1. Introduction

Year after year, the digital environment has been increasingly enabling the reconstruction of individual cultural objects as well as entire museum complexes. Several factors drive this process, ranging from documentation and the possibility of subsequent contactless study (

Bitelli et al. 2025) to the creation of virtual exhibitions and tours (

Bowen et al. 2013).

Museums had already undergone a paradigm shift from collection-centric to user-centric in the context of human participation and interaction (

Giannini and Bowen 2022). As the modern viewer is no longer confined to the role of passive recipient of narrative but instead seeks interactive engagement and aim to understand art, history, and science through direct interaction, the immersive component has come to the forefront. One cannot help but agree with research suggesting that museums equipped with new technologies should not merely display their objects and provide specialists with access to maximum possible information about their collections. At present, museums must integrate these elements into a richer flow of information, make them visible to broader audiences, and establish conditions for a sustained dialogue (

Aristova et al. 2020). Special effects that create an illusion of presence or time travel prove particularly effective in attracting new visitors and encouraging regular attendees to discover something new within permanent exhibitions (

Giannini and Bowen 2019;

Li et al. 2020). The digitization of collections allows museums not only to increase the number of people interested in and studying the objects (

Resta and Dicuonzo 2024), expand their exhibition capabilities (

Carrozzino and Bergamasco 2010), but also to use visualization as a method for audiences to study and understand physical artifacts (

Li et al. 2020;

Ai et al. 2025). Thus, the digitization of collections and their visualization are an essential step towards museums having a presence in today’s digital environment (

Aristova et al. 2020;

Giannini and Bowen 2022).

The variability of concepts for virtual spaces and the creativity behind their artistic and visual solutions make it impossible to speak of any formalization or standardization of approaches. The virtualization of museums is in a phase of active development, with institutions seeking relevant and original forms. At the same time, the number of projects dedicated to the reconstruction of past museum expositions is not as substantial as one might hope. Most often, museums focus on digitally reconstructing their interiors to attract audiences unable to visit in person (

Ai et al. 2025). Occasionally, digital content serves as a memorial in contemporary history—for example, through the analysis of images posted by Instagram users following the fire at Rio de Janeiro’s National Museum in September 2018 (

Beiguelman and Lavigne 2022). An important role of visualization is to reproduce things that cannot be observed in the real world by computer. A practical example of time travel achieved through complex visual perception is demonstrated in the implementation of a virtual reproduction of the Yamahoko Parade of the Gion Festival (

Li et al. 2020). The concept articulated in the early days of accessible digital museum content—that “Reproduction reassembles the broken bits into one meta-tradition of style, a new Museum without Walls” (

Foster 1996) inspires projects aimed at digitally reconstructing museum histories.

The large-scale virtualization of museums raises key questions: when, how, and in what form should institutions join this process? How can they ensure their presence in the virtual universe is enduring and meaningful—not a one-time event but a sustained virtual existence? The trigger for launching a virtual project is always unique, combining factors such as development strategy dynamics, event calendars, funding availability (

Raimo 2022), personal initiative by curators and developers, or external circumstances like building renovations, collection relocations, or major exhibition overhauls. Creating a comprehensive virtual identity for a museum requires developing and continuously updating strategies to establish and maintain new digital spaces for visitor engagement, a cohesive artistic approach to their design, cutting-edge technological solutions, and the sustained vitality of the virtual experience.

As new digital devices that magnify our senses are created and more frequently worn, this will affect both the way exhibitions are designed and communicated as it will human behavior (

Giannini and Bowen 2019). Failure to embrace new digital trends runs the risk of leaving the museum as a conservative institution, drifting in complete isolation from the digital ecosystem. Artistic expressiveness is not merely a tool for articulating uniqueness and individuality; it is one of the most direct pathways to the human heart and emotions. In this sense, digital art—despite its technological transformation—inherits this tradition of direct engagement. Exploring the relationship between this evident continuity and modern technological capabilities proved to be a compelling and significant aspect of the project’s concept.

This article explores an approach to reconstructing the appearance and content of one of the universal museums: the Kunstkamera of Peter the Great. In the Renaissance period, ‘curiosity’ or ‘wonder’ played an operative part for museums (

MacGregor 2020). Talking about the early universal museum, we envision first the universe in one room. In general, the idea of the Russian Kunstkamera was focused on the same encyclopedic nature and desire for universal coverage of all human knowledge in the range “from A to A”, i.e., from anatomy (as deeply internal) to astronomy (as extremely external) (

Golovnev 2020).

The Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, named today in honor of Emperor Peter I, is also engaged in the study of 18th-century science as part of its history. Founded in 1714, the museum began when Peter’s personal collection of curiosities, his library, and the “naturalia” collection of the Apothecary Chancery were transported from Moscow to his Summer Palace. The Kunstkamera building itself was begun in 1718, designed by G. J. Mattarnovi. However, the architect died in 1719, and construction was continued by others—first Nicolaus Friedrich Härbel, then Gaetano Chiaveri, and later Mikhail Zemtsov. The vicissitudes of the construction history of the Kunstkamera led to the fact that the building, completed only in the 1730s, differed from Mattarnovi’s original vision. While the iconography of the Kunstkamera before the fire of 1747 contains about a dozen images—drawings and engravings, Mattarnovi’s design is represented by but a single architectural blueprint—and at that, a 1746 copy, not the original. Comparing this blueprint with the earliest post-construction depiction—a 1724 drawing by Christophor Marselius—it is clear that changes and additions were made to the project in the very first years of construction (

Ukhnalev 2020). The tower underwent the most significant transformation. Ongoing research into the museum’s architectural history continues to address these questions despite limited source material.

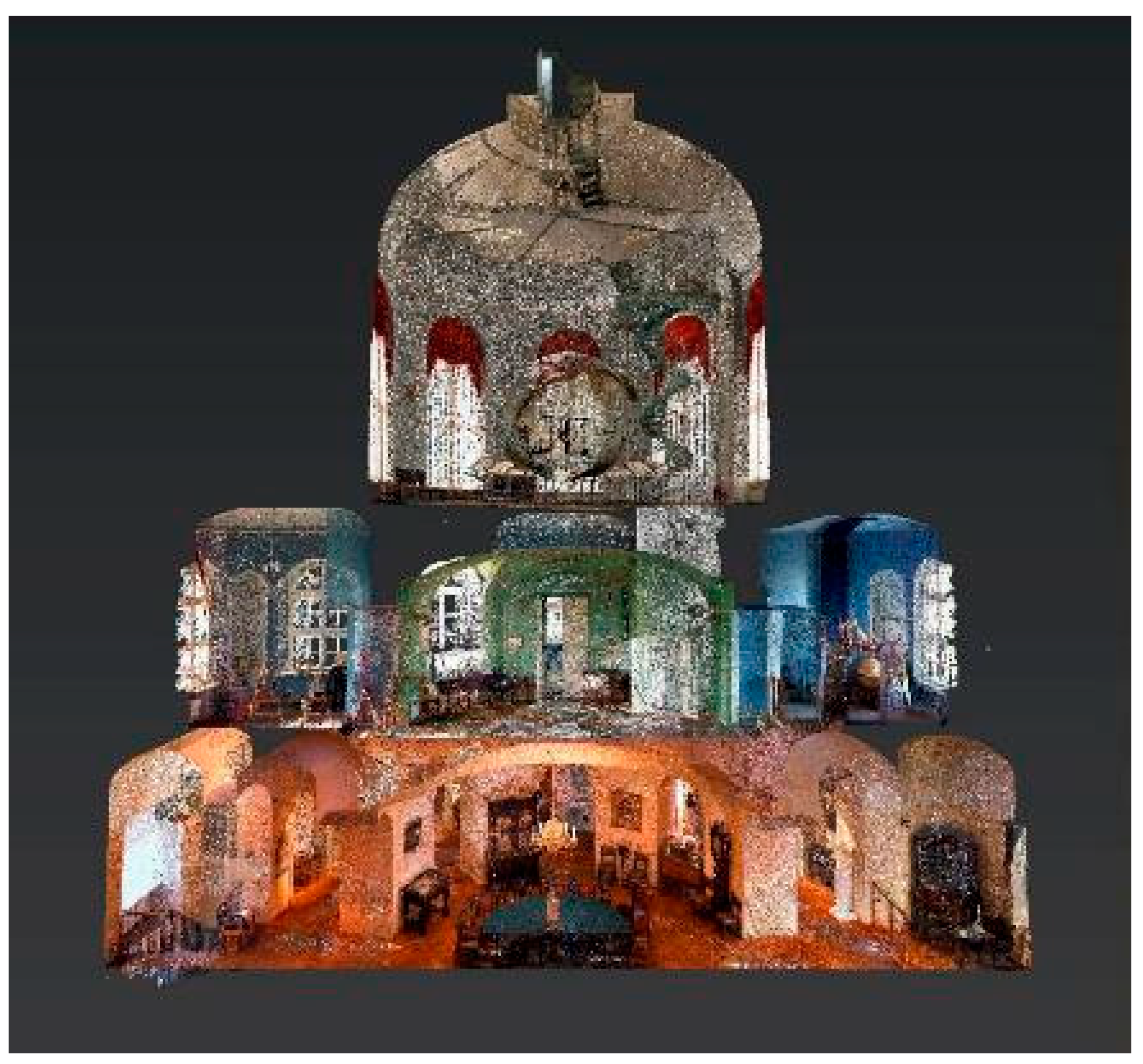

The Kunstkamera, as both a building and a museum, has existed for over three centuries, undergoing numerous transformations that have altered its exterior, interiors, and the scope, composition, and structure of its collections,

Figure 1. When talking about the virtual reconstruction of the Kunstkamera of the 18th century we must address both the limited (by modern standards) information about the early museum collections, and the actual composition of artifacts that have survived to the present day. The first catalogs of the Kunstkamera’s holdings were created after the museum relocated to its new building on Vasilievsky Island in St. Petersburg. Professors and adjuncts of the Academy of Sciences, founded in 1724, compiled these catalogs. One of the first was a catalogue of the anatomical collection with a list of items in nineteen cabinets. The catalogue was not only topographic, but also, first and foremost, a scientific description of the collection. The author of the catalogue was Josias Weitbrecht (

Kopaneva 2024). Long-standing interest in the illustrated catalogues of European universal museums led researchers to a project to attribute and analyze more than 2000 sheets, which were called The Paper Museum of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg. Images include drawings of the two buildings of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg and drawings of the objects that were on display in the Kunstkamera (

Kistemaker et al. 2005). It was these materials that became the basis for the virtual images of the project.

Gradually, in strategic terms, the culture of curiosity within museums began to give way to a systematic, universal presentation of knowledge (

MacGregor 2020). Without studying the processes of the past, it is difficult to understand a museum’s present or envision its future. Today, we believe that visitors’ curiosity can be satisfied by reimagining the concept of “cabinets of curiosities”. In this context, the virtual reconstruction of the 18th-century Kunstkamera can once again embody the idea of a universe in one room—both in essence and in the administrative decisions required to create such a reconstruction.

Multi-sensory interaction can provide users with a spectacular immersive feeling (

Li et al. 2020). Material museum collections, in turn, are best perceived when considering their size, shape, color, texture, materials, and the space they occupy within museums (

Giannini and Bowen 2022). Consequently, an increasing number of projects in virtual spaces are turning to collaboration with digital artists.

Over its 300-year history, the Kunstkamera has developed a distinct, recognizable, and enduring identity as Russia’s first museum (

Golovnev et al. 2022). Recreating in digital space, if not the full cycle of museum knowledge formation, then at least documenting it, could elevate research within the museum and deepen public understanding of how this cultural institution functions (

Trant 2007). The idea of a documentary-artistic reconstruction of the 18th century museum was realized in 2022 and 2023 by the Kunstkamera’s Laboratory of Museum Technologies

1.

For researchers investigating the history of the Kunstkamera and its early holdings, reconstruction offers a method to systematize and visualize their findings regarding the composition and spatial layout of these collections. It also helps illustrate the architectural design of the exhibition spaces, including their decorative elements and display furnishings. For the public, the appeal of the virtual reconstruction lies in the opportunity to immerse themselves in the atmosphere of Russia’s first museum as it can be presented based on historical documents, and to compare it with the museum’s current state.

This study combines cost-effective digital reconstruction methods with interdisciplinary design methodologies to address both technical and humanistic challenges in academic museums’ digital transformation efforts. The research is guided by these key questions:

How can we accurately reconstruct a museum’s appearance and exhibitions with limited source materials?

How can the reconstruction process be consistent with the historical image of the museum and its digital strategy?

2. Results

This article outlines a methodology that can be used to reconstruct museum exhibitions of the past. The processes adopted in administrative management, procedural sequencing, design decisions, and web development produced accurate results both geometrically and colorimetrically. The precision of the resulting visuals fully met the museum’s requirements and provides viewers with an accurate representation of the Kunstkamera exhibition as it appeared in the 18th century. This aligns with the project’s overarching goals at this stage—namely, an artistic and documentary reconstruction based on available historical sources.

A large part of the work involved preparing the digital database. Digitization of museum objects, research into archival documentation, architectural development, and design solutions were all carried out by the Kunstkamera’s Museum Technology Laboratory. This approach addresses issues related to museum bureaucracy, object preservation, and information management; furthermore, it ensures a coherent strategy for building the museum’s digital collections.

The digitization of historical materials involves converting them into a format that enables the application of a broader spectrum of technologies. Visual technologies constitute a crucial component of the contemporary museum toolkit. In the context of this project, the creation of a digital archive of models covering the Kunstkamera’s early formation period—ranging from the general to the specific (from architecture to individual artifacts)—allows for its utilization in a wide array of applications. These span from scholarly research to the generation of diverse visual content for a broad audience.

The artistic-visual solution is no less important, as it relates to the historically established image of the Kunstkamera. It should complement this image organically and, ideally, serve as a continuation of the real-world museum in virtual form. This is something the museum prefers to keep within its institutional purview to maintain full control over the specific strategy for conceptualizing virtuality within the Kunstkamera.

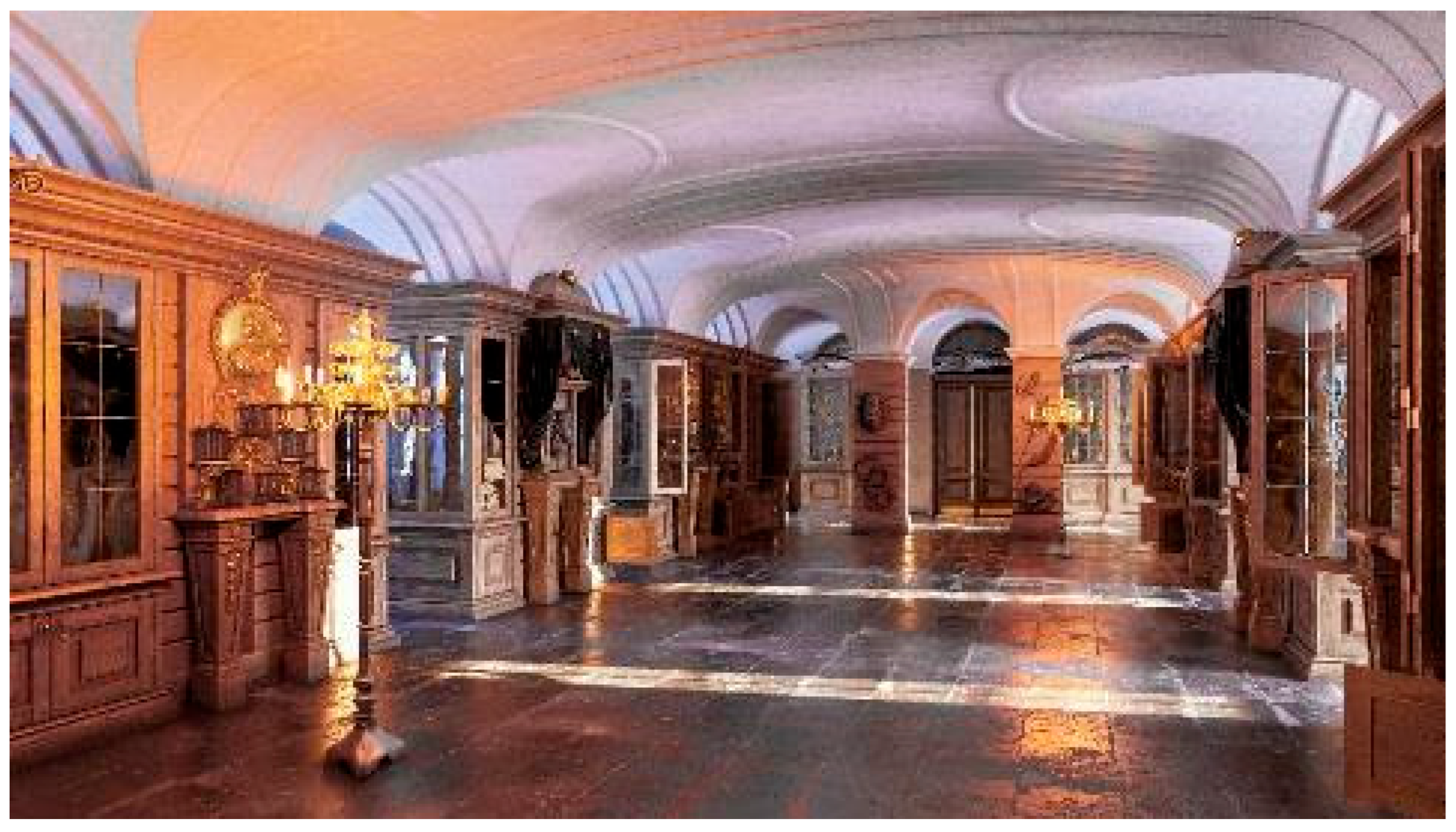

Ultimately, the level of detail obtained allowed us to recreate the atmosphere and entourage of the exhibition halls of the 18th century. Moreover, all post-processing operations were implemented using open source and/or free software.

On the other hand, there was no shortage of problems and difficulties in the workflow of recreating the museum’s exhibits. For example, some objects in historical engravings were drawn without detail, which required additional research by architectural historians on 18th-century objects in St. Petersburg. Objects with shiny surfaces caused problems in digitization. In terms of modeling, special attention was required for objects that are no longer in the collection today.

Additionally, the operations conducted required in-depth knowledge of 3D modeling procedures, and the algorithms used. Similarly, historical expertise was essential throughout the process to ensure procedural accuracy and to analyze and interpret the digital results. This consideration was crucial, and the outcomes confirmed that an interdisciplinary approach is fundamental in the field of digitization, particularly in the delicate context of cultural heritage objects.

3. Discussion

The involvement of designers who have studied the museum’s artistic image through historical documents raises issues beyond mere technology or reconstruction software; it highlights the humanistic aspect of engaging the viewer through the project’s artistic quality and expressiveness.

The problem of limited sources in virtual reconstruction of early periods for historical and cultural monuments whose existence spans several centuries and encompasses numerous and diverse events can be considered universal. However, strategies and methods for resolving this problem remain strictly individual. In the case of the Kunstkamera project, the confluence of available materials, museum strategy, and the expertise of the core team gave rise to a “documentary-artistic” approach. In this sense, the project expands the spectrum of approaches to virtual museum practice. Even if it does not explicitly claim to establish a new format characterized as “artistic documentary,” it undoubtedly takes a step in that direction.

The case study presented in this article demonstrates how digital museum technologies can better showcase tangible and intangible culture to the world.

Through such projects, museums can also articulate their stance regarding virtual reconstruction and digital artistry in the museum sphere. What might this stance entail, and what understanding of digital art in this field can be conveyed to the audience? The spectrum of virtual reconstructions in the museum sector is extraordinarily broad. To de-fine the Kunstkamera project’s place within this landscape, it is useful to establish certain coordinate axes. The first is the axis of the “reconstruction object”—ranging from a single artifact to an entire civilization. The second is the axis of technology and presentation formats, ranging from static reconstructions (renders) to dynamic mixed reality (MR). The third (and primary) axis concerns the project’s goals and areas of application, spanning scholarly research, education, and knowledge dissemination to heritage preservation.

We hope, alongside museum specialists from various countries, that the digital museum will fully utilize digital technologies as its infrastructure and integrate digital archives from diverse communities. Furthermore, digital museums are not merely tools employing advanced information technologies to preserve and display the resources of traditional museums; they represent a new form of museum existence. Today, it is becoming evident that a museum can achieve its core objectives only through a continuous dialogue with the viewer or researcher, a dialogue that must be conducted using the most up-to-date technological tools. Through the digitization of collections and their visualization in virtual space, the museum provides researchers with yet another modality of engagement with objects. This is particularly relevant for the comprehension and study of three-dimensional objects. Expanding exhibition capacities by presenting digitized objects in a virtual environment—making them accessible, including during visits to the museum itself—is also pertinent for museums housed in historic buildings. Furthermore, the role of digitization in preserving museum collections should not be overlooked. The accessibility of data and the minimization of object handling following high-quality digitization con-tribute to the foundations of museum practice amid growing public interest in the study of history, culture, and the arts.

In conclusion, the concept of a universe within a single room, which gave rise to a universal museum like the Kunstkamera, has evolved into the creation of the Laboratory of Museum Technologies, enabling the development of complex technological projects within the museum itself. Indeed, this article highlights that architectural and object design, combined with museology, can yield excellent results in enhancing the dissemination of cultural heritage and offering new narrative strategies for museum visitors. The culture of curiosity that gave birth to the museum can be sustained in a modern context by narrating the museum’s history through 3D reconstructions. A virtual tour exploring the origins of Russia’s first museum could, in the future, serve as a research laboratory for the history of science and museology during the Enlightenment era and recreate events from various epochs, as is done in other projects dedicated to reconstructing the past.

4. Materials and Methods

The reconstruction for the project “Digital Kunstkamera of the 18th Century” was based on a diverse corpus of sources and emerged from scholarly historical-architectural and museological research, including the history of the formation of the museum’s collection and its systematization (

Kukanov 2024). Claiming documentary accuracy for a reconstruction would have been impossible without taking archival documents into consideration. While limitations on the use of historical materials in digital projects certainly exist, they do not differ from those inherent in any work involving historical sources. In our project, we relied both on our own materials and on third-party materials for which appropriate usage permissions were secured. To balance artistic solutions with the preservation of the museum’s enduring identity, the project team took into account the broad context of historical information about the first Russian museum and the early “wunderkammers” of Europe. Most of the work was carried out by the staff of the Kunstkamera Museum Technology Laboratory, who, through years of creating the museum’s exhibitions, had developed an audiovisual language for interpreting the Kunstkamera (

Kukanov and Konkova 2021). By keeping the project in-house with minimal outsourcing, the team also ensured strict adherence to museum protocols regarding access to artifacts and the use of related information.

The project involved specialists of various profiles: historians, museum workers, specialists in the history of architecture of the 17th–18th centuries, architects and designers, and specialists in the field of 3D modeling. Part of the work was delegated to third-party contractors, in particular specialists in the field of photogrammetry, 3D scanning and video production, web design and website development.

Faced with a choice between two poles—strict but objectively and substantially limited documentary rigor on one side, and artistically enriched imagery on the other—the project participants gravitated toward the latter. Consequently, details became paramount: architectural and furnishing materials, textures, chiaroscuro, and so forth. It is worth remembering that the scientific institution established in St. Petersburg in the 18th century, which housed the Kunstkamera, was known at the time as the “Academy of Sciences and Arts.” In doing so, it asserted a claim over the entire spectrum of worldly phenomena, ranging from scientific facts to artistic works.

The “documentary–artistic” scale within the project can be visualized as a vector of movement from the exhibit through museum equipment to architecture. On this scale, the artifact is represented by a documentary digital reproduction, whereas its surroundings—comprising furnishings, interiors, and architecture—were reconstructed to varying degrees using artistic techniques.

Work progressed simultaneously across several fronts: studying museum collections and preparing digital content, 3D modeling of the building and its interiors, designing virtual representations of the museum’s artifacts, creating a virtual tour scenario, and launching the project website. For this article, the key phases of work have been grouped thematically as follows: “Museum Related”, “Digital” and “Virtual”.

4.1. Museum-Related

A scenario for visiting the 18th-century Kunstkamera was developed. This included descriptions of each hall’s purpose, contents, and atmosphere, the visitor’s virtual movement and interactions, points of interest, and key objects or exhibits.

Specialists compiled a list of exhibits and the composition of collections as they existed in the mid-18th century, drawing on current research in the field of museum history. Documents preserved in the museum and other organizations allowed us to partially reconstruct the topography of the museum objects in the 18th century exhibition. The architecture of the buildings, the decor of the facades and the arrangement of the museum interior required separate research investigations. Some artistic decisions were based on comparative analysis of early 18th-century architectural landmarks in St. Petersburg.

Museum staff authored and edited texts describing the objects used to populate the virtual 18th-century Kunstkamera exhibits. For their part, the museum’s conservation team prepared artifacts for digitization, including restoring particularly valuable items.

The project participants identified features and decorative elements where images were insufficiently detailed or for which there was no graphic information at all. Even with minimally informative primary documents, facade sculptures, bas-reliefs on pediments and similar elements were worked out in detail. Their digital recreation drew upon historical documents and examination of similar period buildings preserved in St. Petersburg.

4.2. Digital

Creating a digital image of the 18th century Kunstkamera required digitizing a variety of materials and objects. Only rooms for which historical data was available were selected for scanning and subsequent digital reconstruction. For the reconstruction of the museum’s architectural volume, laser scanning of the Kunstkamera’s premises was conducted. The current version of the digital reconstruction covers a total area of 2000 square meters. Based on a dense cloud of points,

Figure 2, employees of the Laboratory of Museum Technologies carried out the drawing of plans, cross-sections, and room sections in their current state. Digital removal of later architectural solutions that had accumulated over the building’s lifetime was also performed. As a result, it became possible to determine the dimensional parameters of the 18th-century spaces.

Images of the facades of the Kunstkamera on engravings that were published 1741, as well as watercolors and drawings with museum furnishings and elements of interior decor were scanned from the collection of the Museum of the Academy of Arts. After digitization in raster format, the images were processed using Adobe software. The curvature of the drawings was corrected, and the graphic field was cleaned.

Subsequent alignment of vector section images from the album of engravings in the Academy of Arts Museum collection with processed laser scanning data was undertaken, with correction and coordination of dimensions,

Figure 3. In the final stage, the engravings were drawn in vector format using AutoCAD 2021.1 and Corel Draw 2021 V.23.1.0.389.

In addition to spatial design, photographing and image processing of textures on surfaces that original have survived to the present day was conducted. Texture maps were ultimately compiled using reflection maps and relief maps (e.g., for stone floors).

Textured replicas were also prepared for exhibits from the earliest museum collections,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. Separately, videography of exhibits that cannot technically be converted to digital form through photogrammetry was performed. This, for instance, was the case with items with shiny metal and glass surfaces,

Figure 6. The criteria for selecting items for digitization included their physical preservation, as well as the availability of visual representations and references in historical documents. Based on analysis of drawings, historical descriptions and other sources, project participants modeled images of artifacts that have not survived to the present.

The architecture and interior space of the museum were modeled in AutoCAD using solid modeling. The development of decorative elements was carried out in ZBrush, 3D Max. OBJ (Wavefront Object) and FBX (Filmbox) formats were used to prepare the images of elements such as enclosing structures, windows, doors, railings, museum exhibit furnishings and lighting. The assembly of parts, texturing and rendering of images was carried out using Lumion 12 pro software by Act-3D,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

4.3. Virtual

The virtual tour was developed in stages that were outsourced. These stages included the development of the engine for the virtual tour, the logic of movement through the interior space of the virtual museum and the site space, the development of animation for the site, interface design, digitalization of 360° panoramic points for the virtual tour, and post-production and assembly of the virtual tour. Some key technical solutions that helped achieve the project’s goals while balancing budget limitations and historical accuracy requirements are described below:

JavaScript was chosen as the main programming language for the project. The developers used the Three.js library as a 3D engine. The panoramic scenes, 3D viewer and the main overview scene with the Kunstkamera were built using a combination of rendering engines—CSS Matrix and WebGL. The main framework used was the SvelteKit product, which allows one to use JS, HTML and CSS to create web interfaces. The GSAP library was used to animate part of the interface and camera fly-throughs, while other interface elements were animated using SvelteKit ver. 1.27.6.

Users do not like waiting a long time for websites to load. The ability to load websites depends largely on users’ devices and the speed of their internet connection. The total weight of the original media content, including audio, video, photos, 360 panoramas and 3D models, was too large and would not allow all materials to load quickly enough. Therefore, it was decided to optimize all materials so that users could immerse themselves in the atmosphere of the Kunstkamera with an acceptable waiting time.

Compression and optimization were used as much as possible for all media files. Compression was applied to 360° panoramas, photo and video content, for photogrammetry of 3D models, and for the main model of the Kunstkamera. The 3D models were packed into GL Transmission Format (glTF) and the geometry was compressed using Draco Compression ver. 1.5.6. The total weight of the models was, after optimization, reduced from 2.28 GB to 46.7 MB. 360° panoramas were packed into Khronos Texture Container v2 (KTX2). The total weight of the panoramas was, after optimization, reduced from 1.44 GB to 272.2 MB. Video was compressed and converted to mp4; photos were compressed and converted to WebP. The total weight of photos and videos was, after optimization, reduced from 6.54 GB to 110.7 MB. The main 3D model of the Kunstkamera weighed 1.34 GB; after retopology and optimization it was 6.13 MB. The video was optimized using ffmpeg 8.0. The developer used Adobe Photoshop to optimize photos and renders.

Custom sound effects were recorded for the audio accompaniment to create fuller immersion in the atmosphere: the clinking of coins; sounds for glass exhibits—such as Roux flasks; as well as for paper artifacts and metal objects like scalpels, rings, clips, and knives.

The developers recorded the sounds of opening toolboxes, drawers, and cabinet doors. They also added the sounds of pages turning in the library and the crackling of candles in various rooms. Footsteps were recorded for interiors and even for a spiral staircase. They were developed with different reverberations depending on the room size, and with varying sound textures based on the type of flooring. Voices of people were also added to the interior spaces. The main scene featuring the Kunstkamera building includes the sounds of the river and moving air masses. Inside the panoramas, a developer implemented spatial audio. For example, when a user moves between navigation markers, the sound of burning candles and other ambient noises remain fixed in place.

Each scene contains several navigation points, which are located according to their rendering locations, so the user does not just watch the transition animation but actually moves in the virtual space between the points.

The following actions were performed with respect to working with images and volumetric models. On pages with a general view of the Kunstkamera, work was performed with real-time shadow rendering, flying particles were configured, exponential fog was set, reflection maps and lighting were configured. In the component for viewing photogrammetric models, lighting was configured, as well as a small mirror podium for exhibits. GPU memory cleaning was configured when unmounting components with 3D visualizations. Work with 3D models was performed in the free open-source Blender ver. 3.6 software, which provides a wide range of tools for 3D modeling, animation, visualization, and other tasks related to 3D graphics.

Using GPU-compressed textures is becoming increasingly important in computer graphics and gaming, as it allows more resources to be used within the same memory budget and provides better performance by reducing cache misses on the GPU side. The panorama conversion for the project was performed in Khronos TeXture 2.0 using Python ver. 3.8.2 scripts.

After the main work on the project was completed, the virtual tour was integrated into the structure of the museum’s main website. In parallel with the web version, the museum team developed a virtual tour for VR glasses for use in the Kunstkamera exhibition.

The creators envision several possible directions for the project’s future development:

An augmented reality (AR) app enabling real-time comparison, via digital devices, of the museum halls’ current appearance with their appearance 300 years ago.

A “Digital Kunstkamera of the 18th–21st Century” project, which develops the virtual experience into a 4D environment by integrating the time dimension to illustrate the museum’s development and transformation over the past three centuries.

A virtual tour for museum streaming on the Unreal Engine platform.