileging a single sense), and can move back and forward along this spectrum.

Graham Sullivan (2010) points out that artists continually make informed choices about approaches to creative making, which are rarely predicated on the assumption of a single prescribed body of knowledge from which to draw. Practitioners who make letterpress-printed artists’ books understand that the artefact (of printed matter) produced is variable, based on the practitioner’s personal experience of presswork, paper folding, book binding, etc.—the use of type (or block), paper, pressure, ink(ing) and (atmospheric) conditions. “Thus whereas in the artisan’s12 handling of his tools, the movements of their working points are guided by his own perception, the motions of the machine, and any tools attached to it, are predetermined” (Ingold 2000). Experienced practitioners already share a mutually agreed notion of ‘handleability’, which is that, through our handling of technology, that we come to understand its being in a way that is impossible to predict or predetermine (Heidegger [1954] Heidegger and Lovitt 1977) Within the practice, that being knowledge (gained through the senses) of these variables (objects) and how to articulate them (both practically and verbally), Barbara Bolt (Barratt and Bolt 2010) developed Heidegger’s theory of ‘handleability’ to present an arts-related concept of ‘material thinking’.13 The individual is decentralised from the creative process by predicating the ideas of co-responsibility and indebtedness between people, materials, technology and methods of practice. In doing so, the focus also shifts from the artwork to the collaborative practice that sets the artwork on its way into existence (Barrett and Bolt 2010).

Bolt’s notion also has links with Tim Ingold’s (2013) approach to skill and technology in discussing tools, minds and machines with the practitioner becoming only a part of the artistic process, for example, within a practitioner–equipment–materials–printing press scenario of working. Ingold asserts that the work (as the result of the creative process) invites the viewer to perceive in tandem with the maker in aligning the viewer’s movements within the work itself. “To look with us as it unfolds into the world”, rather than the work originating from a set intention followed through to the final product, being able to access the practitioner’s creative ‘flow’14 of the work becoming itself through the relationships of people, movements, tools and machines that bring it into being.

To explain further, the typesetting process has its own system of measurement, not based on the metric system but derived from the imperial system.15 So, it is through the handling of these associated materials, tools and equipment (sorts, spacing, leading, press, paper, binding thread, bonefolder, etc.) that they can evolve with our responsiveness to them, rather than tools and technology just being a means to an end, evidencing that the practice and theory of making art are interconnected. These notions of handleability and material thinking provide phenomenologically embedded methods of reading artists’ books. Moreover, allied with practitioners’ presswork, use of tools, ideas, methods and innovations, the concepts form a new approach to understanding the letterpress process, contextualised within artist’s book practice and a definition of the artefact itself; i.e., the letterpress-printed artist’s book is a unique, multiple or editioned original work of art that relates to and/or interrogates the book form and/or narrative, being inextricably allied with its method and process of production and materiality in terms of content, concept, reading (visual and/or haptic), aesthetic and/or subject matter. Whilst this is a categorisation of a book, it is preferable to see it as a stimulating, multisensory experience through interaction.

6. Engagement with Contemporary Practice

Etching, lithography, wood engraving and screen printing are print processes that require the practitioner to bring (the first stage of) a print into being through direct bodily contact with the surface to be printed, etching, drawing, photographic exposure and transfer or engraving (a creative act) onto new (or re-ground and prepared) plates, screens and blocks (that are widely available from specialist suppliers in the UK). In the letterpress process, there is still a direct bodily connection through the process of typesetting, in setting up a form, although the materials (type) that are used pre-exist.

The practitioner relies on the type to encapsulate their voice rather than create it. There is a duty of care for anyone using metal type and/or wood letter to ensure that each sort is stored correctly in the type case, handled and printed sympathetically to guarantee the condition and longevity of these materials. A great amount of trust needs to exist if type is to be used on a shared basis, as it can be easily damaged or lost. Those involved must have a mutual understanding of good studio practice and confidence in each other to be able to work alongside each other in this way. Practitioners build close relationships with all the items held within their own working spaces as many have a particular provenance, and some have taken a long while to acquire. Nowadays, all paraphernalia associated with letterpress printing is valuable and some, irreplaceable.16 It is then logical that the letterpress process lends itself to practitioners working either in their own spaces or that shared spaces are within specialist areas, such as the London Centre for Book Arts,17 Figure 3. If type and equipment are available in general print studios, dedicated technical support is required to supervise studio practice and professional conduct concerning the preservation and use of any type collection.

Figure 3.

The London Centre for Book Arts: The studio was established in October 2012, becoming the first and only centre of its kind in the country. Photos courtesy of Ira Yonemura.

When contemporary practitioners set type, the working method and proportion of time that they give to this task is not akin to that of the commercial printer. (The practitioner does not have such a direct relationship with time equals money, etc., and the emphasis on engagement with materials is different). There is something valuable in what is gained from the complexity of the task and the amount of time taken over it, that the combination of task and time taken allows one to work within a slow18 framework. The complexity of typesetting requires a high level of engagement, so to get past the relative frustration of the task and its time-consuming nature, the practitioner needs to achieve a particular level of consciousness (to bring about creative flow). The body is hyper aware, in order to perceive the correct repetitive movements and responses to the composing stick and individual sorts. As Johanna Drucker (1984) explains,

The difficulty and challenge of typesetting is directly linked to the pace of the job. A complex task necessitates a high level of bodily connection between the practitioner, their tools and materials. For contemporary practitioners, there is a direct link between those who were hand-setting type in the 1960s and 1970s, although there is also a difference here. Foremost, those early practitioners wanted to print themselves, to have an uncensored voice and to put forward the book as a critical space for their work. Letterpress equipment was cheap, and type was still freely available. There was no other choice at that time to produce multiple copies of one’s own work without professional assistance. Through their physical interaction with presses and equipment they discovered that the letterpress process enabled a holistic approach to their practice, enhancing their work through the experience and materiality of their medium.Handsetting type quickly brings into focus the physical, tangible aspects of language–the size and weight of the letters in a literal sense–emphasising the material specificity of the printing medium.

Today’s practitioners make a conscious choice to engage with a practice that is highly involved, when they have many more options available to them through digital print, photocopying and other forms of reproduction. These practitioners make a conscious choice to enter into the particular type of commitment that printing letterpress demands, but their experiences are very similar.

7. Assessing Practice

Most practitioners, past and present, discuss letterpress printing as being “more than a process,” within making artists’ books and the small publishing practice. This is because the letterpress-printed artist’s book, card, pamphlet, etc. may include all the traditional factors—text, historical elements and design—but the intention of the artists’ bookmaker, press or publisher is different. The process was/is integral to their practice (i.e., the book form and/or narrative, being inextricably allied with its method of production and materiality) and, therefore, can be discussed as practice.19

The position on contemporary letterpress-printed artist’s books and artist-publishing is deemed as practice, because it forms the core of practitioners’ artistic activities, and they have a deep involvement with realising their work in book-related form. Although most practitioners voice this stance, they do not want it to be seen as exclusive, as they are conceptually led. As Andrew Morrison explains,

In discussing visual arts practice David Thomas (Thomas 2007 in Sullivan 2010), states that,Yes. You have to define what practice means, but it is essentially what I do. I do other things, it’s not exclusive, but it is my core practice. You have to have something that defines what you do.

Here, Thomas explains the complexities and intertwinement of physical and theoretical activity. Thomas describes “where private and public worlds meet”: this particularly resonates with artist-publishers, as their surroundings (which often contain their print workshops) and private and public aspects of their lives also form part of their practice. This is why particular elements of practice are difficult to separate, discuss and analyse succinctly, as there is always a crossover in method or activity (as expressed by Prytherch and Jerrard (2003) in a study where renowned highly skilled artists were interviewed with regard to day-to-day sensory engagement). Practice itself cannot be compartmentalised into completely separate parts, as there is so much leakage from one process to another. Practitioner Leonard McDermid reflects, regarding the development of practice,Such making is not just doing, but a complex informed physical, theoretical and intellectual activity where public and private worlds meet. Art practice is the outcome of intertwined objective, subjective, rational and intuitive processes.

McDermid evidences two methods for developing practice: one is innovation, by which one has the confidence to go forwards (based on the sum of one’s practical experiences and embodied knowledge); the other is improving technical proficiency through repetition and honing aspects of physical activities (craft skills) within a framework of creative practice. The possibilities for innovation in letterpress printing require an embodied knowledge of the process to be able to develop creative application.20Your points of departure come from experience and your skills come from time and patience.

Technical aptitude improves with the repetition of more formal aspects of the typesetting and printing process (that are related in printing manuals) but does not necessarily lead to innovative ideas and creativity. Practitioners know that they improve both technique and creative practice through time spent on the physical process of doing, in making their work. How this was evidenced (to the practitioner) was through comparing old and new work. Practitioner Philippa Wood clarifies,

The types of engagement that Wood references are “tacit knowing” and “bodily knowledge”, (rather than “reflection in-action”, see below), as the practitioner is engaged in creative flow (“subconsciously it happens”) rather than problem-solving strategies. The practitioner has an embodied knowledge of their studio practice.You are learning all the time when making your own books, without realising it—subconsciously it happens, if I look back on work that I printed [a while ago] than it becomes apparent, but you don’t realise it until you begin to compare previous work.

In the process of art making, some of this knowledge is tacit. Michael Polanyi believed that when we create, we use our sensory perception in order to process, understand and come to know something. This type of knowledge is not something that is necessarily learned explicitly, honed or memorised. It is participatory knowing from a performed experience, by indwelling, by being somewhere, doing something or being engaged in extended practice (Coughlan and Brydon-Miller 2014). Polanyi’s argument was that the informed guesses, hunches and imaginings that are part of exploratory acts are motivated by what he describes as ‘passions’ (Smith and Smith 2008) These acts formulate a deep personal sense of knowing, which he framed as ‘tacit-knowing’ (rather than knowledge) (Polanyi 1967).

Donald Schön’s theory of reflection-in-action can be applied to working with the letterpress process, as, by its nature, situations are thrown up that do not present themselves as givens but are constructed from events that are puzzling, troubling and uncertain. It is the recognition of emotional discomfort in response to professional experiences that defines the essence of reflectivity (Harvey et al. 1961). What is required of the letterpress/book art practitioner is the ability to realise in the moment of action, ‘to catch oneself’ in order to reflect as part of practice. In our fast society, this alternative method of working, being mindful, requires a period of adjustment to achieve a completely different mindset. By working in this way, the practitioner is not necessarily dependent on established theory and technique but constructs a new theory from each unique case (Schön 1983).

8. Concluding Thoughts

In reflection-in-action (encompassing slow principles), the practitioner becomes aware of their (own) influence on their practice and is critical of their work, that is, a reflexive practitioner. As stated by Thompson and Pascal (2012),

Therefore, the practice of keeping proof prints and artist proof (or edition) copies is substantiated through the reflexive process. The practitioner is engaged in praxis (theoretically reflective action), which implies a life practice informed by oneself, a heuristic practice through reflection and action; e.g., we provide ourselves with the tools that lead us to transformation. So, practitioners are enabled to evidence their transformed state through the critical comparison of their work. As practitioner Andrew Morrison confirms, “The natural process of view and evaluation, one gets better through doing”. Morrison references reflection-in-action as a strategy for overcoming particular problems encountered during the process. His position is that one needs to be physically engaged with the process (as opposed to reading, observing, etc.) to improve both artistic and technical capabilities. The reflective process requires a slow approach to enable dialogue and understanding between practitioner, process and press in order to move forwards. Andrew Morrison extends this point in relaying that,Reflexive practice is […] a form of practice that looks back on itself, that is premised on self-analysis in order to make sure that: (1) the professional knowledge base is being used to the full; (2) our actions are consistent with the professional value base; and (3) there are opportunities for learning and development being generated.

This suggests that the practitioner is reflective in their working practice, that is, from informed practice. Although with the particular problems that arise in the printing process (as mentioned above), the process never becomes mechanical (Sullivan 2010). It is often at this point that the practitioner could become frustrated and aware that time is progressing, so their decision-making is at risk of becoming rash and uncalculated. Through interview discussion and empirical study, it was generally agreed (among practitioners) that at this point the practitioner needed to make some space for reflection. This position is supported by David Clutterbuck (2003): “time to think deeply, in a focused way–is critical to effective working. […] Using time as an intelligent resource, rather than becoming a victim of it”.You realise after printing for two hours that what it needs [to solve the problem] is a little bit more make-ready or take a little bit of ink off. [After a period of time] you go back to that [same] job and it’s almost like starting again [from scratch] and it’s the glory and the frustration of it—you can put exactly the same amount of ink on and print with exactly the same amount of pressure, have the rollers in exactly the same position and there is a different result. Why is that? Atmospheric conditions, stiffness of the ink and so on, there are so many things that mitigate against it, but almost every time [you print something] it is like learning how to print.

A slow framework allows the type of reflection for thinking with the body, through movement, to articulate “material thinking” in how tools, equipment and materials are guided by our own perception and “handleability” of technology. In thinking through the process in a collaborative sense, we can see our movements within the work (and on the press) itself. As expressed within a phenomenological approach by Greg Piper (2007),

This is confirmed by practitioner Nancy Campbell, who observes when working with a printing press,The initial and developing idea for an artwork is itself a product of fluctuating influences, intentions, conceptual vagaries, emotional and needful urgings, and cultural conditionings. These are drawn into the making with an array of conditions of self and external referencing that get played-out as the work evolves and is resolved. The physical partnership (between maker and materials) of making empowers a shift from abstract (internal) to substantive (external), and there is a spatial, tactile connection between inner-self, hand and materials.

The relationship of the practitioner and the press is examined through practice-led research, which is simultaneously generative and reflective (Gray 1996). Whether practitioners are refining technical, craft skills or developing creative ideas on the press, the approach is the same, being through haptic enquiry. There needs to be a conscious understanding between the experience during practice and then (reflection on experiences and) implementing of the knowledge that is grown during the creative process, that is, through praxis. Knowledge of bodily experience through the use of the printing press is central to extend the practice of letterpress-printed artists’ books and develop new paradigms for this contemporary practice. In visual arts practice, by discussing how our creative actions impact our own lives and affect others, we can critically assess our own practice and its relationship to others to share meanings and contextualise knowledge.You have a connection, there is some control but it is also a partnership. It’s the same with any tool that you are familiar with that you are using it almost prosthetically and that’s when the best things happen.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Attwood, Martin. 1976. Artists’ Books, Booklets, Pamphlets, Catalogues, Periodicals, Anthologies and Magazines Almost All Published Since 1970, Selected for a Travelling Exhibition by the Arts Council of Great Britain. London: Arts Council. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, Estelle, and Barbara Bolt, eds. 2010. Practice as Research: Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry. London: I. B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Bevis, John, Simon Cutts, and Andrew Wilson. 2012. Printed in Norfolk: Coracle Publications 1989–2012. London: RGAP. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, David. 1981. Four Years at Coracle Press. London: Coracle Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carreiro, Linda. 2017. Working Against Type: Opening Gestures in Word-Based Visual Art. Ph.D. dissertation, Cardiff School of Art and Design, Cardiff Metropolitan University, Cardiff, Wales, UK. Available online: https://repository.cardiffmet.ac.uk/handle/10369/8784 (accessed on 9 August 2019).

- Carrión, Ulises. 1975. The New Art of Making Books in Artists Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook. Edited by Joan Lyons 1985. New York: Visual Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Paul. 2004. Material Thinking: The Theory and Practice of Creative Research. Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Clutterbuck, David. 2003. Managing the Work-Life Balance. London: Chartered Institute of Personnel & Development (CIPD). [Google Scholar]

- Coracle Press. 1986. The Artist Publisher: A Survey by Coracle Press. London: The Crafts Council (Great Britain). [Google Scholar]

- Coracle Press Gallery, Coracle Press, and the Yale Centre for British Art. 1989. The Coracle: Coracle Press Gallery, 1975–1987: An Exhibition at the Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut. 7 Nov 1989–14 Jan 1990. London: Coracle Distribution. [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan, David, and Mary Brydon-Miller. 2014. Encyclopedia of Action Research. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446294406 (accessed on 28 August 2019).

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. 2013. Creativity: The Psychology of Discovery and Invention. First Harper Perennial Modern Classics Edition. New York: Harper Perennial Modern Classics. [Google Scholar]

- Cutts, Simon, Colin Sackett, and Tony Hayward. 2000. RGAP, Plymouth Arts Centre, Coracle Press, John Dilnot Books, Folding Landscape (FIRM) and Inventory. In Repetivity; Platforms and Approaches for Publishing. Sheffield: Research Group For Artist’s Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, Timothy Michael. 2016. Towards A Fugitive Press: Materiality and the Printed Photograph in Artists’ Books. Ph.D. dissertation, MIRIAD, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, UK. Available online: http://e-space.mmu.ac.uk/617237/ (accessed on 9 August 2019).

- Drucker, Johanna. 1984. Letterpress Language: Typography as a Medium for the Visual Representation of Language. Leonardo 41: 66–74. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1574850?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents (accessed on 12 August 2019). [CrossRef]

- Ehrenberg, Felipe Mayor, David Marcel Alocco, Eric Andersen, Joseph Beuys, Ian Breakwell, George Brecht, Marc Chaimowicz, Giuseppe Chiari, Henri Chopin, Robin Crozier, and et al. 1972. Fluxshoe. Cullumpton: Beau Geste Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Carole. 1996. Inquiry Through Practice; developing appropriate research strategies. Paper presented at NO Guru, No Method? Paper presented at International Conference on Art and Design Research, UIAH, Helsinki, Finland, September 4–6; Available online: http://carolegray.net/Papers%20PDFs/ngnm.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Hair, Ross. 2017. Avant-Folk: Small Press Poetry Networks from 1950 to the Present. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Oscar Jewel, David E. Hunt, and Harold M. Schroder. 1961. Conceptual Systems and Personality Organisation. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin, and William Lovitt. 1977. The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, Martin, and Joan Stambaugh. 1996. Being and Time: A Translation of Sein Und Zeit. SUNY Series in Contemporary Continental Philosophy. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 2013. Making, Growing, Learning: Two Lectures Presented at UFMG, Belo Horizonte, October 2011. Educação Em Revista 29: 301–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, Joan, ed. 1985. Artists’ Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook. Distributed by G.M. Smith, Peregrine Smith Books. Rochester and Layton: Visual Studies Workshop Press. [Google Scholar]

- McLuhan, Marshall. 2010. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. London: Routledge. First published in 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Mosely, Tim. 2014. The Haptic Touch of Books by Artists. Ph.D. dissertation, Queensland College of Art, Arts, Education and Law, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia. Available online: https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au/handle/10072/367982 (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Noë, Alva. 2004. Action in Perception. MIT Press Paperback ed. Representation and Mind. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phillpot, Clive. 1972. Feedback, Monthly Column #2. In Studio International Journal of Modern Art Incorporating The Studio. no. 947. London: Michael Spens, vol. 184, p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Phillpot, Clive, ed. 2013. Booktrek: Selected Essays on Artists’ Books (1972–2010). Zurich: JRP Ringier. [Google Scholar]

- Piper, Greg. 2007. The Visible and Invisible in Making: Reflecting on a Personal Practice. Material Thinking, 09, Inside Making: Paper 03. Available online: https://www.materialthinking.org/sites/default/files/papers/SMT_V9_03_Greg_Piper.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2019).

- Polanyi, Michael. 1967. The Tacit Dimension. London: Routledge & K. Paul. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, Carl. 2004. The Bad Air Smelled of Roses. Letterpress Posters, Variable. Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, USA. Available online: http://www.clevelandart.org/art/2018.33 (accessed on 28 August 2019).

- Prytherch, David, and Bob Jerrard. 2003. Haptics, the Secret Senses: The Covert Nature of the Haptic in Creative Tacit Skills. Dublin: Trinity College, pp. 384–95. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/39c5/4b5bd4701b60f1562a9b9329af5c34c947f8.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Schön, Donald A. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Mark K., and Heather Smith. 2008. The Art of Helping Others: Being around, Being There, Being Wise. London: Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, Graeme. 2010. Art Practice as Research: Inquiry in Visual Arts, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Neil, and Jan Pascal. 2012. Developing Critically Reflective Practice. Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives 13: 311–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The quotes from practitioners that appear in this essay are taken from conversations, interviews and projects between 2013 and 2019. |

| 2 | Previously, practitioners who wanted to publish creatively were restricted to working with commercial presses alongside ideas of what was deemed ‘acceptable’ printing practice among British private presses who had a prejudicial attitude of what a book can or should be and the idea of particular skills needed to produce work in such medium. This made the bookmaking process a long and expensive project for the practitioner. |

| 3 | Such as Poor.Old.Tired. Horse (1962–1968), Wild Hawthorn Press, London; Tarasque magazine (1965–1971), Tarasque Press, Nottingham; and Schmuck magazine (1972–1976) Beau Geste Press, Cullumpton, Devon. |

| 4 | Publications from presses such as Moschatel Press, Coracle Press and Wild Hawthorn Press (1970s–1990s). |

| 5 | A recent history of the poetry network exists as an in-depth study that traces connections, publications, practitioners, communication, relationships and creative projects (Hair 2017): publications also exist that chart the development of Coracle (Brown 1981; Coracle Press 1986; Coracle Press Gallery et al. 1989; Cutts et al. 2000; Bevis et al. 2012) which due to the nature of their practice, in turn, aids research on the work of other practitioners that evidence use of the letterpress process. |

| 6 | Interview with Helen Douglas at Deuchar Mill, Yarrow on 16 November 2016. |

| 7 | The first press that Weproductions (artist-publisher since 1972) acquired was a letterpress (Vandercook No.4 cylinder proof press) in 1978/1979 (along with two full cabinets of type, spacing and other print room equipment, tools, etc.) collected free from Stevenson & Co. (Edinburgh, Scotland), a printing firm that was closing down (interview at Deuchar Mill 23 November 2016). |

| 8 | Conversation with Laurie Clark, Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh 17 February 2018. |

| 9 | Poiesis is etymologically derived from the ancient Greek term, “ποίησις”, which means “to make”. |

| 10 | A good impression: a clear and crisp imprint. |

| 11 | As part of a community of making where practice is shared collaboratively through working in spaces, conversations, actions and artefacts. |

| 12 | I am including the practitioner of letterpress-printed artists’ books in Ingold’s description of “artisan” because of the intrinsic use and knowledge of the machine (printing press) within the practice. |

| 13 | Barrett and Bolt (2010) are focused on the practitioner and materials rather than Carter’s (2004) notion of material thinking that privileged collaboration between practitioners. |

| 14 | A state of being completely immersed in an activity for its own sake (Csikszentmihalyi 2013). |

| 15 | The two units of measurement in typesetting are points and picas. In the UK, a point is equal to 1/72 inch. A pica contains 12 points (also called an em) and is equivalent to 1/6th of an inch. |

| 16 | Setting up one’s own space to print was an on-going process that could take years to find contacts and build a letterpress network to support the quest to source and build up a collection of suitable second-hand machinery, equipment, tools and knowledge of press maintenance, etc. Social media platforms, particularly twitter and Instagram, now support practitioners in a more direct and immediate sense, enabling the development of a network over a shorter period of time alongside established websites and traditional networks (such as societies, guilds, etc.). |

| 17 | The London Centre for Book Arts, based in what was once the heart of London’s print industry, the London Centre for Book Arts (LCBA), is an artist-run, open-access studio, offering education programmes for the community and affordable access to resources for artists and designers. The Centre’s mission is to foster and promote book arts and artist-led publishing in the UK through collaboration, education, distribution and by providing open-access to printing, binding and

publishing facilities. The unique facilities at LCBA are available to everyone regardless of background, education or experience. Available online: https://londonbookarts.org/ (accessed on 21 October 2019). |

| 18 | A slow theory approach values notions of time and intention with an emphasis on engagement with the hand, allowing time and integrity to be valued as central to the artistic process. This is vital in the execution of processes that constitute letterpress printing and book art practice. Similarly, the printing press can be seen as a slow technology—one that allows the practitioner time for reflection. This means that there is a continued a dialogue (between practitioner and press) as an integral component of the creative process. |

| 19 | Although letterpress printing is/has been at the core of practice for the majority of practitioners, they do not use the process only because it is available to them. When it has not been accessible, these practitioners have found other ways of working and processes to use in order to express themselves. If a concept requires that other processes are required in addition to, or instead of, printing letterpress, they will have no reservations about forging ahead to use them or producing work in another form, such as installation rather than book, etc. However, it is important to reiterate that practitioners have made a commitment to making letterpress-printed artists’ books and book-related work, as they find the form fitting for most ideas and some have a passion to explore the book form as creative practice. This type of practice requires total immersion of oneself within the making process. |

| 20 | Practitioner Elizabeth Willow discussed the fact that in her studio practice, proofs that had “gone wrong” were kept as a reminder of a particular point in a process where the work could change direction and become something else—to innovate (October 2016, Liverpool). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).