Abstract

This study scrutinizes the active role of mobile urban spaces in shaping and generating social space. It explores the depiction of car spaces in two Iranian films in their cinematic narratives, symbolic meanings, and influence on the perceptions of urban mobile space, often referred to as third spaces in the urban studies literature. This interdisciplinary paper investigates the socio-cultural manifestations of the car interiors in two hybrid docufiction films: Ten, directed by Abbas Kiarostami, and Taxi, by Jafar Panahi. Built on the new mobilities paradigm’s perspective on the mobile space of cars wherein social space is inevitably produced and re-produced, this paper reveals the socio-cultural dynamics of the car space in the films’ representations. The car space produces subjectivities, exhibits socio-cultural foundations, offers a sense of belonging and place-making, and provides opportunities for informal social interactions, while embodying power dynamics. The central aim is to revise our conceptualizations of mobility spaces by examining spatial practices that revolve around the car spaces. The paper integrates cinematic representation as a resource for planners and social scientists to conceptualize mobility spaces, introducing diegetic cabinography filmmaking style.

1. Introduction

The current work on urban mobility addresses mobile spaces as interconnected networks of bodies and objects, emphasizing the diverse ways individuals interact with these spaces. For instance, automobility, as one of these mobile spaces, is conceptualized as a system—an assemblage of objects, individuals, and ideas—highlighting the interaction between humans and automobiles (Urry 2004). As part of the new mobility discourse, the paper uses two films, Ten by Abbas Kiarostami and Taxi by Jafar Panahi, to pave the way for novel social interpretations of these spaces. These hybrid docufiction films were made in Tehran’s road spaces to depict the seemingly ordinary car spaces of daily use as, in fact, social, fluid, and interconnected.

In Tehran, for example, where traditional social venues such as bars are banned, automobiles serve as mobile social hubs for young adults. Young boys and girls use separate cars to navigate certain Tehran roads for hours and partake in playful interactions, or the so-called Dor-dor strategy. This car interaction often leads to traffic jams as cars stop on the roads for young groups to engage in conversations or even sometimes dance together. Far from showcasing isolated drivers on the roads, Iranian mobility reveals the social significance of mobile spaces in the context of banned activities (Bahrami 2016). Tehran’s road spaces in this paper, as depicted in the films, illustrate the broader social dynamics and fluidity of urban mobility.

Recent films on mobility spaces represent the socio-cultural shifts, pointing at societal attitudes, values, and historical contexts and influencing audience perceptions (Laderman 2002, p. 3). Often with no distinct narrative or storyline, using digital and handheld cameras, and focusing only on the car’s interior space, these films scrutinize the mobile experience in cities. They offer a “diegetic cabinography” style that focuses on the personal interactions and daily activities amalgamated with a larger view of societal issues in the car, contrasting the transformational journey often shown in traditional road movies (Adey et al. 2012; Boczkowska 2023a). By depicting mobile spaces, these films take a meticulous walk through the cultural landscape of society.

This paper points at mobility space as a fluid, in-between space imbued with social interactions. It is indeed a dwelling in motion that disrupts traditional social roles and boundaries and embodies movement, experience, and subjectivities that are politicized, marginalized, and enculturated. In Iran, this mobile space represents companionship, an empowered space for women, and a refuge and sanctuary from societal burdens for men. The films’ diegetic cabinography style effectively portrays individuals’ journeys, communications, feelings, and ways of personifying space within a broader socio-cultural space to transform them into unique sites of belonging and memory. The socio-cultural factors inherent in car space, whether used collectively or individually, as depicted in the films, provide planners and researchers with new opportunities to re-examine mobile spaces as fleeting semi-public spaces.

2. Conceptual Framework of Mobile Space

Around the 1960s, Goffman articulated the idea that cars are not completely devoid of social space (Goffman in Jensen 2010). Goffman regards pedestrians as “vehicular units”, allowing him to outline the similarities and differences between car and foot traffic (Goffman 2009). He characterizes pedestrians as “pilot[s] encased in a soft and exposing shell of skin and clothing”, in contrast to the hard shell of a car. The concept has received relatively little focus in academic discussions, with a resurgence of interest only recently, which looks at urban cars as an extension of the driver’s body (Urry 2006), a diffused social occasion (Conley 2012), and a dynamic form of material culture (Franz 2008) that reinforces or perturbs societal identities and ideologies (Lezotte 2021).

The new mobilities paradigm taps into this interest and highlights the social, cultural, spatial, and power dynamics that shape the experience and impact of car use in urban areas. Research on car spaces has revealed the intricate web of desires, feelings, emotions, social interactions, and spatial dynamics linked to the movement of drivers and passengers (Featherstone et al. 2005; Miller 2001; Urry 2007; Sheller and Urry 2000; Merriman 2009). The studies have emphasized the need for a multidimensional understanding of urban mobility that considers the diverse perspectives, interactions, and implications associated with automobility. It is particularly in Urry’s work that automobility is conceptualized as a system, an assemblage of objects, individuals, and ideas (Urry 2006).

Urry (2006) believes that the individual has dwelled in cars since its invention, first “inhabiting the road”, then “inhabiting the car”, and currently “inhabiting the intelligent car” (Urry 2006). He notes “The structure of ‘auto-space’ [auto in an automobile] forces people to orchestrate in complex and heterogeneous ways their mobilities and socialities across very significant distances” (Urry 2006, p. 19). This paper applies the mobile space of cars as such a dynamic space that casts travellers, including drivers and passengers, as hybrid or cyborg entities within an assemblage (Featherstone 2004; Merriman 2009; Sheller 2007; Sheller and Urry 2000). The physical space of vehicles and other objects of mobility are integrated in this assemblage showcasing automobiles and those within them historically entangled in processes and stories that are “racialized, gendered, sexualized, nationalized, globalized, and localized”, leading to patterns of exclusion and inclusion, as well as the shaping of stereotypes and identities (Merriman 2009, p. 592).

While this intricacy of the amalgamation of physical, socio-political, cultural, and personal, or as Urry calls it, “the new mobilities” paradigm, is scrutinized here as we delve into two films, the paradigm is not exclusively the focus of urban researchers or sociologists but is also used in recent film studies (Barker 2009; Osterweil 2014; Ross 2015). For instance, through the lens of the new mobilities paradigm, Boczkowska (2021) explores some experimental films that adopt the phenomenology of automobile usage, offering a vividly embodied experience of journeying. According to Boczkowska (2021), films fit into the new mobilities paradigm since they consistently reinterpret and transform the perception of space and place during travel. The paradigm reveals drivers’ and passengers’ diverse sensory and kinesthetic experiences, and the audience’s perspective is deeply integrated and indistinguishable from that of automobility.

To sum up, mobile space, therefore, focuses on the everyday activities of cars as an embodied practice with multi-layered social meanings. The mobile space is regarded as a place and a physical space enriched with lived experiences and social exchanges, imbued with symbolic and cultural significance. It encompasses power structures and social identities that are tied to its inherent fluidity and uncertainty. This dynamic will further assist us in our film analysis to illuminate the mobile cultural identities, malleable boundaries between public and private spheres, and spaces that are defined by gender and power narratives.

3. Mobile Space and Social Space in Films

Mobile spaces and cinema have simultaneously been part of the modernization processes, shifting the human experience of the rural and natural world to the urban and virtual spaces. The growing body of literature on automobility and films based on car and road experiences go hand in hand, and this is likely not coincidental (Archer 2016). For instance, the film history field has extensively examined the interconnected relationship between automobiles and cinema (Archer 2013; Laderman 2002; Mazierska and Rascaroli 2006; Paluzzi 2013). The body of work shows that whether from a technical, aesthetic, or thematic standpoint, mobility has crucially become part of current cinematic images.

A quick look into the history of cinema and automobility dates to the late 19th century, with silent films such as the Lumière Brothers’ Arrival of a Train in the Station (1900s) depicting a moving train creating a proto-cinematic experience (Koeck 2012; Paluzzi 2013). Around the same time, phantom rides, a film technique, emerged where cameras were mounted on vehicles, creating a sense of movement for audiences, leading to the illusion of reality and fantasy (Gunning 2010). Digital filmmaking, as a new technological advancement, diminished phantom rides’ popularity by the 1930s; it offered techniques like rear projection, engaging audiences with new perceptions of movement (Mulvey 2007). Until the 1960s, these techniques were widely used to introduce dual temporality, as they also transformed automobility depictions from within vast landscapes to confined car interiors (Stock 2021). The Great Depression of the 1930s and 1940s, with its socioeconomic turmoil, inspired the film industry to critique the situation, particularly using automobility (Stock 2021). Automobility depiction entered a dark phase, critiquing disillusionment with the American Dream and revealing social mobility realities and changes after World War II with noir films of the late 1940s and early 1950s (Stock 2021; Osteen 2008). The technological advancement of the 1950s and 1960s, the rise of youth culture, and the built structure of highways and freeway expansions led to the first wave of road movies. Road movies move beyond automobility’s technological focus, framing the car as a central symbol of mobility and personal transformation (Laderman 2002). Alongside, the American representation of automobility comes under scrutiny by European filmmakers, particularly the French New Wave, criticizing the fantasies of freedom tied to capitalism (Archer 2016) and the downfall of automobility in cities, like in Jacques Tati’s film Traffic (1971). Their depiction of automobility later shifted towards a cinema prioritizing visual and auditory sensations over narrative logic (Archer 2013). The contemporary experimental road movies follow this shift and depict sociocultural landscapes, with films now transcending cultural boundaries and mediating themes of power, autonomy, and cultural belonging (Boczkowska 2021; Eyerman and Löfgren 1995).

Since the beginning of the connection of automobility and cinema, filmmakers have depicted mobility in films, whether as a display of freedom, self-discovery, identity, spirituality, or diversity on a personal scale (Laderman 2002; Merriman 2009). On a social level, from a critical point of view, the movies using car space engage audiences with societal attitudes or, as Laderman notes, explore the conflicting dynamics of modern capitalism (Laderman 2002, pp. 50–51). These movies emphasize individual free actions, particularly in Americanized Road movies, which critically highlight the individual’s connection to social structures (Archer 2013). Due to their emphasis on pure vision and movement—or so-called the “cinema of attractions”(Archer 2016)—these films visualize the close connection between nature and culture, landscape and machines, and the individual and society within the confines of studios and later in real landscapes of cities or countryside (Archer 2017; Borden 2013c; Laderman 2002). On another level, film representations of mobile space have also influenced the audience profoundly. Borden (2012) explains the impact of road movies on the transformation of spectators into drivers, shaping how they navigate physical environments and remember cinematic portrayals while driving. Borden (2012) also believes that cars in films disprove the notion of a prevailing uniformity or homogeneity in driving. These films introduce various options for viewers and drivers to pick personalities or simply driving habits. Road movies occupy a pivotal place in the cultural history of automobility and cinema due to their sustained popularity and significant impacts on both societal and individual levels.

Moreover, urban mobile space has also been significantly intertwined with the representation of gendered spaces in films (Archer 2016; Luciano and Scarparo 2010). Feminine mobile space in films has been politicized since the beginning of filmmaking. If, for instance, in the 1960s and 70s, movies relegated female characters to passive passengers, romantic interests, or erotic distraction, later films, such as Psycho, Carnival of Souls, and The Haunting point to urbanization processes and car ownership, often submitting women to domestic duties and patriarchy (Boczkowska 2023b). Women’s mobile space in films is depicted as limited because of their lack of financial resources, transportation options, and adequate social spaces (Ceuterick 2020). This gendered spatial constraint hinders their ability to freely inhabit and move through spaces (Ceuterick 2020). In addition, in road movies, movies with female protagonists are frequently regarded as a reimagining of the male-dominated genre (Ceuterick 2020). Currently, female directors depict women’s car usage by considering factors such as identity transformation, companionship, family, and empowerment (Lezotte 2021).

While the feminine mobile space has since transformed, particularly with the release of Thelma and Louise and the rise of independent and mainstream feminist and queer road movies in the 1990s, the masculine mobile space reveals male identity crises and masculine anxiety and glorifies macho culture, according to Laderman (2002, p. 21). Recent films depict the importance of roadways as ambiguous, liminal, and transient zones, specifically in connection with masculine characters dealing with crises or denial (Archer 2016). The mobile space of roads and cars, as symbols of a second home away from home, according to Archer, illuminates the introspection and vulnerability of the male main characters. Overall, mobile environments such as cars, roads, and highways divert the audience’s views to this portrayal of gendered space, which warrants further investigation and exploration.

More than gendered space, films about mobile spaces depict geographies beyond the confined limit of urban areas, investigating the transformation that global space brings, transitions into more fluid borders, and showcase hybrid identities and crises of the national state. Studies on “post-migrant cinema” (Leal and Rossade 2008), “intercultural cinema” (Marks and Polan 2000), “cinema of the borders” (Bennett and Tyler 2007), and “transnational cinema” (Ezra and Rowden 2006) explore the thematic elements of films about exile, migration, and mobility spaces.

The representation of mobile space in films offers social, physical, and personal readings of society. It also pinpoints new experiences and engagement with the surrounding environment. Films then depict the car space as holding a fluid nature where the physical boundaries of cars do not necessarily limit social urban experiences.

4. Diegetic Cabinography: The Symbolic Meanings of Cars’ Interiors in Cinematic Narratives and Urban Discourse

American films in the road movies of the 1990s forward stayed focused on the threat of the automobile’s interior with serial or psychotic killer showcasing the interior as a nest at risk (Stock 2021). Films such as Wild at Heart, Kalifornia, and True Romance depict each car stop as a perilous encounter, underscoring the vulnerability of travelers’ lives at every stop. But, other films on cars took a different path with the emergence of digital video inthe 1990s, which led to experimenting with forms of realism. This technical influence assists in exploring themes of travel, personal connections, and the pursuit of new experiences (Rascaroli 2017), as well as emphasizing the act of being mobile in the unpredictable nature of the journey (Laderman 2002; Rascaroli 2017).

This novel way of seeing the car interior as the representation of everyday life, the sense of home and belonging, and the fluid space lying on the boundary of interior and exterior, private and public (Urry 2000), is a relatively underexplored aspect in films. Euler (2002) envisions the car space as a text that reveals the intricacies of our everyday social spaces. Like de Certeau (1984), who sees pedestrians navigating a city and acting within its spaces as pertaining to speakers or writers navigating a linguistic system, similarly, Euler (2002) views the act of moving and narrating within the car space. Boczkowska (2023a) explores the car interior, shedding light on the social dynamics of car travel as well as the haptic and kinaesthetic dimensions of driving and “passengering”, a term she borrows from Adey et al. (2012). The car interior encompasses familiar characteristics of home life, providing a space for protection, creativity, social interaction, relaxation, or contemplation (Boczkowska 2023a). In her book Inside the Car, Boczkowska explores the interior space of cars in works of filmmakers that position the camera’s gaze on the driver or passenger and the side windows. This camera gaze that focuses on passengers’ experiences, events unfolding in the car, and various objects inside and outside the mobile environment is what I call “diegetic cabinography”. The camera in the diegetic cabinography film style is solely located inside the car and only captures the people and the events of the car interior. It serves as a platform where individuals can assert their individuality but simultaneously establish connections with other drivers inside or outside the car. The outside world matters less but crucially impacts on the social space of the interior and the individual with multiple, mediated, heterogeneous, lived, and largely anonymous experiences of being in transit (Adey et al. 2012).

The diegetic cabinography emphasizes the “passengering” that is situated at the intersection of passivity and action, working hand in hand with the duration of movement and a dynamic synthesis of past and present thought and matter (Bissell 2010). Whether the former or latter, passengering, or in Pearce’s (2017) terms, “automotive consciousness”, in current filmmaking and media functions as a sensuous and embodied practice (Waitt et al. 2017). For instance, the back seat passenger experiences a spatial division between the back seat and the front of the car due to the different physical, contradictory, and confined areas of the back seat. However, the back seat offers a space of visual, aural, and physical flow due to the multiple ways the back interior permits exit into the external environment. Hence, the experience of being a backseat passenger unveils a distinct and often disregarded intricacy of travelling by car, which is typically unnoticed by the driver and the passenger in the front seat (Boczkowska 2023a, pp. 224–25).

The diegetic cabinography also reveals what Paluzzi (2013, p. 31) coins “reflexivity within the context of road movies”. Reflexivity means two things here: it reminds the audience they are watching a film, and the filmmaker takes on a central role as a protagonist. The result is “reflexive imagery”, an autobiographical depiction of a living space both for the filmmaker and the audience. It plays as a dynamic, fluid docufiction that allows filmmakers to express socio-political, personal, or cultural aspects at a deep level of engagement, creating a semi-private space for interactions between the audience and the films’ passengers and drivers. It shows, for instance, a deeper nuanced depiction of gender, spatiality, and cinematic narrative in cultural terms, which is an unexplored terrain regarding the complex dynamics involved (Boczkowska 2023b).

Iranian filmmakers like Abbass Kiarostami and Jafar Panahi, inspired by this diegetic cabinography style, belong to this group of filmmakers where the narrative lies not on the logic of the journey or landscape but on the transformative power of the car space that reveals the sociopolitical or cultural landscape to the audience. Abbass Kiarostami’s characters in his films inhabit a mobile fluid space, creating a gaze particular to Kiarostami’s filmmaking process (Dibazar 2017). “Kiarostami’s characters travel, work, talk, discuss, cry, laugh, and share in the car—in short, they dwell in it”, notes Dibazar (2017, p. 302); they live it. Kiarostami’s mobility and car space visually communicate with immobile audiences, showcasing social and cultural spatial boundaries (Dibazar 2017). The spatial characteristics of Kiarostami’s cars allow the gaze to be elicited by the drivers, passengers, and spectators (Dibazar 2017).

In a similar context, Jafar Panahi uses the car to depict the Iranian socio-cultural space of everyday life. In the film Taxi (2015), the director interacts with other passengers while on the move. Diegetic cabinography for Panahi serves as an ingenious strategy to circumvent the Iranian government’s sanctions against shooting films. As a result, the car space transforms into a space of freedom and a sanctuary of expression. It becomes a mobile place where the director navigates through the roadblocks set by the authorities, allowing for a form of resistance and storytelling within the confines of a vehicle. The car as a hidden, private, yet mobile space in urban areas facilitates political discourse and engagement, thus becoming an essential tool for the filmmaker to challenge governmental constraints. It is a workplace, a lived space markedly diverging from Western conventions. Consequently, the portrayal of cars in these films reveals previously uncharted social, spatial, cultural, and political dimensions.

5. Case Studies

Before examining the car journeys in both films, it is essential to first situate them, in brief, within the broader context of Iranian film culture. In fact, both filmmakers are part of the new wave cinema in Iran (Jahed 2022; Sheibani 2011). Iranian cinema, characterized by its non-Western artistic form, intricately weaves realist narratives with hybrid sensibilities (Sheibani 2011). Particularly in the works of filmmakers such as Kiarostami or Panahi, Sheibani (2011) believes this new wave is rooted in negotiating cultural and Iranian poetic literary aspects. Meanwhile, Majidi (2017) notes that it speaks to a new form of social drama revealing real issues, people, and events. Naficy (1995) situates this cinematic wave within a genre that interrogates moral questions, while Jahed (2022) extends the discussion beyond Iran’s socio-cultural borders, exploring the catalyst impact of Italian Neorealism and the French New Wave in shaping the Iranian New Wave. While taking different approaches to characterize the Iranian new wave cinema, scholars agree that Iranian filmmakers navigate state control with remarkable caution and ingenuity. They skillfully employ a range of creative strategies to circumvent censorship yet preserve the thematic depth, narrative intent, and stylistic integrity of their work (Jahed 2022). The socio-political messages are therefore hidden in their works, where the “unseen” holds a deep significance in their films (Sheibani 2011). Yet, to this day, there remains no comprehensive study that investigates car spaces in Iranian cinema, even though some of the most internationally acclaimed Iranian filmmakers employ the car as both a metaphor and a central element of their cinematic language. Moreover, no cumulative research has been conducted on the intersection of car and social space within the context of Iranian films. This study focuses on the works of Kiarostami and Panahi, whose films uniquely engage with the car as both a spatial setting and a site of refuge to reflect on social issues.

The film Ten by Kiarostami portrays a female driver named Mania, while Taxi by Panahi features a male driver played by the director himself; both characters navigate the streets of Tehran, providing a window into the city’s social landscape. Kiarostami has won numerous awards, including the Palm d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. His cinematic language leans towards creating semi-documentary films, here called hybrid docufictions, using distinctive camera techniques, non-professional actors, and occasionally casting himself in the movie. He moves away from traditional ideas about character, plot, themes, and narrative structure. Kiarostami exhibits a distinct proclivity for integrating automobiles into his feature films post-1990. Automobiles assume a significant role in three of his films, namely Life and Nothing More (1992), Taste of Cherry (1997), and Ten (2002). In his cinematic universe, the automobile serves as a mobile space where new characters, scenes, and events are encountered, and creates a sense of belonging.

Jafar Panahi, the director of the film Taxi and former assistant to Abbas Kiarostami, is a renowned filmmaker who has received numerous accolades at the Cannes, Venice, and Berlin film festivals, including the Prix de la Camera d’Or. After years of disputes with the Iranian government over his films’ content, which included several brief arrests, Panahi was detained in 2010 along with his family and friends. He was sentenced to six years in prison and a twenty-year restriction on any film activities and leaving the country. The sanctions led to the creation of the film Taxi, a docufiction film shot with dashcam and handheld cameras, demonstrating to the government that he was working as a taxi driver. Taxi premiered at the 65th Berlin International Film Festival and won the Golden Bear. Panahi’s approach to Taxi filmmaking is more script-based, although similar to his mentor Kiarostami’s Ten. His films are recognized for their humanistic viewpoints, often highlighting the struggles of children, the poor, and women. In Taxi, he drives a taxi to authentically depict the daily lives of Iranians amidst a complex socio-political and cultural landscape. As noted by Brody (2015), “He puts his face, his body, his voice, his own life into [t]his film as an existential act of self-assertion against his effacement by the regime.”1

6. From Mise-en-Scène to Motorways: Dissecting Car Depictions in the Two Films

The filmmaking processes in Ten and Taxi bear some fundamental differences that affect how the city is portrayed via the mobile space of their cars’ representation. Taxi and Ten have similar cinematography, share some editing features and a mise-en-scène, but they are different in how the directors participate as actors and the use of actors and non-actors. They were also produced 13 years apart. In Taxi, the director intentionally uses professional actors and non-actors to produce a docufiction style, with the plot being fully scripted. In contrast, the intent behind Ten was to record, within a loosely pre-established plot, the unpredictable movements of the car and conversations, along with whatever else came within the sight and sound of the camera (Andrew 2005). Taxi follows a scripted journey within the car space, whereas Ten’s narrative embraces spontaneity. The difference helps us better understand both artists’ portrayal of the socio-cultural and political realities of Tehran, whether intentionally scripted or not.

Kiarostami’s spontaneity applies to interiors with occasional exterior spaces, actual streets, and passers-by’s comments and gazes (Archer 2016). Kiarostami camera’s style must follow the fluid thematic intention. He spontaneously uses the camera, dialogues, and narratives to portray spontaneous everyday mobile space. At the same time, he is also absent during shooting and does the directing and editing when scenes are already shot. In this regard, the audience forgets about the camera and is fully immersed in moving and living the mobile experiences within the car space. But, in Taxi, the audiences are fully aware of the camera and, from time to time, are strongly reminded of the filmmaking processes either by the presence of the director as the driver or the dialogues that intentionally pinpoint the camera as “the reflexive imagery” (Paluzzi 2013, p. 6) of the car space. Integrating such a style allows the director to flee from the sanctions. The reflexive imagery in Taxi is intensely political, engaging viewers with the direct city life experiences of the director, albeit in a filmic space.

The line between documentary and fiction is blurred in both films, with each occupying a middle ground. Panahi frequently disrupts the narrative and employs non-actors to convey political messages, offering real city life challenges. Conversely, while Ten, with its spontaneous dialogues, could be seen as a documentary, it is often regarded as fiction due to its structured narrative (Archer 2016). Whether they portray reality or fiction, the digital video cameras are mostly located on the dashboard in both films. Kiarostami’s two cameras are consistently locked on the dashboard and only shoot the front seats, whereas Panahi subtly shifts the cameras to the backseat or into actors’ hands, creating new gazes in some shots.

6.1. The Concept of the Car Space in Taxi and Ten

Kiarostami’s cinematic techniques in Ten illustrate a pendulum-like oscillation between mobility and fixity. Subjects and objects represent both states, with the stationary camera on the dashboard and the constant slow movement of the car and protagonists. This visual development on subjects that seem to be locked in place while still mobile, as well as the outside sceneries and passers-by, forces the immobile audience’s distinctive gaze at mobility and visuality. In Dibazar’s (2017) view, the long, uninterrupted 16-min opening scene of Ten without a cut, move, zoom or change in the focus shows the director’s use of fixity to convey mobility (Dibazar 2017). Kiarostami’s camera oscillates between movement and stillness, a concept, in Beckmann’s terms, of “motility” (cited in Dibazar 2017, p. 315). Kiarostami mobilizes the viewer’s gaze in two opposing directions, being in the center of action and events as they take place and wandering beyond the frame’s center (Dibazar 2017).

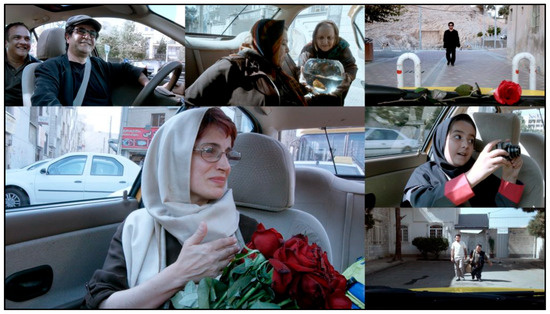

In Taxi, Panahi’s car space emerges as a form of liberating movement, where the constraints of the physical environment paradoxically enable a fluid, dynamic interplay of bodies, belongings, and perspectives. The taxi’s interior is a microcosm of contemporary Tehran urban experience due to Panahi’s objects and subjects’ oscillation between stasis and flux (Figure 1). The interior of the car, back and front, due to the primary function of the car as a taxi, is an entire mobile entity. Despite the confined space of the car, passengers and drivers are not rigidly fixed in place. This pervasive sense of mobility encompasses not just the people but the objects and ideas within the space. The camera itself shifts to the backseat, to people, and acts as the gaze that portrays the outside vehicle. Urry (2000) asserts that numerous movements and stationary conditions characterize such dynamism of mobile spaces. If the fluid nature of the car space of Kiarostami is more of a phenomenological interpretation of mobile space, Panahi’s car space is derived more from a social constructivist reading.

Figure 1.

Social microcosm of contemporary Tehran, Iran, in the film Taxi (Source: http://www.irancinepanorama.fr, accessed on 5 March 2025).

Ten’s fixed camera offers an intrapersonal level compared to Taxi’s mobile camera, which has a more interpersonal dynamic as viewers are captivated by the subtle gestures and expressions of the central subjects while drawn to the fleeting, unfocused sights in the peripheral background. Kiarostami’s medium fixed frames allow this close observation of delicate gestures, moods, and habits, cultivating a deep human bonding, or, in Bransford’s (2003) opinion, offering a subjective identification. This intrapersonal focus, for instance, is shown when the camera remains for several minutes on Mania’s sister doing nothing in the car (Figure 2). The car represents a space of the “most trivial, familiar, uneventful, and even tedious form of everyday life”, Dibazar (2017, p. 321) notes. “By being attentive to such residual spaces, times and practices, Kiarostami builds an embodied and affective unit of mobility that shifts along with the rhythms of everyday life” (p. 321), whereas Panahi shifts the camera to highlight the inherent dynamism and spontaneity of events and interactions in their mundaneness, underscoring the importance of interpersonal exchanges and culturally shared experiences. The literature also points to the diffused social occasion and the dynamic form of material culture in automobile space (Conley 2012; Franz 2008). These different directorial visions offer audiences a deeper introspective reflection in Ten and a more interactive, socially oriented perspective in Taxi.

Figure 2.

Camera capturing the everyday action for long period (Source: the film’s snapshot).

6.2. The Car Space: A Frontier of Public and Private

Either form of directorial approach emphasizes the car as a site where the private and public collide with varying degrees of complexity in the relationship between individual and collective interiority and the social experiences. In Ten, Kiarostami’s and the film crew’s absence during the scenes’ shooting, the use of two fixed cameras on the dashboard, and the shot-reverse-shot structure within the confined car space reflect an attempt to capture the in-between nature of this mobile, yet intimate, setting. The director’s limited physical presence and control during the filming process allows for the spontaneity of the connection of the outside and inside to dominate. It emphasizes the car’s interaction with the external street environment, while the portrayal of the intimate interior space is intended. It contributes to an in-between narrative of the mobile space in Iran in private cars (Dibazar 2017). On the contrary, Panahi’s mobile digital cameras, including the cellphone camera inside the car, dominate the public realm more than the private. The taxi’s interior foregrounds the public debates and negotiations among the diverse passengers in his presence as the driver.

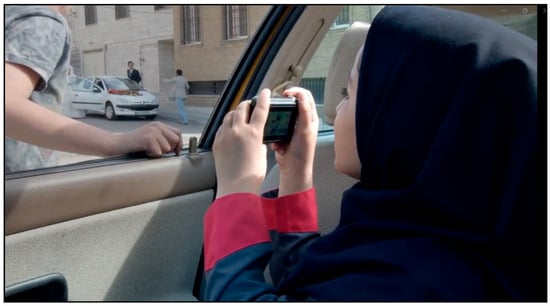

For both Kiarostami and Panahi, the in-between nature of car space allows for the manifestation of personal and social space in Iran. For instance, Panahi deliberately uses dialogue to convey that it is through this in-between space that the young film student who appeared in two scenes can find a better narrative for his film (Figure 3). The resistance space in Panahi’s work lies outside of the home and in the act of movement itself, in the constant interaction of public and private. This spatial understanding aligns closely with the mobile, fragmented, and relational conceptualizations of place and space that are central to Deleuze and Guattari’s ([1987] 2004) ideas, as well as the perspectives of new mobilities studies that focus on nuances (Adey 2010; Cresswell 2006; Dibazar 2017; Urry 2007). This mobile space in Ten and Taxi is interpreted by the directing approaches, characters’ interactions, the actual inside and outside of the car space, and the audience’s perception. With the director’s gaze, the car is a frontier between public and private spaces, a contested space, where state power is made visible and confronted—especially through the participation of both actors and non-actors in the car space.

Figure 3.

The car space as an in-between space (Source: the film’s snapshot).

6.3. The Car Space: A Socio-Political Space

Ten and Taxi provide a unique perspective on Tehran’s roads and the car as metaphors for life’s continuous journey, where the destination matters less than the experiences along the way (Laderman 2002; Rascaroli 2017). Taxi highlights the political pressures imposed by the government on various aspects of city life. Due to its in-between nature and the difficulty of regulating the space by authorities, the mobile nature of the taxi facilitates candid discussions on social matters. This space offers fleeting moments of social interaction where passengers openly converse or challenge established ideologies, rules, and regulations without drawing the attention of authorities or facing detention, which the government’s surveillance in more fixed physical locations renders impossible. The car space fundamentally serves as a public forum, for example, ten minutes after the beginning of the film, the audience is immersed in the conversation between the front passenger, a man, and the back passenger, a female. The woman is shocked by the recommendation of the front passenger that thieves be executed to restore security to the city. She challenges the idea of execution for the minor crime of robbery, pointing to the root of the problem: economic depression and misery (Figure 4). The debate highlights the deep division within Iranian society regarding the morality and legality of such social issues. In a separate scene, the director’s niece diligently reads to her uncle, the driver, the Islamic filmmaking guidelines and regulations that she must adhere to for her school film project if it is to be publicly screened. This allows the audience to witness the banned rules of filmmaking in Iran. In another shot, the director invites a real female lawyer—his legal counsel in the real world—to engage in a serious, honest discussion about prisoners as they navigate the streets within the confined space of the car. Laderman (2002) identifies automobile spaces as representations of Western films’ societal perspectives, values, and social contexts. Similarly, Panahi uses this mobile space to convey the same context in an Eastern culture, blending it with reality to emphasize how mobile space serves as a political arena.

Figure 4.

The car space as place of socio-political debates (Source: the film’s snapshot).

If the car in Taxi acts as the free agora space for various social matters, Ten offers a snapshot of a section of the social landscape of Iranians. It delves into women’s legal issues, personal relationships, and daily challenges, creating a humanistic space rather than a political one. The film is structured around ten distinct encounters Mania has, hence the film’s title. Mania’s car provides a lens through which the director explores the gendered experience of driving, revealing Mania’s and other females’ experiences as they navigate the streets. Mania’s car space transcends its function as a mere refuge; it serves as a transient space where her routine interactions occur, ranging from quick hop-on-and-off shopping to picking up friends, family, and strangers. Mania’s control over the car space symbolizes her autonomy and agency over her life (Figure 5), transforming the vehicle into an empowered social space for female protagonists (Lezotte 2021).

Figure 5.

Mania as a female driver (Source: the film’s snapshot).

Kiarostami’s car symbolizes a social place within a personal space, while Panahi’s car functions as a social place within a social space. Nevertheless, in both films, the mobile nature of the car space creates a unique environment for public discourse and social observation. The parallel seating arrangement forces occupants into proximity and conversation, allowing the camera to capture a revealing cross-section of societal beliefs, underground activities, and interpersonal dynamics. The car’s mobility enables the transient, fleeting nature of these social interactions to be documented in a way that would be more challenging in a static state. For example, in Taxi, unable to find a car, two women forcefully get into the taxi as they must travel each year at a particular time to perform the ritual practice of releasing fish into the water. The mobile camera moving to the front and back of the taxi follows the conversation between two women, the driver, and the front passenger, shedding light on cultural myths. Similarly, the car space becomes a stage for observing the black-market trade of banned media, blurring the boundary between public and private spheres.

Furthermore, the car’s social space, oscillating between private and public, is exemplified in another scene where the driver’s niece, waiting in the car, witnesses a beggar boy outside of the car attempting to pick up the money dropped on the ground by a passing man who appeared to be newly wed (Figure 6). This incident underscores the car’s function as a site to see the unnoticed or hidden realities of social inequality and unease, despite its illusion of being a contained, private environment. These random encounters through movement open windows into the Iranian social fabric, revealing the city to the viewer like a text (Euler 2002), akin to de Certeau’s walking experience: “These practices of space refer to a specific form of operations (‘ways of operating’), to ‘another spatiality’ (an ‘anthropological,’ poetic and mythic experience of space), and to an opaque and blind mobility characteristic of the bustling city. A migrational, or metaphorical, city thus slips into the clear text of the planned and readable city” (de Certeau 1984, p. 93).

Figure 6.

Three cameras capturing different social realities connected to the car space (Source: the film’s snapshot).

6.4. The Car Space: A Gendered Space

The car in both films is a symbolic and material space that disrupts and hybridizes traditional social roles and boundaries, especially for women. In both films, although to different degrees, the car enables new forms of intimacy, mobility, and representation that challenge the traditional norms of the conventional road movie genre (Archer 2016). Ten most ardently reveals this gendered texture through a humanistic and individualistic depiction. Produced almost a decade later, Taxi leaves the audience with the impression of a polarized society in which everyone, regardless of gender, is at risk because of the regulated urban life.

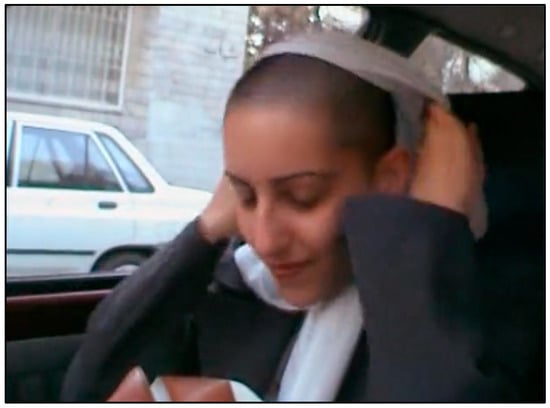

In Ten, Mania engages in reflective, embodied, and emotionally charged driving practices that disrupt the usual gratification linked to voyeurism, fetishism, and the patriarchal spectacle for the audience (Boczkowska 2023b). Mania’s driving is not defined by issues like single motherhood or domestic abuse but rather by an act of resistance against normative femininity and the establishment of a connection across shared women’s experiences. Mania’s interactions with a prostitute, a girl grieving her lost relationship, and a shy girl shaving her head and removing her scarf (Figure 7) all demonstrate how the car destabilizes conventional social boundaries and norms for female characters (Andrew 2005). Moreover, the car space also serves as a semi-domestic space, offering discussions that are otherwise hard to conduct among family members, such as Mania’s conversation with her sister or her son.

Figure 7.

The car space allows the unbreakable social rules to be broken (Source: the film’s snapshot).

The representation of gendered space in the film Taxi diverges from that in the film Ten, as it portrays a new generation of assertive, outspoken Iranian women, including lawyers, filmmakers, teachers, and others. The car space, though limited, becomes a site for critical decision-making, resistance, and unheard voices. For instance, the lawyer literally uses the dashboard camera to send a message of empowerment to women. While feminine space in Panahi’s film ties with the political space, masculinity grapples with social and economic issues, e.g., a film seller seeking economic opportunities or a young student exploring cinematic themes. Their interior space companionships and activities demonstrate how the car enables new forms of spatial inhabitation, social relations, and affective experiences.

This feminine portrayal in the car space highlights a complex gendered reality (Boczkowska 2023b), opening the debate that mobility acts beyond and above the masculine nature and is culturally performed. Unlike the Western cultural signifiers such as machinery, beauty, speed, and capitalism (Borden 2012), these films depict the car as a paradoxical site that reshapes gender, power, and cultural identities.

6.5. Driving or Passengering: A ‘Controlled’ Walking Experience in Culture

Conventional road films mostly explore the experiences of the driver and their transformational journey. Unlike these movies, with their focal point on the driver, who occupies a safe yet isolated space within the car, detached and disengaged from the outside world, the drivers in Ten and Taxi are constantly surrounded by people, activity, and objects. In Ten, Kiarostami crafts a holistic depiction of individuals encompassing the driver, passenger, camera, filmmaker, and car, resonating with street life rhythms (Dibazar 2017), provoking mundane experiences, and directing the audience’s sensory experience toward this complexity in mundanity. This evocation is echoed in Taxi, albeit with a significant distinction. Taxi takes on a political tone. Politics produce and reproduce everyday space in Taxi. This mobile politicized space shapes the daily perceptions of Iranian people. Whether with a political agenda or a humanistic approach, Ten and Taxi, however, blur the line between the drivers’ and passengers’ experiences.

In Kiarostami’s film, the driver navigates through the streets and negotiates with other drivers, a police officer, pedestrians, a shop owner, and her car passengers. Because of the director’s absence during the shooting, these interactions depict her exerting control over her environment as she maneuvers through the streets of Tehran yet simultaneously having limited influence over the daily happenings on the streets and the passengers she picks up. Dibazar (2017) notes that “allowing for the uncontrolled, in other words, is Mania’s principal form of control”. This quasi-controlled space enables viewers to connect on a personal level with the Tehran urban space. For Panahi, the uncontrolled extends to the driver’s body, the passengers, events, and the car’s physical body. The taxi becomes a place for uncontrolled daily activities, such as when the fish tank breaks (Figure 8), negotiations for the black film market take place, heated political debates about thieves’ executions occur, and an injured man records his will. The taxi serves as a space for fleeting interactions that authorities, the driver, and passengers cannot control. This quasi-controlled space is intended to represent society, suggesting that the car space is “as rich and convoluted as that of walking” (Thrift 2004, p. 45).

Figure 8.

Women and the fish tank (source: the film’s scene).

The car space, in the film Taxi, emphasizes backseat passengers by depicting their physical movements and conversations throughout the journey. A detailed view of the passenger as an active, embodied character (Adey et al. 2012) challenges the idea of a passenger being isolated, experiencing passage through the windows of their vehicle (Augé 2008, p. 105). The backseat passenger is not sealed off from physical landscapes or reduced to a detached, two-dimensional spectator. Taxi’s passengers are agentive, are subjected to ingrained behaviours and habits, and negotiate various social, technological, and economic dynamics. For example, the covert film vendor uses the taxi as a temporary workplace and, much more than a detached observer, encourages the driver to participate in his business. The passenger’s experience involves a “torsion of the active and inactive” (Adey et al. 2012, p. 172).

Adey et al. (2012, p. 178) stress this concern and define the modern passenger as a person whose “embodied movements, experiences and subjectivity are politicized, socialized, technologized and encultured in a variety of different ways”. Passengers and drivers in Ten and Taxi experience a variety of activities. Both cars become public spaces (Fox 2001): the car is an office for the film seller, a waiting room for his clients, a courtroom for orally drafting the will of an injured man, and a political place for others to contest rules and regulations openly.

7. Discussion

7.1. Navigating Third Spaces: Car Mobile Space Representations

Ten and Taxi present cars on the road as spaces of urban culture exploration, a dynamic social space (Urry 2004). The defining elements of their journeys lie in the personal embodiment and social visibility rooted in each culture, with meanings often structured around age, gender, class, and educational background. Contrary to traditional road movie narratives in which being on the road is synonymous with the ending of the protagonist’s life, as in Thelma and Louise (1991), and the unconventional spectacle of speed, sexuality, and energy is central, as in the film Crash (1996), Taxi and Ten depict the car space as a mediation of social, cultural, and political issues (Conley 2012; Lezotte 2021; Laderman 2002) that city dwellers grapple with in their daily lives in an Iranian context.

Socio-cultural debates are unarguably depicted as an essential part of the passengers’ journeys in the car space of both films. Edensor (2004) highlights how different countries’ cultures influence the driving experience by considering the contrasting experiences of moving slowly in a car with open windows through a vibrant Indian street and driving on an urban highway in a Western country where underpasses and flyovers are designed to minimize aesthetic interruptions. Iranian filmmakers depict these fleeting mobile experiences portraying Tehran’s car spaces as a semi-controlled public space, unlike other politically and socially restricted physical spaces in the city (Harvey 1973). The car space shows various voices and subjectivities (Borden 2013b; Archer 2016; Luciano and Scarparo 2010).

The films also unravel the importance of placemaking on the road. Kiarostami and Panahi underscore the importance of a shared understanding of space that constitutes place. The works of sociologists Sheller and Urry (2006) or Doreen Massey’s (2013) re-examination of the space versus place dichotomy imply that place and mobility are not conflicting ideas; instead, they reciprocally influence each other, as place-making refers to collective shared meanings through individuals’ active involvement with a place. Kiarostami’s cars actively engage viewers with this mobile human geography, expressing his belief in the car being a place comparable to any other place during the premiere of his film Like Someone in Love (2012); when questioned about his fascination with extended car sequences, Kiarostami responded, “As soon as you shoot in the car, people ask why. The car is a place like any other places” (Cannes Film Festival 2012, in (Dibazar 2017, p. 302)). A dynamic understanding of temporary place-making in transient, mobile, and momentary spaces could elevate the social value of such spaces. The temporary sense of dwelling in motion can globally reorient the car space as a locus of place-making. Doreen Massey’s (2013) conceptualization of a global sense of place offers a valuable framework for integrating with these cinematic resources to enhance the understanding of how the car can mediate people’s relationships to locality, community, and urban experience.

Films provide novel perspectives on interpreting city spaces. One example is planners’ concerns about car speeds in speed zones. Borden’s (2013a) analysis of cinematic car speeds shows that driving in urban space at a moderate pace offers social mobility. Mania’s constant speed in Ten connects viewers to a soft transition in time and space as Mania navigates roads to feel alive after her divorce. When driving at high speeds, Mania’s actions indicate an intricate engagement, choosing highways despite the higher risk of speed to spend more time with her son. The space on the highway offers her a sense of agency and an attachment to home, home being where she can talk with her son. The highway becomes a space where she temporarily exerts her rights and finds the power to bond with her only child, contesting the highway as a transitory space to be quickly passed (Bissell 2010).

The car is also seen as an informal public social setting with significant potential to influence individuals’ behavior. In Ten and Taxi, people break from their usual routines and disregard norms in an inclusive space that provides a sense of social ease. Vehicles, functioning as spaces that allow for flexibility in behaviour and usage, enable adaptability. The urban design literature could draw our attention to the adequate spaces, activities, and circumstances that promote informal social interactions and can serve as a basis for connecting mobile spaces and informal public social settings (Simões Aelbrecht 2016; Gehl 1971; Shaftoe 2012; Whyte 1980).

7.2. Interdisciplinary Collaboration in Exploring the Nexus of Cars, Films, and Mobility

From the urban planning perspective, we need to consider movement as the practice and performance that expresses an emotion, an idea, and a response to the environment, as a way of sensing, feeling, and interacting with the world. Studying movement as such assists in understanding personal, social, and cultural phenomena or simply society, as described by Urry. Perspectives such as the shared mobility of carpooling and ride-sharing services that transform cars into social spaces facilitate interactions between individuals who might not otherwise meet. If appropriately designed and carefully crafted, these mobile spaces contribute to a comprehensive social environment and, therefore, become arenas for expression, offering a new perspective on the patterning of the social process (Harvey 1973). The question remains of how effectively planners can influence and control these transitory spaces to preserve democratic principles or imbue them with potent symbolism. This could pave the way for innovative methods of engaging the population on the move to participate in legal and societal matters, a form of being a “citizen on the road”.

From a cinematic perspective, the connection between cinema and urban studies could lead to new ways of understanding mobile spaces and conceptualizing the space of mobilities. The level of identification with the portrayal of mundane practices and strategies that individuals employ to navigate and appropriate spaces is similar to the tactics and spatial practices elucidated by de Certeau. In our case study, spatial practices, such as adjusting seating positions, interacting with what is outside of the car, or modifying the interior environment, are bodily performed or they are socially manifested once the individuals organize their thoughts around a subject, stabilize their personal sphere, or create a sense of comfort or personalization within the social space of the car. De Certeau’s analogy of walking as a writing practice is applicable in the car space, as these activities create a site for personal and collective storytelling. In this way, films are a valuable tool that provides a fluid lens for researchers and planners to understand the complex interplay of individuals, spaces, and societal structures.

8. Conclusions

This paper underscores the active role of mobility spaces in the formation and generation of social space. It examines the selected films within the conceptual framework established by Urry’s (2004) theory of automobility as a system of assemblage. The films reintroduce the car social space through a dynamic configuration of subjectivities, material objects, and informational flows. This assemblage of people, objects, and information is meticulously shown through the filmic diegetic cabinography style that enables a nuanced reading of the micro-dynamics shaping the everyday mobile social spaces experienced by Iranian individuals in transit. Consequently, this assemblage in creating Iranian mobile social dynamics operates on three distinct levels.

The primary aspect is that the Iranian car space with social interactions among strangers transforms the car into a transient site of interpersonal exchange and social negotiation. These interactions, while seemingly ordinary, demonstrate a tangible and emotional aspect of mobility that adapts to the rhythms of daily life (Dibazar 2017). The Iranian car space represents a diffused social occasion, as noted by Conley, characterized by unfocused gatherings and interactions. These gatherings and interactions illuminate the realm of individual feelings, desires, and emotions, as also identified by Laderman in the context of Western films. Yet, the same basic configuration (car + human + road) produces culturally specific subject positions. In Iranian contexts, the car assemblage enables youth subjectivity through the Dor-dor practice, creating spaces for identity expression and forbidden social practices within restrictive social environments. Gendered subjectivities emerge distinctly within this assemblage, framing cars as spaces of empowerment, identity transformation, and familial connection, as Lezotte also finds in female-directed films. Similar to Archer’s analysis, the car creates personal, mobile perspectives that subvert traditional cinematic conventions. The emotional dimension of subjectivity is captured in Mania’s car in Ten, where her car becomes a space of emotional healing and communication for various women and a site of what Dibazar terms “spatial hybridisation”, blending personal, familial, and public experiences (p. 304). This multiplicity of subjectivities is what Urry tries to conceptualize in the new mobility paradigm, offering car space as a hybrid, lived space straddling public/private and interior/exterior boundaries and creating an environment where people deviate from societal norms and spontaneously interact, as we observed in Taxi’s conversations. The assemblage transforms both driver and passenger subjectivities, offering the car as a site of political, personal, and gender expression, as also shown in Paluzzi’s findings. This fosters Iranian social imageability that is an emotional and social connection to mobile spaces that transcends their transitory nature.

Furthermore, the assemblage also includes the objects of mobility space, revealing the micro dynamics of everyday social spaces. The car itself is an extension of drivers’ bodies, either in Mania’s case as a woman or in Panahi’s case as a taxi driver, creating a hybrid or cyborg entities within assemblages, as described by Featherstone, where cars no longer function as a merely visible tool or technology, but rather constitute an immersive environment for inhabiting. These Iranian cars are framed as the material culture, noted by Franz, that shapes everyday experiences and ideologies. The vehicle becomes more than a tool—it transforms into a prosthetic enhancement of the driver’s physical and social being, as in Goffman’s metaphor of “drivers as pilots encased in a hard shell”. It illuminates how the car creates a protective exoskeleton that mediates Iranian social interactions while extending the driver’s bodily presence and capabilities. Not only in the drivers’ case, this human-machine integration manifests through “passengering” or “automotive consciousness”—a sensory, embodied travel experience that emphasizes spatial and physical aspects of the car–human relationship in Iran. The car thus emerges as an assemblage that not only extends the passenger and driver’s physical capabilities and sensory perception but also becomes integrated into their identity formation, social expression, and embodied experience of Iranian everyday space, creating what Boczkowska describes as an integration of perspective “through sensory and kinesthetic means”, where the boundaries between travelers and vehicle blur into a unified socio-technical entity.

Lastly, more than people or objects, the mobility space functions as a complex informational entity that both reflects and reconfigures power dynamics in Iran, where it is shaped by race, gender, sexuality, and other identity factors (Merriman 2009). This assemblage manifests distinctly in Iranian contexts, where Panahi demonstrates how the car serves as a space of resistance, political discourse, and cinematic creativity under state restrictions, enabling forbidden social practices that challenge dominant power structures. The Dor-dor practice exemplifies how the car–human–technology assemblage creates possibilities for subverting gender segregation norms. The films exemplify Urry’s conceptualization of the car interior as a space that possesses the power to redefine traditional spatial categories. This power dynamic illuminates gendered limitations in female mobility as Luciano and Scarparo (2010) also show how the car assemblage simultaneously reinforces and challenges patriarchal power relations while creating an inclusive, flexible environment where Iranian women can deviate from societal norms and exercise agency through mobility choices.

The diegetic cabinography in both films enables the depiction of the assemblage of human+car+information, showcasing the micro-social dynamics embedded within Iranian everyday mobility spaces, dynamics that would otherwise remain obscured or inaccessible in traditional urban studies. The concept of diegetic cabinography—a film style focused on the car interior and its narrative, emotional, and social dimensions—could expand to provide researchers with a powerful analytical tool for understanding how mobile spaces function as sites of meaning-making across different cultural contexts. This filmic approach challenges researchers to reconsider automobility not merely as transportation infrastructure but as complex socio-cultural environments worthy of nuanced analysis.

Furthermore, this research demonstrates how cinematic representations can serve as valuable resources for urban theory and planning practice. Our work illuminates the rich tapestry of human connections that emerge within automobility spaces—from intimate conversations and emotional exchanges to political resistance and cultural expression. By examining how filmmakers capture these social dynamics through specific spatial arrangements and filming techniques, this research identifies the conditions that enable cars to function as vibrant social settings, despite their transient nature. These insights offer urban planners and social scientists practical guidance for designing mobility environments that accommodate and enhance social interaction, particularly in contexts where public social space is heavily regulated or restricted.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 | Brody, Richard (13 October 2015): https://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/jafar-panahis-remarkable-taxi. Accessed on 10 December 2024. |

References

- Adey, Peter. 2010. Mobility. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adey, Peter, David Bissell, Derek McCormack, and Peter Merriman. 2012. Profiling the Passenger: Mobilities, Identities, Embodiments. Cultural Geographies 19: 169–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, Geoff. 2005. 10. London: BFI Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, Neil. 2013. The French Road Movie: Space, Mobility, Identity. New York: Berghahn Books. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, Neil. 2016. The Road Movie: In Search of Meaning. New York: Wallflower Press. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, Neil. 2017. Genre on the Road: The Road Movie as Automobilities Research. Mobilities 12: 509–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augé, Marc. 2008. Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity. London: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrami, Farzaneh. 2016. Avoiding the City, Claiming Public Space: The Case of Tehran. Fabrikzeitung: Iran on the Road—In Between Public and Private Spaces. Available online: https://infoscience.epfl.ch/handle/20.500.14299/135518 (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Barker, Jennifer. 2009. The Tactile Eye: Touch and the Cinematic Experience. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Bruce, and Imogen Tyler. 2007. Screening Unlivable Lives: The Cinema of Borders. In Transnational Feminism in Film and Media. Edited by Katarzyna Marciniak, Anikó Imre and Aine O’Healy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bissell, David. 2010. Passenger Mobilities: Affective Atmospheres and the Sociality of Public Transport. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28: 270–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boczkowska, Katarzyna. 2021. From Car Frenzy to Car Troubles: Automobilities, Highway Driving, and the Road Movie in Experimental Film. Mobilities 16: 524–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boczkowska, Katarzyna. 2023a. Inside Cars: Changing Automobilities and Backseat Passengering in Experimental Film and 360 Video. Mobilities 18: 218–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boczkowska, Katarzyna. 2023b. Do Gender, Genre, and the Gaze Still Matter? Toward a Feminine Road Movie in Women’s Experimental Film. Feminist Media Studies 23: 1962–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, Iain. 2012. Drive. London: Reaktion. [Google Scholar]

- Borden, Iain. 2013a. Introduction. In Drive: Journeys Through Film, Cities, and Landscapes. London: Reaktion Books, pp. 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Borden, Iain. 2013b. Motopia. In Drive: Journeys Through Film, Cities, and Landscapes. London: Reaktion Books, pp. 119–66. [Google Scholar]

- Borden, Iain. 2013c. Conclusion. In Drive: Journeys Through Film, Cities, and Landscapes. London: Reaktion Books, pp. 227–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bransford, Scott. 2003. Days in the Country: Representations of Rural Space and Place in Abbas Kiarostami’s Life and Nothing More, Through the Olive Trees, and The Wind Will Carry Us. Senses of Cinema, December. Available online: http://sensesofcinema.com/2003/abbaskiarostami/kiarostami_rural_space_and_place/ (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Brody, Richard. 2015. Jafar Panahi’s Remarkable “Taxi.” The New Yorker. October. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/jafar-panahis-remarkable-taxi (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Ceuterick, Maud. 2020. Affirmative Aesthetics and Wilful Women: Gender, Space and Mobility in Contemporary Cinema. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Conley, Jim. 2012. A Sociology of Traffic: Driving, Cycling, Walking. In Technologies of Mobility in the Americas. Edited by Phillip Vannini. Oxford and Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 219–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, Tim. 2006. On the Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- de Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 2004. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. New York: Continuum. First published 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Dibazar, Pegah. 2017. Wandering Cars and Extended Presence: Abbas Kiarostami’s Embodied Cinema of Everyday Mobility. New Review of Film and Television Studies 15: 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, Tim. 2004. Automobility and National Identity: Representation, Geography and Driving Practice. Theory, Culture & Society 21: 101–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euler, Zachary. 2002. Car Culture: Road Maps of Space, Motion and Narrativity in Twentieth-Century Culture. Master’s thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Eyerman, Ron, and Orvar Löfgren. 1995. Romancing the Road: Road Movies and Images of Mobility. Theory, Culture & Society 12: 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezra, Elizabeth, and Terry Rowden. 2006. General Introduction: What Is Transnational Cinema? In Transnational Cinema: The Film Reader. London: Routledge, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone, Mike. 2004. Automobilities: An Introduction. Theory, Culture & Society 21: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherstone, Mike, John Urry, and Nigel Thrift, eds. 2005. Automobilities. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, Judith H. 2001. Surrounding Interiors. In Inside Cars. Edited by J. Abbott Miller. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, pp. 6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Franz, Kathleen. 2008. Automobiles and Automobility. In Material Culture in America: Understanding Everyday Life. Edited by Helen Sheumaker and Shirley Wajda. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, pp. 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, Jan. 1971. Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space. Copenhagen: The Danish Architectural Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 2009. Relations in Public: Microstudies of the Public Order. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Gunning, Tom. 2010. Landscape and the Fantasy of Moving Pictures: Early Cinema’s Phantom Rides. In Cinema and Landscape: Film, Nation and Cultural Geography. Edited by Graeme Harper and Jonathan Rayner. Bristol: Intellect Books, pp. 31–70. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, David. 1973. Social Justice and the City. London: Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Jahed, Parviz. 2022. The New Wave Cinema in Iran: A Critical Study. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Ole Bjarlin. 2010. Erving Goffman and Everyday Life Mobility. In The Contemporary Goffman. London: Routledge, pp. 347–65. [Google Scholar]

- Koeck, Richard. 2012. Cine-Scapes: Cinematic Spaces in Architecture and Cities. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laderman, David. 2002. Driving Visions: Exploring the Road Movie. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leal, Joana, and Klaus-Dieter Rossade. 2008. Introduction: Cinema and Migration since Unification. GFL Journal 1: 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lezotte, Christine. 2021. What Would Miss Daisy Drive? The Road Trip Film, the Automobile, and the Woman Behind the Wheel. The Journal of Popular Culture 54: 987–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano, Bernadette, and Susanna Scarparo. 2010. Gendering Mobility and Migration in Contemporary Italian Cinema. The Italianist 30: 165–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidi, Habib. 2017. Contemporary social drama. In Directory of World Cinema: Iran 2. Edited by Parviz Jahed. Bristol and Chicago: Intellect Books, pp. 132–75. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, Laura U., and Dana Polan. 2000. Introduction. In The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses. Edited by Laura U. Marks and Dana Polan. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, Doreen. 2013. Space, Place, and Gender. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Mazierska, Ewa, and Laura Rascaroli. 2006. Introduction. In Crossing New Europe: Postmodern Travel and the European Road Movie. Edited by Ewa Mazierska and Laura Rascaroli. New York: Wallflower Press, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Merriman, Peter. 2009. Automobility and the Geographies of the Car. Geography Compass 3: 586–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Daniel. 2001. Driven Societies. In Car Cultures. Edited by Daniel Miller. Oxford: Berg, pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey, Laura. 2007. A Clumsy Sublime. Film Quarterly 60: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naficy, Hamid. 1995. Iranian cinema under the Islamic Republic. American Anthropologist 97: 548–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osteen, Mark. 2008. Noir’s Cars: Automobility and Amoral Space in American Film Noir. Journal of Popular Film and Television 35: 183–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterweil, Ara. 2014. Flesh Cinema: The Corporeal Turn in American Avant-Garde Film. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paluzzi, Nicholas. 2013. A Journey through Wanderweg: The Cinematic Space of Deleuze and Guattari in the Reflexive Road Movie. Ph.D. dissertation, Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, Lynne. 2017. Driving-as-Event: Re-thinking the Car Journey. Mobilities 12: 585–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rascaroli, Laura. 2017. How the Essay Film Thinks. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Miriam. 2015. 3D Cinema: Optical Illusions and Tactile Experiences. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Shaftoe, Henry. 2012. Convivial Urban Spaces: Creating Effective Public Places. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sheibani, Khatereh. 2011. The Poetics of Iranian Cinema: Aesthetics, Modernity and Film after the Revolution. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sheller, Mimi. 2007. Bodies, Cybercars and The Mundane Incorporation of Automated Mobilities. Social & Cultural Geography 8: 175–97. [Google Scholar]

- Sheller, Mimi, and John Urry. 2000. The City and the Car. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 24: 737–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheller, Mimi, and John Urry. 2006. The New Mobilities Paradigm. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 38: 207–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões Aelbrecht, Patricia. 2016. ‘Fourth Places’: The Contemporary Public Settings for Informal Social Interaction among Strangers. Journal of Urban Design 21: 124–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, Matthew James. 2021. Always Crashing: Automobility and the Cinema. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Thrift, Nigel. 2004. Driving in the City. Theory, Culture & Society 21: 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, John. 2000. Automobility, Car Culture and Weightless Travel: A Discussion Paper. Lancaster University. Available online: https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fass/resources/sociology-online-papers/papers/urry-automobility.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2024).

- Urry, John. 2004. The ‘System’ of Automobility. Theory, Culture & Society 21: 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, John. 2006. Inhabiting the Car. The Sociological Review 54: 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, John. 2007. Mobilities. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waitt, Gordon, Theresa Harada, and Michelle Duffy. 2017. ‘Let’s Have Some Music’: Sound, Gender and Car Mobility. Mobilities 12: 324–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, William Hollingsworth. 1980. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. New York: Project for Public Spaces. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).