Abstract

Drawing on archaeological evidence, early ethnographic accounts, and historical documents, this article offers initial reflections on the possible past uses and meanings of a set of black drawings found deep within a cave in what is now known as the Sierra Mixe of Oaxaca, Mexico. Following this investigative approach, it explores the role of rock art as an interface between orality, imagery, and text in the context of ancient Mesoamerica. To understand the possible ontological perceptions of the creators of these images in the past, it is suggested that this imagery functioned as inscriptions in a dialogue with spatially related unfired figures modelled in clay, which are exceptionally well-preserved in this subterranean space. An interplay of media on various supports is proposed, wherein two-dimensional images and three-dimensional figures may have been used as a combined system for transmitting and circulating intergenerational cultural knowledge, serving as an anchor for collective memory. In this context, rock imagery played a role in a broader communication system in Mesoamerica.

Keywords:

orality; text; rock art; writing; unfired clay; Oaxaca; Mesoamerica; knowledge transmission; iconography; collective memory; cave 1. Introduction

Thinking of orality in opposition to writing has constrained our ability to envision the ample use-perceptions of rock art in so-called oral cultures. This antagonistic perspective lacks a proper understanding of the articulations between language and iconography. Scholars have warned us against the West’s narrow views, which have misled us from fully understanding the multifaceted communication systems that encompass ritual gestures, speech, and images of societies with allegedly “no writing” (Severi 2015, pp. 14, 47). Nonetheless, the question remains: what is writing, particularly when viewed as an evolutionary goal? (Boone and Mignolo 1994, p. 3; Lacadena García-Gallo 1995, p. 601; Velásquez García 2012, p. 130) In the Mesoamerican context, within which this article is framed, this enquiry considers non-alphabetic writing to raise awareness of the multimodal literacies developed by Indigenous peoples in the past (Jiménez and Smith 2008). In this sense, it reflects on the implications of equating rock imagery with a writing system.

Comparing rock art to a form of visual language to analyse its underlying structure and contents, and propose possible meanings, is not new to rock art research. Since the discovery of Palaeolithic art in the 19th century, linguistic models have been deployed to explain the order, placement, superimpositions, and frequency of images depicted on rock walls. For instance, André Leroi-Gourhan (1982, 1993) rigorously analysed the imagery from several sites (e.g., Lascaux, Le Cap Blanc, Rouffignac, Combarelles, La Loja, Ekaîn, Altamira, and others) across various supports (i.e., painting, sculpture, engraving on stone, bone, clay), searching for the technical and aesthetic characteristics of the images (i.e., superimpositions, perspective, volume), but also to understand the relationships between the paintings as “oral symbols in a material form” (Leroi-Gourhan 1982, p. 43). Through this study, he formulated his horse–bison complementarity and opposition hypothesis and proposed a symbolic organisation of the subterranean space.

In a similar quest to comprehend form and order, some scholars have argued that the underlying narrative behind the composition of rock images is similar to a text from which messages can be read. Influenced by the works of Jacques Derrida (1997), Ferdinand de Saussure et al. (1959) and Roland Barthes (1973) on the symbolic properties of images and the relationship between signifier and signified, as well as the denotative and connotative levels of meaning in writing and speech, Christopher Tilley (1991) proposed a complex interpretative advance in his approach to material culture and text. He aimed to explain the association between motifs through the recognition of individual units of “visual text”, their relationships, combinations, and repetitive structure (Tilley 1991, pp. 20–23) at Nämforse, Sweden, one of the largest sites of rock engravings worldwide. Following a quadripartite division of the disposition of topographical units or sectors, he recognised arbitrary pages of text where, allegedly, words, sentences, and grammar could be singled out based on the distinction of each image. In his attempt to understand meaning and non-verbal communicative practices, images were equated to linguistic signs to establish a relationship between the signifier, as a visual image, and the signified, as a thing or concept.

In a sample of rock art sites from the Giant’s Castle in Natal Drakensberg, South Africa, David Lewis-Williams (1972) used a simple finite state grammar to analyse the superimposition of images, demonstrating how the choice of an initial painting affected the selection of the second painting. He later dismissed this approach, considering the nature of images infused with rich metaphors that cannot be interpreted as text (Lewis-Williams 1980). Harald L. Pager’s thorough record of the Brandberg imagery in Namibia served as the foundation for a conceptual framework in which Tilman Lenssen-Erz deployed a linguistic model on the paintings of the Amis George Valley (Pager 1989, p. 361). In doing so, he highlighted that the production of spoken words and painted communications shared a common source in human thinking and language, proof of our shared humanity. Therefore, he contended that the artists encoded some linguistic concepts in their paintings. In particular, he emphasised that a cohesive relationship between subject, action, and object was established in the minds of the painters through scenes based on differences in size, colour, body attachments, and other aspects of these elements (Lenssen-Erz 1992).

Recent studies in North America suggest that the rock art of the Lower Pecos at the White Shaman site in Texas, United States, could be equated to a visual text with a structure based on a continuum of ideas stemming from intercultural and socially shared patterns in ancient times. Following a linguistic and semiotic framework, a detailed analysis of the superimpositions revealed the structure of the painting process: black, red, yellow, and white as a single composition to communicate an idea (Boyd and Cox 2016, p. 44) in which figures and their attributes were treated as signs with the purpose of creating a narrative.

Despite these commendable and meticulous studies and analyses of a large corpus of imagery in each cultural context and geographical setting mentioned above, many questions remain unanswered: Was there a clear-cut division in the minds of the creator(s) between a signifier and a signified? If rock art can be equated to a writing system, did people ”write” the same way for thousands of years? And if so, do grammar and syntax endure unaltered? The linguistic approach remains controversial in rock art research, particularly when it comes to equating images with a form of writing. This is not only because the latter is already a reduction of spoken language, which would simplify its meaning, but also because, while rock art is indeed a complex and rich visual form of communication in which images, following cultural conventions, convey a narrative in specific contexts, or in which a single image alone stands as an idea, it is not encoded speech.

Additionally, a rock art panel is not reducible to the linearity of text (Gosden 1992, p. 807; Helskog 1991; Leroi-Gourhan 1982, p. 66), which would require finding a starting point in the composition and forcing the rest of the images to fit a specific order, ineludibly contingent on the researcher in most cases. Furthermore, we might fall into the trap of seeking image frequencies instead of their spatial distribution and assuming that images were created at the same time, thus giving us no chance to understand continuity and change (Helskog 1991, p. 993; Hodder 1989, p. 260, for discussion on material culture).

What makes it more difficult for us archaeologists to interpret rock art is that meaning is not embedded in the image alone, but is linked to the intentions and practical contexts of the reader, user, or viewer (Hodder 1989), as well as the experience and embodiment of the usages behind rock imagery. In this context, research on rock art in conjunction with Indigenous knowledges and ethnography in other parts of the world, such as the Kimberley in Western Australia (O’Connor et al. 2022), Northwest Amazonia (Tuyuka et al. 2022), or south-central Africa (Zubieta 2016), demonstrates that performances, actions, songs, storytelling, dancing, repetition, rubbing, and smoking are some vital aspects of remembering and recalling cultural knowledge linked to the imagery (Zubieta 2022a, p. 14). It is in this sense that orality features in this paper: not as the opposite of writing, but as the capacity for verbal communication embedded in oral traditions and the utterance of words or sounds in combination with images for transmitting and circulating knowledge in specific contexts (Severi 2015, p. 13).

I do not have any wide-ranging answers to the questions posed above, but some initial ideas emerge from the Mesoamerican context that I cursorily explore in this paper. To this end, an intriguing turn arises from Mesoamerican societies that developed pictorial writing systems, beginning with the Olmec as early as ca. 900 BCE, followed by others, such as the Zapotec, Maya, Mixtec, and Nahua. These cultures depicted these images on various materials, such as ceramics, bone, animal skin, and paperbark (amate), as well as on the walls of shelters and caves. Should we regard such rock imagery in caves and shelters as a form of text? Could we then apply a linguistic approach to analyse this subset of rock art? Should this be referred to as a subset of rock art at all, or as writing? A set of black drawings associated with unfired clay figures, preserved within the depths of Cueva del Rey Kong-Oy (or Kondoy)1 in the Sierra Mixe, Oaxaca, Mexico, offers the possibility of exploring these questions. Although there are limitations mainly due to the lack of a precise chronology—resulting from missing dates for archaeological deposits and the paintings—a linguistic approach to this rock imagery, combined with rock art research methods, seems to be a suitable avenue for analysis, as I propose later in this paper.

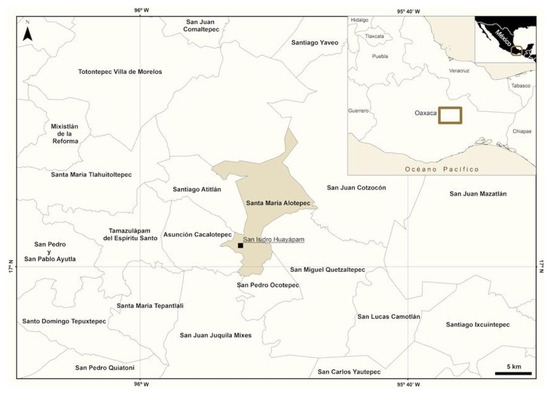

Since 2011, Cueva del Rey Kong-Oy (or Kondoy), a cave closed to the public due to the fragile condition of the archaeological evidence inside, has revealed an extensive repertoire of life-size unfired earthen figures2, rock paintings, and human remains, providing a window into the ritual practices and artistic abilities of the past cultures that inhabited the still archaeologically underexplored Mixe Region of Oaxaca (Ballensky 2012; Winter 2020; Winter et al. 2014; Zubieta 2021; Zubieta Calvert et al. 2025). Thus, it contributes to broadening our understanding of ancient Mixe social and political organisations and networking with other groups. This limestone cavern is located3 in the communal land of the Ayuuk ja’ay or Mixe of San Isidro Huayápam (also known as Pox am, “land of guavas” in the Ayuuk language), southwest of what is referred to as “Mixe media” or Middle Mixe Highlands in the State of Oaxaca, Mexico (López Santiago and Barajas Gómez 2013; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map showing the location of San Isidro Huayápam (Pox am) in the Sierra Mixe region of Oaxaca, Mexico.

People in Pox am have known about the cave’s entrance for many generations, yet not everyone has visited the site to this day. Some still recall a commercial pathway that passed a few metres from the entrance, serving as access to neighbouring communities, as far as the town of Juquila Mixes, founded in the 16th century, 11 km southwest of San Isidro, as the crow flies (Kuroda 1976, p. 349). A few remember stories of elders or abuelitos (grandparents) exploring the cave in the past (Zubieta 2021, p. 1172). Still, there is no record of stories about the clay figures and rock paintings inside the cave before 2011. To the best of my knowledge, there are no recent memories or oral traditions of clay figures in neighbouring settlements, although there are some recollections concerning the cave’s entrance.

The careful use of available ethnographic accounts and historical sources regarding Indigenous knowledges and writing systems in Mesoamerica, alongside analogical inferences, is presented here to formulate hypotheses about the past societal uses, meanings, and significance of this archaeological material. This endeavour does not imply that such interpretations can be easily understood or unambiguously explained from this perspective. However, these types of analyses have indeed helped reshape our Eurocentric perceptions of the objects we study, considering the temporal and explanatory limitations of analogy (Wylie 1988). Further research, beyond the scope of the present study, is underway to explore the content of the black drawings. For now, my concern in this paper is with how meaning could have become in the context of the cave. Therefore, it is an initial effort to explore potential avenues for future analysis.

2. Rock Art and Indigenous Knowledges Transmission Systems in Mesoamerica

Extensive evidence of rock imagery, painted and engraved by diverse social groups, exists across present-day Mexican territory and has been the subject of rigorous studies by numerous scholars (Murray et al. 2016; Ramírez Castilla et al. 2015; Viramontes Anzures et al. 2023). For example, large-scale images of human and animal bodies in red, black, yellow, and white cover the shelters in the steep canyons of Sierra de San Francisco in Baja California (Gutiérrez and Hyland 2002; Viñas 2004; Figure 2); hundreds of engravings depicting antlers, hooves, concentric circles, counting systems, and lithic artefacts were carved on concentrations of sandstone boulders at Boca de Potrerillos in Nuevo León (Murray 1982; Valadéz Moreno et al. 1998; Figure 2); white-painted images of snakes, humans, astronomical figures, and temples can be found in the gullies (barrancas) of Valle del Mezquital, in Hidalgo (Lerma et al. 2014; Figure 2). Besides these varied forms, techniques and colours in the Mexican rock art repertoire, some other imagery found in rock shelters and caves resembles the iconography deployed in the logosyllabic writing developed by Mesoamerican peoples, such as the Zapotec, Maya, Nahua, and other groups.

Figure 2.

Locations of some sites referenced in this paper.

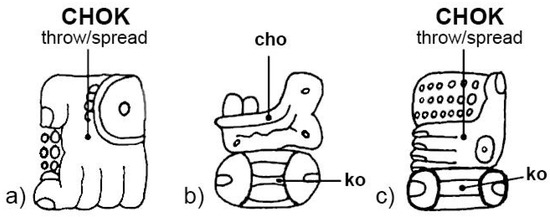

The logosyllabic system essentially consists of two functionally distinct types of phonetic signs: logographs (word signs with meaning) and syllabic signs or syllabograms, which are used solely to convey sound without meaning, becoming the graphic reference of a sound (Roman-Rangel et al. 2011, p. 103). Some logographs have an iconic relationship with the word they refer to (Lacadena García-Gallo 1995, p. 601). For instance, a jaguar head can be used to represent the word “jaguar” and is transliterated in capital letters, transcribed in italics, with translations enclosed in quotation marks. For example, consider a Maya expression such as “throw/spread.” This could be written in a logographic form: CHOK, chok, “throw/spread.” If represented syllabically, this would become cho-ko, chok, “throw/spread,” and both combined in a logosyllabic form: CHOK-ko, chok, “throw/spread” (Velásquez García 2010; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Maya word for throw/spread shown as (a) logographic, (b) syllabic, and (c) logosyllabic forms (modified from Velásquez García 2010).

The rock imagery that resembles certain aspects of Mesoamerican writing differs from the others mentioned earlier in this section because the latter probably communicated meaning as a phonetic script in which logograms were used to refer to whole words rather than individual sounds, and also syllables in some contexts. This imagery comprises specific glyphs for the days and months of the agricultural and ritual calendars, sometimes accompanied by a counting system of bars and/or circles for numbers. Examples of this type of imagery have survived in various caves throughout the Maya region in Yucatán (e.g., Loltun; Thompson 1897), Guatemala (e.g., Naj Tunich, Santo Domingo, Las Pinturas caves) (Saravia Orantes and Saravia Orantes 2020); in Guerrero at Juxtlahuaca (Gay 1967) and Oxtotitlan (Grove 1970; Lambert 2012); in Oaxaca, at El Puente Colosal in the Mixteca area of the northern Coixtlahuaca basin (Rincón Mautner 2005; Urcid 2005a), and Ba’cuana (Berrojalbiz 2017; Zárate Morán 2003); as well as at Zopiloapam (Rivas Bringas 2019) in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (Figure 2).

While Maya hieroglyphic writing has been the most documented and studied since the 16th century (Thompson 1965), extensive iconographic research has been conducted on the many examples left through time by the Olmec (Joralemon 1971), epi-Olmec or Istmian (Justeson and Kaufman 1993), Zapotec (Caso 1946; Urcid 2005b), Mixtec (Troike 1990), Nahua (Boone 2020; Lacadena 2008), and others. Relevant to our discussion, as early as 2580–2510 B.P., the Zapotec had a complex visual communication writing system (Flannery and Marcus 2003, p. 11803) that persisted until the Spanish contact. It is known that the Zapotecs employed a form of writing in which they combined what has been called hieroglyphics or inscriptions arranged in columns with figurative images on various supports such as ceramics, stone, and canvases (Oudijk and Jansen 1998, p. 53) to communicate alliances and conquests of rulers.

Francisco de Burgoa (1671), a Dominican priest and historian, mentions in Oaxaca the use of bark from specific trees in hot lands ”tierra caliente” as sheets to create their ”books” (codices) by knitting them together and decorating them with such ”abbreviated characters” that a single page contained information about a place, the province, the year, month, day, the name of Gods, sacrifices, victories, and related stories. In addition to the survival of characters made on perishable materials, such as codices (e.g., Tonindeye or Nutall), the records concerning their manufacture, the individuals involved, and the expressed themes and perceptions, as well as their uses by Mesoamerican peoples to memorise stories, are even more remarkable.

[…] they wrote with such abbreviated characters that on a single page they expressed the place, site, Province, year, month and day, with all the other names of Gods, ceremonies and sacrifices, or victories that they had celebrated and had. For this purpose they taught and instructed the children of the Lords and those they chose for their Priesthood in their childhood by making them decorate those characters and memorise the stories. I have had these same instruments in my hands, and heard them explained by some old people with quite a bit of admiration, and they used to put these papers, like Cosmography tables pasted lengthwise in the rooms of the Lords, out of grandeur and vanity, boasting of dealing with those matters in their meetings and visits…4 (Burgoa 1671, Idea de los libros y historias de Oaxaca, author’s translation)

Population migrations, the foundation of sites, the history of the origins of the ruling lineage, and the territorial boundaries of specific villages were common themes expressed in various forms of support (e.g., ceramics, stelae). Such concerns and the practices of communicating them, rooted in pre-Hispanic times, permeated into Colonial times and continued throughout the 19th century to the present day (Berrojalbiz 2017; Oudijk and Romero Frizzi 2003). The continuity of Indigenous traditional worldviews is reflected in the numerous lienzos5 found in Oaxaca (e.g., Guevea, Zacatepec, Tulancingo) produced during Colonial times, in which scribes used a mix of pictograms, alphabetic characters (both in Latin and Nahuatl), and glosses that commented on or explained the images (Oudijk and Romero Frizzi 2003; Sousa 2016). These practices demonstrate the versatility of Mesoamerican peoples in adapting, incorporating, and utilising foreign elements to convey information during the phase of transculturation.

With its 3000 years of history and recognised geographic influence, Olmec writing likely played a significant role in inspiring the development of other pictorial writing systems in Mesoamerica, which shared common traits including a logosyllabic system, vigesimal numeration, and a 260-day calendar system (Velásquez García 2010). The significance of the Olmec in the proliferation of pictorial writing systems has been extensively investigated, with evidence suggesting that the Olmec possessed a Mixe-Zoquean language (Campbell and Kaufman 1976; Wichman 1995; Velásquez García 2010). Therefore, it is highly possible that the social groups who lived in today’s Mixe region of Oaxaca shared traits similar to those of others in Mesoamerica in the past, such as the use of pictorial writing systems and agricultural and ritual calendars. The presence of black drawings alongside delicate, unfired clay reliefs and sculptures preserved within the depths of the Sierra Mixe in Oaxaca offers a unique opportunity to explore the interface of images, orality, and text as a joining point where various forms of expression meet, engage, and constitute each other within a sacred cave in Mesoamerica.

3. Materials and Methods

The Mixe region remains archaeologically underexplored; some studies have focused on analysing artefacts from private collections (Hutson 2014), reported field surveys and settlement patterns in the upper part of the Sierra Mixe (Rivero López 2011), and described archaeological sites featuring monuments and ball courts (Gómez Bravo 2004; Winter 2008). Since 2011, the Cueva del Rey Kong-Oy material has inspired further archaeological surveys and the rescue of a tomb a few kilometres from the cave (Markens and Winter 2014), as well as additional ethnoarchaeological recording of the cave’s unfired clay figures and rock paintings in collaboration with the local Mixe people (Zubieta 2021), and a deeper understanding of the production process of the earthen figures (Zubieta Calvert et al. 2025).

Conversely, the Mixe region has been the focus of extensive anthropological research (e.g., Bautista Santaella 2013; Beals 1945; Bernal Alcántara and Molina Domínguez 2021; Kuroda 1976; Lipp 1991; Pitrou 2011, among others), which offers us many insights into the ritual practices, philosophy, and ideology of the Ayuuk ja’ay (Mixe) people, who inhabit the territory where the cave is located. Ethnographic studies on the worldviews of the Mixe and neighbouring groups offer an initial framework for exploring perceptions and modern values regarding the cave (Zubieta 2021), as well as hypothesising about the functions and meanings of certain cultural aspects of the cave. For example, countless caves and other landscape features are linked to the mythical character of Rey Kong-Oy for the Ayuuk ja’ay (Barabas and Bartolomé 1984; Bernal Alcántara and Molina Domínguez 2021, p. 105) and hence Cueva del Rey Kong-Oy holds great importance for the people of San Isidro Huayápam and, more broadly, to the Mixe population (Bernal Alcántara and Molina Domínguez 2021, p. 47; Zubieta 2021).

The Rey Kong-Oy is a legendary figure recognised to varying degrees throughout the Mixe region for his heroic struggles against the Mexica from central Mexico and the Ñudzahu (Mixtec) from western Oaxaca. He is primarily celebrated as the leader of the resistance against the Bènizàa (Zapotec), who were historically seen as adversaries of the Ayuuk ja’ay (Barabas and Bartolomé 1984, p. 10). While a direct chronological correlation cannot be assumed between Kong-Oy’s story and the material inside the cave at this time, the site’s association with this mythical hero renders it a significant place in both Mixe collective memory and their evolving identity today.

3.1. Cueva del Rey Kong-Oy (or Kondoy)

The town of San Isidro, situated at 1050 masl, enjoys a temperate climate with slight elevations characterised by oak and pine trees associated with the steep mountainous elevations of the Mixe territory, which rise more than 1500 masl. The entrance to the cave (590 masl) is about 60 m from a permanent river known locally as the Río Grande, providing warmer temperatures and a wide variety of fruit trees (such as sapote, banana, mango, passion fruit, and mamey). It also supports organic coffee plantations and traditional subsistence maise and bean agriculture. More than 350 m into the depths of the cave, this project has recorded seventy-two clay-modelled figures since 2018, resting on top of 1–1.6 m high clay deposits along the course of a narrow (1–2 m wide) subterranean crystalline stream.

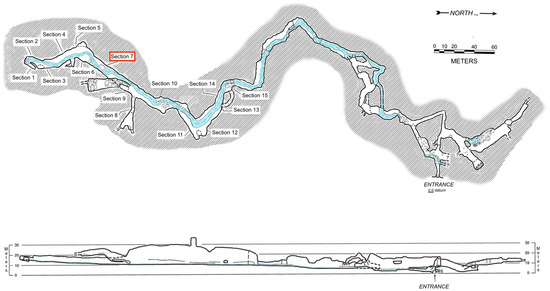

These modelled earthen figures are mostly reliefs, whose volume protrudes from the floor, and some sculptures in the round, of humans, animals, and architectural features (Zubieta 2021, p. 1175; Zubieta Calvert et al. 2025). The southern corridor, our area of focus, was divided into 15 sections in consecutive order (e.g., Sections 1, 2, 3, and so on; see Figure 4), on the left and right sides of the river towards the end of the cave (upstream), in accordance with the presence of rock art and clay figures. The arbitrary organisation of the space responded to practical needs encountered during the documentation process rather than stemming from an intended arrangement by the users of those spaces.

Figure 4.

Cave plan showing the sections of the cave and specifically Section 7 (in red) discussed in this paper. Compass and Disto survey by Jason Ballensky, Tamara Ballensky, Philip Rykwalder, Rob Spangler and Elliot Stahl. Cartography by Bob Richards (Modified from Ballensky 2012).

Human figures are generally found in a supine or frontal seated position, with their backs or heads reclined against the wall and exposing their genitalia. At least twenty-two of these figures are female, featuring pronounced vulvas. Although the clay figures are typically closer to the cave’s back wall, a few examples lie near the edges of the terraces, close to the stream, and some have suffered erosion, possibly due to rising water levels and the passage of people. Some better-preserved figures bear body decorations (e.g., tattoos, scarification, or body paintings), accoutrements (e.g., headdresses, sandals), and remnants of red and black pigment on their faces and bodies. Notably, there is a lack of abundant archaeological artefacts on the surface near the earthen figures. By bridging Indigenous knowledge, ethnography and archaeology, it has been proposed elsewhere that the earthen figures (human or nonhuman) are agentive and sentient beings that have a relational entanglement and mutually constitute each other (Zubieta 2021). In Mesoamerican thought and action, the intricate connections of numerous beings, with multiple associations and expressions, whose agencies impact each other, are evident not in a binary way but rather in various dimensions.

Red, orange, and black colours were observed on the cave walls during our initial survey in 2018, but no engravings have yet been discovered. We reported a new black drawing of a person wearing a mask in profile, two possible abstract representations of masks in black colour, an isolated drawing of a “skull” in black colour, a few examples of solid/infilled black rectangles and other geometric shapes, smudged black surfaces, hundreds of black lines, and three small (6 cm in diameter) circles with internal designs in black colour. Paintings generally occur on light-coloured rock faces behind the clay reliefs and sculptures, as well as on the opposite walls directly in front of the clay figures. However, it was noted that black colour was predominantly used to create linear drawings, such as masks in profile and both negative and positive hand stencils closer to the clay figures. Some vertical and longer horizontal black lines observed in Sections 2, 5, 7, and 15 were probably parts of larger drawings that are no longer visible.

In contrast, the red colour was used in the deeper parts of the cave where no evident clay figures were found; red was used to create a few lines, negative and positive hand stencils, and more than 52 red spots between 5 and 15 cm in diameter on the walls and ceiling of a small vault hidden in the deepest section of the cave where human bones were deposited. From this vast universe of elements, my initial reflections on the interface between orality, images, and text are grounded in Section 7’s black drawings and clay figures because the cave’s best-preserved and most complex panel is located here. Furthermore, as explained below, these drawings were deliberately placed on top of clay figures, particularly with a considerable ballcourt clay relief.

3.2. Section 7

This terrace on the right side of the stream (towards the end of the cave) measures 12 m by 6 m. A layer of charcoal fragments mixed with clay covers the floor, providing evidence of human activity, either to illuminate the space for ritual purposes or to aid in the production process of the figures (Zubieta 2021; Zubieta Calvert et al. 2025). The cave’s ceiling acts as a light-coloured canvas on which the artists made black drawings, and the floor serves as a mud setting upon which figures were modelled (Figure 5)*. In this sense, both layouts face each other and are flanked by the crystalline stream, whose constant sound of running water is interrupted by a large rockfall in the middle of the stream towards the end of the terrace. However, not in all instances where we observed black lines on the ceiling could we identify their shape, as some are fading. Sometimes, even when the pigment concentration is visible, it is smudged around the edges, thus impeding the clear appearance of the shapes and making them less discernible.

Figure 5.

Section 7 shows the relationship between the clay figures below and the black drawing on the ceiling. Please note that on the floor, on the right, is a female figure (S7-7), and the ball court is at her feet (S7-8). (Photo by Leslie F. Zubieta Calvert in 2018; courtesy of: Secretaría de Cultura.-INAH.-MEX.; reproduction authorised by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia de México. Any request to reuse this image needs to be addressed to the aforementioned authority) © 2018 Zubieta INAH research permit 401.1S.3-2018/654.*

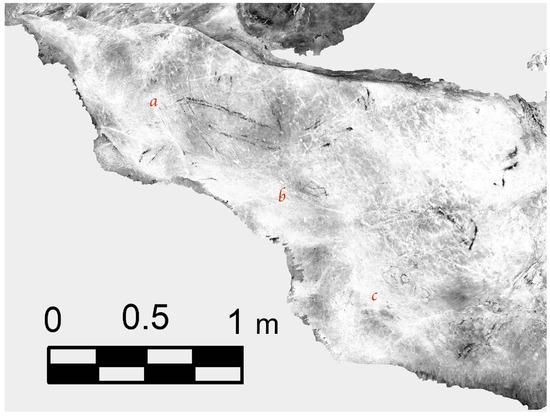

One of the main challenges in recording the drawings and clay figures inside the cave was understanding their spatial distribution clearly, which we could only partially comprehend more thoroughly with photogrammetry in 2019 (Figure 6)*. Nonetheless, the numerous crevices and irregularities of the ceiling topography concealed some of the drawings. Near the latter, we sometimes observed traces of fingerprints made with clay, possibly marks left by the authors. In the detailed description of Section 7 below, those traces of black colour are mentioned, and their position above the clay figures gives a general idea of the complexity of the setting.

Figure 6.

Section 7 orthophotograph showing the fine-line black drawings discussed in this paper on the ceiling and their spatial distribution (Orthophotography created by GIM Geomatics team working under Leslie F. Zubieta Calvert’s project in 2019; courtesy of Secretaría de Cultura.-INAH.-MEX.; reproduction authorised by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia de México. Any request to reuse this image needs to be addressed to the aforementioned authority.) © 2019 Zubieta INAH research permits 401.1S.3-2018/654, 1414.*

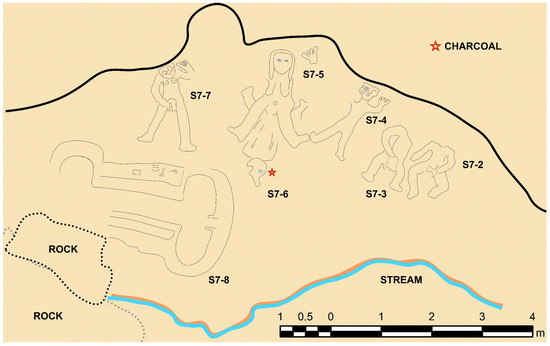

At the beginning of the terrace, vertically positioned, we observed a 15 cm human face relief made of clay on the wall 1.6 m from the floor—the only example of its kind yet discovered. Six human figures in various positions were modelled on this terrace; two are visibly female due to their breasts and exposed vulvas (S7-7 and S7-6; Figure 7). From right to left, the first two human-figure reliefs on the cave’s floor are in a supine position (S7-2 and S7-3; Figure 7). Although headless and eroded, one of their arms touches their genitalia, possibly vulvas, but sex is not conclusive. Two black parallel lines on another edge of the ceiling delineate an incomplete oval, perhaps part of a larger drawing. Next to S7-3, a human figure relief (S7-4; Figure 7) lies closer to the back, with its head resting on the wall; it features a headdress and an ear ornament. Two sets of long parallel black lines appear on the upper wall, possibly part of a larger drawing and a square-like figure (Figure 8a,b)*. Below, almost indistinguishable, is the head of an animal with a circle for an eye and two ears, probably a rabbit, possibly indicating a calendar day (Figure 8c)*6 It is very similar in shape to the head of the jaguar depicted in the black drawing above the ballcourt, as described below.

Figure 7.

Section 7 plan showing the distribution of the clay figures mentioned in this article. Drawing: Leslie F. Zubieta Calvert.

Figure 8.

Panel directly above clay figures S7-3 and S7-4. The letter (a) shows long parallel lines, (b) a square-like shape, and (c) an animal’s head. The image was first processed with the D-Stretch programme to enhance the colours and then transformed into black and white. (Processed image by Leslie F. Zubieta Calvert in 2025; courtesy of: Secretaría de Cultura.-INAH.-MEX.; reproduction authorised by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia de México. Any request to reuse this image needs to be addressed to the aforementioned authority.) © 2025 Zubieta INAH research permits 401.1S.3-2018/654, 1414.*

Next to S7-4, figure S7-5 (Figure 7) is a female mid-relief in a supine position, leaning her torso and head against the back of the wall—almost seated. She wears a headdress that runs down both sides of her face; perhaps these bands signal her long hair. Both arms were plastered against the wall and have disappeared due to gravity, but her left hand remains visible, embedded in the back of the wall close to her head. She has elongated breasts, and from her vagina, an adult-sized anthropomorphic figure S7-6 (Figure 7), wearing a cone-shaped headdress, emerges in a supine position with both arms extended close to the body. His legs extend below the female’s spread legs, and his calves and feet reappear on the other side. Winter et al. (2014, p. 302) proposed that this could be a copulation scene, but it might also be a birth scene—either of a human or mythic being—due to the shape of the breasts, which could signal lactation. A piece of charcoal extracted 2 cm to the right of the head of S7-6 (Figure 7), dated to 1285 ± 15 (UCIAMS #254900; 14C age B.P.)—670–774 cal CE (95–4% probability), indicating the last visits to this particular terrace given its position on the surface.

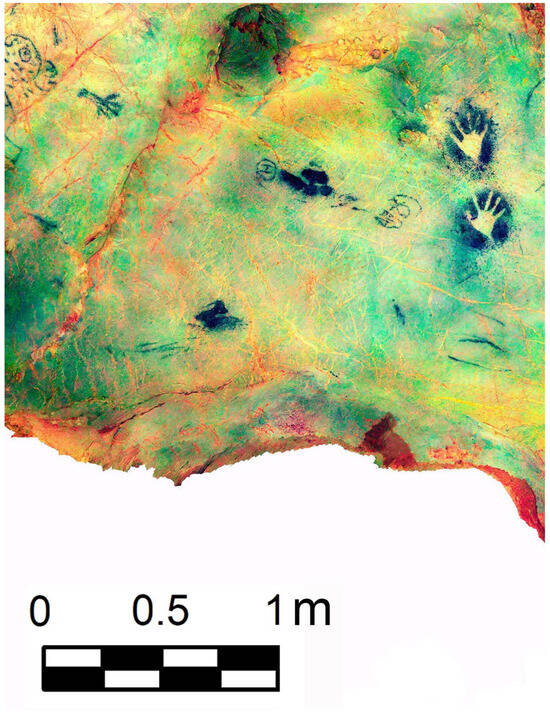

A few metres to the right of the last scene, there is a female mid-relief, S7-7 (Figure 9)*, in a supine position with small breasts and her head resting against the wall. She wears a headdress, possibly a diadem. Her left-hand touches her ear while the other hand touches her accentuated vulva, a recurrent pattern observed in Sections 14, 9, 7, 6, and 5, where female figures depict one hand as if opening the vulva while the other arm points upwards (Zubieta 2021, p. 1181). Directly above S7-7 (Figure 7), we observed two black negative right-hand stencils. Next to the lower one, an image possibly depicts a “face” facing left, from which an infilled rectangular form emerges, and a circle featuring an H-shaped interior design, probably a cartouche (possibly a speech scroll, or sound). Below the “face”, some fingerprints are visible, made with clay. Beneath that, there is another infilled image accompanied by small black lines (Figure 10)*.

Figure 9.

Female mid-relief (S7-7), 1.6 m long and 55 centimetres wide (from the hip), possibly wearing a diadem (Photo by Leslie F. Zubieta Calvert in 2018; courtesy of: Secretaría de Cultura.-INAH.-MEX.; reproduction authorised by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia de México. Any request to reuse this image needs to be addressed to the aforementioned authority.) © 2018 Zubieta INAH research permit 401.1S.3-2018/654.*

Figure 10.

Panel directly on top of S7-7. The image was processed with D-Stretch lab ac to enhance the colours. (Processed image by Leslie F. Zubieta Calvert in 2025; courtesy of: Secretaría de Cultura.-INAH.-MEX.; reproduction authorised by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia de México. Any request to reuse this image needs to be addressed to the aforementioned authority.) © 2025 Zubieta INAH research permit 401.1S.3-2018/654, 1414.*

Thirty centimetres below S7-7, an enigmatic large I-shaped ballcourt high-relief (3.8 m by 2.1 m; S7-8) catches one’s attention (Figure 7 and Figure 11*). The ballcourt and the game are highly significant in Mesoamerican ideology and religion, linked to fertility, sacrifices to the solar cycle, and the ritual practice of the ballgame—either human self-sacrifice or sacrifices involving other beings. Only selected players participated in sacred games to resolve political disputes and ensure the continuity of the lifecycles of plants, animals, and humans (Taladoire 2015). Its rounded corners, aprons, and benches exhibit fine details, such as staircases at the bottom leading down to the playing alley and another exterior staircase leading to the upper cornices of the ballcourt, which are noteworthy. Other details include two small anthropomorphic representations in low relief (12 cm) on the upper structure of the ballcourt and possibly some other low reliefs on the slope of the aprons. The left corner of the ballcourt towards the end of the terrace is destroyed, with a rockfall flanking the ballcourt towards the edge of the stream (Figure 7). Winter (2020, p. 172) recovered an early date from “a damaged and exposed area of the sediment used to construct the ballcourt,” dated to calibrated 197 to 47 BCE. (Beta-527199. Radiocarbon age 2100 ± 30 BP = 150 ± 30 BCE).

Figure 11.

I-shaped ballcourt high-relief (3.8 m × 2.1 m) in Section 7. (Photo by Leslie F. Zubieta Calvert in 2018; courtesy of: Secretaría de Cultura.-INAH.-MEX.; reproduction authorised by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia de México. Any request to reuse this image needs to be addressed to the aforementioned authority.) © 2018 Zubieta INAH research permit 401.1S.3-2018/654.*

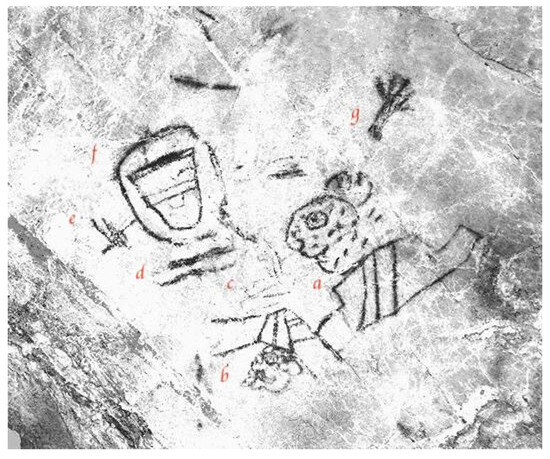

Directly above the ballcourt, we observe a panel comprising a place glyph7: a “hill” sign with diagonal bands and a jaguar’s head with spots8 on top that would specify the name of the place (Figure 12a)*. The base of the hill connects to a linear drawing of a corner of a structure, within which, at the interior vertex, there is a small drawing of a flower or mask (Figure 12b)* and other poorly preserved linear motifs—directly in front of the jaguar head (Figure 12c)*—that we were able to notice after processing the image with the D-Stretch programme (see Harman 2008 for this enhancing tool). Given the position of the place glyph on the ceiling above the ballcourt, it could refer to its location within a specific physical terrain. The combination of the hill and jaguar images might have expressed the artists’ and users’ languages, by means of a phonetic system, probably involving speakers of the Mixe-Zoquean or Zapotecan family (or both), following Campbell and Kaufman (1976, p. 81 Figure 1) and Urcid’s (2005b, p. 5 Figure 1.1) of those languages in Mesoamerica. Nonetheless, it is essential to identify the language first in order to suggest further interpretations.

Figure 12.

Panel directly on top of the ballcourt. The letter (a) depicts a jaguar’s head with spots on top of a hill sign with diagonal bands, (b) a type of structure featuring a small drawing of a mask or flower at the interior vertex, (c) poorly preserved linear motifs, (d) two parallel lines, (e) a small drawing attached to an oval drawing, (f) an oval shape within an internal cup-like figure with parallel internal lines, and (g) a figure with five points. The image was first processed with the D-Stretch programme to enhance the colours and then transformed into black and white. (Processed image by Leslie F. Zubieta Calvert in 2025; courtesy of: Secretaría de Cultura.-INAH.-MEX.; reproduction authorised by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia de México. Any request to reuse this image needs to be addressed to the aforementioned authority.) © 2025 Zubieta INAH research permit 401.1S.3-2018/654, 1414.*

Acknowledging the possibility that the black drawings are related to a writing system suggests that some elements of this imagery reflected the spoken word phonetically. Places named “the mountain/place of the jaguar” are known in the Valley of Oaxaca and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec; however, the geographical location of the ballcourt remains uncertain due to its distinctive architectural features. Hill or mountain logograms with various shapes are common in Mesoamerican picture writing systems (e.g., Maya, Nahua, Zapotec) and on different supports (e.g., ceramics, stone, codices). However, similar square-shaped hills have been found in Huajuapan, Tequixtepec, and the Valley of Oaxaca at sites such as Monte Albán (e.g., Stela 2, Stela 3, Stela 8, Lápida de Bazán), particularly featuring diagonal bands (i.e., Mound J; Caso 1946, p. 134). Winter et al. (2014) mention that the hill glyph (or logogram) has been used in Zapotec iconography since the Late Preclassic period. It was first depicted in Monte Albán during the Pe phase (300–100 BCE) and more regularly during the Nisa phase (100 BCE–200 CE) (Winter 2020, pp. 167, 309). Its occurrence at Cueva del Rey Kong-Oy is the earliest known example in the Sierra Mixe; thus, it confirms the presence of Zapotec ideology and language through macroregional interactions and other still-unknown social and historical processes that will eventually help us understand the cultural significance of this site within a larger region.

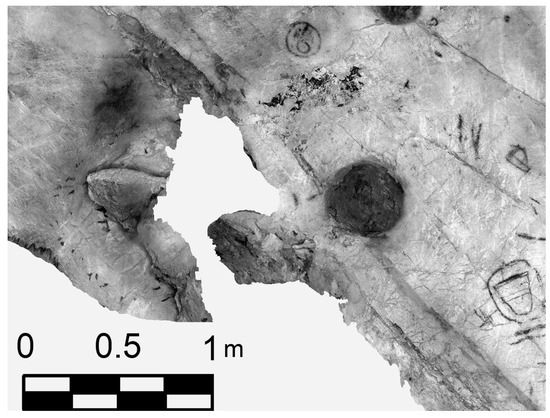

Behind the jaguar’s head is a figure with five points that may represent an incense bundle or a stylised footprint (Figure 12g)*, possibly to indicate direction or movement. An oval drawing or cartouche with an internal cup-like shape with parallel internal lines facing the “hill of the jaguar” perhaps portrays another topographic feature of the landscape (e.g., a mountain or a cave) or another glyph of a place, though with a different orientation (Figure 12f)*. An interesting proposition has been suggested by Marcus Winter et al. as the helmet of a ball game player (Winter et al. 2014, p. 303). In the context of the ballcourt clay relief, it is plausible that a depiction of a helmet might indicate ritual confrontation between different leaders and the eventual victory of one of them. In particular, this possible helmet has a small design attached to it, perhaps suggesting its name (Figure 12e)*. Depictions of helmets are well known from a large repertoire of engravings at Dainzú in the Central Valley of Oaxaca, an important political centre during 200 BCE–200 CE. Still, one example has also been identified in Monte Albán (Urcid 2014). Beneath the oval drawing are two parallel lines, possibly indicating the number ten (Figure 12d)*. Higher up on the ceiling are a P shape, two parallel lines, a circular cartouche with an internal round design, and an infilled diamond shape (Figure 13)*.

Figure 13.

Black drawings above the panel on top of the ballcourt (Figure 12)*. The image was initially processed using the D-Stretch programme to enhance the colours and was later transformed into black and white. (Processed image by Leslie F. Zubieta Calvert in 2025; courtesy of: Secretaría de Cultura.-INAH.-MEX.; reproduction authorised by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia de México. Any request to reuse this image needs to be addressed to the aforementioned authority.) © 2025 Zubieta INAH research permit 401.1S.3-2018/654, 1414.

Challenges arise in equating the black drawings in Section 7 with a canvas to demonstrate an intention for all the elements to form part of a pictographic document. However, the lack of successive superimposition of images on the ceiling and the non-fixed orientation is noteworthy. Although some are now lost due to high humidity, the absence of a profusion of black drawings suggests that these were executed at a single time and deliberately created in black colour. The combination of potentially logosyllabic writing elements, in connection with calendaric glyphs, clay figures, and the initial radiocarbon dates in the cave’s Section 7, reveals that key aspects of Mesoamerican scripts were already present in the Mixe region at least during the Late Classic period (600–900 CE). This is supported by the notable chronological bracket of 607–881 CE, with a 95.4% probability, as determined through systematic dating in Sections 5, 9, 11, 12, 14, and 15 of Cueva del Rey Kong-Oy (Zubieta Calvert et al. 2025, p. 13, Table 6).

4. Discussion

Recognising the mixed use of images and orality in the transmission of knowledge carries profound implications for rock art research in the context of Cueva del Rey Kong-Oy. The most evident implication is that some black drawings, in combination with clay figures, may have served as a graphic medium, and that some drawings expressed words due to their resemblance to Mesoamerican scripts (i.e., Zapotec), to facilitating expression in a narrative alongside the clay figures. In this sense, these drawings can be regarded as a subset of rock art that can be examined both from a linguistic perspective and through the rich interdisciplinary methods that rock art research has developed. However, various assumptions (and limitations) must be addressed.

The first assumption is that the drawings and clay figures were created in tandem to convey specific cultural knowledge. This hypothesis is particularly based on the spatial association between the place glyph and the modelled ballcourt, as one stands in front of the other: the ballcourt on the floor and the black drawing on the cave ceiling. Second, there is no certainty that the earthen figures in this section were created in a single episode. Third, some of the black drawings are fading, and we do not know whether these were all painted at the same time as the clay figures. If created simultaneously, rock paintings alongside the clay figures could have communicated narratives with various levels of meaning related to calendrical data, the fertility of the land and the people, and other recurrent themes in Mesoamerica, such as territoriality (Zubieta 2021). Nonetheless, even if the black drawings were made later, they were produced in close association with the clay figures, particularly evident in the place glyph–ballcourt association. In this case, it is possible that another social group9 entered the cave and appropriated the earthen figures to weave new narratives. Further research and a precise chronological sequence are required to resolve these dilemmas.

In this regard, the absence of comparative dates between the black drawings and the clay figures currently makes it impossible to ascertain whether these elements in Sector 7 were created simultaneously or during different periods by the same or a distinct group (Zubieta Calvert et al. 2025, p. 3). The potential diachronic creation of elements over time, in addition to their meanings, would indicate a place where cultural knowledge was produced, preserved, memorised, and shared through its retelling. In addition, it is conceivable that the female bodies crafted in clay, characterised by prominent vulvas and engaging in childbirth or copulation, along with the ballcourt and fine black-colour lines and drawings, were possibly conveying cultural lineages or creation myths. These elements may have facilitated the consolidation of collective identity and memory, following Maurice Halbwachs (1980, p. 51), which was reinforced with each visit to the cave when individuals gathered within its space.

Despite their unknown age, the paintings in Cueva del Rey Kong-Oy were most likely an extension of an oral-visual knowledge transmission system in the neighbouring territory of the Mixe, as explained earlier. Following this line of discussion, certain aspects of the ritual calendar were possibly depicted as black drawings inside the cave. Although there is scant information about the Mixe’s ancient socio-political organisation (Sousa 2017), Indigenous knowledge and ethnographic work in the Sierra Mixe confirm that calendar cycles and day qualities, essential aspects of the 260-day calendar and maise divination, were and still are in use in some parts of the Ayuuk ja’ay territory, although this practice is rapidly diminishing (Bautista Santaella 2013, p. 89; Duinmeijer 1997, p. 178; Lipp 1991; Münch Galindo 2003; Rojas 2016; Tránsito Leal 2020). This sacred knowledge—and responsibility—is bestowed upon the ritual specialist, the xemabie (the counter of the days), who is consulted for essential tasks in the community, such as predicting the future and giving guidance on selecting the best day to perform particular rituals and sacrifices (Duinmeijer 1997, p. 179; Rojas Martínez Grácida 2017).10 In some areas of the Sierra Mixe, the xemabie is believed to be chosen by Kong-Oy, the mythical hero of the Ayuuk ja’ay, and thus, the xemabie is the only one gifted to contact him (Barabas and Bartolomé 1984; Castillo 2017, p. 148). Perhaps in ancient times, a specialist also bore responsibility for conveying and memorising such knowledges encoded in the drawings and clay figures, thus serving as mnemonic devices (Zubieta 2022b).

The distribution of black drawings in the cave’s Section 7 likely followed similar reasoning and multi-orientation as the iconography depicted in codices and later Colonial documents, such as lienzos or Títulos Primordiales, which helped to legitimise the possession and ownership of territory by Indigenous peoples (see Florescano 2002)11. In this regard, the rock art panel in Section 7 cannot be simplified to the linearity of text mentioned at the start of this paper (Gosden 1992, p. 807; Helskog 1991; Leroi-Gourhan 1982, p. 66). Such a linear approach would require identifying a starting point in the composition and arranging the remaining images in a predefined sequence. Nonetheless, it must have had a non-linear order—also common in Mesoamerica’s writing systems (i.e., Mixtec, Nahua)—recognised as part of the social conventions. Araceli Rojas (2016, p. 473) has suggested that codices were used as mantic systems on which surface ritual specialists casted maise. Thus, perhaps the black drawings in the cave were also used in ways now unintelligible to us, where sight and sound played a part.

Even though many of the paintings are visibly deteriorated, it is still possible to suggest the kinds of stories this interplay might have referred to. Among the Ayuuk ja’ay, an essential distinction has been reported between narratives known as Ap Ayuuk (“grandparents’ stories/ ancient stories”), where spatial and temporal realms are in flux, and rhetorical discourses called kajpën ni Ayuuk or kajpën nimaatyëkde (“people who talk about something, people who have words”)12 that are deployed to convey historical events such as the foundation of a village (Rojas Martínez Grácida 2012). In this sense, the black drawings may have alluded in a rhetorical way to territoriality, which was an essential component and a recurring subject in Mesoamerican cultures. The interplay of media between a two-dimensional image (drawing) and three-dimensional objects (clay reliefs) may have also involved touch; thus, meaning transfer was a conjoint mechanism that included orality, listening, experiencing, and embodying the knowledge conveyed due to a complex literacy system in place in ancient Mesoamerica.

5. Conclusions

Although elucidating the underlying relationship between objects and rock art entanglements can be challenging as an outsider, rock images, as suggested elsewhere, are deeply interrelated with a wide array of material culture in various supports and oral narratives, including songs, storytelling, and sounds (O’Connor et al. 2022; Tuyuka et al. 2022; Zawadzka 2021; Zubieta 2022b). Equating some of the rock art at Cueva del Rey Kong-Oy (or Kondoy) to a parallel form of visual record used as a writing system in pre-Hispanic and Colonial times, although in other media (i.e., animal skin, paperbark or cotton), provides us with new insights regarding the range of themes that black drawings and clay figures might have communicated. Rock paintings alongside unfired clay figures at Cueva del Rey Kong-Oy probably conveyed multiple narratives related to calendrical data, the land’s and peoples’ fertility, and other recurring themes in Mesoamerica.

The similarity between the black drawings and iconography used in other media, such as Mesoamerican codices and lienzos, widens our possibilities for hypothesising about the function and meaning(s) of the black drawings inside the cave, as well as exploring the ontology of this kind of depiction. I propose that some black drawings served as inscriptions, painted rather than incised, which accompanied the clay figures to aid in storytelling. In this sense, the use of inscriptions (two-dimensional) alongside figurative images—in this case, clay figures (three-dimensional)—may have had a structure whose arrangement is now difficult to determine, similar to images made on deerskins and cotton canvases, but on different supports such as stone (see Berrojalbiz 2017, p. 262 for discussion on the Mixteca-Puebla tradition at Ba’cuana).

In this combination of media, viewers in the past recognised the orientation of the black drawings and clay figures, likely reflecting a visual–oral record of a specific territory conveyed through the place glyph “the hill of the jaguar,” which is the only visible element we can purposely explore due to its known occurrence in the Central Valleys of Oaxaca13. The interchangeable use of certain elements, such as the place glyph, in different supports throughout Mesoamerica suggests that the conceptualisation of those “black drawings” in the cave’s Section 7 is more complex in the minds of the creators. Furthermore, it indicates that some images, along with their multiple symbolic layers, may have been interconnected within the Mesoamerican knowledge system across various media, depending on the context. The multiple interpretations of the combined use of images and clay figures may have been linked to ritual practices performed in Section 7, but also in connection with the extensive repertoire of clay figures found in other parts of the cave.

An image, which appears to our Western eyes as one fixed form, has numerous simultaneous associations in Mesoamerican cultures, as shown in Indigenous perspectives and ethnography. Therefore, the interplay between black drawings and clay figures inside the cave suggests a multilayered understanding of the world (Zubieta 2021). This extraordinary opportunity, where modelled unfired clay has survived in the context of the cave, sheds light on the interplay between words, black drawings, and earthen figures in Mesoamerica’s underworld for the first time. It reveals that there was no fundamental ontological distinction between objects and images in the minds of the creators, but a relation established during ritual.

In the interplay of media at Cueva del Rey Kong-Oy, not only were the clay figures perceived as sentient—as described earlier in this paper—but also the images made in black fine-line drawings. In this way, words, images, and objects not only engaged with each other in the subterranean space but also intra-acted, following feminist physicist Karen Barad’s understanding of intra-action as “the mutual constitution of entangled agencies” (Barad 2007, p. 33). This awareness leads to a deeper understanding of the nature of their relationship and how knowledge must have been transmitted, circulated and memorised. It highlights its significance in this region of Mesoamerica beyond text. Lastly, it is through this understanding of the interconnectedness between these elements, which extends beyond the scope of this initial reflection, that our efforts are currently underway to investigate the content of the black drawings, utilising insights from historical and comparative linguistics, ethnography, grammatology, Indigenous knowledges, and epigraphy to propose a methodological framework and address this subset of rock art that is unique to Mesoamerica.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 750706 to undertake research and recording activities in 2018. I appreciate the generous support from Fundación Palarq in Spain (convenio–018649), which provided funding in 2019 for a 3D photogrammetric study of certain cave sections (permits 401.1S.3-2018/654, 977, 1414). Appreciation is extended to the Gerda Henkel Foundation for their support (AZ 20/BE/23) towards the writing time to develop the content of this paper.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

My gratitude goes to David Whitley for inviting me to contribute to this volume. This research was made possible by the permit issued by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia of Mexico (INAH) to PI Leslie F. Zubieta Calvert, the support from Centro INAH Oaxaca, and the essential collaboration and consent of the San Isidro Huayápam community since 2018. I thank the traditional authorities (bienes comunales and cabildo), the caracterizados, the Asamblea General, and local team members of San Isidro Huayápam for their participation in the research activities. I sincerely appreciate everyone in San Isidro who has warmly welcomed me and generously supported this research project from the very beginning; thank you (agradezco sinceramente a todas y a todos en San Isidro que me recibieron con tanto cariño y que apoyaron generosamente el desarrollo de este proyecto de investigación desde el principio; tyoykujujëp). A photographic record of the clay figures and rock art was created in 2018–2019 with the support of INAH’s Archaeological Council research permits (401.1S.3-2018/654, 977, 1414), as well as the laboratory work of the GIM Geomatics team with José Latova at the site to produce the orthographic material in 2019. INAH has authorised the reproduction of Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 (permit 401-3-3196), and any request to reuse these images needs to be addressed to the aforementioned authority. A big thank you to the MDPI ARTS editorial team for their patience in obtaining permission to reproduce the images and for their ongoing communication. I greatly appreciate the comments of two anonymous reviewers who helped clarify and improve some arguments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Cueva del Rey Kong-Oy is a closed-to-the-public cave because of the fragile archaeological evidence inside, located in the land of San Isidro Huayápam. Following San Isidro Huayápam traditional authorities’ request in 2018, Kong-Oy is used here instead of Cong-Hoy. Some people have noted Konk-Oy as a spelling alternative, while others agree that Kondoy is the most ancient version of the name. |

| 2 | Evidence of the manufacturing of figures made from unfired clay in subterranean landscapes is scarce globally. Of particular interest is the preservation of plastic art in the Cantabria-Pyrenees region of Europe, where, for example, two clay bison in high relief, between 16,500–13,500 calibrated years BP (Bégouën et al. 2012), were uncovered in the deepest section of Tuc d’Audoubert cave (See Zubieta 2021, p. 1183). |

| 3 | The exact location will not be disclosed here to protect the site’s integrity. Collaborative efforts between researchers, traditional authorities, and the National Institute of Anthropology and History of Mexico (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, INAH) are underway to formulate the best ways to protect the site. One of the joint resolutions at the end of 2018 has been to restrict access to the site. |

| 4 | “[…] escribían con unos caracteres tan abreviados, que una sola plana expresaban el lugar, sitio, Provincia, año, mes y día, con todos los demás nombres de Dioses, ceremonias y sacrificios, ó victorias que habían celebrado, y tenido, y para esto a los hijos de los Señores y á los que escogían para su Sacerdocio enseñaban, é instruían en su niñez haziendoles decorar aquellos caracteres, y tomar de memoria las historias, y destos mesmos instrumentos he tenido en mis manos, y oydolos explicar á algunos viejos con bastante admiración, y solían poner estos papeles, ó como tablas de Cosmographia pegados á lo largo en las salas de los Señores, por grandeza, y vanidad, preciándose de tratar en sus juntas y visitas de aquellas materias…” (verbatim from Burgoa 1671: Idea de los libros y historias de Oaxaca). |

| 5 | Lienzos, also known as “Mexican pictorial writing”, were cotton sheets procured to replace the use of animal hides (Parmenter 1993, p. 1). |

| 6 | The Mixe, Zapotec, Maya, and Nahua have a calendar day named after the rabbit. |

| 7 | A symbol with pictorial elements standing for well-known places and used in pre-Hispanic times across various supports, such as codices and later in lienzos. |

| 8 | Marcus Winter has suggested that it is a spotted rabbit (Winter 2020, p. 166; Winter et al. 2014, p. 302), although I am inclined to think it is a jaguar due to the shape of the ears. |

| 9 | Based on the evident obliteration of specific clay figures in the cave’s Sections 5 and 9 (e.g., absent heads, a “fresh” patina suggesting recent handling; Figure 4), it has been proposed that the cave might have also been frequented by diverse populations (Zubieta 2021, p. 1178). |

| 10 | Burgoa recorded in Oaxaca, perhaps in the Mixteca region, that every 13 years in a 52-year cycle was associated with a specific cardinal orientation and had certain qualities thought to be beneficial to having children, a good harvest, instigating a war, and even predicting excessive heat (Burgoa 1671, Cap. 25). |

| 11 | These ”pictorial documents”, following Ross Parmenter, also aided the Spaniards in knowing the ancestral territories and lineage of the people who could serve as the tribute collectors of The Crown (Parmenter 1993, p. 2). |

| 12 | Translating and understanding words in the Ayuuk language is complex and can be written in various ways depending on its variants. These words and phrases offer a broad range of possibilities for exploring the sentiment and intricate associations within the Ayuuk ja’ay philosophy. In this regard, Cándido Santibáñez, a Mixe linguist, commented that “Ap” means ancient, old, and “Ayuuk” means mouth or language, so Ap ayuuk can be interpreted as “the history of the Mixe,” “the history of the Mixe language,” or “history of the Mixe nation”: ancient stories. Kajpën ni Ayuuk means “to talk about the history or language of the Mixe,” while käjpen ni maatyëkde expresses a more active and collective sense: “let’s talk and chat” (Santibañez, personal communication, 2025). |

| 13 | In this sense, the corpus of inscriptions we possess is limited for now, and hopefully, other inscriptions will be uncovered in this region over time. |

References

- Ballensky, Tamara. 2012. Secrets of Condoy: Discovering Oaxaca’s ancient mud sculptures. NSS News 70: 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Barabas, Alicia M., and Miguel A. Bartolomé. 1984. El Rey Cong Hoy. Tradición Mesiánica y Privación Social Entre los Mixes de Oaxaca. Oaxaca: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. [Google Scholar]

- Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, Roland. 1973. Elements of Semiology, 1st ed. New York: Hill and Wang. [Google Scholar]

- Bautista Santaella, Juana. 2013. Asunción Cacalotepec: Espiritualidad Mixe en su Territorio y Tiempo Sagrado. Jokyëpajkm: Mëjjintsëkëny Ma y’it Nyaaxwiiny Tyajknaxy. Oaxaca: Proveedora Gráfica de Oaxaca. [Google Scholar]

- Beals, Ralph L. 1945. Ethnology of the Western Mixe. Berkeley: University of California Press, vol. 42. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal Alcántara, Juan Arelí, and Jorge Molina Domínguez. 2021. Anyukojm-Totontepec. Historia y Cultura Mixe. Ciudad de México: Instituto Nacional de los Pueblos Indígenas. [Google Scholar]

- Berrojalbiz, Fernando. 2017. Arte rupestre del sur del Istmo de Tehuantepec, ¿una variante regional del estilo Mixteca-Puebla? In Estilo y Región en el Arte Mesoamericano. Edited by María Isabel Álvarez Icaza and Pablo Escalante Gonzalbo. Ciudad de México: Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, UNAM, pp. 247–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bégouën, Robert, Carole Fritz, and Gilles Tosello. 2012. Parietal Art and Archaeological Context: Activities of the Magdalenians in the Cave of Tuc d’Audoubert, France. In A Companion to Rock Art. Edited by Jo McDonald and Peter Veth. West Sussex: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., pp. 364–80. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, Elizabeth Hill. 2020. Descendants of Aztec Pictography: The Cultural Encyclopedias of Sixteenth-Century Mexico, 1st ed. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, Elizabeth Hill, and Walter D. Mignolo, eds. 1994. Writing Without Words: Alternative Literacies in Mesoamerica and the Andes. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, Carolyn E., and Kim Cox. 2016. The White Shaman Mural: An Enduring Creation Narrative in the Rock Art of the Lower Pecos, 1st ed. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burgoa, Francisco de. 1671. Extraits des: Geográfica Descripción de la Parte Septentrional del Polo Ártico de la América. Historia de la Provincia de Predicadores de Guaxaca. Paris: Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 3508. Available online: https://archive.org/details/MS3508/page/n233 (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- Campbell, Lyle, and Terrence Kaufman. 1976. A Linguistic look at the Olmecs. American Antiquity 41: 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caso, Alfonso. 1946. Calendario y escritura de las antiguas culturas de Monte Albán. In Obras Completas de Miguel Othón de Mendizábal. Ciudad de México: Talleres Gráficos de la Nación, vol. I, pp. 113–45. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, María del Carmen. 2017. Los que van al cerro: Imágenes de la cosmovisión mixe en Oaxaca, México. In Abya Yala Wawgeykuna. Artes, Saberes y Vivencias de Indígenas Americanos. Edited by Beatriz Carrera Maldonado and Zara Ruíz Romero. Zacatecas: Instituto Zacatecano de Cultura “Ramón López Velarde”, pp. 134–51. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1997. Of Grammatology. Corrected. Translated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duinmeijer, Bob. 1997. The Mesoamerican calendar of the Mixes, Oaxaca, Mexico. Yumtzilob 9: 173–205. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery, Kent V., and Joyce Marcus. 2003. The origin of war: New 14C dates from ancient Mexico. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100: 11801–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florescano, Enrique. 2002. El canon memorioso forjado por los Títulos Primordiales. Colonial Latin American Review 11: 138–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, Carlo T. E. 1967. Oldest paintings of the New World. Natural History 76: 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gosden, Chris. 1992. Endemic doubt: Is what we write right? Antiquity 66: 803–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Bravo, Noemí. 2004. Moctúm: Antigua Grandeza de un Pueblo Mixe. Oaxaca: Fondo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. [Google Scholar]

- Grove, David C. 1970. The Olmec paintings of Oxtotitlan cave, Guerrero, Mexico. Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology 6: 2–36. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41263411 (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Gutiérrez, María de la Luz, and Justin Hyland. 2002. Arqueología de la Sierra de San Francisco: Dos Décadas de Investigación del Fenómeno Gran Mural. Ciudad de México: Dirección de Publicaciones del INAH. [Google Scholar]

- Halbwachs, Maurice. 1980. The Collective Memory, 1st ed. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, Jon. 2008. Using Decorrelation Stretch to Enhance Rock Art Images. Available online: https://www.dstretch.com/AlgorithmDescription.html (accessed on 8 February 2010).

- Helskog, Knut. 1991. The word of art, and the art of words. Antiquity 65: 992–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodder, Ian. 1989. This is not an article about material culture as text. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 8: 250–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutson, Scott. 2014. Artefactos prehispánicos de la Sierra Mixe. In Panorama Arqueológico: Dos Oaxacas. Edited by Marcus Winter and Gonzalo Sánchez Santiago. Oaxaca: Centro INAH Oaxaca, CONACULTA, pp. 267–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, Robert T., and Patrick H. Smith. 2008. Mesoamerican literacies: Indigenous writing systems and contemporary possibilities. Reading Research Quarterly 43: 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joralemon, Peter D. 1971. A study of Olmec iconography. Studies in Pre-Columbian Art and Archaeology 7: 1–95. [Google Scholar]

- Justeson, John S., and Terrence Kaufman. 1993. A decipherment of epi-Olmec hieroglyphic writing. Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science) 259: 1703–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, Etsuko. 1976. Apuntes sobre la historia de los mixes de la Zona Alta, Oaxaca, México. 国立民族学博物館研究報告 1: 344–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacadena, Alfonso. 2008. Regional scribal traditions: Methodological implications for the decipherment of Nahuatl writing. The PARI Journal 8: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lacadena García-Gallo, Alfonso. 1995. Las escrituras logosilábicas: El caso maya. Estudios de Historia Social y Economía de América 12: 601–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, Arnaud F. 2012. Three new rock paintings from Oxtotitlán Cave, Guerrero. Mexicon 34: 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Lenssen-Erz, Tilman. 1992. Coherence—A constituent of “scenes” in rock art. The transformation of linguistic analytical models for the study of rock paintings in Namibia. Rock Art Research 9: 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lerma, Félix, Nicté Hernández, and Daniela Peña. 2014. Un acercamiento a la estética del arte rupestre del Valle del Mezquital, México. An approach to the asthetics of rock art from Mezquital Valley, Mexico. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 19: 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroi-Gourhan, André. 1982. The Dawn of European Art: An Introduction to Palaeolithic Cave Painting. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leroi-Gourhan, André. 1993. Gesture and Speech. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David. 1972. The syntax and function of the Giant’s Castle rock paintings. South African Archaeological Bulletin 27: 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David. 1980. Ethnography and iconography: Aspects of southern San thought and art. Man 15: 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipp, Frank J. 1991. The Mixe of Oaxaca. Religion, Ritual, and Healing. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- López Santiago, Noemí, and Verónica B. Barajas Gómez. 2013. Identidad y desarrollo: El caso de la subregión alta mixe de Oaxaca. Península 8: 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markens, Robert, and Marcus Winter. 2014. La tumba 1 de Chuxnabán, Quetzaltepec, Mixes. In Panorama Arqueológico: Dos Oaxacas. Edited by Marcus Winter and Gonzalo Sánchez Santiago. Oaxaca: Centro INAH Oaxaca, CONACULTA, pp. 279–92. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, W. Breen. 1982. Rock art and site environment at Boca de Potrerillos, Nuevo Leon, Mexico. American Indian Rock Art 7/8: 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, W. Breen, Francisco Mendiola, María de la Luz Gutiérrez, and Carlos Viramontes. 2016. Rock art research in Mexico (2010–2014). In Rock Art Studies: News of the World V. Edited by Paul Bahn, Natalie Franklin, Mathias Strecker and Ekaterina Devlet. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 245–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münch Galindo, Guido. 2003. Historia y Cultura de los Mixes. Ciudad de México: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, UNAM. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, Sue, Jane Balme, Mona Oscar, June Oscar, Selina Middleton, Rory Williams, Jimmy Shandley, Robin Dann, Kevin Dann, Ursula K. Frederick, and et al. 2022. Memory and performance: The role of rock art in the Kimberley, Western Australia. In Rock Art and Memory in the Transmission of Cultural Knowledge. Edited by Leslie F. Zubieta. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 147–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudijk, Michel R., and Maarten Jansen. 1998. Tributo y territorio en el Lienzo de Guevea. Cuadernos del Sur: Ciencias Sociales 12: 53–102. [Google Scholar]

- Oudijk, Michel R., and María de los Ángeles Romero Frizzi. 2003. Los títulos primordiales: Un género de tradición Mesoamericana. Del mundo prehispánico al siglo XXI. Relaciones Estudios de Historia y Sociedad XXIV: 19–48. [Google Scholar]

- Pager, Harald L. 1989. The rock paintings of the Upper Brandberg 1: Amis Gorge. In Africa Praehistorica 1. Köln SE: Heinrich-Barth-Institut. Available online: https://hbi.uni-koeln.de/en/books/africa-praehistorica/details/the-rock-paintings-of-the-upper-brandberg-part-i-amis-gorge (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Parmenter, Ross. 1993. The Lienzo of Tulancingo, Oaxaca. An introductory study of a ninth painted sheet from the Coixtlahuaca Valley. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 83: 1–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitrou, Perig. 2011. El papel de ‘Aquel Que Hace Vivir’ en las prácticas sacrificiales de la Sierra Mixe de Oaxaca. In La Noción de Vida en Mesoamérica. Edited by Perig Pitrou, María del Carmen Valverde Valdés and Johannes Neurath. Ciudad de México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Centro de Estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos, pp. 119–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez Castilla, Gustavo A., Francisco Mendiola Galván, W. Breen Murray, and Carlos Viramontes Anzures, eds. 2015. Arte Rupestre de México para el Mundo. Avances y Nuevos Enfoques de la Investigación, Conservación y Difusión de la Herencia Rupestre Mexicana. Tamaulipas: Gobierno del Estado de Tamaulipas. [Google Scholar]

- Rincón Mautner, Carlos A. 2005. The pictographic assemblage from the Colossal Natural Bridge on the Ndaxagua, Coixtlahuaca Basin, Northwestern Mixteca Alta of Oaxaca, Mexico. Ketzcalcalli 2: 2–69. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas Bringas, María. L. 2019. El Sitio de Arte Rupestre Zopiloapam: Memoria de la Ritualidad en un Lugar Sagrado del Istmo Oaxaqueño. Master’s thesis, Historia del Arte, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad de México, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Rivero López, Angélica. 2011. Arqueología de la zona ayuuk (mixe). In Monte Albán en la Encrucijada Regional y Disciplinaria: Memoria de la Quinta Mesa Redonda de Monte Albán. Ciudad de México: INAH, pp. 565–83. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, Araceli. 2016. Casting maise seeds in an Ayöök community: An approach to the study of divination in Mesoamerica. Ancient Mesoamerica 27: 461–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas Martínez Grácida, Araceli. 2012. El Tiempo y la Sabiduría en Poxoyëm. Un Calendario Sagrado Entre los Ayook de Oaxaca. Ph.D. thesis, Universiteit Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas Martínez Grácida, Araceli. 2017. Wintsë’ëkë. El calendario sagrado y los actos de respeto a la tierra entre los ayöök de Oaxaca (México). In El Arte de Pedir: Antropología de Dueños y Suplicantes. Edited by Andrés Dapuez and Florencia Tola. Villa María: Editorial Universitaria Villa María, pp. 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Roman-Rangel, Edgar, Carlos Pallan, Jean Marc Odobez, and Daniel Gatica-Perez. 2011. Analysing ancient Maya glyph collections with contextual shape descriptors. International Journal of Computer Vision 94: 101–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravia Orantes, Mairyam I., and José F. Saravia Orantes. 2020. Retorno a Ik Waynal: Una nueva documentación de las pinturas rupestres de La Cobanerita. In XXXIII Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala. Edited by Bárbara Arroyo, Luis Méndez Salinas and Gloria Ajú Álvarez. Ciudad de Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, pp. 897–908. [Google Scholar]

- Saussure, Ferdinand de, Charles Bally, Albert Sechehaye, and Albert Reidlinger. 1959. Course in General Linguistics. Translated by Wade Baskin. New York: Philosophical Library. [Google Scholar]

- Severi, Carlo. 2015. The Chimera Principle. An Anthropology of Memory and Imagination. Translated by Janet Lloyd. Chicago: HAU Books. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, Lisa. 2016. The testament of Gerónimo Flores, 1660: A Nahuatl-language writing from a Mixe community in colonial Mexico. In Native Wills from the Colonial Americas: Dead Giveaways in a New World. Edited by Jonathan G. Truitt and Mark Z. Christensen. Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press, pp. 180–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, Lisa. 2017. The Woman Who Turned into a Jaguar, and Other Narratives of Native Women in Archives of Colonial Mexico. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taladoire, Eric. 2015. Las aportaciones de los manuscritos pictográficos al estudio del juego de pelota. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 37: 181–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Thompson, Edward H. 1897. Cave of Loltun, Yucatan. Report of explorations by the Museum, 1888-89 and 1890-91. In Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University. Cambridge: Museum, vol. 1, No. 2. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Thompson, J. Eric S. 1965. Maya hieroglyphic writing. In Archaeology of Southern Mesoamerica. Handbook of Middle American Indians, Volumes 2 and 3. Edited by Gordon R. Willey. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 632–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, Christopher. 1991. Material Culture and Text. The Art of Ambiguity. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]