Abstract

This paper will examine how tomb chapel imagery changed to depict a state of being that marked a theological and cultural shift during the reigns of Thutmose IV and Amenhotep III. The iconography of the royal kiosk scene reflects the growing influence of solar theology. At the same time, the king, as the mediator between the gods and humanity, appears as the primary source of the tomb owner’s well-being in the afterlife. Scenes of family life give way to depictions illustrating the tomb owner’s official role in relation to the king. Likewise, many of the so-called innovations in Amarna tomb decoration are already evident, such as the depiction of locality and specificity, setting and action, emotion, and the spontaneity of the here-and-now. At this time in the tomb’s transverse halls and porticos, the king dominates the decoration in the public areas of the chapel, along with depictions of the deceased’s service to him. Family images are gradually relegated to the inner hall of tombs, becoming almost non-existent by the late reign of Amenhotep III. By the reign of his son, all tomb scenes became oriented towards Akhenaten, who alone would provide, along with the Aten, for the deceased’s cult, career, social identity, and eternal survival.

1. Introduction

During the Eighteenth Dynasty, the image of the tomb owner offering to the reigning king, enthroned within a kiosk, broadcast power, negotiated influence, and framed royal authority. A few publications have treated the iconography of the royal kiosk scene in Theban and Amarna tombs during the Eighteenth Dynasty (Radwan 1969; Kuhlmann 1977; Metzger 1985; Hartwig 2004; Kehrer 2009; David 2021). This essay will approach this scene as a point of departure to explore its underlying meaning, focusing on how the tomb owner was integrated into royal ideology in life and in death.

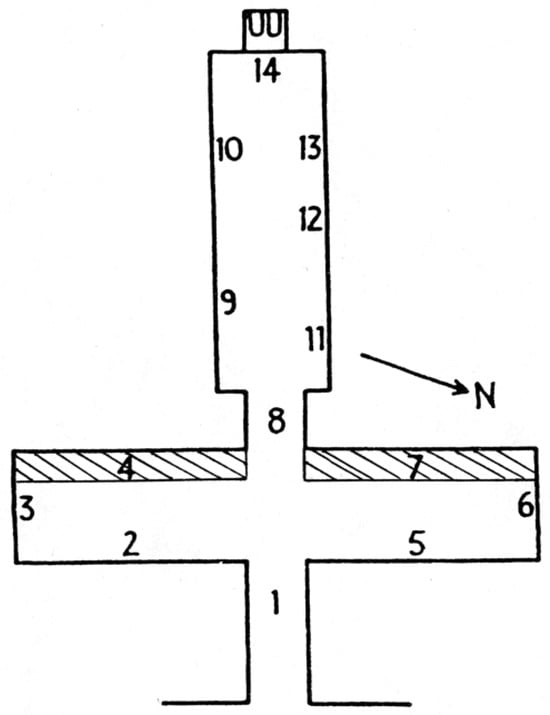

The royal kiosk scene and the deceased appear almost exclusively on tomb chapel focal walls, opposite the entrance from the outer forecourt, in the Eighteenth Dynasty (Figure 1).1 New Kingdom Theban tombs commonly took the form of an inverted “T,” with a horizontal transverse hall leading to an inner passage that terminated in a shrine. Focal walls stood to either side of the entrance into the interior passage, opposite the chapel forecourt, received the best light, and were the first to be seen by visitors. During the reign of Amenhotep III, the portico walls in the temple-like Theban tomb chapels featured similar decoration, primarily in the form of carved relief. In these tomb chapels, the wall decoration was arranged in a metaphorical sequence from east to west. Generally, scenes in the “eastern” transverse hall were concerned with the earthly life of the deceased, while those in the “western” inner passage addressed their transition into and life in the hereafter. The royal kiosk scene appeared at the nexus between representations concerned with the life of the tomb owner in the transverse hall and representations concerned with his afterlife in the inner rooms of the chapel.

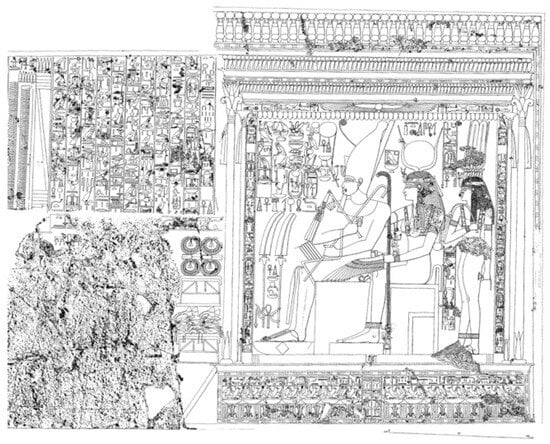

Figure 1.

Focal Walls of T-shaped Tombs, author’s drawing.

2. Iconography of the King Enthroned in a Kiosk

In Theban tomb chapels, the representation of the king enthroned in a kiosk dates back to the reign of Hatshepsut. It reached its apogee during the reigns of Thutmose IV and Amenhotep III, only to taper off in the reigns of Tutankhamun to Horemhab.

Twenty Theban tombs dating to the early Eighteenth Dynasty had the royal kiosk image on their focal walls. Of those, two tombs depict the ruler Hatshepsut.2 Eleven focal walls in eight tombs represented Thutmose III.3 Amenhotep II was shown on 14 focal walls in 12 tombs.4 By the reign of Thutmose IV, the king’s image decorated 21 focal walls in 14 tombs (Figure 2).5 In the reign of Amenhotep III, the king appeared on 16 focal walls in 12 tombs.6 From the reign of Amenhotep IV to Horemhab, a period of 50 years, only five Theban tombs (nine focal walls) featured the king’s image in a kiosk.7

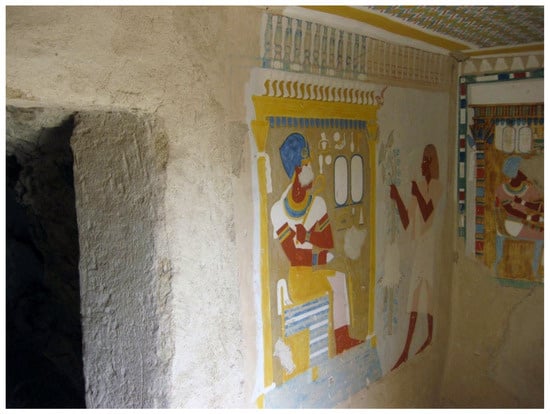

Figure 2.

Painting of Thutmose IV seated in a kiosk, Tomb of Neferrenpet, TT 43, PM (4), author’s photograph.

During the 80-year period encompassing the reigns of Hatshepsut to Amenhotep II, the enthroned king in a kiosk appears on 27 focal walls in 22 Theban tombs. Yet, during the 53-year period spanning the reigns of Thutmose IV and Amenhotep III, royal kiosk depictions adorn 37 focal walls in 26 Theban tombs, a significant increase over the previous 50-year period.

Royal kiosk representations appeared in the tombs of officials who held positions that brought them into direct contact with their king, often through religious promotion, military experience, or involvement in the palace, regional, or civil administration (Table 1). Likely, the tomb owners’ positions and contacts secured access to the land, materials, workers, and artists for their tombs (Eyre 1987).

Table 1.

Theban Tomb number, owner’s name, characteristic title, administrative affiliation, and tomb date.

When we examine royal kiosk scenes closely, the texts and the king’s kiosk, crowns, and attire illustrate solar associations. When the upper portion of the king remains, the ruler often wears the Blue Crown or khepresh (see Figure 3 and Figure 4).8 The Blue Crown was associated with celestial light (Collier 1996, pp. 120–27; Goebs 2008, pp. 367–68) and symbolized the ruler as the terrestrial agent of the sun god, particularly when accompanied by a kiosk captioned: “Appearance of the king upon the great throne like his father Re, every day” (Figure 5; Bryan 2007, pp. 178–80). A similar caption accompanies the khepresh-wearing king in the tomb of Khaemhat (TT 57): “Appearance of the king upon the great throne to receive the documents of harvesting of Upper and Lower Egypt” (Figure 6; Helck 1955–1958, p. 184).

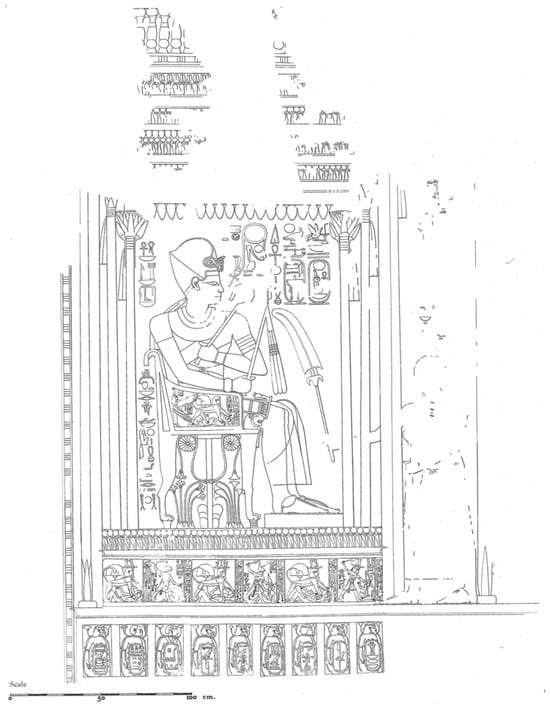

Figure 3.

Amenhotep III seated in a kiosk, Tomb of Amenemhet Surer, TT 48, PM (7), (Säve-Söderbergh 1957), pl. XXX.

Figure 4.

Userhet (destroyed) offering to Amenhotep III and Tiye enthroned in a kiosk, protected by the wings of Horus, on the focal wall of TT 47, (Kondo and Kawai 2017, fig. 5. Photograph courtesy of Jiro Kondo and Nozumo Kawaii).

Figure 5.

Tiye in a kiosk, Kheruef presenting a golden decorative vase, with Heb Sed text of year 36. TT 192, Kheruef, PM (8), After The Epigraphic Survey (1980, pl. 47).

Figure 6.

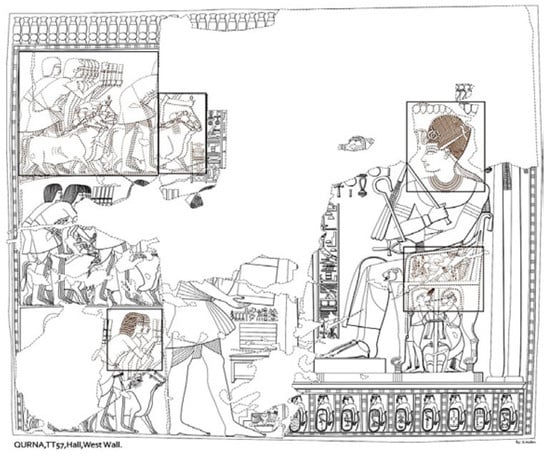

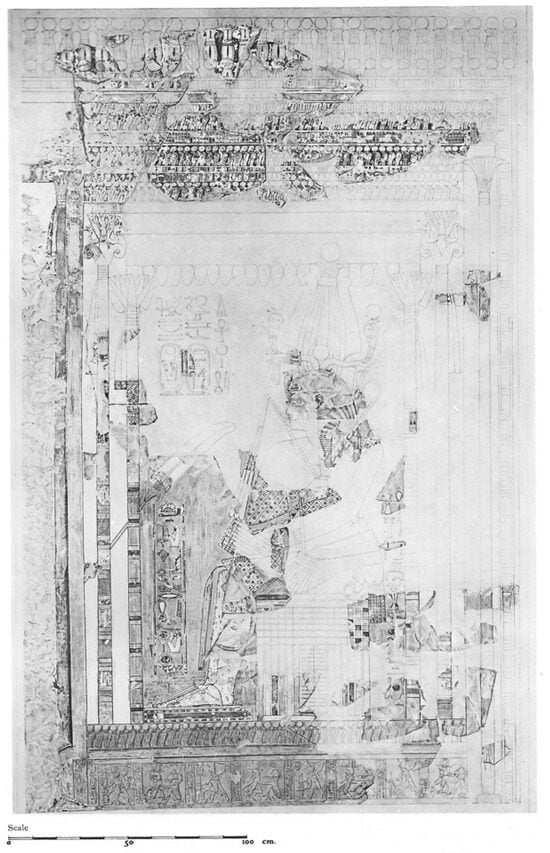

Amenhotep III seated in kiosk with Khaemhat presenting year 30 Harvest Records, TT 57, PM (11), After Amani Hussein Ali Attia (2022, Figure 24A, Drawing by Ahmed Abdel Halim).

Seated within the kiosk, the ruler also wore crowns such as the Atef, which was adorned with the ram horns, uraei, and sun disks (Figure 6 and Figure 7; TT 75, PM (3), TT 78, PM (4)) and the Swty-crown with cow and ram horns (TT 76, PM 5),9 which signified kingship in this and the next world (Collier 1996, pp. 60–61). The king also appears wearing sSd-fillet in kiosk scenes, which symbolized the regeneration of the king through light during the New Year’s Festival (TT 76, PM (5)), and the Royal Jubilee (Figure 8; about the sSd-fillet, Collier 1996, pp. 65–68).

Figure 7.

Amenhotep III seated in a kiosk, Tomb of Amenemhet Surer, TT 48, PM (4), (Säve-Söderbergh 1957), pl. XXXI.

Figure 8.

Painting of Amenhotep III seated in a kiosk wearing the Atef-crown with solar disks and uraei, TT 58, PM (8), author’s photograph.

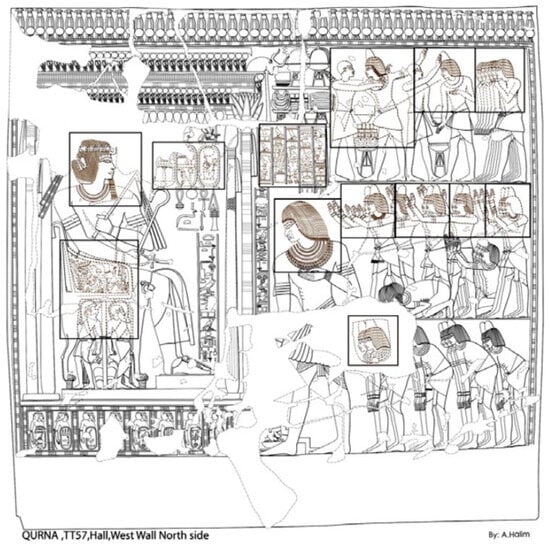

When both focal walls are preserved, royal crowns are juxtaposed. In the tomb of Kheruef (TT 192), the ruler wears the Blue Crown on one focal wall and the double crown of Atum on the other (Figure 5 and Figure 10). The similar juxtaposition between the Blue Crown and the Atef-Crown occurs in TT 58 (Figure 8 and Figure 11) and in Amenhotep Surer (TT 48) (Figure 3 and Figure 7). Likewise, the king could wear the Blue Crown on one wall and the sSd-fillet on the other, like in the tomb of Khaemhet (TT 57) (Figure 6 and Figure 9). By wearing these crowns, Amenhotep III appears as the earthly incarnation of the sun, as well as deified and assimilated with the solar gods.

Figure 9.

Amenhotep III seated in a kiosk awarding Khaemhat and other administrators with the text of year 30, TT 57, PM (15), After Amani Hussein Ali Attia (2022, Figure 27A, Drawing by Ahmed Abdel Halim).

Figure 10.

Amenhotep III, Hathor, and Tiye in a kiosk, with Kheruef rewarded and text of year 30. TT 192, Kheruef, PM (6), After The Epigraphic Survey (1980, pl. 24).

Figure 11.

Painting of the upper portion of Amenhotep III enthroned wearing a khepresh with Hathor in a kiosk, TT 58, PM (5), author’s photograph.

Royal solar associations are further underscored by the king’s dress of feathered sporrans adorned with solar uraei, red shirts and kilts, and winged or feathered block-thrones (discussion in Johnson 1996, p. 2).10 Red and yellow kiosk backgrounds also symbolized the solar aspects of kingship.

3. The King as Eternal Provider and the Amarna Prelude

As stated above, focal walls were a sensitive indicator of the deceased’s social environment and the roles in which the tomb owners desired to be remembered. Likewise, within the liminal, regenerative space of the tomb, the appearance of the pharaoh on the tomb owner’s focal walls, on either side of the doorway into the inner hall with its scenes of passage to and regeneration in the hereafter, indicates that the pharaoh oversaw the tomb owner’s journey to and life in the next world (Hartwig 2004, pp. 15–17, 37–40, 51).11 Based on their earthly existence, officials likely believed that they would serve the monarch in death to ensure the smooth functioning of his kingdom in the next world (Meeks and Favard-Meeks 1997, p. 149).

A critical component of the royal kiosk scenes was the deceased’s gift to the ruler. Here, the tomb owner presents valuable objects and reports to the king, and in return, receives awards. These objects could be golden vessels, jewelry such as pectorals, and bouquets.12 Bouquets were called ankh (anx) and had the same consonantal value as the ancient Egyptian word for “life.” To the ancient Egyptians, life-bouquets held the divine essence, having come from the altars of the gods. Similarly, objects such as pectorals symbolized life and protection, and golden foreign vessels secured the ruler’s “breath of life.”

In the tomb, the king appears in his potential, deified state, assimilated with the gods. The offering made by the tomb owner to the god-king ensured the deceased’s provisioning in the next life, through the reversion of offerings. In other words, it acted as a pictorial Htp-di-nsw, by which the king (nsw) gives (di) offerings (Htp) to the gods on behalf of the tomb owner for his or her continual well-being; the ruler being both king and god (Radwan 1969, p. 10, n. 39; Hornung 1982, pp. 203–4, 213–15; Englund 2001). To underscore this meaning, the Htp-di-nsw offering formula was written above some eighteenth dynasty kiosk scenes that depict the tomb owner offering objects imbued with life to the king in Theban tombs (Radwan 1969, pp. 39–40, 42, 106).

The Htp-di-nsw offering formula reflected the peculiarities of the reversion of offerings in which gifts given by the ruler to temple deities ‘reverted’ back to provide for the eternal life of the dead. Furthermore, Theban tomb texts suggest that during various necropolis festivals, divine offerings came from the memorial temple of the reigning king. Thus, in theory and practice, the well-being of the tomb owner’s eternal provisioning depended on the king (Fukaya 2020, pp. 74–76). In other words, as the king provided for the official in life, so would the ruler provide for him in death (Hartwig 2004, p. 17, n. 100, 51).

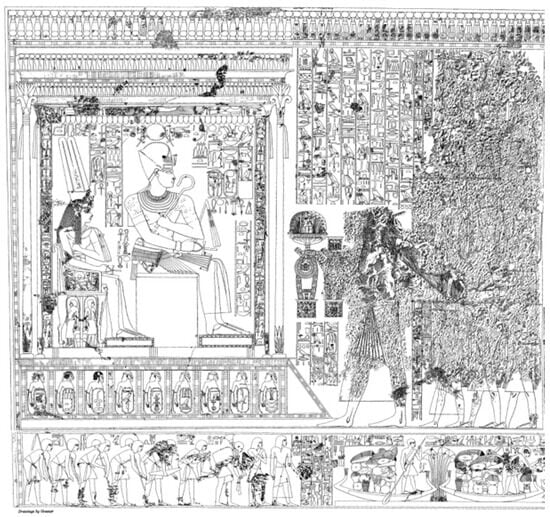

The tomb owner’s connection with the ruler is emphasized by the rewards, investments, and gifts that related to the duties he oversaw for the ruler during his lifetime. At the apogee of the kiosk scene during the reigns of Thutmose IV and Amenhotep III, the tomb owner’s career and self-presentation included troop and crop registration, New Year’s gifts, foreign tribute, and royal celebrations. Noteworthy in these scenes are many of the so-called innovations of Amarna tomb decoration, such as the depiction of locality and specificity, setting and action, emotion, and the spontaneity of the here-and-now. Examples include the rendering of events with regnal year captions in the promotion of Nebamun (TT 90), which occurred in Thutmose IV’s regnal year 6 (Davies and Davies 1923, pl. XXVI; Urk. IV, 1618–1619). Amenhotep III’s year 30 bumper harvest is celebrated in the tomb of Khaemhat (TT 57) (Figure 5, Urk. IV, 1841; and Figure 6, Urk. IV, 1842) as are the king’s First and Third Sed Festivals in the tomb of Kheruef (TT 192) (Figure 9, Urk. IV, 1867; and Figure 10, Urk. 1860, respectively). The specificity of dating continues in Amarna tomb texts and depictions that mention Akhenaten’s ‘durbar’ in regnal year 12, in the tombs of Meryre II and Huya (see texts in David 2021, pp. 407–8).

Scenes of the tomb owner’s promotion and royal support relate to actual sites like Amenhotep-si-se’s installation as the Second Prophet of Amun (TT 75, PM (6), see note 5 above) and celebration before the pylon that once marked the southern entrance to the Festival Court in the Temple of Amun-Re at Karnak (discussed by Gabolde 1993, p. 15). On the adjacent focal wall in the same tomb, objects depicted on PM (3) directly relate to the same objects illustrated on the walls of Thutmose’s Peristyle Court (Hartwig 2004, pp. 80–81, fig. 19, pl. 18.3). On the wall of the west portico of Kheruef (TT 192, PM (5), I,2), Amenhotep III’s palace is shown in plan and elevation (The Epigraphic Survey 1980, pl. 42). Likewise, during Amenhotep III’s reign, the tomb of Khaemhat (TT 57) shows a very early Window of Appearance (Binder 2008, p. 83) as well as on a relief block from Karnak (Bickel 2006, pp. 30–32, fig. 12).

Setting and action occur in the scene of conscription, registering, and provisioning troops in the tomb of Haremhab on PM (4) (Brack and Brack 1980, taf. 86), which evokes the here-and-now in a vignette of a group of troops entering a supply depot door with the first man’s upper torso disappearing behind the door (Brack and Brack 1980, p. 35, taf. 42, 45b). Compare the royal retinue in the Amarna tomb of Mery-re (Amarna Tomb no. 4), whose hands and forearms disappear behind the chariot cage (Davies 1903, pl. XXIV, XXV). Theban tomb paintings of dancers, clapping their hands, tapping their feet, and swaying to music (Brack and Brack 1980, taf. 3, 37a, 47b, 51a; and TT 116, PM (1) = Hartwig 2004) influenced similar scenes found in the carved reliefs of Amarna (MMA 1985.328.11 = Cooney 1965). Atmosphere is rendered in a vignette of a heron perched on a papyrus thicket, seen through the bluish mist of dawn (Brack and Brack 1980, taf. 21a). This type of rendering finds its way into the painted tableaus at Amarna (Weatherhead 2007). The rendering of all five toes on the near foot and the frontality of women’s breasts in Theban tombs also finds its way into the art of the Amarna Period (Russmann 1980, p. 77).

4. The King as Focus

As the royal kiosk scene begins to dominate the decoration of Theban tomb chapels, family scenes disappear in the “public” transverse hall, only to be replaced by images of the king, the royal family, colleagues, anonymous participants, and even events. When images of family members do appear, they are relegated mainly to the smaller, and often darker, inner hall. The shift is gradual. For example, in TT 74 dating to the reign of Thutmose IV, Tjanuny’s wife, Mutiry, and their sons are depicted in the transverse hall (Brack and Brack 1977, pp. 88–89; Whale 1989, pp. 192–93). And, in the tomb of Amenhotep-se-se (TT 75), images of his wife, Roy, and daughters figure prominently, particularly in the depiction of the celebration of his promotion to the Second Prophet of Amun on the focal wall, PM (6) (Whale 1989, pp. 186–88). In the tomb of Ptahemhat (TT 77), his wife Meryt, his brother, and some children of the nursery are represented in the transverse hall (Manniche 1988, pp. 7–9, 11).

In the tomb of Sobekhotep (TT 63), his wife, Meryt, rarely appears in the transverse hall; instead, she, the family, colleagues like Menna (overseer of the sealers), are relegated to the inner hall (Dziobek and Abdel Raziq 1990). In the tomb of Hekarneheh (TT 64), his professional associations are highlighted. His father, Hekareshu, is prominently depicted, including in the famous scene of Thutmose IV sitting on Hekareshu’s lap as a child, and six other royal children (Roehrig 1990, pp. 212–13; Bryan 1991, pp. 54–55). In the tomb of Hepu (TT 66), only his wife, Rennay, appears in the transverse hall; all other family images are located in the inner hall (Whale 1989, pp. 202–3). In TT 76, belonging to Tjenuna, his wife Nebettawy is depicted on only one pillar in the hall (Whale 1989, pp. 194–95). In TT 116, belonging to an official who served Amenhotep II and Thutmose IV, his daughter “Mi..” appears on the Valley Festival wall in the transverse hall, PM (1). All other banqueting participants in TT 116 are anonymous (Urk. IV, 1602). His wife offers a bouquet to the king enthroned in a kiosk on the focal wall (PM 2) (Hartwig 2009).

In TT 78, Haremhab’s wife, mother, and brother appear in the transverse hall, along with the royal princess, Amenemopet, who sits on the tomb owner’s lap (Brack and Brack 1980, pp. 24–30, 82). While Haremhab served the kings Amenhotep II and Amenhotep III, the decoration in the transverse hall was completed during the reign of Thutmose IV, and the inner hall was partly completed during the reign of Amenhotep III.

During the transitional period from Thutmose IV to Amenhotep III, depictions of family members decrease even further. In TT 91, family members do not appear (Urk. IV, 1598–1599). In the tomb of Amenmose, TT 118, no family depictions appear (Gordon 2021). In the heavily destroyed tomb of Re, TT 201, only anonymous offering figures and servants remain (Redford and Redford 1994, pp. 4–14). In TT 239, Penhet’s wife, Hetepti, appears on the stela and the entrance walls to the transverse hall (Gardiner n.d.). In TT 58, only the image of the anonymous original tomb owner occurs in the transverse hall (Polz 1990, pp. 307–8). In Amenmose’s chapel, TT 89, several chiefs of Punt, Syrian, and Nubian tribute bearers appear, as well as a butcher named Sedjemamun (Davies n.d.). In TT 226, the transverse hall contains anonymous offerers and the famous scene of the tomb owner holding four sons of Amenhotep III on his lap (Davies and Davies 1933, pp. 35–40; Shirley 2015, pp. 439–41). In the tomb of Kenamun (TT 162), his wife Muttuy is represented in the upper register PM (1), with the arrival of Syrian merchants and their ships prominently depicted in the second register. Their son, shown as a sem-priest, appears on both near walls of the transverse hall (Davies et al. 1963, pl. XVI; Davies and Faulkner 1947). However, images of Kenamun’s wife and family are primarily relegated to the inner passage (Davies et al. 1963, pp. 15–17, pl. XVIc, XIX).

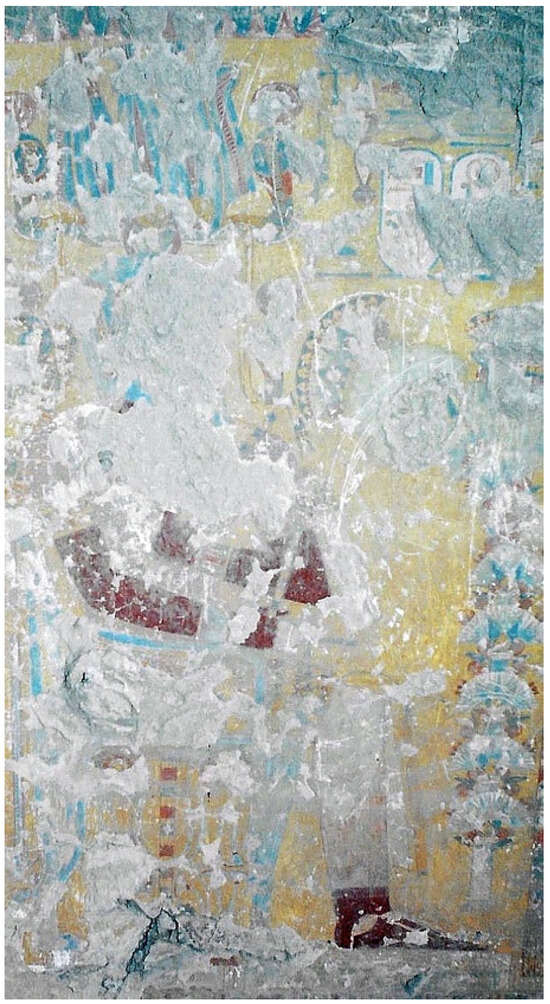

By the reign of Amenhotep III, the relief-decorated tomb chapels emphasize the king and the tomb owner’s service to him. The tomb of Userhet (TT 47) (Figure 11) only shows the tomb owner in the heavily destroyed transverse hall (Carter 1903, pp. 177–78; Kondo and Kawai 2017). Amenemhet Surer’s (TT 48) mother, Muttuy, a Xkrt-nwst and connected to the royal court, is depicted on the entrance jambs and once in the transverse hall, while his father is relegated to the inner columned hall. In the tomb of Khaemhat, TT 57, we find life-size rock-cut statuary on the left small wall of the transverse hall, PM (10), depicting the tomb owner and his father, Imhotep, with a relief of the tomb owner’s wife between them (Attia 2022, pp. 75–76). However, most of the family statues are found in the inner room of TT 57 (Attia 2022, pp. 268–69). In the tomb of Kheruef (TT 192), episodes from the 1st and 3rd Sed Festivals dominate the decoration of the focal wall of the portico, PM (5)-(6) and PM (8)-(7), respectively. Amenhotep III, Tiye, royal princesses, Amenhotep IV (in the style of Amenhotep III), god’s fathers, and royal acquaintances, among others, are highlighted, almost to the exclusion of Kheruef and his family members. Renderings of Kheruef’s mother, the royal concubine Ruiu, and his father, Siked, an army scribe, are pushed into the first inner hall (The Epigraphic Survey 1980, p. 25, pls. 70, 72, 73).

5. The State of ‘Being’ and the Theological and Cultural Shift

In Theban tombs, focal wall decoration was highly charged. Within the liminal space of the tomb, the exclusive depiction of the royal kiosk scene marked a theological and cultural shift during the reigns of Thutmose IV and Amenhotep III. The ruler’s crown, dress, throne, and adjacent texts reveal a controlled ideology that heralded the growing influence of solar theology.

Royal kiosk iconography accentuated the ruler’s earthly incarnation and deification with the sun god. The king, depicted on the focal walls at the threshold between scenes of the tomb owner’s life in the hall and funerary and hereafter scenes in the inner room, is presented as the one who would oversee the deceased’s passage into and life in the next world. Here, the tomb owner’s offerings to the pharaoh acted as magically as a Htp-di-nsw, by which the king would give the offering to the gods on behalf of the tomb owners for their continual well-being. In this way, the king, as the mediator between the gods and man, appeared as the primary source of the tomb owner’s well-being in the hereafter.

Likewise, scenes of daily life give way to depictions illustrating the tomb owner’s official role in relation to the king in the transverse hall. We see in these scenes many of the so-called innovations of Amarna tomb decoration, such as the depiction of locality and specificity, setting and action, emotion, and the spontaneity of the here-and-now (for additional examples, see David 2021, pp. 157–60, 456).

Increasingly, on other walls in the transverse hall, images of banqueting and offering become populated primarily by members of the royal family, professional peers, or anonymous participants. At the same time, depictions of the deceased’s family members are relegated to the inner, smaller, darker areas of the tomb. One may question if the lack of family members in the transverse hall was due to the incompleteness of the tomb decoration or damnatio memoriae. While this may be the case in some tombs, in chapels where the decorative program is largely preserved, such as Amenemhet Surer (TT 48), Khaemhat (TT 57), Amenmose (TT 89), and Kheruef (TT 192), royal imagery dominated depictions in the transverse hall. Whether this was the choice of the tomb owner or the accepted iconography of the time, the point is moot. A conscious choice was made to emphasize the king, wrapped in solar iconography, as the center of the deceased’s world. This change marked a cultural shift in the deceased’s state of being in this and the hereafter.

By the reign of his son Akhenaten, it was the king to whom all individual religious aspirations would turn (Bickel 2002, p. 83; David 2021). Akhenaten and the royal family dominate the outer rooms of officials’ rock-cut chapels. In contrast, family members, if they appear at all, are consigned to inner corridors, doorways, statue shrines, and votive stela (see for example the tombs of Panehsy and Huya; Davies 1905b, pls. 20 and 22; Davies 1905a, pls. 22–24). In Amarna’s elite tombs, the iconography centers exclusively on the ruler’s activity and role as mediator for only one god—the Aten. Akhenaton’s “revolution from above” (Eaton-Krauss 2001) takes religious experience out of the hands of the people and puts it under the exclusive control of the king, who alone could intercede with the Aten on behalf of his subjects. The tomb owner’s family no longer acted directly on behalf of the deceased’s perpetual provisioning and were banished to the nether regions of the tomb chapel. Instead, the tomb owner’s dependence on the king and the Aten for his daily and eternal needs is absolute. All tomb scenes were oriented towards Akhenaten, who alone would provide, along with the Aten, for the deceased’s cult, career, social identity, and eternal survival. However, as revealed in decorative programs in Theban tombs, this change in kingship and the deceased’s state of being had its antecedent in the reigns of Akhenaten’s father and grandfather.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Tomb identifications and dates are based on (Porter and Moss 1960; Kampp 1996, pp. 140–43), also see individual citations below. Specific walls are referred to as PM (#). Chronology used in the article is found in (Hornung et al. 2006). Many thanks to the reviewers of this essay who offered valuable suggestions, especially Betsy Bryan who gave the text a close read. |

| 2 | Amenhotep?, TT 73, PM (3); Djehuty, TT 110, PM (9). |

| 3 | Amenmose, TT 42, PM (5); Amaunnedjeh, TT 84, PM (5) & (9); Amenemhab, TT 85, PM (17); Menkheperresoneb, TT 86, PM (2) & (8); Senneferi, TT 99, PM (3) & (5); Rekhmire, TT 100, PM (5); Djehuty, TT 110, PM (9); Dedi, TT 200, PM (3), both AII and TIII. |

| 4 | Amenemhab, TT 85, PM (9); Unknown, TT 143, PM (6); Dedi, TT 200, PM (3), both AII and TIII; Nebenkemet, TT 256, PM (3); Userhet, TT 56, PM (9); Re, TT 72, PM (5); Pehsuker, TT 88, PM (4); Suemniwet, TT 92, PM (8); Kenamun, TT 93, PM (9) & (17) = (Radwan 1969, p. 20 (a)); Sennefer, TT 96, PM (6) & (10); Tjenro, TT 101, PM (5) = (Radwan 1969, p. 6); TT 367, PM (5). |

| 5 | Neferrenpet, TT 43, PM (4) = (Hartwig 2020); Sobekhotep, TT 63, PM (5) & (10) = (Dziobek and Abdel Raziq 1990), taf. 33–34; Hekerneheh, TT 64, PM (5) & (8) = (Hartwig 2004, fig. 13–14); Amenhotep-si-se, TT 75, PM (3) = (Hartwig 2004, p. 54, n. 7), and (Davies and Davies 1923, pl. XI, XII); Tjenuna, TT 76, PM (5) = (Hartwig 2004, fig. 20); Ptahemhet, TT 77, PM (4) = (Manniche 1988, fig. 18); Haremhab, TT 78, PM (4) & (8) = (Brack and Brack 1980), pl. 86–87; Unknown, TT 91, PM (5) = (Hartwig 2004, fig. 32); TT 116, PM (2) = (Hartwig 2009). Where a kiosk scene was recorded or suggested on a focal wall(s): Hepu, TT 66, PM (6) = (Radwan 1969, pp. 18–19); Tjanuny, TT 74, PM (6) & PM (11) = (Brack and Brack 1977, p. 20, taf. 28a-b, 29a-b); Amenhotep-si-se, TT 75, PM (6) = (Davies and Davies 1923), 8, pl. XIII, XIV; Ptahemhet, TT 77, PM (7) = (Hartwig 2004, 58, n. 4); and (Manniche 1988, fig. 23); Nebamun, TT 90, PM (9), tomb dates to Thutmose IV/Amenhotep III = (Davies and Davies 1923, p. 33, pls. XXVIII, XX, XXX, XXXI, XXXIII); and PM (4), (Davies and Davies 1923, pls. XXVI, XXVII); and Amenmose, TT 118, PM (1) = (Gordon 2021); TT 201, PM (7) = (Redford and Redford 1994, p. 28). Most of these focal walls are illustrated in (Hartwig 2004). |

| 6 | Userhet, TT 47 = Figure 4 (Porter and Moss 1960, p. 87), and (Kondo and Kawai 2017); Amenemhet Surer, TT 48, PM (4) & PM (7) = (Säve-Söderbergh 1957), pl. XXX, XXXI; Khaemhat, TT 57, PM (11) & PM (15) = (Attia 2022, figs. 24A, 27A); Unknown, TT 58, PM (5) & (8) = Figure 8 and Figure 11; and (Lepsius et al. 1900), vol. III, text, 258, no. 43; Amenmose, TT 89, PM (15) = (Brock and Shaw 1997, fig. 5), and (Davies and Faulkner 1947, pls. XXIII–XXIV); Unknown, TT 91, PM (3) = (Hartwig 2004, fig. 31); Anen, TT 120, PM (3) = (Davies 1929, figs. 1–3); Kenamun, TT 162, PM (4) = URL http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/gri/gif-files/Davies_10_47_04left.jpg (accessed on 5 September 2025), and tomb date in (Murnane 1998, p. 194); Kheruef, 192, PM (6) & (8) = (The Epigraphic Survey 1980, pls. 24 and 47); Huy?, TT 226, PM (4) = (Davies and Davies 1933, pls. XLI–XLII) and (Shirley 2015). Where a kiosk scene was recorded or suggested on a focal wall: Re, TT 201 PM (9) = tomb date in (Redford and Redford 1994, p. 27), and (Bryan 1991, p. 248); and Penhet, TT 239, PM (3) (Gardiner n.d.), dated to Amenhotep III in (Murnane 1998, pp. 227–28, n. 16). Focal walls of TT 91, TT 89, TT 120, TT 201, TT 226, TT 239 are illustrated in (Hartwig 2004). |

| 7 | Ramose (TT 55), tp. Amenhotep IV, PM (7) & (13); Amenhotep Huy, TT 40, PM (7) & (11), tp. Tutankhamun; Neferhotep, TT 49, PM (7), tp. Ay; Ramose, TT 55, PM (7) & (13), tp. Amenhotep IV; Parennefer, TT 188, PM (9) & (12), tp. Amenhotep IV. |

| 8 | The ruler wearing Blue Crown is found on the following focal walls: TT 43, PM (4) = Figure 2, (Hartwig 2020); TT 64, PM (5); TT 47, Userhet, Figure 4; TT 48, Figure 3; TT 57, Figure 6; TT 58, Figure 11; TT 77, PM (4); TT 89, PM (15); TT 91, PM (3) & (5); TT 116, PM (2); TT 192, Figure 5; TT 226, PM (4); see publications in notes 5 and 6; also (Hartwig 2004, p. 61, n. 74). |

| 9 | See note 5 for specific images. |

| 10 | |

| 11 | See (Hartwig 2004, pp. 54–86, figs. 11–16, 19–26, 28–32, 34–35, 43–45, B&W pls. 3–4). To this add: TT 47, Figure 4; (Säve-Söderbergh 1957), p. 39, n. 4; TT 48, (Säve-Söderbergh 1957), PM (7), pl. 36 and PM (4), pl. 40; TT 57, PM (11), presentation of harvest records, (Attia 2022, pp. 94–105, fig. 24A); TT 120, URL http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/gri/gif-files/Davies_10_39_01.jpg (accessed on 5 September 2025); TT 162, URL http://www.griffith.ox.ac.uk/gri/gif-files/Davies_10_47_04middle.jpg (accessed on 5 September 2025); TT 192, PM (8), (The Epigraphic Survey 1980, pl. 47); TT 226, PM (4), (Davies and Davies 1933), pls. XLI–XLII); and awards such as the Gold of Honor (TT 57, PM (15) = (Attia 2022); TT 192, PM (6) = (The Epigraphic Survey 1980), pl. 24). |

| 12 | Note that since the 4th Dynasty, the Htp-di-nsw formula related to the deceased’s position in the afterlife and dependence on royal supply for eternal well-being. Thanks to the anonymous reviewer who brought this to my attention. |

References

- Attia, Amani Hussein Ali. 2022. Tomb of Kha-em-hat of the Eighteenth Dynasty in Western Thebes (TT 57). Archaeopress Egyptology. Oxford: Archaeopress, vol. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel, Susanne. 2002. Aspects et fonctions de la déification d’Amenhotep III. Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale 102: 63–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel, Susanne. 2006. Amenhotep III à Karnak: L’étude des blocs épars. Bulletin de la Société Française D’égyptologie 167: 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, Susanne. 2008. The Gold of Honour in New Kingdom Egypt. ACES 8. Oxford: Aris and Phillips. [Google Scholar]

- Brack, Annelies, and Artur Brack. 1977. Das Grab des Tjanuni: Theben Nr. 74. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo. Mainz: Zabern, vol. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Brack, Annelies, and Artur Brack. 1980. Das Grab des Haremheb: Theben Nr. 78. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern, vol. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, Lyla Pinch, and Roberta Lawrie Shaw. 1997. The Royal Ontario Museum Epigraphic Project: Theban Tomb 89 preliminary report. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 34: 167–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, Betsy M. 1991. The Reign of Thutmose IV. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, Betsy M. 2007. A ‘new’ statue of Amenhotep III and the meaning of the khepresh crown. In The Archaeology and Art of Ancient Egypt: Essays in Honor of David B. O’Connor. Edited by Zahi A. Hawass and Janet E. Richards. Le Caire: Conseil Suprême des Antiquités de l’Egypte, pp. 151–67. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Howard. 1903. Report of work done in Upper Egypt (1902–1903). Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte 4: 171–80. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, Sandra A. 1996. The Crowns of Pharaoh: Their Development and Significance in Ancient Egyptian Kingship. Ann Arbor: UMI. [Google Scholar]

- Cooney, John. 1965. Amarna Reliefs from Hermopolis in American Collections. New York: Brooklyn Museum. [Google Scholar]

- David, Arlette. 2021. Renewing Royal Imagery: Akhenaten and Family in the Amarna Tombs. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Nina de Garis. 1903. The Rock Tombs of el Amarna. Archaeological Survey of Egypt. 6 vols. 13–18. London: Egypt Exploration Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Nina de Garis. 1929. The Egyptian Expedition 1928–1929: The graphic work of the expedition. Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art 24: 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Nina de Garis, and Norman de Garis Davies. 1923. The Tombs of Two Officials of Thutmosis the Fourth (nos. 75 and 90). Theban Tombs Series; London: Egypt Exploration Society, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Nina de Garis, and Norman de Garis Davies. 1933. The Tombs of Menkheperrasonb, Amenmosě, and Another (Nos. 86, 112, 42, 226). Theban Tombs Series; London: Egypt Exploration Society, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Nina de Garis, Norman de Garis Davies, Jaroslav Černý, and R. W. Hamilton. 1963. Scenes from Some Theban Tombs (Nos. 38, 66, 162, with Excerpts from 81). Private Tombs at Thebes. Oxford: University Press for Griffith Institute, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Norman de Garis. 1905a. The Tombs of Huya and Ahmes. Part 3, The Rock Tombs of El Amarna. Archaeological Survey of Egypt 15. London: Egypt Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Norman de Garis. 1905b. The Tombs of Panehesy and Meryra II. Part 2, The Rock Tombs of El Amarna. Archaeological Survey of Egypt 14. London: Egypt Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Norman de Garis. n.d. Davies MSS 11.1. Tomb of Amenmose. Oxford: Griffith Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Norman de Garis, and R. O. Faulkner. 1947. A Syrian trading venture to Egypt. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 33: 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziobek, Eberhard, and Mahmud Abdel Raziq. 1990. Das Grab des Sobekhotep: Theben Nr 63. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo. Mainz: Zabern, vol. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. 2001. Akhenaten. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Edited by Donald B. Redford. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 1, pp. 48–51. [Google Scholar]

- Englund, Gertie. 2001. Offerings: An Overview. In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Edited by Donald B. Redford. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 2, pp. 564–69. [Google Scholar]

- Eyre, Christopher J. 1987. Work and the Organization of Work in the New Kingdom. In Labor in the Ancient Near East. Edited by M.A. Powell. American Oriental Society 68. New Haven: American Oriental Society, pp. 167–221. [Google Scholar]

- Fukaya, Masashi. 2020. The Festivals of Opet, the Valley, and the New Year: Their Socio-Religious Functions. Archaeopress Egyptology. Oxford: Archaeopress, vol. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Gabolde, Luc. 1993. La “Cour de Fêtes” de Thoutmosis II à Karnak. Cahiers de Karnak 9: 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, Alan H. n.d. Notebook, No. 72, p. 125 Verso. Oxford: Griffith Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Goebs, Katja. 2008. Crowns in Egyptian Funerary Literature: Royalty, Rebirth, and Destruction. Griffith Institute Monographs. Oxford: Griffith Institute, Ashmolean Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, Andrew Hunt. 2021. Theban Tomb 118: Its foreign “tribute” scene and its owner Amenmose. CIPEG Journal 5: 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwig, Melinda. 2004. Tomb Painting and Identity in Ancient Thebes, 1419–1372 BCE. Monumenta Aegyptiaca. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig, Melinda. 2009. The tomb of a HAty-a, Theban Tomb 116. In Offerings to the Discerning Eye: An Egyptological Medley in Honor of Jack A. Josephson. Edited by Sue H. D’Auria. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 159–68. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig, Melinda. 2020. The kings in the tomb of Neferrenpet (TT 43). In Guardian of Ancient Egypt: Studies in Honor of Zahi Hawass. Edited by Miroslav Bárta, Salima Ikram, Janice Kamrin, Mark Lehner, Mohamed Megahed and Khaled El Enany. Prague: Charles University, Faculty of Arts, pp. 595–610. [Google Scholar]

- Helck, Wolfgang, ed. 1955–1958. Urkunden der 18. Dynastie. 4 vols. (fasc. 17–22). Berlin: Akademie Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Hornung, Erik. 1982. Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many. Translated by John Baines. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hornung, Erik, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton. 2006. Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Leiden: Brill, vol. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, W. Raymond. 1996. Amenhotep III and Amarna: Some new considerations. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 82: 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampp, Friederike. 1996. Die Thebanische Nekropole: Zum Wandel des Grabgedankens von der 18. bis zur 20. Dynastie. Theben. Mainz: Zabern, vol. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Kehrer, Nichole. 2009. Das Bild Des Königs als Geschenk, Eine Form koniglicher Prasenz in thebanischen Grabanlagen des Neuen Reiches. In Texte-Theben-Tonfragmente: Festschrift fiir Günter Burkard. Edited by Dieter Kessler, Regine Schulz, Martina Ullmann, Alexandra Verbovsek and Stefan Wimmer. unter Mitarbeit von Barbara Magen und Maren Goecke-Bauer. Ägypten und das Alte Testament. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, vol. 76, pp. 241–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, Jiro, and Nozomu Kawai. 2017. Discovered, lost, rediscovered: Userhat and Khonsuemheb. Egyptian Archaeology 50: 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlmann, Klaus. 1977. Der Thron im Alten Ägypten: Untersuchungen zu Semantik, Ikonographie und Symbolik eines Herrschaftszeichens. Abhandlungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Kairo, Ägyptologische. Glückstadt: J. J. Augustin, vol. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Lepsius, Richard, Eduard Naville, and Kurt Sethe. 1900. Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopien: Text. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Manniche, Lise. 1988. The Wall Decoration of Three Theban Tombs (TT 77, 175, and 249). CNI Publications. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Meeks, Dimitri, and Christine Favard-Meeks. 1997. Daily Life of the Egyptian Gods. London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, Martin. 1985. Königsthron und Gottesthron: Thronformen und Throndarstellungen in Ägypten und im Vorderen Orient im Dritten und Zweiten Jahrtausend vor Christus und deren Bedeutung für das Verständnis von Aussagen über den Thron im Alten Testament. Alter Orient und Altes Testament. Kevelaer: Butzon & Bercker, vol. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Murnane, William J. 1998. The organization of government under Amenhotep III. In Amenhotep III: Perspectives on His Reign. Edited by Eric H. Cline and David B. O’Connor. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 173–221. [Google Scholar]

- Polz, Daniel. 1990. Bemerkungen zur Grabbenutzung in der thebanischen Nekropole. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo 46: 301–36. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Bertha, and Rosalind L. B. Moss. 1960. Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs, and Paintings I: The Theban Necropolis. Part 1: Private Tombs, 2nd revised ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Oxford: Griffith Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Radwan, Ali. 1969. Die Darstellungen des Regierenden Königs und Seiner Familienangehörigen in den Privatgräbern der 18. Dynastie. Münchner Ägyptologische Studien. Berlin: Hessling, vol. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Redford, Susan, and Donald Redford. 1994. The Akhenaten Temple Project, volume 4: The tomb of Re’a (TT 201). Aegypti texta propositaque. Toronto: The Akhenaten Temple Project, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Roehrig, Catharine H. 1990. The Eighteenth Dynasty Titles Royal Nurse (mn‘t nswt) Royal Tutor (mn‘ nswt), and Foster Brother/Sister of the Lord of the Two Lands (sn/snt mn‘ n nb t3wy). Ann Arbor: UMI. [Google Scholar]

- Russmann, Edna R. 1980. The anatomy of an artistic convention: Representation of the near foot in two dimensions through the New Kingdom. Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar 2: 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Säve-Söderbergh, Torgny. 1957. Four Eighteenth Dynasty Tombs. Private Tombs at Thebes. Oxford: University Press for Griffith Institute, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Shirley, J. J. 2015. An Eighteenth Dynasty tutor of royal children: Tomb fragments from Theban Tomb 226. In Joyful in Thebes: Egyptological Studies in Honor of Betsy M. Bryan. Edited by Kathlyn M. Cooney and Richard Jasnow. Atlanta: Lockwood Press, pp. 429–45. [Google Scholar]

- The Epigraphic Survey. 1980. The Tomb of Kheruef: Theban Tomb 192. Oriental Institute Publications. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, vol. 102. [Google Scholar]

- Weatherhead, Fran. 2007. Amarna Palace Paintings. Egypt Exploration Society, Excavation Memoir 78. London: Egypt Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Whale, Sheila. 1989. The Family in the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt: A Study of the Representation of the Family in Private Tombs. Australian Centre for Egyptology: Studies. Sydney: Australian Centre for Egyptology, Warminster: Aris & Phillips, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).