Circling Round Vitruvius, Linear Perspective, and the Design of Roman Wall Painting

Abstract

1. Background

1.1. Definitions

1.2. Brief History of Skenographia as Linear Perspective

2. Literary Sources

2.1. Vitruvius 7. Preface. 11

While the passage presents a number of problems, its reference to rays, a center point, projection, and recession are believed to describe linear perspective. The dates of Agatharcus and the two philosophers indicate the origin of skenographia in the fifth century BCE. That Vitruvius does not explicitly mention skenographia or connect this passage with 1.2.2 and vice versa is considered unimportant.learned from it [the treatise] and in turn wrote about the same subject [res]: that is in what way lines should respond in a natural relation [ratio naturalis] to the point [acies] of the eyes and the extension of the rays [radii] once a fixed [certus] place [locus] has been established as the center, in order that from a dimly perceived object precise images of buildings in the paintings of the stage-buildings [imagines aedificiorum in scaenarum picturis] [may] reproduce an appearance [species] with some [lines] seen extending [prominentia] and others receding when depicted on the vertical [directus] surfaces and fronts [of a stage-building/scaena].14

This description echoes that of 7.Pr.11 while unambiguously stating that color and shades produce projection and recession.For the light does not fall in a similar way on all parts of what is uneven, because some of them are concave, some convex, some sideways on to the [source] of the illumination, some opposite to it. On account of these differences, even if what is seen is of a single colour, some [parts] of it seem dimmer, others more conspicuous, and thus some will be seen as recessed and others as projecting. Painters imitate this when they want to show on the same plane what is uneven, and make some parts light while shading others. Thus some [parts] of [what they paint] appear projecting, others recessed, and as projecting those that are made more light, as recessed those that are shaded.16

First, whatever we see comes to or goes from the eyes in straight lines. Hence, straight lines and rays are not exclusive to linear perspective. Second, Democritus and Anaxagoras then, to their surprise, realized that shading and shadows made things look “real”, in our terms three-dimensional, and notably did so not with curved rays, but the usual straight ones.For it [sight] sees the things that it sees by a cone which has the pupil as its vertex and as its base the line which defines what [part] of the perceived body is seen and what not. … and the colouring, as it were, that comes about … in straight lines in a similar way to light …. It is by the angles of these cones that [sight] judges larger and smaller and equal things. For it sees [as] equal those things the sight of which involves equal angles, [as] larger than those which involve larger ones.17

[T]he perspective of the ancients (at least in its theoretical exposition) is ‘angular’ (or curvilinear), instead of being ‘planar’ as that of the Renaissance: in the perspective of the ancients, the apparent size of a receding object diminishes not as a function of its distance, but as a function of the angle under which it is seen—which does not amount to the same.18

Pliny emphasizes the role of “light” (lumen) whether in contrast to “shade” (umbra) or “highlight”, as “splendor” is commonly translated.22 Completely absent is any mention of skenographia. Pliny’s emphasis on color, along with light and shade, reflects the ancient assessment of painting. Philostratus (Appendix A No. 7), in the following century, also defines painting as “imitation by the use of colours… [it] reproduces light and shade.”23At length the art [of painting] differentiated itself and invented light and shades, using a diversity of colors which enhanced one another through their interaction. Finally splendor was added, which is something quite different from light. That which exists between light and shade they called tonos, and the transition from one color to another they called harmoge.21

2.2. Lucretius, On the Nature of Things, 4.426–431

At first, Lucretius seems to refer to a vanishing point and therefore central projection. Euclid (Optics, Definition 2; Appendix A No. 9), however, uses similar wording that precludes the idea of a vanishing point: “and that the form of the space included within our vision is a cone, with its apex [κορυφὴν] in the eye and its base at the limits of our vision.”26 If the top of the cone vanished, so would the image. Lucretius, instead, means that objects are not viewable from a distance. Lastly, classical depictions of colonnades do taper from the sides to the center but never come close to meeting, much less disappearing.When we gaze from one end down the whole length of a colonnade, though its structure is perfectly symmetrical and it is propped throughout on pillars of equal height, yet it contracts by slow degrees in a narrowing cone that draws roof to floor and left to right till it unites them in the imperceptible apex of the cone [donec in obscurum coni conduxit acumen].25

3. The Evidence from Classical Art

4. The Purpose of Vitruvius’ Skenographia

First, a clarification must be made: English has only one word for “proportion”, whereas Greek and Latin have two words—analogia and symmetria for Greek and proportio and symmetria for Latin. Analogia is more or less equivalent to our use of “proportion”. Symmetria, however, did not mean “symmetry” in the modern sense of a mirror-image arrangement. It referred instead to the balance or commensurability among the individual parts of a whole. An extremely large head, for example, looks incongruous on a diminutive body. Thus, analogia refers to the relationships between whole things, while symmetria refers to the relationships within a single thing or whole. I use symmetria for the classical word and symmetry for our concept.42Ordinatio [order] is the ordinary [modica] aptness [commoditas] of the parts of the work separately and together, a comparison [comparatio] of proportion [proportio] to symmetria. This is based on size [quantitas], which is called posotes in Greek. Size [quantitas], moreover, is the taking [sumptio] of modules from the parts of the work itself and the harmonious result [conveniens effectus] [comes] from the individual sections of the parts.

In Book 3 on temples, Vitruvius expands on 1.2.4. He uses a drawing of a man to show how proportion, based on a module, produces the “best” structures. He begins (3.1.1 = Appendix A No. 13) by rephrasing 1.2.2:Likewise symmetria is the consistent agreement among the elements of the work itself and the proportionate [ratae partis] correspondence [responsus] of the separate parts to the appearance of the whole form. As in the human body from cubit, foot, palm, finger, and the other small parts, the nature of eurythmia is symmetros (proportionate), so it is with the finishing of the work.

The composition of a temple is based on symmetry, whose principles architects should take the greatest care to master. Symmetry derives from proportion, which is called analogia in Greek. Proportion is the mutual calibration of each element of the work and of the whole, from which the proportional system is achieved. No temple can have any compositional scheme without symmetry and proportion, unless, as it were, it has an exact system of correspondence to the likeness of a well-formed human being.43

Now, the most troublesome section of Vitruvius’ definition of skenographia becomes clear. Vitruvius really does mean “all lines” are to “correspond” to the “center point”, because he is not talking about linear perspective but symmetria. His qualification of “sides” with “receding” describes how they look.Therefore: if it is agreed that the numerical system was derived from human members, and that there should be a commensurable relationship [commensus fieri responsum] based on accepted units between those members taken separately and the form of the body as a whole, it remains for us to demonstrate the greatest respect for those who, when building temples for the immortal gods, arranged the elements of the buildings in such a way that, thanks to the proportions and symmetriae [proportionibus et symmetriis], the arrangement of the individual elements and whole corresponded to each other.46

5. Designing Roman Wall Paintings

5.1. The Evidence from Philostratus

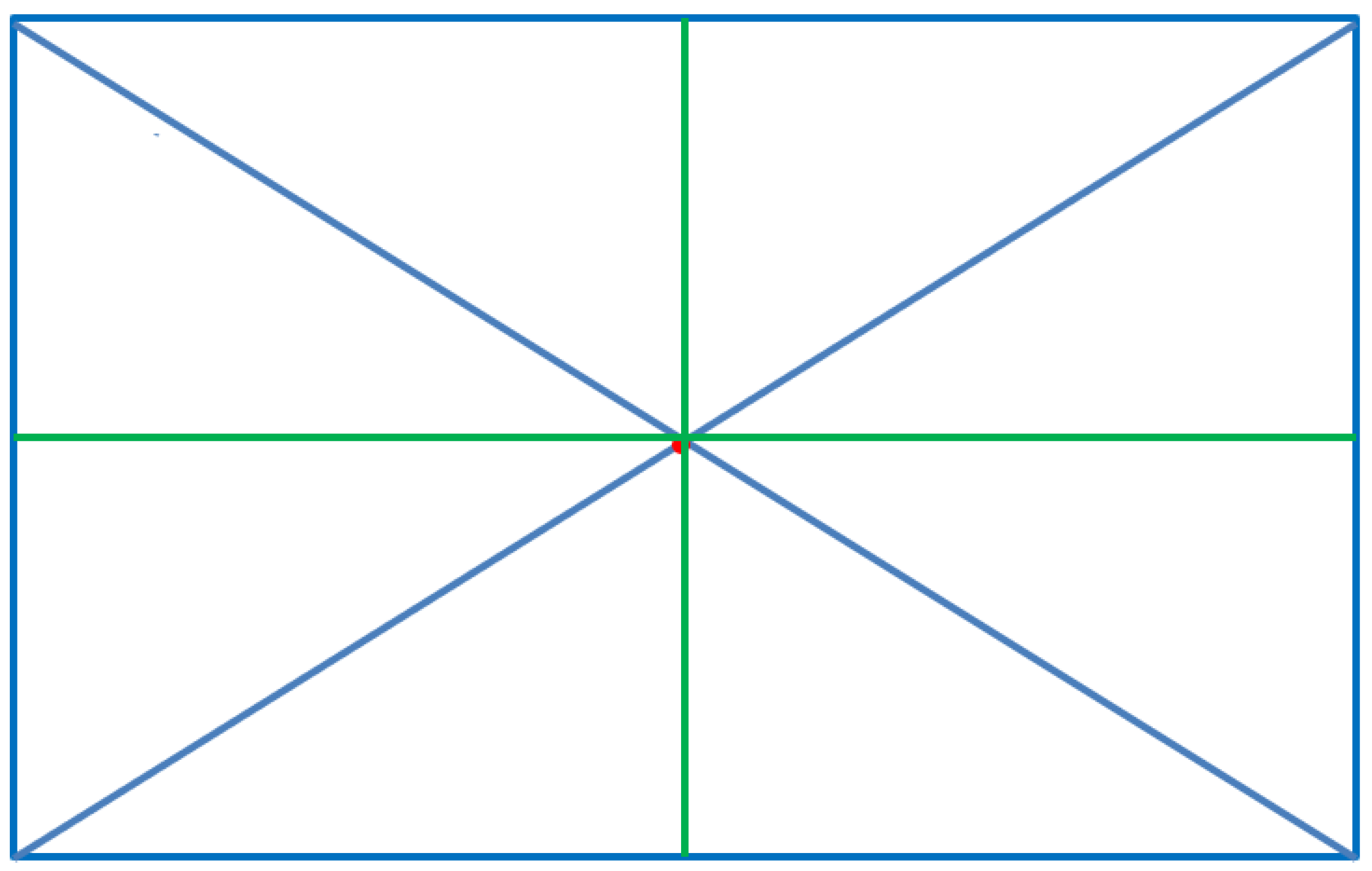

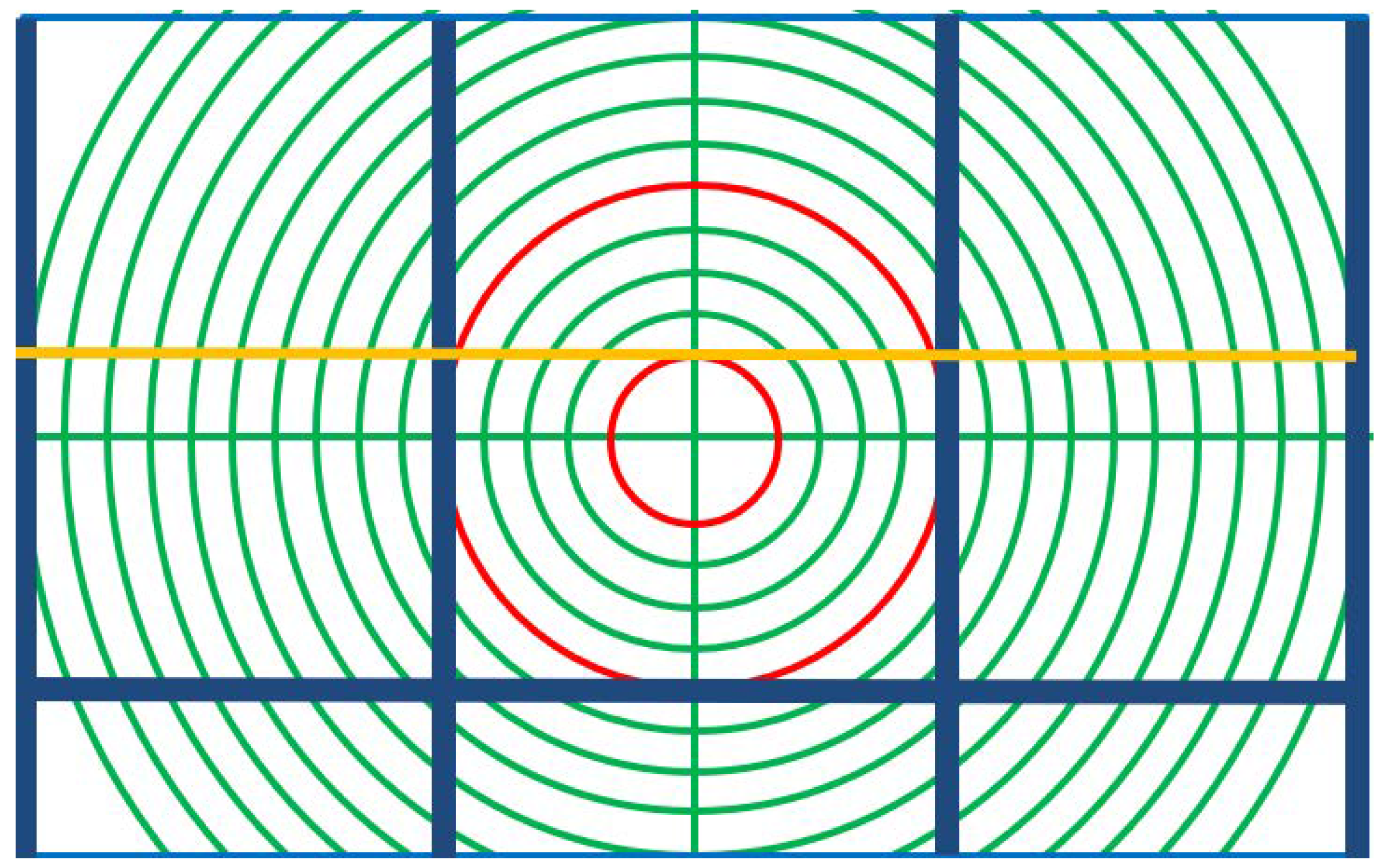

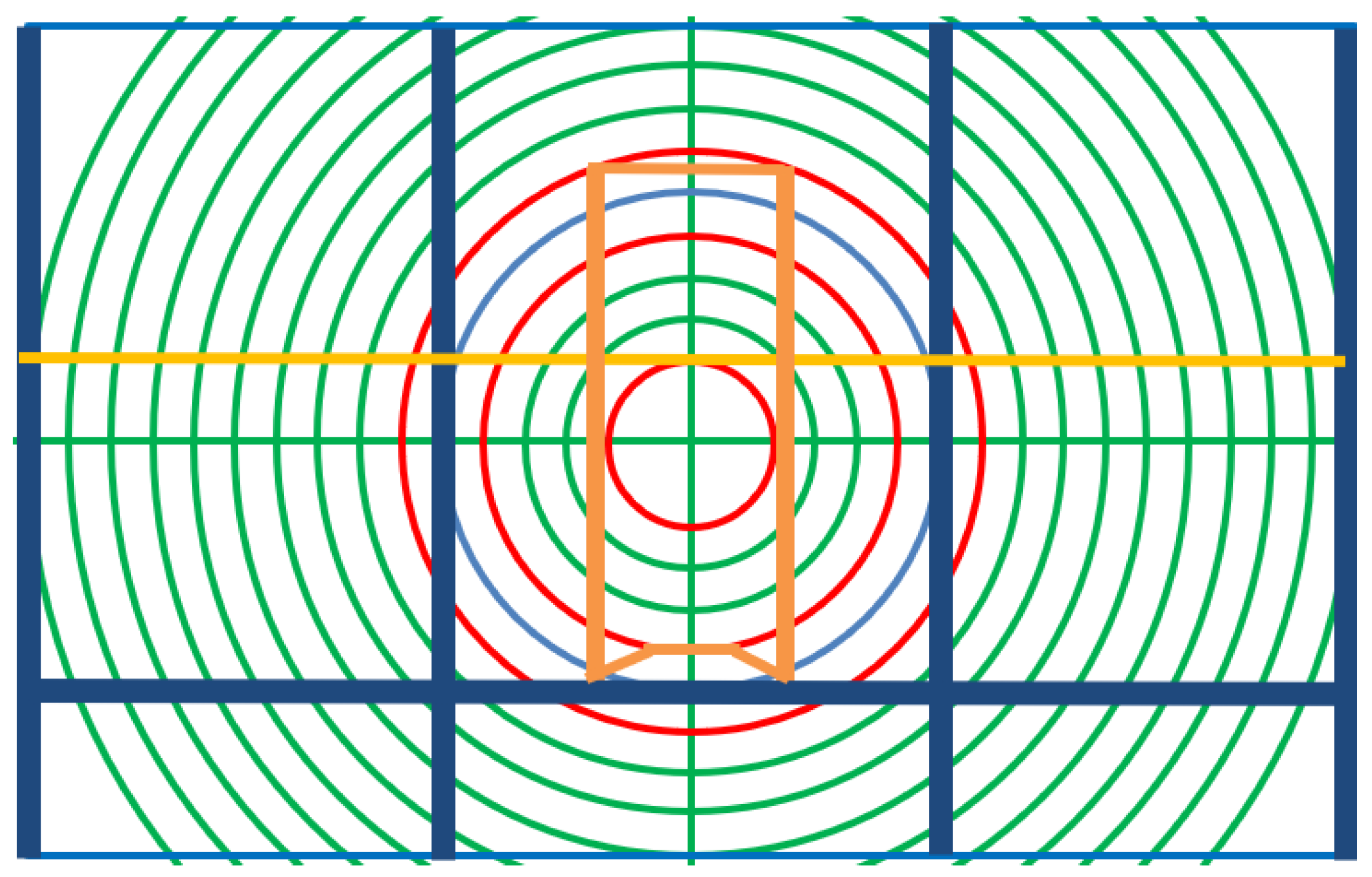

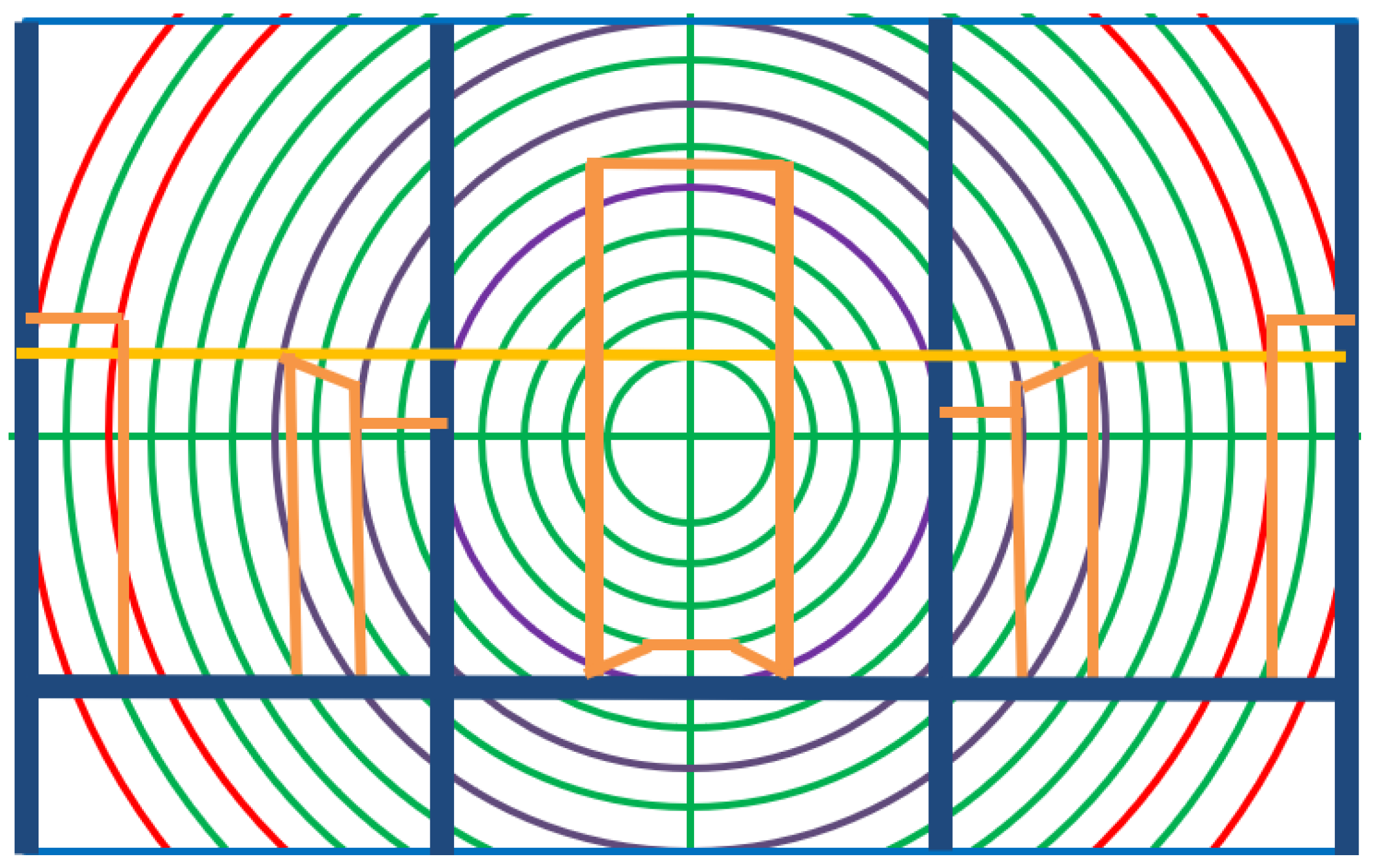

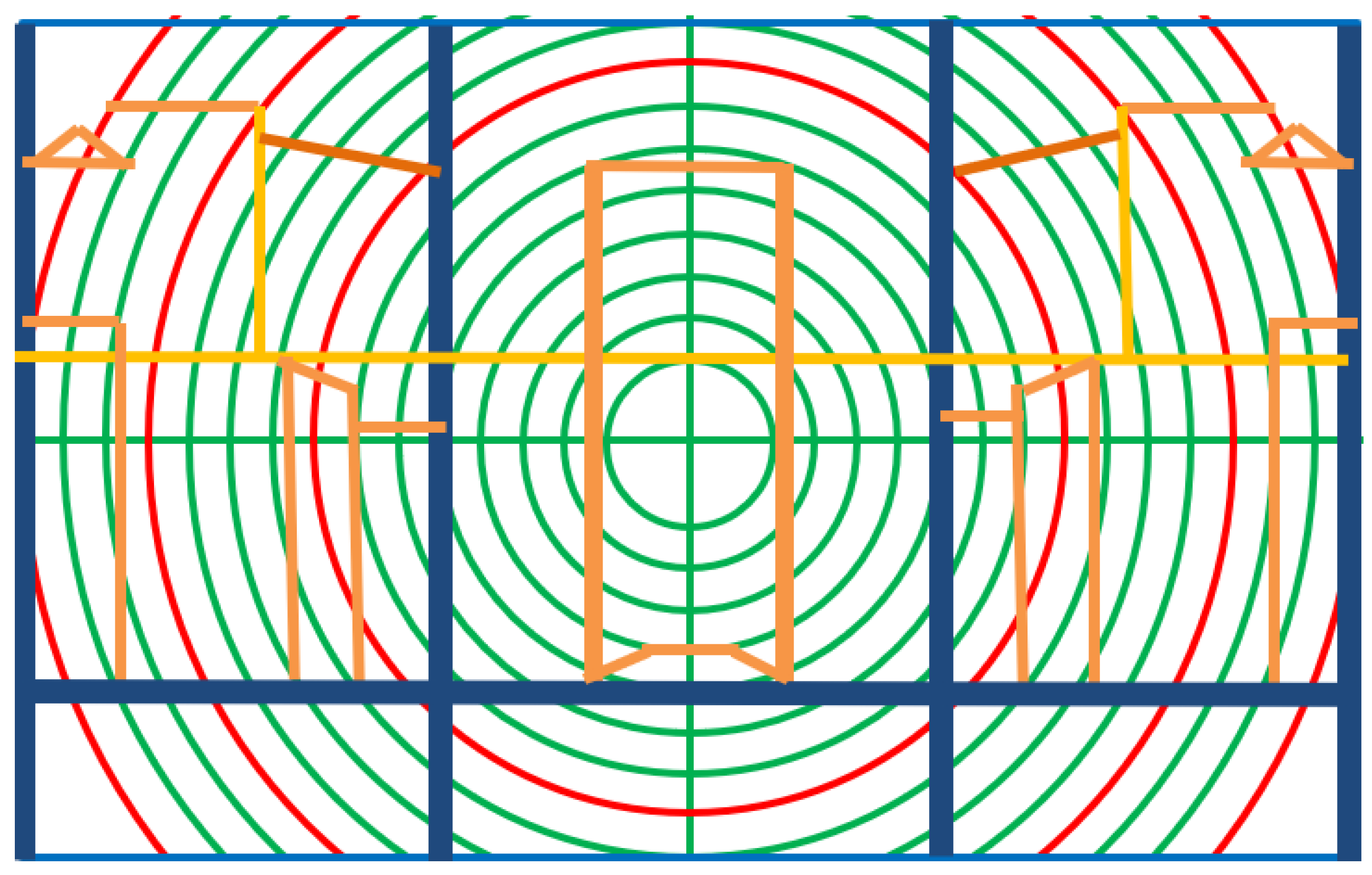

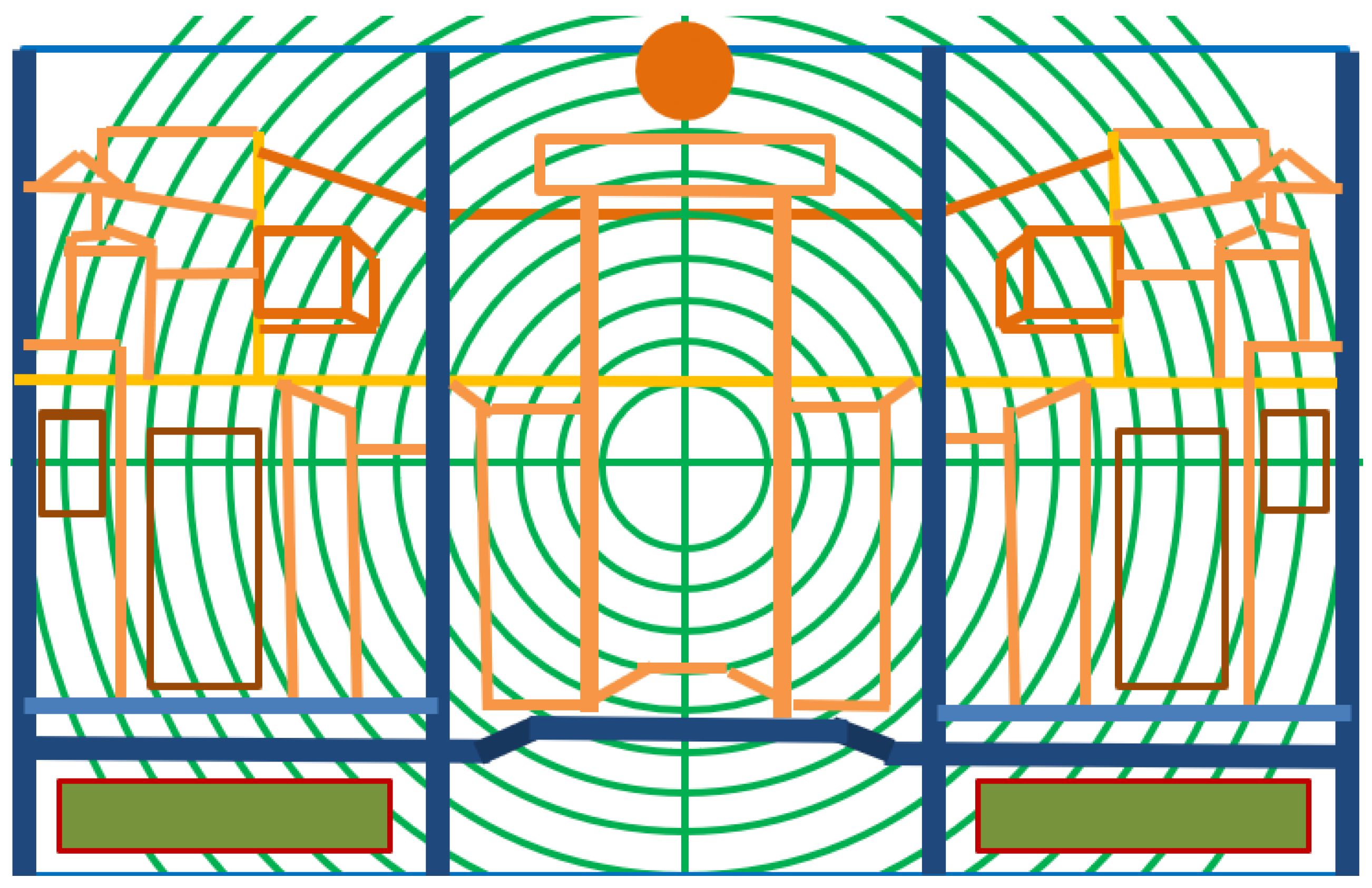

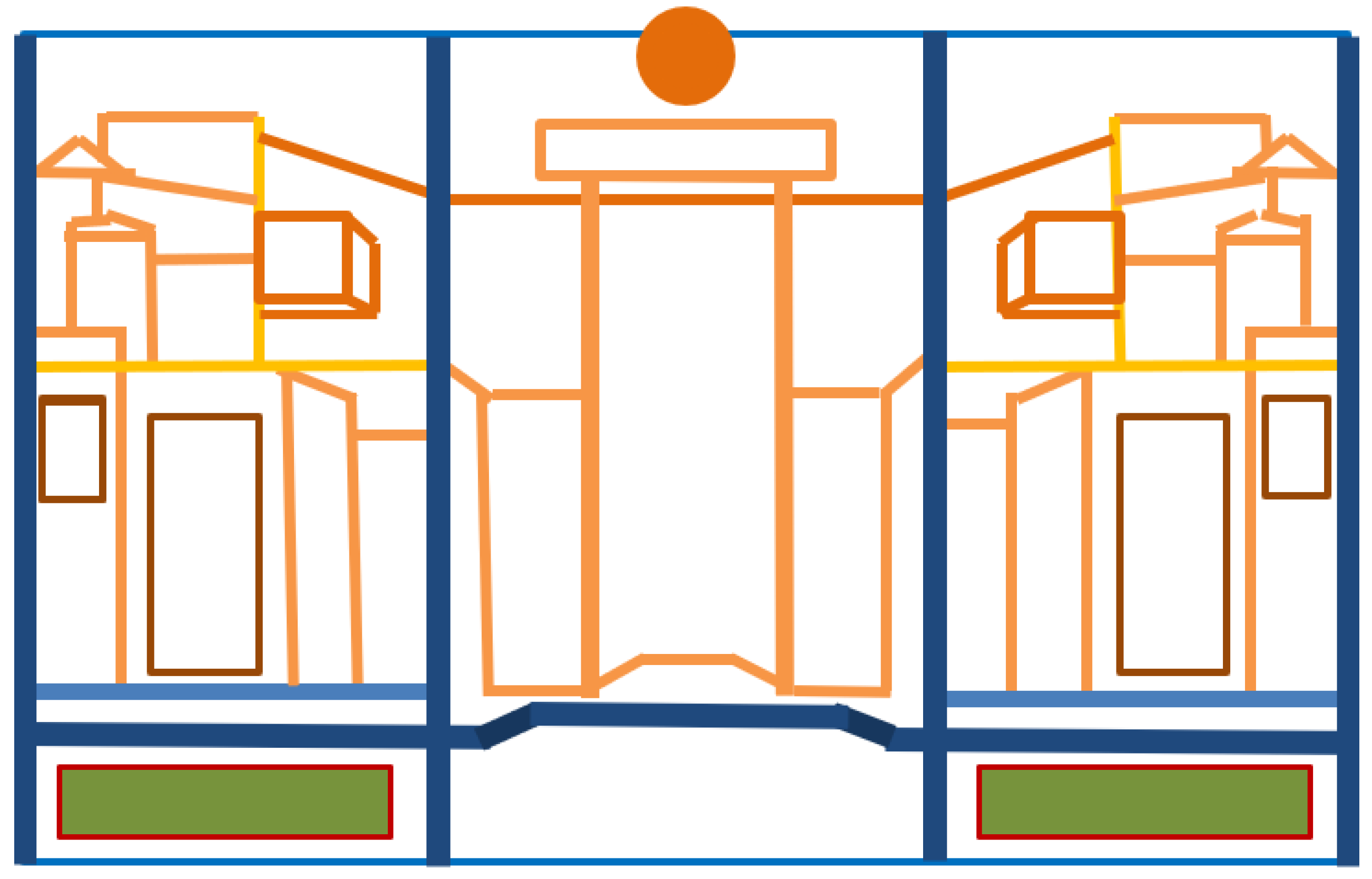

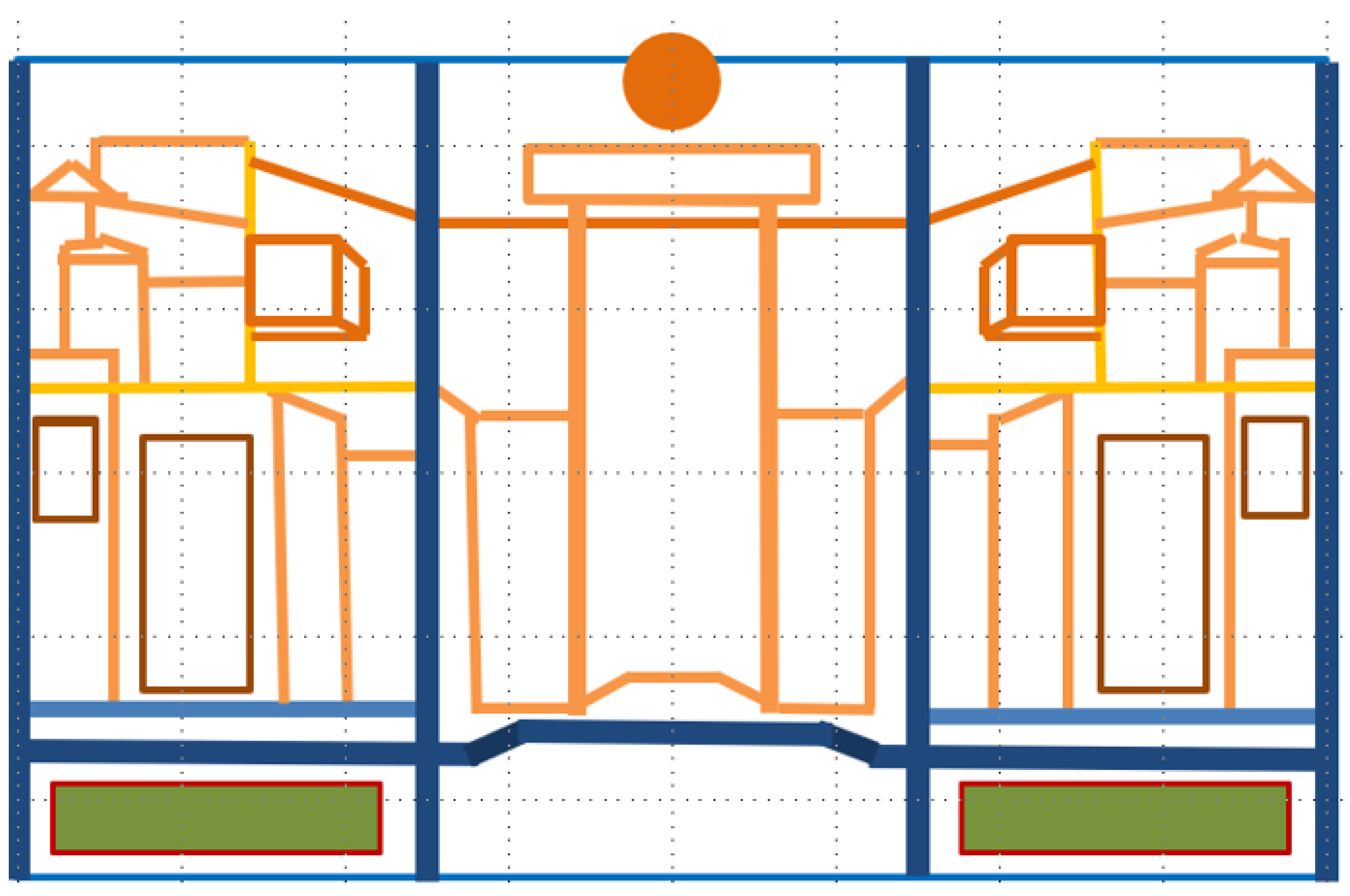

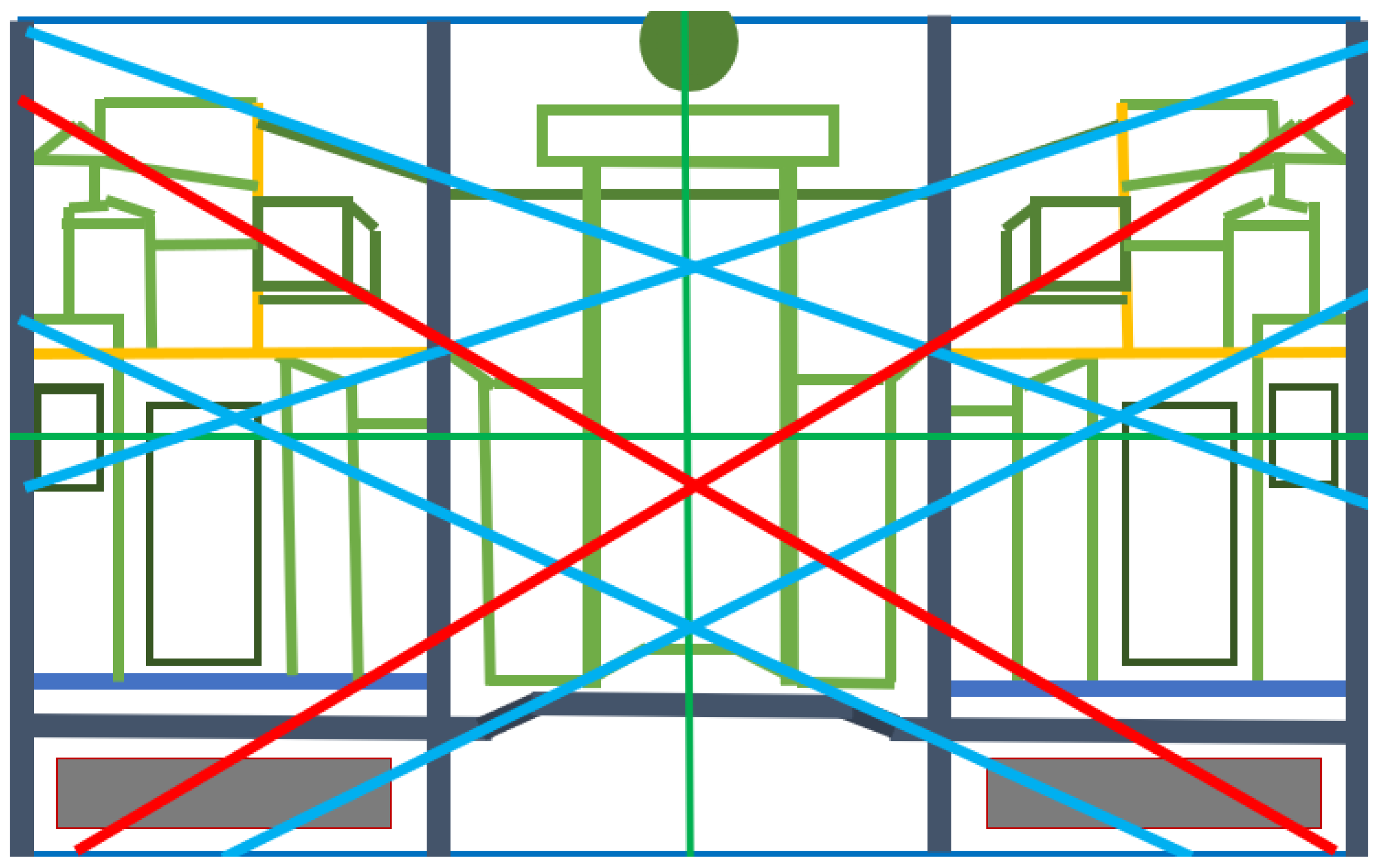

The last sentence refers to “perspective” and “planes”, as is common in modern translations—a very free interpretation of the Greek.52 Literally, however, the sentence says: “These are proportions [analogia], oh child. For it is necessary that the eyes be deceived, going back along the usual circles [kykloi].” Analogia, as I discussed above, concerns “size” in the sense of enlargement and diminution, based on a module, a circle in this case. Hence, Philostratus says that recession or depth was achieved not with linear perspective, but by using proportionate concentric circles. This method differs from the recession produced by shading and shadows. First, the concentric circles apply to the whole scene. Second, individual elements within a scene may also show shading.The clever artifice of the painter is delightful. Encompassing the walls with armed men, he depicts them so that some are seen in full figure, others with the legs hidden, others from the waist up, then only the busts of some, heads only, helmets only, and finally just spear-points. This, my boy, is perspective; since the problem is to deceive the eyes as they travel back along with the proper receding planes of the picture.51

5.2. The Circle Method of Design

- At no time did I need or use exact measurements. In PowerPoint, I copied each line segment on one side and then pasted it on the other side. In practice, a painter would mark a line segment from one side on a straight edge (or use a compass/calipers to measure the length) and place it in its equivalent circle on the other side of the central vertical divider.

- Because the system is modular, as Vitruvius recommends, copying a motif or design from one building to another, such as the wall from the cubiculum of Boscoreale and its twin in the House of the Labyrinth, is relatively simple.57 Scholars assume that grids were used to make the copies, but concentric circles also work well.

- I automated the process by reusing the same rectangles and circles for different walls. I did not test whether the Romans also did so.

- The system worked for all walls, no matter the style, no matter the shape (the narrow wall from the House of the Vettii vs. the other walls).

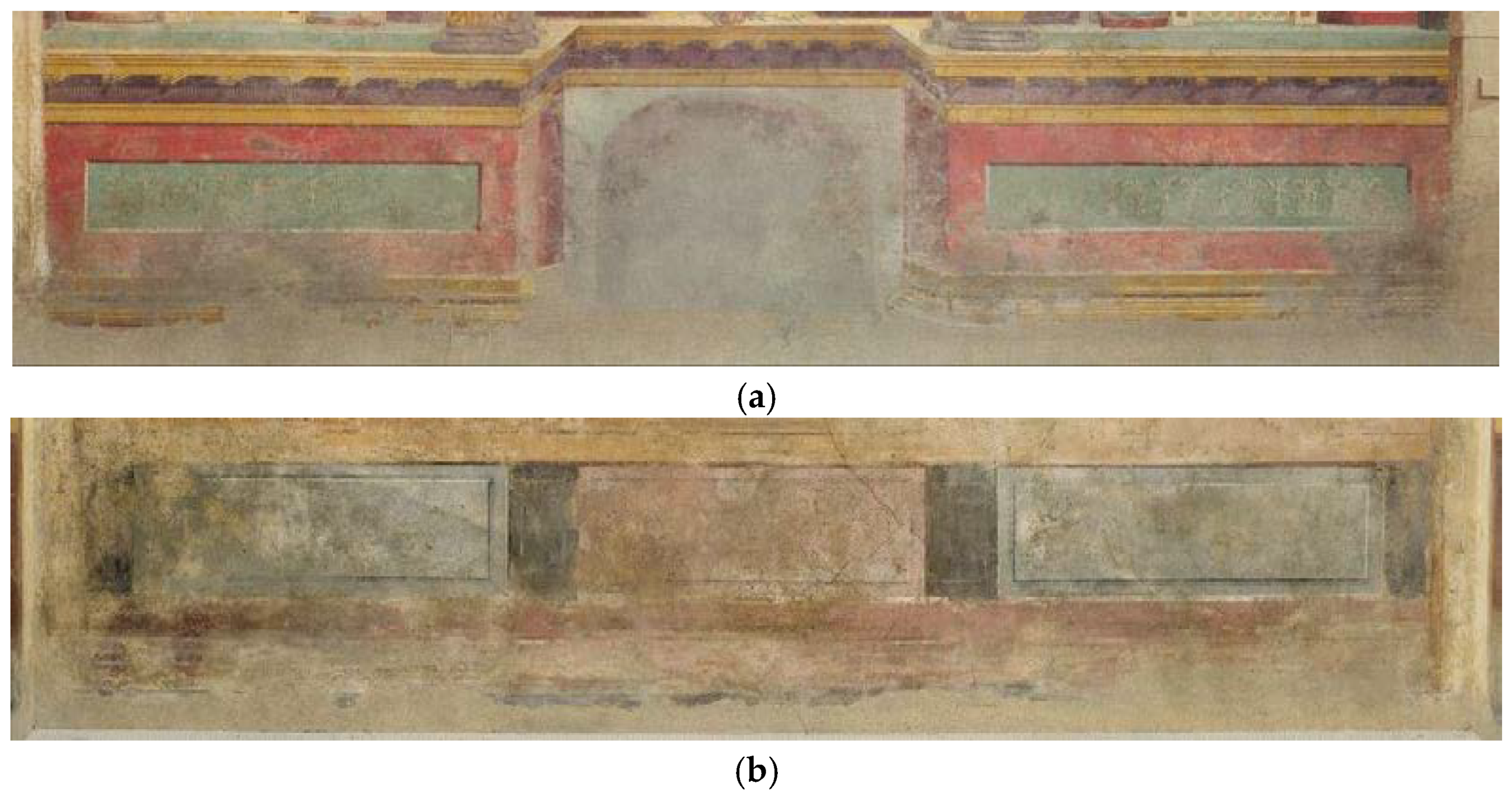

5.3. Variations as Before, I Use the Cubiculum from Boscoreale as My Example

5.3.1. Using Squares Instead of Circles

5.3.2. Grids

5.3.3. Other Applications of the Circle System

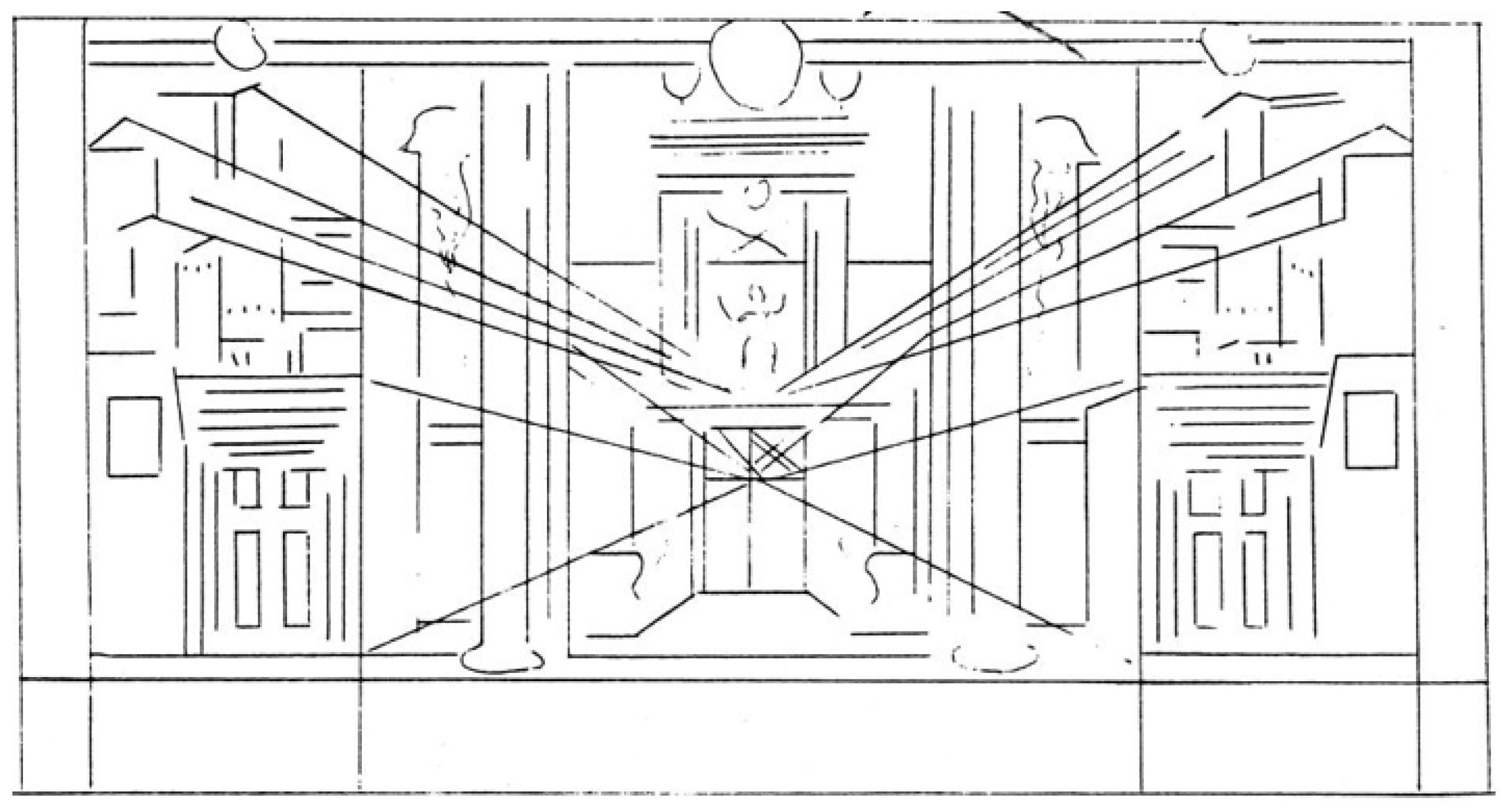

5.4. The Vertical Vanishing Axis

5.4.1. Facsimiles Using a Central Vertical Vanishing Axis

5.4.2. Drawing Diagonals for the Vertical Vanishing Axis over My Circle Reconstructions

5.5. Summary

6. Implications

7. Closing Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Funding

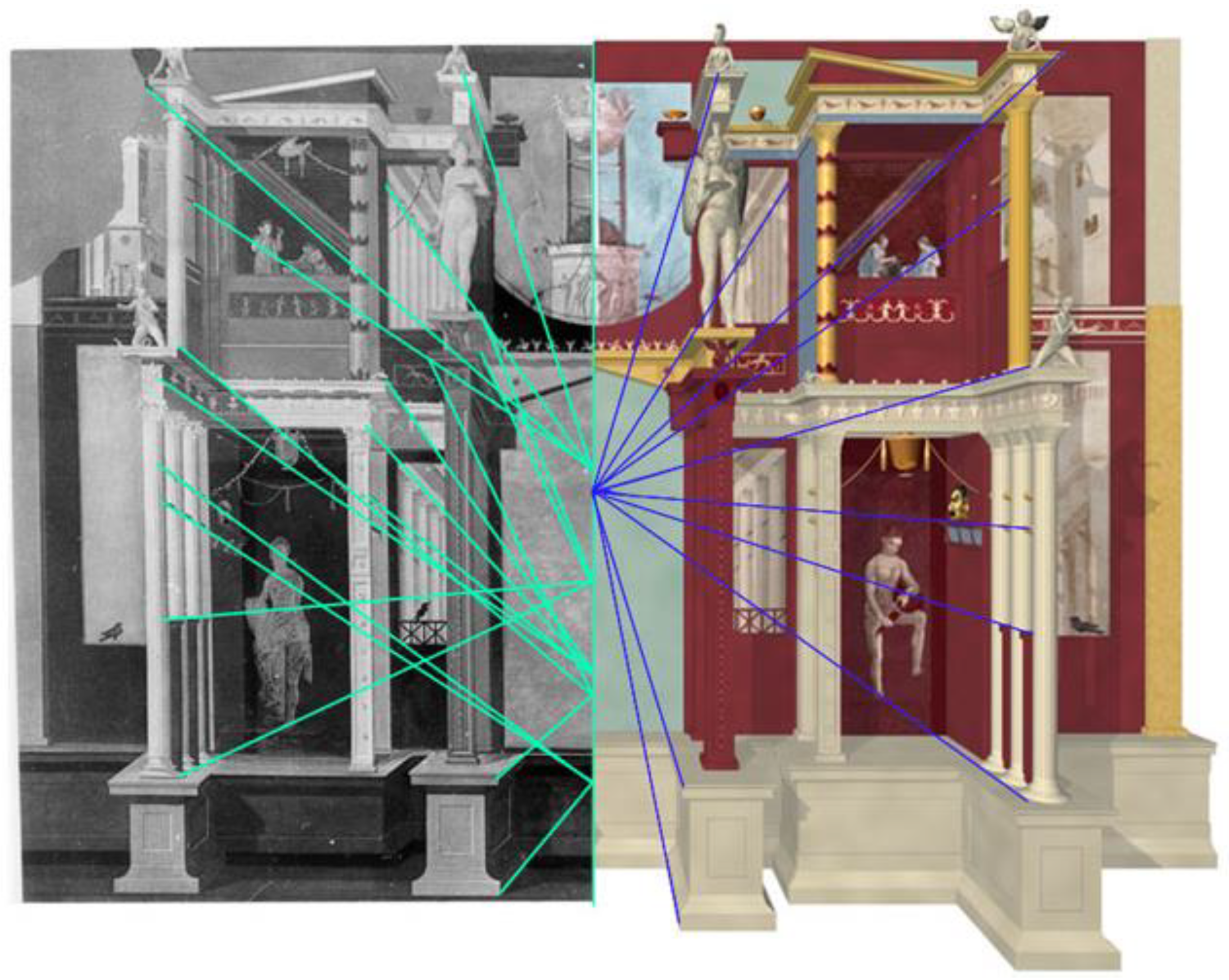

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Greek and Latin Passages

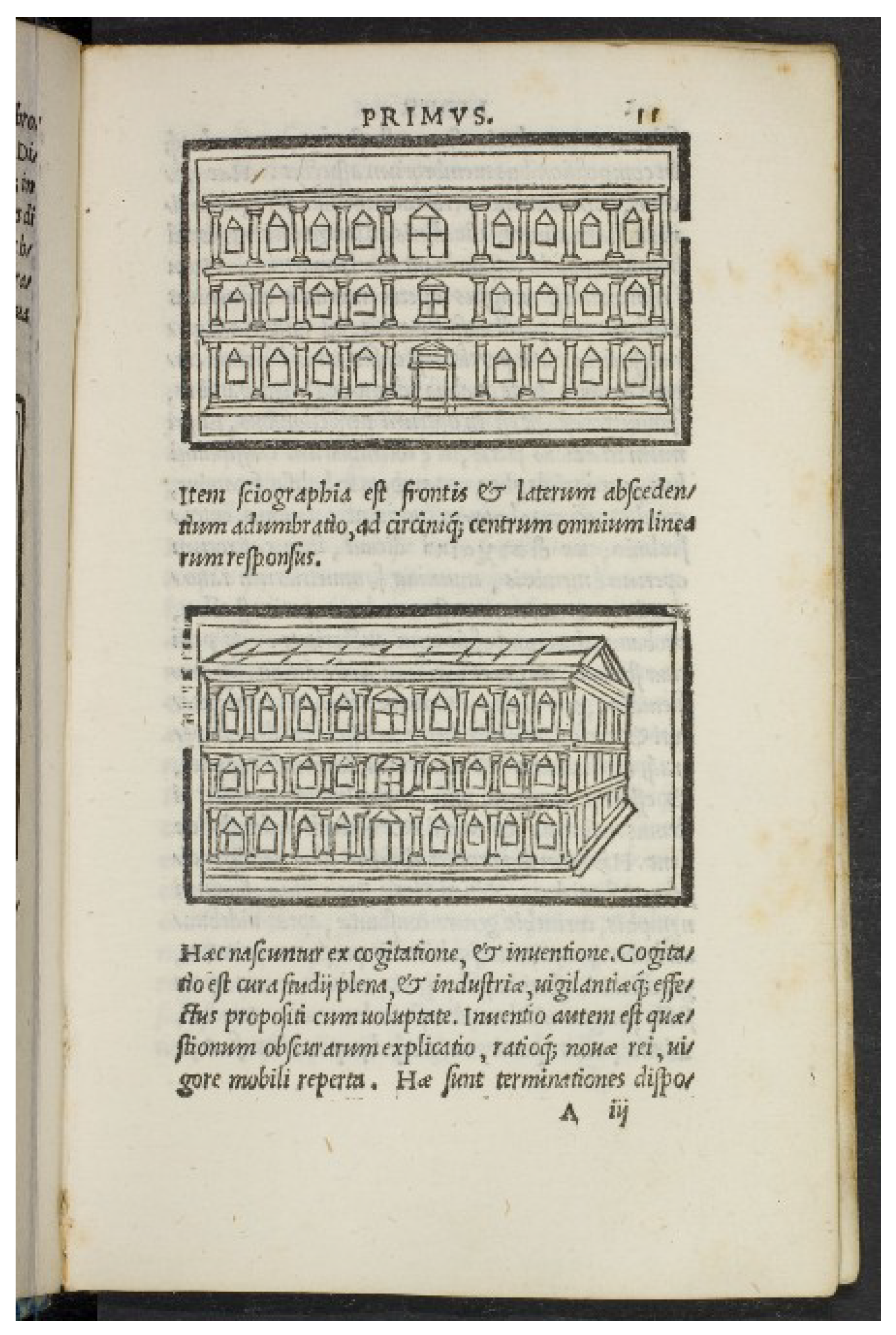

- Vitruvius, De architectura, 1.2.2 (Late first century BCE)Item scaenographia est frontis et laterum abscedentium adumbratio ad circinique centrum omnium linearum responsus.

- Vitruvius, De architectura, 7.Preface.11 (Late first century BCE)Namque primum Agatharchus Athenis Aeschylo docente tragoediam scaenam fecit et de ea commentarium reliquit. Ex eo moniti Democritus et Anaxagoras de eadem re scripserunt, quemadmodum oporteat ad aciem oculorum radiorumque extentionem certo loco centro constituto lineas ratione naturali respondere, uti de incerta re certae imagines aedificiorum in scaenarum picturis redderent speciem et, quae in directis planisque frontibus sint figurata, alia abscedentia, alia prominentia esse videantur.

- “Aristotle”, On Things Heard, 801a32–36 (4th–3rd c. BCE)καθάπερ οὖν καὶ ἐπὶ τῆς γραφῆς, ὅταν τις τοῖς χρώμασι τὸ μὲν ὅμοιον ποιήσῃ τῷ πόρρω τὸ δὲ τῷ πλήσιον, τὸ μὲν ἡμῖν ἀνακεχωρηκέναι δοκεῖ τῆς γραφῆς τὸ δὲ προέχειν, ἀμφοτέρων αὐτῶν ὄντων ἐπὶ τῆς αὐτῆς ἐπιφανείας.

- “Alexander” of Aphrodisias, Mantissa 15, 146.8–29 (3rd c. CE)[A] οὔτε γὰρ τὸ φῶς ὁμοίως ἐπὶ πάντα τὰ μόρια τοῦ ἀνωμάλου πίπτει διὰ τὸ τὰ μὲν αὐτῶν εἶναι κοῖλα, τὰ δὲ κυρτά, καὶ τὰ μὲν ἐκ πλαγίου τοῦ φωτίζοντος, τὰ δὲ καταντικρύ. διὰ γὰρ αύτας τὰς διαφοράς, κἂν ὁμοιόχρουν ᾖ τὸ ὁρώμενον, τὰ μὲν ἀχλυωδέστερα αὐτοῦ, τὰ δὲ εὐσημότερα φαίνεται, οὕτως δὲ τὰ μὲν εἰσέχοντα, τὰ δὲ ἐξέχοντα ὁραθήσεται. ὃ μιμούμενοι καὶ οἱ ζῳγράφοι, ὅταν βούλωνται ἄνισον δεῖξαι ἐν τῷ αὐτῷ ὂν ἐπιπέδῳ, τὰ μὲν φωτίζουσιν, τὰ δὲ ἐπισκιάζουσιν. οὕτω γὰρ τὰ μὲν ἐξέχοντα, τὰ δὲ εἰσέχοντα αὐτῶν φαίνεται, καὶ ἐξέχοντα μὲν τὰ μᾶλλον πεφωτισμένα, εἰσέχοντα δὲ τὰ ἐπεσκιασμένα. [B] μέγεθος δὲ ὁρᾷ καὶ κρίνει τῇ τοῦ κώνου γωνίᾳ τῇ πρὸς τῇ ὄψει συνισταμένῃ. κατὰ κῶνον γὰρ ὁρᾷ τὰ ὁρώμεναγωνίᾳ τῇ πρὸς τῇ ὄψει συνισταμένῃ. κατὰ κῶνον γὰρ ὁρᾷ τὰ ὁρώμενα κορυφὴν μὲν τὴν κόρην ἔχοντα, βάσιν δὲ τὴν ὁρίζουσαν γραμμὴν τό τε ὁρώμενον τοῦ αἰσθητοῦ σώματος καὶ μή. γίνεται δὲ ὁ κῶνος οὗτος οὐ κατὰ ἀκτίνων ἔκχυσιν, ἀλλ’ ἀπὸ τοῦ ὁρωμένου. τῆς γὰρ χρόας κινητικῆς οὔσης τοῦ κατ’ ἐνέργειαν διαφανοῦς καὶ τῆς ἐν τούτῳ γινομένης ὥσπερ χρώσεως ἐπ’ εὐθείας γινομένης. παραπλησίως τῷ φωτὶ παντί τε τῷ καταντικρὺ προσκαθημένης, μάλιστα δὲ τοῖς λείοις καὶ λαμπροῖς προσιζούσης τε καὶ προσλαμπούσης (τοιαύτη δὲ καὶ ἡ κόρη), συνίστανταί τινες πρὸς ταύτῃ κῶνοι ἀπὸ τοῦ ὁρωμένου, οἷοι τὴν ἔμφασιν δέχεσθαι τὴν ἀπ’ αὐτοῦ. κατὰ γὰρ κῶνον ἑκάστου τῶν ἐπ’ εὐθείας ὁρωμένων τὸ εἶδος τοῦ ὁρατοῦ ἐμφαίνεται. ὧν κώνων ταῖς γωνίαις τὰ μείζω καὶ τὰ ἐλάττω καὶ τὰ ἴσα κρίνει·NOTE: A and B indicate the division between parts quoted in my text. Furthermore, Section B includes the full Greek text of which I quoted only parts.

- Porphyry, Commentary on the Harmonics of Ptolemy, Düring 70 lines 10–14 (3rd c. CE)καθάπερ οὖν καὶ ἐπὶ τῆς γραφῆς, ὅταν τις τοῖς χρώμασι τὸ μὲν ὅμοιον ποιήσῃ τῷ πόρρω, τόδε τῷ πλησίον, τὸ μὲν ἡμῖν ἀνακεχωρηκέναι δοκεῖ τῆς γραφῆς, τὸ δὲ προέχειν, ἀμφοτέρων αὐτῶν ὄντων ἐπὶ τῆς αὐτῆς ἐπιφανείας, οὕτω καὶ ἐπὶ τῶν ψόφων καὶ τῆς φωνῆς·

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 35.29. (ca. 23–79 CE)Tandem se ars ipsa distinxit et invenit lumen atque umbras, differentia colorum alterna vice sese excitante. postea deinde adiectus est splendor, alius hic quam lumen. quod inter haec et umbras esset, appellarunt tonon, commissuras vero colorum et transitus harmogen.

- Philostratus, Imagines, 1.Proem.2.–10 (ca. 170–ca. 215 CE)ζωγραφία δὲ ξυμβέβληται μὲν ἐκ χρωμάτων, πράττει δὲ οὐ τοῦτο μόνον, ἀλλὰ καὶ πλείω σοφίζεται ἀπὸ τούτου [τοῦ] ἑνὸς ὄντος ἢ ἀπὸ τῶν πολλῶν <ἡ> ἑτέρα τέχνη. σκιάν τε γὰρἀποφαίνει …

- Lucretius, On the Nature of Things, 4.426–431 (ca. 98–55 BCE)Porticus aequali quamvis est denique ductustansque in perpetuum paribus suffulta columnis,longa tamen parte ab summa cum tota videtur,paulatim trahit angusti fastigia coni,tecta solo iungens atque omnia dextera laevisdonec in obscurum coni conduxit acumen.

- Euclid, Optics, Definition 2 (ca. 300 BCE)καὶ τὸ [μὲν] ὑπὸ τῶν ὄψεων περιεχόμενον σχῆμα εἶναι κῶνον τὴν κορυφὴν μὲν ἔχοντα ἐν τῷ ὄμματι τὴν δὲ βάσιν πρὸς τοῖς πέρασι τῶν ὁρωμένων.

- Plutarch, “On the Fame of the Athenians” [Moralia] 346a (45–ca. 125 CE)καὶ γὰρ Ἀπολλόδωρος ὁ ζωγράφος, ἀνθρώπων πρῶτος ἐξευρὼν φθορὰν καὶ ἀπόχρωσιν σκιᾶς, …

- Vitruvius, De architectura, 1.2.2 [immediately preceding No. 1 above] (Late first century BCE)Ordinatio est modica membrorum operis commoditas separatim universeque proportionis ad symmetriam comparatio. Haec componitur ex quantitate, quae graece poso/thj dicitur. Quantitas autem est modulorum ex ipsius operis membris sumptio e singulisque membrorum partibus universi operis conveniens effectus.

- Vitruvius, De architectura, 1.2.4 (Late first century BCE)Item symmetria est ex ipsius operis membris conveniens consensus ex partibusque separatis ad universae figurae speciem ratae partis responsus. Uti in hominis corpore e cubito, pede, palmo, digito ceterisque particulis symmetros est eurythmiae qualitas, sic est in operum perfectionibus.

- Vitruvius, De architectura, 3.1.1 (Late first century BCE)Aedum compositio constat ex symmetria, cuius rationem diligentissime architecti tenere debent. Ea autem paritur a proportione, quae graece analogia dicitur. Proportio est ratae partis membrorum in omni opere totoque commodulatio, ex qua ratio efficitur symmetriarum. Namque non potest aedis ulla sine symmetria atque proportione rationem habere compositionis, nisi uti ad hominis bene figurati membrorum habuerit exactam rationem.

- Vitruvius, De architectura, 3.1.9 (Late first century BCE)Ergo si convenit ex articulis hominis numerum inventum esse et ex membris separatis ad universam corporis speciem ratae partis commensus fieri responsum, relinqui-tur, ut suspiciamus eos, qui etiam aedes deorum inmorta-lium constituentes ita membra operum ordinaverunt, ut proportionibus et symmetriis separatae atque universae convenientes efficerentur eorum distributiones.

- Philostratus, Imagines, 1.4.2 (ca. 170–ca. 215 CE)ἡδὺ τὸ σόφισμα τοῦ ζωγράφου. περιβάλλων τοῖς τείχεσιν ἄνδρας ὡπλισμένους τοὺς μὲν ἀρτίους παρέχει ὁρᾶν, τοὺς δὲ ἀσαφεῖς τὰ σκέλη, τοὺς δὲ ἡμίσεας καὶ στέρνα ἐνίων καὶ κεφαλὰς μόνας καὶ κόρυθας μόνας, εἶτα αἰχμάς. ἀναλογία ταῦτα, ὦ παῖ· δεῖ γὰρ κλέπτεσθαι τοὺς ὀφθαλμοὺς τοῖς ἐπιτηδείοις κύκλοις συναπιόντας.

References

- Ackerman, James. 2000. Introduction: The Conventions and Rhetoric of Architectural Drawing. In Conventions of Architectural Drawing: Representation and Misrepresentation. Edited by James Ackerman and Wolfgang Jung. Cambridge: Harvard University, Graduate School of Design, pp. 7–36. ISBN 0935617507. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, Kirsti. 1987. Ancient Roots of Linear Perspective. In From Ancient Omens to Statistical Mechanics. Edited by J. Lennart Berggren and Bernard R. Goldstein. Acta Historica Scientiarum Naturalium et Medicinalium. Copenhagen: University Library, vol. 39, pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, Kirsti. 2007. The Geometry of an Art. The History of the Mathematical Theory of Perspective from Alberti to Monge. Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Architetura. n.d. Architecture, Textes et Images XVIe–XVIIe siècles: Books on Architecture—Vitruvius. Available online: http://architectura.cesr.univ-tours.fr/traite/Auteur/Vitruve.asp?param=en (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Aristotle. 1984. The Complete Works of Aristotle. The Revised Oxford Translation. Edited by Jonathan Barnes. Bollingen Series 71.2; Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- BAPD (Beazley Archive Pottery Database). n.d. Available online: http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/Pottery/ (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Barbet, Alix, and Annie Verbanck-Piérard, eds. 2013. La villa romaine de Boscoreale et ses fresques. 2 vols. Éditions Errance. Arles: Musée royal de Mariemont. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, Andrew. 2015. Porphyry’s Commentary on Ptolemy’s Harmonics: A Greek Text and Annotated Translation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bartman, Elizabeth. 1993. Carving the Badminton Sarcophagus. Metropolitan Museum Journal 28: 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Beare, John I. 1906. Greek Theories of Elementary Cognition. From Alcmaeon to Aristotle. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bek, Lise. 1993. From Eye-Sight to View-Planning: The Notion of Greek Philosophy and Hellenistic Optics as a Trend in Roman Aesthetics and Building Practice. Acta Hyperborea 5: 127–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bergman, Bettina, Stefano De Caro, Joan R. Mertens, and Rudolpf Meyer. 2010. Roman Frescoes from Boscoreale. The Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor in Reality and Virtual Reality. New York: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bragantini, Irene, and Valeria Sampaolo, eds. 2009. La pittura pomepiana. Naples: Mondadori Electa. [Google Scholar]

- Burnyeat, Myles F. 2017. All the world’s a stage-painting: Scenery, Optics, and Greek Epistemology. Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy 52: 33–75. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, Harry Edwin. 1945. The Optics of Euclid. Journal of the Optical Society of America 35: 357–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callebat, Louis, and Philippe Fleury, eds. 1995. Dictionnaire des termes techniques du De architectura de Vitruve. Zurich and New York: Georg Olms. ISBN 3-487-09398-7. [Google Scholar]

- Casati, Roberto. 2004. Shadows. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0-375-70711-5. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, John R. 1991. The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 B.C.—A.D. 250. Ritual, Space, and Decoration. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and Oxford: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07267-7. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, John R. 2009. How Did Painters Create Near-Exact Copies? Notes on Four Center Paintings from Pompeii. In New Perspectives on Etruria and Early Rome. Edited by Sinclair Bell and Helen Nagy. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 134–48. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, John R. 2013. Sketching and Scaling in the Second-Style Frescoes of Oplontis and Boscoreale. In La villa romaine de Boscoreale et ses fresques. Arles: Musée royal de Mariemont, vol. 2, pp. 198–209. [Google Scholar]

- Di Teodoro, Francesco P. 2002. Vitruvio, Piero della Francesca, Raffaello: Note sulla teoria del disegno di architettura nel Rinascimento. Annali di architettura 14: 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Elkins, James. 1991. The Case against Surface Geometry. Art History 14: 143–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombrich, Ernst Hans. 1973. Illusion and Art. In Illusion in Nature and Art. Edited by Richard Langton Gregory and Ernst Hans Gombrich. New York: Scribner, pp. 193–243. [Google Scholar]

- Gombrich, Ernst Hans. 1976. The Heritage of Apelles. London: Phaidon. ISBN 0714820113. [Google Scholar]

- Gros, Pierreand. 1990. ed. and trans. Vitruve de l’architecture. Livre III. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 2-251-01350-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, Vaughan, and Peter Hicks, eds. 1998. Paper Palaces. The Rise of the Renaissance Architectural Treatise. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hon, Giora, and Bernard R. Goldstein. 2008. From Summetria to Symmetry: The Making of a Revolutionary Scientific Concept. Archimedes 20. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-8447-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hub, Berthold. 2008. Die Perspektive der Antike. Archäologie einer symbolischen Form. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, Ludwig. n.d. Avian Visual Cognition: Visual Categorization in Pigeons. Available online: http://www.pigeon.psy.tufts.edu/avc/huber/default.htm (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Hui, Desmond. 1993. ICONOGRAPHIA, ORTHOGRAPHIA, SCAENOGRAPHIA: An analysis of Cesare Cesariano’s illustrations of Milan Cathedral in his commentary of Vitruvius, 1521. In Knowledge and/or/of Experience: The Theory of Space in Art and Architecture. Edited by J. Mcarthur. Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, pp. 77–97. ISBN 9781875792047. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, Martin, ed. 1989. Leonardo on Painting. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09095-1. [Google Scholar]

- Kiewig-Vetters, Gudrun. 2009. Trompe l’oeil in der Griechischen Malerei anhand ausgewählter Beispiele. Munich: GRIN. ISBN 978-3-640-33136-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, Geoffrey Steven, John Earl Raven, and Malcolm Schofield. 1983. The Presocratic Philosophers. A Critical History with a Selection of Texts, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner, Diana E. E. 1992. Roman Sculpture. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Latham, Ronald, trans. 1951. Lucretius. On the Nature of the Universe. Baltimore: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Loeb Classical Library. 1913. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Lehmann, Phyllis W. 1953. Roman Wall Paintings from Boscoreale in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Cambridge: Archaeological Institute of America. [Google Scholar]

- Liddell, Henry George, Robert Scott, H. S. Jones, and R. McKenzie. 1968. A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Little, Alan MacNaughton Gordon. 1971. Roman Perspective Painting and the Ancient Stage. Kennebunk: Star Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, Eric William. 1971. Greek and Roman Artillery. Technical Treatises. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-814269-2. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoleni, Donatella, and Umberto Pappalardo. 2004. Domus: Wall Painting in the Roman House. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. ISBN 0-89236-766-0. [Google Scholar]

- Montanari, Franco. 2015. The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek. Edited by Madeleine Goh and Chad Schroeder. English Edition. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- OED (Oxford English Dictionary). n.d. Available online: http://www.oed.com/ (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1991. Perspective as Symbolic Form. New York: Zone Books, Translated by Christopher S. Wood 1927. As “Die Perspektive als symbolische Form,” in Vorträge der Bibliothek Warburg 1924–1925. ISBN 0-942299-53-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Gómez, Alberto, and Louise Pelletier. 1997. Architectural Representation and the Perspective Hinge. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Plantzos, Dimitris. 2018. The Art of Painting in Ancient Greece. Athens: Kapon Editions. ISBN 978-618-5209-20-9. [Google Scholar]

- Pollitt, Jerome J. 1974. The Ancient View of Greek Art. Criticism, History, and Terminology. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pollitt, Jerome Jordan, ed. 2014. The Cambridge History of Painting in the Classical World. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86591-3. [Google Scholar]

- Raynaud, Dominique. 2016. Studies on Binocular Vision. Optics, Vision and Perspective from the Thirteenth to the Seventeenth Centuries. Archimedes 47. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, Gisela M. A. 1974. Perspective in Greek and Roman Art. London and New York: Phaidon. [Google Scholar]

- Rouveret, Agnès. 1989. Histoire et imaginaire de la peinture ancienne (Ve siècle av. J.-C.—Ier siècle ap. J.-C. Bibliothèque des Écoles françaises d’Athènes et de Rome, vol. 274. Rome: École française de Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Rouveret, Agnès. 2015. Painting and Private Art Collections in Rome. In A Companion to Ancient Aesthetics. Edited by Pierre Destrée and Penelope Murray. Chichester and Malden: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 109–206. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, Ingrid D. 1998. Vitruvius in Print and in Vernacular Translation: Fra Giocondo, Bramante, Raphael and Cesare Cesariano. Hart/Hicks 1998: 105–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, Ingrid D. 2014. Vitruvius and His Influence. In A Companion to Roman Architecture. Edited by Roger B. Ulrich and Caroline K. Quenemoen. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 412–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rowland, Ingrid D., and Thomas Noble Howe, eds. 1999. Ten Books on Architecture. Vitruvius. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rumpf, Andreas. 1947. Classical and Post-Classical Greek Painting. Journal of Hellenic Studies 67: 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rykwert, Joseph, Neil Leach, and Robert Tavernor, trans. 1988. Leon Battista Alberti: On the Art of Building in Ten Books. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saliou, Catherine, ed. 2009. Vitruve de l’Architecture. Livre 5. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 978-2-251-01453-1. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, Richard, trans. 2009. Vitruvius. On Architecture. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Senseney, John R. 2011. The Art of Building in the Classical World. Vision, Craftsmanship, and Linear Perspective in Greek and Roman Architecture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sharples, Robert W., trans. 2004. Alexander of Aphrodisias. Supplement to “On the Soul”. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, Gérard. 1987. Behind the Mirror. Graduate Faculty Philosophy Journal 12: 311–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, Gérard. 2003. Archéologie de la vision. L’optique, le corps, la peinture. Paris: Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Skenographia Project. n.d. King’s Visualisation Lab. Available online: http://www.skenographia.cch.kcl.ac.uk/index.html (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Small, Jocelyn Penny. 1999. Time in Space: Narrative in Classical Art. Art Bulletin 81: 562–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, Jocelyn Penny. 2009. Is Linear Perspective Necessary? In New Perspectives on Etruria and Early Rome. Edited by Sinclair Bell and Helen Nagy. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 149–57. [Google Scholar]

- Small, Jocelyn Penny. 2012. Attic Vases, Curves, and Figures. Eirene 48: 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Small, Jocelyn Penny. 2013. Skenographia in Brief. In Performance in Greek and Roman Theatre. Edited by George M. W. Harrison and Vayos Liapis. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 111–28. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. Mark. 2015. From Sight to Light. The Passage from Ancient to Modern Optics. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Squire, Michael. 2010. Making Myron’s cow moo?: Ecphrastic epigram and the poetics of simulation. American Journal of Philology 131: 589–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansbury-O’Donnell, Mark. 2014. Reflections of Monumental Painting in the Fifth and Fourth Centuries B.C. Pollitt 2014: 143–69. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson, Philip. 2011. Perspective Systems in Roman Second Style Wall Painting. American Journal of Archaeology 115: 403–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, David. 2018. Emphasis. On Light, Dark, and Distance. In Chiaroscuro als Ästhetisches Prinzip: Kunst und Theorie des Helldunkels 1300–1550. Edited by Claudia Lehmann, Norberto Gramaccini, Johannes Rößler and Thomas Dittelbach. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 165–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, Jeremy. 2016. Sight and Painting: Optical Theory and Pictorial Poetics in Classical Greek Art. In Sight and the Ancient Senses. Edited by Michael Squire. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 107–22. [Google Scholar]

- Thibodeau, Philip. 2003. Optical Illusions in Ancient Greece. In Gestures: Essays in Ancient History, Literature, and Philosophy Presented to Alan L. Boegehold. Edited by Geoffrey W. Bakewell and James P. Sickinger. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 136–51. [Google Scholar]

- Thibodeau, Philip. 2016. Ancient Optics: Theories and Problems of Vision. In A Companion to Science, Technology, and Medicine in Ancient Greece and Rome. Edited by Georgia L. Irby. Chichester and Malden: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 130–44. [Google Scholar]

- Vagnetti, Luigi, and Laura Marcucci. 1978. Per una coscienza Vitruviana. Regesto cronologico e critico. Studi e documenti di architettura 8: 3–184. [Google Scholar]

- Vescovini, Graziella Federici. 2000. A New Origin of Perspective. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 38: 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitruviana. n.d. Stiftung Bibliothek Werner Oechslin—Vitruviana. Available online: https://www.bibliothek-oechslin.ch/bibliothek/online/vitruviana (accessed on 1 April 2019).

- Vitruvius Budé. 1969–2009. Vitruve, De l’architecture. Edited by Budé. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, vol. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, Shigeru. 2001. Van Gogh, Chagall and Pigeons: Picture Discrimination in Pigeons and Humans. Animal Cognition 4: 147–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, Shigeru, Junko Sakamoto, and Masumi Wakita. 1995. Pigeon’s Discrimination of Paintings by Monet and Picasso. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior 63: 165–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, John. 1987. The Birth and Rebirth of Pictorial Space, 3rd ed. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-07475-0. [Google Scholar]

- Willats, John. 1997. Art and Representation. New Principles in the Analysis of Pictures. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Willats, John. 2002. The Rules of Representation. In A Companion to Art Theory. Edited by Paul Smith and Carolyn Wilde. Chichester and Malden: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 411–24. ISBN 0631207627. [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans, David. 2011. The Geometry of a Piece of String. Architectural History 54: 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | This topic is remarkably complex with a massive bibliography. Small (2013) provides a reasonable summary of the scholarship to its date of publication. Since then, I have realized that the standard interpretations of key texts and objects needs to be totally rethought. This article, drawn from my book in progress, is the result. Unless otherwise noted, the translations are mine. |

| 2 | For example, for linear perspective in Antiquity: (Pollitt 1974, 2014; White 1987; Rouveret 1989, 2015; Senseney 2011; Stinson 2011; Stansbury-O’Donnell 2014; Smith 2015; Tanner 2016; Burnyeat 2017). For example, against linear perspective in Antiquity: (Lehmann 1953; Richter 1974; Pérez-Gómez and Pelletier 1997, pp. 97–111; Plantzos 2018). |

| 3 | Thibodeau (2003, p. 146 n. 43), also with literary references. This is an excellent article on optical illusions. |

| 4 | Willats (2002, p. 412). Raynaud (2016, pp. 133–60), among many others, discusses alternative systems in Medieval art. |

| 5 | (OED (n.d.)), s.v. “perspective”. For full discussion: (Raynaud 2016, pp. 1–12). For medieval usage: (Vescovini 2000). |

| 6 | LSJ 1608 and BDAG 1924–1925, both s.v. “σκηνογραφία” and related words (Liddell et al. 1968; Montanari 2015). |

| 7 | Hesychius, s.v. “σκιαγραφός”. Intermediary steps led to the equation of the two words. For example, in the late fourth–early fifth century CE, Servius (ad Vergil, Aeneid 1.164) erroneously (from a modern point of view) claimed that “scaena/skene” came from “skia”. On skiagraphia, among many, see (Rouveret 1989, pp. 13–63). |

| 8 | The idea of a vanishing vertical axis was first proposed by G. Joseph Kern, as Panofsky (1991, pp. 102–5 notes 20–22) acknowledges. |

| 9 | Vitruvius’ treatise originally had no title. Its description as “ten books on architecture”, often shortened to “on architecture”, has evolved into a formal title today. See (Rowland and Howe 1999, p. 1). For background, see (Raynaud 2016), who cogently considers the evidence, especially Panofsky’s (1991) idea of a vanishing vertical axis. Hart and Hicks (1998) provide a good introduction to early Renaissance printed books and include one of Rowland’s (1998) many articles on Vitruvius. Also see Rowland’s (2014) useful overview. For a detailed history of “perspective” in the scholarly literature, see (Hub 2008). |

| 10 | He is the sole classical source for ichnographia. Orthographia generally referred to “correctness of writing” and “orthography” rather than Vitruvius’ literal interpretation of its two roots as “straight/upright drawing”, on which BDAG (Montanari 2015), s.v. ὀρθογραφία; and (Callebat and Fleury 1995, col. 72 [all three words], 359 and 368). This book is essential for anyone studying Vitruvius’ vocabulary. The Vitruvius Budé (1969–2009) with excellent annotated volumes for every book in Vitruvius is indispensable. |

| 11 | Appendix A gives the original Greek and Latin for sources discussed in my text. |

| 12 | Early translations sometimes used “scaenographia”, sometimes “sciographia” with various spellings. For example Fra Giocondo’s 1511 edition used “scenographia”, his 1522 edition changed it to “sciographia”, but his 1523 edition returned to “scenographia”. Di Teodoro (2002) analyzes the various changes undergone by Vitruvius’ sentence with a helpful chart of who said what, when (p. 48). Virtually every early printed edition of Vitruvius can be downloaded for free. Two excellent websites are the following: Architetura (n.d.) and Vitruviana (n.d.). Vagnetti and Marcucci (1978) catalogued all 166 printed editions from 1486 until 1976. |

| 13 | Latin used two words, lumen and umbra (light and shade), for skiagraphia. See (Pollitt 1974, p. 252). |

| 14 | Burnyeat (2017) is the best article on the textual problems of the first half of this passage. His discussion of art historical matters adheres to the standard view of the linear perspectivists. Also see Rouveret’s (1989, pp. 13–127) extensive discussion of both skiagraphia and skenographia B, to which she has returned in several articles. Recently see (Stansbury-O’Donnell 2014, pp. 155–60; Tanner 2016). |

| 15 | Translation adapted from Aristotle (1984, vol. 1, p. 1231). I changed the last clause, because, when we read “are really in the same plane”, we automatically and anachronistically think of linear perspective, even though “plane” in and of itself need not refer to a “picture plane”. In short, “plane” here is not the “picture plane”, but the “[plane] surface of the object itself”. |

| 16 | “Section A”. Translation from (Sharples 2004, pp. 136, 139–40). All words in brackets are from Sharples’ translation. Philoponus, in his commentary on Aristotle’s Meteorology 374b14–15, is similar; see (Summers 2018, pp. 169–70). |

| 17 | “Section B”. For translation, see previous note. |

| 18 | (Simon 1987, p. 316; Simon 2003, pp. 17–42). Some scholars believe that Euclid’s Optics (Definition 4 and Theorem 10) supports the existence of linear perspective in antiquity: (Smith 2015, pp. 47–72). Others, however, maintain that Euclid says nothing about linear perspective: (Andersen 1987, 2007, pp. 724–25). She provides very clear explanations of Euclid’s theorems. Philip Thibodeau (2016) presents an excellent survey of classical optics. |

| 19 | On projection and recession, compare: Longinus, On the Sublime 17.3. Plutarch, On the Malice of Herodotus = Moralia 863 E; Moralia, Aratus Fragment 14; Moralia 57c “How to tell a flatterer”. Lucian, Zeuxis or Antiochus 5.3–5.8. Porphyry, Commentary on the Harmonica of Ptolemy, 70 line 12. Philostratus, Life of Apollonius, 2.20. |

| 20 | Translation from (Barker 2015, p. 231). |

| 21 | Translation (and italics) from (Pollitt 1974, p. 399 No. 2). See his discussions (pp. 439–441 and 399–400) on “splendor” and “lumen et umbra”. |

| 22 | On splendor, see (Gombrich 1976, pp. 1–18, especially p. 9). Rumpf (1947, p. 14) puts it well: “They [scholars] had only to ask a lady who powdered her nose what was the difference between lumen and splendor, between light and shine.” |

| 23 | Translation from (LCL 1913, pp. 3, 5). |

| 24 | For Anaxagoras: Sextus Empiricus, Against the Logicians 1.90; Theophrastus, On the senses, 27. On eclipses, see (Kirk et al. 1983, pp. 380–82 No. 502 = DK 59A42 = Hippolytus Ref. 1.8.3–10; Beare 1906, pp. 37–40; Casati 2004, pp. 62, 72–73). For Democritus: (Kirk et al. 1983, pp. 428–29). Beare (1906, pp. 23–37) on shadows and colors. For an accessible scientific discussion of shadows, see Casati, passim. |

| 25 | Translation from (Latham 1951, p. 143). |

| 26 | Translation from (Burton 1945, p. 357). For the definition as “apex of a cone”, see (Liddell et al. 1968, p. 983, s.v. κορυφή 4). |

| 27 | |

| 28 | Boston, Museum of Fine Arts 1900.03.804. https://collections.mfa.org/objects/154078/mixing-bowl-volute-krater?ctx=d78bcef0-adc8-46b5-8ebf-b004a0db5fd8&idx=4 (Plantzos 2018, p. 162 Figures 155–56). The Apulian fragment in Würzburg (Martin von Wagner Museum Inv. H 4696/4701)—the most frequently cited example—has similar problems (Plantzos 2018, p. 163 Figure 157). |

| 29 | |

| 30 | Zeuxis’ grapes: Pliny, Natural History, 35.65. Other examples from accounts of Greek art include the following: horses neighing at Apelles’ painted horse (ibid., 35.95) and cows mooing at Myron’s cow, on which see (Squire 2010), with full references. Leonardo da Vinci recalls a dog recognizing a portrait of his master, for which see (Kemp 1989, p. 34). According to Gombrich (1973, p. 194), Goethe called it “sparrow aesthetics”. Compare: (Kiewig-Vetters 2009). For an excellent survey of classical visual illusions, see (Thibodeau 2003). Modern research has established that animals, or at least pigeons, can be trained to impeccably distinguish between two painters (Picasso and Monet). Watanabe et al. (1995); Watanabe (2001); and Huber (n.d.)’s website: Avian Visual Cognition. |

| 31 | Compare Leonardo Da Vinci, who said that “The first intention of the painter is to make a flat surface display a body as if modelled and separated from this plane. … This accomplishment … arises from light and shade, or we may say chiaroscuro” (Kemp 1989, p. 15). |

| 32 | For color photographs: (Bergmann et al. 2010, pp. 31–32 Figures 55–57). For the most extensive documentation, see (Barbet and Verbanck-Piérard 2013). For full set of color photographs: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/247017. |

| 33 | Translation from Plantzos (2018, p. 129), who uses “shading” rather than “chiaroscuro” as in the LCL Plutarch, Moralia 4.495. Plantzos (2018) has an excellent discussion about shading and shadows—a topic that he emphasizes throughout his study. The main discussion begins on 129ff. |

| 34 | |

| 35 | For examples of Attic white-ground vases, see, among others, (Plantzos 2018, pp. 124–31). |

| 36 | Attic red-figure kylix by the Foundry painter. Munich, Antikensammlungen, 2640. Interior: Lapith fighting Centaur. Hatching is on the Lapith’s shield. BAPD 204363. |

| 37 | Telemachus and Penelope on an Attic red-figure skyphos by the Penelope Painter, ca. 440 BC. Chiusi, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, C 1831. BAPD 216789 (Plantzos 2018, pp. 148–49 Figures 145–46). |

| 38 | Plantzos (2018, pp. 187–89) similarly comments on the gradual process. |

| 39 | The geometric decoration of Room 2 in the House of the Griffins in Rome may be an exception (Mazzoleni and Pappalardo 2004, pp. 67, 74–76). Richter (1974, p. 2) maintained that “A perspective drawing, therefore, can be produced merely by correct observation by an artist … without any knowledge of the laws underlying this phenomenon [linear perspective].” |

| 40 | This reconstruction was produced by Martin Blazeby for the Skenographia Project (n.d.) of the King’s Visualisation Lab. http://www.skenographia.cch.kcl.ac.uk/crypto/3dvis/3d02.html. |

| 41 | For example, (Senseney 2011, p. 4) as part of the book’s thesis. |

| 42 | Despite frequent use of bilateral symmetry, Greek and Latin had no specific word to label the phenomenon. Bek (1993, p. 148 n. 10) credits Luca Pacioli (1447–1517) as the first to use symmetria in our sense of “symmetry”. For a history of symmetria/symmetry, see (Hon and Goldstein 2008). |

| 43 | Translation and bolding of words from (Rowland and Howe 1999, p. 47). |

| 44 | Philon of Byzantium, last third of the third century BC, gives explicit directions on using modules for scaling. He thought that taking exact measurements of each part was “exceedingly awkward, slow, and not too accurate.” From the Belopoeica, 55–56; translation from (Marsden 1971, pp. 115, 117) and commentary on (162–63 nn. 39–40). |

| 45 | “Respondeo” in various forms occurs in 3.1.3, 4, and 9. |

| 46 | Translation from (Schofield 2009, p. 69). I have substituted symmetria from the Latin for Schofield’s “modularity”. |

| 47 | On Cesariano in general: (Rowland 1998, pp. 111–21). For one of the best analyses of Caesarino’s skenographia, see (Hui 1993). |

| 48 | Also see: http://numismatics.org/ocre/id/ric.1(2).ner.512. A relief from the “Ara Pietatis”, ca. AD 43, similarly depicts the Temple of Magna Mater (Kleiner 1992, p. 143 Figure 119). |

| 49 | Ackerman (2000, p. 16). Isometric and axonometric drawings solve the problem of representing structures as three-dimensional while retaining accurate measurements. Both were introduced in the nineteenth century (Willats 1997, pp. 55–59). |

| 50 | On the importance of the compass and its role in Vitruvius, see (Saliou 2009, pp. 222–33). |

| 51 | Translation from LCL; my italics. I especially thank Susan Woodford for bringing this passage to my attention. |

| 52 | |

| 53 | I am particularly grateful to Harrison Eiteljorg, II for suggesting that I try the system. |

| 54 | Sinopia refers both to the color, a reddish-brown, and to the “guidelines painted on the penultimate layer of plaster” (Clarke 1991, p. 4). |

| 55 | Alberti, On the Art of Building 3.2. Translation from (Rykwert et al. 1988, pp. 62–63). |

| 56 | From Oplontis, Atrium 5. Naples, Museo Archeologico Inv. 155730 (Brangantini and Sampaolo 2009, p. 106 No. 5). Clarke (2013) rightly notes that it is not a sinopia, but a sketch for the wall design of another room, Triclinium 14. |

| 57 | Clarke (2009) discusses the issue with regard to the central panels with figural scenes. He notes (p. 135) an example where a mosaicist used the exact same pattern on a 1:1 scale in two different houses. The four paintings he discusses here, however, vary in size, and Clarke suggests (p. 145) that scaling was done via grids. |

| 58 | “Just as the figure of a circle can be traced out on the human body, so too the figure of a square can be elicited from it.” “non minus quemadmodum schema rotundationis incorpore efficitur, item quadrata designatio in eo invenietur.” Vitruvius 3.1.3. Translation from (Schofield 2009, p. 67). It is unclear from the Latin whether Vitruvius meant that “man” should be drawn in both a circle and a square as Leonardo did or separately in each. See (Gros 1990, p. 60). |

| 59 | |

| 60 | The single example that Panofsky (pl. 1 on p. 157) cites for a vanishing vertical axis is not from Boscoreale, but is one small section from a wall in the House of Meleager at Pompeii (VI 9, 2.13, tablinum [8], north wall). Naples, Museo Archeologico inv. 9596 (Brangantini and Sampaolo 2009, pp. 282–87 No. 121 and dated to 62–79 CE). |

| 61 | See (Raynaud 2016, pp. 161–76 [main discussion]). |

| 62 | Compare especially (Elkins 1991), from the title of which I have taken the term “surface geometry”. Yeomans (2011, p. 23) calls this kind of interpretation “epiphenomenal” and says (p. 44) “it is easy to be mesmerized by the number of relationships that can be found, and one can be seduced into an orgy of drawing and the building’s supposed magic.” |

| 63 | E.g., Plato famously complained in the Sophist (235–36) about the distortions sculptors made in pedimental sculpture so that it would look “right” to viewers from below. He does not use skenographia or skiagraphia but symmetria. |

| 64 | See (Small 2012) on how vase shape affects the portrayal of figures. |

| 65 | See (Small 1999, pp. 564–66) on Circe and Odysseus’ men on an Attic black-figure cup in Boston (MFA 99.518) and on the Great Trajanic frieze. |

| 66 | |

| 67 | For an example of the importance of understanding proportion and its effect on how figures look, see (Small 2012). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Small, J.P. Circling Round Vitruvius, Linear Perspective, and the Design of Roman Wall Painting. Arts 2019, 8, 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030118

Small JP. Circling Round Vitruvius, Linear Perspective, and the Design of Roman Wall Painting. Arts. 2019; 8(3):118. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030118

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmall, Jocelyn Penny. 2019. "Circling Round Vitruvius, Linear Perspective, and the Design of Roman Wall Painting" Arts 8, no. 3: 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030118

APA StyleSmall, J. P. (2019). Circling Round Vitruvius, Linear Perspective, and the Design of Roman Wall Painting. Arts, 8(3), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030118