1. Introduction

Since the earliest stages of visual culture, humans have sought to represent the surrounding world through images—from prehistoric cave paintings to painting as a highly structured system of representation. For centuries, painting remained the primary medium through which visual codes, symbolic figures, and cultural archetypes were constructed and transformed. However, with the advent of cinema in the late 19th century, a radical shift occurred in the system of visual communication: the art of depiction acquired a new, dynamic form capable not only of fixing images but also of unfolding them in time. The evolution of visual media—from the static surface of the painted canvas to the audiovisual sequence of cinematic frames—led to a reconfiguration of genres, narrative structures, and modes of representation, while simultaneously preserving a continuity in the treatment of key iconographic motifs.

In the tradition of painting, the image of the woman has for centuries functioned not only as an object of aesthetic contemplation but also as a symbolic figure embodying harmony, order, and reconciliation. Particularly in allegorical and religious compositions, the female figure often represented justice, mercy, or wisdom—principles capable of counterbalancing destructive impulses and mitigating conflict. With the advent of cinema, these functions persist, although the visual language becomes more realistic and dynamic. In film—especially within genres marked by violence and social trauma, such as the Western or crime drama—the female protagonist frequently embodies moral strength, emotional equilibrium, and the capacity to restore order. Thus, the image of the woman in visual culture evolves from allegorical representation to psychologically complex character, while retaining its reconciliatory role as a cultural constant.

One of the key visual references for this study is the painting

The Intervention of the Sabine Women (1799) by the French artist Jacques-Louis David (

Figure 1). The composition and imagery of the painting clearly illustrate the role of a woman as a mediator between two opposing sides in a conflict.

Archetypal representations of goddesses—such as Themis, Nemesis, and Artemis—have long embodied ideals of justice, order, retribution, and rational control. These figures established a symbolic framework in which the feminine principle functions as a mediator between violence and law, chaos and structure. These archetypes have proven remarkably persistent, finding expression across artistic media from painting to cinema. They take on particular significance within the Western genre—one of the earliest and most enduring forms of cinematic storytelling—originally grounded in a documentary narrative rooted in the historical reality of the American frontier. The Western draws upon actual social conflicts, legal tensions, and moral dilemmas that accompanied the establishment of order in the so-called “Wild West.” Within this context, female archetypes symbolizing justice and reconciliation acquire renewed relevance, becoming integral to a narrative where historical realism is interwoven with profound symbolic meaning.

The Western is considered the hallmark of American cinema and remains one of Hollywood’s most popular genres. Characterized by profound morphogenesis and genre hybridization, the Western explores not only events that took place in America during the second half of the 19th century but also those of other countries and historical periods. This genre is inherently associated with historical context. On the one hand, it involves the depiction of actual historical events and figures; on the other, it allows for the insertion of fictional characters into a specific era, shaping archetypal representations of heroes.

The male hero has traditionally received the most attention in cinematic narratives, but the female hero is equally significant, especially in the Western genre, where women’s roles were historically complex and often constrained. The harsh environment, social hierarchies, and survival challenges in Westerns highlight the unique struggles and resilience of female characters: “Although the experience of male and female heroes is the same on the archetypal level, it differs in important particulars because of the roles and opportunities afforded each sex in western society” (

Pearson and Pope 1981, p. 5). Their journeys offer rich, multifaceted perspectives on courage, identity, and agency. Examining the female hero in Westerns provides deeper insight into how gender dynamics shape mythological and archetypal storytelling, expanding the understanding of heroism beyond traditional male-centered narratives.

This article examines Western films in which a European woman plays one of the central roles. Due to her ability to combine vulnerability with inner strength, she often serves as a cultural mediator between conflicting sides. Frequently, the protagonist’s image is so expressive that it itself becomes a stylistic device of the Western genre (e.g., Cresta Lee in Soldier Blue).

As a figure who suffers from violence and injustice, she often becomes the voice of conscience and justice. Such female heroes frequently establish a connection with Indigenous peoples, striving to understand their pain and culture. As “communication is a female strength” (

Pearson 2015, p. 301), women forced to survive in a harsh and unjust world act as intermediaries between two opposing sides, symbolizing the pursuit of reconciliation and the restoration of balance, often despite their own suffering.

Today, these female heroes serve as a reminder of the importance of resolving conflicts through dialogue rather than warfare. Mutual understanding, based on empathy and recognition of the rights of other cultures, becomes a key tool in preventing violence. The lessons of the past demonstrate that cooperation and a willingness to listen to one another can avert the devastating consequences of war, preserving not only lives but also the value of cultural diversity.

This article aims to identify recurring archetypes of the European woman as a cultural mediator in the Western genre by analyzing the evolution of representational codes in painting and film through a diachronic and comparative exploration of visual language in painting and cinema.

This study employs visual, narrative, and semiotic analysis, reflecting the complex nature of the material under investigation. Visual analysis made it possible to examine compositional structures and color schemes through which the image of the woman is constructed in both painting and cinema. The narrative approach allowed for an exploration of the female character’s function within the plot, particularly in relation to conflict and its resolution. Semiotic analysis was essential for interpreting symbolic elements and cultural codes that reactivate the figures of ancient Greek goddesses within a contemporary media context. The combination of these methods enabled a multidimensional reading of the woman as a cultural mediator in visual art forms.

2. Conceptual Discussion

Cinema, mythology, and archetypes are deeply interconnected, with films often drawing on mythological motifs and universal archetypes to craft compelling narratives. In genres like Westerns, these elements are particularly prominent, as the genre frequently explores timeless themes Conflict Between Cultures, Good vs. Evil, Honor and Revenge, Survival, Man vs. Nature, Justice and Law, Heroism and Sacrifice, Morality and Corruption, Fate and Free Will, etc. The interplay between cinema and mythology in the Western genre not only reinforces cultural narratives but also provides a deeper, symbolic layer that resonates with viewers on a subconscious level.

The present article develops the author’s previous research on the Western genre and historical cinema, particularly Western Remakes: Textual and Cultural Aspects (

Kosachova 2023) and War Film: Morphological and Dramaturgical Analysis (

Kosachova 2024). These earlier studies reflect an ongoing interest in the narrative structures, genre conventions, and cultural functions of historically oriented film. In continuity with this focus, the current analysis examines how archetypal representations of women evolve within the Western, tracing their transformation over time and between visual art and cinema.

The conceptual foundation of this study is based on the fundamental works of Carl Jung (

Jung 1964,

1970,

1972,

1989,

2004), Joseph Campbell (

Campbell 1968), and Carol S. Pearson (

Pearson and Pope 1981;

Pearson 2012,

2015) as well as the film studies of Robert McKee (

McKee 1997), Blake Snyder (

Snyder 2005), and John Truby (

Truby 2007,

2022).

Carl Jung, a Swiss psychologist and founder of analytical psychology, introduced the concept of archetypes as universal symbols embedded in the collective unconscious. Jung viewed mythology as a key source for understanding archetypes, which he considered universal, unconscious structures of the psyche that manifest through dreams, fantasies, and cultural symbols: “The concept of the archetype … is derived from the repeated observation that, for instance, the myths and fairytales of world literature contain definite motifs which crop up everywhere. We meet these same motifs in the fantasies, dreams, deliria, and delusions of individuals living today… They impress, influence, and fascinate us… and can therefore manifest itself spontaneously anywhere, at any time” (

Jung 1970, p. 847).

Gods and goddesses in mythological systems serve as powerful archetypal images, representing fundamental aspects of the human psyche and the collective unconscious. Carol S. Pearson admits: “Spiritual seekers may conceive of archetypes as gods and goddesses, encoded in the collective unconscious, whom we scorn at our own risk” (

Pearson 2012, p. 12). Goddesses function as symbols embodying key existential and psychological categories: forces of nature, social roles, moral values, and internal conflicts. These figures structure and organize human experience, acting as mediators between personal and collective levels of perception.

In an art historical context, divine archetypes manifest in artistic representations, where their attributes, gestures, and narratives are interpreted as visual allegories of universal concepts—love, wisdom, war, fertility. Thus, gods and goddesses function as metaphysical constructs that not only maintain a connection to mythological tradition but also facilitate self-awareness by projecting the unconscious onto sacred imagery.

In the Western genre, which focuses on conflicts between cultures, social groups, and individuals, the image of the European woman often appears as a cultural mediator capable of bridging opposing sides. The primary archetype reflecting this role is Eirene, the ancient Greek goddess of peace, daughter of Zeus and Themis (

Figure 2). As a symbol of harmony, cooperation, and stability, Eirene embodies the qualities attributed to female characters whose mission is to reconcile conflict and restore order.

The female mediator in Westerns not only connects opposing worlds (Indigenous peoples and settlers, law and chaos) but also symbolizes the hope for dialogue and integration through peaceful interaction. Writing about his journey to America and his encounter with Pueblo Indian culture, Carl Jung wrote: “We always require an outside point to stand on, in order to apply the lever of criticism… How, for example, can we become conscious of national peculiarities if we have never had the opportunity to regard our own nation from outside?.. Everything that irritates us about others can lead us to an understanding of ourselves” (

Jung 1989, p. 246). In this way, Jung tried to find those points of contact that would help establish a dialogue of cultures.

The Eirene archetype, in turn, emphasizes the importance of diplomacy, patience, and human connection, positioning the female figure as a conduit for universal values within the framework of social and cultural confrontation. The analysis of other archetypes associated with European female characters in Westerns will be carried out further.

Joseph Campbell, an American mythologist, expanded on Jung’s ideas by identifying the monomyth or “The Hero’s Journey”, a narrative structure deeply rooted in mythology. His exploration of the hero’s journey, paired with the myths he draws upon in his book, has offered valuable perspectives for this study.

At the same time, there remains a lack of fundamental research specifically dedicated to the female hero in cinematic narratives. Among the limited studies available, one of the most notable is the book

The Female Hero in American and British Literature, which also references the work of Joseph Campbell. The authors emphasize: “The great works on the hero—such as Joseph Campbell’s

The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Dorothy Norman’s

The Hero: Myth/image/Symbol, and Lord Raglan’s

The Hero: A Study in Tradition, Myth and Drama—all begin with the assumption that the hero is male. This prevailing bias has given the impression that in literature and life, heroism is a male phenomenon. This work begins with the assumption that women are and have been heroic, but that the culture has often been unable to recognize female heroism” (

Pearson and Pope 1981, p. 4). Carol S. Pearson, a scholar in psychology and writer, is recognized in academic discourse for her classification of archetypes, which became one of the main methodological foundations of this study. The clear systematization and straightforward presentation of the material have led to recognition and interest from a wide range of readers.

Methodological works on film dramaturgy were also deeply studied. Robert McKee, a screenwriting theorist, analyzed the structural principles of compelling storytelling. Blake Snyder, a screenwriter and consultant, developed the “Save the Cat!” method, which breaks down screenplay structure into accessible beats. John Truby, a screenwriting instructor, provided a more intricate approach to narrative design, emphasizing genre analysis and character transformation.

Additionally, modern researchers in film studies and narrative theory continue to explore the intersection of archetypes, mythology, and cinematic storytelling. Their contributions refine genre analysis, expand the understanding of character development, and adapt classical archetypal structures to contemporary filmmaking.

As the representation of female heroes in cinema expands, so does the scholarly interest in their narratives. The increasing number of filmmakers centering their stories on women (directors Maggie Greenwald of The Ballad of Little Jo (1993), Susanna White of Woman Walks Ahead (2017), Jennifer Kent of The Nightingale (2018)) signals a shift that necessitates further academic exploration. This ongoing development ensures that discussions on female archetypes in the Western genre remain a crucial area of study.

The following section of the article presents a comparative analysis of paintings and cinematic frames, organized according to the archetypes of ancient Greek goddesses. The sequence of examination is determined by the chronology of the key artworks, spanning from the late seventeenth to the early twentieth century, allowing for the tracing of the evolution of visual and conceptual representations of female archetypes across various artistic movements and styles—from the expressive Baroque and austere Neoclassicism to the emotive Romanticism and the aesthetics of the Pre-Raphaelites. The analysis begins with a narrative exploration of the archetype in cinema, aimed at revealing its plot functions and semantic connotations within the filmic medium. This is followed by a comparative juxtaposition of the painterly and cinematic images, which elucidates the distinctive features of the visual and symbolic embodiment of the archetypes in both media.

3. Leto Archetype: The Maternal Force Guarding the Innocent

Three female characters from western films—Deborah Wright from

Cheyenne Autumn directed by John Ford (1964), Cresta Lee from

Soldier Blue directed by Ralph Nelson (1970), and Sarah Ashley from

Australia directed by Baz Luhrmann (2008) embody the archetype of Leto (

Figure 3), symbolizing motherhood, protection, and the preservation of the future. Leto, who protected her children Apollo and Artemis from Hera’s persecutions, symbolizes maternal protection, resilience, and the ability to overcome challenges for the safety of her family and the maintenance of harmony.

Carl Jung repeatedly emphasizes the variability of the mother archetype in mythology: “The concept of the Great Mother belongs to the field of comparative religion and embraces widely varying types of mothergoddess” (

Jung 2004, p. 7); “Like any other archetype, the mother archetype appears under an almost infinite variety of aspects… First in importance are the personal mother and grandmother, stepmother and mother-in-law; then any woman with whom a relationship exists—for example, a nurse or governess or perhaps a remote ancestress” (

Jung 2004, p. 14). In the Western films under this analysis, the archetype of Leto manifests itself in the figures of the schoolteacher, the caring young woman, the adoptive mother, those characters who provide maternal warmth to children in need.

Deborah Wright (

Cheyenne Autumn) is a teacher who supports the Cheyenne in their struggle for freedom and embodies the archetype of Leto through her readiness to defend the oppressed, despite threats and her own suffering (

Figure 4). Like Leto, she acts in conditions of oppression and violence, maintaining faith in justice and striving to secure a future for those she considers her children.

The next female hero is Cresta Lee (

Soldier Blue), who is one of the wisest Western characters. Having lived with Native Americans for a long time, she later becomes a mediator between cultures, embodying the archetype of Leto in her ability to see the value of life even amidst war and destruction (

Figure 5). Like Leto, Cresta assumes the role of protector, trying to prevent violence and save as many lives as possible during the Sand Creek Massacre (1864), a well-documented historical event that serves as the central focus of the film

Soldier Blue. Her actions aim to preserve human dignity and seek justice in a world ravaged by conflict, which is the essence of the Leto archetype.

Cresta Lee understands the injustice and brutality underlying the conflict between American soldiers and the Native people. Unlike other characters, blinded by prejudice or orders, she seeks the truth and strives for justice. She stands against mass violence and bloodshed, and her compassion for Native peoples shows her ability to look beyond superficial stereotypes. She understands that Native Americans are not enemies but people fighting for survival in a world that destroys their culture and way of life.

The character of Sarah Ashley (

Australia) embodies the archetype of Leto by protecting the boy Nullah from numerous dangers threatening his life and freedom (

Figure 6). Like Leto, who saved her children from Hera, the Englishwoman Sarah becomes a shield for Nullah in the harsh colonial Australia, where racism, social inequality, and the threat of forced separation from his family loom over him. She serves as a mediator between two cultures—European and Aboriginal Australian—striving to find harmony and justice in a world divided by prejudice. Her struggle against discrimination, colonial oppression, and the destructive forces of war makes her the embodiment of the strength of maternal love and protector of the weak, much like Leto in Greek mythology.

Figure 3.

Latona and the Frogs (late 17th—early 18th century) by Francesco Trevisani.

Figure 3.

Latona and the Frogs (late 17th—early 18th century) by Francesco Trevisani.

Figure 4.

Deborah Wright from Cheyenne Autumn (1964) directed by John Ford, film frame.

Figure 4.

Deborah Wright from Cheyenne Autumn (1964) directed by John Ford, film frame.

Figure 5.

Cresta Lee from Soldier Blue (1970) directed by Ralph Nelson, film frame.

Figure 5.

Cresta Lee from Soldier Blue (1970) directed by Ralph Nelson, film frame.

Figure 6.

Sarah Ashley from Australia (2008) directed by Baz Luhrmann, film frame.

Figure 6.

Sarah Ashley from Australia (2008) directed by Baz Luhrmann, film frame.

The painting Latona and the Frogs, created by Francesco Trevisani in the period of late Baroque, exhibits the key characteristics of this style—dramatism, emotional expressiveness, emphasis on extreme existential conditions, and the opposition between life and death, reason and affect. Baroque art places great importance on the viewer’s emotional involvement: scenes of suffering, heroism, or mythological conflict are designed to evoke profound empathy.

The subject of the painting is drawn from Ovid’s Metamorphoses: the Latin goddess Latona (Greek Leto), mother of Apollo and Artemis, is denied water by Lycian peasants and, in response, transforms them into frogs. Within the context of painting, this becomes an allegorical expression of threat—directed toward motherhood and childhood—and an illustration of a myth in which divine power confronts human cruelty. The danger in the painting is symbolic, refracted through mythological narrative, but remains palpably present.

A parallel theme—the threat to a child and a woman amid cultural conflict—can be traced across the three aforementioned historical Westerns. In Cheyenne Autumn, the threat is manifested through the forced displacement of Native American tribes, the breakdown of familial ties, and the hardship of a coerced march, during which children perish from hunger, exposure, and attacks by pursuing authorities. In Australia, the danger arises from racial policies and colonial coercion: the child, of mixed Aboriginal heritage, finds himself at the center of systemic discrimination and faces the risk of being taken from his family.

However, the closest visual and structural parallel to Trevisani’s painting is found in Soldier Blue. In one key scene, a woman with a child occupies the left side of the composition, while the right side reveals the aftermath of the Sand Creek Massacre (1864). This instance of historical violence acts as a direct visual counterpart to the mythological retribution depicted in the painting.

In all cases, a three-tiered composition is employed, echoing the structural logic of Baroque visual narratives: Foreground—the figure of a European woman holding a child from an Indigenous background, serving as the emotional and symbolic focal point; Middle ground—natural or contextual elements (mountain slopes, wagons, vegetation) creating spatial depth; Background—the sky, typically symbolizing higher order or divine intervention.

Thus, Trevisani’s painting and the cited cinematic scenes are unified not only by the theme of maternal protection and the vulnerability of the child, but also by a shared visual rhetoric, in which mythology, history, and trauma interact through recurring compositional and symbolic strategies.

4. Themis Archetype: Where Justice Meets Humanity

FBI Special Agent Jane Banner, the female hero of Wind River, vividly embodies the archetype of the ancient Greek figure Themis, the goddess of justice. Her determination to restore justice and protect the vulnerable, despite her inexperience and the harsh circumstances she faces, makes her a strong and multifaceted character.

Themis, the goddess of justice and law, symbolizes the pursuit of balance and the protection of those whose rights have been violated (

Figure 7). Jane Banner takes on the investigation of the murder of a young woman of the Northern Arapaho tribe, despite her lack of familiarity with local realities and the hostile atmosphere of the reservation. Jane serves as a bridge between federal law enforcement and a local community that has long lost faith in the system (

Figure 8). She acts as a mediator, striving to understand and respect Indigenous traditions while seeking justice. Her deep concern for the victim’s fate, as well as her genuine desire to help the family and bring the perpetrators to justice, underscores her connection to Themis as a defender of the oppressed.

As an additional point, the film

Wind River, representing an under-examined neo-western genre that intertwines the past and the future, requires focused attention. The issues raised in this film are characterized as follows: “

Wind River shows the violent battle between the sexes (sexual abuse and femicide)… The sexually encoded gender struggle here is simultaneously shaped by racist tendencies and a latent class conflict… The Inner frontier in

Wind River addresses cultural, gender-political, class-political, racism-based and mythical aspects” (

Stiglegger 2022, p. 7).

Figure 7.

Justice (1750) by Pierre Hubert Subleyras.

Figure 7.

Justice (1750) by Pierre Hubert Subleyras.

Figure 8.

Jane Banner from Wind River (2017) directed by Taylor Sheridan, film frame.

Figure 8.

Jane Banner from Wind River (2017) directed by Taylor Sheridan, film frame.

A comparative analysis of Pierre Hubert Subleyras’s painting Justice (1750) and a still from the film Wind River reveals deep visual and conceptual parallels centered around the archetype of Themis—the embodiment of justice. Subleyras’s work, executed in the transitional style between late Baroque and early Neoclassicism, is characterized by compositional clarity, formal balance, and restrained expressiveness.

In both compositions, the central female figure—Justice in the painting and the protagonist in the film—is placed slightly off-center to the right, forming the primary axis of the visual structure. On the left side of Subleyras’s canvas, the composition is balanced by the traditional symbol of the scales of justice, signifying impartial judgment and equilibrium. In the cinematic still, this balancing function is fulfilled by the figure of the tribal police chief, who symbolically embodies the institutional apparatus of justice within the context of the reservation.

Both the painting and the film still share a dominant chromatic scheme based on pale blue and blue-white tones. These cool hues evoke a sense of detachment, clarity, and neutrality, all of which resonate with the ideals of objective and dispassionate judgment. In this visual lexicon, blue emerges as a metaphor for truth and rationality—free from emotional excess and emblematic of moral and cognitive lucidity.

The spatial organization in both cases is defined by openness and a lack of enclosures, metaphorically underscoring access to knowledge and transparency of legal processes. Subleyras situates Justice within a space marked by books and scholarly instruments—visual signifiers of theoretical jurisprudence. In Wind River, the protagonist stands within a medical examiner’s office—a locus of empirical knowledge where the cause of death is to be determined using scientific tools. The outcome of the forensic analysis becomes pivotal to the legal case, establishing a direct connection between knowledge and the pursuit of justice. Thus, both environments function as epistemological foundations for juridical authority, linking law to the domains of reason and evidence.

The facial expressions and bodily comportment of both female figures are marked by composure and contemplative stillness, emphasizing the intellectual and ethical dimensions of justice. Their features are devoid of emotional tension; gestures are minimal and measured. This inner equilibrium complements the recurring motif of the scales—not only as a symbol of legal balance, but also as an emblem of moral stability.

In sum, both Subleyras’s painting and the cinematic still from Wind River construct a coherent visual articulation of the Themis archetype. Through the convergence of female presence, chromatic austerity, spatial openness, and signifiers of rational knowledge, they convey justice as a disciplined, morally grounded, and epistemologically informed force.

5. Hebe Archetype: Eternal Youth and Innocence

The female hero of

The Last of the Mohicans, Alice Munro, embodies the image of the ancient Greek goddess Hebe (

Figure 9), the goddess of youth, through her purity, innocence, and tragic departure, which leaves her forever young in memory. Alice Munro appears in the film as a fragile and delicate figure, untainted by the cruelty of the surrounding world. She is neither a warrior nor an active participant in the conflict, yet her very presence highlights the contrast between the purity of youth and the harsh reality of war.

Just as Hebe untouched by time in mythology, Alice is remembered by the audience in the same way—light, dreamy, and distant from the violence around her (

Figure 10). Furthermore, Hebe is associated with renewal and new beginnings, as her name is linked to spring and blossoming. In this sense, although Alice does not undergo a physical rebirth, she becomes a symbol of undying memory—of purity and luminous naivety that cannot survive in a world of cruelty but continue to exist in remembrance, just like Hebe’s eternal youth. Her mutual understanding with Uncas symbolizes the harmony that can exist between two different cultures—the British and the Mohican. Although their story is tragic, it highlights Alice’s desire for unity, even in a world torn apart by conflict.

Figure 9.

Portrait of Anne Pitt as Hebe (1792) by Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun.

Figure 9.

Portrait of Anne Pitt as Hebe (1792) by Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun.

Figure 10.

Alice Munro from The Last of the Mohicans (1992) directed by Michael Mann, film frame.

Figure 10.

Alice Munro from The Last of the Mohicans (1992) directed by Michael Mann, film frame.

The painting Portrait of Anne Pitt as Hebe (1792), by Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, exemplifies the refined aesthetic of late Neoclassicism, while simultaneously integrating elements of Romanticism and Sentimentalism. This stylistic synthesis is particularly appropriate for the portrayal of Hebe, the goddess of youth, who embodies idealized grace, celestial purity, and ephemeral beauty. Vigée Le Brun, one of the most accomplished portraitists of her time, harmoniously combines the formal compositional rigor of classicism with the emotional delicacy and atmospheric softness characteristic of the Romantic sensibility at the turn of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

A similar visual logic is evident in a film still from The Last of the Mohicans (1992), where the character Alice Munro is depicted within a comparable iconographic and spatial framework. In both compositions, the female figure occupies the central position, adhering to the academic conventions of classical portraiture. The spatial arrangement follows the canonical tripartite structure typical of classical landscapes and portraiture: a warm-toned foreground, a green middle ground, and a cool blue background.

In Vigée Le Brun’s painting, the foreground features Hebe in grey-brown drapery, accompanied by the eagle of Zeus—a symbolic attribute. The middle ground is marked by a table with an amphora, alluding to divine nectar, while the background fades into a serene, grey-blue sky that dissolves contours and contributes to the overall sense of transcendence and weightlessness. In the film still, the foreground similarly presents Alice in cream-colored garments softly illuminated by natural light; the middle ground consists of a green, sloping hillside; and the background opens into a vast blue sky, evoking Romantic notions of the sublime and the infinite.

A defining feature of both images is their sense of airiness—a visual and symbolic element that conveys fragility, elevation, and metaphysical ambiguity. In the painting, this is achieved through subtle modeling, diffused lighting, and delicate highlights on fabric and hair. In the cinematic still, the atmosphere is made tangible: Alice’s loose, blonde locks emphasize a moment of transition, a Romantic liminality poised between life and death, the earthly and the ethereal. This treatment aligns with the Romantic ideal of the feminine figure as a liminal presence, suspended between material reality and mythic abstraction.

The color palette in both the painting and the film still is composed of soft, desaturated tones—greys, creams, and pale blues—minimizing contrast and heightening the emotional tone of vulnerability, mystery, and suspension. This chromatic restraint reinforces the impression of weightless harmony, allowing the female figure to appear both anchored and dissolving within the surrounding space.

Thus, both the painting and the cinematic composition articulate an aesthetic of idealized elevation, in which the formal perfection of classicism coexists with Romantic expressiveness and inner tension. These visual works engage in an intermedial dialogue, evoking the archetypal image of Hebe.

6. Clio Archetype: Revealing the Forgotten Truths of History

The female hero of

The Last of the Dogmen, Professor Lillian Diane “L.D.” Sloan, a researcher and archaeologist, vividly embodies the archetype of Clio, the muse of history (

Figure 11). Her character and actions demonstrate her deep connection to history, her drive to uncover the unknown, and her role as a mediator between two cultures.

As an archaeologist and investigator, Lillian Sloan personifies Clio through her passion for preserving and studying the past. She seeks to uncover the lost secrets of vanished civilizations, directly reflecting Clio’s mission—to safeguard the memory of great events and peoples (

Figure 12). Lillian views archaeology as a calling that enhances humanity’s understanding of its own history, and her work in the film is dedicated to restoring historical truth.

Her knowledge of Indigenous cultures, respect for their traditions, and empathy for the tragic chapters of their history emphasize her commitment not just to exploration, but to the preservation of a disappearing legacy. Like Clio, Lillian becomes a guardian of memory and culture, ensuring that the voices of the past are heard. In classical iconography, Clio’s attributes include not only books but also a trumpet—a symbol of fame. Lillian sets out to uncover the unknown, yet when faced with the choice between glory and the preservation of the discovered culture, she chooses the last. She chooses cultural preservation and peace.

In the film, Lillian serves as a bridge between the Indigenous people and her companion Lewis Gates, acting as both translator and cultural mediator. She does not merely translate language; she helps her companion grasp the customs and worldview of the Native people. Her role as a mediator highlights her respect for both cultures and her dedication to fostering harmony in communication.

Figure 11.

Clio, Muse of History (1800) by Charles Meynier.

Figure 11.

Clio, Muse of History (1800) by Charles Meynier.

Figure 12.

Professor Lillian Sloan from Last of the Dogmen (1995) directed by Tab Murphy, film frame.

Figure 12.

Professor Lillian Sloan from Last of the Dogmen (1995) directed by Tab Murphy, film frame.

Charles Meynier (1768–1832) was a prominent figure in the late Neoclassical and Empire (Empire style) school, working in a tradition defined by mythological and historical narratives. His Clio, Muse of History (1800), one of a commissioned cycle of Muses, exemplifies his synthesis of Classical compositional discipline with allegorical iconography.

A key structural device in both Meynier’s painting and the selected film still is the mise-en-scène: the spatial organization of figures and props that creates narrative resonance. In the cinematic still, the setting is that of an archaeological excavation: a wheelbarrow laden with earth, wooden crates for relics, documents, and a camera—tools for uncovering and preserving the past. Correspondingly, Meynier stages a form of excavation on his canvas: in the foreground, a protruding stone block carved with a battle scene, partially buried—symbolic diggings into antiquity, literally uncovered by the muse. This is a form of bas-relief revelation, revealing historical layers.

The front plane in both works signals the excavation motif: in the painting, Clio stands beside this sculptural fragment; in the film, the protagonist stands amidst freshly turned earth. Clio is distinguished by her laurel wreath, a classical crown of poetic and historical authority. In the film still, the principal investigator among the three characters is the only one wearing a hat, marking her as the focal subject—a modern analogue to the classical crown.

Clio holds a tablet—likely metal (copper)—and stylus, emblematic of her role in recording history. In the film, the archaeologist holds a notebook and pen, a contemporary counterpart to the ancient writing tool. Both instruments denote authorship, documentation, and epistemic agency.

In the middle distance of the painting, Meynier situates a small pyramid—an allusion to Egyptological discovery. In the film, the same triangular projection of soil mimics this pyramid shape, reiterating the excavation’s link to ancient civilizations.

Both central female figures have dark hair, a visual consonance that reinforces their thematic continuity. The color palette also aligns closely: a contrapuntal interplay between warm yellows/ochres (earth, sand, broken masonry) and cooler blues (sky, tools, distant motifs). The blue accents—present in drapery or sky—serve a symbolic purpose: they invoke intellectual clarity, heritage, and the historical imagination, anchoring the earthy excavation in a broader archeological poetics.

Taken together, these compositional strategies reveal that the film consciously evokes the archetype of Clio—the Muse who preserves collective memory—reframed within a modern archaeological context. The film’s mise-en-scène thus performs an intermedial transposition of Classical mythological archetypes into contemporary cinematic discourse, affirming the protagonist as a living agent of history’s recovery.

7. Nemesis Archetype: The Wrath That Restores Balance

Nemesis, in ancient Greek mythology, personified retributive justice, restoring the balance that had been disrupted. Her mission was to punish those who had committed evil, especially when driven by arrogance or cruelty, thereby shattering the harmony of existence (

Figure 13).

Clare from

The Nightingale (2018), having endured the tragedy of her family’s murder and the destruction of her life, becomes the embodiment of wrath and vengeance (

Figure 14). She seeks justice, aiming to avenge the shattered world whose balance was disturbed by the atrocities of British soldiers. Her actions are directed toward restoring equilibrium by eliminating those responsible for the wrongdoing. The justice of Nemesis is cold and relentless. Clare assumes this role, yet her journey is also filled with inner conflict, as rage and vengeance begin to threaten her humanity.

A crucial aspect of her journey is her mediation with Billy, a local Aboriginal guide, which becomes an essential part of her internal transformation. Their complex relationship begins with distrust but gradually evolves into an alliance built on mutual respect and a shared pursuit of justice. Billy helps Clare realize that her struggle is not merely an act of personal revenge but part of a much larger conflict involving the systemic brutality of British colonizers against Indigenous peoples. This understanding deepens her path beyond simple vengeance.

Claire experiences two powerful instincts: the maternal instinct and the instinct of vengeance. These are universal instincts, characteristic of all humans regardless of nationality, continent or era. In the film, an Aboriginal woman appears, who is captured and raped by English soldiers. During the assault, she loses sight of her son. Her emotional turmoil and despair reveal that the maternal instinct is universal across all cultures. The connection between instincts and archetypes was elaborated by Jung as follows: “What we properly call instincts are physiological urges, and are perceived by the senses. But at the same time, they also manifest themselves in fantasies and often reveal their presence only by symbolic images. These manifestations are what I call the archetypes. They are without known origin; and they reproduce themselves in any time or in any part of the world —even where transmission by direct descent or “cross fertilization” through migration must be ruled out” (

Jung 1964, p. 69).

Clare Carroll embodies the fierce retribution of Nemesis, while her mediation with Billy reveals her capacity for transformation, allowing her to grasp the full scale of injustice and find meaning in her struggle beyond personal revenge. As she interacts with Billy and gains awareness of the broader oppression, her journey increasingly aligns with the role of Nemesis—a retributive force seeking to restore a broken equilibrium on a national scale. “When all the women are raped, when all the men and babies are killed, what will you do then, Lieutenant?”—Claire asks the killer of her family.

Figure 13.

Justice and Divine Vengeance Pursuing Crime (1808) by Pierre-Paul Prud’hon.

Figure 13.

Justice and Divine Vengeance Pursuing Crime (1808) by Pierre-Paul Prud’hon.

Figure 14.

Clare Carroll from The Nightingale (2018) directed by Jennifer Kent, film frame.

Figure 14.

Clare Carroll from The Nightingale (2018) directed by Jennifer Kent, film frame.

The painting Justice and Divine Vengeance Pursuing Crime (1808) by Pierre-Paul Prud’hon and a still from the film The Nightingale both illustrate a shared visual and conceptual archetype—that of Nemesis, the embodiment of retributive justice. Both representations are situated within a twilight setting, where the ambiguity of light heightens a sense of unease. The semi-darkness does not obscure the events but instead dramatizes them, creating an atmosphere of fatal inevitability.

What unites both visual compositions is a prevailing mood of extreme tension and inescapable doom. The twilight environment amplifies a sense of anxious uncertainty, imbuing the scenes with mystery and mythopoetic resonance. The interplay of light and shadow underscores the tragic dimension of the narrative and brings the imagery closer to symbolic abstraction, aligning with the aesthetic principles of Romanticism.

Of particular note is the dynamic structure of both compositions. Each is rendered in a wide shot that captures figures in motion—billowing garments, rising shadows, and directional gestures intensify the sensation of a vortex of action. Prud’hon’s canvas, despite its Napoleonic Empire context, exhibits a remarkable cinematic quality: it eschews pathos, pose, and theatrical rigidity in favor of an almost documentary immediacy. Decorative excess and narrative redundancy are eliminated; everything is subordinated to a unified emotional and narrative drive.

Both works display a pronounced cinematic sensibility: wide framing, absence of posturing, a charged kinetic environment. In Prud’hon’s work, this takes the form of a whirlwind of bodies and drapery, largely freed from academic stillness. In The Nightingale, the composition is meticulously calibrated, with every movement motivated by internal narrative tension rather than external expressiveness.

At the center of each composition stands a female figure as the agent of punishment—an incarnation of Nemesis. In Prud’hon’s painting, Divine Vengeance wields a sword in pursuit of the criminal, symbolizing the inevitability of retribution. In The Nightingale, the protagonist is armed with a firearm; her figure is austere, clad in dark garments that accentuate her somber resolve, further emphasized by the absence of adornment or symbolic props. Both figures trace their origins to the archetype of punitive force, according to a higher, almost transcendent law of justice.

Thus, both the painting and the cinematic still articulate the Nemesis archetype through elemental dynamism, twilight imagery, and emotional intensity, deliberately avoiding theatricality. In both instances, the viewer is confronted with the moment at which justice has already been set in motion—an unstoppable force.

8. Artemis Archetype: Solitude and Independence

Artemis is the goddess of hunting, virginity, and freedom, as well as the protector of those who choose solitude and independence (

Figure 15). This archetype closely aligns with the character of a real historical figure Josephine Monaghan from

The Ballad of Little Jo directed by Maggie Greenwald, who is forced to abandon the traditional female role and assume a male name and identity in order to survive (

Figure 16).

Like Artemis, Josephine refuses to conform to societal expectations and norms. She leaves behind her familiar world and chooses to build a new life in the unforgiving environment of the Wild West, where women could not expect respect or protection. Just as Artemis protected those under her care, Josephine takes on responsibility for others. Despite the dangers surrounding her, she becomes part of the community and helps those who depend on her. Artemis was known for her rejection of marriage and submission. Similarly, Josephine conceals her femininity, rejecting traditional gender roles and the expectations imposed upon her. In the film, Josephine learns to shoot proficiently, a skill essential for her survival. This mirrors the image of Artemis, renowned as a skilled archer. Mastering the use of weapons allows Josephine to protect herself and gain the respect of those around her in a world where power and survival depend on physical strength.

Therefore, Josephine, like Artemis, represents freedom and independence, breaking traditional gender norms. Her story serves as an inspiring example of strength, transformation, and defiance against injustice, echoing the great archetypes of ancient mythology and universal human psychology.

Figure 15.

Diana (1881) by Walter T. Crane, fragment.

Figure 15.

Diana (1881) by Walter T. Crane, fragment.

Figure 16.

Josephine Monaghan from The Ballad of Little Jo (1993) directed by Maggie Greenwald, film frame.

Figure 16.

Josephine Monaghan from The Ballad of Little Jo (1993) directed by Maggie Greenwald, film frame.

A comparative analysis of Walter Crane’s painting Diana and a film still from The Ballad of Little Jo reveals a shared visual logic rooted in Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics. Both images are distinguished by an intense focus on natural detail, a high degree of realism, and a densely articulated pictorial space. The compositions employ asymmetrical balance: the central figure is positioned off-center, creating a dynamic visual tension. Rather than being organized around vertical and horizontal axes, both images privilege diagonal structures and sinuous lines, disrupting geometric regularity and enhancing the organic quality of the scene.

In both works, the natural environment plays a dominant role. The ground—covered with grass and wild flora—occupies a substantial portion of the pictorial field, rendered with meticulous accuracy. There is no atmospheric perspective or photographic blur: depth is achieved through the even distribution of finely rendered details, a hallmark of Pre-Raphaelite technique.

The color palettes of both images are remarkably similar, dominated by warm earthy tones—ochres, beiges, and muted greens—that reinforce the unity between figure and landscape. Symbolically significant is the presence of sheep in the film still, animals frequently depicted in Pre-Raphaelite and pastoral imagery as emblems of innocence, pastoral harmony, or sacrificial undertones.

The female protagonists in both images are portrayed in motion, rather than posed in a static, classical manner. The face of the film’s protagonist, Josephine, is turned away, partially obscured—mirroring the way Diana’s face is not the compositional or narrative focus. This displacement reinforces the sense of inner autonomy and withdrawal from the viewer’s gaze.

The symbolic attributes further invite comparison: Diana is depicted with a hunting horn, a traditional emblem of wilderness, independence, and feminine agency, closely associated with the archetype of Artemis, the virgin huntress. Josephine holds a staff, which may be read as a symbol of pilgrimage, exile, or moral fortitude, and within the context of the film, as an emblem of masculine disguise and self-defense. Both objects are rounded in form, reinforcing their symbolic and formal analogy.

Ultimately, the two images engage in a mirror-like visual dialogue—as if one reflects or echoes the other—suggesting a deeper archetypal connection. The cinematic image thus enacts a modern reinterpretation of the Artemis archetype, presenting the female figure as sovereign, in motion, and inextricably linked to the natural world.

9. Persephone Archetype: Bridging Two Worlds and Balancing Opposites

The female hero of the film

Woman Walks Ahead, an artist Catherine Weldon (a historical figure), embodies the Persephone archetype, the goddess of transition and rebirth (

Figure 17). Her journey to Dakota Territory, her desire to understand their world, and her collaboration with Chief Sitting Bull make her a figure that bridges two opposing worlds—the American colonizers and the Sioux people. Her role as a mediator, a creator of a new reality, and a symbol of transformation highlights her profound inner journey and social mission.

The protagonist’s courage and willpower allude to Carol S. Pearson’s theory: “Persephone’s ease in moving back and forth between the worlds and the seasons can be a model for our gaining ease in shifting between multiple roles and adjusting to new life stages that require different things from us” (

Pearson 2015, p. 171).

Like Persephone, who represents the transition between two worlds, Catherine steps into the unfamiliar world of the Native American reservation, seeking to understand and illuminate the tragedy of a people being displaced and destroyed (

Figure 18). Her transition into this reality is tied to personal transformation and the discovery of a new truth. She becomes a connecting thread between the outside world and Native American culture, bravely delving into their struggles and risking her reputation and her life to defend their rights.

Catherine is not only an artist but also a mediator. Her relationship with Sitting Bull goes beyond that of an artist and a model—she becomes his ally, assistant, and friend, facilitating dialogue between Indigenous people and the outside world. Catherine Weldon embodies Persephone because she enters a world unfamiliar to her, yet in the process of this transition, she discovers new meanings and helps another people find hope.

Figure 17.

Proserpine (1882) Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Figure 17.

Proserpine (1882) Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Figure 18.

Catherine Weldon from Woman Walks Ahead (2017) directed by Susanna White.

Figure 18.

Catherine Weldon from Woman Walks Ahead (2017) directed by Susanna White.

Proserpine (1882) is a renowned painting by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a central figure in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood—an artistic movement founded in 1848 that sought to revive the spiritual and aesthetic values of early Italian Renaissance art. This work is among the most symbolically charged of Rossetti’s late oeuvre. In the figure of Proserpine (the Roman counterpart of the Greek Persephone), he articulates a state of existential duality: the tension between two worlds—life and death, freedom and captivity, surface and depth.

A film still from Woman Walks Ahead (2017) reveals striking visual and symbolic parallels to Rossetti’s composition. The protagonist, Catherine Weldon, is presented in a pose evocative of Pre-Raphaelite portraiture: her face is turned three-quarters, recalling compositional conventions of the early Renaissance and the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic, which favored introspective, psychologically resonant angles that emphasize emotional interiority.

Both representations foreground long, wavy, reddish hair, which in Western iconography often connotes singularity, emotional intensity, and inner conflict. In each image, attention is given to the textural rendering of fabric—Rossetti achieves this through painterly density and tonal modulation, while the film employs directional lighting and material texture to create depth and movement within the still.

The mise-en-scène of the film further enhances this connection. The interior draped in fabric, framing the character like theatrical curtains, evokes the stylistic tendencies of Symbolist and late Romantic painting, where the boundary between space and psyche is intentionally blurred. This theatricality simultaneously isolates and sanctifies the figure, transforming her into a mythic or ritualistic presence.

The central symbolic correspondence between the two figures lies in their attributes: in Rossetti’s painting, Proserpine holds a pomegranate, the classical symbol of her bond to the underworld and her inevitable return to it—an emblem of liminality and loss. In the film, Catherine wears a pendant in the shape of an eagle, associated with the culture of the Sioux people, with whom she aligns herself. In Sioux cosmology, the eagle represents spiritual power, connection to the heavens, and transcendent wisdom, marking the pendant as a sign of her affiliation with another world—not only geographically or culturally, but spiritually and existentially.

The eagle is also a significant symbol in ancient Greek mythology, embodying celestial power, divine authority, and the sovereign will of Zeus. As his sacred animal and messenger, the eagle functioned as a conduit between the mortal and divine realms. Its presence further underscores the mythological resonance in Woman Walks Ahead, evoking a symbolic alignment with classical imagery and reinforcing the film’s connection to Greek archetypes.

Both women’s gazes convey melancholy, estrangement, and a sense of fated stillness. It is not active suffering, but a state of suspended being—a psychological and symbolic in-betweenness. Thus, the Persephone archetype, as the feminine figure caught between worlds, sacrifice, and transformation, is transposed onto the cinematic image of Catherine.

Through gesture, gaze, drapery, and light, both visual structures articulate a mythic condition of feminine liminality. In this sense, cinema enters into an intermedial dialogue with Pre-Raphaelite painting, reactivating the Persephone archetype within a contemporary visual and cultural framework.

10. Aphrodite Archetype: Uniting Love and Sensuality

The female heroes Stands With A Fist from

Dances with Wolves directed by Kevin Costner (1990) and Cora Munro from

The Last of the Mohicans directed by Michael Mann (1992) embody the Aphrodite archetype, as their characters are infused with themes of love, inner passion, emotional depth, and uniting force (

Figure 19). These are female heroes through whom love becomes a force of change, inspiration, and the overcoming of boundaries.

The female hero of

Dances with Wolves, Stands With A Fist, is the white adoptive daughter of the Kicking Bird—shaman of the tribe. Her love for John Dunbar becomes the connecting thread between two worlds—the world of her people and the world of the “outsider” (

Figure 20). This reflects an aspect of Aphrodite as a goddess capable of uniting and transforming through love. Her communicative nature, tolerance, and emotional depth make her a central figure around whom change unfolds. She also serves as a mediator between two cultures, acting as a translator.

Like Aphrodite, Cora possesses a captivating inner strength that allows her to bridge the gap between two opposing worlds—the British colonial society and the Indigenous cultures of North America, familiar civilization frames and unknown wild nature (

Figure 21). She is not a passive observer but an active participant in the unfolding events, demonstrating resilience, compassion, and an openness to different ways of life. Her attraction to Nathaniel “Hawkeye” Poe, is not merely a romantic connection but a symbolic unification of two contrasting cultures. Just as Aphrodite uses love as a force of harmony and reconciliation, Cora’s presence fosters understanding and connection in a world marked by conflict and division.

Figure 19.

Venus and Anchises (1889 or 1890) by William Blake Richmond.

Figure 19.

Venus and Anchises (1889 or 1890) by William Blake Richmond.

Figure 20.

Stands With A Fist from Dances with Wolves (1990) directed by Kevin Costner, film frame.

Figure 20.

Stands With A Fist from Dances with Wolves (1990) directed by Kevin Costner, film frame.

Figure 21.

Cora Munro from The Last of the Mohicans (1992) directed by Michael Mann, film frame.

Figure 21.

Cora Munro from The Last of the Mohicans (1992) directed by Michael Mann, film frame.

As a visual reference for the Aphrodite archetype, William Blake Richmond’s painting

Venus and Anchises (1889 or 1890) was chosen (see

Figure 7). In this work, Venus (the Roman Aphrodite) is depicted not only as a symbol of love and sensuality but also as a mediator between the mortal and divine realms. Her influence is exercised not through aggression but through beauty, physical allure, and emotional power. The mythological narrative of Anchises—a mortal favored by the goddess—illustrates divine intervention where love serves as a channel to transcend the boundaries between earthly and celestial worlds. Thus, the scene embodies not only a romantic union but also a broader idea of harmony, fusion, and mutual permeation of two worlds, with Aphrodite playing the initiating and reconciliatory role.

This painting belongs to the aesthetics dominant in the late Neo-Pre-Raphaelite tradition, deeply rooted in the principles of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. This style is characterized by meticulous attention to detail, painterly naturalism, and an idealization of the natural world. Richmond inherits the Pre-Raphaelite emphasis on microscopic study of nature, demonstrated in the detailed rendering of every leaf, flower, and blade of grass—an approach traditionally associated with Pre-Raphaelite practices aimed at precise depiction of the surrounding reality.

Parallel to this painterly tradition, the film stills from Dances with Wolves and The Last of the Mohicans exemplify the same principle of detailed natural representation, where every element—from grass to water surfaces—is captured with high visual accuracy. In Dances with Wolves, a multi-layered natural composition can be observed: tall grass symbolizes solitude and connection to the earth; cottonwood fluff gently falling from above adds a sense of movement and ephemerality; the water surface reflects horses—symbols of freedom, will, and unrestrained motion—serving as a metaphor for the life journey.

The animal world holds special symbolic significance in both visual contexts. The image of lions, present in Richmond’s painting, is interpreted as a symbol of Aphrodite’s divine origin, linking the mythological context to the ideas of power and grandeur. Doves function as symbols of peace and the establishment of communication between worlds and beings. Meanwhile, sparrows disappearing from view signify the fading of the mundane, inviting immersion into higher spiritual realms.

Compositionally, both works consistently feature two central figures—male and female—dressed in loose, flowing garments that emphasize naturalness and harmony with nature. In Dances with Wolves, the female figure is depicted in cream-yellow tones, and the male in burgundy, which precisely corresponds to the color scheme of Richmond’s painting. This warm color palette, dominated by beige, yellow, and green hues, contributes to a light and airy atmosphere. Particular attention is given to the clarity of the background, which remains sharp rather than blurred, thereby complementing and enhancing the overall compositional harmony.

Thus, a profound connection emerges between the painterly and cinematic imagery, where the Aphrodite archetype embodied in Richmond’s painting permeates the visual language of both films. This testifies to the continuity and universality of the mythological symbol, actualized in both traditional painting and contemporary cinema.

11. Demeter Archetype: A Mother’s Heart Between Despair and Hope

Rosalee Quaid, the female hero of the film

Hostiles, embodies the Demeter archetype, the goddess of motherhood and fertility, through her profound grief for her murdered children and her determination to preserve her connection to maternal love despite the horrors she has endured. Like Demeter mourning the loss of her daughter Persephone (

Figure 22), Rosalee experiences deep tragedy after the death of her children (

Figure 23). Her maternal soul remains alive despite her pain, and this grief drives her throughout the story. Her suffering does not lead to bitterness; on the contrary, it highlights her incredible strength as a mother who continues to seek love and care despite her loss.

According to Carol S. Pearson’s conception: “The challenge of the Demeter archetype requires any of us, but particularly those who have experienced loss, to resist pulling back in fear from trusting the love we have for one another and instead to love more fiercely and fully” (

Pearson 2015, p. 28).

Rosalee reconciles with her new role. Just as Demeter found the strength to live by reaching a compromise in the story of Persephone, Rosalee joins a shared mission, enduring all trials and hardships along the way, and ultimately adopts a Cheyenne orphan boy. This symbolizes her ability to heal her maternal heart and offer love to someone in need.

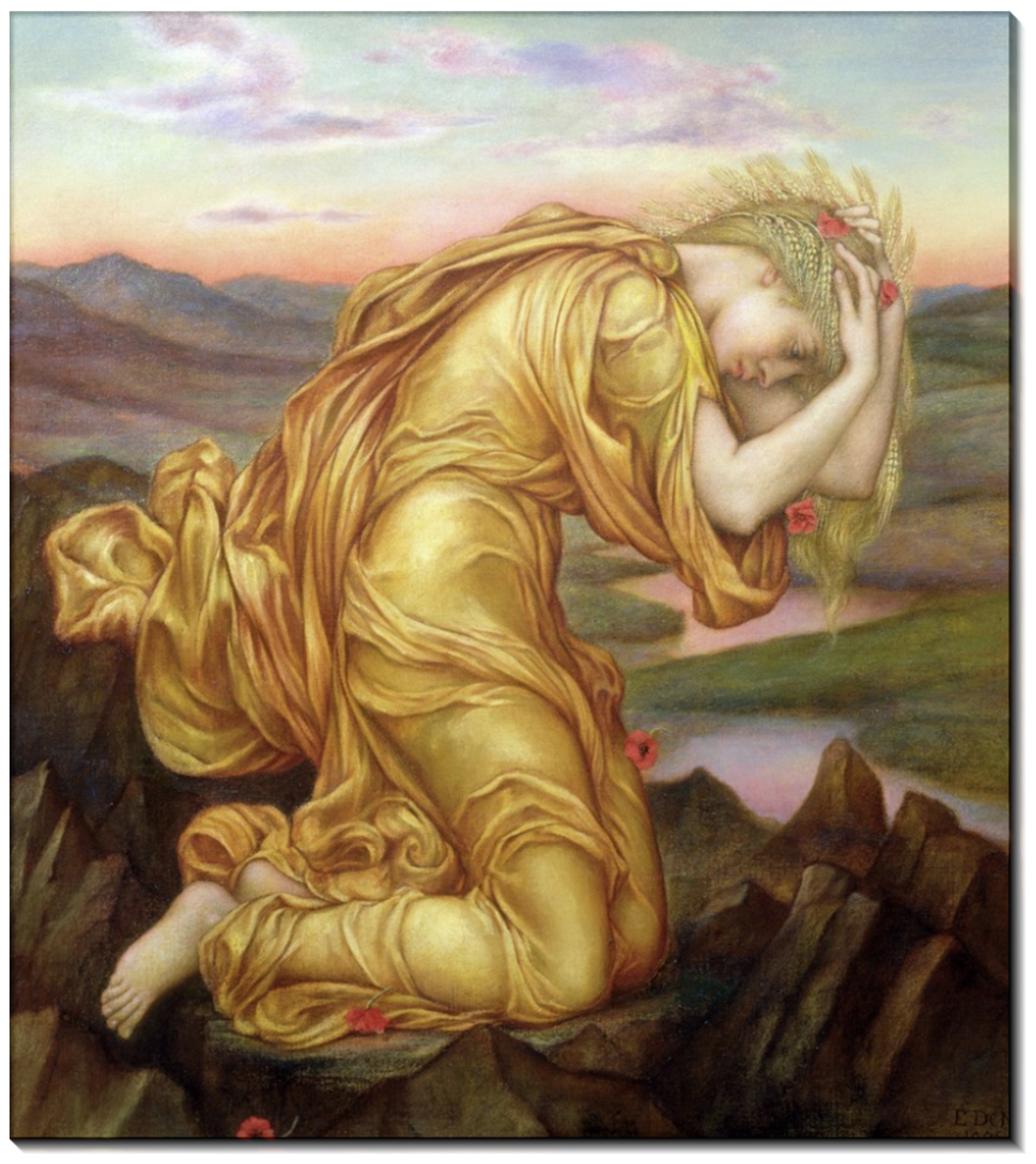

Figure 22.

Demeter Mourning for Persephone (1906) by Evelyn De Morgan.

Figure 22.

Demeter Mourning for Persephone (1906) by Evelyn De Morgan.

Figure 23.

Rosalee Quaid from Hostiles (2017) directed by Scott Cooper, film frame.

Figure 23.

Rosalee Quaid from Hostiles (2017) directed by Scott Cooper, film frame.

In the painting Demeter Mourning for Persephone (1906) by Evelyn De Morgan—a British artist associated with the later phase of the Pre-Raphaelite tradition—and in a still from the film Hostiles, a similar emotional motif is visualized: the female figure in a state of mourning. In both images, the figure’s posture is inclined toward the earth; the bodily expression conveys loss, psychological weight, and internal isolation.

Both female figures have light, wheat-colored hair—a hue traditionally associated with fertility and agrarian deities. In De Morgan’s work, Demeter’s hair is literally interwoven with ears of grain, reinforcing the mythological reference and emphasizing her connection to the earth as both a source of life and suffering.

The color palette in both compositions is rendered in warm, earthy tones—ochres and soft beige-pinks—intensifying the organic relationship between the body, the landscape, and the protagonist’s emotional state. Particular attention is given to the depiction of drapery: the fabric is painted with naturalistic precision, and its folds convey not only materiality but also internal tension. Here, fabric functions as a symbol of vulnerability, the weight of grief, and time itself—as something fluid, soft, and at the same time enveloping tragedy.

Vivid color accents play a significant semantic role in both compositions. In De Morgan’s painting, these are poppies—traditional symbols of sleep, death, and transition, associated with the cult of Demeter. In the film, a similar tone appears in the still as a trace of the tragedy that befell a young woman. In both cases, the bright color marks a point of intersection between the physical and the symbolic: pain, memory, and irreversibility.

Both scenes project an archetypal image—the mourning mother, the goddess, the woman at the threshold of transformation. Painting and cinema here operate as parallel media of visual mythopoesis.

12. Conclusions

As a result of a diachronic and comparative visual analysis of European painting from the late 17th to the early 19th centuries and Western films of the 20th and 21st centuries, nine archetypes of the European woman as a cultural mediator were identified. These archetypes correspond to the figures of nine goddesses of the ancient Greek pantheon. Visually encoded in the female characters depicted by artists working within the stylistic frameworks of Baroque, Classicism, Empire style, Sentimentalism, Neoclassicism, Romanticism, and the Pre-Raphaelite movement, these archetypes have been transposed into the cinematic language of the Western genre—both American and Australian.

An evolution of visual codes and representational strategies can be traced across these historical and stylistic periods. Baroque painting is marked by dramatic tension, strong chiaroscuro, and emotional contrasts. Classicism introduces compositional clarity, rational structure, and idealized restraint rooted in antiquity. Empire style elevates the female figure to the level of state allegory, interweaving visual signifiers of power and heroism. Sentimentalism emphasizes intimacy, emotional authenticity, and moral virtue. Neoclassicism continues the classical tradition, reinforcing harmony and compositional balance. Romanticism brings movement, existential tension, and expressive dynamism. Finally, the Pre-Raphaelites revive medieval and natural motifs, embracing decorative detail and imbuing the female figure with mysticism and symbolic depth.

The analysis reveals that archetypal representations of women in the Western genre retain visual and semantic continuity with classical European painting. This continuity manifests in frame composition, mise-en-scène, color palette, light and spatial treatment, and the recurrent use of iconographic elements consistent with academic and classical traditions. While Western films reinterpret these archetypes within new historical and cultural contexts, they preserve their essential function: the female character becomes a mediating figure, resolving conflicts between cultures, value systems, and social roles. In this way, archetypes operate not only as narrative structures, but as timeless visual codes embedded in the collective unconscious (in Jungian terms), surfacing independently of the creator’s conscious intention.

The comparative study of painting and cinema affirms that visual language, both in classical art and film, continues the tradition of cultural representation through archetype. In this context, the woman is not merely a character, but a semiotic figure—a symbol, a bearer of meaning—whose role within the cultural field transcends conventional narrative functions. Her presence in the Western genre not only reinforces the dramatic structure but also acts as a mediator of historical memory and cultural transformation.

Thus, the visual correspondences between painting and cinema confirm the transcultural and transmedial nature of archetypes—their ability to adapt to diverse aesthetic systems while retaining fundamental significance within the structure of visual expression.