Cultural Tourism: Imagery of Arnhem Land Bark Paintings Informs Australian Messaging to the Post-War USA

Abstract

:The growing interest in and appreciation of primitive art in general and of aboriginal art in particular has a very important human, as distinct from scientific, implication. It is gradually causing persons who otherwise would either ignore or despise the aborigines to realize that a people possessing an art which is full of traditional meaning as well as expressive of many interesting motifs is much higher in the human scale than had been previously thought. The average white person is not impressed by totemism, kinship and sociological studies of aboriginal life, but a simple presentation of a native people’s art is something, which he can appreciate. I am hoping that this introduction to the decorative art of the Australian aboriginal … will contribute materially to the appreciation of the Australian aborigines both as a people possessed of artistic powers, and as human personalities. Moreover, in so far as we let the aborigines … know our appreciation, we shall help them to get rid of that feeling of inferiority for which contact with us has been responsible.

It would be a great privilege for the Museum to be able to show work of this character of the quality of Sir Baldwin Spencer’s Collection. Too many inferior examples of this art have been seen in the United States. The Museum of Fine Arts would be proud to show these infinitely superior examples which the Collection of the National Museum of Victoria boasts.28

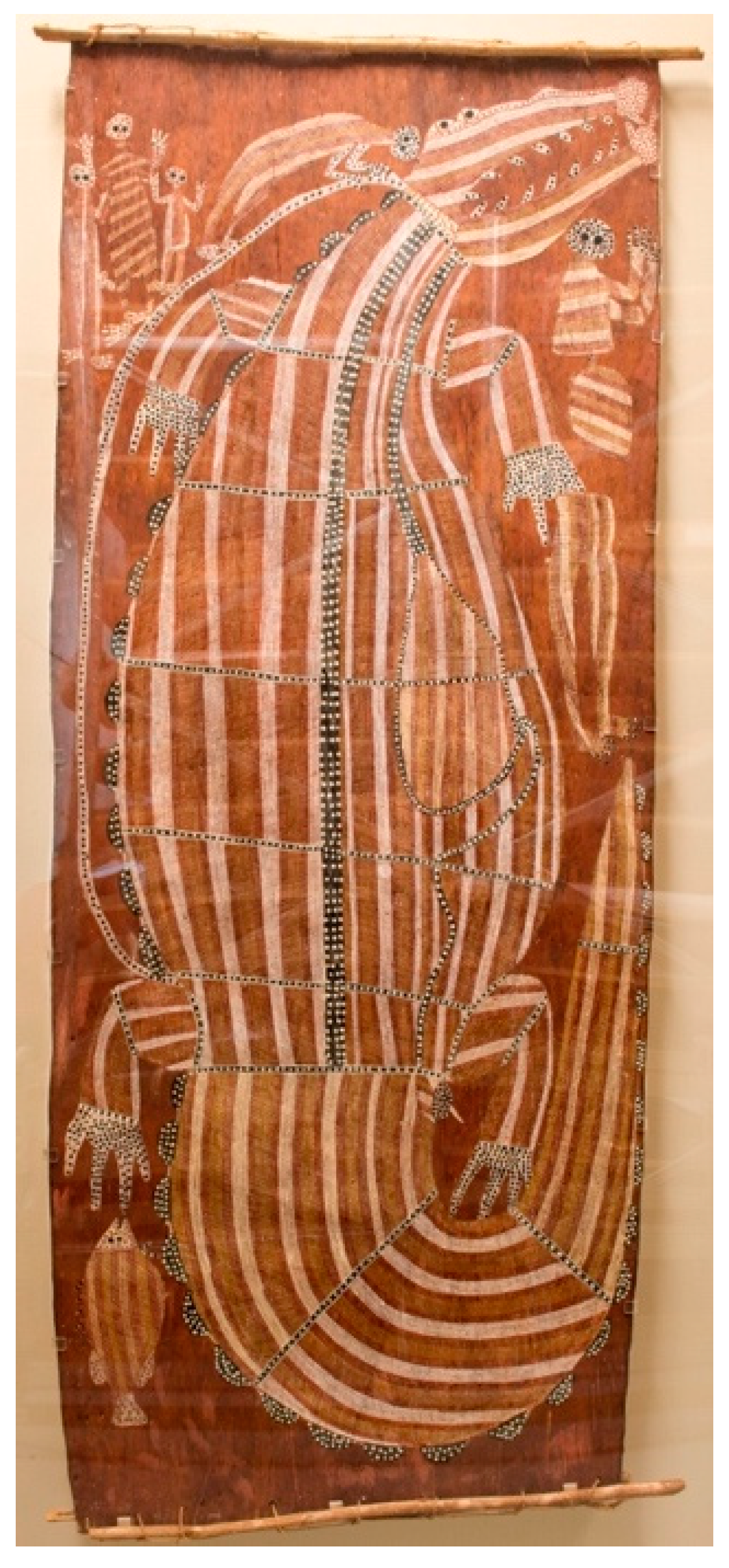

a truly magnificent one. It contains at least 4 if not 5 works by the Kakadu’s (long since extinct), some of the best Yirrkala works in existence as well as those from Oenpelli including the biggest known bark painting in existence. The Nat’l Museum trustees are now very proud of “their” show and one at least is visiting Houston to see it there.

We find clearly exemplified that innocence of eye and unselfconscious expression which artists of the twentieth century, since its first decade have been struggling to achieve—the two ideals which have given the convention bound observer the greatest difficulty in approaching contemporary art. These qualities are illustrated to one degree or another in all so-called native artists ….

… because of the primitivism of their makers, these qualities come out for us with a particular clarity in their closeness to the primitive psychological experience—their communication of tensions among visual relationships overlaid by a minimum of readily recognizable, distracting relationships’.

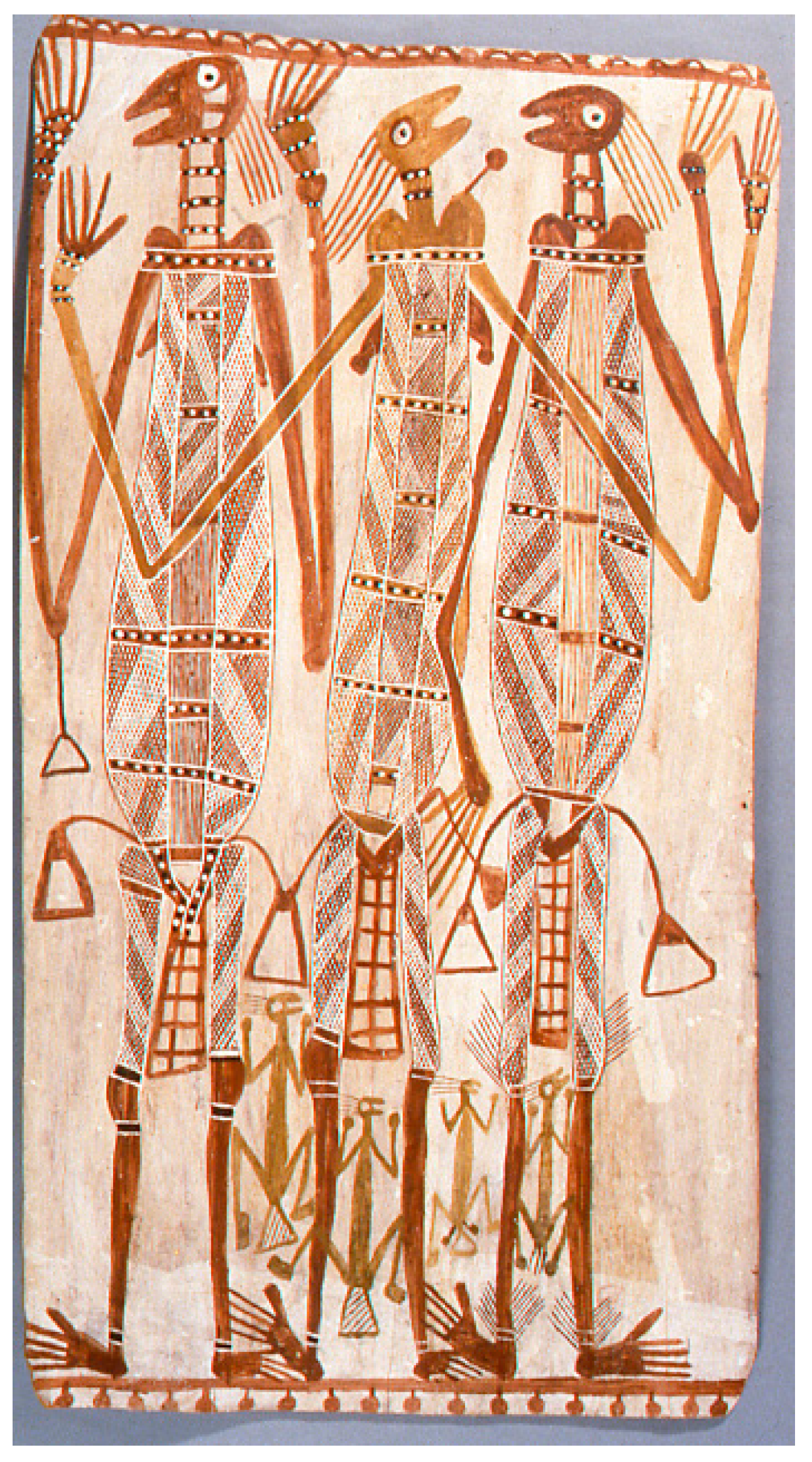

the artists often painted … their impressions of the sacred places of the clan; especially their interpretations of the water hole and its surrounding country or the artist’s “dreaming” of it.

… certainly, had something like a fully developed human brain; even more certainly he was a human being who before middle age seemed to have a larger quantity of organized material packed into that brain than any European could easily conceive—thousands of songs, hundreds of rituals, legends, stories, dances, particulars of tribal history, easy mastery of a complex kinship system and a range of difficult crafts appropriate to bush life. He was likely to know one of several languages in addition to his own, not counting the widespread sign languages’… ‘These were peoples without chiefs because everyone in some sense had his part in tribal government.

As any viewers on easy terms with the contemporary art of the Western world will readily see, a whole range of excellences available to only a lucky few of our own artists may seem to be the common birth-right of the Australian bark painters … One might suspect, in looking at good bark paintings, that the profound indifference of the aboriginals to Europeans and their material culture continues to be present today.

they carefully learned dot, line and cross-hatch patterns … [and] the intricate designs show that the art is from a primitive people…a static Aboriginal culture…[whose] people [are] in decline.

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adam, Leonhard. 1942. Draft Exhibition Proposal, Primitive Art Exhibition, 9 October, VPRS 805/P4 Inward Registered Correspondence, Unit 5, File J. North Melbourne: Public Records Office of Victoria (PROV). [Google Scholar]

- Adam, Leonhard. 1951. Aboriginal Art. In Jubilee Exhibition of Australian Art: Aboriginal Art, Early Colonial Art, the Art of the Middle Period, Contemporary Art, Organized by the Plastic Arts Committee for the Commonwealth Jubilee Celebrations. Sydney: Ure Smith. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, Leonhard. 1954. Letter to Allan McCulloch, 29 March 1954. McCulloch Papers, Collection. Melbourne: La Trobe University Library. [Google Scholar]

- Adelaide Advertiser. 1937. Aboriginal Art and National Spirit. Gallery Director Favours Wider Use. In Adelaide Advertiser; May 22, p. 16. Available online: http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/74347303?searchTerm=%E2%80%98Aboriginal Art and National Spirit.&searchLimits= (accessed on 11 June 2014).

- Allen, Louis A. 1972. Australian Aboriginal Art: Arnhem Land. Chicago: Field Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, Jon C. 1988. Aborigines, Tourism, and Development: The Northern Territory Experience. Australian National University North Australia Research Unit Monograph. Canberra: Australian National University. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, Jon, and William Saunders. 1991. From Exclusion to Dependence: Aborigines and the Welfare State. Discussion Paper, No. 1. Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Angus, George F. 1847. Observations on the Aboriginal Inhabitants of South Australia. In Savage Life and Scenes in Australia and New Zealand. London: Smith, Elder, and Co., vol. 1, p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Australian National Travel Association. 1936. Australia. Travel Brochure. Canberra: Australian National Travel Association. [Google Scholar]

- Australian National Travel Association. 1954. Attracting Tourists to Australia. Government Grants for Tourist Promotion. Report. Canberra: Australian National Travel Association. [Google Scholar]

- Australian National Travel Association. 1962. ANTA News Bulletin. Canberra: Australian National Travel Association. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1996. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Tourist Commission. 1971. Australian Overseas Visitor Statistics 1965–1970. Melbourne: Development & Research Division, Australian Tourist Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Tourist Commission. 1972. Australia. Overseas Visitor Statistics 1966–1971. Melbourne: Development & Research Division, Australian Tourist Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, Marjorie. 1941. Introduction. In Art of Australia 1788–1941/An Exhibition of Australian Art Held in the United States of America and the Dominion of Canada, Carnegie Corp. by the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Edited by Ure Smith. Sydney: Ure Smith, pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, Gillian. 2010. Aboriginal Cultural Tourism: Enterprise/Contested Mobilities and Negotiating a Responsible Australian Travel Culture. Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues 18: 116–41. [Google Scholar]

- Birch, Tony. 2010. “Nothing has changed”: The making and unmaking of Koori culture. Meanjin 69: 107–18. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Roman. 1964. Old and New Australian Aboriginal Art. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Peter, Kerry Donohue, William Montgomery McGovern, and Jan McMillan, eds. 1991. Tourism in Australia. Sydney: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, Maie. 1941. Foreword. In Art of Australia 1788–1941/An Exhibition of Australian Art Held in the United States of America and the Dominion of Canada under the Auspices of the Carnegie Corporation and the Museum of Modern Art, New York.re Smith/Compiled and Edited by Sydney Ure Smith. New York: Carnegie Corporation and the Museum of Modern Art. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, Denise, and Suzy Russell. 1941. The Responsibilities of Leadership: The records of Charles P. Mountford. In Exploring the Legacy of the 1948 Arnhem Land Expedition. Edited by Martin Thomas and Margo Neale. Canberra: ANU Press, Available online: http://www.jstore.org/stable/j.ctt24h9p1.18 (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- Christian Science Monitor. 1941. The Art of Australia. Christian Science Monitor, October 18. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Ian, and Louise Larrieu. 1998. Indigenous Tourism in Victoria. Products, Markets and Futures, Paper Presented at ‘Symbolic Souvenirs’. A One-Day Conference on Cultural Tourism at the Centre for Cross Cultural Research, Australian National University. Canberra: Australian National University. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth Railways. 1963. There and Back by Trans-Australian Railway. Library of Congress Website. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2018648013/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Craik, Jennifer. 2001. Tourism Culture and National Identity. In Culture in Australia. Policies, Publics, Programs. Edited by Bennett Tony and Carter David. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, R. Emerson. 1940. Canberra, Australia’s National Capital. Library of Congress. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2018648014/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Davidson, James. 1970. Foreword. In Australian Aboriginal Art: Louis A. Allen Collection. Santa Barbara: The Art Galleries, University of Santa Barbara. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Michael. 2007. The Depiction of Indigenous Heritage in European-Australian Writings. North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing, p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- Elkin, Adolphus Peter. 1961. Elkin Archives, Private Correspondence, 1956–1979, Items 5/2/23. Quoted in De Lorenzo 2015: 5. Sydney: Fisher Library, University of Sydney. [Google Scholar]

- Elkin, Adolphus Peter. 1966. Foreword. In Australian Aboriginal Decorative Art, 7th ed. Edited by Frederick D. McCarthy. Sydney: Trustees of the Australian Museum, pp. 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Geissler, Marie. 2017. Arnhem Land Bark Painting. The Western Reception 1850–1990. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses1/399 (accessed on 19 February 2019).

- Gray, Geoffrey. 1998. Nomadism to Citizenship: A. P. Elkin and Aboriginal Advancement. In Citizenship and Indigenous Australians. Edited by Nicholas Peterson and Will Sanders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Great Britain. n.d. BOAC Qantas, Australia New Zealand. Library of Congress Website. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2009632108/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Hall, Colin Michael. 1961. Introduction to Tourism in Australia: Development, Issues and Change. Frenchs Forest: Pearson Education Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Harris Kerr Forster and Co. 1966. Australia’s Travel and Tourism Industry 1965. Report Commissioned by Australian National Travel Association. Sydney: Stanton Robins and Co. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, Chas. H. 1938. Signed Report written for the ANTA. In Australia’s 150th Anniversary Celebrations. Reviewing the Activities of the Australian National Travel Association in Securing Publicity for the Celebrations throughout the World. Sydney: Australian National Travel Association. [Google Scholar]

- James, Rodney. 2014. The Battle for the Spencer Barks: From Australia to the USA, 1963–1968. Latrobe Journal 93–94: 181. [Google Scholar]

- Jardine, Walter. 1963. Travel–Air, Land, Sea. Book through Burns Phillip & Co. Ltd. Library of Congress Website. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2007676064/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Jordan, Caroline. 2013. Cultural exchange in the midst of chaos Theodore Sizer’s exhibition ‘Art of Australia 1788–1941’. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 13: 24–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinert, Sylvia. 2012. ‘Keeping up the Culture’: Guani Engagements with Tourism. Oceania 82: 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Noel Pasco. 1930s. Queensland Tourist Bureau, World’s Premier Wonderland, Great Barrier Reef, Queensland. Library of Congress Website. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2015647587/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude, and Monique Layton. 1963. Structural Anthropology. Translated by Claire Jacobson, and Brooke Grundfest Schoepf. New York: Basic Books, pp. 101–2. [Google Scholar]

- Lock-Weir, Tracy. 2002. Art of Arnhem Land 1940s–1970s. Adelaide: Art Gallery of South Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Lowish, Susan. 2014. Mapping Connections Towards an art history of early Indigenous Collections at the University of Melbourne. Cultural Treasures Festival Papers 1: 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lydon, Jane. 2002. Eye Contact: Photographing Aboriginal Australians. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Massola, Aldo. 1956. Aboriginal Art. In The Arts Festival of the Olympic Games Melbourne. Melbourne: The Olympic Civic Committee of the Melbourne City Council for the Olympic Organizing Committee MCMLV1. [Google Scholar]

- May, Sally K. 2000. The Last Frontier? Acquiring the American-Australian Scientific Expedition Ethnographic Collection 1948. Bachelor’s Dissertation, Flinders University of South Australia, Bedford Park, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- May, Sally K. 2008. The Art of Collecting: Charles Percy Mountford. In The Makers and Making of Indigenous Australian Museum Collections. Edited by Nicolas Peterson, Lindy Allen and Louise Hamby. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- May, Sally K. 2009. Collecting Cultures: Myth, Politics and Collaboration in the 1948 Arnhem Land Expedition. Lanham, Md: Altamira Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch, Alan. 1961. The Aboriginal Art Exhibition. Meanjin 20: 2. [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch, Alan. 1965. Introduction. In Aboriginal Bark Paintings from the Cahill and Chaseling Collections. National Museum of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia, The Museum of Fine Arts. Edited by Edmond Lehman Ruhe. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, Ian. 1998. Aboriginalism: White Aborigines and Australian Nationalism. Australian Humanities Review. Available online: http://www.australianhumanitiesreview.org/archive/Issue-May-1998/mclean.html (accessed on 24 July 2015).

- McLean, David. 2006. From British Colony to American Satellite? Australia and the USA during the Cold War. Australian Journal of Politics and History 52: 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell Library Manuscripts. n.d. Qantas Travel Reports. In Horne Papers. MLMSS32525 MLK 02153. Sydney: Mitchell Library Manuscripts.

- Morphy, Howard. 2001. Seeing Aboriginal Art in the Gallery. Humanities Research 111: 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountford, Charles. 1945. 5 March 1945. Letter to the Chairman of the National Geographic Society Research Committee. Accession File 178294. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Archives, p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mountford, Charles. 1949. Exploring Stone Age Arnhem Land. National Geographic Magazine XCV1: 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Mountford, Charles. 1956. Records of the American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land. Volume 1: Art, Myth and Symbolism. Carlton: Melbourne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mountford, Charles. 1958. The Mountford Volume on Arnhem Land Art, Myth and Symbolism: A critical Review-A Rejoinder. Mankind 5: 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountford, Charles. 1964. Aboriginal Paintings from Australia. Fontana UNESCO Art Books. New York: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences. 1950. Curtains (2). Kangaroo Hunt. Cotton, Annan Fabrics, Sydney, Australia. MAAS Website. Available online: https://collection.maas.museum/object/148770 (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Museum of Fine Arts. 1960. Search the Collection. Drawings on Bark. Houston: Museum of Fine Arts, Available online: https://www.mfah.org/art/search?q=drawing+on+bark+&page=1 (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- Nash, Dennison, ed. 2007. The Study of Tourism: Anthropological and Sociological Beginnings. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Neale, Margo. 1998. Charles Mountford and the "Bastard Barks". A gift from the American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land, 1948. In Brought to Light. Australian Art 1950–1965, from the Queensland Art Gallery Collection. Edited by Lynne Sear and Julie Ewinqton. Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery, pp. 210–17. [Google Scholar]

- Neale, Margo. 2009. Epilogue: Sifting the silence. In Margo Neale (Project Director), Birds Barks and Billabongs Symposium, National Museum of Australia’, ANU Press Website. Available online: http://pressfiles.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p116081/pdf/ch211.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- Newsweek. 1972. Art of the Abos. Newsweek, March 20. [Google Scholar]

- Northfield, James. 1930a. Koala (Native Bear) Australia, Particulars at Shipping and Travel Agencies. Library of Congress. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2015647589/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Northfield, James. 1930b. Melbourne. The Garden Capital of Victoria, Australia. Take a Kodak. Library of Congress. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2014646275/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Nugent, Maria. 2005. Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet. Sydney: Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, Tim. 1994. Key Concepts in Communication and Cultural Studies. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Michael. 1997. The Tourist Corroboree in South Australia to 1911. Aboriginal History 21: 46–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, Michael. 2002. Ah that I could convey a proper idea of this interesting wild play of the natives: Corroborees and the rise of Indigenous Australian cultural tourism. Australian Aboriginal Studies 2: 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Peat Marwick Mitchell and Co. 1972. Financing Tourist Development. A Study on Behalf of the Australian National Travel Association. Sydney: Peat Marwick Mitchell and Co., p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, Beatrice. 2011. In-Between: Contemporary Art in Australia. Cross-Culture, Contemporaneity, Globalization. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden. Available online: https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/26256/1/gupea_2077_26256_1.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2015).

- Preston, Margaret. 1925. Indigenous Art of Australia. Art in Australia, March 11. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Margaret. 1930. The Application of Aboriginal Designs. Art in Australia, March 3. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Margaret. 1941a. Aboriginal Art of Australia. Art in Australia, June 4–September 6. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Margaret. 1941b. Aboriginal Art of Australia. In Art of Australia 1788–1941/An Exhibition of Australian Art Held in the United States of America and the Dominion of Canada, Carnegie Corp. by the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Edited by Ure Smith. Sydney: Ure Smith, pp. 16–7. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Margaret. 1963a. National Art Gallery of New South Wales, Domain. Sydney. Carnegie Corporation of New York Educational Service. Five Lectures by Margaret Preston. 1st. The Importance of Understanding Art with Some Early Murals to Those of 1938. MS 1963.1 Preston, Folder One, Research Files. Sydney: AGNSW. [Google Scholar]

- Preston, Margaret. 1963b. National Art Gallery of New South Wales, Domain. Sydney. Carnegie Corporation of New York Educational Service. Five Lectures by Margaret Preston. 2nd. Australia, Aboriginal Paintings—Arnhem Land. MS 1963.1 Preston, Folder One, Research Files. Sydney: AGNSW. [Google Scholar]

- Radic, Leonard. 1974. Aboriginal art is in world class—Expert. Age, October 5, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Reserve Bank of Australia. 2019. re-Decimal Inflation Calculator, Reserve Bank of Australia Website. Available online: https://www.rba.gov.au/calculator/annualPreDecimal.html (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Richardson, John L. 1999. A History of Australian Travel and Tourism. Melbourne: Hospitality Press, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, William. 2003. Modernist Primitivism: An introduction. In Anthropology of Art: A Reader. Edited by Howard Morphy and Morgan Perkins. Malden: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 129–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhe, Edward Lehman. 1966. Bark Paintings from Arnhem Land. In Bark Paintings from Arnhem Land. Kansas: Museum of Art, University of Kansas, pp. 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Louise. 2007. Forging Diplomacy: A Socio-Cultural Investigation of the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Art of Australia 1788–1941 Exhibition. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Sear, Lynne, and Julie Ewington. 1998. Brought to Light: Australian Art 1850–1965. Brisbane: Queensland Art Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Sellheim, Gert. 1930. Australia—Sunshine and Surf/Sellheim. Trove. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2007676059/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Setzler, Frank. 1939. The Archaeology of Whitewater Valley. Indianapolis: Historic Bureau of the Indiana Library and Historical Department. [Google Scholar]

- Sizer, Theodore. 1941. TS to FHT, 16 April 1941. Australian Art Exhibition 1939–1951. CCNY Archives, quoted in Jordan, Caroline. 2013. Cultural exchange in the midst of chaos Theodore Sizer’s exhibition, Art of Australia 1788–1941. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 13: 24–49. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Terry. 2001. The Visual Arts: Imploding Infrastructure, Shifting Frames, Uncertain Futures. In Culture in Australia. Policies, Publics, Programs. Edited by Tony Bennett and David Carter. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Baldwin. 2008. Kakadu People. Australian Aboriginal Culture Series, 3; Virginia: David M. Welch. [Google Scholar]

- Stanner, William Edward Hanley. 1957. The Artists of Arnhem Land. Meanjin 16: 307–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sumner, Christina, Petersen Julie, Braye Donna, and Mosman Art Gallery. 2010. Australian Accent: The Designs of Annan Fabrics and Vande Ottery in the ‘40s and ’50s: 4 September–10 October 2010. Mosman: Mosman Art Gallery. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, Peter. 1988. Catalogue. In Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia. Edited by Peter Sutton. South Yarra: Penguin Books Australia, pp. 215–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, Peter, Philip Jones, and Steven Hemming. 1988. Survival, Regeneration, and Impact. In Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia. Edited by Peter Sutton. South Yarra: Penguin Books Australia, pp. 180–212. [Google Scholar]

- Sydney Morning Herald. 1953. Australian Atmosphere in Design of Hotel Dining Room. In The Sydney Morning Herald; July 28, p. 8. Available online: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/18387124?searchTerm=aboriginal%20design%20on%20qantas%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20%20&searchLimits= (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Taylor, Luke. 1996. Seeing the Inside. Bark Paintings in Western Arnhem Land. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Luke. 2013. Expressiveness in Western Arnhem Land bark painting. In Old Masters. Australia’s Great Bark Artists. Edited by Wally Caruana. Canberra: National Museum of Australia, pp. 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Martin. 2011. The Expedition as Time Capsule: Introducing the American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem land. In Exploring the Legacy of the Arnhem Land Expedition. Edited by Martin Thomas and Margo Neale. Canberra: ANU E Press, Available online: http://press files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p116081/pdf/ch018.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- Trompf, Percy. n.d. Australia. In Library of Congress. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2008679049/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Tuckson, Anthony John, and Art Gallery of New South Wales. 1960. Aboriginal Art: Bark Paintings, Carved Figures, Sacred and Secular Objects: An Exhibition Arranged by the State Art Galleries of Australia, 1960–1961. Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 1954. Australia: Aboriginal Paintings, Arnhem Land/Introduced by Sir Herbert Read. Greenwich: New York Graphic Society by Arrangement with UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Vickery, John. 1933. Australian-Tasmania Particulars at Travel and Shipping Agencies//John Vickery33. Library of Congress. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2016651560/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Walker, Howard. 1949. Cruise to Stone Age Arnhem Land. The National Geographic Magazine XCV1: 417–30. [Google Scholar]

- White, Leanne, and Elspeth Frew. 2011. Tourism and National Identities. Connection and Conceptualizations. In Tourism and National Identities. An International Perspective. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Rhys. n.d. Out of a Great Past, a Great Future: Qantas Empire Airways, the Big Name in Empire Aviation. Library of Congress. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/item/2009632102/ (accessed on 3 February 2019).

- Zeller, Susan Kennedy. 2002. Contemporary Aboriginal Art 1948–2000: Constructing the Canon. Ph.D. Dissertation, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | From the perspective of 1988, anthropologist, Jon Altman, notes that ‘access to Aboriginal tourism [in the Northern Territory] is limited’ (Altman 1988, p. 58). |

| 2 | The conventional use of the term ‘tourist’ dates from the Grand Tours of the seventeenth and eighteen centuries, when the English ruling classes toured Europe for new cultural experiences (Richardson 1999, p. 4). This adventurism was prefigured, in much earlier times, by such rare travelers as the Greek nation’s first historian, Herodotus, and the Venetian explorer, Marco Polo. During the years 464 to 447 BC, Herodotus visited many islands in the Greek archipelago, Susa, the capital of the Persian Empire, the shores of the Black Sea as far as the mouth of the Dnieper River, and Egypt. Marco Polo travelled from Europe to the East, and in writing of his experiences in China, penned one of the most influential travel books to have ever been published (Richardson 1999, p. 4). |

| 3 | The ANTA will be discussed later. |

| 4 | George Angus (1847) writes, ‘On grand occasions--such as at a fight, or during a corrobbory or dance--the men adorn themselves with the feathers of the emu, the pelican, and the cockatoo, and ornament their bodies with stripes and spots of red and white ochre. Bunches of the leaves of the gum-tree also enter into the decorations of their persons…’. |

| 5 | The missions also had missionary church outlets in the capital cities on the eastern seaboard (Geissler 2017, pp. 55–57). |

| 6 | In 1972, the Australia National Travel Association’s commissioned report on the industry stated that ANTA believed that the travel industry warranted recognition from the Federal and State Governments as a significant force…[in the Australian economy]…and deserved similar treatment as the other established industries …’ (Peat Marwick Mitchell and Co. 1972). |

| 7 | Australia’s formative tourism organisation was called the National Tourist Organisation (NTO). This was part of a world-wide nationalism, promoted in settler societies, like the American Southwest and New Zealand, where it was established during 1901 (Barnes 2010, p. 119). |

| 8 | The title, ‘Walkabout,’ was selected for the magazines as characterizing the Australian Aboriginal, who is always on the move. It was based on the United States’ National Geographic Magazine and Life magazines. |

| 9 | Two other outback tourism reports were conducted by HKF and though none of the three were implemented, they created a benchmark for strategies for enhancing Australia’s tourism potential. |

| 10 | This was the same year as the passing of the constitutional referendum, which led to a more theoretically equal status for Indigenous Australians, as they were finally recognized as citizens of Australia. |

| 11 | However, the coalition and Labor governments showed little enthusiasm for the strategy, leaving it instead largely to the private sector. |

| 12 | Caroline Jordan. “Cultural Exchange in the Midst of Chaos: Theodore Sizer’s Exhibition ‘Art of Australia 1788–1941’.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art 13: 25–35. |

| 13 | Behind these moves for change was a wartime propaganda unit, which was headed by the media baron, Rupert Murdoch, the Director-General of Information, which had an ‘American Division,’ and Richard Casey, the first Australian minister to the US, whose role was to ‘cement the interests between both countries on the basis of mutual interest, common political ideals, and similar ways of life’. He was of great support to the Australian exhibition. Jordan, 28–34. |

| 14 | The Spencer barks were selected for Australian Aboriginal Art 1929; NGV, Art of Australia 1788–1941; 1941, David Jones Gallery, Canada, USA; Primitive Art 1943, NGV; Aboriginal Bark Paintings (1965–1966), Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Texas. Catalogues with images of the artworks were printed for the exhibitions. |

| 15 | Rubin notes that this is only simple in the sense of its reductiveness, and not—as was popularly believed—in the sense of simple mindedness. He says it was the conviction of these pioneer artists, in promoting tribal art, that it achieved the status of art. Primitive art was also linked to a sense of an idealised Tahitian and Polynesian island lifestyle. |

| 16 | For promoting lifestyle activities, such as fishing (c.f. Vickery 1933), going to the beach (c.f. Trompf n.d.; Sellheim 1930), unique fauna such as Kangaroos (c.f. Great Britain n.d.), Koalas (native bear) (c.f. Northfield 1930a), and tropical fish (c.f. Lambert 1930s), of great importance were cities like Melbourne (c.f. Northfield 1930b), and Canberra (c.f. Curtis 1940). |

| 17 | For airline travel (c.f. Williams n.d.), and for liners, cars, and airplanes (c.f. Jardine 1963). This lifestyle focus of the Qantas airlines advertisements was supported in the Donald Horne Papers for his advertising agency, Jackson Wain, who undertook all the global marketing for Qantas, in the 1960s. No mention was made of promoting Aboriginal culture or art. Refer to (Mitchell Library Manuscripts n.d.). |

| 18 | In 1939, also in New York, artist, Douglas Annand, designed murals for the Australian Pavilion of the New York Fair, in 1939, and a mural for the liner, Orcades. The latter featured a modern interpretation of an X-ray kangaroo bark painting (Black 1964, p. 126). The artist, Bryan Mansell’s, Aboriginal-inspired paintings decorated the walls of luxury liners (Black 1964, pp. 131, 134, 137). Gert Selheim created Aboriginal-inspired designs for the Qantas Empire Airways and the Australian Post (Black 1964, pp. 138, 140). |

| 19 | Refer to Geissler 2017 for a discussion of the US–Australia politics, behind the staging of the exhibition and the negative reactions to the Aboriginal art of the exhibition, pp. 97–99. |

| 20 | The David Jones exhibition consisted of displays of Aboriginal art and objects that illustrated their use by non-indigenous artists of Aboriginal art, in commercial and artistic applications. These participants included artists, Arthur Murch, Fred Leist, Margaret Preston, B. E. Minns, Nelson Illingworth, R. G. Reid, and James White. |

| 21 | Mountford was appointed by Arthur Caldwell, then Federal Minister for Information, to his department. Caldwell saw the potential of Mountford’s films, Tjuringa (1942) and Walkabout (1942), for the international publicity of Australia (May 2009, p. 174), which Mountford subsequently screened in his lecture tours in the US. |

| 22 | Mountford was approached by members of the National Geographic Society to submit a proposal for a scientific expedition (Mountford 1956, p. ix), quoted in M. Thomas 2011, p. 171. The official 1945 research proposal, submitted by Mountford to the National Geographic Society in the US, included the study of four main areas—“(a) the art of the bark paintings; (b) the art of the body paintings; (c) the general ethnology of the people; and (d) music in secular and ceremonial life” (Mountford 1945). The expedition went to Groote Eylandt in the Gulf of Carpentaria, then to Yirrkala on the Gove Peninsula, and finally to Oenpelli in Western Arnhem Land (May 2009, p. 177). |

| 23 | May points out that the agendas of international politics and propaganda were just as important as science, for the Expedition (May 2009, p. 175). |

| 24 | Both Elkin and the Berndts disputed the suggestion that little work had been done in this region (Gray 1998, pp. 191–94). Mountford’s response to this political wrangling and intrigue was “all I want to do is to create a better understanding of the aboriginal people’ (Mountford 1945), quoted in (Chapman and Russell 2011, p. 256). |

| 25 | The collections were distributed between Australian institutions and the Smithsonian Institute (Thomas 2011, p. 20; Neale 2009, p. 431; Morphy 2001, p. 54). |

| 26 | |

| 27 | A churinga is a potent ritual object used in a sacred male ritual. It is made of wood or stone and is considered to be a representation or manifestation of a mythical being. It is often elliptical in shape and is incised with sacred designs. |

| 28 | Letter by James Sweeney of 31 August to Chairman of the Board of Trustees Museum of Victoria. Attached in email correspondence received 10 January 2019 containing scanned letters from James Sweeney and Alan McCulloch sent by Stratton Kendric Meyer, Archives Assistant, Museum of Fine Arts Houston. |

| 29 | Letter by James Sweeney of 17 October to Alan McCulloch. Email correspondence received 10 January 2019 containing scanned letters from James Sweeney and Alan McCulloch sent by Stratton Kendric Meyer, Archives Assistant, Museum of Fine Arts Houston. |

| 30 | Letter of 31 January 1966 of James Sweeney to Alan McCulloch. Email correspondence received 10 January 2019 containing scanned letters from James Sweeney and Alan McCulloch sent by Stratton Kendric Meyer, Archives Assistant, Museum of Fine Arts Houston. |

| 31 | James discusses the complex politics of gaining the Museum Trustees’ support for the exhibition to go ahead. It involved significant lobbying of the Victorian Government authorities. |

| 32 | McCulloch gives added distinction to the Houston catalogue text by noting that the Karel Kupka had assisted with his review and advice. At the time of the exhibition, the Museum had purchased ten bark paintings from Australia, refer to (Museum of Fine Arts 1960). |

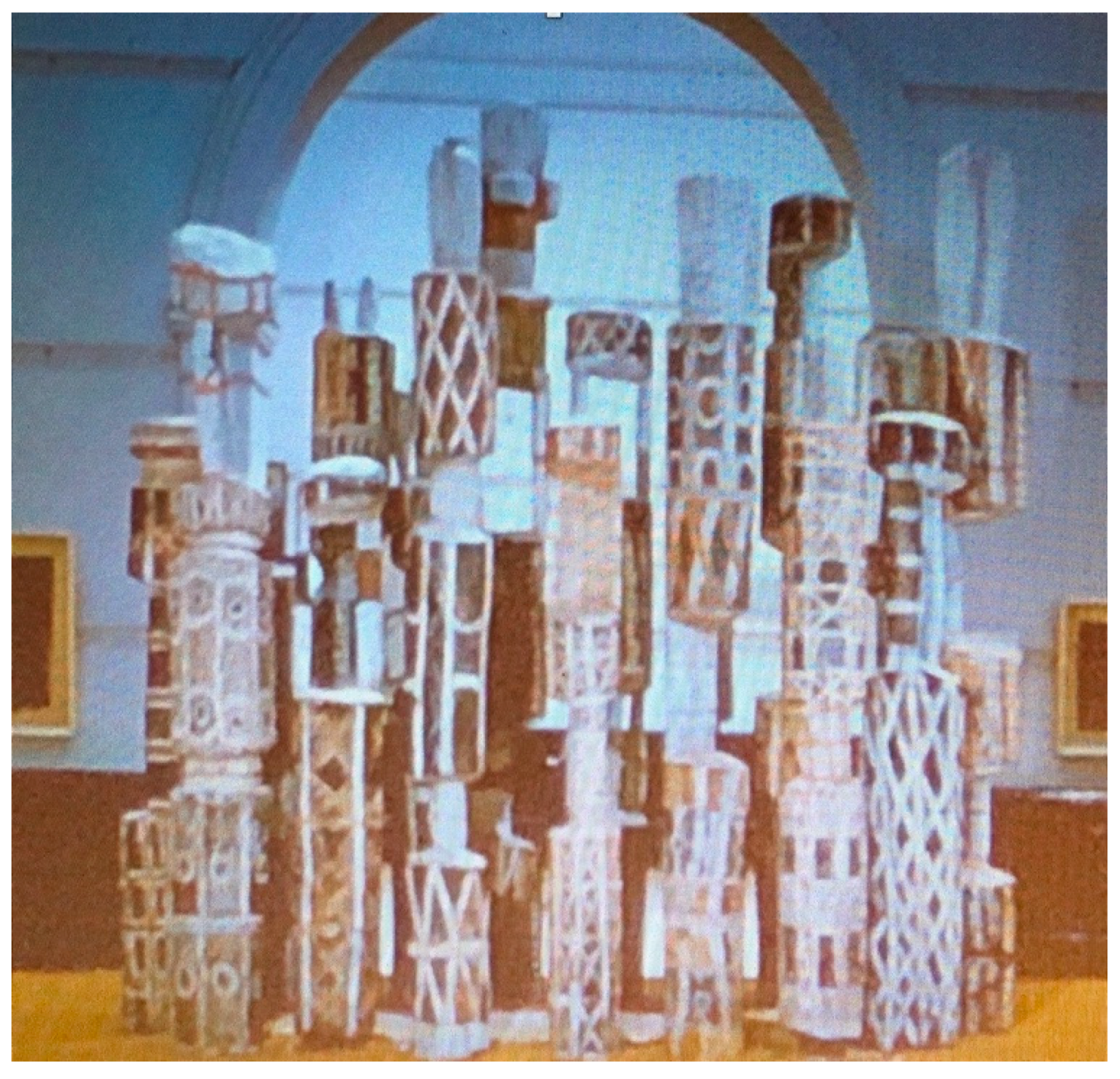

| 33 | The original bark paintings from the Scougall collection at the AGNSW were initially exhibited in 1960 at the AGNSW with his monumental Pukumani grave post collection by Tiwi artists from Melville Island. They were were finely detailed with the traditional encoded imagery used by bark painters (Figure 3). |

| 34 | For discussion of recommendations for ‘self-determination’ of Aborigines of Northern Australia involved in the art business, refer the Ulli Beier Report of 1969 for the Australian Federal Government (Geissler 2017, pp. 161–62). In 1979, the Australian Tourist Commission was circumspect about promoting anything that might appear exploitative of or reflect adversely on the dignity of indigenous peoples. By 1997, however, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) and the National Office for Tourism had published a tourism strategy for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders which was designed to increase that involvement. This acknowledged the role that Indigenous tourism could play in the overall industry, while at the same time fostering economic independence and cultural preservation for the people concerned. The strategy aimed to promote the ‘considerable diversity of regional cultures’ through marketing and educational initiatives. Of the cultural tours conducted by Aborigines, seventy percent came from overseas, including the USA (Richardson 1999, pp. 163–40). |

| 35 | This was the first most comprehensive international showing of Australian Aboriginal art. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Geissler, M. Cultural Tourism: Imagery of Arnhem Land Bark Paintings Informs Australian Messaging to the Post-War USA. Arts 2019, 8, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020066

Geissler M. Cultural Tourism: Imagery of Arnhem Land Bark Paintings Informs Australian Messaging to the Post-War USA. Arts. 2019; 8(2):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020066

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeissler, Marie. 2019. "Cultural Tourism: Imagery of Arnhem Land Bark Paintings Informs Australian Messaging to the Post-War USA" Arts 8, no. 2: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020066

APA StyleGeissler, M. (2019). Cultural Tourism: Imagery of Arnhem Land Bark Paintings Informs Australian Messaging to the Post-War USA. Arts, 8(2), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020066