Hybrid Forms, Composite Creatures, and the Transit Between Worlds in Ancestral Puebloan Imagery

Abstract

1. Introduction

Despite all the vast differences in conceptualization in different cultures, religions, and philosophies, using animals as a second self seems to be virtually universal. Mythologies throughout the world tell of intimate kinships that people have established with animals, whether as shapeshifters in the present or as ancestors in the remote past.

1.1. The “Meaning of Meaning”

1.2. Ambiguity, Polysemy, Multivalence

The power of these images not only derives from their ability to project the past into the present, but also from their ambiguity. All of these figures can refer to a number of meanings at the same time, an attribute inherent in the underlying principle of directionality as well… their very undecipherability lends itself to multiple but related meanings, all encompassed in the designation ‘signs from the ancestors’.

1.3. Counterpoint, Reference, Metaphor

1.4. Resemblance, Similarity, Identification

1.5. Notes on the Use of Images

1.6. Notes on the Use of Language

2. Study Area

3. Puebloan Perceptions of Geography and Cosmography

Stoffle et al. (2015, p. 109) state that generally, Pueblos perceive lava tubes as connected to places of emergence from which people came into the present world. Puebloan perceptions of this world between worlds, or its interface as manifest in the present world, are eloquently summed up by Laurie Weahkee (Diné, Kotyiti, and Zuni, cultural advisor):The lava tube is a passage, where prayers and artifacts-of-prayer are closer to the great divide [between the natural and supernatural realms of the cosmos], and can be more efficiently channeled to the underlying waters; channeled to the most sacred of the four mountains which lies “somewhere beyond the great divide…where all the communications come in to permit, to initiate, to officiate anything that is asked by prayers.(testimony by William Weahkee, 6 March 1993 cited in Brunnemann 1995, p. 29)

Puebloan understanding of center, emergence, movement, connectedness, and breath are all linked to “rightful orientation” (Cajete 1999 cited in Anschuetz 2002, p. 3.27). In fact, Anschuetz (2002, pp. 3.3–3.15) lays out the same concepts in what he calls the building blocks of Puebloan landscape relationships (also see Cajete 19949 Ortiz 1969; Saile 1977; Swentzell 1990 among others). Places of emergence are equated with the Hopi/Western Pueblo concept of shipap or sipapu. That is the portal through which it is understood that humans emerged from a flooded underworld (Kelley and Francis 2002 in Anschuetz et al. 2002, p. 5.27).(t)he rugged, jagged escarpment is a physical manifestation of how Mother Earth labored in a painful birthing process… This volcanic escarpment is the centerpiece of a larger belief structure incorporating the highest peaks of surrounding mountain ranges, all of which can be seen from the escarpment… The spirit world, a world all around us and above is populated by different types of spirits, including spirits of deceased human beings on their journey to the next world. The volcanic escarpment and the area to the west perform a critical role in the functioning of this belief structure. As befitting an area of great volcanic activity, with crevices and channels leading down from the surface to places deep within the Earth, it is a location through which the creatures of the underworld gain entrance into this world.(quoted in Anschuetz 2002, pp. 3.31–3.32)

Geophysical Attributes and Connections

4. Mythic Context

4.1. Creation, Levels of the Worlds, and Emergence

4.2. Kachinas

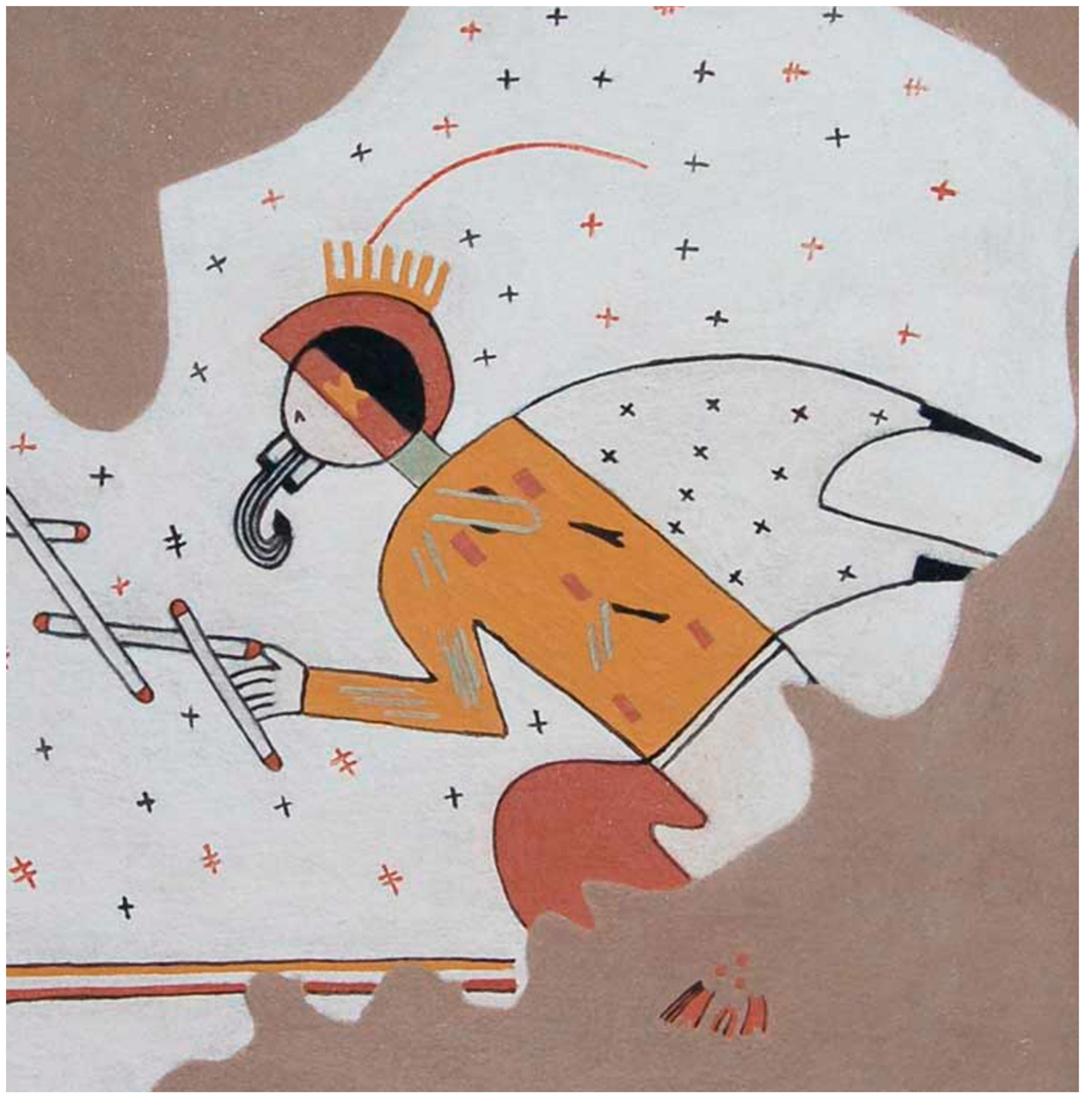

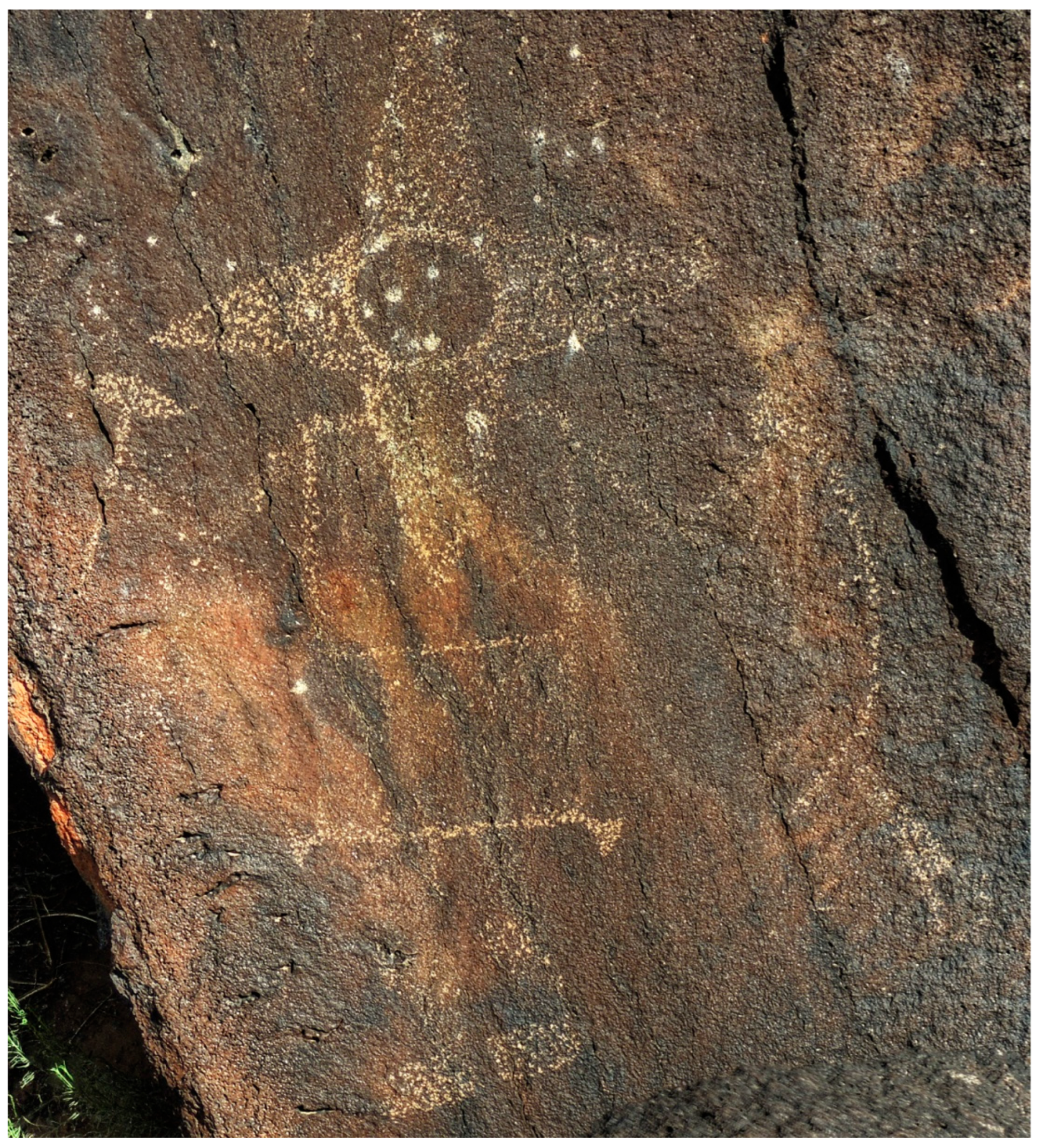

The mask may stand for the katsina spirit itself rather than a katsina impersonator. Articulated with the landscape, the mask image may be perceived as having the power to attract rain clouds, as many images are regarded as prayers for rain.

4.3. Transformation

Tyler refers to a phenomenon of interchangeable identity that occurs when actors in ceremonies become the very entities they are emulating by wearing costumes or masks. This interchangeability is itself ambiguous as to identity and represents transformation readily seen in rock imagery as well. Depictions of people wearing kachina costumes are as easily viewed as kachinas having a human form. The interplay between humans and their kachina counterparts represents a transformational act that was important in and of itself. All elements are equally blended so that no one quality prevails. This kind of visual ambiguity has also been called “trance-formation” by Le Quellec, when referring to shamanic transitions (Le Quellec 2004, p. 181) in his African studies.Almost synonymous with the rain clouds are the kachinas, who are spirits that come and go. They represent the dead in a general way, living in the mountains but passing over the villages occasionally to bring rain. The real kachinas are imitated by masked dancers in ceremonies who, while they wear masks are the real kachina spirits. Kachinas thus relate the spirit world to the world of man….

5. Creatures at the Time of Creation

5.1. Animals and Humans

The ‘moss people’ were infused with a particular kind of potency that they lost when humans became ‘finished beings’. Since that time, humans, the most finished of all creatures, have also been the least effective… Having little influence themselves, humans have had to rely on more powerful, raw beings to act as mediators…, especially the kachinas, and to convey… their prayers for rain. Such mediation is often effected by means of visual representations of the mediators in a variety of forms including masks, fetishes…, images on pottery, and perhaps, rock art as well.

5.2. Not Fully-Formed Humans

5.3. Deformed Humans

6. Beast Gods

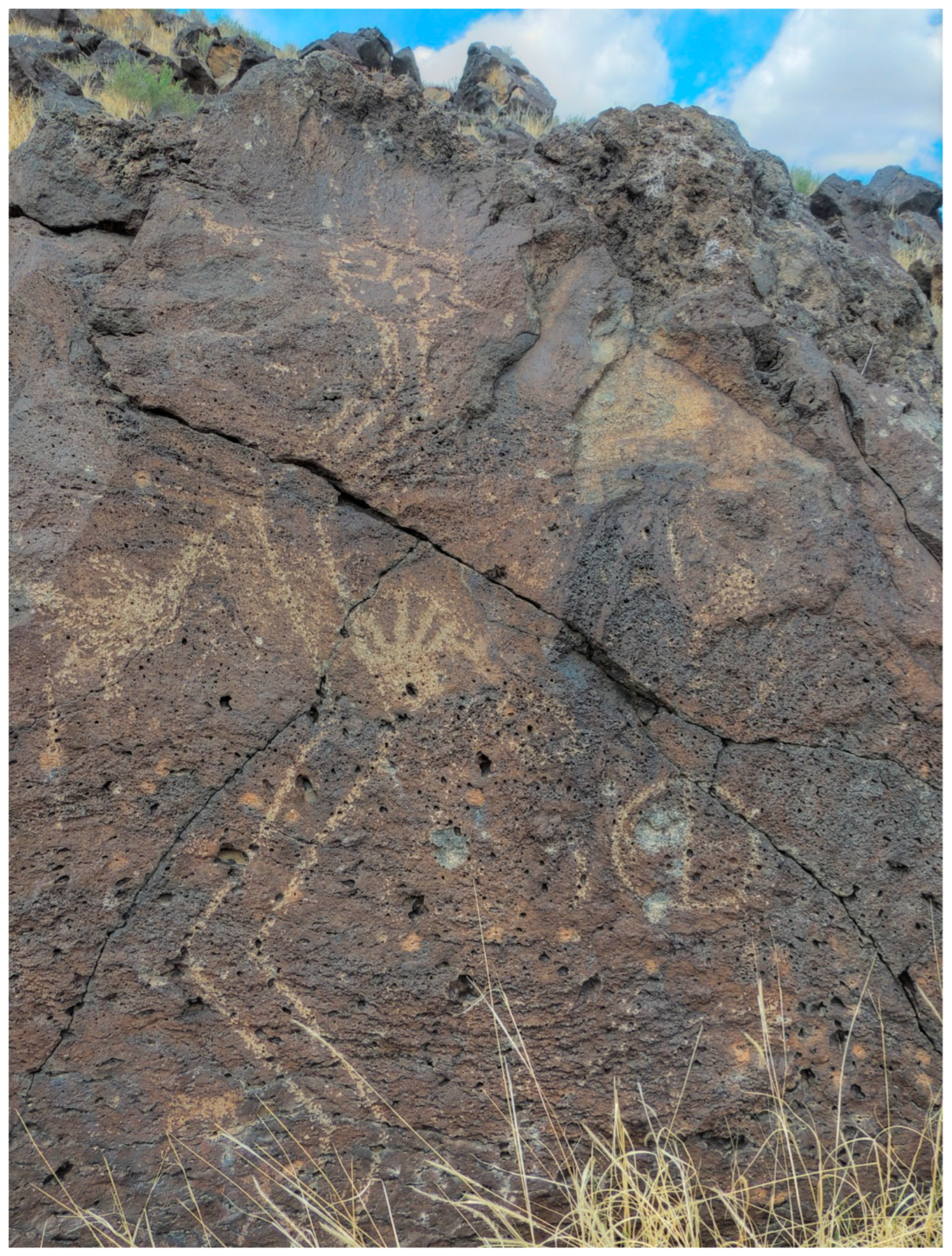

Another… group of powerful (raw) mediating beings often called upon to carry the spirit of Zuni prayers to the kachinas are the Beast Gods of the six directions… Images of the Beast Gods are painted on the walls and altars of the kivas and medicine society rooms… The six Beast Gods, however, rarely appear together in rock art. Only those identified as the mountain lion…, Knife-Wing or eagle…, and bear track… commonly occur, and even these three seldom appear together on the same rock face.

6.1. Mountain Lion

6.2. Eagle/Knife Wing Bird

6.3. Bear

7. Animal Hybrids

7.1. Birds

7.2. Parrots

7.3. Owls

7.4. Hummingbirds

7.5. Fish

7.6. Bats

8. Hybrid Beings

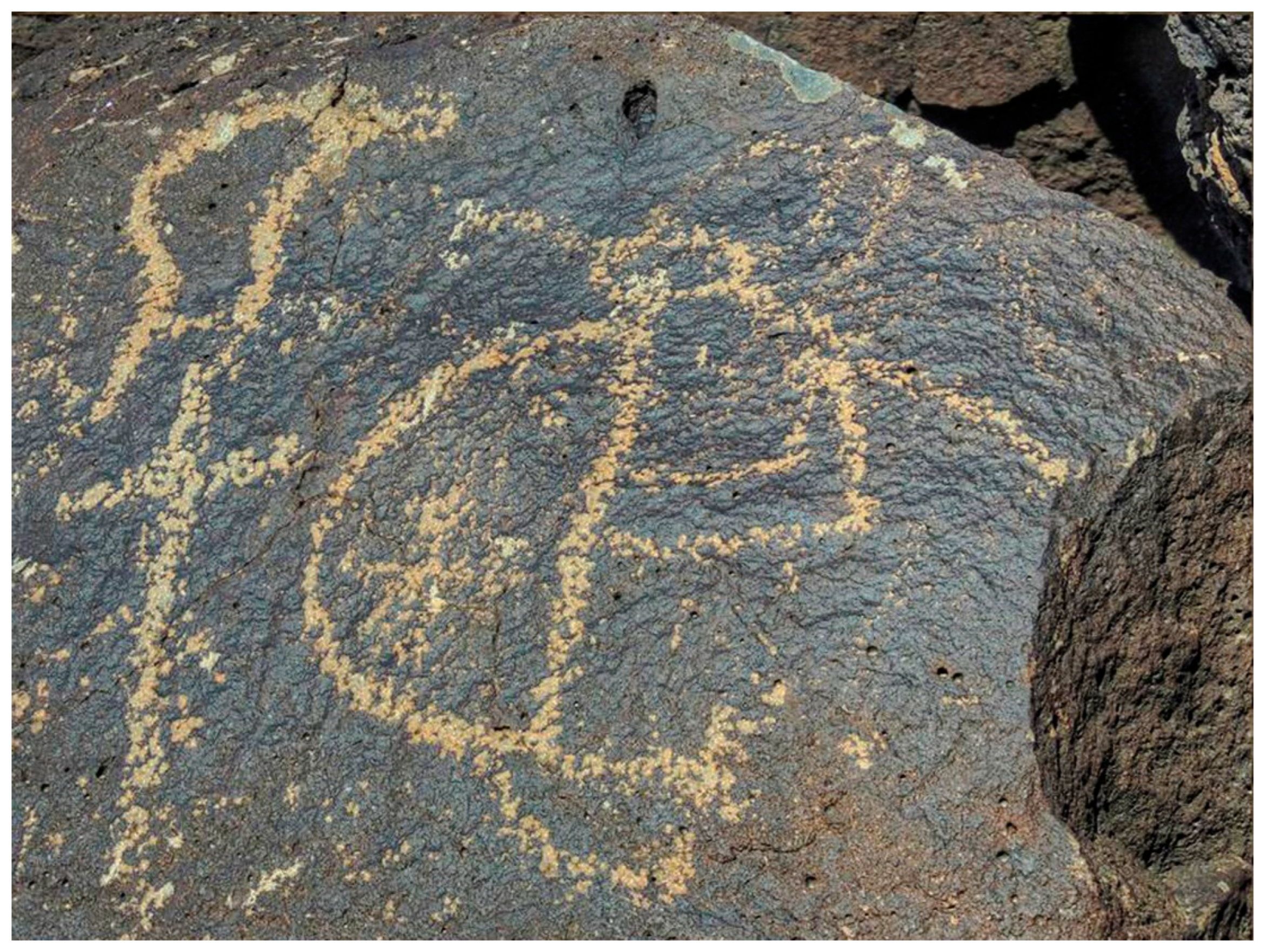

8.1. Animal–Animal Forms

8.2. Animal–Plant Forms

8.3. Human–Animal Forms

8.4. Human–Insect Forms

9. Celestial Images

9.1. Lightning

9.2. Stars

10. Complex Combinations

10.1. Mountain Lion, Star, and Serpent

10.2. Human Hybrid, Footprint, and Fish

11. Healing and Curing

11.1. Shamanism

11.2. Medicine and Plants

12. Death

12.1. Dissociated Body Parts

12.1.1. Human Appendages

12.1.2. Birds’ Legs

12.1.3. Earth God/War God

12.1.4. Shape-Shifting

13. Further Comparisons to Kiva Murals

With petroglyph panels, the focus is more on the individual elements and combinations of them as rendered on whole rock surfaces. What is nearby, directionality, and outdoor elements, such as the landscape, are as crucial as the images themselves.Kiva wall paintings, by virtue of the fact they embrace a flat wall, display a number of formal spatial and compositional strategies not employed in rock art. The decorative field may be covered by overall patterning… filled by well-composed paintings, often narrative in content, portraying ongoing ritual performances.

… rock art commands irregular spaces on often rough surface and boulders (favoring) isolated, scattered icons or small figure groups at best… To economize the efforts needed to produce images pecked in stone, abstraction and simplification were the rule, and usually only sacred elements that would convey essential meanings were pictured.

14. Conclusions

Zunis relate the imagery of other material forms to the time of ‘the ancestors’ as well. In fact, they surround themselves with symbols that represent important beings and events of the myth time; these symbols serve conceptually to link the two states of experience, the here-and-now and the myth… While this may be a means by which Zunis validate their beliefs and ritual practices, it also reveals much about the Zuni attitude toward time. Zunis are constantly aware of the presence of the past; this awareness is facilitated by symbols, prevalent in every aspect of Zuni life, that evoke their past”.

- A.

- Employing supernatural actors/agents to participate in and convey actions or powers within the context of mythic narrative. The most effective device in this regard is the hybrid being, which bears characteristics of multiple creatures, concepts, or gods.

- B.

- Employing aspects of the physical environment to reinforce the setting of or to animate events described in mythic narratives. Examples are connections to other worlds: emergence onto rock surfaces through cracks; using boulders’ shapes, or natural features in rocks such as air bubbles, ledges, shelves, or overhangs.

- C.

- Associations of specific sets of interrelated elements, whether as individually distinct forms or (re)combined to make new forms. Some examples apparently prevalent over wide geographic areas are star, feline, and serpent. Other examples are water-related symbolism, such as spirals and reptiles, or death-related symbols.

- D.

- Concepts of geographic cosmology: places of past formation and emergence (below), layered worlds, actions in the present physical world, supplications applying to future worlds (above), and passages between layers of worlds as part of major life events such as birth and death.

- E.

- Concepts of time and space which run parallel, such as below–here–above and past–present–future.

- F.

- Concepts of emergence, formation, and transformation.

- G.

- Concepts of ambivalence, ambiguity, multiplicity, multivalence, and polysemy.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anschuetz, Kurt F. 2002. A Healing Place: Río Grande Pueblo Cultural Landscapes and the Petroglyph National Monument. In “That Place People Talk About”: The Petroglyph National Monument Ethnographic Landscape Report. Edited by Kurt F. Anschuetz, T. J. Ferguson, Harris Francis, Klara B. Kelley and Cherie L. Schieck. Community and Cultural Landscape Contribution VIII. Washington, DC: Petroglyph National Monument, National Park Service, Department of the Interior. [Google Scholar]

- Anschuetz, Kurt F., T. J. Ferguson, Harris Francis, Klara B. Kelley, and Cherie L. Schieck. 2002. “That Place People Talk About”: The Petroglyph National Monument Ethnographic Landscape Report. Community and Cultural Landscape Contribution VIII. Washington, DC: Petroglyph National Monument, National Park Service, Department of the Interior. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardini, Wesley, Stewart B. Koyiyumptewa, Gregson Schachner, and Leigh J. Kuwanwisiwma, eds. 2021. Becoming Hopi: A History. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brody, Jerry J. 1998. It Begins and Ends with the Landscape. In Voices from a Sacred Place: In Defense of Petroglyph National Monument. Friends of the Albuquerque Petroglyphs and Sacred Sites International. Edited by Huser Verne. Seattle: Artcraft Printing, pp. 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- Brunnemann, Eric J. 1995. Archeological Reconnaissance of a Lava Tube Shrine Located Within the Boundary of Petroglyph National Monument. Park Papers PETR-03. Washington, DC: Petroglyph National Monument, National Park Service, Department of the Interior. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete, Gregory A., ed. 1999. “Look to the Mountain”: Reflections on Indigenous Ecology. In A People’s Ecology: Explorations in Sustainable Living. Santa Fé: Clear Light Publishers, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, Robin M. 2013. Final Report on Excavations of the Alameda School Site (LA 421): A Classic Period Pueblo of the Tiguex Province. Office of Contract Archeology Report No. 185-969. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Courlander, Harold. 1987. The Fourth World of the Hopis. The Epic Story of the Hopi Indians as Preserved in Their Legends and Traditions. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crotty, Helen K. 2007. Western Pueblo Influences and Integration in the Pottery Mound Painted Kivas. In New Perspectives on Pottery Mound Pueblo. Edited by Polly Schaafsma. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, pp. 85–108. [Google Scholar]

- Culley, Elisabeth V. 2006. The Meaning of Metaphor: A Cognitive Approach to Prehistoric Ideation. Master’s thesis, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cushing, Frank H. 1920. Zuni Breadstuff. Indian Notes and Monographs. New York: Museum of the American Indian, vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Cushing, Frank H. 1967. Zuni Fetishes. Las Vegas: KC Publications. First published 1883. [Google Scholar]

- Cushing, Frank H. 1988. The Mythic World of the Zuni. Edited by Barton Wright. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, Bertha P. 1963. Sunfather’s Way: The Kiva Murals of Kuaua, a Pueblo Ruin, Coronado State Monument, New Mexico. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Michael J., Richard W. Stoffle, and Sandra Lee Pinel. 1993. Petroglyph National Monument Rapid Ethnographic Assessment Project. Tucson: Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, T. J. 2002. Western Pueblos and the Petroglyph National Monument: An Assessment of the Cultural Landscapes of Ácoma, Laguna, Zuni, and Hopi. In “That Place People Talk About”: The Petroglyph National Monument Ethnographic Landscape Report. Edited by Kurt F. Anschuetz, T. J. Ferguson, Harris Francis, Klara B. Kelley and Cherie L. Schieck. Community and Cultural Landscape Contribution VIII. Washington, DC: Petroglyph National Monument, National Park Service, Department of the Interior. [Google Scholar]

- Heib, Louis A. 1994. The meaning of katsina: Toward a cultural definition of “person” in Hopi religion. In Kachinas in the Pueblo World. Edited by Polly Schaafsma. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, pp. 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hibben, Frank C. 1975. Kiva Art of the Anasazi at Pottery Mound. Las Vegas: KC Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Huckell, Lisa W., and Christine S. VanPool. 2006. Toloatzin and shamanic journeys exploring the ritual role of sacred datura. In Religion of the Prehispanic Southwest. Edited by Christine S. VanPool, Todd L. VanPool and David A. Phillips. Walnut Creek: Altamira Press, pp. 147–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, Klara, and Harris Francis. 2002. Chézhin Sinil (Rock-That-Defends): Navajo Cultural Landscapes and the Petroglyph National Monument. In “That Place People Talk About”: The Petroglyph National Monument Ethnographic Landscape Report. Edited by Kurt F. Anschuetz, T. J. Ferguson, Harris Francis, Klara B. Kelley and Cherie L. Schieck. Community and Cultural Landscape Contribution VIII. Washington, DC: Petroglyph National Monument, National Park Service, Department of the Interior. [Google Scholar]

- Le Quellec, Jean-Loïc. 2004. Rock Art in Africa: Mythology and Legend. Translated by Paul Bahn. Paris: Flammarion Press. [Google Scholar]

- National Park Service. 2025. Park Archives: Petroglyph National Monument. Available online: https://npshistory.com/publications/petr/index.htm (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Ortiz, Alfonso. 1969. The Tewa World: Space, Time, Being, and Becoming in a Pueblo Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Elsie Clews. 1939. Pueblo Indian Religion. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, John Wesley. 1904. Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. Washington, DC: United States Bureau of Ethnology. [Google Scholar]

- Saile, David G. 1977. Making a House: Building Rituals and Spatial Concepts in the Pueblo Indian World. Architectural Association Quarterly 9: 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sax, Boria. 2013. Imaginary Animals: The Monstrous, the Wondrous and the Human. London: Reaktion Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma, Polly. 1980. Indian Rock Art of the Southwest. Santa Fé: School of American Research and Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. First published 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma, Polly, ed. 1994a. Kachinas in the Pueblo World. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma, Polly, ed. 1994b. The Prehistoric Kachina Cult and Its Origins as Suggested by Southwestern Rock Art. In Kachinas in the Pueblo World. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma, Polly. 2000. Warrior, Shield, and Star: Imagery and Iconography of Pueblo Warfare. Santa Fe: Western Edge Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma, Polly, ed. 2007a. New Perspectives on Pottery Mound Pueblo. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma, Polly, ed. 2007b. The Pottery Mound Murals in Rock Art. In New Perspectives on Pottery Mound Pueblo. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, pp. 137–66. [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma, Polly. 2023. Blurred Boundaries: Perspectives on Rock Art of the Greater Southwest. Photographs by William Frej. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmader, Matthew F. 1996. Identification and Analysis of Bird Iconography at Petroglyph National Monument. Paper presented at the 61st Annual Conference of the Society for American Archaeology, New Orleans, LA, USA, April 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Schmader, Matthew F., and John D. Hays. 1986. Las Imagines: The Archaeology of Albuquerque’s West Mesa. Report prepared for City of Albuquerque and New Mexico Historic Preservation Division. Santa Fe: New Mexico Historic Preservation Division. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, Matilda Coxe. 1904. The Zuni Indians. Their Mythology, Esoteric Fraternities, and Ceremonies. Twenty-third Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1901–1902. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffle, Richard W., Richard Arnold, Maurice Frank, Betty Cornelius, Lalovi Miller, Jerry Charles, Gerald Kane, Alex K. Ruuska, and Kathleen Van Vlack. 2015. Ethnology of Volcanoes: Quali-Signs and the Cultural Centrality of Self-Voiced Places. In Engineering Mountain Landscapes: An Anthropology of Social Investment. Edited by Laura L. Scheiber and Maria Nieves Zedeno. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Swentzell, Rina. 1990. Pueblo Space, Form, and Mythology. In Pueblo Style and Regional Architecture. Edited by Nicholas C. Markovich, Wolfgang F. E. Preiser and Fred Sturm. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, pp. 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Marc. 2006. Pre-Columbian Venus: Celestial Twin and Icon of Duality. In Religion in the Prehispanic Southwest. Edited by Christine S. Van Pool, Todd L. Van Pool and David A. Phillips, Jr. Walnut Creek: Altamira Press, pp. 165–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, Hamilton A. 1979. Pueblo Birds and Myths. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Underhill, Ruth M. 1948. Ceremonial Patterns in the Greater Southwest. In Monographs of the American Ethnological Society. Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Weahkee, Laurie. 1997. Statement in Opposition to S. B. 633, Submitted by the Petroglyph Monument Protection Coalition. Albuquerque: SAGE Council, unpublished MS. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2000. The Art of the Shaman: Rock Art of California. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2011. Introduction to Rock Art Research, 2nd ed. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Barton M. 1973. Kachinas: A Hopis Artists’ Documentary. Phoenix: The Heard Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Barton M. 1988. Hopi Kachinas: The Complete Guide to Collecting Kachina Dolls. Flagstaff: Northland Publishin. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M. Jane. 1988. Signs from the Ancestors: Zuni Cultural Symbolism and Perceptions of Rock Art. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schmader, M.F. Hybrid Forms, Composite Creatures, and the Transit Between Worlds in Ancestral Puebloan Imagery. Arts 2025, 14, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030054

Schmader MF. Hybrid Forms, Composite Creatures, and the Transit Between Worlds in Ancestral Puebloan Imagery. Arts. 2025; 14(3):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030054

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchmader, Matthew F. 2025. "Hybrid Forms, Composite Creatures, and the Transit Between Worlds in Ancestral Puebloan Imagery" Arts 14, no. 3: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030054

APA StyleSchmader, M. F. (2025). Hybrid Forms, Composite Creatures, and the Transit Between Worlds in Ancestral Puebloan Imagery. Arts, 14(3), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030054