Abstract

This article examines the significant contributions of Helga de Alvear as a gallerist, collector, and patron, a pivotal figure in the evolution of the Spanish and international contemporary art market. Her legacy is particularly notable through the establishment of the Helga de Alvear Museum in the city of Cáceres, intended to share her vast collection of over 3000 works and foster exhibition, research, conservation, and education. The study analyzes her art collection, highlighting its substantial international minimalist art component, contextualizing its development with her personal and professional journey. Furthermore, it explores the institutionalization of her legacy, from the Helga de Alvear Foundation to the creation and evolution of the museum, its innovative architecture and museography, and its impact on Cáceres’s urban landscape.

1. Introduction

This text is framed within the growing academic interest in studying the role of women in the art market, a field that has experienced significant expansion in recent decades. This renewed focus, driven by gender studies, art history, and art market research, seeks to highlight the contributions of specific women as intermediaries in the exhibition, promotion, valuation, and commercialization of artworks and the artists who create them, their recognition by artistic and cultural institutions, and their appreciation by society.

Traditionally relegated to a secondary plane, the contributions of these women have often remained largely invisible, eclipsed by male prominence in this field. Nevertheless, many women gallerists, collectors, and patrons have been fundamental agents in understanding the development of art in our time, the evolution of the artist’s role in society, and the close relationship between the art market and artistic institutions.

In the European context, among the women who have played a fundamental role in the development of the art market from the second half of the 20th century to the present day, especially in creating bridges for internationalization between Spain and the rest of the world and in connecting with emerging markets, the role played by Helga de Alvear, gallerist and collector, is key (Figure 1). A great patron and visionary who was passionate about the art of her time, she was always deeply committed to the promotion and growth of the artists with whom she worked closely, all of whom are recognized by institutions, museums, and art centers worldwide and are present in the most prominent public and private collections. Her work from the last third of the 20th century until her passing in early 2025 has been essential in the development of the structures of the Spanish art market, in its international dissemination, and in the construction of a legacy that transcends national borders.

Figure 1.

Helga de Alvear in her museum. Source: https://www.museohelgadealvear.com/es/, accessed on 5 August 2025.

The figure of Helga de Alvear emerges as a paradigmatic case. Her trajectory exemplifies the multifaceted work of women in the art market and their capacity to transform the artistic landscape. Throughout her career, de Alvear excelled as a gallerist, collector, and patron. Thanks to the establishment of the Helga de Alvear Foundation, the donation of her collection legacy to the Spanish city of Cáceres, and the creation of the Helga de Alvear Museum of Contemporary Art, an example of the most innovative museum architecture, we now have one of the most innovative contemporary art centers globally. Cáceres thus has become a geographical and conceptual nexus for contemporary art between Spain and Portugal.

This article aims to thoroughly analyze Helga de Alvear’s impact on the development of the Spanish contemporary art market and its international projection, focusing on her activities as a gallerist, collector, and patron. In her role as a gallerist, we explore her innovative strategies, international vision, and contribution to the visibility of artists as well as the challenges she faced as a woman in a predominantly masculine environment. We address the cultural and social context in which Helga de Alvear’s career developed, mention the most prominent artists who exhibited in her gallery and are present in her collection as well as key milestones in the gallery’s trajectory that positioned it globally, and acknowledge her work and influence on new generations of collectors and art professionals.

Furthermore, the process of forming her collection, considered one of the most important in Europe, is examined in Section 4. We highlight her predilection for minimalism, which represents a chapter of particular interest in her collection, widely recognized as one of the most outstanding legacies of minimalist artists and artworks worldwide, and which has been the subject of numerous key studies and curatorial proposals for understanding this artistic movement. Additionally, we make special mention of her artistic patronage, her relationship with the Extremadura region, and her contribution to the cultural development of the region with the creation, first of the Visual Arts Center, and now the Helga de Alvear Contemporary Art Museum in Cáceres. We analyze the museum from both an architectural and an exhibition perspective, the dialogue of the museum space with the artwork, especially with the aforementioned minimalist art legacy, as well as the impact the museum has generated on the city of Cáceres and its urban planning.

The figure of Helga de Alvear cannot be understood without reference to her mentor, Juana Mordó, another key woman in the Spanish art market. Mordó, a pioneering gallerist, played a fundamental role in promoting Spanish art during a period of significant political and social transformations. After a period in Paris and Berlin, she arrived in Madrid in the 1940s, adopting an important role in the cultural scene and inaugurating her eponymous gallery in 1964, after having directed the important Biosca gallery. From that moment, Mordó contributed to launching the careers of an entire generation of artists as well as internationally disseminating the Spanish art scene and incorporating important exhibitions by foreign creators. Her vision and keen eye for discovering talent laid the groundwork for the subsequent development of the Helga de Alvear Gallery and the consolidation of its collection.

It is important to note that, in those decades, it was not easy to find women in Spain holding relevant positions in private enterprise, although the cultural context was always more conducive to female professional development (Herstatt 2008; Chagnon-Burke and Toschi 2023). The role Mordó played in the Spanish art market was crucial for the later careers of other women art dealers, such as de Alvear.

In conclusion, this article, fundamentally synthetic and offering a critical and analytical perspective, seeks to highlight the role of Helga de Alvear as an essential figure in the history of contemporary art whose trajectory exemplifies the importance of vision, passion, and generosity in building an enduring artistic legacy.

2. Materials and Methods

This text was written a few months after Helga de Alvear’s passing. A preliminary review of the existing bibliography on the gallerist and collector revealed that there are hardly any academic sources that have analyzed her trajectory and activity, apart from Javier Remedios Lasso’s doctoral thesis (2016). This thesis contains significant primary information contributed by de Alvear herself and many of her closest collaborators, but it has not been a reference for subsequent academic publications.

The lack of academic material on the figure, work, and legacy of Helga de Alvear is notable in a context such as that of research on the Spanish art market, where relevant publications are scarce. This raises the need to delve deeper into the work of Spanish art dealers in the second half of the 20th century, who are key to understanding the development of the second avant-garde movements in the country, and particularly the work of female gallery owners, who are a minority but highly relevant in a professional context in which it was especially difficult for women to develop an independent career.

Therefore, we have primarily relied on numerous curatorial documentary sources, signed by some of the key figures in contemporary Spanish and international artistic curatorship, as well as valuable texts by Helga de Alvear herself. The interviews conducted by de Alvear during the last twenty years of her career have also been highly relevant, especially at the key moments of the inauguration of her Visual Arts Center in 2010 and the museum in 2021. The academic sources that have supported our analysis primarily refer to the work of women in the art market and in collecting, to minimalism and Land Art as structural elements of the collection, and to minimalist architecture and related museography in the analysis we have carried out on the museum and its dialogue with the city and with Helga de Alvear’s legacy.

The literature review, the testimonies provided by Helga herself, and, above all, the curatorial material derived from the exhibitions of the collection held in recent years allowed us to pose several research questions on which we have based our analysis:

- Q1: To what extent did the Helga de Alvear collection, particularly its substantial international minimalist art component, shape and reflect the key international avant-garde movements and evolving market structures in contemporary art from the late 20th to the early 21st centuries?

- Q2: How does conceptual art, with a particular emphasis on minimalism, manifest within the Helga de Alvear collection, and what is the nature of its interaction and dialogue with other prevalent artistic styles and trends, such as surrealist inclinations and Land Art, in shaping the collection’s overall coherence and curatorial approach?

- Q3: In what ways do the innovative architectural design and museographic strategies of the Helga de Alvear Museum engage in a dialogue with the art collection, particularly with its minimalist legacy, to create specific experiential zones and influence the viewer’s perception and epistemological journey within the exhibition space?

The questions posed are based not only on the initial approach to reference analysis, but also on the objectives toward which our study is directed, which allows us to propose the following hypothesis:

The strategic institutionalization of Helga de Alvear’s extensive art collection, characterized by a substantial international minimalist component and housed within an innovatively designed museum with distinctive museographic principles, has demonstrably elevated the discourse and accessibility of contemporary art, thereby solidifying her pivotal role in the evolution of the Spanish and international art market at the turn of the 21st century.

3. Origins and Immersion in the Art Market

Helga Müller Schätzel, born in 1936 in Kirn, Germany, in the Rhineland-Palatinate region, completed her studies at Salem School, located on Lake Constance, and in Lausanne and Geneva, Switzerland. Subsequently, she furthered her education in the United Kingdom and France, finally settling in Spain.

On the banks of the Nahe River, near her hometown, she spent many moments of her childhood playing with hard stones from nearby deposits and from stone-carving industries, whose remnants, thrown into the river, had been worn down and eroded by the current.

Many art theorists (Rodríguez 2013; Remedios Lasso 2016; Borja-Villel 2022; Guardiola 2022; Kuo 2022) mention that Helga’s interest in materiality—in the texture, weight, volume, and tactility of objects and materials—stemmed from that childhood pleasure of collecting quartz or lapis lazuli stones by the river, touching and observing them, and the attention to detail she put into collecting and classifying them, which she always found fascinating. The lack of formal training in art history was compensated in those early years by the aesthetic appreciation of materials through those stones, which, years later, would lead her to appreciate abstract art for that materiality that, as an adult, she would seek in galleries and museums. As she herself indicated (Rodríguez 2013, p. 18), abstract art never seemed strange to her; her approach to abstraction felt like a new viewpoint from the beginning and inevitably reminded her of her childhood relationship with hard stones. This focus on materiality is fundamental to understanding her collection, especially the significant legacy of minimalist art and the works by artists associated with Land Art currently displayed in her museum.

In numerous interviews (Canal Extremadura 2024; Remedios Lasso 2016; Feria ARCO 2015; Alvear 2011)1, Helga de Alvear recalled that, as a young woman, she did not wish to pursue formal studies but rather chose to learn languages, which led her to travel and envision a future beyond Germany. Indeed, travel would later become a constant in her professional life: journeys to art fairs and international exhibitions across the globe, often accompanied by her close friend and collaborator, curator and art critic José María Viñuela (Alvear 2022). Together, they shared over 40 years of passion for art, from the Venice Biennale to Documenta in Kassel, from Art Basel to Frieze, traversing Paris, Miami, Cologne, visiting artists’ studios, institutional exhibitions, major art fairs, and attending musical and operatic evenings. This ongoing dialogue and frequent exposure to major exhibitions, galleries, fairs, and museums endowed Helga with an advanced artistic perspective and an exceptional ability to identify emerging global artists at an early stage—artists she would presciently support through her gallery and collection (Remedios Lasso 2016).

Her trip to Spain in 1957, aimed at adding Spanish to the languages she already spoke, marked a turning point in her life, both personally and professionally. Her marriage to architect Jaime de Alvear in 1959 enabled her to settle permanently in Spain, where she became acquainted with local museums and the Spanish art scene during a period when artistic avant-gardes were beginning to emerge. She continued to travel across Europe and came into contact with Spanish abstract artists of the late 1950s and early 1960s. She witnessed their relationships with the few, but highly active and influential, art galleries of the time, which played a crucial role in the development of the avant-garde movement (Gómez Álvarez 1998; Torre 2004; Remedios Lasso 2016; Hernando González 2024).

The cultural transformations that took place in Francoist Spain during the 1950s and 1960s were mirrored in the arts, through the development and evolution of avant-garde groups that—despite the turbulent times and controversy they provoked in both contemporary and later art criticism—proved to be catalysts in the Spanish art scene (Hoag 2023). The writings of art critic Vicente Aguilera Cerni (1973) remain instrumental in understanding the significance of groups like El Paso and Dau al Set in promoting not only new aesthetic approaches but also ethical, moral, and social perspectives (Gómez Álvarez 1998). The members of El Paso held their first exhibition in Madrid at the Buchholz Gallery in April 1957, demonstrating that, in the face of institutional inertia under Franco, it was private initiatives—galleries such as Buchholz, Biosca, and Parés—that championed new languages aligning Spanish art with international avant-gardes. Soon thereafter, Juana Mordó would join this effort, including many of these artists in her gallery’s program. The initial success of these exhibitions prompted institutional awareness and support for international showcases of these new languages, such as New Spanish Painting and Sculpture at MoMA and Before Picasso, After Miró at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, both in 1960. These exhibitions presented a version of Spanish culture that was exportable and on par with other international avant-gardes, such as European informalism and American Abstract Expressionism. Simultaneously, a degree of cultural permeability was achieved in an otherwise hermetic Spain through exhibitions like La Nueva Pintura Americana, inaugurated in July 1958 at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Madrid, and Arte Actual USA at the Casón del Buen Retiro in Madrid in 1964, with a catalogue essay by Zóbel (Gómez Álvarez 1998; Torre 2004; Remedios Lasso 2016; Hoag 2023).

The arrival in Spain of the Spanish–Filipino artist and collector Fernando Zóbel, and his close relationship with certain artists from these groups—particularly Gustavo Torner and Gerardo Rueda—culminated in the 1966 founding of the Museo de Arte Abstracto in Cuenca. This museum would showcase Zóbel’s significant collection of works by artists of his generation and become one of the most original institutions in the Spanish museum landscape, where the participation of the artists themselves was essential2. Always present alongside them was their gallerist, Juana Mordó, with whom Rueda, Torner, Zóbel, and other members of El Paso had been exhibiting since 1964 (Torre 2004; Hernando González 2024). It was at the Cuenca museum, thanks to Gustavo Torner, that Helga de Alvear met Mordó in 1967—the year she made her first purchase as a collector, a painting by Fernando Zóbel, paid for in installments, as would be the case for nearly all the works in her vast collection thereafter. This contact with the artists of Cuenca and El Paso, as well as with the gallerist, marked a pivotal moment in her life, which would gradually become more committed to art over the following decade.

We cannot consider Helga de Alvear a wealthy person, but rather a middle-class woman who dedicated part of her savings to the creation of a modest art collection and who later, through partnership with the gallery owner Juana Mordó, had access to many other art works through her gallery.

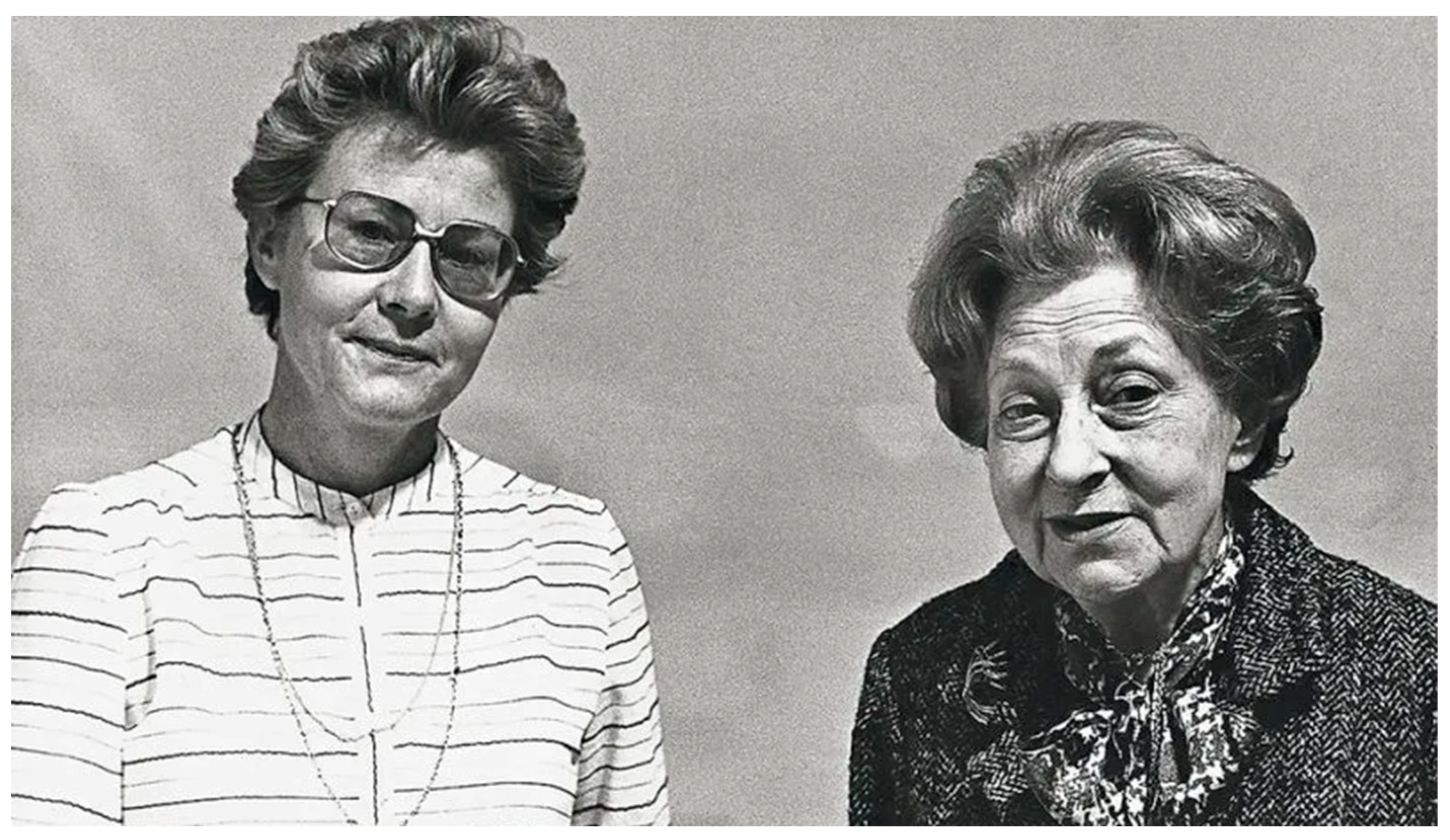

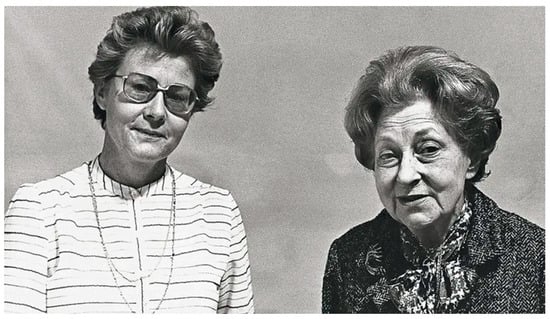

Between 1979 and 1980, Alvear and Mordó developed a relationship that extended beyond friendship (Figure 2): at a time of serious financial difficulties for the gallery, Helga offered to acquire 49% of its shares, becoming Mordó’s business partner as well as a client. In 1980, she began managing the gallery alongside its founder, taking over as director in 1984 after Mordó’s death (Remedios Lasso 2016).

Figure 2.

Helga de Alvear and Juana Mordó in the early 80s. Source: https://www.museohelgadealvear.com/es/, accessed on 5 August 2025.

Those four years were formative—not only in terms of gallery management but also in how she approached and related to artists—and she deepened her knowledge of the international art scene through participation in renowned art fairs such as Art Basel, FIAC in Paris, and the Cologne Art Fair. Juana Mordó’s vision and commitment made her one of the pioneering gallerists to support the creation of ARCO in 1982, Madrid’s contemporary art fair that would go on to become an international benchmark. Helga de Alvear was at her side during this crucial process for the development and internationalization of Spain’s art market (Pellicari 2024; Remedios Lasso 2016). Over time, de Alvear assumed an increasingly prominent role at the Juana Mordó Gallery, becoming not only a client but also a fundamental pillar of financial support. Following Mordó’s death in 1984, she took over the business, continuing her mentor’s legacy and model for ten years—artistically, managerially, and especially in maintaining the gallery’s international presence. Her successful management quickly led her to represent the gallery at major fairs, eventually being invited to join the selection committees in Basel and Cologne. Artists of great international renown, previously little known in Spain, joined the gallery during this period, including Robert Motherwell, John Baldessari, and Nam June Paik (Hernando González 2024; Chang Park 2024; Pellicari 2024; Remedios Lasso 2016).

By the 1990s, the role of women in the leadership of the Spanish art market was already consolidated. The example of pioneers like Juana Mordó had paved the way for the emergence of other important women, such as Soledad Lorenzo, Nieves Fernández, and Elvira González, who, starting in the late 1960s, opened galleries that would reshape the Spanish market. Many of them are still active, even in their second generation. In the final decades of Franco’s regime, the role of women leading Spanish contemporary art was decisive, and it was in this context that Helga developed her first steps alongside Mordó and later with her personal project (Hernando González 2024; Pellicari 2024; Remedios Lasso 2016).

In 1995, Helga de Alvear decided to embark on a new chapter in her career by opening her own gallery bearing her name in a spacious venue of over 900 square meters adjacent to the Museo Sofía in Madrid, thus contributing to the creation of a neighborhood that would become recognized in Madrid for its connection with contemporary art, to which numerous other art galleries and independent creative spaces would be added. This project marked a turning point in her trajectory, as she committed to highly international contemporary art with a special focus on photography, video, and installation—disciplines that were still relatively unknown in Spain at the time. The Helga de Alvear Gallery quickly established itself as one of the most prestigious and long-standing in the Spanish art scene, earning significant international recognition (Herstatt 2008; Bozicnik 2011; Remedios Lasso 2016; Chagnon-Burke and Toschi 2023; Chang Park 2024).

In addition to incorporating prominent European artists such as Georg Baselitz and Anselm Kiefer and forging relationships with galleries such as Julien Levy and Marlborough, Helga developed an important network within the Portuguese art market, facilitated in part by Cáceres’s proximity to the Spanish–Portuguese border. She maintained connections with gallerists (such as Dulce D’Agro and Galeria Quadrum in Lisbon, with whom she had ties dating back to the Juana Mordó years, as well as Filomena Soares, Mario Sequeira, and Judite da Cruz) and collectors (notably José Lima). She also developed connections in the Latin American market (notably with the Mexican galleries Labor and Parque), bringing into her collection artists from these regions, such as the Portuguese José Pedro Croft, Helena Almeida, Julião Sarmento, Carlos Bunga, and Gil Heitor Cortesão as well as Latin American artists Tomás Saraceno, Doris Salcedo, Ernesto Neto, and Carlos Nunes, among many others (Remedios Lasso 2016; Chang Park 2024; Duarte 2020). The gallery distinguished itself through the richness of its holdings, the diversity of approaches adopted by its artists, and their varied origins, with a clear commitment to the most contemporary artistic trends.

Beyond the conceptual movements of the second half of the 20th century, the gallery embraced the Young British Artists, including Damien Hirst, Douglas Gordon, and Rachel Whiteread, and socially and politically engaged artists such as Ai Weiwei, Santiago Sierra, Jason Rhoades, and James Turrell, all of whom used innovative materials and advanced technologies to address themes such as identity, human interaction, globalization, and alienation. Large-format photography, site-specific installations, and the use of light and technology became hallmarks of the gallery’s program (Remedios Lasso 2016).

Her work as a gallerist was recognized with numerous awards and honors, including the Gold Medal for Merit in the Fine Arts, awarded by the Spanish Ministry of Culture in 2008; the Cross of the Order of Civil Merit (Bundesverdienstkreuz am Bande), conferred by the Federal Republic of Germany in 2014; and the International Medal for the Arts from the Community of Madrid (Spain) in 2020, highlighting her fundamental role in the development of the artistic ecosystem both in Spain and internationally.

4. Helga de Alvear, Collector

4.1. First Steps

Since that first acquisition of a work by Fernando Zóbel in 1967—paid in installments, as was the case with most of the works that would later join her collection—Helga de Alvear’s approach to contemporary art as a gallerist never lost sight of her collector’s perspective (Figure 3). For her, the appreciation of a work of art beyond its commercial value always came first, and this influenced the gallery’s activity, her relationships with the artists she represented, and the formation and evolution of her collection (Alvear 2022; Martínez 2016; Remedios Lasso 2016). Her legacy has been recognized as one of the most complete, diverse, and representative European collections of contemporary art by numerous prestigious international curators (Borja-Villel 2022; Kuo 2022; Rodríguez Marcos and Zabalbeascoa 2018; Martínez 2016; Mesquida and Ribeiro 2016).

Figure 3.

Helga de Alvear amid artworks from her collection. Source: https://exitmedia.net/destacado-semana/inauguracion-del-museo-helga-de-alvear/, accessed on 5 August 2025.

Helga de Alvear’s art collection is highly diverse, encompassing early historical avant-gardes through to the trends of the second half of the twentieth century and the early twenty-first century. In her early years as a collector in the late 1960s, acquiring recognized artworks was a challenging and costly task, but she managed to obtain pieces by twentieth-century masters—whether by chance, by being in the right place at the right time, or through significant investment. The initial influence of Juana Mordó explains the large number of works from Spanish informalism and abstraction by prominent artists from the 1950s to the 1980s, which led her to develop a preference for conceptual art and minimalism. After Mordó’s death in 1984, Helga de Alvear began to develop her own identity within the art market, opening up to international trends and giving her collection a distinctive coherence amid the variety of languages and forms of expression it contains.

From 1980 onward, thanks to her intense activity as a gallerist—first with Juana Mordó and later independently—and her contribution to stimulating local production and founding the ARCO fair in 1982, her collection grew into the significant artistic corpus that would eventually form the basis for her museum. Her collection was frequently exhibited in Spain and abroad prior to being housed in the museum, one example being the exhibition Fora da Ordem at the Pinacoteca of São Paulo, Brazil. As the curators noted in the catalogue (Mesquida and Ribeiro 2016), despite the stylistic and geographic variety of its contents, the collection is characterized by the juxtaposition of two art-historical tendencies often seen as antagonistic. On one hand are works of surrealist inclination and strong imaginative character, featuring artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Cindy Sherman, Franz Ackermann, and Marcel Dzama. On the other are artists and works rooted in geometric language, with serial, simple, self-referential forms associated with constructive movements, hard-edge painting, American minimalism, European post-minimalism, and sculpture linked to Land Art. This side of the collection—clearly tied to the collector’s sensibility for materiality and texture—has been the subject of significant curatorial analysis and exhibitions and is the focus of our study.

As she often remarked (Rodríguez 2013; Alvear 2011; Alvear 2022), Helga collected on her own initiative and out of a desire to surround herself with the kind of art that resonated with her. She disliked being guided by curators or critics, trusting instead in her own intuition, instincts, and research. Nevertheless, she always surrounded herself with outstanding artistic directors, both at her gallery and throughout her development as a collector, who she listened to and observed closely: Armando Montesinos, Carlos Urroz, Manuel Borja-Villel, as well as Udo Kittelmann and Sandra Guimarães in her museum. Yet, it was art critic and curator José María Viñuela who had the most decisive influence on her and who best contextualized the various aspects of her collection in its ultimate transformation into a museum.

Her support for the ARCO fair; the promotion of private, corporate, and institutional collecting; the improvement of working conditions for gallerists and professionals; and the protection of artists was always substantial and unwavering. She was consistently committed to strengthening the Spanish art market and promoting its international reach as well as safeguarding the structures that underpin it. For this reason, she especially supported the ARCO fair during periods of crisis—particularly when Carlos Urroz took over its direction during a challenging time. He had been a trusted professional for Helga since his years as artistic director of her gallery (Rodríguez 2013; Alvear 2011).

The relationship between Helga de Alvear and José María Viñuela was one of deep friendship and collaboration (Alvear 2022). Viñuela became Helga de Alvear’s right-hand man and most trusted associate, and together they worked on the creation and development of the Helga de Alvear Museum of Contemporary Art. Viñuela was a trustee of the Helga de Alvear Foundation, curator of the collection, and was responsible for the museum’s museography and served as general curator for its inaugural events until his death in 2022. The full catalogue of the museum published that same year was dedicated to Viñuela and his central role in the conception, development, and musealization of Helga de Alvear’s collection, as well as to his decades-long role as friend, confidant, and close collaborator. The gallerist and collector’s essay in the catalogue bears witness to this (Alvear 2022).

4.2. Approach to Abstraction, Minimalism, and Land Art

On a theoretical level, minimalism has been a topic of intense debate, and Viñuela’s interpretation of it within Helga de Alvear’s collection is no exception. In the catalogue for the exhibition La perspectiva esencial, which highlighted this artistic tendency as a fundamental part of the collection, the author noted that “Helga de Alvear’s time was the era of conceptual art, of minimalism, and of all the enlightening currents of our time” (Viñuela 2018, pp. 29–30).

One of the earliest approaches to minimalism in Spain took place in the exhibition Minimal, held at the Juan March Foundation in 1981 (Tuchman 1981), featuring the most representative artists of the movement, many of whom had already begun to attract Helga de Alvear’s attention and are now present in her collection. The catalogue essay by art critic and historian Phyllis Tuchman offers an in-depth analysis of Minimal Art, tracing its evolution from the 1960s through the early 1980s. It notes the influence of earlier avant-gardes like Russian Constructivism and explores the impact of the movement’s first exhibitions in the late 1960s on art criticism—highlighting writings by Richard Wollheim and Barbara Rose—as well as the productive exchanges between critics and artists, such as Lucy Lippard (1997) and Sol LeWitt, who co-founded Printed Matter in 1976. Lippard’s essay “Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972” (1968) was pivotal in documenting the evolution of conceptual art practices during a time of significant social, political, and cultural change. Her critique of minimalism as reductive and solemn, in contrast to the imaginative and eccentric tendencies of other conceptual practices, also served to define the specific attributes of minimalism within the broader field.

Among the various branches of conceptual art, minimalism was, as Viñuela (2018, p. 29) suggests, the most rigorous, complex, and sophisticated—and perhaps the most difficult to define. Artists such as Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, and Robert Morris pioneered this style, exploring geometric, monochromatic forms devoid of ornamentation using industrial materials and serial production techniques. Their work also incorporated traditional and natural materials, which were decontextualized within the exhibition space. Although these artists rejected the notion of belonging to a unified “movement,” they shared key principles such as conceptual clarity and the viewer’s interaction with the work, aiming for a direct and immediate aesthetic experience. It is worth recalling, as Rodríguez Marcos and Zabalbeascoa (2018) emphasize, that the term “minimalism” was initially contentious, with figures like Donald Judd rejecting the label outright. Judd argued that the work was not representative of a group or a cohesive movement. Early on, terms such as “primary structures,” “specific objects,” or “ABC art” were also used. Ultimately, it was Richard Wollheim’s 1965 coining of “Minimal Art” that endured.

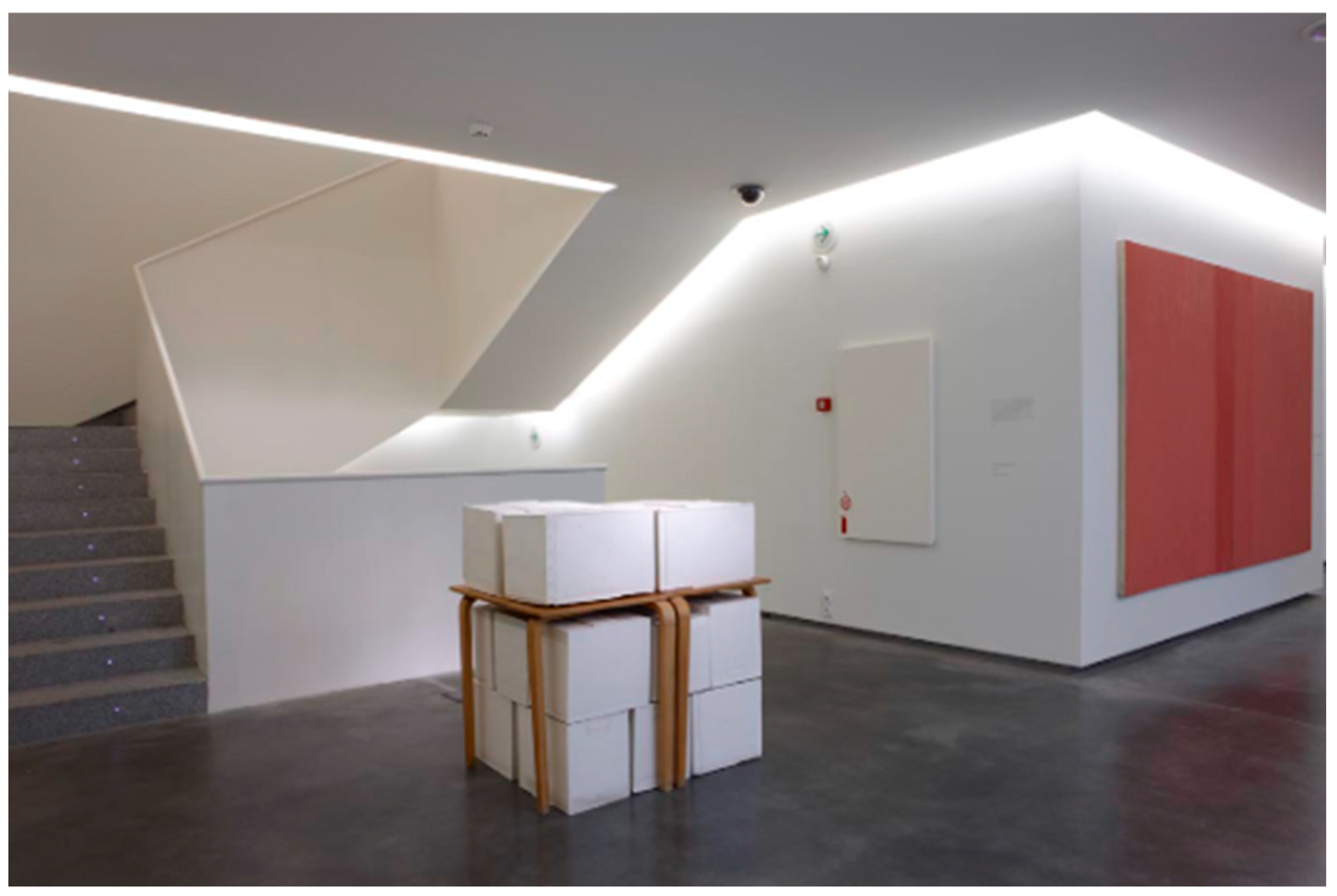

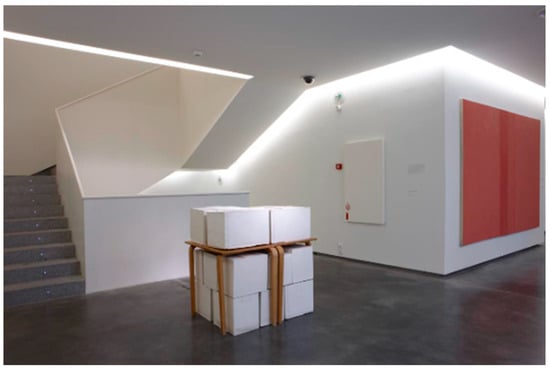

Minimalist works—sculptures and paintings alike—were designed to be apprehended quickly, prioritizing visual perception and reflection. Within Helga de Alvear’s collection, both traditional and ephemeral materials used by artists like Long and Andre coexist with the technological and industrial media employed by Flavin and Judd. As Rodríguez Marcos and Zabalbeascoa (2018) note, and as Tuchman (1981) documented, minimalist artists posed new questions regarding the relationship between artistic production and manual effort—an issue that had been evolving since Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades and Ad Reinhardt’s monochrome paintings. Dan Flavin, for example, declared it essential not to dirty one’s hands while creating art, asserting the primacy of thought. Similarly, Sol LeWitt promoted the idea of art as concept. Minimalist materials were used literally; they were neither camouflaged nor manipulated to appear as something else, nor were they expected to represent anything other than themselves. There was no transition from the literal to the metaphorical. Thus, the objecthood and material presence of the artworks—free from narrative, whether figurative or abstract—would define their exhibition format, the nature of their interaction with the public, and the dialogue they generated. These elements are central to how the Helga de Alvear collection is presented in her museum (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Exhibition Márgenes de silencio, 2021. Source: https://www.museohelgadealvear.com/es/, accessed on 5 August 2025.

According to Michael Fried, minimalism challenges the traditional foundations of art through a “theatricality” that shifts focus from the object to the viewer and the space they both inhabit (Fried 1998). As LeWitt observed in his Paragraphs on Conceptual Art (LeWitt 1967), and as Tuchman (1981) later recalled at the Fundación Juan March, the viewer should spend more time reflecting on the artwork than contemplating it, since conceptual art is designed to engage the mind more than the emotions. Works by Judd, Flavin, Andre, and Sandback in the collection embody this tension between physical presence and viewer experience.

4.3. Materiality and Perception: Theoretical Keys to Minimalism in the Helga de Alvear Collection

In the exhibition La perspectiva esencial: Minimalismos en la colección Helga de Alvear, Viñuela (2018) highlights how certain works and artists in the collection emphasize process, duration, action, and chance—providing, through notions such as objectivity, objecthood, and perception, opportunities for collaboration associated with “participatory minimalism” or relational aesthetics. For Fried, minimalist works lack the “absorptive presence” of modern art; instead, they are objects whose significance arises from being experienced, thus acquiring a theatrical quality (Fried 1998). Rather than discrediting the minimalist proposal, this critique reveals its novelty: the shift of meaning from the object to the aesthetic event. Battcock (1995) adds that minimalism operates as a reaction to Abstract Expressionism, removing gestural subjectivity and embracing industrial and repetitive logic. Carl Andre’s metal plate floor configurations, like the work ALTOZANO (2002) in the museum, invite a physical experience of art: one does not simply contemplate these works; one walks on them. This processual dimension is essential for understanding the ontology of minimalism as a situated, embodied, and temporal practice.

In line with these reflections, Botha (2017) proposes a more systematic theory of minimalism, emphasizing its tension between formal simplicity and perceptual complexity. In his theoretical framework, minimalism is not a reduction but an intensification of perceptual awareness. Artists such as Fred Sandback, also represented in the collection with a number of drawings and with the installation UNTITLED (Sculptural study, two-part vertical construction) from 1976, exemplify this logic: his taut thread interventions barely alter physical space but radically reconfigure perceptual space. The “void” between the threads is not absence, but the invisible structure of meaning.

This focus on materiality—on the primary, the weight, the density, the tactility, and the scale—runs as a common thread through the Helga de Alvear collection. As Kuo (2022) notes, this material sensitivity contrasts with the “seemingly light and hypertrophic expansion of collections” often characteristic of the 21st century. Thus, the collection distances itself from the idea of the artwork as fetish or commodity, instead exploring “the alterity of all subjects and objects.”

Contrary to the spectacular nature of major collections, Helga de Alvear’s is built from “small conquests in the geography of meaning” (Guardiola 2022). It is not a senseless accumulation, but a “zone of permanent activity, a constellation of meaning in process.” In the words of Chus Martínez, quoted by Guardiola (2022, p. 86), the collection is “a supergroup; a term chosen for its productive absurdity and playfulness, its desire to live in common, while avoiding any single sentiment or fixed notion of what culture must be in the future.”

In this context, minimalism in the Helga de Alvear collection is not understood merely as an aesthetic trend but as a means of exploring the relationship between object, space, and viewer. As Borja-Villel (2022) asserts, “contemporary art cannot be understood without the figure of the collector.” In Helga de Alvear’s case, her collection is “a cabinet of curiosities, a dynamic archive, and an assemblage of fragments of a loving discourse” (Guardiola 2022). Ultimately, it is a way of “being in the world.”

Beyond terminological debates, Rodríguez Marcos and Zabalbeascoa (2018) identify several general features of minimalism: abstraction, elementary geometry, austerity, monochromy, and repetition. A minimalist work is defined by its simplicity, rectilinear and regular geometric forms, lack of ornamentation, and absence of compositional effects. It is art that, in Judd’s words, focuses on “specific objects,” works that “are not signs of anything and have no reference other than themselves,” as the series UNTITLED (1991, 1992, 1993) by Donald Judd exemplifies. As André Malraux wrote, “absolutely free art does not result in a painting or sculpture but in a pure object.”

4.4. Minimalism and Museography: A Curatorial Challenge

The figure of the collector has become a key tastemaker in contemporary art, shaping how art history is perceived and transmitted. The inclusion of an artist in a public or private collection can launch their career, associating notions of quality with ownership. This phenomenon has transformed museographic approaches, shifting the art experience from passive viewing to a journey informed by the collector’s vision. Collections such as Helga de Alvear’s represent an alternative perspective, centered on the “dark matter” of things, beyond traditional ocular-centric collecting. This focus on the persistence of matter challenges the dematerialization of art and offers a kind of perceptual “reset” for the viewer (Kuo 2022).

As Borja-Villel (2022) notes, among the numerous exhibitions of private collections in Spain during the late 1980s and early 1990s, the legacy of Italian collector Giuseppe Panza di Biumo at the Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in 1989 marked a turning point in the museographic approach to conceptual, minimalist, and post-minimalist art. The exhibition’s impact and critical acclaim paralleled a shift in public perception of these artistic languages.

Moreover, the presence of minimalism in the Helga de Alvear Museum is not only quantitative but also represents a curatorial challenge. As one text accompanying the museum’s documentation states, the collection’s museography is not organized chronologically or by schools, but by spatial, conceptual, and material relationships. This logic not only encourages dialogue between works of different origins, but also allows minimalism to be fully activated in its experiential dimension.

The experience of contemporary art, particularly in a collection like Helga de Alvear’s, moves away from passive perception and becomes a unique epistemological and aesthetic journey (Guardiola 2022). In a digital world saturated with information, where algorithms shape experience, the collection introduces chance and spontaneity as organizing principles of meaning. Helga de Alvear sees art as a medium for understanding our time and ourselves, developing languages that explain the world beyond its surface.

From the viewer’s perspective, art functions as a perceptual “reset,” both epistemologically and optically, especially in a “neo-baroque” and media-saturated society. As Guardiola (2022) states, some works in the collection invite a “secular kenosis”—an emptying of the self to become receptive to the work—where images not only appear but also disappear. This approach enables a reinterpretation of artworks, even by established artists, offering a more discreet and surprising perspective outside the fetishization of genius.

The placement of works by Andre, Flavin, or Sandback within the museum space does not seek to emphasize a historical narrative, but to create experiential zones, as proposed in minimalist manifestos and practices. Here, the museum is not a neutral container but an expanded field of perceptual interaction, in which the viewer, as Botha (2017) states, “is constitutive of the work’s meaning.”

This approach parallels Marzona’s view that minimalism is inseparable from the space it occupies: its forms have no “inner meaning” but acquire significance through spatial context (Marzona 2004). The museum’s architectural design—with its expansive volumes, bare walls, and controlled lighting—provides optimal conditions for such spatial activation.

5. The Museum

5.1. Encounter in Cáceres

Just as artist Gustavo Torner played a decisive role in the creation of the Museo de Arte Abstracto in 1966 when Fernando Zóbel sought a home for his collection, for Helga de Alvear, it was her friend and confidant José María Viñuela who played a pivotal role in selecting Cáceres as the site for what would first become the Centro de Artes Visuales and later the museum bearing her name. Viñuela, a native of Extremadura, had led the exhibitions department at the Madrid Municipal Museum, served as cultural conservator for the Bank of Spain, and was a member of the European Central Bank’s Cultural Committee. His close ties to contemporary art in Extremadura were instrumental in promoting Cáceres’s development in this field in the early 2000s (Remedios Lasso 2016).

Helga de Alvear had long intended to donate her collection to a city that could provide a suitable venue and demonstrate a commitment to its maintenance and cultural activation. Her inspiration was the Kunstmuseum in Wolfsburg, a northern German city of about 120,000 residents near the Volkswagen factory. Since its founding in 1994, that museum had become a cultural emblem for the city, raising its international profile through contemporary art.

The search for a city and a space was lengthy and complex. It began in 2003 and initially involved contact with the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, which showed little interest, followed by outreach to various cities in Germany and Spain (Alvear 2011; Remedios Lasso 2016). By 2002, Cáceres began to emerge as the most viable option.

Cáceres is a medium-sized city in the Extremadura region of Spain known for its extraordinary artistic and historical heritage, including a medieval old town designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1986 and recognized as one of the best preserved in Europe. As Remedios Lasso (2016) outlines in her dissertation, several factors converged in the early 2000s to generate interest and institutional support for contemporary art in Cáceres: the regional president and the Minister of Culture endorsed the creation of Cáceres’s first contemporary art fair, Foro Sur, directed by José Luis Viñuela, brother of José María Viñuela. The fair, launched in 2001, was a success from the outset, forging links between Extremadura’s emerging art scene and the rest of Spain as well as with galleries from Portugal and Latin America.

In 2002, returning from an exhibition by José Pedro Croft at the Centro Cultural de Belém in Lisbon, Helga de Alvear arrived in Cáceres with Viñuela. He took her to dine at Atrio, a restaurant gaining international recognition, where she met its owners, José Polo and Toño Pérez. Helga shared her ongoing search for a venue to house her collection, and Polo and Pérez facilitated an introduction to the president of the regional government, who immediately supported the initiative. In January 2003, an agreement was signed between Helga de Alvear and the Government of Extremadura to donate her collection to the city of Cáceres. The search for an appropriate venue began immediately.

The first exhibition of works from her collection in Cáceres coincided with Foro Sur in May 2003 and was held in various emblematic historical sites throughout the city. The Helga de Alvear Foundation was formally established in November 2006 as a non-profit cultural entity with the mission to preserve, promote, and expand the collection; support research on contemporary visual arts; and manage the Centro de Artes Visuales Helga de Alvear, located in the so-called Casa Grande, a modernist mansion built in 1910 in the medieval old town. The renovation project was commissioned by the regional government to the architectural firm Mansilla + Tuñón.

In December 2010, Atrio relocated to the Palacio Paredes Saavedra, a historic building in the monumental old town of Cáceres. The new premises included the restaurant—by 2025 awarded three Michelin stars—and a luxury hotel affiliated with the international chain Relais & Châteaux. The palace’s renovation was also undertaken by Mansilla + Tuñón, who were already involved in remodeling the Casa Grande. From the beginning, the similarities and dialogue between the interiors of the two buildings were clear: industrial materials, neutral colors, luminous and sober spaces, and vertical and horizontal lines creating harmony (Remedios Lasso 2016). Of particular note was the art collection adorning the restaurant and hotel walls—artworks mostly acquired at the Helga de Alvear Gallery—as well as site-specific installations by José Pedro Croft and Jorge Galindo and a welcome table displaying exhibition catalogues of these artists from museums worldwide. Periodically, the gallerist would loan a work by a notable artist to be exhibited on a specific wall in the restaurant in gratitude for Polo and Pérez’s advocacy and the enduring friendship between them and Helga.

5.2. Mansilla + Tuñón Arquitectos: A Museographic Vision of Space

The firm Mansilla + Tuñón Arquitectos, founded in Madrid in 1992 by Luis Moreno Mansilla and Emilio Tuñón, has become a cornerstone of contemporary Spanish architecture. Their work is characterized by formal and typological research where structure, material, and context are rigorously integrated into architectural logic (González Cruz 2021). Their approach blends conceptual clarity with constructive precision, employing “rules of the game” that allow varying degrees of design freedom without compromising formal coherence. The Royal Collections Gallery in Madrid (2003–2016) and the Helga de Alvear Museum of Contemporary Art in Cáceres (2015–2021, under the name Tuñón Arquitectos) share a meticulous attention to materiality, urban integration, and the tectonic expression of structure. Though formally distinct, both projects embody an architectural vision in which construction becomes image and the exhibition space responds equally to museographic logic and structural clarity (Butini 2024; Lindsay 2020; Tzortzi 2016). In this sense, the Madrid gallery and the Cáceres museum can be seen as two phases of a single architectural investigation, reinterpreting disciplinary legacy through a contemporary, critical lens.

The Royal Collections Gallery is one of the most significant architectural interventions of the 21st century within Madrid’s historical heritage context. Situated next to the Royal Palace and Almudena Cathedral, the gallery was conceived not as a standalone monument but as a topographic infrastructure consolidating the platform on which the monumental complex stands. Its architecture aims to visually disappear into the urban landscape, respecting the scale and memory of the surrounding environment (Jones and MacLeod 2016; González Cruz 2021).

The 40,000-square-meter building is structured around a robust framework of white reinforced concrete that defines both form and function. The spatial organization follows the concept of an “inhabited wall,” where visible columns and beams create monumental chambers reminiscent of cathedral naves. This structural logic governs both the building’s stability and its plastic expression: niches on the east wall and rhythmic sequences on the west wall act as architectural devices managing light and exhibition space. This material strategy, closely related to architectural minimalism, aligns with Macarthur’s (2002) concepts of the disciplined aesthetics of structured and contained form.

The museographic path begins with a descending ramp accompanied by elevators, enabling a fluid journey across three exhibition levels—a tool similarly employed in the Helga de Alvear Museum. In addition to galleries for artworks, the building includes an auditorium, library, and interactive spaces, offering a comprehensive functional program. Materials such as granite, wood, and concrete evoke durability and a timeless aesthetic aligned with the historical vocation of the site.

From a construction standpoint, the building exemplifies architectural discipline, where each formal decision is subordinated to structural principles. This approach recalls projects like the Roman Art Museum in Mérida and the Helga de Alvear Museum in Cáceres, where a strong coherence between architectural language and museographic content is also evident (Páramo Cerqueira 2021; Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Helga de Alvear n.d.).

The Museo de Arte Abstracto in the city of Cuenca, whose origins are closely linked to the genesis of the Helga de Alvear Museum, shares certain conceptual affinities despite contrasting paradigms. Both exemplify contemporary exhibition spaces integrated into historic urban fabrics. Their success lies in their deep articulation with preexisting contexts and the reconfiguration of the museum experience.

As Galisteo (2013) notes, the Cuenca Museo de Arte Abstracto, founded by Fernando Zóbel in 1966 and renovated by architects Fernando Barja and Francisco León Meler, was shaped by artist Gustavo Torner. A trained engineer and architect by vocation, Torner oversaw both the architectural adaptation and the museographic installation. The project involved adapting the emblematic Hanging Houses (Casas Colgadas) to an entirely new function: that of a museum. The site was chosen not merely for its monumental quality but for its symbolic weight and spatial potential for art display. Torner’s museographic solution synthesized the “white cube” principles of American art spaces—emphasizing spatial neutrality in favor of the artwork—with elements of Italian museography, inspired by figures such as Franco Scarpa and Carlo Albini and grounded in Giulio Carlo Argan’s reformist theories. The 1978 expansion, incorporating a Renaissance portal from another location, reinforced a “culture of the simulacrum” in which symbolic value outweighed historical accuracy. The project became a catalyst for urban regeneration and projected Cuenca onto the international cultural stage (Galisteo 2013).

By contrast, the Helga de Alvear Museum in Cáceres interprets architectural insertion as a spatial articulation between the historical city and its contemporary expansion. Its design features white concrete pillars, oak wood cladding, and angular volumetrics that emphasize a sophisticated manipulation of natural light (Figure 5). While Cuenca chose to re-signify and adapt a historical building, Cáceres opted for a new structure connected to an existing building from another period (Figure 6). Both projects converge on the idea that museum architecture transcends mere containment. They show how thoughtful architectural intervention can act as a driver of urban renewal and as a mediator between the temporal layers of urban fabric and contemporary artistic expression (Páramo Cerqueira 2021; Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Helga de Alvear n.d.).

Figure 5.

Interior of Casa Grande. Source: https://www.museohelgadealvear.com/es/, accessed on 5 August 2025.

Figure 6.

Exterior of the new building. Source: https://www.museohelgadealvear.com/es/, accessed on 5 August 2025.

5.3. Minimalist Dialogues in Museography

The architectural and museographic synthesis achieved in the Helga de Alvear Museum exemplifies several key trends and debates in the contemporary museum literature. The Tuñón Arquitectos project, combining new construction with the rehabilitation of the modernist Casa Grande, aligns with the understanding of museum architecture as an active agent in shaping visitor experience and urban context, integrating abstraction and materiality and creating an environment that enhances the experience of viewing art. José María Viñuela’s museographic vision—evident from the museum’s inaugural exhibition—was central in determining the placement of artworks and their dialogue with both space and audience.

The bulk of the collection, especially the important selection of minimalist art, has been allocated to the new museum building, while the Casa Grande primarily houses administrative spaces, temporary exhibitions, the library, and workshops. Therefore, the vision of Tuñón Arquitectos and of Viñuela himself has allowed them to broadly develop an exhibition project suited to the needs of each artwork and to the context of the collection. Thus, a simple volume has been built, from a formal and constructive perspective, which establishes a close dialogue with the Casa Grande.

The building features neutral white walls and oak wood, which provide a balanced backdrop for the artworks, allowing them to stand out without distraction. The interior spaces are sculpted with precise sequences, offering variations in height and depth that accommodate diverse artistic installations. The exhibition halls are grouped together using a functional, orderly, and flexible structure organized on four levels, with exhibition spaces designed to adapt to the scale and type of pieces displayed. The serial repetition of architectural elements modulates the facades, establishing a dialogue between the new structure and the historic surroundings. This approach creates a system of measures that bridges the old and the new, ensuring the museum fits seamlessly into its urban context while providing a modern space for art. Comb walls are used to protect the artworks on display, while in the circulation spaces, free-standing pillars are used to allow exterior light in. Natural light plays a pivotal role in the museum’s design and is treated as a building material. The perforated walls and carefully positioned openings control the flow of light, creating dynamic atmospheres that shift throughout the day. This thoughtful manipulation of light ensures that the artworks are illuminated in ways that highlight their textures, colors, and forms. Although mainly hermetic in its exterior form, the building offers a series of carefully designed, square-shaped openings, which allow for targeted illumination of a number of spaces, primarily through overhead lighting. The discreet interior finishes provide a neutral canvas on which to display the artworks, giving them prominence against the austerity of the exhibition space (Butini 2024; Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Helga de Alvear n.d.).

Lindsay (2020) emphasizes how museum architecture creates new experiences by linking design ideas from urban integration to technological detail. The Helga de Alvear Museum illustrates this approach, implementing a “strategy, not a form” that seeks a “common ground between the contemporary and that which enables the city to recognize itself” (Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Helga de Alvear n.d.). The building’s permeability—conveyed through white concrete pillars and masterful light management—not only shapes the exhibition spaces but also enables a fluid and immersive interaction with art. Large-format and varied-scale works benefit from this spatial design as do educational and cultural activities, which are fully integrated into the museum’s layout.

Jones and MacLeod (2016) argue that museum architecture maintains a “complex and intertwined” relationship with the institution and its users and that sociological studies of museum design are essential to understanding its impact. Situated between the historic and modern parts of Cáceres, the museum functions as an urban connector and catalyst. The restoration of the Casa Grande and its integration with the new construction not only enhance exhibition and administrative capabilities but also revitalize the urban fabric—a function Jones, MacLeod, and Pedersen (2011) would consider integral to the museum’s social role. While prioritizing artworks and their spatial demands, the museography benefits directly from the spatial and luminous qualities of Tuñón Arquitectos’s design, allowing the architecture itself to contribute to the narrative of the collection and to visitor engagement with contemporary art—especially the minimalist works present in the collection—thus supporting the thesis that architecture “adds authority to certain discourses” (Jones and MacLeod 2016).

The museum’s museography, closely tied to Tuñón Arquitectos’s contemporary design, resonates with the critical perspectives of Mark Jarzombek (2021). The “spacious galleries,” defined by white concrete pillars and intelligent use of natural light, enable clear exhibition layouts and direct appreciation of the works, particularly large-format conceptual pieces—Sol LeWitt and Joseph Kosuth—as well as Land Art figures like Carl Andre and Richard Long and Arte Povera by Mario Merz. This pursuit of spatial neutrality and optimal visibility for diverse artistic languages is a distinctive trait of the museum (Tzortzi 2016; Pedersen 2011).

Jarzombek (2021) introduces the concept of the “Civilization Industrial Complex,” suggesting that recent architectural trends—particularly in cultural institutions—tend to make “high art” and abstraction more “available” and intellectually less challenging through streamlined presentation. The Helga de Alvear Museum’s museography, by providing an almost aseptic and monumental setting for its works, could be seen as an example of this trend. Although the aim is to elevate the artwork, the immaculate design may paradoxically strip the art of its inherent roughness or ambiguity, integrating it into a pre-digested cultural experience—a critique Jarzombek levels at much of contemporary museum design.

Nonetheless, the museography presents tensions. While the architectural design offers expansive, asymmetrical galleries with enormous potential, some installation elements—such as drywall partitions interrupting structural beams—have been criticized for breaking the building’s formal clarity. However, these elements also facilitate thematic compartmentalization and provide both physical and symbolic support for artworks, introducing flexibility where needed to accommodate larger installations (Lindsay 2020).

Discursively, the project operates within an institutional architectural framework that, as Jarzombek (2021) notes, articulates historical narratives from positions of power. In this context, the exhibition’s intended narrative neutrality might be interpreted as a strategy to avoid explicit ideological readings, though not without controversy. As such, the Helga de Alvear Museum represents a synthesis of architecture, engineering, and museography—a project that, despite its inherent tensions, stands as a contemporary benchmark in managing both the built and exhibited heritage. Overall, the museum’s architecture is a thoughtful response to the needs of the artworks, blending functionality, aesthetic clarity, and contextual sensitivity.

6. Conclusions

The conclusions of this study reassert the transcendence of Helga de Alvear as a central figure in the shaping and international projection of the Spanish contemporary art market. Her prolific trajectory, spanning from the second half of the 20th century to the present day, positions her not only as a distinguished gallerist and collector but also as a visionary patron whose commitment to art and the artists of our time has left an indelible mark. De Alvear was a key agent in forging internationalization bridges between Spain and the rest of the world as well as in connecting with emerging markets, driving the development of the Spanish art market structures and their global dissemination. Her work exemplifies the multifaceted contribution of women in a field historically dominated by male figures, transforming the artistic landscape with her vision and determination.

The Helga de Alvear Collection is distinguished by its heterogeneity and the breadth of its artistic languages, encompassing everything from early avant-gardes to the most recent trends of the 21st century. A particularly relevant aspect is its considerable legacy of international minimalist art, which has been the subject of profound analysis and curatorial proposals, consolidating it as one of the most significant collections in Europe in this field. The inclusion of works by globally renowned artists and the exploration of concepts such as materiality and perception reflect exceptional intuition and instinct in artistic selection, forging a unique identity in collecting.

Finally, the donation of this invaluable collection to the city of Cáceres, materialized through the Helga de Alvear Foundation and the subsequent creation of the Helga de Alvear Museum, represents a milestone of undeniable social and cultural relevance. With over 3000 works, the museum has been conceived as a dynamic, inclusive, and open art center for the 21st century, dedicated to the exhibition, research, conservation, and education of artistic heritage. This initiative not only facilitates public access to a collection of exceptional magnitude but also revitalizes the urban fabric of Cáceres, establishing a geographical and conceptual nexus for contemporary art. The symbiosis between art and the exhibition space enhanced by innovative museum architecture underscores the museum’s impact on the city’s urban planning and Helga de Alvear’s lasting legacy in the global cultural landscape.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding source listed in the reference list.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The inaugurations in Cáceres—first of the Center for Visual Arts in 2010, and later of the Museum of Contemporary Art—placed Helga de Alvear at the center of attention in the mainstream media, extending beyond the artistic and curatorial spheres. They prompted numerous reports and interviews that introduced the gallerist and collector to the broader public. This exceptional primary source material has made it possible to gain deeper insight into her professional trajectory and, above all, into her vision and objectives in donating her legacy to the city of Cáceres and its citizens. In this text, we refer to the most significant among them. |

| 2 | We later examine the similarities between the location of Zóbel’s collection in Cuenca—a medium-sized Castilian city of considerable cultural, historical, and artistic value, yet, until then, disconnected from contemporary art—and Helga de Alvear’s choice of the Extremaduran city of Cáceres, which, although similarly notable for its exceptional medieval old town, likewise lacked a relevant contemporary art museum or center, much like Cuenca in the 1960s. Both cities have been designated UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The impact of such artistic and cultural institutions, along with the activities they generate, represents a milestone in the cultural, artistic, and social development of these cities and in their international visibility. |

References

- Aguilera Cerni, Vicente. 1973. Posibilidad e Imposibilidad del Arte. Valencia: Fernando Torres. [Google Scholar]

- Alvear, Helga de. 2011. Entrevista a Helga de Alvear. Revistaclavesdearte Video YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zkPaiyO0c7Q (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Alvear, Helga de. 2022. The passion for collecting and sharing. In Museo Helga de Alvear. Cáceres: Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Helga de Alvear, pp. 63–67. [Google Scholar]

- Battcock, Gregory, ed. 1995. Minimal Art: A Critical Anthology. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borja-Villel, Manuel. 2022. Gesture and authenticity. In Museo Helga de Alvear. Cáceres: Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Helga de Alvear, pp. 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Botha, Marc. 2017. A Theory of Minimalism. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bozicnik, Nina Gara. 2011. Women Gallerists in the 20th and 21st Centuries. Woman’s Art Journal 32: 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- Butini, Riccardo. 2024. Tuñón Arquitectos. Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Helga De Alvear, Cáceres, Spagna. Firenze Architettura 27: 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canal Extremadura. 2024. Helga de Alvear, Más allá del Arte. Documentales. Video YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NMAuuOnkV7A (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Chagnon-Burke, Veronique, and Caterina Toschi, eds. 2023. Women Art Dealers: Creating Markets for Modern Art, 1940–1990. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Chang Park, Mun Jung. 2024. Bloomsbury Art Markets. Madrid: Galería Helga de Alvear. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, Adelaide. 2020. The periphery is beautiful: The rise of the Portuguese contemporary art market in the 21st century. Arts 9: 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feria ARCO. 2015. 35 Aniversario ARCOmadrid—Helga de Alvear. Video YouTube. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FiA7dwAjlHA (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Fried, Michael. 1998. Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galisteo Espartero, Antonio. 2013. Aprendiendo del Museo de Arte Abstracto Español de Cuenca: 50 años de la gestación de un modelo paradigmático. Sociedad: Boletín de la Sociedad de Amigos de la Cultura de Vélez-Málaga 12: 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- González Cruz, Alejandro Jesús. 2021. Reglas de Juego y Grados de Libertad. Una Aproximación al Origen de la Forma en los Proyectos de Arquitectura de Mansilla+Tuñón [1992–2012]. Doctoral dissertation, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Álvarez, José Ignacio. 1998. El grupo El Paso y la crítica del arte. Espacio Tiempo y Forma. Serie VII, Historia del Arte 11: 437–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardiola, Ingrid. 2022. Inside the Helga de Alvear Collection #1. In Museo Helga de Alvear. Cáceres: Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Helga de Alvear, pp. 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hernando González, Amaya. 2024. Bloomsbury Art Markets. Madrid: Galería Juana Mordó. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herstatt, Claudia. 2008. Women Gallerists in the 20th and 21st Centuries. Ostfildern: Htaje Cantz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Hoag, Samuel Joseph. 2023. “El Problema Estético del Arte Comprometido”: Marxist Notions Of Committed Art In Spanish Criticism, 1959–1975. Doctoral dissertation, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Jarzombek, Mark. 2021. Architecture in the 1990s, the Mies van der Rohe Award, and the creation of the civilization industrial complex. In Rethinking Global Modernism: Architectural Historiography and the Postcolonial. Edited by Vikramaditya Prakash, Maristella Casciato and Daniel E. Coslett. New York: Routledge, pp. 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Paul, and Suzanne MacLeod. 2016. Museum architecture matters. Museum & Society 14: 207–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, Michelle. 2022. Dark Matter: From Object to Environment to Collection. In Museo Helga de Alvear. Cáceres: Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Helga de Alvear, pp. 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- LeWitt, Sol. 1967. Paragraphs on conceptual art. Artforum 5: 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, Georgia, ed. 2020. Contemporary museum architecture and design. In Theory and Practice of Place. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lippard, Lucy R., ed. 1997. Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object From 1966 to 1972. Berkeley: University of California Press, vol. 364. [Google Scholar]

- Macarthur, John. 2002. The Look of the Object: Minimalism in Art and Architecture, Then and Now. Architectural Theory Review 7: 137–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Chus. 2016. Idiosincrasia: Las Anchoas Sueñan con Panteón de Aceituna = Idiosyncrasy: Anchovies Dream of an Olive Mausoleum: 29 de Abril 2016 = 29 de April 2016. Cáceres: Centro de Artes Visuales Fundación Helga de Alvear. [Google Scholar]

- Marzona, Daniel. 2004. Minimal Art. Cologne: Taschen. [Google Scholar]

- Mesquida, Ivo, and José Augusto Ribeiro. 2016. Fora da Orden—Obras da Coleção Helga de Alvear. São Paulo: Pinacoteca de São Paulo. [Google Scholar]

- Museo de Arte Contemporáneo. n.d. Helga de Alvear. Available online: https://www.museohelgadealvear.com/es/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Páramo Cerqueira, Sancho. 2021. Museo de arte contemporáneo Helga de Alvear, Cáceres. Cercha: Revista de la Arquitectura Técnica 149: 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, Claus Peder. 2011. Cubes And Concepts: Notes On Possible Relations Between Minimal Art And Architecture. Urbanistika Ir Architektūra (Town Planning And Architecture) 35: 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicari, Giada. 2024. Art Basel in the 1970s: The Role of the Female Gallerists. Rewriting a History. PIANO B 8: 269–312. [Google Scholar]

- Remedios Lasso, Javier. 2016. Helga de Alvear: Los Cimientos de Una Gran Colección. Doctoral dissertation, Universidad de Extremadura, Cáceres, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, Julián. 2013. Breve diccionario Helga de Alvear (Una conversación de conversaciones). In El Arte del Presente. Madrid: CentroCentroCibeles de Cultura y Ciudadanía, pp. 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Marcos, Javier, and Anatxu Zabalbeascoa. 2018. An intransitive art. In La Perspectiva Esencial. Minimalismos en la Colección Helga de Alvear. The Essential Perspective. Minimalisms in the Helga de Alvear Collection. Alcobendas: Centro de Arte Alcobendas, pp. 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Torre, Alfonso de la. 2004. La poética de Cuenca. Una forma (un estilo) de pensar. In La Poética de Cuenca 40 Años Después, 1964–2004. Madrid: Ayuntamiento de Madrid, Área de las Artes, pp. 11–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tuchman, Phyllis. 1981. Minimal Art. Madrid: Fundación Juan March. [Google Scholar]

- Tzortzi, Kali. 2016. Museum Space: Where Architecture Meets Museology. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Viñuela, José María. 2018. The essential perspective. Notes on an exhibition. In La Perspectiva Esencial. Minimalismos en la Colección Helga de Alvear. The Essential Perspective. Minimalisms in the Helga de Alvear Collection. Alcobendas: Centro de Arte Alcobendas, pp. 37–41. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).