Abstract

This paper presents Macalla, a practice-based research project investigating how architectural spaces function as co-creative instruments in Ambisonic choral composition. Comprising four original compositions, Macalla employed Nelson’s praxis model, integrating creative practice with critical reflection through iterative cycles of composition, anechoic vocal recording, and site-specific re-recording. The project explored six contrasting architecturally significant spaces including a gaol, churches, and civic offices. Using a stop-motion stem playback methodology, studio-recorded vocals were reintroduced to architectural spaces, revealing emergent sonic properties that challenged compositional intentions and generated new musical possibilities. The resulting Ambisonic works were disseminated through multiple formats including VR/360 video via YouTube, Octophonic concert performance, and immersive headphone experiences to maximize accessibility. Analysis of listener behaviours identified distinct engagement patterns, seekers actively hunting optimal positions and dwellers settling into meditative reception, suggesting spatial compositions contain multiple potential works activated through listener choice. The project contributes empirical evidence of acoustic agency, with documented sonic transformations demonstrating that architectural spaces actively participate in composition rather than passively containing it. This research offers methodological frameworks for site-specific spatial audio creation while advancing understanding of how Ambisonic technology can transform the composer-performer-listener relationship in contemporary musical practice.

1. Introduction

This paper outlines Macalla (Irish for echoes, resonance, memories), a practice-based research project exploring the intersection of spatial audio and choral composition through the sonic and material qualities of historically significant spaces. Meaning “echo” in Irish, Macalla reimagines antiphonal choral traditions while embracing modern interactivity, listener agency, and play. The project investigates the meta-instrument concept by combining studio-recorded choral compositions with site-specific acoustic activation across contrasting architectural environments, drawing from several compositional approaches: composing for space, the influence of materials and architecture, and using spaces as improvisors.

Through systematic exploration of how different material constructions and volumetric configurations transform vocal textures, this research advances understanding of spatial music beyond traditional practices toward immersive, listener-driven experiences where architecture itself becomes the instrument. This exegesis situates the work within theoretical discourse spanning from historical spatial composition to contemporary sonic virtuality, demonstrating how practice-based research generates embodied knowledge about space as an emergent compositional agent.

1.1. From Specialist Venues to Everyday Domestication

Historically, mediated spatial audio experiences were confined to specialist venues, concert halls, or prohibitively expensive VR installations, effectively excluding wider audiences from immersive sonic encounters. This technological gatekeeping meant that spatial audio compositions remained accessible only to those with access to dedicated facilities or high-end equipment.

Recently, we have witnessed a significant shift from these specialized concert venues and expensive VR solutions to accessible domestic environments, enabling spatial audio compositions to reach broader audiences. This transition is accelerated by consumer XR systems and VR headsets like Meta’s Quest series, Apple Vision Pro, and HTC Vive, which deliver immersive audio experiences previously confined to dedicated spaces. The relevance is further amplified by major streaming platforms’ adoption of spatial audio technologies. Apple Music, Tidal, Amazon Music, and YouTube now offer spatial audio options, creating unprecedented opportunities for Ambisonic compositions to reach mass audiences through familiar platforms shifting how audiences encounter spatial music.

1.2. What Is Ambisonics?

Ambisonics is a spatial audio technology that captures and reproduces three-dimensional sound fields around a listener, enabling full-sphere reproduction of acoustic environments (Gerzon 1973; Rumsey 2012). Unlike stereo or surround sound, which uses discrete channels, ambisonics encodes directional information mathematically, allowing sounds to be positioned anywhere in 360-degree space, including above and below the listener (Malham and Myatt 1995; Armstrong and Kearney 2021). This format enables real-time manipulation of the listening perspective; listeners can turn their heads or move within the sound field to focus on different audio sources, effectively “looking around” acoustically so that their spatial orientation directly influences the perceived audio mix (Zotter and Frank 2019).

Macalla inherits both the technical methodology (separation for clarity, contrast through positioning) and the philosophical approach (space as compositional parameter, not mere effect) from these historical precedents while exploring contemporary technological accessibility.

1.3. Practice Based Inquiry

The idea for Macalla developed and evolved through the processes of creation (Skains 2018) and from borrowing concepts from creators in sound art, music, and media production.

The project employs practice-based research following Candy and Edmonds’ (2018) framework where creative work serves as both research process and outcome. This aligns with Nelson’s (2022) praxis model, which integrates “doing” (creative practice) with “knowing” (critical reflection), generating knowledge through iterative cycles of making and reflecting.

Operating within Haseman’s (2006) performative research paradigm, the project generates embodied knowledge through creative practice that conventional academic discourse alone cannot fully articulate. It aligns space as a meta-instrument, drawing on Blesser and Salter’s (2007) conception of acoustic spaces as transformative agents and Barrett’s (2002, 2021) spatial composition frameworks.

The methodology synthesizes studio-recorded vocal materials with site-specific acoustic activation across contrasting architectural environments, following Elina’s (2024) site-oriented curation and Matthews’ (2019) on-site experimentation approaches. This positions space as a collaborative partner rather than a passive container, employing Pink’s (2015) sensory ethnographic approaches acknowledging that spatial audio research demands attention to embodied, multisensory experience. Through Borgdorff’s (2012) “research in the arts” model, the resulting 360-degree choral sound pieces constitute scholarly inquiry itself. This process bridges academic and community knowledge systems (Leavy 2020), advancing understanding through embodied creative investigation rather than conventional academic discourse alone.

1.4. Lines of Inquiry

This research investigates how Ambisonic technology transforms choral composition and listener agency in architectural spaces, examining what new forms of musical meaning emerge when listeners can dynamically navigate spatial audio environments. The study explores how different architectural materials, sandstone, concrete, marble, granite, and mahogany, affect Ambisonic choral compositions when recorded in situ, documenting the specific sonic transformations each material imparts to vocal textures.

Central to this inquiry is understanding what happens to traditional notions of musical authorship when the final mix is “ceded” to listeners through spatial audio navigation, fundamentally altering the composer-performer-audience relationship. The research examines how wordless vocal compositions can exploit Ambisonic technology’s capacity for 360-degree sound placement, using the human voice as a purely sonic material freed from linguistic meaning. Through this investigation, the study identifies compositional strategies that emerge when treating architectural spaces as co-creative instruments rather than inert acoustic shells, establishing new frameworks for understanding the collaborative relationship between sound, space, and listener in contemporary musical practice.

1.5. The Pieces

Macalla comprises four choral pieces1: Ciúnas (Quiet/Stillness), Leanbh (Child), Cá? (Where), and Ná (No). Each offers a wide range of vocal textures and registers to inhabit the spaces while incorporating compositional elements that interact with their acoustic environments. Ciúnas employs extended harmonic clusters to reveal the resonant characteristics of each space, allowing sustained tones to activate and expose architectural acoustics. Leanbh utilizes multiple mini-choirs and counter-melodies to demonstrate spatial separation across 360-degree environments, incorporating solo passages that emphasize architectural scale through contrast between individual voices and massed sonorities. Cá combines controlled aleatory sections with dense chordal passages recorded from varying positions and angles, showcasing how spatial positioning affects timbral perception and sonic coloration. Ná features percussive, staccato elements and tone clusters recorded using speakers suspended from ceilings and positioned at extreme distances from recording equipment, exploring the limits of spatial acoustics through strategic sound source placement.

These compositional strategies investigate two interrelated questions: how architectural acoustics and space function as meta-instruments, and how listeners exercise agency within spatial compositions. Ciúnas employs sustained harmonic clusters as acoustic probes, revealing how marble, sandstone, concrete, and wood each transform identical frequencies into distinct timbral signatures. Ná takes a contrasting approach: its percussive staccato elements investigate how architectural volume and material density affect rhythmic clarity and spatial localization. The difference is strategic, Ciúnas explores resonant properties through sustained tones, while Ná maps spatial boundaries through transient attacks. This deliberate differentiation enables systematic comparison of how architectural materiality shapes sonic perception.

1.6. The Sites

Voices from each piece were recorded in studio, then combined and played back into sites with distinctive acoustic properties and varying volumetric scales. The selection of performance spaces represents a deliberate exploration of contrasting acoustic environments across two churches, two civic offices, a decommissioned power station, and a former gaol. These sites offered discernible volumetric differences, from high vaulted ceilings and circular rotundas to low basement workshops alongside a diverse material palette including marble, poured concrete, mahogany, ceramic tiles, and glass, each contributing unique resonant characteristics to the vocal recordings.

Sites were selected according to three criteria: material diversity to test how different surfaces affect spatial audio, volumetric contrast to understand scale effects, and architectural significance to explore how historical function influences acoustic character.

1.7. The Artefacts

The project was realized as an immersive VR experience where listeners navigate the spatial audio environment through head-tracked Ambisonic rendering, an Octophonic concert installation for live performance spaces, and web-based 360 video with Ambisonic audio. Each format preserves the core principle of listener agency, allowing audiences to explore the acoustic field and participate in the compositional process.

This article follows a practice-based research structure that integrates creative work with scholarly inquiry. Beginning with a literature review positioning the project within spatial audio and choral composition traditions, the methodology section details the innovative site-specific recording process and compositional strategies. The analysis examines how architectural spaces functioned as compositional instruments, while reflections address broader implications for listener agency and musical authorship. The conclusion identifies future directions for both artistic practice and interdisciplinary research in spatial audio.

2. Literature Review

This literature review situates Macalla within intersecting discourses of spatial composition, architectural acoustics, and listener agency. While scholarship addresses spatial music’s historical evolution (Barrett 2002; Harley 1993) and the meta-instrument concept (Blesser and Salter 2007), fewer projects systematically integrate anechoic vocal recording with site-specific acoustic activation across multiple architectural environments. Macalla bridges methodological gaps: the systematic exploration of material-specific acoustic transformations, the integration of stop-motion stem playback as compositional methodology, and the investigation of listener agency in Ambisonic environments. The following review establishes the theoretical foundations and context that Macalla builds upon while identifying the specific contributions this practice-based research.

2.1. Space as Acoustic Effect and Compositional Parameter

The term “spatial music” indicates music in which the location and movement of sound sources functions as a primary compositional parameter and central feature for the listener.

Spatial positioning in choral music traces from fourth-century psalmodic traditions through three forms: direct, responsorial, and antiphonal psalmody (Pierce 1959). The Venetian polychoral tradition descended from these practices, with Willaert’s salmi spezzati (1550) and Gabrieli’s concertato style establishing architectural dialogue as both acoustic necessity and esthetic choice (Solomon 2007). By the seventeenth century, this evolved to massive scales, Benevoli’s 1650 mass employing 150 singers in twelve choirs (Bellini 2021), demonstrating how architectural acoustics became integral to compositional practice.

This spatial awareness evolved through Berlioz’s orchestral spatialization and Wagner’s Bayreuth innovations to Stockhausen’s revolutionary electroacoustic works. Gesang der Jünglinge (1956) and Kontakte (1960) liberated sound movement from architectural constraints through multichannel systems (Maconie 2022), transforming what medieval choirs achieved through cathedral separation into electronic possibilities (Harley 1993). Chowning’s Turenas (1972) advanced this liberation by developing computational tools for calculating loudspeaker energy distributions, creating convincing spatial illusions in fixed media.

Barrett extends this lineage as practitioner-scholar, demonstrating how spatial elements function as primary structural components rather than decoration (Barrett 2002). Her framework connects Willaert’s architectural innovations to Stockhausen’s spherical concepts, while her contemporary methodology incorporates virtual reality and Ambisonic integration, enabling immersive experiences independent of physical spaces (Barrett 2021). This evolution from psalmodic antiphony through electroacoustic experimentation to virtual environments reveals space not as container but as fundamental compositional material, each generation of composers building on predecessors while expanding spatial music’s possibilities through available technologies. Augmenting this, practitioner-scholar Matthews (2019) introduces an alternative methodological approach by bringing unfinished compositional ideas to physical sites, completing works through on-site experimentation and adaptation. This shift positions space as a collaborative partner rather than malleable material, fostering emergent structures. Wishart’s (1994) “Audible Design” extends this discourse by treating space as a transformational domain where sounds undergo metamorphosis through spatial articulation. His practice demonstrates how spatial trajectories become narrative devices, creating what he terms sound transformation journeys that exploit the perceptual ambiguity between source recognition and spatial abstraction.

Macalla builds upon these historical threads by integrating Willaert’s architectural dialogue, Stockhausen’s electroacoustic liberation, Barrett’s Ambisonic practice, and Matthews’ site-responsive methodology, while introducing a stop-motion playback approach that frames architectural spaces as improvisational collaborators rather than predetermined acoustic environments.

2.2. Space and Architecture as Metainstrument

The meta-instrument concept reconceptualizes built environments as active musical participants rather than passive containers. Blesser and Salter’s framework establishes acoustic spaces as agents possessing inherent characteristics that transform and generate musical meaning, documenting architectural acoustics from ancient amphitheatres through modern concert halls (Blesser and Salter 2007). This breadth expands the concept beyond traditional venues, acknowledging that non-musical sites, from caves to industrial buildings, possess unique resonances contributing to sonic experience. However, Grimshaw and Garner challenge these “inherent characteristics” as fixed properties, arguing instead that they emerge through perceptual interaction—the meta-instrument exists not in architecture alone but in the dynamic relationship between sound, space, and perceiver (Grimshaw and Garner 2015). This reconceptualization shifts understanding from architectural spaces as predetermined acoustic instruments to potentials activated through sonic-perceptual engagement, suggesting that the meta-instruments’ characteristics are neither purely physical nor purely perceptual but emerge through their interaction.

This understanding finds practical expression in works that systematically explore recursive acoustic processes. Alvin Lucier’s I Am Sitting in a Room (1969) exemplifies this approach through its recursive recording methodology, where speech gradually transforms into pure resonant frequencies that reveal the room’s unique acoustic signature. Lucier’s process, driven by the recognition that “We have been so concerned with language that we have forgotten how sound flows through space and occupies it” (Lucier 2021, p. 430), demonstrates how architectural spaces can be activated as compositional collaborators. Jacob Kirkegaard’s 4 Rooms extends this methodology to abandoned Chernobyl spaces, where identical recursive processes reveal profoundly different spatial characters, from the comforting resonance of inhabited spaces to the haunting echoes of spaces lost to human habitation.

Contemporary practitioners expand the meta-instrument concept through systematic investigation of architectural space manipulation. Research demonstrates how performance spaces function as responsive instruments through strategic sound source placement and real-time acoustic processing, treating buildings as dynamic systems capable of musical transformation (Bates 2009). An instance of this approach can be found in Elina’s site-oriented curation methodology, which establishes frameworks for developing musical experiences intrinsically linked to their performance locations (Elina 2024). By conceptualizing each venue as a distinct instrument with its own acoustic signature, practitioners must develop compositional strategies tailored to the unique sonic and environmental properties of specific sites, enabling direct performer interaction with architectural acoustics as musical material. The integration of virtual reality and spatial audio technology extends these possibilities beyond physical limitations, as Barrett describes through VR environments that simulate architectural acoustics, enabling composers to design virtual meta-instruments responding to real-time musical performance while maintaining the site-specific engagement principles established through physical practice (Barrett 2021).

Like Lucier’s recursive process, Macalla explores architectural transformation of vocal material yet captures multiple sites’ responses rather than a single room. Where Kirkegaard’s 4 Rooms reveals site character recursively, stop-motion stem playback enables comparative analysis showing materials as emergent collaborators, not fixed properties. Barrett’s virtual meta-instruments demonstrate simulated architectures responding to performance; Macalla inverts this, treating physical architecture as performative through controlled studio input. This operationalizes Grimshaw and Garner’s perceptual interaction while empirically challenging Blesser and Salter’s “inherent characteristics,” documenting material-specific transformations across six contrasting sites.

2.3. Listening as Embodied Spatial Experience

The phenomenological approach recognizes listening as fundamentally embodied experience rooted in corporeal engagement with sonic environments. Bachelard (1964) reveals how acoustic spaces possess psychological and emotional dimensions beyond physical characteristics, a foundation extended by Oliveros’s (2005) Deep Listening, which treats space as expanded awareness emphasizing reciprocal relationships between performer, audience, and environment. This inclusive listening acknowledges that spatial experience is never purely individual as Born (2013) demonstrates, phenomenological encounters are pre-structured by social conventions and institutional contexts that shape how we produce and receive spatial sound.

These social and embodied dimensions converge in LaBelle’s (2010) analysis of how acoustic boundaries establish territories of inclusion and exclusion, while Pallasmaa (2005) reveals that such boundaries engage all senses simultaneously. Acoustic environments generate haptic and kinaesthetic sensations that influence musical meaning, suggesting that spatial listening transcends auditory perception alone. This multi-sensory engagement positions the body itself as sensing apparatus. Voegelin (2010) argues that sound extends from and returns to the body through movement and vibration, creating aural architectures that dissolve boundaries between interior and exterior experience.

Grimshaw and Garner (2015) propose that all spatial sound exists as emergent perception rather than fixed acoustic reality, with listeners becoming co-creators through embodied sonic perception. This framework establishes spatial listening as a dynamic practice where meaning emerges through the interplay of bodies, spaces, cultural contexts, and consciousness itself. When observing listeners engaging with spatial works, Matthews (2019) notes that they move their bodies and heads to establish origins of sounds, distinguishing spatial listening from conventional frontal listening where music ‘hits us like a flat sheet’ (Matthews 2019, p. 297). This bodily engagement transforms the fundamental relationship between audience and artwork, requiring that “in order to access the work, you must be inside it rather than in front of it” (Matthews 2019, p. 297).

The correlation between perception and embodied listening suggests that spatial experience in music cannot be separated from the listener’s corporeal presence and movement within sonic environments. Schmicking (2019) reinforces this, proposing that listeners actively construct meaning through embodied and contextual engagement. This distinction becomes crucial when considering Ambisonic practices, where Elina (2024) proposes the contouring of listening spaces suggests curatorial agency in shaping phenomenological encounters, while Born’s (2013) relational approach emphasizes how these encounters are always already mediated by social and institutional frameworks.

Macalla operationalizes these phenomenological frameworks through Ambisonic technology that affords multiple listening strategies. Where Matthews (2019) describes spatial listening requiring bodily orientation and Schmicking (2019) theorizes embodied meaning-construction, the project’s 360-degree environments enable listeners to construct individual phenomenological encounters through head movement alone. This visceral engagement aligns with Voegelin’s (2010) emphasis on sound returning to the body and Pallasmaa’s (2005) multi-sensory spatial experience. The approach extends Elina’s (2024) curatorial contouring by distributing spatial agency to listeners themselves, who navigate architectural recordings through corporeal engagement. The Ambisonic presentation engages Born’s (2013) relational framework, where identical sonic material generates diverse experiences shaped by each listener’s embodied choices and cultural conventions.

2.4. Virtual Choirs

The practice of creating virtual choirs has gained attention recently, particularly through Eric Whitacre’s works from Lux Aurumque (2010) and Sleep (2011) to Sing Gently (2020) (Cayari 2018). This process involves recording individual voices separately, without performers singing together, then compositing individual lines to form choir sections and complete pieces (Bendall 2020; Mróz et al. 2022). This approach experienced a resurgence during COVID-19 (Bendall 2024; Daffern et al. 2021).

Related but somewhat inverted is Janet Cardiff’s multichannel sound installation The Forty Part Motet (a reworking of Thomas Tallis’s Spem in Alium, 1573). The piece plays back individual voices through forty speakers arranged elliptically in a room. This spatial arrangement offers audience members freedom to move around the space, allowing each listener to experience different perspectives of individual singers within the choir (Cardiff 2010) and discover how each voice contributes to the overall musical composition.

Macalla builds on previous virtual choir work but diverges by combining fragmented vocal recording with architectural re-recording across multiple sites. Rather than creating a single virtual choir like Whitacre or a fixed installation like Cardiff, the project generates site-specific versions where architectural acoustics transform identical vocal materials into distinct sonic experiences.

2.5. Listener Agency

The practice of ceding control of the final mix fundamentally transforms the relationship between composer, listener, and musical work. In spatial audio environments, particularly Ambisonic compositions, listeners become active co-creators rather than passive recipients, dynamically altering the balance and prominence of sonic elements through their physical orientation and attentional choices.

This builds upon established traditions in experimental music, particularly John Cage’s explorations of indeterminacy that makes the listener co-creators of the sonic experience (Hicks and Asplund 2012). Truax (1998, 2012) when considering soundscapes more generally also argues for listener agency proposing that spatial positioning enables listeners to navigate complex sonic environments. So that as listeners exercise choice over their auditory focus they participate in some meaningful way in the compositional process (Truax 2012). Umberto Eco’s theory of the open work (1989) provides grounding for understanding such participatory designs. Eco argues that open works require audience participation to complete them and invite multiple interpretations. More specifically Ambisonic formats can create such open structures where the listener through choice of direction of gaze generates their own version of the mix (Born 2013). And while each piece does have structure it leaves room for exploration and refinement by the listener echoing Eno’s concept of ‘unfinished music’ (Toop 2004).

Macalla offers a form that realizes Eco’s (1989) open work through Ambisonic technology positioning listeners as co-creators. Where Truax (2012) theorizes spatial navigation as meaningful compositional participation and Born (2013) identifies Ambisonic gaze as mix-generating, the project investigates this agency across six architectural environments. By ceding final mix control and requiring listeners to complete works through spatial navigation, Macalla transforms theoretical possibility into documented practice. Rather than prescribing singular phenomenological paths, the project demonstrates how spatial composition affords co-creative listening where meaning emerges through voluntary bodily engagement.

The frameworks examined illuminate three dimensions of spatial sound: space as compositional parameter versus acoustic effect; space as meta-instrument rather than passive container; and embodied experience engaging perceptual-phenomenological listening. These converge on listener agency in the case of this project how Ambisonic technology enables audiences to navigate spatial environments and complete their own mix, transforming passive recipients into active participants.

These approaches provide both guidance and necessary limitations for this research, offering guardrails that focus inquiry from initial compositional processes through to final artefacts, ensuring practice-based exploration remains grounded in established theoretical discourse while generating new embodied knowledge about spatial-sonic relationships.

3. Methods

3.1. Process and Realization

The following section examines the creative processes involved in developing the experience, from initial composition through recording, spatialization, site-specific playback, and improvisation, to final post-production and output

3.1.1. Choosing and Selecting Sites

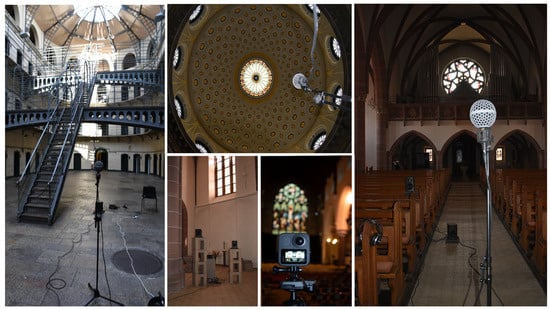

Six sites were selected to provide a wide range of materials and volumetric spaces for recording and playback of the compositions. Each location was chosen for the inherent acoustic differences created by their primary construction materials and architectural forms (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sites and Materials, examples of Church, Gaol, Power Station and Civic office—showing the volumes and materials of the spaces.

St. Boniface Church established a baseline for choral recording, representing the traditional context most commonly associated with choral performance, while offering high vaulted ceilings and the rich resonance of red sandstone construction. In direct contrast, eWerk, a decommissioned power station, provided low ceilings and poured concrete surfaces that produced shallower tones and shorter reverberations and greater separation demonstrates identical musical material recorded in both environments, illustrating their contrasting acoustic signatures and resulting interpretive meanings2.

The civic office features a large marble rotunda whose curved geometry and reflective materials dramatically transformed vocal timbres, morphing recognizable vocal sounds into textures resembling brass sections. The former gaol presented expansive granite spaces complemented by significant iron fixtures and a glass ceiling, creating a distinctive acoustic environment that further diversified the project’s sonic palette.

The Guildhall, constructed primarily of mahogany and California redwood, produced shorter reverberant times compared to the ecclesiastical venues. However, the substantial hardwood construction generated deeper, richer tones throughout the compositions. Finally, the second church, formerly part of a Magdalene Laundry, offered a large recording space featuring ceramic tiles and lighter pine rather than sandstone. While the space’s size created substantial reverberant times, the materials produced more brittle tones and notably diminished the lower register frequencies in larger choral sections. Table 1 provides an overview of six sites noting main use and materials of note.

Table 1.

Sites and Materials Overview: name of site, main function of building location and Principal materials.

3.1.2. Compositional Considerations

The Macalla project comprises four compositions: Ciúnas (Quiet–Stillness), Leanbh (Child), Cá? (Where), and Ná (No).

Several elements guided the compositional process: sound placement, spatial resonances, material properties of each recording space, and the diverse principal uses of the selected buildings. Since the final format would be ambisonics offering full 360-degree sound placement each composition needed varied elements to showcase spatial characteristics effectively.

3.1.3. Only Voice?

Macalla employs voice exclusively as its sonic material, recognizing it as the most immediately accessible and universally comprehensible sound source (Ihde 2012). Unlike instruments requiring technical knowledge for appreciation, voice carries what Cavarero (2005) identifies as presence without cultural mediation, offering material immediacy that bridges listener and singer through visceral, embodied connection transcending linguistic content (Connor 2000; Vallee 2019). This accessibility enables architectural acoustics to emerge clearly, as listeners engage with familiar vocal timbres rather than unfamiliar instrumental sonorities. Voice thus functions as an optimal medium for exposing spatial characteristics while maintaining emotional resonance regardless of musical training or cultural background.

Textural contrasts guided compositional decisions. Dense chordal passages with wide pitch ranges expose resonance properties and reverberation times, while percussive staccato elements reveal alternative acoustic characteristics. Each piece incorporates multiple mini-choirs and counter-melodic lines demonstrating voice group separation across 360-degree audio placement, with solo passages providing dynamic contrast and emphasizing architectural scale.

The compositions employ non-lexical vocables rather than recognizable words, transforming voices into sonic material rather than semantic communication. This approach enables wordless passages to communicate universally without linguistic barriers, as intelligible text becomes secondary to how voices blend with architectural resonance. Sustained tones and breath sounds merge with environmental acoustics, particularly effective in spatial audio where multiple simultaneous choirs can fragment words spatially, rendering them incomprehensible.

3.2. Recruitment, Recording Process and Vocal Material Construction

3.2.1. Ensemble Configuration and Musical Direction

Collaborative engagement was facilitated through an experienced choral conductor who proved invaluable in both recruitment and studio guidance. Seven singers (four female, three male) were recruited to cover the required vocal range from D2 to C5, with an experienced choral conductor facilitating recruitment and providing musical direction. This mixed-gender ensemble was strategically configured to provide timbral flexibility, with overlapping ranges allowing multiple singers to cover shared pitches. For harmonic passages where both male and female voices could execute identical pitches, recordings were captured from singers of different genders to create layered textures and timbral reinforcement. The musical director maintained oversight of intonation and timing consistency, whilst the composer focused on recording quality and systematic completion of the note inventory. This division of responsibilities ensured both technical precision and musical coherence throughout the fragmented recording process.

3.2.2. Articulation and Expression Sampling

Each harmonic tone was recorded as individual two to four second samples with multiple articulatory variations. Primary vowel sounds (AH, OH) formed the foundational palette, captured across expressions ranging from breathy and soft to powerful and focused, while consonant sounds (NA, DA) offered more percussive textures. Melodic passages and counterpoint lines were similarly recorded in short sections with multiple takes to capture variation in tone and delivery. This systematic sampling approach created a comprehensive library of vocal timbres selectively deployable during spatial composition. The fragmented recording enabled construction of melodic lines technically challenging or impossible in live performance, expanding compositional possibilities beyond conventional choral writing constraints.

3.2.3. Recording Protocols and Performer Preparation

Individual singers were recorded in an anechoic studio environment using dual Neumann microphones (T103 facing, T102 overhead) to provide tonal options whilst avoiding microphone pops and breath noise. Sessions were recorded at 48 kHz into both Adobe Audition and Reaper DAWs for redundancy.

Since individual harmonic notes were utilized across multiple compositions, most performers received only individual parts alongside click metronome or MIDI guide tracks for temporal precision. However, singers performing melodic lead lines received project overviews including composition titles and intended playback locations. This isolation method ensured maximum spatial flexibility during post-production, allowing individual vocal elements to be positioned within virtual acoustic environments impossible to achieve through traditional ensemble recording approaches.

3.2.4. Performance Challenges and Insights

The recording process revealed significant insights about choral practice and spatial audio production. Whilst all recruited singers were experienced choral performers comfortable with music reading and precision singing, two notable challenges emerged. First, singers accustomed to ensemble performance found singing isolated notes without harmonic context disorienting, requiring adjustment periods to perform effectively without the familiar support of other voices. Second, the anechoic recording environment proved disconcerting for singers whose native performance contexts included the natural reverberation of concert halls and churches. The absence of acoustic feedback that typically guides choral performance required conscious adaptation from singers more familiar with acoustically responsive environments.

3.3. Synchronization

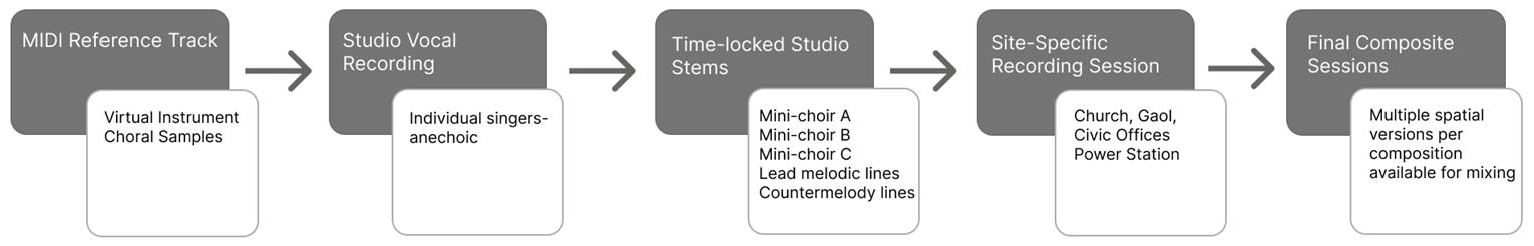

The synchronization workflow (see Figure 2) operated through a systematic five-stage process designed to maintain temporal precision across multiple recording environments. Initially, isolated studio vocal recordings were synchronized to MIDI reference tracks, establishing the foundational timing framework.

Figure 2.

Iterative Process Visualization.

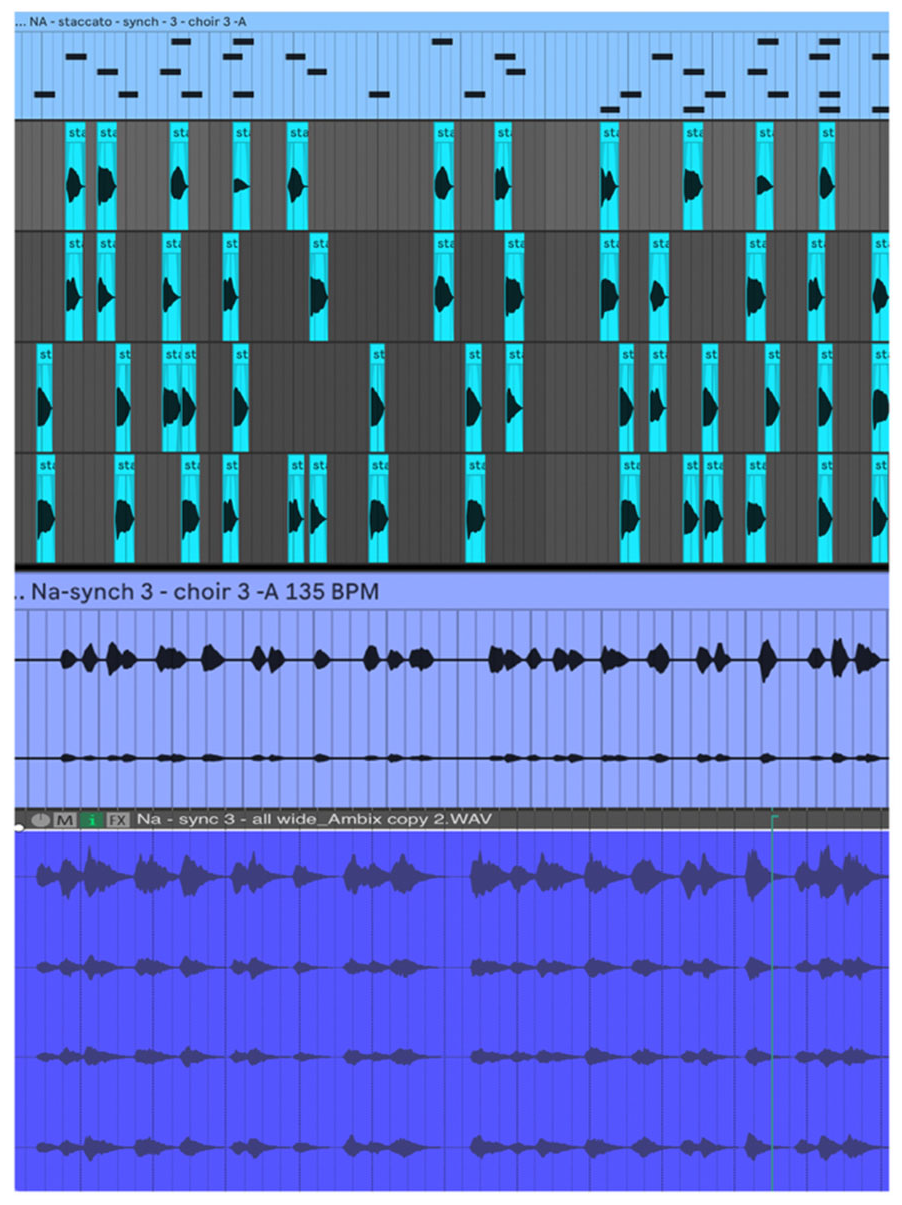

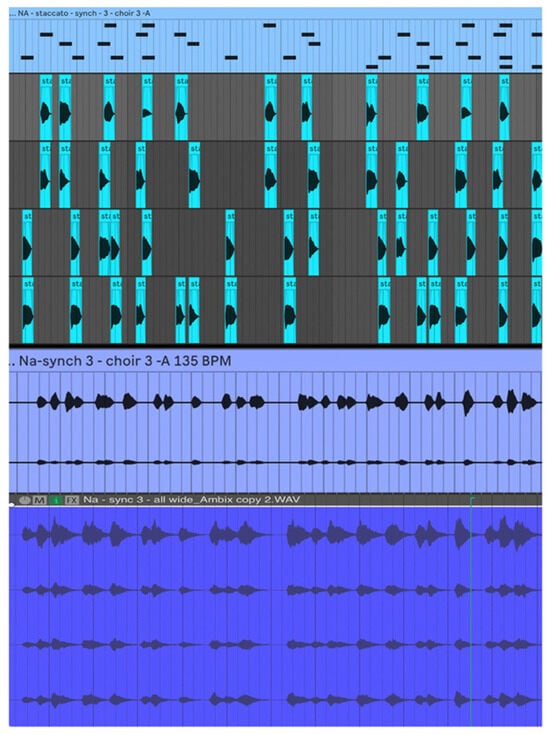

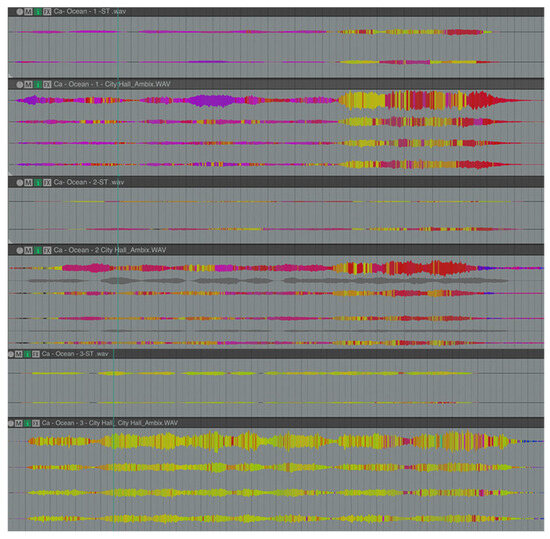

These studio recordings were then organized into stems representing discrete musical elements: harmonic chord groupings (designated as mini-choirs A, B, and C) and individual melodic components (lead lines and counter-melodies). Each stem ranged from 5–30 s in duration, providing manageable segments for subsequent processing phases. Figure 3 below shows the steps in assembling one of the six mini choirs that is part of the end of Ná3. Each mini choired placed at different place and angles throughout the space.

Figure 3.

Example of the process of synch initial single notes to MID to form a composite stem to final Ambisonic site recording. This example is form Ná shows one of six mini choirs’ assemblage.

Following completion of site-specific recordings these captures were synchronized to the pre-existing studio stems, creating composite sessions containing multiple spatial versions of each composition. This hierarchical synchronization approach enabled the integration of isolated vocal materials with location-specific acoustic signatures while maintaining temporal alignment throughout the production process. Leading to final composite sessions comprising multiple spatial versions per composition available for mixing. The process is outlined in Table 2, which shows the dependencies and porpose fo each stage.

Table 2.

Synchronization Workflow Table.

3.4. Site-Specific Playback and Improvisation

While each site offered different sonic possibilities, a similar recording process using studio stems was employed across all locations.

A 360-degree video camera captured baseline footage at each site, with additional recordings made halfway through and after equipment removal to provide varying ambient lighting conditions from the 4–7 h sessions.

Stop-Motion Playback Process

The Ambisonic microphone was placed at 178 cm height consistently across all recordings. The playback process resembled stop-motion animation: stems lasting 5–40 s were played from set positions, speakers repositioned, and additional stems played from new positions. Each piece contained 12–25 stems, with each recorded 3–4 times to capture varying background noise levels and ensure uninterrupted takes.

Initial recordings followed pre-planned arrangements, then, additional elements enhanced each space’s unique characteristics: Tone clusters from Cá? played at floor level angled toward marble rotunda, speakers hoisted from ceilings allowing chord progressions from positions like six metres left of an altar, with individual notes recorded from multiple positions.

Through this process, each space became an improvisational partner in the arrangement and sonic character, generating unique recordings impossible to achieve in live performance and offering tonal possibilities only discoverable through spatial experimentation. Figure 4 offers examples of audio and video capture in the sites. In the studio, site recordings were synchronized with original stem mixes, with selections based on minimal environmental noise or positions that enhanced the final mix.

Figure 4.

Site Recording.

3.5. Sharing and Performing the Work

The four choral pieces utilize higher-order ambisonics containing comprehensive spatial information decodable to first-order ambisonics or Octophonic arrays. However, higher-order playback requires specialized equipment including multi-speaker arrays or head-tracking systems, limiting broader accessibility.

Cinematic VR with ambisonics (ambiX) was selected as the primary platform to maximize reach while maintaining spatial integrity. This format enables direct VR headset deployment and YouTube4 sharing, which natively supports 360-degree video with Ambisonic audio. Though prioritizing sound, the visual component provides environmental grounding and intuitive navigation across all directions.

The platform accommodates diverse interactions: VR headset immersion, browser-based exploration with mouse/touch controls, and mobile motion tracking for directional focus. Live Octophonic concerts offer communal listening experiences, demonstrating adaptability across personal and shared contexts while preserving spatial characteristics.

4. Discussion/Reflections

4.1. Playable Spaces

Macalla through composition, process and final realizations validate, complicate and augment nuance to existing spatial music theories. Barrett’s (2002) proposals of spatial elements proved accurate with planning and structure in studio components and preparation for site recordings, yet this project and outcomes align more closely with Matthews (2019) collaborative partner model.

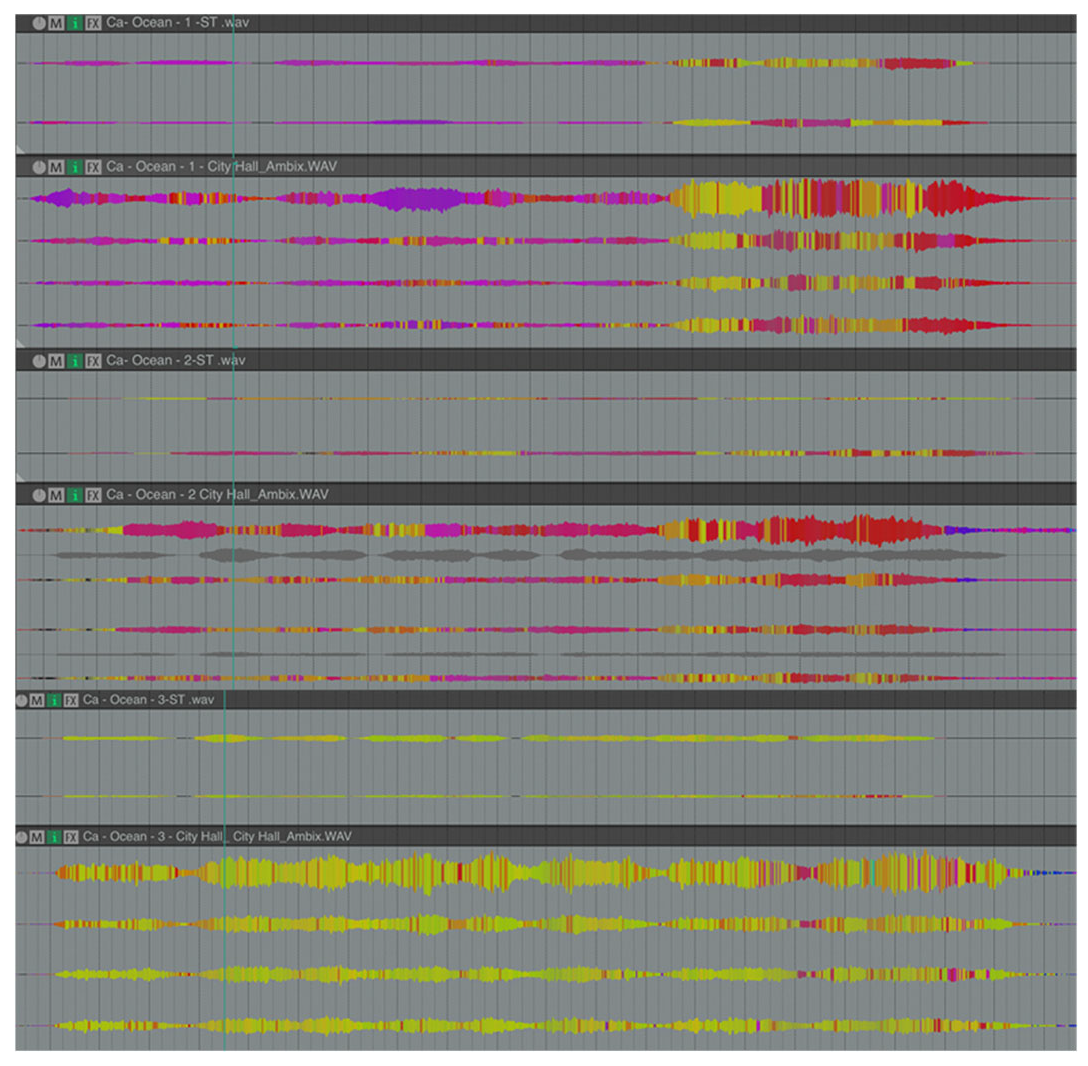

Particularly notable is the aleatoric opening of Cá. In the civic offices (City Hall) the combination of marble flooring, walls, and dome-shaped ceiling transformed the dry studio tones, extending their duration and creating new brass like textures5. The interacting with the space produced audible chimeras, suggested tones absent from the original studio recordings, transforming recognizable vocal sounds into something more ambiguous and otherworldly. Figure 5, through spectrogram visualizations shows how dry studio recordings were transformed by the spaces.

Figure 5.

Comparison of spectrogram visualization showing the spatialization, reverberation and tonal/frequency changes for Cá—the anechoic recording against the recording made in the City Hall.

This extends Blesser and Salter’s (2007) meta-instrument concept beyond their original formulation. While they position spaces as playable instruments with inherent characteristics, Macalla provides tangible, even visceral evidence of this concept by demonstrating how identical studio recordings transform completely when reintroduced to different architectural spaces. This augments Elina’s (2024) proposition as each venue as a distinct instruments from not only compositional strategies but in situ negotiation and improvisation with the space.

During VR listening events, participants exhibited distinct behaviours and tolerances, choosing to stand, sit on swivel chairs, or recline on beanbags. After initial environmental novelty subsided, engagement focused on the musical material itself. Since navigation required only head movement without pointing or clicking, exploration remained intuitive and embodied.

4.2. Listener Agency, and Play

Grimshaw and Garner’s (2015) predicted that listeners would construct personal spatial experiences, but through listening session is was revealed how listeners create different ontologies of the same work. Two primary listening behaviours emerged. Seekers searched for optimal positions, tracking soloists and rotating until finding preferred vantage points, particularly during the melodically familiar pieces Leanbh and Ciúnas. Dwellers settled on single perspectives and remained relatively stationary, moving minimally except when triggered by specific sonic events like a soloist appearing on a balcony or percussive plosives from overhead gangways. A smaller group reclined on beanbags for second listenings, letting the sound wash over them, especially during Cá, whose mix derived from the civic office’s spherical marble dome.

Repeat listeners engaged most actively, spending 12–15 min exploring all four pieces. Seekers particularly sought alternative routes through pieces on subsequent listenings, exhibiting playful exploration. This playfulness extended to post-listening discussions where participants shared experiences and advised others on optimal routes. Both approaches produced coherent but different musical experiences, suggesting spatial compositions contain multiple potential works activated through listener choice.

The emergence of seekers and dwellers as distinct listening behaviours reveals fundamentally different approaches to spatial music reception. Seekers’ navigation aligns with Matthews’ (2019) observation on who move their bodies to orient them to sound and gives ground observation to what Schmicking (2019) describes as actively constructing meaning through embodied and contextual engagement. Dwellers approached the work through less movement exhibiting a deep listening practice by treating space as expanded awareness Oliveros’s (2005) requiring patient receptivity, options to Born’s (2013) obversions regarding pre-structured listening. Some participants brought concert hall conventions of stillness and focused attention, while others imported interactive media navigation habits, actively sharing discoveries and proposing alternative routes through the pieces. The post-listening exchanges, where seekers advise on optimal positions and dwellers describe temporal revelations, suggest that spatial music reception is not only individually embodied but can also be socially negotiated.

4.3. Stop-Motion Stem Playback

The stop-motion stem playback methodology developed for Macalla contributes to spatial audio composition and recording practice. Playing individual vocal stems from specific positions, then repositioning speakers while maintaining fixed Ambisonic microphone placement, enabled systematic exploration of architectural acoustics impossible through traditional ensemble recording. This approach allowed compositional ideas to emerge on-site, offering complete coverage of all vocal lines with optimal positioning selected from multiple locations.

The methodology also influenced compositional parameters in real-time. On-site experimentation revealed how limiting choir registers affected spatial perception. For instance, restricting accompaniment to voices below D3 created dramatically different acoustic interactions with architectural spaces than full-range choruses. These discoveries enabled immediate compositional decisions about whether to support soloists with complete choral textures or to selectively employ specific vocal ranges based on how each space responded to different frequencies. This responsive approach transformed the recording process into an active dialogue between compositional intention and the spaces. Post-production flexibility proved invaluable with final spatial compositions emerging through iterative experimentation rather than predetermined arrangements.

While recording required two hours or more to capture 3–4 min of musical material per piece, this time investment is comparable to multiple takes needed for live ensemble recording. Crucially, using identical studio material throughout enabled direct comparison between spaces without performance variability or equipment differences affecting results.

5. Conclusions

Macalla demonstrates that architectural spaces function not as passive acoustic containers but as active compositional collaborators possessing what this research terms acoustic agency. The project’s systematic exploration of six contrasting sites revealed that materials like marble do not simply add reverberation but fundamentally recompose harmonic structures through selective frequency amplification, creating audible chimeras, tones absent from original recordings. The stop-motion stem playback methodology proved essential for uncovering these emergent properties, enabling discoveries impossible through traditional ensemble recording.

The research documented how Ambisonic technology can afford transformations in musical authorship and reception: listeners do not decode predetermined meaning but actively construct musical form through spatial navigation, with distinct behavioural patterns (seekers versus dwellers) revealing that spatial compositions readily afford multiple valid interpretations rather than a singular intended experiences. The concept of navigational authorship emerges as listeners do not simply interpret but actively construct musical form through movement, suggesting new ways for understanding distributed creativity in interactive media.

5.1. Implications and Contributions

This work advances spatial music practice by providing reproducible methodologies for site-specific composition that embrace rather than control architectural agency. The multi-platform distribution strategy demonstrates how spatial audio can reach diverse audiences without compromising artistic integrity, each format, VR, web, concert, creating distinct but equally valid works. For music education, Macalla offers new pedagogical models where students learn composition through spatial exploration rather than notation alone. Methodologically, the studio-to-site-to-studio workflow established a replicable framework for spatial composition research, demonstrating how practice-based inquiry generates embodied knowledge unavailable through theoretical analysis alone.

The stop-motion methodology at the heart of this workflow offers further pedagogical and practical advantages. By slowing the creative process into discrete stages (studio recording, site activation, comparative analysis), it enables reflection on how architectural materiality transforms sonic materials. This deliberate pacing suits teaching contexts where understanding emerges through systematic documentation. The methodology scales across resource levels: individual researchers or small ensembles can implement it using consumer-grade ambisonic microphones and portable speakers in accessible local sites. This scalability and lower equipment costs make the approach particularly suitable for graduate research, independent composers, and community-engaged practice exploring local sonic heritage.

5.2. Future Work

Future investigations could explore how semantic content (text-based compositions) functions within navigable spatial environments, examining whether linguistic meaning anchors or liberates spatial interpretation. Cross-cultural studies comparing spatial listening behaviours across different musical traditions would illuminate whether seeker/dweller patterns reflect Western listening habits or universal spatial engagement modes.

As virtual production environments become increasingly sophisticated, research could investigate whether purely digital spaces can achieve the acoustic agency demonstrated by physical architecture, or whether materiality remains essential to spatial composition’s potential. Reconstructed historical spaces such as ancient Greek amphitheatres or early Christian churches, whose original acoustics can no longer be directly experienced, offer compelling test cases. Whether impulse responses prove sufficient to recreate authentic acoustic agency, or whether physical materiality remains irreducible, constitutes an empirical question. Such investigations would enable comparative studies across historical periods, revealing how architectural traditions shaped musical practice, social interactions, and the lived experience of inhabiting built environments.

The stop-motion methodology could be adapted for real-time performance, using motion-tracking systems to allow performers and/or listeners to play architectural spaces through movement. The technique offers a useful model for other composers. Smaller projects might use fewer stem positions while maintaining the core principle of spatial exploration. The methodology particularly suits site-specific works where architectural investigation is paramount, especially for projects exploring audio history and sonic cultural heritage.

Ultimately, Macalla argues that the relationship between music and architecture in spatial audio composition is neither subordinate (music in architecture) nor instrumental (architecture for music) but genuinely collaborative: spaces possess agency that composers can engage dialogically, creating works that emerge from the conversation between compositional intention and architectural response

Funding

This project was supported for materials and equipment rental by Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences DCU Research Funding-Creative Output Scheme.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in YouTube Macalla at https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLgkFVu7smHMpoMKG0S9AJAm7KAAKtuYMq.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Notes

| 1 | Clips are available at a YouTube playlist in 360 Video and Ambisonics. Detailed timing references for specific examples will be offered later in the text. https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLgkFVu7smHMpoMKG0S9AJAm7KAAKtuYMq&si=n6Lejwsq3gdfACjO. |

| 2 | An example of this direct comparison from eWerk (Power Station) concrete and low ceiling to vaulted ceiling of the St. Boniface (Church) can be found in Ciúnas 1:39–3:30. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SAIPQXA3w5o&list=PLgkFVu7smHMpoMKG0S9AJAm7KAAKtuYMq&index=2. |

| 3 | The final version composite version of all six choirs singing plosive ‘Da’ into the space can be in Ná. 1:53–3:02 at https://youtu.be/iiTsk5RNDHE?si=Lgclxi9XtA2CqH3d&t=181 |

| 4 | A Playlist of three full pieces is available at: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLgkFVu7smHMpoMKG0S9AJAm7KAAKtuYMq&si=JIYb1xY5ZARDuu59. |

| 5 | Good examples of this are both the opening of Cá 0:10–1:12 and the ending 3:15–4:20 at https://youtu.be/PZUeJQ9L3PU?si=CpPWkSa_vEFiwQZ5. |

References

- Armstrong, Cal, and Gavin Kearney. 2021. Ambisonics Understood. In 3D Audio. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bachelard, Gaston. 1964. The Poetics of Space. Translated by M. Jolas. New York: The Orion Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, Natasha. 2002. Spatio-Musical Composition Strategies. Organised Sound 7: 313–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, Natasha. 2021. Spatial music composition. In 3D Audio. London: Routledge, pp. 175–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, E. 2009. The Composition and Performance of Spatial Music. Ph.D. dissertation, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Bellini, Federico. 2021. Architecture for Music: Sonorous Spaces in Sacred Buildings in Renaissance and Baroque Rome. In Creating Place in Early Modern European Architecture. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bendall, Cole. 2020. Defining the Virtual Choir. The Choral Journal 61: 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Bendall, Cole. 2024. Virtual Choirs and Issues of Community Choral Practice. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blesser, Barry, and Linda-Ruth Salter. 2007. Spaces Speak, Are You Listening. Experiencing Aural Architecture. Cambridge: MIT Press, p. 232. [Google Scholar]

- Borgdorff, Henk. 2012. The Conflict of the Faculties: Perspectives on Artistic Research and Academia. Leiden: Leiden University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Born, Georgina. 2013. Music, Sound and Space: Transformations of Public and Private Experience. Cambridge: Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Candy, Linda, and Ernest Edmonds. 2018. Practice-Based Research in the Creative Arts: Foundations and Futures from the Front Line. Leonardo 51: 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardiff, Janet. 2010. The Forty Part Motet. Salisbury: Sound Installation. [Google Scholar]

- Cavarero, Adriana. 2005. For More than One Voice: Toward a Philosophy of Vocal Expression. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cayari, Christopher. 2018. Connecting Music Education and Virtual Performance Practices from YouTube. Music Education Research 20: 360–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, Steven. 2000. Dumbstruck—A Cultural History of Ventriloquism. Oxford: OUP Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Daffern, Helena, Kelly Balmer, and Jude Brereton. 2021. Singing together, yet apart: The experience of UK choir members and facilitators during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 624474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eco, Umberto. 1989. The Open Work. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elina, Sasha. 2024. Site-Oriented Music Curation. Contouring the Listening Spaces. In The Routledge Companion to the Sound of Space. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gerzon, Michael A. 1973. Periphony: With-Height Sound Reproduction. Journal of the Audio Engineering Society 21: 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw, Mark, and Tom Alexander Garner. 2015. Sonic Virtuality: Sound as Emergent Perception. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, Maria. 1993. From point to sphere: Spatial organization of sound in contemporary Music (after 1950). Canadian University Music Review 13: 123–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseman, Brad. 2006. A Manifesto for Performative Research. Media International Australia 118: 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, Michael, and Christian Asplund. 2012. Christian Wolff. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ihde, Don. 2012. Listening and Voice: Phenomenologies of Sound. New York: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- LaBelle, Brandan. 2010. Acoustic Territories: Sound Culture and Everyday Life. New York and London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Leavy, Patricia. 2020. Method Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice. New York: Guilford publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lucier, Alvin. 2021. Reflections: Interviews, Scores, Writings, Enl. new ed. Köln: MusikTexte. Available online: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1971712334781052821 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Maconie, R. 2022. Understanding Stockhausen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Malham, David G., and Anthony Myatt. 1995. 3-D Sound Spatialization Using Ambisonic Techniques. Computer Music Journal 19: 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, Emma-Kate. 2019. Activating Audiences: How Spatial Music Can Help Us to Listen. Organised Sound 24: 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mróz, Bartłomiej, Piotr Odya, and Bożena Kostek. 2022. Creating a Remote Choir Performance Recording Based on an Ambisonic Approach. Applied Sciences 12: 3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Robin. 2022. Practice as Research in the Arts (and Beyond). Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveros, Pauline. 2005. Deep Listening: A Composer’s Sound Practice. Lincoln: iUniverse. [Google Scholar]

- Pallasmaa, Juhani. 2005. The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, James Smith. 1959. Visual and Auditory Space in Baroque Rome. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 18: 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pink, Sarah. 2015. Doing Sensory Ethnography. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Rumsey, Francis. 2012. Spatial Audio. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schmicking, Daneil A. 2019. A Phenomenological Perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of Sound and Imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 1, p. 79. [Google Scholar]

- Skains, R. Lyle. 2018. Creative Practice as Research: Discourse on Methodology. Media Practice and Education 19: 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, Jason Wyatt. 2007. Spatialization in Music: The Analysis and Interpretation of Spatial Gestures. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Toop, David. 2004. Haunted Weather Music, Silence and Memory. London: Serpent’s Tail. [Google Scholar]

- Truax, Barry. 1998. Composition and Diffusion: Space in Sound in Space. Organised Sound 3: 144–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truax, Barry. 2012. Sound, Listening and Place: The Aesthetic Dilemma. Organised Sound 17: 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallee, Mickey. 2019. Sounding Voice. In Sounding Bodies Sounding Worlds: An Exploration of Embodiments in Sound. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Voegelin, Salomé. 2010. Listening to Noise and Silence. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 1–256. [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, Trevor. 1994. Audible Design. York: Orpheus the Pantomime York. [Google Scholar]

- Zotter, Franz, and Matthias Frank. 2019. Ambisonics: A Practical 3D Audio Theory for Recording, Studio Production, Sound Reinforcement, and Virtual Reality. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).