Indigenous Archaeology, Collaborative Practice, and Rock Imagery: An Example from the North American Southwest

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Indigenous Archaeology as Social Critique

Indigenous Archaeology and Tribal Collaboration

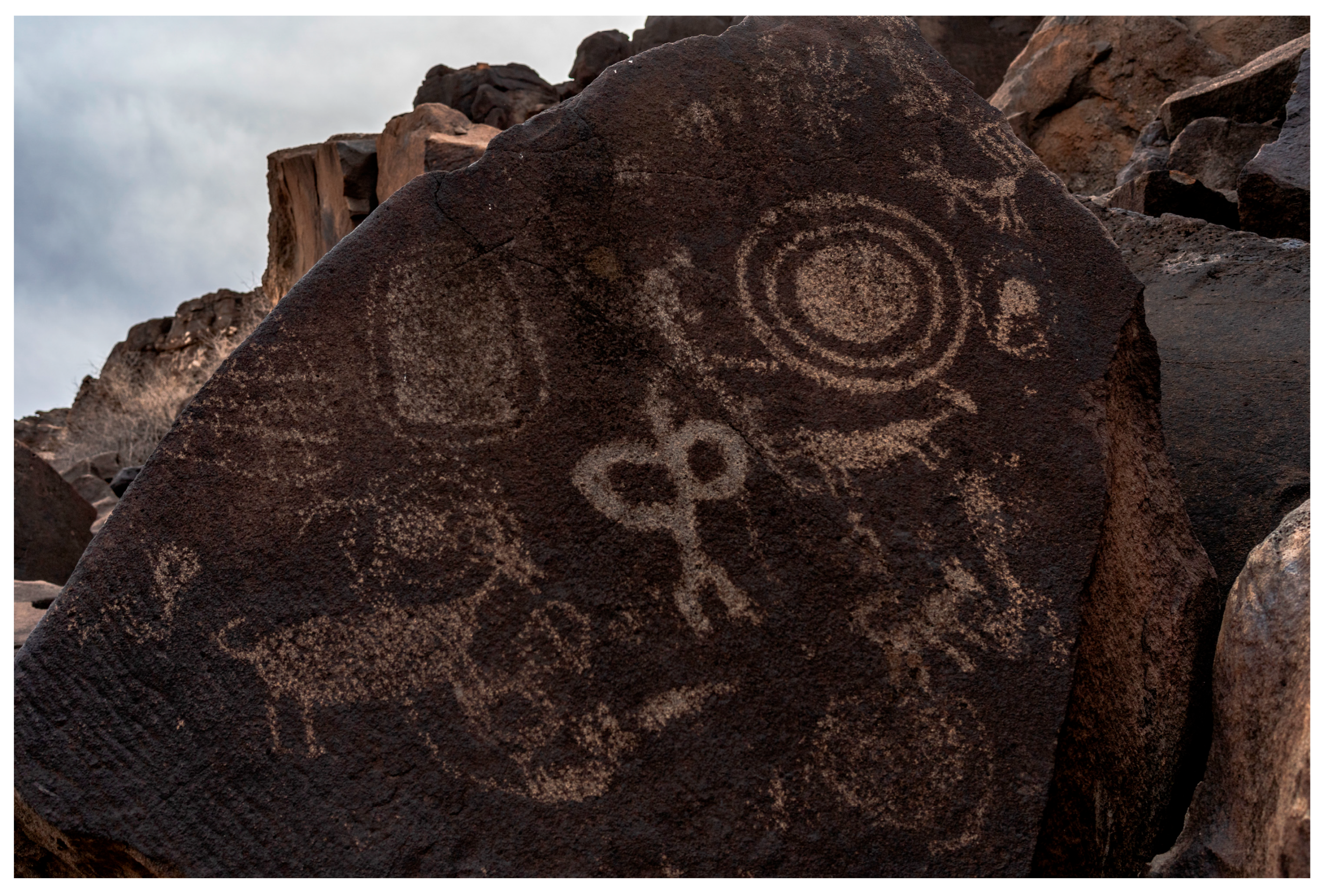

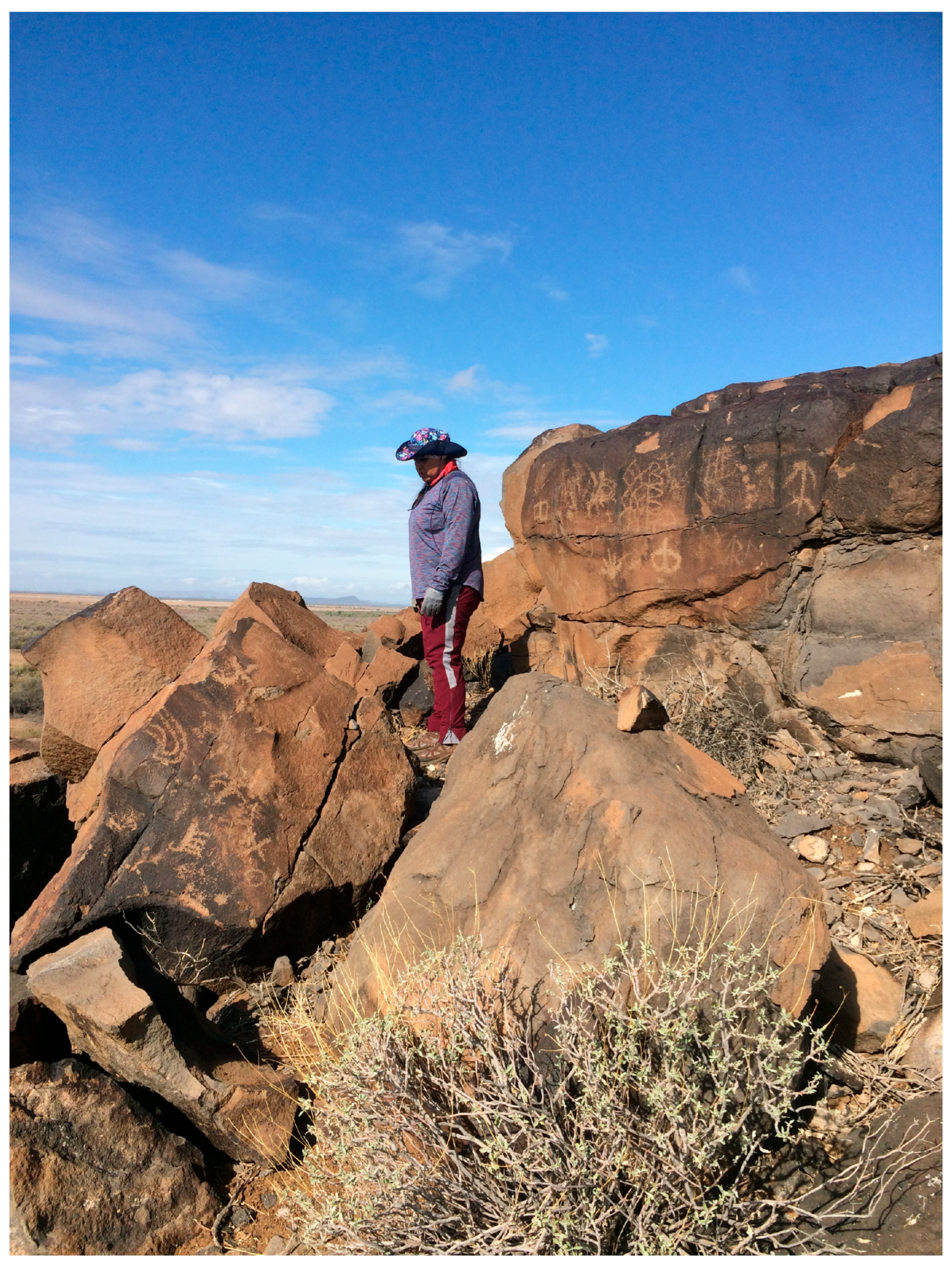

3. Indigenous Archaeology of Rock Imagery

The testimony of modern Indians concerning petroglyphs is extraordinarily disappointing. They know of them as landmarks, and sometimes believe them to have had a supernatural origin. But even where there is good evidence that the glyphs were made by the [T]ribes now inhabiting the area, the practice seems generally to have been abandoned at the advent of the white man and most knowledge of them promptly lost.(Steward 1936, p. 412, emphasis added)

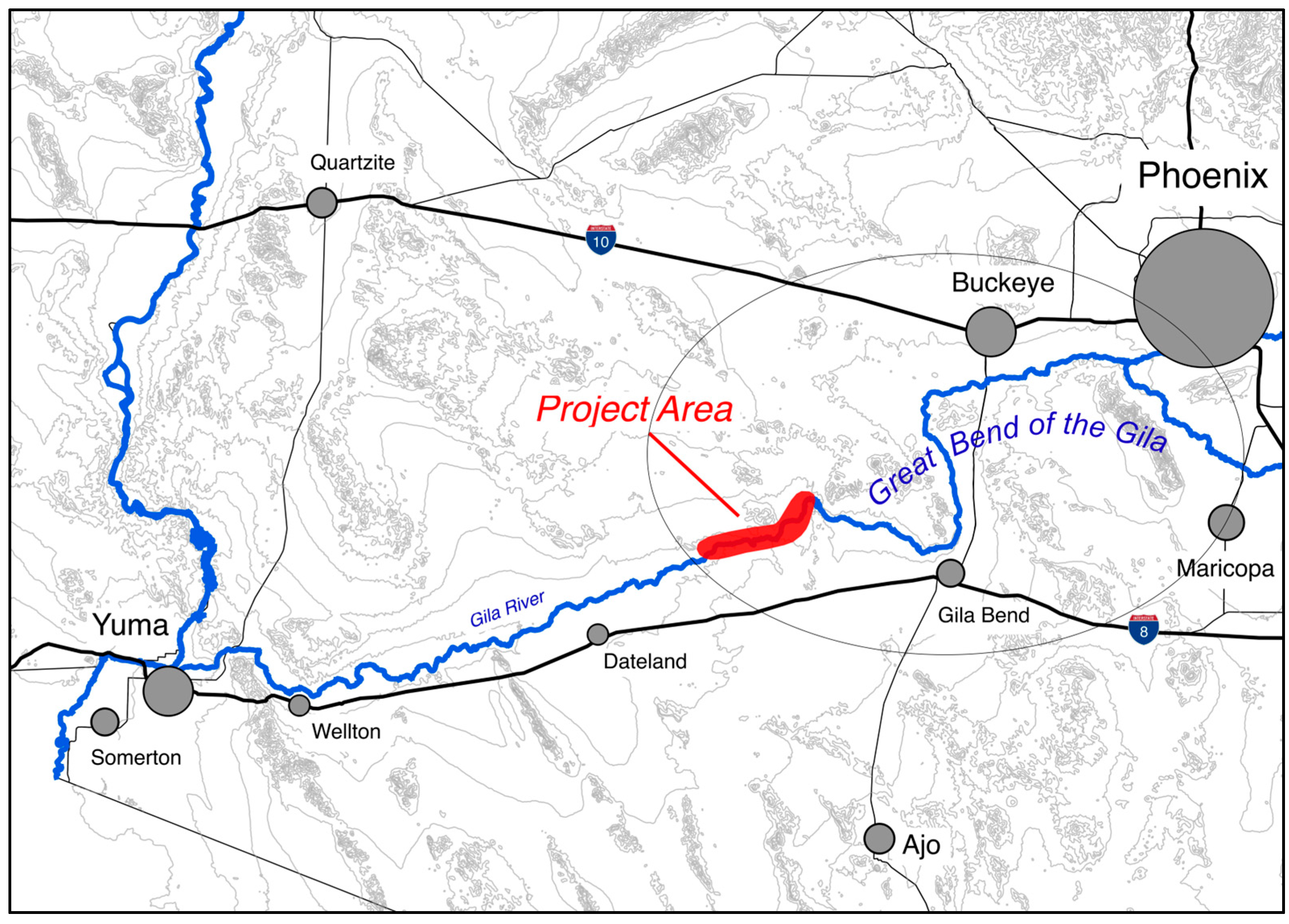

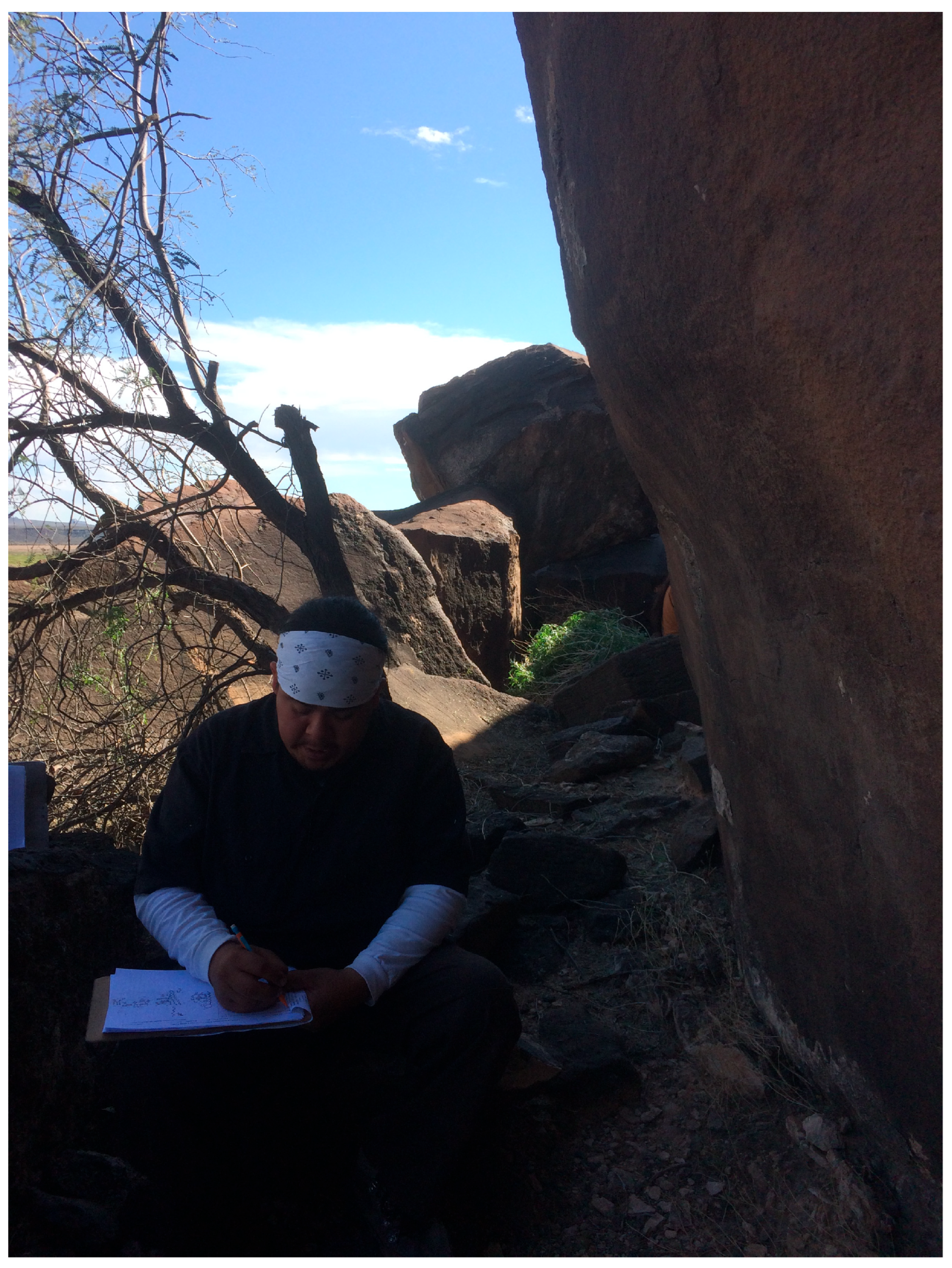

4. The Lower Gila River Ethnographic and Archaeological Project

The current ethnographic and archaeological sources note shifts between the Hohokam and Patayan traditions, suggesting a diverse and mixed cultural landscape. There is definitely more ethnographic and archaeological study to be done here. The SRPMIC is a Native community that derives their ancestry from both traditions. We believe any knowledge gathered from this endeavor can only benefit our already strong histories.[SRPMIC Cultural Resources Director Kelly Washington, 2016]

This letter is to notify you of our support for the [LGREAP}. The Yavapai have a long history of our ancestral activities in the proposed area of research, especially in the use of rock writings (ewee-tinuddiv) and earth figures known as geoglyphs. Our elders have described these marking as “our libraries,” which record Pai (Patayan) creation stories (Ickyuka), early calendar reckoning by stars, and trail markings that proliferate in this area. We look forward to working with you to provide more information on the cultural identity of the Yuman language peoples, which include the Yavapai, as recorded in the marks on earth and stone and in the oral histories of our people.[YPIT Culture Research Director Linda Ogo, 2016]

The lower Gila figures prominently in the Quechan creation account, and we maintain deep cultural and spiritual connections to this landscape. For us, these places manifest a spiritual power, and this essence binds our people to the land. The spiritual power unites all of [our] ancestral sites, as well as the landforms, animals, water, and people, into [a] holistic sacred landscape. We see [the project] as a way for our community to reconnect with ancestral Quechan places from which we have been displaced. These places are all that is left of our ancestors, and they are how we connect with our past and ensure that we continue into the future.[FYQIT President Mike Jackson, 2016]

5. Discussion

5.1. Relationships

5.2. Responsibility

5.3. Reciprocity

5.4. Redistribution

5.5. Respect

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LGREAP | Lower Gila River Ethnographic and Archeological Project |

| SARIA | Southern Arizona Rock Imagery Archive |

| SRPMIC | Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community |

| GRIC | Gila River Indian Community |

| YPIT | Yavapai-Prescott Indian Tribe |

| FYQIT | Fort Yuma Quechan Indian Tribe |

| NEH | National Endowment for the Humanities |

| CRS | Congressional Research Service |

| NCES | National Center for Education Statistics |

| US | United States |

| 1 | “Rock imagery,” as employed in this article, is in reference to iconographic markings on parietal rock surfaces. Such phenomena are often described as rock art, or more specifically petroglyphs, pictographs, rock paintings, etc. I substitute “rock imagery” out of respect for the Tribes with whom I work, and in recognition of the ontological and ethical problems with describing and equating their ancestral marks, many of which have sacred associations, as “art” (Wright and Welch 2025). |

References

- Allen, Harry, and Caroline Phillips, eds. 2010. Bridging the Divide: Indigenous Communities and Archaeology into the 21st Century. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Altamirano Rayo, Giorleny, Eric S. Mosinger, and Kai M. Thaler. 2024. Statebuilding and Indigenous Rights Implementation: Political Incentives, Social Movement Pressure, and Autonomy Policy in Central America. World Development 175: 106468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amberson, Sophia E. 2017. Traditional Ecological Disclosure: How the Freedom of Information Act Frustrates Tribal Natural Resource Consultation with Federal Agencies. Washington Law Review 92: 937–81. [Google Scholar]

- Angelbeck, Bill, and Colin Grier. 2014. From Paradigms to Practices: Pursuing Horizontal and Long-Term Relationships with Indigenous Peoples for Archaeological Heritage Management. Canadian Journal of Archaeology 38: 519–40. [Google Scholar]

- Archibald, Jo-Ann, Jenny Lee-Morgan, and Jason De Santolo, eds. 2019. Decolonizing Research: Indigenous Storywork as Methodology. London: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Atalay, Sonya. 2006. Indigenous Archaeology as Decolonizing Practice. American Indian Quarterly 30: 280–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, Sonya. 2008. Multivocality and Indigenous Archaeologies. In Evaluating Multiple Narratives: Beyond Nationalist, Colonialist, Imperialist Archaeologies. Edited by Junko Habu, Clare Fawcett and John M. Matsunaga. New York: Springer, pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Atalay, Sonya. 2012. Community-Based Archaeology: Research with, by, and for Indigenous and Local Communities. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Atalay, Sonya, Lee Rains Clauss, Randall H. McGuire, and John R. Welch, eds. 2014. Transforming Archaeology: Activist Practices and Prospects. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bakieva, Gulnara A. 2007. Social Memory and Contemporaneity. Kyrgyz Philosophical Studies I. Washington: The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy. [Google Scholar]

- Bevan, Alana K. 2021. The Fundamental Inadequacy of Tribe-Agency Consultation on Major Federal Infrastructure Projects. University of Pennsylvania Journal of Law & Public Affairs 6: 561–601. [Google Scholar]

- Billo, Evelyn, Robert Mark, and Donald E. Weaver, Jr. 2013. Sears Point Rock Art Recording Project, Arizona, USA. In American Indian Rock Art. 40 vols. Edited by Mavis Greer and Peggy Whitehead. Tucson: American Rock Art Research Association, pp. 1283–302. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, Michelle. 2023. Humility. Listen. Respect: Three Values Underpinning Indigenous (Environmental) Education Sovereignty. Progress in Environmental Geography 2: 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Geoffrey, and Ghilraen Laue. 2024. Rock Art and Hunter–Gatherer Landscapes: Iconography, Cosmology and Topography in Southern Africa. Arts 14: 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, Geoffrey, Christopher Chippindale, and Bejamin Smith, eds. 2012. Seeing and Knowing: Understanding Rock Art with and Without Ethnography. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, Carolyn E. 2016. The White Shaman Mural: An Enduring Creation Narrative in the Rock Art of the Lower Pecos. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruchac, Margaret, Siobhan Hart, and H. Martin Wobst, eds. 2010. Indigenous Archaeologies: A Reader on Decolonization. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bruder, J. Simon. 1983. Archaeological Investigations at the Hedgpeth Hills Petroglyph Site. Research Paper No. 28. Flagstaff: Museum of Northern Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- Cabak Rédei, Anna, Peter Skoglund, and Tomas Persson. 2020. Seeing Different Motifs in One Picture: Identifying Ambiguous Figures in South Scandinavian Age Rock Art. Cogent Arts & Humanities 7: 1802804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachora, Lorey. 1994. The Spirit Life of Yuman-Speaking Indians: Lower Colorado River between California and Arizona. In Recent Research along the Lower Colorado River. Edited by Joseph A. Ezzo. Technical Series No. 51; Tucson: Statistical Research, pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cachora, Lorey. 2000. Antelope Hill and the Region: A Native American View. In Of Stone and Spirits: Pursuing the Past of Antelope Hill. Edited by Joan S. Schneider and Jeffrey H. Altschul. Technical Series No. 76; Tucson: Statistical Research, Inc., pp. 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cachora, Lorey, and Aaron M. Wright. 2017. The Antiquities Act was Meant to Protect Indian History. Paper presented at the The Salt Lake Tribune, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, August 18. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, Liz. 2024. ‘Reclaiming Their Stories’: A Study of the Spiritual Content of Historical Cultural Objects Through an Indigenous Creative Inquiry. Australian Archaeology 90: 140–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chino, Conroy. 2012. Petroglyphs of the Southwest: A Puebloan Perspective. Oro Valley: Western National Parks Association. [Google Scholar]

- Claassen, Cheryl, ed. 1994. Women in Archaeology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell, Chip. 2016. Collaborative Archaeologies and Descendant Communities. Annual Review of Anthropology 45: 113–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Chip, T. J. Ferguson, Dorothy Lippert, Randall H. McGuire, George P. Nicholas, Joe E. Watkins, and Larry J. Zimmerman. 2010. The Premise and Promise of Indigenous Archaeology. American Antiquity 34: 228–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Chip. 2003. Native American Perspectives of the Past in the San Pedro Valley of Southeastern Arizona. Kiva 69: 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congressional Research Service. 2024. Federal-Tribal Consultation: Background and Issues for Congress. Report R48093. Available online: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R48093 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Delgado, Anthony. 2021. From the Gila River to Bears Ears, an Effort Is Renewed to Protect Public Lands in the Southwest. Arizona Republic, April 22. [Google Scholar]

- Effros, Bonnie, and Guolong Lai, eds. 2018. Unmasking Ideology in Imperial and Colonial Archaeology: Vocabulary, Symbols, and Legacy. Ideas, Debates, and Perspectives 8. Los Angeles: Costen Institute of Archaeology Press, University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Ferg, Alan. 1979. The Petroglyphs of Tumamoc Hill. Kiva 45: 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricke, Felicia, and Rachel Hoerman. 2022. Archaeology and Social Justice in Island Worlds. World Archaeology 54: 484–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmansky, Dyana Z. 2022. Culturescape of the Great Bend of the Gila. Desert Leaf 35: 38–41, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, Sara L. 2017. Indigenous Values and Methods in Archaeological Practice: Low-Impact Archaeology Through the Kashaya Pomo Interpretive Trail Project. American Antiquity 81: 533–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, Sara L., and Briece Edwards. 2020. The Intersection of Indigenous Thought and Archaeological Practice: The Field Methdos in Indigneous Archaeology Field School. Journal of Community Archaeology and Field School 7: 239–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, Jacob W. 1970. Ethnographic Salvage and the Shaping of Anthropology. American Anthropologist 72: 1289–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Neha, Nancy Bonneau, and Michael Elvidge. 2022. Connecting Past to Present: Enacting Indigenous Data Governance Principles in Westbank First Nation’s Archaeology and Digital Heritage. Archaeologies 18: 623–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Neha, Sue Blair, and Ramona Nicholas. 2020. What We See, What We Don’t See: Data Governance, Archaeological Spatial Databases and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in an Age of Big Data. Journal of Field Archaeology 45 Suppl. 1: S39–S50. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson, Jamie, José Iriarte, and Francisco Javier Aceituno. 2024. ‘A World of Knowledge’: Rock Art, Ritual, and Indigenous Belief at SerranÍa de la Lindosa in the Colombian Amazon. Arts 13: 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, LaDonna, and Jacqueline Wasilewski. 2004. Indigeneity, an Alternative Worldview: Four R’s (Relationship, Responsibility, Reciprocity, Redistribution) vs. Two P’s (Power and Profit). Sharing the Journey Towards Conscious Evolution. Systems Research and Behavioral Science 21: 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath-Stout, Laura E., and Elizabeth M. Hannigan. 2020. Affording Archaeology: How Field School Costs Promote Exclusivity. Advances in Archaeological Practice 8: 123–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, Ken. 2000. Petroglyphs of the Lower Gila River, Southwestern Arizona. Glyphs 50: 8–9, 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges, Ken, and Diane Hamann. 1994. Oatman Point: New Discoveries on the Lower Gila. In American Indian Rock Art. 20 vols. Edited by Frank G. Bock. San Miguel: American Rock Art Research Association, pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges, Ken, and Diane Hamann. 1995. Petroglyphs at Quail Point, Southwestern Arizona. In Rock Art Papers. 12 vols. Edited by Ken Hedges. San Diego: Museum of Man, pp. 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Heizer, Robert F., and Martin A. Baumhoff. 1962. Prehistoric Rock Art of Nevada and Eastern California. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hingley, Richard. 2014. Colonial and Post-Colonial Archaeologies. In The Oxford Handbook of Archaeological Theory, Online ed. Edited by Andrew Gardner, Mark Lake and Ulrike Sommer. Oxford: Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Mark, Jesse Morin, Lia Tarle, Candace Newman, Raini Bevilacqua, Sheriden Barnett, Sean Markey, and Dana Lepofsky. 2024. Indigenous Cultural Heritage Policies as a Pathway for Indigenous Sovereignty and the Role of Local Governments: An Example with K’ómoks First Nation, British Columbia. Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology 3: 1427458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyser, James D., George Poetschat, and Michael W. Taylor, eds. 2006. Talking with the Past: The Ethnography of Rock Art. Publication No. 16. Portland: Oregon Archaeological Society. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel, Addison P., Steven A. Katz, Marcus Lewis, and Elizabeth Wilk. 2023. Working with Indigenous Site Monitors and Tribal IRBs: Practical Approaches to the Challenges of Collaborative Archaeology. Advances in Archaeological Practice 11: 224–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkness, Verna J., and Ray Barnhardt. 1991. First Nations and Higher Education: The Four R’s—Respect, Relevance, Reciprocity, Responsibility. Journal of American Indian Education 30: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kovach, Margaret. 2009. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laluk, Nicholas. 2025. Indigenous Activism and Archaeology: An Ndee Perception. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laluk, Nicholas C., Lindsay M. Montgomery, Rebecca Tsosie, Christine McCleave, Rose Miron, Stephanie Russo Carroll, Joseph Aguilar, Ashleigh Big Wolf Thompson, Peter Nelson, Jun Sunseri, and et al. 2022. Archaeology and Social Justice in Native America. American Antiquity 87: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, Kent G. 2008. Collaborative Research Programs: Implications for the Practice of North American Archaeology. In Collaborating at the Trowel’s Edge: Teaching and Learning in Indigenous Archaeology. 2 vols. Edited by Stephen W. Silliman. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, Amerind Studies in Archaeology, pp. 211–27. [Google Scholar]

- li-Yanyuwa li-Wirdiwalangu (Yanyuwa Elders), Liam M. Brady, John Bradley, and Amanda Kearney. 2023. Jakarda Wuka (Too Many Stories): Narratives of Rock Art from Yanyuwa Country in Northern Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria. Sydney: Sydney University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lydon, Jane, and Uzma Z. Rizvi, eds. 2010. Handbook of Postcolonial Archaeology. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mallery, Garrick. 1886. Pictographs of the North American Indians: A Preliminary Paper. In Fourth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1882-’83. Compiled by John Wesley Powell. Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 4–256. [Google Scholar]

- Mallery, Garrick. 1893. Picture-writing of the American Indian. In Tenth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1888-’89. Compiled by John Wesley Powell. Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 3–822. [Google Scholar]

- Malotki, Ekkehart, and Ellen Dissanayake. 2018. Early Rock Art of the American West: The Geometric Enigma. Seattle: The University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martynec, Richard J. 1989. Hohokam, Patyan, or ?: Rock Art at Two Sites near Gila Bend, Arizona. In Rock Art Papers. 6 vols. Edited by Ken Hedges. San Diego: Museum of Man, pp. 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Martynec, Richard J., and Sandra Martynec. 2008. Charlie Bell Canyon: Petroglyphs and the Archaic Presence. In Fragile Patterns: The Archaeology of the Western Papaguería. Edited by Jeffrey H. Altschul and Adrianne G. Rankin. Tucson: SRI Press, pp. 330–46. [Google Scholar]

- McCleary, Timothy P. 2015. Crow Indian Rock Art: Indigenous Perspectives and Interpretations. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McGranaghan, Mark, and Sam Challis. 2016. Reconfiguring Hunting Magic: Southern Bushman (San) Perspectives on Taming and Their Implications for Understanding Rock Art. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 26: 579–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNiven, Ian. 2016. Theoretical Challenges of Indigenous Archaeology: Setting an Agenda. American Antiquity 81: 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNiven, Ian, and L. Russell. 2005. Appropriated Pasts: Indigenous Peoples and the Colonial Culture of Archaeology. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mengden, Walter H., IV. 2017. Indigenous People, Human Rights, and Consultation: The Dakota Access Pipeline. American Indian Law Review 41: 441–66. [Google Scholar]

- Menzies, Allyson K., Ella Bowles, Deborah McGregor, Adam T. Ford, and Jesse N. Popp. 2024. Sharing Indigenous Values, Practices and Priorities for Transforming Human-Environment Relationships. People & Nature 6: 2109–25. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Robert. 2015. Consultation or Consent: The United States’ Duty to Confer with American Indian Governments. North Dakota Law Review 91: 37–98. [Google Scholar]

- Morwood, Mike J., and Douglas R. Hobbs, eds. 1992. Rock Art and Ethnography. Occasional Paper No. 5. Melbourne: Australian Rock Art Research Association. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. 2025. College Enrollment Rates. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cpb/college-enrollment-rate (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Nicholas, George P. 2008. Native ynetteeoples and Archaeology. In Encyclopedia of Archaeology. Edited by Deborah M. Pearsall. New York: Academic Press, pp. 1660–69. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, George P., and Nola Markey. 2015. Traditional Knowledge, Archaeological Evidence, and Other Ways of Knowing. In Material Evidence: Learning from Archaeological Practice. Edited by Robert Chapman and Alison Wylie. New York: Routledge, pp. 287–307. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, George P., and Thomas D. Andrews. 1997. Indigenous Archaeology in the Postmodern World. In At a Crossroads: Archaeologists and First Peoples in Canada. Edited by Geore P. Nicholas and Thomas D. Andrews. Burnaby: Archaeology Press, Simon Fraser University, pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, George P., Claire Smith, and Kellie Pollard. 2024. Whose Information? Decolonizing Indigenous Intellectual Property in Archaeological and Heritage Management Contexts. The SAA Archaeological Record 24: 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas, George P., and Lindsey M. Montgomery. 2023. Indigenous Archaeology. In Encyclopedia of Archaeology, 2nd ed. 1 vols. Edited by Peter F. Biehl and Maria-Luz Endere. Cambridge: Academic Press, pp. 505–18. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, Emma S. 2017. Standing Up for Inherent Rights: The Role of Indigenous-Led Activism in Protecting Sacred Waters and Ways of Life. Society & Natural Resources 30: 537–53. [Google Scholar]

- Pantema Lewis, Leroy, and Lorna Gail LaDage. 2015. A Hopi Flute Clan Migration Story: A Hopi Elder Interprets Rock Art Through Clan Tradition, Self-published.

- Paradies, Yin C. 2006. Beyond Black and White: Essentialism, Hybridity, and Indigeneity. Journal of Sociology 42: 355–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, Carol. 2016. Petroglyphs of Western Colorado and the Northern Ute Indian Reservation as Interpreted by Clifford Duncan. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society Press. [Google Scholar]

- Porr, Martin, and Hannah Rachel Bell. 2012. ‘Rock-art’, ‘Animism’ and Two-way Thinking: Towards a Complementary Epistemology in the Understanding of Material Culture and ‘Rock-art’ of Hunting and Gathering People. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 19: 161–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, James M. 2004. The Creation of Person, the Creation of Place: Hunting Landscapes in the American Southwest. American Antiquity 69: 322–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rbeiro, Artur, and Christos Giamakis. 2022. On Class and Elitism in Archaeology. Open Archaeology 9: 20220309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Prince, Jordi A., Emily M. Blackwood, Jason A. Brough, Heather A. Landázuri, Elizabeth L. Leclerc, Monica Barnes, Kristina Douglass, María A. Gutiérrez, Sarah Herr, Kirk A. Maasch, and et al. 2022. An Intersectional Approach to Equity, Inequity, and Archaeology. Advances in Archaeological Practice 10: 382–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrinkhal, Rashwet. 2021. “Indigenous Sovereignty” and Right to Self-Determination in International Law: A Critical Appraisal. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 17: 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silliman, Stephen W., ed. 2008a. Collaborating at the Trowel’s Edge: Teaching and Learning in Indigenous Archaeology. 2 vols. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, Amerind Studies in Archaeology. [Google Scholar]

- Silliman, Stephen W. 2008b. Collaborative Indigenous Archaeology: Troweling at the Edges, Eyeing the Center. In Collaborating at the Trowel’s Edge: Teaching and Learning in Indigenous Archaeology. 2 vols. Edited by Stephen W. Silliman. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, Amerind Studies in Archaeology, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Silliman, Stephen W. 2010. The Value and Diversity of Indigenous Archaeology: A Response to McGhee. American Antiquity 75: 217–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Benjamin, Knut Helskog, and David Morris. 2012. Working with Rock Art: Recording, Presenting and Understanding Rock Art Using Indigenous Knowledge. Rock Art Research Institute Monograph No. 4. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Claire, Heather Burke, Jordan Ralph, Kellie Pollard, Alice Claire Gorman, Christopher John Wilson, Steve Hemming, Daryl Rigney, Daryl Lloyd Wesley, Michael Morrison, and et al. 2019. Pursuing Social Justice Through Collaborative Archaeologies in Aboriginal Australia. Archaeologies 15: 536–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Claire, and H. Martin Wobst, eds. 2005. Indigenous Archaeologies: Decolonizing Theory and Practice. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Society for American Archaeology. 2020. 2020 SAA Needs Assessment. Available online: https://ecommerce.saa.org/SAAMember/Members_Only/2020_Needs_Assessment.aspx (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Solometo, Julie, Wesley Bernardini, Mowana Lomaomvaya, and Katelyn J. Bishop. 2021. Petroglyphs of the Hopi Mesas. In Becoming Hop: A History. Edited by Wesley Bernardini, Stewart B. Koyiyumptewa, Gregson Schachner and Leigh Kuwanwisiwma. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, pp. 239–59. [Google Scholar]

- Spivey-Faulkner, S. Margaret. 2024. Rubber Yardsticks: Emic Methods in Indigenous Archaeology. In Indigenizing Archaeology: Putting Theory into Practice. Edited by Emily C. Van Alst and Carleton Shield Chief Gover. Gainesville: Univerity Press of Florida, pp. 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Steeves, F. Paulette. 2020. Indigenous Method and Theory in Archaeology. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Edited by Claire Smith. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 5696–705. [Google Scholar]

- Steward, Julian H. 1929. Petroglyphs of California and Adjoining States. University of Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 24: 47–238. [Google Scholar]

- Steward, Julian H. 1936. Petroglyphs of the United States. In Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution Showing the Operations, Expenditures, and Condition of the Institution for the Year Ending June 30, 1936. Compiled by Charles G. Abbott. Washington: Government Printing Office, Smithsonian Institution Publication 3405, pp. 405–26. [Google Scholar]

- Steward, Julian H. 1942. The Direct Historical Approach to Archaeology. American Antiquity 7: 337–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffle, Richard, Kathleen Van Vlack, Alannah Bell, and Bianca Eguino Uribe. 2024. Storied Rocks: Portals to Other Dimensions. Arts 13: 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supernant, Kisha, Jane Eva Baxter, Natasha Lyons, and Sonya Atalay, eds. 2020. Archaeologies of the Heart. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Tapper, Bryn, Oscar Moro AbadÍa, and Dagmara Zawadzka. 2020. Representation and Meaning in Rock Art: The Case of Algonquian Rock Images. World Archaeology 52: 446–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taçon, Paul S. C., Suzanne Thompson, Kate Greenwood, Andrewa Jalandoni, Michael Williams, and Maria Kottermair. 2022. Marra Wonga: Archaeolgoical and Contemporary First Nations Interpretations of One of Central Queensland’s Largest Rock Art Sites. Australian Archaeology 88: 159–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennberg, Monica. 2010. Indigenous Peoples as Intenational Political Actors: A Summary. Polar Record 46: 264–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Ashleigh, and Skylar Begay. 2023. A Model for Tribal Collaboration at Archaeology Southwest. Available online: https://www.archaeologysouthwest.org/pdf/Archaeology-Southwest-Tribal-Collaboration-Model.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Trafzer, Clifford E. 2012. Quechan Indian Historic Properties of Traditional Lands on the Yuma Proving Ground. Report prepared for the U.S. Army, Yuma Proving Ground. Riverside: California Center for Native Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, Roxanne, Liam M. Brady, Sebastien Katuk, Paul S. C. Taçon, François-Xavier Ricaut, and Matthew G. Leavesley. 2021. Agency, Affect and Archaeologist: Transforming Place with Rock Art in Auwim, Upper Karawari Arafundi Region, East Sepik, Papua New Guinea. Rock Art Research 38: 183–94. [Google Scholar]

- Tsosie, Ranalda L., Anne D. Grant, Jennifer Harrington, Ke Wu, Aaron Thomas, Stephan Chase, D’Shane Barnett, Salena Beaumont Hill, Annjeanette Belcourt, Blakely Brown, and et al. 2022. The Six Rs of Indigenous Research. Tribal College: Journal of American Indian Higher Education 33: 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Van Alst, Emily C. 2024. Indigenizing Rock Art Research: Indigenous Archaeological Methods to (Re)Contextualize and (Re)Claim Rock Art Sites. In Indigenizing Archaeology: Putting Theory into Practice. Edited by Emily C. Van Alst and Carleton Shield Chief Gover. Gainesville: Univerity Press of Florida, pp. 125–38. [Google Scholar]

- Van Alst, Emily C., and Carleton Shield Chief Gover, eds. 2024a. Indigenizing Archaeology: Putting Theory into Practice. Gainesville: Univerity Press of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Van Alst, Emily C., and Carleton Shield Chief Gover. 2024b. Indigenizing Archaeology: Putting Theory into Practice. In Indigenizing Archaeology: Putting Theory into Practice. Edited by Emily C. Van Alst and Carleton Shield Chief Gover. Gainesville: Univerity Press of Florida, pp. xix–xxxi. [Google Scholar]

- Van Schilfgaarde, Lauren. 2020. The Need for Confidentiality Within Tribal Cultural Resource Protection. Los Angeles: UCLA School of Law, Native Nations Law & Policy Center. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Henry D. 1983. The Mortars, Petroglyphs, and Trincheras on Rillito Peak. Kiva 48: i-246. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Henry D. 1989. Archaeological Investigations at Petroglyph Sites in the Painted Rock Reservoir Area, Southwestern Arizona. Technical Report No. 89-5. Tucson: Institute for American Research. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Henry D. 2008. The Petroglyphs of Atlatl Ridge, Tortolita Mountains, Pima County, Arizona. In Life in the Foothills: Archaeological Investigations in the Tortolita Mountains of Southern Arizona. Edited by Deborah A. Swartz. Anthropological Papers No. 46. Tucson: Center for Desert Archaeology, pp. 159–231. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Henry D., and James P. Holmlund. 1986. Petroglyphs of the Picacho Mountains, South Central, Arizona. Anthropological Papers No. 6. Tucson: Institute for American Research. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, Joe. 2000. Indigenous Archaeology: American Indian Values and Scientific Practice. Walnut Creek: AltaMira. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, Joe. 2011. Indigenous Archaeology as Complement to, Not Separate From, Scientific Archaeology. Jangwa Pana 10: 46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, James T., Aaron J. Young, Angela Garcia-Lewis, Cristin Lucas, and Shannon Plummer. 2022. Respectful Terminology in Archaeological Compliance. Advances in Archaeological Practice 10: 140–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Zion. 2020. Kwatsáan Culture in Symbols. Archaeology Southwest Magazine 34: 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting, Brian. 2024. Community-led Investigations of Unmarked Graves at Indian Residential Schools in Western Canada—Overview, Status Report and Best Practices. Archaeological Prospection 31: 403–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, David S. 1982. The Study of North American Rock Art: A Case Study from South-Central California. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S. 2000. Response to Quinlan. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 22: 108–29. [Google Scholar]

- Whitley, David S., J. D. Lancaster, and Andrea Catacora. 2025. Beyond Correlation to Causation in Hunter-Gatherer Ritual Landscapes: Testing an Ontological Model of Site Locations in the Mojave Desert, California. Arts 14: 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Shawn. 2008. Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods. Halifax: Fernwood. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Aaron M. 2014. Religion on the Rocks: Hohokam Rock Art, Ritual Practice, and Social Transformation. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Aaron M. 2018. Assessing the Stability and Sustainability of Rock Art Sites: Insight from Southwestern Arizona. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 25: 911–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Aaron M. 2022. Under the Halo of Spirit Mountain: A Cultural and Historical Overview of the Proposed Avi Kwa Ame National Monument, Southern Clark County, Nevada. BLM Report 5-2509. Technical Report 2022-102. Tucson: Archaeology Southwest. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Aaron M., ed. 2020. ‘Iihor Kwsnavk: Connecting and Collaborating in the Great Bend of the Gila. Archaeology Southwest Magazine, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Aaron M., and John R. Welch. 2025. “A Mark by Any Other Name…”: Reconciling Historical and Descendent Terms and Concepts for Indigenous Petroglyphs and Pictographs. American Antiquity, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Aaron M., and Maren P. Hopkins. 2016. The Great Bend of the Gila: Contemporary Native American Connections to an Ancestral Landscape. Technical Report 2015–101. Tucson: Archaeology Southwest. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Aaron M., Lorey Cachora, and Nathalie Brusgaard. 2024. An Ecology of the Patayan/Yuman Dreamland. In Sacred Southwestern Landscapes: Archaeologies of Religious Ecology. Edited by Aaron M. Wright. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, pp. 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Aaron M., Pat H. Stein, Barnaby V. Lewis, and William H. Doelle. 2015. The Great Bend of the Gila: A National Significant Cultural Landscape. Tucson: Archaeology Southwest. [Google Scholar]

- Wylie, Alison. 2015. A Plurality of Pluralisms: Collaborative Practice in Archaeology. In Objectivity in Science: New Perspectives from Science and Technology Studies. Edited by Flavia Padovani, Alan Richardson and Jonathan Y. Tsou. Cham: Springer, pp. 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, Donna, Diana Berzina, and Aaron Wright. 2022. Protecting a Broken Window: Vandalism and Security at Rural Rock Art Sites. The Professional Geographer 74: 384–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, Annie, Richard Daly, and Chris Arnett. 1993. They Write Their Dream on the Rocks Forever: Rock Writings in the Stein River Valley of British Columbia. Vancouver: Talonbooks. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M. Jane. 1988. Signs from the Ancestors: Zunic Cultural Symbolism and Perceptions of Rock Art. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, Larry J., and Margaret Conkey. 2024. Different Understandings? The Colonialist Implications of Basic North American Archaeology Terminology. The SAA Archaeological Record 24: 18–23. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wright, A.M. Indigenous Archaeology, Collaborative Practice, and Rock Imagery: An Example from the North American Southwest. Arts 2025, 14, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030053

Wright AM. Indigenous Archaeology, Collaborative Practice, and Rock Imagery: An Example from the North American Southwest. Arts. 2025; 14(3):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030053

Chicago/Turabian StyleWright, Aaron M. 2025. "Indigenous Archaeology, Collaborative Practice, and Rock Imagery: An Example from the North American Southwest" Arts 14, no. 3: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030053

APA StyleWright, A. M. (2025). Indigenous Archaeology, Collaborative Practice, and Rock Imagery: An Example from the North American Southwest. Arts, 14(3), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030053