Shamans, Portals, and Water Babies: Southern Paiute Mirrored Landscapes in Southern Nevada

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Indigenous Cultural Landscapes

Cultural groups socially construct landscapes as reflections of themselves. In the process, the social, cultural, and natural environments are meshed and become part of the shared symbols and beliefs of members of the groups. Thus, the natural environment and changes in it take on different meanings depending on the social and cultural symbols affiliated with it.

4. Natural Setting

4.1. White River Ecoscape

4.2. The Delamar Valley Dry Lake

5. Special Features

6. Ceremony at Delamar Valley

7. Delamar Valley Pilgrimage

7.1. Point of Rocks

7.2. Rock Shelter

7.3. Volcanic Ridge with Storied Rocks

7.3.1. Water Babies

7.3.2. Mountain Sheep Peckings

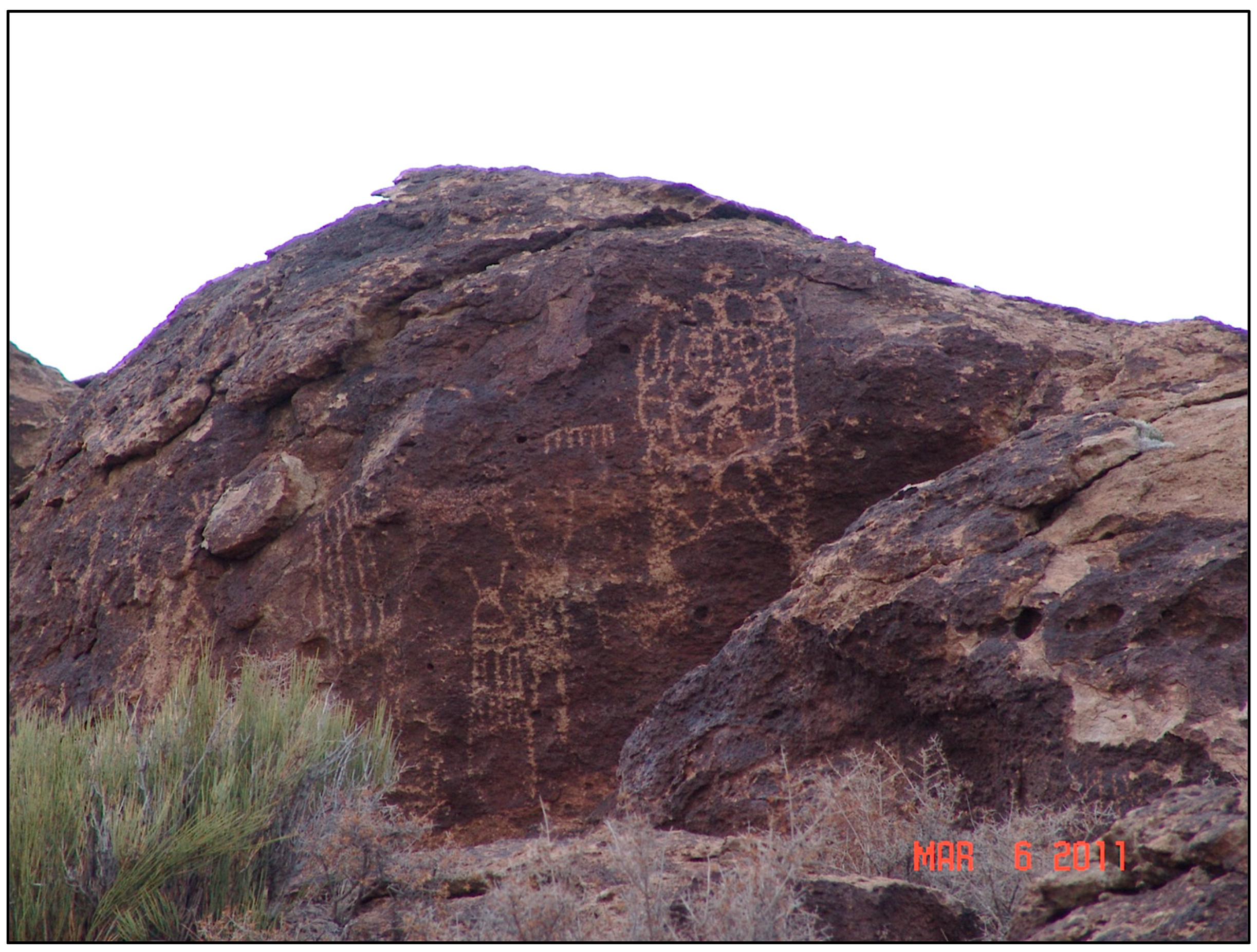

7.3.3. Transformed Shaman Peckings

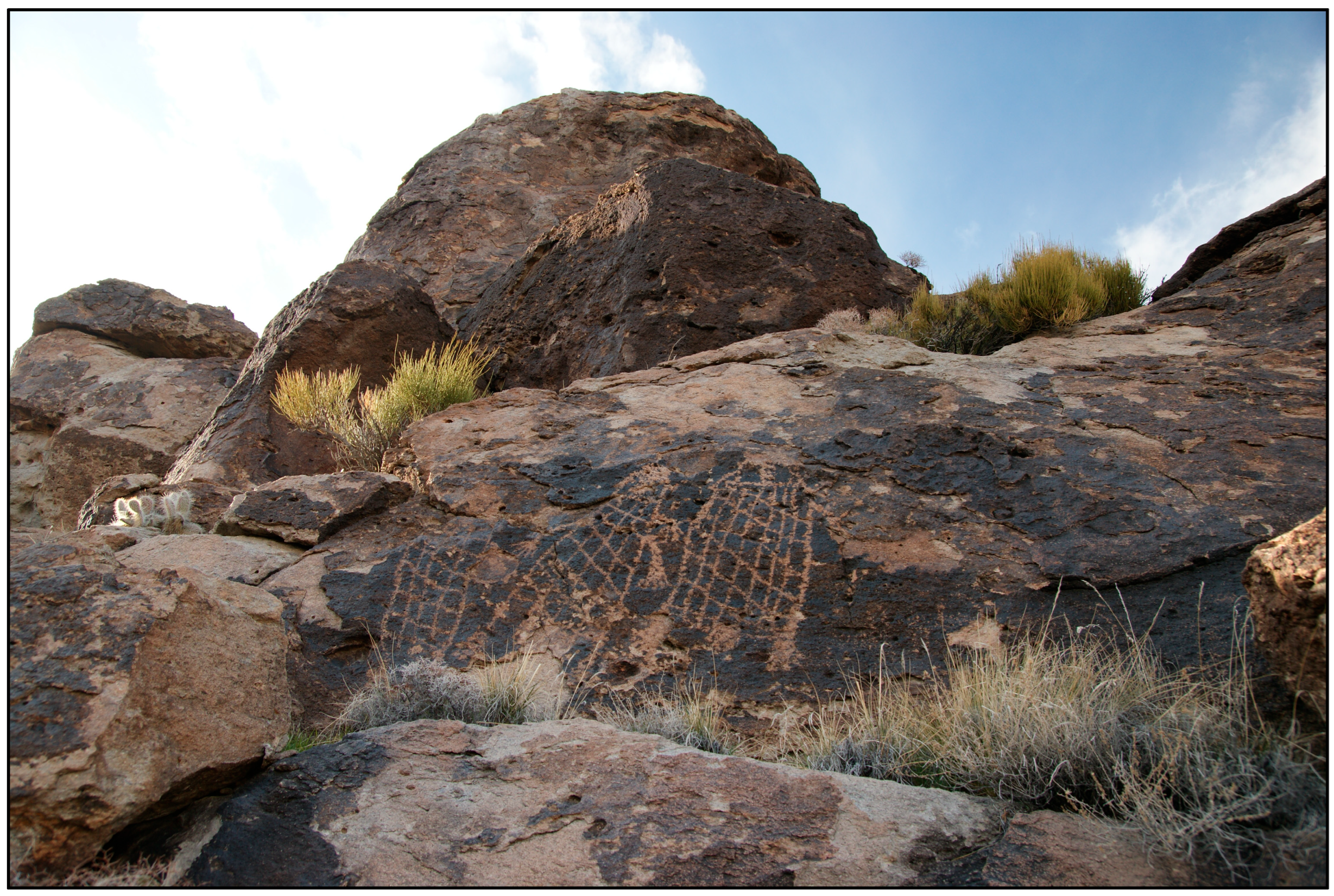

7.3.4. Ocean Woman’s Net

7.3.5. Turtle Butte

We’re here at the location where we found eight doctors or images that have the water baby hands: they’re all on one panel. They’re all looking over the entire valley. There is one that has two distinctive dark eyes in the middle. It’s very intriguing because it’s meant for you either as you come up or go down, you find different things. And for this panel I found the way that they may have gotten up here. We say the little people are the ones who make these, and they are able to get up here and all over. But this is definitely probably the biggest concentration of these kinds of things that I’ve seen in probably one of the most powerful spots in this little area where people came. They had to come here to gather to bring all that power to this one place. It’s a very centered place within this whole valley and probably within the belief of Paiute people as well.

I was just thinking about this area here that has the different drawings, and there are differences between the drawings and images that are here. The variations of the water babies and the power come from this place. Along time ago, Indian people would come to a place like this, and they would bring their own medicine, their own doctors, their own images, this would be a place where people would come to gather. So, the one place where there were the eight images of the medicine men, it was a place where people would have to come to keep the balance in the area because if not then things start going crazy. This is a very interesting location because although it’s a long hill, it’s only concentrated where the volcanic flow comes down. This is where we are seeing these images. There are plenty of other surfaces where they could have gone but they chose these areas, and you can truly feel the power of the place.

It is a place that is so significant looking at the twins, and they’re armless, there were these things (inverse triangles), they were almost like areas to go in, so you go into the underworld or to another dimension, you can exit out of those as well. Anyways, those were right by the twins, and it was something that was facing right towards that volcanic knoll over there, which I referenced earlier. And like I said, it’s like a magnet for this area. It also accounts for why there are variations in some of these drawings. Some of these are extremely old and are beginning to be covered with desert varnish and lichen and things, but they are all the same kind of things but with variations.

8. Cultural Significance of Portals in Delamar Valley

Portals in Southern Paiute Territory

The Spring Mountain range is a powerful area that is centrally located in the lives, history, and minds of Nuwuvi people. The range is a storied land, which exists as both physical and mythic reality, both simultaneously connected by portals through, which humans and ocher life forms can and do pass back and forth. This is as it was at Creation.

9. The Nevada Regional Landscape

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Time immemorial is a legal term that is used to describe deep time occupation of lands by Indigenous peoples (Kelly 1975). |

References

- Anyon, Roger, T. J. Ferguson, Loretta Jackson, and Lillie Lane. 1996. Native American Oral Traditions and Archaeology. SAA Bulletin 14: 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, Keith. 1996. Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language Among the Western Apache. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Matthew R., David Bustos, Jeffrey S. Pigati, Kathleen B. Springer, Thomas M. Urban, Vance T. Holliday, Sally C. Reynolds, Marcin Budka, Jeffrey S. Honke, and Adam M. Hudson. 2021. Evidence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum. Science 373: 1528–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlet, David. 2007. Effects of Groundwater Transport from Cave, Delamar, and Dry Lake Valleys on Terrestrial Ecosystems of Lincoln and Adjacent Nye and White Pine Counties, Nevada. State of Nevada Division of Water Resources, Cave Valley, Dry Lake Valley, and Delamar Valley Water Rights Hearings. Available online: http://www.forestry.state.nv.us/hearings/past/dry/exhibits/ACE%5CInitial%20Evidentiary%20Exchange/Exhibit%201150.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2011).

- Deloria, Vine. 2003. God Is Red. Golden: Fulcrum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Earkin, Thomas E. 1963. Ground-Water Appraisal of Dry Lake and Delamar Valleys, Lincoln County, Nevada. Ground-Water Resources—Reconnaissance Series, 16. Carson: United States Department of the Interior, United States Geological Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Facilitators, Inc. 1980. MX/Native American Cultural and Socio-Economic Studies–Draft. Las Vegas: Facilitators Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Grayson, Donald. 1993. The Desert’s Past: A Natural Prehistory of the Great Basin. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greider, Thomas, and Lorraine Garkovich. 1994. Landscapes: The Social Construction of Nature and the Environment. Rural Sociology 59: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, Dan, Laura McAtackney, and Graham Fairclough. 2007. Envisioning Landscape: Situations and Standpoints in Archaeology and Heritage. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jayko, A. S. 2007. Geologic Map of the Pahranagat Range, 30’ x 60’ Quadrangle, Lincoln and Nye Counties, Nevada. United States Geological Survey, Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Daniel. 1975. Indian Title: The Rights of American Natives in Lands They have Occupied Since Time Immemorial. Columbia Law Review 75: 655–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, Carobeth. 1976. The Chemehuevis. Banning: Malki Museum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Jay. 1983. Basin religion and theology: A Comparative Study of Power. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 5: 66–86. [Google Scholar]

- Pigati, Jeffrey S., Kathleen B. Springer, Jeffrey S. Honke, David Wahl, Marie R. Champagne, Susan R. H. Zimmerman, Harrison J. Gray, Vincent L. Santucci, Daniel Odess, David Bustos, and et al. 2023. Independent age estimates resolve the controversy of ancient human footprints at White Sands. Science 382: 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reso, Anthony. 1959. The Geology of the Pahranagat Range, Lincoln County, Nevada. Ph.D. dissertation, Rice University, Houston, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ruuska, Alex. 2025. When the Earth Was New: Memory, Materiality, and Numic Ritual Life Cycle. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffle, Richard, and Henry Dobyns. 1983. Nuvagantu: Nevada Indians Comment on the Intermountain Power Project. Prepared for the Bureau of Land Management, Nevada, the Applied Urban Field School, University of Wisconsin, Parkside, Kenosha. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10150/270834 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Stoffle, Richard, Glenn Rogers, Ferman Grayman, Gloria Bulletts-Benson, Kathleen Van Vlack, and Jessica Medwied-Savage. 2008. Timescapes in conflict: Cumulative impacts on a solar calendar. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 26: 209–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffle, Richard, Kathleen Van Vlack, Hannah Johnson, Phillip Dukes, Stephanie De Sola, and Kristen Simmons. 2011. Tribally Approved American Indian Ethnographic Analysis of the Proposed Delamar Valley Solar Energy Zone. Tucson: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffle, Richard, Kathleen Van Vlack, Richard Arnold, David Whitley, Jannie Loubser, Alex Ruuska, and Alannah Bell. 2025. White River Geoscape: Native American Cultural Responses to its Geology and Hydrology. Land. Under review. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffle, Richard, Kathleen Van Vlack, Sean O’Meara, Richard Arnold, and Betty Cornelius. 2021. Incised Stones and Southern Paiute Cultural Continuity. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 41: 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffle, Richard, Rebecca S. Toupal, and M. Nieves Zedeño. 2002. East of Nellis: Cultural Landscapes of the Sheep and Pahranagat Mountain Ranges. Tucson: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffle, Richard W., Fletcher Chmara-Huff, Kathleen Van Vlack, and Rebecca Toupal. 2004. Puha Flows From It: The Cultural Landscape Study of the Spring Mountains. Tucson: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffle, Richard W., Richard Arnold, Kathleen Van Vlack, Larry Eddy, and Betty Cornelius. 2009. Nuvagantu, ‘Where Snow Sits’: Origin Mountain of the Southern Paiutes. In Landscapes of Origin. Edited by Jessica Christie. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tilley, Chris. 1994. A Phenomenology of Landscapes: Places, Paths, and Monuments. Oxford: Berg Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Tschnz, Charles McFarland, and Earl Haig Pampeyan. 1961. Preliminary Geologic Map of Lincoln County, Nevada. Washington, DC: United States Department of the Interior, United States Geological Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vlack, Kathleen. 2012. Southern Paiute Pilgrimage and Relationship Formation. Journal of Ethnology 51: 129–40. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vlack, Kathleen, Alex Ruuska, Richard Stoffle, Bianca Eguino Uribe, and Alannah Bell. 2024. Earth Birthing Geoscapes: Southern Paiute Ceremonies and Grand Canyon Volcanos. Geology, Earth, and Marine Sciences 6: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, Philip V. 1983. Paleobiogeography of Montane Islands in the Great Basin since the Last Glaciopluvial. Ecological Monographs 43: 341–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, David. 2024. Ontological Beliefs and Hunter–Gatherer Ritual Landscapes: Native Californian Examples. Religions 15: 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zedeño, María Nieves. 2000. On What People Make of Places: A Behavioral Cartography. In Social Theory in Archaeology. Edited by Michael B. Schiffer. Salt Lake: University of Utah Press, pp. 97–111. [Google Scholar]

| Feature Type | Special Feature |

|---|---|

| Source for Water | Seasonal Delamar playa lake, Pleistocene lakes and wetlands, Pahranagat Valley |

| Evidence of Previous Native American Use | Grinding slicks, rock shelter, offerings, water babies, Ocean Woman’s Net, mountain sheep peckings, Knotted Strings, Twins peckings |

| Geological Features | Volcanic mountains (Southern Pahroc Range), Delamar Mountains, isolated knoll (Turtle Butte), Seasonal Delamar playa lake, viewscape |

| Source for Plants | Ceremonial plants, medicinal plants, food plants, utilitarian plants |

| Source for Animals | Birds of prey, game birds, migratory birds, predatory mammals, game mammals, small mammals, lizards, snakes, spiritual animals |

| Native American History | Labor mine camp, Native American doctoring, Native American cowboys, family history |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Van Vlack, K.; Arnold, R.; Bell, A. Shamans, Portals, and Water Babies: Southern Paiute Mirrored Landscapes in Southern Nevada. Arts 2025, 14, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030056

Van Vlack K, Arnold R, Bell A. Shamans, Portals, and Water Babies: Southern Paiute Mirrored Landscapes in Southern Nevada. Arts. 2025; 14(3):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030056

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan Vlack, Kathleen, Richard Arnold, and Alannah Bell. 2025. "Shamans, Portals, and Water Babies: Southern Paiute Mirrored Landscapes in Southern Nevada" Arts 14, no. 3: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030056

APA StyleVan Vlack, K., Arnold, R., & Bell, A. (2025). Shamans, Portals, and Water Babies: Southern Paiute Mirrored Landscapes in Southern Nevada. Arts, 14(3), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030056