1. Introduction

Stanley Morison, the recognized type designer of his age insists, as per the epigraph, that the modern letter must be nothing more than an envoy of that which dare not speak its name: a self-assured imperial system that accommodates no imagining beyond the given form of the Roman letter. This manner of thinking is not restricted to the crafting of type, but is symptomatic of an approach Western intellectual thought has on occasion taken in producing the histories of many indigenous writing systems of Africa.

1 These productions are instrumentalist in nature, with no tolerance for anything beyond a specific set of taxonomic criteria not fully designed for the richness of their task. In contrast, this paper offers dynamic categorical contributions to the imbricated fields of philology and typography by foregrounding a moment of textual innovation from the past so as to make a case for an intellectual commitment to a method of practice we may observe in the present that I term ‘typographic reification’.

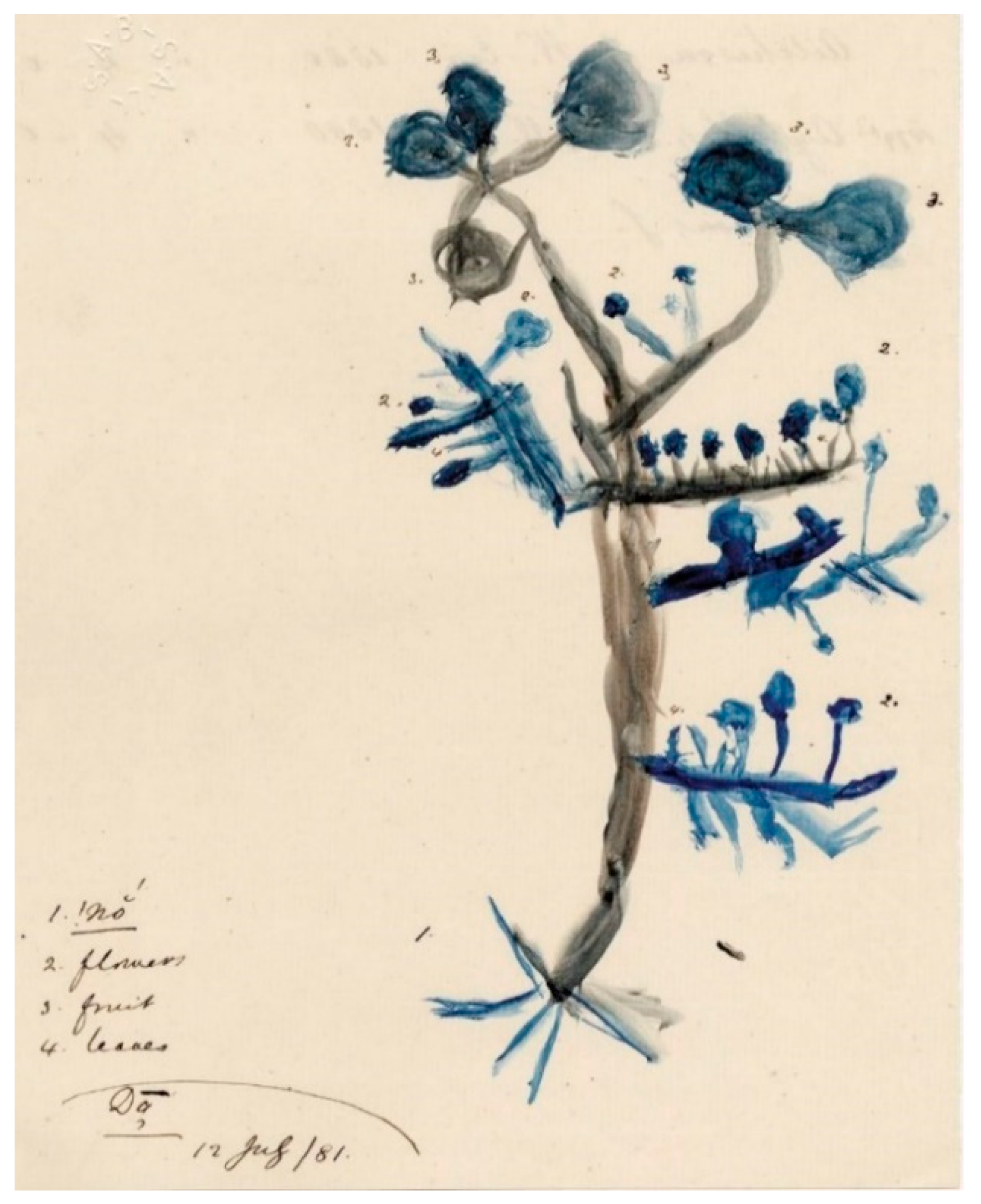

This ‘reification’ is the fulcrum of the ancient drive of the indigenous people of Southern Africa (the Khoe and the San) to offer an excess beyond the translation of their world into a Roman alphabet (the given form) by linguists that came with this aim in mind. This excess reveals itself acutely and specifically in the notebooks (

Figure 1) of an anthropologist and linguist from the late 1800s—Lucy Lloyd. Her archive of documents that resulted from interviewing and transcribing words and ideas of the ancient San and Khoe people of Southern Africa discloses a rich compellation comprising images of fauna and flora that provide an understanding of the worlds of the San and the Khoe that could not be excluded from the process of translating their language and knowledge claims into a readable form. The benefit of looking at this precise point in textual history thus relates to Lloyd’s committed accommodation of the said images and her careful annotation on them, in one manner of thinking—extending the formal and intellectual possibilities of transcribing precisely because of the productivity in maintaining the word in conjunction with the visual.

Stated differently, Lloyd did not allow a suppression of the indigenous discourse of the Khoe and San drawings of plants and insects that offered insight to their field and mountain homes, but instead allowed this discourse to enjoin her own written annotations to stage a new geographic narrativity that takes place at the site of the transcripted document—a reification of sorts. This approach distinguishes her archive in a particular way, as her notes and the images cannot be imagined apart from each other and would be far the poorer for this separation. The approach I have taken in making this argument is certainly not without distinct dangers, as it relies heavily on a subjective reading of the archive from the perspective of one concerned with highly particular visual and textual ideas. It is thus important to foreground at the onset of this text that the initial compilation of the Bleek–Lloyd archive is ultimately based in 19th century methods of translation and transcription which are all that is left, for there are no speakers of these languages rendering the archive as a record of extinction. Therefore, how to assess its methods, given that there are no more active speakers, is intensely, epistemologically problematic. Faced with the option of abandoning a reading of this archive beyond the obvious or disciplinarily comfortable finally gave way to a desire to think at the limit of what conventionally falls within archival and creative remits. This study is thus of potential relevance to an international readership with an interest in early indigenous Southern African archives and graphic language, and the convergence between these two concerns.

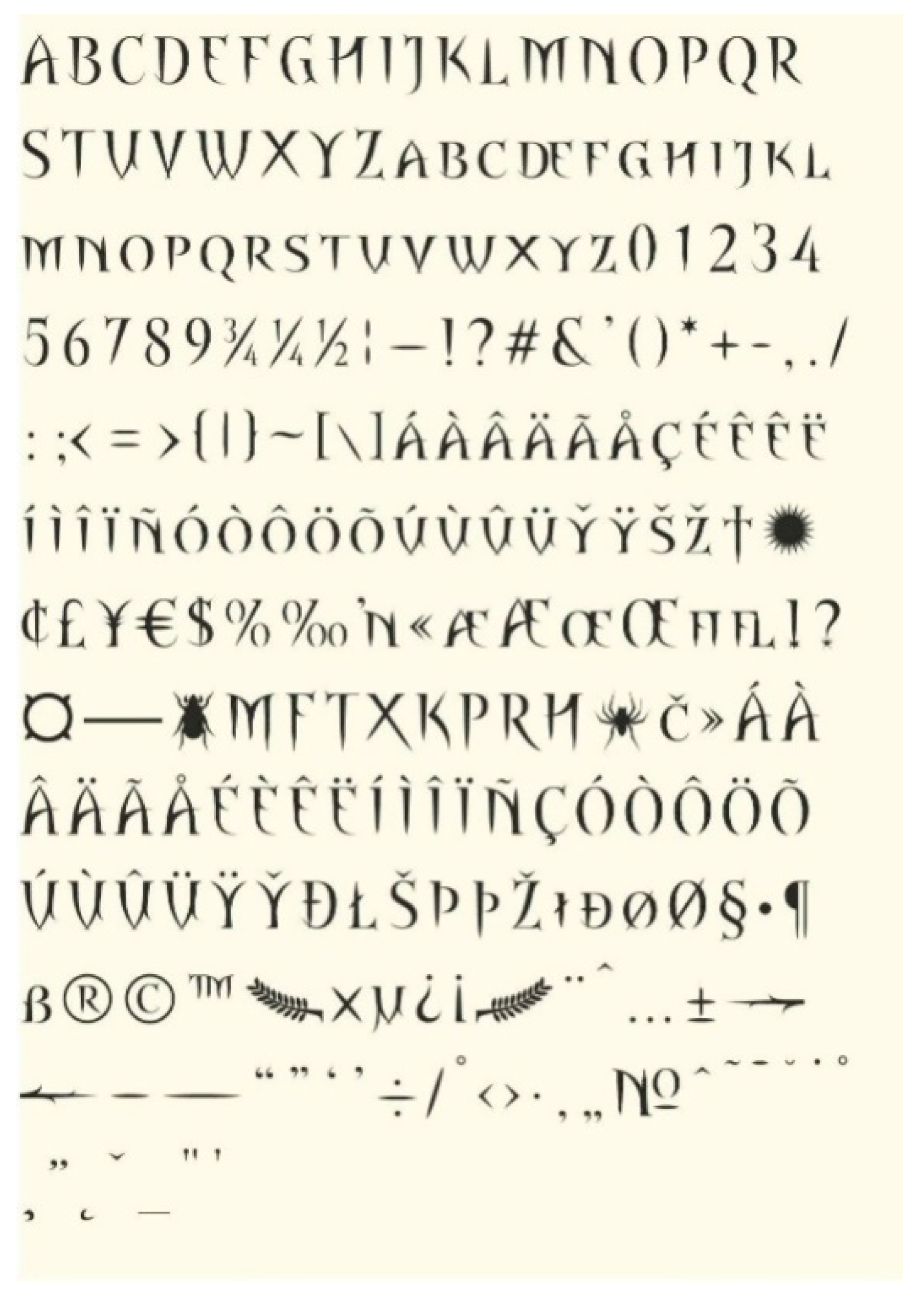

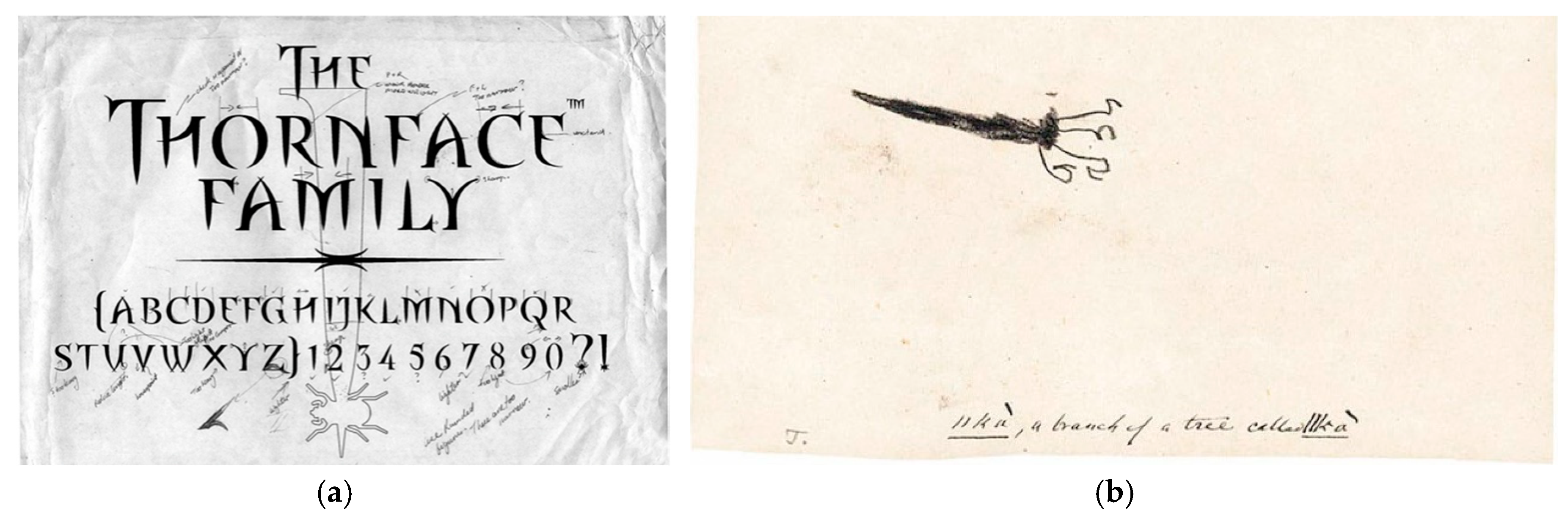

In a modern context, the echo of this intellectual moment seen in the Lloyd archive is unequivocally visible in the alternate symbols and diacritics of digital open type designs developed by Jan Erasmus and marketed by Linotype Corporation internationally. Specifically, the creation of the Thornface design by Erasmus articulate a particular understanding of geographic space reflected in the letterform by certain accommodations of floral and faunal imagery. Thus, if the Lloyd archive may be seen as an opening that offered the intellectual space for a reification of a specific place (South Africa) constituted in her notations on the images of the natural environment provided by the San and Khoe, it was Erasmus, at the dawn of the digital age, that was able to achieve typographic forms that created the reificatory conditions of the very place using startlingly similar imagery to what we may observe in the Lloyd archive. Although I am focusing on the approaches and artefacts of one designer so as to emphasize only the parallels between this designer and the archival material, the implications are both timely and emancipatory for humanities scholarship and production: Western letters are still open to intellectual scrutiny in relation to their change over time, and how they may yet proceed to move in the world even as they assure us of past intellectual moments that assist in their becoming.

2. The Lucy Lloyd Archive: Composition and Productivity

The Lucy Lloyd archive that will form the basis of this article is perhaps more conventionally understood as part of the Bleek–Lloyd archive. This dual naming refers both to Lucy Lloyd (1834–1914) and Wilhelm Bleek (1827–1875), a German philologist and linguist (eventually becoming her brother-in-law) who partnered with Lloyd and worked most intensely with her in Cape Town at a shared home in the suburb of Mowbray from 1870 until his death in 1875. Despite Bleek being the formally trained scholar and scientist between the pair, Lloyd took the joint enquiry to new and exciting designations including the expansive notations on the images produced by the San and the Khoe that was not as central in the work of Bleek. Lucy Catherine Lloyd arrived in South Africa at the age of 14, originally coming from the West of England. She was introduced to the study of the San and Khoe when she came to live with her sister Dorothea Bleek (who herself contributed one notebook to the collection) and her husband Wilhelm Bleek. In terms of her professional life, Lloyd was a custodian of the Grey Collection for many years (a vast number of books donated by Governor Sir George Grey that included medieval manuscripts) and worked for the South African Library for a time. It was, however, her research with the San and the Khoe that would occupy her for most of her working life.

The Bleek–Lloyd archive is not a new discovery to the academic world, with numerous monographs and journal articles

2 explicating the archive itself or the methods used to bring the transcriptions found in the archive into existence. The collection consists of 151 notebooks that span dictionaries, linguistic transcriptions, notated oral histories and the evocative sketchbooks (the focus of this text) that contain watercolor images, pencil drawings and intricate diagrams of hunting strategies (

Figure 2).

Central to the comprehension of the archive beyond the surface of the pages is an understanding of the subjects that made the archive possible, thus how the relationships between people, formal knowledge and context worked together to bring this archive to our door. The informants, who made the archive possible, were mostly recruited from the Breakwater Prison at the waterfront harbor in Cape Town. They were men who had experienced heavy penalties by colonial judges who convicted them of crimes ranging from cattle theft, petty theft and murder.

They all varied in their geographic origin and linguistic groupings, but all held highly crucial knowledge about the languages, customs, medicinal and environmental strategies that had ensured a way of life for over 2000 years in South Africa despite the precarious status of these peoples at the Cape in the late 1800s when the archive was being produced. The names of the informants, and on occasion their photographic images ensure, even in a cursory reading of the archive, that they were afforded specific acknowledgement in relation to their contributions and participation in the project that saw Lloyd herself (however unevenly) receive the formal recognition of a PhD awarded by the University of Cape Town (the first honorary doctorate awarded to a woman in 1913, one year before she died). The names of the primary indigenous informants include: A!kunta; Kabbo; ≠Kassin; Dai!kwan; !kweiten ta; Han≠kass’s, Tamme and !Nann who ranged dramatically in terms of their ages and experiences that suggest Lloyd had a diverse group to work with despite the difficulty intergenerational and inter-cultural work brings. As noted by

Bank (

2006) in his masterful work about this archive:

The collaboration between researchers and the informants that made this salvaging operation possible provides an extraordinary tale not only of survival and resilience, but of hope and creative possibility…It is an immense resource the world has only recently begun to value as it deserves, produced by a handful of people working closely together across social divides. If we set that against the familiar backdrop of settler violence and dispossession, amounting even to genocide for the Bushmen of Southern Africa, this meeting of worlds deserves to be celebrated and recounted again and again.

The custodianship of the project reached a high point when it was completely digitized by the University of Cape Town forming the Bleek-Lloyd digital archive in 2007. This was followed by the formal protection afforded by

UNESCO, deeming it a heritage resource in 2009 by including it in the

Memory of the World Register. The nomination form used in the process of assigning items to the memory register asks specifically about the significance of the object/collection related to

time;

place;

people;

subject and theme;

form and style;

society, and finally

spirituality and community.

I list these categories and the various answers to their promptings in relation to the Bleek–Lloyd archive below. The text serves the Bleek–Lloyd archive well, save for the very ignorant answer to the question on style and form. This answer not only alerts us to a lack of understanding related to visuality by the authors, but serves in my view, as a mandate for the argument of this article to be taken seriously by inviting a productive vexation in light of the ignorance displayed. The texts that answer the categorical prompts follow below

3:

Time: “The documentation about the |Xam language, life and mythology was gathered at the crucial moment of disintegration of this culture in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. Studies of other hunter-gatherer societies done elsewhere were undertaken later, when those societies were already drastically transformed by colonial expansion. The collection of this data was done fairly early, so it represents a unique, authentic early glimpse into the consciousness of hunter-gatherer societies.”

Place: “The Collections document a people of an under-researched area of South Africa, the arid Cape interior. This is one of the richest sources of information on this region that we have. However, it transcends this local significance in that it sheds light on all hunter-gatherer societies, not only in South Africa, but in the rest of the world.”

People: “The San peoples were responsible for some of the world’s finest rock art, but otherwise had a very simple material culture. The culture collapsed owing to the intrusion of the new inhabitants who brought with them diseases and undertook active measures to eradicate them.”

Subject and theme: “Themes which emerge from this Collection are: the system of consciousness of hunter-gatherer societies, which is a unique heritage of a distinct culture; the interaction of this culture with European colonialism and expansion; and the interaction between hunter-gatherers and other societies, including indigenous pastoralist societies.”

Form and style: “Not special: ordinary notebooks with tales and translations, grammars, correspondence, pictures.”

Social, spiritual and community significance: “These collections shed light on a unique religious system, a unique consciousness, a unique system of representation, all of which are now extinct, and this is almost the sole resource for knowledge of these systems of thought. It also sheds light on other hunter-gatherer societies and the way in which pre-capitalist hunter-gatherers interpreted their universe. These collections provide the only means of hearing one of the most fascinating of the ‘lost voices’ of humanity.”

3. Excess and Desire in the Archive: The Stakes of the Image

What is clear in both the intellectual investigations and the texts suggesting bureaucratic protection for this collection is that it represents not only the first project that seeks to systematically understand and preserve the language and culture of the San and Khoe, it is also unique as a collaborative event between generations, languages, nationalities and many other units of measure used to gauge social subjectivity. This archive thus constitutes a special way of thinking the challenges that emerge when cultural worlds are contorted to a written form. In this vein, despite the many successful aspects of the project, both Bleek and Lloyd offer striking moments where they discuss their inability to completely capture the subjects at hand in letters, and also when writing itself offers its own insufficiency. There are a number of examples of this, but the attempt to convey, in writing, the specific vocal call the bushman hunter of a springbok gave after an animal had been shot must surely be one of the most formidable challenges to the project of transcription

4.

The call was described as “a peculiar liquid kind of call’ (

Bank 2006, p. 360) by Lloyd who eventually named the sounding: ‘

kkou wwe, kkou wwee’. The springbok hunt itself, despite the difficulty of capturing the vocality of the call with precision, gave rise to an intriguing combination of an abstract diagram (a highly systematic work) drawn by /Han≠kasso and annotation by Lloyd (see

Figure 3). The combination of the annotation and the abstracted forms of the diagram disclose a great deal of information about the hunting strategy of the day for bushmen. The grouping of various dots indicates the kinetic direction of the herd of springbok and, in some instances, stand in for hunters themselves. The dashes represent particular positions in the tactical schema and crucially illustrate the use of a species of special equipment (sticks with ostrich feathers). The texts on the diagram that offer these readings follow in numerical order, to be read in conjunction with the image:

From this direction the herd of springbok comes;

Here they go towards the row of sticks with feathers tied upon them;

Here stands a woman who throws up dust into the air. Rows of sticks with feathers tied upon them, used in springbok hunting, to herd the game. The lines represent the bushmen lying in wait for them.

There can be no doubt that the subjects themselves (the san and khoe) imaged their world with great fluidity, and this primarily done through drawing with pencil or charcoal, or using watercolor paint and brushes. It must be made clear that these drawing instances are not to be seen in the mode that scholars refer to as rock art, a distinct species of imaging highly dependent on geographic context and custom. The images I discuss bring news of special animals (

Figure 4), or descriptions of important plants with an ambition perhaps more akin to that of reportage. A special account highlights a confidence that this way of conveying ideas invited in various individuals as recounted in

Specimens of Bushman Folklore:

One evening, at Mowbray, in 1875, Dr Bleek asked Dia!kwan if he could make pictures. The latter smiled and looked pleased; but what he said had been forgotten. The following morning, early, as Dr Bleek passed through the back porch of his house on his way to Cape Town, he perceived a small drawing representing a family of ostriches, pinned to the porch wall. As Dia!kwain’s reply to the question.

These manners of images were thus critical to the discourse of informants and worked in sophisticated ways to make the various knowledge claims

5. It would be a mistake, however, to believe that the making of images was the preserve of the San and Khoe informants. There is clearly a highly sensitive mind at play in the annotations of the transcriber (Lloyd) that was graphically astute in relation to the economy of the page and the placement of her script so as to both be legible and yet integrated with the image (see

Figure 5). This constitutes, in the most expansive sense, a form of graphic strategizing that is hard to ignore. This is the case even in instances where Lloyd deploys numerals many times over as per her annotated tree in

Figure 6, where the numbers seem to become part of the leaves, arranged to enforce the silhouette of the drawing and in no way infringing on the fluidity of the water color medium. It is also worth noting that the script used by Lloyd was a practiced one, and in her notebooks, we come across instances where every single letter of the alphabet is written carefully in lower case script, the result of a practice exercise, in addition to numerous scribbles and flourishes that suggest the desire to relieve an ink pen of excess fluid or else to ensure a clean stroke before annotation takes place. These manifestations of preparatory work in the sketch books and notebooks certainly show at the very least a self-awareness in the formal qualities of the writing that would enjoin the images.

4. The Gifts of the Archive for the Realm of Thought: Dialogical Encounters

The intellectual extension demanded in understanding the complicated product of inter-cultural, inter-linguistic and inter-gender transcription that is the Lloyd archive is perhaps the true productivity that the collection offers the world of academic scholars. If scholars have thought the difficulty of subjects working beyond their own situated-ness in cultural and political imbrications to bring the archive to existence, a commitment to this line of thought must certainly captivate scholars themselves, in the present moment, to think of their own biases and particular disciplinary concerns and constraints. This archive is thus an exemplary symptom of a productively unsettling problem—a dialogic predicament. This predicament is best broached by a strategy of

dialogic reading, signaled by Dominique LaCapra (writing in a varying context) as a point of opposition to the modes of representation in addition to an essential idea that holds open a space for critique against a “self-sufficient research paradigm” that establishes, almost immediately, the impossibility of a “value-neutral” (

LaCapra 2000, p. 65) position. By this, LaCapra invites a perspective on text that is both delimited by the constraints and contexts against which it is read, and an opening which always avails it to critiques and further reading:

Basic to it [Dialogic Reading] is a power of provocation or an exchange that has the effect of testing assumptions, legitimizing those that stand its critical test and preparing others for change… A dialogic approach is based on a distinction that may be problematic in certain cases but is nonetheless important to formulate and explore. This is the distinction between accurate reconstruction of an object of study and exchange with that object as well as with other inquirers into it.

This “exchange” is a highly contingent proposition, not content to accept normative accounts, and brings into play a relationship between past and present, filled with the ethical-political paradigms these accounts embody in their reflection of history:

Dialogic exchange indicates how the basic problems in reading and interpretation may ultimately be normative and require a direct engagement with normative issues that are often concealed or allusively embedded in a seemingly ‘objective’ account. It also brings out the problem of the relations among historiography, ethics, and politics. For the dialogic dimension of inquiry complicates the research paradigm and raises the problem of the voice and subject-positions in which we respond to the past in a manner that always has implications for the future and the present.

As I have suggested, we may read the images from the Lloyd archive in a special way that sets it in a dynamic position, one that offers a seriousness to the picture-word creations that operate as a moment of unity, serving as a mode of reification that attempted to hold certain faunal and floral knowledge and descriptions from the South African landscape on the transcriber’s page. To fully realize the importance of this moment means we must see it anew, perhaps (I would suggest) in contemporary work that is at once different but similar, offering the past that we can thus consider a heritage for the present. To take the idea of the dialogic reading of this archive seriously means our interpretation of the archive must extend our intellectual designations. I turn now to the work of typographer Jan Erasmus, a case in point. His combination of letters and special characters that both operate as alphabetical assignments and images show us the thorn trees, birds and spiders that constitute the South African wilderness. At times, they mirror the images we see in the Lloyd archive in both content and form.

5. Drawing a Full Circle: Thornface Font

Jan Erasmus conceived his acclaimed digital typeface in 1995

6. It was named

Thornface and continues to be sold as a digital font. It is used in many differing contexts, but in Erasmus’ thinking, it is the manner the letters intimate emotive images that is the central feature of the font. These images are related to the thorn tree, elephant and rhino, specific birds, the spider and other insects that are clearly shown in his glyph sheet (

Figure 7).

Erasmus states in his monograph (2007) that the letters were conceived of as objects that have a direct relationship to the fauna and flora of the Karoo, the desert area where many of the Lloyd archive informants resided. It is no surprise then (as the selection of archival images below will show) that there is a clear resemblance to the forms created by Erasmus, and those drawn by the San and Khoe (

Figure 8). Erasmus discusses the process of producing the alternate exclamation mark (seen in both the sketch of

Figure 8a and the serif forms as seen in

Figure 7) as one achieved by an acute observation of the thorns and their relationship to the tree and bark, only possible by first-hand observation:

Fiscal Shrikes, also known as Jacky Hangman birds (and apparently used for ‘green’ pest control) find thorns useful as storage places for bugs, which they eat in times of drought. This was the inspiration for the alternative exclamation mark [that visually articulates both a thorn and an insect detained upon it].

The semi-serif finish [of the letter forms] are based on what a thorn looks like when you pull it off a branch and a little bark remains.

The experimentation embraced by Erasmus is concerned with extending the letter form to receive a specific environment through elements that comprise it. When contrasted with images from the Lloyd archive, the specificity of the place Erasmus consults is striking. The comparisons used below from the archive relate to the thorn tree (

Figure 9), and the mirroring of a spider (

Figure 10) that offer at the very least a shared vision of a specific place rendered in forms that are consciously assigned to pages.

6. Conclusions

Reification, as identified in the Lloyd archive (comprising drawn faunal and floral images and their elegant annotations), brings the world of the Khoe and the San to our door. These creations offer the conditions for a dynamic concept: they invite a difficulty that is a potential “virtue” for the scholar in the sense that they ask that we see, within them, the genesis of a textual contribution to the intellectual history of Southern Africa. Despite the epistemic problems that arise in the face of engaging a 19th-century archive that has no mother tongue readers left, the reading of reification argued for in the Lloyd archive is fully exploited in the modern digital typeface, Thornface, developed by Jan Erasmus more than a century later. In this vein, typographic reification, as tabled in this text, is more than a theoretical complication to the otherwise unified study of typography and the archive today; it is a timely call to think with even more commitment of the critical constitution of the so called ‘history of the text in Africa’. In this light, the past may indeed be seen as joining the present if we allow ourselves to see this dialogical proposition. Any lesser understanding would surely not serve the newness so vital to theory and would be a far cry from the conceptual agility displayed in constituting the Lloyd archive that ultimately delivers a point not irrelevant to typeface development: letters must always serve as envoys to greater worlds.