Looking into the “Anime Global Popular” and the “Manga Media”: Reflections on the Scholarship of a Transnational and Transmedia Industry

Abstract

:1. The Problematic Definition of “Anime” and “Anime Studies”

1.1. Anime and Academia

1.2. Anime Disciplinisation and Future Directions: Who Will Lead towards Anime Epistemology?

We can see examples of these different directions throughout this special issue, where the problem of discipline, object of study, and scholar identity splits into new uneasy questions. Thus, Comic Studies is replaced by Manga Studies shifting from Media Studies to a more specific and isolated, but perhaps more legitimate approach (Kacsuk 2018, p. 4). In this scenario, interdisciplinary dialogue—when the ideal transdisciplinary collaboration among scholars is not possible—seems to be the best choice.…have operated as a form of thought police maintaining this emphasis on language issues, guarding the field from the encroachments of theory and protecting it from disciplinary specialists who lack the linguistic tools deemed necessary to understand Japan.

2. “Manga Media” and Their Ecosystem

2.1. Its Etymology

2.2. Its Complexity and Diversity

2.3. Its Audiences

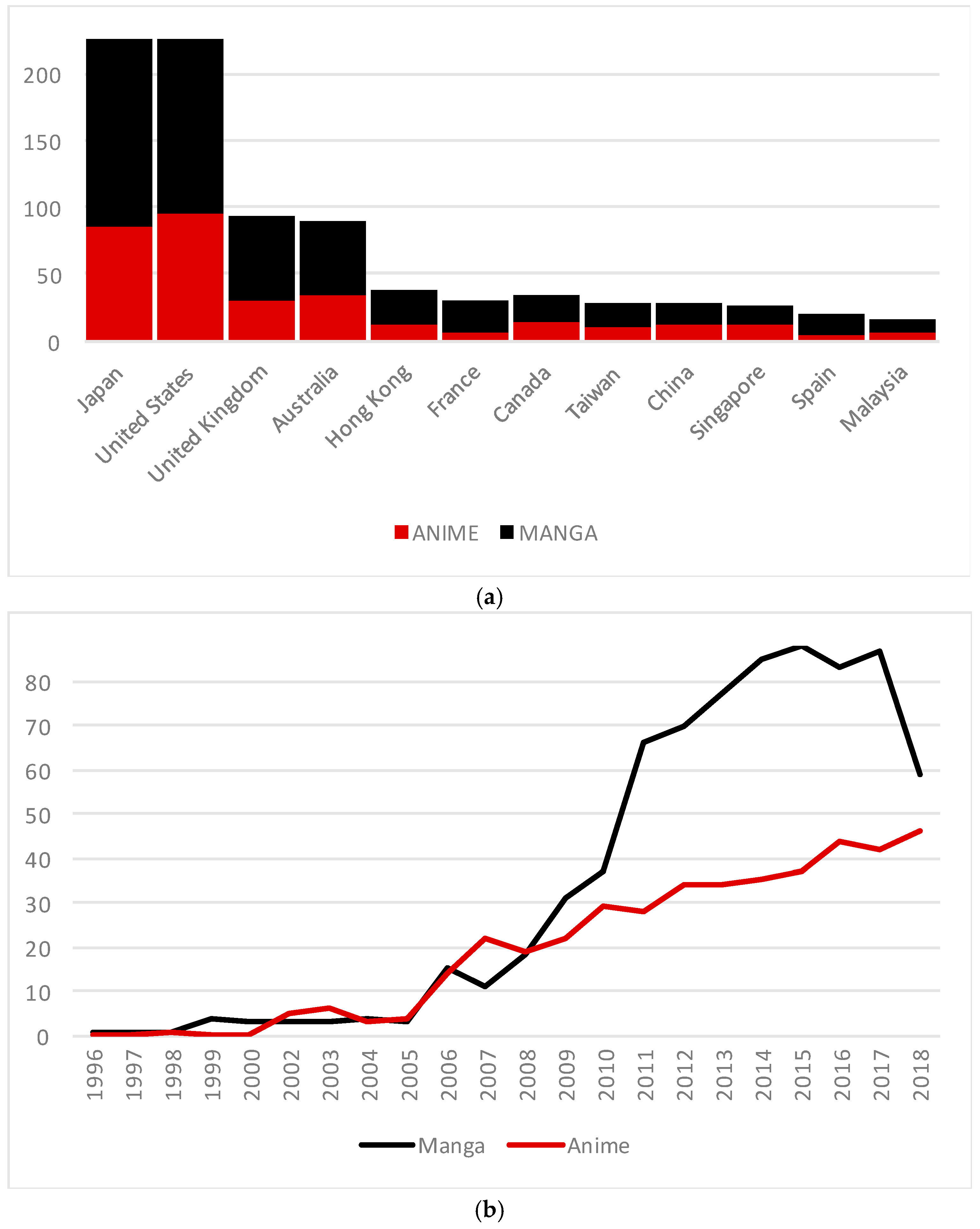

3. Manga Media (Including Anime) as a Manifestation of the Global Popular

4. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allison, Anne. 2006. Millennial Monsters: Japanese Toys and the Global Imagination. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Azuma, Hiroki. 2009. Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, Jaqueline. 2008. Considering Manga Discourse. Location, Ambiguity, Historicity. In Japanese Visual Culture: Explorations in the World of Manga and Anime. Edited by Mark W. MacWilliams. London: Routledge, pp. 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, Jaqueline. 2012. Intercultural Crossovers, Transcultural Flows: Manga/Comics. Kyoto: Kyoto Seika University International Manga Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, Jaqueline. 2018. Anime in Academia: Representative Object, Media Form, and Japanese Studies. Arts 7: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. 2000. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, Chris. 2004. The Asian studies “crisis”: Putting cultural studies into Asian studies and Asia into cultural studies. International Journal of Asian Studies 1: 121–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daliot-Bul, Michal, and Nissim Otmazgin. 2017. The Anime Boom in the United States: Lessons for Global Creative Industries. Harvard: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- During, Simon. 1997. Popular Culture on a Global Scale: A Challenge for Cultural Studies? Critical Inquiry 23: 808–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eco, Umberto. 1984. The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Texts. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, Matthew. 2017. A world of Disney: building a transmedia storyworld for Mickey and his friends. In World Building: Transmedia, Fans, Industries. Edited by Marta Boni. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Press, pp. 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Groensteen, Thierry. 1996. L’univers des mangas: Une introduction à la bande dessinée japonaise. Tournai: Casterman. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Stuart. 1980. Cultural studies: two paradigms. Media, Culture & Society 2: 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Hernández, Alvaro David. 2018. The Anime Industry, Networks of Participation, and Environments for the Management of Content in Japan. Arts 7: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pérez, Manuel. 2017. Manga, anime y videojuegos. Narrativa cross-media japonesa [Manga, Anime and Videogames. CrossMedia Japanese Narratives]. Zaragoza: Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Pérez, Manuel. 2017b. Thinking of Spain in a flat way’: Spanish tangible and intangible heritage through contemporary Japanese anime. Mutual Images 3: 43–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Pérez, Manuel, Kevin Corstorphine, and Darren Stephens. 2017. Cartoons vs. Manga Movies: A Brief History of Anime in the UK. Mutual Images 2: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higson, Andrew. 2000. The limiting imagination of national cinema. In Cinema and Nation. Edited by Mette Hjort and Scott Mackenzie. London: Routledge, pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hills, Matt. 2002. Transcultural Otaku: Japanese representation of fandom and representation of Japan in anime/manga fan cultures. Media in Transition 2: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Kinko. 2005. A history of manga in the context of Japanese culture and society. The Journal of Popular Culture 38: 456–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwabuchi, Kōichi. 2002. Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism. Durham: Duke University Press Books. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kacsuk, Zoltan. 2018. Re-Examining the “What is Manga” Problematic: The Tension and Interrelationship between the “Style” versus “Made in Japan” Positions. Arts 7: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsella, Sharon. 1998. Japanese Subculture in the 1990s: Otaku and the Amateur Manga Movement. Journal of Japanese Studies 24: 289–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarre, Thomas. 2018. The Anime Ecology: A Genealogy of Television, Animation, and Game Media. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, John. A. 2007. The Transformation of Asian Animation: 1995–Present. Asian Cinema 18: 105–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, Antonia. 1996. Samurai from Outer Space. Understanding Japanese Animation. Chicago and La Salle: Carus Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Méndez, Artur. 2016. Introducción. La producción de conocimiento sobre Japón a través de los estudios culturales. In El Japón Contemporáneo: una Aproximación Desde los Estudios Culturales. Edited by Artur Lozano-Méndez. Barcelona: Edicions Bellaterra, pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, Dolores P. 1998. The Worlds of Japanese Popular Culture: Gender, Shifting Boundaries and Global Cultures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, Takashi. 2000. Superflat. Tokyo: Madora Shuppan. [Google Scholar]

- Napier, Susan Jollife. 2001. Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Patten, Fred. 2004. Watching Anime, Reading Manga: 25 Years of Essays and Reviews. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pellitteri, Marco. 1999. Mazinga nostalgia. Storia, valori e linguaggi della Goldrakegeneration. Roma: Coniglio Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Pellitteri, Marco. 2010. The Dragon and the Dazzle: Models, Strategies, and Identities of Japanese Imagination. A European Perspective. Latina: Tunué. [Google Scholar]

- Pellitteri, Marco. 2018. Kawaii Aesthetics from Japan to Europe: Theory of the Japanese “Cute” and Transcultural Adoption of Its Styles in Italian and French Comics Production and Commodified Culture Goods. Arts 7: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penney, Matthew. 2009. Nationalism and anti-Americanism in Japan–manga wars, Aso, Tamogami, and progressive alternatives. The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 7: 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, James, and Peter J. Rabinowitz. 2012. Narrative as Rethoric (Introduction). In Narrative Theory. Core Concepts and Critical Debates. Edited by David Herman, James Phelan and Peter J. Rabinowitz. Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Postman, Neil. 2000. The humanism of media ecology. Proceedings of the Media Ecology Association 1: 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Reader, Ian. 1998. Studies of Japan, area studies, and the challenges of social theory. Monumenta Nipponica 53: 237–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Marie Laure. 2004. Narrative across Media: The Languages of Storytelling. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago Iglesias, José Andrés. 2018. The Anime Connection. Early Euro-Japanese Co-Productions and the Animesque: Form, Rhythm, Design. Arts 7: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Schodt, Frederik L. Schodt. 1983. Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics. New York: Kodansha. [Google Scholar]

- Schodt, Frederik L. Schodt. 1996. Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schodt, Frederik L. Schodt. 2007. The Astro Boy Essays: Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, and the Manga/Anime Revolution. Berkley: Stone Bridge Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scolari, Carlos Alberto, Paolo Bertetti, and Matthew Freeman. 2014. Transmedia Archaeology: Storytelling in the Borderlines of Science Fiction, Comics and Pulp Magazines. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Scolari, Carlos Alberto. 2009. Transmedia storytelling. Implicit consumers, narrative worlds, and branding in contemporary media production. International Journal of Communication 3: 586–606. [Google Scholar]

- Scolari, Carlos Alberto. 2012. Media ecology: Exploring the metaphor to expand the theory. Communication Theory 22: 204–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, Marc. 2004. Otaku consumption, superflat art and the return to Edo. Japan Forum 16: 449–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, Marc. 2012. Anime’s Media Mix: Franchising Toys and Characters in Japan. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suan, Stevie. 2018. Consuming Production: Anime’s Layers of Transnationality and Dispersal of Agency as Seen in Shirobako and Sakuga-Fan Practices. Arts 7: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, John. 2012. Cultural imperialism. In The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Globalization. Edited by George Ritzer. Hoboken: Wiley Online Library, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Torrents, Alba. 2018. Technological Specificity, Transduction, and Identity in Media Mix. Arts 7: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, Shiro. 2018. The Essence of 2.5-Dimensional Musicals? Sakura Wars and Theater Adaptations of Anime. Arts 7: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Please notice that, while I recognize the relevance of the Japanese speaking authors and their priviliged access to sources that are key for the understanding of these media, I’m much more interested in the depiction of an international academic discourse. While manga and anime can be not one but two different discursive objects, the text by Jaqueline Berndt (2008), “Considering Manga Discourse Location, Ambiguity, Historicity” may be a useful starting point for those interested in the description of debates arising within Japanese-language forums. |

| 2 | See, for example, the series of essays by Maria Teresa Orsi titled “Il Fumetto in Giappone 1” (1978), an academic reference that locates manga as an outcome of Japan’s Meiji era. By linking manga to Japan’s adaptation of Western newspapers’ satirical traditions, this may be one of the first non-continuist approaches to its origin in Western academia. On the other hand, sociologist Marco Pellitteri (1999) offers in Mazinga Nostalgia a comprensive study of the international distribution, adaptation and reception of anime through the case of the Italian market. |

| 3 | It may be necessary to differentiate between the notion of aesthetics as an individual perspective and as a shared feature. In this special issue, Alba Torrents (2018) concisely argues how each medium can be assessed according to its aesthetic, by evaluating its ontological materialities. |

| 4 | In this context, I prefer not to differentiate between transnationalisation and globalisation, although in fact they have been defined as very different, even opposite terms. Transnational media flows have been defined as a result of the interaction between different national producers, and, unlike “globalization”, can present more than one centre (Iwabuchi 2002). |

| 5 | While there are valuable exceptions of projcts embracing Cultural Studies, in the form of articles but mostly, as collaborative books (Lozano-Méndez 2016), these are not necessarily critical and not specially focused on identity as a key articulation point. This surely indicates how wrong it is to define the Cultural Studies Project as a homogeneous theoretical body. Instead, multidisciplinar approaches connecting Literary Theory, Political Economy, Film Studies, among many others, are the usual starting point. It also reinforces my idea of being in a “paradigm” where some key concepts such as “cultural hegemony”, “consumption as a response or manifestation of identy”, and other legacies of this tradition are, perhaps wrongly, taken for granted. |

| 6 | In this sense, I have commented in this article, some examples where Media Studies terminology, such as the one derived “media ecology”, is used in purely descriptive terms. These approaches are valid and have some value, but they could have been transformed in more valuable contributions to the field of Anime Studies (and also Media Studies) if they had engaged with a deeper reflection of the terms employed. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hernández-Pérez, M. Looking into the “Anime Global Popular” and the “Manga Media”: Reflections on the Scholarship of a Transnational and Transmedia Industry. Arts 2019, 8, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020057

Hernández-Pérez M. Looking into the “Anime Global Popular” and the “Manga Media”: Reflections on the Scholarship of a Transnational and Transmedia Industry. Arts. 2019; 8(2):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020057

Chicago/Turabian StyleHernández-Pérez, Manuel. 2019. "Looking into the “Anime Global Popular” and the “Manga Media”: Reflections on the Scholarship of a Transnational and Transmedia Industry" Arts 8, no. 2: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020057

APA StyleHernández-Pérez, M. (2019). Looking into the “Anime Global Popular” and the “Manga Media”: Reflections on the Scholarship of a Transnational and Transmedia Industry. Arts, 8(2), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8020057