Abstract

A network of Indigenous art and culture centres across Australia play a significant role in promoting cross-cultural understanding. These centres represent specific Indigenous cultures of the local country, and help sustain local Indigenous languages, traditional knowledge, storytelling and other customs, as well as visual arts. They are the principle point of contact for information about the art, and broker the need to sustain cultural heritage at the same time as supporting new generations of cultural expression. This interview with Dr Valerie Keenan, Manager of Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre in northern Australia, provides rare insight into the strategies, challenges, and aspirations of Indigenous art centres and how the reception of the art impacts on artists themselves. It provides a first-hand account of how Indigenous artists strive to generate a new understanding of their culture and how they participate in a global world.

1. Introduction

If we were to ask ourselves why art matters today, perhaps the most common response resonates around how art helps us to better understand one another. Language barriers often impede cross-cultural dialogue but visual art tends to work on a more inclusive, flexible, and symbolic level where emotions and sensory intelligence help channel communication. Art, exhibitions, and all kinds of art engagement and participation, potentially offer both personal and shared opportunities to rethink our own place in the world, and our relationships with others. We learn through art how people perceive themselves through expressions of cultural identity and a sense of belonging to homelands (Leuthold 2011; Butler 2017). Art’s appeal for a new understanding is a growing phenomenon occurring around the world. In the USA, large-scale exhibitions like Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now, shown at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas, explicitly target this challenge (Besaw 2018). The Museum itself opened in 2011 with a vision of ‘transforming lives through art experiences’ (Bigelow 2018), and is a major educational and cultural tourism initiative that ‘celebrates the American spirit in a setting that unites the power of art with the beauty of nature’.1 Indeed, Crystal Bridges profiles itself as a participatory experience of art in a particular natural setting:

Crystal Bridges takes its name from a nearby natural spring and the bridge construction incorporated in the building, designed by world-renowned architect Moshe Safdie. A series of pavilions nestled around two spring-fed ponds house galleries, meeting and classroom spaces, and a large, glass-enclosed gathering hall. Guest amenities include a restaurant on a glass-enclosed bridge overlooking the ponds, a Museum Store designed by architect Marlon Blackwell, and a library featuring more than 50,000 volumes of art reference material. Sculpture and walking trails link the Museum’s 120-acre park to downtown Bentonville, Arkansas.(Bigelow 2018, p. ix)

Large art institutions like Crystal Bridges are steeped in the context of art, but require significant investment of government, corporate, and philanthropic funding. However, we should not discount the visitor interface of smaller community art initiatives. Australia’s extensive network of community Indigenous art and cultural centres also encourage visitors to experience art in a specific context of people and place (Wright 1999). They serve as the external profile of small Indigenous communities, and help educate visitors about a wide range of beliefs and customs informing the art, as well as an intimate knowledge of the land (Langton et al. 2018). The art centre network spans across Australia, with many located in remote regions of some of the world’s most precious and unique environments.

The following interview is a rare opportunity for insight about some of the strategies, challenges and aspirations in how art centres mediate cross-cultural understanding. As the hub of most regional art production, Australian Indigenous art centres provide artists with studios, materials, workshops, market representation and advice, curatorial services, framing, freight, and much more (Wright 1999). They also play a vital role in supporting a wide range of cultural practices beyond the visual arts, and various community services deemed appropriate by the artists. These art and cultural centres are usually open to the public and have galleries with art and cultural heritage material on display along with art for sale ranging from the inexpensive to pieces that attract the high end of art market prices in Australian metropolitan and international galleries. Public access to relevant art centres offers an important touchstone for cultural tourism in regional Australia, however they are often ignored or forgotten by mainstream tourism providers and regional councils in their tourism itineraries and marketing campaigns.

Dr. Valerie Keenan is the Manager of Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre2 in Australia’s north-eastern tropical region. The art centre is an initiative of the administrative organization Girringun Aboriginal Corporation which began operations in 1996. Initiated by a group of Aboriginal Elders, the organisation has a full Aboriginal board of directors and a staff of over 30 Indigenous people. It is one of the largest employers in the township of Cardwell where it is based. The art centre was established as a full-time business in 2008 following receipt of funding from the federal and state governments. Traditional homelands of Girringun’s artists include spectacular landscapes incorporating vast areas of pristine rainforest canopy and wet/dry sclerophyll forests bordering the coast and sections of the Great Barrier Reef (Figure 1). Girringun’s Education Resource for their Manggan gather/gathers/gathering touring exhibition describes an environment that is much loved by the Traditional Owners, but also of great appeal for tourists:

Artists draw on this spectacular country and its Aboriginal custodianship to forge careers achieving local, national and international reputations for unique contemporary expression of past and present cultural life and traditions.Reaching upwards out of the lush rainforest are impressive mountain ranges and stunning rock formations. The region features countless rivers, streams, waterfalls, gorges and dense wetlands with mangrove eco systems and well-watered open savannah plains in the rainforest shadow of the Great Dividing Range.(Reeves and Higgins 2018)

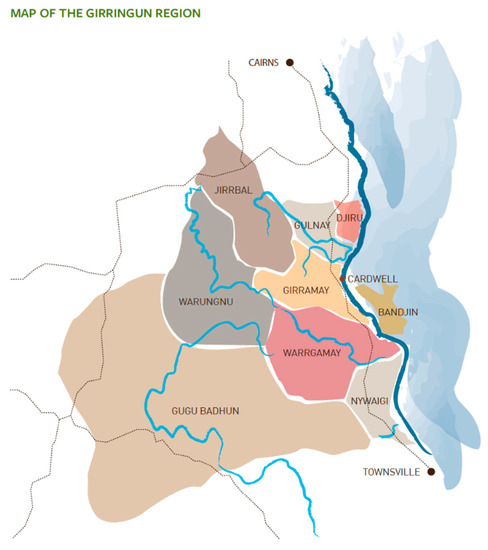

Figure 1.

Map of Girringun Traditional Homelands on the north eastern Australian coastline, showing the nine language groups that constitute Girringun’s Traditional Homelands (Reeves and Higgins 2018). Reproduction courtesy of Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre.

2. Interview

Sally Butler (SB)

Doctor Keenan, from your eleven years of experience as the Art Centre Manager of Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre, you are in a unique position to understand aspects of both the production and reception of Aboriginal art by Australian and non-Australian audiences. This is an excellent vantage point for observing how differing cultural perspectives intersect, and possibly collide, when people communicate with another through art. In this interview, I would like to explore some ideas about what works, and what needs improvement, during the exchange of art in a cross-cultural context from the specific perspective of an Art Centre Manager.

Can you summarise some of your general observations about what brings visitors to the Art Centre? Are visitors generally interested in learning more about the art and culture, or is it principally about purchasing an item for various reasons?

Valerie Keenan (VK)

In the majority of cases visitors come to us to learn about Aboriginal culture and are in most cases astounded by what they see. They appreciate how little knowledge there is available in the public realm. We have a small museum which, while compact, has a selection of rainforest tools and objects with explanatory texts illustrating elements of cultural life and usage. We find that people are mostly surprised by the complexity of what they see and often struggle to understand. Our art gallery, which contains artwork for sale, is attached to the museum and visitors are able to purchase artworks ranging across paintings, prints, weavings, sculpture, books, jewellery and merchandise. We find most visitors are looking for something small as they are travelling and space is a factor.

Apart from our limited promotional budget, a fundamental gap in bringing visitors to the art centre is how the various tourism bodies and local government promote and direct visitors to us. The latest tourism map of Cardwell produced locally does not include Girringun as a site to visit at all. We try to enhance our visibility in various ways that include public art installations like the one at the Cairns Performing Arts Centre (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Example of unique Girringun art sculptures transformed into public art at Cairns Performing Arts Centre, installed 2018. Artists right to left Debra Murray and Emily Murray; Clarence Kinjun; Eileen Tep and Melanie Muriata; Sally Murray and John Murray; Philip Denham and Nephi Denham. Photography courtesy of Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre.

SB

Do you think that Girringun, and art centres in general, are well equipped to cater for opportunities to promote learning and cross-cultural understanding to visitors? If so, in what ways? If not, what are the key impediments?

VK

In my opinion it is best if Indigenous people tell their own stories and we have been working towards increasing our capacity to do that. Two of our arts workers are Traditional Owners and are particularly knowledgeable about their own culture. Knowing their subject and gaining the confidence to talk about it has been key to making this happen. Increased confidence means that they are able to relax and include personal perspectives so that audiences at exhibitions, workshops and visitors to the centre have a deeper engagement.

Members of our other program areas are also stepping up to become future leaders. In my view supporting people to move forward begins by understanding that the value of cultural heritage is incalculable. Traditional culture from each local area needs to be visible in schools and everywhere our daily lives take us; at the very basic level of mainstream learning. Appropriate education of educators and Traditional Owner engagement is necessary to make this happen.

SB

What do you consider to be key aspects of the art that conveys the contemporary experience of Aboriginal cultures?

VK

I don’t really think that people sufficiently consider the impact of their response to art for the artists. This is more than a commercial transaction. It is about sharing cultures and ideas. Contemporary art practice allows an artist to give a visual voice to things that happen in their lives. They don’t have many other avenues for this in the public realm. It can help build personal esteem and confidence. In fact, the public response to art can change an artist’s life. It can be a factor in opening doors for other opportunities such as travel and higher education and so much more.

The perception that Aboriginal art is just about dot painting is still a persistent stereotype. We do have visitors who come in looking for ‘aboriginal’ art and who get upset when we don’t have ‘dot’ paintings to sell. Rainforest pattern making and design is quite different to other parts of Australia. It is a unique cultural heritage that pertains to a very different climate, geography, and set of cultural traditions to that of dot paintings’ Central Australia’s desert region. Cardwell is approximately 2000 kilometres from the heart of the Central Desert region at Alice Springs. Why would anyone think that no cultural change exists over that enormous distance? A tropical coastal climate requires a very different lifestyle to that of the desert, and cultural traditions are the framework of that lifestyle. Artists from Girringun have a unique cultural heritage that is sustained in part by the art produced by artists today. It has to be nurtured and appreciated to help keep this cultural heritage strong.

There is also the obvious element that art sales provide an income stream for people living in regional areas where employment prospects are often low. This income helps people to live on their traditional homelands and care for it through cultural practices that are all about respect and love for the environment, and for the people who live there.

SB

What techniques and strategies are most successful in breaking down stereotypes about Aboriginal cultures and traditions?

VK

The answer to that question is education, education, education! At all levels. We need to get more opportunities for people to learn about the different Aboriginal cultures and how they participate in contemporary life. This is needed in the public realm as well as art circles. I am talking about in schools, on the television, in newspapers and social media, and in markets and festivals. Art exhibitions are important, but we also need more books, documentaries and places where art brings people together at art fairs, artist residencies, cultural camps, and anything involving a safe space for lots of talking and sharing. We need to find ways to enable cross-cultural interactions so that it is more part of our normal life rather than an occasional unusual experience.

I also think that we need a broader front of advocacy for supporting the full diversity of contemporary Aboriginal art and what it means for the world’s cultural heritage. This advocacy particularly involves appeals to politicians to understand more about their own constituents and that by buying a piece of art they can show their support in a very practical way. Politicians have the capacity to inspire people to support the arts of their own constituents, and others.

We need a groundswell of education driven by sheer stubbornness and willpower.

SB

Can you say something further about how the art produced today contributes to Aboriginal cultural heritage?

VK

Traditionally the telling of stories was predominately physical and oral processes (dance, song, voice), but there were also stories painted on rock and on objects. What is being done now is an extension of what has happened in the past with the introduction of new materials and ways of working. Artists are exploring new mediums such as ceramics, photography, and video, to continue the tradition of storytelling and to include a wider global audience.

There is still a very strong sense of community with the way art is produced at our art centre. While art may be a physical outcome, it is the camaraderie and sharing of food and laughter that we look forward to. This is a place where language can be, and is, spoken. There is so much more that goes into the production of art, than can be seen in the tangible outcome. With more education, we hope for a better understanding of this context of what the art means to the artists and their communities beyond producing objects for sale.

SB

What do you consider to be the most globally relevant aspects of art produced by Girringun’s artists?

VK

The artists have a number of unique attributes that contribute to work they create which comes out of a tradition of living that spans tens of thousands of years. Their cultural stories have been passed down through generations and still have relevance in the community and landscape today. This knowledge from the past is important for everyone. We all require more awareness about the diversity of backgrounds who now today are interacting with one another much more than before.

The art that Girringun artists produce is, and always has been, influenced by the rainforest environment in which they continue to live. Rainforests are a precious aspect of our global ecology and no-one understands them in quite the same way as the traditional owners. There is an awareness of how all things work together, and how every aspect is of value. This kind of holistic knowledge requires generations and hundreds, if not thousands, of years to develop.

SB

Girringun has been involved in a number of exhibitions domestically and internationally where artists and yourself are involved in delivering public programs. Can you say something about the value of these exhibitions and programs?

VK

We find that many exhibition viewers have an awakening experience. What they experience is often so different from anything else that they have witnessed before. This is made more profound when the artists or cultural leaders are present, talking about their work and what it is that drives them and their inspirations and aspirations. Exhibition outcomes would be greatly improved if the original budget included sufficient funds to bring a number of artists and cultural leaders to the opening and subsequent events, so that the memory of visiting the exhibition is enlivened by this interaction.

SB

Girringun is involved in the Fake Art Harms Culture campaign. Why is this so important to the Aboriginal art industry, and to the artists themselves?

VK

The Fake Art Harms Culture campaign3 creates awareness about the growing production of fake art that copies the designs and cultural imagery of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures. The campaign also lobbies the Australian Government to do more about protecting Australia’s Indigenous cultures by addressing this fake art market. There has been a large marketplace in tourism centres such as Cairns that have ridden on the back of Indigenous culture, but have not had the right to do so. This subsequently provides little or no impact on the lives or economic return of Indigenous people. Not only has the majority of work that has been presented been produced overseas with nil economic benefit locally, but it also presents a false image of what Indigenous cultures really are.

SB

What do you consider to be the key potential benefits and limitations of developing cultural tourism initiatives in Indigenous art centres?

VK

In general, I don’t believe that Indigenous Arts Centres should be the centre of cultural tourism initiatives but part of a larger network of tourism businesses. Although, some art centres may be forced to act in this role by the nature of their isolation. Art Centres could certainly provide a point of contact and even a point of sale for smaller tourism businesses but there are already Traditional Owners who are working independently without the support of ATSI corporations such as Girringun.

SB

Is there anything you would like to raise yourself about the perspectives of an art manager, or about the role of an art manager, with regards to cultural tourism initiatives?

VK

In my experience the ‘tourist industry’ has paid a lot of lip service to including Indigenous content into their programs but have not understood that the best kind of engagement is through consultation and that consultation takes time and respect. Time is required to sit down with Traditional Owners on country and get an understanding of issues that slow down engagement. Time to understand that it is not always easy to find the correct person or people to talk to—and that these people may not be in a position to make decisions right away because of other pressures that are occurring. It also takes money. So any successful engagement between art centres and tourism requires a considerable investment of time, money and mutual respect.

An art centre manager may be able to assist with the business end of the discussions but more powerful outcomes will arise when broader engagement occurs and cultural protocols are observed.

SB

Thank you very much for your time Valerie.

3. Fake Art Harms Culture and Cultural Tourism

As Dr. Keenan mentions in the above interview, Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre participates in Australia’s national Fake Art Harms Culture campaign. As this article principally relates to how art creates new understanding in the context of cultural tourism, it is important to reflect on this campaign in some detail. The campaign was launched in 2016 by three key bodies involved in protecting the integrity of the Australian Indigenous art market. These are the Arts Law Centre of Australia4, the Indigenous Art Code5, and Copyright Australia|Viscopy6. The campaign addresses the problem of how an extensive volume of apparently Indigenous arts and craft do not involve Indigenous people at all. In many cases, the items are not even made in Australia. Indigenous art is used in this context as a generic Australian branding without any knowledge of what particular symbols and designs mean, and without any contact with the people who do know.

Australia’s Indigenous people established extensive cultural protocols and customary law about the ownership, replication, and distribution of visual traditions over a history of in excess of 40,000 years (Morphy 1991). This is because the visual imagery plays an amplified role in oral cultures where collective memory is transmitted through means other than the written word. The visual designs are integrated visual forms that trigger traditional stories, names, and events, that establish who has the rights to particular land, hunting, and all kinds of spiritual and human relationships (Biddle 1996). Clan members are responsible for the integrity of these designs relative to customary law and knowledge, and failure to maintain satisfactory standards of representation and interpretation are seen as a lack of respect for ancestors and the modern clan community. Banduk Marika, one of Australia’s leading Indigenous artists, explains the issue in the following way:

The ecosystem, the environment we live in is full of natural resources. Our art is our resource, it belongs to us, we use it in a ceremonial context; it is a resource for our survival. If control of that resource is taken away from us, we cannot meet our cultural obligations; we cannot use it for our families’ benefit. Exploiting our resource needs to be negotiated on our terms, we need to have control of how that’s done.(Marika 2017)

It is important to understand that it is not a matter of whether traditional designs appear on canvas, t-shirts, or water bottles. The issue is who is overseeing the use of replication of the imagery and whether they have rights to do so. Each time a design is used in the production of arts and crafts, it becomes an act of interpretation where relative community members share in discussion about whether the ancestral inheritance is respected, and how new iterations represent the sustainability of inherited knowledge. In this manner, even a printed t-shirt becomes part of a living history negotiating its way in the 21st century.

Items that appropriate this imagery, and this cultural inheritance, potentially distort and dilute the whole communal process of shared knowledge and creativity. Fake art robs indigenous communities of a financial income, but it is also potentially robs future generations of Indigenous people of a cultural inheritance. This is why the Australian Government’s House of Representatives Standing Committee launched a 2017 inquiry into an estimated 80% of stores selling fake Indigenous arts and craft (Parliament of Australia 2018).

Attention to the creative origins of Indigenous arts and craft should be part of the tourism experience in Australia. Avoiding fake art not only supports sustainable Indigenous cultures, but the awareness of origins also educates people in a greater understanding of the many different Indigenous cultures in Australia. This is why art centres are so important in their role as the ‘go to’ place to learn about the art and support the world’s most enduring cultural traditions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the collaboration and support of Valerie Keenan and the the artists and administration staff of Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Besaw, Mindy N. 2018. Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now. Fayetteville Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biddle, Jennifer. 1996. When not writing is writing. Australian Aboriginal Studies 1: 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow, Rod. 2018. Directors Foreword. In Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now. Edited by Mindy N. Besaw. Fayetteville Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press, p. ix. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Sally. 2017. Temporary Belonging: Indigenous cultural tourism and community art centres. In Performing Cultural Tourism: Communities, Tourists and Creatives Practices. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Langton, Marcia, Nina Fitzgerald, and Amber-Rose Atkinson. 2018. Welcome to Country: A Travel Guide to Indigenous Australia. Richmond: Hardie Grant Travel. [Google Scholar]

- Leuthold, Steven. 2011. Cross-Cultural Issues in Art Frames for Understanding. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Marika, Banduk. 2017. Fake Art Harms Culture. Available online: https://indigenousartcode.org/fake-art-harms-culture/ (accessed on 25 May 2019).

- Morphy, Howard. 1991. Ancestral Connections: Art and an Aboriginal System of Knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parliament of Australia. 2018. Report on the Impact of Inauthentic art and Craft in the Style of First Nations Peoples. Available online: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House/Indigenous_Affairs/The_growing_presence_of_inauthentic_Aboriginal_and_Torres_Strait_Islander_style_art_and_craft/Report (accessed on 14 May 2019).

- Reeves, Kerry-Anne, and Andrea Higgins, eds. 2018. Manggan Gather/Gathers/Gathering Education Resource. Cardwell, Brisbane and Adelaide: Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre, South Australia Museum and Museums and Gallery Services Queensland, p. 13. Available online: http://www.magsq.com.au/_dbase_upl/Manggan_Education_Resources.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2019).

- Wright, Felicity. 1999. The Arts & Craft Centre Story. Volume One: Report. Canberra: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Crystal Bridges Museum of American. https://crystalbridges.org/about/. |

| 2 | Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre Webpage. http://art.girringun.com.au/. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).