The Anime Connection. Early Euro-Japanese Co-Productions and the Animesque: Form, Rhythm, Design

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Rise of Euro-Japanese Animated Co-Productions

3. The Leading Role of BRB International

4. Euro-Japanese Co-Productions and the Animesque

4.1. Narrative Continuity between Chapters

4.2. Recurrent Use of Cliffhangers and Eucatastrophe

4.3. Iconic and Reductionist Character Designs and Conventionalized Elements

4.4. Specificity of Color Palette and Abundance of Tertiary Colors

4.5. Volume through Movement

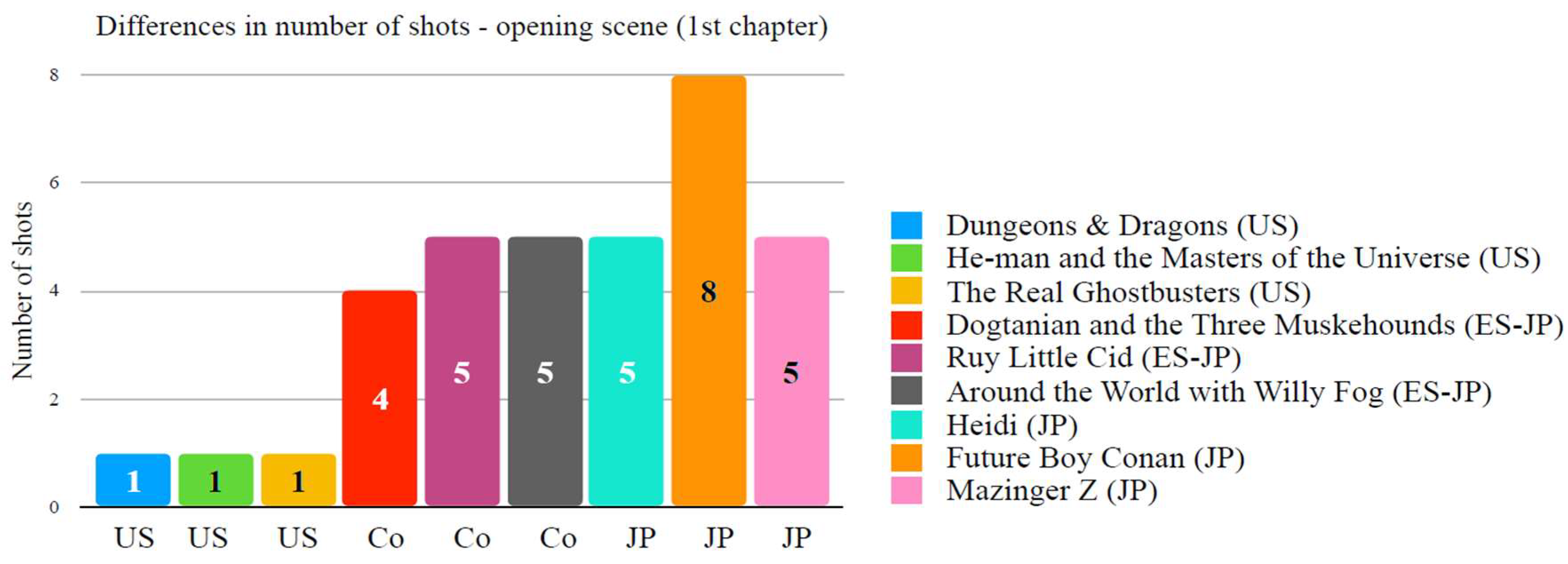

4.6. Particularities in Shots and Montage

5. A Bridge for Anime: Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Azuma, Hiroki. 2009. Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, Jaqueline. 2012. Facing the Nuclear Issue in a “Mangaesque” Way: The Barefoot Gen Anime. Cinergie 2: 148–162. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, Benito. 1978. Análisis de un mito Televisivo «Mazinger Z», un Robot que Influye en sus Hijos. ABC. July 8. Available online: http://hemeroteca.sevilla.abc.es/nav/Navigate.exe/hemeroteca/sevilla/abc.sevilla/1978/07/08/033.html (accessed on 3 June 2018).

- Gan, Sheuo Hui. 2008. The newly developed form of Ganime and its relation to selective animation for adults in Japan. Animation Studies 3: 6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Horno-López, Antonio. 2013. Animación Japonesa. Análisis de Series de anime Actuales. Ph.D. thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Horno-López, Antonio. 2014. El arte de la animación selectiva en las series de anime contemporáneas. In Con A de Animación. Valencia: Universidad Politécnica de Valencia, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Horno-López, Antonio. 2017. El Lenguaje del Anime. Del Papel a la Pantalla. Madrid: Diábolo Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Lamarre, Thomas. 2002. From animation to anime: Drawing movements and moving drawings. Japan Forum 14: 329–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarre, Thomas. 2009. The Anime Machine: A Media Theory of Animation. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCloud, Scott. 1993. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Moliné, Alfons. 2002. El Gran Libro de los Manga. Barcelona: Ediciones Glénat S.L. [Google Scholar]

- Montero, Laura. 2012. Una Conquista Inversa: La Importancia del Anime en el Mercado del Manga Español. Puertas a la Lectura 24: 44–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, Juan Manuel. 1978. La Televisión Como Escuela de Violencia. Madrid: ABC, October 15. [Google Scholar]

- Pellitteri, Marco. 2008. Mazinga Nostalgia. Storia, Valori e Linguaggi Della Goldrake-Generation 1978–1999. Roma: Coniglio Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Pellitteri, Marco. 2010. The Dragon and the Dazzle: Models, Strategies and Identities of Japanese Imagination. Latina: Tunué Editori dell’imaginario. [Google Scholar]

- Querol, Jordi. 2011. MundoManga (ZN Recomienda): Mazinger Z, la Enciclopedia, Tomo 1: Ni una piedra sin analizar [online]. Zona Negativa. March 23. Available online: http://www.zonanegativa.com/mundomanga-zn-recomienda-mazinger-z-la-enciclopedia-tomo-1-ni-una-piedra-sin-analizar/ (accessed on 6 June 2018).

- Romero, Jesús. 2014. ¡Mazinger. Planeador abajo! Palma de Mallorca: Dolmen. [Google Scholar]

- RTVE. 2014. Esto Me Suena. Las Tardes del Ciudadano García—‘Mazinger Z’, un Hito Generacional. March 21. Available online: http://www.rtve.es/alacarta/audios/esto-me-suena-las-tardes-del-ciudadano-garcia/esto-suena-tardes-del-ciudadano-garcia-mazinger-z-hito-generacional/2461131/ (accessed on 23 June 2016).

- Santiago, José Andrés. 2017. Dragon Ball popularity in Spain compared to current delocalized models of consumption. How Dragon Ball developed from a regionally-based complex system into a nationwide social phenomenon. Mutual Images Journal 2: 110–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Arranz, J. Aurelio. 2011. Mazinger Z. La enciclopedia. Palma de Mallorca: Dolmen Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Shamoon, Deborah. 2011. The Films on Paper: Cinematic Narrative in Gekiga. In Mangatopia. Essays on Manga and Anime in the Modern World. Edited by T. Perper and Martha Cornog. Oxford: Libraries Unlimited, pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Shamoon, Deborah. 2015. The Superflat Space of Japanese Anime. In Asian Cinema and the Use of Space: Interdisciplinary. Edited by Lilian Chee and Edna Lim. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Suan, Stevie. 2013. The Anime Paradox: Patterns and Practices through the Lens of Traditional Japanese Theater. Leiden and Boston: Global Oriental. [Google Scholar]

- Suan, Stevie. 2015. Performing differently: Convention, medium, and globality from manga (studies) to anime (studies). In Comicology: Probing Practical Scholarship. Edited by Jaqueline Berndt. Kyoto: Kyoto International Manga Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Suan, Stevie. 2017. Anime’s Performativity: Diversity through Conventionality in a Global Media-Form. Animation. An Interdisciplinary Journal 12: 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Variety. 1984. Spain: Spanish Animator Uses Japan Shops. Variety, April 18, 206. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | Toei Animation 1972. Based on the eponymous manga by Gō Nagai. Entitled in Castilian Spanish as Mazinger El Robot de las Estrellas, Mazinger Z was first screened on TVE on 4 March 1978. |

| 2 | Arupusu no Shōjo Haiji, Nippon Animation 1974. Heidi first aired in Spain on 2 May 1975, on a children’s TV program (Un globo, dos globos, tres globos) on the national public TV channel TVE (Televisión Española). |

| 3 | Instead, UFO Robot Grendizer is considered an equally huge success both in Italy and France. Known in both countries as ‘Goldrake’ or Goldorak, UFO Robot Grendizer is an anime produced by Toei Animation, part of the Mazinger franchise originally created by Gō Nagai. UFO Robot Grendizer was broadcast in Japan from 1975 to 1977. For further information on the topic, I would refer Marco Pellitteri’s in-depth analysis (Pellitteri 2008). |

| 4 | “La Televisión como escuela de Violencia” (TV as a school of violence) by Juan Manuel Ortega and published in the conservative newspaper ABC in 1978. 15 October 1978, p. 118, depicts a picture of Mazinger Z and quotes a survey carried out by CBS, which states: “kids who watch violent series ultimately behave violently.” |

| 5 | Jesús Romero, in a radio interview (21 March 2014), suggested that many complaints were not solely pointed at the violence but rather focused on the lack of a more sophisticated plot, as with Romero in: Las tardes del Ciudadano García—’Mazinger Z’, un hito generacional (RTVE 2014). Romero is also the author of the divulgate book entitled Mazinger. Planeador abajo. Palma de Mallorca: Dolmen. |

| 6 | “In the foreground stand the actual main characters, the monsters fighting each other: on one side Mazinger Z, and on the other side a long series of horrid machines of destruction, identified by different acronyms. This is the main pattern of the movie. In the background, like underrated beings in this world, are the men who pilot the robots: Kōji, a classical cliché of the «gutsy youth» of overdeveloped countries; the wise scientist who loves peace; the hermaphrodite Baron Ashler and, the apex of evil, Doctor Hell. All of them away from the real fight, in a society in which everything works through a button.” (Fernández 1978, p. 25). In the original article Kōji is referred to as ‘Soji’ and Baron Ashler/Ashura (アシュラ) as Baron Asler. For consistency, translation of the original quote follows the original character’s names. |

| 7 | Acronym of Televisión Española, the national state-owned television broadcaster in Spain. |

| 8 | I am grateful to my third blind reviewer for highlighting this connection. |

| 9 | Nippon Animation’s Meisaku collection (lit. meaning “theater masterpieces”) involved several titles depicting the same family-friendly histories, adapting or clearly inspired by some European literary classics meant for children. On 8 January 1977, two years after Heidi’s premiere, Marco, de los Apeninos a los Andes (Haha wo tazunete sanzenri, 1976) was first broadcast in TVE, quickly followed by other animated productions such as El perro de Flandes (Furandâsu no inu, 1975). |

| 10 | |

| 11 | Moliné refers to the source: Eureka 11–12, November–December 1983, p. 5. |

| 12 | Ruy, Pequeño Cid (Ritoru Eru Shido no bōken, 1980), D’Artacán y los tres mosqueperros (Wanwan Sanjushi, 1981) and La vuelta al mundo de Willy Fog (Anime Hachijūnichikan Sekai Isshū, 1983). |

| 13 | David el Gnomo (The World of David the Gnome)—produced in 1985 in partnership with a Taiwanese studio—being the most remarkable example. |

| 14 | Mitsubachi Maya no bōken, Nippon Animation, 1975. |

| 15 | Chiisana Baikingu Bikke, Nippon Animation, 1972. |

| 16 | Seton Dôbutsuki Kuma no ko Jakkī, 1977. |

| 17 | Banner y Flappy (Seton Dôbutsuki Risu no bannâ; German: Puschel, das Eichhorn; and English: Bannertail: The Story of Gray Squirrel) is a German-Japanese animated series. It is based on the tales by Ernest Thompson Seton and co-produced by ZDF (Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen, a German public TV broadcaster) and Nippon Animation. It premiered on April 7th, 1979. It first aired between 1979 and 1980 in Spain. |

| 18 | Ruy, Pequeño Cid (Ritoru Eru Shido no bōken, 1980) was a co-production between BRB International and Nippon Animation, also with the partnership of TVE (Televisión Española, de major public TV channel in Spain). Dogtanian (Wanwan Sanjushi, 1981) was produced by BRB Internacional and Nippon Animation. Around the World with Willy Fog (Anime Hachijūnichikan Sekai Isshū, 1983) was produced by BRB Internacional and animated by Nippon Animation and TV Asahi, in partnership with TVE (Televisión Española). |

| 19 | Maria Aragon (BRB International’s sales VP) in Variety (1984, p. 206). |

| 20 | This fact might eventually bring up some questions in regards to the popularity and continuity of these hybrid co-productions. Even though one could argue that the hybridization did not generate a sustained audience and was superseded by Japanese anime products, I ultimately believe that it was not a problem of critical mass but rather of budget: Japanese anime was cheaper than Euro-Japanese co-productions, thus leading to a market shift. Notwithstanding, the aforementioned BRB co-productions were very successful at the time; and in a similar light, today’s anime-style US productions are also quite successful among an international audience. |

| 21 | I am using animesque in the same way as Suan does, who derives the word from ‘the mangaesque’, coined by Jaqueline Berndt. Mangaesque, as she describes is: “what passes as ‘typically manga’ (or typically anime) among regular media users... in the sense of manga-like or typically manga, which is, of course, no established scholarly term, yet it allows to draw attention to practically relevant popular discourses on the one hand and on the other to critically informed, theoretical reflections on what may, or may not, be expected from manga (and anime)” (Berndt 2012). Therefore, in this paper animesque broadly refers to “anime style”. Thus, animesque productions are those identified as anime by fans—even if these productions are not necessarily anime—or use formal and narrative elements that are traditionally linked with Japanese anime productions. In this paper, the animesque concept is useful to lessen the weight of the nihonjinron discourse and to focus the debate on the formal, narrative and design aspects that ultimately define this medium. |

| 22 | Sherlock Hound (Meitantei Holmes, 1981) is a quite unique example of Euro-Japanese co-production and for that reason I will address it with great caution throughout this paper. Over time Sherlock Hound—a brilliant 1981 co-production between the Italian broadcasting conglomerate RAI and Tokyo Movie Shinsha—has achieved a cult status among fans and critics alike. Its animation exceeds both in quality and production details many other contemporary productions. Hayao Miyazaki was initially involved in the series, directing six chapters. However, production came to a hiatus due to a legal conflict with Conan Doyle’s right-holders. When production restarted in 1984 Miyazaki was already immersed in his Nausicaä project. Kyosuke Mikuriya was responsible for the remaining 20 episodes. Despite this, Miyazaki’s signature style is reflected throughout the whole series, in character’s design, action sequences or humor scenes. |

| 23 | Despite Miyazaki’s attempt to address his movies not as anime but as manga-eiga—an archaic term—and distance himself from the larger idea of the anime medium. |

| 24 | Mirai Shōnen Conan. NHK, 1978. |

| 25 | More than twenty different animated series were analyzed for the purpose of this research, categorized into three different groups: (1) US animated cartoons, popular among the Spanish audience in the 1980s; (2) Euro-Japanese co-productions from the same period; and (3) several coetaneous anime series, many of which aired years later in Spain once the liberalization of the TV frequencies took place. |

| 26 | E.g., He-man and the Masters of the Universe (Filmation, 1983), The Real Ghostbusters (Columbia Pictures and DiC Entertainment, 1986). |

| 27 | E.g., Dungeons and Dragons (Marvel Comics and TSR, 1983). |

| 28 | Selective animation as defined by Gan: “Selective Animation is a new term intended to replace the older expression “limited animation” (…) Such simplified expressions are common in Japan, as several generations have grown up with animated series on television where simplified expressions are standard. In addition, the international commercial success of anime in recent years has also increased their confidence that these expressions are effective, possessing a different aesthetic from the so-called full animation”. (Gan 2008, pp. 6–7). |

| 29 | As pointed by Lamarre “Moreover, as a consequence of the emphasis on static images, camera effects became more pronounced—panning across images, following objects, tracking up or back, framing in or out” (Lamarre 2002, p. 336). |

| 30 | Although the second shot might seem to be an independent shot, it is panning the camera to show us the room and the villains. Therefore, we can only refer to one introductory shot. |

| 31 | In Dungeons and Dragons, He-man and the Masters of the Universe or The Real Ghostbusters there are virtually no (or very few) close-ups, while both anime series and Euro-Japanese co-productions frequently use close-ups. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santiago Iglesias, J.A. The Anime Connection. Early Euro-Japanese Co-Productions and the Animesque: Form, Rhythm, Design. Arts 2018, 7, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040059

Santiago Iglesias JA. The Anime Connection. Early Euro-Japanese Co-Productions and the Animesque: Form, Rhythm, Design. Arts. 2018; 7(4):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040059

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantiago Iglesias, José Andrés. 2018. "The Anime Connection. Early Euro-Japanese Co-Productions and the Animesque: Form, Rhythm, Design" Arts 7, no. 4: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040059

APA StyleSantiago Iglesias, J. A. (2018). The Anime Connection. Early Euro-Japanese Co-Productions and the Animesque: Form, Rhythm, Design. Arts, 7(4), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040059