Aesthetics and Usability in Digital Art Repositories: Using the iMedius Platform to Collect User Feedback Through Attention Tracking

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work and Targeted Innovation

2.1. User Experience in Digital Art Repositories

2.2. Aesthetics and Usability: Theoretical Foundations and Their Interplay

2.3. Methodological Frameworks for Measuring User Experience and Attention

3. Methodology

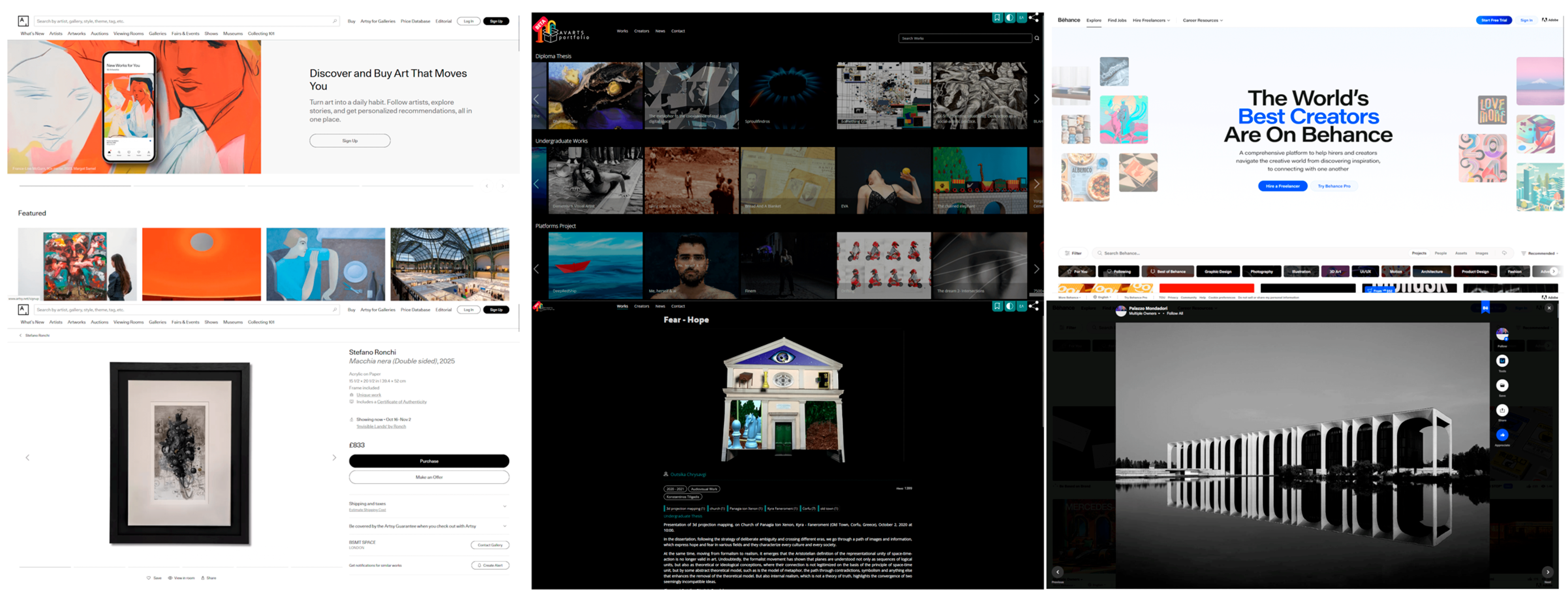

3.1. Research Design

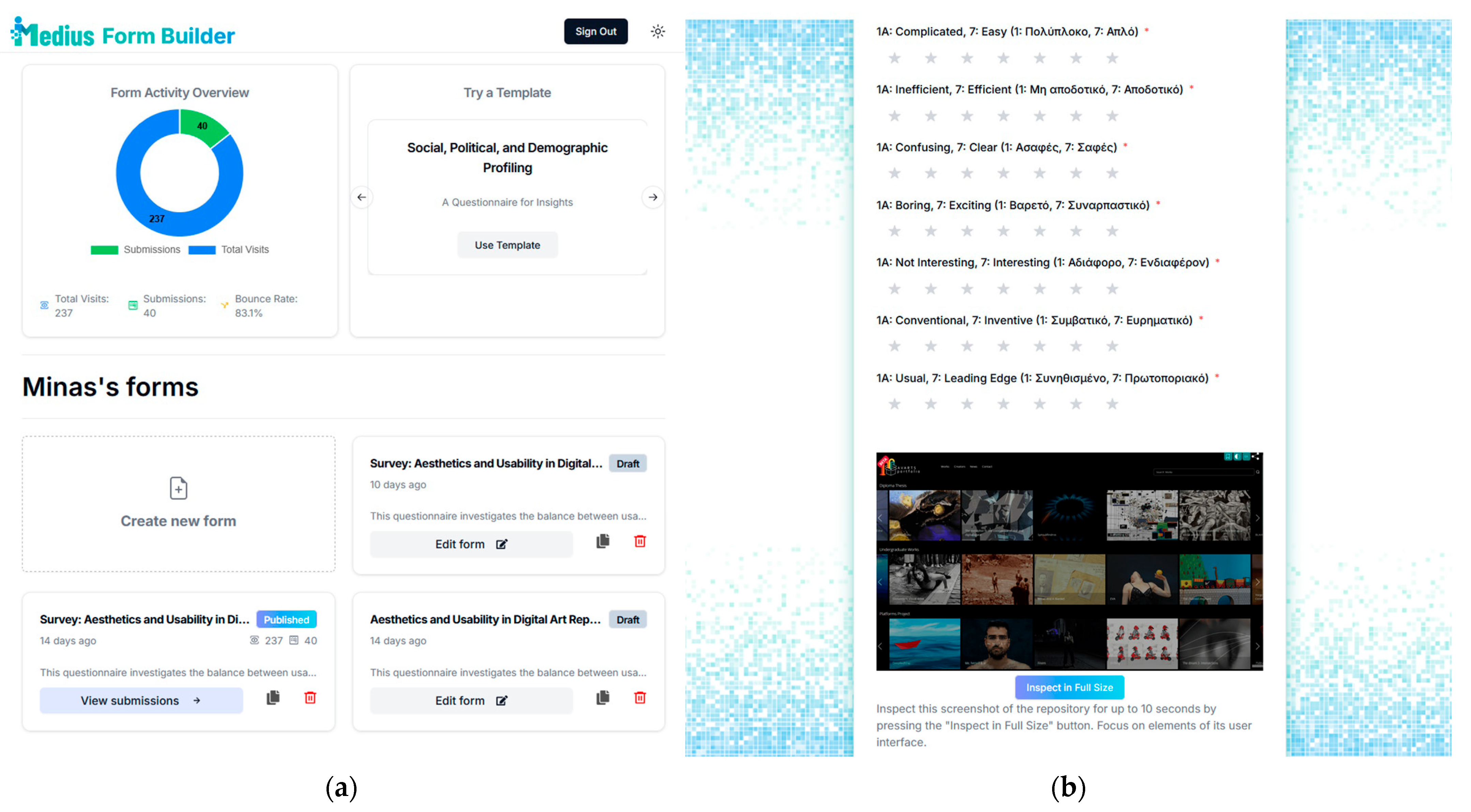

3.2. Implementation with the iMedius Form Builder

3.3. Questionnaire Design

3.4. Data Collection

4. Results

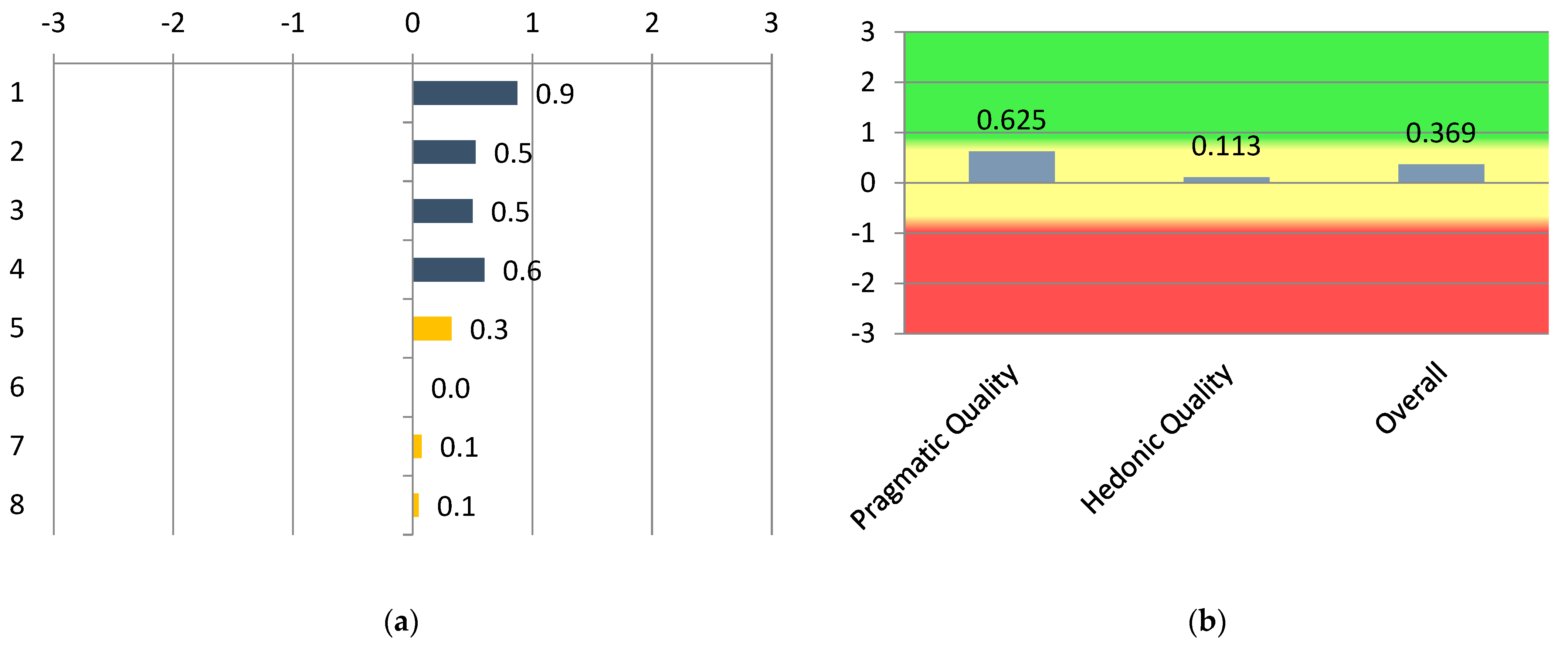

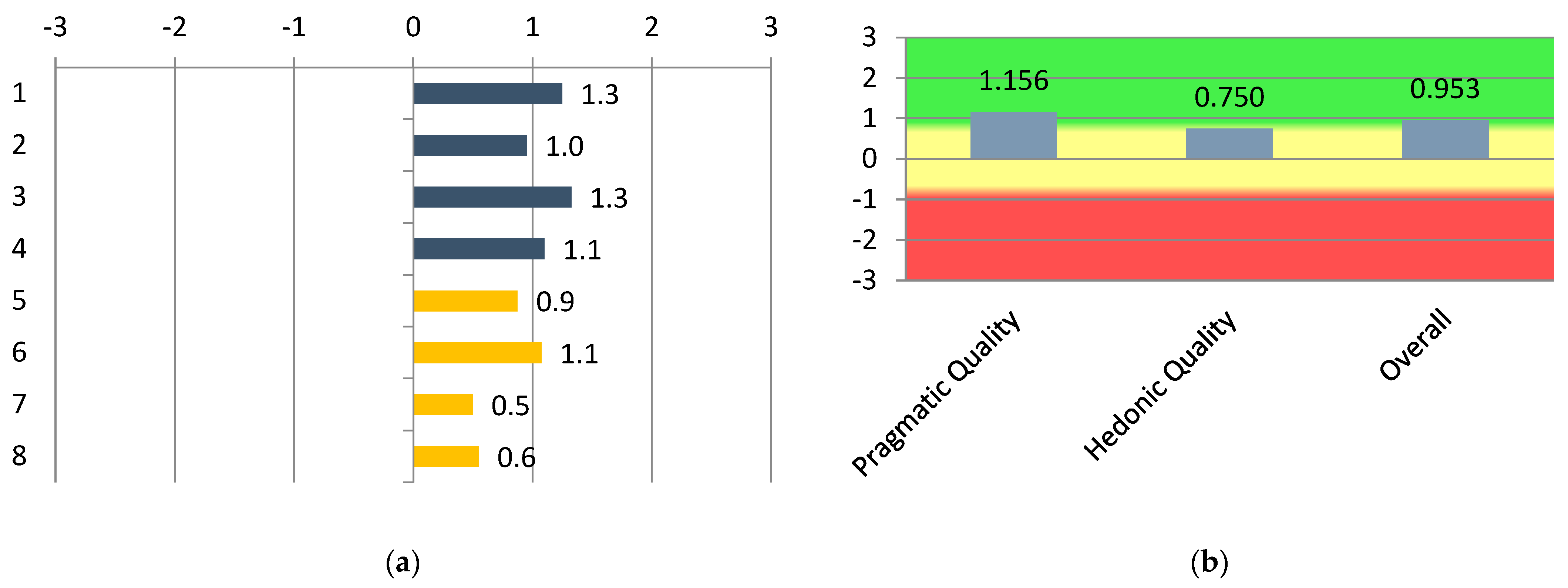

4.1. User Experience Evaluation with the UEQ-S

4.2. Identifying Useful and Pleasing Elements

- Search and Filtering, which included elements related to search, filtering, categories, and sorting.

- Navigation and Structure, which included elements related to menus, layout structure, tabs, and lists.

- Content Presentation, which included elements related to texts and descriptions and artwork image presentations.

- Interactivity, which included elements related to buttons, call to actions, popups, sliders, and interactive UI elements.

- Visual Design, which included elements related to colors, fonts, design choices, and branding.

- Design Style, which included elements related to colors, contrast, typography, and minimalism.

- Art Presentation, which included elements related to artwork images and textual information.

- Layout Aesthetics, which included elements related to structure, grid layouts, spacing, and clarity.

- Branding and Semiotics, which included elements related to logos, icons, and site identity.

- Movement and Interaction, which included elements related to motion like sliders, popups, or calls to action, like buttons.

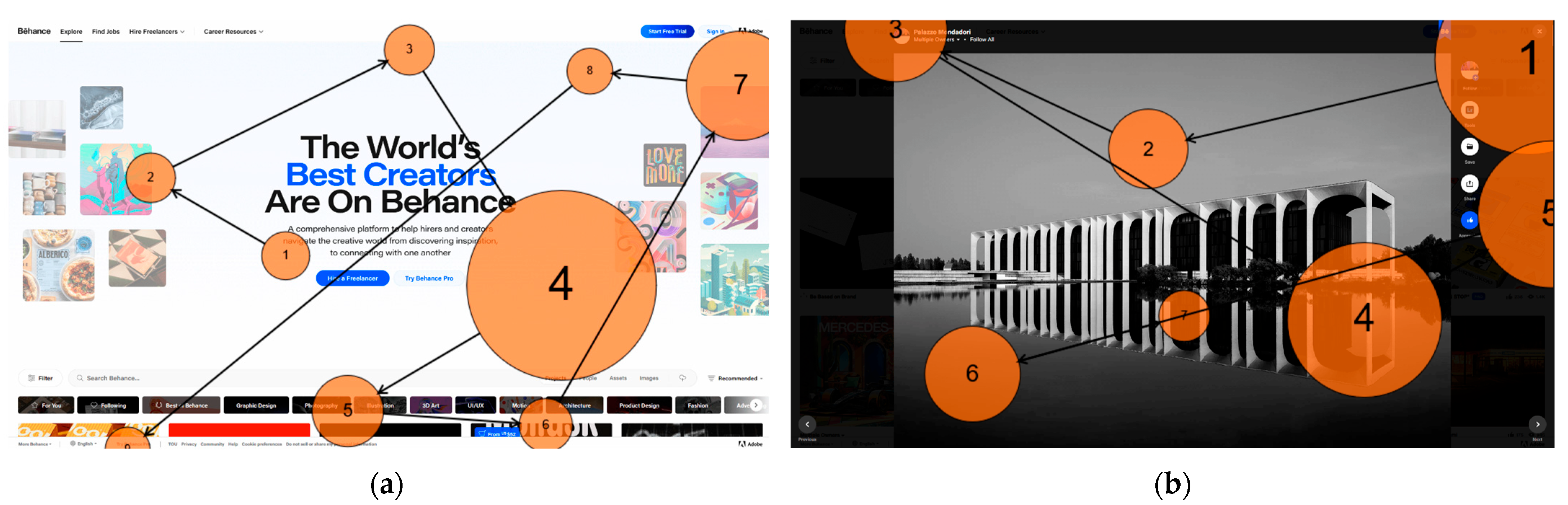

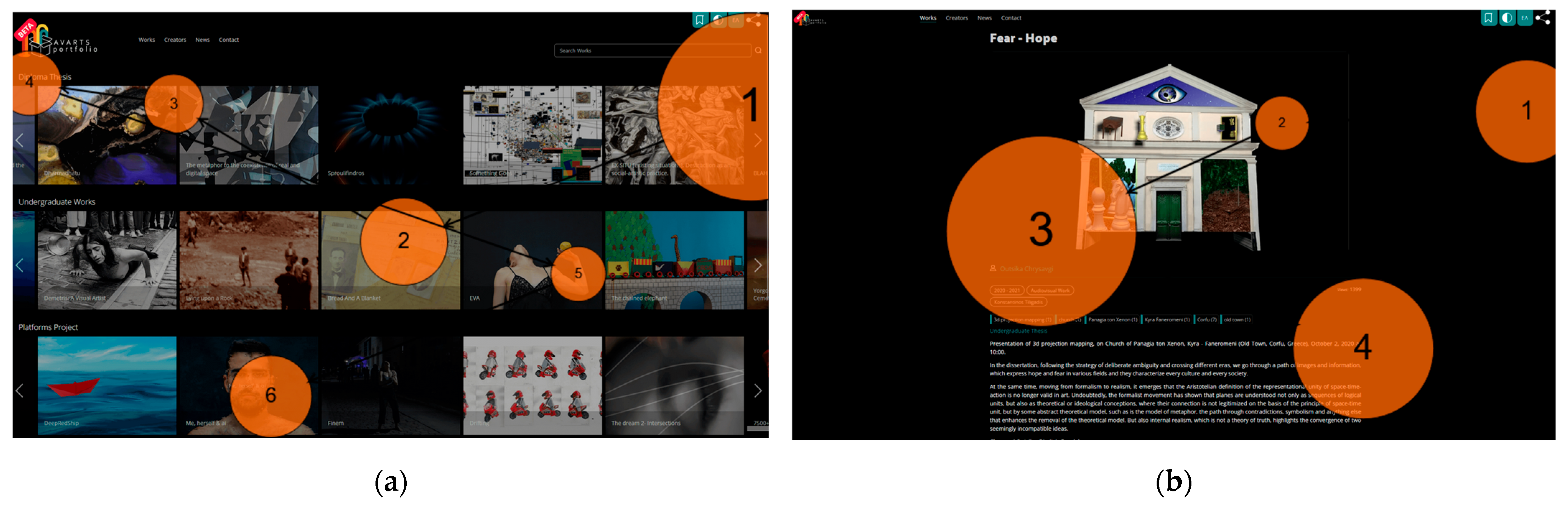

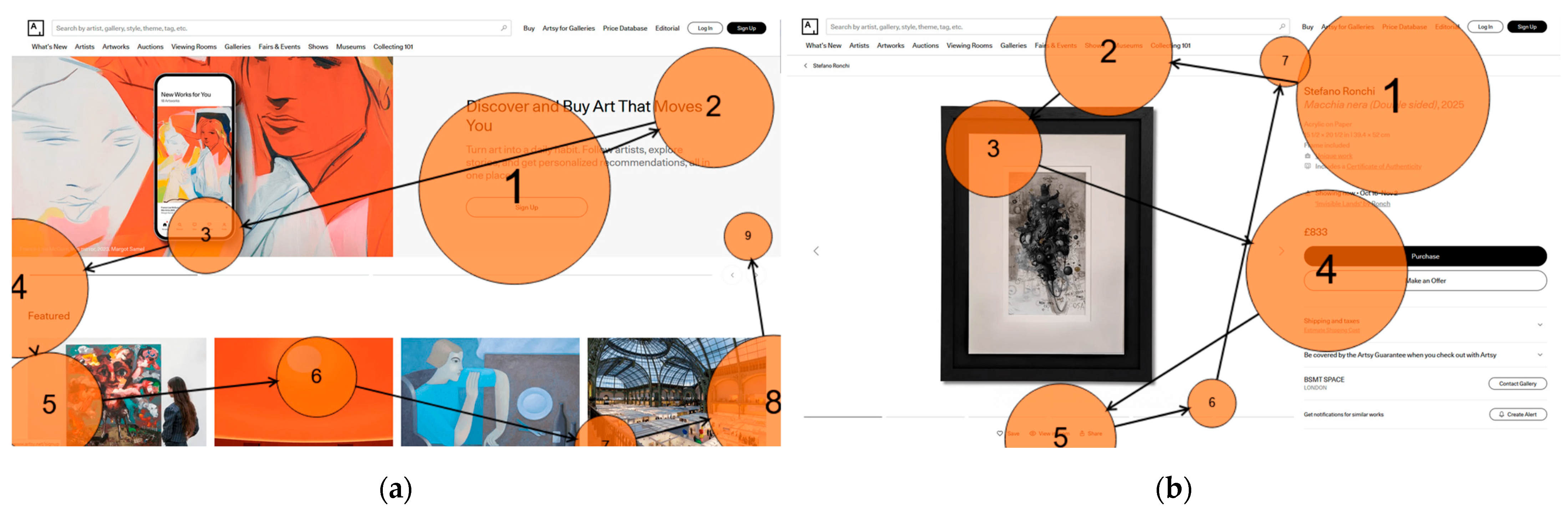

4.3. Attention Tracking

5. Discussion

5.1. RQ1. How Do Users Evaluate the Usability and Aesthetic Dimensions of Digital Art Repositories?

5.2. RQ2. Which Types of Interface Elements Do Users Tend to Consider: (a) the Most Useful or (b) the Most Aesthetically Pleasing in Digital Art Repositories?

5.3. RQ3. To What Extent Do Attention Patterns Align with or Deviate from Users’ Self-Reported Evaluations of the Usability and Aesthetics of Digital Art Repositories?

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alharoon, Dahlia, and Douglas J. Gillan. 2020. The relation of the perceptions of aesthetics and usability. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 64: 1876–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battarbee, Katja. 2003. Co-experience: The social user experience. In CHI’03 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 730–31. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockinton, Amanda, Sam Hirst, Ruijie Wang, John McAlaney, and Shelley Thompson. 2022. Utilising online eye-tracking to discern the impacts of cultural backgrounds on fake and real news decision-making. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 999780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, John. 1996. SUS: A quick and dirty usability scale. In Usability Evaluation in Industry. Edited by Patrick W. Jordan, Bruce Thomas, Ian Lyall McClelland and Bernard Weerdmeester. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis, pp. 189–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Fiona, and Sarah Kenderdine. 2007. Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage: A Critical Discourse (Media in Transition). Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connor Desai, Saoirse, and Stian Reimers. 2019. Comparing the use of open and closed questions for Web-based measures of the continued-influence effect. Behavior Research Methods 51: 1426–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, Charles J., Sharon P. Cooper, Deborah J. del Junco, Eva M. Shipp, Ryan Whitworth, and Sara R. Cooper. 2006. Web-based data collection: Detailed methods of a questionnaire and data gathering tool. Epidemiologic Perspectives & Innovations 3: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, Lee J. 1951. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16: 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, Karen, Ellen Berscheid, and Elaine Walster. 1972. What is beautiful is good. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 24: 285–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, Toshihisa, and Atsuo Murata. 2020. Comparative analysis of website usability between United States and Japan. In Advances in Physical, Social & Occupational Ergonomics. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Duchowski, Andrew T. 2017. Eye Tracking Methodology: Theory and Practice, 3rd ed. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert, Nico, Björn Scheppler, Kurt Ackermann, and Tim Geppert. 2023. QButterfly: Lightweight survey extension for online user interaction studies for non-tech-savvy researchers. Paper presented at 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany, April 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Elbabour, Fatma, Obead Alhadreti, and Pam Mayhew. 2017. Eye tracking in retrospective think-aloud usability testing: Is there added value? Journal of Usability Studies 12: 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ghidini, Marialaura. 2019. Curating on the web: The evolution of platforms as spaces for producing and disseminating web-based art. Arts 8: 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halstead, Susanne, Daniel H. Serrano, and Scott Proctor. 2015. Finding top ui/ux design talent on adobe behance. Procedia Computer Science 51: 2426–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Karolina, and Aleksandra Świderska. 2024. Integrating open-and closed-ended questions on attitudes towards outgroups with different methods of text analysis. Behavior Research Methods 56: 4802–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassenzahl, Marc. 2007. The hedonic/pragmatic model of user experience. Towards a UX Manifesto 10: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hassenzahl, Marc. 2010. Experience Design: Technology for All the Right Reasons. San Rafael: Morgan & Claypool. [Google Scholar]

- Hassenzahl, Marc. 2018. The thing and I: Understanding the relationship between user and product. In Funology 2: From Usability to Enjoyment. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 301–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hassenzahl, Marc, and Nina Sandweg. 2004. From mental effort to perceived usability: Transforming experiences into summary assessments. In CHI’04 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 1283–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hinderks, Andreas. 2017. Design and evaluation of a short version of the user experience questionnaire (UEQ-S). International Journal of Interactive Multimedia and Artificial Intelligence 4: 103–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmqvist, Kenneth, Marcus Nyström, and Fiona Mulvey. 2012. Eye tracker data quality: What it is and how to measure it. Paper presented at Symposium on Eye Tracking Research and Applications, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, March 28–30; pp. 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Holmqvist, Kenneth, Marcus Nyström, Richard Andersson, Richard Dewhurst, Halszka Jarodzka, and Joost Van de Weijer. 2011. Eye Tracking: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods and Measures. New York: OUP Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Hornecker, Eva, and Luigina Ciolfi. 2022. Human-Computer Interactions in Museums. Cham: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Jeff, Ryen W. White, and Georg Buscher. 2012. User see, user point: Gaze and cursor alignment in web search. Paper presented at SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Austin, TX, USA, May 5–10; pp. 1341–50. [Google Scholar]

- Katsaounidou, Anastasia, Paris Xylogiannis, Thomai Baltzi, Theodora Saridou, Symeon Papadopoulos, and Charalampos Dimoulas. 2025. An AI-Driven News Impact Monitoring Framework Through Attention Tracking. Societies 15: 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krug, Steve. 2014. Don’t Make Me Think, Revisited: A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability, 3rd ed. Indianapolis: New Riders. [Google Scholar]

- Kurosu, Masaki, and Kaori Kashimura. 1995. Apparent usability vs. inherent usability: Experimental analysis on the determinants of the apparent usability. Paper presented at Conference Companion on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, May 7–11; pp. 292–93. [Google Scholar]

- Laugwitz, Bettina, Theo Held, and Martin Schrepp. 2008. Construction and evaluation of a user experience questionnaire. In HCI and Usability for Education and Work. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yaxing, Joyce Karreman, and Menno De Jong. 2022. Cultural differences in web design on Chinese and Western websites: A literature review. Paper presented at IEEE International Professional Communication Conference (ProComm), Limerick, Ireland, July 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Peng, and Lan Lan. 2021. Museum as multisensorial site: Story co-making and the affective interrelationship between museum visitors, heritage space, and digital storytelling. Museum Management and Curatorship 36: 403–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, Paul F. 2007. Museum websites and museum visitors: Before and after the museum visit. Museum Management and Curatorship 22: 337–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marty, Paul F. 2011. My lost museum: User expectations and motivations for creating personal digital collections on museum websites. Library & Information Science Research 33: 211–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melissourgos, Georgios, and Christos Katsanos. 2025. UEQ-GR and UEQ-S-GR: Towards a Greek Adaptation of the User Experience Questionnaire and its Short Version. Paper presented at 3rd International Conference of the ACM Greek SIGCHI Chapter, Syros, Greece, September 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, Matthew B., Michael A. Huberman, and Johnny Saldaña. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Moshagen, Morten, and Meinald T. Thielsch. 2010. Facets of visual aesthetics. International Journal of Human–Computer Studies 68: 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshagen, Morten., and Meinald T. Thielsch. 2013. A short version of the visual aesthetics of websites inventory. Behaviour & Information Technology 32: 1305–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, Jakob. 2012. Usability 101: Introduction to Usability. Nielsen Norman Group. Available online: https://www.nngroup.com/articles/usability-101-introduction-to-usability/ (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Norman, Donald Arthur. 2004. Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Novák, Jakub Štěpán, Jan Masner, Petr Benda, Pavel Šimek, and Vojtěch Merunka. 2024. Eye tracking, usability, and user experience: A systematic review. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 40: 4484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoutsaki, Alexandra, Patsorn Sangkloy, James Laskey, Nediyana Daskalova, Jeff Huang, and James Hays. 2016. Webgazer: Scalable webcam eye tracking using user interactions. Paper presented at Twenty-Fifth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI’16), New York, NY, USA, July 9–15; pp. 3839–45. [Google Scholar]

- Parry, Ross. 2007. Recoding the Museum: Digital Heritage and the Technologies of Change. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pergantis, Minas, Laida Limniati, Aristeidis Lamprogeorgos, and Andreas Giannakoulopoulos. 2025a. AI powered user experience personalization in academic digital art repositories. In ICERI2025 Proceedings. Valencia: IATED, pp. 6781–89. [Google Scholar]

- Pergantis, Minas, Paris Xylogiannis, Nikos Vryzas, Symeon Papadopoulos, Andreas Giannakoulopoulos, and Charalambos Dimoulas. 2025b. UX Evaluation and Best Practices for Social Research Data-Collection Tools: The Case of iMedius FormBuilder: A streamlined methodology for evaluating the user experience of social research digital tools demonstrated through its application to the iMedius FormBuilder platform. Paper presented at 3rd International Conference of the ACM Greek SIGCHI Chapter, Syros, Greece, September 24–26; pp. 165–73. [Google Scholar]

- Rajeshkumar, Sugu, Ridha Omar, and Murni Mahmud. 2013. Taxonomies of user experience (UX) evaluation methods. Paper presented at 2013 International Conference on Research and Innovation in Information Systems (ICRIIS), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, November 27–28; pp. 533–38. [Google Scholar]

- Santoso, Harry B., and Martin Schrepp. 2019. The impact of culture and product on the subjective importance of user experience aspects. Heliyon 5: e02434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrepp, Martin, Andreas Hinderks, and Jörg Thomaschewski. 2014. Applying the user experience questionnaire (UEQ) in different evaluation scenarios. In Design, User Experience, and Usability: Theories, Methods, and Tools for Designing the User Experience. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Shneiderman, Ben, Catherine Plaisant, Maxine Cohen, Steven Jacobs, Niklas Elmqvist, and Nicholas Diakopoulos. 2016. Designing the User Interface: Strategies for Effective Human-Computer Interaction, 6th ed. London: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Sidorova, Elena. 2019. The Cyber Turn of the Contemporary Art Market. Arts 8: 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terras, Melissa. 2011. The digital wunderkammer: Flickr as a platform for amateur cultural and heritage content. Library Trends 59: 686–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tractinsky, Noam, Adi S. Katz, and Dror Ikar. 2000. What is beautiful is usable. Interacting with Computers 13: 127–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trant, Jennifer. 2009. Emerging convergence? Thoughts on museums, archives, libraries, and professional training. Museum Management and Curatorship 24: 369–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsita, Christina, Maya Satratzemi, Alexandros Pedefoudas, Charalambos Georgiadis, Maria Zampeti, Evi Papavergou, Syrago Tsiara, Eleni Sismanidou, Petros Kyriakidis, Dionysios Kehagias, and et al. 2023. A virtual reality museum to reinforce the interpretation of contemporary art and increase the educational value of user experience. Heritage 6: 4134–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Țichindelean, Mihai, Monica Teodora Țichindelean, Iuliana Cetină, and Gheorghe Orzan. 2021. A Comparative Eye Tracking Study of Usability—Towards Sustainable Web Design. Sustainability 13: 10415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | URL | Short Description |

|---|---|---|

| Behance Creative Network | https://www.behance.net/ (accessed on 15 November 2025) | A community-oriented repository hosting crowd-sourced artworks from people trying to showcase their work |

| Avarts Art Portfolio | https://portfolio.avarts.ionio.gr/en/ (accessed on 15 November 2025) | A higher education institution portfolio for students and faculty members hosting works produced through the academic process |

| Artsy Online Marketplace | https://www.artsy.net (accessed on 15 November 2025)/ | An online art marketplace hosting professional works from galleries and individual artists for sale or auction |

| # | Left Term (1) | Right Term (7) | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | obstructive | supportive | Pragmatic Quality |

| 2 | complicated | easy | Pragmatic Quality |

| 3 | inefficient | efficient | Pragmatic Quality |

| 4 | confusing | clear | Pragmatic Quality |

| 5 | boring | exciting | Hedonic Quality |

| 6 | not interesting | interesting | Hedonic Quality |

| 7 | conventional | inventive | Hedonic Quality |

| 8 | usual | leading edge | Hedonic Quality |

| Behance | Avarts | Artsy | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pragmatic | Hedonic | Pragmatic | Hedonic | Pragmatic | Hedonic | ||||||

| Items | Correlation | Items | Correlation | Items | Correlation | Items | Correlation | Items | Correlation | Items | Correlation |

| 1.2 | 0.57 | 5.6 | 0.72 | 1.2 | 0.45 | 5.6 | 0.80 | 1.2 | 0.54 | 5.6 | 0.85 |

| 1.3 | 0.70 | 5.7 | 0.36 | 1.3 | 0.54 | 5.7 | 0.72 | 1.3 | 0.74 | 5.7 | 0.48 |

| 1.4 | 0.71 | 5.8 | 0.49 | 1.4 | 0.74 | 5.8 | 0.80 | 1.4 | 0.53 | 5.8 | 0.37 |

| 2.3 | 0.48 | 6.7 | 0.51 | 2.3 | 0.48 | 6.7 | 0.68 | 2.3 | 0.57 | 6.7 | 0.57 |

| 2.4 | 0.67 | 6.8 | 0.55 | 2.4 | 0.59 | 6.8 | 0.72 | 2.4 | 0.68 | 6.8 | 0.48 |

| 3.4 | 0.64 | 7.8 | 0.81 | 3.4 | 0.59 | 7.8 | 0.75 | 3.4 | 0.73 | 7.8 | 0.72 |

| Average | 0.63 | Average | 0.57 | Average | 0.56 | Average | 0.75 | Average | 0.63 | Average | 0.58 |

| Alpha | 0.87 | Alpha | 0.84 | Alpha | 0.84 | Alpha | 0.92 | Alpha | 0.87 | Alpha | 0.85 |

| Repo | Search and Filtering | Navigation and Structure | Content Presentation | Interactivity | Visual Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behance | 10 | 7 | 5 | 12 | 5 |

| Avarts | 10 | 13 | 9 | 3 | 4 |

| Artsy | 8 | 4 | 12 | 8 | 4 |

| Repo | Design Style | Art Presentation | Layout Aesthetics | Branding and Semiotics | Movement Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behance | 18 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| Avarts | 10 | 12 | 4 | 7 | 4 |

| Artsy | 15 | 14 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pergantis, M.; Katsaounidou, A.; Lamprogeorgos, A.; Giannakoulopoulos, A. Aesthetics and Usability in Digital Art Repositories: Using the iMedius Platform to Collect User Feedback Through Attention Tracking. Arts 2026, 15, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts15010009

Pergantis M, Katsaounidou A, Lamprogeorgos A, Giannakoulopoulos A. Aesthetics and Usability in Digital Art Repositories: Using the iMedius Platform to Collect User Feedback Through Attention Tracking. Arts. 2026; 15(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts15010009

Chicago/Turabian StylePergantis, Minas, Anastasia Katsaounidou, Aristeidis Lamprogeorgos, and Andreas Giannakoulopoulos. 2026. "Aesthetics and Usability in Digital Art Repositories: Using the iMedius Platform to Collect User Feedback Through Attention Tracking" Arts 15, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts15010009

APA StylePergantis, M., Katsaounidou, A., Lamprogeorgos, A., & Giannakoulopoulos, A. (2026). Aesthetics and Usability in Digital Art Repositories: Using the iMedius Platform to Collect User Feedback Through Attention Tracking. Arts, 15(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts15010009