1. Introduction

Entranced by the Australian landscape and its opal fields, geological works by Chicagoan American architects Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin, two of Frank Lloyd Wright’s former employees, come to mind. The Griffins arrived in Australia in 1914 to execute their expansive vision for its new national capital city, Canberra (

Vernon 2016). The Canberra scheme illustrated an enigmatic quality similar to the early German Expressionists’ architectural spirit in the form of imaginative forces found in Max Berg’s and Wenzel Hablik’s artworks (

Weirick 1988;

Van Zanten 1970,

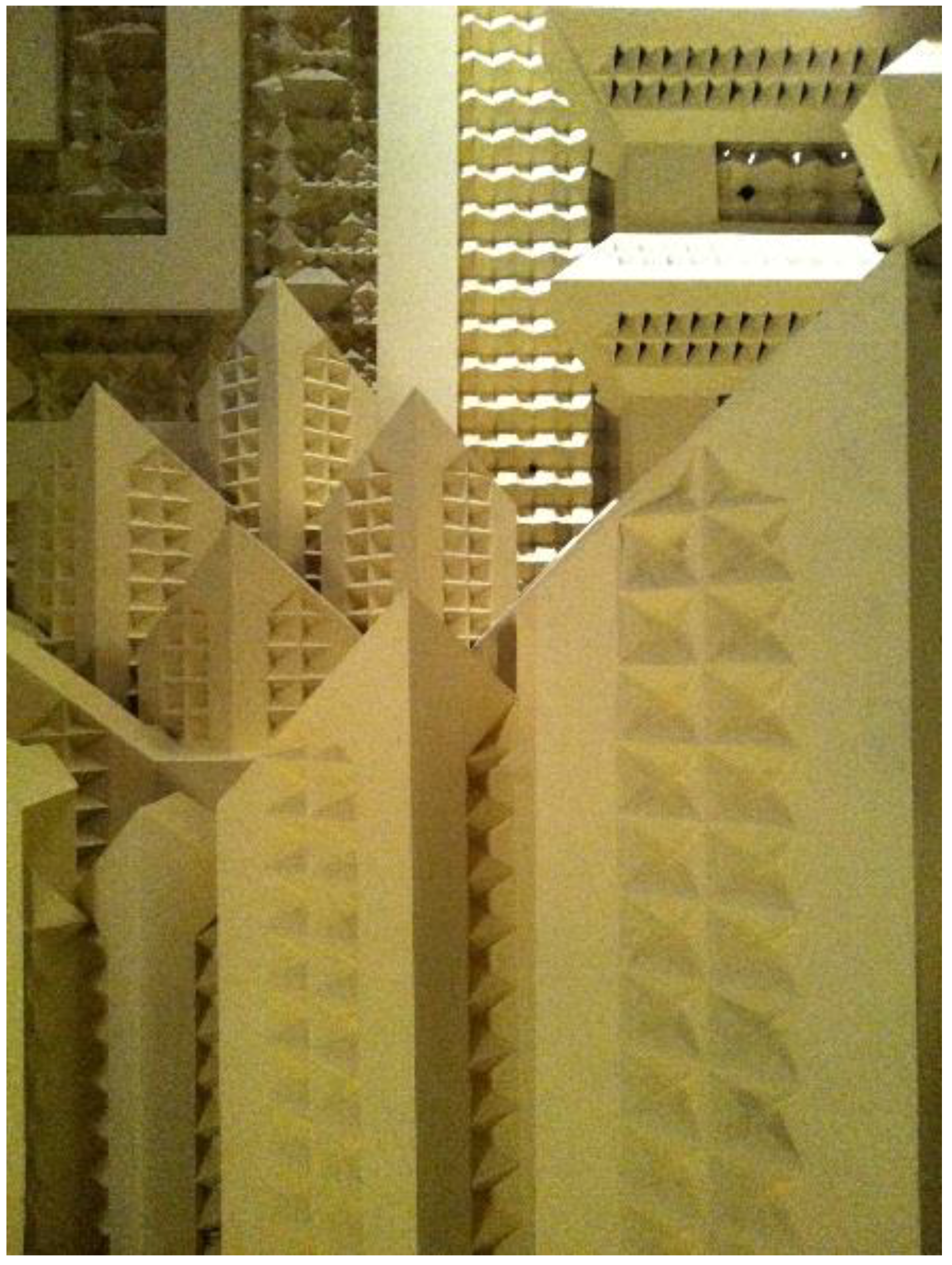

2013). In creating a sensational space for enjoyment for the masses, the Griffins designed the Capitol Theatre (aka Capitol House; 1920–24) accommodating 2000 people—a ten-storey tower combined with shops, offices, and cafes—as a reverie of their unrealized Canberra Capitol Building. When entering the theatre’s auditorium, one is exposed to an array of abstracted prismatic plaster boxes (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) installed along its walls, which, at that time, were economical to produce. The Capitol Theatre most definitely introduced a new technology to Melbourne by introducing changeable illuminated plaster boxes. The Griffins created plastered prismatic forms, resembling a Mayan or Aztec pyramid or crystal cave (

Turnbull 2004). The naming of the building is significant, suggesting that the Griffins, in their own reactionary way, sought to produce a democratic building. Nonetheless, Melbourne’s opalescent plaster labyrinth was, and still is, spellbinding.

Located opposite the Town Hall on Swanston Street, the luxuriously appointed Capitol Theatre is largely considered to be Australia’s first reinforced concrete skyscraper (

Pont 2003, p. 75) (see

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Scholars, looking back, considered the Griffins’ Capitol Theatre’s auditorium ceiling and wall design as the most remarkable project of their some twenty years in Australia, which at the time was the national capital. This theatre project produced a conundrum of material ornamentation, something excessively bright. Acquiring reputations such as the finest cinema in the world (

French 2017, p. 1), this technologically advanced venue is worth dismantling for its European modernist underpinnings, American Jugendstil garden effects, and Mesoamerican echoes. The Capitol auditorium’s highly ornamented metaphorical triangular crystals are set within a serrated lattice of fretted plasterwork. Its walls are shattered into V-shaped prismatic compartments upon which a thousand concealed globes once poured light in a myriad of colours, creating a “prismatic torpedo-shape” (

Boyd 1965, p. 186) interior landscape. Its interior reflects the kaleidoscopic opals as depicted in Katherine Susannah Prichard’s novel,

The Black Opal (1921), where “the colours in the stones—blue, green, gold, amethyst, and red—melted, sprayed and scintillated…” (

Prichard [1921] 1973, p. 138); the novel was published during the Griffins’ auditorium’s construction.

2. The Concept of the “Constructed Landscape”

Reflecting upon the concept of “constructed landscape” as a link between architecture and its geological references, the Griffins incorporated the use of the crystal and opal metaphors within Melbourne’s Capitol Theatre. During their twenty years in Australia, the Griffins’ building was their most outstanding project ever constructed. This technologically advanced venue, commissioned by Antony Lucas in collaboration with the Phillips Brothers (

McGregor 2009), is a crystalline modern interior comprising abstracted prismatic stalactites. Initially, when Lucas and the Phillips Brothers commissioned the project, Herman Phillips showed the architects a handful of colourful crystals obtained in Austria in the hope that the interior would resemble a crystal cave with a glazed ceiling (

Boyd 1965;

Johnson 1977). Another source suggests that the clients brought back “a pair of standard chandeliers of Baccarat glass, said to have once belonged to the Russian Tsar” (

McGregor 2009, p. 369). Although real glass or crystal was considered for the ceiling’s construction, the luxurious material was financially not feasible for the clients. The cost of glass crystals to be manufactured in Belgium far was too astronomical—according to Marion Mahony Griffin, the figure amounted between “£600,000 and £200,000, more than the publicly stated final cost for the entire building!” (

McGregor 2009, p. 369). The vast theatre walls and ceiling’s construction was therefore to be converted into a “magical crystal cave” (

Turnbull and Navaretti 1998, p. 186;

McGregor 2009, p. 369) filled with colour.

Curiously, the Griffins had already established their experiments in the crystalline forms expressed through a cubic grid in their Collins House (1914), on Little Collins Street (now demolished). As far as the Collins House’s façade’s entablature is concerned, there were three rotating devices (or

periaktoi, originally machines used within the ancient Greek theatre to change scenes) (

Kuritz 1988, p. 137). With its revolving prismatic blocks (

Figure 5), the Griffins created a public spectacle that could be seen from the street (

Otto 2009, p. 343). “Prismatic balcony forms, rotated through the cube to reveal a sharp 45° angle, seem to grow directly from the gridded fenestration of the façade. Embedded with small slits of glass these literally were rock crystals” (

Burns 1988, p. 23).

More so than Frank Lloyd Wright, the Griffins sought to “express” the landscape through their prismatic walls and ceiling design, and alternatively interiorized this to form novel architectural forms within their early works. The Griffins’ next project, the Café Australia (1915–16), also in Melbourne, represented crystal-like forms within a geometric frame (

Burns 1988), with opalescent features inserted in its fish ponds. There, according to Christopher Vernon, they “abstracted natural and artificial landscapes and represented them in built form” (

Vernon 2005, p. 18;

Condello 2010, p. 73); that is, a form of interior landscape architecture. Here, the Griffins steered away from Wright and instead derived their ideas and design associations about the landscape from the American skyscraper inventor and landscape gardener William Le Baron Jenney, as well as the luxury gemstones through geological imagery from Paul Scheerbart’s Expressionist writings on glass architecture.

3. Garish Luxury

Luxury in the Western world has been problematic for some writers, since modern architecture was considered “garish” because it was associated with the exotic, especially because of its cultural overtones and gaudy colour schemes. In 1920s Melbourne in particular, the entertaining effect of luxury modified architecture strikingly compared to how it had emerged in Tokyo or Berlin. It created a conundrum of experiential and material “garishness”. Within the context of luxury and according to the

Oxford English Dictionary, “garishness” is defined as something “excessively ornate or bright and dazzling”(

OED 2015). Nocturnal lighting contributed to how luxurious architecture became “garish” through the colourful lighting within structures. Exotic structures coexisted with colourful light, and so, cultural hybrids as a garish brand of luxury were used for enhancing spaces for trading and entertainment purposes. Consequently, Western luxury became twice as exotic in the East, such as Wright’s Imperial Hotel (1923) in Tokyo, Japan, and with the Griffins’ Australia Café design in Melbourne, both of which proved to be problematic for critics because of their garish surfaces, relating to colourful projections, and stylistic breaking away from the Jugendstil aesthetic.

Through the lens of garish luxury and its transnational transformation into block prisms and rock crystals, this article explores Griffins’ crystal cave design and their creation of the constructed landscape ornamented with plaster ridge forms and coloured-light technologies. The Griffins’ design epitomized Melbourne’s assimilation of German Expressionist affinities, specifically of the visionary poet and novelist Paul Scheerbart, who was fascinated with the potential of glass architecture and crystal utopias in the early 1900s. The article also reviews Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition’s landscaped structures, specifically the symbolism of the crystal cave and the great pyramid, considering how the modern Australian auditorium was guided by William Le Baron Jenney’s symbolic and mammoth crystal cave and by embracing Mesoamerican motifs. It argues that Melbourne’s Capitol auditorium’s origins owe much to the ideas deriving from the American Jugendstil garden, Mesoamerican ornamental structures, and the prismatic effects of Australia’s black opal. The interior’s mine-like surfaces radiated natural-seeming but artificially made elements through “opalescent” light within the Capitol’s auditorium to create a modern constructed landscape.

It is important to note that a comparison has been made between the Griffins’ luxurious Capitol Theatre and European cubic architecture, as with Hans Poelzig’s Expressionist

Grosses Schaupielhaus (1918–19) in Berlin (

Burns 1988, p. 25). Poelzig’s structure was a lighting technique extravaganza housed within a dome with a repetitious stalactite-covered ceiling, as well as the set designs he designed in collaboration with his future wife, the German architect and sculptor Marlene Moeschke (

Papapetros 2005;

Clarke 1974). Yet, Poelzig’s garish-looking projects would not have had an influence on the Griffins’ project, since they were not aware of its existence at the time it was built. Instead, they were interested in the Scheerbartian and Mayan manner of producing prismatic forms, which were far more primeval and, simultaneously, sophisticated.

4. Paul Scheerbart’s “Opal Lattice” and the Jugendstil Garden

The German visionary of an electrified future, Paul Scheerbart, prophesied crystal-glass iconography in the earthly landscape. “At the outset of his career in the 1890s, Scheerbart’s imagery is not far removed from that of … Jugendstil: crystalline architecture is introduced as the metaphor of individual transcendence” (

Bletter 1981, p. 32). Excerpts within two of his fascinating texts reveal how ornamental luxury entered the Griffins’ designs in Australia. Devoted to people who were “Freedom−Ready” (

Barnstone 2017, p. 41), Scheerbart’s vibrant essay “The New Life: An Architectonic Apocalypse” (1902) depicts a structural menagerie of jewels, including the opal. He wrote:

Through the colourful panes of glass, a new happiness radiates into the snowy night, making it quite strange.

Emerald globes illuminate the black universe with green cones of light.

Sapphire towers stretch themselves yet higher—like energetic phantoms.

Gigantic opal lattices shimmer like millions of swarming butterflies.

The reference to the opal, both a crystal and gemstone, is indicative of its material abundancy through a network of veins in the southern hemisphere’s ground. This was especially the case from 1915 onward, with the discovery of black opals in Lightning Ridge, Australia (

The Herald 1917;

Werribee Shire Banner 1919). Six years later, Katherine Susannah Prichard, who had earlier visited Lightning Ridge’s opal fields, popularized the high-quality crystal-gem internationally in her novel

The Black Opal. No doubt these geological sources and would have triggered the Griffins to create “gigantic opal lattices” complete with vibrant, energetic coloured lighting within the three-dimensional auditorium. The Griffins thus found their intellectual grounding of the luxury effect of crystals and gemstones in Scheerbart’s Expressionist writings and they culturally transformed them within an Australian context.

Apart from the Griffins intellectual grounding in Scheerbart’s Expressionist writings, Vernon points out that the Griffins were well-aware of the Jugendstil architectural movements, specifically the floral and the geometric aspects in Viennese buildings (

Condello 2010, p. 74). Following a trip from Australia to Europe in 1914, from Paris to Vienna, the Griffins familiarized themselves with the work of the progressive modern architect Otto Wagner (

Condello 2010, p. 74). They visited Berlin and Stuttgart; Marion Mahony Griffin could read German and understand the complexity of the energetic dynamism of depth of Scheerbart’s writings (

Vernon 1995a). Prior to their European trip, it is also important to note that the Griffins visited Joseph Maria Olbrich’s award-winning

Sommersitz eines Kunstfreudes, a summer house constructed at the 1904 St Louis Fair in America, “an exemplary demonstration of Jugendstil interior art, arranged around a courtyard garden” (

Vernon 1995a, p. 240). Nature, for them, was expressed in architectonic forms. Their “rejection of the simulation of a romanticized, ‘raw’ nature in favour of its rational, patterned use and cultivation mirrored Jugendstil ideas on the garden as art” (

Vernon 1995a, p. 240). Eventually, the Jugendstil garden impacted other Chicagoan architects, such as Wright.

5. The Chicago School, World’s Columbian Exposition, and Jenney’s Crystal Cave

The Griffins’ Chicago School influences, most notably the work of Louis Sullivan, have been identified with their use of the stepped pyramid to William Lethaby’s writing. There are also design connections to the World’s Columbian Exposition’s luxuriously appointed pavilions within the Australia Café, and these connections also informed the Capitol Theatre. There are, however, other influential factors to consider when reflecting upon their luxury effects of ornament, especially those emanating from crystalline and prismatic formations.

Within nineteenth-century European archaeological and natural history accounts, crystalline and prismatic formations as a natural characteristic were conceived as intriguing elements of landscapes with which architects could experiment. As Barry Bergdoll has shown, these types of geological references, specifically the cave-like grotto, as depicted, for example, in Joseph Gandy’s painting

Architecture, its Natural Model (1838), offered a model for new architectural forms (

Bergdoll 2007, p. 3). Bergdoll adduces the formal explorations of the Chicago School, namely Louis Sullivan (who twisted ornament from naturalistic forms) and Frank Lloyd Wright (who normalized them into plan and elevation embellishments), which experimented with such an ornamented vocabulary with much integrity. The Chicago School architects experimented with crystals and prismatic forms by transferring geological aesthetic motifs into their plasterwork designs to illustrating the method of creating modern ornamental luxury.

In regard to the artificial objects used to ornament a modern space, Wright obtained the finest luxuries ranging from bespoke clothing to precious ethnic rugs. His famous assessment, “so long as we had the luxuries, the necessities could pretty well take care of themselves” (

Wright [1932] 1977, p. 140), rings true when we observe the luxury for the masses as a need to dazzle the vision of others through ornamental plasterwork in abstracting the natural landscape. The Griffins also designed their own carpets poignantly with abstracted geological imagery in garish colours in green and orange, as in the Capitol Theatre (

Figure 6). Geological imagery casts a glamorous effect upon modernist Australian architecture through the concept of the constructed landscape. Similarly, the Griffins were fixated on geological (and botanical) imagery, especially the crystal, which for Burns, was a “manifestation of ‘evolutionary change’ of minerals growing steadily into perfect geometric types” (

Burns 1988, p. 26). Furthermore, its “shape should be simple enough to be comprehensible and should be complete” (WB Griffin, quoted in

Vernon 1995b, p. 40).

When reconsidering Wright’s work in “The Dangers and Advantages of Luxury”, architectural historian Sigfried Giedion associated Chicago’s ornamental constructions before and after its 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition with a sense of flippancy and superficiality (

Condello 2014, p. 8). At the Chicago Exposition, one of the most eclectic exhibits was Henry Ives Cobb’s Fisheries Building, due to its ornate fish ornamental details within the polygonal pavilions. A large array of exhibits showcased magnificent lighting displays and ornamental monumental arches. This was the case with Jenney’s pyramid and artificial cave, which was illuminated at night. Nocturnal lighting contributed to a sense of luxurious excess. Exotic structures, colorfully lit in gaudy green and orange hues, amounted to cultural hybrid, a garish brand of ornamental luxury used to enhance trading and entertainment venues.

The Chicago Exposition played an active part in producing cutting-edge construction technologies exhibiting grotesque-looking ornamental buildings. The Exposition buildings devoted excessive energy for their glaring electrical exhibits and exotic structures. At the same time, the Chicago venue introduced new bases of entertainment and mass consumption not only in the northern, but also in the southern hemisphere. Its glass houses were, for example, grotesque-looking ornamental buildings which featured a cave as an element of a possible constructed landscape. The Exposition’s pathways illuminating the glass- and white-stuccoed exhibition buildings, made to resemble Alabaster palisades, made Chicago’s streets, caves, and pavilions usable at night. In particular, the glass houses included special lighting effects, and this is specifically the case with the Horticultural Building’s cave designed by William Le Baron Jenney.

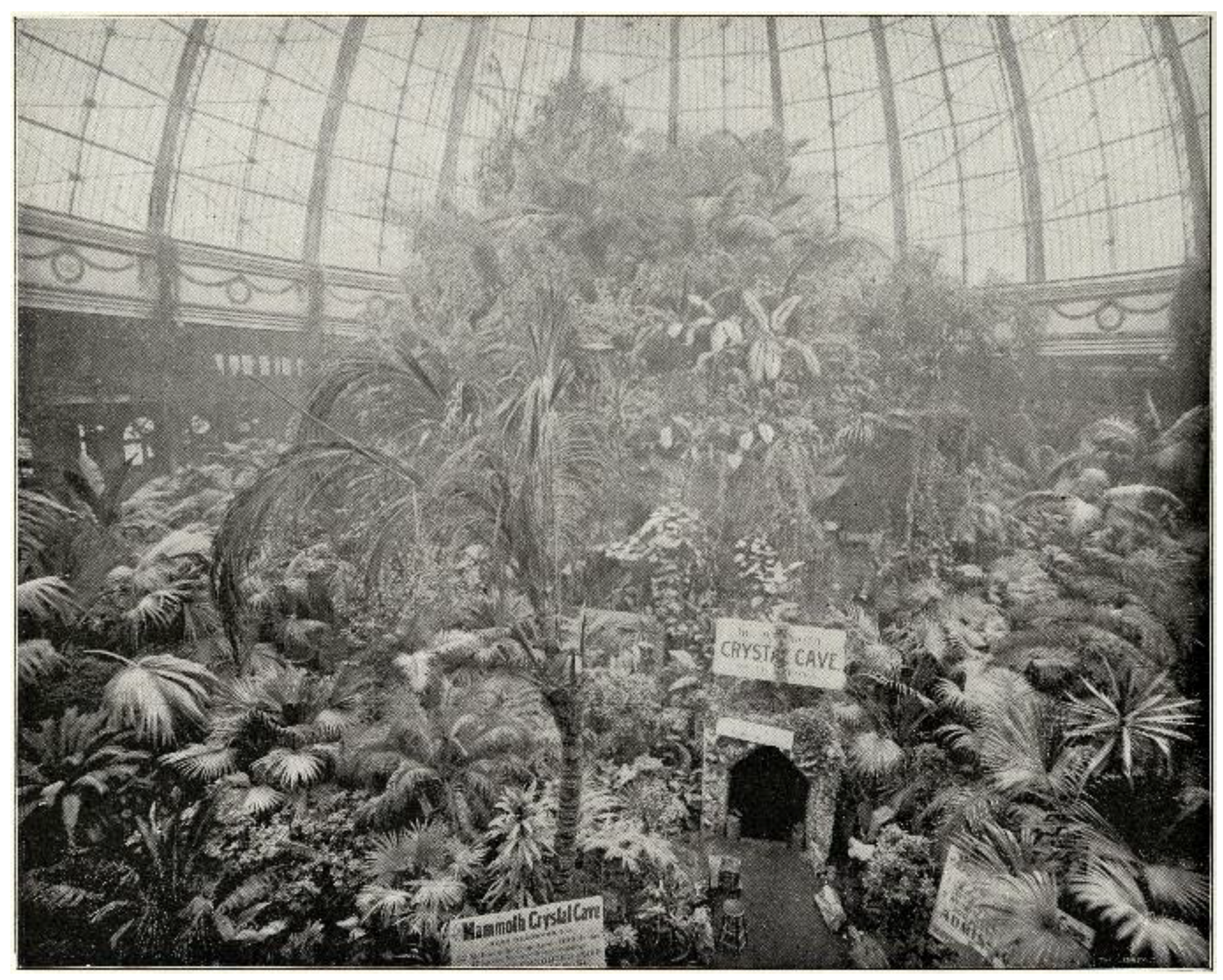

Jenney’s Horticultural pavilion included a grand stepped pyramid in the form of a “Foliage Mountain”, planted with rare palms and blooming flowers. Evidence of this “Mammoth Crystal Cave” design in the form of a stepped pyramid exists in a photograph (Columbian Gallery 1893) (

Figure 7). Enclosing an artificial landscape housed beneath a large crystal dome, its twisting path and tropical mountain enclosed, at its base, a massive pseudo cave. Made of steel construction and coated with plaster, it boasted “stalagmites, stalactites and quartz crystals” and “with the aid of electrical lighting, the final effect was described as both pleasing and dazzling” (

Nielsen and Kumarasurlyar 2014, p. 261). It was unquestionably a brash setting. Considered not so much glass houses as elaborate nocturnal light displays, “crystal caves” conveyed a kind of prismatic sentimentality, relating to Bruno Taut’s work.

Jenney’s symbolic crystal cave was originally designed to conceal the structure’s heating source. Both Frank Lloyd Wright and the Griffins visited the Mayan exhibits at the World’s Columbian Exposition and most likely experienced Jenney’s cave. At the time, the design and construction of this Mesoamerican structure was not in the least popular because of its elaborate or exaggerated ornamentation. The stepped pyramid is categorized herein as a constructed landscape and has therefore to do, in part, with the way that the cave was enhanced as a modern grotto and crystal symbol at Chicago’s Exposition’s pavilions. Capitol Theatre’s auditorium in Melbourne incorporates the symbol of the crystal cave by embedding the Mesoamerican impact of the stepped pyramid, which governed the Griffins’ modus operandi to construct their landscape.

In terms of how the Expressionists impacted Chicagoan architects, curiously, the “German immigrant architects of Chicago acted as channels through which important German ideas could reach the Midwest and influence its culture and architecture” (

Geraniotis 1986, p. 306). This is how the Griffins would have known of these ideas, particularly the metaphor of transformation, such as the anthroposophical architecture of Bruno Taut’s groundbreaking

Trager-Verkaufskontor Pavilion in Berlin (1910). And, intriguingly, the modernist origins of the German Expressionists, specifically Bruno Taut and Scheerbart’s glass house, are credited to Chicago’s Exposition buildings (

Nielsen and Kumarasurlyar 2014). Melbourne’s Capitol auditorium landscape is arguably germane to prismatic and pyramidal forms as found within the Griffins’ interior landscape.

6. Making Melbourne Wealthy through Mining and Gold

Compared to Europe and the Americas, the luxury effect of symbolic crystals modified architecture strikingly in Melbourne. Dubbed the “Chicago of the South” (

Kirsop 1997, p. 1), Melbourne was Australia’s largest city at the beginning of the twentieth century, home to approximately half a million people, and functioned as a temporary national capital between 1901 and 1927. The city became wealthy through mining and gold. Melbourne’s conspicuous displays of wealth rivalled Chicago’s, with a luxurious jetsam of commercial enterprises and entertainment venues along its busiest and most well-lit streets. One of its main thoroughfares, the chaotic and energetic Collins Street, was particularly fashionable, including the Block Arcade (1892), one of Australia’s most iconic shopping centers. The Block was “the place for the Melbourne elite to promenade” (

Lewis 2005, p. 77). Collins Street was also established as the jewelry retailing sector, specializing in selling gold and diamonds (since selling opals did not become widespread until the late 1930s). Apart from the city’s wealthy shopping district, the city’s cinema industry was also emerging, with vaudeville shows and short programs projected in venues along Swanston and Bourke Streets and announced by ornamented lighting posts. In the city center, the electric lighting of streets and buildings was a technologically advanced form of urban luxury reserved for the wealthy. Before long, the lighting of theatrical establishments was introduced as a way to attract and entertain patrons.

During the 1920s, Melbourne experienced change at a fast pace. There was a clamor to bring technological luxury into public buildings, and heavily ornate public buildings and the extensive use of street lights and illuminating structures in the shopping and entertainment district turned the city into a luxurious destination. To this end, investors and developers absorbed the technology of American steel frame construction and Chicagoan skyscrapers, importing—as the example of the Capitol Theatre illustrates—their taste for “landscaped” luxury. Melbourne’s Block district embraced the 1893 Chicago Exposition’s ornamental structures, and Jenney’s pyramids and artificial caves eventually streamed their way into the Griffins’ constructed landscape design, first in Canberra and then in Melbourne. Ornamental elements deriving from these two projects consequently impacted the construction of the landscape within the Capitol Theatre as a series of opal lattices integrated into a prismatic monument.

7. Constructing the Capitol’s Auditorium Landscape with Crystal Forms

When entering the theatre’s auditorium, one is exposed to an array of abstracted prismatic plaster boxes—not glass—installed along its walls. Three-meter-long prismatic plaster boxes became the fundamental element, repeated in rows. These projected from the upper part of the walls, and above them, the ceiling itself rose in a stepped pyramid of wide white solid bands, separated by strips of prismatically textured plaster. Cinema technology was incredibly important to permit wide picture formats for audiences. The Capitol auditorium featured a valuable velvet drop curtain, a cinematograph projection screen, and intricate system of electric wiring, which in contrast to the rest of the auditorium, was standard. The Capitol auditorium’s lighting technology evolved into a centre of stage magic and cinema.

The Capitol’s auditorium landscape became a phantasmagorical setting for projection and lighting through its varying colours and prismatic ridges. Its Mayan-like cubes recall what Jonathan Crary identifies as the

disjunct composition or distortions within Cezanne’s

Pines and Rocks (c. 1900) painting, with its dynamics of perception. According to Crary, the one characteristic which created this type of spectacle is the “diagonal ‘swath’ that runs from the mid-left-hand side of the work to the lower right corner, represent[s] a jumble of rocks and boulders, saturated with violet and flesh colours” (

Crary 1999, p. 330). He continues: “It stands out as a “clearing” in the midst of the play of light and foliage both above and below and constitutes a band of volume and solidity in which the rocks seem to take on a weighty three-dimensional identity” (

Crary 1999, p. 330). For Crary, Cezanne’s painting demonstrates a “persistence of vision” as a form of visual magic. Referring to Crary, Simon During, for instance, states:

“Stage magic” offers a complex interplay between depths and surfaces, two and three dimensions, stasis and transformation, light and shade, transparency and opacity, and reflection and refraction. It does so in [a] highly mechanized visual setting, where there is always occasion for illusion and surprise: it is organized and constructed in such a way as to induce experiences or sensations of amazement, wonder and bewilderment.

Through the experience of its decoration and lighting, celebrated Australian architect and critic Robin Boyd thought the Griffins’ auditorium stage and ceiling demonstrated worthiness from a claustrophobic enclosure into one that is never constricting—a jewel-like plaster labyrinth (

Boyd 1947, p. 17).

Coloured lights also played an important role in transcending the opal allusions within the Capitol auditorium. Rows of “light globes were concealed in the solid torpedoes and bands, controlled backstage by a mechanistic device from a light organ console. The entire space came alive between the movie intermissions” (

Boyd 1965, p. 136). Boyd was enchanted by its crystalline plaster extravaganza and called it “the roof of a giant geometrical limestone cave where the stalactites spread perversely in horizontal layers and the luminous colours were continuously in flux” (quoted in

Birrell 1964, p. ix). The Griffins created their “own sky—accentuating the lightness so cleverly by the few solid bands which bisect it” (

Boyd 1955, p. 110;

Otto 2009, p. 344), in a Scheerbartian manner. Moreover, the Griffins’ drive to create a “geological vision” with the ceiling’s colourful lighting and crystal forms demonstrates a suspended Mayan plaster catacomb, exposing the garish luxury attributes within the auditorium’s landscape.

The interior was ahead of its time; the Griffins internalized the spectacular dazzling light show and accentuated Australia’s own glamorous landscape through cinema technology, in contrast to staid cinemas lacking spectacular walls and ceiling surfaces. Boyd notes that two years after the Capitol auditorium was built, it “was copied in a New York ballroom, and since has appeared in various modifications in countless other places” (

Otto 2009, p. 344). And in 1934,

Paramount’s Capitol News published a tenth anniversary souvenir leaflet of the Melbourne Capitol Theatre, distinguishing the building as “a monument of civic beauty” which provided the best in entertainment (

Griffin and Nicholls 1934). Describing it as the world’s most unusual theatre because of its “marvelous rainbow lighting effects against a scintillating dome”, it was also sensationalized in the

London Press as “the Finest in the British Empire!”. The leaflet noted Griffins’ theory: “concrete in its plastic state can be moulded to any fancy: in its final setting, reinforced with steel, it is stronger than granite…. Aztec-like cubes and squares serve as bases for the structural decorations” (

Paramount Capitol News). More precisely, the interior is interpreted herein as Mayan, rather than Aztec, with its highly ornate lattices, or walls, used as theatrical propaganda to disseminate Scheerbart’s geological−cosmos vision.

Some local architects, however, abhorred the auditorium’s clunky prismatic plaster ceiling, since they believed Mesoamerican devices were passé and sought its demolition. This luxuriously appointed theatre impacted later American designs; more specifically, the Mayan Revival Style of California, such as the work of Robert Stacy Judd, perceived by critics as an authentic neo-Mayan ruin (

Lerner 2001;

Ingle 1984).

It was Marion Mahony Griffin who actually visited the Chicago’s Exposition’s pavilions (

Tinch 2012), and Walter Burley Griffin who was young at that time. Both Wright and Marion visited the Mayan exhibits at the World’s Columbian Exposition and most likely experienced Jenney’s cave as well. Through the list of sources within her autobiographical memoir,

The Magic of America (ca. 1949), Marion provides clues as to how the Capitol Theatre design was conceived. Although she did not reveal the sources of the Exposition’s precedents, Marion did show an intellectual awareness in the modern use of the crystal metaphor, as we have seen with Scheerbart’s Expressionist writings. In imagining a constructed landscape pavilion for the clients, the Griffins were more than likely referencing Scheerbart’s prophesied crystalline architecture and desired to produce their own version of an electrical light opalized luxury show. Such prismatic plasterwork forms and use of colour therefore refer to the buildings, which are comparable to the ideas expressed in the Griffins’ Capitol Theatre project with their abstraction through plasterwork; that is, through their rock crystal transformations. They constructed a landscape as a series of new dynamic residues, a vast

glitter-box with an infinite array of compartments. The constructed landscape projects a sort of butterfly crest—akin to Scheerbart’s apocalyptic-architectural poem, shimmering when ones moves. The gigantic prismatic opal-lattice ceiling (

Figure 8) was illuminated before the film commenced and during intervals.

As pointed out earlier, the Griffins were also interested in the abstraction of the American Jugendstil garden and the Mayan manner of producing prismatic forms, which were far more primeval and, simultaneously, sophisticated. They mirrored and inverted the Jugendstil-styled pathways and roof spaces within the Capitol’s auditorium, a prismatic coffered ceiling designed within an inverted Mesoamerican pyramid (

Figure 9). At the same time, there is an uncanny attenuated alliance to Adolf Loos’ small American Bar ceiling in Vienna (1908), but the Griffins’ version was much more reactionary, more voracious. The Griffins can be considered rebel modernists; they shifted their prismatic luxury design associations away from Europe and America by reverting to Mesoamerican pyramidal components as their underlying ornamental source.

In addition, it is important to note that not only did the Griffins incorporate crystalline structural components in their Australian works, but they also injected Mesoamerican influences in their earlier works in America. The Frank Palma house (1911) in Illinois (aka the “solid rock” project) used strong Mayan-looking planes and flattened ornamentation. In addition, their Melson House (1912) design in Mason City integrated the building with the landscape.

Consequently, the Griffins used Jenney’s symbolic mammoth crystal cave and the Mesoamerican pyramidal form as luxurious devices to conceal new technologies, exported from Chicago and imported into Australia. These similar devices could conceal the technological lighting or music apparatus. Such concealing devices, considered herein as functional luxuries, were central to an understanding of the Griffins’ motivations for introducing American ideas about Mesoamerican landscape and modern illuminations to Melbourne. The concealment of services, such as air-conditioning ducts, was important, since the plasterwork could reveal ornamental luxury in the form of the constructed landscape together with the manufactured breeze. The Capitol’s auditorium “structure itself dissolves under the effect of light, with mass becoming transparent, almost transformed from matter into a crystallized form” (

Burns 1988, p. 25), within an aboveground urban mine. The Griffins prompted the escalating interest in highlighting the exotic materiality of Mesoamerican art, architecture, and constructed landscapes through the pyramidal form within Australia’s state-of-the-art structures. They accomplished this by revisiting German–Austrian Expressionist ideas and merging them with those of Mesoamerican civilizations to inculcate a new luxury city system with cutting-edge technologies for entertainment purposes. Melbourne’s Capitol auditorium’s garish luxury origins owe much to the ideas deriving from the abstraction of the American Jugendstil garden as well as Mesoamerican echoes through their elaborate stepped comb-like structures.

The Griffins as Prismatic Expressionists

As noted earlier, the Griffins would have known about the ideas about Expressionism from German immigrant architects in Chicago, particularly the metaphor of transformation. Scheerbart most definitely impacted Marion Mahony Griffin’s designs. Such prismatic forms are comparable to the ideas expressed in the Griffins’ commercial cinema project, with their abstraction through plasterwork; that is, through their rock crystal transformations. Scheerbart valued glass architecture as an analogue of individual transcendence (

Burns 1988). Many of Scheerbart’s “stories were based in America, particularly Chicago” (

Proudfoot 1994, p. 76), which is a key point and no doubt influenced Marion Mahony Griffin’s interior architectural outlook. Their “rejection of the simulation of a romanticized, ‘raw’ nature in favour of its rational, patterned use and cultivation mirrored Jugendstil ideas on the garden as art” (

Vernon 1995b, p. 240).

The Griffins also mirrored Jugendstil-styled pathways and roof spaces within the auditorium, with a prismatic coffered ceiling designed within an inverted Mesoamerican pyramid. Arguably, in imagining a constructed landscape pavilion for the clients, the Griffins likely were referencing Scheerbart’s prophesied crystalline architecture and desired to produce their own version of an electrical light coloured show, as described in

The Light Club of Batavia: A Ladies Novelette (1912), about a spa in the southern hemisphere for bathing in light at the bottom of an abandoned mineshaft (

McElheny 2010). The Capitol’s auditorium landscape thus became a phantasmagorical setting comprised of crystal-gem iconography (

Figure 10). Additionally, the auditorium’s landscaped plaster ceiling was a stretched-out pyramid (a similar characteristic found in Mesoamerican public spaces where the architectural structures housed ball-games along elongated platforms such as an inverse pyramidal platform, but without a roof structure). The Griffins’ internalized the spectacular lurid light show and accentuated Australia’s own glamourous landscape through cinema technology and through its spectacular walls and ceiling surfaces.

8. Conclusions

When the Griffins were given a handful of Austrian coloured crystals as inspiration for their Capitol Theatre auditorium, they were, in effect, illuminating the link between architectural and geological references and creating “stage magic”. Alluding to both nature and landscape, the Griffins produced an artificial cave, and within its auditorium, constructed an abstracted foliage mountain, which embraced the idea of prismatic Expressionism. This is specifically the case when reflecting upon William Le Baron Jenney’s symbol of the mammoth crystal cave within the Griffins’ Melbourne project and his method of concealment, using the landscape as a functional device to hide equipment. In the same way, the Griffins also provided instrumental views of the many facets of garish luxury within their cinema—where the symbol of the mammoth crystal cave merged with Scheerbart’s novel impact. The Griffins also invented and inverted the Jungendstil–Mayan roof garden, in advance of public opinion. Through its elaborative prismatic ridge plasterwork, the Griffins’ Mesoamerican echoes that were found in the work, with the grotto-like feature, responded to the Jugendstil garden effects. Their garish design in the form of a “constructed landscape” was therefore a reaction against postwar European cubic architecture.

Through the opal references to Katherine Susannah Prichard’s novel and the unforgettable “opal lattices” in Paul Scheerbarts’ Expressionist writing, connection was made to how the Griffins artistically constructed a luxurious Australian landscape within the Capitol Theatre design; they provided a species of garish luxury within their Capitol auditorium. There, a Scheerbartian crystal utopia was realized in conjunction with Jenney’s symbol of the mammoth crystal, thereby producing a spectacular fantasy world of garish colours and lights. The Griffins synthesized a modern crystalised interior by adapting the aesthetic of a cave and used the opal light technologies to advance the Australian entertainment industry. Through its varying colours and prismatic ridges, the Capitol’s auditorium became a phantasmic setting for projecting lighting. The magic of the crystal cave, transcending opal allusions, became an Australian model exemplifying garish luxury. The garish colours of the interior opened up a new world to the audience; by their use and incorporation of the dazzling illumination of the crystal formations by hundreds of incandescent electric lamps, these features exemplified glamour (

Friedman 2010). In addition, the design associations between Paul Scheerbarts’ Expressionist writings on crystal glass iconography and William Le Baron Jenney’s symbolic crystal cave exposed the garish elements, which became a modernist display of dazzle and glitter. The Griffins operated as prismatic Expressionists and their contribution to the Australian entertainment industry led to the emergence of glamour in Australian society from 1924 onward.

Once the opal-coloured light technologies were switched on, through its refracted rays of artificial light upon the ornamental motive underlying the auditorium’s stepped plasterwork plays the dominance of the prismatic ridges, which spiritually transcended the changing dazzling rays upon the ceiling and walls. Since the early 1960s onward, however, the glamorous light lost its lustre, because the building deteriorated and the popularity of the Victorian Derby (Racing Club Group) horserace shows took the lead in Melbourne as a social attraction. The auditorium’s staged magic has no longer functioned as it once did, with revolving lights projecting a fantastical coloured light show. Today, Capitol Theatre is owned by the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) and is currently being restored by Six Degrees Architects into its former opalescent-coloured glory. The architectural envelope is no longer an explicit concern. Materially, garish luxury no longer overtly encroaches upon contemporary architectural design as such, only via the cinematic image. To this day, Melbourne’s “constructed landscape” auditorium continues to provide us with an exhilarating experience, albeit a confronting one with its opal glamour of luxury. It continues to be a fascinating in-depth “constructed landscape” model to visit to understand its derivations of geological qualities that shaped the curious origins of Australian glamour.