Abstract

An image on an Attic red-figure kylix attributed to the Antiphon Painter, showing a single youth wrapped tightly in a mantle, represents a type of figure often found in pederastic courting scenes and scenes set in the gymnasium, where male bodies were on display. Subject to the gaze of older men, these youths hide their bodies in their cloaks and exhibit the modesty expected of a boy being courted. While many courting scenes show an erastês approaching a tightly-wrapped erômenos, in this scene, the boy stands alone with no source of modesty-inducing gaze within the image. Combined with the intimate manner in which the user of this cup would experience the image as he held it close to his face to drink, it would appear to the drinker that it is his own gaze that provokes the boy’s modesty. This vase is one of several in which we may see figures within an image reacting to the eroticizing gaze of the user of the vessel. As the drinker drains his cup and sees the boy, the image responds with resistance to the drinker’s gaze. Though seemingly unassuming, these pictures look deliberately outward and declare themselves to an anticipated viewer. The viewer’s interaction with the image is as important to its function as any element within the picture.

1. Introduction

The interior of an Attic red-figure kylix in Baltimore attributed to the Antiphon Painter shows a single male figure, young and beardless, with his mantle pulled over his head and wrapped tightly around his body (Figure 1).1 A sponge and strigil hanging in the background to the left of the figure set the scene in the gymnasium, where male bodies were perfected and scrutinized. An inscription to the boy’s left reads “ho pais kalos”, “the boy is beautiful”. The exterior of the vase also features scenes of the gymnasium. Both sides show boys practicing the pankration, an ancient Greek no-holds-barred fighting sport combining boxing and wrestling, in which only biting and eye gouging were banned. On the better-preserved side (Figure 2), one of the athletes attempts to gouge his opponent and is reprimanded by the referee (Williams 1984, pp. 165–67, no. 111). The athletes are fully nude, as was standard in ancient Greece, while the onlooker to the left covers his entire body and most of his face, much like the youth in the tondo. This type of figure, a boy reticently hiding his body, is often found in scenes set in the gymnasium or in pederastic courting scenes—in other words, in settings where boys are subject to the prurient gaze of older men. These youths hide themselves in their cloaks and exhibit a sense of modesty that was valued and expected of boys in ancient Greece being courted by older men. The tight-wrapping mantle thus becomes an attribute of a boy who is the object of the male gaze and male desire. In the tondo of the Antiphon Painter cup, however, the boy is alone. There is no other figure in the image to incite his modesty. Combined with the personal and intimate manner in which the user of this cup would experience the image as he holds it close to his face to drink, it would appear to the drinker that it is his own gaze that provokes the boy to act out his modesty. As the drinker drains his cup and encounters the boy, the image responds with resistance to his gaze. This article examines how the user of the vase is drawn into the image on this vase and similar scenes as he uses the vase and experiences the image.

Figure 1.

Interior of a kylix attributed to the Antiphon Painter. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum B11. Photo courtesy the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum. Used by permission. 490–80 BCE.

Figure 2.

Exterior of Figure 1. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum B11. Photo courtesy the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum. Used by permission. 490–80 BCE.

2. Background: Courtship Scenes

Courtship scenes between men and boys are a common motif on Attic vases and make up the vast majority of images related to pederasty, the conventional and institutionalized relationships between adult men and pubescent boys in ancient Greece (Dover 2016, pp. 4–9; Lear and Cantarella 2008, p. 38). “Courtship” is something of a euphemism, but the images themselves are visual euphemisms, depicting ideals rather than realities. In Classical Athens, such relationships between men and boys were considered mutually beneficial to both partners. In this view, the younger partner, called the erômenos (literally the “beloved”), usually in his early adolescence, gained a role model and instruction on proper male behavior. The older partner, called the erastês (or literally the “lover”), would be inspired to earn the admiration of his beloved through setting a good example, as well as the physical aspects that came along with the relationship (Dover 2016, pp. 52–54; Lear and Cantarella 2008, pp. 2–3). The Greek verb eraô from which these terms derive refers more to physical, erotic desire than love in the modern sense, so “lover” is not a completely accurate translation of erastês, but will have to suffice (Bloch 2001, p. 185).

Images of pederastic couples have been studied extensively for what they may reveal about ancient Greek sexuality and the institution of pederasty in Athens.2 Courting scenes often involve the older partner presenting gifts to the object of his affection, who may react reticently (Kilmer 1993, pp. 11–15). An even larger corpus of images does not depict the institutionalized relationships between men and boys, but may be considered more broadly erotic. These include images of young, nude athletes and the like. Given the context for which these images were produced—the symposion, where the viewership was exclusively adult and male—these images clearly cater to a viewership of erastai (Lear and Cantarella 2008, p. 38).

In general, pederastic erotic imagery on Attic vases—including courting scenes—is subtler than heterosexual erotic scenes. Attic vase-painters showed explicit sex between men and women in all possible combinations and permutations, often shaded with sexual violence. Though the activities depicted are not beyond the realm of possibility, they represent exaggerated fantasies—pornography prima facie. Group orgies and the abuse of women celebrate the homosocial bonds central to ancient Greek society and reaffirm the hegemony of citizen males over “others” (Stewart 1997 pp. 156–64). Erotic scenes between males “show less than the reality, not more” (Shapiro 1992, pp. 55–57). Other than mythological pursuit scenes featuring a male divinity pursuing a boy, pederastic imagery on Attic vases exhibits a restraint and even tenderness not found in heterosexual scenes (Uzzi 2015, p. 207).

It is often repeated that to be the passive or receptive sexual partner was considered an inherently demeaning position in ancient Greece, and thus not something acceptable for citizen males (Dover 2016, pp. 100–9), though the reality was certainly more complicated (Davidson 2001). Erastês and erômenos are sometimes shown intertwined, with the man fondling his younger partner, but rarely are the images any more explicit (Kilmer 1993, p. 11). In black-figure, there are scenes of intercrural intercourse, and other scenes of erastês and erômenos wrapped within the same cloak, but these iconographic themes are rather rare in red-figure (Dover 2016, pp. 98–99; Kilmer 1997). Like many non-mythological scenes or scenes of “daily life”, heterosexual and homosexual relationships as depicted were likely not consistent with reality. The images tell us more about how Athenians wished to be seen rather than the truth of social life (Shapiro 1992, p. 58; Stewart 1997, p. 157). Vase-painters’ general avoidance of explicit scenes of homosexual sex is likely reflective of the complicated and even problematic nature of pederastic partnerships, rather than a reflection of reality.

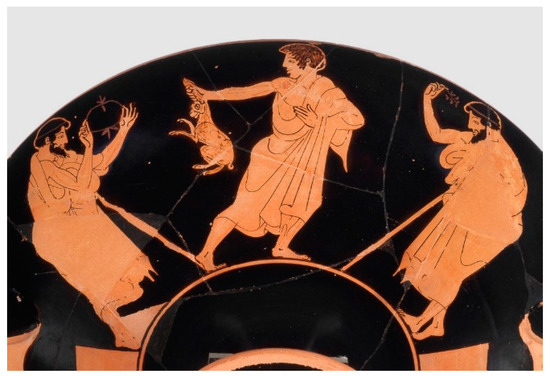

Of the red-figure images usually labeled “pederastic”, scenes of erastai presenting gifts to the objects of their desire are the most common. Gift-giving scenes are quite popular, especially in the early fifth century. These scenes usually show erômenoi at least partially clothed and in many courtship scenes, the younger partner is fully, even self-consciously enveloped in his clothing. An erastês on a kylix by Douris brings the object of his affection a favorite gift for erômenoi—a hare (Figure 3).3 The younger figure stands to the right, his cloak pulled up over his head with his arms tucked inside, fully enveloping his body. The older, bearded figure to the left leans on his walking stick, holding the hare behind him while looking down at the boy’s body. A sponge and aryballos hanging in the background to the right set the scene in the gymnasium, an appropriately all-male setting. Both figures are idealized in this image. The boy acts appropriately modest by covering himself and lowering his gaze; while the older figure leans on his stick, “symbolizing the leisureliness of courtship and hence also the leisure of a gentleman” (Lear 2015, p. 122). Similar scenes are numerous in this period, but painters avoid being overly repetitive. Other common love gifts include roosters, astragaloi (knucklebones used as dice), sprigs, and fillets.

Figure 3.

Interior of a kylix attributed to Douris. Würzburg, Martin von Wagner Museum 482. © Martin von Wagner Museum der Universität Würzburg. Photograph by P. Neckermann. Used by permission. 480–70 BCE.

Courting scenes are most often found on vase shapes associated with the symposion, a gathering where men would drink, discuss art and politics, and take part in revelries of varying intensity. Kylikes—wide, shallow drinking cups with handles on each side and a stemmed foot—are especially associated with wine and the symposion and are popular vehicles for pederastic iconography. The interior of a kylix offers a unique presentation, as the image in the interior would only be visible to the drinker who would encounter the scene after he drained his cup and then again and again after each cup of wine. The scenes were experienced in a much more personal and intimate manner than most vase imagery, and most art for that matter. The bowl of the Antiphon Painter cup is 24 cm in diameter. As the drinker holds the cup to his mouth, it envelopes his full field of vision and cuts him off from his physical surroundings. The black field surrounding the tondo image frames and focuses attention on the lone boy and further lends to the beholder’s absorption in the image (Grethlein 2017, p. 191). When the drinker-viewer encounters an erotic image inside his kylix that no one else in the room can see, he can have an individual experience of it, unlike most other aspects of the symposion. As the symposion was fundamentally an all-male institution and the kylix was a shape made specifically for the symposion, it is no surprise that the imagery on these vases was tailored specially to male viewers. Scenes of athletics, war, and other masculine pursuits are also very common on kylikes and other symposion vessels, and scenes of pederastic courting and images of beautiful boys fit into this milieu.

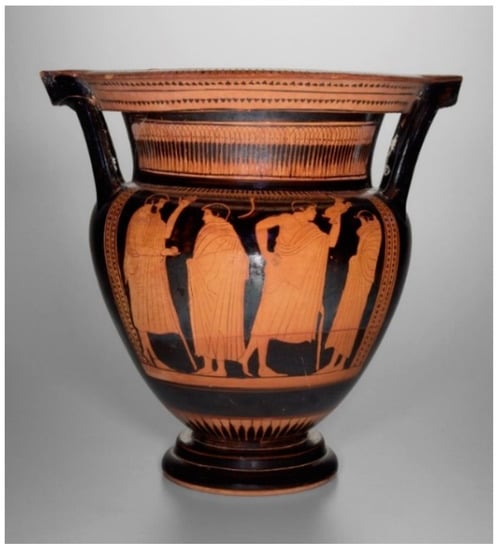

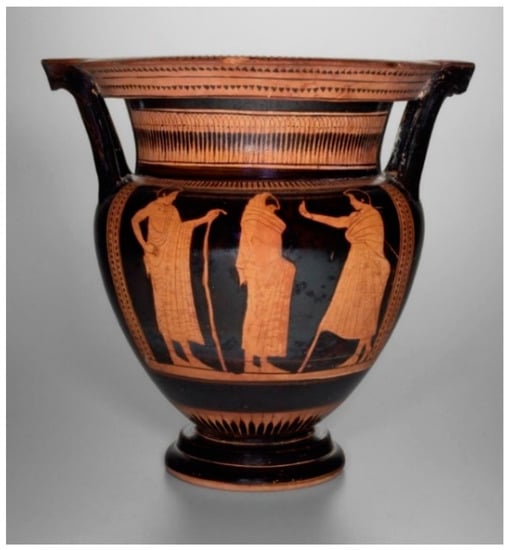

Pederastic scenes are found on other shapes as well, especially kraters and other symposion shapes. On a krater in New Haven attributed to the Agrigento Painter (Figure 4 and Figure 5), the scene on what is normally identified as the front of the vase (Figure 4) shows two pairs of erastai and erômenoi.4 The erastês in the left pair offers a gift of an apple, while the erastês to the right offers a hare. Neither erômenos is eager to accept his gift, and both are fully covered. The boy to the far right hides the lower half of his face in his garment. The strigil hanging in the background again sets the scene in the gymnasium. The reverse of the vase (Figure 5) shows three figures in what is often taken as a generic scene of conversation in the palaestra (Ferrari 2002, p. 72). Paired with the scene on the other side, the figure at center wrapped in his cloak, his face half-hidden, is clearly the object of desire of the other two young men in the scene (Lear 2015, p. 128). The figures flanking him are both beardless, so not sufficiently differentiated in age to be proper erastai; but even outside of the bounds of institutionalized pederastic relationships, there is a dynamic between the two outer figures and the youth at center that prompts him to cover himself. Generic conversation scenes like this, as well as other scenes with erotic undertones, continue into the fourth century, well after overtly pederastic imagery disappears from Attic vase-painting.

Figure 4.

Obverse of a krater attributed to the Agrigento Painter. New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery 1933.175. Photo courtesy Yale University Art Gallery. https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/5658. In the public domain. 475-450 BCE.

Figure 5.

Reverse of Figure 4. New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery 1933.175. Photo courtesy Yale University Art Gallery. https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/5658. In the public domain. 475-450 BCE.

Wrapped youths are also found in non-erotic scenes without overt or implied sexual content. They stand before altars,5 hold offerings,6 and grieve at tombs.7 Women are also often shown wrapped, both while being courted and in non-erotic settings.8 The tight-wrapping cloak is nonetheless an attribute of aidôs in these scenes. Aidôs—a term discussed further below—encompasses ideas of honor and respect appropriate to religious ritual and to women who recognize their place in the social hierarchy (Ferrari 2002, pp. 72–86).

A lowered, averted glance is typical of boys being courted as well as chaste girls and brides (Ferrari 2002, p. 79; Shapiro 1992, p. 63). Girls and erômenoi bore similar expectations of modesty, and there was a common verbal and visual vocabulary of beauty for both. The same display of aidôs against the male gaze was fitting for both (Ferrari 2002, pp. 91–92). Boys and girls were also similarly praised as kalos/kalê. The demarcation between erastês and erômenos and between male and female likely involved a complicated negotiation of roles and was a potential source of some discomfort for symposiasts (Glazebrook 2015; Shapiro 1992, p. 63).

3. Masculine Beauty

There are a great number of images on Attic vases that celebrate male beauty. The ancient Greek ideal of masculine beauty includes “broad shoulders, a deep chest, big pectoral muscles, big muscles above the hips, a slim waist, jutting buttocks and stout thighs and calves” (Dover 2016, p. 70). Aristotle (1926), in his Rhetoric, describes the masculine physical ideal as being “good in bodily excellences, such as stature, beauty, strength, [and] fitness for athletic contests” (1361a). There is no difficulty in finding subtly erotic images of such beautiful boys on Attic vases. The interior of a cup by the Kiss Painter is a much-cited example (Figure 6).9 A nude boy stands on a two-stepped platform holding a javelin, wearing a leaf crown. The podium, crown, and athletic nudity mark the boy as the victor in an athletic contest. The scene is set in the gymnasium, based on the sponge and aryballos hanging in the background. The boy holds another sponge and aryballos in his left hand. At the bottom of the tondo, there is a pick used for leveling sand in the long jump pit, also lending to the athletic setting (Williams 1984, pp. 145–46, no. 105). Another figure, an older man, stands to the left, taking in the spectacle of the victorious boy. He looks to the boy in admiration for his athletic victory, and at the same time likely views the boy as an object of erotic desire.

Figure 6.

Kylix attributed to the Kiss Painter. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum B5. Photo courtesy the Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum. Used by permission. 500 BCE.

The two figures are clearly distinguished in age, not purely by size, but also by facial hair. Beginning to grow a beard was an important mark of passage from youth into manhood in ancient Greece. It was considered inappropriate to continue a relationship once the younger partner had begun to grow a beard (Dover 2016, p. 86). These two would be quite the right ages to be partners in a pederastic relationship. Around the edge of the tondo, an inscription reads “Leagros kalos”, “Leagros is beautiful”. Inscriptions like this, praising either a young man or just a boy as beautiful (as on the Antiphon Painter cup cited above), are very common on Athenian vases, and Leagros is by far the most frequently-named man. It is probably incorrect to say that one of these figures is supposed to represent Leagros, but the inscription echoes the admiration of the man for the boy.

Athletic nudity was the norm in ancient Greece, but could nonetheless contribute to an image’s erotic effect. The image on this vase is both exciting to the viewer and user of the vase and represents a figure experiencing similar excitement, but in many other images—such as the Antiphon Painter cup and others to be discussed below—eroticism and desire are latent.

By covering himself, the erômenos acts out his aidôs—a term that can be translated as modesty, respect, honor, or even shame. It was considered unbecoming for a boy to give in to the advances of an older partner too quickly or easily or to display affection toward his older partner (Plato, Symposium 182a–183d; Lear and Cantarella 2008, p. 9; Stewart 1997, pp. 14–15). Appropriately, we often find boys in courtship scenes wrapping themselves tightly in their mantles, rather than eagerly accepting gifts or other advances from a suitor. This aidôs engendered the boy’s beauty as much as his physical appearance. Modesty was necessitated and provoked by the eroticizing gaze of a potential suitor. The tight-wrapping mantle of the erômenoi in the courting scenes discussed previously is thus an attribute of a person as an object of desire, a physical manifestation of the figure’s aidôs (Ferrari 2002, pp. 72–86). More than just a symbol of modesty, the enveloping and hiding of the body is an acting out of aidôs (Lear and Cantarella 2008, p. 40). This aidôs is elicited by the self-consciousness of the erômenos, by his awareness of the gaze of another, of being looked at as an object and being judged.

4. Aidôs and the Gaze

The gaze, in theoretical parlance, issues from the “Other” and represents one polarity of the scopic field, counterposed with the glance, which emanates from the self (Lacan 1978, pp. 67–119 [§ 6–9]; Sartre 1956, pp. 254–302 [pt. 3, ch. 1, § 4]). The gaze is not seen but exists as an undetermined Other (Jay 1993, pp. 361–62). The Other is not the erastês, as he is clearly seen by the erômenos, but rather others who might see his reaction to gifts and judge his response too enthusiastic as to be becoming of a young citizen. Ancient Greece was in many ways a shame culture in which praise or blame was based on conformity of conduct with normative expectation (Stewart 1997, pp. 13–14). Being conscious of being looked at causes shame and anxiety; it causes one to look away and adapt behavior. To feel shame requires “an Other” whose appearance provokes one to pass judgment on oneself as an object (Sartre 1956, pp. 221–23 [pt. 3, ch. 1, § 1]). To quote Sartre via Andrew Stewart (1997, p. 13), “To put on clothes is to hide one’s object-state; it is to claim the right of seeing without being seen; that is, to be pure subject” (Sartre 1956, p. 289 [pt. 3, ch. 1, § 4]). Modesty—aidôs—requires a subject–object relationship, an active–passive power dynamic where roles and expectations are clearly defined. The symposiast’s gaze is the male gaze par excellence, as sexual relations in ancient Athens are usually understood in terms of active and passive roles. The citizen male had a range of available and socially acceptable sexual pairings, with him as the active player and the passive recipient a woman, younger male, or enslaved individual of any age or sex (Lear and Cantarella 2008, p. 2).

Returning to the Antiphon Painter cup discussed above, in the tondo image (Figure 1), there is no older man or other suitor depicted to rouse this young man’s modesty. Nevertheless, the boy covers himself in the same way as the boy on the exterior of the cup (Figure 2) and erômenoi in the other scenes described above. The aidôs-inducing gaze comes from an unseen source. We could imagine this lone figure as an excerpt from a larger gymnasium scene, but keeping in mind that cups like this one were made for use at the symposion where men, usually older men, would gather, I suggest that the gaze inspiring the modesty of this young man comes from the user of the cup. The interior image of a cup—the boy—would fall only within and completely envelope the drinker’s field of vision as he held it up to his mouth to drink. The drinker would see the boy in the same way he saw boys he might court in real life. The format lends to the beholder’s absorption within the scene, while the reaction by the erômenos to his gaze distances him from the image (Grethlein 2017, pp. 191–92). Norman Bryson (1988, p. 100) has criticized Sartre’s conception of the gaze as creating a tunnel vision between subject and object. In this instance, however, the tunnel vision is real for the moment when nothing exists except the image inside the cup and the potentially-inebriated viewer.

This same visual play is found on other red-figure kylikes, often paired with an inscription citing the boy’s beauty and attributes placing the scene in a men’s space like the gymnasium. On a vase in Munich attributed to Makron, the erotic connotations of the interior (Figure 7) are strengthened by the overtly erotic courting scenes on the exterior (Figure 8).10 Each side shows a beardless youth between two older men. On the better-preserved side (Figure 8), a beardless youth holds a hare toward the man to the left. This is presumably a gift he has just received from a potential erastês. The man to the left offers him a fillet and the man to the right offers a sprig, other typical love gifts. The other side depicts a similar scene but is more fragmentary. The youth is in a similar pose of moving to the right while looking back to the left. Each of these youths is partially covered, not exposed but not exhibiting any obvious modesty. The interior (Figure 7) shows a single beardless youth, wrapped up to his neck with his arms inside his himation. His pose is reminiscent of the two youths on the exterior, moving to the left while looking to the right, as if caught off-guard. His glance back over his shoulder seems to betray his self-consciousness at being watched. The bag suspended in the background to the left holds knucklebones, a reference to courting gifts.

Figure 7.

Interior of a kylix attributed to Makron. Munich, Antikensammlungen 2658. Photo courtesy Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek München. Photograph by Renate Kühling. Used by permission. 480/70 BCE.

Figure 8.

Interior of Figure 7. Munich, Antikensammlungen 2658. Photo courtesy Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek München. Photograph by Renate Kühling. Used by permission. 480/70 BCE.

On some vases, a single, wrapped boy in the tondo of a cup is shown standing near a turning post, thus setting the scene in the gymnasium or in a stadium, or other appropriately male-oriented locations. A cup in Bologna attributed to the Curtius Painter also has a sponge and aryballos hanging in the background.11 This is a somewhat idiosyncratic combination of objects used to mark a certain setting, but they both place the image against a background of exercise, male nudity, and the male gaze. A cup attributed to the Ancona Painter12 and another compared to his style13 also show individual, wrapped boys alongside turning posts. On the cup in Eichenzell, the painter has included nonsense inscriptions on the post and in the field to the left of the figure, recalling the kalos inscriptions frequently found on courting scenes. The boy bends down to read the inscriptions on the post, scrutinizing the letters while being scrutinized by the user of the cup.

A kylix in Paris attributed to the Tarquinia Painter shows a boy in a very similar pose, this time examining a herm (Figure 9).14 The boy crouches down with his himation pulled up over his head and gripped tightly in his hand in front of him. The herm is shorter than the boy, so that its eyes appear to stare at his covered body, but the boy does not react to the gaze of the herm. He seems to approach the herm as an object rather than a person. There is some obvious humor here. The boy encounters a figure consisting of little more than a face and a phallus. Perhaps the drinker would envy the herm, who, even though lacking limbs, is fully equipped to engage with an erômenos.

Figure 9.

Interior of a fragmentary kylix attributed to the Tarquinia Painter. Paris, Musée du Louvre Cp11753. Photo by Hervé Lewandowski © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY. Used by permission. Ca. 470 BCE.

As on the Antiphon Painter cup, lone, wrapped boys are sometimes accompanied by inscriptions echoing the likely sentiments of the viewer. A cup in Amsterdam has a boy making a speaking gesture, with a sponge and aryballos behind him and “ho pais kalos” inscribed above.15 Another vase by Douris shows a draped boy moving to the left with an aulos case hanging in the background and the inscription “kalos ho pais” above.16

5. Chronological and Geographic Contexts

Pederastic courting scenes first appeared in Attic vase-painting around 560 BCE. They reached the height of their popularity in the last quarter of the sixth century and declined sharply after 500. By the 470s, only a handful were produced (Shapiro 1981, pp. 133–34). The height of popularity and ultimate decline of pederastic iconography coincided with the peak and decline of the black-figure technique. Accordingly, courting scenes are much more common in black-figure than red-figure. There are several changes in pederastic iconography between black- and red-figure as well (Kilmer 1997). In red-figure, erastai and erômenoi appear nude less often than in earlier black-figure scenes, and there is often a less obvious difference in age between the two (Lear and Cantarella 2008, pp. 63–67). As with red-figure iconography generally, pederastic scenes are sometimes intentionally ambiguous. Red-figure painters often played upon the inherent tensions and ambiguities that images on vases present (Neer 2002). The images on the Antiphon Painter vase described above certainly exploit the tensions between viewer and image and absorption in and distance from the image (Grethlein 2017, pp. 241–44). Comparable images are found in the early fifth century, mostly on vases made for the symposion.

The vases discussed here all date to the early decades of the fifth century. By 470, explicitly erotic scenes as well as courting scenes were quite rare (Shapiro 1981, p. 143). Earlier, black-figure courting scenes often show the erômenos nude, and never modestly draped as on the red-figure scenes discussed above. The tightly-wrapped erômenos is introduced in red-figure of the early fifth century, at a time when pederastic scenes were becoming much less common. The wrapped erômenos represents a transition in erotic imagery. Painters moved away from explicit sexual imagery and explored subtler ways of depicting complicated sexual relations. This is likely a reflection of the evolving social life of the time under the developing democracy, as the egalitarianism (between free, citizen males) central to Athenian democracy demanded citizens “display self-control through rational regulation of pleasures” (Skinner 2014, p. 133).

Several explanations have been offered for the decline of pederastic imagery and the putative decline in pederasty in practice during the early Classical period. Based on literary evidence of the late fifth century, it seems public approval of pederastic relationships had waned. Though vase imagery seems to suggest pederasty in Athens declined after 470, Andrew Lear argues that the practice was partially problematized through most of the sixth and into the fifth centuries, only to become fully or hyper-problematized in the late fifth or early fourth century. The problematization of pederastic relationships found in the words of Socrates and Aristophanes represents contemporary questioning of the practice (Lear 2015, pp. 127–28). Stewart (1997, p. 171) suggests the decline in courting and sex scenes in the Classical period is the result of the rise of the ethic of sophrosyne, which encompasses self-control, austerity, and sexual morality, ultimately leading to the fourth-century ideal of eukrateia, or internal control.

While unambiguous sex scenes between men and boys practically disappeared in the early Classical period, subtler erotic scenes featuring boys continued, as did the generic “conversation on the palaestra scenes”, which may often be read with pederastic undertones, as in the case of the Agrigento Painter’s vase discussed above (Figure 5). The image on the Antiphon Painter vase and the other, similar scenes discussed here fall into a category that can be described as “understated courting scenes”. These are images that include figures that might be interpreted as an erastês-erômenos pair, with or without other attributes pointing to a pederastic relationship, but leaving a certain ambiguity and emphasizing “the expected behavior of a potential erômenos: to flee his lovers, refuse payment, and not become sexually aroused” (Joyce 1995, p. 12).

Several scholars have noted that Hellenistic art often relies on a particular manner of viewing that requires the viewer to supplement unexpressed details and extrapolate from visual clues (Von Blanckenhagen 1975; Zanker 2004). Graham Zanker has expanded this idea to show how Hellenistic sculptures integrate the viewer into the work. His examples rely on the sculpted figure, usually on the same plane as the viewer, meeting their gaze. Examples from ekphrastic literature also rely on the viewer meeting eyes with a figure looking out from the image to encroach on the viewer’s personal space (Zanker 2004, pp. 103–6). Though there is a significant span of time between the vases described above and the artworks Zanker discusses, the “understated courting scenes” by the Antiphon Painter and his contemporaries exploit similar strategies of viewer integration, and in even more complex ways than Zanker’s examples. Frontal-facing figures who look out toward the viewer are uncommon in Attic vase-painting. In courtship scenes, occasionally one figure is shown frontally (Frontisi-Ducroux 1996, p. 85). Lone, wrapped boys do not look out of the image to the drinker, but this is all the more appropriate to them. In more unambiguous pederastic courting scenes, the erômenos usually looks down or, if a gift is being given, at the gift, rather than into the eyes of the erastês. His glance is not confrontational. Frontisi-Ducroux (1996, p. 83) compares this to the nodding consent elicited from sacrificial victims before the killing blow. A one-way, unequal gaze/glance indicates an unequal relationship (Ferrari 2002, p. 79; Frontisi-Ducroux 1996, p. 85). The viewer is integrated into these scenes as the clearly dominant figure. The image does not encroach on his personal space; conversely, he intrudes upon the boy in his cup.

Most of the vases discussed heretofore, and for that matter, most Attic vases with pederastic iconography, were found in Italy and in particular at Etruscan sites (Bundrick 2019, pp. 52–53; Lear and Cantarella 2008, p. 71). It has long been assumed that the imagery of Attic vases was made with Athenian viewers and Athenian tastes in mind. This is supposed either because of the peculiarly Athenian iconography of some vases or, as John Boardman put it, because the “Etruscans were a rich but artistically immature and impoverished people, and they became ready and receptive customers for anything exotic…” (Boardman 1999, p. 199). In a view less dismissive of Etruscan tastes, Richard Neer (2002, p. 9) sees that Attic vases’ “exotic Hellenism seems to have been part of their value to Etruscan and other ‘barbarian’ consumers”. However, vases with explicitly erotic imagery, both heterosexual and homosexual, are all but unknown in archaeological contexts in mainland Greece (Lynch 2009). Sheramy Bundrick has recently shown that Attic vases in Etruscan tombs represent deliberate, cohesive assemblages, indicating that their iconography was meaningful to their end users (Bundrick 2019, pp. 51–92). We should, perhaps, reconsider these images with Etruscan viewers in mind. The sort of institutionalized pederastic relationships often discussed in relation to courting scenes would not likely mean much to an Etruscan viewer, but considering the images as more generally erotic, they fit well into the types of imagery these viewers preferred (Lynch 2017). The majority of surviving Attic vases with erotic scenes featuring both same sex and opposite sex couplings have been found in Etruscan contexts, and Etruscan funerary art often included implicit or explicit erotic scenes. For instance, the Tomb of the Bulls at Tarquinia features sex scenes with both heterosexual and homosexual groupings (Bundrick 2019, p. 54, Figure 3.2–3). Even outside of the social context of Athenian pederastic relationships, the imagery of the vases discussed here functions as a self-contained erotic iconography that clearly appealed to Etruscan consumers.

6. Conclusions

Because they are painted on functional objects meant to be viewed in dynamic contexts of use and meaning, the pictures on Attic vases often play upon the tension between images and their material supports and allowed painters to exploit the multiple and often incongruent perspectives from which one vase may be viewed by several individuals in a single instance. Kylikes in particular often carry images related to a specific social setting—the symposion—that are intended to be viewed from a particular, physical perspective. An image on the interior of a kylix is only visible to the user of the cup as he raises it to drink. The image completely envelopes the drinker’s field of vision and creates an intimate and personal experience of the picture that is not shared with the other participants in the symposion, who would at the same time experience an entirely different view of the exterior of the vase.

Many pederastic courting scenes and more general erotic scenes show boys and youths in various states of undress. The tightly-wrapped erômenos is by no means the standard or even one of the more common iconographic types. The enveloped, concealed figure presented an opportunity for vase-painters to play on the ambiguities present in the symposion and to create erotic imagery with a broad appeal in Greece and abroad. The boy at the bottom of the Antiphon Painter cup is attractive for what he does not show, and he reacts to the gaze that is not shown. Though at first glance rather banal, these pictures look deliberately outward and declare themselves to an anticipated viewer. The viewer’s interaction with the image is as important to its function as any element within the picture. The image reacts to the drinker’s gaze and makes him an actor in the scene.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

A version of this paper was presented at the College Art Association annual conference in New York in February 2019. Alan Shapiro and Carolyn Laferrière provided much helpful discussion and many valuable suggestions. I am also grateful to Sanchita Balachandran for examining and discussing the vases in Baltimore with me on many occasions and to Laura Garofalo for helping me to locate important bibliography.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Aristotle. 1926. Art of Rhetoric. Translated by John Henry Freese. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, Available online: http://data.perseus.org/texts/urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0086.tlg038.perseus-eng1 (accessed on 21 February 2019).

- BAPD (Beazley Archive Pottery Database). n.d. Available online: www.beazley.ox.ac.uk (accessed on 21 February 2019).

- Beazley, John D. 1963. Attic Red-figure Vase-Painters, 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, Enid. 2001. Sex between Men and Boys in Classical Greece: Was It Education for Citizenship or Child Abuse? Journal of Men’s Studies 9: 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, John. 1999. The Greeks Overseas: Their Early Colonies and Trade, 4th ed. London and New York: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, Norman. 1988. The Gaze in the Expanded Field. In Vision and Visuality. Edited by Hal Foster. Seattle: Bay Press, pp. 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bundrick, Sheramy D. 2019. Athens, Etruria, and the Many Lives of Greek Figured Pottery. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, James. 2001. Dover, Foucault and Greek Homosexuality: Penetration and the Truth of Sex. Past & Present 170: 3–51. [Google Scholar]

- Dover, Kenneth. 2016. Greek Homosexuality, 3rd ed. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, Gloria. 2002. Figures of Speech: Men and Maidens in Ancient Greece. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frontisi-Ducroux, Françoise. 1996. Eros, Desire, and the Gaze. In Sexuality in Ancient Art: Near East, Egypt, Greece, and Italy. Edited by Natalie Boymel Kampden. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook, Allison. 2015. “Sex Ed” at the Archaic Symposium: Prostitutes, Boys, and Paideia. In Sex in Antiquity: Exploring Gender and Sexuality in the Ancient World. Edited by Mark Masterson, Nancy Sorkin Rabinowitz and James Robson. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 157–78. [Google Scholar]

- Grethlein, Jonas. 2017. Aesthetic Experiences and Classical Antiquity: The Significance of Form in Narratives and Pictures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jay, Martin. 1993. Downcast Eyes: The Denigration of Vision in Twentieth-century French Thought. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, Colin. 1995. Red-figure Column-krater. In Mother City and Colony: Classical Athenian and South Italian Vases in New Zealand and Australia. Edited by Beth Cohen and H. A. Shapiro. Christchurch: University of Canterbury, pp. 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kilmer, Martin F. 1993. Greek Erotica on Attic Red-figure Vases. London: Duckworth. [Google Scholar]

- Kilmer, Martin F. 1997. Painters and Pederasts: Ancient Art, Sexuality, and Social History. In Inventing Ancient Culture: Historicism, Periodization, and the Ancient World. Edited by Mark Golden and Peter Toohey. London: Routledge, pp. 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lacan, Jacques. 1978. The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis. Edited by Jacques-Alain Miller. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York and London: W. W. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Lear, Andrew. 2015. Was Pederasty Problematized? A Diachronic View. In Sex in Antiquity: Exploring Gender and Sexuality in the Ancient World. Edited by Mark Masterson, Nancy Sorkin Rabinowitz and James Robson. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 115–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lear, Andrew, and Eva Cantarella. 2008. Images of Ancient Greek Pederasty: Boys Were Their Gods. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, Kathleen M. 2009. Erotic Images on Attic Vases: Markets and Meanings. In Athenian Potters and Painters, Volume II. Edited by John H. Oakley and Olga Palagia. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 158–64. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, Kathleen M. 2017. Reception, Intention, and Attic Vases. In Theoretical Approaches to the Archaeology of Ancient Greece: Manipulating Material Culture. Edited by Lisa C. Nevett. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 124–42. [Google Scholar]

- Neer, Richard T. 2002. Style and Politics in Athenian Vase-Painting: The Craft of Democracy, ca. 530–460 B.C.E. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sartre, Jean-Paul. 1956. Being and Nothingness. Translated by Hazel E. Barnes. New York: Philosophical Library. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, H. Alan. 1981. Courtship Scenes in Attic Vase-painting. American Journal of Archaeology 85: 133–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, H. Alan. 1992. Eros in Love: Pederasty and Pornography in Greece. In Pornography and Representation in Greece and Rome. Edited by Amy Richlin. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, Marilyn. 2014. Sexuality in Ancient Greek and Roman Culture, 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Andrew F. 1997. Art, Desire, and the Body in Ancient Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Uzzi, Jeannine Diddle. 2015. The Age of Consent: Children and Sexuality in Ancient Greece and Rome. In The Archaeology of Childhood: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on an Archaeological Enigma. Edited by Güner Coşkunsu. Albany: SUNY Press, pp. 251–74. [Google Scholar]

- Von Blanckenhagen, Peter H. 1975. Der ergänzende Betrachter: Bemerkungen zu einem Aspekt hellenistischer Kunst. In Wandlungen. Studien zur antiken und neueren Kunst. Ernst Homann-Wedeking gewidmet. Edited by Institut für Klassische Archäologie der Universität München. Waldsassen-Bayern: Stiftland, pp. 193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Ellen Reeder. 1984. The Archaeological Collection of the Johns Hopkins University. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zanker, Graham. 2004. Modes of Viewing in Hellenistic Poetry and Art. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum B11; ARV2 340.65; BAPD 203498. (ARV2 Beazley 1963). |

| 2 | For an overview of scholarship, see (Kilmer 1997; Lear 2015). |

| 3 | Würzburg, Martin von Wagner Museum 482; ARV2 444.239; BAPD 205287. (BAPD n.d.). |

| 4 | New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery 1933.175; ARV2 576.45; BAPD 206646. |

| 5 | For example: Paris, Musée du Louvre Cp11770; ARV2 875.15; BAPD 211548; www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/record/DFA4A45F-06DF-46E5-9689-4029CBB559B1. |

| 6 | Bologna, Museo Civico Archeologico 366; ARV2 412.9; BAPD 204491; www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/record/D32B5ABB-6A54-4B05-8AB6-86E27BCB9532. |

| 7 | Athens, Acropolis Museum 6473; BAPD 8940; www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/record/23752A46-6CD9-493F-925A-41E4250C7B79. |

| 8 | Paris, Louvre G143; ARV2 469.148; BAPD 204830; www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/record/392BCE9E-4C9A-4F32-9DF4-A8509B285BD3. |

| 9 | Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum B5; ARV2 177.3; BAPD 201626. |

| 10 | Munich, Antikensammlungen 2658; ARV2 476.275; BAPD 204954. |

| 11 | Bologna, Museo Civico Archeologico 448; ARV2 934.70; BAPD 212586; www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/record/3D767F9A-8BF3-4B03-8210-629A8A6E39E8. |

| 12 | Eichenzell, Schloss Fasanerie (Adolphseck) 134; ARV2 875.17; BAPD 211550; www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/record/60AA4C0A-BC75-4112-85B0-3F1E7024B0E4. |

| 13 | Paris, Musée du Louvre Cp117711; ARV2 875.1; BAPD 211554; www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/record/6540A5AC-5F45-47BA-87B5-5E1FE49AD9DC. |

| 14 | Paris, Musée du Louvre Cp11753; ARV2 869.59; BAPD 211453. |

| 15 | Amsterdam, Allard Pierson Museum 2262; ARV2 349; BAPD 203660; www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/record/8ADB4AB4-9435-457B-B7CC-8DF18C62532A. |

| 16 | Stockholm, Medelhavsmuseum 1960:011; ARV2 444.230bis; BAPD 205277; www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/record/32AC69AE-F6FF-47E2-B0AC-AD0BE94F7E09. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).