Human Skeletons in Motion, Defleshed Animals in Action and Transformation of Species in Northern Tradition Rock Art

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Essential Dating of Iconography and the Rock Art Practice

1.2. The Need to Decolonise Modern Premises in Archaeological Research

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

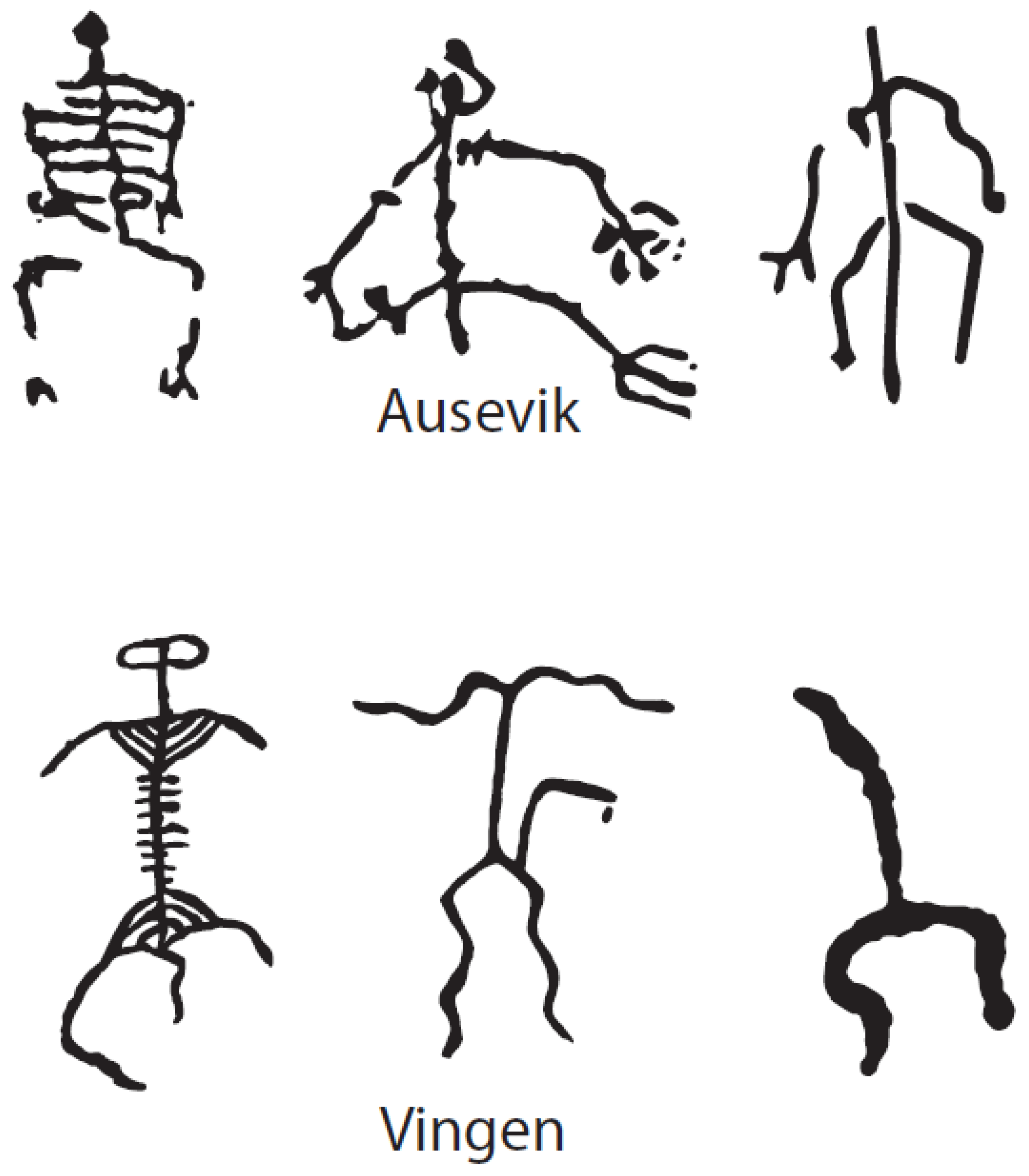

3.1. Human Skeletons in Motion

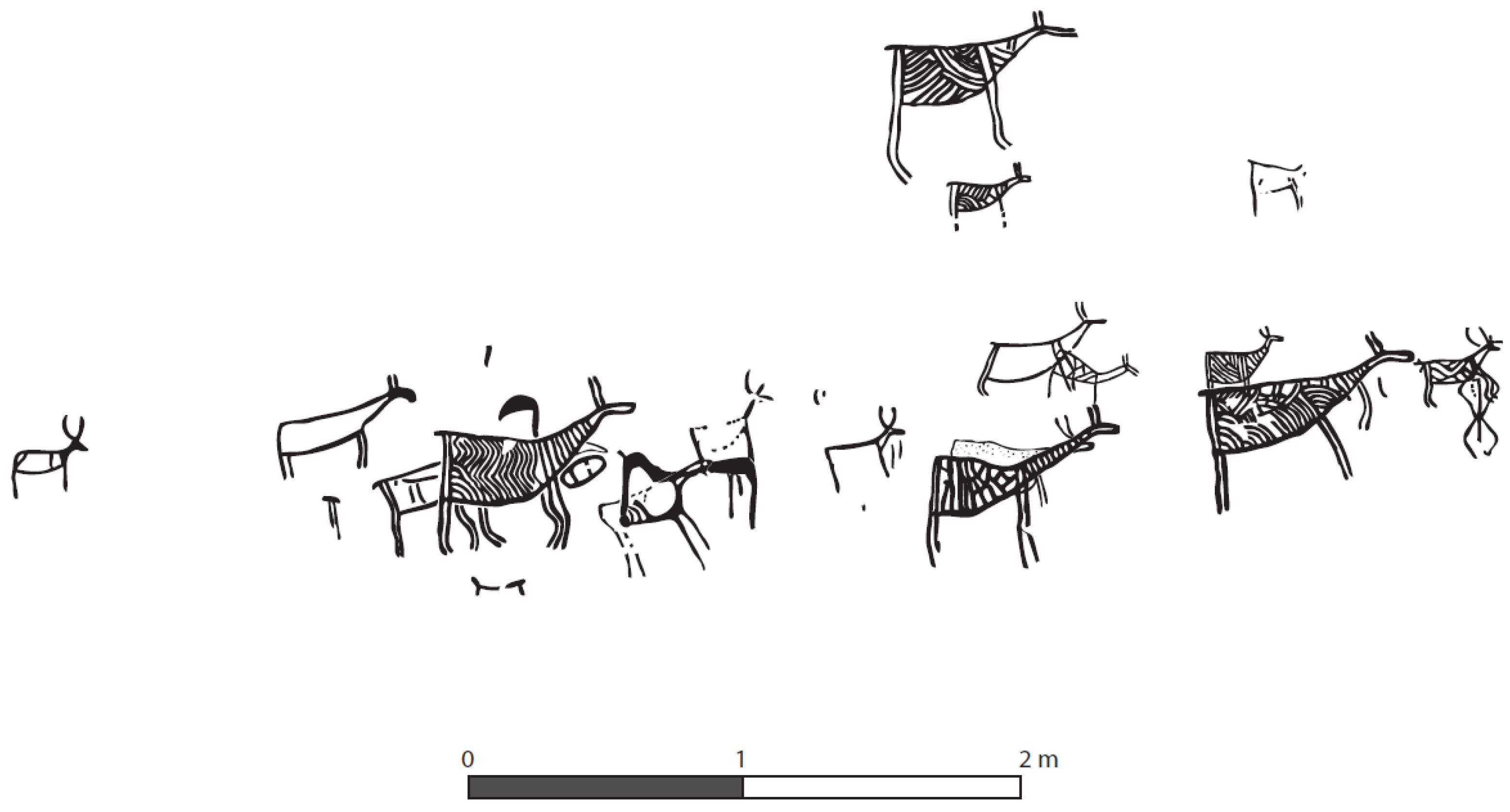

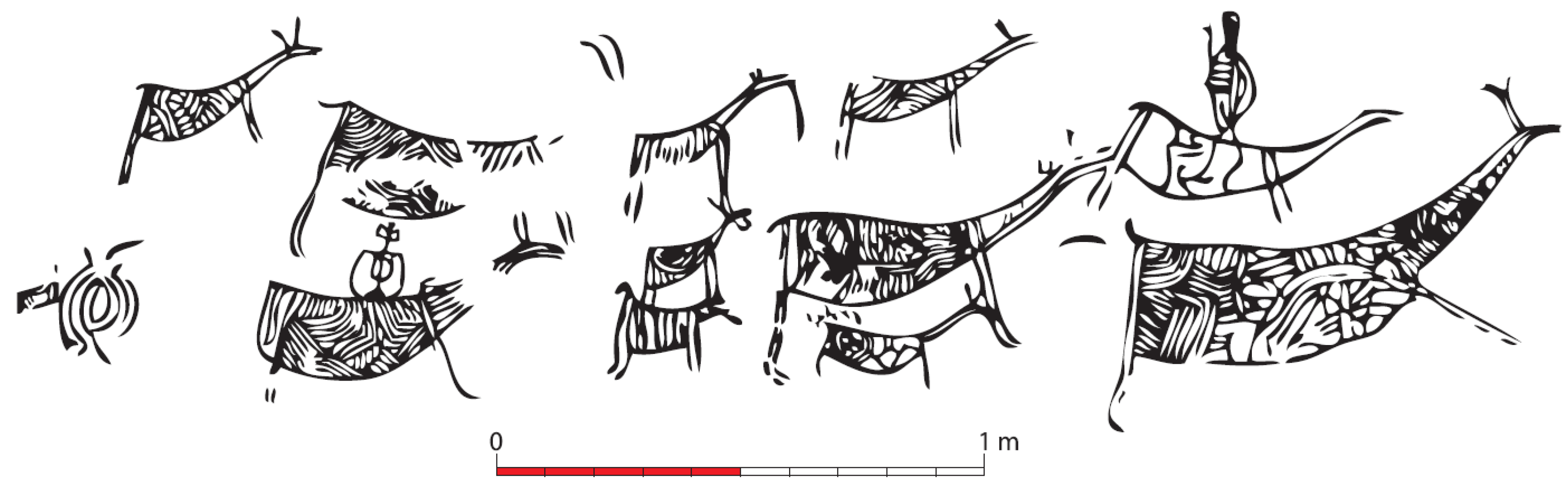

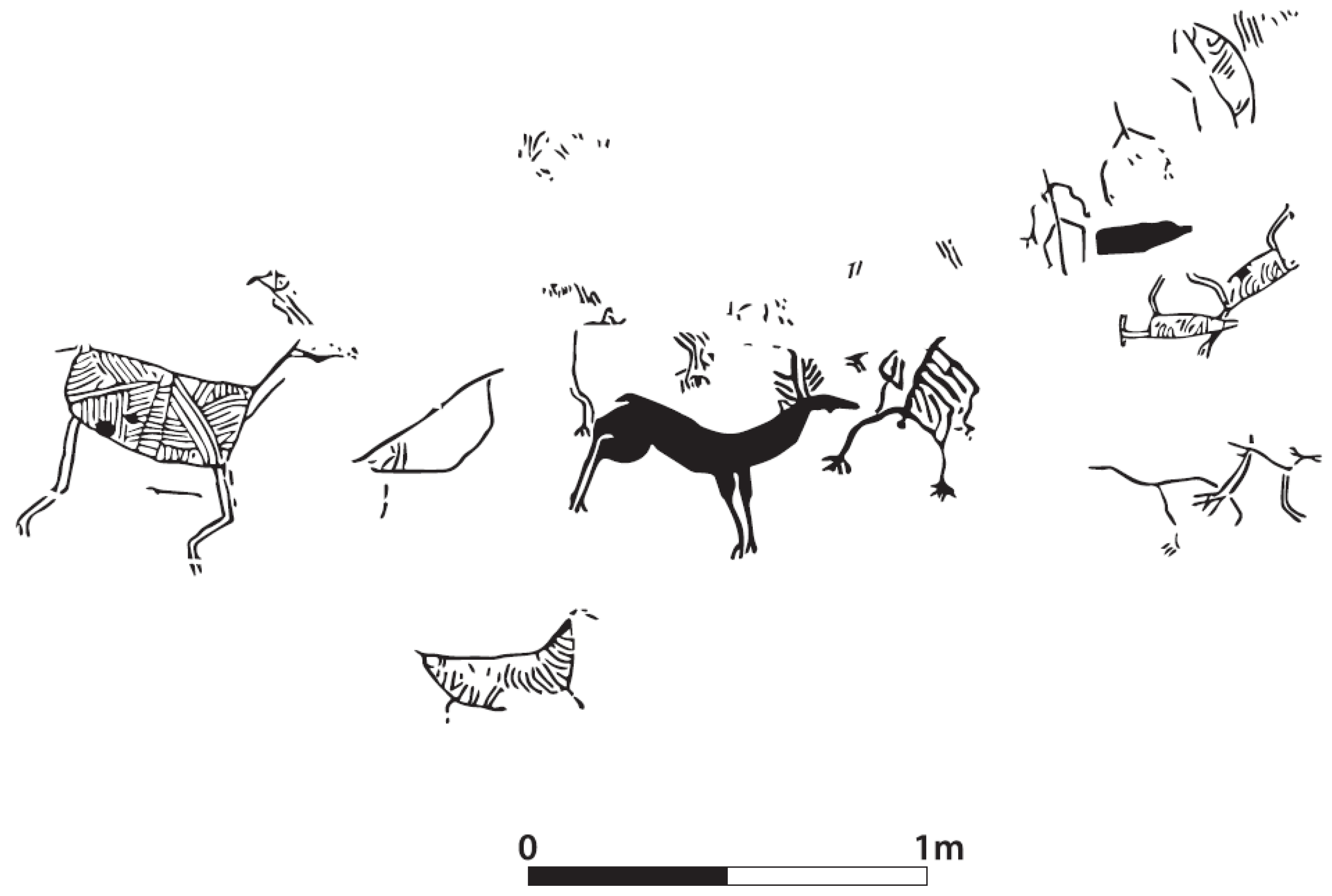

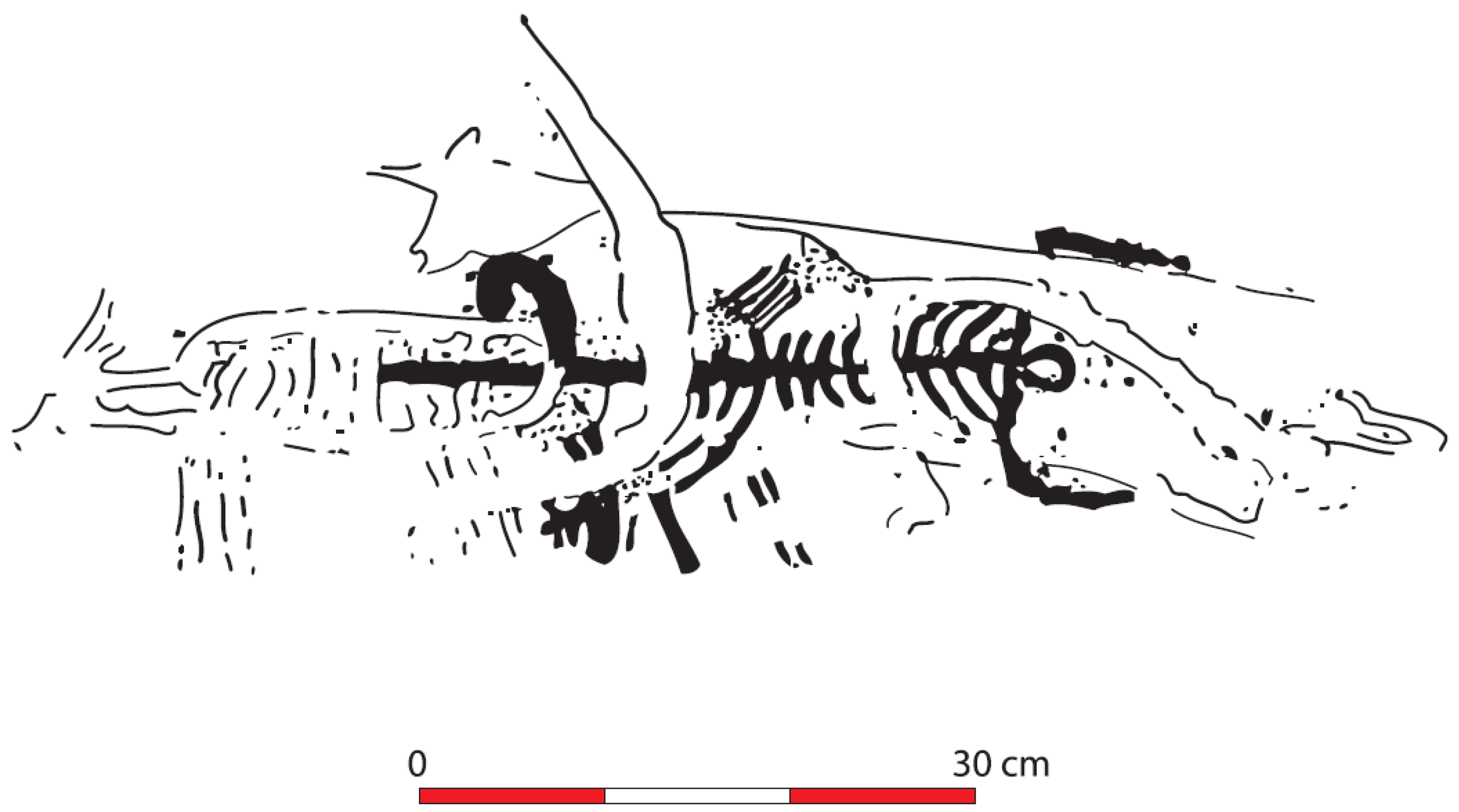

3.2. Defleshed Animals in Action

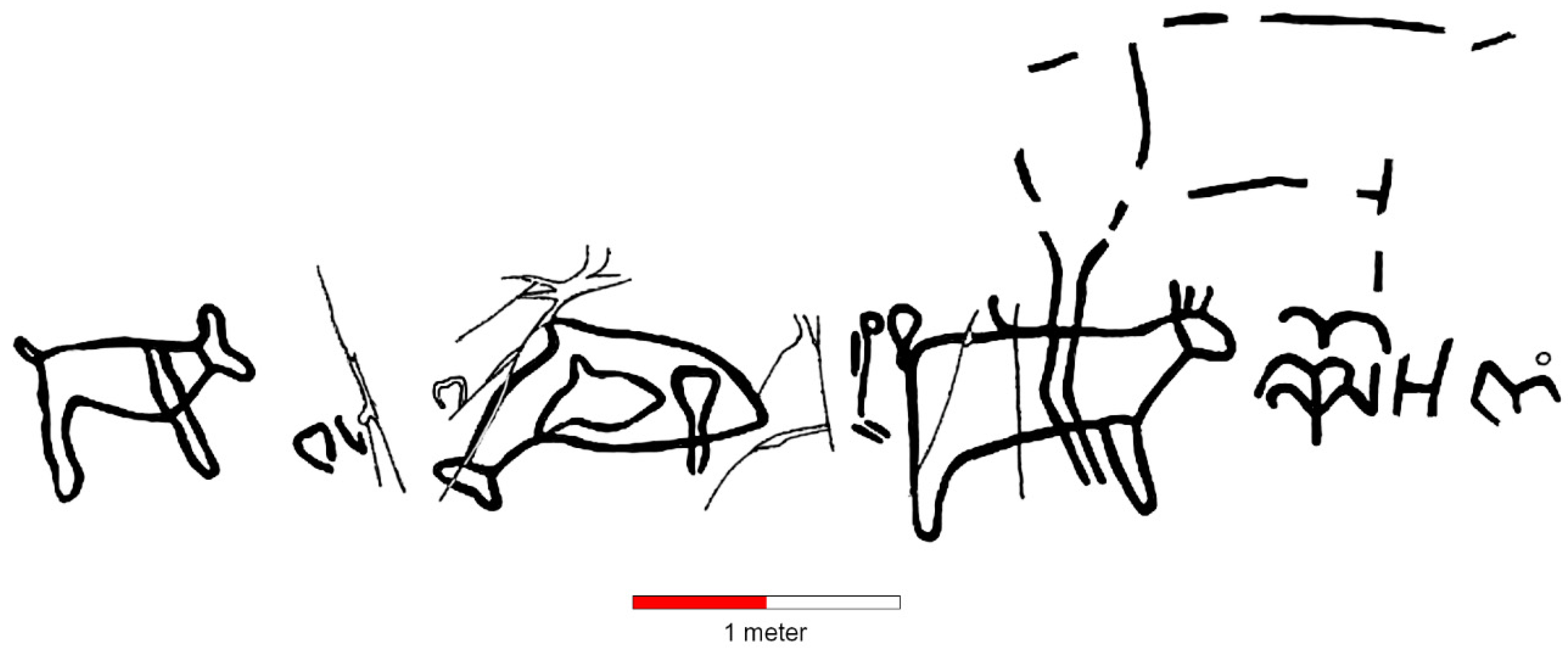

3.3. Transformation of Species

4. Discussion

Visualising the Unseen

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abram, David. 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous. Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Åstveit, Liv Ingeborg. 2008. Semmesolittisk tid (SM) 6500–4000 BC. In NTNU Vitenskapsmuseets arkeologiske undersøkelser Ormen Lange Nyhamna. Edited by Hein Bjartmann Bjerck, Leif Inge Åstveit, Trond Meling, Jostein Gundersen, Guro Jørgensen and Staale Normann. Trondheim: Tapir, pp. 576–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bakka, Egil. 1979. On Shoreline Dating of Arctic Rock Carvings in Vingen, Western Norway. Norwegian Archaeological Review 12: 115–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belting, Hans. 2011. An Anthropology of Images. Picture, Medium, Body. Oxford: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benz, Marion, and Joachim Bauer. 2014. Symbols of Power—Symbols of Crisis? A Psycho-Social Approach to Early Neolithic Symbol Systems. Neo-Lithics Special Issue 2: 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bergsvik, Knut Andreas. 2001. Sedentary and mobile hunter-fishers in Stone Age western Norway. Arctic Anthropology 38: 2–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bergsvik, Knut Andreas, Kim Darmark, Kari Loe Hjelle, Jostein Aksdal, and Leif Inge Åstveit. 2021. Demographic developments in Stone Age coastal western Norway (8000–3800 cal BP) by proxy of radiocarbon dates, stray finds and palynological data. Quarternary Science Reviews 259: 106898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerck, Hein B. 2008. Norwegian Mesolithic trends. A review. In Mesolithic Europe. Edited by Geoff Bailey and Penny Spikins. New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 60–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, Maurice. 1982. Death, women and power. In Death and the Regeneration of Life. Edited by Maurice Bloch and Jonathan Parry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 211–30. [Google Scholar]

- Boric, Dušan. 1997. ‘Body Metamorphosis and Animality’: Volatile Bodies and Boulder Artworks from Lepenski Vir. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 15: 35–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bredekamp, Horst. 2015. Image Acts. A Systematic Approach to Visual Agency. Boston: De Gruyter, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Brøgger, Anton Wilhelm. 1906. Elg og ren paa helleristningerne i det nordlige Norge. Naturen 30: 356–60. [Google Scholar]

- Brøgger, Anton Wilhelm. 1925. Det norske folk i oldtiden. Instituttet for sammenlignende kulturforskning serie A Via. Oslo: Aschehoug. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Grahame. 1954. Excavations at Starr Carr. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conneller, Chantal. 2004. Becoming deer. Corporal transformations at Star Carr. Archaeological Dialogues 11: 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conneller, Chantal, and Ben Elliott. 2025. Metamorphosis. In The Oxford Handbook of Mesolithic Europe. Edited by Liv Nilsson Stutz, Rita Peyroteo Stjerna and Mari Tõrv. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Descola, Philippe. 2013. Beyond Nature and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, Oliver, Jens Notroff, and Laura Dietrich. 2018. Masks and masquerade in the Early Neolithic: A view from Upper Mesopotamia. Time and Mind 11: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, Ben, and Graeme M. Warren. 2023. Colonialism and the European Mesolithic. Norwegian Archaeological Review 56: 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuglestvedt, Ingrid. 2018. Rock Art and the Wild Mind. Visual Imagery in Mesolithic Northern Europe. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gjerde, Jan Magne. 2010. Rock Art and Landscapes: Studies of Stone Age Rock art from Northern. Fennoscandia. Ph.D. dissertation, Archaeology, University of Tromsø, Tromsø, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Gjessing, Gutorm. 1936. Nordenfjeldske Ristninger og Malinger av den Arktiske Gruppe. Serie B: Skrifter 30. Oslo: Institutt for Sammenlignende Kulturforskning. [Google Scholar]

- Goldhahn, Joakim, and Sally K. May. 2019. Beyond the colonial encounter: Global approaches to contact rock art studies. Australian Archaeology 84: 210–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigson, C., and P. Mellars. 1987. The mammalian remains from the middens. In Excavations on Oronsay: Prehistoric Human Ecology on a Small Island. Edited by Paul Mellars. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 243–89. [Google Scholar]

- Groucutt, Huw S., Amy L. Prendergast, and Felix Riede. 2022. Editorial: Extreme events in human evolution: From the Pliocene to the Anthropocene. Frontiers in Earth Science 10: 1026989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünberg, Judith M. 2000. Mesolithische Bestattungen in Europa: Ein Beitrag zur vergleichenden Gräberkunde. Internationale Archäologie 40. Rahden: Leidorf. [Google Scholar]

- Guemple, Lee. 1994. The Inuit cycle of spirits. In American Rebirth: Reincarnation Belief Among North American Indians and Inuits. Edited by Antonia Curtze Mills and Richard Slobodon. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 107–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hagen, Anders. 1969. Studier i vestnorsk bergkunst: Ausevik i Flora. In Årbok for Universitetet i Bergen. Humanistisk Series 3. Bergen: Norwegian Universities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hallowell, A. Irving. 1975. Objibwa ontology, behavior, and world view. In Teachings from the American Earth. Edited by Dennis Tedlock and Barbara Tedlock. New York: Liveright, pp. 141–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hallström, Gustaf. 1938. Monumental Art of Northern Europe from the Stone Age. I. The Norwegian Localities. Stockholm: Thule. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Andr M. 1904. Landnåm i Norge: En utsigt over bosætningens historie. Oslo: Fabritius. [Google Scholar]

- Helskog, Knut. 1990. Sjamaner, Endring og Kontinuitet. Relasjoner mellom Helleristninger og Samfunn med utgangspunkt i helleristningene i Alta. Finnlands Antropologiska Sälskaps Publikasjoner 1: 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Helskog, Knut. 1999. The Shore Connection. Cognitive Landscape and Communication with Rock Carvings in Northernmost Europe. Norwegian Archaeological Review 32: 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Erica. 2011. Animals as Agents Animals as Agents: Hunting Ritual and Relational Ontologies in Prehistoric Alaska and Chukotka. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 31: 407–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelle, Kari Loe, and Trond Klungseth Lødøen. 2017. Dating of rock art and the effect of human activity on vegetation: The complementary use of archaeological and scientific methods. Quaternary Science Reviews 168: 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodder, Ian. 1990. The Domestication of Europe: Structure and Contingency in Neolithic Societies. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Howsare, Erika. 2024. Age of the Deer. Trouble and Kinship with Our Wild Neigbours. London: Ikon Books Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Gregory A. 1982. Organizational structure and scalar stress. In Theory and Explanation in Archaeology. Edited by Colin Renfrew, Michael. Rowlands and Barbara Abbott Segraves. New York: Academic Press, pp. 389–421. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, Peter. 2011. Material Culture Perspectives on the World View of Northern Hunter-Gatherers. In Structured Worlds. The Archaeology of Thought and Action. Edited by Aubrey Cannon. Sheffield: Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, Erlend Kirkeng, and Felix Riede. 2019. Convergent Catastrophes and the Termination of the Arctic Norwegian Stone Age: A Multiproxy Assessment of the Demographic and Adaptive Responses of Mid-Holocene Collectors to Biophysical Forcing. The Holocene 29: 1782–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannegaard Nielsen, E., and E Brinch Petersen. 1993. Grave, mennesker og hunde. In Da klinger i muld…25 års arkeologi i Danmark. Edited by Steen Hvass and Birger Storgaard. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitets forlag, pp. 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen, Kristian. 2014. Towards a new paradigm? The third science revolution and its possible consequences in archaeology. Current Swedish Archaeology 22: 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, Lars, Christopher Meiklejohn, and R. Raymond Newell. 1981. Human skeletal material from the Mesolithic site of Ageröd I:HC, Scania, southern Sweden. Fornvännen 76: 161–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1983. The Way of the Masks. London: Thirty Bedford Square. [Google Scholar]

- Lidén, Kerstin, and Gunilla Eriksson. 2013. Archaeology vs. Archaeological Science. Do we have a case? Current Swedish Archaeology 21: 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lødøen, Trond Klungseth. 2013. Om alderen til Vingen-ristningene. Viking 76: 7–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lødøen, Trond Klungseth. 2014. På sporet av senmesolittiske døderiter: Fornyet innsikt i alderen og betydningen av bergkunsten i Ausevik, Flora, Sogn og Fjordane. Primitive Tider 16: 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lødøen, Trond Klungseth. 2015. Treatment of corpses, consumption of the soul and production of rock art: Approaching Late Mesolithic mortuary practices reflected in the rock art of western Norway. Fennoscandia Archaeologica 62: 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lødøen, Trond Klungseth. 2017a. The Meaning and Use(-fullness) of Traditions in Scandinavian Rock Art Research. Swedish Rock Art Research Series 6: 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lødøen, Trond Klungseth. 2017b. Whale images in the Northern Tradition Rock art of Norway, and their potential mythological and religious significance. In Whale on the Rock. Ulsan: Ulsan Petroglyph Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Lødøen, Trond Klungseth. 2022. Exploring ideas behind the whale images in the Norwegian Rock Art Record. Les Nouvelles de L’archéologie 166: 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lødøen, Trond Klungseth. 2025. Rock Images of the Dead: Glimpses of Past Mortuary Processes or Pictures of a Plague. In The Oxford Handbook of Mesolithic Europe. Edited by Liv Nilsson Stutz, Rita Peyroteo Stjerna and Mari Tõrv. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lødøen, Trond Klungseth, and Gro Mandt. 2010. The Rock Art of Norway. Oxford: Windgather Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lødøen, Trond Klungseth, and Gro Mandt. 2012. Vingen—Et Naturens Kolossalmuseum for Helleristninger. Instituttet for Sammenlignende Kulturforskning, Serie B Skrifter 146. Trondheim: Akademika. [Google Scholar]

- Lundström, Victor. 2023. Living through changing climates: Temperature and seasonality correlate with population fluctuations among Holocene hunter-fisher-gatherers on the west coast of Norway. The Holocene 33: 1376–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantere, Ville. 2023. The Relationship Between Humans and Elks (Alces alces) in Northern Europe c.12000–1200 cal Bc. Ph.D. thesis, Department of Archaeology, University of Turku, Turku, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Meisingset, Erling L. 2008. Alt om hjort. 2. utgave (Hjort og hjortejakt i Norge). Oslo: Naturforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf, Peter, and Richard Huntington. 1979. Celebrations of Death: The Anthropology of Mortuary Ritual. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen, Egil. 1977. Østnorske veideristninger: Kronologi og økokulturelt miljø. Viking 40: 147–202. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, Kenneth M. 2000. The cosmos as intersubjective: Native American other-than-human persons. In Indigenous Religions: A Companion. Edited by Graham Harvey. London: Cassell, pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mosko, Mark S. 2008. Ways of Baloma. Rethinking Magic and Kinship from the Trobriands. Chicago: Hau Books. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson Stutz, Liv. 2003. Embodied Rituals & Ritualized Bodies: Tracing Ritual Practices in Late Mesolithic Burials. Acta Archaeologica Lundensia Series in 8º, No 46. Lund: University of Lund. [Google Scholar]

- Porr, Martin, and John Matthews. 2017. Post-Colonialism, Human Origins and the Paradox of Modernity. Antiquity 91: 1058–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, C., and E. Walderhaug. 1995. The last frontier? Processes of Indo-Europeanization in Northern Europe: The Norwegian Case. The Journal of Indo-European Studies 23: 257–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rio, Knut. 2020. The fetish and its destruction: Spiritual control in Africa and Melanesia. In Negotiating Memory from the Romans to the 21st Century: Damnatio Memoriae. Edited by Øivind Fuglerud, Kjersti Larsen and Marina Prusac-Lindhagen. London: Routledge, pp. 212–30. [Google Scholar]

- Schülke, Almut, Kristin Eriksen, Sara Gummesson, and Gaute Reitan. 2019. The Mesolithic inhumation at Brunstad—A two step multidisciplinary excavation method enables rar insights into hunter-gatherer mortuary practice in Norway. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 23: 662–73. [Google Scholar]

- Shetelig, Haakon. 1922. Primitive tider: En oversigt over stenalderen. Bergen: Johan Griegs forlag. [Google Scholar]

- Sognnes, Kalle. 2017. The Northern Rock Art Tradition in Central Norway. BAR International Series 2837. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, Tim Flohr. 2017. The Two Cultures and a World Apart: Archaeology and Science at a New Crossroads. Norwegian Archaeological Review 50: 101–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storm, Louise. 1995. The Hind Game—Seen in the Light of European Cervine Tradition. Bergen: Forlaget Folkekultur. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Julian. 1999. Understanding the Neolithic. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tonna, Matteo, Carlo Marchesi, and Stefano Parmigiani. 2019. The biological origins of rituals: An interdisciplinary perspective. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 98: 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. 1998. Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism. Journal of Royal Anthropological Institute 4: 469–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. 2012. Cosmological Perspectivism in Amazonia and Elsewhere: Four Lectures Given in the Department of Social Anthropology, Cambridge University, February–March 1998. Masterclass Series 1. Manchester: HAU Network of Ethnographic Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Willerslev, Rane. 2007. Soul Hunters: Hunting, Animism and Personhood Among the Siberian Yukagirs. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zwelebil, M. 1993. Concepts of time and ‘presenting’ the Mesolithic. Archaeological Review from Cambridge 12: 51–70. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lødøen, T.K. Human Skeletons in Motion, Defleshed Animals in Action and Transformation of Species in Northern Tradition Rock Art. Arts 2025, 14, 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14050116

Lødøen TK. Human Skeletons in Motion, Defleshed Animals in Action and Transformation of Species in Northern Tradition Rock Art. Arts. 2025; 14(5):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14050116

Chicago/Turabian StyleLødøen, Trond Klungseth. 2025. "Human Skeletons in Motion, Defleshed Animals in Action and Transformation of Species in Northern Tradition Rock Art" Arts 14, no. 5: 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14050116

APA StyleLødøen, T. K. (2025). Human Skeletons in Motion, Defleshed Animals in Action and Transformation of Species in Northern Tradition Rock Art. Arts, 14(5), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14050116