Abstract

This paper explores how the appeal of the imagery of the Arnhem Land bark painting and its powerful connection to land provided critical, though subtle messaging, during the post-war Australian government’s tourism promotions in the USA.

Keywords:

Aboriginal art; bark painting; Smithsonian; Baldwin Spencer; Tony Tuckson; Charles Mountford; ANTA To post-war tourist audiences in the USA, the imagery of Australian Aboriginal culture and, within this, the Arnhem Land bark painting was a subtle but persistent current in tourism promotions, which established the identity and destination appeal of Australia. This paper investigates how the Australian Government attempted to increase American tourism in Australia during the post-war period, until the early 1970s, by drawing on the appeal of the Aboriginal art imagery. This is set against a background that explores the political agendas "of the nation, with regards to developing tourism policies and its geopolitical interests with regards to the region, and its alliance with the US.

One thread of this paper will review how Aboriginal art was used in Australian tourist designs, which were applied to the items used to market Australia in the US. Another will explore the early history of developing an Aboriginal art industry, which was based on the Arnhem Land bark painting, and this will set a context for understanding the medium and its deep interconnectedness to the land. The latter thread contains the most important messages about Aboriginal art that were promoted within the texts of the exhibitions of the medium, accompanying exhibitions that were toured in the United States.

This messaging was in support of the view that, while Aboriginal imagery was being used to promote Australia in general, its role as was not to identify any Aboriginal ‘place’ as such, but rather to give a view of a culture deeply connected to the land. Destination tourism from abroad for Aboriginal cultural experiences, was in its infancy at this time, as the infrastructure for conducting tourism in the north was yet to be developed.1 Instead, the artwork was largely presented as representing Australia or the Arnhem Land, in a general sense, as a place to visit. Knowledge on Aboriginal culture that was used at this time consisted of ideas that were developed and expressed by anthropologists working in the field, in the early years, in Australia.

In this paper, while the terms, ‘travel and tourism,’ are used in the sense that tourism is a subset of travel, ‘travel’ involves going from one place to another, whereas ‘tourism’ can be considered more of a temporary stay away from home, with its primary purpose being something other than earning money in the place or places visited (Richardson 1999, p. xiv).2

Visual arts and culture, along with new landscapes and lifestyle attractions, have long been drawcards for the ‘tourist’, and no more so than for American tourists in Australia, during the post-war decades. Reflecting these trends, in 1936, an international travel brochure, entitled Australia, published by Australia’s inaugural organization, which was set up to promote travel to Australia, the Australian National Travel Association (ANTA 1936) (Figure 1),3

Figure 1.

Advertising poster, ‘Australia’, colour, lithograph, paper, designed by Gert Sellheim for the Australian National Travel Association, printed by Litho, McLaren & Co., 1956–1957. Image courtesy Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney © Joseph Lebovic.

while presenting no statistics on visitor arrivals in the country, introduced Australia in terms of its settlement history, wool industry, unique fauna, landscapes, and Aboriginal people. It featured images of all of these, including a full-page image of a naked tribesman with a shield and spear, titled ‘Primitive Aborigines Still Roam the Interior’. Exposure to Australia increased in 1938, when, in commemorating Australia’s 150th anniversary, an international publicity campaign funded by the ANTA, promoted Australia through lectures, radio broadcasts, and advertorials, in major newspapers and magazines (Holmes 1938).

Reflecting the growing interest in Australia as a destination, and in the absence of systematic records, from the early years, on visitor arrivals from the ANTA (it was a fledgling organization, set up by independent business owners and was reliant on occasional Government grants), data compiled by the ANTA indicated, in a report from 1954, that from 1945 to 1954, visitors to Australia from overseas doubled, from around 24,000 to 48,000 (ANTA 1954). In a news bulletin for the North American offices of ANTA in October 1962, it was indicated that, for the US market, the number of visas issued to Americans were up 20% in the 1950s (ANTA 1962). In 1965, there were 27,675 visitors from the USA, and in 1970, 64,281 (Australian Tourist Commission 1971, p. 9). Of these visitors, those coming to Australia for holiday purposes in 1970 had more than doubled from the previous five years (Australian Tourist Commission 1971, p. 11). In 1971, the end date considered for this paper, visitors from the USA had reached 83,000, an increase of nearly 30% over the previous five years, and of these, 69.1% had come for a holiday (Australian Tourist Commission 1972, p. 9). Among the holiday visitors were those who sought Aboriginal cultural experiences outside the cities and those who arrived for business reasons, and a certain number sought cultural experiences, which included visits to art galleries and museums where Aboriginal art could be viewed (Carroll et al. 1991, p. 13).

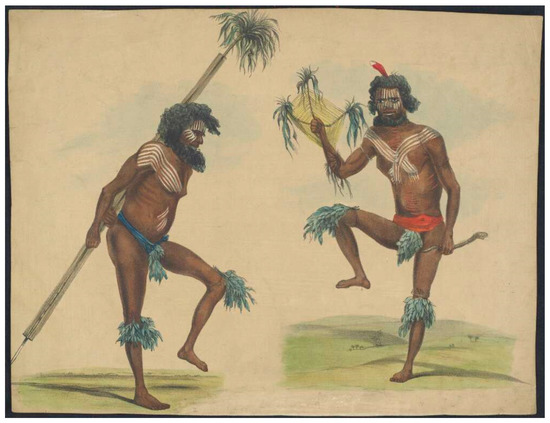

As mentioned earlier, Aboriginal cultural tourism was not actively promoted in overseas destinations such as the US, in the early years. This indicates that the Aboriginal people from the earliest times took a very proactive role in ‘tourism’, particularly with regards to preserving their culture within the context of colonized people living in the assimilation era. From the first contact with Europeans in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Aboriginal people were enterprising, capitalizing on the outsider’s interest in the ‘primitive’ or exotic nature of their cultural productions. They engaged in trade or performance for payment, activities that were part of survival strategies, which they used to build new futures and respect for their cultural inheritance (Parsons 1997, 2002; Birch 2010; Lydon 2002; Nugent 2005) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

B. Waterhouse Hawkins (lithographer), George French Angus, (illustrator), T. McLean publisher, Portraits of the Aboriginal inhabitants and their various dances, 1847 lithograph, 53.2 cm × 35.8 cm, image courtesy National Library of Australia Canberra. nla.obj-135637177-14.

Trading objects was a routine engagement. This occurred in South-Eastern Australia, where advances in transport facilitated ready access for recreational visitors from nearby cities to the places where Aboriginal people lived. Missions and reserves, such as Coranderrk and Lake Tyres in Victoria, and La Perouse in Sydney, were among the destinations involved. In the Arnhem Land, sites for visitation were usually the missions where bark paintings and tribal artefacts were produced for sale to visitors (Kleinert 2012, pp. 86–103).5 Other activities as precursors to contemporary forms of tourism, consisted of taking tours where European explorers, sojourners, and other travelers were guided through Aboriginal territories, with locals acting as interpreters, which were called ‘diplomacy festivals,’ such as at Tanderrum in Victoria, in which strangers were given the ‘freedom of the bush’. Within the category of ‘event tourism’, non-local people were invited to attend annual food harvest festivals, such as eeling and emu-hunting, while ‘sports tourism’ visitors were introduced to the Aboriginal skills in boomerang-throwing, wrestling, and playing cricket (Clark and Larrieu 1998, p. 5).

From the perspective of the Commonwealth Government, the history of building American tourism in Australia revealed a complex interplay of influences. From its inception, in the early twentieth century, the government provided no national strategy and only limited guidelines for tourism development.6 This situation had its origins in the overlapping responsibilities of the states and the Commonwealth, with regard to tourism, and a commitment by these parties to the policies of ‘let the market rule’ (Carroll et al. 1991, p. 22).

Notable among the early agencies to help determine the nation’s cultural brand was the Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics, established in 1905 (Richardson 1999, p. 78), and the Australian National Travel Association (ANTA),7 which was set up in 1929. The ANTA proved to be the significant force in advancing Australian interests in the international tourist markets of the English-speaking world. While constructing a new identity for Australia, it initially reinforced derogatory and romantic stereotypes of Aboriginal people, painting them as ‘savages’, ‘primitive’, and Stone-Age’, but by 1931, it was implementing a new direction, inspired by the US’s approaches to the branding of their Native American peoples—mythologizing and exoticizing them. For example, on the cover of Walkabout magazine’s inaugural issue in November 1934, this national illustrated travel magazine, which combined cultural, geographic, and scientific content with travel literature, from 1934–1974, featured the famous photographer E.O. Hope’s powerful portrait of a seemingly ferocious Aboriginal man from the Palm Island (Barnes 2010, pp. 120–21).8 Another ANTA initiative in a similar tribal vein occurred in 1950, where a portrait of ‘old Tjungurrayi’ was featured on an Australian postage stamp, ‘which led to the worldwide dissemination of ninety-nine million portraits and made Tjungurrayi into an icon of Australian Aboriginality’ (Barnes 2010, p. 133)

The ANTA opened offices in San Francisco in 1930, with the result that, in 1935, approximately 23,000 visitors came to Australia (Hall 1961, p. 78). Critically, the ANTA successfully pressed for change by commissioning research. Their Harris Kerr Forster and Co. Australia’s Travel and Tourist Industry Report of 1965 drew attention to the importance of the indigenous sector as an important tourism product and identified the great potential for cultural tourism (Craik 2001, p. 91; Harris Kerr Forster and Co. 1966).9 This latter recommendation led to the establishment of the internationally-focused Australian Tourist Commission (ATC) in 1967 (Richardson 1999, p. 286), which was the generic promotional body for Australian tourism.10 The advent of the Labor government in 1972 proved decisive in marking the beginning of a commitment to a national tourism strategy, with the setting up of a Department of Tourism and Recreation. Successive governments failed to capitalize on this and instead left tourism development to the private sector for several decades to come (Carroll et al. 1991, p. 22).11

Other factors that progressed tourist agendas in the pre-war years and opened the nation to the world, were the advances in technology (trains, cars and aeroplanes, printing, etc.), which made global travel possible for ordinary people (Richardson 1999, p. xv). However, within the changing dynamics of the world order created by this, insistent demands for national security, surfaced for Australia. Underpinning the US soft power cultural initiatives to take control of the India-Pacific region were agendas to encourage trans-Pacific ties, by promoting their influence in countries like Australia. A key protagonist within these strategies was the US-funded Carnegie Corporation. The organization took an active cultural and educational role, from the thirties onwards, among English-speaking colonies, like Canada, South Africa, New Zealand, and Australia. For example, they sponsored American economic journalist C. Hartley Grattan to write a popular book, titled Introducing Australia (1942).12

From 1936 to 1937, the Carnegie’s first travelling exhibition, which toured Australia’s state capitals and seven major centers in New Zealand, was titled the Exhibition of Contemporary Canadian Painting, an initiative of the Corporation’s president, Fredrick P. Keppel (died in 1943). It was conceived as a cultural and educational exchange that would bring countries in the Anglo-world, closer together. Importantly for US–Australia relations, its success spurred the Association, which had been established by the Corporation in 1936, to approach Keppel to tour a joint Australia–New Zealand exhibition, within the US, an enterprise that came to nothing. However, its failure nonetheless sowed the seeds for the Art of Australia 1788–1941 (to be discussed later), which was jointly sponsored by the Australian Government, ‘because it would promote better relations between English-speaking races’. This pronouncement reflected the Australian government’s desire to persuade the US to give up its isolationism and enter the war.13

From the 1940s to the 1950s, the issue that was most prescient for Australia was the nation’s security, in a period when the British, its traditional ally and dominant partner in military affairs, was losing power and influence in the region. The solution came when Australia joined the US and New Zealand in 1951 in forming the ANZUS Treaty. ANZUS was a strategic military alliance between the three nations, where Australians were of the view that this would provide security for Australia through US military aid and protection, in the conflicts of the post-war order.

Playing into these political moves of Australia, at that time, was Australia’s resentment towards Britain for obstructing their interests (McLean 2006, pp. 64–79). Within Australia, there had been long-standing ambitions of successive political leaders to draw the US into Australia’s defense, so as to provide a platform for the country to have a more prominent role in the power relationships of the Pacific region. In the changing circumstances that were to follow over the next few decades, involving the decline of Britain and the ascendancy of America, Australian leaders came to depend increasingly on Washington, for its security (McLean 2006, pp. 64–79).

Other influential currents at this time, which would define Australia’s emergent national identity within tropes that would acknowledge Aboriginal culture, were those drawn from the perspectives of its emergent intelligentsia. Advocates of Aboriginalism included Margaret Preston, Fred McCarthy, A.P. Elkin, P.R. Stevenson, Xavier Herbert, Patrick White, A.D. Hope, John Thomson, Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker, Arthur Boyd, and Jon Molvig (Geissler 2017, pp. 79, 80–85, 93–94, 104–5; McLean 1998, p. 95), producing both images and narratives that represented the ‘imagined communities’ of the nation. Essentially, such content represented these ‘global cultural flows,’ consisting of a complex repertoire of images and narratives, which anthropologist, Arjun Appadurai, calls mediascapes (the transfer of images) and ideascopes (the progress of ideologies) (Appadurai 1996, p. 33). Such highly opinionated Australian voices as those mentioned, were critical within this era of rapid technological advancement, where international dispersal and uptake of information reflected ‘the desire for connection, to match something in themselves to another place and to other peoples’ (Appadurai 1996, p. 33; White and Frew 2011, p. 3).

Modes of communications deployed by Government agencies to transmit their carefully curated promotional images and narratives of national identity, included print, press, and national ceremony (White and Frew 2011, p. 6; Nash 2007, p. 37). The staging of cultural exhibitions by the Government was located within the latter frame (O’Sullivan 1994, pp. 196–97). Exhibitions, like ceremonies, were carefully staged, and these curated spaces where the protagonists were the artworks, as much as the people who came to experience the art and respond to the narratives encoded within its aesthetic forms and its display.

To give context to the Arnhem Land bark painting imagery—which has been used in commercial applications to promote tourism and in the collections and exhibitions that was toured to the US and whose impact has promoted US tourism in Australia—I have reviewed the significance of their history and their compelling appeal.

The Arnhem Land bark paintings were first brought to mainstream attention, through the collections and writings of a pioneering anthropologist, artist, and art collector, Baldwin Spencer. In 1912, he sent his first collection of bark paintings from the West Arnhem Land to the National Museum of Victoria (NMV), where he was an honorary director. The first 38 were not created for sale, but were found abandoned as painted panels of bark. They had been used as roofs for local shelters during the wet season. Spencer’s man-in-the-field for organizing the bark paintings for the Melbourne Museum was a local landowner and buffalo shooter, Paddy Cahill, who, following Spencer’s instructions, commissioned works from the artists that Spencer thought would have market appeal.

Many were larger than the first barks, and often included painted images of animals or hunting scenes (Geissler 2017, p. 55). A passionate advocate and promoter of Aboriginal art, Spencer wrote of the barks as ‘art’ and sent many to international institutional collections, in exchange for works from institutions that would enhance his own holdings at the NMV (Geissler 2017, p. 55). While he did not go so far as to provide individual names of the bark painters, he did acknowledge that the art was more than the product of a collective tribal will, that it was also a personal expression. He even compared the Kakadu painter to a ‘civilized artist’—‘today I found a native who apparently had nothing better to do than to sit quietly in the camp, evidently enjoying himself, drawing a fish on a sheet of Stringybark’. Spencer observed that the artist used a stick, which he held ‘like a civilized artist…he did line work, often very fine and regular, with much the same freedom and precision as a Japanese or Chinese artist doing his more beautiful wash-work with his brush’ (Lowish 2014, pp. 77–88; Geissler 2017, pp. 74–76; Spencer 2008, p. 107).

Anthropologist, Luke Taylor, argues that Spencer’s purchase of the Oenpelli paintings and their donation to the National Museum of Victoria had a significant impact, as one of the factors among others that would be important for the emergence of a market for Aboriginal art. However, this acclaim was not specifically located in art from a particular part of remote Australia (Taylor 1996, p. 24). Spencer’s collection of about 200 barks and other materials from the area were made over the period between 1912 and 1920 and resulted in the first substantial collection of Aboriginal art from the region. Of a much higher standard and more impressive scale than the few bark paintings in the existing collections, their display would have a huge impact on the Australian art world, as they were later curated in local and overseas exhibitions that included Aboriginal art, and images of the works were printed in the catalogues of the exhibition.14

Like the earlier Essington or Field Island barks, the images on the barks collected by Spencer in the Oenpelli region depict the figures of everyday animals, with which Aboriginal people came into contact, as well as those of their mythical world. The drawings of animals were rendered with their outline detailed along with their internal organs, such as backbone, alimentary canal, and heart. The sophistication of Aboriginal culture that was documented by Spencer laid the foundation for subsequent re-evaluations of the Aboriginal society, intelligence, and artistic accomplishment. They would lead to positive assessments of Aboriginal humanity and counter the limiting evolutionary frames of earlier times that largely characterized the interpretation Spencer had previously given to his data, which condemned the Aborigines as a race, with neither culture nor ‘art’.

Spencer’s collections (some 200 bark paintings), fieldwork, research, and publications, along with other professionals in the field, laid the foundations for positive assessments of Aboriginal humanity and culture, in the post-World War I years. The collections were selectively placed on view from the early 1920s, but they first came to public prominence in 1929, with the Museum’s landmark exhibition, Aboriginal Art (James 2014, p. 181).

Fieldwork, research, and publications throughout the decades, from the 1910s to the 1930s, by other professionals in the field visiting Arnhem Land and other parts of the Northern Territory and ‘remote’ Australia, were critical in driving forward the positive assessment of the Aboriginal culture. After the First World War, Social Evolutionism was universally discredited in scientific circles. However, the primitivism paradigm had an afterlife, beyond the demise of Social Evolutionism, as it had become lodged in the popular imagination, and also because the ideas of Tylor and Frazer, along with the writing of Spencer and Gillen, had been influential in leading the European intellectuals, such as Emile Durkheim and Sigmund Freud (Davis 2007, p. 121).

The notion of primitivism particularly lived on in the discourse concerning Aboriginal people and Aboriginal art, which is ironic, given that Aboriginal art, more than anything else, inspired scholars to think differently about Aboriginal culture. The term, ‘primitive art,’ became entrenched in art discourse, throughout most of the twentieth century, but its modernist understandings increasingly superseded those earlier views of ‘savage’ art. The aesthetic sophistication of the work encouraged audiences to appreciate it as exemplary in its inventiveness (Lévi-Strauss and Layton 1963, pp. 101–2; Geissler 2017, p. 61), variety, simplicity, sincerity, vigor, rawness, expressive power, conceptual complexity, and aesthetic subtlety (Rubin 2003, p. 132).15

However, the control of the rapidly changing meaning of ‘primitive’ and the discourse concerning this concept in the early years, which were largely reliant on anthropologists from the mid-twentieth century, were slowly augmented (rather than overtly challenged) by writers of the art world. For example, in 1938, anthropologist A.P. Elkin wrote, for the Australian Museum, in the highly influential publication on Aboriginal art, Australian Aboriginal Decorative Art:

The growing interest in and appreciation of primitive art in general and of aboriginal art in particular has a very important human, as distinct from scientific, implication. It is gradually causing persons who otherwise would either ignore or despise the aborigines to realize that a people possessing an art which is full of traditional meaning as well as expressive of many interesting motifs is much higher in the human scale than had been previously thought. The average white person is not impressed by totemism, kinship and sociological studies of aboriginal life, but a simple presentation of a native people’s art is something, which he can appreciate. I am hoping that this introduction to the decorative art of the Australian aboriginal … will contribute materially to the appreciation of the Australian aborigines both as a people possessed of artistic powers, and as human personalities. Moreover, in so far as we let the aborigines … know our appreciation, we shall help them to get rid of that feeling of inferiority for which contact with us has been responsible.(Elkin 1966, pp. 7–9)

Government departments and tourist agencies worked on the frontline with the Government to determine the nation’s cultural brand and to assist in the success of its global advocacy. Notable among these was, the Commonwealth Bureau of Census and Statistics, established in 1905 (Richardson 1999, p. 78), and the Australian National Travel Association (ANTA), which deployed Aboriginal-inspired designs for promotional purposes.

While Government posters from the early period were largely focused on launching Australia through reference to the uniqueness of the Australian landscape, its fauna, and the non-indigenous people of the nation and their lifestyles (indigenous Australians were not mentioned) (Vickery 1933; Trompf n.d.; Sellheim 1930; Great Britain n.d.; Northfield 1930a, 1930b; Curtis 1940),16 they also promoted the attractions of new modes of transport (Commonwealth Railways 1963; Williams n.d.; Jardine 1963).17 Importantly, it was in promoting the latter that Aboriginal art made its public debut. Margaret Preston’s advocacy, from the mid-twenties, of artists using Aboriginal art for applied design (Preston 1925; Preston 1930; Geissler 2017, pp. 81–85) was later reinforced by the Director of the National Gallery of South Australia, Mr. McCubbin (Adelaide Advertiser 1937, May 22). Preston believed that ‘the most interesting of work from a painter’s point of view is probably the bark paintings of Arnhem Land’ (Preston 1941a, p. 46; Preston 1963a, 1963b).

More subtle forms of international promotion, in the sense of a type of soft diplomacy, which was received by audiences in both a conscious and unconscious manner, was exemplified in the use of textiles (Black 1964, p. 160), interior design, and ceramics (Black 1964, p. xxi), which were inspired by Aboriginal motifs taken from bark paintings.

Qantas Empire Airways used Aboriginal designs on tapestry, curtains, and table-literature trays, in their offices in Australia and overseas, and for table mats and menu cards on their airlines (Black 1964, pp. xxi, 139–40; Sumner et al. 2010). Annan Fabrics’ textile designs, such as ‘The Kangaroo Hunt’ and the ‘Snake and Turtle’, were used in the Qantas’ offices in Honolulu, Canberra, New York, in the P-and-O shipping liner, Himalaya, and in the Aboriginal Rooms at Sydney’s elegant Hotel Wentworth (Black 1964, p. 162; Sydney Morning Herald 1953, July 28, p. 8; Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences 1950). The United Nations gift store in New York also sold these designs, inspired as they were by bark paintings,18 (Figure 3) and some were also displayed in the Australian Trade Centre in New York in the 1950s.

Figure 3.

Photographs of Aboriginals and Aboriginal-inspired, design displays at the Australian Trade Commission at the Rockefeller Centre in New York, image courtesy the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney.

Similarly, textile designs by Frances Burke, especially her ‘Kangaroo Hunt,’ inspired by a bark painting at the National Museum of Victoria, reflected the increasing importance of Aboriginal art in the Australian psyche (Black 1964, p. 163, Figure 129).

Other media showed a similar trend. The book illustrations of the Aboriginal-inspired artwork of Elizabeth Durak for Australian Legendary Tales reflected fine-line bark paintings (Black 1964, p. 145, Figure 111). Pottery exported for the American tourist industry included Aboriginal-inspired design line-work, referencing an engraved geometric design (Black 1964, pp. 153–54). Pottery from the Martin Boyd Pottery, demonstrably influenced by bark painting X-ray figures (Black 1964, pp. 155–60), was exhibited by Qantas to promote tourist trade (Black 1964, p. 157).

The first of the USA touring exhibitions of the post-war years, where the audiences were able to engage directly with the Arnhem Land bark paintings, was the 1941 exhibition, Art of Australia 1788–1941 (Geissler 2017, pp. 97–90),19 which, as noted previously, was sponsored by the Australian Government, as part of their soft power initiatives to encourage a closer US–Australia relationship. The concept for the show, while inspired by the David Jones exhibition of Australian Aboriginal Art and its Application in 1941, was curated by Fredrick McCarthy, an anthropologist at the Australian Museum in Sydney (Persson 2011, p. 80), with Preston, A.P. Elkin, and others acting as advisers.20

Evolutionist views were used by various authors in the exhibition catalogue essay to describe Aboriginal people, such as ‘a people defeated in the evolutionary cycle’ (Barnard 1941, p. 9) and ‘the world’s most primitive aborigines’ (Casey 1941, p. 5; Ryan 2007, p. 840). The art was seen as unable to survive, because its owners were dying out (Jordan 2013, p. 36). However, there were counterbalancing perspectives. Margaret Preston’s catalogue statement, celebrated the uniqueness of the people, the various stylistic differences across regions, and the impressiveness of their art; she notes, ‘Aboriginal art represents not only objects but [also] essential truths, which may or not be visible to the human eye’ (Preston 1941b, p. 16). She highlighted its aesthetic appeal and noted that it had much to contribute to modern Western art.

For the American curator of the exhibition, Theodore Sizer, the bark painting was the highlight of the show because of its modernist appeal. He described it to the Director of the Metropolitan Museum in New York, Francis Henry Taylor, as ‘a new art form … [with] some [objects] a-la-Picasso, but even better’ (Sizer 1941). The US and Canadian reviews for the exhibition were overwhelmingly positive, with the bark paintings often singled out for comment. The Christian Science Monitor found them ‘not trivial small affairs but large, positive and significant’ (Christian Science Monitor 1941).

On other fronts, interest in Australian Aboriginal art was advanced by the Australian, Charles Mountford, initially through his speaking tours of the United States, during 1945 and 1946, and then from the impact of his collections of Aboriginal bark painting, which he commissioned during the 1948 American–Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land, which he instigated. As an officer of the Commonwealth Department of Information in Australia,21 he convinced the American National Geographic Society and the Smithsonian Institute to mount the 1948 American–Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land (AASEAL), the nation’s most significant scientific expedition, with a mission to investigate the Arnhem Land Aboriginal culture.22

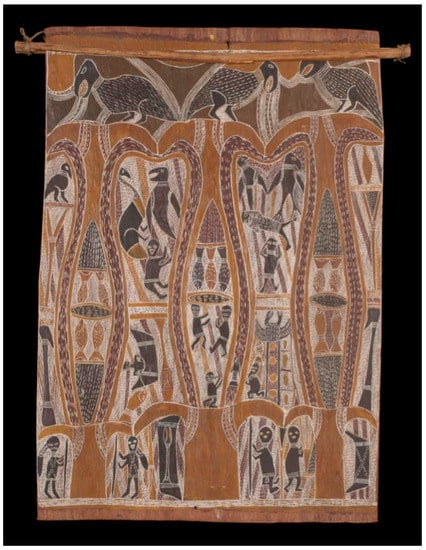

The ramifications were enormous, not only in improving good relations between Australia and the United States after WW2 [both scientifically and politically],23 but also in investigating a little-known part of the Australian continent (Elkin 1961, p. 54)24 and, in so doing, raising awareness of Aboriginal art. Reflecting the priority, the US research team gave to investigating the indigenous culture of Aboriginal Australians, Dr. Frank Setzler, Director of Anthropology for the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History, an expert in American Native archaeology, led the US-ASSEAL team (Setzler 1930, p. 43). He had part oversight of the ethnographic collections of the Expedition. As leader of the Expedition, Mountford visited the region between 1948 and 1949, collecting, among other items, a large amount of ethnographic material, 484 specimens of which were bark paintings and eighty-nine of which were donated to the Smithsonian (May 2008, p. 461; Zeller 2002, p. 74).25 For examples of the bark paintings donated to the USA Smithsonian collections refer Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7. These were amongst the paintings from the Expedition that were donated to Australian institutional collections, (Figure 4), (Narritjin Maymuru’s, Narritjin, Guwak ga Marrnu was donated to the collections of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, which are now housed in the National Museum of Australia in Canberra) and Mimi Spirits, 1948, Noulabil (the spirit man), 1949, Garkain, 1948/9 and Hunting Jabirus, 1948, which were donated to Art Gallery of South Australia in Adelaide.26

Figure 4.

Maymuru, Narritjin, (Mangilili people), Yinapunapu at Djarrakpi, c.1963, Ochre on bark, National Museum of Australia, Canberra, The Bennett Collection. © The estate of the artist. Licensed by Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Art Centre.

Figure 5.

Binyinyuwuy, Djeritmingin Spirit -Woolen River, 72.4 cm × 44.5 cm, Natural pigments on bark, image courtesy Art Gallery of New South Wales, Gift of Dr. Stuart Scougall. © Estate of the artist licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Ltd.

Figure 6.

Djawa, Tom, Djarrka (water goanna), c1987, Natural pigments on bark, image courtesy the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Gift of Dr. Stuart Scougall. © Estate of the artist licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Ltd.

Figure 7.

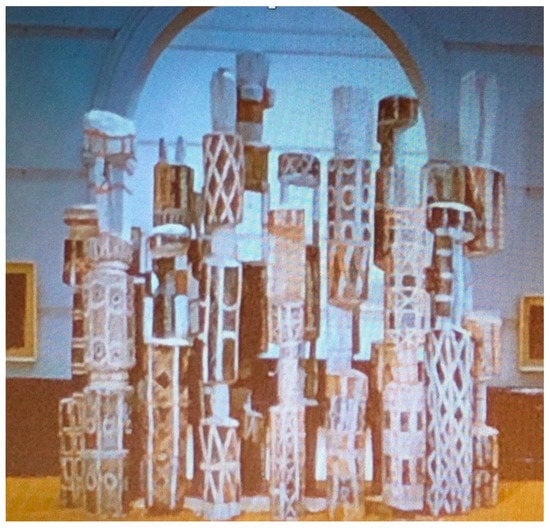

Pukamani grave post display by Laurie Nelson Mungatopi, Bob Apuatimi, Jack Yarunga, Charlie Kwangdini, Don Barukmadjua and an unknown artist (1958) that was exhibited with the Scougall bark paintings at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1960.33 © Tiwi Designs Aboriginal Corporation incorporated/Copyright Agency, 2019.

His publication of Volume 1—Art, Myth and Symbolism (1956) provided extensive documentation of bark painting, within an aesthetic framework, but because of the costs for its publication, it had a limited distribution in the Americas (Zeller 2002, p. 93). Anthropologist, A.P Elkin, commended Mountford’s efforts as ‘an excellent record of rock and bark paintings…[and that] the amount of material, which he obtained in the time [he was there], is amazing…When dealing with form and pattern, he must be listened to with great respect’ (Elkin 1961, p. 55). Likewise, anthropologist, W.E.H. Stanner, claimed that Mountford’s name should be added ‘to the list of those who may prove to have been most influential in making the public aware of…[the] long neglect [of Aboriginal/native peoples]’ (Stanner 1957, p. 311). While significant opposition was voiced from the scholars and authors to Mountford’s professional approach, it was a landmark moment in the history of barks, as he had illustrated four hundred bark paintings (Mountford 1958, p. 258) and the impact of Mountford’s work significantly contributed to the popularization of Aboriginal art, both in Australia and the United States (Lock-Weir 2002; May 2000; Neale 1998; Sear and Ewington 1998).

In 1954, he published Australian Aboriginal Paintings for UNESCO in London. This addition to The World Art Series was a collection of ‘very accessible’ photographs of bark painting and rock art, which proved highly successful in introducing the mainstream audiences to the Aboriginal culture. Impressively, 1.8 million copies were sold by 1959 (Neale 1998, p. 217). In 1964, it was republished as a miniature-sized version, with an expanded text (Mountford 1964).

Press reports from the ASSEAL expedition were included in The National Geographic Magazine, the official publication for the National Geographic Society in the U.S.A., known for its extensive pictorial, scientific-based editorial on world culture, which was highly influential and widely circulated internationally (Walker 1949, pp. 417–30; Mountford 1949, pp. 745–82). Mountford’s article included photographs of an artist painting a bark, one caption reading ‘Aboriginal Artists Explain Their Paintings to Expedition Leader’, and others were of rock art and images of the people, where Mountford presented them largely as ‘uncontrolled natives’ (Zeller 2002, p. 88). Reinforcing the scientific and cultural progress of America over others, was the emphasis in the presentations of the research (Zeller 2002, p. 89).

In 1950, Setzler, added a significant profile to the Australian Aboriginal art among US audiences, when he began a series of national speaking engagements in the US, armed with a one-hour film, entitled ‘Aboriginal Australia,’ based on the Expedition and made by the National Geographic Society. The obvious interest by US audience in Aboriginal art was reflected in the number of times he screened the film. It was shown in 28 cities. It included frames devoted to art, including rock art, an explanation of the ‘origins of bark art as decoration within the Aboriginals’ huts, and an unidentified artist demonstrating bark painting “as something quite characteristic of their material culture”’ (Zeller 2002, p. 91). Setzler continued to lecture using the film until as late as 1954, and a small section was screened on television in 1951 in a short film of eleven minutes and sixteen seconds (Zeller 2002, p. 92).

The bark collections arrived at the Smithsonian Institute National Museum of Natural History (Zeller 2002, p. 74) in 1949. Some were exhibited in the entrance spaces of the Natural History Museum, and occasionally, some were loaned to other exhibitions, such as the Cooper Hewitt Museum in New York, for their exhibition, The Power of Maps from 1992 to 1993. Within the Museum’s Oceanic displays, one case devoted to the Australian material from the Expedition included five bark paintings, for which little research was presented (Zeller 2002, p. 93).

From 1953, the Australian Committee for UNESCO would further advance US understandings of Aboriginal traditional culture and Arnhem Land bark painting, when it sponsored travelling exhibitions on the ASSEAL information, to five US natural history or science museums. These consisted of 24 didactic panels, written by Australian anthropologist, Fred McCarthy, from the Australian Museum in Sydney, who had been part of the Expedition team. They included panels on decorative art, rock engravings, cave paintings, and bark painting. These were accompanied by fifteen thousand brochures at each venue (Zeller 2002, p. 94).

Another promotion for the Arnhem Land bark painting to US audiences followed in 1956, but this time, it was initiated in Australia. For the promotion of Australian culture and national identity, directed toward overseas audiences, including those from the USA, for the 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games, an exhibition at the Victorian Museum in Melbourne was staged. Titled, The Arts Festival of the Olympic Games Melbourne (18 November–15 December 1956), it presented a wide variety of Aboriginal cultural objects, with comments on the art from different regions, including such items as baskets, cave art, stone churingas, carvings on shields and boomerangs, and bark painting. It was showcased alongside work by well-known, non-Indigenous Australian artists. Four decorated stone churingas and three bark paintings were illustrated in the catalogue.27

The catalogue, which did not directly target USA audiences but was distributed internationally, through the agency of the Olympics Committee, was indicative of a consensus within Australia about what aspects of Aboriginal art and lifestyle were of significance to Australian tourism messaging. It promoted many aspects of bark paintings and Aboriginal culture. In his catalogue essay, ‘Aboriginal Art’, ethnographer, Aldo Massola, reinforced his admiration for this art, the uniqueness of the culture, the potency of its mythological symbols and the attachment to place. He identified a spirit of ‘art for art’s sake’ in the artists’ mastery of line and conceptual skill (Massola 1956, p. 26). He described different regional styles with similarities in technique and symbol and the dynamic nature of Aboriginal culture (Massola 1956, p. 28). Reinforcing the anonymity of the artists and the remote tribal nature of Aboriginal people, neither the titles of their works, the medium, nor the artist’s Arnhem Land locations were listed for the Aboriginal works, while a similar corroborative data were provided for the non-indigenous artists. The three illustrated bark paintings were accompanied by descriptions of the mythological figurative subject, reinforcing the spiritual connection of the imagery to the land (Massola 1956, p. 26).

In 1965, an exhibition consisting of only Aboriginal bark paintings from the Museum of Victoria, was displayed at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas, Titled, Aboriginal Bark Paintings: Cahill and Chaseling Collections—National Museum of Victoria 1965–1966, the trajectory of its exhibition development and insights about the uniqueness of the Aboriginal people, their homelands, and their art, revealed a complex history of communication between the major protagonists of the show (Geissler 2017, pp. 143–50, Figures 58–73).

Central to the staging of this exhibition was the groundwork and advocacy in the field by the German refugee, ethnologist, and author of Penguin’s Primitive Art (1940), Leonhard Adam. Adam curated Primitive Art in 1943 for the National Gallery of Victoria, an early exhibition of Primitive art, where all works were chosen ‘purely [for their] aesthetic view’ (Adam 1942); (Geissler 2017, pp. 101–3). He was then a research scholar at the Department of History at the University of Melbourne (Lowish 2014, p. 5). He commended Aboriginal artists for ‘their artistic skill, imagination and refined taste in relation to aesthetic arrangements and decorative designs’, which were ‘infinitely superior to certain still more primitive races’ (Adam 1951, p. iii). Such approving regard for Aboriginal art by Adam was shared by his friend, Allan McCulloch, the influential Melbourne art critic of the Herald and foundation president (1963–1966) of the Australian division of the International Association of Art Critics (McCulloch 1961; James 2014, p. 184).

McCulloch, like Adam, was a passionate advocate for a ‘Museum of Primitive Art’ to showcase collections of Aboriginal art from Australia (Adam 1954; James 2014, p. 181). McCulloch’s sustained enthusiasm for the promotion of bark painting collections at the NMV, led to his curatorial involvement in the Houston show. In this, he was involved with John McNally, the director of the National Museum of Victoria, the legendary James Johnson Sweeney, Director of the Houston Museum, and the highly respected Karel Kupka, the Czech-born artist and curator of indigenous cultures, who had visited Australia on four occasions, prior to the Houston show, primarily to research and collect Aboriginal art and artefacts from the Arnhem Land, on behalf of Basel Musée d’éthnographie and, later, the Musée national des arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie in Paris, (now in the Musée du quai Branly), where he held the position of Chargé de Mission (James 2014, p. 182). It was on Sweeney’s brief official visit to Australia in 1962—where he was hosted by McCulloch in Melbourne—that his enthusiasm for Aboriginal bark paintings was initiated, and he raised the possibility of a special loan exhibition of the Spencer barks at NMV for Houston (James 2014, p. 184).

The high regard for the barks as items of fine art by Sweeney, who was regarded as ‘one of the most important art authorities to visit Australia,’ was pivotal in the highly contested decision for the exhibition to gain Australian Government support, and finally to be sent to Houston for exhibition. Showing his great appreciation of the Australian barks, Sweeney communicated his endorsement in a letter to the Chairman of the Board of Trustees at the NMV, dated 31 August, 1964. Referring to the bark paintings as ‘this remarkable group’, he stated that, in the proposed ‘major showing in the Museum of Fine Arts this coming season’, he ‘felt it would make the most effective display’. He said:

It would be a great privilege for the Museum to be able to show work of this character of the quality of Sir Baldwin Spencer’s Collection. Too many inferior examples of this art have been seen in the United States. The Museum of Fine Arts would be proud to show these infinitely superior examples which the Collection of the National Museum of Victoria boasts.28

As indicative of the regard for these works, the Museum offered to pay off the expenses of transportation and insurance to and from Australia. (These amounted to 715 Australian pounds, as can be found in McCulloch’s letter of 14 April 1965 to Sweeney—today valued at $AUS 19,403.47 (McCulloch 1965; Reserve Bank of Australia 2019). In a letter dated 17 October, 1964 from Sweeney to McCulloch, his regard for the works was evident in his statement that the barks ‘would have attracted wide attention and I am sure would have tempted other institutions to want to show them as well’.29

In McCulloch’s letter to Sweeney, dated 14 April, 1965, his approval for the Yirrkala barks of the Chaseling collection was stated—considering them to be ‘equally beautiful’ to the Spencer barks—after the proposal for the Spencer Collection to tour the USA was declined by the Museum of Victoria and he had proposed that the Yirrkala works could be used instead. Additionally, he claimed that a bark from the Melville Islands was ‘magnificent’. He commented, “They have a power of design which relates them to modern French abstracts, if you can imagine such abstracts on bark and with all the authority of primitive symbolism’. He notes that, as a consequence of the positive reception of the barks over recent years, ‘the government is going to give them more money’. In this approving vein, he infers that, the Melbourne Herald was also excited about the recent international acknowledgement of Australian Aboriginal art and stated it had proposed that they fund the visit to Australia of distinguished French novelist, art theorist, and Minister of Cultural Affairs, André Malraux (McCulloch 1965).

In the same letter, he referred to the agreed show as:

a truly magnificent one. It contains at least 4 if not 5 works by the Kakadu’s (long since extinct), some of the best Yirrkala works in existence as well as those from Oenpelli including the biggest known bark painting in existence. The Nat’l Museum trustees are now very proud of “their” show and one at least is visiting Houston to see it there.

Commenting on the Australian art travel circuit and how the distinction of the proposed Spencer bark exhibition had impacted Australians in the know, he announced that two of Australia’s most distinguished art professionals would visit it in Houston—high-profile Sydney gallerist, Rudy Komon, and the Harkness Fellow at Yale and artist, Leonard French. In his response to the exhibition, in his letter to Sweeney on 4 January, 1966, McCulloch writes ‘the barks couldn’t have looked better than they did’.

In a letter of 31 January, 1966, Sweeney, in writing to McCulloch, advised that they extended the exhibition by one week and that Chicago’s Museum of History was interested in it, a response that suggested that the exhibition was highly regarded by US professionals and would promote domestic tourism within the USA, because of the unique nature of the ar.30

While successful, in the end, the exhibition included a variety of works, with loans from the NMV, as well as other collections (James 2014, pp. 185–88).31 At Spencer’s request, the Spencer Barks were prohibited from leaving the country, so the barks from the Paddy Cahill and the Wilbur S. Chaseling collections were instead selected from the NMV, along with other loans for the show (James 2014, pp. 186–87). Issues concerning the fragility and uniqueness of the barks may well have been the deciding factors in determining Spencer’s request for them not to leave the Museum. The fragility of the barks was raised in a letter from J. McNally, the director of the National Museum of Victoria, to Sweeney, dated 14 October 1964, when he declined to allow the Spencer barks to leave his museum (James 2014, pp. 184–85).

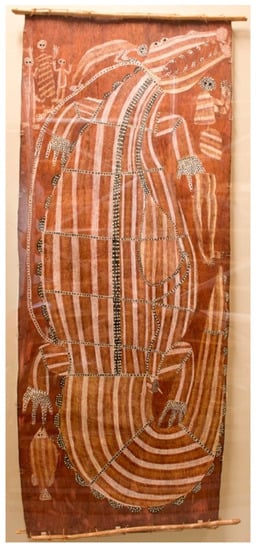

Spectacularly showcasing their aesthetic impact, the twenty-four barks of the display were dramatically suspended from the ceiling, in stark contrast to the large spaces of Houston’s white-walled, minimalist-designed gallery. Importantly, by exhibiting the art in a fine art context, the exhibition signaled its status as art and the artists of the work, far from being inflexible or locked in the past, as engaged with the modern world on their own terms (Geissler 2017, p. 148). The modest scale of the design of the catalogue and reproduction of the works in black and white, encouraged the appreciation of their artistic qualities alone.

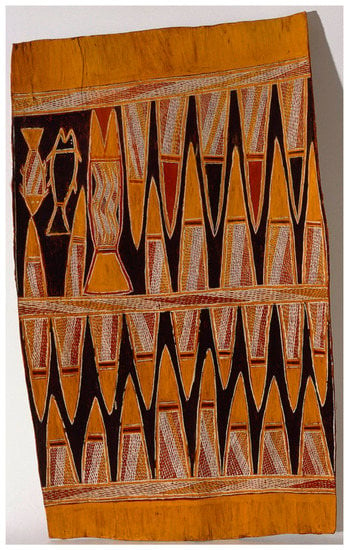

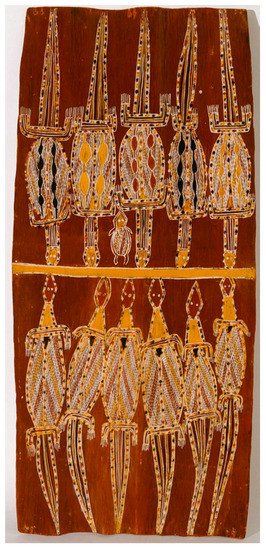

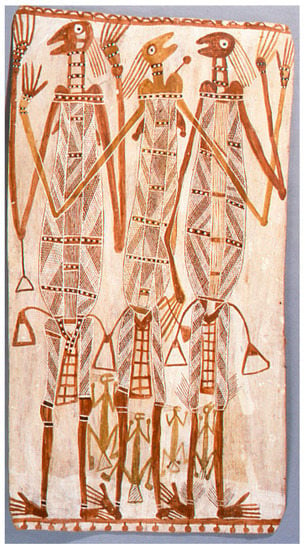

In the catalogue ‘Introduction’, Alan McCulloch gives a detailed insight into the unique tribal culture of the people, the rich food of their homelands on which they rely, their intelligence, quality of memory, which he ‘denotes as an ethnic type, with its own brand of genius,’ and the landscape in which they live. He gives a summary overview of the richness of Aboriginal art, throughout Australia, drawing attention to the ‘countless paintings, drawings and engravings on cave walls’, the ceremonial body painting, and designs used on objects for ritual and everyday utensils. He commends the ‘beauty of the art’, the vivid graphic depictions, and the ‘richly varied content…arranged with a matchless eye for primitive decoration’, claiming for the collection of barks at the NMV, the status of a valuable national treasure of primitive art (McCulloch 1965). This reinforced McCulloch’s earlier declaration of 1961, that the Aboriginal art in the nationally touring Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) Tuckson exhibition ‘would have caused a sensation had it been shown at a Venice Biennale’ (McCulloch 1961, p. 191; Tuckson and Art Gallery of New South Wales 1960) (Figure 8 and Figure 9).32

Figure 8.

Yirawala, Mimi Spirits, c. 1970, 90 cm × 48 cm, Ochre on bark, image courtesy the South Australian Museum, Adelaide. © The estate of the artist licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Ltd.

Figure 9.

Mick Gubargu, Crocodile Hunting Story, c.1979, 270 cm × 92 cm, Ochre on Bark, image courtesy South Australian Museum, Adelaide. © The estate of the artist licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Ltd.

Sweeney reinforces these positive commentaries in his essay:

We find clearly exemplified that innocence of eye and unselfconscious expression which artists of the twentieth century, since its first decade have been struggling to achieve—the two ideals which have given the convention bound observer the greatest difficulty in approaching contemporary art. These qualities are illustrated to one degree or another in all so-called native artists ….

He continues:

… because of the primitivism of their makers, these qualities come out for us with a particular clarity in their closeness to the primitive psychological experience—their communication of tensions among visual relationships overlaid by a minimum of readily recognizable, distracting relationships’.(McCulloch 1965)

The exhibition was a triumph, in that its aim to impress the audiences of the compelling appeal of the art, resulted in offers for the exhibition to travel to MoMA in New York, the Chicago Museum of Natural History, and Paris. None, however, eventuated (James 2014, p. 193).

Soon to follow, in the USA, was the bark collection of Professor Edward L. Ruhe, put together during 1965, when he was in Australia as a Fulbright Visiting Lecturer at the University of Adelaide. These works were mainly from the 1964–1965 period; titled, Bark Paintings from Arnhem Land, forty-two were exhibited at the Museum of Art at the University of Kansas, from 27 March to 1 May in 1966, and eighteen were illustrated in the catalogue.

While the exhibition received no funding from the Australian Government, its impact was very positive for the reception of Aboriginal bark painting and culture, an indication of the increasing interest, in the USA, in Aboriginal people and their cultural productions. The Edward L. Ruhe catalogue essay, ‘Bark Paintings from Arnhem Land,’ presented a very considered evaluation of the uniqueness of the Aboriginal people, their lifestyle, and attachment to land and their art, in which:

the artists often painted … their impressions of the sacred places of the clan; especially their interpretations of the water hole and its surrounding country or the artist’s “dreaming” of it.(Ruhe 1966, p. 1)

Ruhe notes the intelligence of the Aboriginal artist pointing out that s/he:

… certainly, had something like a fully developed human brain; even more certainly he was a human being who before middle age seemed to have a larger quantity of organized material packed into that brain than any European could easily conceive—thousands of songs, hundreds of rituals, legends, stories, dances, particulars of tribal history, easy mastery of a complex kinship system and a range of difficult crafts appropriate to bush life. He was likely to know one of several languages in addition to his own, not counting the widespread sign languages’… ‘These were peoples without chiefs because everyone in some sense had his part in tribal government.(Ruhe 1966, p. 5; Geissler 2017, pp. 144–46)

Ruhe says of the bark painting that they were ‘confident, energetic, sincere, often powerful or beautiful expressions of mental processes and imaginations, instructively different from our own, and which may not convincingly be identified as inferior in any deep sense’ (Ruhe 1966, p. 14). He continues:

As any viewers on easy terms with the contemporary art of the Western world will readily see, a whole range of excellences available to only a lucky few of our own artists may seem to be the common birth-right of the Australian bark painters … One might suspect, in looking at good bark paintings, that the profound indifference of the aboriginals to Europeans and their material culture continues to be present today.(Ruhe 1966, p. 14)

In the 1970 exhibition catalogue for Australian Aboriginal Art: Louis A. Allen Collection, held at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Jim Davidson (1908–1994), who had collected for Louis Allen (1917–2010), the American multimillionaire and patron of the show, elaborated on the distinctive character of Aboriginal artists, their lifestyle, and art. Reflecting on the adaptive nature of Aboriginal traditions, he noted that some regions were being more influenced by contact with the outsiders than others. The north-eastern people, he said, were the more advanced, because they adopted the sophisticated cultural influences of the Macassans, namely, batik designs that were modified, absorbed, and used as background infill for the images of superheroes that were painted on the bark. The infill in the east, he observed, could be identified by the mala pattern.

The central Arnhem Land artists, by contrast, were hostile to strangers and consequently retained a more traditional style. Their paintings had a little fine-lined background infill and had more stylization in their figurative representations. However, the west Arnhem Land artists, being very isolated, developed their iconography by adapting the imagery of the cave paintings of the region. They had X-ray-style detailing, fine human stick-like images, and stylized figures, representing a variety of Mimi spirits. Their figurative imagery looked like the art of the prehistoric arts of Spain and the Kalahari Desert (Davidson 1970, p. 5; Taylor 1996, pp. 127–241; Taylor 2013, p. 21).

Davidson reinforced the positive perceptions of Aboriginal art in the past, by commending its aesthetic appeal in Western aesthetic terms, noting that the designs were strong in terms of harmony, proportion, and rhythm and that the art was a living tradition, where the styles of older artists could be recognized in the work of later artists. He claimed that the art of the Yirrkala artists is ‘one of the outstanding forms of primitive art remaining in the world today’ (Davidson 1970, p. 5).

The distinctive traditional cultures of the Aboriginal people from the remote Arnhem Land, whose bark paintings were sourced for the display of the Louis Allen Collection in 1972, were acknowledged in the exhibition catalogue. Held at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, with no funding from the Australian Government, the forty-nine Aboriginal bark paintings illustrated in the catalogue were supported by a selection of traditional spirit figures, totems, bark coffins, a Pukamani pole, and ceremonial objects (Allen 1972).

This thread was picked up in Newsweek’s ‘Art of the Abos’, 20 March 1972. The journalist commented that:

they carefully learned dot, line and cross-hatch patterns … [and] the intricate designs show that the art is from a primitive people…a static Aboriginal culture…[whose] people [are] in decline.

The same columnist also registered a positive commentary on the aesthetic impact of the bark painting, with Newsweek’s columnist pointing out the art’s ‘formal brilliance’ (Newsweek 1972; (Geissler 2017, pp. 160–61). That such high regard for the art had begun to travel in the circles of the art world in the USA was reflected in comments that were made in 1974, by the visiting curator of the twentieth-century art from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Henry Geldzahler. After seeing the Aboriginal art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, he exclaimed, ‘there is no doubt about it. It is major world art. It ought to be sent abroad—to Paris, London, New York, and perhaps Peking. It would create enormous interest’ (Radic 1974).

Endorsements, such as that for the unique culture of Aboriginal Australians, resonated with the positive receptions for Aboriginal art of earlier years, which had been written for overseas audiences. In particular, Herbert Read wrote about Aboriginal art in his ‘Introduction’ to the UNESCO’s publication, Aboriginal paintings, Arnhem Land, which was published in association with the New York Graphic Society in 1954. This addition to ‘The World Art Series’ was a collection of ‘very accessible’ photographs of bark painting and rock art, which proved highly successful in introducing mainstream audiences, including those of the USA, to Aboriginal culture. Impressively, 1.8 million copies were sold by 1959 (Neale 1998, pp. 210–17). Read called the art ‘drawings’, ‘pictorial communication’ and ‘art’, and framed them within a discussion of being ‘spontaneous’ and as having ‘an intuitive sense of form’ and ‘feeling for harmony (UNESCO 1954, p. 5)’.

However, although Aboriginal bark painting and the uniqueness of the culture were appreciated in the USA at the beginning of the 1970s, the same was not the case for the understandings of the places in which they lived. The uniqueness and diversity of the landscapes of the coastal and inland Arnhem Land communities, where the bark paintings were created, were not explicitly described and located, but were only inferred through the discussions of the ‘Dreaming’ and remote tribal life of hunting and ceremony, in the art catalogues of the aforementioned exhibitions.

The communities where Aborigines lived were underdeveloped as tourist destinations. Indigenous people lived in missions or in isolated camps and were dependent on State and Territory Aboriginal welfare authorities, for their day-to-day needs (Altman and Saunders 1991, pp. 1–2). Participation in an internationally driven tourist industry was years away for remote artists. Direct payment to Aborigines was still only being made once they had demonstrated their ‘ability’ to handle money wisely, and ‘manage’ their ‘own affairs’. It was only in the early 1970s, under the Whitlam Government, that things began to change. The Department of Aboriginal Affairs was established to ‘incorporate legally for the conduct of their [Aboriginal people’s] own affairs and for the provision of many of their own services’ (Altman and Saunders 1991, p. 6; Geissler 2017, pp. 161–62).34

In summary, by the beginning of the 1970s in the USA, the subtle messaging of Aboriginal imagery, which had been inspired by the Arnhem Land bark painting and used in both tourist design applications and was presented in the exhibitions of the Arnhem Land bark painting, had established the foundations for understanding Australia as a destination where the exotic, remote, wilderness-based culture of the Australian Aboriginal was to be encountered. At this time, these cultural factors were one of the many elements in a complex interplay of local and international soft power initiatives that found momentum within the art world and laid an enviable foundation on which future cultural initiatives between the US and Australia would be taken up. A watershed cultural moment for both countries was reached in the next decade, when the exhibition, Dreamings. The Art of Aboriginal Australia, was held in New York at the Asia Society Galleries, in 1988, the year of the Australian Bicentenary (Sutton et al. 1988; Sutton 1988)35 (Refer Figures 11–13).

Like earlier Indigenous art exhibition events, this was another cultural strategy of the Australian government and, importantly in this instance, provided a global audience to one of Australia’s most successful products, Australian Contemporary Aboriginal Art, a cultural export that, looking back from 2001, as an art historian, Terry Smith advised, ‘attracts tourists and students’ (Smith 2001, p. 75).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Sincere thanks to Catherine De Lorenzo and Professor Ian Mclean for their editorial advice. For use of images, I thank the South Australian Museum, Adelaide, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney, The National Library of Australia, Canberra, The National Museum of Australia, Canberra and Joseph Lebovic, Sydney.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. Material used in the text was drawn from the author’s PhD. diss., “Arnhem Land Bark Painting. The Western Reception 1850–1990,” 2017, University of Wollongong. Wollongong, Australia. https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses1/399.

References

- Adam, Leonhard. 1942. Draft Exhibition Proposal, Primitive Art Exhibition, 9 October, VPRS 805/P4 Inward Registered Correspondence, Unit 5, File J. North Melbourne: Public Records Office of Victoria (PROV). [Google Scholar]

- Adam, Leonhard. 1951. Aboriginal Art. In Jubilee Exhibition of Australian Art: Aboriginal Art, Early Colonial Art, the Art of the Middle Period, Contemporary Art, Organized by the Plastic Arts Committee for the Commonwealth Jubilee Celebrations. Sydney: Ure Smith. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, Leonhard. 1954. Letter to Allan McCulloch, 29 March 1954. McCulloch Papers, Collection. Melbourne: La Trobe University Library. [Google Scholar]

- Adelaide Advertiser. 1937. Aboriginal Art and National Spirit. Gallery Director Favours Wider Use. In Adelaide Advertiser; May 22, p. 16. Available online: http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/74347303?searchTerm=%E2%80%98Aboriginal Art and National Spirit.&searchLimits= (accessed on 11 June 2014).

- Allen, Louis A. 1972. Australian Aboriginal Art: Arnhem Land. Chicago: Field Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, Jon C. 1988. Aborigines, Tourism, and Development: The Northern Territory Experience. Australian National University North Australia Research Unit Monograph. Canberra: Australian National University. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, Jon, and William Saunders. 1991. From Exclusion to Dependence: Aborigines and the Welfare State. Discussion Paper, No. 1. Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Angus, George F. 1847. Observations on the Aboriginal Inhabitants of South Australia. In Savage Life and Scenes in Australia and New Zealand. London: Smith, Elder, and Co., vol. 1, p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Australian National Travel Association. 1936. Australia. Travel Brochure. Canberra: Australian National Travel Association. [Google Scholar]

- Australian National Travel Association. 1954. Attracting Tourists to Australia. Government Grants for Tourist Promotion. Report. Canberra: Australian National Travel Association. [Google Scholar]

- Australian National Travel Association. 1962. ANTA News Bulletin. Canberra: Australian National Travel Association. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Tourist Commission. 1971. Australian Overseas Visitor Statistics 1965–1970. Melbourne: Development & Research Division, Australian Tourist Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Tourist Commission. 1972. Australia. Overseas Visitor Statistics 1966–1971. Melbourne: Development & Research Division, Australian Tourist Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, Marjorie. 1941. Introduction. In Art of Australia 1788–1941/An Exhibition of Australian Art Held in the United States of America and the Dominion of Canada, Carnegie Corp. by the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Edited by Ure Smith. Sydney: Ure Smith, pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, Gillian. 2010. Aboriginal Cultural Tourism: Enterprise/Contested Mobilities and Negotiating a Responsible Australian Travel Culture. Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues 18: 116–41. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, Tony. 2010. “Nothing has changed”: The making and unmaking of Koori culture. Meanjin 69: 107–18. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Roman. 1964. Old and New Australian Aboriginal Art. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Peter, Kerry Donohue, William Montgomery McGovern, and Jan McMillan, eds. 1991. Tourism in Australia. Sydney: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, Maie. 1941. Foreword. In Art of Australia 1788–1941/An Exhibition of Australian Art Held in the United States of America and the Dominion of Canada under the Auspices of the Carnegie Corporation and the Museum of Modern Art, New York.re Smith/Compiled and Edited by Sydney Ure Smith. New York: Carnegie Corporation and the Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, Denise, and Suzy Russell. 1941. The Responsibilities of Leadership: The records of Charles P. Mountford. In Exploring the Legacy of the 1948 Arnhem Land Expedition. Edited by Martin Thomas and Margo Neale. Canberra: ANU Press, Available online: http://www.jstore.org/stable/j.ctt24h9p1.18 (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- Christian Science Monitor. 1941. The Art of Australia. Christian Science Monitor, October 18. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Ian, and Louise Larrieu. 1998. Indigenous Tourism in Victoria. Products, Markets and Futures, Paper Presented at ‘Symbolic Souvenirs’. A One-Day Conference on Cultural Tourism at the Centre for Cross Cultural Research, Australian National University. Canberra: Australian National University. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Railways. 1963. There and Back by Trans-Australian Railway. Library of Congress Website. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2018648013/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Craik, Jennifer. 2001. Tourism Culture and National Identity. In Culture in Australia. Policies, Publics, Programs. Edited by Bennett Tony and Carter David. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, R. Emerson. 1940. Canberra, Australia’s National Capital. Library of Congress. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2018648014/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Davidson, James. 1970. Foreword. In Australian Aboriginal Art: Louis A. Allen Collection. Santa Barbara: The Art Galleries, University of Santa Barbara. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Michael. 2007. The Depiction of Indigenous Heritage in European-Australian Writings. North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing, p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- Elkin, Adolphus Peter. 1961. Elkin Archives, Private Correspondence, 1956–1979, Items 5/2/23. Quoted in De Lorenzo 2015: 5. Sydney: Fisher Library, University of Sydney. [Google Scholar]

- Elkin, Adolphus Peter. 1966. Foreword. In Australian Aboriginal Decorative Art, 7th ed. Edited by Frederick D. McCarthy. Sydney: Trustees of the Australian Museum, pp. 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Geissler, Marie. 2017. Arnhem Land Bark Painting. The Western Reception 1850–1990. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses1/399 (accessed on 19 February 2019).

- Gray, Geoffrey. 1998. Nomadism to Citizenship: A. P. Elkin and Aboriginal Advancement. In Citizenship and Indigenous Australians. Edited by Nicholas Peterson and Will Sanders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Great Britain. n.d. BOAC Qantas, Australia New Zealand. Library of Congress Website. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2009632108/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Hall, Colin Michael. 1961. Introduction to Tourism in Australia: Development, Issues and Change. Frenchs Forest: Pearson Education Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Harris Kerr Forster and Co. 1966. Australia’s Travel and Tourism Industry 1965. Report Commissioned by Australian National Travel Association. Sydney: Stanton Robins and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, Chas. H. 1938. Signed Report written for the ANTA. In Australia’s 150th Anniversary Celebrations. Reviewing the Activities of the Australian National Travel Association in Securing Publicity for the Celebrations throughout the World. Sydney: Australian National Travel Association. [Google Scholar]

- James, Rodney. 2014. The Battle for the Spencer Barks: From Australia to the USA, 1963–1968. Latrobe Journal 93–94: 181. [Google Scholar]

- Jardine, Walter. 1963. Travel–Air, Land, Sea. Book through Burns Phillip & Co. Ltd. Library of Congress Website. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2007676064/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Jordan, Caroline. 2013. Cultural exchange in the midst of chaos Theodore Sizer’s exhibition ‘Art of Australia 1788–1941’. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 13: 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinert, Sylvia. 2012. ‘Keeping up the Culture’: Guani Engagements with Tourism. Oceania 82: 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Noel Pasco. 1930s. Queensland Tourist Bureau, World’s Premier Wonderland, Great Barrier Reef, Queensland. Library of Congress Website. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2015647587/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude, and Monique Layton. 1963. Structural Anthropology. Translated by Claire Jacobson, and Brooke Grundfest Schoepf. New York: Basic Books, pp. 101–2. [Google Scholar]

- Lock-Weir, Tracy. 2002. Art of Arnhem Land 1940s–1970s. Adelaide: Art Gallery of South Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Lowish, Susan. 2014. Mapping Connections Towards an art history of early Indigenous Collections at the University of Melbourne. Cultural Treasures Festival Papers 1: 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lydon, Jane. 2002. Eye Contact: Photographing Aboriginal Australians. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Massola, Aldo. 1956. Aboriginal Art. In The Arts Festival of the Olympic Games Melbourne. Melbourne: The Olympic Civic Committee of the Melbourne City Council for the Olympic Organizing Committee MCMLV1. [Google Scholar]

- May, Sally K. 2000. The Last Frontier? Acquiring the American-Australian Scientific Expedition Ethnographic Collection 1948. Bachelor’s Dissertation, Flinders University of South Australia, Bedford Park, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- May, Sally K. 2008. The Art of Collecting: Charles Percy Mountford. In The Makers and Making of Indigenous Australian Museum Collections. Edited by Nicolas Peterson, Lindy Allen and Louise Hamby. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- May, Sally K. 2009. Collecting Cultures: Myth, Politics and Collaboration in the 1948 Arnhem Land Expedition. Lanham, Md: Altamira Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch, Alan. 1961. The Aboriginal Art Exhibition. Meanjin 20: 2. [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch, Alan. 1965. Introduction. In Aboriginal Bark Paintings from the Cahill and Chaseling Collections. National Museum of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia, The Museum of Fine Arts. Edited by Edmond Lehman Ruhe. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, Ian. 1998. Aboriginalism: White Aborigines and Australian Nationalism. Australian Humanities Review. Available online: http://www.australianhumanitiesreview.org/archive/Issue-May-1998/mclean.html (accessed on 24 July 2015).

- McLean, David. 2006. From British Colony to American Satellite? Australia and the USA during the Cold War. Australian Journal of Politics and History 52: 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell Library Manuscripts. n.d. Qantas Travel Reports. In Horne Papers. MLMSS32525 MLK 02153. Sydney: Mitchell Library Manuscripts.

- Morphy, Howard. 2001. Seeing Aboriginal Art in the Gallery. Humanities Research 111: 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountford, Charles. 1945. 5 March 1945. Letter to the Chairman of the National Geographic Society Research Committee. Accession File 178294. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Archives, p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mountford, Charles. 1949. Exploring Stone Age Arnhem Land. National Geographic Magazine XCV1: 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Mountford, Charles. 1956. Records of the American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land. Volume 1: Art, Myth and Symbolism. Carlton: Melbourne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mountford, Charles. 1958. The Mountford Volume on Arnhem Land Art, Myth and Symbolism: A critical Review-A Rejoinder. Mankind 5: 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountford, Charles. 1964. Aboriginal Paintings from Australia. Fontana UNESCO Art Books. New York: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences. 1950. Curtains (2). Kangaroo Hunt. Cotton, Annan Fabrics, Sydney, Australia. MAAS Website. Available online: https://collection.maas.museum/object/148770 (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Museum of Fine Arts. 1960. Search the Collection. Drawings on Bark. Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Available online: https://www.mfah.org/art/search?q=drawing+on+bark+&page=1 (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- Nash, Dennison, ed. 2007. The Study of Tourism: Anthropological and Sociological Beginnings. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Neale, Margo. 1998. Charles Mountford and the "Bastard Barks". A gift from the American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land, 1948. In Brought to Light. Australian Art 1950–1965, from the Queensland Art Gallery Collection. Edited by Lynne Sear and Julie Ewinqton. Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery, pp. 210–17. [Google Scholar]

- Neale, Margo. 2009. Epilogue: Sifting the silence. In Margo Neale (Project Director), Birds Barks and Billabongs Symposium, National Museum of Australia’, ANU Press Website. Available online: http://pressfiles.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p116081/pdf/ch211.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- Newsweek. 1972. Art of the Abos. Newsweek, March 20. [Google Scholar]

- Northfield, James. 1930a. Koala (Native Bear) Australia, Particulars at Shipping and Travel Agencies. Library of Congress. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2015647589/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Northfield, James. 1930b. Melbourne. The Garden Capital of Victoria, Australia. Take a Kodak. Library of Congress. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2014646275/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Nugent, Maria. 2005. Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet. Sydney: Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, Tim. 1994. Key Concepts in Communication and Cultural Studies. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Michael. 1997. The Tourist Corroboree in South Australia to 1911. Aboriginal History 21: 46–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, Michael. 2002. Ah that I could convey a proper idea of this interesting wild play of the natives: Corroborees and the rise of Indigenous Australian cultural tourism. Australian Aboriginal Studies 2: 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Peat Marwick Mitchell and Co. 1972. Financing Tourist Development. A Study on Behalf of the Australian National Travel Association. Sydney: Peat Marwick Mitchell and Co., p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, Beatrice. 2011. In-Between: Contemporary Art in Australia. Cross-Culture, Contemporaneity, Globalization. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden. Available online: https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/26256/1/gupea_2077_26256_1.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2015).

- Preston, Margaret. 1925. Indigenous Art of Australia. Art in Australia, March 11. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Margaret. 1930. The Application of Aboriginal Designs. Art in Australia, March 3. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Margaret. 1941a. Aboriginal Art of Australia. Art in Australia, June 4–September 6. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Margaret. 1941b. Aboriginal Art of Australia. In Art of Australia 1788–1941/An Exhibition of Australian Art Held in the United States of America and the Dominion of Canada, Carnegie Corp. by the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Edited by Ure Smith. Sydney: Ure Smith, pp. 16–7. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Margaret. 1963a. National Art Gallery of New South Wales, Domain. Sydney. Carnegie Corporation of New York Educational Service. Five Lectures by Margaret Preston. 1st. The Importance of Understanding Art with Some Early Murals to Those of 1938. MS 1963.1 Preston, Folder One, Research Files. Sydney: AGNSW. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Margaret. 1963b. National Art Gallery of New South Wales, Domain. Sydney. Carnegie Corporation of New York Educational Service. Five Lectures by Margaret Preston. 2nd. Australia, Aboriginal Paintings—Arnhem Land. MS 1963.1 Preston, Folder One, Research Files. Sydney: AGNSW. [Google Scholar]

- Radic, Leonard. 1974. Aboriginal art is in world class—Expert. Age, October 5, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Reserve Bank of Australia. 2019. re-Decimal Inflation Calculator, Reserve Bank of Australia Website. Available online: https://www.rba.gov.au/calculator/annualPreDecimal.html (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Richardson, John L. 1999. A History of Australian Travel and Tourism. Melbourne: Hospitality Press, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, William. 2003. Modernist Primitivism: An introduction. In Anthropology of Art: A Reader. Edited by Howard Morphy and Morgan Perkins. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 129–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhe, Edward Lehman. 1966. Bark Paintings from Arnhem Land. In Bark Paintings from Arnhem Land. Kansas: Museum of Art, University of Kansas, pp. 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Louise. 2007. Forging Diplomacy: A Socio-Cultural Investigation of the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Art of Australia 1788–1941 Exhibition. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Sear, Lynne, and Julie Ewington. 1998. Brought to Light: Australian Art 1850–1965. Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Sellheim, Gert. 1930. Australia—Sunshine and Surf/Sellheim. Trove. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2007676059/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Setzler, Frank. 1939. The Archaeology of Whitewater Valley. Indianapolis: Historic Bureau of the Indiana Library and Historical Department. [Google Scholar]