Abstract

In Willem van Haecht’s Gallery of Cornelis van der Geest, The Last Judgment by the German artist Hans Rottenhammer stands prominently in the foreground. Signed and dated 1598, it is one of many copper panel paintings Rottenhammer produced and sent north of the Alps during his decade-long sojourn in Venice. That the work was valued alongside those of Renaissance masters raises questions about Rottenhammer’s artistic status and how the painting reached Antwerp. This essay examines Rottenhammer’s international market as a function of his relationships with artist-friends and agents, especially those in Venice’s German merchant community. By employing digital visualization tools alongside the study of archival documents, the essay attends to the intermediary connections within a social network, and their effects on the art market. It argues for Rottenhammer’s use of—and negotiation with—intermediaries to establish an international career. Through digital platforms, such as ArcGIS and Palladio, the artist’s patronage group is shown to have shifted geographically, from multiple countries around 1600 to Germany and Antwerp after 1606, when he relocated to Augsburg. Yet, the same trusted friends and associates he had established in Italy continued to participate in Rottenhammer’s business of art.

1. Introduction

As artist and critic Carel van Mander indicated in 1604, to succeed as an artist, one must study the works of ancients and acquire the skills and techniques of Italian masters. A period of education in Italy was essential, for, as Van Mander suggested pointedly, “In Rome one learns to draw, in Venice, to paint” (van Mander 1969, p. 75). Hans Rottenhammer (ca. 1564–1625) was one of the many Northern European artists who crossed the Alps after his apprenticeship in order to gain further education. Best known for his paintings of mythological and religious themes on copper panels, the Munich-born Rottenhammer not only acquired the styles and motifs of Italian masters but also developed a savvy mercantile education in marketing and networking as he constructed an international career from Venice through the use of his networks of artist-friends and the German merchant community. Unlike many of his contemporaries who stayed for one to two years before returning home, Rottenhammer remained in Italy for about seventeen years, from 1589 to 1606. During this period, he opened a successful workshop in Venice, gained a reputation for small-format cabinet paintings on copper panels, and married a Venetian woman named Elisabetha d’ Fabris (also called Isabetta di Fabri), with whom he had five children. He would return to Germany, settling in Augsburg, but maintained the same trusted friends and associates in the network he helped to develop in Italy.

Rottenhammer’s production of copper paintings occurred primarily in Rome and Venice. Yet, much of Rottenhammer’s production was acquired by northern patrons and collectors. The taste for copper painting probably depended on the preciousness of the result: Because the pigments were not absorbed into the smooth, hard metal, they remained on the surface and retained their richness, luminosity, and texture. Van Mander noted the artist’s international patronage, as he described the artist’s “multitude of handsome pieces on copper—some large, some small, which are distributed through many countries and can be seen with art lovers” (van Mander and Miedema 1994–1999). In other words, Rottenhammer achieved international success as a foreign artist working in one of the most competitive cultural centers in Europe during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

Scholars have long positioned Rottenhammer’s paintings on copper as objects of cultural transmission, in which the Venetian style was transposed to precious cabinet paintings for collections in Germany and Northern Europe (Peltzer 1916; Schlichtenmaier 1988; Borggrefe et al. 2007; Borggrefe et al. 2008). His Diana and Actaeon (Figure 1), for example, combines the figural motifs of female nudes seen in paintings by Italian masters Leonardo, Raphael, Titian, and Tintoretto with the luscious flesh tones and color harmonies of Titian and Veronese. Yet, the subject of the artist as a businessman has received little attention. While Heiner Borggrefe has discussed Rottenhammer as an agent for the Rudolfine imperial court (Borggrefe 2007), the broader scope of Rottenhammer’s entry into the circles of leading patrons and business strategies for collectors and the general market has not yet been examined to any great degree. That Rottenhammer not only acquired an education in artistic styles and practices in Italy but also developed a savvy mercantile education in marketing and networking as he constructed an international career from Venice remains significant and warrants a closer look.

Figure 1.

Hans Rottenhammer, Diana and Actaeon, 1602. Oil on copper. Munich, Alte Pinakothek, Inv. 1588. © Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen. CC BY-SA 4.0. https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/bookmark/artwork/o5xr7XML7X.

Art historians interested in the relation of art to economic life tend to fall back on one of two models: that of the direct relation between the artist and an individual patron, or that of the “market”, understood as an open field in which objects circulate freely according to the laws of supply and demand, following the foundational studies of Francis Haskell and J. M. Montias, respectively (Haskell 1980; Montias 1982). Neither of these models is adequate to deal with the real complexity of the situation, and the example of Rottenhammer shows why: His success depended on the network of associations he developed and assiduously maintained, in some cases employing agents, as merchants commonly did and as modern artists commonly do.

Operating in the interstices between court artist and an artist for a general market, Rottenhammer represents an alternative model for understanding how an artist garnered success during the late sixteenth century. By working through multiple networks, and employing them strategically, Rottenhammer participated in what I call an artist–agent model. By this term, I mean an artist who negotiated with various groups, including artist-friends, merchants, and agents, and would become an art agent himself. My work provides an alternative model for how early modern artists built a career, contributing to the discussions of the inextricable relationship between art and commerce (McCabe 2019).

2. Methodology

In studying Rottenhammer’s use of networks, my project brings social network analysis and intermediation perspectives together with the themes of Northern European artists working in Italy and early modern markets, the literature of which remains vast (Panofsky [1943] 2005; Dacos 1964; Jaffé 1977; Aikema and Brown 2000; Goldthwaite 1993; Fantoni et al. 2003; De Marchi and Van Miegroet 2006; Spear and Sohm 2010). Rottenhammer’s education in Italy helped him to develop an Italianate style meeting the taste of leading European patrons, what I refer to as a stylistic integration of the works of Italian, Flemish, and German masters or an international style (McCabe 2019). Northern European artists relied on the support of established foreign communities in Italy, especially welcome during their initial years. I suggest Rottenhammer’s associations with the German merchant community in Venice and the community of Northern European artists in Rome enabled him to establish an international career from Venice. Rottenhammer’s copper panel The Last Judgment (Figure 2), painted in the lagoon city in 1598, for example, entered the collection of Antwerp spice merchant and art lover Cornelis van der Geest, as seen in the right foreground of Willem van Haecht’s 1628 painting (Figure 3) (Held et al. 1982). That the work was valued alongside those of Renaissance masters raises questions about Rottenhammer’s artistic status and how the painting reached Antwerp.

Figure 2.

Hans Rottenhammer, Last Judgment, 1598. Munich, Alte Pinakothek, Inv. 45. © Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen. CC BY-SA 4.0. https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/en/bookmark/artwork/5347YR5L9e.

Figure 3.

Willem van Haecht, Gallery of Cornelis van der Geest, 1628. Antwerp, Rubenshuis, Inv. RH.S.171. Public domain. Rottenhammer’s Last Judgment at bottom right.

Rottenhammer’s patronage network included princely rulers, cardinals, and merchants. To better understand how Rottenhammer established relationships with leading patrons, I turn to the artist’s network structure to discern his key intermediaries. I reconstructed Rottenhammer’s network with primary data of correspondences, contracts, testimonials, marriage records, and inventories gathered from published sources and located in archival collections in Wolfenbüttel, Bückeburg, Munich, Augsburg, Milan, and Venice, as well as inventory databases, such as the Getty Provenance Index® Databases. My dataset also includes Rottenhammer’s paintings, drawings, and prints maintained in museums, public institutions, and private collections. I used the appendices of Harry Schlichtenmaier’s 1988 dissertation as references for the works of art, supplemented with the entries of the 2008 Rottenhammer exhibition catalogue and the Brueghel Family Database, which lists collaborative paintings between Rottenhammer and Jan Brueghel the Elder and encompasses Klaus Ertz’s 2008–2010 catalogue raisonné of Brueghel paintings.

To reconstruct Rottenhammer’s painting market in addition to his social network and associated networks, three tables are necessary: (1) paintings; (2) the individuals associated with Rottenhammer; and (3) Rottenhammer’s connections with the individuals. The first table is the dataset of paintings identifying known works according to their painting support (copper, canvas, wooden panel, fresco) and function (altarpiece, ceiling decoration), as tied to production city, patron, patron city, and collaborator, if a collaboration. This table is used to map geospatially Rottenhammer’s painting market. The second table is a dataset of the individuals in Rottenhammer’s network, organized by their attributes, such as role (intermediary, agent, patron), capacity (artist, prince, merchant, cardinal), and religion (Catholic, Protestant, Converso). I selected these categories for analysis because I wish to understand the network’s composition in terms of the ratio of patrons to intermediaries and agents, and how Rottenhammer’s commercial success possibly depended upon the node’s position or religion. The third and final table is a relational matrix connecting the individuals discovered in the archival documents, as well as known paintings and engravings. The table of individuals (called “nodes” in social network analysis terms) and the relational matrix (“edges”) are used together in order to produce a visualization of the network structure.

The first challenge is to identify the type of relationship each node maintains with another, and to recognize that multiple types of edges potentially exist between two nodes. The second challenge is to categorize the edge, managing the expanding number of types of relationships so that the visualization remains legible. To make sense of the dense thicket of Rottenhammer’s network, it is necessary to zoom in for a microlevel view of the network structure. Here, one sees how Rottenhammer likely gained access to patrons, such as Cardinal Federico Borromeo, through his collaborators Paul Bril or Jan Brueghel the Elder.

Social network theories examining network structures and social capital by James Coleman and Ronald Burt help frame my approach. Coleman’s discussion of social capital—not as a single entity, but rather composed of several entities with a social structure that facilitates certain actions of actors within—moves the discussion from effects on a single individual to that of the group, which aligns with the foreign community framework that Rottenhammer negotiated (Coleman 1988). Burt’s theory of structural holes draws from Mark Granovetter’s theory of the strength of weak ties, in which individuals with weak ties form a bridge, and these bridging ties lead to novel information (Granovetter 1973). Burt posits that an individual with a network of discrete groups could potentially be in a bridging position. With the potential to synthesize and broker the information across these gaps, or structural holes, this individual stands to gain more social capital (Burt [2005] 2007). In effect, the theories of Coleman and Burt push and pull at the dynamics of a network, moving what is gained by actions in the structure from group to individual. As will become clear in my discussion, the intermediaries in Rottenhammer’s network located at bridging positions were his artist-friends, especially his collaborators, and German agents.

There are few studies in art history that employ social network analysis (SNA) methods. Koenraad Brosens’s work on the tapestry industry and its networks is one which uses the lens of economic sociology from Mark Granovetter’s work on the embeddedness of economic action in networks of personal relationships to measure the levels of trust between individuals in the tapestry production between 1580 and 1780 (Granovetter 1985; Brosens 2012, p. 45; Brosens et al. 2016). Brosens and his team’s use of SNA demonstrates the importance of women as not only bridging nodes in marriage between interlocking networks of the tapestry industry, but also as working partners (Brosens et al. 2016).

In a similar vein, my use of SNA seeks to understand the determining factors for Rottenhammer’s international success. Through the lens of Coleman and Burt, SNA allows for an overall view of Rottenhammer’s social structure. Since the artist moved from Munich to Venice and the Veneto, to Rome, back to Venice, and then settled in Augsburg, it is important to understand what communities he became a part of and how his involvement in these communities enabled his rise in social and economic capital. Unlike Brosens’s study of familial ties in the tapestry industry, Rottenhammer’s connections to his patrons and the art market were not through family but, rather, social ties. SNA provides a means to discuss Rottenhammer’s economic and social capital as tied to the structure composed of relationships with princes, cardinals, and leading merchants, where many connections between the artist and his patrons were facilitated by his intermediaries of artist-friends and agents.

The significance of intermediaries and agents can be located within recent scholarship concerning secretaries, ambassadors, and others as brokers of information (Cools et al. 2006; Keblusek and Noldus 2011; Martin 1995; Martin 2008; Meadow 2009). Operating between the prince or merchant and the intended artist or art market, these intermediaries and agents helped to obtain desirable objects for their patrons. Artists functioned in this role, too, as shown by Marika Keblusek’s work on cultural and political agents, whereby artists were simultaneously cultural brokers, diplomats, and potential political spies (Keblusek 2011). In such positions, Rottenhammer and his artist-friends could traverse smoothly between various networks and perform multiple roles—artist, intermediary, art agent.

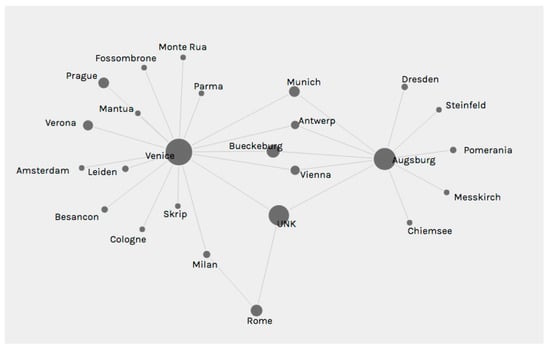

This project benefits from the use of digital tools to analyze Rottenhammer’s painting market and his network. The combination of mapping the artist’s paintings across Europe and visualizing his network of patrons, artist-friends, and agents opens up new ways to understand Rottenhammer’s key markets and key intermediaries. The geographic information system (GIS) platform ArcGIS, developed by Esri, indicates the international extent of Rottenhammer’s patrons and the taste for his international style (Figure 4). As a static illustration, the ArcGIS map yields little information, as the platform is meant to be used interactively. For example, each location, when viewed online, lists the paintings sent to that particular location, along with the name of the patron who commissioned or acquired the work.

Figure 4.

Rottenhammer’s painting market overall, known patrons and anonymous collectors. Created by the author with ArcGIS.

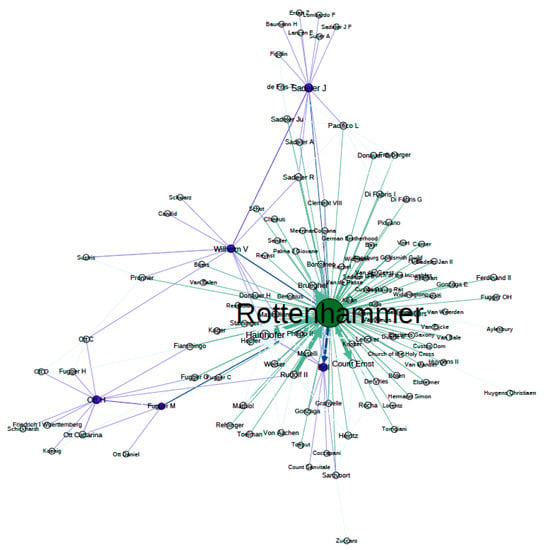

A second digital platform useful for my analysis is Palladio, an open-access, open-source platform maintained by Stanford University. Unlike ArcGIS, Palladio provides information about the relative number of paintings Rottenhammer sent to patrons from the production cities of Venice and Augsburg, the two largest nodes on the graph (Figure 5). At the same time, because Palladio is not dependent on geography, paintings for unknown collectors (“UNK”) are also included in the visualization. With Palladio, a key observation appears immediately: four cities—Munich, Antwerp, Bückeburg, and Vienna—remained constant in Rottenhammer’s career during his Venetian period and later Augsburg years. This finding helped me formulate a hypothesis about Rottenhammer’s use of networks. I suggest the artist engaged key intermediaries from his network of artist-friends that had formed during his Italian period, and these intermediaries, who had settled in places like Antwerp and Munich, facilitated his introductions to patrons, and helped him bring his paintings to market. As an international painter, Rottenhammer already enjoyed patronage support from northern princes, and worked to maintain the relations after his return to Germany.

Figure 5.

Rottenhammer’s patrons and collectors by city, 1595 to 1625. Created by the author with Palladio.

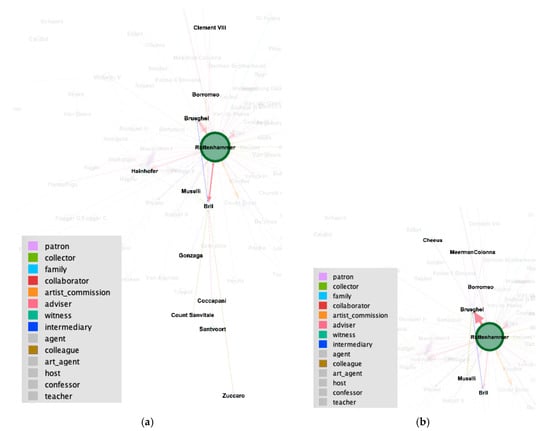

Using the open-source digital platform Gephi for visualizing Rottenhammer’s social network provides a broad and microlevel view of his network structure. Running the algorithm Force Atlas 2 in Gephi, for instance, makes apparent the formation of three to four clusters of nodes in the artist’s network (Figure 6). The clusters indicate certain communities within Rottenhammer’s network; for example, those around Sadeler J (Jan Sadeler I) were part of Rottenhammer’s Flemish artist network in Venice, as the individuals were witnesses in Sadeler’s testimonial in the lagoon city. A second community around Ott H (Hieronymus Ott), Fugger M (Marcus Fugger), and Wilhelm V is likely the German community of merchants in Venice, and the Bavarian court in Munich. Finally, the mass of nodes around Rottenhammer seems to constitute a third community; however, the visualization combined individuals from Rome, Prague, Antwerp, and Bückeburg for reasons not readily apparent. I surmise the cluster formed due to common artists and agents linking Rottenhammer to his patrons in these cities.

Figure 6.

Rottenhammer’s social network. Highest betweenness centrality indicated by nodes at brokering positions between clusters. Created by the author with Gephi.

Through statistical analysis, we gain from Gephi the nodes with the highest betweenness centrality, which measures how often a node appears on the shortest path between two nodes. This individual or node is located at a bridge or brokering position and is a potential key intermediary who facilitated Rottenhammer’s path to market. The top five bridging nodes calculated by Gephi are Rottenhammer’s collaborators Jan Sadeler I and Paul Bril, patrons Wilhelm V and Marcus Fugger, and agent Hieronymus Ott. Since I constructed the network around Rottenhammer, he was guaranteed to have the highest betweenness centrality, and thus, I have put him aside, as my goal was to locate his key intermediaries.

An examination of the types of relationships maintained at the microlevel provides a better understanding of how Rottenhammer worked with his intermediaries and patrons. For example, given that Jan Sadeler was a possible key intermediary, zooming in on his network gives indication to how Rottenhammer could have gained the patronage of Pope Clement VIII (McCabe 2019).

My findings suggest SNA and its visualization tools are part of the research process. For my project, SNA provided an analytical value in helping to realize Rottenhammer’s key intermediaries for commercial success. Even though I had considered artists as the only intermediaries in Rottenhammer’s network, SNA computational tools revealed Rottenhammer’s patrons as some of the most influential nodes in the network. Unfortunately, the individual not included in the list of influential nodes, based on the statistical calculations, is artist, collaborator, intermediary, and possible agent Jan Brueghel the Elder, who mediated the relationship between Rottenhammer and several cardinals, and likely the Antwerp collecting market. Since my network was constructed with data around Rottenhammer, it does not account for datasets around nodes not related to Rottenhammer. For example, Brueghel’s extensive network of Antwerp artists and patrons is not included in my construction, unless those artists and patrons are connected also to Rottenhammer, as we see for example with artists Paul Bril and patron Federico Borromeo. Hence, we must keep in mind the limitations of SNA in which the extent of a network remains incomplete, unless one has discrete datasets of every node in the network. As data becomes available, the dynamics of the network structure will change. Thus, SNA with its network visualization tools remains an iterative process that must work in tandem with archival documents, as well as works of art, in order to understand the context of the relationships.

In analyzing Rottenhammer’s painting market and network with digital platforms, the project raises questions about what constitutes digital art history, how digital tools may be used to construct research arguments, and what new inquiries could emerge. Johanna Drucker addressed some of the challenges for bridging the divide between art history and digital art history, i.e., “the use of analytical techniques enabled by computational technology” to produce insight in the discipline (Drucker 2013). This essay seeks to demonstrate the construction of Rottenhammer’s international market as a function of his network, namely his relationships with artist-friends and art agents, especially those in Venice’s German merchant community around the Fondaco dei Tedeschi.

My discussion is in three parts: (1) how Rottenhammer worked within the Northern European artistic community to enter the circle of leading patrons; (2) the importance of the German merchant community for Rottenhammer’s business strategy; and (3) how key intermediaries helped bring to market Rottenhammer’s name, designs, and paintings.

3. Discussion

3.1. Rottenhammer and the Northern European Artistic Community

In 1588, after his six-year apprenticeship working alongside court artists in Munich, Rottenhammer departed for Italy. A 1589 drawing of Hope and Innocence with the inscription “in Terfiss” places Rottenhammer in Treviso, near Venice, likely within the workshop of Flemish master Lodewijck Toeput (1550–1603) (Borggrefe et al. 2008). The introduction to Toeput was likely facilitated by court artist Hans von Aachen (1552–1616) whom Rottenhammer would have met in Munich. Both are documented in the ducal city during 1587 to 1588 in connection with the Penitent Magdalen, an altarpiece for St. Michael’s church for which Von Aachen provided the design and which Rottenhammer’s master Hans Donauer (c. 1521–1596) painted. After spending four years in Venice and the Veneto, Rottenhammer traveled to Rome, where he entered the entourage of Flemish landscape specialist Paul Bril (1554–1626), who was known to open the doors for other Northern European artists (Ruby 1999). There, Rottenhammer also met Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625).

Bril was established in the city as a leading landscape painter since the late 1580s for Sixtus V (Ruby 1999), and Brueghel, who arrived in 1592, had gained the support of a circle of cardinals, including Ascanio Colonna and Federico Borromeo (Honig 2016). Joining the community of Northern European artists in Rome was a standard activity for all artists north of the Alps. What made Rottenhammer’s association with Bril and Brueghel significant was that the three artists worked collaboratively on copper paintings (Peltzer 1916; Ertz and Nitze-Ertz 2008–2010; most recently, Honig 2016). Elizabeth Honig’s study of 16th- and 17th-century collaborative paintings demonstrated how each artist involved in a “high-level” collaboration—that is, a work produced by two or more illustrious artists—had an identifiable personal style recognized and appreciated by its beholders (Honig 1998, p. 188). In the case of Rottenhammer and the Flemish landscape specialists, the former painted glowing figures with softly mannered features, while the latter—Bril or Brueghel—executed the highly detailed and precise landscape elements. Their collaborative process comes down to us from Ridolfi, who reported that Rottenhammer in Venice made “figures in copper, sending them afterwards to Paul Bril in Rome, in order to have him paint the landscapes” (Ridolfi [1648] 1965). The collaborations proved to be building blocks for Rottenhammer’s career and international success. Since the landscape specialists were both supported by the prelate, working with Bril and Brueghel remained strategic for Rottenhammer as he gained invaluable access to leading patronage circles. Federico Borromeo was one of the earliest patrons to appreciate the distinctive qualities of paintings on copper, and collected pictures by Rottenhammer and Brueghel, and Bril. Spiritual value gained from Rottenhammer’s collaborative paintings, for example, was first discussed by Borromeo in his 1625 treatise Musaeum (Borromeo 2010; Jones 1988; McCabe 2019).

On 10 October 1596, after his return to Antwerp, Jan Brueghel wrote to Borromeo in praise of “that German”, referring to Rottenhammer as the two artists worked closely and collaboratively even after each returned to their respective cities. Brueghel noted: “I have been everywhere in Holland and Flanders to look at painting of [our countrymen], but I really did not find anything close to that of Italy and of that German: for this reason, I implore Your Grace to hold his things in the very highest esteem” (Crivelli 1868). The letter implies the importance of friends and intermediaries in Rottenhammer’s network for establishing his career. A year later, in April 1597, Rottenhammer wrote to the cardinal in response for the latter’s request to find a painter who could produce a portrait of the church fathers (BA n.d.; Jones 1988). The letter indicates that Rottenhammer indeed had established a relationship with the cardinal, likely through Brueghel’s intermediation. It also signals Rottenhammer’s early entry into the role of the art agent.

That artists negotiated multiple roles as artist, intermediary, art agent, or even ambassador and spy was not uncommon (Keblusek 2011). Paul Bril functioned as an agent for Borromeo and intermediary for Rottenhammer in 1601 when negotiating the latter’s delivery. Bril, charged by the cardinal to send instruction to Rottenhammer in Venice for a painting, received the panel in Rome and presumably shipped it to the cardinal, who had returned to Milan by then (Jones 1988). Bril’s letter to the cardinal on 28 July 1601 praises Rottenhammer’s work, and also deferred to his patron’s wishes:

… the small painting arrived to me in hand, which is beautiful, and is made with excellence, and the painter asked for his production forty scudi, however, Your Most Illustrious Lordship, if you desire that I send to him, how much it is in the spirit of Your Most Illustrious Lordship to spend, and from everything he will remain of service to give me notice.(BA n.d.; Bedoni 1983)

The subject matter, while unidentified in the letter, likely depicted holy figures on a copper panel, perhaps an Archangel Michael (Borggrefe et al. 2008). That Borromeo commissioned a painting from Rottenhammer suggests not only that Borromeo valued the artist’s work, and wanted to add another copper panel by him into his growing cabinet collection, but also that Rottenhammer’s business increased so much for copper paintings that the artist felt confident enough to request a price of 40 scudi. This fee was higher than the 35 scudi Bril asked for in 1607, according to the agent Papirio Bartoli (BA n.d.; Bedoni 1983).

Rottenhammer’s access to leading patrons appeared to come directly from his collaborations with Brueghel or Bril, as several collaborative paintings were acquired by patrons who favored the two Flemish artists. A Christ in Limbo (1594) painted with Brueghel is in the collection of Ascanio Colonna (Honig 2016), and a Dance of Nymphs executed with Bril had belonged to Bril’s patron, Ferdinand Gonzaga I, Duke of Mantua (Ridolfi [1648] 1965; Ruby 1999). I suggest also that Borromeo as a patron helped to introduce Rottenhammer’s works indirectly to collectors. As a leading patron of art and a supporter of Rome’s Accademia di San Luca, Borromeo’s thoughts about art were influential, and the admiration for the work of Rottenhammer’s collaborations expressed in his writings undoubtedly helped to create interest in it among other collectors. One of Rottenhammer’s Rest on the Flight into Egypt copper panels—“a small landscape by Paolo Brill with the Madonna going to Egypt by Rothenhammer, a rare thing”—was in the collection of Count Sanvitale in Parma, as described by agent Gabriello Balestrieri in 1640 to his patron Bishop Coccapani (Bedoni 1983). My working hypothesis for Borromeo as an intermediary connects the cardinal to bishops and other prelates who also collected works by Rottenhammer. Not surprisingly, then, the network visualization indicates another important patron, Wilhelm V, as a bridging node and thus intermediary for Rottenhammer’s success.

My research shows that artists worked with their patrons as artist and artist–agent, and their collaborators as intermediaries. A microlevel examination of Rottenhammer’s network structure from Figure 6 should indicate the multiple types of relationships Rottenhammer maintained with Borromeo, Brueghel, and Bril. However, Gephi combined the various types of connections between two nodes into one weighted connection, thereby removing the discrete relationship types (Figure 7). While the weighted edges indicate the strength of the connection between Rottenhammer and Bril, Brueghel, or Borromeo, the different types of relationship, or the nuances of the edges, are omitted. For example, Bril’s letter to Borromeo in 1601 indicates that the Flemish artist functioned as an intermediary for Rottenhammer. But since Bril and Rottenhammer were also collaborators, Gephi collapsed their multiple relationships into one, noting simply the collaborative relationship, as shown in Figure 7a.

Figure 7.

Microlevel view of Rottenhammer’s network structure, connected to (a) Paul Bril’s network, and (b) Jan Brueghel the Elder’s network. Created by author with Gephi.

3.2. Rottenhammer and German Merchant Community

Established since 1228, the Fondaco dei Tedeschi operated as a customs house and temporary lodging for German merchants. Venice’s German community commissioned leading artists for decoration, notably Albrecht Dürer, who painted the Feast of the Rose Garlands altarpiece for the German Brotherhood in Venice in 1506. In the sixteenth century, the Fondaco’s walls were covered with frescoes by Giorgione, Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto (Roeck et al. 1993).

One of the key players in Rottenhammer’s career was the Ott family of agents, whose members held co-consul positions at the Fondaco from 1546 to 1606 (Simonsfeld 1887; Martin 1995, p. 535). David Ott and his sons Hieronymus and Christoph handled the affairs of the Fugger merchant firm in Venice. A clear connection existed between Rottenhammer and the Ott agents through Duke Wilhelm V of Bavaria and Hans Fugger, as the Fuggers provided enormous loans to princely rulers, including the Bavarian dukes and the Habsburg imperial family. Producers of fustian textiles, the Fuggers began amassing large stakes in mining production in the fifteenth century. By constructing credit agreements with dukes and emperors for a share of metal produced from the mines, Jakob Fugger “the Rich” (1459–1525) developed the model for the family enterprise in 1485 with a loan to the Habsburg Archduke Sigismund, which was to be repaid by silver from the Tyrolean mines. By 1523, the Fuggers formed part of the monopoly that divided the copper trade in Europe (Häberlein [2006] 2012). In 1583, David Ott arranged the sale of the Fugger mining products, delivering copper and lead from Tyrol to Venice (Backmann 1997). The Ott family negotiated for Hans Fugger not only copper, fresh fish, and fruits, but also art objects (Lill 1908; Martin 1995). Their relationship remained close, as Hieronymus Ott recommended his wife, sons, and a brother in Augsburg to the protection of Marx Fugger in his 1602 testament (Backmann 1997).

As an apprentice at the Munich court, Rottenhammer would have been well aware that the ultramarine, red, green, and yellow ochre pigments came from Venice, as recorded by the ducal librarian Wolfgang Pronner in his ledger, the “Pronner’sches Malbuch” (Maxwell 2011). Ursula Haller’s study of Pronner’s revenues and accounts book is an invaluable source of information for use in reconstructing the artistic materials, sources, trade routes, and intermediaries for painting at court under Wilhelm V, for it demonstrates connections between the Ott agents and the Bavarian court (Haller 2005). On 22 July 1586, Pronner received pigments and “laca fina” from Venice sent via Starnberg and paid for by one “Cristoff Ott” (Haller 2005). Rottenhammer could have learned of Christoph’s name as an agent in Venice in connection with the Bavarian court before leaving for Italy. Nevertheless, given that he was likely armed with a ducal introduction, as the duke sent his artists for further training in Italy (Schlichtenmaier 1988), Rottenhammer remained in a position to seek help from the Ott agents in Venice. In this period, Hieronymus Ott was at the final stages of mediating a commission for an allegorical cycle of paintings by Paolo Fiammingo for Hans Fugger’s Kirchheim castle. On 15 February 1592, Fugger wrote to Ott in Venice, stating, “The two paintings by Paulo Fiamingo I am prepared for…when he has finished them. If they do not forget me, as similar artists do who have too much work” (Lill 1908, p. 144). Evidently, Fugger was none too pleased with Paolo’s repeated delays of the cycle of the Planets; and his agent would have been aware of the frustration. Given Rottenhammer’s arrival in 1591, Ott likely introduced the young artist to Paolo Fiammingo’s busy workshop (Martin 1995; McCabe 2019).

Van Mander’s remark that Rottenhammer, upon arriving in Rome, “devoted himself to painting on plates as is customary with the Netherlanders”, suggests that Netherlandish artists were known for their finely painted copper panels by 1604 (van Mander and Miedema 1994–1998, p. 442). The technique of fine painting on a small surface appealed particularly to Netherlandish painters active in Italy. The durability of the metal and ease of transport of the panels helped to make the copper painting a product available for the art market (Phoenix Art Museum 1999). However, for Rottenhammer, I argue, the significance of using copper as a support was more than simply for its painting aesthetic, or for its ease of shipping. Rather, it was the Southern German merchants’ investments in the copper metal trade and their vertical integration into the refining of the metal and monopoly of the European trade which helped to direct Rottenhammer towards this specialization (McCabe 2019). By late sixteenth century, Rottenhammer could utilize the existing infrastructure of transportation of goods shipped from the city, as mediated by the German agents Hieronymus and Christoph Ott. Sibylle Backmann’s rich archival work has highlighted the control maintained by the Ott family in the long-distance trade of luxury goods, specifically in the access to transportation. In c. 1567, when antiquarian and competing agent Jacopo Strada wanted to send multiple boxes with art objects from Venice to Munich for his patron Duke Albrecht V, David Ott blocked the transport of goods with the excuse that he found no wagoner available (Backmann 1997, p. 182).

3.3. Rottenhammer’s Painting Market and the Artist–Agent Model

Rottenhammer returned to Venice by autumn 1595 and established a successful studio in the lagoon city. He already had two assistants by then—Hans Freyberger and Georg Donauer from Munich, as documented in testimonials in September 1596 for Rottenhammer’s marriage (Hochmann 2003). The artist likely joined the Venetian painters’ guild shortly after he married. As a member of the guild, he could open a workshop in the city, as demonstrated by an entry in the 1599 Venetian magistrate records in which “Geronimo Sender tedesco” entered the studio of “Jan Rothenamer” (Sapienza 2013). From late 1595 to 1606, Rottenhammer produced not only copper paintings but also ceiling decoration and altarpieces for patrons north of the Alps, such as Emperor Rudolf II, Duke Wilhelm V, Count François Perrenot de Granvelle, Count Ernst of Holstein-Schaumburg, the Fugger family, and merchants in Venice, Antwerp, and Amsterdam.

As the richness of his patronage network demonstrates, Rottenhammer elected to remain outside the exclusive service of any one court (McCabe 2019). Unlike his contemporaries Hans von Aachen and Joseph Heintz, who worked for the Prague imperial court, Rottenhammer followed the Roman artist attitudes of controlling one’s own production. As discussed by Patrizia Cavazzini, successful artists in Rome maintained multiple avenues of revenue with different types of patrons, in lieu of being obligated to a single patron, which appeared too restrictive since one’s entire artistic production was reserved for the same person (Cavazzini 2008). Indeed, Paul Bril worked for various popes and cardinals, but he also used Flemish merchants as conduits for his painting business, as noted by Baglione (Baglione 1642; Cavazzini 2008, p. 146). Rottenhammer used similar marketing strategies, as he emulated Bril in this fashion, taking advantage of comparable opportunities in Venice with the use of his artist-friends as intermediaries and the German agents around the Fondaco dei Tedeschi. Rottenhammer’s marketing strategies included products for an anonymous general market, akin to Bril and Brueghel. (Cavazzini 2008; Honig 2016).

3.3.1. Rottenhammer’s Unknown Collectors (The Anonymous Market)

Based on correspondences, reports, ledgers, and the paintings themselves, from about 1595 until his death in 1625, Rottenhammer produced copper paintings, altarpieces, ceiling decoration, and canvas easel paintings. A summary of his work, both extant and lost or destroyed, shows that 65% of his painting market consisted of known patrons and collectors, while the remaining 35% went to unknown collectors (Table 1). Presumably most of the unknown collectors were part of the anonymous market that bought Rottenhammer’s copper paintings. Of Rottenhammer’s 105 copper paintings (extant and lost), almost 90% were produced in Italy.

Table 1.

Rottenhammer’s painting market by support material and patrons.

Rottenhammer, Bril, and Brueghel cultivated the taste for copper paintings with their successful formula of istoria painting (McCabe 2019; Borggrefe et al. 2008). Copper paintings entered the Kunstkammer and cabinet collections of the late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-centuries, where the small-format paintings were appreciated and studied alongside sculptures, seashells, coins, and other naturalia and artificialia as seen in Van Haecht’s painting (Figure 3). The rise of cabinet collections helped to foster the market for copper paintings to anonymous buyers.

A further glimpse into the anonymous market emerges when we examine Rottenhammer’s themes. The most popular paintings among the anonymous buyers were themes of The Rest on the Flight to Egypt, Holy Family with Child Baptist, and Diana and Actaeon. Rottenhammer produced at least four versions of Rest on the Flight to Egypt with Brueghel, and at least two with Bril. Rottenhammer’s figures for the collaborations with Brueghel are almost identical: the Holy Family are placed at the bottom right corner of the composition with the Virgin nursing the Christ Child, and Joseph tending to the ass, left in reserve for Brueghel to complete (Honig 2016) (Figure 8). I suggest prints made after Rottenhammer’s designs, such as The Rest on the Flight to Egypt engraved by Crispijn van de Passe, helped bring Rottenhammer’s name and work to the anonymous market. The Sadeler family—Jan I, Raphael I, Aegidius II, and Justus—and Lucas Kilian were frequent collaborators, producing the highest number of engravings after Rottenhammer’s designs (McCabe 2019).

Figure 8.

Hans Rottenhammer and Jan Brueghel the Elder, Rest on the Flight to Egypt, c. 1595. Oil on copper. Mauritshuis, The Hague, Inv. 283. https://www.mauritshuis.nl/en/explore/the-collection/artworks/rest-on-the-flight-into-egypt-283/. Used by permission.

3.3.2. Rottenhammer’s Leading Patrons—Artists as Intermediaries

While about half of the copper paintings went to anonymous collectors, the other half is attached to leading seventeenth-century patrons. My analysis of the data shows that 55 copper paintings appeared in 23 known collections in Venice, Verona, Milan, Antwerp, Amsterdam, Besançon, Prague, Vienna, and parts of Germany during the seventeenth century. In other words, about half of Rottenhammer’s copper painting market comprised of only 23 patrons and collectors, such as the aforementioned princely rulers, various cardinals, and merchants.

The international scope of Rottenhammer’s patrons, the different types of patrons, and the various types of paintings indicate the artist maintained different means to markets. For princely patrons and cardinals, as I have already suggested, Rottenhammer gained access through working relationship with collaborators or artist-friends. For instance, the Prague inventory of 1648 documents ten paintings by Rottenhammer, including a “Göttermahl (banquet of the gods)” (Granberg 1902; Schlichtenmaier 1988), probably referring to the Banquet of the Gods with the Marriage of Bacchus and Ariadne, signed and dated “Giov. Rotnhamer F. 1602” (Christie’s Paris, sold 21 June 2012, Lot 15; The Brueghel Family Database n.d.). Such a painting was lauded by Ridolfi, who noted Rottenhammer received 500 scudi for it (Ridolfi [1648] 1965).

Rottenhammer had trusted friends and intermediaries at court. Hans von Aachen and Joseph Heintz, could have provided him with an introduction to the imperial collection. That the painting “resulted in many commissions,” according to Ridolfi, suggests Rottenhammer’s social capital increased through the emperor’s patronage.

Rottenhammer’s path to collectors in the art market was also enabled by his intermediaries. His Last Judgment in Willem van Haecht’s painting raises questions about the artist’s social status and the intermediaries involved who brought the work to the attention of the Antwerp market, and its artists. For possible answers, we must look to Rottenhammer’s artistic network.

Brueghel returned to Antwerp in 1596 but would continue his collaborative partnership with Rottenhammer through 1608. Since Rottenhammer sent unfinished panels to his collaborators, as suggested by Ridolfi, he could have easily included his own paintings in a shipment to Jan in order to find a discerning collector. Brueghel’s two Last Judgment paintings, signed 1601 and 1602, indicate a deep knowledge of Rottenhammer’s work in that they present horizontally the figures and composition of Rottenhammer’s vertical panel (Honig 2016; Borggrefe et al. 2007; Brueghel Family Database n.d.). Thus, Brueghel could have functioned as an agent to help Rottenhammer to locate a suitable patron for his painting (Honig 2016; Borggrefe et al. 2007). Through Brueghel or other landscape painters in Antwerp—as Rottenhammer seemed to have used assistants in Brueghel’s workshop for landscape details (The Brueghel Family Database n.d.)—Rottenhammer gained a market for his paintings in the city. A second significant collector here was jeweler and merchant Diego Duarte II. His collection of Flemish, Dutch, German and Italian master paintings included Rottenhammer’s Fall of Phaeton (1604), described by Constantijn Huygens II on his visit to the house of Duarte in 1676: “[i]n a small cabinet at the bottom there is a piece by Rottenhammer where there are many naked figures, the best that I have ever seen of the masters” (Meijer 2003). Twelve more Antwerp collectors emerge from the extensive study of inventories completed by Erik Duverger, including sales from Georges Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, to Marcelis Librechts de Jonge and William Widdrington, merchant–alderman Jan van Meurs, as well as Jan Gillis, silversmith (Duverger 1984). Notably, a Children’s Dance by Rottenhammer and Brueghel is listed in the inventory of Nicolaas Cornelis Cheeus, merchant and patron of Jan Brueghel the Elder (Honig 2016). Given Brueghel’s connections to Cheeus and Van der Geest, whether directly or indirectly through his friend Rubens—who was favored by Van der Geest and is represented in the Van Haecht painting (Held et al. 1982)—Brueghel appears a key intermediary of Rottenhammer for the Antwerp market. Further provenance research will be necessary to determine if the paintings from the Antwerp inventories correspond to lost or existing Rottenhammer works. Thus, at this time, the Rottenhammer paintings listed in the Duverger inventories, except for Fall of Phaeton owned by Duarte and today at the Mauritshuis, The Hague, were excluded from my dataset.

3.3.3. German Agents as Art Agents

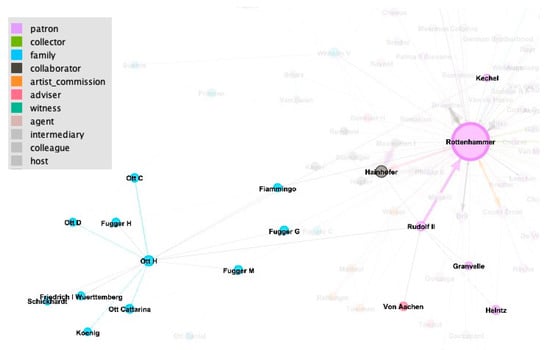

Not only did Rottenhammer utilize his artist-friends as intermediaries and agents, but he also delved into the resources at his disposal in Venice. From 1600 to 1606, Hieronymus and Christoph Ott, I argue, operated as key nodes in Rottenhammer’s network. A closer view of the network visualization from Figure 6 shows Hieronymus Ott in a brokering position with his various patrons and colleagues, one of whom was the German merchant Hieronymus Kechel (Figure 9). A 1657 inventory conducted in Venice for his son Caspar Kechel lists three copper panels by Rottenhammer, including a “Portrait of the Signore Chechel, father of Signore Casparo, framed in partly gilded carving, by the hand of Hans Rottenhammer” (Schlichtenmaier 1988). That Rottenhammer painted a portrait of Kechel indicates the artist was commissioned for the work. Although Rottenhammer likely encountered the merchant at the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, I argue it was the Ott agents who strengthened this relationship, for Kechel hailed from Ulm, the same city from which the patriarch David Ott originated. This commonality helped to cement their working relationship, which benefitted Rottenhammer. As co-consuls of the Fondaco, the Otts represented the German merchant community in handling negotiations with the Venetian State and thus exerted great influence among the German merchants themselves. Since the Germans were allowed to govern themselves in the Fondaco (Calabi and Keene 2007), Rottenhammer seemed to have worked within the system of the German merchant network in order to gain commissions in Venice.

Figure 9.

Microlevel view of Rottenhammer’s network structure, connected to Hieronymus Ott (Ott H). Created by author with Gephi.

In 1606, after Hieronymus Ott brokered the sale of Dürer’s Feast of the Rose Garlands from the German Brotherhood to Rudolf II, Rottenhammer was awarded the commission to paint the replacement altarpiece (Martin 2006). As leading members of the German merchant community, the co-consuls of the Fondaco would have actively recommended an artist for this high honor. Christoph Ott was co-consul during this period, 1605–1606. Although he died on 8 March 1605, his brother Hieronymus, who continued as the head of the firm until his death on 6 October 1606 (ASPV n.d.), likely put forth the artist’s name to the German Brotherhood. Not only did the Otts facilitate introductions to German merchants in Venice, they could also bring Rottenhammer’s paintings along to fairs in Frankfurt and Leipzig, which they frequented, in order to introduce the artist’s work to the art market (Backmann 1997). The mutually beneficial working relationship between the artist and his agents supported his copper painting enterprise.

3.4. Rottenhammer’s Return to Germany: Business as Usual and Continuation of the Artist–Agent Model

After seventeen years in Italy, Rottenhammer returned to Germany with his family, settling in Augsburg by July 1606. He continued producing copper paintings, albeit at a lower number than previously, and increased his production of altarpieces and ceiling paintings, especially for Augsburg patrons such as the Fugger family. Based on the locations of known patrons and collectors, I argue that after his move, Rottenhammer’s business strategy was to maintain some of the same key nodes gathered from Italy. The four cities that Rottenhammer supplied from both Venice and Augsburg, that is, before and after 1606, were Antwerp, Munich, Bückeburg, and Vienna (Figure 5). In these cities lived his collaborators, colleagues, and patrons.

Until about 1610, Rottenhammer continued to work with the same intermediaries and patrons he had established while in Italy. Brueghel in Antwerp and Bril in Rome maintained collaborative and intermediary activities for copper paintings. The Sadeler family of engravers, whom Rottenhammer likely met in Munich during his apprenticeship years, became close business partners with the artist in Venice. They produced engravings after his designs, and he served as a witness in a testimonial for Jan Sadeler I (ASV n.d.; Sénéchal 1987; McCabe 2019). The names “Giovan Rottahamer” and “Raffaelle Sadoller” appearing on the Venetian document demonstrate the level of friendship and trust Rottenhammer established with the Sadeler family. Jan may have also been the intermediary who brought Rottenhammer’s Coronation of the Virgin, today in London’s National Gallery, to Rome for Clement VIII (McCabe 2019). Raphael Sadeler returned to Munich in 1604 and would be a viable resource in the ducal city. Rottenhammer’s altarpiece of St. Mauritshuis for Duke Wilhelm V emerged in this year, suggesting Raphael’s reappearance at court as a likely stimulus.

For Vienna, however, the situation is not as simple as it appears. A commission from Eleonora Gonzaga I, the wife of Emperor Ferdinand II, was never delivered, even though Ottheinrich Fugger functioned as the intermediary for the emperor (Hauser 1986). The paintings in the collection of Eugene of Savoy (1663–1736), while executed before 1606, could not have entered his collection until after Rottenhammer’s death in 1625.

Rottenhammer’s patronage support from the Bavarian duke and Count Ernst of Holstein-Schaumburg in Bückeburg, gained before 1606, continued after he relocated to Augsburg. For Count Ernst, Rottenhammer executed an allegorical cycle of The Four Elements as canvas ceiling decoration in Venice, as well as monumental decoration after his return to Germany. Rottenhammer also operated as an artist–agent for the count, locating the imperial sculptor Adrien de Vries to produce a baptismal font for Bückeburg’s cathedral, as indicated in Rottenhammer’s 1613 correspondence (Peltzer 1916). In the same letter, the artist suggested to have Augsburg patrician and humanist Marcus Welser provide the iconography for a decoration program. These activities suggest Rottenhammer moved within elevated circles at the imperial court, and within Augsburg. We know from Augsburg agent Philipp Hainhofer (1578–1647) that Rottenhammer served as an agent for Emperor Rudolf II while in Venice, seeking Venetian master works, “repaired and covered them with fresh varnish”, before sending them to court (Doering 1894; Borggrefe 2007). Rottenhammer also acted as an independent art dealer, buying Venetian paintings by Veronese and other masters for sale in Germany, as indicated by his friend and imperial artist Joseph Heintz in a 1606 letter to Count Ernst (Zimmer 1988; Borggrefe 2007).

From July 1610, Rottenhammer began working closely with Hainhofer, thus gaining another resource for patronage in distant lands, for Hainhofer’s patron was Duke Philipp II of Pommern-Stettin (HAB n.d.; Doering 1894; Schlichtenmaier 1988). In addition to his designs and paintings, Hainhofer valued the artist’s status and longstanding relationships with his artist-friends (McCabe 2019). His weekly reports to Duke Philipp II indicate the art agent’s dependence on Rottenhammer as an intermediary and agent, as expressed in a letter dated 28 July 1610, in which the agent wrote, “The other two [Bril and Brueghel] I know not personally, but Rottenhammer has good correspondence with Bril” (Doering 1894). Two months later, “if Your Grace wishes, I will through Rottenhammer order from him [Bril]” (Doering 1894). While the network visualization indicates Hainhofer is connected to Bril, it does not show that Rottenhammer functioned as the intermediary and agent. In order to understand Rottenhammer’s significance in Hainhofer’s relationship with Bril, it remains necessary to return to the archival document, namely, Hainhofer’s report.

4. Conclusions

That Rottenhammer maintained few patrons in Venice during the height of his copper painting production tells us something very important about how he engaged with his resources. In the lagoon city, Rottenhammer utilized artist-friends and German agents as key nodes for his business enterprise. The intermediaries and agents marketed his copper paintings to different cosmopolitan centers. After Rottenhammer returned to Germany, he continued to maintain working relationships with some of the same key intermediaries. Comprised of trusted friends and collaborators—Jan Brueghel the Elder, Paul Bril, Hans von Aachen and Joseph Heintz, the Sadelers, the Ott brothers, and Philipp Hainhofer—Rottenhammer’s intermediaries and agents commanded high social status and positions in Venice, Rome, Antwerp, Prague, Munich, and Augsburg, where they lived and enjoyed relationships with the nobility in both court and city.

Digital technologies aided in the construction of my argument for how Rottenhammer established his business of art with the use of intermediaries and agents. The open-source platform Palladio presented clearly the cities Rottenhammer served during and after his time in Venice. The open-source platform Gephi visualized Rottenhammer’s network structure in order to determine the possible key intermediaries Rottenhammer employed to enter these markets. Between the primary data of historical documents and works of art, to the mapping and network visualization tools, my project demonstrates that a combined approach—in which the content and context of historical documents work in tandem with computational analysis and visualization—remains the most effective approach for digital art history. The challenge of the project, and likely any digital humanities project, is the steep learning curve of various digital platforms. Therefore, in order to work effectively in this realm, art historians would do well to locate a collaborator with expertise in computational technology and in the digital platform most appropriate for the project’s needs and goals.

Funding

My dissertation project, from which this article stems, would not have been possible without the support of the German-American Fulbright Commission in 2015–2016 for research in Germany, the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation in 2016–2017 for research in Venice, and the Albert and Elaine Borchard Foundation for additional research in 2017.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the archivists, curators, and conservators from the institutions, archives, and museums across Germany and Venice in which I conducted research. I’m especially grateful to the Herzog August Bibliothek, the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, and the Centro Tedesco di Studi Veneziani for their generosity and support. For help with ArcGIS and Gephi, I thank the Interdisciplinary Research Collaboratory at University of California, Santa Barbara, in particular Tom Brittnacher. My research benefitted from exchanges with numerous scholars, including Matthias Roick, Mara Wade, Gillian Bepler, Elizabeth Harding, Volker Bauer, Romedio Schmitz-Esser, Tracy Cooper, and Bernard Aikema. I am deeply grateful to my dissertation advisors Mark A. Meadow and Robert Williams (in memoriam), and committee members E. Bruce Robertson and Michael North for their advice, guidance, and support. Finally, I thank this journal’s editors and anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aikema, Bernard, and Beverly Louise Brown, eds. 2000. Renaissance Venice and the North: Crosscurrents in the Time of Bellini, Dürer and Titian. New York: Rizzoli. [Google Scholar]

- Archivio di Stato di, Venezia. n.d. Archivio Notarile, Giulio Figolin, Atti, 5902, 1603 II, folios 300r-301r.

- Archivio Storico del Patriarcato di, Venezia. n.d. Liber mortuorum 1574–1665, fol. 150; fol. 391.

- Biblioteca, Ambrosiana. n.d. G188inf, 67; G197inf, 111.

- Backmann, Sibylle. 1997. Kunstagenten oder Kaufleute? Die Firma Ott im Kunsthandel zwischen Oberdeutschland und Venedig (1550–1650). In Kunst und ihre Auftraggeber im 16. Jahrundert. Venedig und Augsburg im Vergleich. Edited by Klaus Bergdolt, Jochen Brüning and Andrea Hilbk. Berlin: Akademie, pp. 175–97. [Google Scholar]

- Baglione, Giovanni. 1642. Vita di Paolo Brillo Pittore. In Le vite de’ pittori, scultori et architetti: dal pontificato di Gregorio XIII del 1572 in fino a’tempi di Papa Vrbano Ottauo nel 1642. Available online: https://archive.org/details/gri_vitedepittor00bagl/page/n217 (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Bedoni, Stefania. 1983. Jan Brueghel in Italia e il collezionismo del Seicento. Florence: pp. 105, 178. [Google Scholar]

- Borggrefe, Heiner. 2007. Hans Rottenhammer and His Influence on the Collection of Rudolf II. Studia Rudolphina 7: 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- Borggrefe, Heiner, Vera Lüpkes, Lubomír Konečný, and Michael Bischoff, eds. 2007. Hans Rottenhammer (1564–1625): Ergebnisse Des in Kooperation Mit Dem Institut Für Kunstgeschichte Der Tschechischen Akademie Der Wissenschaften Durchgeführten Internationalen Symposions Am Weserrenaissance-Museum Schloss Brake (17.-18. Februar 2007). Marburg: Jonas, ISBN 9783894453954. [Google Scholar]

- Borggrefe, Heiner, Lubomír Konečný, Vera Lüpkes, and Vit Vlnas, eds. 2008. Hans Rottenhammer: Begehrt—Vergessen—Neu Entdeckt. Munich: Hirmer, ISBN 3777443158. [Google Scholar]

- Borromeo, Federico, Kenneth Rothwell, and Pamela M. Jones. 2010. Sacred Painting; Museum. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 173, 181. ISBN 9780674047587. [Google Scholar]

- Brosens, Koenraad. 2012. Can tapestry research benefit from economic sociology and social network analysis? In Family Ties: Artistic Production and Kinship Patterns in the Early Modern Low Countries. Edited by Koenraad Brosens, Leen Kelchtermans and Katlijne Van der Stighelen. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Brosens, Koenraad, Klara Alen, Astrid Slegten, and Fred Truyen. 2016. MapTap and Cornelia Slow Digital Art History and Formal Art Historical Social Network Research. Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 79: 315–30. [Google Scholar]

- The Brueghel Family Database. n.d. Jan Brueghel the Elder. Available online: https://www.janbrueghel.net/ (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Burt, Ronald S. 2007. Brokerage and Closure: An Introduction to Social Capital. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 16–17. ISBN 9780199249152. First published 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Calabi, Donatella, and Derek Keene. 2007. Merchants’ lodgings and cultural exchange. In Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Europe Vol. II: Cities and Cultural Exchange in Europe, 1400–1700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 315–48. ISBN 9780521845472. [Google Scholar]

- Cavazzini, Patrizia. 2008. Painting as Business in Early Seventeenth-Century Rome. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, p. 123. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, James. 1988. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. The American Journal of Sociology 94: S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cools, Hans, Marika Keblusek, and Badeloch Noldus, eds. 2006. Your Humble Servant: Agents in Early Modern Europe. Hilversum: Verloren, ISBN 978-90-6550-908-6. [Google Scholar]

- Phoenix Art Museum, organized. 1999. Copper as Canvas: Two Centuries of Masterpiece Paintings on Copper, 1575–1775. New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0195123964. [Google Scholar]

- Crivelli, Giovanni Francesco. 1868. Giovanni Brueghel Pittore Fiammingo o sue Lettere e Quadretti Esistenti Presso l’Ambrosiana per G. Crivelli. Milan: Ditta Boniardi-Pogliani Di Ermeneg. Besozzi, p. 7. Available online: https://archive.org/details/giovannibrueghel00criv/page/7 (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Dacos, Nicole. 1964. Les Peintres Belges à Rome au XVIe Siècle. Brussels: Institut historique belge de Rome. [Google Scholar]

- De Marchi, Neil, and Hans J. van Miegroet, eds. 2006. Mapping Markets for Paintings in Europe 1450–1750. Studies in European Urban History (1100–1800) 6. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Doering, Oscar. 1894. Des Augsburger Patriciers Philipp Hainhofer Beziehungen zum Herzog Philipp II. von Pommern-Stettin. Correspondenzen aus den Jahren 1610–1619. Im Auszug mitgetheilt und commentiert. Vienna: C. Graeser, Available online: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100627351 (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Drucker, Johanna. 2013. Is there a ‘Digital’ Art History? Visual Sources 29: 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duverger, Erik. 1984. Antwerpse Kunstinventarissen Uit de Zeventiende Eeuw. Brussels: Koninklijke Academie voor Wetenschappen, Letteren en Schone Kunsten van België. [Google Scholar]

- Ertz, Klaus, and Christa Nitze-Ertz. 2008–2010. Jan Brueghel Der Ältere (1568–1625) Kritischer Katalog der Gemälde. Lingen: Luca Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Fantoni, Marcello, Louisa Chevalier Matthew, and Sara F. Matthews Grieco, eds. 2003. The Art Market in Italy 15th–17th Centuries. Modena: F. C. Panini. [Google Scholar]

- Goldthwaite, Richard. 1993. Wealth and the Demand for Art in Italy, 1300–1600. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Granberg, Olof. 1902. Kejsar Rudolf II:s konstkammere och dess svenska öden, och om Uppkomsten af Drottning Kristinas Tafvel-Galleri I Rom och dess Skingrande, Nya Forskningar. Stockholm: Gustaf Lindströms Boktryckeri, p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, Mark. 1973. The Strength of Weak Ties. American Journal of Sociology 78: 1360–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, Mark. 1985. Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology 91: 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häberlein, Mark. 2012. The Fuggers of Augsburg: Pursuing Wealth and Honor in Renaissance Germany. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8139-3244-6. First published 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Haller, Ursula. 2005. Das Einnahmen- und Ausgabenbuch des Wolfgang Pronner: die Aufzeichnungen des “Verwalters der Malerei” Herzog Wilhelm V. von Bayern als Quelle zu Herkunft, Handel und Verwendung von Künstlermaterialien im ausgehenden 16. Jahrhundert. Munich: Siegl, p. 184. [Google Scholar]

- Haskell, Francis. 1980. Patrons and Painters: A Study in the Relations between Italian Art and Society in the Age of the Baroque. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, Wilhelm. 1986. Ein unbekannter Brief von Hans Rottenhammer aus dem Jahre 1624. Zeitschrift des Historischen Vereins für Schwaben 80: 125–31. [Google Scholar]

- Held, Julius S. 1982. Artis Pictoriae Amator: An Antwerp Art Patron and his Collection. In Rubens and His Circle: Studies. Edited by Anne W. Lowenthal, David Rosand and John Walsh. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 34–64. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog August Bibliothek. n.d. Wolfenbüttel, Cod. Guelf. 17.23. Aug. 4°.

- Hochmann, Michel. 2003. Hans Rottenhammer and Pietro Mera: Two Northern Artists in Rome and Venice. The Burlington Magazine 145: 641–45. [Google Scholar]

- Honig, Elizabeth. 1998. Painting & the Market in early modern Antwerp. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Honig, Elizabeth A. 2016. Jan Brueghel and the Senses of Scale. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffé, Michael. 1977. Rubens and Italy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Pamela M. 1988. Federico Borromeo as a Patron of Landscapes and Still Lifes: Christian Optimism in Italy Ca. 1600. The Art Bulletin 70: 261–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keblusek, Marika, and Badeloch Noldus, eds. 2011. Double Agents: Cultural and Political Brokerage in Early Modern Europe. Leiden: Brill, ISBN 9789004215078. [Google Scholar]

- Keblusek, Marika. 2011. The Pretext of Pictures: Artists as Cultural and Political Agents. In Double Agents: Cultural and Political Brokerage in Early Modern Europe. Edited by Marika Keblusek and Badeloch Noldus. Leiden: Brill, pp. 147–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lill, Georg. 1908. Hans Fugger (1531–1598) und Die Kunst. Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, Available online: https://archive.org/details/hansfugger15311500lill/page/n6 (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- van Mander, Carel. 1969. Het Schilder-boeck (Facsimile of the First Edition, Haarlem 1604). Utrecht: Davaco Publishers, Available online: https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/mand001schi01_01/mand001schi01_01_0003.php#074 (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- van Mander, Carel, and Hessel Miedema. 1994–1999. The Lives of the Illustrious Netherlandish and German Painters, from the First Edition of the Schilder-Boeck (1603–1604). Doornspijk: Davaco, vol. I, p. 442. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Andrew John. 1995. Quellen zum Kunsthandel um 1550–1600: Die Firma Ott in Venedig. Kunstchronik 5: 535–39. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Andrew John. 2006. ‘Dan hat sich ain quarter befunden, in vnserer Capeln, von der Hand des Albrecht Dürers.’: The Feast of the Rose Garlands in San Bartolomeo di Rialto (1506–1606). In Albrecht Dürer: The Feast of the Rose Garlands 1506–2006. Edited by Olga Kotkova. Prague: Národní galerie v Praze, pp. 53–67. ISBN 9788070353325. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Andrew John. 2008. I rapporti con i Paesi Bassi e la Germania: pittori, agenti e mercanti, collezionisti. In Il collezionismo d’arte a Venezia. Vol. 2, Dalle origini al Cinquecento. Edited by Michel Hochmann, Rosella Lauber and Stefania Mason. Venice: Fondazione di Venezia and Marsilio, pp. 143–64. ISBN 9788831797146. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, Susan. 2011. The Court Art of Friedrich Sustris: Patronage in Late Renaissance Bavaria. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate, pp. 152–54. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, Sophia Quach. 2019. Hans Rottenhammer in Venice: Networking in Style between Italy and Germany. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Meadow, Mark. A. 2009. The Aztecs at Ambras: Social Network and the Transfer of Cultural Knowledge of the New World. In Kultureller Austausch: Bilanz Und Perspektiven Der Frühneuzeitforschung. Edited by Michael North. Köln: Böhlau, pp. 349–68. [Google Scholar]

- Meijer, Bert W. 2003. Disegni italiani in Olanda: Collezioni di oggi e di ieri. In Disegno e Disegni per un Rilevamento delle Collezioni dei Disegni Italiani: Giornata di studi, Firenze, 13 novembre 1999. Edited by Anna Forlani Tempesti and Simonetta Prosperi Valenti Rodinò. Florence: Leo S. Olschki, pp. 79–108. ISBN 8822252756. [Google Scholar]

- Montias, John Michael. 1982. Artists and Artisans in Delft: A Socio-Economic Study of the Seventeenth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, Erwin. 2005. The Life and Art of Albrecht Dürer. Intro. J. C. Smith. Princeton: Princeton University Press. First published 1943. [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer, Rudolf Arthur. 1916. Hans Rottenhammer. Jahrbuch Der Kunsthistorisches Sammlungen des allerhöchsten Kaiserhauses in Wien 33: 293–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ridolfi, Carlo. 1965. Le maraviglie dell’arte ovvero le vite degli illustri Pittori Veneti e dello Stato. Edited by Detlev Freiherrn von Hadeln. Rome: Società Multigrafica Editrice Somu, p. 85. First published 1648. [Google Scholar]

- Roeck, Bernd, Klaus Bergdolt, and Andrew John Martin, eds. 1993. Venedig und Oberdeutschland in der Renaissance: Beziehungen zwischen Kunst und Wirtschaft. Sigmaringen: Thorbecke. [Google Scholar]

- Ruby, Louisa Wood, and Paul Bril. 1999. Paul Bril: The Drawings. Pictura Nova 4. Turnhout: Brepols. [Google Scholar]

- Sapienza, Valentina. 2013. Tenendo quegli in casa un buon numero di Fiamminghi. In Alle origini dei generi pittorici fra l’Italia e l’Europa, 1600 ca. Edited by Carlo Corsato and Bernard Aikema. Treviso: ZeL, p. 36, fn 39 and Appendix I. [Google Scholar]

- Schlichtenmaier, Harry. 1988. Studiem zum Werk Hans Rottenhammers des Älteren (1564–1625), Maler und Zeichner mit Werkkatalog. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Sénéchal, Philippe. 1987. Les graveurs des écoles du Nord à Venise (1585–1620), Les Sadelers: entremise et entreprise. Ph.D. dissertation, Université de Paris-Sorbonne, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Simonsfeld, Henry. 1887. Der Fondaco dei Tedeschi in Venedig und die deutsch-venezianischen Handelsbeziehungen. Stuttgart: Cota, 2 vols, Appendix II. p. 208. Google Books. Available online: http://books.google.com/books?id=GSI5AAAAMAAJ&oe=UTF-8 (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Spear, Richard, and Philip Sohm. 2010. Painting for Profit: The Economic Lives of Seventeenth-Century Italian Painters. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, Jürgen. 1988. Joseph Heintz Der Ältere: Zeichnungen Und Dokumente. Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, pp. 414–15. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).