Abstract

Indigenous cultural tourism offers significant future opportunities for countries, cities and Indigenous communities, but the development of new offerings can be problematic. Addressing this challenge, this article examines contemporary Australian Indigenous art innovation and cultural entrepreneurship or culturepreneurship emanating from Australia’s remote Arnhem Land art and culture centres and provides insight into the future development of Indigenous cultural tourism. Using art- and culture-focused field studies and recent literature from the diverse disciplines of art history, tourism, sociology and economics, this article investigates examples of successful Indigenous artistic innovation and culturepreneurship that operate within the context of cultural tourism events. From this investigation, this article introduces and defines the original concept of Indigenous culturepreneurship and provides six practical criteria for those interested in developing future Indigenous cultural tourism ventures. These findings not only challenge existing western definitions of both culture and culturepreneurship but also affirm the vital role of innovation in both contemporary Indigenous art and culturepreneurial practice. Equally importantly, this investigation illuminates Indigenous culturepreneurship as an important future-making socio-political and economic practice for the potential benefit of Indigenous communities concerned with maintaining and promoting their cultures as living, growing and relevant in the contemporary world.

1. Introduction

Artistic innovation of Indigenous cultural knowledge has been a mainstay of Australian cultural tourist attractions over many decades, evidenced by the diversity and volume of new Australian Indigenous art emanating from one of the world’s oldest known continuous cultures (Wright 2017).1 Concurrently, art and cultural tourism as well as Indigenous tourism have become major trends in domestic and international visitor experiences (Smith 2009a, pp. 15–36; Simone-Charteris and Boyd 2013, p. 220).

Indigenous cultural tourism offers significant opportunities for countries and cities, especially for those Indigenous communities whose options are limited due to remote locations, inexperience and limited resources. In the face of these challenges, how can suitable cultural tourism offerings be successfully developed? To address this problem, this article presents the original concept of Indigenous culturepreneurship, a developmental socio-cultural and economic practice that not only embraces cultural preservation but also fosters cultural renewal and advancement or future-making.

To fully explain Indigenous culturepreneurship, a cross-disciplinary method is employed. This examines recent literature from art history, tourism, sociology and economics, and is further informed by the author’s field-trips, including ethically-cleared qualitative interviews with Indigenous-art-sector participants. Two case-studies of successful Australian Indigenous culturepreneurship are investigated. These examples both function within the context of significant art- and culture-focused tourist events and highlight fine art produced by artists from art and culture centres in Australia’s remote Arnhem Land region. The success-criteria of Indigenous culturepreneurship have been developed by the author based upon this examination of art and culture centres. These criteria are premised on the remarkable artistic innovation demonstrated by Australia’s Indigenous artists, but also emphasise the central importance of innovation in all aspects of Indigenous culturepreneurship.

This article introduces and defines Indigenous culturepreneurship as it relates to art practice and reveals important criteria that may assist the development of future Indigenous art and cultural tourism experiences. It also identifies key features of Arnhem Land’s innovative Indigenous history and culture that have contributed to culturepreneurship. Further, it challenges the Western character of both culture and culturepreneurship and negates a persistent stereotype applied to Indigenous art practice. This stereotype suggests that the authenticity, artistic merit and value of Indigenous art can only be assured when it is both old and thoroughly consistent with the forms of its initial production.

The context of Australia’s Indigenous art and cultural tourism is examined first, followed by examples of innovative Indigenous art practice and culturepreneurship drawn from Arnhem Land’s dynamic art and culture centres. A brief history follows, describing the significant culturepreneurial foundations of Arnhem Land’s Indigenous communities and how their art and culture centres helped establish a growing presence in fine art markets. Indigenous culturepreneurship is then described in more detail, and key success criteria are identified to assist those seeking to develop Indigenous art and tourism enterprises.

Cultural tourism, including Indigenous tourism, offers appealing opportunities for countries, cities and, especially, Indigenous communities. In particular, cultural tourism provides opportunities to promote art, culture and intercultural understanding and to preserve cultural identity, while simultaneously delivering economic benefit (Tourism Australia 2018; Ruhanen and Whitford 2017, pp. 9, 13; Whitford et al. 2017, p. 2). For those tourists interested in cultural tourism, who are often well-travelled and educated, it presents a stimulating opportunity for rich cultural encounters that previously may have been unattainable (Whitford et al. 2017, p. 1; Hales and Higgins-Desbiolles 2017, p. 126). Consequently, stimulated by enduring human characteristics, such as “curiosity, exploring the unknown, and a craving for new knowledge,” cultural tourism can be expected to accelerate, especially with 2019 declared as the Year of Indigenous Languages by the United Nations (Whitford et al. 2017, p. 1; UNESCO 2019).

In Australia, Indigenous cultural tourism has been identified as an important and differentiating tourism priority, but nevertheless remains in its early stages of development. Since early 2000, Indigenous cultural tourism has been a key part of Australia’s tourism plans and specifically promoted as one of its key experiences (Ruhanen and Whitford 2017, p. 9). However, participation has not always met expectations, especially due to limited Indigenous participation caused by factors such as inadequate capital, insufficient training and experience, problems of remote locations, and ineffective Government support (ibid., pp. 14–16). Nevertheless, the development of intangible cultural heritage is steadily increasing and includes extensive oral and visual histories, expanding performing arts and festivals, and popular arts and crafts (Whitford et al. 2017, p. 2).

By comparison, Australia’s Indigenous art sector is already an international success story that offers cultural tourism a powerful and diverse leading attraction. Drawn from one of the world’s oldest continuous cultures and originally present in ancient rock art, Australia’s contemporary Indigenous art has unparalleled cultural credentials. Moreover, its unique designs are not only aesthetically compelling but also serve as complex esoteric visual languages or ciphers (McLean 2016, pp. 100–2). For the initiated, these designs unlock a highly sophisticated faith and knowledge base with an extraordinary cultural history. Since the 1970s, Australia’s Indigenous art has more publically exhibited its inherent artistic innovation drawn from rich cultural foundations, even while using customary materials sourced from remote country landscapes. This innovative art has generated substantial domestic and international appeal, not just as tourist art but also as collectible, exhibition-standard contemporary fine art. While Australia has been widely acknowledged for dot-style Indigenous art, as well as for art by successful urban-based Indigenous artists, it has over 80 Indigenous art and culture centres distributed across its regions (Fisher 2016, pp. 8, 63). Each of these centres advance their own unique and distinctive art styles, cultural emphases and approaches to innovation, offering tourists a diverse and intriguing drawcard for their cultural experiences.

2. Examples of Artistic Innovation and Culturepreneurship in Practice

Two Australian examples highlight the value and impact of artistic innovation and culturepreneurship as part of art-focused Indigenous cultural tourism events.

2.1. Example 1. Artistic Innovation and Culturepreneurship: Bukyu, National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards and the Darwin Festival

For more than thirty years, innovative Indigenous artworks that represent cultural knowledge have been the leading attractions for the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Awards (NATSIAA)—a highly successful cultural tourism event central to the popularity of the multicultural Darwin Festival (2018) held in Australia’s remote Northern Territory. In 2018, the winning entry once again surprised judges and visitors with its artistic innovation.

Arresting in its presence, the artwork Bukyu (2018) (Figure 1) was produced by the rising Australian Indigenous artist Gunybi Ganambarr. A Yolŋu matha artist from the Ngaymil clan, Ganambarr, was born in the East Arnhem Land township of Yirrkala in 1973 (QAGOMA 2018). Yolŋu represents the largest language group within Arnhem Land (Figure 2), while Ganambarr himself is an ex-builder, ceremonial yidaki (didgeridoo) musician and energetic participant in ceremonial life who developed his art through the dynamic Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka (Buku) Art and Culture Centre in Yirrkala (Buku Larrŋggay Mulka Centre 2019). Ganambarr’s art is exhibited in major state galleries, has featured prominently in Sydney’s Annandale Galleries, and is now eagerly bought internationally (Annandale Galleries 2018). As a recent testament to Ganambarr’s capability, Bukyu was judged overall winner of the prestigious Telstra Art Award at the 35th NATSIAA in 2018 (MAGNT 2018). The Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (MAGNT) has hosted this event for the last 35 years, and Telstra, Australia’s largest telecommunication enterprise, has been its major sponsor for the last 27 years (Penn 2018, p. 3). NATSIAA functions as a key part of the annual Darwin Festival—a multi-cultural arts event that continues to grow in popularity, attracting both domestic and international tourists.

Figure 1.

Gunybi Ganambarr and Bukyu, 2018, overall winner of the 2018 Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards. Image courtesy MAGNT, photo: Fiona Morrison.

Figure 2.

Arnhem Land (shown as the darkened section, including surrounding islands), Northern Territory, Australia. Image sourced from https://northernterritory.com.

Bukyu’s imposing scale commands viewers’ attention, but its medium is unexpected, and its categorisation is challenging. At 300 cm × 300 cm, Bukyu boldly advances its presence. With its designs etched onto black powder-coated aluminium sheets discarded from a local building site, it offers a seemingly unlikely surface for an Arnhem Land artist. Yet, like other artists from the region Ganambarr constantly refines the narratives and aesthetic qualities of his art through the creative use of new techniques and diverse media, including found materials that embody a contemporary representation of his country. In Western art history terms, Bukyu’s recent production and innovation—together with its relation to a global context and “an ever-changing present”—may well categorise it as contemporary, and equally so because it “actualises the idea of art”, notwithstanding aesthetic qualities that are usually denied in contemporary artworks (Smith 2009b, pp. 3–7; Koepnick 2014, pp. 5–6; Osborne 2004, p. 653). This categorisation of Australia’s Indigenous art as contemporary has been argued for decades by art historians who have simultaneously sought to incorporate it into the wider canon of world art, distance it from the imperial perceptions of primitivism, and release it from the limiting interpretations of ethnography that pervaded twentieth-century art commentary (Morphy 2008, pp. 2, 190; Croft 2009, pp. xi–xii; Neale 2001, p. 8; McLean 2016, p. 7; McLean 2011, p. 69; Myers 2002, pp. 121, 191, 198). However, for Ganambarr and his people, this Western categorisation of contemporary, while partly liberating, still remains limiting. This is because, from a Yolŋu temporal perspective, faith is an ever-evolving “relationship between the past, present and future”, unlike the linear sequences of Western chronology that leave the past behind (McLean 2016, p. 17). Bukyu echoes this Yolŋu temporal perspective by concurrently offering complex narratives from the past, Ancestral imminence and contextual relation in the present, and rich knowledge and dreams for the potential benefit of future generations. In doing so, Bukyu confounds the western category of contemporary, leaving it to appear somewhat narrow and superficial as a descriptor of Indigenous art.

Impressions of Bukyu are influenced first by Ganambarr’s intentional relationship between flowing design and light. Notwithstanding Bukyu’s daunting proportions, Ganambarr has transformed two aluminium sheets into a refined masterwork by etching thousands of delicate incisions into its black-coated surface using a motorised hand-held engraving disk. This etching illuminates swirls of bright silver aluminium against the remnant gloss black, allowing this liberated light to animate the interconnected miny’tji designs. These, as well as other sacred crosshatched designs from West Arnhem Land known as rarrk, evolved from early foundations in rock art. The intricate construction of these flickering designs intentionally conveys the active presence of Ancestral power, provides a complex and inalienable source code for Indigenous knowledge, and explicitly transmits Indigenous identity (Morphy 1989, p. 24; Caruana 2013a, p. 12; McLean 2016, pp. 100–2; Butler 2017, p. 107; Butler 2018, p. 189). Bukyu’s monochromatic miny’tji designs produce these accentuated perceptions of variable light and movement to serve these cultural objectives, yet these designs also generate a powerful aesthetic impact for non-Indigenous viewers. Artistically, this method extends the effects produced by previous Arnhem Land art that used contrasting paint colours to generate the same light-animated result (Morphy 1989, p. 196).

Bukyu also appears to exhibit Ancestral power and a beguiling life of its own. Viewed at close quarters, Bukyu’s miny’tji designs are extraordinarily precise, demonstrating the measured hand of an assured artist. Yet, after retreating a few metres and seeing these designs in their entirety, they also reveal the surging energy of a creative spirit. Here, miny’tji creates its intended interplay of light, but supplements it with a wider organic impression of shallow water moving over a creek bed, effectively extending Bukyu’s presence into a third dimension. Curiously, this movement is sufficiently mesmerising for viewers that they move sideways to absorb its dynamic variations, only to once again involuntarily move closer. This last movement appears to be an attempt to gain a more intimate or even tactile connection with an artwork that apparently generates its own kinetic energy.2

The wider appeal of Bukyu lies in the combination of its innovative aesthetic impact and an intriguing cultural narrative: a blend that negates an outdated but persistent Western stereotype. Ganambarr’s miny’tji designs, due to their religious and ceremonial significance, are fiercely protected (Sutton 1989, p. 59). Together with the sacred and secret narratives they contain and the form in which they are presented, miny’tji can only be produced by initiated clan artists with agreement from their elders (Berndt et al. 1982, pp. 14). Accordingly, Ganambarr and other Arnhem Land artists must maintain these important design obligations, as well as the sanctity of extensive ancestral narratives. Yet, despite the constraints of these obligations, Arnhem Land artists create highly innovative new ways to present their art. Further, they openly communicate renewed narratives drawn from the warrangul—the non-secret “outside” element of their complex knowledge structure—for the benefit of non-Yolŋu people (Morphy 1991, pp. 77–78). In doing so, these Indigenous artists overturn an outdated Western stereotype that suggests that the authenticity, artistic merit and value of Indigenous art can only be assured when it is both old and thoroughly consistent with the forms of its initial production.

The aesthetic power and apparent kinetic energy of Bukyu also intensifies curiosity regarding the Indigenous narratives that inspire it. NATSIAA judges explain that the central narrative of Bukyu “honours Ganambarr’s forebears” and “speaks to the coming together of the Dhalwangu clan for fish trap ceremonies and how these ceremonies unite Yolŋu” (MAGNT 2018). Bukyu can, therefore, be read as a multi-layered narrative engaging Ancestral and familial themes as well as their historical practices. These themes are visually represented through the use of miny’tji designs which not only suggest these narratives but simultaneously evoke the changing patterns of Arnhem Land’s shallow waters, generating further intrigue for non-Yolŋu viewers. For the Yolŋu themselves though, these designs are not simply aesthetic and evocative, they also offer an existential Ancestral presence and a highly sophisticated visual cipher that stretches across temporal boundaries to identify sacred links with their land, law, knowledge, ceremony and cultural practice.

2.2. Example 2. Artistic Innovation and Culturepreneurship: Ngalyod the Rainbow Serpent and the MCAA International Art Exhibition in Sydney

From July to September 2018, Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art of Australia (MCAA) presented a landmark art exhibition by John Mawurndjul AO, whose artistic innovation of Indigenous cultural knowledge had previously helped him to become a successful and internationally recognised artist. The MCAA is located near Sydney’s Opera House and Harbour Bridge, adjacent to the city’s most prestigious cruise ship terminal. Here, in Australia’s prime tourist hub, the MCAA launched John Mawurndjul: I am the Old and the New concurrently with an exhibition by the equally innovative Chinese artist Sun Xun. The title selected for the Mawurndjul exhibition reflects a previous quote by the artist himself expressing his commitment to both culture and innovation, and the MCAA exhibition overtly adopted these concepts as their curatorial themes (Taylor 2005b, p. 43).

Marwundjul, born in Arnhem Land in 1952, is a Kuninjku (west Arnhem Land language group) artist and “chemist man” or spiritual leader (Mawurndjul 2004, pp. 135–38). Now one of Australia’s most famous Indigenous artists, Mawurndjul is a multiple winner of the NATSIAA Bark Painting Award, and in 2003 he also won Australia’s prestigious Clemenger Contemporary Art Award (O’Callaghan 2018, pp. 352–70). Since 1986, his work has been exhibited internationally in pathbreaking events in Japan, India, Germany, England, Denmark and Switzerland (ibid.). In 2006, Mawurndjul was also commissioned as one of eight Australian Indigenous artists featured at the Musée de quai Branly in Paris; later, as a result, he unexpectedly found himself portrayed on the cover of Time magazine (ibid.). In 2010, he was awarded an Order of Australia for “service to the preservation of Indigenous culture,” and in 2018, he was presented the Red Ochre Award by the Australian Council for the Arts for outstanding lifetime achievement (ibid.). Mawurndjul primarily practices his art through Arnhem Land’s Maningrida Art and Culture Centre which operates under the auspices of the Bawinanga Aboriginal Corporation—a commercial entity that oversees that centre, as well as other cultural, community and employment enterprises (Bawananga Aboriginal Corporation 2018)3.

The inspiration for Mawurndjul’s art is the grand embrace of his kunred, place or country, a central component of Australian Indigenous faith (Bullen et al. 2018, p. 374). Western descriptions of this faith commonly describe it as the Dreaming, although this term significantly over-simplifies its meaning and understates its scope. For many Indigenous Australians, faith is not simply an archaic theology, but provides a palpable way to “interact with the past, present and future” (Gilchrist 2016, p. 18). It is at once an archive of Ancestral narratives, sacred sites and objects, ethics and laws, where “the earth, sea and sky function as libraries of knowledge” (ibid.). Consequently, sacred sites may be vested with extraordinary influence, making them locations of powerful spiritual communion (ibid.). Australian Indigenous faith, therefore, serves to preserve the past, speaks of eternal becoming, pushes Ancestral memory into the present and makes the past directly accessible as a cyclical and circular order (ibid.). In summary, it may be described as a sequence of “mythopoetic sagas”, an epic history of the world, the nature of being and the rules of living (McLean 2016, p. 17).

As the touchstone and inspiration for their art, this faith of Arnhem Land’s Indigenous Australians is neither static nor lacking in qualities of renewal and contemporaneity, thereby continuing to effectively serve as the foundation for one of the world’s longest continuous cultures (ibid.). Australian Indigenous sagas or narratives when retold act partly as a restorative process, reinvigorating both the content and importance of Ancestral lore (Voyageur et al. 2015, p. 4). Notably, this retelling may extend to a form of restorying, whereby narratives include not just new experiences but also incorporate matters of healing with concepts drawn from multiple concurrent temporalities, Indigenous leadership and spiritual renewal (Voyageur et al. 2015, p. 4). Retelling and restorying therefore serve to rejuvenate Indigenous narratives by adding an unexpected contemporaneity to their Ancestral base, but they are equally useful for communicating important lessons about the natural and spiritual worlds to Balanda and other external groups. Balanda, an Aboriginal word still employed by Indigenous Australians to denote non-Indigenous white people, was coined from the term Hollander, initially used to describe pre-colonial Dutch explorers in Australia (McMillan 2001, p. 29).

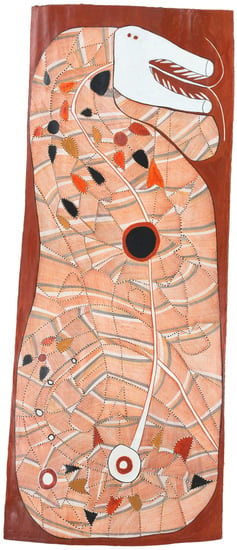

Mawurndjul represents this faith and culture through his art in both tangible and conceptual forms. Ngalyod (2012) (Figure 3) was presented by the MCAA as the lead attraction for the exhibition, no doubt partly reflecting an awareness that monsters are universally fascinating crowd favourites. Shown here as a fearsome white-faced creature with two rows of file-point teeth, Ngalyod represents a monster-like rainbow serpent (Perkins 2018, p. 25). Its seductive supernaturally-inspired imagery highlights cultural creation themes drawn from the Djang or sacred sites from Mawurndjul’s Kuninjku Arnhem Land country (Garde 2018, pp. 60–61). Most tangibly though, Mawurndjul’s commitment to his faith and clan obligations are represented by his choice of materials. For Ngalyod and his other bark paintings, flattened Eucalyptus tetradonta or Stringybark provides his textured painting surface, while rich-toned ochres provide his paint—all sourced from his sacred land (Bullen et al. 2018, p. 374). As described by the MCAA, Mawurndjul’s less tangible but equally powerful concepts of Kuninjku culture, such as the “natural circular rhythm, the growing and gathering of knowledge and the rituals of lifecycles”, permeate all aspects of this [MCAA] exhibition (ibid.).

Figure 3.

John Mawurndjul, Ngalyod 2012, Museum of Contemporary Art, purchased with funds provided by the MCA Foundation, 2015 © John Mawurndjul/Copyright Agency, 2018, photograph Jessica Maurer.

Examining Mawurndjul’s series of Ngalyod paintings over time offers insight into his artistic innovation. Ngalyod has been a recurring subject for Mawurndjul since the early 1980s, and its ongoing depictions include regular extensions of narrative, as well as the introduction of complementary figurative subjects and non-figurative forms, frequently but inadequately defined in Western art terms as abstract (Perkins 2018, p. 25). During this period, he has constantly refined his painted crosshatched rarrk designs, further exploiting the capacity of kabimbebme—Kuninjku for the effect of brilliance or “paint jumping out at you” (ibid., pp. 25, 33; Taylor 2015a, p. 73). This greater brilliance is partly a testament to Mawurndjul’s matured precision and expertise but has also been supported by painting over a brighter white background, offering a more radiant ‘backlit’ effect (Perkins 2018, p. 33). Linking the complementary themes of culture and innovation, Mawurndjul’s art has also “expanded in size and complexity as his ceremonial experience, confidence and authority grew” (ibid., p. 25). Accordingly, when compared to earlier versions, later depictions of Ngalyod—such as the example depicted here—are brighter, significantly larger, offer more complex narratives and demonstrate more resolved geometric and curvilinear forms.

The MCAA, in collaboration with Mawurndjul and his art and cultural centre, further evidenced the culturepreneurial qualities of Mawurndjul’s exhibition by placing Kuninjku language and culture “at the forefront of the visitor experience” (Macgregor et al. 2018, p. 19). This cultural emphasis is immediately apparent in the exhibition’s overall bilingual (English and Kuninjku) approach and is affirmed by the prime placement of a bilingual televised interview with Mawurndjul situated at the entry to the exhibition. Detailed Kuninjku maps and photographs also feature at the start of the exhibition. Similarly, culture is central to the structure and content of the exhibition catalogue and is further amplified by a linked website.4 This website connects Mawurndjul’s paintings directly with the narratives and locations of his sacred country and is further supported by Kuninjku language sound-bites. By adopting this culture-first posture, the MCAA exhibition challenges its visitors to reach beyond Mawurndjul’s art to grasp its extensive cultural context. Moreover, like Ganambarr’s contribution at NATSIAA, it expands intercultural dialogue, enriches the curatorial approach and demonstrates effective Indigenous culturepreneurship.

3. Arnhem Land’s History of Innovation and Culturepreneurship

Innovation is a central feature of culturepreneurship, and as a sophisticated skill necessarily supported by knowledge and memory, it is embedded in Arnhem Land’s extended Indigenous history and culture. In contrast to colonial views of stagnant development, Arnhem Land’s people demonstrated significant adaptation and innovation. This was first demonstrated by their ability over more than 60,000 years to continuously accommodate a challenging environment and manage the full force of climate change, not least the profound impacts of an ice age during this period (Fitzsimmons et al. 2015; Wright 2017). In this setting, an economic system based on sharing and mutually beneficial trade was employed, resulting in a minimal material culture and technologies described as, “simple, ingenious and multifunctional” (Sutton and Anderson 1989, p. 7). Further, creativity and innovation are now understood to be effectively facilitated by long habitation of traditional lands, allowing Indigenous populations, such as Australia’s Arnhem Land people, to accumulate highly dynamic knowledge systems (Huaman 2015, pp. 1, 4, 5). These systems comprise complex visual and oral languages, oblige extensive periods of initiation and learning and must be served by prodigious memories (Kelly 2017, pp. 1–3). Accordingly, Australia’s Indigenous people have employed creative means to recall and reinforce elements of this knowledge, including intricately coded art designs, storytelling, ceremonial dance and songlines. Songlines are extended songs informed by Indigenous faith, sometimes comprising hundreds of verses, that describe detailed navigational routes through challenging landscapes (ibid., pp. 13–16).

Collaboration—another essential element of culturepreneurship—is also entrenched in Arnhem Land Indigenous culture and practice. For Arnhem Land’s and other Indigenous people in Australia, regular travel beyond their own lands was obliged by climatic and seasonal change, arguably establishing them as the original cultural tourists (Sutton and Anderson 1989, pp. 6–7). During these periods of travel, polylingualism and effective interaction were essential because at least two hundred language groups were present in Australia prior to colonisation, many operating under diverse ecological conditions (Huaman 2015, pp. 1, 4, 5). The complex moiety system, still operating today within Arnhem Land’s Indigenous population, provides a fundamental basis for effective collaboration and sharing between individuals and groups. Derived from the French term, moitié (half), Indigenous moieties divide human society and all elements of the universe into two halves, providing a defined basis for the custody of land, ceremonies and sacred designs and obliging intermarriage between clan groups (Morphy 1991, pp. 57–74; Caruana 2013b, p. 12). As a result, moieties establish familial-style relationships across and beyond clans, resulting in an overt cultural predisposition for collaboration, sharing and inclusiveness.5 As Howard Morphy also explains, Arnhem Land’s people readily incorporate outsiders into their society, “allocating them a place in their kinship universe” (Morphy 2008, p. 61).

Arnhem Land’s Indigenous people utilised these capacities of innovation, sharing and collaboration to develop long-term intercultural trading partnerships with Macassan seafarers that operated successfully for centuries prior to Australia’s colonisation (Clark 2013, p. 162; Blair and Hall 2013, pp. 210–12; McCulloch 2001, pp. 145–46). Known in Australian scholarship as Macassans, these experienced traders principally emanated from the South Sulawesi city of Makassar—now Indonesia’s third largest port (Clark 2013, p. 162; Blair and Hall 2013, p. 210). Sailing southeast from as early as 1622, the Macassans found Arnhem Land’s people, particularly the Yolŋu, to be agreeable and profitable partners (Wesley et al. 2016, pp. 173, 191). The Macassans brought important trade links with Vietnam, Thailand and China and worked with Arnhem Land’s people for several months each year harvesting and processing trepang. Trepang—a marine invertebrate—is prized in Asia for its culinary and medicinal qualities (Clark 2013, p. 28; Clark and May 2013, pp. 1–18). Additionally, turtle shell, pearls and pearl shell were traded in volume by Arnhem Land communities in return for the technology to produce dugout canoes and products, such as metal axes, knives, fish hooks, pottery, glass and rice (McMillan 2001, p. 29; Bilous 2015, p. 906). The scale and frequency of this enterprise, observed in 1803, caused the early Australian colonial maritime explorer Matthew Flinders to name this busy sea route between Arnhem Land and Makassar “the Malay Road” (Blair and Hall 2013, pp. 206–7).

This extended period of trade with the Macassans refined a further valuable culturepreneurial attribute for Arnhem Land’s people: productive intercultural exchange, a capacity strongly demonstrated by the adoption of many aspects of their language and culture. Trade with the Macassans continued successfully until 1907 when new Government regulations terminated the industry (Adhuri 2013, p. 185). However, prior to this time, trade was generally conducted within Arnhem Land’s normative traditions, and members of the population lived, worked, married and died in Makassar, sometimes adding Malay to their polylingual repertoire (Thomas 2013, p. 70; Wesley and Litster 2015, pp. 1–3; Clark 2013, pp. 163–67). In daily practice, Arnhem Land people adopted the use of calico products and metal implements, smoked tobacco, embraced colourful flags for ceremonies and incorporated hundreds of Macassan words into local languages, including rrupiya for money (McMillan 2001; Caruana 2013b, p. 160).

More recently, the essential culturepreneurial characteristic of resilience in the face of risk is demonstrated by Arnhem Land’s people through their progressive emergence from the brutal pressures of colonisation. Since Australia’s colonisation, Arnhem Land’s people contended with repeated and ultimately successful attempts to establish permanent colonial settlements, while also absorbing major incursions by miners, pastoralists and missionaries (McMillan 2001, pp. 35–37, 47–69, 88–121). Predictably, the miners and pastoralists sought to conquer their land for its material benefits, often damaging the region’s ecology in the process (ibid.). On the other hand, missionaries provided some health and western education benefits, but their aims were still often aligned with Government assimilation policies that aimed to “take the Aboriginality out of Aboriginal people” (ibid., p. 265; Dewar 1992, p. 23; McLean 2016, p. 118). Nevertheless, unlike many other Australian Indigenous regions, the preservation of Arnhem Land’s culture was aided first by its remoteness from early colonial settlements and later by its declaration as an Aboriginal reserve in 1931—a measure partly motivated by Government desires to insulate the then emerging town of Darwin from Aboriginal influences (Fisher 2016, pp. 122–23). Despite such motives, this declaration nevertheless proved to be significant for the preservation of both their culture and their resilience.

During the second half of the twentieth century, Arnhem Land’s communities began to overtly demonstrate their culturepreneurial qualities to non-Indigenous Australians by melding art, culture and political advocacy into an increasingly powerful package that became especially evident in two politico-historical moments. Public exhibitions of Australian Aboriginal art emerged in the early 1960s, led by the popular touring exhibition of Tony Tuckson from the Art Gallery of New South Wales (Fisher 2016, pp. 122–123). This followed earlier anthropological investigations by researchers, such as Baldwin Spencer, Roland M. Berndt, Charles Mountford and Sandra Le Brun Holmes, who had already identified the unique qualities of Arnhem Land art (The Aboriginal Arts Board 1979, pp. 10–11; McLean 2016, pp. 102–3; Thomas 2011, p. 16; Le Brun Holmes 1972). However, the first historical moment that collectively brought their art, culture and political advocacy to wider public notice involved land rights petitions representing the political interests of Arnhem Land’s Yirritja and Dhuwa moieties (McMillan 2001, p. 278). These petitions, initially presented to the Australian parliament in August 1963, asserted their entitlements to both self-determination and the land they had occupied for millennia (ibid., p. 279). The petitions themselves were pasted onto two sheets of Stringybark—the host tree for most Arnhem Land bark paintings—and bordered with sacred designs representing their country and some of their totemic creatures under threat (Ryan 2005, p. 177; McMillan 2001). Today, this event is celebrated for accelerating the movement that ultimately resulted in the 1976 Aboriginal Land Rights Act allowing Aboriginal people to mount a claim for Crown Land (Fisher 2016, p. 32). The second historical moment is represented by the poignant 1988 Aboriginal Memorial. This symbolic artwork, originally produced for the Sydney Biennale as part of Australia’s 1988 Bicentennial celebration of colonial settlement, was produced by forty-three Arnhem Land artists, one of whom being John Mawurndjul (ibid., p. 36; O’Callaghan 2018, p. 354). The artwork features two hundred painted log coffins publicly marking the bicentennial of painful colonisation and Aboriginal dispossession—a highly evocative statement that now serves as a melancholy monument in the entry foyer of the National Gallery of Australia.

4. Australian Indigenous Art and Culture Centres and Their Culturepreneurial Networks

For over fifty years, Australian Indigenous art and culture centres, supported by their culturepreneurial networks, have been the most important contributor to the national and international success of Australia’s Indigenous art.

4.1. Australian Indigenous Art and Culture Centres

Australia’s successful contemporary Indigenous art movement owes its genesis and much of its subsequent development to the inception of art and culture centres, which deliver extensive ongoing benefits. Felicity Wright describes them as “unique, exhilarating, challenging, confounding and frequently wonderful organisations”, where the principal activity is “facilitating the production and marketing of arts and crafts” (Wright 2000, p. xvii). Just as importantly, Wright identifies that art and culture centres deliver important sociocultural services from a role that is jointly cultural and economic (ibid.). Similarly, referring to a 2006 Australian Senate report, Gretchen Stolte argues that these centres “facilitate the maintenance of Indigenous culture within the community, as well as facilitating the transmission of that culture to the world beyond the community” (Stolte 2012, pp. 232–37).

More practically, these centres provide an indispensable facility for the support of artists and for the production, storage, evaluation and distribution of their art. Being located in small townships, they are points of accessible representation for artists, many of whom live in even more remote homelands or outstations—small settlements on Ancestral lands often located at a considerable distance from these centres (McLean 2016, p. 118). Art and culture centres offer a convenient point of access not just for artists, but also for other community members, curators, dealers, writers, retail buyers and tourists, providing the facilities and critical expertise needed to administer and authenticate local art.

In brief, Australia’s Indigenous art and culture centres provide significant economic and socio-cultural benefit for their communities through the design, production and sale of art, as well as other related products and cultural services. They achieve this by operating as an essential and efficient locus for cultural, social, financial and other forms of capital and by providing the facilities, services, materials, critical mass, access and credibility essential for the operation of such enterprises.

Indigenous art and culture centres have been operating in Australia as early as 1948 when the Ernabella Arts centre was established in South Australia by its then Presbyterian mission, followed later by the more celebrated Western Desert’s Papunya Tula Artists centre in 1971/72 (Ernabella Arts 2019; Fisher 2016, pp. 6–7). Papunya Tula’s commencement also beneficially coincided with the 1972 election of the progressive Labor Government of Gough Whitlam, whose policies supported both the arts and Indigenous rights (Fisher 2016, pp. 6–7). Subsequently, during the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, art and cultural centres were established with Government support in urban areas as well as other remote regions, such as Western Australia’s Kimberley, Northern Queensland, and the Torres Strait and Arnhem Land regions, all of which demonstrate their own distinctive art styles (ibid., p. 7).

Government support for these centres was initially provided through financial subsidy and was also temporarily supplemented by a suite of Government trading outlets established to alleviate the barrier of remoteness and facilitate the urban exhibition and sale of Indigenous art (ibid.). During the 1970s, new Government policy and financial assistance also supported the return of Indigenous people to their traditional homelands, allowing Arnhem Land artists, such as John Mawurndjul, to produce his art in a more conducive cultural environment (Altman 2005b, p. 32). Government assistance for art and culture centres continued through various agencies, resulting in approximately 87 centres operating in 2012, with a similar number still operating today (Fisher 2016, pp. 8, 63).

However, this financial assistance has not always proved to be either adequate or consistent (Stolte 2012, pp. 229–41; Altman 2011, pp. 330–36; Altman 2016, pp. 175–217; Rothwell 2010, pp. 287–90; Myers 2002, pp. 147–210). Consequently, the performance of many centres has been disrupted and erratic, sometimes imperiling their existence—a significant problem exacerbated by the complex challenges of managing these enterprises in remote regions. Inevitably, this has placed significant pressures on all participants, not least artists who have few other local employment options. Yet, despite the maginitude of these challenges, the more successful art and culture centres have successfully brought Indigenous art to notice by providing an important platform for the production, authentication and sale of innovative art and related products to national and international markets.

4.2. Art and Culture Centres’ Culturepreneurial Networks

Actively fostered by art and culture centres, the reception of Indigenous art was enhanced during the late twentieth and early twenty-first century by an acceleration of prominent exhibitions, gallery acquisitions and promotions. Landmark international exhibitions, frequently featuring Arnhem Land art, accelerated the public awareness and professional critique of Indigenous art despite problematic overtones of primitivism at the time. These exhibitions included Primitivism in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and Modern (1984) at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York, and Magiciens de la Terre (Magicians of the Earth) at the Pompidou Centre in Paris in 1989 (Fisher 2016, p. 94). More broadly, over 100 exhibitions of Australian Indigenous art were staged around the world from 1988 to 1998, many receiving active support from the Australian Government (Wright and Mundine 1998, p. 16). These included the highly successful Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia at the Asia Society Galleries in New York in 1988 which featured Arnhem Land art, and Aratjura (the Messenger), first shown in Dusseldorf Germany in 1993 and later in Denmark and England (ibid., p. 17). In the same period, active Australian Government support led by the National Gallery of Australia encouraged all major state and territory art museums to exhibit and acquire major Indigenous artworks, again frequently including Arnhem Land art (Fisher 2016, pp. 72–79). Artists from Papunya and Arnhem Land were also early inclusions in the Sydney Biennales of 1979 and 1982, as well as the Perspecta exhibitions of 1981 and 1983. Later in the twentieth century, Government agencies, including Artbank, also became major purchasers of Indigenous art, further increasing its exposure and reception (ibid., p. 50). These activities were accompanied by a substantial rise in Australian arts journals such as Artlink featuring Indigenous art, further stimulating the proliferation of Indigenous art production from both urban and remote centres (ibid., p. 79). Building on these pathbreaking events, the talents of individual Indigenous artists were identified and celebrated, creating greater demand for Indigenous art within the contemporary art market. Consequently, Australian Indigenous artists, such as Paddy Bedford and Rover Thomas from the Kimberley region and Emily Kame Kngwarreye from the Utopia community in Central Australia, gained prominence during the last decade of the twentieth century and the first decade of the twenty-first century (Sprague 2014, pp. 81–82).

The success of Australia’s Indigenous art, while catalysed by art and culture centres, would not have been achieved without the ongoing support and commitment of a broader culturepreneurial network with an ability to get the art noticed in the highly competitive art world. This culturepreneurial network operates as a type of symbiotic ecosystem. As with any emerging art, specialists such as art dealers, institutional curators, art historians, art critics, dealers and collectors, navigate the “secret alchemy” of the art world to influence the public taste and appetite for art (Moulin 1987, p. 3; Robertson and Chong 2008, pp. 1, 5, 13, 16; Robertson 2008, pp. 29–32; Findlay 2012, pp. 9–36; Horowitz 2014, p. 9). Since the 1970s in Australia, these participants who were both Indigenous and non-Indigenous actively coalesced with artists as well as their art and culture centre coordinators over a relatively short and intensive period to contribute to the exciting emergence of new Indigenous art.

This coalescence within the culturepreneurial network was symbiotic due to the mutually beneficial exchange of two different forms of cultural capital between separate network participants. In this symbiosis, Indigenous artists and the coordinators of their art and culture centres provided new innovative art laden with the rich, diverse and mysterious cultural capital of Indigenous faith. Other network participants with proximity to art markets also provided their own cultural capital. This was related to their institutionally legitimised collective consciousness of art tastes and values, as well as their knowledge of arts institutions and contemporary art markets (Wherry and Schor 2015, p. 514; Klamer 2011, pp. 145–46; Grenfell and Hardy 2007, p. 30; Bourdieu 1984, p. 3; DiMaggio 1991, p. 134). For Indigenous artists and art and culture centres, this symbiosis delivered market access, recognition and economic benefit. On the other hand, the network’s external participants gained the rare satisfaction of witnessing the global emergence of an extraordinary art movement, and over time also achieved an acceptable mix of new art experience, economic benefit and/or career opportunity. While this symbiosis is not unusual in art markets, its strength and duration here is notable. This appears primarily to be due to the positive long-term relationships between the external network participants and Indigenous artists, art and culture centre coordinators and Indigenous community members—a factor seemingly strengthened by the inclusiveness and appeal of Indigenous culture.6 As a result, these external network participants have frequently become overt and passionate advocates for Indigenous art and culture. Significantly, the operation of this symbiotic network reflects the innovation and knowledge-sharing principles present in other non-Indigenous entrepreneurial networks operating in the global economy (Clark 2016, p. 2; Bessant and Venables 2008, pp. 7–8). A valuable product gained from these exchanges of contrasting forms of cultural capital within Indigenous cultureprenurial networks has been the ongoing encouragement of artistic innovation, thereby further enhancing artists’ prospects in competitive art markets.

5. Indigenous Culturepreneurship

Indigenous culturepreneurship is an original concept that adopts features from existing definitions of culturepreneurship, entrepreneurship and culture, but recasts them based upon the remarkable culturepreneurial approach shown by Australia’s Arnhem Land Indigenous communities. In doing so, this concept not only creates a new form of culturepreneurship, but also challenges Western notions of culture.

5.1. Definition of Indigenous Culturepreneurship

Indigenous culturepreneurship is a culture-driven practice that accommodates the socio-political and economic prerogatives of Indigenous communities, and is manifested in innovative art, cultural and business practices that benefit those communities. When applied in a Western economic context, Indigenous culturepreneurship is valuable not just for artistic innovation but also for the development of other beneficial services, such as cultural tourism.

Indigenous culturepreneurship is defined here as culturally-consistent entrepreneurship, usually conducted by a network of culturally aligned allies, who develop innovative products, services and experiences for the communication and realisation of Indigenous values. As its purveyors, Indigenous culturepreneurs can be described as culturally respectful and informed, innovative, commercially astute, risk-tolerant, resilient, collaborative and inclusive. This definition and these qualities relate specifically to Arnhem Land’s Indigenous people. However, because other Indigenous groups may operate differently, this definition is not necessarily proposed as universal for all Indigenous communities.

Previous Western definitions of the term cultural entrepreneurship or culturepreneurship have described a development process for innovative art- and culture-focused experiences that capture the commercial potential of novel cultural ideas while simultaneously realising broader cultural values (Klamer 2011, p. 141; Wherry and Schor 2015, pp. 514–15). In this form, culturepreneurship is typically attributed to arts institutions and considers culture in the sense of being cultured. It also excludes notable Indigenous traits, such as resilience and inclusiveness, and ignores Indigenous cultural practice or outcomes. Nevertheless, as shown below, Indigenous culturepreneurship employs selected concepts from existing definitions of both entrepreneurship and culture.

5.2. Indigenous Culturepreneurship and Its Relationship with Entrepreneurship

Indigenous culturepreneurship adopts core features from entrepreneurship, specifically from its description as a beneficial and innovative practice anchored in action, risk and the generation of new products, services and/or processes. The term entrepreneur stems from the Latin inter prehendere, corresponding to entreprendre in French (Boutillier and Uzunidis 2013). In the French language, during the Middle Ages, this meant “to take control”, but at the beginning of the fifteenth century, its meaning expanded to include “to take the risk” or “to challenge” (ibid.). In the current era, Hisrich and Kearney highlight the benefits of new innovations from entrepreneurship that deliver “greater competitiveness and enhanced performance”, especially in financial terms, while others note entrepreneurship is vital for trade and national wealth building (Hisrich and Kearney 2014, p. 14; Audretsch et al. 2011, p. xiii). Entrepreneurship is also currently believed to be vital as a generator of jobs, profit and economic development for the survival of countries and corporations (Audretsch et al. 2011, pp. xiii–xiv; Frederick and Kuratko 2010, p. 6; Lundvall 1992, p. 8).

Indigenous culturepreneurship is also similar to entrepreneurship insofar as it necessarily occurs as part of an interactive and changeable network. Calvin Taylor argues that social interaction, market engagement and connectedness are essential for ongoing entrepreneurship, especially in creative industries, because these activities build and exchange critical knowledge (Taylor 2011). He also shows that effective and continued social interaction stimulates creativity and re-design, provides critical market intelligence and allows market participants to seek, cement, develop and exploit business relationships (ibid., p. 34). In essence, this network-based process creates value for enterprises through a vital system of knowledge-gathering and innovation—benefits also identified by John Bessant and Tim Venables in their “fifth generation” model of invention (Bessant and Venables 2008, pp. 7–8).

5.3. Indigenous Culturepreneurship and Its Relationship with Social Entrepreneurship

Indigenous culturepreneurship also borrows part of its purpose from the character of social entrepreneurship, primarily differentiated from entrepreneurship by the objectives and organisation structures used to guide entrepreneurial activity. Social entrepreneurship largely refers to community-based and charitable enterprises seeking social gains, such as poverty alleviation, health care or community improvement. Accordingly, social entrepreneurship is mission-driven, unlike mainstream entrepreneurship that is primarily motivated by the search for profit and competitive advantage (Frederick and Kuratko 2010, pp. 6, 20). Broadly, social entrepreneurship’s mission is to “create value for citizens, stakeholders and the wider community by utilising available resources to exploit opportunities to generate revenue” (Hisrich and Kearney 2014, p. 9). That is, social entrepreneurship aims to provide a distinct social benefit, necessarily generating revenue and profit for that purpose. Likewise, the mission for Arnhem Land’s art and culture centres, is both cultural and economic, and Jon Altman identifies that they usually adopt a hybrid commercial structure, a feature frequently used in social entrepreneurship and also central to the successful practice of Arnhem Land’s culturepreneurship (Altman 2005a).

5.4. Indigenous Culturepreneurship and Its Relationship with Indigenous Entrepreneurship

Unsurprisingly, Indigenous culturepreneurship also reflects the objectives and operating style of Indigenous entrepreneurship, a practice that has only become visible in twenty-first-century scholarship. Indigenous entrepreneurship employs the mission-based form of social entrepreneurship but focuses on Indigenous enterprises conducted for Indigenous benefit (Hindle and Lansdowne 2007, pp. 9–18). Much of the early literature pertaining to Indigenous entrepreneurship emanates from Canada, led by authors Léo-Paul Dana and Robert B. Anderson (Dana and Anderson 2007b). In Australia, the most prolific and cited author is Dennis Foley (2015a, 2015b); (Foley and Hunter 2016). Collectively, this literature establishes an understanding of Indigenous values within the study of entrepreneurship and brings to notice entrepreneurial case studies conducted by Indigenous people. Additionally, it identifies obstacles faced by Indigenous entrepreneurs and differentiates some of their entrepreneurial practices.

5.5. Distinguishing Features of Indigenous Culturepreneurship

Indigenous culturepreneurship, like Indigenous entrepreneurship, is not solely defined by monetary considerations and is usually distinguished by cultural aspirations, networking and sharing (Dana 2007, pp. 3–4). These elements commonly guide entrepreneurial practice for Indigenous people and also frequently determine Indigenous entrepreneurs’ choice of business activities (ibid.). Further, they may affect Indigenous entrepreneurs’ market choices which can function in either monetised or non-monetised forms (Dana and Anderson 2007a, p. 597). These choices may be decided not just by cultural values but through personal networking—a key feature of all forms of entrepreneurship (Schaper 2007, p. 533). For Indigenous entrepreneurship in particular, this highly collaborative and networked characteristic also affects the distribution of benefits from Indigenous enterprises (Dana and Anderson 2007a, p. 598; Schaper 2007). For Australia’s Indigenous entrepreneurs, and equally so for culturepreneurs in Arnhem Land, the distribution of benefits is specifically culturally prescribed, rather than commercially prescribed. This means that benefits are routinely distributed to those who need or seek them, be they members of the family, clan, wider community or even non-Indigenous allies (Dana and Anderson 2007a, p. 600; Schmidt 2011, pp. 78–79). For culturepreneurs to avoid these sharing obligations is to risk acute social ostracism (Furneaux and Brown 2008, p. 137; Schmidt 2011, pp. 78–79).

5.6. Indigenous Culturepreneurship and Its Relationship with Culture

Indigenous culturepreneurship’s links with the term culture are more complex than its relationship with entrepreneurship, primarily because the meaning of culture has evolved to refer to artistic taste, or being cultured, as well as to social categories that described the ways of life of specific populations. The early roots of the term culture ascribe links to agricultural cultivation, but the concept of culture was later strongly shaped by European classical thinking and the Latin term civis, with its idea of civilisation as a hierarchical human domain separate from the natural world (Jenks 2005, pp. 7–8; Eagleton 2016, p. 26). During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, authors such as American philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson and French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu argued for culture to become more descriptive and aspirational. Here, culture described significant bodies of art and cultural work, as well as the desirable moral and intellectual capacities of those (usually elite) citizens who might interact with them due to their specialised training and social standing (Emerson 1906; Bourdieu 1984). Accordingly, culture in its most pervasive sense came to embrace the symbolic, learned and ideational aspects of human society (Jenks 2005, p. 8). From the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, a more democratic and pluralist concept of culture emerged from sociology and anthropology (ibid., p. 12). In this domain, culture became a social category that described the values, beliefs and whole way of life of specific populations—including Indigenous populations—leading to the emergence of cultural studies as a discrete discipline (ibid.).

Indigenous culturepreneurship adopts this meaning of culture pertaining to the values, beliefs and way of life of specific populations; however, its engagement with culture in the sense of being cultured is problematic. Whereas the Western view of being cultured implies an aspirational and hierarchical impression, Indigenous views of cultured behaviour may be markedly different. Using an Arnhem Land perspective, cultural competence is not usually stratified on the Western basis of aesthetic taste, refinement or the merits of so-called civil society (Klamer 2011, p. 153). Instead, cultural competence is more often perceived to be characterised by familial and democratic practices, whereby seniority is determined by levels of knowledge regarding Indigenous faith, and values are aligned with respect, inclusiveness, sharing and concern for future generations.7 Demonstrating another sharp cultural distinction, Western origins of being cultured have often excluded nature, instead positioning humans above and separate to the natural world, therefore explicitly separating cultural refinement from nature. Australian Indigenous culture is the antithesis of this position: This is because, like many other Indigenous and Asian cultures, the features of the natural universe are central to its focus. Moreover, nature’s influences are immanent in Indigenous Australian’s Ancestral narratives, preoccupy their concerns for the future, and are often constantly present in daily thought and behaviour.

Further complicating the relationship between culture and culturepreneurship, the term culture has more recently come to denote a malleable set of values, behaviours and symbols that describe contemporary social behaviours and circumstances—such as pop, urban, café or gambling cultures—thereby substantially extending the scope of culture’s definitions (Belsey 2005, p. 12). Adopting this recent meaning, humans may be seen to become active “agents of cultural evolution”, where culture becomes constantly affected by contemporary influences, and where new cultures frequently emerge (Distin 2011, p. 169; Lewens 2012, pp. 19.1–19.3). Today, individualised and unpredictable self-expression is believed to be heavily influencing contemporary cultures, where once more primal criteria for physical, religious and political survival dominated the cultural evolution of human societies (Inglehart 2018, pp. 1–7). Further, the impact of contemporary media and technology is currently seen to be producing a rapidly changing “aestheticization of life”, with cultural evolution perceived to be advancing more rapidly than biological evolution (Perreault 2012, p. 1; Lütticken 2017, p. 12). As a result of these forces, culture is now described as “liquid” in its character, and is arguably becoming even more molten due to the relentless march of global consumerism and fashion (Bauman 2011, pp. 11–16, 18, 23, 35).

Indigenous culturepreneurship’s relationship with this contemporary liquid meaning of culture is inconsistent in one sense but for some unexpectedly consistent in another. Arnhem Land’s Indigenous culturepreneurship is inconsistent with contemporary liquid forms of culture in that its faith, knowledge and practice—including specific visual forms reflected in art—are rigorously preserved and protected. The worthy long-term aim of this process is to secure the integrity of essential faith, knowledge and wisdom for future generations, rather than accommodate ephemeral practices that may dilute or destroy it. However, Arnhem Land’s culture and Indigenous culturepreneurship also reflect an intrinsic permeable quality that supports the ongoing renewal and rejuvenation of its culture. As shown earlier, this quality is partly achieved by the retelling and restorying of narratives incorporating contemporary influences. However, it is equally well represented by the capacity of Arnhem Land’s Indigenous artists to constantly demonstrate artistic innovation. For those unfamiliar with Arnhem Land’s Indigenous culture, these qualities show an unanticipated affiliation with so-called liquid culture.

6. Key Success Criteria for the Development of Indigenous Cultural Tourism Ventures

Six key success criteria appear to have contributed most toward the success of Arnhem Land’s Indigenous culturepreneurship. Importantly, these criteria may also offer insights for those countries, cities or Indigenous communities developing future art and Indigenous cultural tourism services.

6.1. Established Culturepreneurial Capacity

Like any complex practice or business enterprise, Indigenous culturepreneurship requires willing, capable and committed people with relevant skills as an essential starting point. As described earlier, Arnhem Land’s Indigenous people did not become culturepreneurial overnight. Rather, their cultural history and experience predisposed them to it. Throughout their history, the threads of art, innovation and collaborative engagement are clear, and over the last half-century these capacities have been well demonstrated by the representation of complex visual languages and sacred designs as appealing and successful contemporary art. These capacities have also been evident in culturally infused socio-political historical moments, such as the Bark Petitions and the Aboriginal Memorial, as well as in more contemporary art and cultural events, such as the highly successful contemporary rock band Yothu Yindi and the annual Garma Cultural Festival, another major cultural tourism attraction in Arnhem Land. During their extraordinary history, Arnhem Land’s people accumulated the skills to constantly incorporate innovations into their art. As a result, this now provides an ideal medium for both creative expression and economic benefit, as well as for the wider sharing of cultural concepts about the country, sacred sites and land custodianship. This combination of political awareness, established skills, art and culture creates an ideal foundation for Indigenous culturepreneurship as well as other cultural tourism enterprises.

6.2. Cultural Integrity and Indigenous Control

The ongoing prosperity of Indigenous culturepreneurial practice will undoubtedly rely on the unwavering authenticity and integrity of its culture’s distinguishing features. For Arnhem Land’s Indigenous communities, the control of sacred designs and secret narratives is intended to ensure their faith and culture are not diminished. Equally, this approach is critical to those who conduct Indigenous enterprises in order to ensure customers receive products, services or experiences that possess indisputable cultural integrity. To ensure this occurs, culture-focused experiences must ultimately function within the governing control of informed and respectful cultural stakeholders. Of course, this approach is just as essential to avoid exploitation, restrict damage to cultural assets and ensure a suitable return on investment for cultural communities. While this principle may not have been always comprehensively implemented in Australian art and culture centres, it remains is a core feature of Arnhem Land’s successful art and culture centres where Indigenous governance not only controls commercial imperatives but also manages the ownership, communication and security of cultural protocols, art designs and communicated narratives. For other cultural enterprises, this criterion is expected to be similarly critical.

6.3. Patient Capital and Art and Culture Centres

Indigenous culturepreneurship, like other entrepreneurial practices or ventures, requires the ongoing availability of various forms of capital combined with a suitable organisational model to achieve sustainable socio-cultural and economic benefits. The absence of various forms of capital, rather than the absence of entrepreneurial skills, has been identified as arguably the major barrier to Indigenous entrepreneurship. However, financial capital together with human, social, physical, organisational and technological capital have all been identified as essential for Indigenous entrepreneurs and, by extension, for Indigenous culturepreneurs. In the case of Arnhem Land’s art and culture centres, long-term Government funding, while at times erratic, has been the genesis and foundation on which successful centres have grown. From this base, funding from commercial sources has also allowed capital in its other requisite forms to precariously accumulate. However, for art and cultural ventures to succeed over the long term, adequate long-term patient capital is essential, together with a suitable organisational model to successfully manage it. In this context, patient capital refers to long-term capital that allows a venture to be well-established and demonstrably viable before repayments are enforced. Based on the success of Australia’s contemporary Indigenous art, and notwithstanding some inevitable failures caused by the fragility of early ventures and cashflow problems due to inadequate financial capital, it seems clear that the existing Australian art and culture centre model is highly suitable for the conduct of cultural enterprise. Directed by Indigenous people for Indigenous people, it is now a proven organisational model without which Arnhem Land’s culturepreneurship and art could not have succeeded and, if removed, could not continue.

6.4. Suitable Long Term Coordinator/Managers and a Culturepreneurial Network

Like entrepreneurship, culturepreneurship only proceeds successfully with suitable operational management and the support of like-minded capable allies. Over the last half-century, different Australian art and culture centres have waxed and waned in their performance, but the more successful centres appear to reflect the benefits of stable Indigenous governance as well as consistent and suitable coordinator/managers (often non-Indigenous), notwithstanding the latter having been more susceptible to constant turnover due to workload and limited resources. While art knowledge and commercial expertise are both patently valuable for the coordinator/managers of these centres, it also appears that cultural knowledge, affiliation with cultural values and long-term community relationships are equally critical for managerial success. These characteristics allow coordinator/managers to be effective external advocates and also help them to build essential trust and support within Indigenous communities whose moiety systems emphasise strong familial-style relationships. Taking this principle more broadly, it’s also apparent that effective continuing relationships with the interconnected culturepreneurial networks described earlier has been a key success factor. This is not just because these connections provide valuable access to art markets but also because they echo the successful collective system of innovation and distribution evident in other forms of successful entrepreneurship.

An often misunderstood Australian Indigenous attribute, Deep listening, may also be a beneficial management factor for effective culturepreneurial ventures. Deep listening is a powerful Indigenous leadership attribute identified as evident in many language groups within Australia, but may be poorly understood by people unfamiliar with Indigenous culture and therefore misinterpreted as reticence, slow thinking or even ignorance (Brearley 2015, p. 91). Instead, deep listening involves patience, listening respectfully and responsibly, and observing oneself as well as others (ibid., pp. 91–95). Accordingly, deep listening offers a highly intellectual and valuable interpersonal process that is “a way of learning, working and togetherness informed by the concepts of community and reciprocity” (ibid.). As such, deep listening can be valuable not just for negotiation and trade but also for broader network and community building. While clearly a valuable attribute, deep listening is often alien to the pressures of fast-paced Western commerce and therefore may act as an unintended barrier between Indigenous culturepreneurs and participants from non-Indigenous societies and economies. However, for many Indigenous Australians deep listening represents a crucial method to consider serious issues that affect the welfare of future generations, especially those relating to matters of culture. Anecdotally, deep listening also appears to have been usefully adopted, at least in part, by long-standing non-Indigenous members of Arnhem Land’s culturepreneurial networks, and is likely to become an increasingly important requirement for those participating in future Indigenous culturepreneurial ventures.

6.5. Market Competitiveness and Innovation

To succeed in contemporary markets, any cultural offering must be both attractive and competitive in its selected key markets. Culture alone is not sufficient for products or services to succeed. Instead, offerings must be supported by features that make them attractive to tourists and other customers. Art, as well as music and performance, facilitate this attractiveness because they can be evocative, aesthetically powerful and/or conceptually intriguing, even without cultural explanation. In this way, Arnhem Land’s fine art appears to compete successfully in contemporary art markets because of its beguiling mix of these qualities. Arnhem Land art is also increasingly promoted internationally because these markets are larger (Australia occupies only around 2% of the value of the global fine art market), reputedly more receptive to fine art and offer better exposure for future marketing activities (McAndrew 2017, p. 37).

Nevertheless, ongoing competitiveness in contemporary art markets demands constant innovation—a feature well demonstrated in fine art practice by Arnhem Land’s Buku centre, and also shown in different modes by other art and culture centres. Artistic innovation in Indigenous art and culture centres contrasts with the style of innovation described in Western business literature. For Arnhem Land’s artists, artistic innovation is clearly facilitated by the information, resources and facilities provided by operationally successful art centres and their symbiotic market networks. These centres provide an essential fertile art-school style context for artistic innovation by participating artists whose own creativity is primarily inspired by connections with fellow artists, an immanent relationship with their nature-based culture, and by an inherently restless and innovative artistic spirit that seeks new ways to express ever-present cultural ideas. Will Stubbs, Buku art and culture centre coordinator observes, “innovation is a natural human characteristic”, and “our role is as a gardener … we don’t do the genetic modification.”8 Accordingly, this artistic innovation is neither product- nor market-oriented in the Western economic sense but is more interconnected, organic and spiritual in both its concept and execution. Yet, whatever its source, it is apparent that innovation has been an essential component of the success of Arnhem Land art, and is likely to be equally important for other cultural enterprises.

6.6. Ongoing Marketing Support

For Indigenous culturepreneurship, like most enterprise, the principle tenets of marketing still apply, especially effective promotion and distribution. The wider success of artists from Arnhem Land’s art and culture centres can be significantly attributed not just to the artists and the centres themselves, but to the marketing support gained from network allies. This is notwithstanding increasingly successful attempts by some centres to use online or direct marketing methods themselves. Historically, Australian Government agencies have actively purchased Indigenous art, sponsored and promoted domestic and international exhibitions, and initially subsidised retail distribution in urban centres (Fisher 2016, p. 7). They also continue to provide some financial assistance to art and culture centres. Among other network allies, institutional and commercial galleries have invested extensively in exhibitions, and academics and journalists have written compellingly about Indigenous art. Partly as a response to these initiatives, collectors have invested in Australian Indigenous art. Similarly, commercial sponsors, such as Telstra, continue to provide valuable support and certainty for MAGNT and NATSIAA as part of the Darwin Festival. Without the visibility and extended support of such allies, the qualities of Arnhem Land art would not have been adequately communicated, understood or appreciated. Just as importantly, without the economic return and momentum gained from this marketing support, the development of Arnhem Land’s art may not have continued.

Overall, it appears inevitable that art and culture centres will increasingly use online and other direct sale methods for their art, as well as for other associated products and cultural experiences. However, to continue to succeed in the wider economy broader culturepreneurial networks will remain essential, not just for their considerable promotion and distribution benefits but also for their positive influences on future innovation.

Looking forward, the development of expanded Indigenous cultural tourism services, while undoubtedly attractive for many participants, is unlikely to be either quick or simple. Instead, as shown, it is likely to require communities with the willingness and established capacities to innovatively design and govern these services. They must then be supported over the long term with the patient capital, facilities and supportive networks necessary to market them to suitable potential customers.

7. Conclusions

This investigation introduces and defines the original concept of Indigenous culturepreneurship and suggests criteria for those interested in developing future Indigenous cultural tourism ventures. Indigenous culturepreneurship challenges existing western definitions of both culture and culturepreneurship, reinforces the role of innovation in both contemporary Indigenous art and culturepreneurial practice, and illuminates Indigenous culturepreneurship as an important future-making practice. That is, a valuable developmental, socio-political and economic initiative for Indigenous communities concerned with maintaining and promoting their cultures as living, growing and relevant in the contemporary world.

Indigenous culturepreneurship describes a valuable approach that may concurrently support, rejuvenate and advance living Indigenous cultures. As an innovative practice that directly serves the needs of Indigenous communities, it applies and promotes Indigenous cultural values. It also fosters the development of new cultural products, services and experiences, such as cultural tourism. If these offerings meet the suggested success-criteria, they may also be made more accessible, meaningful, attractive and interculturally effective for their audiences, while still operating within cultural protocols that retain their cultural integrity.

Further research among other Indigenous communities will likely identify other valuable and culturally significant variations in the practice of Inidgenous culturepreneurship. Additionally, further research may also clarify the distinctive character of Indigenous approaches to innovation, identify the contributions of Indigenous innovation to the emerging field of social innovation, and provide new dimensions for both social and Indigenous entrepreneurship. Such research may benefit both Indigenous and non-Indigenous enterprise and allow new collaborative initiatives to emerge that showcase Indigenous culurepreneurial practice and innovation. This may then accelerate future-making initiatives for Indigenous communities and simultaneously allow their unique innovative qualities to be appropriately acknowledged by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Adhuri, Dedi Supriadi. 2013. Traditional and ‘Modern’ Trepang Fisheries on the Border of the Indonesian and Australian Fishing Zones. In Macassan History and Heritage: Journeys, Encounters and Influences. Edited by Marshall Clark and Sally K. May. Canberra: ANU E Press, chp. 11. pp. 183–203. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, Jon. 2005a. Brokering Aboriginal Art: A Critical Perspective on Marketing Institutions and the State. In Kenneth Myer Lecture in Arts and Entertainment Management. Edited by Ruth Rentschler. Geelong: Centre for Leisure Management Research, Bowater School of Management and Marketing, Deakin University, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, Jon. 2005b. From Mumek a to Basel: John Mawurndjul’s Artistic Odyssey. In “Rarrk” John Mawurndjul: Journey Though Time in Northern Australia. Edited by Christian Kaufmann. Basel: Museum Tinguely/Crawford House Publishing, pp. 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, Jon C. 2011. Alleviating Poverty in Remote Indigenous Australia: The Hybrid Economy. In Readings in Political Economy: Economics as a Social Science. Edited by George Argyrous and Frank Stilwell. Melbourne: Tilde University Press, pp. 330–36. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, Jon. 2016. Bawinanga and C.D.E.P: The Vibrant Life, and near Death, of a Major Aboriginal Corporation in Arnhem Land. In Better Than Welfare: Work and Livelihoods for Indigenous Australians after C.D.E.P. Edited by Kirrily Jordan. Canberra: ANU Press, pp. 175–217. [Google Scholar]