Predation, Propitiation and Performance: Ethnographic Analogy in the Study of Rock Paintings from the Lower Parguaza River Basin, Bolivar State, Venezuela

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Rock Art in the Parguaza River Basin

2.1. The Parguaza Basin

2.2. Rock Art Sites in the Parguaza

3. Methods: Defining the Stylistic Sequence of Rock Paintings in the Parguaza Region

4. Placing the Rock Art in a Cultural Context

4.1. Ethnographic Analogy and the Search for Meaning

4.2. Continuity and Disruption in the Parguaza Rock Art Sequence

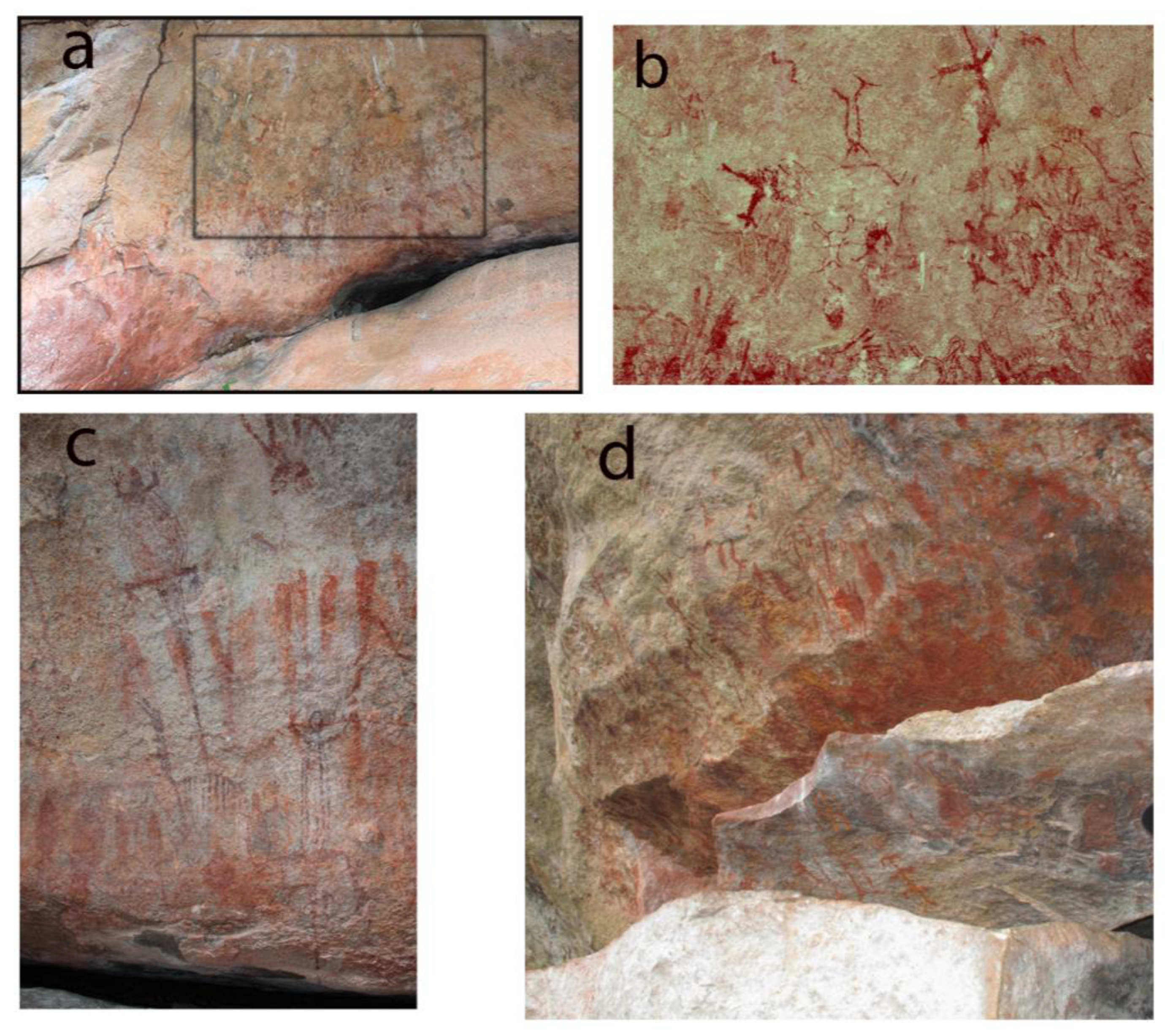

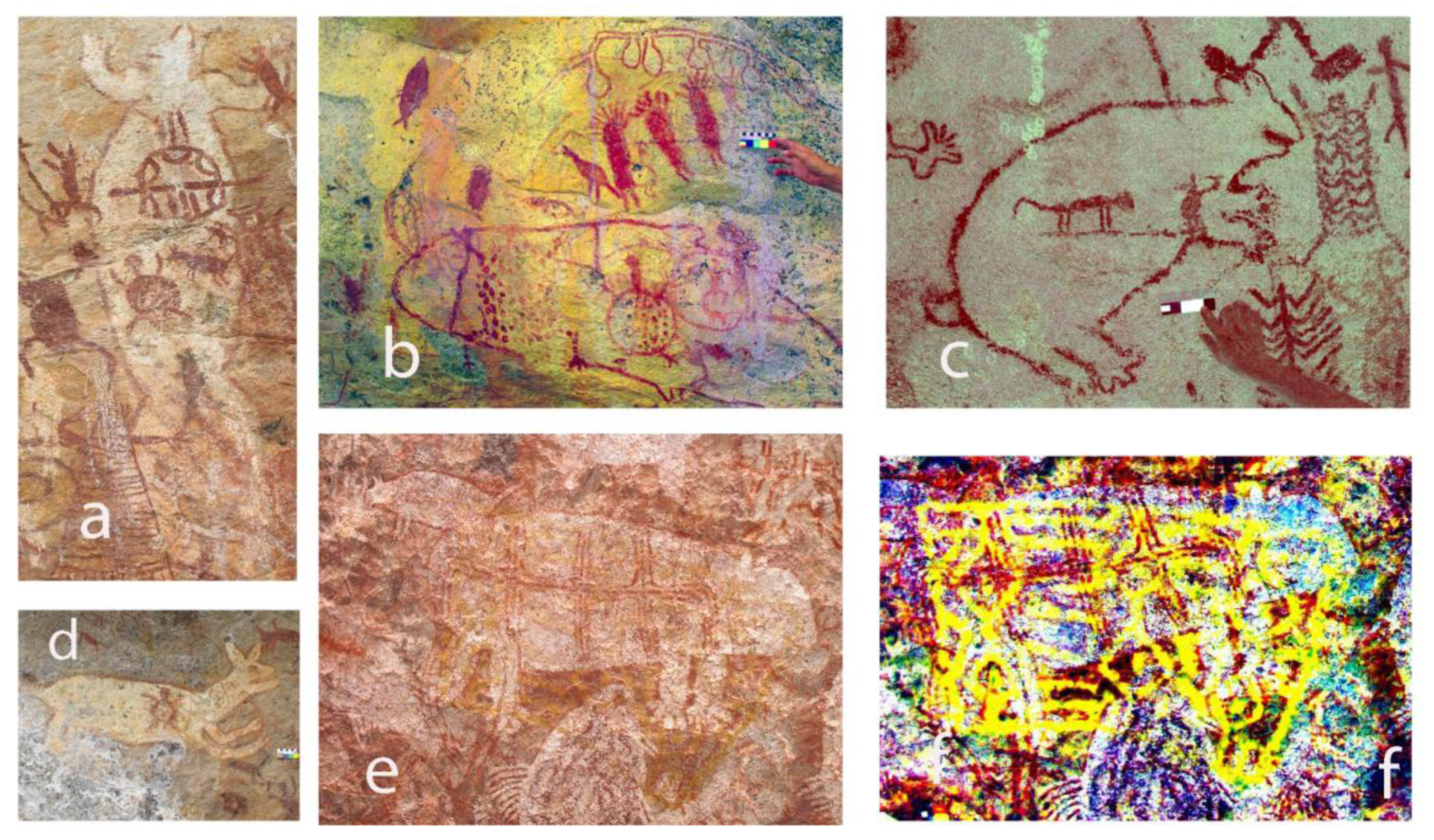

- Pre-ceramic occupations. These may have lasted several millennia, characterized by sporadic painting at rock shelters in the Parguaza area and beyond, suggesting a widespread sharing of symbolic representation. Zoomorphic elements include the detailed rendering of reptiles, large, long-legged birds with outspread wings, interior-lined fish, and depictions of small quadrupeds. A few representations of highly stylized anthropomorphs are also present. No interaction is seen between the figures, and no superpositioning is noted. It is difficult to assess the types of activity associated with these manifestations, but apparently, there was no emphasis on large, organized ritual celebrations, just as you would expect from small-scale populations.

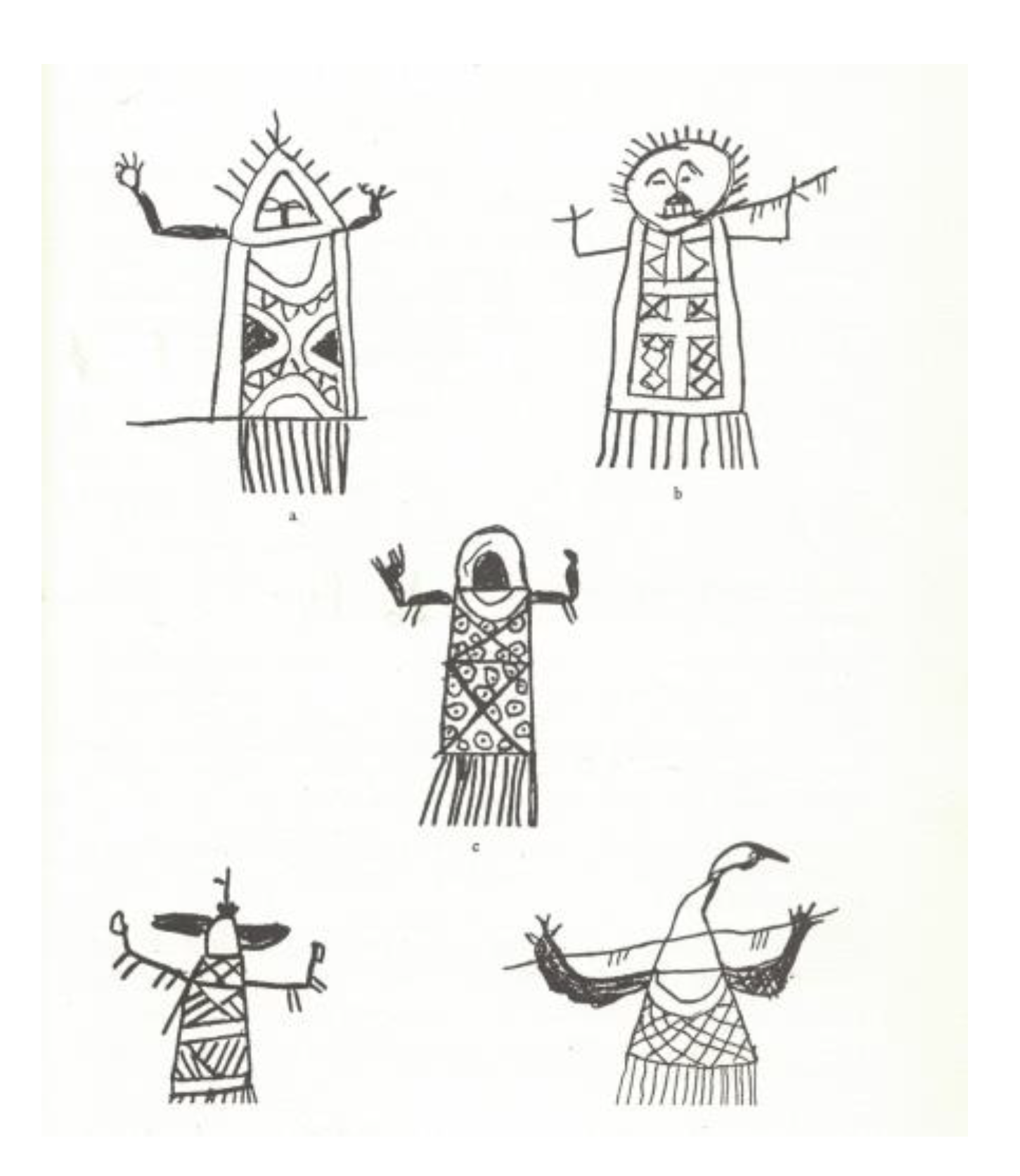

- Early ceramic occupations. The sudden advent of new painting technology, content, and frequency associated with style/periods 3 and 4 signals a rupture with previous traditions. The emphasis on carefully executed, costumed anthropomorphs and scenes of interacting figures portraying an array of activities, including flute-playing, dancing, hunting, fishing, and trapping, signals the appearance in the region of more sedentary societies, with a novel cosmovision that may have coincided with the arrival of ceramic-bearing Arawakan peoples and the hierarchical, ritual complex we know today as the Yuruparí or Kuwai, widely distributed throughout the Northwest Amazon and beyond. This shift has its counterpart in many of the petroglyphs found along the Orinoco and tributaries, with similar motifs, but with far greater visibility that suggests a different function for the sites. We will discuss this proposal further below.

- Late ceramic occupations. The final shift in the rock art of the Parguaza entails a notable change in the conception and execution of the paintings, where the planning and carrying out of carefully rendered anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures and scenes are replaced by an increasing emphasis on hastily painted geometric and abstract designs, and the appearance of paired figures painted in contrasting colors. Ghost figures, hunting/trapping scenes, and massive displays of zoomorphs are no longer present. The emphasis on duality indicates a shift in cosmology that may coincide with the influx of Cariban-speaking communities into the area.11 It may also be associated with the appearance of ceramics of the Valloid tradition, in which little attention is paid to decorative technique, in contrast to earlier Saladoid and Arauquinoid traditions. It is not clear whether the more frequent use of the sites as burial repositories dates to this shift or whether it is a more recent reutilization of the caves, both with and without rock art, by present-day indigenous communities, such as the Huotthüha and Mapoyo.

5. The Yuruparí Ritual Complex and Its Expression in the Rock Art of the Parguaza

5.1. The Yuruparí Ritual Complex

… it is necessary to explore the importance of indigenous understandings of breath and breathing as expressions of life-force and the associated meanings of wind instruments as cultural tools for channelling this life-force into activities designed to collectivise shamanic abilities to return to life from death and to ensure the continued fertility of animal nature as well as the regeneration of human social worlds. Collective performances of wind instruments are closely related to shamanic powers of killing, dying and returning to life, which invoke natural processes that are simultaneously concerned with the reproductive behaviours of ‘animal’ species—fish, birds, game animals and various spirits—and images of predatory violence (Hill 2013, p. 324)

5.2. Rock Art Associations with the Yuruparí Complex

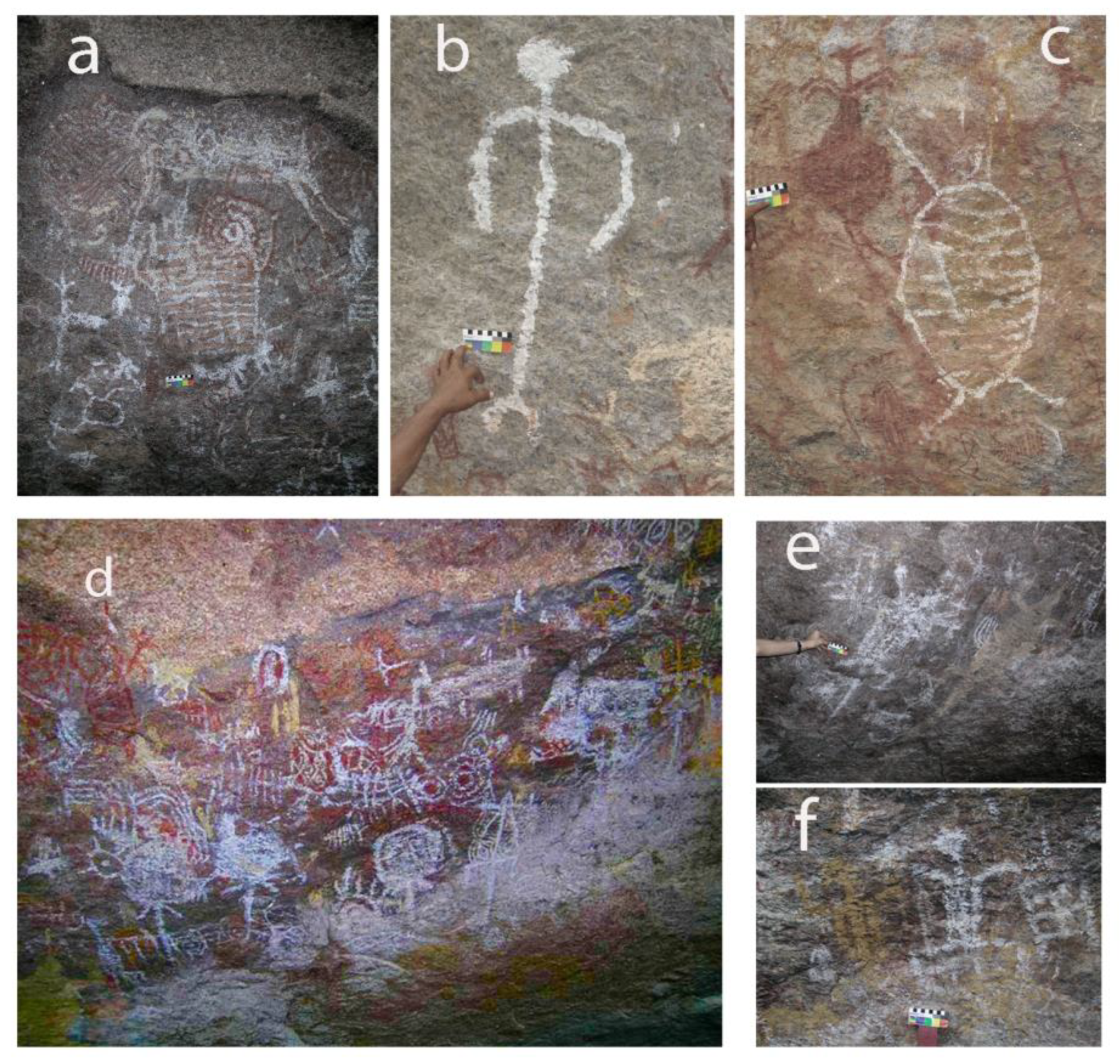

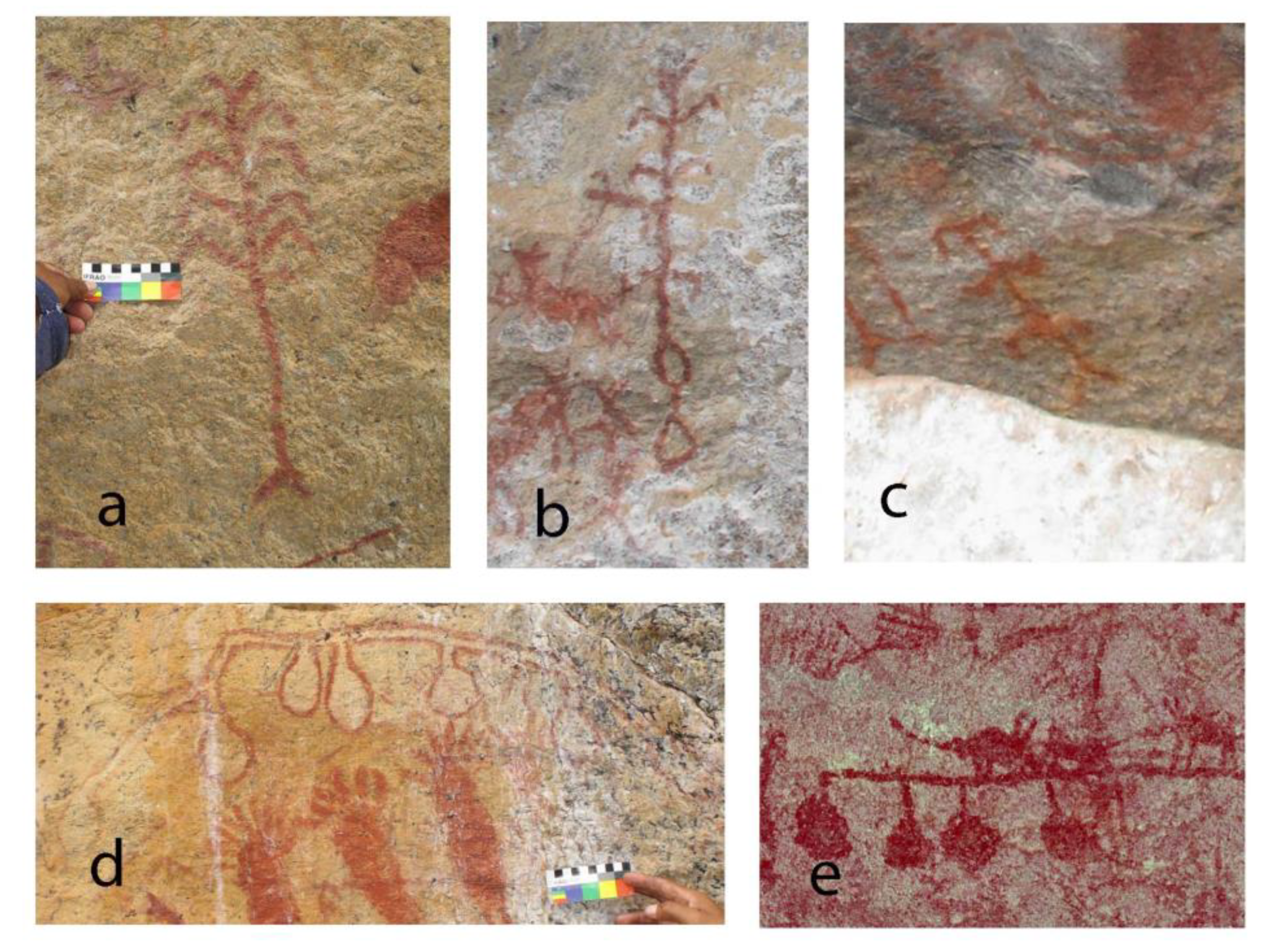

- These styles coincide with the proliferation of motifs associated with masked figures and musical instruments, including flutes and maracas, and lines of dancers that signal more organized ritual practices compared to those portrayed in earlier periods. (see Figure 12)

- The variety of designs on the body of the masked figures and the assortment of headdresses may point to a hierarchy of participants, each with specific roles in the ceremonies, such as those illustrated in the ethnographic literature (Goulard and Karadimas 2011; Koch-Grünberg [1925] 2008, 2010; Mansutti Rodríguez 2006, 2019) (Figure 20).

- The hunting and fishing scenes and the numerous depictions of anthropomorphic, zoomorphic, and theriomorphic figures speak to the preoccupation with the complex relations between humans and non-humans and the capacity for transformation and transmutation in a multiverse populated by visible and invisible agents (Severi 2014) (see Figure 16).

- An almost exclusive representation of male or non-gendered anthropomorphs points to the exclusivity of the ritual practices carried out at the sites on the Parguaza, possibly associated with male initiations. As we saw in the previous section, the sight of aerophones (and the identity of masked dancers) was prohibited for women and non-initiated members of the community. The depiction of falling figures may refer to the ritual suicides enacted because of the violation of the proscriptions (see Figure 13d).

- The seeming emergence of multiple figures out of crevices or openings in the rock suggests the ‘calling out’ of beings by the owners of species from their otherworldly spaces. The placement of paintings at several of the Parguaza sites takes advantage of holes, cracks, or other features of the rock to show interaction with the supporting medium. There are frequent references in the ethnographic literature to caves and mountains as the “maloca” or home of spirit beings and gods (Overing and Kaplan 1988, pp. 393–94; Mansutti Rodríguez 2012; Scaramelli 1992, pp. 47–49) (see Figure 17). This is a common feature of rock art associated with shamanism worldwide (see, for example, Rozwadowski 2017; Stoffle et al. 2024).

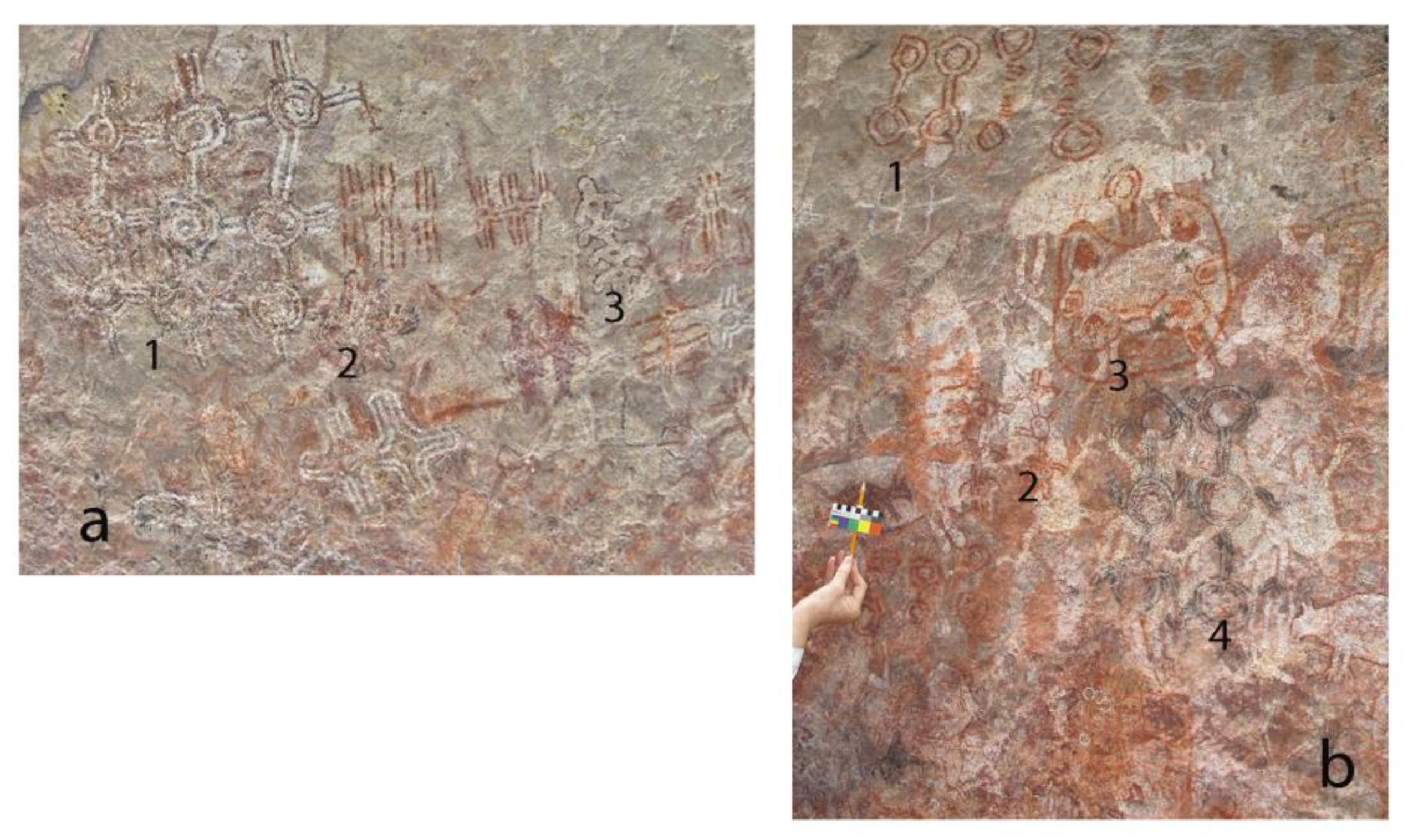

- The careful superpositioning of figures within the bodies of existing paintings and the displays of massive numbers of certain species, such as fish, suggests the “piling on of names” or vertical axis of chanting referred to by Hill and Hugh-Jones above. The multiple repetition of figures and the layering of motifs could emulate the chanting of a series of names, spirits, species, etc., in the context of rituals carried out in the rock shelters (Figure 21).

- Geometric motifs, such as concentric circles or rhombuses, outlined crosses, and other designs like those found on baskets and body paint may be translational depictions of mythical elements, fragments of chants and songs, that accompany the rituals. Although we are limited to the visual aspects of the past ritual practices in the rock art sites, this interpretation of these motifs reminds us that music and chanting played a fundamental role in ceremonies.15

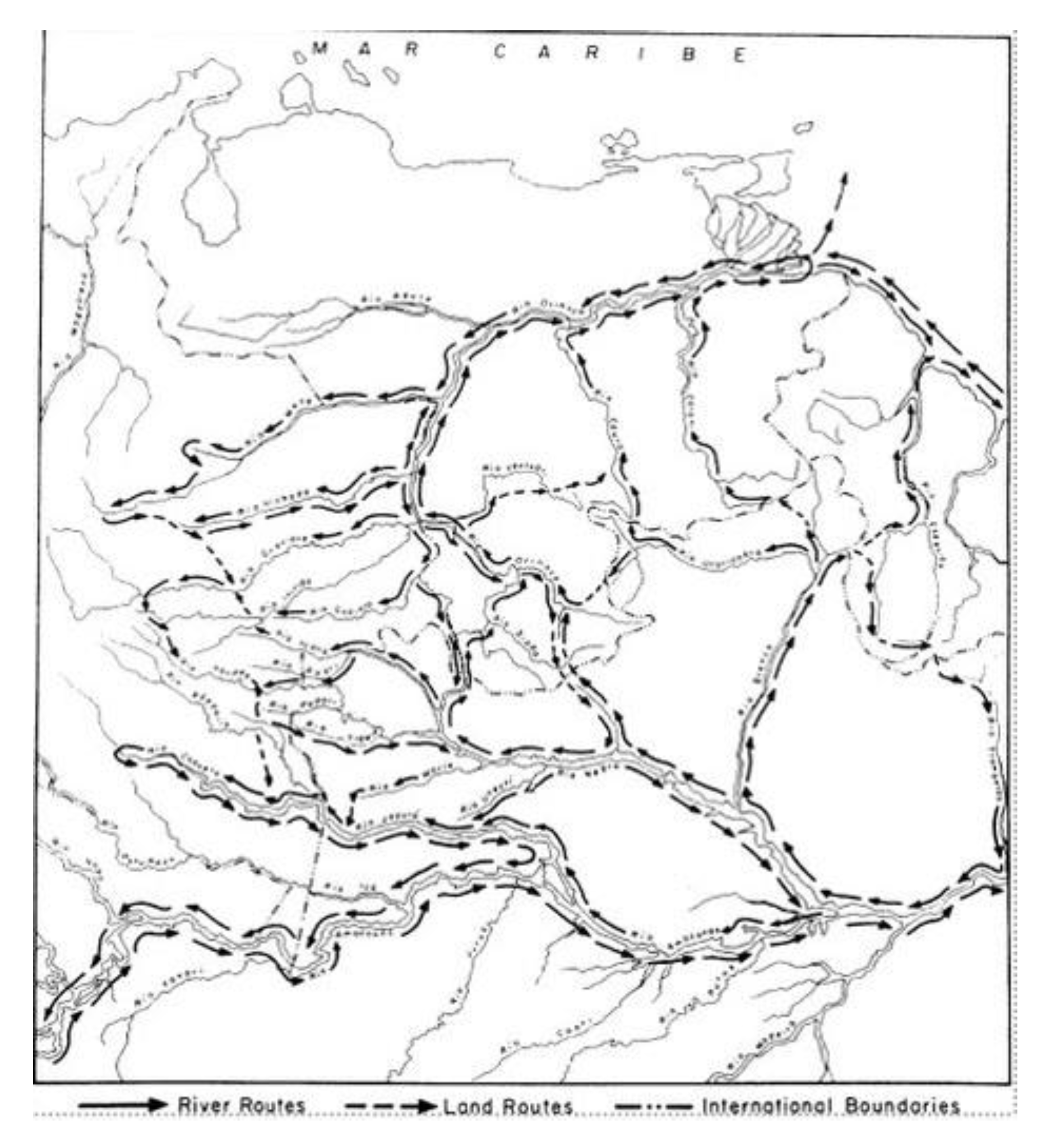

- Many motifs of the style 4 paintings have a broad distribution throughout the Northwest Amazon and Orinoco, suggesting an interaction area associated with the initial Arawakan expansion that, at the same time, may have had local expressions, such as that found in style 3 of the Parguaza. Common to all these areas are the abundant and diverse zoomorphic, anthropomorphic, and theriomorphic depictions, hunting and fishing scenes, masked figures, groups of dancers and figures in attitudes of supplication, geometric and abstract designs like those used in body paint, basketry, and textiles. Red monochrome figures predominate this style at sites throughout the region (Greer 1995; Iriarte et al. 2022; Hampson et al. 2024; Lozada Mendieta et al. 2024). Vidal (2000, Figures 2 and 3) has reconstructed the sacred routes associated with the Kuwai oral traditions that include a vast area covering the NW Amazon and Guayana (see also Hill 2011, Figure 13.1 and 13.2). This area coincides with the predominantly fluvial route of the northern part of the Arawakan exchange system around AD 900 illustrated by Hornborg and Eriksen (2011, Map 6.1) (Figure 22).

- The similarity of certain motifs at different sites in the Parguaza region suggests the visitation of sites by some of the same artists. At the same time, each site has specific content that points to a specialized function or local tradition. This recalls the axes of the Yuruparí ritual, in which the horizontal axis entails physical or shamanic visions of visitation to the different sites named in the chants (Hill 2011; Hugh-Jones 2016; Wright et al. 2017; Vidal 2000, p. 644). This is most clearly expressed in the numerous petroglyph sites that are found along the course of the Orinoco (González Ñáñez 2020; Wright et al. 2017). Recent research on giant petroglyphs in the Middle and Upper Orinoco (Riris et al. 2024) shows a stylistic similarity between motifs found in the monumental petroglyph panels and ceramics of the Arauquinoid and Valloid series. Several of the motifs found in the petroglyphs are also found in the style 4 paintings of the Parguaza sequence: masked figures, concentric circles, stylized birds and anthropomorphic figures, mammals, and lizards, suggesting broad contemporaneity. Nonetheless, the emphasis on snakes in the monumental art supports the association of these sites with the myths of Tukano and Arawak-speaking groups who tie their origins to the emergence, travels, and resting places of ancestral serpent-canoes (Riris 2017; Riris et al. 2024, p. 733). This suggests two rock art traditions, one expressed as highly visible petroglyphs in a riverine orientation that commemorate the cosmic origins and horizontal axis of the Yuruparí, and the other, expressed in paintings, associated with more restricted ritual performance in rock shelters of difficult access.

6. Animals, Plants, and the Longue-Durée

This ceremony consolidates alliances between the shamans and their communities with the masters who control animals and plants exploited by the Piaroa people, facilitates men’s expropriations and limits women’s power to the domestic sphere, and shifts a society with no major hierarchical organizations into a highly hierarchical one as long as the ceremony is occurring (Mansutti Rodríguez 2012, p. 46).

7. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Recent painting of graffiti at some sites, with the use of personal names and words such as “community” or “indigenous” has been noted, indicating ongoing visitation to the sites. Unfortunately, unscrupulous visitors have looted some sites, and burial bundles have been disturbed or removed, leading to reticence on the part of some indigenous communities to permit access to outsiders. |

| 2 | Colorado River tribes, for example, made large, pecked panels located at the base of Spirit Mountain, the site of the mythic creation of the world, where shamans travel to seek spiritual power on vision quests; boys created small, incised rocks with entoptic motifs as part of their puberty initiations; and large, figurative geoglyphs created at the site of specific mythic events were used for group pilgrimages led by shamans (Whitley 2023, pp. 286–88). |

| 3 | We have not included the toponyms and location of the rock art sites out of respect for the wishes of the communities who continue to occupy the area and who utilize many of the sites for burial practice or other ritual activities. The code names we use to refer to our project survey designation. |

| 4 | This is an ongoing project, and we are reporting preliminary results only. |

| 5 | Caputo Jaffe (2022) has interpreted similar clusters found in the nearby cave of Punta Brava as animals or humans in a canoe adjacent to representations of palm trees. She has associated these iconographies with the Tamanaco myth of the great flood. |

| 6 | Some motifs from BO-29, such as the snake-necked, knobby-kneed, heron fisher, are nearly identical to motifs found in Nueva Tolima (Hampson et al. 2024, figure 7), and the bipedal deer, large birds with outspread wings, lines of zoomorphs on horizontal lines being lassoed or prod by humans, and lines of dancers and supplicant humans are also found in the Parguaza and at La Lindosa and Chiribiquete in Colombian. |

| 7 | This conception of motifs as the “social skin” of the rock walls echoes the conception of the designs used by the Yekwana, a Carib-speaking group of the Upper Orinoco. Severi, drawing from Guss (1989), states [T]he twill-plaited baskets, decorated with designs that every man has to weave to prepare for and confirm his marriage (and to accomplish his male initiation), are strictly connected with the ritual relations that humans entertain with nonhuman and mythical beings. The baskets incorporate a complex system of symbols that acts as an index and key to the rest of the culture….Actually, baskets are generally said to be the property of nonhuman supernatural “masters”. However, this notion of property often becomes much stronger: baskets as artifacts are themselves said to be “embodiments” (Guss 1989, p. 102) of the mythical beings. Like the ancestral predators they incarnate, they are “living beings” that can attack humans. Their designs woven into their surface are the “body paints” that decorate the skin of the mythical predators (ibid.). (Severi 2014, pp. 48–49) |

| 8 | Both groups are known to use caves with no rock art for burials as well. |

| 9 | “Musicalisation, or the production of musical sounds as a way of socialising relations with affines, non-human beings and various categories of ‘others’, is perhaps best understood as a process of creating a naturalised social space in which human interactions are densely interwoven with the sounds and behaviours of fish and other non-human animal species” (Hill 2013, p. 327). |

| 10 | This is not to deny their important potential as indicators of past environments and biodiversity (Lozada Mendieta et al. 2024; Korpershoek et al. 2024; Pereira and de Sousa e Silva 2022; Tarble de Scaramelli et al. 2021). |

| 11 | This is an aspect that deserves treatment beyond the scope of this paper. Fausto (2021) has delved into the notion of the duality in indigenous images, opting to describe it as a “fold” rather than an expression of animistic interiority. “The textile operation of the fold would allow both the separation and articulation “of the two domains into which the indigenous cosmos is divided: the solar state, extensive and discrete, which humans and other ordinary beings inhabit, and the intensive, virtual state where spirits dwell. The double is thus a replica in another frequency, which allows us to think of the duplication of the person as an unfolding of a body into multiple intensive selves-others (as I argue for the Kuikuro case)” (Fausto 2021, p. 1246). |

| 12 | Hill (2013, p. 331) notes that these ceremonies are held during the first few weeks of the wet season to coincide with the massive spawning migrations of Leporinus fish: “Throughout the ceremony, the dancing of men and women to the sounds of flutes and trumpets was closely associated with the spawning behaviors of migrating schools of Leporinus and other fish species”. |

| 13 | “Among northern Arawak-speaking peoples, furthermore, there is a strong belief in the association of primordial shamans and spirits with material places (large boulders in the rivers, caves, hills, depressions in the rocks of the rivers) in this world. Thus, there are numerous ‘stone-houses’ situated throughout each phratry’s territory that are places of the ‘first fruits’ and their spirit owners, yoopinai spirits, the mountaintop sources of all fish. Several of these places require appropriate behaviour when they are approached, such as silence, avoidance of looks so as not to attract or disturb the spirits, because they may give humans sickness. Others are ‘stone houses’ associated with primordial shamans, where people can solicit their protection from sickness or misfortune” (Wright et al. 2017, p. 190). |

| 14 | As Carlos Fausto (2000, p. 934) has summarized, “Amazonian societies are primarily oriented toward the production of persons, not material goods; that is, their focus is not the fabrication of objects through labor, but of persons through ritual and symbolic work. Birth and mortuary rites, initiations and naming ceremonies, shamanic and warfare festivals, seclusions and displays are all means for producing persons, for conferring on them singularity, beauty, fertility, agency, and the capacity to interact with external entities, like spirits, deities, animals, and enemies.” |

| 15 | In ethnographic documentation of petroglyphs associated with the voyages of Kuwai, rounded and swirl shapes are interpreted as the musical sounds emitted from the body of Kuwai or as the designs of the face paint of Ámarru, mother of Kuwai (Wright et al. 2017, p. 196; González Ñáñez 2020, p. 128). |

| 16 | Heckenberger gives a list of elements of material culture associated with the Arawaks that includes “ball games, hammocks, bull-roarers, atlatls, sacred flutes, wooden benches, masks, and idols—what we might call a cultural aesthetic of heightned ritual” (Heckenberger 2002, p. 112). As we have seen, many of these elements can be found in the rock paintings associated with styles 3 and 4 in the Parguaza sequence. |

References

- Aceituno, Francisco Javier, Mark Robinson, Gaspar Morcote-Ríos, Ana María Aguirre, Jo Osborn, and José Iriarte. 2024. The peopling of Amazonia: Chrono-stratigraphic evidence from Serranía La Lindosa, Colombian Amazon. Quaternary Science Reviews 327: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceituno Bocanegra, Francisco J. 2010. El poblamiento temprano de la floresta húmeda de Colombia: Una síntesis regional para un modelo de poblamiento de la cabecera noroccidental de la cuenca del Amazonas. In Arqueologia amazônica. Edited by Edithe Pereira and Vera Guapindaia. Belém: MPEG/IPHAN/SECULT, pp. 16–33. [Google Scholar]

- Antczak, Andrzej, Bernardo Urbani, and Maria M. Antczak. 2017. Re-thinking the Migration of Cariban-Speakers from the Middle Orinoco River to North-Central Venezuela (AD 800). Journal of World Prehistory 30: 131–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barse, William P. 1990. Preceramic occupations in the Orinoco River valley. Science 250: 1388–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barse, William P. 2009. The early Ronquin paleosol and the Orinocan ceramic sequence. Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History 50: 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Pérez, Amed, and José Carlos Frantz. 2013. Petrografía, geoquímica y geocronología del granito de Parguaza en Colombia. Boletín de Geología 35: 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Brabec de Mori, Berndt, and Anthony Seeger. 2013. Introduction: Considering Music, Humans, and Non-humans. Ethnomusicology Forum 22: 269–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brites, Natasha. 1994. Espacios y tiempos sagrados: Tradiciones y ritos en las prácticas funerarias de los grupos Wánai y Wóthuja del sector Parguaza-Suapure, Edo. Bolívar. Undergraduate thesis, Escuela de Antropología, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas, Venezuela. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo Jaffe, Alessandra. 2022. Aproximación a las pictografías de Punta Brava y los registros de mitos diluvianos del Orinoco Medio. Revista Colombiana de Antropología 58: 139–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño-Uribe, Carlos. 2019. Chiribiquete. La Maloka Cósmica de los Hombres Jaguar. Bogota: Villegas Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Castaño-Uribe, Carlos, and Thomas Van der Hammen. 1998. El simbolismo pictórico de la serranía de Chiribiquete. In Parque Nacional Natural Chiribiquete: La peregrinación de los jaguares. Edited by Carlos Castaño Uribe. Bogotá: UAESPNN, Ministerio de Ambiente de Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- Cruxent, José M. 1946. Pinturas rupestres de El Carmen, en el río Parguaza, Estado Bolívar, Venezuela. Acta Científica Venezolana 2: 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cruxent, José M., and Irving Rouse. 1958–1959. An Archeological Chronology of Venezuela. Social Science Monographs 6 (2 vols.). Washington, DC: Pan American Union. [Google Scholar]

- De Valencia, Ruby, and Jeannine Sujo-Volsky. 1987. El diseño en los petroglifos venezolanos. Caracas: Fundación Pampero. [Google Scholar]

- Descola, Philippe. 1994. In the Society of Nature: A Native Ecology in Amazonia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Descola, Philippe. 2012. Beyond nature and culture: The traffic of souls. Journal of Ethnographic Theory 2: 473–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbin, Marshall. 1985. A survey of the Carib language family. In South American Indian Languages: Retrospect and Prospect. Edited by Manelis Klein Harriet E. and Louisa R. Stark. Austin: University of Texas Press, pp. 325–71. [Google Scholar]

- Fausto, Carlos. 2000. Of enemies and pets: Warfare and shamanism in Amazonia. American Ethnologist 26: 933–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausto, Carlos. 2021. The ruses of Amerindian Art: A reply. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 11: 1244–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausto, Carlos, and Eduardo G. Neves. 2018. Was there ever a Neolithic in the Neotropics? Plant familiarisation and biodiversity in the Amazon. Antiquity 92: 1604–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundaredes. 2023. Economía Paralela y el Daño Ambiental en el Arco Minero del Orinoco. Available online: https://fundaredes.org/informes/2023-EPA-eonomia-paralela-y-el-dano-ambiental-en-el-arco-minero-del-orinoco.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Galarraga, Alicia, Maritza Garicoechea, María Gabriela Montoto, Franz Scaramelli, and Kay Tarble. 2003. Estudio de los contextos culturales de la Cueva del Caño Ore, Edo. Bolívar. Boletín de la Sociedad Venezolana de Espeleología 37: 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gassón, Rafael. 2002. Orinoquia: The Archaeology of the Orinoco River Basin. Journal of World Prehistory 16: 237–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Ñáñez, Omar. 1980. Mitología Guarequena. Caracas: Monte Ávila. [Google Scholar]

- González Ñáñez, Omar. 1986. Sexualidad y Rituales de Iniciación entre los Indigenas Warekena del Río Guainía-Río Negro, TFA. Revista Montalbán 17: 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- González Ñáñez, Omar. 2020. La Lectura de las Piedras: Arte Rupestre y Culturas del Noroeste Amazónico. Boletín Antropológico 38: 107–41. [Google Scholar]

- Goulard, Jean-Pierre, and Dimitri Karadimas, eds. 2011. Masques des Hommes, Visages des Dieux. Paris: CNRS Éditions. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, John W. 1995. Rock art chronology in the Orinoco Basin of southwestern Venezuela. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, John W. 2001. Lowland South America. In Handbook of Rock Art Research. Edited by David Whitley. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greer, John W., and Mavis Greer. 2006. Human figures in the cave paintings of southern Venezuela. In International Rock Art Congress Proceedings 3, Vol. 21-3. Flagstaff: American Indian Rock Art, pp. 155–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, Robert G., Bruno David, Jean-Jacques Delannoy, Benjamin Smith, Augustine Unghangho, Ian Waina, Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation, Leigh Douglas, Cecilia Myers, Pauline Heaney, and et al. 2022. Superpositions and superimpositions in rock art studies: Reading the rock face at Pundawar Manbur, Kimberley, northwest Australia. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 67: 101442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guss, David M. 1989. To Weave and to Sing: Art, Symbol, and Narrative in the South American Rain Forest. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Halbmayer, Ernst. 2012. Amerindian mereology: Animism, analogy, and the multiverse. Indiana 29: 103–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson, Jamie, José Iriarte, and Francisco Javier Aceituno. 2024. ‘A World of Knowledge’: Rock art, ritual, and indigenous belief at Serranía de la Lindosa in the Colombian Amazon. Arts 13: 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, J. 2009. Image Enhancement Using dStretch. Available online: www.dStretch.com (accessed on 4 October 2024).

- Heckenberger, Michael J. 2002. Rethinking the Arawakan diaspora. In Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia. Edited by Jonathan D. Hill and Fernando Santos-Granero. Urbana: University of Illinois, pp. 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Henley, Paul. 2001. Inside and Out: Alterity and the Ceremonial Construction of the Person in the Guianas. In Beyond the Visible and the Material: The Amerindianization of society in the work of Peter Rivière. Edited by Larura M. Rival and Neil L. Whitehead. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 197–220. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Jonathan D. 1993. Keepers of the Sacred Chants: The Poetics of Ritual Power in an Amazonian Society. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Jonathan D. 1996. Ethnogenesis in the Northwest Amazon. In History, Power and Identity. Edited by Jonathan D. Hill. Iowa: University of Iowa Press, pp. 142–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Jonathan D. 2002. Shamanism, Colonialism and the Wild Woman: Fertility Cultism and Historical Dynamics in the Upper Río Negro Region. In Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia. Edited by Jonathan D. Hill and Fernando Santos Granero. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, pp. 223–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Jonathan D. 2011. Sacred landscapes as environmental histories in lowland South America. In Ethnicity in Ancient Amazonia: Reconstructing Past Identities through Archaeology, Linguistics, and Ethnohistory. Edited by Alf Hornborg and Jonathan D. Hill. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, pp. 259–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Jonathan D. 2013. Instruments of Power: Musicalising the Other in Lowland South America. Ethnomusicology Forum 3: 323–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Jonathan D., and Fernando Santos-Granero, eds. 2002. Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Jonathan D., and Robin M. Wright. 1988. Time, narrative and ritual. Historical interpretations from an Amazonian society. In Rethinking History and Myth: Indigenous South American Perspectives on the Past. Edited by Jonathan D. Hill. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, pp. 78–105. [Google Scholar]

- Hornborg, Alf, and Jonathan D. Hill, eds. 2011a. Ethnicity in Ancient Amazonia: Reconstructing Past Identities Through Archaeology, Linguistics, and Ethnohistory. Boulder: University of Colorado Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hornborg, Alf, and Jonathan D. Hill. 2011b. Introduction: Ethnicity in Ancient Amazonia. In Ethnicity in Ancient Amazonia: Reconstructing Past Identities through Archaeology, Linguistics, and Ethnohistory. Edited by Alf Hornborg and Jonathan D. Hill. Boulder: University of Colorado Press, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hornborg, Alf, and Love Eriksen. 2011. An attempt to understand Panoan ethnogenesis in relation to long-term patterns and transformations of regional interaction in Western Amazonia. In Ethnicity in Ancient Amazonia: Reconstructing Past Identities through Archaeology, Linguistics, and Ethnohistory. Edited by Alf Hornborg and Jonathan D. Hill. Boulder: University of Colorado Press, pp. 129–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hugh-Jones, Stephen. 2016. Writing on stone; writing on paper: Myth, history and memory in NW Amazonia. History and Anthropology 27: 154–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriarte, José, Mark Robinson, Francisco Javier Aceituno, Gaspar Morcote-Ríos, and Michael Ziegler. 2022. The Painted Forest: Rock Art and Archaeology in the Colombian Amazon. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, Harold J. 2009. Rock Art of Aruba. In Rock Art of the Caribbean. Edited by Michele Hayward, Lesley-Gail Atkinson and Michael A. Cinquino. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, pp. 175–87. [Google Scholar]

- Koch-Grünberg, Theodor. [1925] 2008. Del Roraima al Orinoco. Caracas: Ernesto Armitano Editores, Vol. III. First published 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Koch-Grünberg, Theodor. [1907] 2010. Petróglifos Sul-Americanos. Edited by Edithe Pereira. Belem/São Paulo: Museo Paraense Emílio Goeldi. First published 1907. [Google Scholar]

- Korpershoek, Mirte, Sally C. Reynolds, Marcin Budka, and Philip Riris. 2024. Old and New Approaches in Rock Art: Using Animal Motifs to Identify Palaeohabitats. Quaternary 7: 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathrap, Donald W. 1970. The Upper Amazon. Ancient Peoples and Places Series; London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Lozada Mendieta, Natalia, José R. Oliver, and Phillip Riris. 2016. Archaeology in the Átures Rapids of the Middle Orinoco, Venezuela: A research update. Archaeology International 19: 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozada Mendieta, Natalia, José R. Oliver, Sergio Estrada Villegas, Lizeth Stephany Guzmán, and Samuel Yung. 2024. Peces al lado y lado del Medio Orinoco: Biodiversidad en tres sitios arqueológicos de los llanos del Norte de Suramérica. In Fauna y Manifestaciones Rupestres en América Latina. Edited by Aline Lara Galicia and Carmen Pérez Maestro. Sevilla: Enredars Publicaciones, pp. 78–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lozada Mendieta, Natalia, Phillip Riris, and José R. Oliver. 2022. Beads and stamps in the Middle Orinoco: Archaeological evidence for interaction and exchange in the Atures Rapids from AD 1000 to 1480. Latin American Antiquity 34: 742–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansutti Rodríguez, Alexander. 2006. Warime: La Fiesta: Flautas, trompas y poder en el noroeste amazónica. Ciudad Guayana: Fondo Editorial Universidad Nacional Experimental de Guayana. [Google Scholar]

- Mansutti Rodríguez, Alexander. 2012. Yuruparí: Máscaras y Poder entre los Piaroas del Orinoco. Espaço Ameríndio 6: 46–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansutti Rodríguez, Alexander. 2019. Warime Piaroa, cuatro performances y un rito. Revista Colombiana de Antropología 55: 149–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansutti Rodríguez, Alexander, and Noël Bonneuill. 1994–1996. Dispersión y asentamiento interfluvial llanero: Dos razones de sobrevivencia en el Orinoco Medio del post-contacto. Antropológica 84: 43–72. [Google Scholar]

- Morey, Robert V., and Nancy Morey. 1975. Relaciones comerciales en el pasado en los Llanos de Colombia y Venezuela. Montalbán 4: 533–64. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, Ana Paula, Martin Porr, and Peter Veth. 2020. Recursivity in Kimberley Rock Art Production, Western Australia. In Places of Memory: Spatialised Practices of Remembrance from Prehistory to Today. Edited by Christian Hornm, Gustav Wollentz, Annette Haug and Gianpiero di Maida. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 137–49. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz Castiblanco, Guillermo. 2020. Estética amazónica y discusiones contemporáneas: El arte rupestre de la serranía La Lindosa, Guaviare—Colombia. Calle 14: Revista de Investigación en el Campo del Arte 15: 14–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, José R. 1989. The Archaeological, Linguistic and Ethnohistorical Evidence for the Expansion of Arawakan into Northwestern Venezuela and Northeastern Colombia. Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Overing, Joanna, and Alan Passes, eds. 2000. The Anthropology of Love and Anger: The Aesthetics of Conviviality in Native Amazonia. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Overing, Joanna, and M. R. Kaplan. 1988. Los Piaroa (Wóthuha). In Los Aborígenes de Venezuela. Edited by Walter Coppens. Etnología Contemportánea. Caracas: Fundación La Salle de Ciencias Naturales-Monte Ávila, vol. III, pp. 307–417. [Google Scholar]

- Páez, Leonardo. 2021. Arte Rupestre del Corredor Terrestre-Fluvial Negro-Orinoco-Lago de Valencia. Avances de Investigación. In Manifestacions Rupestres en América Latina. Instituto Universitario de Estudios sobre América Latina. Edited by A. Lara Galicia. Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, David G. 2012. Ethnography and history: The significance of social change in interpreting rock art. In Working with Rock Art: Recording, Presenting and Understanding Rock Art Using Indigenous Knowledge. Edited by Benjamin W. Smith, Knut Helskogand and David Morris. South Africa: Witts University Press, pp. 135–45. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, Edithe, and José de Sousa e Silva, Jr. 2022. Representations of Primates in Petroglyphs of the Brazilian Amazonia. In World Archaeoprimatology: Interconnections of Humans and Nonhuman Primates in the Past. Edited by Bernardo Urbani, Dionisios Youlatos and Andrzej Antczak. Cambridge Studies in Biological and Evolutionary Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 153–71. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, Miguel Á. 1983. Sobre un cementario Piaroa en Parguaza, Distrito Cedeño, Estado Bolivar. Boletín de la Sociedad Venezolana de Espeleología 20: 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, Miguel Á. 1992. Los últimos Wanai (Mapoyas). Contribución al conocimiento de otro pueblo amerindio que desaparece. Revista Española de Antropología Americana 22: 139. Available online: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/REAA/article/view/REAA9292110139A (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Perera, Miguel Á, and Hyram M. Moreno. 1984. Pictografías y cerámica de dos localidades hipogeas de la Penillanura del Norte T.F.A. y Dto. Cedeño, Estado Bolívar. Boletín de la Sociedad Venezolana de Espeleología 21: 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. 1971. Amazonian Cosmos: The Sexual and Religious Symbolism of the Tukano Indians. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. 1987. Shamanism and Art of the Eastern Tukanoan Indians. Leiden: E.J. Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Riris, Philip. 2017. On confluence and contestation in the Orinoco interaction sphere: The engraved rock art of the Atures Rapids. Antiquity 91: 1603–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riris, Philip, and José Oliver. 2019. Patterns of style, diversity, and similarity in Middle Orinoco rock art assemblages. Arts 8: 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riris, Philip, José Oliver, and Natalia Lozada Mendieta. 2024. Monumental snake engravings of the Orinoco River. Antiquity 98: 724–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, Pedro. 1993. Estudio Preliminar de los Petroglifos de Punta Cedeño, Caicara del Orinoco, Estado Bolívar. In Cobtribuciones a la Arqueología Regional de Venezuela. Edited by Francisco Javier Fernández and Rafael Gassón. Caracas: Asociación Venezolana de Arqueología, Fondo Editorial Acta Científica Venezolana, pp. 165–94. [Google Scholar]

- Roosevelt, Anna C. 1980. Parmana: Prehistoric Maize and Manioc Subsistence Along the Amazon and Orinoco. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse, Irving. 1985. Arawakan phylogeny, Caribbean chronology, and their implications for the study of population movement. Journal of New World Archaeology 5: 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rozwadowski, Andrzej. 2017. Travelling through the Rock to the Otherworld: The Shamanic ‘Grammar of Mind’ within the rock art of Siberia. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 27: 413–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanoja, Mario, and Iraida Vargas. 1970. La Cueva de “El Elefante”. Investigaciones Arqueológicas en el Bajo Orinoco: Estado Bolívar, Venezuela. Proyecto Orinoco, Informe 2. Caracas: Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas y Sociales, Universidad Central de Venezuela. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Granero, Fernando. 1998. Writing History into the Landscape: Space, Myth, and Ritual in Contemporary Amazonia. American Ethnologist 25: 128–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Granero, Fernando. 2002. The Arawakan Matrix: Ethos, Language, and History in Native South America. In Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia. Edited by Jonathan D. Hill and Fernando Santos-Granero. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Granero, Fernando. 2004. Arawakan sacred landscapes. Emplaced myths, place rituals, and the production of locality in Western Amazonia. In Kultur, Raum, Landschaft. Zur Bedeutung des Raumes in Zeiten der Globalitat. Edited by Ernst Halbmayer and Elke Mader. Frankfurt am Main: Brandes and Apsel, pp. 93–122. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Granero, Fernando. 2009. The Occult Life of Things: Native American Theories of Materiality and Personhood. Flagstaff: University of Arizona Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramelli, Franz. 1992. Las Pinturas Rupestres del Parguaza: Mito y Representación. Undergraduate thesis, Escuela de Antropología, FaCES, Univertro de Estudios Avanzasidad Central de Venezuela, Caracas, Venezuela. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramelli, Franz, and Kay Tarble. 1996. Contenido arqueológico y etnográfico de los sitios de interés espeleohistórico del Orinoco medio, Bolívar, Venezuela. Boletín de la Sociedad Venezolana de Espeleología 30: 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramelli, Franz, and Kay Tarble de Scaramelli. 2018. Rock art in the construction of landscape, Parguaza River Basin, Venezuela. In Archaeologies of rock art: South American perspectives. Edited by Andrés Troncoso, Felipe Armstrong and George Nash. London: Routledge, pp. 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Severi, Carlo. 2014. Transmutating beings: A proposal for an anthropology of thought. HAU Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4: 41–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, Andrew, and Sam Challis. 2022. Fluidities of personhood in the idioms of the Maloti-Drakensberg, past and present, and their use in incorporating contextual ethnographies in southern African rock art research. Time and Mind 15: 101–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, Peter W. 2014. Perspectival Ontology and Animal Non-Domestication in the Amazon Basin. In Antes de Orellana. Actas del 3er Encuentro Internacional de Arqueología Amazónica. Edited by Stéphen Rostain. Quito: Instituto Francés de Estudios Andines, pp. 221–31. [Google Scholar]

- Stoffle, Richard, Kathleen Van Vlack, Alannah Bell, and Bianca Eguino Uribe. 2024. Storied Rocks: Portals to Other Dimensions. Arts 13: 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujo-Volsky, Jeannine. 1975. El Estudio del Arte Rupestre en Venezuela. Montalbán 4: 709–840. [Google Scholar]

- Tarble, Kay. 1985. Un nuevo modelo de expansión Caribe para la época prehispánica. Antropológica 63–64: 45–81. [Google Scholar]

- Tarble, Kay. 1991. Piedras y Potencia, Pintura y Poder: Estilos Sagrados en el Orinoco Medio. Antropológica 75–76: 141–64. [Google Scholar]

- Tarble, Kay, and Franz Scaramelli. 1995. Una correlación preliminar entre alfarerías y el arte rupestre del Municipio Autónimo Cedeño. In Proceedings of the XV International Congress of Caribbean Archaeology. Edited by Ricardo E. Alegría and Miguel Rodríguez. San Juan de Puerto Rico: Centro de Estudios Avanzados de Puerto Rico y el Caribe, pp. 581–94. [Google Scholar]

- Tarble, Kay, and Franz Scaramelli. 1999. Style, Function, and Context in the Rock Art of the Middle Orinoco Area. Boletín de la Sociedad Venezolana de Espeleología 33: 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tarble de Scaramelli, Kay, and Franz Scaramelli. 2010. El arte rupestre y su contexto arqueológico en el Orinoco Medio, Venezuela. In Arqueologia Amazonica. Edited by Edithe Pereira and Vera Guapindaia. Belém: MPEG/IPHAN/SECULT, pp. 285–315. [Google Scholar]

- Tarble de Scaramelli, Kay, and Franz Scaramelli. 2017. Anchoring the landscape: Human utilization of the Cerro Gavilán 2 Rockshelter, Middle Orinoco, from the Early Holocene to the present. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas 12: 429–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarble de Scaramelli, Kay, and Franz Scaramelli. 2021. Cueva de Amalivaca: Tradición y memoria. Boletín Antropológico 39: 35–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarble de Scaramelli, Kay, Carlos A. Lasso, and Franz Scaramelli. 2021. La representación faunística en las pinturas rupestres del bajo Parguaza y su relación con la caza y pesca de subsistencia, Orinoco medio, Venezuela. In La Caza y Pesca de Subsistencia en el Norte de Suramérica, Parte 1: Colombia, Venezuela y Guyana. Edited by Carlos A. Lasso and Mónica A. Morales-Betancourt. Serie Editorial Fauna Silvestre Neotropical; Bogotá: Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt, pp. 433–61. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, Terence S. 1995. Social body and embodied subject: Bodiliness, subjectivity, and sociality among the Kayapo. Cultural Anthropology 10: 143–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Terence S. 2009. The Crisis of Late Structuralism. Perspectivism and Animism: Rethinking Culture, Nature, Spirit, and Bodiliness. Tipití 7: 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbani, Franco, and Eugenio Szczerban. 1975. Formas pseudo-cársicas en granito Rapakivi Precámbrico, Territorio Federal Amazonas. Boletín de la Sociedad Venezolana de Espeleología 6: 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, Iraida. 1981. Investigaciones arqueológicas en Parmana: Los sitios de la Gruta y Ronquín, Estado Guárico, Venezuela. Caracas: Academia Nacional de Historia. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, Silvia M. 2000. Kuwé Duwákalumi: The Arawak Sacred Routes of Migration, Trade and Resistance. Ethnohistory 47: 635–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, Silvia M. 2002. Secret Religious Cults and Political Leadership: Multiethnic Confederacies from Northwestern Amazonia. In Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia. Edited by Jonathan D. Hill and Fernando Santos-Granero. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, pp. 248–68. [Google Scholar]

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. 1996. Images of Nature and Society in Amazonian Ethnology. Annual Review of Anthropology 25: 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. 1998. Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 4: 469–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, David S. 1994. By the hunter for the gatherer: Art, social relations and subsistence change in the prehistoric Great Basin. World Archaeology 25: 356–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, David S. 2013. Archaeologists, Indians, and Evolutionary Psychology: Aspects of Rock Art Research. Time and Mind 6: 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, David S. 2023. Ethnography, shamanism, and rock art. Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino 28: 275–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Robin M. 1998. “Review of Yurupari: Studies of an Amazonian Foundation Myth, by Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA, 1996.” Australian Journal of Anthropology. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/1634135/Yurupary_by_Reichel_Dolmatoff (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Wright, Robin M. 2011. Arawakan flute cults of Lowland South America: The domestication of predation and the production of agentivity. In Burst of Breath: Indigenous Ritual Wind Instruments in Lowland South America. Edited by Jonathan Hill and Jean-Pierre Chaumeil. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, pp. 325–53. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Robin M., and Jonathan D. Hill. 1986. History, Ritual, and Myth: Nineteenth Century Millenarian Movements in the Northwest Amazon. Ethnohistory 33: 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Robin, Omar González-Ñáñez, and Carlos César Xavier Leal. 2017. Multi-centric mythscapes. In Pilgrimage and Ambiguity. Edited by A. Hobart and Thierry Zarcone. Canon Pyon: Sean Kingston, pp. 201–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zucchi, Alberta. 2002. A new model of the northern Arawakan expansion. In Comparative Arawakan Histories: Rethinking Language Family and Culture Area in Amazonia. Edited by Jonathan D. Hill and Fernando Santos-Granero. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois, pp. 199–222. [Google Scholar]

- Zucchi, Alberta, Kay Tarble, and J. Eduardo Vaz. 1984. The ceramic sequence and new TL and C-14 dates for the Agüerito site of the Middle Orinoco, Venezuela. Journal of Field Archaeology 11: 55–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Style/Period | Figure/Motif | Sites | Diagnostic Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Pre-ceramic | Lizard, bird, armadillo | BO-27-B BO-29 BO-35 | Fine lines; thin, purplish paint |

| Fish | Vertical interior lines; thin, purplish paint; light red paint, vertical placement, often aligned in series | ||

| Anthropomorphs, zoomorphs | Broad lines; light red paint | ||

| 3 Early Ceramic | Anthropomorphs, “ghost figures”, quadrupeds (especially deer), possible flute player | BO-26-B BO-27-B BO-29 BO-35 BO-126 | Large figures (some life-sized or larger) Solid white or yellow paint outlined with red paint Some action between figures |

| Fish (various identifiable species), stingray, turtle, feline, bottlenose dolphin, armadillo, tapir, capybara, snake, amphibians (realistic) 1 | Solid white paint, outlined with red paint, some interior lines Vertical, lateral, or dorsal | ||

| String of “gourds” | |||

| Round, flat “basket” designs; large, rectangular “textile/mat” designs | Red/white bichrome; interior geometric designs | ||

| Unidentified figures | Yellow paint | ||

| 4 Early Ceramic | Small, monochrome zoomorphic figures: fish, deer, tapir, birds, lizard, turtle, feline, etc. | BO-27-B BO-29 BO-35 BO-126 | Red paint predominates with variations between light red, dark red, and orange Figures tend to be small to medium size |

| Anthropomorphic figures with | |||

| headdresses and rectangular or triangular body coverings or long masks Theriomorphs combining human and non-human features: snake/bird/human; bipedal deer | |||

| Small “scenes” of human/non-human figures interacting, hunting with throwing stick or spear thrower/atl atl | |||

| Falling anthropomorphic figures | |||

| Anthropomorphic figures of various linear types | |||

| Zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures placed on horizontal lines | |||

| Cultural objects: baskets, maracas, nets or fishing traps, woven mats | |||

| Phytomorphic figures (rare) | |||

| Outlined crosses, sometimes multiple | |||

| Concentric circles and rhombuses Segmented box or square | |||

| Parallel dotted lines “Netting”, open, connected lines | |||

| 5 Late Ceramic | Paired zoomorphic figures Circle with internal lines (turtle shell?) Winged circles, circle grids, and chains, “textile” or “basket” designs Crosses and outlined crosses | BO-26-B BO-29 BO-35 | Dark red paint with thick lines Black paint Bichrome red and white paint, less symmetrical Bichrome red and black paint Polychrome red, black, and white paint |

| 6 Late Ceramic | Anthropomorphs with rectangular, solid bodies Paired figures in contrasting colors | BO-26-B BO-29 BO-35 BO-126 | Thick, white, pink, and yellow paint predominates Sloppy execution |

| Rabbit, lizard, fish “Maracas” Concentric circles with interior divisions Meandering lines Smears | |||

| Period 7 Colonial To present | “COMUNIDAD” “KH” “Kiloin” | BO-126 | Text in cream-colored paint Very recent; painted after our first visit |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tarble de Scaramelli, K.; Scaramelli, F. Predation, Propitiation and Performance: Ethnographic Analogy in the Study of Rock Paintings from the Lower Parguaza River Basin, Bolivar State, Venezuela. Arts 2025, 14, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030051

Tarble de Scaramelli K, Scaramelli F. Predation, Propitiation and Performance: Ethnographic Analogy in the Study of Rock Paintings from the Lower Parguaza River Basin, Bolivar State, Venezuela. Arts. 2025; 14(3):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030051

Chicago/Turabian StyleTarble de Scaramelli, Kay, and Franz Scaramelli. 2025. "Predation, Propitiation and Performance: Ethnographic Analogy in the Study of Rock Paintings from the Lower Parguaza River Basin, Bolivar State, Venezuela" Arts 14, no. 3: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030051

APA StyleTarble de Scaramelli, K., & Scaramelli, F. (2025). Predation, Propitiation and Performance: Ethnographic Analogy in the Study of Rock Paintings from the Lower Parguaza River Basin, Bolivar State, Venezuela. Arts, 14(3), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14030051