Innovative Exuberance: Fluctuations in the Painting Production in the 17th-Century Netherlands

Abstract

1. Introduction

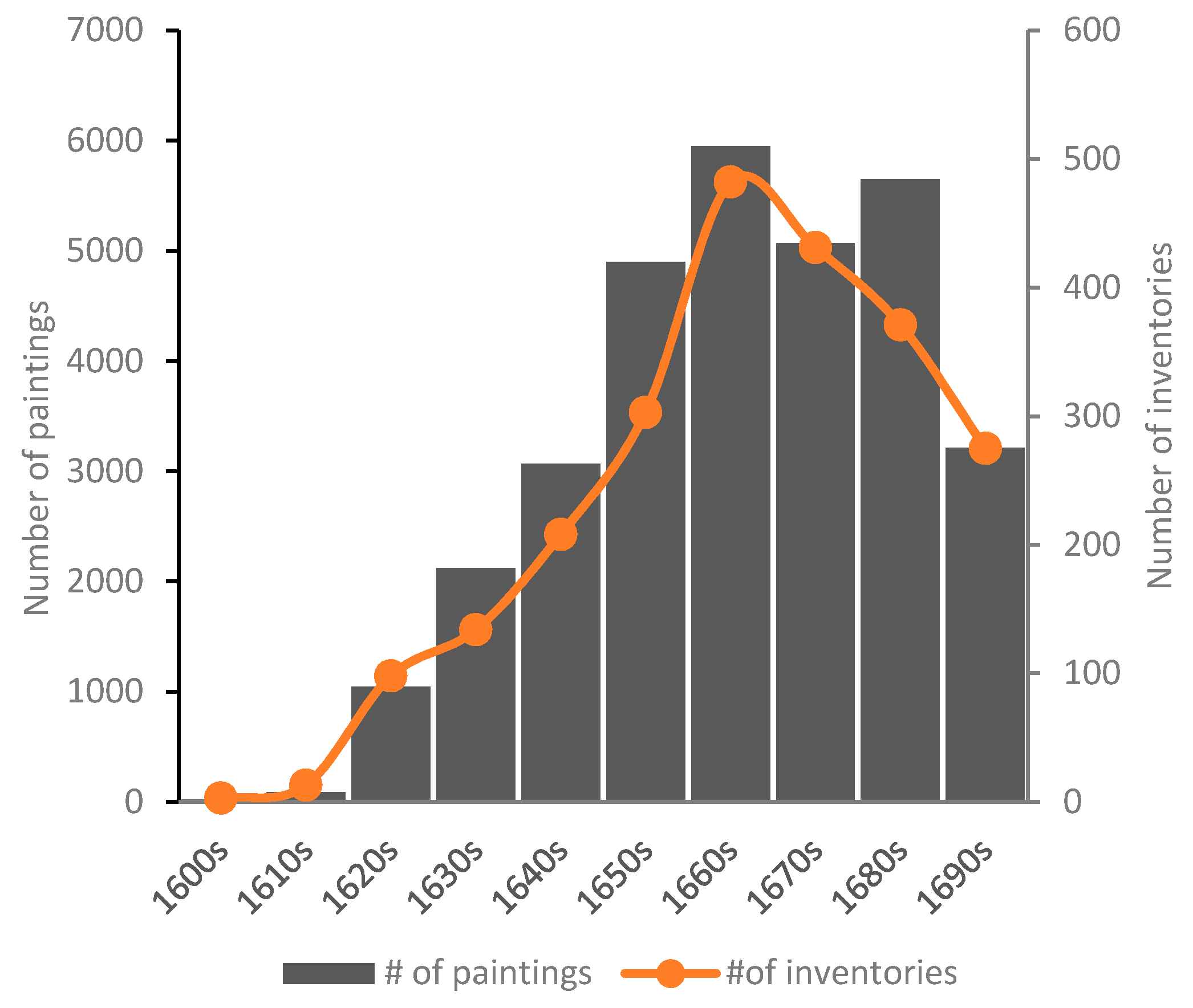

2. Data on Painting Production

3. A Probability Approach to Account for Uncertainties

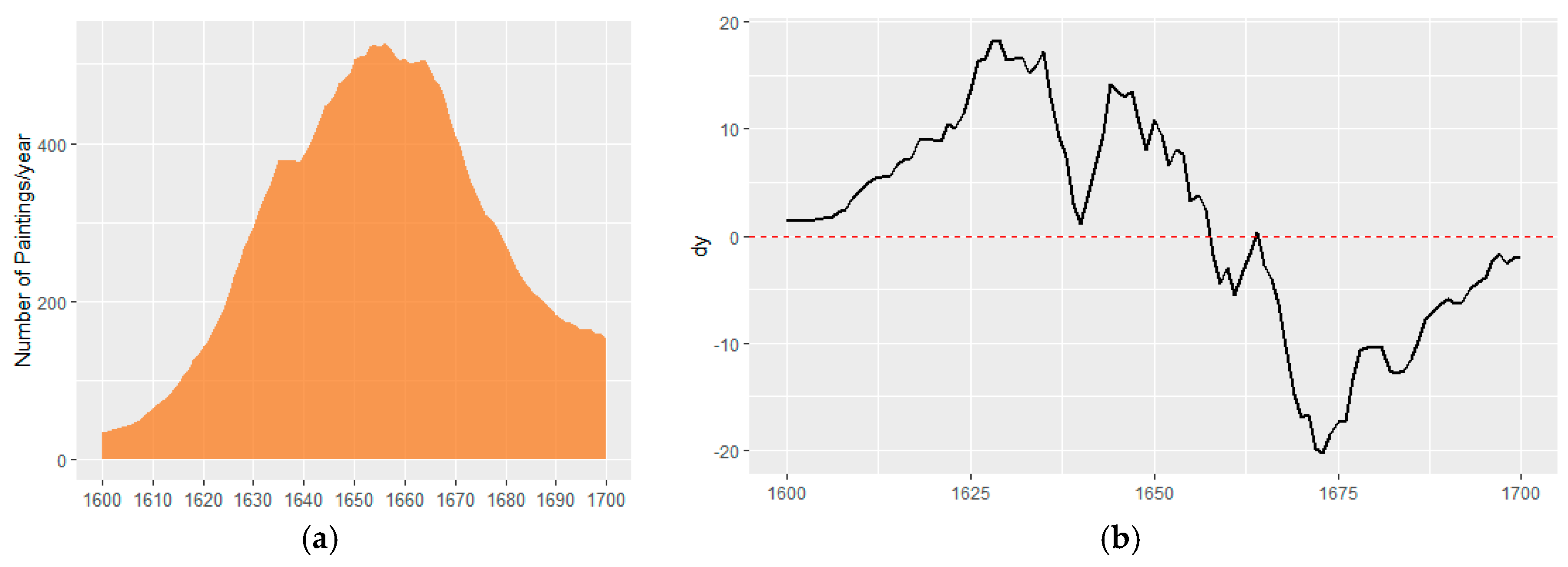

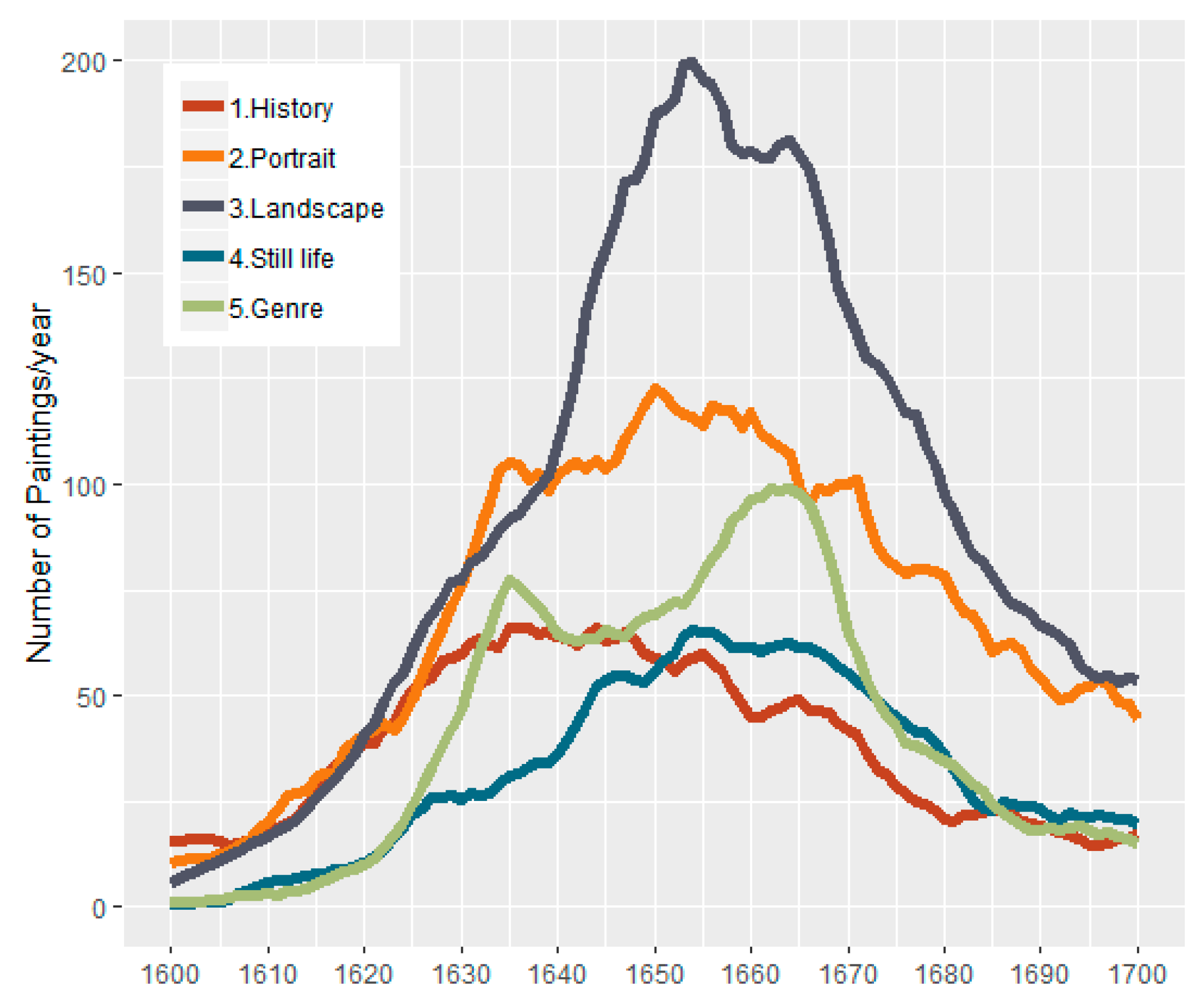

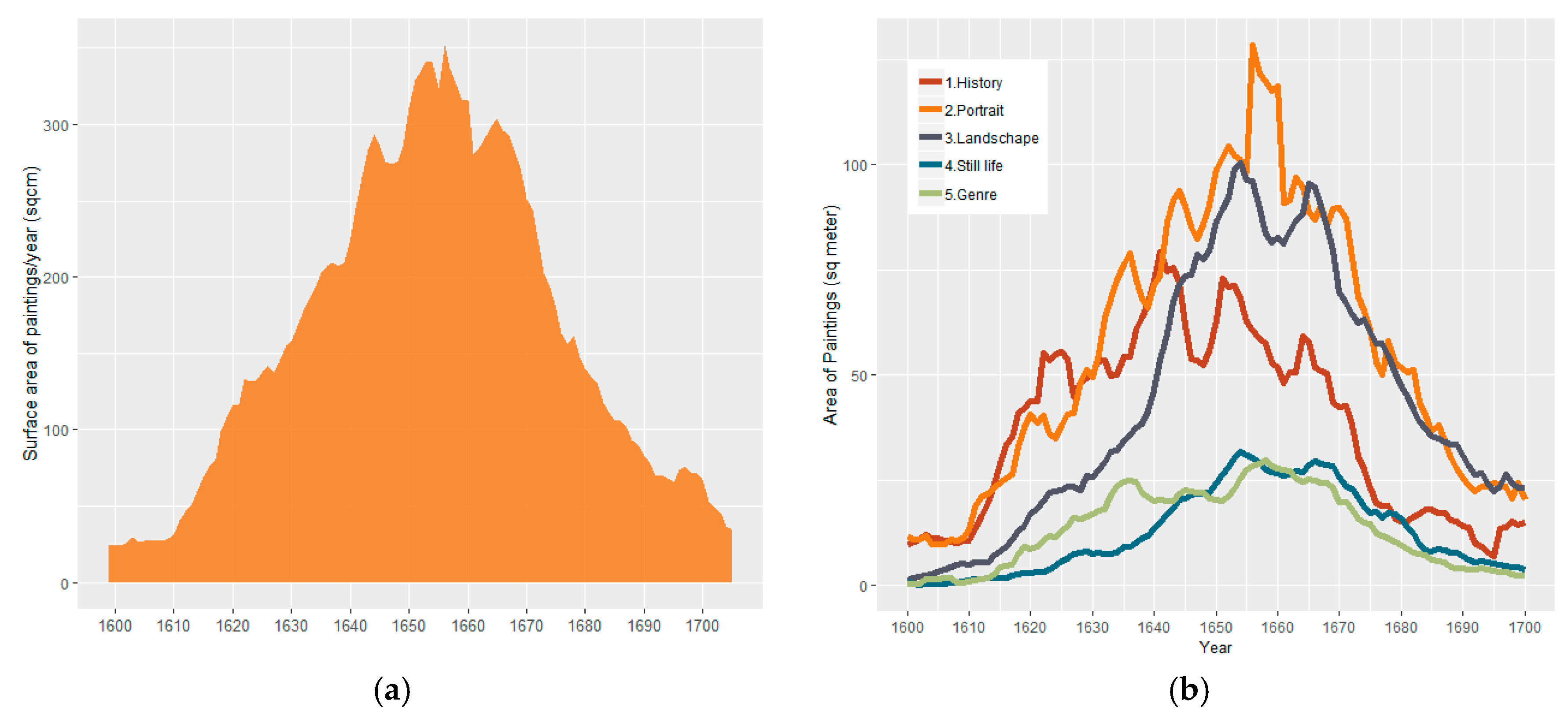

4. Production Trend Visualized

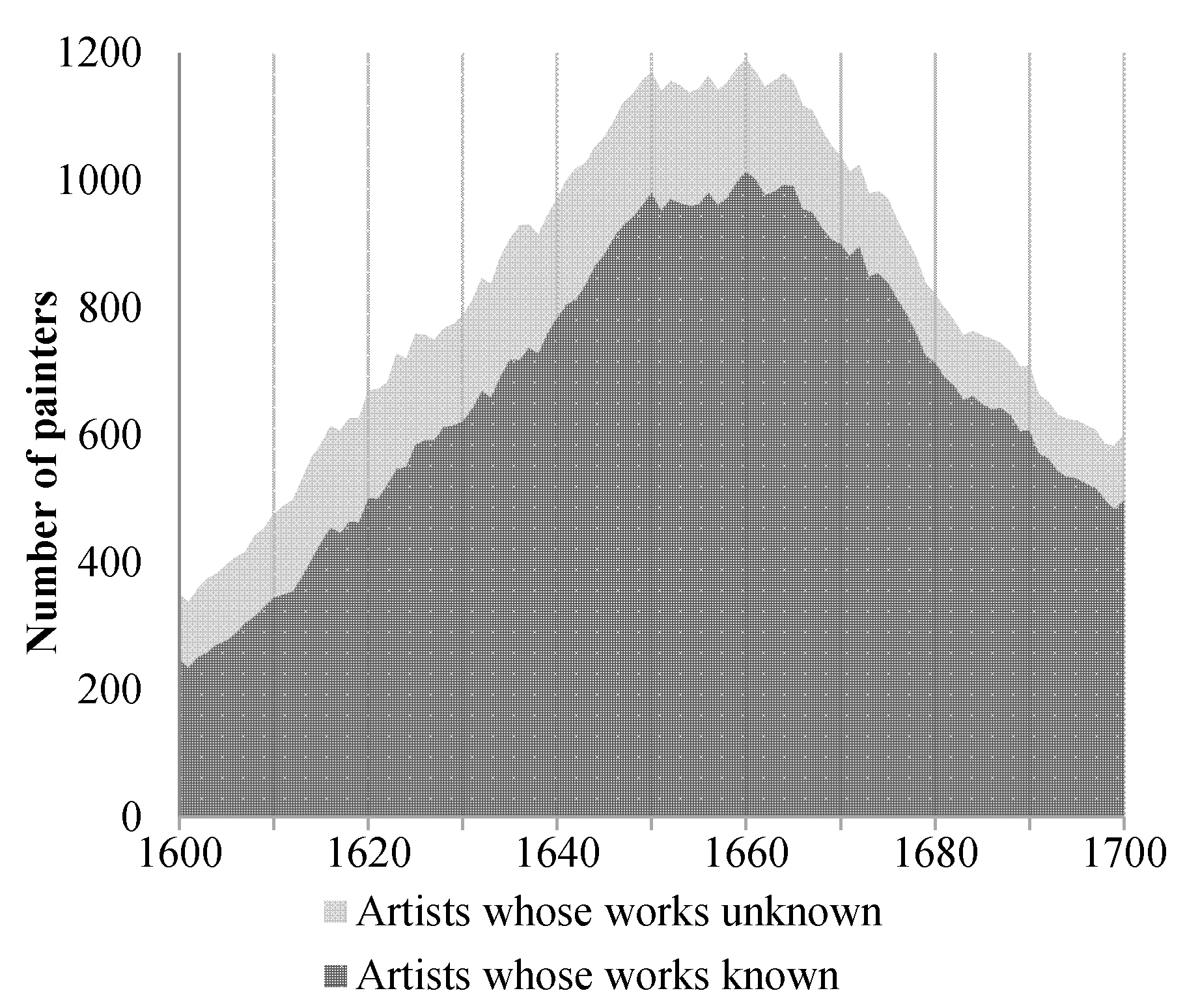

5. Becoming a Painter: Expectation and Risk

5.1. Painting as a Promising Profession

5.2. Painting as a Risky Business

5.3. Decisions under Risk and Uncertainty

6. Collective Enthusiasm and Wide-Spread Endorsement

7. Art Market as a “Social Bubble”

8. Exuberant Innovation

9. Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alpers, Svetlana. 1983. The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Angel, Philips. 1642. De Lof der Schilderkunst. Leiden. [Google Scholar]

- Haverkamp-Begemann, Egbert. 1968. Hercules Seghers. Art and Architecture in the Netherlands. Amsterdam: J. M. Meulenhof. [Google Scholar]

- Bernoulli, Daniel. 1954. Exposition of a New Theory on the Measurement of Risk. Econometrica 22: 23–36. First published 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boers-Goosens, Marion. 2001. Schilders en de markt, Haarlem 1600–1635. Ph.D. Dissertation, Universiteit Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Boers-Goosens, Marion. 2006. Prices of Northern Netherlandish Paintings in the Seventeenth Century. In His Milieu: Essays on Netherlandish Art in Memory of John Michael Montias. Edited by Amy Golany. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Bok, Marten Jan. 1994. Vraag en aanbod op de Nederlandse kunstmarkt, 1580–1700. Ph.D. Dissertation, Utrecht Universiteit, Utrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Bok, Marten Jan. 1998. Pricing the Unpriced. How Dutch 17th-Century Painters determined the Selling Price of their Work. In Art Markets in Europe, 1400–1800. Edited by Michael North and David Ormrod. Aldershot: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bok, Marten Jan. 2001. The Rise of Amsterdam as a cultural center: the market for paintings, 1580–1680. In Urban Achievement in Early Modern Europe: Golden Ages in Antwerp, Amsterdam and London. Edited by Patrick O’Brien. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 186–209. [Google Scholar]

- Bok, Marten Jan. 2002. Fluctuations in the Production of Portraits made by Painters in the Northern Netherlands, 1550–1800. In Economia e Arte, Secc. XIII-XVIII. Edited by Simonetta Cavaciocchi. Atti delle Settimane di Studi e altri Convegni. Prato: Istituto Internazionale di Storia Economica F. Datini, pp. 649–62, Data see Appendix I, pp. 654–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bok, Marten Jan. 2008. ‘Paintings for Sale’: New Marketing Techniques in the Dutch Art Market of the Golden Age. In At Home in the Golden Age. Edited by Jannet de Goede and Martine Gosselink. Rotterdam: Kunsthal, Zwolle: Waanders, pp. 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bredius, Abraham. 1891. De kunsthandel te Amsterdam in de 17e eeuw. Amsterdamsch Jaarboekje, 54–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bredius, Abraham. 1915–1922. Künstler-Inventare, Urkunden zur Geschichte der holländische Kunst des XVIten, XVIIten und XVIIIten Jahrhunderts. 7 vols, The Hague: Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Brosens, Koenraad, and Katlijne Van der Stighelen. 2002. Paintings, prices and productivity: lessons learned from Maximiliaan de Hase’s Memorie boeck (1744–80). Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 36: 173–83. [Google Scholar]

- Caves, Richard Earl. 2000. Creative Industries: Contracts between Art and Commerce. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Paul. 2006. Rembrandt’s Bankruptcy: The Artist, His Patrons, and the Art Market in Seventeenth-Century Netherlands. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Jager, Ronald. 1990. Meester, leerjongen, leertijd: Een analyse van zeventiende-eeuwse Noord-Nederlandse leerlingcontracten van kunstschilders, goud- en zilversmeden. Oud Holland 104: 69–111. [Google Scholar]

- De Marchi, Neil. 1995. The role of Dutch auctions and lotteries in shaping the art market (s) of 17th century Holland. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 28: 203–21. [Google Scholar]

- De Marchi, Neil, and Hans Van Miegroet. 1994. Art, Value, and Market Practices in the Netherlands in the Seventeenth Century. The Art Bulletin 76: 451–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, Neil, and Hans Van Miegroet. 2006. The History of Art Markets. In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture 1. Edited by Victor A. Ginsburg and David Throsby. Amsterdam: North Holland, pp. 69–122. [Google Scholar]

- De Marchi, Neil, and Hans J. Van Miegroet. 2014. Supply-demand imbalance in the seventeenth-century Antwerp-Mechelen paintings market. In Moving pictures: intra-European trade in images, 16th-18th centuries. Edited by Sophie Raux, Neil De Marchi and Hans. J. Van Miegroet. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, pp. 37–76. [Google Scholar]

- De Moor, Tine, and Jaco Zuijderduijn. 2013. The Art of Counting: Reconstructing Numeracy of the Middle and Upper Classes on the Basis of Portraits in the Early Modern Low Countries. Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 46: 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, Jan. 1978. Barges and Capitalism: Passenger Transportation in the Dutch Economy, 1632–1839. Wageningen: A.A.G. Bijdragen. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, Jan. 1991. Art history. In Art in History/History in Art: Studies in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Culture. Edited by David Freedberg and Jan de Vries. Santa Monica: Getty Center for Art History and the Humanities, pp. 331–72. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, Jan, and Ad Van der Woude. 1997. The First Modern Economy: Success, Failure, and Perseverance of the Dutch Economy, 1500–1815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dempster, Anna M., ed. 2014. Risk and Uncertainty in the Art World. London, New Dehli, New York and Sydney: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Engelberts Gerrits, Gerrit. 1844. Schoonheden uit de Nederlandsche Dichters. Amsterdam: Ten Brink & De Vries, vol. I. [Google Scholar]

- Evelyn, John. 2005. The Diary of John Evelyn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 3. First published 1641. [Google Scholar]

- Falkenburg, Reindert L. 1997. Onweer bij Jan van Goyen. Artistieke wedijver en de markt voor het Hollandse landschap in de 17de eeuw. Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 48: 117–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fock, C. W. 2007. Het interieur in de Republiek 1670–1750: een plaats voor schilderkunst? In De Kroon op het Werk: Hollandse Schilderkunst 1670–1750. Edited by Ekkehard Mai, Sander Paarlberg and Gregor J. Marlies Weber. Keulen, Dordrecht and Kassel: Keulen Verlag Locher, pp. 63–84. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, Bruno S., and Reiner Eichenberger. 1995. On the Rate of Return in the Art Market: Survey and Evaluation. European Economic Review 39: 528–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, E. Melanie, and Lisha Deming Glinsman. 2017. Collective Style and Personal Manner: Materials and Techniques of High-Life Genre Painting. In Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry. Edited by Adriaan E. Waiboer, Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. and Blaise Ducos. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gisler, Monika, and Didier Sornette. 2008. ’Bubbles in Society’—The Example of the United States Apollo Program. May 30. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1139807 (accessed on 24 April 2018).

- Gisler, Monika, and Didier Sornette. 2009. Exuberant innovations: The Apollo program. Society 46: 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldgar, Anne. 2007. Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Linda, Greg Brandeau, Emily Truelove, and Kent Lineback. 2014. Collective Genius: The Art and Practice of Leading Innovation. Cambridge: Harvard Business Review Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Angela. 2017. Creating Distinctions in Dutch Genre Painting: Repetition and Invention. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoogstraten, Samuel. 1678. Inleyding tot de Hooge Schoole der Schilderkonst, Rotterdam. Rotterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Houbraken, Arnold. 1718–1721. De groote schouburgh der Nederlantsche konstschilders en schilderessen. 3 vols, Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Huygens, Constantijn. 1987. Mijn jeugd. Edited by Christiaan Lambert Heesakkers. Amsterdam: Querido. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, Jonathan. 1997. Adjusting to Hard Times: Dutch art during its period of crisis and restructuring (c. 1621–c. 1645). Art History 20: 449–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, Angela. 2016. ‘Galey-schilders’ en’dosijnwerck’: De productie, distributie en consumptie van goedkope historiestukken in zeventiende-eeuws Amsterdam. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1979. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 47: 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1984. Choices, Values and Frames. American Pyschologist 39: 341–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1992. Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 5: 297–323. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 2013. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In Handbook of the Fundamentals of Financial Decision Making: Part I. Hackensack: World Scientific Pub Co Inc., pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- Klinke, Harald, Liska Surkemper, and Justin Underhill. 2018. Creating New Spaces in Art History. International Journal for Digital Art History: Digital Space and Architecture 3: 9. [Google Scholar]

- Kolfin, Elmer. 2006. The Young Gentry at Play: Northern Netherlandish Scenes of Merry Companies 1610–1645. Leiden: Primavera Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kräussl, Roman, Thorsten Lehnert, and Nicolas Martelin. 2016. Is There a Bubble in the Art Market? Journal of Empirical Finance 35: 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Weixuan. 2018. Deciphering the Art and Market in the Dutch Golden Age: Insights from Digital Methodologies. Master’s thesis, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Matthew D. 2016. Social Network Centralization Dynamics in Print Production in the Low Countries, 1550–1750. International Journal for Digital Art History. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Wilhelm. 1901. Het leven en de werken van Gerrit Dou beschouwd met het schildersleven van zijn tijd. Ph.D. Dissertation, Leiden Universiteit, Leiden, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Montias, John Michael. 1982. Artists and Artisans in Delft: A Socio-Economic Study of the Seventeenth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montias, John Michael. 1987. Cost and Value in Seventeenth-Century Art. Art History 10: 455–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montias, John Michael. 1988. Art dealers in the seventeenth-century Netherlands. Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 18: 244–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montias, John Michael. 1990. Estimates of the Number of Master-painters, Their Earning and Their Output in 1650. Leidschrift 6: 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Montias, John Michael. 1996. Works of Art in a Random Sample of Amsterdam Inventories. In Economic History and the Arts. Edited by Michael North. Cologne: Böhlau, pp. 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Montias, John Michael. 2002. Art at Auction in Seventeenth-Century Amsterdam. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mundy, Peter. 1925. The Travels of Peter Mundy in Europe and Asia, 1608–1667, vol. 4, Travels in Europe, 1639–47. Edited by R. Carnac Temple. London: Hakluyt Society. [Google Scholar]

- Nijboer, Harm. 2010. Een bloeitijd als crisis: Over de Hollandse schilderkunst in de 17de eeuw. Holland 42: 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Pesando, James E. 1993. Art as an Investment: The Market for Modern Prints. The American Economic Review 83: 1075–89. [Google Scholar]

- Petram, Lodewijk. 2014. The World’s First Stock Exchange. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Prak, Maarten. 2008. Painters, Guilds, and the Art Market During the Dutch Golden Age. In Guilds, Innovation, and the European Economy, 1400–1800. Edited by S. R. Epstein and Maarten Prak. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 143–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rasterhoff, Claartje. 2017. Painting and Publishing as Cultural Industries: The Fabric of Creativity in the Dutch Republic, 1580–1800. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roodenburg, Herman. 2006. Visiting Vermeer: Performing Civility. In In His Milieu: Essays on Netherlandish Art in Memory of John Michael Montias. Edited by Amy Golahny, Mia M. Mochizuki and Lisa Vergara. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 385–94. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, Sherwin. 1981. The Economics of Superstars. The American Economic Review 71: 845–58. [Google Scholar]

- Sluijter, Eric Jan. 1991. Didactic and Disguised Meanings? Several Seventeenth-Century Texts on Painting and the conological Approach to Dutch Paintings of this Period. In Art in History. History in Art. Studies in Seventeenth Century Dutch Culture. Edited by David Freedberg and Jan de Vries. Santa Monica: Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, pp. 175–207. [Google Scholar]

- Sluijter, Eric Jan. 1999. Over Brabantse vodden, economische concurrentie, artistieke wedijver en de groei van de markt voor schilderijen in de eerste decennia van de zeventiende eeuw. Nederlands Kunsthistorische Jaarboek 50: 113–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluijter, Eric Jan. 2015. Rembrandt’s Rivals: History Painting in Amsterdam 1630–1650. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sornette, Didier. 2008. Nurturing breakthroughs: lessons from complexity theory. Journal of Economic Interaction and Coordination 3: 165–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sornette, Didier. 2017. Why Stock Markets Crash: Critical Events in Complex Financial Systems. New Haven: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, Richard H. 1993. Advances in Behavioural Finance. New York: Russel Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, Richard H., and Cass R. Sunstein. 2008. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Woude, Ad. 1991. The volume and value of paintings in Holland at the time of the Dutch Republic. In Art in History, History in Art: Studies in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Culture. Edited by David Freedberg and Jan de Vries. Santa Monica: Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, pp. 284–329. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gool, Jan. 1750–1751. De nieuwe schouburg der Nederlantsche kunstschilders en schilderessen. 2 vols, The Hague. [Google Scholar]

- Van Miegroet, Hans, and Neil De Marchi. 2012. Uncertainty, Family Ties and Derivative Painting in Seventeenth-Century Antwerp. In Family Ties. On Art Production, Kinship Patterns and Connections 1600–1800. Edited by Koenraad Brosens, Katlijne Vam Der Stighelen and Leen Kelchtermans. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Veblen, Thorstein. 1934. The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions. New York: The Modern Library. First published 1899. [Google Scholar]

- Westermann, Mariet. 2005. A worldly art: The Dutch Republic, 1585–1718. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weyerman, Jacob C. 1729–1769. De levens-beschryvingen der Nederlandsche konst-schilders en konst-schilderessen. 4 vols, The Hague. [Google Scholar]

- Zorich, Diane. 2013. Digital Art History: A Community Assessment. Visual Sources: Digital Art History 29: 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | RKDimages, contained 55,718 unique paintings in the dataset acquired via the RKD public API, accessed February 2018. |

| 2 | The low-quality paintings, such as “works-by-the-dozen” (dosijnwerck) had a much lower survival rate than those of Rembrandt or Vermeer and are thus under-represented in the modern database. Jager (2016) lifts the curtain to the lower segment of the art market for which the “works-by-the-dozen” were produced. Yet, the inventories of few art dealers can hardly be a representative sample to quantify the degree of distortion in the RKD database. |

| 3 | Cf. (Van der Woude 1991; Montias 1990; De Marchi and Van Miegroet 2006, 2014; Rasterhoff 2017, etc.) |

| 4 | However, there is no thorough survey of all archival inventories, and the majority of known inventories were collected to suit art historical interests and are biased towards the collections of the wealthy with more works of art in the few large cities. The inventories in the Getty Provenance Index only has inventories from Amsterdam, Haarlem, Utrecht, Leiden, and Delft with a focus on the inventories in Amsterdam. As a result, they cannot truly reflect the collecting pattern of the whole society and are therefore also a biased sample (Montias 1996). |

| 5 | The categorization of genres in this study follows the main genre described in the RKD database. For example, a landscape with the staffage figures embodying a religious lesson is still regarded as landscape instead of history painting. |

| 6 | 96.6% of paintings in the RKDimages have size recorded in the dataset. The loss of data due to the change of measurements is thus negligible. |

| 7 | Cf. Hadrianus Junius, Batavia, Leiden, 1589 (the first city description in which painters were included as “famous sons” of the city); J.I. Pontanus, Historische beschrijvinghe der seer wijt beroemde coop-stad Amsterdam, Amsterdam 1614; Jan Orlers, Beschrijvinge der stad Leyden, Leiden 1641. Preacher Samuel Ampzing and theologian Schrevelius wrote in 1628 and 1648 respectively the praise for the city of Haarlem with several laudatory poems dedicated to painters. |

| 8 | Angel went as far as saying: “I win a lot of money, [as] I make large paintings.” (Ick winne machtich gelt, ick maecke groote stucken). See (Angel 1642, pp. 28–29). Mentioned in (De Marchi and Van Miegroet 1994). |

| 9 | More prominent painters (A++, A+ samples according to Rasterhoff’s categorization) were born around 1590–1630, entering the market around the first decades of the 17th century (Rasterhoff 2017, p. 206, Figure 7.4). |

| 10 | An artist-painter (kunstschilder) was often literate and had attended school full-time for three years. After this initial investment in basic education, for which Montias has estimated an accumulated expense of fl. 150 to fl. 200, aspiring artists had to invest in an apprenticeship period. Some pupils finished their training with a trip to Italy at a considerable cost, which was often a privilege of the pupils from affluent families. For basic education see (De Jager 1990; Boers-Goosens 2001, p. 87). And for painting apprenticeships, see (Montias 1982, p. 169). For the entry barriers for artist, see (Rasterhoff 2017, p. 232). See also (Bok 1994, pp. 53–97). |

| 11 | See ECARTICO for numerous cases for pupils of masters of whom we do not know their works. |

| 12 | Jan Porcellis, Jan van Goyen, Frans Hals, Jan Steen, Hercules Seghers, Pieter de Hooch, Vermeer and Rembrandt have been found taking debts. See (Rasterhoff 2017, p. 237). |

| 13 | There are a handful of examples of such contracts. Just to name a few: In 1625, for instance, painter Jacques de Ville decided upon delivering fl. 2400 worth of paintings over the course of a year and a half to skipper Hans Melchiorsz; in 1641, art dealer Leendert Volmarijn is known to have ordered thirteen pictures from Isaac van Ostade; art dealer Joris de Wijs contracted with Emanuel de Witte to paint for fl. 800 a year plus room and board (Montias 1988, pp. 65–66; Montias 1987, p. 99; Bredius 1891, pp. 56–57). |

| 14 | Samuel van Hoogstraten told the tale of Hercules Pietersz Seghers that Seghers sold a copperplate to an art dealer for very little money. The dealer, “after having printed a few copies from his plate he cut it into pieces, saying that the time would come that collectors would pay for one copy four times as much he had asked for the whole plate, which actually did happen because each print later bourught sxteen ducat, […] but poor Hercules did not get any of this” (Hoogstraten 1678, p. 312). Translation is taken from (Haverkamp-Begemann 1968, p. 8). |

| 15 | Existing studies use extensive data on the price of painting in auctions and sales across time to develop a price index to identify abnormal bumps in the price index. However, collecting large and representative 17th century price data of Dutch paintings is almost impossible as most sales of paintings do not have records. Most of the price information of paintings are from probate inventories and contracts: the former can hardly represent the sale price and the latter is too small to be representative. For these reasons, this research will limit its scope to the social bubble without claiming a speculative bubble in the 17th-century Dutch art market. |

| 16 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, W. Innovative Exuberance: Fluctuations in the Painting Production in the 17th-Century Netherlands. Arts 2019, 8, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020072

Li W. Innovative Exuberance: Fluctuations in the Painting Production in the 17th-Century Netherlands. Arts. 2019; 8(2):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020072

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Weixuan. 2019. "Innovative Exuberance: Fluctuations in the Painting Production in the 17th-Century Netherlands" Arts 8, no. 2: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020072

APA StyleLi, W. (2019). Innovative Exuberance: Fluctuations in the Painting Production in the 17th-Century Netherlands. Arts, 8(2), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020072