Abstract

The profile of students applying to BA Fine Art undergraduate programs has shifted in the United Kingdom (UK). Until recently the usual academic pathway was to proceed after A-level to a one-year Art Foundation program; this route is increasingly challenged by a sense of urgency to enter university earlier. Students more frequently enter straight from school. To accommodate the recruitment of younger applicants there are significant implications for Higher Education Fine Art pedagogy. This article reports on some of the approaches implemented at Northumbria University to support positive transition and learning within the BA Fine Art program. Using the Year 1–Level 4 Fine Art as a case study this reflects on how one university fine arts team has responded to the challenge of induction.

1. Introduction

In the university where I work the BA Fine Art program team have encountered an increase in students who struggle to cope with the demands of university life. Many arrive with anxiety and many lack self-assurance as independent learners. The impact this has on their confidence to experiment within an art school studio environment is inhibiting. They look for direction and require a high degree of structure. The observations underpinning this paper draw upon reflections that consider my personal experience of teaching. I consider the challenges of Fine Art student transition from school to Higher Education (HE) and present a qualitative, reflective account. Dialogue with peers from other institutions reveal the challenges considered are not restricted to my experiences; they are also encountered in other UK Fine Art programs. In this paper, I propose a difficult gap can exist between the classroom and university studio. The students who struggle to bridge this gap can become easily disheartened and quickly suffer lack of motivation. My intention is to reflect upon some of the challenges and consider a selection of strategies employed in the department where I work that aim to minimize or, ideally, eliminate that gap. I would not wish to suggest these present a new model, rather they explore key issues raised by my observations, reflections and conversations.

For varying reasons, not all secondary school art and design teachers focus on contemporary approaches and processes, this can present a daunting proposition for many new students who can find themselves negotiating positions of fear and distrust as they adapt to working within new frameworks of artistic pedagogy. As a result, these students can find Year 1–Level 4 Fine Art programs especially challenging. Program Teams have to work hard to nurture these young people to recognize that speculative processes, creative adventure and uncertainty are principal learning opportunities not threats. Shreeve et al. suggest the role of the tutor is to help students deal with this uncertainty and for students ‘to construct their own paths’ (Shreeve et al. 2010, p. 131). Austerlitz et al. (2008) describe this as ‘a pedagogy of ambiguity’.

Most of these students have recently completed their A-levels. We often find their adjustment to work with us as tutors (as opposed to teachers) may require additional understanding. Without this the relationship can be unbalanced and the expectations we have as tutors may be unrealistic.

In contrast, our department finds the students who enter from Foundation programs are usually better equipped. Their additional year of education provides an invaluable adjustment to a multi-faceted challenge of academic, social, cultural, environmental and personal change. Their confidence to work independently with ambiguity in the studio is, generally, much higher.

This paper draws upon departmental discussions and shared recognition that approaches need to shift. As in all HE institutions, our team constantly questions our approaches towards pedagogy. The Year 1 teaching experience presents a useful case study. This signifies the importance of creating better links between schools and universities to align understanding. Crucially, it reflects upon five key questions Fine Art teams might commonly ask in order to develop undergraduate programs to appropriately accommodate the shifting student profile and their transition to degree level learning.

- How can we support students to adjust to a new social environment?

- How do we scaffold independent learning?

- How do we equip students for collaborative learning in a Higher Education (HE) environment?

- How do we engage students with contemporary art and move them away from the security of familiar practice?

- How can we encourage students to reflect on their learning?

2. Context

The politics behind the shift in applicant profiles are complex and as the value of creative arts subjects diminish at GCSE and A-Level the number of young people continuing to study art in the UK is dwindling. Key findings of the 2016 NSEAD Survey Report reveal a significant reduction in art, craft and design learning opportunities across all key stages in primary and secondary education (NSEAD 2016). Patterns in England for GCSE and A-Level entries in the last eight years show a decline of −4% (Cultural Learning Alliance 2018) and at the start of 2019 the number of applications for Creative Arts and Design programs through the UK Universities and Colleges Admissions Services (UCAS 2016) reveal a 5% decrease (UCAS 2019). Amongst this data (UCAS 2018, 2019) there is evidence that the number of 18-years old accepted by universities has become more common. Reflecting this national trend, Fine Art applications to the university in which I work have decreased. In the past four years the number of applications from Art Foundation courses has reduced. Recurrently students apply to our university straight from school.

For the students who attend Art Foundation programs the additional year can support increased maturity and ability to confidently develop ideas and individual learning agendas. These students also have more time and opportunities to research the range of art and design courses on offer enabling more informed choices. Awareness of study options may be more limited for those applying direct from school raising the likelihood of inappropriate choices being made. For example, students may not realize their practice and interests are more suited to Decorative Arts, Illustration, Graphic or Interior Design.

An urgency to get into university fast may connect to the financial costs associated with spending an additional year in education. It is possible this also reflects school pressures to meet national targets. Sending A-Level pupils direct to university improves ‘the standing of their schools in league tables on which schools’ funding increasingly depends’ (Rutherford 2014). Alongside this, in order to retain applicants’ interest and commitment as quickly as possible university recruitment imperatives may over-ride traditional entry criteria of interview or portfolio assessments and instead accept students based only on A-level grades.

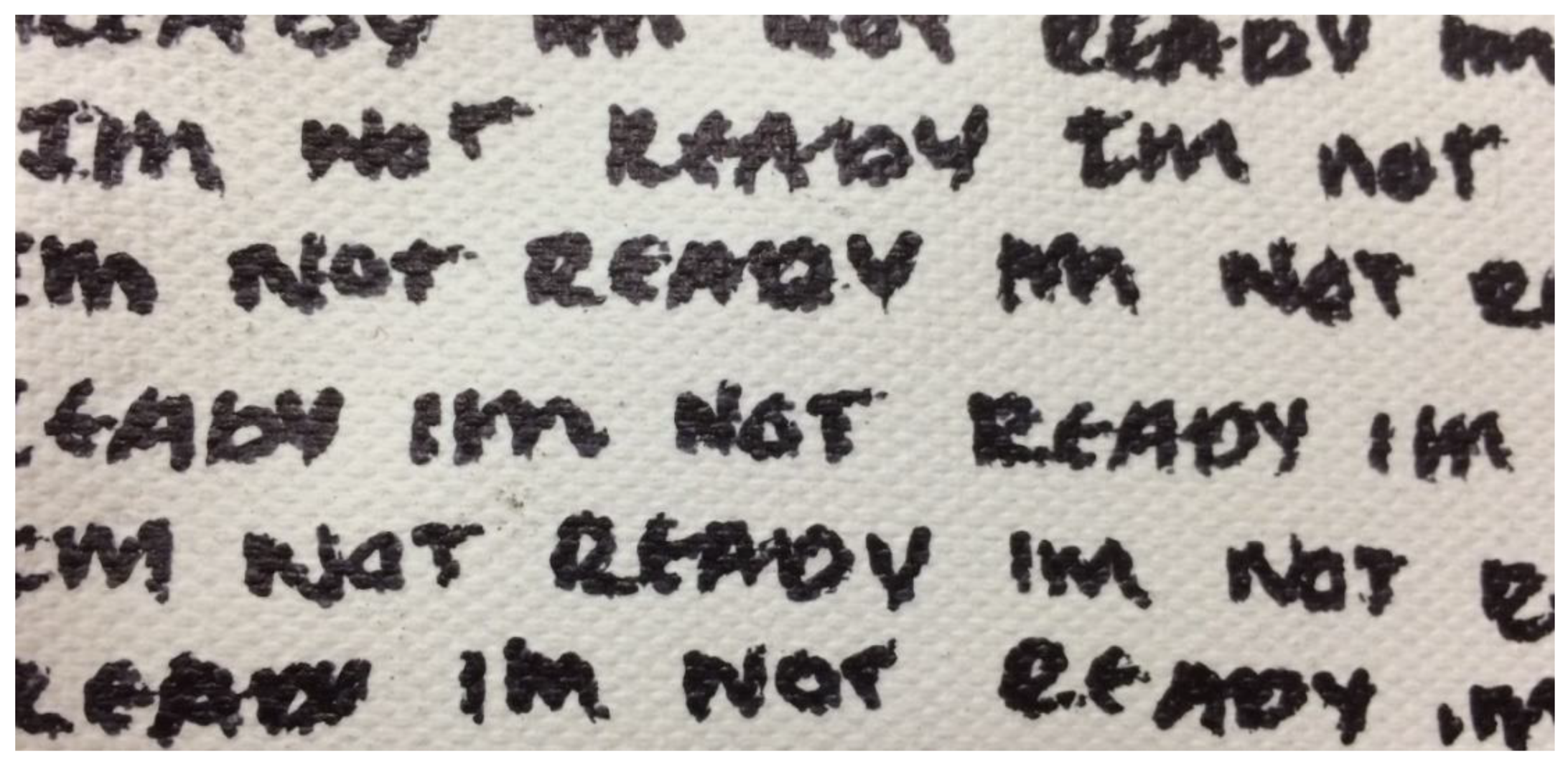

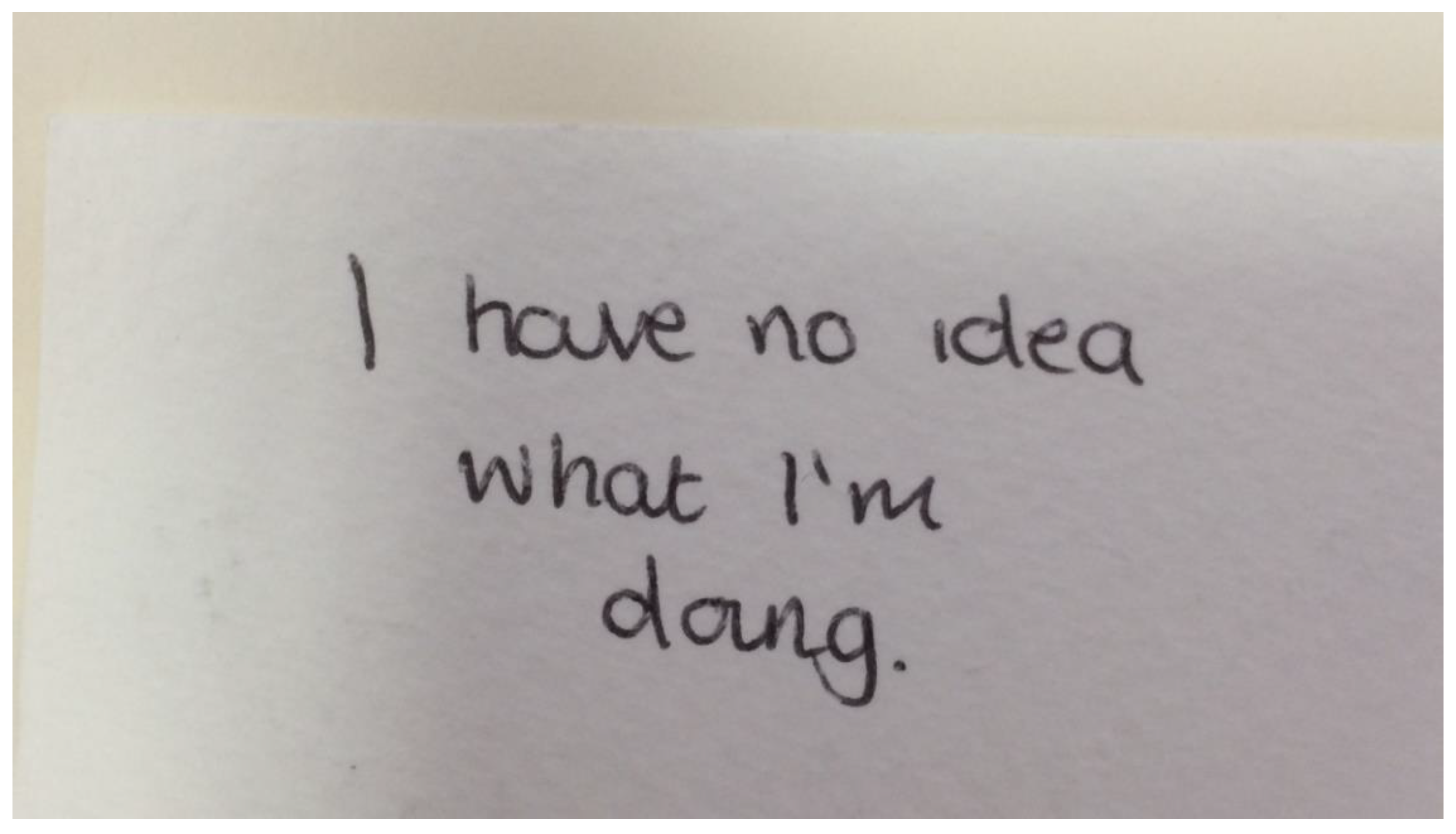

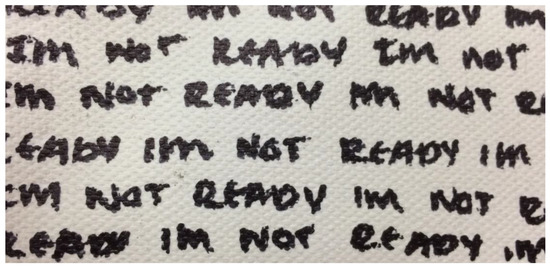

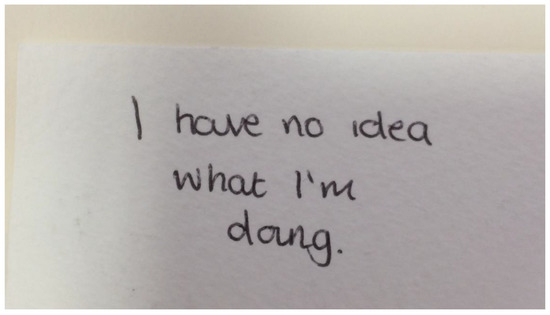

When exploring the UK Art School in the age of neoliberalism Franklin (2018) identifies conflicts between the ‘lived experience of balancing institutional, policy-driven and logistical demands with the day-to-day challenges of teaching students from a range of backgrounds, with a range of abilities, with a wide range of expectations’. As Franklin addresses, within the underpinning issues of neoliberal education there is intense pressure for attainment for students, who are also customers and universities are required to ensure maximum satisfaction. With increased fees this places more pressure on the program of study to not only satisfy the student but also to ensure they succeed. This also proves challenging, increasingly when some students apply minimal engagement, doing ‘just enough to get by’ (Rutherford 2014). The tutor’s task therefore is to successfully support individual students to recognize the investment they are making in themselves and the responsibilities they have to engage. Fine Art learning environments need to stimulate appropriate challenges that stretch individuals without deterring them when they find it difficult (as illustrated in student feedback, see Figure 1 and Figure 2). Program Teams therefore need to create positive strategies to facilitate student motivation, self-awareness and an effective ability to learn to learn with independence, confidence and commitment.

Figure 1.

Thomas, J (2016). Undergraduate student feedback.

Figure 2.

Thomas, J (2016). Undergraduate student feedback.

3. Contemporary Fine Art Practice

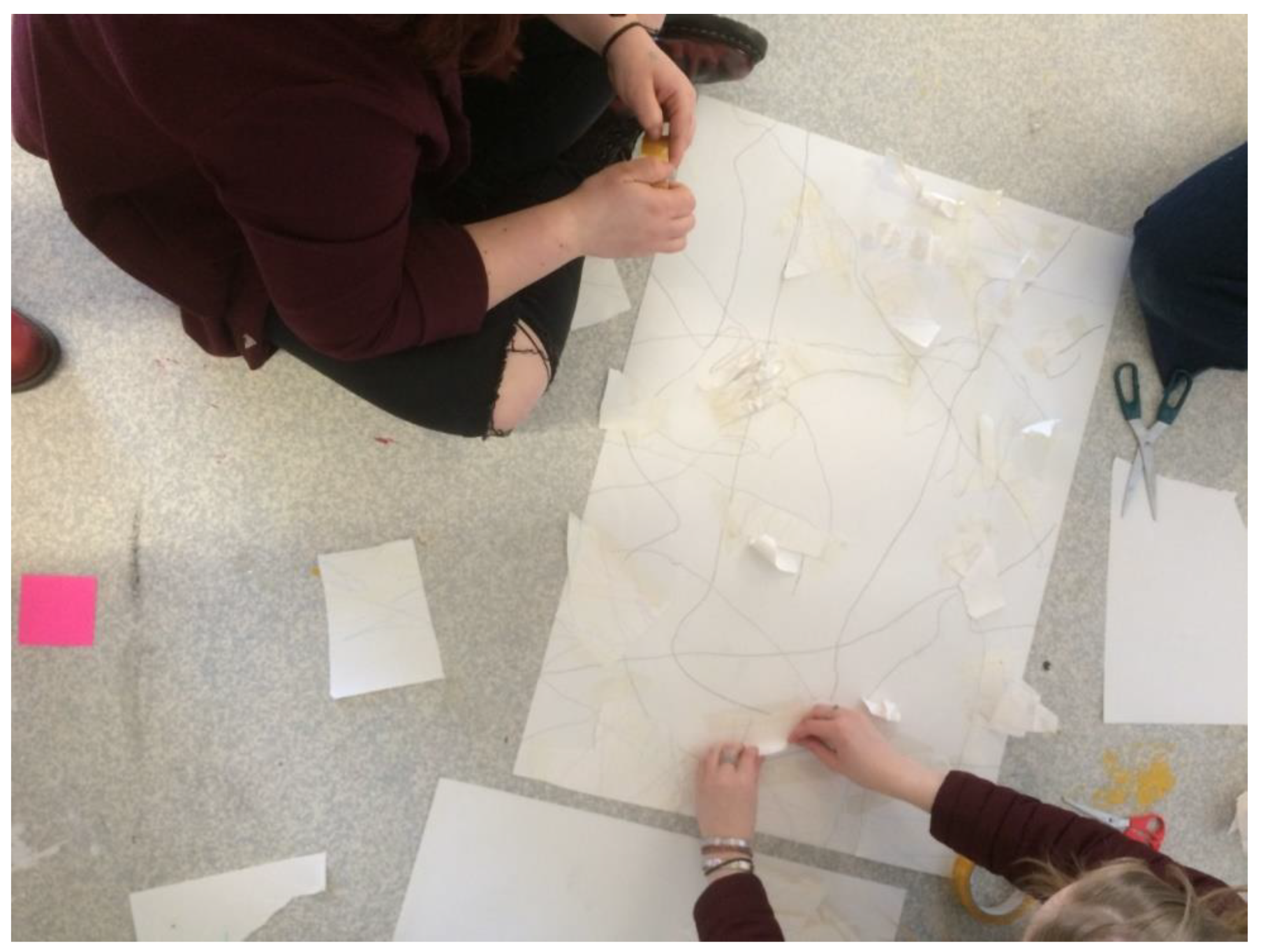

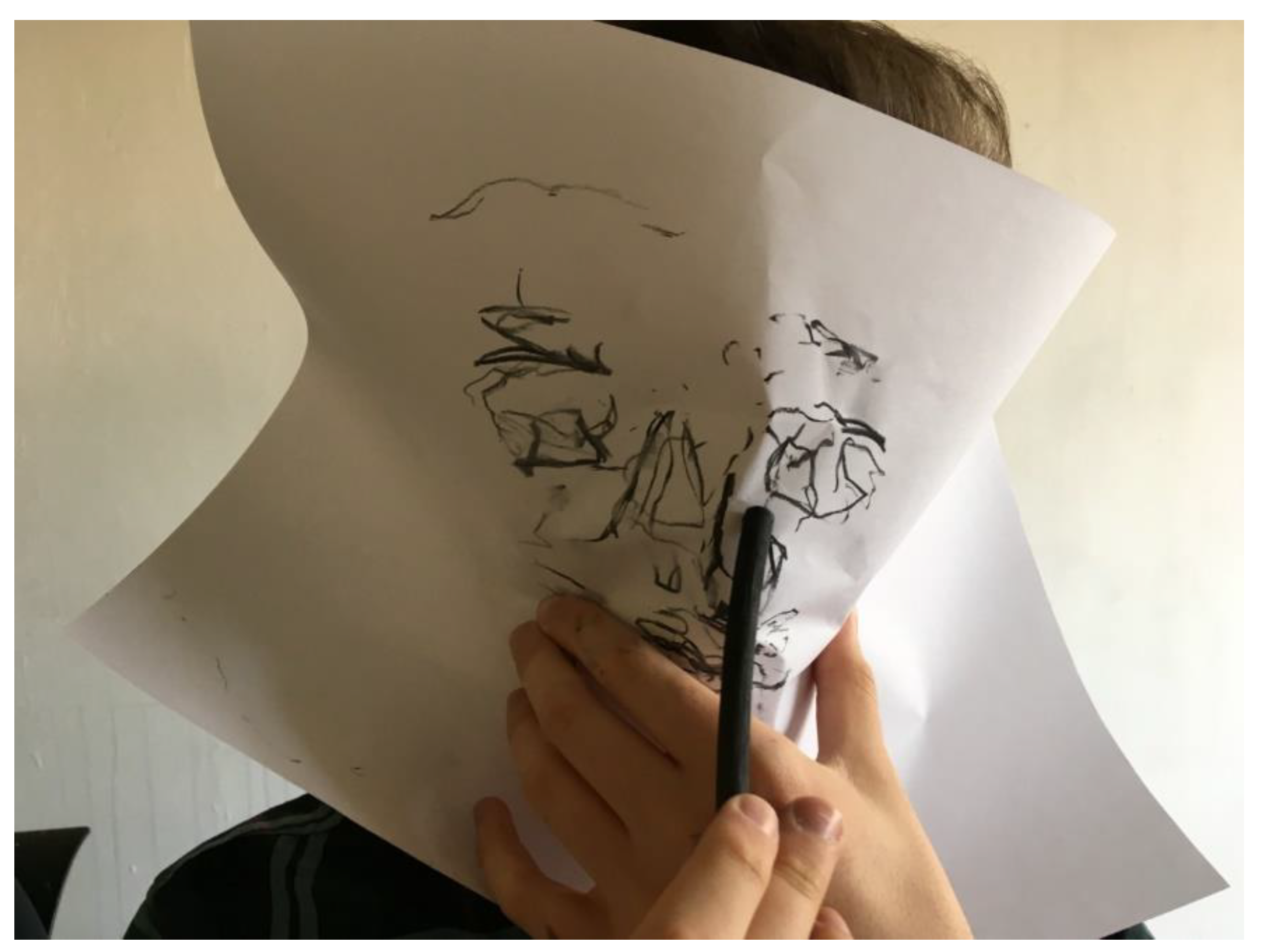

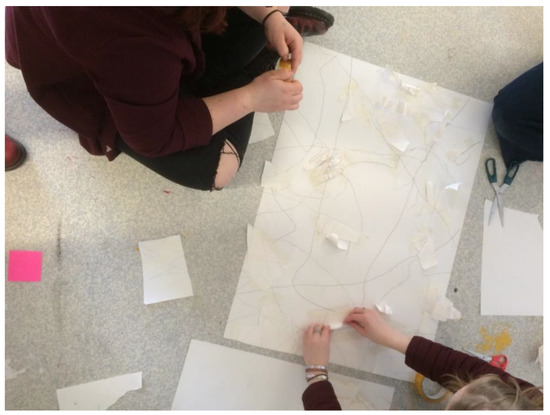

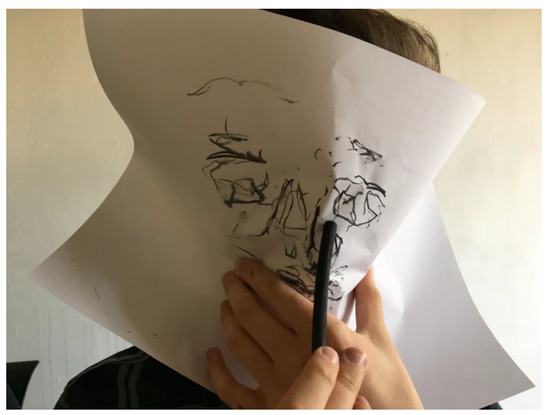

There is not a specific curriculum for UK Undergraduate Fine Art programs. Course design differs in each institution, yet conversations with colleagues at other institutions reveal the challenges faced are shared. At Northumbria University over the past three years the evaluation of induction processes and Year 1–semester 1 activities has generated qualitative evidence that demonstrate the requirement to adjust approaches and adapt the studio environment and pedagogy. In recent years the Fine Art program has increased focus on creative engagement with an 80 credit Studio Practice module. Supporting contemporary practice, the Year 1–Level 4 studio experience, models contemporary concepts, thinking and approaches. This filters into Levels 5 and 6. The first year is therefore crucial to prepare students for what follows. Student feedback and program review across the different year groups reveals it works well for those who are confident but many are unready for Level 4 working when they arrive and for many reasons resistant or simply struggle to learn independently; a pattern is emerging with the same number of students struggling to adjust and a similar number of Level 4 students leave. To address this, group activities are devised to support students to work speculatively and experimentally; this invites them to test ideas, explore materials, generate enquiry, develop collaborative processes and produce strategies for making (as illustrated in Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Thomas, J (2018). Undergraduate students collaboratively problem solving.

Figure 4.

Thomas, J (2018). Year 1 student self-portrait.

The following reflections outline some of these approaches and are current at the time of writing.

4. Supporting Positive Transition and Learning in Northumbria University’s BA Fine Art Programs

In order to develop students’ emotional intelligence and personal growth, teaching staff are required to scaffold opportunities to help students change perspective, transform frames of reference and reposition a standpoint that recognizes learning is not for the tutor instead tutors are there to guide, support and help make connections. With aim to facilitate self-awareness and openness, students need extra tools for growing a maturity of understanding and ownership. This process is about deconstruction, reconstruction and reinvention. Students often require support to recognize what the learning is and how to create or find it. To achieve this trust and individual confidence is essential to support student artists to actively explore creative routes to express themselves, question ideas and also frame this in a way that helps them challenge thinking, process and outcome.

4.1. Supporting Students to Adjust to a New Social Environment

Rutherford (2014) highlights the importance of managing student perception to support readiness; this influences their ‘mental picture of what education ‘is’, how it happens and the extent of what their responsibility is for achieving it’ (p. 92). Students need gentle and regular encouragement to own a clear understanding of their responsibilities towards their learning and the expectations surrounding that. Understanding and reiteration of program and personal expectations needs reinforcement at induction and ongoing (weekly or potentially daily) opportunities. The expectations and mental pictures need careful unpacking.

The students’ expectation begins before they arrive. This needs careful attention through recruitment and application processes, prior to starting the program and across the whole student experience. Academics need to ensure they are working with colleagues across institutions to support appropriate practices for attracting, interviewing and selecting applicants. At Northumbria University, to shape and inform expectation, we are exploring interventions that make the first point of contact as dynamic as possible. This includes active collaborative sessions to bring current and potential students together in situations that widen participation and deepen engagement. For the majority of cases this constructively shifts individual frames of reference.

Once the students start, we place more emphasis on tutor-led studio groups, phasing them deftly into the process in the first Semester 1. Determined by room layout, we create sub groups in the studio, encouraging a sense of community. Building smaller communities encourage familiarity amongst peers. Through group sessions and seminars, we unpack expectation, shape ‘mental pictures’ (Rutherford 2014) and explore what creative research and practice can be and how this extends in and out of the studio. Modeling behavior, habits and expectation, we visit galleries, libraries and museums; we watch films; we explore materials and unpack how these inform ideas. We encourage students to make connections on their own, with us and with each other.

4.2. Scaffolding Independent Learning

The transitioning process requires the tutors to initially lead and gradually supporting students to take ownership and responsibility for their learning. This process spans across the three-year BA experience. Aiming to emphasize attendance and nurture effective time management, the Year 1–Level 4 program requires a carefully balanced, full-time structure, devised to ensure daily staff contact. Regular independent studio practice sessions are included; however, the daily scheduled activities are vital to equip independent attitudes and mindset as the structure relaxes into Levels 5 and 6. Attendance monitoring, whilst arduous, helps identify when things start to slip.

Introducing a more flexible approach to tutorials can accommodate individual needs in an increasingly bespoke way. When coming straight from a school environment, students are often used to working closely with one teacher; having a range of different tutors giving differing advice can be confusing. Limited time-bound tutorials with a range of tutors can be replaced with a bank of time for each student with an allocated tutor. The student and tutor negotiate and plan when and how long the tutorials are depending on the need and processes of the individual student. Alongside this opportunities to sign up for tutorials with other academics offer a range of input and student choice. This approach can support an aim to phase students into new ways of working more subtly, building up shared understanding of practice, rather than students feeling they have to introduce themselves at every tutorial opportunity and limit confusion by hearing too many different opinions and voices.

By using questioning and material exploration as starting points a basis of enquiry is introduced, allowing students to make informed decisions and also embrace accidental and spontaneous developments. For this to work and for students to take ownership they have to feel safe. Working without a fixed end product and exploring areas that cause happy accidents or failure can be the hardest shift to embrace. Alongside questioning there should be facilitated structured opportunities for play. This is where the deconstruction and reconstruction of expectation can be most challenging. Many younger students are so fixed in their approaches and set on a final image; when reassured it is ok not to have a fixed outcome, they are often suspicious. Fine Art tutors are required to consistently boost confidence and encourage shared dialogue to reflect upon the learning.

4.3. Equipping Students for Collaborative Learning in a Higher Education (HE) Environment

Peer group interaction is an essential aspect of any BA Fine Art Undergraduate experience. At Northumbria University group work is maximized to promote interaction and develop team approaches that assist independence, maintain academic credibility and integrity. Discourse and collaboration create spaces to transform frames of reference and supports self-efficacy. Making space for individual working and for working with others is a shared process and sets up scenarios where students can look to each other for support. Environmental layout can strengthen conversation; by altering the layout of studios, creating islands of desk space, opposed to individual booths where students retreat and work with their backs facing the rest of the room. These islands increase opportunities for student artists to get to know each other, share ideas and connect.

Whole group sessions are invaluable in the first year of study; these active learning sessions should embrace risk, failure, support collective practice and, most crucially, play. For students who have come to university through Arts Foundation study pathways these experiences and approaches are usually more familiar and less threatening. In the past three years the Fine Art Team at Northumbria University have created a series of structured Studio Contact Sessions—nine in the first month of arrival. Singular sessions are not enough; even after nine some students reflected it was good when they could ‘do their own real work’ revealing the purpose of the sessions and learning created had not been recognized. These sessions facilitate working together in a large group exploring contemporary practice, often with follow up activity in their familiar studio groups. The sessions are used as opportunities to make connections with the workshops and lectures attended. By deliberately mixing the dynamic, approach and delivery to connect ideas, voices and experience, recognition develops across the year group between staff and students, adding to a sense of familiarity and knowing one another. These scaffold group critique, with the aim to cross-fertilize ideas and share practice and are introduced carefully to build trust and confidence. These sessions are also opportunities for co-production, with staff and students working together, helping familiarization and highlighting the creative process as an ongoing journey of open-ended learning.

Alongside this, smaller group seminars where tutors and students work together closely aide deconstruction and reconstruction of expectation, this increases student awareness of art school and studio culture, developing greater understanding of student responsibilities and involvement in shaping and developing learning. It is therefore important students value this from the outset; as a bonding process this creates the groundwork for the following three years’ experience.

4.4. Engaging Students with Contemporary Art and Moving Them Away from the Security of Familiar Practice

Smaller seminar sessions skill up a broader understanding of creative research. Initial bite size sessions can introduce different theories and movements with inclusion of co-constructive, material exploration where staff and students learn together. Expanding awareness and potential of critical interdisciplinary practice, sessions like these also facilitate further acceptance of open-ended enquiry and trust in process (rather than product), shifting perception of tutors as fellow artists, rather than teachers who instruct.

We are lucky; Northumbria University is located in a city where provision for contemporary art is great. Cultural experiences foster opportunities to consider engagement, reception and question the role art can play to challenge and stimulate exchange. Gallery visits maximize connections between regional resources and the organizations we encourage students to access independently, supporting them to think locally, as well as globally, whilst also connecting to a diverse range of professional practice, themes and debate. Often the most valuable learning happens not just inside these venues but also on the journeys to and from or in the studio afterwards.

Short film screening sessions introduce contemporary practice and context. Alongside moving image work, feature films help to widen dialogue, scaffolding recognition and application that a range of influences, resources and material can inform creative research.

At Northumbria University we are also fortunate to have a regular Contemporary Art Guest Lecture (CAGL) series. The creative practitioners, artists and researchers who deliver these lectures offer a rich insight into the diversity of contemporary art and range of professional practice. We recognize Year 1–Level 4 students engage more effectively when prepared; we therefore invite studio groups to elect representatives to present research on each guest prior to their lecture. This opens up into whole group discussions, resulting in independent research, connections being made and ideas explored. As a result, we find students asking intelligent questions as they are better equipped to appreciate practice they otherwise may have found too challenging.

As outlined, peer learning plays an important role to engage and orientate students with contemporary art practice and shifting from the security of familiar school practice that may or may not be driven by contemporary frameworks. Facilitating visits to Level 5 and 6 studios develops awareness of how those already engaged in the business of making art are approaching practice and reveals how varied it is. This can offer reassurance and it does not have to be unnecessarily complex. Alongside this, a buddy system can positively aid connections, further equip social learning and help adjustment to the new learning environment.

Additional activities such as residential retreats, Project Weeks, student-led and guest lecturer workshops and practice exchanges are scenarios where the familiar curriculum is relaxed and students work across year groups. These opportunities enable students to apply and negotiate how their practice contributes to a wider social and cultural context and dialogue. The challenge here is they often do not consider this learning because they experience increased fun so it does not feel like learning.

4.5. Encouraging Students to Reflect on Their Learning

The studio activities described earlier, introduce reflective and experiential learning. To bring awareness to the reflection woven across these experiences, the staff team are required to carefully build in pauses to consider what is happening. Many students are anxious about talking in front of others. Varied approaches can address this including feedback or questions using post-it notes, short written reports, alongside deliberately posed questioning and follow up tutorial discussions. By sharing work through exhibition practice from the outset, students become familiar and more confident with collaborative situations they will encounter throughout the program and beyond.

Student blogs can be useful. Commonly students feel comfortable posting insightful and constructive reflections about their own practice and the work of studio group members using online platforms. This offers critical engagement where paradoxically, despite the public nature of these posts, they feel less exposed. While less helpful in the moment, it can elicit meaningful opportunities to value new developments and reflective problem solving. Blogs can be shared through seminars and used to enhance tutorial discussion; this not only supports individual confidence, it deepens encounter within the year group.

Active use of studio logbooks (or planners) can promote better time-management and allow a hand-held, tactile, visual prompt to exemplify and take ownership of the semester. This enhances verbal, screen based and notice board communication and requires applied engagement. As well as outlining the various stages leading to assessment, this aims to assist students to plan effectively and facilitate active reflective learning. The challenge here is to facilitate recognition that the logbooks are for individual benefit and not the tutor. Logbooks support ongoing self-assessment and provide written opportunity to recognize how and where student choice is encouraged, helping student artists become resourceful, divergent thinkers who are able to understand the bigger picture and to create a meaningful and sustaining practice.

5. Discussion

5.1. And Shift

The questions and approaches described reflect directly on the practice within the Art Department at Northumbria University. Whilst creating the right experience for every new learner may not be realistic or achievable the transition process needs to carefully (and inclusively) equip social learners to engage confidently with contemporary art and for student artists to be prepared to take ownership while extending their comfort zones. How we improve the quality and appropriateness of student experience is something we constantly review. The challenges should not be underestimated, with common institutional priorities influencing departmental decisions, playing direct impact on team delivery and program expectation. Recruitment requires a careful joined up approach and this can prove challenging in the wider landscape of HE demands. Employability has growing emphasis and widening participation has been long identified as a national agenda. Pressures on space, reduced budgets, high staff to student ratios and increasing bureaucracy shed considerable influence on departmental practices. Add to this the escalating demands to produce publishable research, hit income targets and guarantee student satisfaction. The pressures on recruitment mount and suddenly more and more barely eighteen-years old are arriving in the UK’s University Fine Art studios struggling to orientate themselves. These young people need increasing support and look towards tutors to tell them what to do. When the experience becomes challenging and assessment deadlines loom, student anxiety levels increase, confidence and trust can diminish and the memory of the safe school structure seems unbearably hard to let go. To appropriately support transition from the school to university, Fine Art teams need to proactively shift an assumed position and continue to adapt and redesign curriculum.

Better understanding between Higher Education and secondary schools is imperative. In the UK organizations such as The National Society for the Education of Art and Design (NSEAD) offer invaluable support for teachers to aid interpretation of the statutory National Curriculum for art and design. These organizations also provide forums for debate and discussion. Creating more effective connections between secondary school and HE colleagues might offer a partial solution. Strengthening these connections and widening the discussion has potential to bridge gaps and generate a shared, relevant understanding of expectation and perception. School teachers need to appropriately prepare pupil expectation and University tutors need to value and acknowledge the previous experience of students to foster a sense of security and trust.

Tutors need to get to know new students in a timely manner. This is only achievable through shared dialogue and clear communication. In summary, creating appropriate experiences prepare student engagement and help manage expectations. Key routes for how to equip Year 1–Level 4 student artists are suggested in the following three strands: Collaboration, Induction and Communication.

5.2. Collaboration

Admissions play an important role in managing expectations. If recruitment pathways are not aligned with academic program experience, this results in Fine Art teams having to do more remedial work. Institutional admissions policy and practice needs joined up design and delivery. Clear guidance and advice are required at application stage to support a process that aligns expectation and offers insight to the reality of experience.

Although staff capacity and workloads limit opportunities, attending teacher networks and working more closely with colleagues in secondary schools and initial teacher education (ITE) open invaluable routes to join connect thinking and practice. Shared dialogues and continuing professional development (CPD) offers have potential to support a better understanding of expectations both at secondary and HE level. These opportunities can positively foster a more integrated approach to prepare young students to engage with contemporary thinking and practice.

5.3. Induction

School outreach can impact positively when integrated into university recruitment strategies. Direct input from Fine Art Team staff members with school visits can significantly sway pupil understanding and also offer a reassuring familiarity pre and post arrival. Involving current students as enthusiastic, inspired advocates can prove even more successful. Finding room in budgets and pressured workloads to prioritize these interactions, at the right time, can bring long-term beneficial return.

Open and enquiry days need to be engaging, informative and honest. These should not just sell institutional opportunity but should ensure the pupils and parents attending are fully informed, aware of expectations and fully briefed on program demands and contemporary fine art content. Pre-entry and keeping in touch activities (including engaging online methods) invaluably inform, excite and equip expectations. These can ground contemporary approaches and invite apposite preparation.

Through careful thought and planning, successful induction leads and scaffolds expectations and supports appropriate mental pictures and frames of reference (Rutherford 2014). Pre-arrival activities can foster independent thinking and extend prior learning. On arrival, Fine Art teams need to give this value and support students to develop and challenge the frames of secure, familiar references that accompany them. This needs to be implemented through structure with clear guidelines, diverse and gentle approaches that initiate them into new ways of working.

5.4. Communication

Clear guidelines need repetition and validation. The first few introductory sessions can be overwhelming and students may feel unconfident about speaking out. First year students are bombarded with new information, tutors need to promote understanding through diverse communication routes; this helps accommodate different learning styles and reinforces information. Students need opportunities to process information and ask questions. The approaches need to be face-to-face, virtual, collective and individual. Guidelines need to be written down as well as heard. Processes need to be tacit and understood through location, active and experiential learning.

In addition to regular studio meetings, student representative meetings help Fine Art Teams understand the student experience and create opportunities to trouble shoot. The communication this generates can be addressed at team meetings, allowing reflection and action to ensure the student experience and transition is constructed, supported and facilitated as appropriately as possible.

6. Conclusions

As Broadfoot (2017) recognizes:

To combat loss, my suggestion is we need to create evolving structures. We need to continue to ask questions and constantly reconfigure and reassess teaching strategies. At the same time, and fundamentally, we need to keep true to our hearts what we passionately believe contemporary fine art practice is and can be (I believe this should include being risky, difficult, exciting, mysterious, beautiful, ugly, awkward, open ended, limitless, formed and unformed) without dumbing down or diluting the student experience. Imperatively, tutors need to get to know and understand new arrivals quickly. Students need to know how to access help. They need to have a friendly, accessible contact to talk to from the outset. They need clear structure and this is still possible within a lose framework. With student review and feedback studios can be reshaped into spaces where students are prepared for and excited about independent learning. Tutors need to listen to and acknowledge student needs and insecurities. The student journey can be difficult and may require the tutors to lead initially with close guidance, then eventually signpost the way. The journey should be challenging but equally exciting and inspiring. Students need to trust the tutors and the tutors need to trust the students as they become increasingly independent and shift to being confident in finding their own way. Sustainable processes are required to accommodate different maturity, self-awareness and to develop meaningful practice and ownership of learning.Every student that drops out of their higher education course is a loss. A loss to their university or college, a loss to the future economy and, above all, a loss to that individual. Equally, students who don’t actually drop out but who fail to achieve their full potential also represent a significant loss to both themselves and society. The issue of student retention and success in higher education is, therefore, an issue that is becoming more important in the sector day by day (p. 7).

Ultimately, alongside students, tutors also need to be responsive, reflective learners and problem solvers, objectively recognizing if programs are working and when curriculum needs to change. Tutors need to be explicit to students about the approaches taken in order to manage expectation and appropriately equip learners as they shift from A-level Pupil to Undergraduate Student. Through careful collaboration, induction and communication a positive shift can support transition between school and university.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements go to the students and colleagues in the Fine Art Department at Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. All figures used in this manuscript have been created by the author © Judy Thomas.

References

- Austerlitz, Noam, Margo Blythman, Annie Grove-White, Barbara Anne Jones, Carol An Jones, Sally Morgan, Susan Orr, and Alison Shreeve. 2008. Mind the gap: Expectations, ambiguity and pedagogy within art and design higher education. In The Student Experience in Art and Design Higher Education: Drivers for Change. Edited by Linda Drew. Cambridge: JRA Publishing, vol. 6, pp. 125–49. [Google Scholar]

- Broadfoot, Patricia. 2017. Foreward. In Supporting Student Success: Strategies for Institutional Change. What works? Student Retention and Success Programme. Available online: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/hub/download/what_works_2_-_full_report.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2019).

- Cultural Learning Alliance. 2018. Further Decline in Arts GCSE and A Level Entries. Available online: https://culturallearningalliance.org.uk/further-decline-in-arts-gcse-and-a-level-entries/ (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Franklin, Alex. 2018. Auditing creativity? The UK Art School in the age of neoliberalism. In Art, Materiality and Representation. London: The British Museum & SOAS. [Google Scholar]

- NSEAD. 2016. The National Society for Education in Art and Design Survey Report 2015–16. Available online: http://www.nsead.org/downloads/survey.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- Rutherford. 2014. Improving student engagement in commercial Art & Design programs. iJADE International Journal of Art & Design Education 34: 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Shreeve, Alison, Ellen Sims, and Paul Trowler. 2010. ‘A kind of exchange’: Learning from art and design teaching. Higher Education Research & Development 29: 125–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UCAS. 2016. Record Numbers of 18-Years Old Accepted to University This Year. Available online: https://www.ucas.com/corporate/news-and-key-documents/news/record-numbers-18-year-olds-accepted-university-year-ucas-report-shows (accessed on 30 January 2019).

- UCAS. 2018. Applications by Applicant Domicile and Subject Group: England. Available online: https://www.ucas.com/file/147861/download?token=v6pEGF8E (accessed on 21 December 2018).

- UCAS. 2019. 2018 Entry UCAS Undergraduate Reports by Sex, Area Background, and Ethnic Group. Available online: https://www.ucas.com/data-and-analysis/undergraduate-statistics-and-reports/ucas-undergraduate-reports-sex-area-background-and-ethnic-group/2018-entry-ucas-undergraduate-reports-sex-area-background-and-ethnic-group (accessed on 30 January 2019).

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).