A Life-Line for the Pedagogic Goose: Harnessing the Graduate Perspective in Arts Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Changing Higher Education Landscape

2.2. Art and Design Pedagogy: Opportunities and Challenges

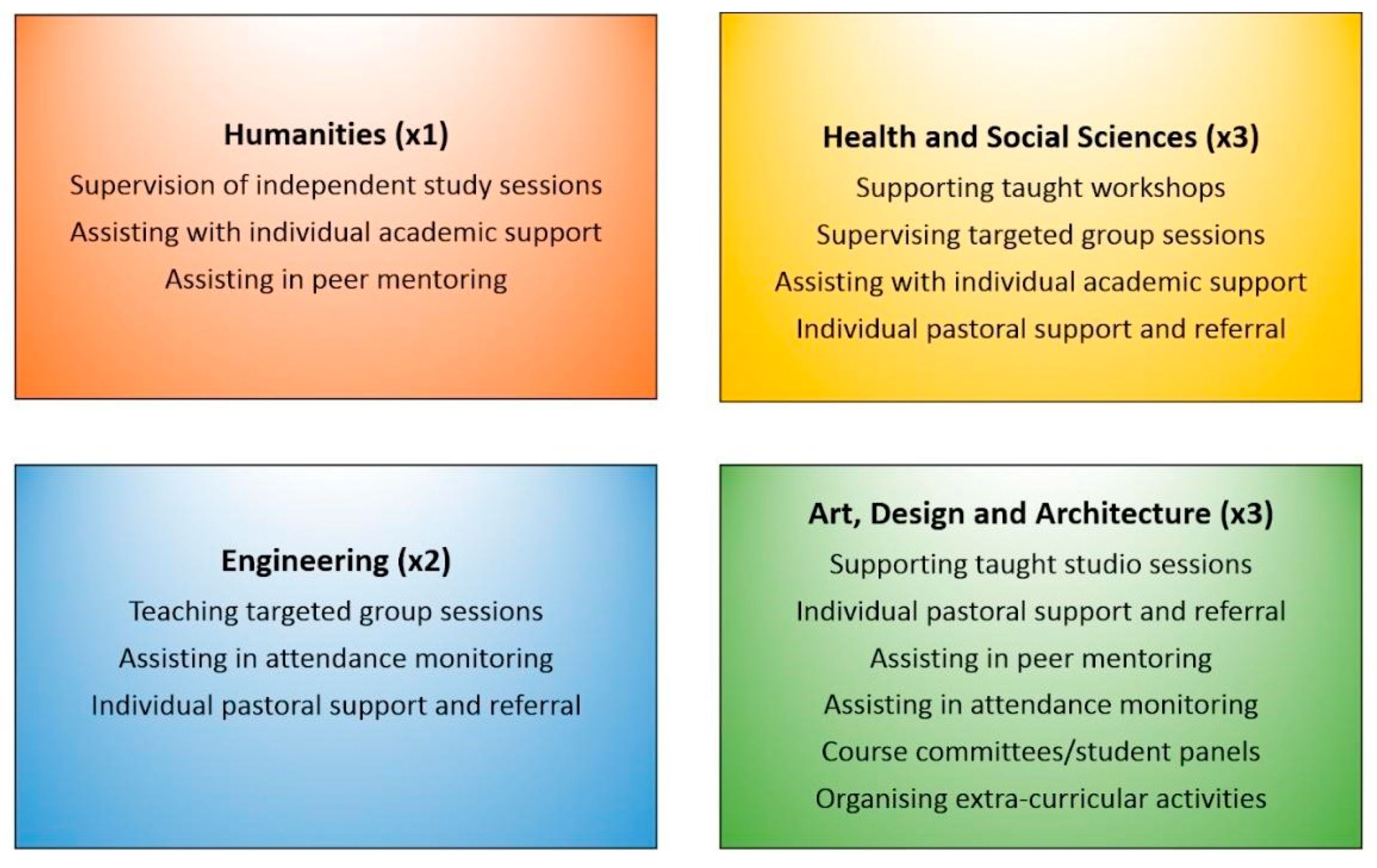

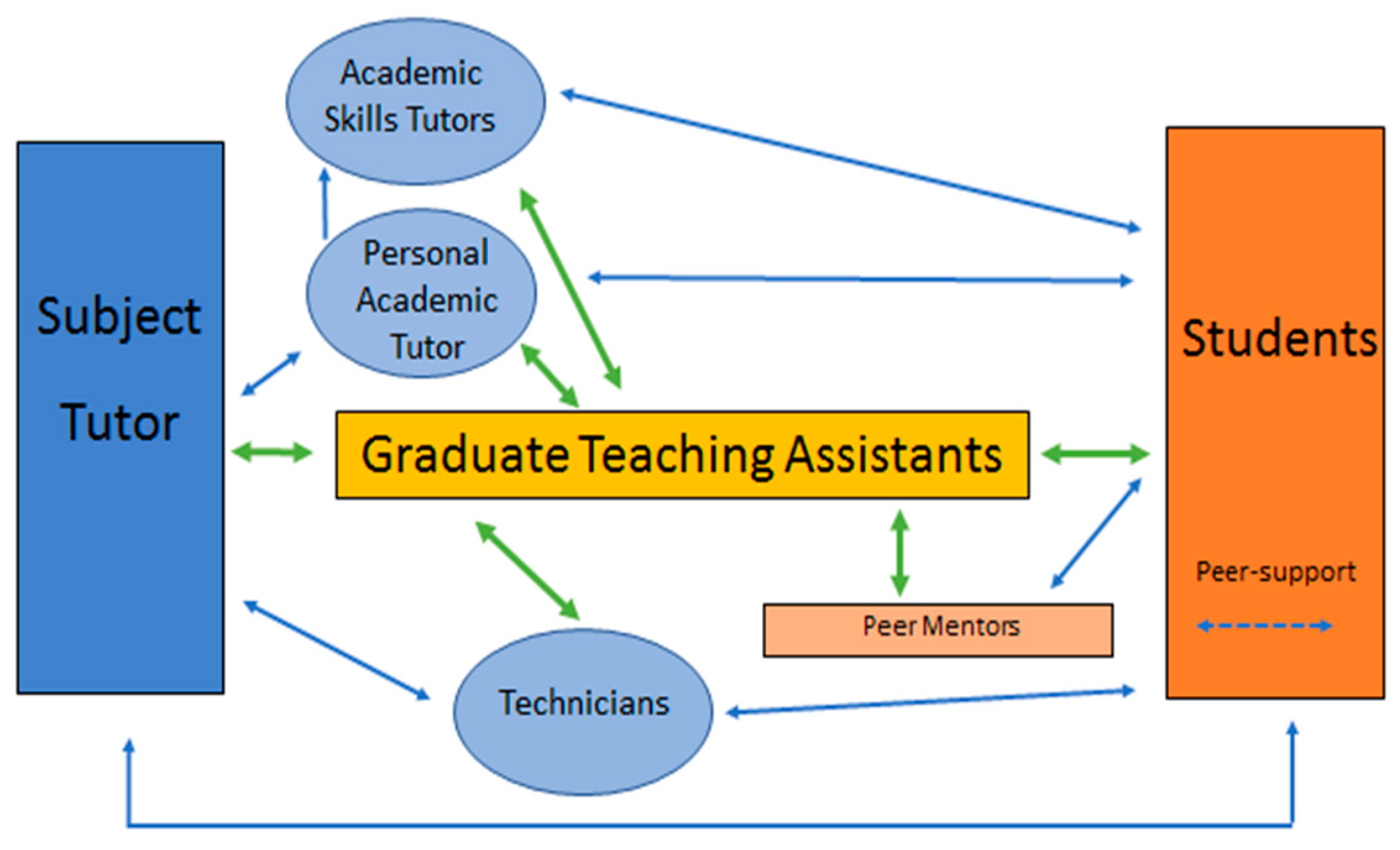

3. Background to the Case

4. Analysing Initial Impact

I can say with certainty the retention data has improved to date … The scheme therefore has been a success, and clearly sets a precedent that indicates when such things are invested in, improvement occurs.(Lecturer 9)

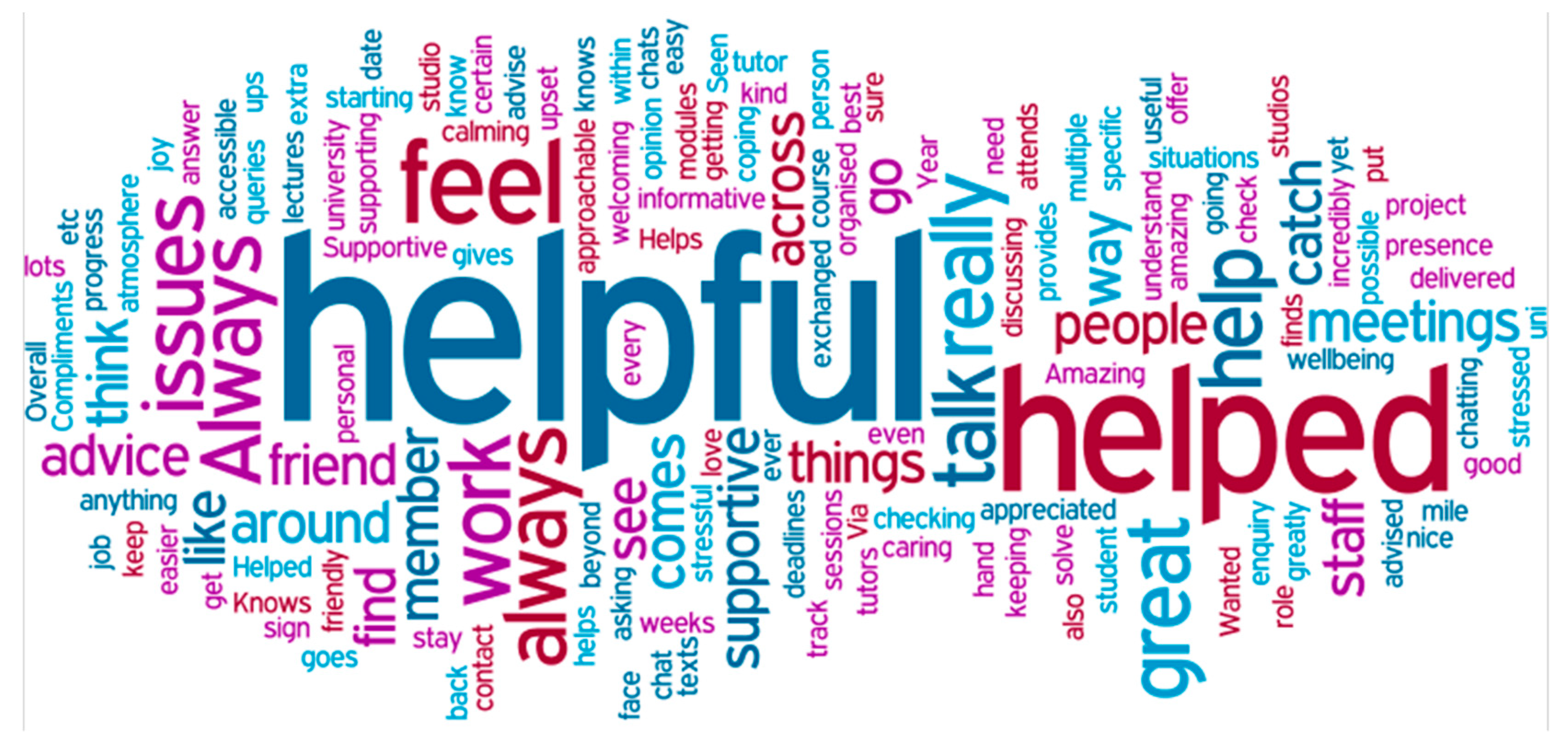

4.1. Navigating University Life

I have been having meetings with her and feel like she has helped and advised me in the best way possible with any issues I have had and she’s helped me stay on track with my uni work.(Student 13)

[She] helped me when starting the course as I was getting stressed and upset about multiple things and has had chats with me, helped me sign up for Wellbeing [services].(Student 3)

… reassuring knowing there is someone I can reach out to who understands our needs as students fully and is able to communicate that to our course leaders in a way we are unable.(Student 15)

The GTA has had a beneficial impact upon student interaction with the department … The key issue is that she is a recent graduate. Not much older than the students she has to work with and has recent firsthand experience of being a student … ensuring that the student’s voice is heard at formal meetings and feeding back discussions and issues with the wider group.(Lecturer F)

4.2. Supporting Studio Work

She has shown great interest in our work as a group and individuals, this included making helpful suggestions and asking questions of us.(Student 18)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akalin, Aysu, and Ihsan Sezal. 2009. The Importance of Conceptual and Concrete Modelling in Architectural Design Education. International Journal of Art & Design Education 28: 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austerlitz, Noam. 2007. The Internal Point of View: Studying Design Students’ Emotional Experience in the Studio via Phenomenography and Ethnography. Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education 5: 165–77. [Google Scholar]

- Austerlitz, Noam, Margo Blythman, Annie Grove-White, Barbara Anne Jones, Carol Ann Jones, Sally J. Morgan, Susan Orr, Alison Shreeve, and Suzi Vaughn. 2008. Mind the gap: Expectations, ambiguity and pedagogy within art and design higher education. In The Student Experience in Art and Design: Drivers for Change. Edited by Linda Drew. Cambridge: GLAD/Jill Rogers Associates, pp. 125–48. [Google Scholar]

- Belfield, Chris, Jack Britton, Lorraine Dearden, and Laura van der Erve. 2017. Higher Education Funding in England: Past, Present and Options for the Future. IFS Briefing Note BN211. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies, Available online: https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/bns/BN211.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2018).

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, John. 2010. Securing a Sustainable Future for Higher Education: An Independent Review of Higher Education Funding and Students Finance; Browne Report. London: HMSO. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-browne-report-higher-education-funding-and-student-finance (accessed on 17 September 2018).

- Bunce, Louise, Amy Baird, and Siân E. Jones. 2017. The Student-as-Consumer Approach in Higher Education and its Effects on Academic Performance. Studies in Higher Education 42: 1958–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, Penny Jane, and Jackie McManus. 2011. Art for a Few: Exclusions and Misrecognitions in Higher Education Admissions Practices. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 32: 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, Elizabeth, and Jodi Gregory. 2016. Internationalizing the Art School: What Part Does the Studio Have to Play? Art, Design & Communication in Higher Education 15: 117–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consumer Rights Act. 2015. c.15. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2015/15/contents/enacted (accessed on 17 September 2018).

- Dearing, Ronald. 1997. Higher Education in the Learning Society; Report of the National Committee of Enquiry into Higher Education. London: HMSO. Available online: http://www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/dearing1997/dearing1997.html (accessed on 17 September 2018).

- Department for Education. 2018. Prime Minister Launches Major Review of Post-18 Education. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/prime-minister-launches-major-review-of-post-18-education (accessed on 13 September 2018).

- Dineen, Ruth, and Elspeth Collins. 2005. Killing the Goose: Conflicts between Pedagogy and Politics in the Delivery of a Creative Education. International Journal of Art & Design Education 24: 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, James. 2001. Why Art Cannot Be Taught: A Handbook for art Students. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Finnigan, Terry, and Aisha Richards. 2016. Retention and Attainment in the Disciplines: Art and Design. York: Higher Education Academy, Available online: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/ug_retention_and_attainment_in_art_and_design2.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2018).

- Frienberg, Jonathan. 2014. Wordle. Available online: http://www.wordle.net/create (accessed on 14 September 2018).

- Hammersley-Fletcher, Linda, and Michelle Lowe. 2011. From General Dogsbody to Whole-Class Delivery—The Role of the Primary School Teaching Assistant within a Moral Maze. Management in Education 25: 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HESA. 2018. Graduate Outcomes. Available online: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/innovation/outcomes (accessed on 13 September 2018).

- Higher Education and Research Act. 2017. c.29. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2017/29/contents/enacted (accessed on 17 September 2018).

- Kahu, Ella R., and Karen Nelson. 2018. Student Engagement in the Educational Interface: Understanding the Mechanisms of Student Success. Higher Education Research & Development 37: 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, Andrew. 2018. What Does ‘Value for Money’ Mean for English Higher Education? Times Higher Education. February 22. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/features/what-does-value-money-mean-english-higher-education (accessed on 17 September 2018).

- Office for Students. 2018. Office for Students. Available online: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/ (accessed on 13 September 2018).

- Orr, Susan, and Alison Shreeve. 2018. Art and Design Pedagogy in Higher Education: Knowledge, Values and Ambiguity in the Creative Curriculum. London: Routledge. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, Susan, Mantz Yorke, and Bernadette Blair. 2014. ‘The Answer is Brought about from within You’: A Student-Centred Perspective on Pedagogy in Art and Design. International Journal of Art & Design Education 33: 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaper, Rille. 2018. ‘Peacekeepers’ and ‘Machine Factories’: Tracing Graduate Teaching Assistant Subjectivity in a Neoliberalised University. British Journal of Sociology of Education 39: 421–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, Aisha, and Terry Finnigan. 2015. Embedding Equality and Diversity in the Curriculum: An Art and Design Practitioner’s Guide. York: Higher Education Academy, Available online: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/node/11103 (accessed on 17 September 2018).

- Seale, Clive. 2018. Researching Society and Culture, 4th ed. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Sims, Ellen, and Alison Shreeve. 2012. Signature pedagogies in art and design. In Exploring More Signature Pedagogies: Approaches to Teaching Disciplinary Habits of Mind. Edited by Nancy L. Chick, Aeron Haynie, Regan A. R. Gurung and Anthony A. Ciccone. Stirling: Stylus, pp. 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Korydon, and Carl Smith. 2012. Non-Career Teachers in the Design Studio: Economics, Pedagogy and Teacher Development. International Journal of Art & Design Education 31: 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovic, Silvia. 2008. Lost in Transition? The International Students’ Experience Project. London: CLIP CETL. [Google Scholar]

- Swann, Cal. 1986. Nellie is Dead. Designer 1: 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, Liz. 2012. Building Student Engagement and Belonging in Higher Education at a Time for Change: Final Report from the What Works? Student Retention & Success Programme. London: Paul Hamlyn Foundation, Available online: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/what_works_summary_report_0.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2018).

- Thomas, Liz, Michael Hill, Joan O’Mahony, and Mantz Yorke. 2017. Supporting Student Success: Strategies for Institutional Change: Summary Report from the What Works? Student Retention & Success Programme; London: Paul Hamlyn Foundation. Available online: https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/hub/download/what_works_2_-_full_report.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2018).

- Universities UK. 2017. Around a Half of Students now See Themselves as Customers of Their University—New ComRes Survey. Available online: https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/news/Pages/Around-a-half-of-students-now-see-themselves-as-customers-of-their-university.aspx (accessed on 13 September 2018).

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tinker, A.; Greenhough, K.; Caldwell, E. A Life-Line for the Pedagogic Goose: Harnessing the Graduate Perspective in Arts Education. Arts 2018, 7, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040088

Tinker A, Greenhough K, Caldwell E. A Life-Line for the Pedagogic Goose: Harnessing the Graduate Perspective in Arts Education. Arts. 2018; 7(4):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040088

Chicago/Turabian StyleTinker, Amanda, Katherine Greenhough, and Elizabeth Caldwell. 2018. "A Life-Line for the Pedagogic Goose: Harnessing the Graduate Perspective in Arts Education" Arts 7, no. 4: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040088

APA StyleTinker, A., Greenhough, K., & Caldwell, E. (2018). A Life-Line for the Pedagogic Goose: Harnessing the Graduate Perspective in Arts Education. Arts, 7(4), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040088