2.1. The Political Economic Context and the Autarkic Production for Architecture and Design

In order to understand the Italian context of those years and the evolution of the autarchic economic policy, it is important to remember that the autarchic phenomenon began in the early 1920s and developed gradually (

Giardina et al. 1988).

The year that marked the seriousness of the economic crisis that had broken out two years earlier was 1931. The theme of the relaunch of the internal market took a leading role, and the development of scientific research on advanced technologies became a primary importance. In Italy, for this purpose, the CNR (National Research Council) was founded under the direction of the inventor Guglielmo Marconi (1).

Afterwards, with the worsening of the economic crisis, international trade weakened. Beginning in 1933, the nationalist perspective strengthened and the autarchic process was subject to a strong acceleration (

Maiocchi 2013). Benito Mussolini assumed de facto dictatorial powers in January 1925 and, in view of the war, traced the definitive stance of the economic policy providing the maximum exploitation of the national resources and a strict corporatist organization (

Mussolini 1957). The construction of the Italian Empire began to take place with the war of Ethiopia (1935–1936) and became the dominant element of Italian politics. In October 1935, the League of Nations deliberated economic sanctions against Italy, which were implemented in November. The embargo concerned arms and ammunition, the system of loans and credits, and the import and export of goods necessary for the war industry in Italy. These limitations forced Italy to concretely realize autarky, and the construction sector was one of the most involved production areas. In 1937, autarky assumed the characteristics of a concrete plan, consisting of a set of coordinated measures whose development was expected to unfold over a long period (

Anselmi et al. 1938). First of all, the scheme contemplated a set of synergic actions focused on production applied to key industries (metallic minerals, textiles, solid and liquid fuels) and on consumption associated with the fight against waste. These actions were integrated by exploiting all the possibilities of replacing products whose raw materials were scarce or not present on Italian soil (

Maiocchi 2013;

Dal Falco 2013, pp. 68–77).

The collapse of the scrap iron import, fundamental for the steel industries, posed the problem of replacing metal materials with the consequent abrupt arrest of the construction sector. In order to relaunch the construction industry, autarchic methods were studied, which included lightening the weight of buildings by replacing traditional masonry with insulating materials. Naturally, these products were linked to the spread of reinforced concrete and iron structures—a great technical innovation that marked the architectural research of the modern and of the Italian architecture of the period (

Ascione 2017, p. 330).

Insulating materials were cheap products characterized by high performance. Italian products referred to German, French, and American patents, and were distinguished by their constituent elements, production techniques, and uses. The Eraclit, the Populit, and the Carpilite were made of wool and vegetable residue conglomerates impregnated with magnesite and hardened with concrete. Other groups were those of wood fiber derivatives such as Masonite and Cel-bes, of cork such as Absorbite and Asphalted Cork, or products that used wheat or rice straw stalks compressed and bound with iron wire such as Solomit, licorice roots (Maftex), or sugar cane fibers (Celotex) (

Cupelloni 2017, pp. 328–29). The pumice stone—present on Lipari island—was used in concrete conglomerates. Then, instead of the reinforcing steel used for pillars and beams, bamboo elements or aluminum bars were tested (

Maiocchi 2013).

The buildings’ external cladding played an important role in the construction industry autarky. The use of stone materials, widely present on Italian soil, was strongly supported by autarchic propaganda (

Dal Falco 2017, pp. 86–87). Marbles, stones, and granites were especially recommended for public works in order to reinforce the solidity and monumentality of buildings (

Poretti 1990).

The use of reinforced concrete and steel skeletons resulted in a drastic reduction of the load-bearing walls. Stones and bricks continued to be utilized to build structures, although the autarchic limitations forbade the reinforced concrete for buildings over five floors (

Cupelloni 2017, p. 28).

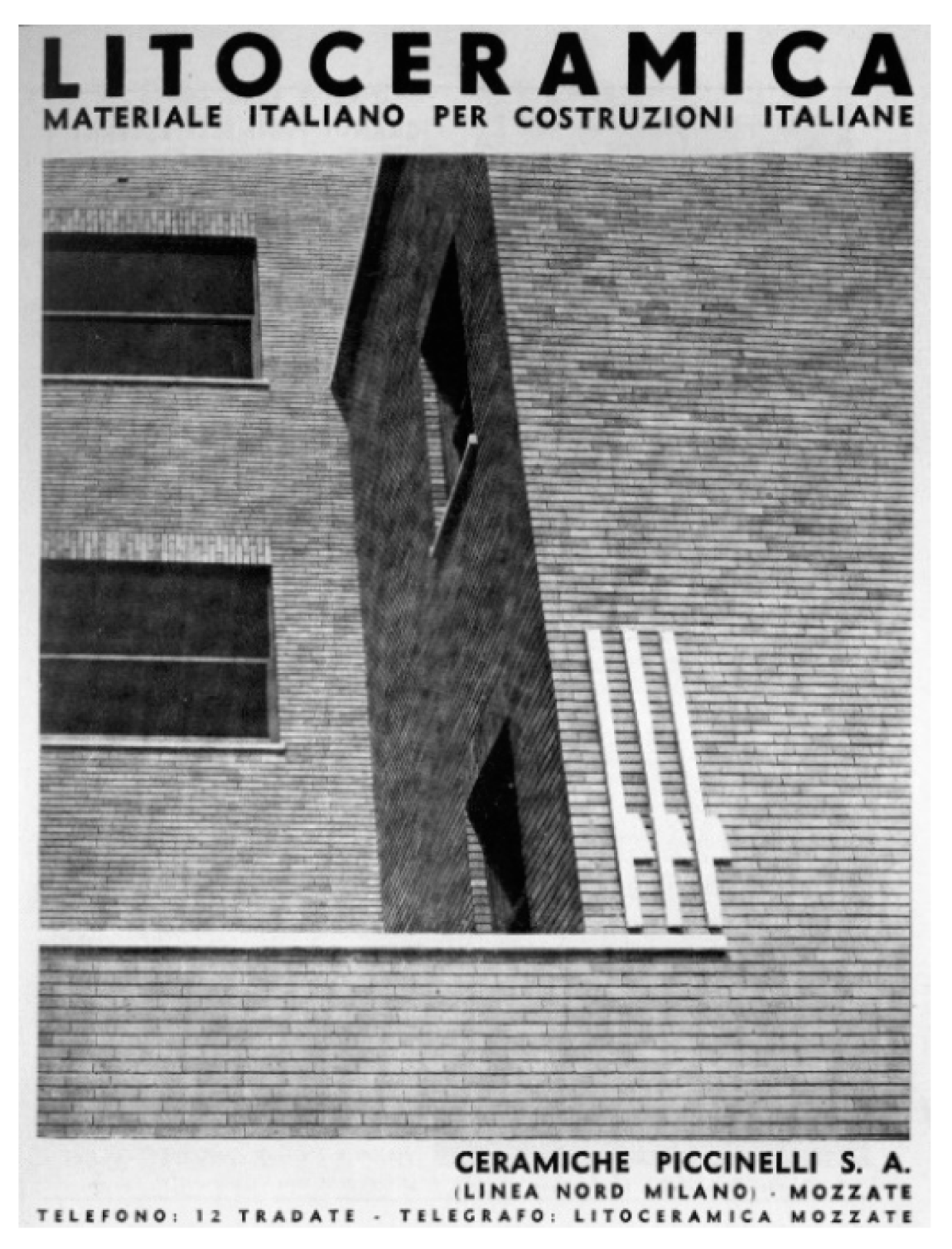

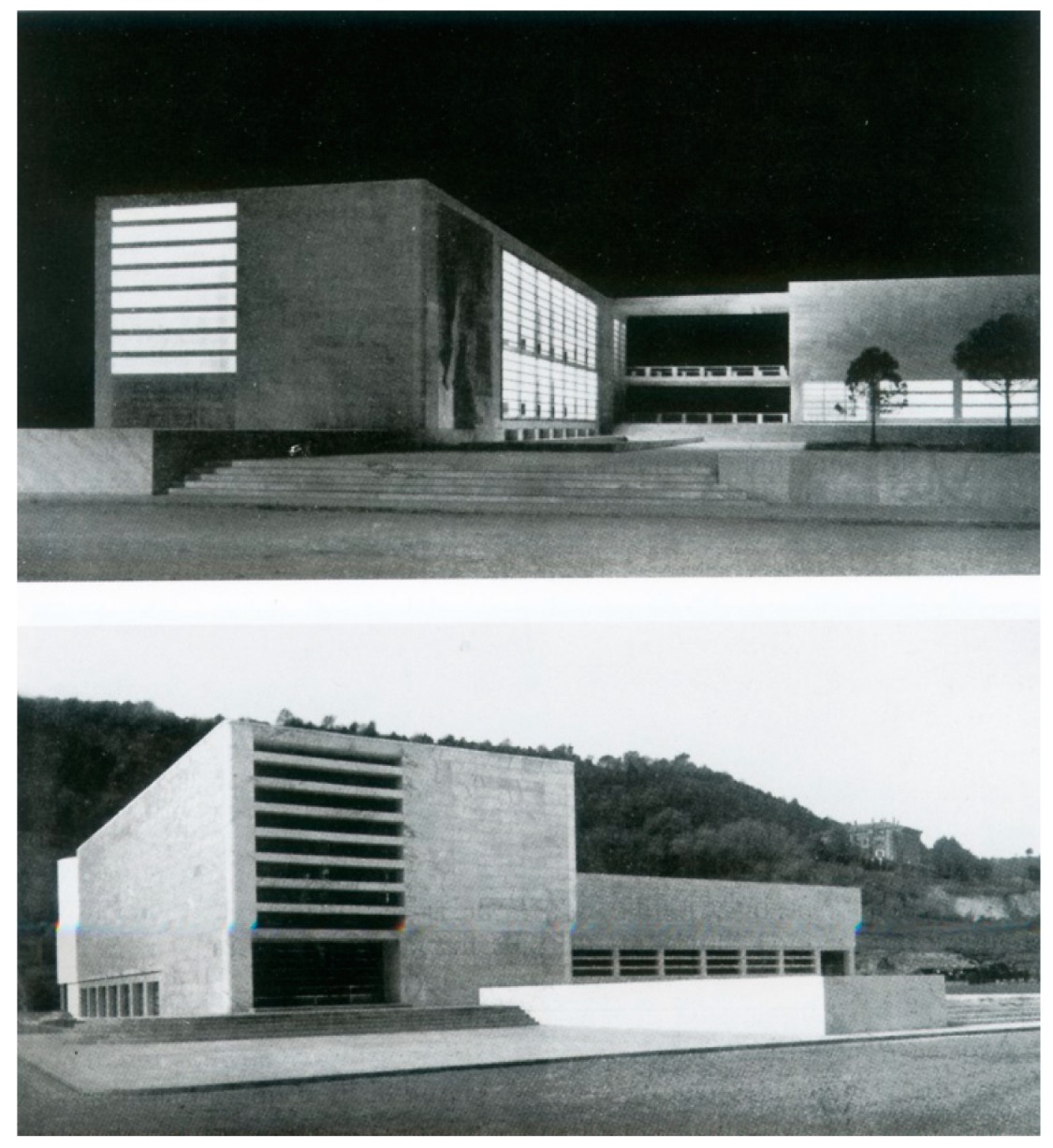

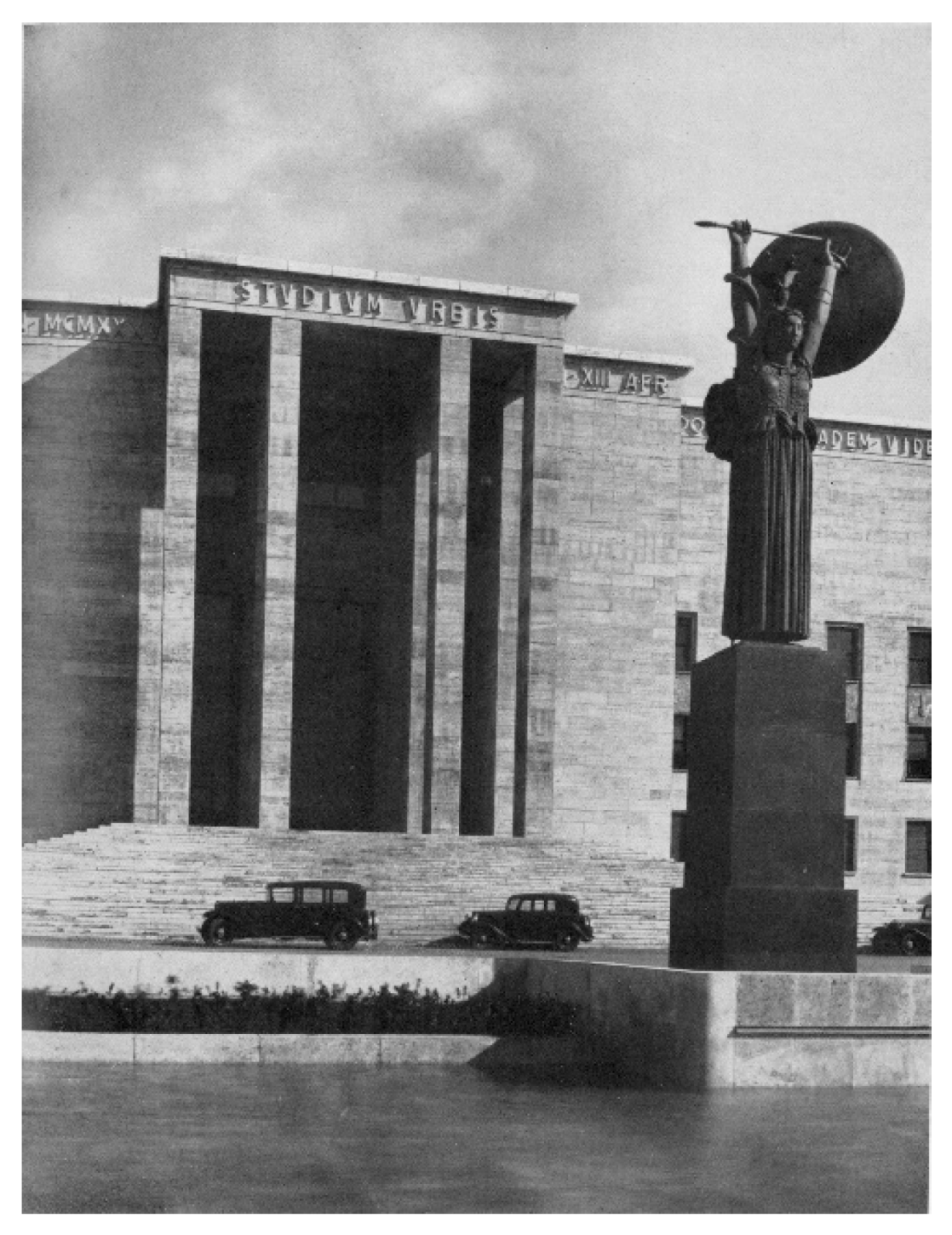

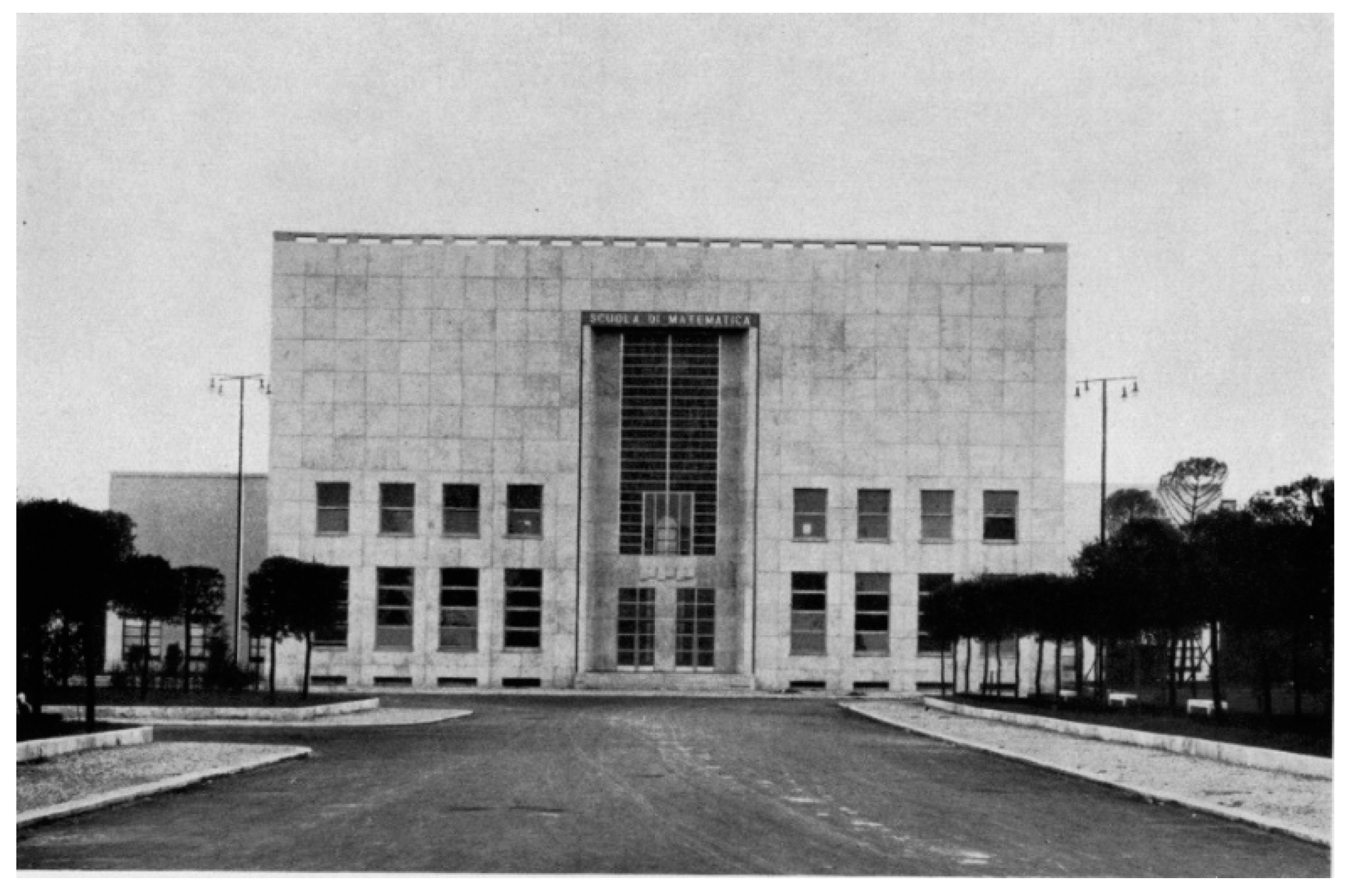

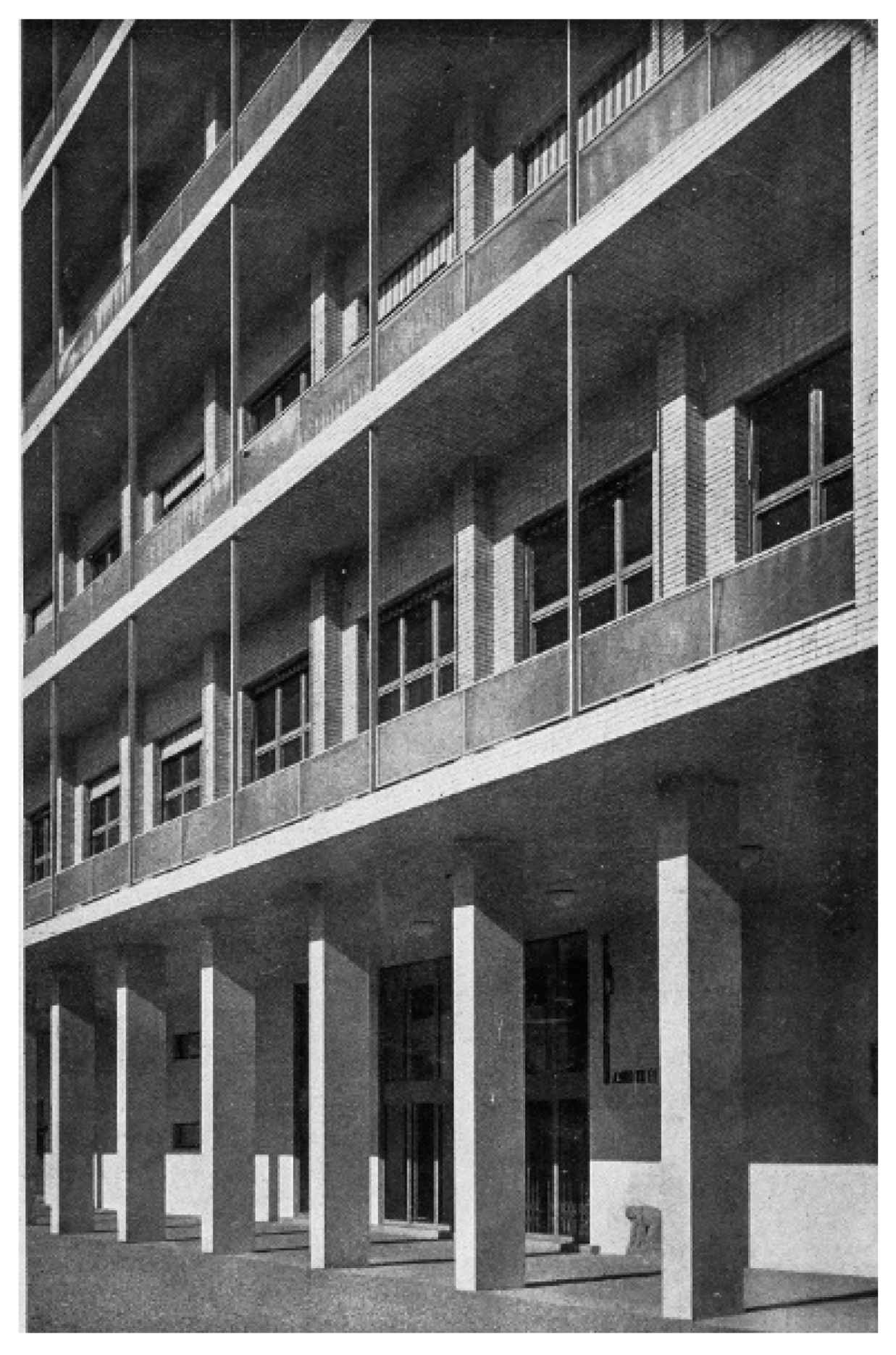

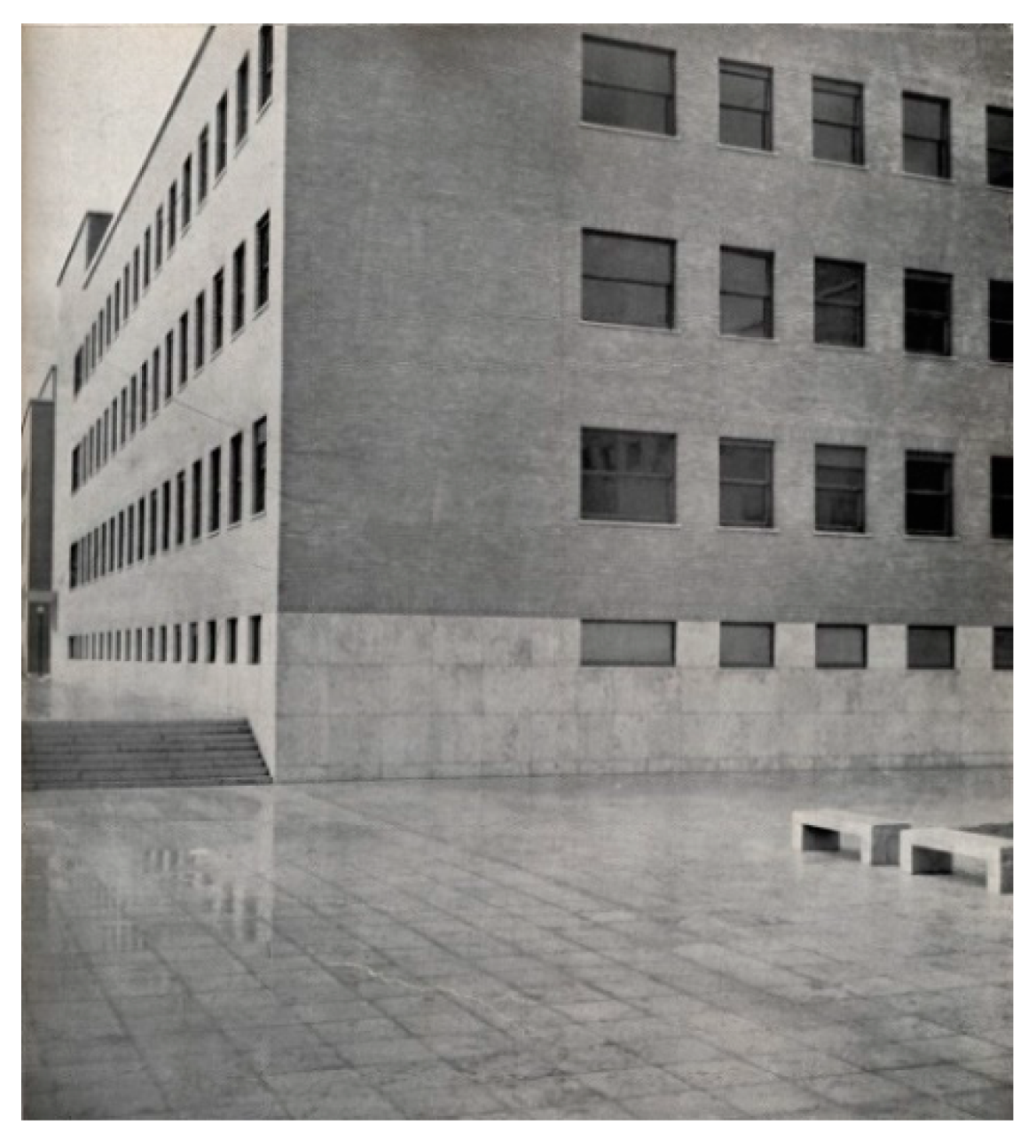

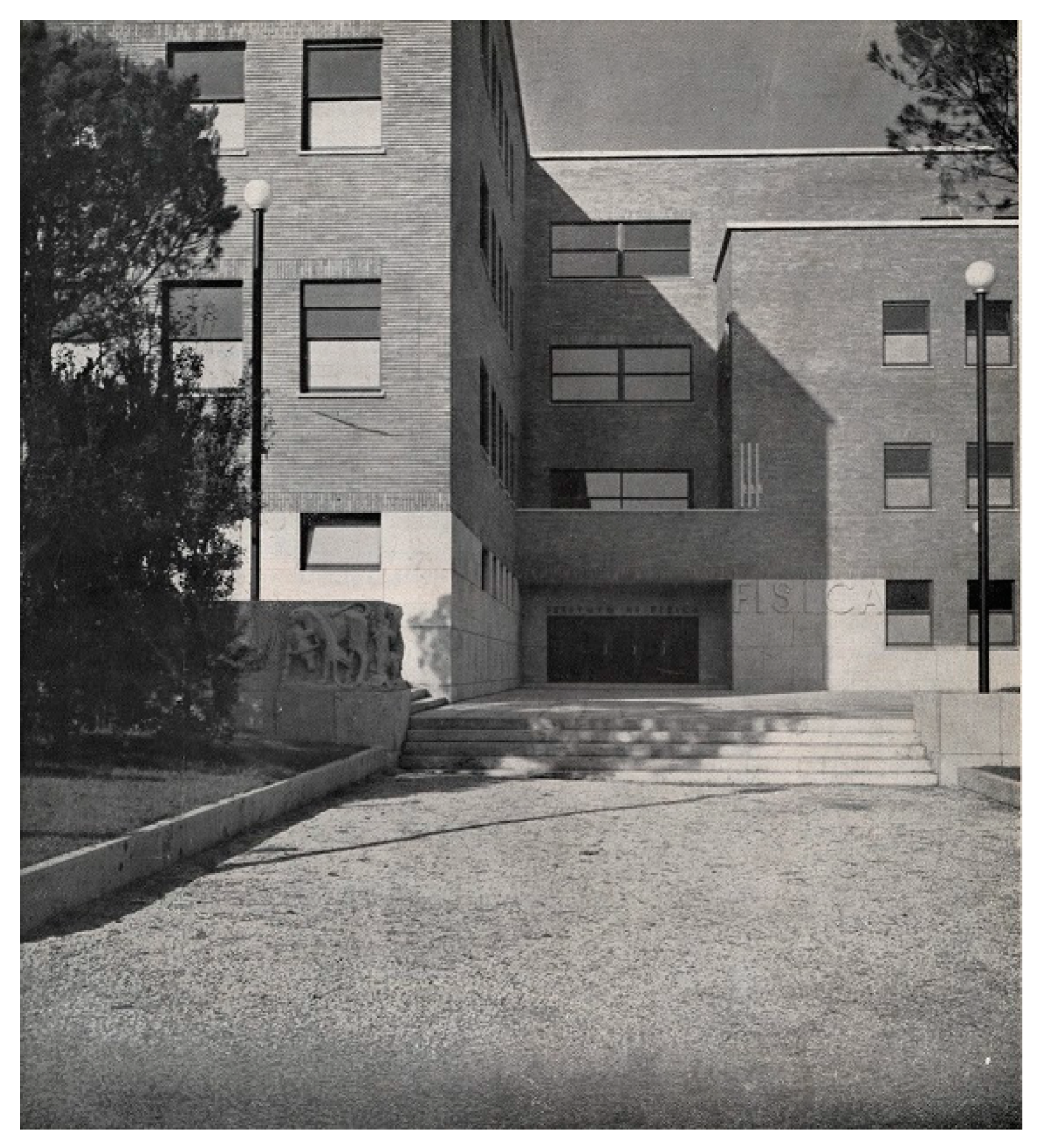

In the pillar-pillar plugging, solid bricks were replaced by perforated bricks, and the construction of brick walls with interposed inner tube became a common practice. The Litoceramica, which simulates the size and the appearance of the brick, is a new material for exterior cladding, and it has a color palette ranging from dark red to yellow-grey. Hard and compact, the Litoceramica was produced by the company S.A. Ceramica Piccinelli from Bergamo and was widely used in public works, as for the Città Universitaria (1933–1935) in Rome (

Bernardini 2017, pp. 146–50) (

Figure 1).

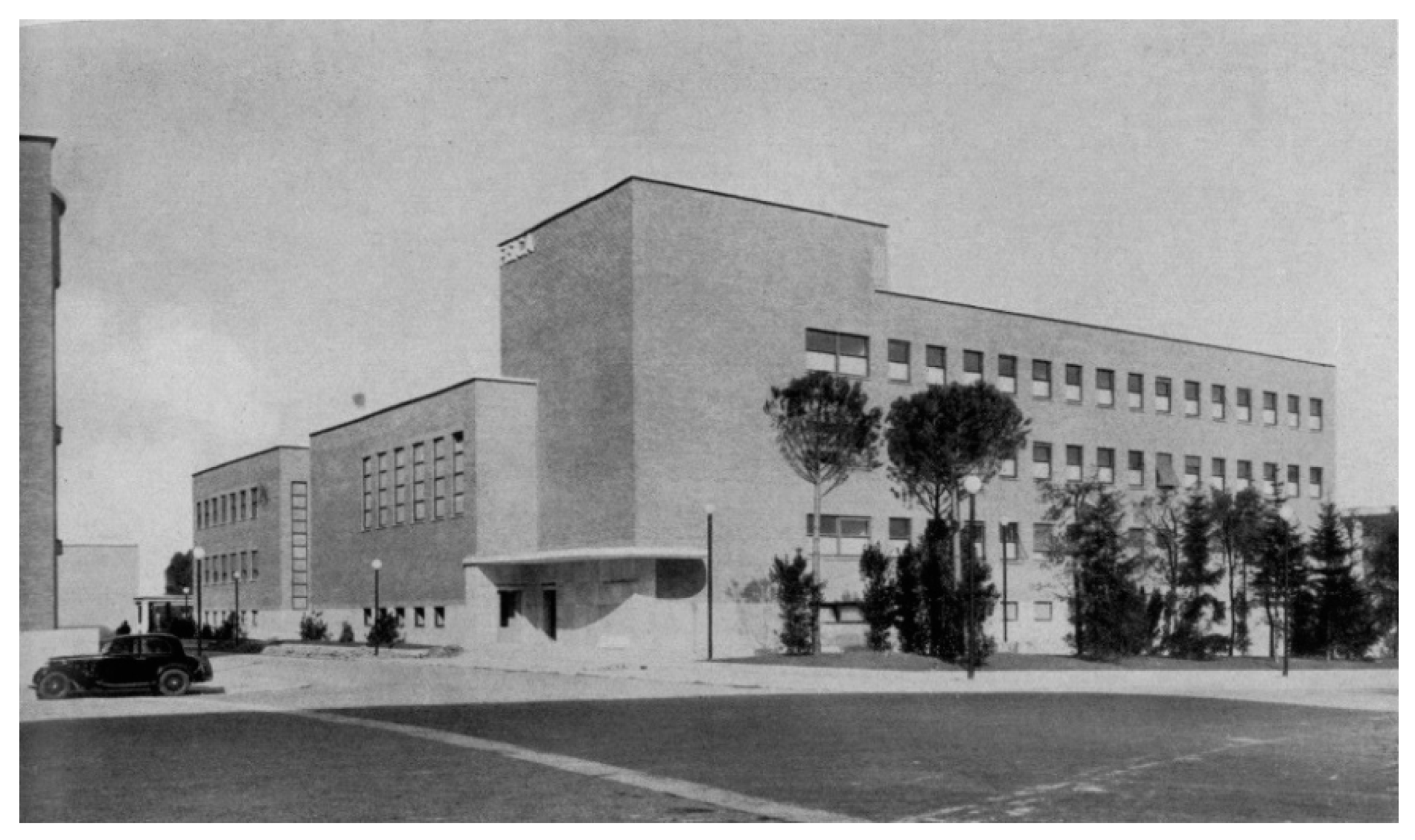

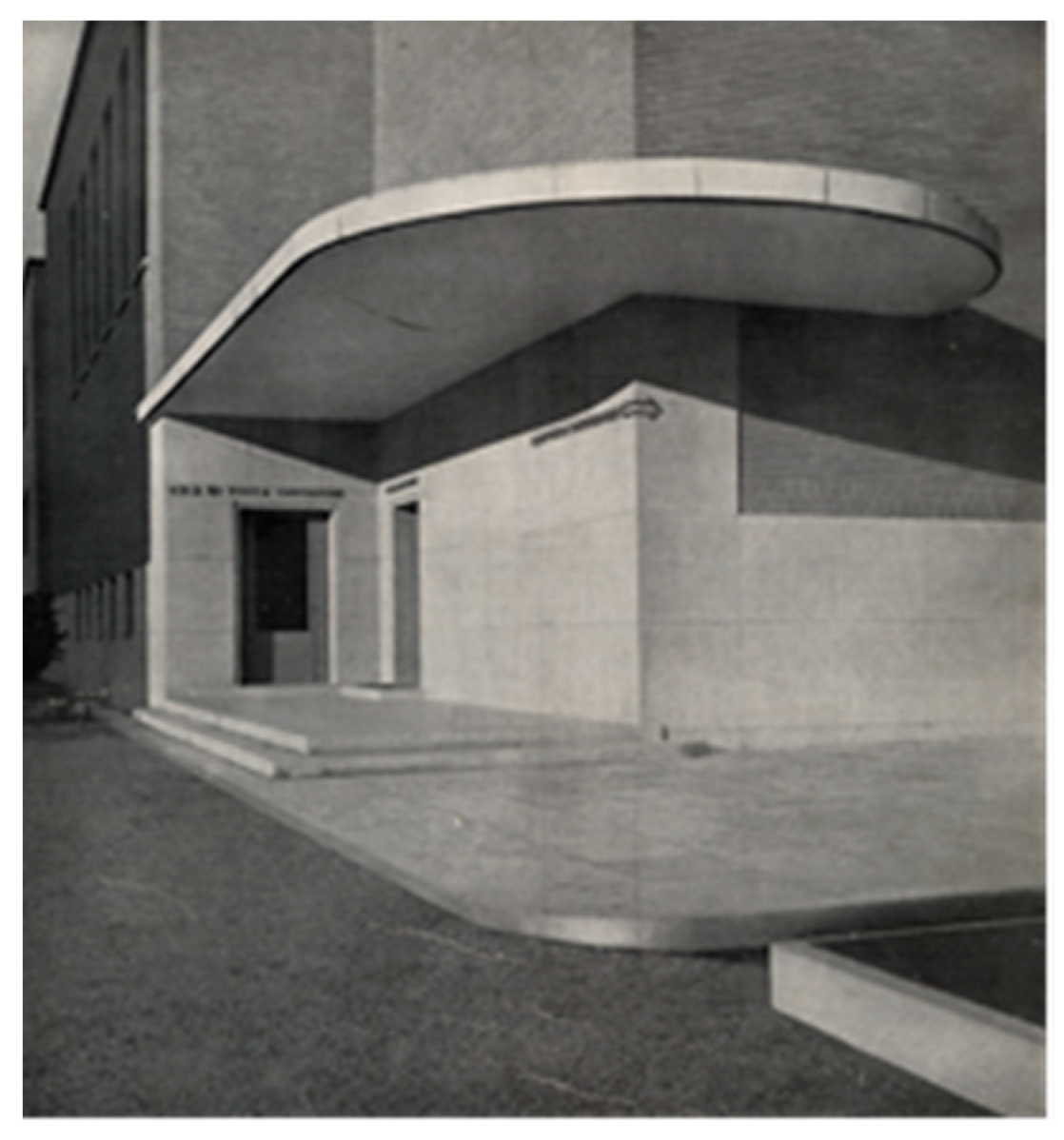

The import restrictions, the national resources exploitation, and the fight against waste favored the use of wood processing derivatives with the aim of producing practical and cheap coatings (Faesite, Masonite, Insulite, Buxus) as replacements for traditional materials. In fact, this product category presented all the characteristics of the regime propaganda that combined the autarchic appeals with an emphasis for the new. The Faesite was obtained by recycling the sawmill residues and was produced in five types from extra-porous to extra-hard. An interesting Faesite application was the realization of removable and interchangeable partition walls that divided office rooms (

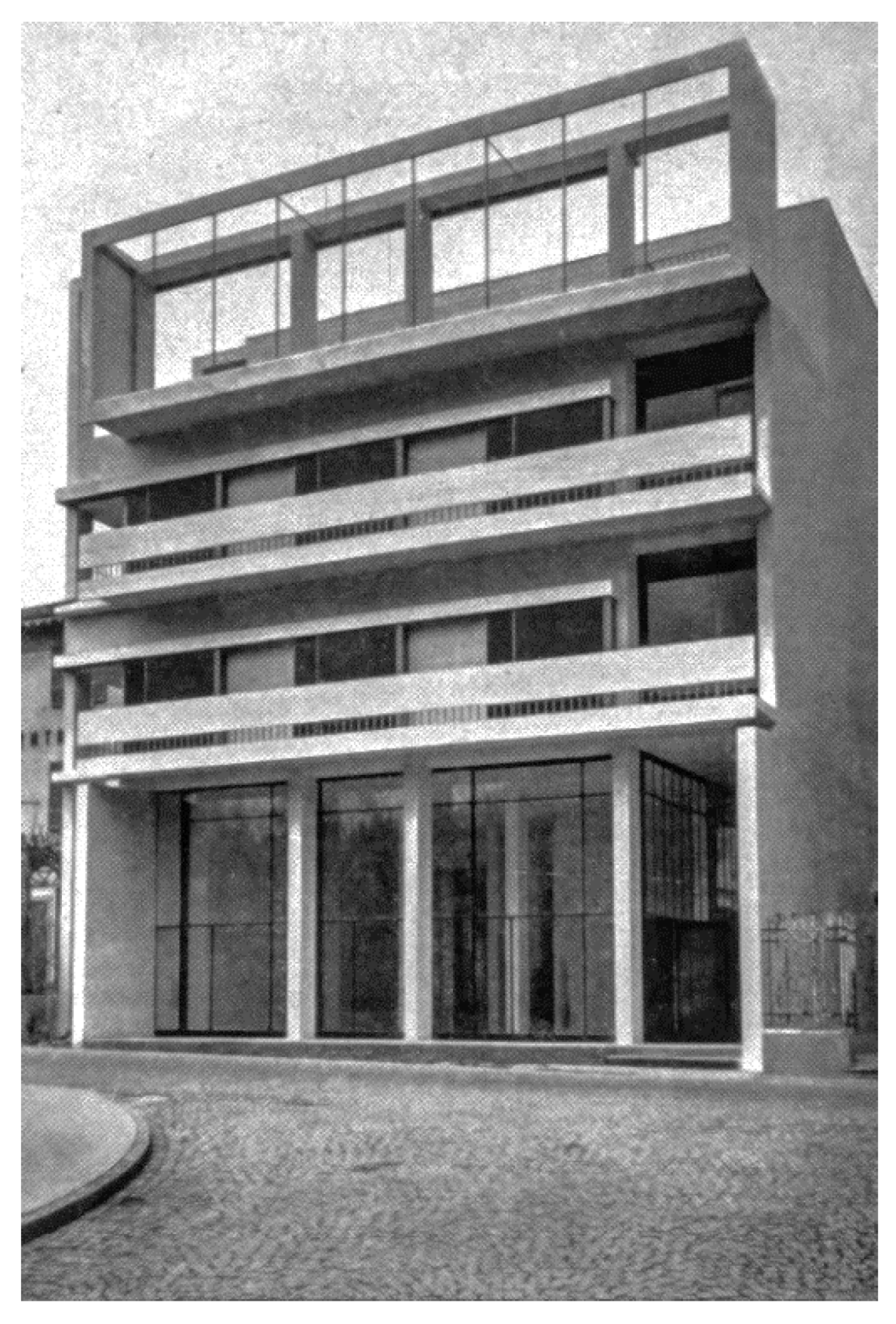

Dal Falco 2002, pp. 257–89) in the office buildings of Montecatini (Milan, 1936–1938) by Gio Ponti (1891–1979). Similarly, the Masonite was a reconstituted wood obtained from the manufacturing of waste wood materials. This product was used to make some elements of the Rent House in Cernobbio (1938–1939) by Cesare Cattaneo (1912–1943) (

Figure 2). It is a small and complex building characterized by a concept of poly-dimensionality evident in the façade design where the ground floor, the overhangs of the balconies, and the last floor are balanced. The natural Masonite was used to cover the internal doors and the external windows doors set back from the perspective line (

Dal Falco 2002, pp. 365–81).

In the context of a modernity global design and in respect of autarchic indications, Buxus and linoleum exemplify the trait d’union between architecture, interior, and furniture design.

The Buxus was produced by Giacomo Bosso paper mills in three types—the “concia molle” type used to coat boxes and suitcases, the “semi-rigid” type for furniture veneering, and the “thin” type to cover walls replacing the upholstery. For its flexibility, solidity, chromatic qualities, and the surface marble veins, the Buxus was considered a product between craftsmanship and industry (

Garda 2017, pp. 346–47;

Pagano Pogatschnig 1934, p. 48).

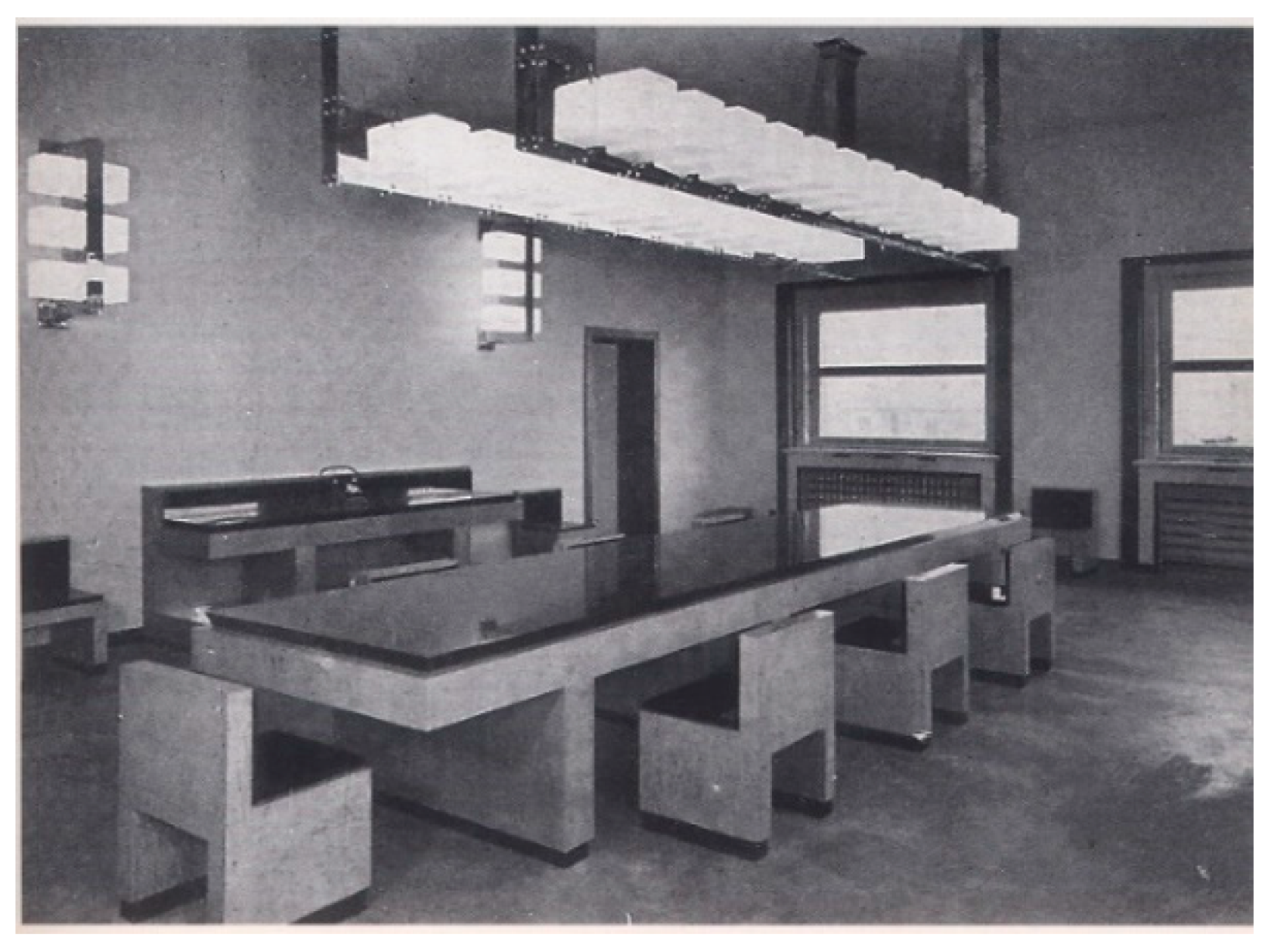

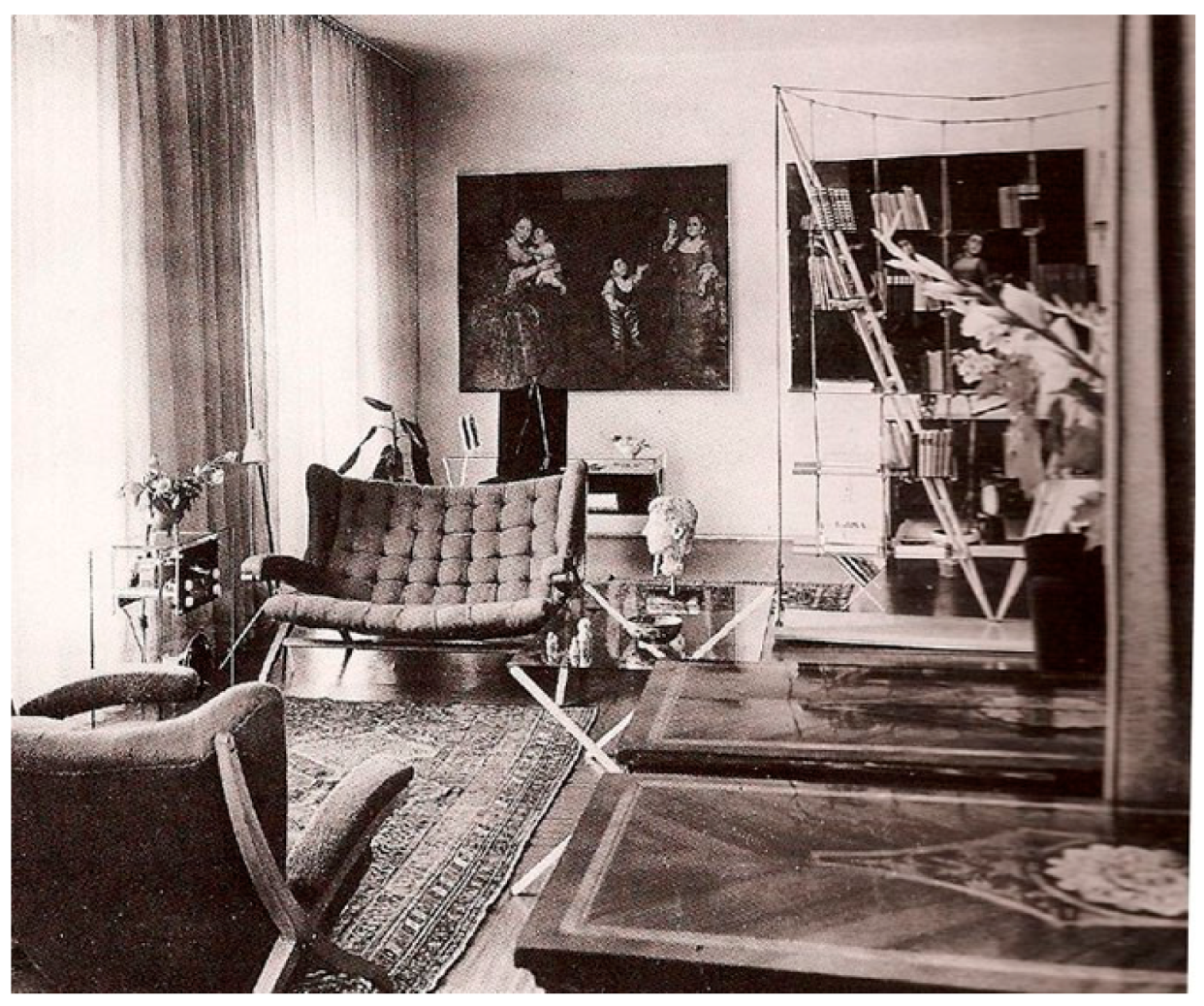

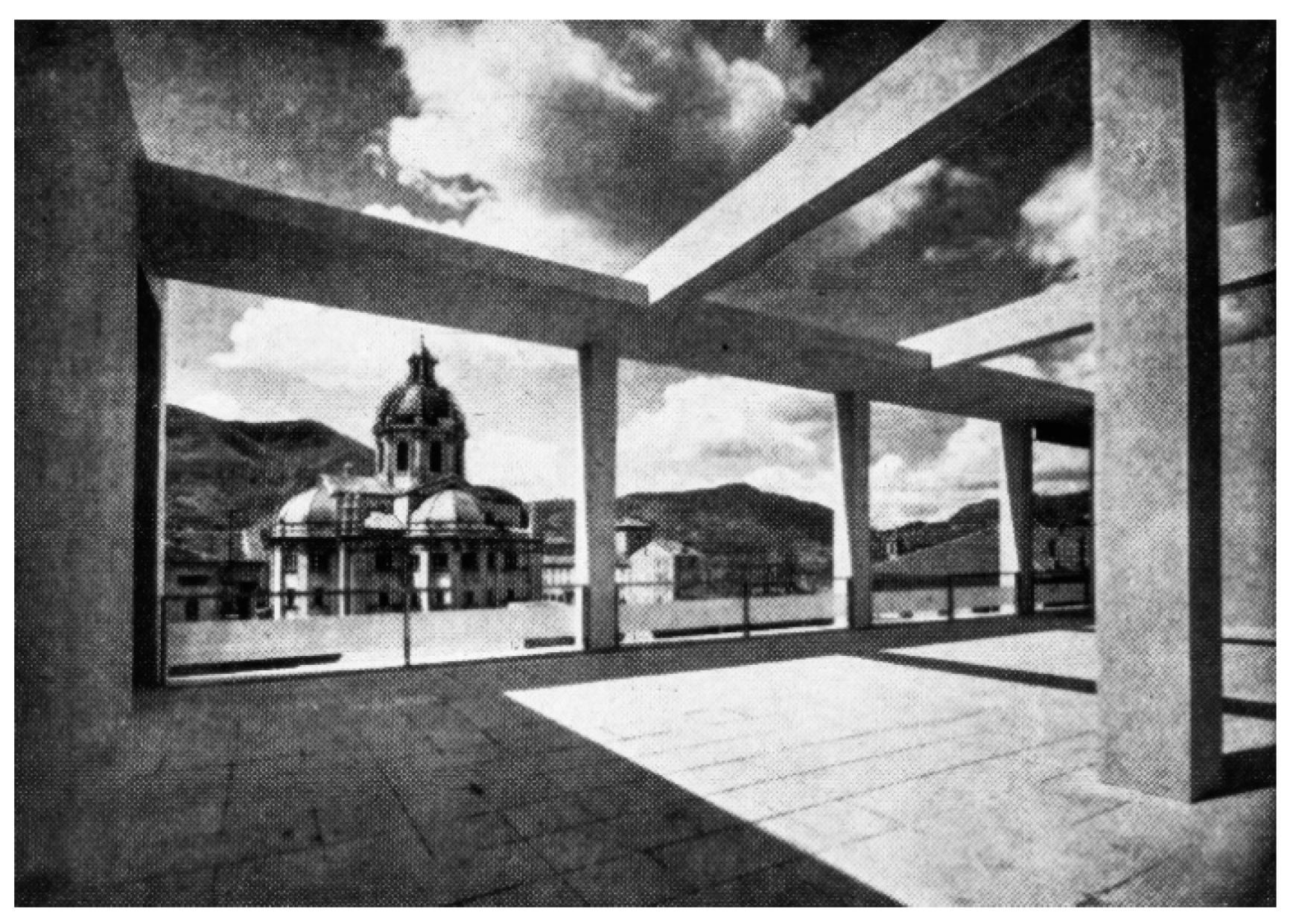

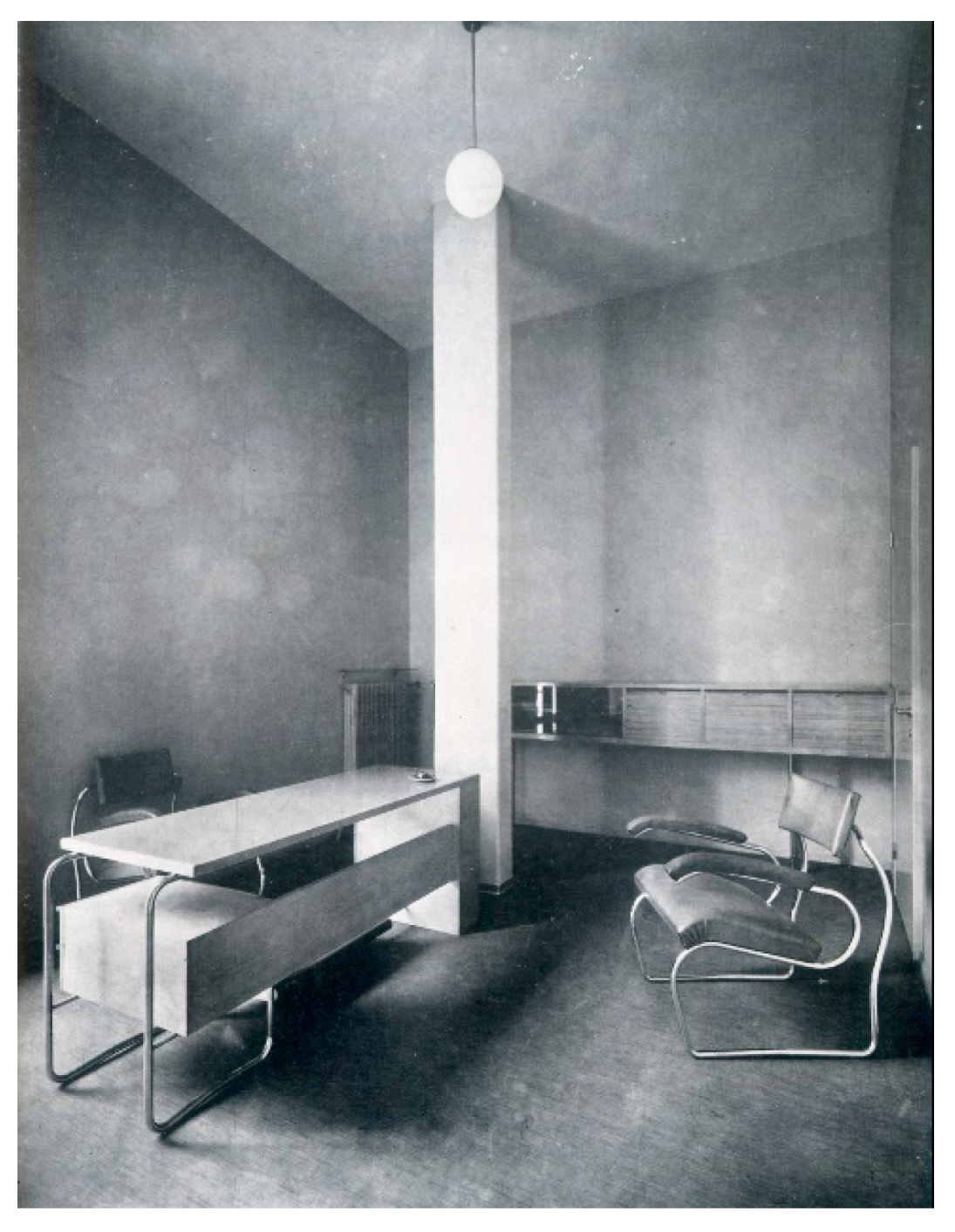

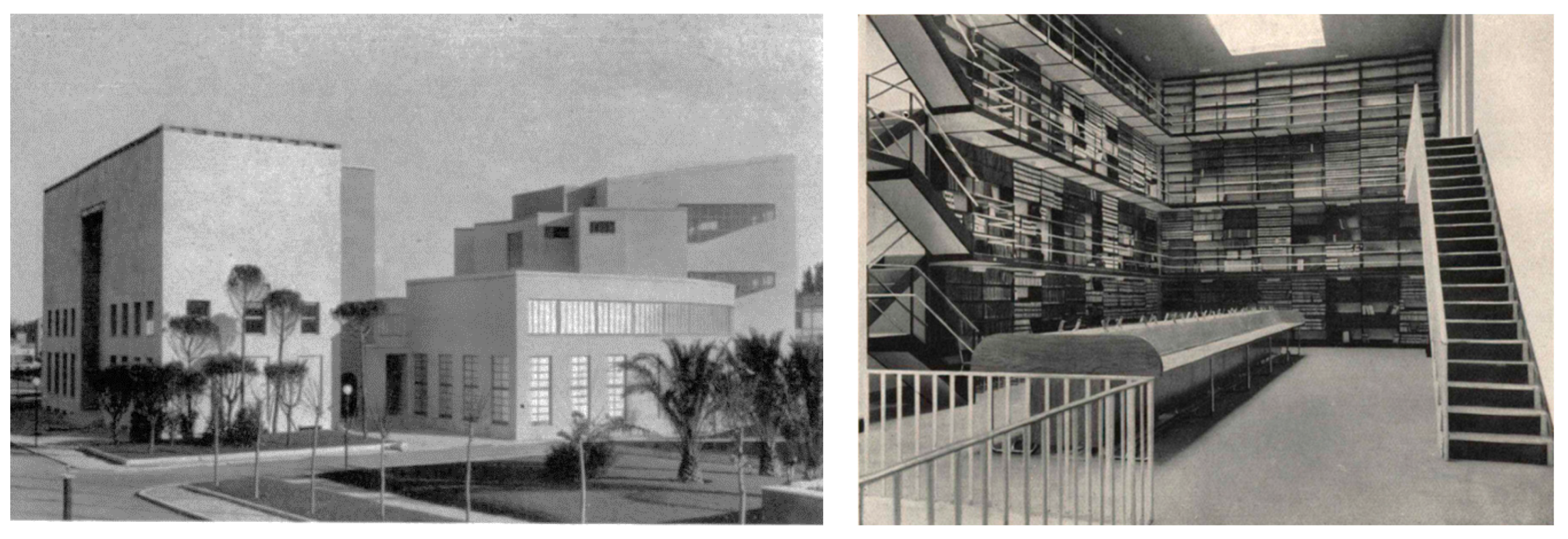

The architects Gino Levi Montalcini and Giuseppe Pagano Pogatschnig, pursuing a global approach, designed the Palazzo Gualino office buildings, the interiors, and the furniture (Turin, 1928–1930) (

Figure 3). The 67 kinds of furniture (tables, chairs, small armchairs, shelves, drawers) were simple and squared, and they were all made using a fir structure and a plywood layer on which the Buxus veneer was applied and then finished with a nitrocellulose spray paint (

Chessa 1930, p. 21;

Capitanucci 2017, pp. 350–51).

The Buxus was well suited to the modernity compositional principles—the absence of decorative elements, right angles, smooth surfaces, pure volume—and to the space’s geometric design where the furniture was an integral part. The furnishings were manufactured by the F.I.P. (Fabbrica Italiana Pianoforti) specialized in the pianos realization and active in Turin since 1917. In 1927, the company was acquired by Riccardo Gualino, who expanded the production to the office furniture sector in conjunction with the Palazzo Gualino construction (

Castagno 1994, p. 54) (

Figure 4).

The linoleum was mainly composed of linseed oil, which was subsequently transformed into a thin coating and then laminated on jute sheets. Patented by Frederick Walton in 1863, linoleum was produced in Italy by the Società del Linoleum of Milan. It was proposed in different models for color and pattern among which were stone, wood, and marble imitations. Linoleum was supported by articles (

Marescotti 1937), advertising, and project publications from the quarterly magazine Modern Building-Linoleum Magazine, founded in 1929.

Due to its aesthetic, chromatic, and hygienic qualities, it has been one of the most appreciated and used materials for both domestic and public environments.

The floorings in homes, offices, hospitals, schools, universities, marine and mountain colonies, and representative buildings were in linoleum; they were classic with stone imitation design and “modern” with geometric surfaces and solid colors (

Bosia 2017, pp. 368–69).

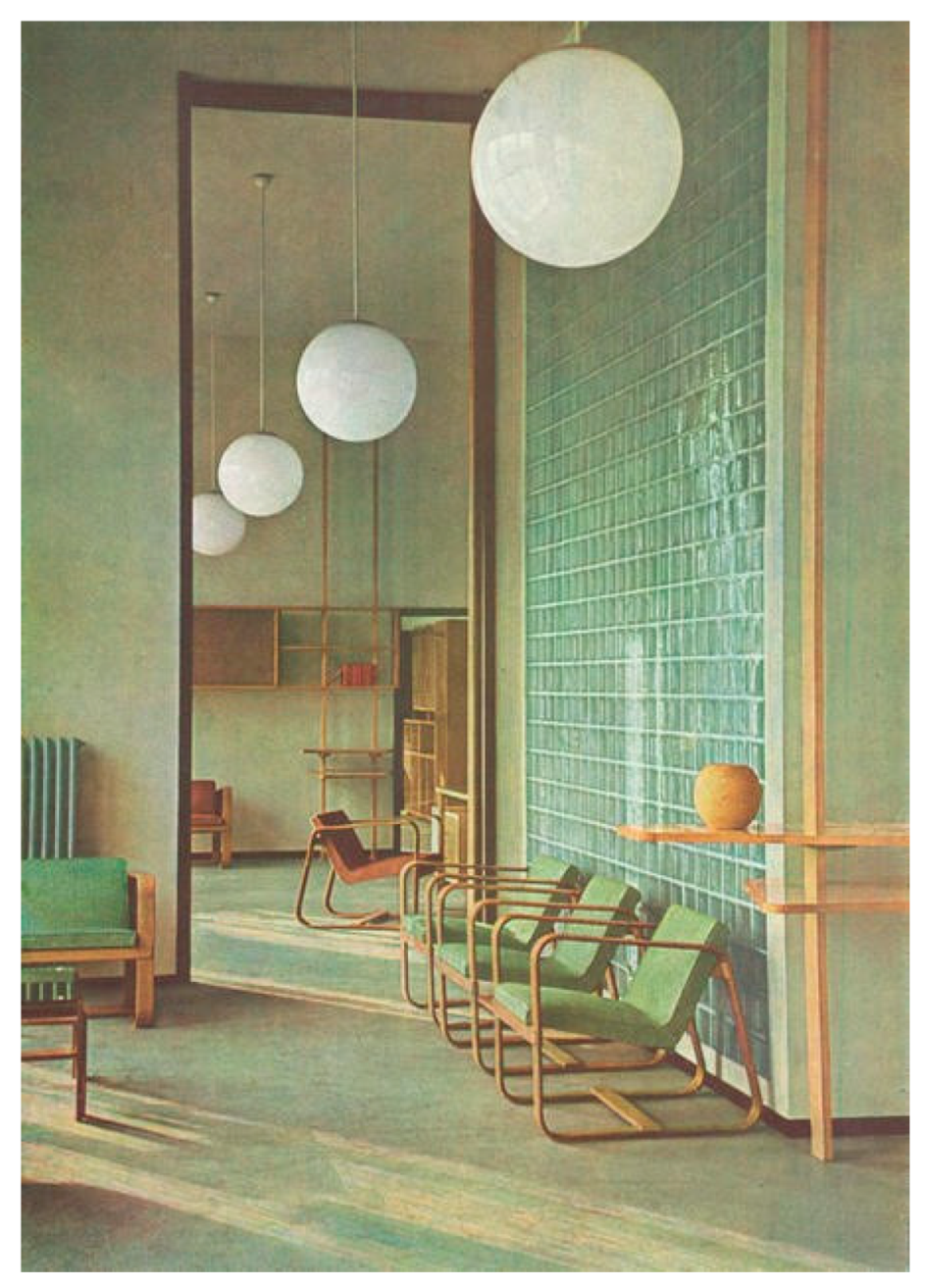

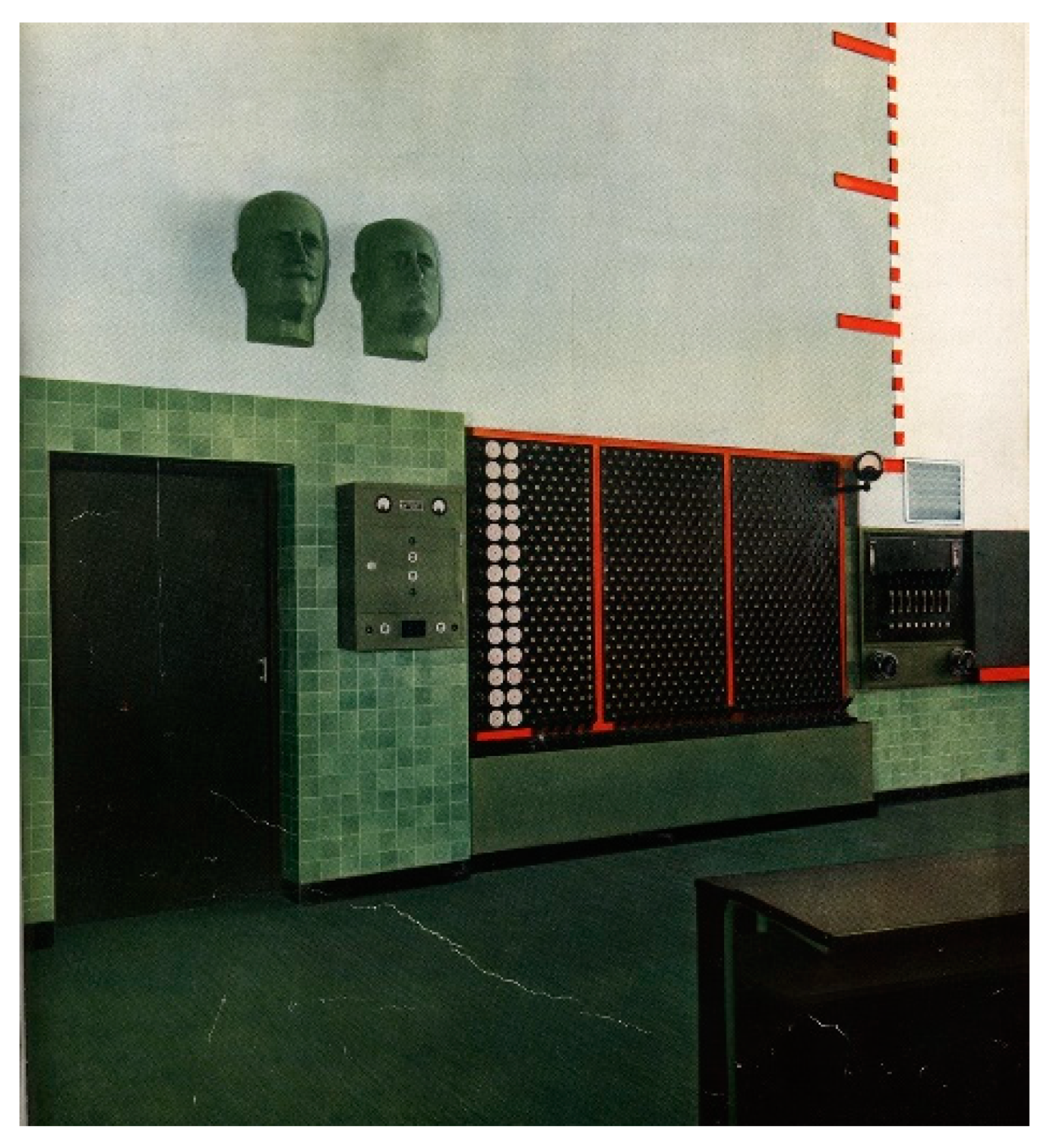

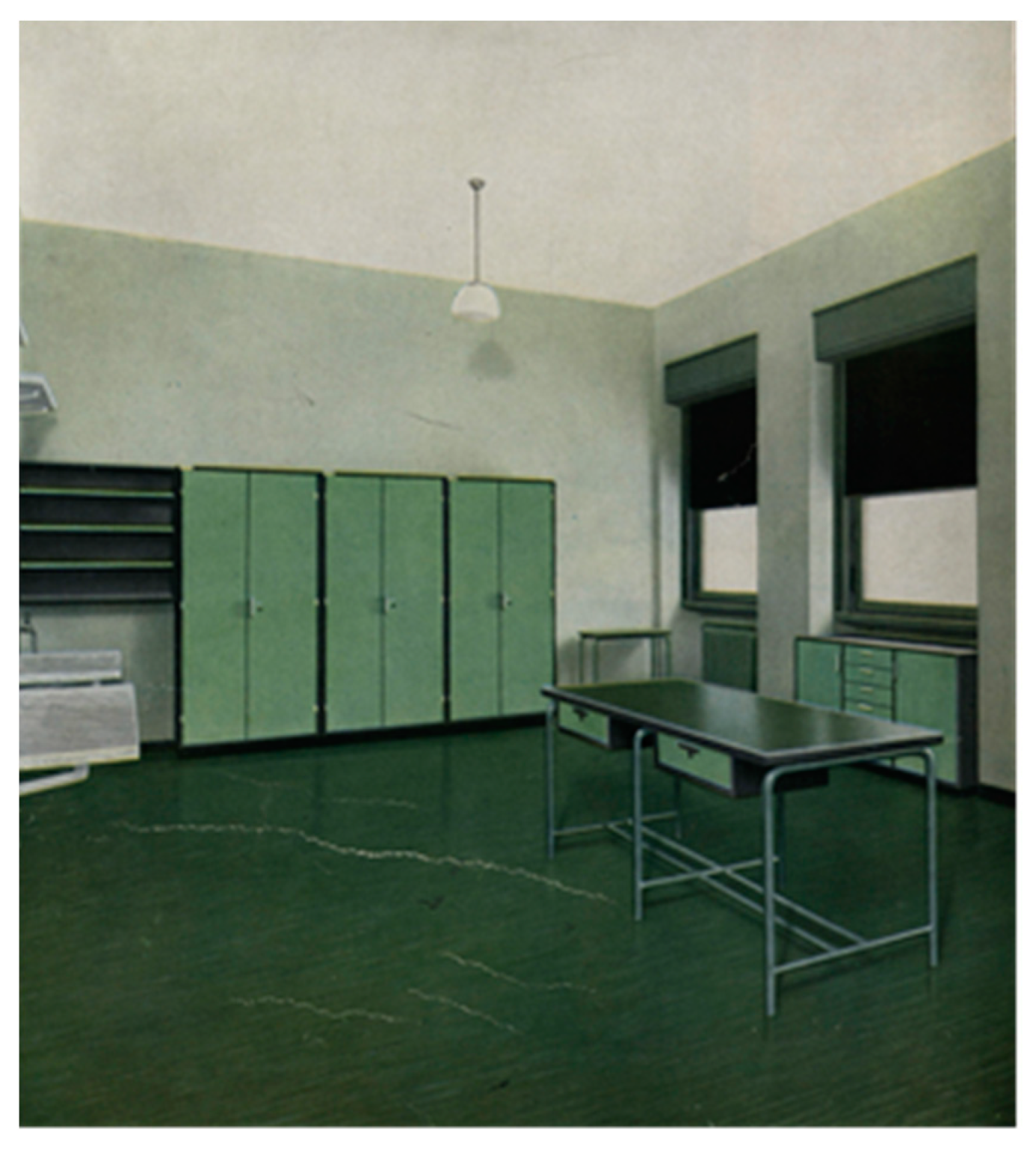

The linoleum allowed for continuous floorings, which enhanced the linearity and the geometries of rational environments and the furniture surfaces and interiors (

Dal Falco 2014, p. 25) (

Figure 5). Finally, there are white metals and glass products, which played a major role in the most advanced figurative and constructive experimentation of architecture and rationalist design.

Initially, aluminum had a fundamental importance in aeronautics but also became essential in other productive sectors including window frames, handles and balustrades, household objects (pots, cutlery), and furniture structures (

Figure 6).

This material was obtained from the Bauxite mines of the Apennines, Istria and Abbruzzo (with the Bayer method using caustic soda) and from Leucite rocks (Blanc process), and—together with alloys and other products that exploited national resources—became an autarchic material par for excellence (

Bernardini and Dal Falco 1992, pp. 105–34).

The cold qualities of stainless steel and aluminum alloys well interpreted the desire for simplicity and “comfort” that distinguished modernity. The application field of light alloys extended to the furniture design in series characterized by the use of the metal tubular, which, starting in the second half of the twenties, developed according to the contemporary foreign examples.

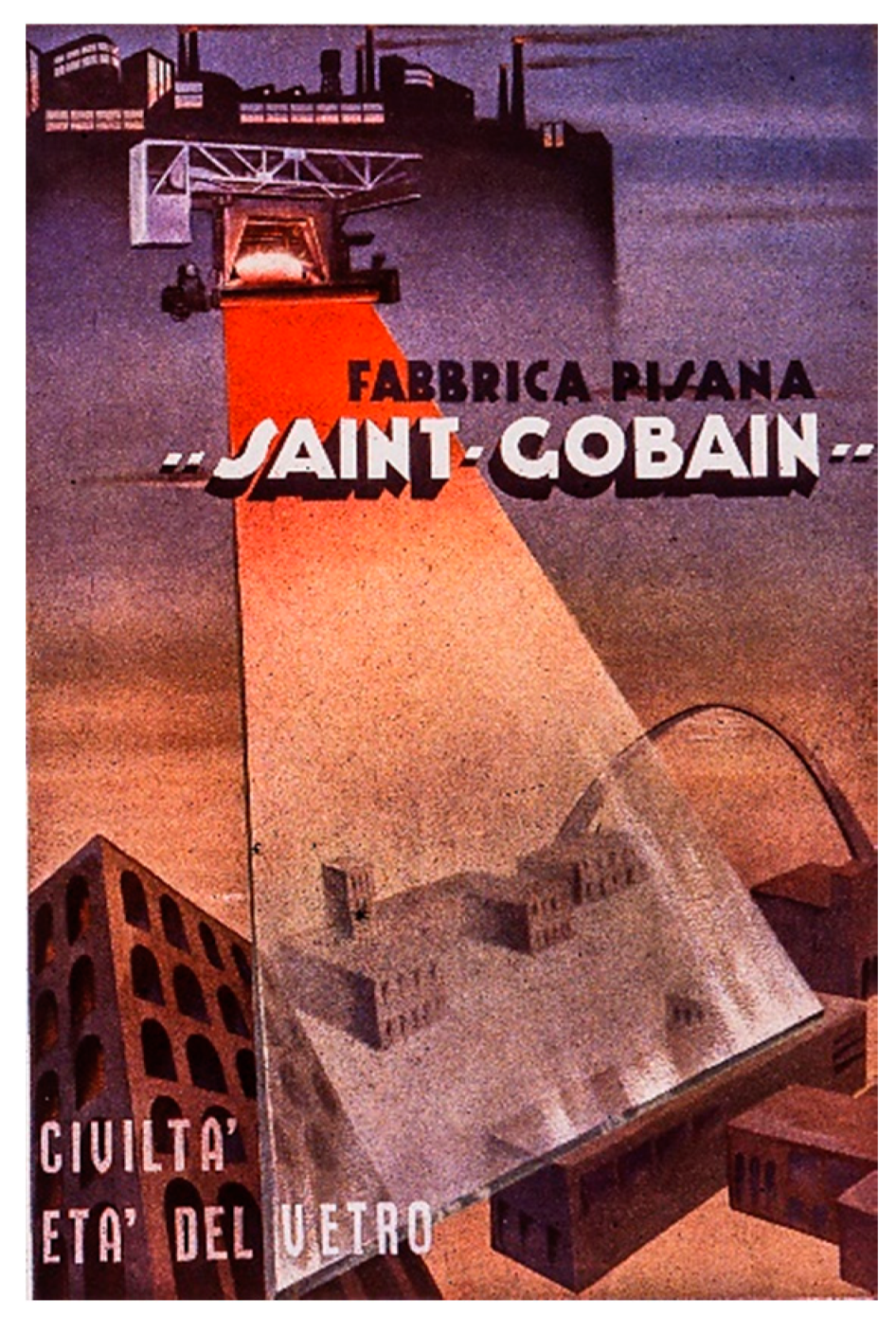

The large-scale use of glass was made possible by the development of new transformation processes. With the Fourcault and Libbey Owens machine systems, the mass production of slabs and heat treatments developed and contributed to widening the field of possible applications (

Figure 7). The qualities of safety crystals, translucent diffusers for glass-block structures, glass fibers, Termolux, and colored dye coatings were thus associated with the rational conception of space and a new general orientation of taste (

Bernardini and Dal Falco 1992, pp. 105–34). In the rationalism works, safety glass became real design materials. Testimonies are the solutions studied by Gio Ponti for the entrance shelter and the balcony doors of the central body in the Palazzo for Offices Montecatini (1936–1938) (

Diotallevi and Marescotti 1939, pp. 21–133).

In the middle of the 1930s, while the use of glass in architecture was well established, its multiple application possibilities in furniture and object design had not yet been fully tested. The creation of “unbreakable” objects developed over a few years with pieces that have since become design icons.

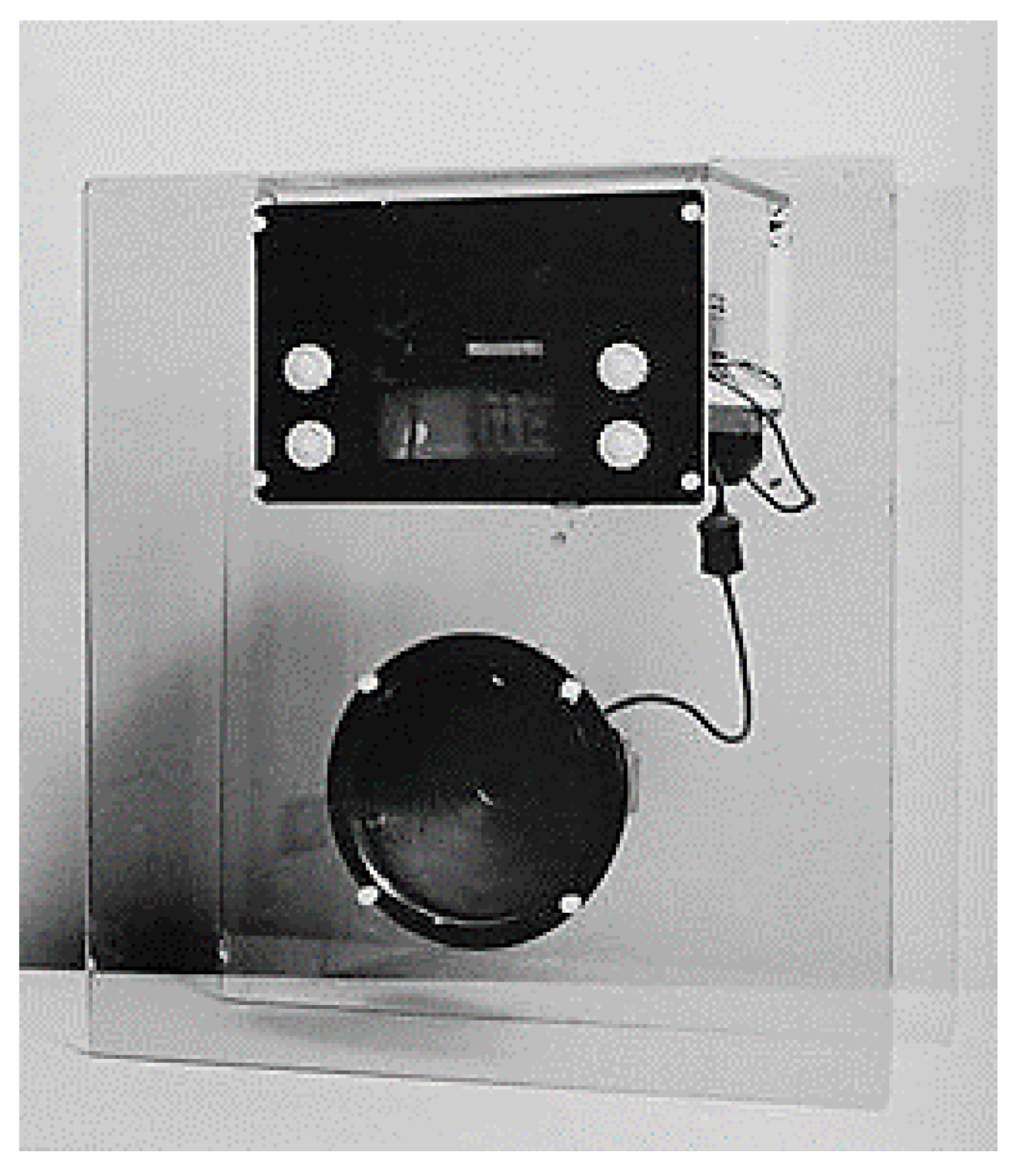

Some examples are the “Veliero” bookcase, a tensile structure in ash, tempered glass, brass, and steel, designed by Franco Albini in 1938 for his house in Via de Togni (

Figure 8) and the radio cabinet where the mechanical parts are exposed between two slabs of Securit, that Albini always designed for the Wohnbedarf competition in Zurich (1940) (

Figure 9).

Therefore, innovative technologies allowed the experimentation of new types. Employed individually or with other autarkic products, they participated in all fields of the project to define new forms. Autarky extended to every productive sector, triggering synergies between science and exploitation of national resources and important research on synthetic rubber that announced the excellent results achieved in the field of polymerization by Giulio Natta in the post-war period.

However, the scientific and technical efforts did not correspond to the ambition of the fascist autarchic plan, and the shortage of raw materials and production technologies brought Italy to face the Second World War with a notable lack of means and resources, a reality that was stubbornly denied by the regime (

Maiocchi 2013).

Obviously, almost all countries involved in the Second World War had to face the problems arising from the scarcity of raw materials with the consequent production of surrogates and the necessity of recycling products and materials. It was a total mobilization that steamrolled any productive sector. In this theme, the historian of architecture Jean-Louis Cohen (2011) curated the important exhibition, “Architecture en uniforme. Projeter et construire dans la seconde guerre mondiale”, which took place at the Centre Canadien d’Architecture of Montreal in 2011, emphasizing the research aimed at developing innovative products and processes with relevant implications for everyday life.

2.2. The Ideological Influence of the Regime on the Rationalism: The Design Research for Modernity of Young Italian Architects

In the autarchic context, research on the greatest Italian rationalism architects was undertaken under the sign of a complex and contradictory relationship with the regime. This relationship was recently revised by the historian Emilio Gentile (

Gentile 2002,

2007), who clearly outlines the prominent mark left by Mussolini on Italian soil.

Between the two world wars, in Italian cities, a political conception materialized; it proposed the model of a new and universal imperial civilization similar to the Roman model of the ancient world. The fundamental ideological elements were the concept of universality over time, considered by Mussolini to be the essence of Romanity and the core of Italianism, and the legacy of the past was manipulated according to the fascist political ideology to create the future.

Cities, architecture, and even objects of this period can be understood through the reinterpretation of Romanism according to fascism, whose primary objective was the regeneration of the myth of Rome and its Empire—a regeneration that, in 1938 and with racial laws, was extended to the grim project of the regeneration of the Italian “race” (

Gentile 2007). On 9 May 1936, Mussolini announced from the balcony of Palazzo Venezia the reappearance of the empire on the fatal hills of Rome, an empire that, with three overseas colonies, lasted only five years (

Rodogno 2006).

Rome had been profoundly transformed under the first fourteen years of dictatorship through a sort of ideological petrification that developed from the Foro Italico to Via della Conciliazione.

It expanded from Piazza Augusto Imperatore to Via dei Fori Imperiali (the archaeological area between Piazza Venezia and Colosseum), and it branched out into the new campus of Sapienza University and the Garbatella district. From there, it was extended to the metaphysic architecture of the E42 area, which began construction when the regime was about to collapse (

Cederna 1979;

Insolera 1962).

Between the two world wars, the urban, architectural, and even the Italian design played a decisive game. The way of conceiving urban space changed, and the architecture became established as a public language. This historical turning point that saw the passage of Rome to international capital found its own set of issues in the relationship between the design culture renewal and the fascist ideology (

Muntoni 2010, p. IX).

The new urban planning of Rome was stratified between the Roman ruins and the baroque churches in the infrastructures, the buildings, the streets, and with the projects of the main young Italian architects and artists of the time—Enrico Del Debbio, Mario De Renzi, Adalberto Libera, Gaetano Minnucci, Luigi Moretti, Giuseppe Pagano, Mario Ridolfi, Mario Sironi, and Marcello Piacentini (

Ciucci 2002). The young architects tried to move the previous generation approach, linked to a rhetorical and monumental style, towards the European modernity. In a context in which fascism gave ample job opportunities to all professionals, the new architects’ education played a central role (

Muntoni 2010, p. XII).

In fact, the search for a modern Italian style was associated with the evolution of the architect’s profile, a professional who had to exercise skills related to general culture, techniques, and arts. This profile was named “the integral architect” and was defined by the training programs of the “Regia Scuola di Architettura di Roma” in 1919 by Gustavo Giovannoni and Manfredo Manfredi, and later on by the Engineers and Architects Register in 1923 and 1925 (

Ciucci 2002;

Dal Falco 2017, pp. 28–35).

The specificity of the idea of integral architect is therefore linked to the foundation of the Schools of Architecture achieved by integrating the Schools of Engineering with the Academies of Fine Arts. Most of the credit for this initiative is due to Gustavo Giovannoni (1873–1947), historian, critic of architecture, engineer, architect, and urban planner who concluded a process that started at the end of the nineteenth century in Italy and in Europe. Giovannoni’s training project was original and ambitious because it integrated the technical scientific culture with the humanities and the arts, the latter cultivated only in the Institutes of Fine Arts. The teaching of design was based on this synthesis, and an operative study of the history of architecture was considered the basis for the profession of architecture.

Giovannoni’s project had a precise cultural identity, especially if we compare it with other European schools of the period, for example, with the Bauhaus born in the same year of the School of Rome (1919). One of the main differences lies in the fact that the Bauhaus theorized the exclusion of historical studies from its curriculum. On the contrary, for the School of Architecture of Rome, the knowledge of the past was the indispensable condition of architectural education.

According to the Giovannoni theory, all the disciplines had to converge to the “architectural project”, which corresponded to the organic profile of the integral architect, the synthesis of technical, artistic, and classical culture skills. The new didactic program—and consequently the integral architect—led to the rebirth of an authentic style of modern Italian architecture.

The new figurative and technical constructive language, although it considered the international scenarios, had to be cohesive with the climate and customs of national life and had to reinterpret the forms of the past in a modern way. Therefore, the renewal of Italian architecture could not ignore tradition, and the integral architect had to know the millennial stratifications that characterize the Italian cities and Rome in particular.

Giovannoni left the direction of the School of Architecture in Rome to Marcello Piacentini (1881–1960), academic of Italy as well as an architect and urbanist. Piacentini’s interest (

Piacentini 1930) in international experiences did not influence his cultural project; a return to the principles of classicism that should have substantiated the spirit of modern Italian architecture in a national and autarchic sense manifested. His proposal for an updated and polished monumentality devoid of decorative excesses without abolishing arches and columns was repeatedly disputed by Giuseppe Pagano Pogatschnig (

Pagano Pogatschnig 1938) and Edoardo Persico (

Persico 1933,

1934). This passage is fundamental for understanding the characteristics of Italian modernity, which was conditioned by the policies of the regime and autarky but also by the peculiar training guidelines established for architects (

D’Amato 2017, pp. 33–46).

The integral approach of Italian architecture and design emphasized—on the one hand—the ability to design at all scales “from the spoon to the town” according to the principles of the modern movement, and—on the other hand—the knowledge and reinterpretation of historical heritage.

This approach was used from urban planning to the design of interiors and furniture so as to create houses, schools, and hospitals with morphological and constructive features that balanced modernity and traditions in old cities, newly founded cities, and colonized territories. The integral architect had to be able to design the planning scales and be informed about historical, technical, and artistic issues.

University educated young people who joined the regime asked for new criteria in the design of public works. At the beginning, the most retrospective academics prevailed, proposing a monumental style close to the “cult of the lictorian”. Later, thanks to competitions (1925–1940) for public works (public housing, student houses, postal buildings, auditoriums, ministerial offices, stations, bridges), the best and youngest architects—among which were Libera, Mazzoni, Michelucci, Moretti, Pagano, Ponti, Ridolfi, Terragni, Banfi, Belgiojoso, Peressutti, and Rogers—completed important works linked to everyday life needs. Some of them changed their political opinions, moving from adherence to fascism, to the frond, and finally to the opposition (

Melograni 2008).

The architect’s talent responded to the “Zeitgeist” according to experimental figurative languages consistent with international modernity despite the insistent calls for a monumental conception. The Northern Italy architecture, particularly the Lombard one, has always been considered lighter and closer to the modern movement compared to what prevailed in Rome (

Melograni 2008). Franco Purini pointed out that in Rome’s architecture of the thirties, there were strong three-dimensional and volumetric values with a widespread use of the rounded corner that was different from the sharp corners of the Milanese buildings.

In public and private residential buildings, the inspiration from Mendelsohn’s architecture is constant. Naturally, the realization is carried out through typological, structural, and formal criteria based on a classic taste more or less accentuated at the discretion of each architect (

Spesso 2017). Other elements that allow us to understand the importance of the relationship between architects of this period and ancient Rome are the vaulted structure, the curved space, and the sinuosity that can be seen in certain projects (

Muntoni 2010, p. XV).

In Italian modernity, these complex and sometimes contradictory elements coexist with references to both classicism and the modern movement. The relationships developed by the Italian architects with international modernist currents constitute a historical-critical crux.

Going deeper into this issue would require reference to a vast body of literature, and its complexity makes it impossible to treat herein as exhaustive as it goes far beyond the scope of this article.

What should be clear, however, is that Italy was not isolated, and European and North American architectural experiences were known through magazines such as Casabella, Architettura, and Domus and through important books such as Architettura d’oggi by Marcello Piacentini (1930) and Gli Elementi dell’architettura funzionale by Alberto Sartoris (1932, 1941), in which the most important modern architectural accomplishments of other countries were illustrated and discussed.

The complexity mentioned above is reflected in the constructive characteristics of the buildings. In fact, in Italian modern architecture and design, autarkic materials were used according to a conception of modernity in balance with tradition. The rational forms were made with new industrial types combined with the traditional vertical and horizontal coatings, such as marble and stone slabs (

Poretti 1992). With a technological mix of traditional and innovative materials, the architecture and furnishings were influenced by the autarky that ranged from the early twenties to the early forties of the twentieth century, when it turned into a war economy. The search for a balance between tradition and innovation is evident both in compositional and constructive aspects. In

Section 2.3, we see how the different architectures are linked by common themes.

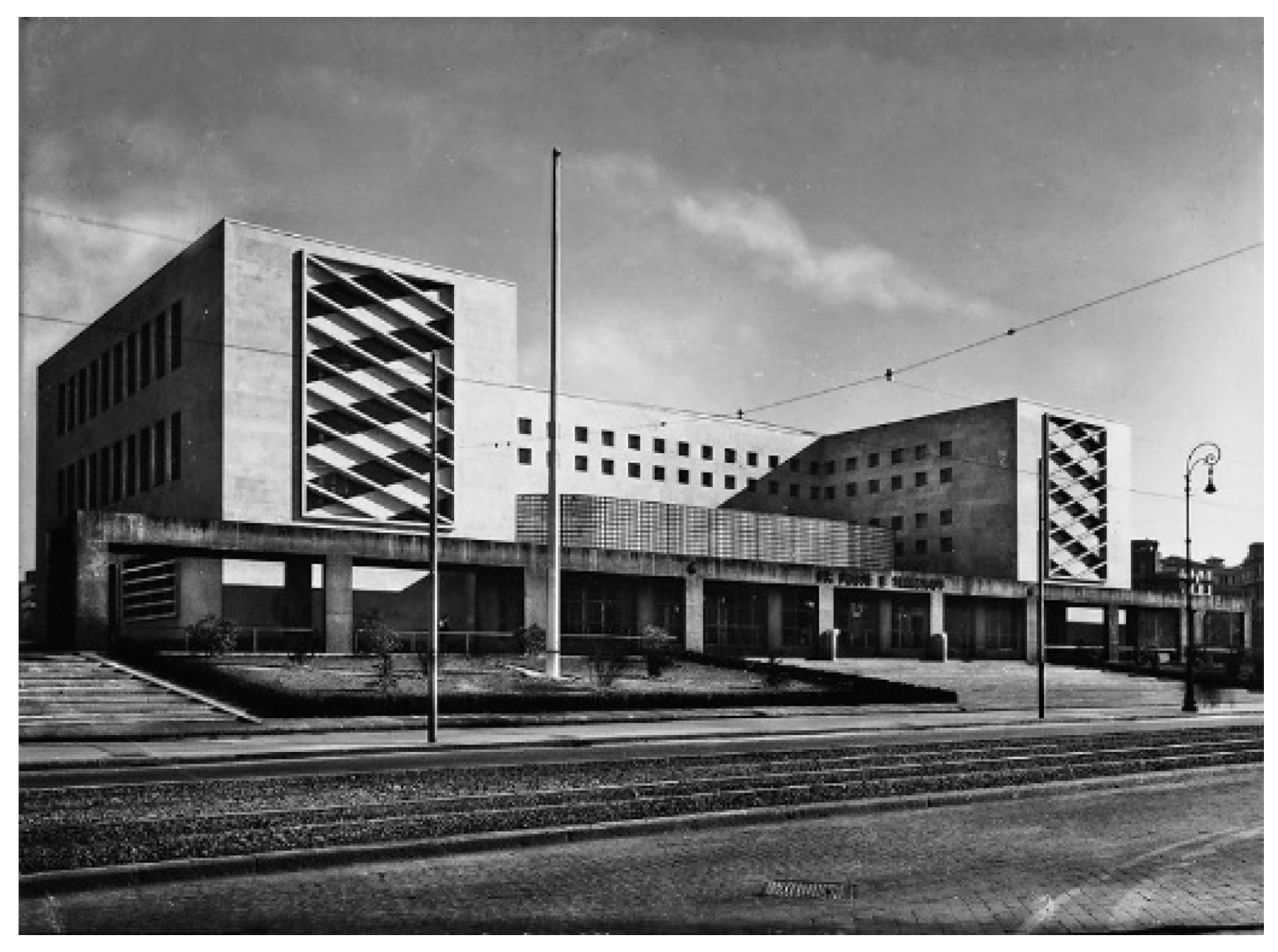

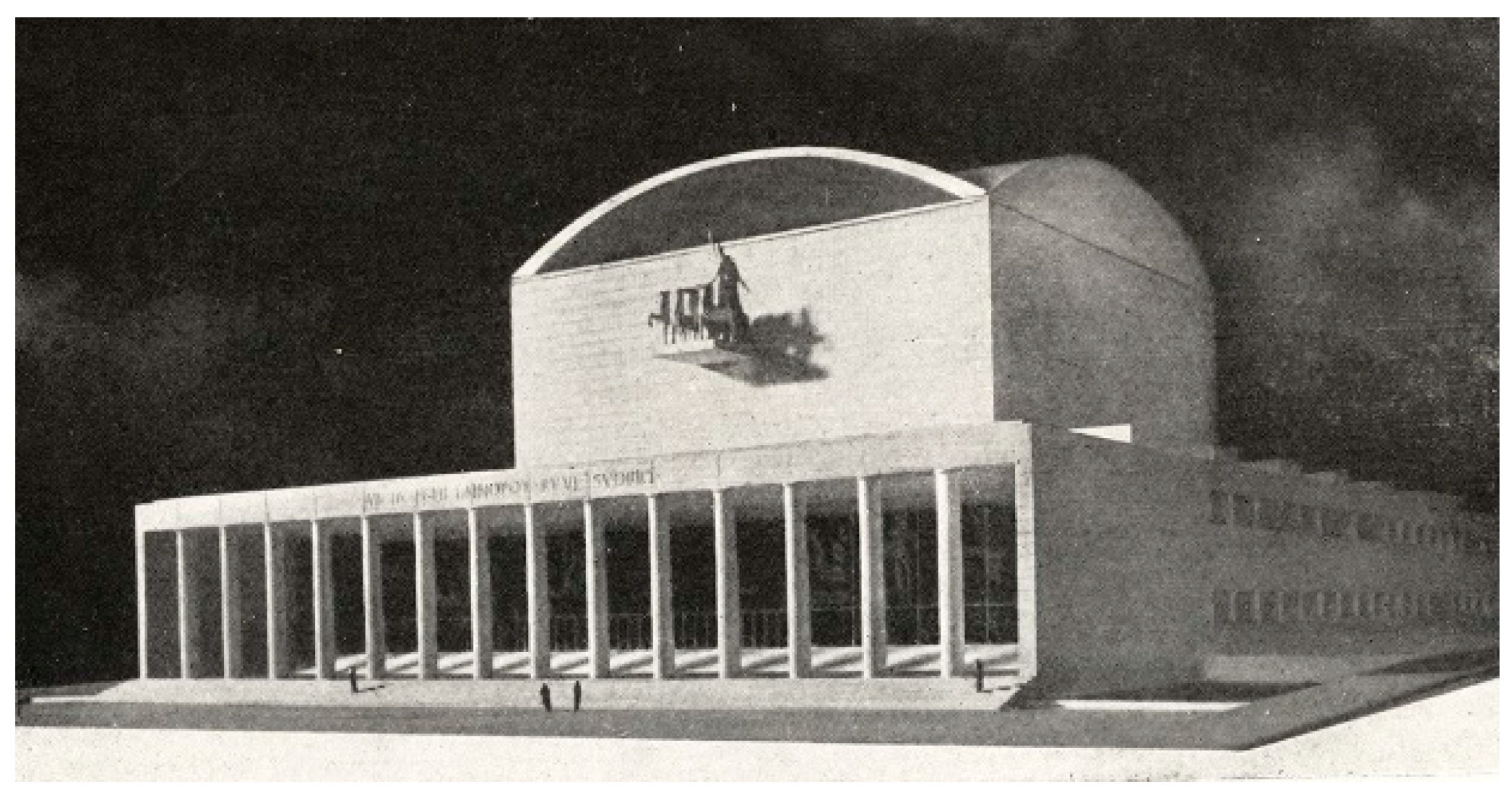

Among the first buildings built in Rome that can be considered modern are the Post Office buildings (1933–1935). These are four very different representative buildings of the new metropolis (

Muntoni 2010, p. 270). The buildings by Adalberto Libera and Mario De Renzi and by Mario Ridolfi and Giuseppe Samonà have a non-rhetorical and unconventional character. The relationship with the historical pre-existences and the compositional inspiration of Roman and Baroque architecture (stairways, drums, concave-convex rhythmic alternation) is subtended by a skillful technological mix made of reinforced concrete structures and stone cladding. The Viale Mazzini building designed by Armando Titta, a Turin architect, retains the stereotypical trait of the regime’s public building (

Poretti 1990, pp. 5–9).

The Post Office building by Libera and De Renzi is a symmetrical and massive C-shaped volume in which an elliptical skylight is fitted with opaline glass and metal profiles. A portico clad in dark porphyry flanks the building, connecting it to the street by a stairway. On the short fronts, two large openings illuminate the back stairs with a unique game of diagonally woven grids. The back is a plate of “stone-concrete” pierced by small square openings (

Dal Falco 2002, pp. 129–48,

Poretti 1990, pp. 39–84) (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11).

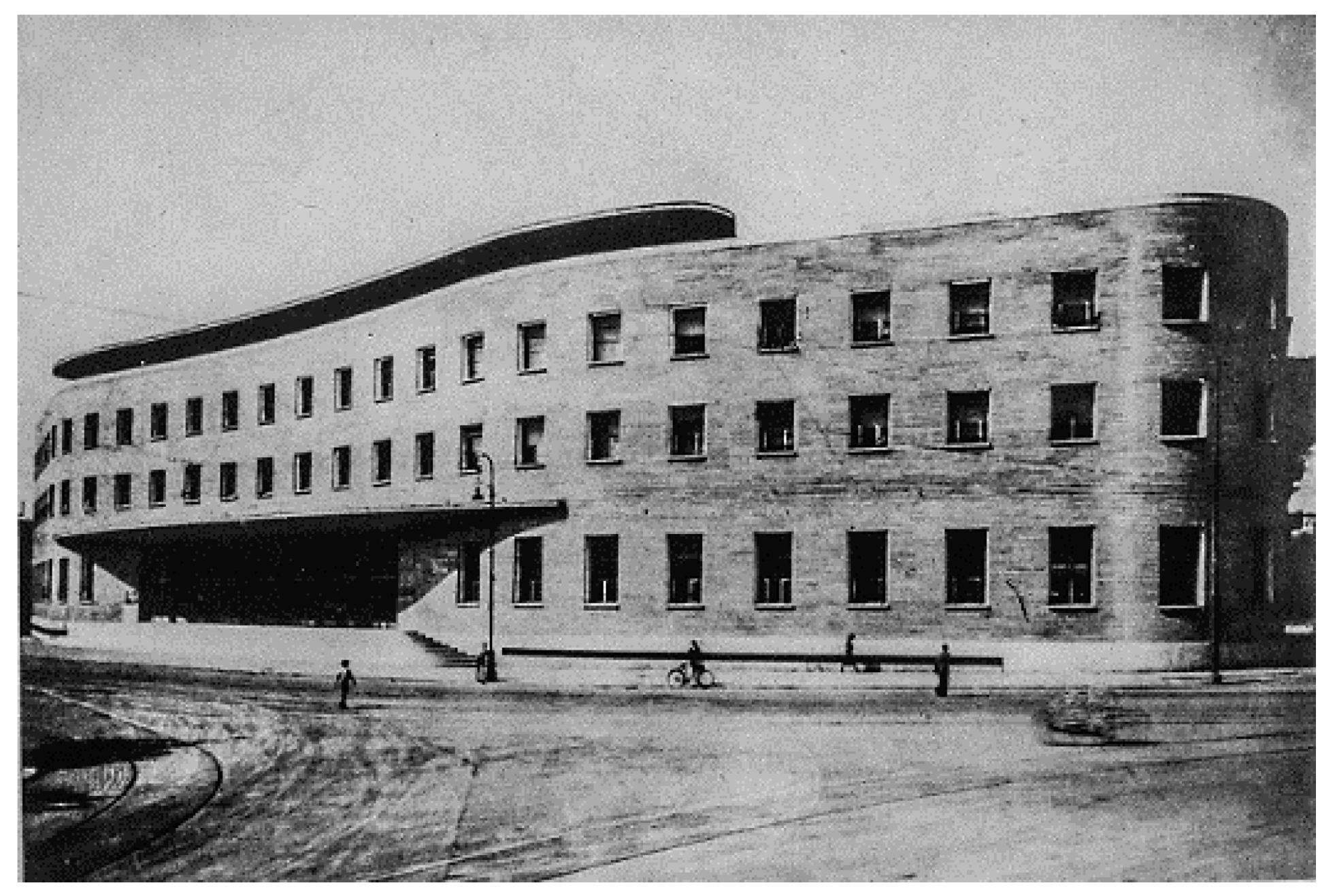

Also, the Post Office building by Mario Ridolfi presents a symmetrical but curvilinear and continuous structure with a concavity in the central part, and the ends are resolved with two rounded corners. A shelter is detached from the roof, which underlines the sinuous structure of the building. The building plastic qualities are enhanced by a continuous travertine cladding on which there are rectangular windows at regular intervals (

Dal Falco 2002, pp. 149–81;

Poretti 1990, pp. 85–123) (

Figure 12).

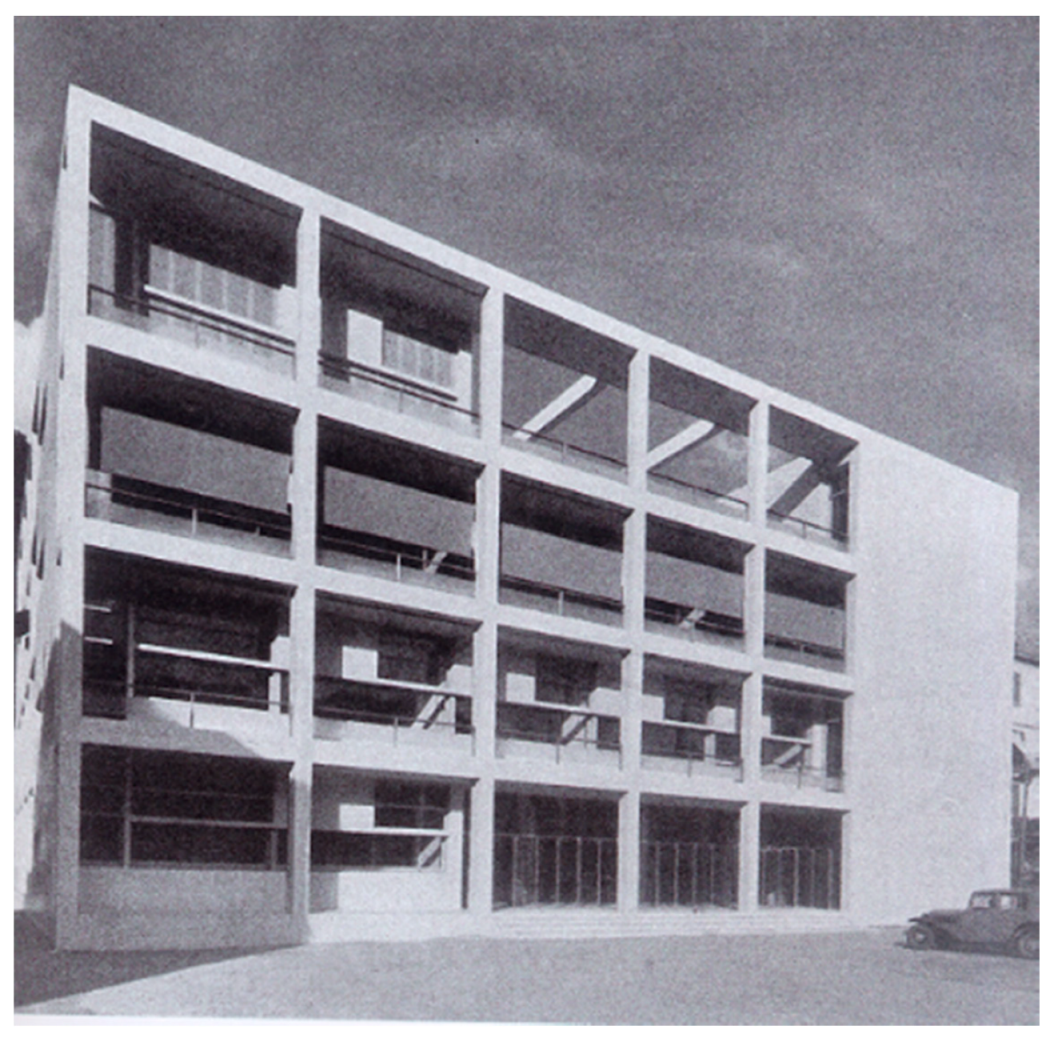

The Post Office building by Giuseppe Samonà is composed of two V-wings that close in a convex corner and a parallelepiped placed on the secondary front. The base is characterized by large windows placed between the reinforced concrete pillars covered with Samolaco gneiss slabs while the upper facades are covered with travertino (

Dal Falco 2002, pp. 185–201;

Poretti 1990, pp. 125–62) (

Figure 13).

These three architectures, which have been the subject of important studies, are examples of the particular tradition and innovation mix that characterized the Italian production between the two world wars. Moreover, they are significant to understanding how, despite the conditionings of the regime and autarky, the young Italian architects succeeded in pursuing the Italian modernity way with the aim of changing lifestyles in the habitat, both private and public.

2.3. Architectural Themes: A Unique Technological Mix

The Italian architecture of the period is therefore unique compared to modern architecture. Even if there are analogies between the Italian and the European experience, the Italian rationalist architectures are characterized by a strong innovation without precluding ties with history or references to Romanity and the typical figures of Italian architecture, such as the Renaissance loggia, the bell tower, and the internal court. Even the constructive elements were characterized by a particular material and technological mix consisting of traditional materials, innovative products, and technologies. Starting from this assumption, it is possible to define architectural themes that unite important buildings of the period: structure and closing diaphragms, coverings in stone materials and Klinker, flat roofs, and iron frames.

The structural theme was exemplified in the facades that, with their order and their materiality, represented meanings and communicated messages related to the historical context.

This theme is linked to the use of isolating materials, which, as mentioned in

Section 2.1, constituted an important productive sector responding to the autarchic principles. The reinforced concrete allowed the rationalization and reorganization of the interior spaces and the design of facades free from the structure. In some exemplary cases, as in the Loggia del Casa del Fascio (Como, 1933–1935) by Giuseppe Terragni (

Marcianò 1987;

Saggio 1995) and in the elevations of the Palazzo delle Poste (E42, 1939–1941) by Banfi, Belgiojoso, Peressutti, and Rogers (

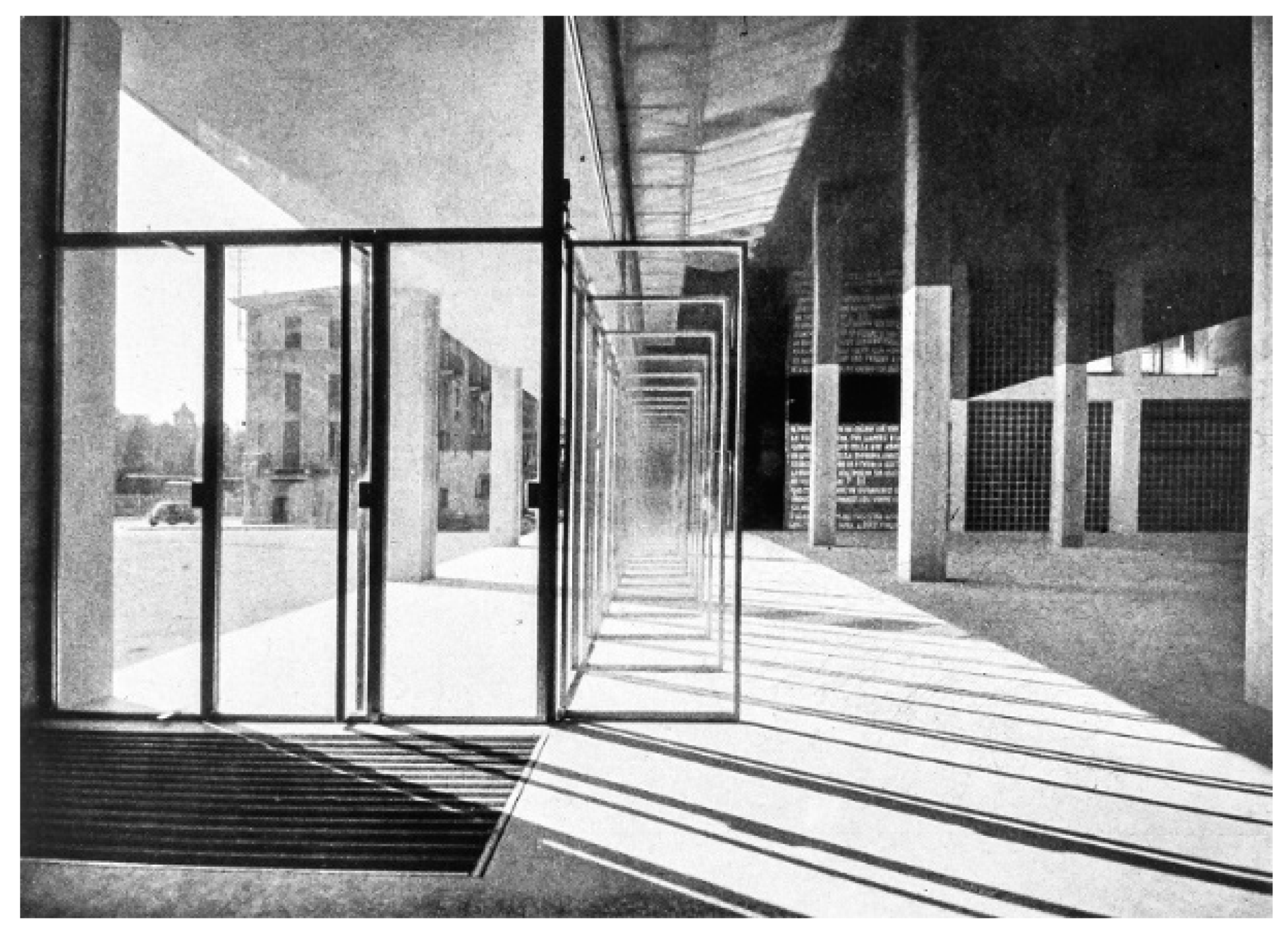

Danesi and Patetta 1976), the reinforced concrete skeletons covered in marble slabs are on an advanced plane in respect to the perimeter walls (4).

This motif was used to build porticoes and bases whose large windows were divided horizontally by black-painted iron frames.

In the Casa del Fascio, the search for a new spatiality correlates to a poetic interpretation of the light. The Terragni building is a pure prism made of four different fronts, alternating smooth walls and pillar and beams grids that create light and dark effects (

Arrigotti et al. 1936) (

Figure 14).

The practicable flat roof is partly covered by a glass-block skylight that illuminates the double height of the internal courtyard. The opalescent light matches the Botticino light stone cladding.

In the Casa del Fascio, the search for a new spatiality correlates to a poetic interpretation of the light. As in French and German architectures (5), Terragni experimented with new glass curtain walls and glass blocks. For this reason, the Casa del Fascio is considered the manifesto of the use of glass products (

Artioli 1989), an emblem of modernity that simultaneously illustrates transparency and fascist ideas—the control from the outside to the inside and vice versa (

Ciucci 2002) (

Figure 15).

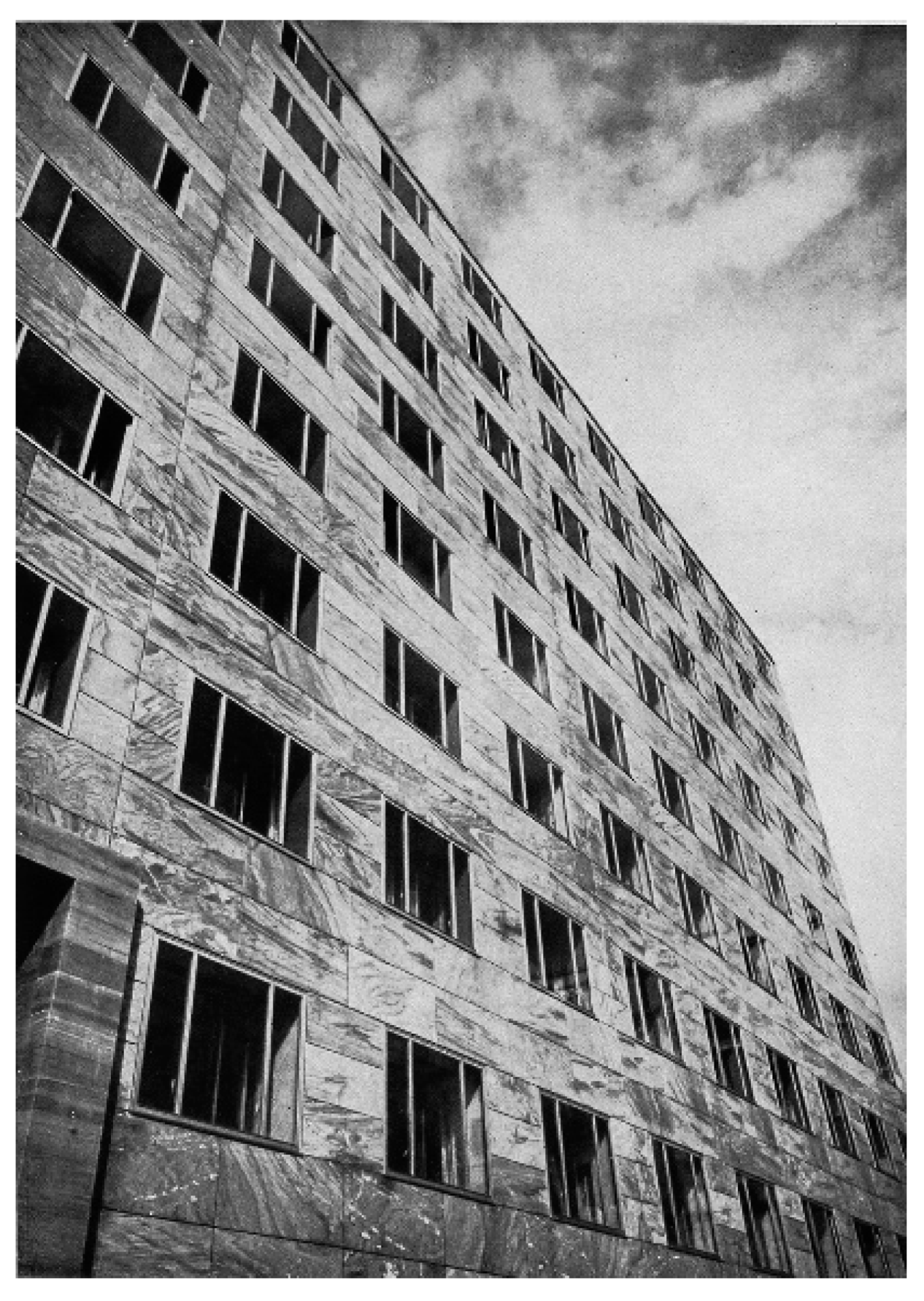

The structure coincided with the facade plan. In the Montecatini office building (Milan, 1936–1938) by Gio Ponti, the skeleton is a perforated box of reinforced concrete on which the Cipollino Apuano marble cladding was applied (

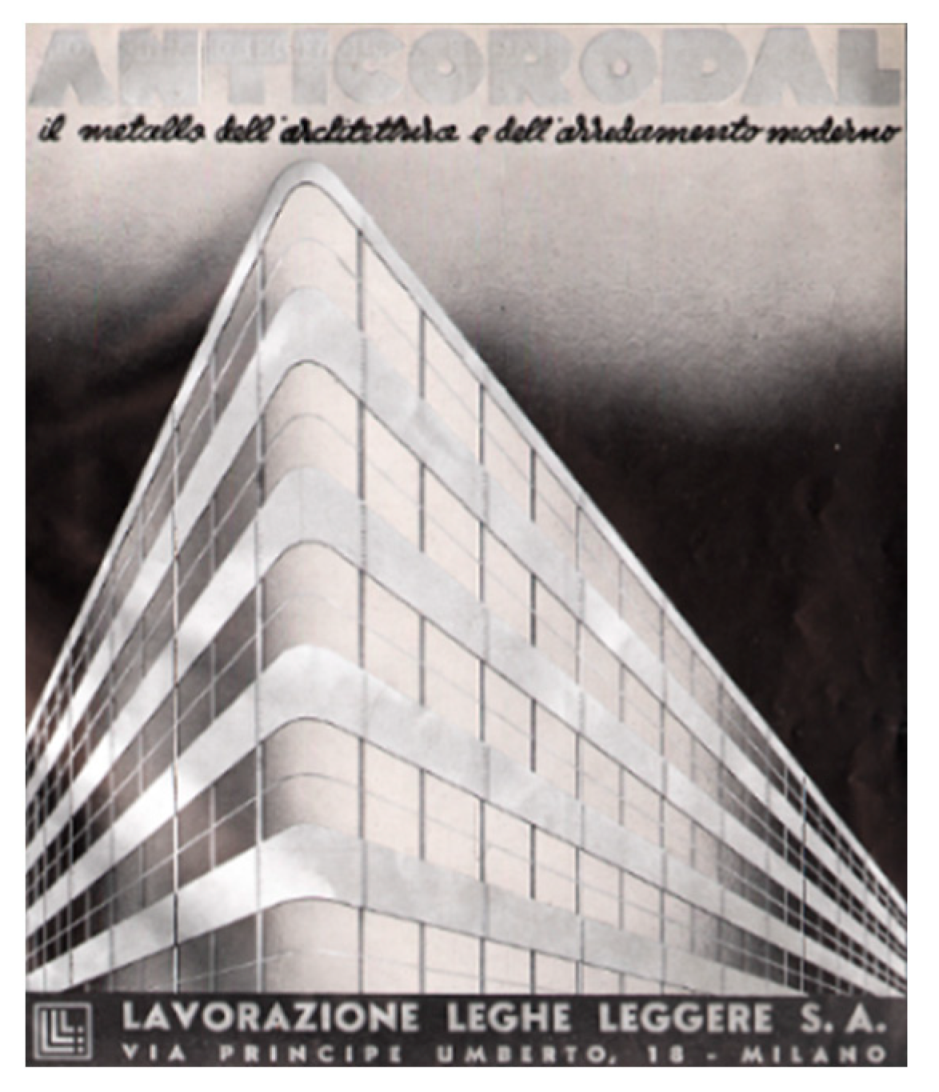

Diotallevi and Marescotti 1939, pp. 21–133). The frames in light aluminum alloy (Anticorodal) were placed on the edge of the cladding, generating a great structural image (

Irace 1977).

The stone cladding is a central theme in the architecture of Italian rationalism and strongly identifies its style. The pure volumes of the new modern aesthetic necessitated clear surfaces and symbolic materials consistent with autarkic needs. Marbles, stones and granites were extracted from ancient quarries like those of the Apuan Alps in Tuscany and were used in thin slabs.

The construction procedures were experimental and worked with innovative techniques. Marbles and granites were used to cover the exteriors, usually white, while for the interiors, colored stones were preferred (

Poretti 1992,

2013). Stone materials were coupled with petrifying plasters and ceramic and glass mosaics whose industrialized production allowed the creation of durable and economic decorative surfaces that recalled ancient Byzantine mosaic arts (

Bernardini 2017, pp. 159–72).

Moreover, the Carrara or Travertino marble blocks were used for paving or for architectural details—frames, jambs, thresholds, and sleeves thick up to 8 cm with rounded edges, assembled protruding from the edge of the facade and worked with slight slopes to dispose of rainwater.

It is to be noticed that the use of stones in the foreground entailed the careful study of textures and details—colors, dimensions, arrangement of elements, joints, surface treatments, and installation systems adopted are all elements that generate perceptual values.

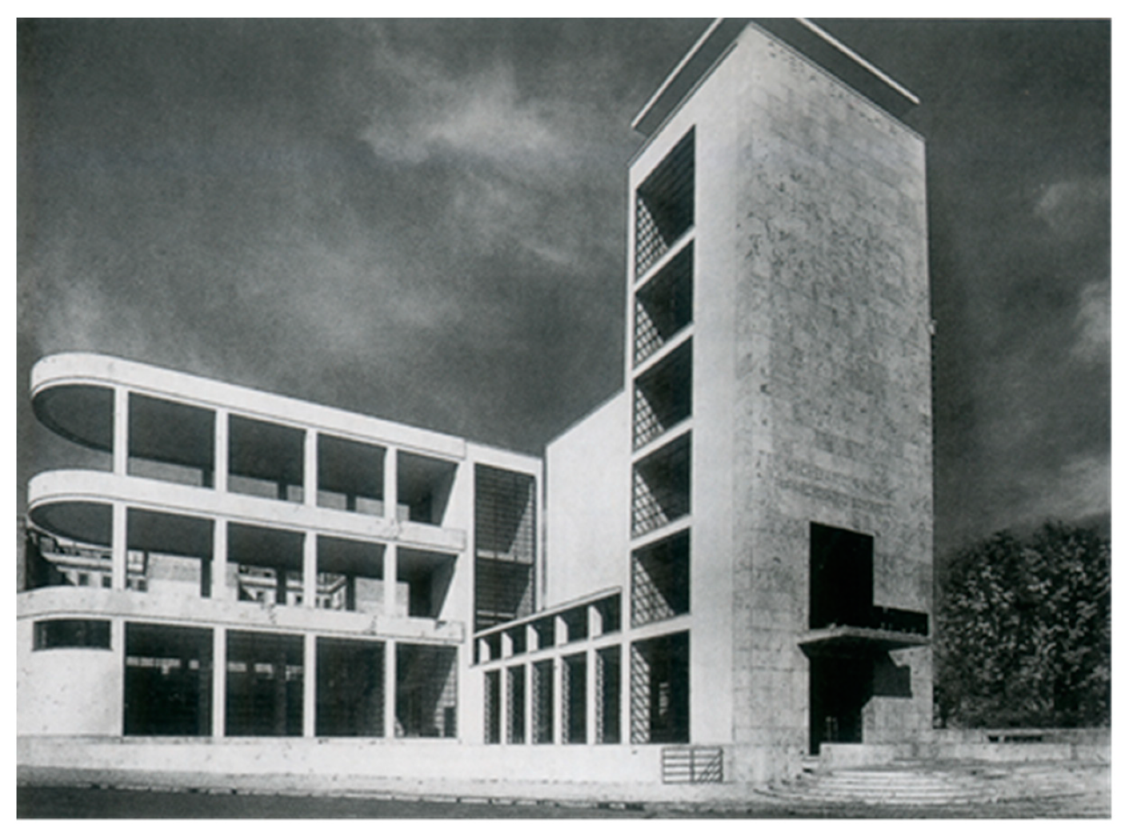

Beside the coverings of the mentioned buildings, the coverings of two architectures that are beacons of the Italian rationalism are emblematic, namely the coverings of the House of the G.I.L. (Gioventù Italiana Littoria) (1932–1937) and the House of Arms (1933–1936) by Luigi Moretti.

The House of the G.I.L. is articulated into distinct volumes characterized by a complex of linguistic elements that are wisely intertwined.

The tower, an emblematic reference to a bell tower, has a tapered front coated with travertine slabs on the square. A fixed and continuous glazed surface wraps the corner between Via Induno and Largo Ascianghi from the base up to the top. The motif of horizontal partitions created by the iron frames is typical of the architecture of this period and of Moretti in particular.

The reinforced concrete structure is visible on the glazed side facades and on the block of gyms devoid of any cladding.

From the construction drawings, one can grasp the care devoted by Moretti to the design of the tower’s covering. The 370 rectangular slabs of variable size were divided into 19 types. Moretti drew a filing cabinet consisting of 171 pieces numbered in alphabetical order specifying size and thickness (

Figure 16). This attention to the construction detail and the technical drawing is typical of Rome’s School of Rationalism, and it is particularly present in Moretti’s projectual research (

Architettura 1941,

Marconi 1941, pp. 361–73).

In the Foro Italico’s House of Arms, the theme of cladding—made of Carrara’s statuary veined marble—is developed in an exemplary way. The rationalist box is interpreted as a marble, modern, and monumental organism. All facades are designed in detail, and any shaped block is numbered.

Special pieces are designed to obtain rounded corners. The marble plasticity of the building is accentuated by the continuity among the base, the access flight steps, and the external flooring (

Marconi 1937, pp. 437–54.) (

Figure 17).

The third theme is the flat roof. Flats roofs were associated with the concept of squared and clear facades—practicable terraces, sometimes used as a solarium, or glass-block skylights (

Figure 18).

In the Congress Palace (1937–1942, 1953) by Adalberto Libera built for the E42, the roof of the congress hall is flat and practicable. The terrace is designed as an open-air theater and furnished with 210 fixed benches, covered with marble and carefully placed in relation to the flooring texture (

Palazzo delle Feste 1938) (

Figure 19).

A fourth theme concerns the design of window frames in iron or aluminum alloys, such as Anticorodal, based on the component standardization and experimentation with innovative assembly methods for profiles (

Figure 20). As mentioned, since the end of the 1920s, the production of white metals was strongly boosted. Their use on a large scale responded to the combination of economic factors and new technological design requirements—window frames, balustrades, handles, and furniture in curved steel or aluminum tubing with plywood shelves, sometimes recovered in linoleum or Buxus (

Dal Falco 2017, pp. 316–24). In the late 1930s works, there was a greater use of wooden frames than of metal profiles. On the other hand, the preparation for the war conflict limited the iron for military use. In a short time, the great season of design experiments that characterized rationalism in the mid-thirties ended.

2.4. Design Themes: Metal Furniture and Standard Production

As mentioned above, the autarkic plan outlined by Mussolini on 23 March 1936 at the National Assembly of Corporations was mainly addressed to the restructuring of metallurgical, mechanical, and chemical industries, but it was implemented in all productive sectors, from construction to design and fashion. It was also supported by articles published in the main journals of the period (Architettura, Casabella, Domus, Rassegna di Architettura, Lo Stile nella casa e nell’arredamento).

In addition, new specialized magazines were born whose main scope was the dissemination of characteristics and applications of innovative materials (Alluminio, Il Vetro, Edilizia Moderna. La Rivista del Linoleum, L’Industria nazionale, Rivista mensile dell’autarchia).

Since the end of the twenties, in his magazine

Domus, Gio Ponti published numerous appeals for the development of national production in the field of decorative and industrial arts (

Ponti 1928,

1935,

1936) to which architects, engineers, technicians, and professionals responded (

Ardissone 1936;

Panseri 1936).

The debate on autarchy intensified in 1938 when experts from all productive sectors wrote articles (

Pica 1937;

Nunzi 1938), and there was a growing advertisement of national food, textiles, and pharmaceuticals with technical columns dedicated to autarchic building production.

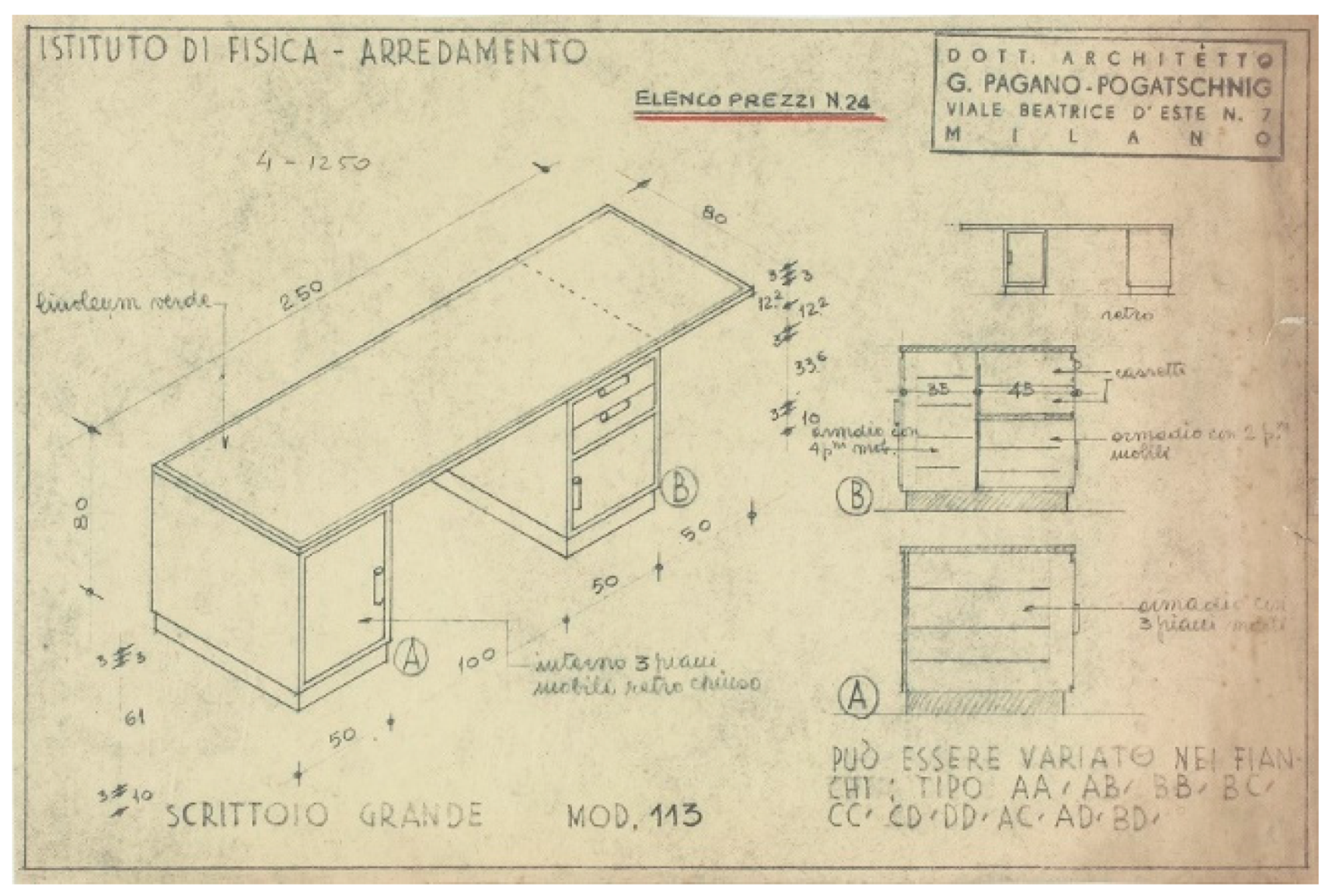

The new integral architect should design—or at least find solutions—for the interior and the furnishings. Metal materials were the most innovative testing field with a strong interest in foreign productions both by architects and specialized firms.

The Italian furnishings followed the fashion of the time and were inspired by the Bauhaus models and in general by the German production that began in 1925 with the Wassily armchair by Marcel Breuer. This new way of design found its formal and structural reasons in the culture of the curved tubular profile (

Marchis 1998).

As is known, the new European tendencies were shown in international exhibitions that some Italian architects had visited or known through some magazine. In the design of Italian furniture, one can find many compositional and constructive elements typical of the furnishings of 1927’s “Ausstellung die Wohnung Stuttgart” coupled with the idea of human scale standards that was accomplished by Le Corbusier’s “Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau” (1925).

The knowledge of foreign production in this field (in particular of furniture made in Switzerland and German) is proven by the relationships established between the company Colombo, created in Milan in 1919, and the Wohnbedarf of Zurich, founded by Sigfried Giedon, Werner M. Moser, and Rodolf Graber in 1931. Wohnbedarf models were, among other authors coming from the Bauhaus, designed by Breuer.

The Hungarian architect also designed for the companies Thonet and Embru, which in turn were linked to Wohnbedarf by a contract between the parties (

Tropeano 1998;

Crachi 1997). In this context, Colombus was one of the leading companies in the production of Präzisionsrohr and sold the Wohnbedarf furniture in Italy (

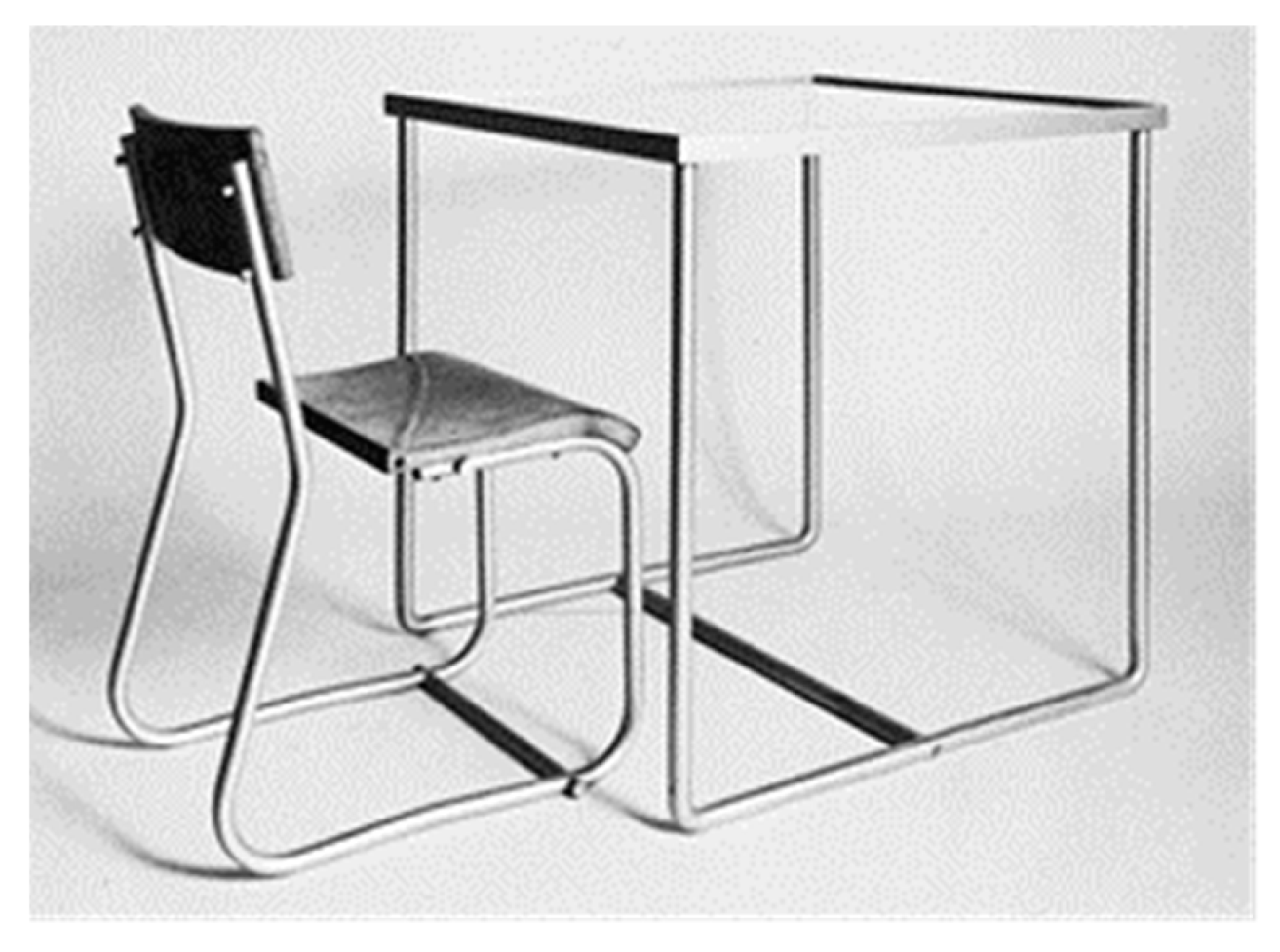

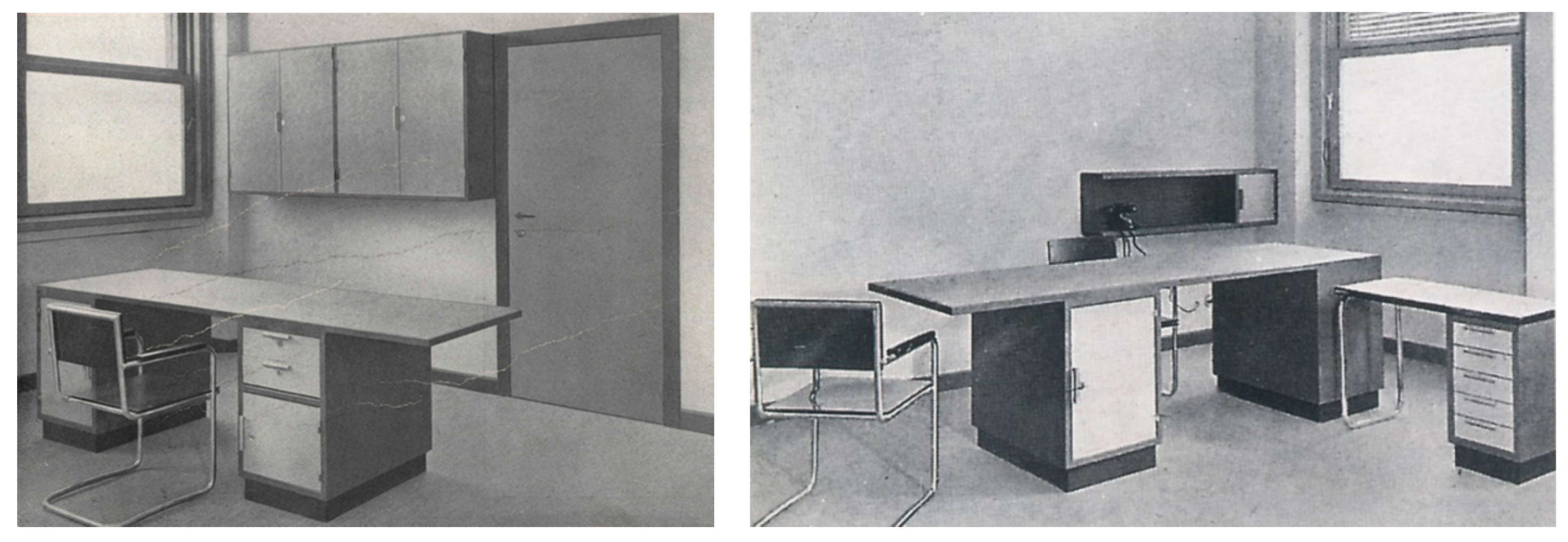

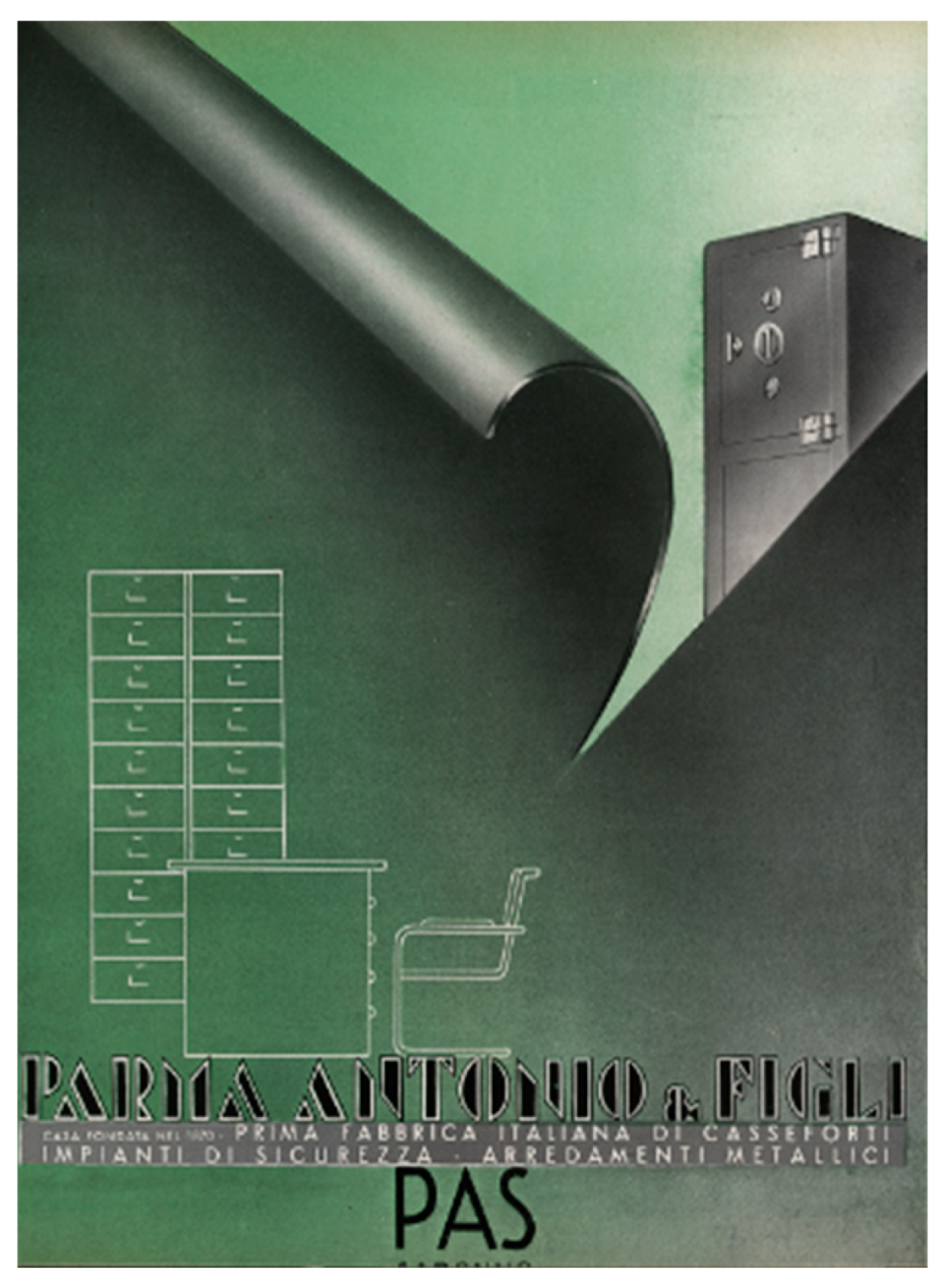

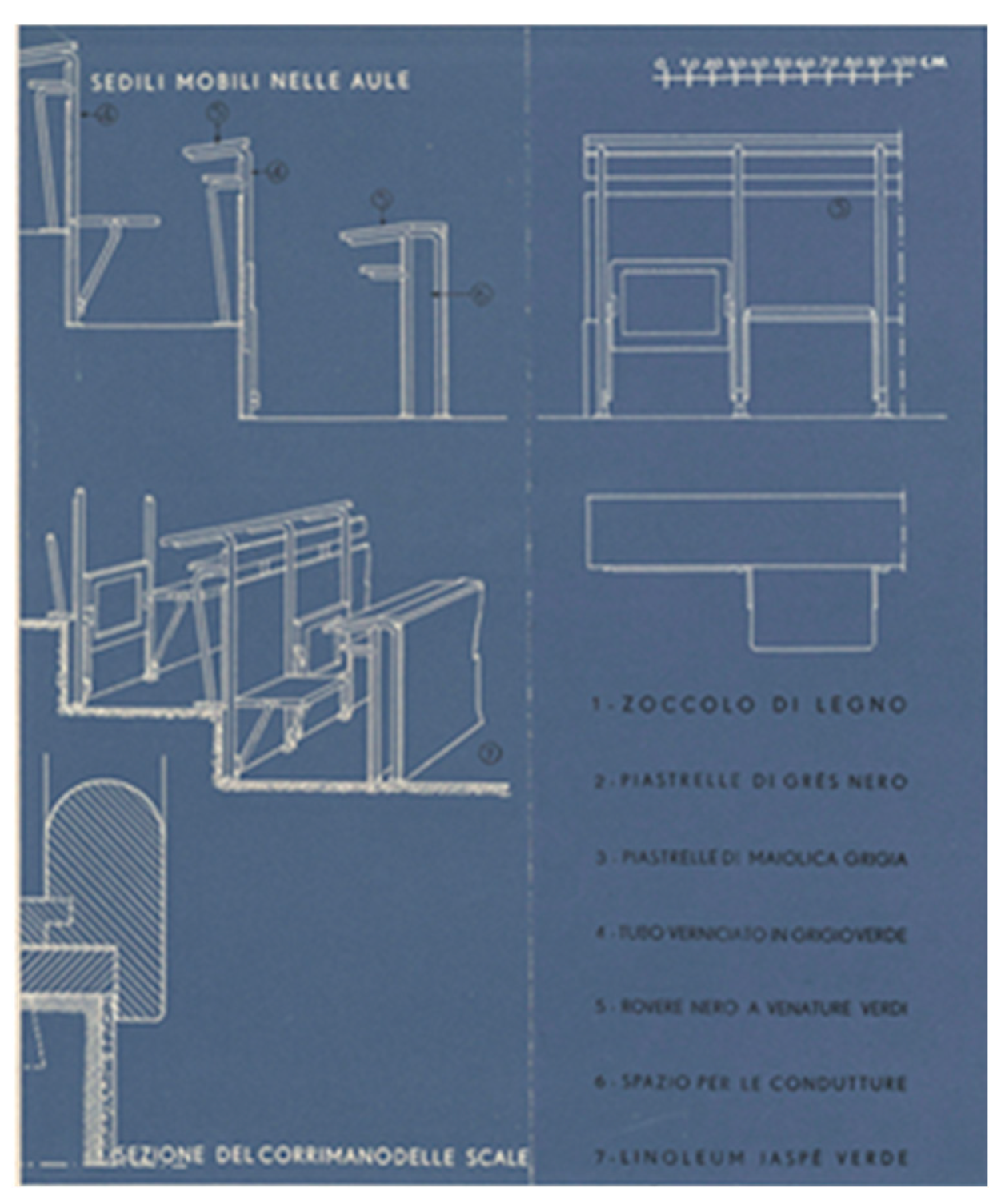

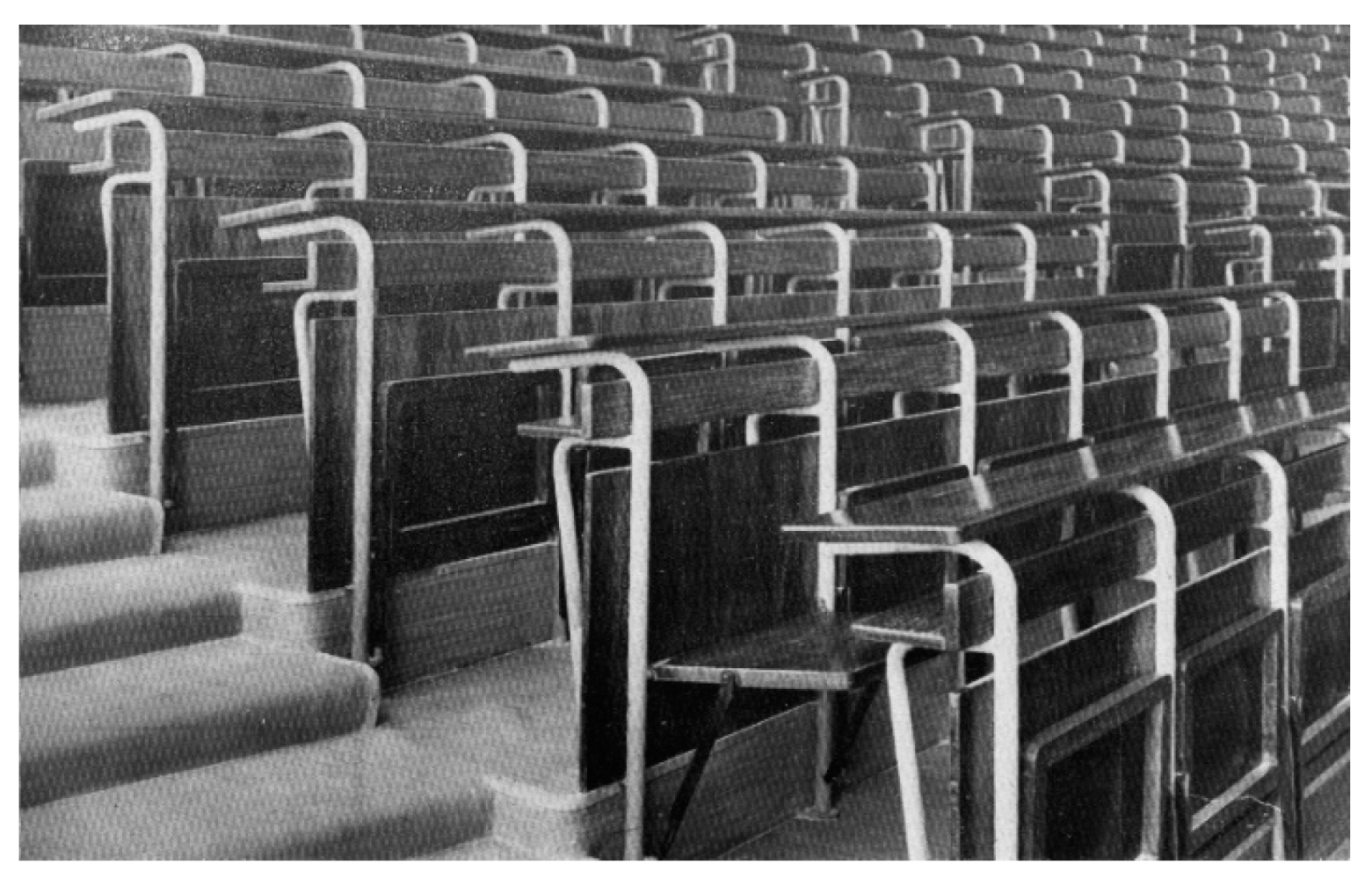

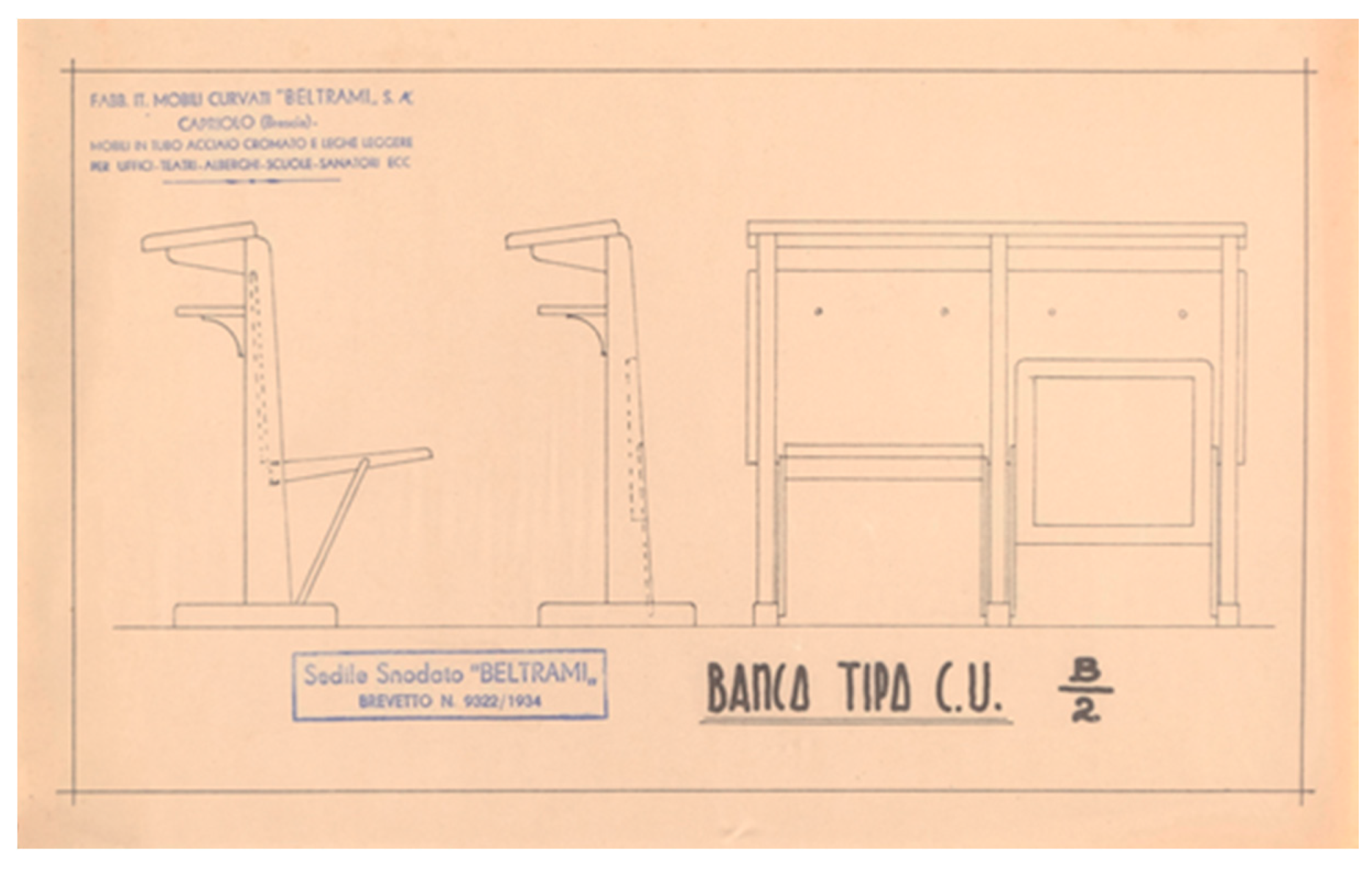

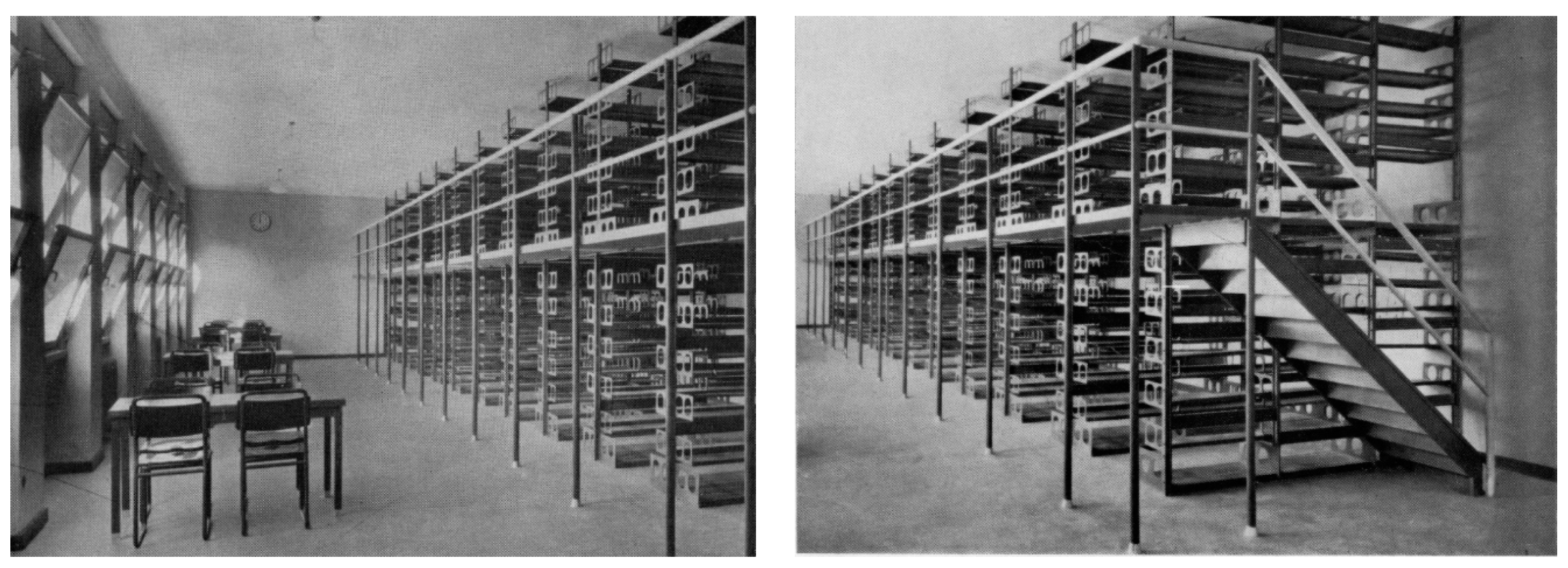

Figure 21).

This system of functional and linear objects initially corresponded more to the taste of elites than to a demand for cheap furniture. It is only since the mid-thirties that metal furniture has been proposed in the catalogue by Italian companies (Columbus, Beltrami di Capriolo, Parma di Saronno, Pino di Parabiago) (

Figure 22) and adopted in buildings and public spaces such as offices, schools, universities, hospitals, shops, and restaurants (

Bassi 1988). A significant collaboration relationship was established between Giuseppe Pagano and the Columbus company, with whom the architect worked in 1934 for the furnishings of the offices of the newspaper “Il Popolo d’Italia” in Milan. Pagano designed, for the Columbus catalog, the hanger, the waste basket, and the umbrella stand (

Bassi 1988).

In 1934, the Gommapiuma patent deposited by the Pirelli company developed a greater simplification of the structural part combined with the padding comfort (

Pansera 1998).

The first Italian experimentations of steel, iron, and aluminum furniture began in 1930. The protagonists of this pioneering phase were Luigi Chessa and Umberto Cuzzi with the Bar Fiorina of Turin (1931–1932). Bar Fiorina’s furnishings were considered in the pages of

La Casa Bella (1932) as fully participating in the new European tendencies. Materials such as chromaluminum, bakelite, and crystal were utilized with an experimental approach so as to explore the potentialities of innovative technologies and promote the renewal of the city, even if at a small scale (

Selvafolta 1980, p. 34) (

Figure 23).

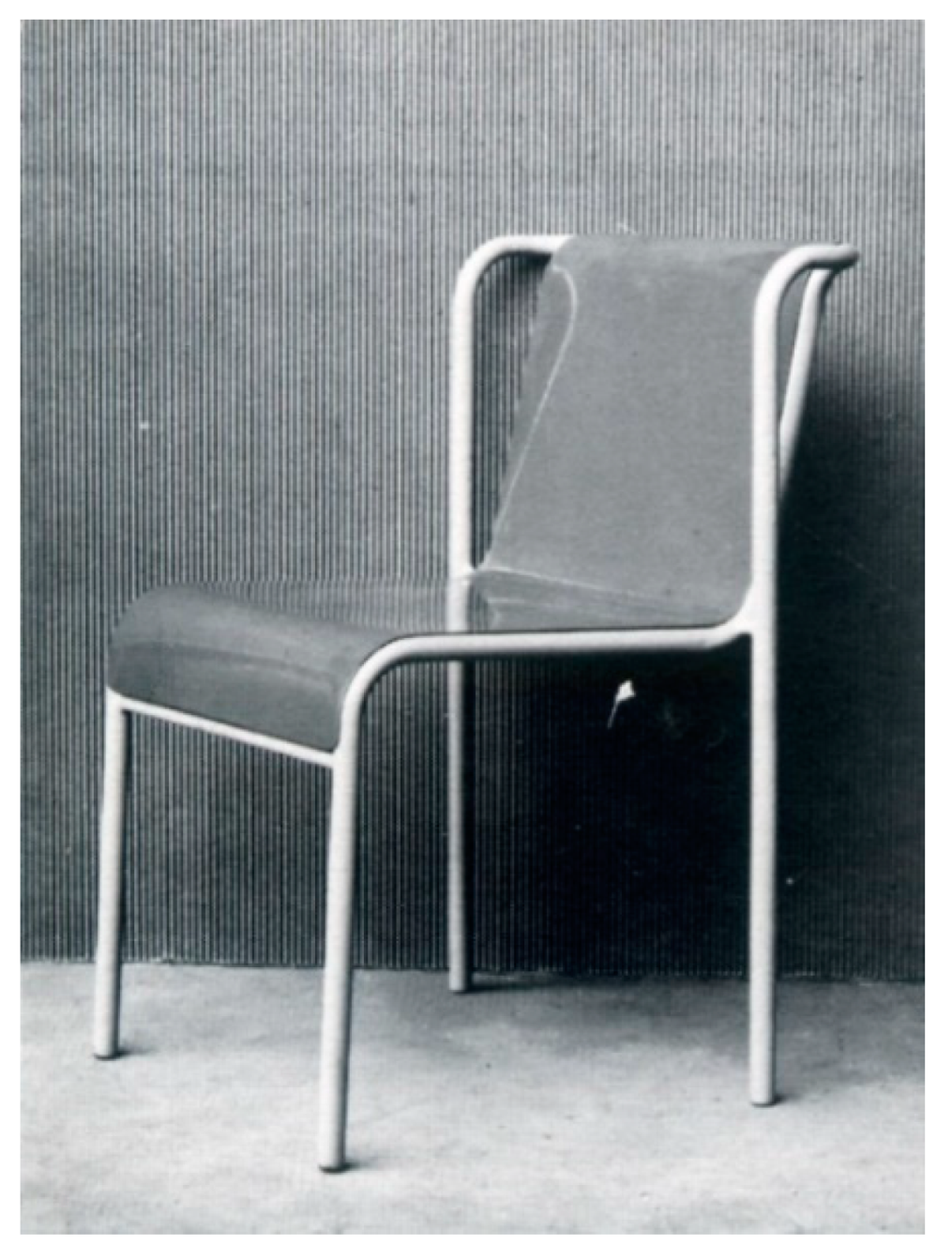

The research conducted by Gabriele Mucchi, maker of a radical renewal in this field, was very original. Between 1934 and 1935, Mucchi collaborated with the Pino company on a series of models. He designed them in a factory in direct contact with productive and economic issues following the prototyping phase (

Figure 24).

Even if inspired by models coming from the north of the Alps, Mucchi’s furniture was original in the rigorous use of the metallic tubular and in the sharp separation between load-bearing elements and parts that are borne. Among the types of stackable chairs, S5 (1936) stands out.

It is composed of two frames of chromed steel and a seat made out of sheet metal, raffia, cord, wood (

Selvafolta 1980, p. 50). Milan’s Triennials (1933, 1936) were the most important showcase for the design of metal furniture. At the 5th Triennial (1933), “Villa-Studio per un artista” by Luigi Figini and Gino Pollini was the manifesto of a vision of modern architecture founded on the Mediterranean tradition, a vision that wanted to distinguish itself from the standpoints of Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier in the name of rationalist solutions consistent with a different historical and natural background.

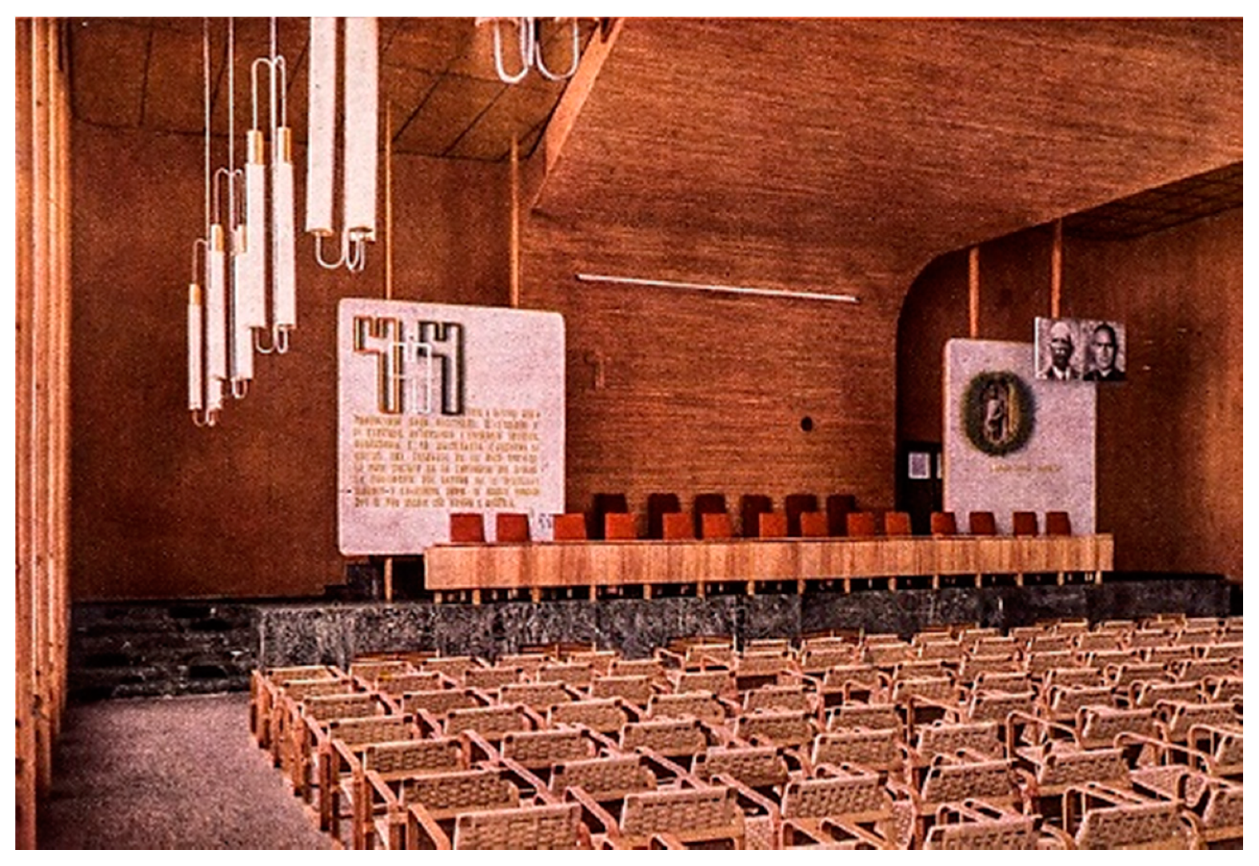

In “Villa-Studio”, geometrical spaces are treated with delicate chromatic nuances, and the furniture consisted of few elements with steel frames and planes of colored glass paste for the tables. This synthetic overview cannot neglect Terragni as a designer.

The monographic issue of the journal

Quadrante (1936) devoted to the “Casa del Fascio” praised Giuseppe Terragni for having taken integral care of the building, from its foundations to the making of its handles. The “Casa del Fascio” was defined—for the architecture and the interior—as the paradigm of a global approach aimed at achieving models of functionality and aesthetics and also of work methods and behavior (

Selvafolta 1980, p. 52).

The furniture had to be consistent with the transparent—even ideological—image of the architecture containing them. Terragni designed light and non-bulky objects, entrusting their implementation to the firm Columbus; in this way, he created armchairs and elastic chairs that were very innovative relative to the guidelines of that time, which imposed rigidity and poise to the sitting posture.

The chair “Lariana” was composed of a seat with the back in bent plywood and a unique metallic frame, while the seat “Benita” was equipped with armrests and coated with a light padding. “Benita” was adopted for the Directory Room of “Casa del fascio” (1932–1936) (

Figure 25) and for the offices of the day care “Sant’Elia” (1936–1937) (

Figure 26), both in Como. For “Sant’Elia”, Terragni engaged himself in the construction of furniture for children with a marked orientation towards a more classically familiar appearance.

Even the new lighting equipment, mostly produced in series, were comparable with foreign production. The ceiling lamps, the table lamps, the appliqués, and the floor lamps were characterized by bases in aluminum or bronze alloys and by engraved or satinized opal glass diffusers, and they were widely used in factories and public and private buildings.

These innovative typologies introduced a different concept in interior lighting, contributing to the definition of the aesthetic of modernity, which, in design, finds a free space for experimentation (

Padoan et al. 2018). Pietro Chiesa was among the most important designers of modern lamps. His activity dates back to 1921, when in Milan, he opened a workshop specialized in processing crystals and glasses with a production of very high quality objects.

In 1933, Chiesa joined the firm Fontana Arte as art director. The results of this fruitful collaboration were simple and elegant lamps but also more complex objects connected to his relationship with the decorative and applied arts (

Selvafolta 1980, pp. 57–58;

Ponti 1949).

This relationship between craftsmanship and industry is a peculiar trait of Italian design. It is worth noticing that, in parallel with the metal furniture and especially in Lombardy, artisans and small firms were continuing their production of furnishings and wooden objects.

From the beginning of the 1930s, a close collaboration between designers and manufacturers began when substitutes for wood were launched into the market.

The research aimed at functionality and the recovery of anonymous design of foldable tables made of strips and straw-bottomed chairs so as to modernize traditional objects by redesigning their shapes (

Tonelli-Michail 1987, p. 89). Although it amounted to a minor production, it is not less interesting because it concerns the complex issue of the relationship between craftsmanship and industry typical of the Italian design culture.