Abstract

Tall buildings are a unique category of architectural objects, as they are characterized by a strong self-presentation effect and have a significant visual impact on the urban composition and the surrounding cityscape. This contextual impact has a one-way character—it is directed from the tall building to its surroundings, the neighborhood, the entire urban area, and the landscape. The context of the surroundings generally has no effect on tall buildings. Tall buildings are usually solitary structures, focused on their own composition. Conversely, the impact of a tall building is multifaceted: it is symbolic, iconic, and compositional, in the sense that it is a ‘strong’ form that draws attention to itself. This study analyzes and evaluates the case of the Hanza Tower, a tall building in Szczecin, and its impact on the city of Szczecin in terms of urban, architectural, and historical contexts, as well as its location in relation to its surroundings. In this case, the authors have considered the spatial and cityscape impact of skyscrapers when viewed from a distance, as well as the role a skyscraper plays in terms of its symbolic, contextual, and compositional significance within the city. Attention is drawn to the sustainable correlation of the placement of the tall building with the spatial composition of the city layout to make its overall structure legible.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Architectural objects constitute part of the urban environment, which in the contemporary world is the subject of urban planning, dealing with the design of building groups, settlements, neighborhoods, and, in particular, public spaces. According to Almusaed and Almssad, “urban design can be understood as a term describing the visible and creative aspects of urban planning. In a broader sense, the concept of urban planning encompasses the totality of planning and construction measures (…), aimed at creating the prerequisites for the coexistence of people in an environment appropriate to them in the pursuit of sociopolitical goals” (Almusaed and Almssad 2019). Tall buildings constitute a challenge for urban planning because they transmit symbolic meaning, highlight the importance of the sustainable relationship between the architectural form and its environment, and influence the city skyline and cityscape. Ali and Al-Kodmany put it poetically, stating that “the tall building is the most dominant symbol of a city and a human-made marvel that defies gravity by reaching to the clouds. It embodies unrelenting human aspirations to build even higher” (Ali and Al-Kodmany 2012).

A discussion about the positive and negative features of high-rise buildings is currently ongoing in many cities. Ali and Al-Kodmany explained that “as cities continue to expand horizontally, to safeguard against their reaching an eventual breaking point, the tall building as a building type provides a possible solution by way of conquering vertical space through agglomeration and densification. There are more and more attempts to disregard tall buildings as mere pieces of art and architecture by emphasizing their truly speculative, technological, sustainable, and evolving nature” (Ali and Al-Kodmany 2012). The subject of the presented article is the contextual consideration of the sustainable integration of tall buildings into 21st-century cities in the most appropriate and acceptable way.

The contextual visual impact of tall buildings is unidirectional, directed from the high-rise object towards its surroundings. High-rise objects are generally not impacted by their surroundings. The impact has a multi-faceted character: symbolic, iconic, and compositional—every tall building is a ‘strong form’ that draws attention to itself (Gyurkovich 1999). The high-rise buildings in the metropolitan cities are undergoing the process of “verticalisation” (Oleński 2014).

To be accepted by the local community, the placement of high-rise buildings in relation to the surrounding environment, the urban layout of streets and buildings, as well as their relationship to more distant built structures, is crucial.

1.2. The Value of the Urban Landscape

The geometry and scale of objects in urban spaces are important in shaping users’ perception of that space. The psychological dimension of tall buildings is highlighted by Wejchert (Wejchert [1984] 2008). Psychological studies indicate emotional reactions when observing geometric figures. For example, vertical lines appear to be longer than their corresponding horizontal lines, creating a shortening effect of the space in the horizontal dimension, particularly in relation to tall buildings. Gilinsky’s research allowed the formulation of the concepts of subjective and objective distance and the pattern of their interdependence (Gilinsky 1951). The spatial impact of high-rise objects when viewed from a distance is therefore important. High-rise buildings cause visual changes to the scale of the city, enriching the urban landscape, which comprises greenery and built-up components, while embellishing city panoramas with new cityscape elements.

The value of a landscape lies in its ability to evoke positive feelings in the observer. Positive feelings are aroused in us when we see a natural landscape, created by nature, or harmoniously transformed by humanity, with an aesthetic composition determined by the proportion of shapes, chiaroscuro, and colors, as well as the contrast of the natural landscape against the colors of the sky and the shape of clouds, the relationship between planes and vertical elements, organic shapes, and the rhythmic repetitions of landscape elements (Stamps 2002). The value of a landscape is immeasurable and is felt in a particular way, evoking a feeling of peace, solemnity, or pleasure as a result of its observation or contemplation. The urban landscape, also known as a cityscape, is the silhouette of the city against its foreground, composed of natural elements—trees, areas of low-lying greenery, and water bodies—and man-made elements—structures and building complexes, roads, and technical infrastructure. The cityscape is a complex landscape, the value of which lies in the carefully composed and aesthetically balanced multilateral relationship between the various built elements and the elements of the natural landscape—that is, the topography and urban phytosphere (Stamps 1994).

Shaping the urban landscape in order to create a valued landscape view involves, among other things, the appropriate arrangement of tall and high-rise buildings in relation to low-rise buildings in the urban area and ensuring the prominence of valuable historic buildings under conservation protection (Moshaver et al. 2015; Karimimoshaver et al. 2021). The visibility of historic buildings is ensured when the view of these structures is not obstructed by thoughtless development in the foreground of monuments or by major urban complexes, and when the foreground development does not compromise the dominance of the main building complex or the dominant element or elements of the landscape view. An assessment of landscape value can be carried out from various specific vantage points, created to appreciate views of the city.

It is also possible to view the urban landscape in a dynamic way, such as when driving on an expressway or by a train tour through the city, thereby observing the variability and multiplicity of landscape views. Ensuring the harmonious and valuable character of the urban landscape (or cityscape) is possible by means of the appropriate urban arrangement of the city: a clear composition of the street and road system; an appropriate shape, scale, and arrangement of public spaces, especially with reference to the placement of height accents; as well as the existence of characteristic buildings and facilities in the urban area at the city’s nodal points. The main factor in relation to the positive impact of urban landscape space within an urban area is the appropriate arrangement of attractive, rich urban greenery and the concentration of public spaces within it.

1.3. The Subject of the Research

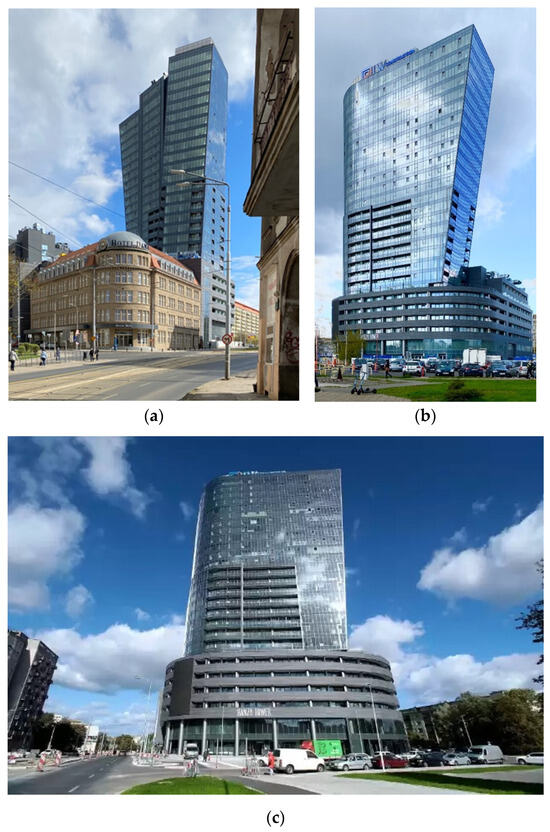

This article presents research on the influence of a tall building on its sustainable surroundings in the context of its symbolic, iconic, and compositional meaning. The example of the Hanza Tower, a high-rise building recently constructed in Szczecin (Poland), was analyzed, and assessed in terms of its spatial and symbolic impact on the cityscape of Szczecin. The height of the Hanza Tower (115 m) is not comparable to that of most skyscrapers being built in European cities or other locations around the world. It has been adjusted to match the scale and topography of the city of Szczecin, incorporating its collection of different forms of local contexts and rich urban history (Figure 1).

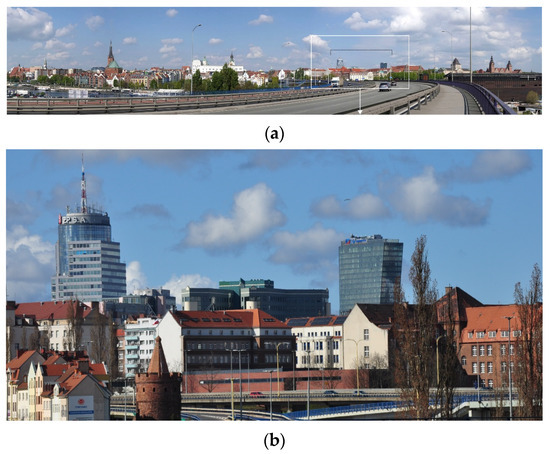

Figure 1.

(a,b) Panoramic, dynamic view from the motorway, entering the city of Szczecin, driving towards the two iconic high-rise buildings. In the enlarged photo, left: Pazim Building; right: Hanza Tower Building. Photos taken by authors.

This research aims to answer the following questions: How should one draw on the history of a place to create a high-rise building that fits into the historic urban landscape in a sustainable way? How should the urban composition of the city be linked to the planned location of a high-rise building? What factors should be taken into account when shaping the geometric form of a building? How should one take advantage of local conditions and history?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The State of Research

The influence of tall and high-rise buildings has been the subject of many theoretical considerations and specific analyses carried out by urban research centers, due to the significant impact of such buildings on the character and landscape of cities (Moor and Erysheva 2018; Akristiniy and Boriskina 2018; Zhao et al. 2020). For several years now, research has been undertaken on the impact of tall and high-rise buildings on the city landscape (Putra and Yang 2005; Rød and van der Meer 2009; Nijhuis and van der Hoeven 2018; Zachariadou 2020; Li et al. 2022).

Significant publications in this area include research work carried out at the Faculty of Architecture of the West Pomeranian University of Technology in Szczecin (Czyńska 2018a, 2018b, 2020, 2021). In this research, attention has been drawn to the necessity of following local rules for siting tall and high-rise buildings in cities (Czyńska et al. 2022) and has pointed to increasingly precise simulations and tests that allow for the most favorable locations to be selected in relation to the urban composition and their immediate surroundings (Figure 2).

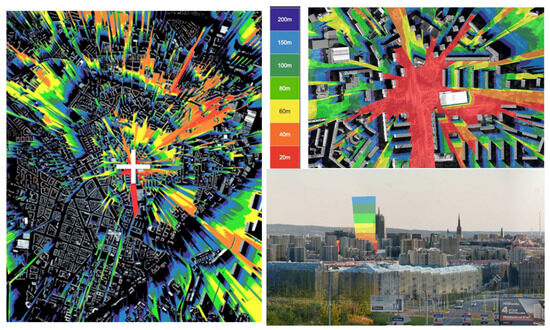

Figure 2.

Drawings presenting the range of visibility of the Hanza Tower structure in Szczecin during the preliminary studies on the height of the planned building. The study shows an analysis of the dependence between the height of the high-rise building and its visibility from different observation points. The presented drawings are generated by the Visual Impact Size (VIS) method. A study was conducted by Czyńska (2018b).

Over the last two decades, the increase in high-rise development worldwide has been clearly visible. Globally, over 50% of such investments have been built in the 21st century (in the last 15 years). Although tall buildings have grown increasingly popular in Europe (Czyńska 2018a), they may also pose a significant threat, especially to historically developed cities that contain precious urban compositions and architectural monuments and relics (Nijhuis and van der Hoeven 2018). In the discourse surrounding the negative and positive influences of high-rise buildings, several arguments have been raised (Ali 2010; Ali and Al-Kodmany 2012).

The protection of valuable urban landscapes should consist of anticipating the negative effects of the location of tall buildings before they are built and modifying investment plans accordingly. One of the methods used to assess the impact of a skyscraper on the landscape is the Visual Impact Size (VIS) method. It is an objective assessment of the extent and the visual impact of a proposed building. It evaluates all locations within a city from which the structure can be observed, based on its height (Czyńska 2018b). At its core, the algorithm is based on a geometric analysis of a 3D digital city model. This computational process generates a visibility map with a high degree of precision, of approximately 10 cm. An example of the application of the method to the Hanza Tower in Szczecin is shown in Figure 2. The method allows for a comprehensive determination of the visibility in the entire urban space, especially in all undeveloped areas. These areas include spaces between buildings, such as streets, squares, and internal green spaces within city blocks. Moreover, the simulation can include additional elements of the 3D model, such as roofs or visibility from specific features such as rivers. The results are geometrically accurate, with potential inaccuracies due solely to the quality and accuracy of the 3D city model. Importantly, all simulations are performed with the observer’s eye level at 1.7 m above the ground. VIS output can be presented in a variety of formats, including 2D maps, 3D surfaces, and tabular reports detailing visibility analysis, and tabular reports detailing visibility analysis for public spaces in the city (Czyńska 2020). Among these, 2D color maps are the most practical and intuitive for planning purposes. Each color on the map corresponds to the visibility of the analyzed building from a specific height threshold. To ensure clarity, a simplified color palette is typically used to represent, for example, eight height intervals of the proposed building. A gradient from vibrant red to deep blue intuitively conveys the intensity of the building’s visual impact, with red areas indicating maximum visibility and blue areas indicating minimum visibility.

Such VIS maps are useful for identifying sites that merit further analysis. The color coding illustrates the building’s impact on the cityscape, with red areas where the building is almost fully visible and blue areas where only the top of the building is visible. In planning practice, these often serve as the initial reference point for field studies, guiding the documentation of key vantage points selected for in-depth analysis.

2.2. High-Rise Buildings from a Citizen’s Perspective

Opinions related to high-rise buildings are divided. Wood concludes that “tall buildings are perhaps the most keenly debated building typology currently in existence. Opinions on their contribution to the urban agenda is usually clearly divided; strongly for, or strongly against” (Wood 2004). Some people feel that high-rise buildings introduce a different way of life. Recent research also confirms the mental health risks for apartment dwellers in tall buildings (Larcombe et al. 2019). On the other hand, there is a large demand for apartments in high-rise buildings with distant views, located in the core urban districts of the city. The question is whether the benefits of tall buildings outweigh their disadvantages.

Below are some areas of concern regarding tall buildings:

Negative—Arguments against tall buildings:

- Economic considerations;

- Environmental impact;

- Civic infrastructure;

- Socio-cultural factors;

- Perception;

- Public safety;

- Historic context and placemaking;

- Digital revolution;

- Mental health risks;

- Lack of access for those with mobility problems.

Positive—Arguments for tall buildings:

- Population and migration trends;

- Global competition and globalization;

- Urban regeneration;

- Agglomeration;

- Land prices;

- Land preservation;

- Climate change and energy conservation;

- Infrastructure and transportation;

- Human aspirations and ego;

- Emerging technologies.

According to Jasim, “the placement of high-rise dominants within the structure of large cities has become a hallmark of modern urban transformation as a way of counteracting active urbanization. High-rise dominants can greatly benefit a city, where they can enhance its value and express its development and the strength of its economy, as well as provide functions that distinguish it locally and globally; if they are well planned and designed, they can create an image of a dynamic, prosperous, sustainable city, attractive for life and work” (Jasim 2020).

Pietrzak has presented a comprehensive analysis of high-rise construction in European cities, concluding that “by 2013, skyscrapers had been constructed in over 100 European cities, located in 30 different countries, and the trend towards the expansion of high-rise construction continues. (…) Today, most European skyscrapers are office buildings, although in the 21st century there has been an increasingly significant tendency to equalize the quantity of residential and office buildings. Moreover, the highest European skyscrapers are designed as mixed-use buildings” (Pietrzak 2014). However, although most high-rise buildings have been built in the biggest European cities, such as Paris, London, and Frankfurt/Main, more cities are following suit, such as Warsaw (Poland) and Brussels (Belgium), along with coastal cities, such as Benidorm (Spain) and Gdynia (Poland).

The idea of constructing high-rise buildings in European cities has generally received a rather cool reception. It could be said that the 21st century has been the era in which high-rise buildings have become more popular and accepted. During the first few years of the 21st century, scientific opinion about these types of developments, especially their location in city centers and their visual impact on panoramic views in the context of historic buildings, has been strongly negative. Over the years, this assessment has softened, and the priorities of conserving city landscapes have been outweighed by priorities of an economic, developmental, and iconic nature. On the other hand, the locations and heights of new skyscrapers are given more careful consideration and are becoming better adapted to the local context. In many cases, however, it has not been urban analysis but political and economic pressures that have determined whether to consent to the locations of skyscrapers. The economy remains an important factor in their development (Table 1).

Table 1.

The author’s analytical study of the most common opinions related to high-rise buildings in European cities.

The opinions related to high-rise construction in Europe included in Table 2 are the result of the author’s observations within the analytical studies of high-rise buildings. The authors have participated in various debates and discussions in the development of local master plans, the development of international projects on the scientific analysis of high-rise construction (Czyńska 2018a), and the review of architectural projects in competitions and discussions in the forums of international conferences. They also analyzed the voice of public opinion expressed in local and national press publications and other social and public media.

Table 2.

The number of skyscrapers over 100 m in cities in Poland. Author’s own study based on statistical data from Eurostat.

2.3. Skyscrapers in City Structures

In connection with the construction of high-rise buildings around the world, regular statistical surveys are carried out (www.emporis.com, accessed on 29 October 2024). The buildings covered by this re-search are 100 m high or more. While in American and Asian cities, high-rise buildings are quite common, European high-rise buildings account for only 5% of all high-rise buildings globally.

London has the largest number of skyscrapers among European cities, with its 100 skyscrapers, placing it only in 48th place among cities with the highest number of high-rise buildings worldwide.

Urban topologies of the distribution of tall buildings within European cities, understood as the rules for the arrangement of high-rise buildings in urban space, are diverse. High-rise buildings are located at the nodal points of urban structures, linearly along the main urban development routes, or according to the local regulations of a given place, specified in local plans, without compositional relations to the high-rise buildings in the entire urban complexity. In most European cities, the distribution of tall buildings is dispersed, with the exception of a few cities where high-rise development is concentrated in business districts similar to the American CBD (Central Business District). This includes the French capital of Paris and La Defense, London and the City of London, and the Frankfurt am Main financial center, and recently also Warsaw, the Polish capital.

Almusaed and Almssad noted that “competition for the construction of the tallest building has created another driver for the growth of tall buildings worldwide. Over the past 20 years there has been a move towards creating iconic constructions that have become major landmarks within the city” (Almusaed and Almssad 2019).

A formal typology of high-rise buildings has been elaborated by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, which proposes “ten approaches to design which may help cities in their quest for an appropriate high rise expression” (Wood 2004).

- (1)

- Abstract Sculpturalism—when a tall building is a piece of three-dimensional art within the city structure;

- (2)

- Cultural Symbolism—when tall buildings are inspired by an element of the indigenous culture of the location (often literally copying the architecture of the past);

- (3)

- Abstract Symbolism—when high-rise designs incorporate elements of local culture as inspiration, included in a subtle, abstract way;

- (4)

- Abstract Conceptualism—buildings with a strong, predominant, philosophical idea, not necessarily related to the setting but which, if well-executed, becomes synonymous with the setting;

- (5)

- Structural Expressionalism—buildings with dominant aesthetic and organizational principles informed by an expression of the structural system;

- (6)

- Locationalism—when tall buildings are rooted in their context by responding to the physical characteristics of the site and its surrounding area; common design devices used include the generation of axes from physical entities, manipulation of form to respond to place, etc.;

- (7)

- Environmentalism—when tall buildings are inspired directly by the climate in which they are located, responding to the opportunities offered by sun, wind, rain, etc.;

- (8)

- Sustainablism—closely related to the above, but taking on the additional specific agenda of sustainability in terms of the construction and operation of the building;

- (9)

- Internalism—when tall buildings are inspired by the concept/organizing principle of the internal spaces of the building, which dictates the design and external expression, etc. (atria, sky gardens, etc.);

- (10)

- Materialism—when buildings are predominantly concerned with an expression of the materials (often the outer cladding), which may be linked to the environmental/sustainability debate (Wood 2004).

Initially, tall building designs were straightforward, favoring traditional shapes such as squares and rectangles (Ilgın and Aslantamer 2024). However, contemporary skyscrapers exhibit diverse atypical structures, including tapered, setback, or twisted forms (Zhang et al. 2019).

2.4. High-Rise Buildings in Poland

In the world’s metropolises, until the spread of high-rise buildings, the first tall structures were icons of cities, their symbols and business cards. It was no different with the Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw, built as a gift from the USSR to the then subordinate People’s Republic of Poland in 1955. Warsaw currently has the largest number of high-rise buildings in Poland. The spatial In Poland, the skyscrapers are located (with more planned) in the metropolitan cities. The majority of high-rise buildings are erected in the capital city of Warsaw. The policy of the city of Warsaw is heading towards a concentrated development of skyscrapers, mainly office buildings, forming the very center of Warsaw around the Palace of Culture and Science, creating a district modeled on the American CBD. In other cities, such as Wrocław, Gdynia, Cracow, Szczecin, and Katowice, high-rise buildings have been built in limited numbers and mostly with dispersed distributions (Table 2). In Wrocław, the tallest building, the Sky Tower, is located outside the inner city, is many times higher than the downtown skyline of Wrocław, and emanates into the city skyline as its single, vertical symbol. The tallest buildings in Cracow are located at transport interchanges: Mogilskie and Grzegórzeckie roundabouts. They represent the urban composition philosophy of emphasizing the nodes of the traffic system structure. In Sopot, the tallest building was located at the harbor wharf, acting as a kind of ‘lighthouse’ and a landmark for ships entering the port of Gdynia.

The authors have introduced a dynamics factor in relation to high-rise objects. The index of the dynamics of the development of high-rise construction was calculated as the total number of projects constructed and those under construction, with a building permit, planned or rejected (i.e., projects for which no building permits were obtained). Table 2 shows the dynamics factor of the planning of high-rise facilities in Polish cities. Warsaw shows the highest dynamics factor, surpassing all the other cities. In cities other than Warsaw, due to the lower rate of construction of high-rise buildings, they are characterized by a dispersed location. This has created a situation in which each new skyscraper appearing in the city space constitutes an important dominant in the urban cityscape—a meaningful symbol in space.

A comparison of individual and group locations shows that the grouping together of tower buildings weakens the importance and individuality of each tall building in terms of its significance and exposure.

This section reveals and summarizes the most important factors influencing the overall assessment of the impact of high-rise buildings on the city space and their perception by citizens. There is a clear tendency to increase the frequency of constructing these types of buildings in Polish cities.

3. Methodology

3.1. The Importance of Methodological Approach in Urban Planning

The methodological approach is very important in the programming and planning of high-rise types of buildings. The example of the building under consideration in this case study, namely the Hanza Tower in Szczecin (PL), reveals the research methodology in the process of harmoniously integrating this structure into the cityscape, including its harmonization with the nearby context and the structural features of the urban center.

This methodology would not represent the full picture if it did not include research in the nature of ex-ante analysis—in advance of the design of the building and its surroundings. In the case of the design of a high-rise building, an important research tool for this analysis turned out to be the VIS research method, which makes it possible to determine on a theoretical model, even before the design is made, what effect the construction of a high-rise building will have on the silhouette of the city and its urban interiors and what height of this building will be best suited to the urban layout of the city on a local and panoramic scale. An extremely important method used in the Hanza Tower project was the ongoing use of multidisciplinary technical knowledge in the creation of spatial solutions and the anticipation of solutions to potential collisions that could arise in projects created by designers from different design branches participating in the design and construction processes of the high-rise building.

The authors present in their analytical approach towards the final design for this case study the key milestones: starting with topographic and urban contextual analyses and a description of historical development and its influence on contemporary urban planning and ending with a final description of the design features of the building, its development in its functional and formal concepts, including the process of finding its geometrical shape, as well as an analysis of its actual impact on the streetscape and cityscape after completion.

3.2. The Methodologies Applied

A methodology is a set of processes and tools designed to achieve the objectives set for the research team. In the case study, the research team assumes a dual role as both the project team and the research team. The authors of the project and this article are fully aware that their assessment of the project outcomes may not be entirely objective. Therefore, they strive to present the research questions, research methods, and their results in the article, seeking to minimize their personal evaluation of the results of this project. The conclusions drawn from this research project have been attempted to be objective. However, the final conclusions will be drawn by third parties who have no connection to the investment project under study. The authors’ participation in the process of conception, design, construction, and scientific analysis of the visual and symbolic impact of the case in question created a unique situation. The researchers, who were the authors of the object in question, at the same time became the subjects of the research. Such a unique construction on the scale of the city of Szczecin posed a serious organizational and construction challenge. In general, the methodology was based on the skills of the expert employed in this particular case. References to other high-rise structures, as comparative studies, were included in a scarce way, mostly through the individual experience of the researchers/planners involved in the research or design process. For the authors of the project, the realization of the building was above all an incredibly difficult test to see whether the architectural and urban planning concept would work in reality, whether such a significant change in the urban space would be interpreted as a positive change, enriching the aesthetics and composition of the city, bringing a new symbol into the urban structure of Szczecin—and above all, what would be the social resonance of the investment would be accepted by the residents? It must be admitted that the structure of the Hanza Tower was not invented out of thin air, as there are similarities with other projects, especially in the type of facade. However, the main subject of this article, the urban analysis in the composition of the city core, is unique and therefore challenging.

3.3. The Scope of Research Methods in the Design, Implementation, and Evaluation Phases

Given the complexity of the research topic, the methodology used in the described research is quite distinct and linked to the research topic. The main method used in this research is the research by design method (Niedziela-Wawrzyniak and Wawrzyniak 2021) and the ex-ante analytical approach, which refers to a study conducted to evaluate a project before its implementation (Niezabitowska 2014). Ex-ante evaluation is primarily used in the construction of spatial policy. When analyzing the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of a region, municipality, or city, an ex ante assessment is the basis for formulating a long-term development strategy. The VIS research is an important tool in the ex-ante analytical process. These methods are essential for the research in architecture. It is assumed that during the design process, knowledge and comments are generated that form the basis for solving the problems that arise. The structure of the research methods has been presented in the Table 3 below.

Table 3.

The structure of the research methods.

Certainly, after the completion of the investment and the first period of occupancy, there will be a wide area of research, ranging from the built structure itself to the social and psychological areas of research, especially the symbolic issues of the building and the emotional responses to high-rise structures. This is the area of research that requires a methodological approach and the involvement of professionals in the field, as well as independent researchers.

4. The Hanza Tower in Szczecin (Poland)—The Case Study

4.1. Range of the Research

Using the multifunctional Hanza Tower building in Szczecin (Paszkowski 2022) as an example presented in the data set below (Table 4), a study of the iconic sphere of influence of a high-rise building was conducted. The object being examined is an example of a high-rise building with a significant compositional and semantic role within the topography of the city and its landscape. Due to its location in relation to the urban axis of the city, the historical context of the place, and its semantic and symbolic context. It can be classified, in terms of its design approach, as lying somewhere between Abstract Symbolism and Abstract Conceptualism (Wood 2004).

Table 4.

Data regarding the Hanza Tower in Szczecin. Source: Urbicon Spółka z o.o., (Szczecin, Poland).

4.2. Topographic and Urban Context

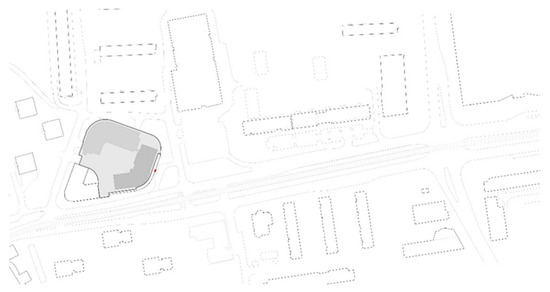

The Hanza Tower building is located at the top of an escarpment overlooking Niecka Niebuszewska, on land that is 26.5 m above sea level and at the level of the Oder River, which provides it with an exposed location within the city context. The building, with a relative height of 115 m, rises to 131.5 m above the Oder River and sea level, making it the tallest built structure in the city. The surroundings of the building are illustrated in Figure 3.

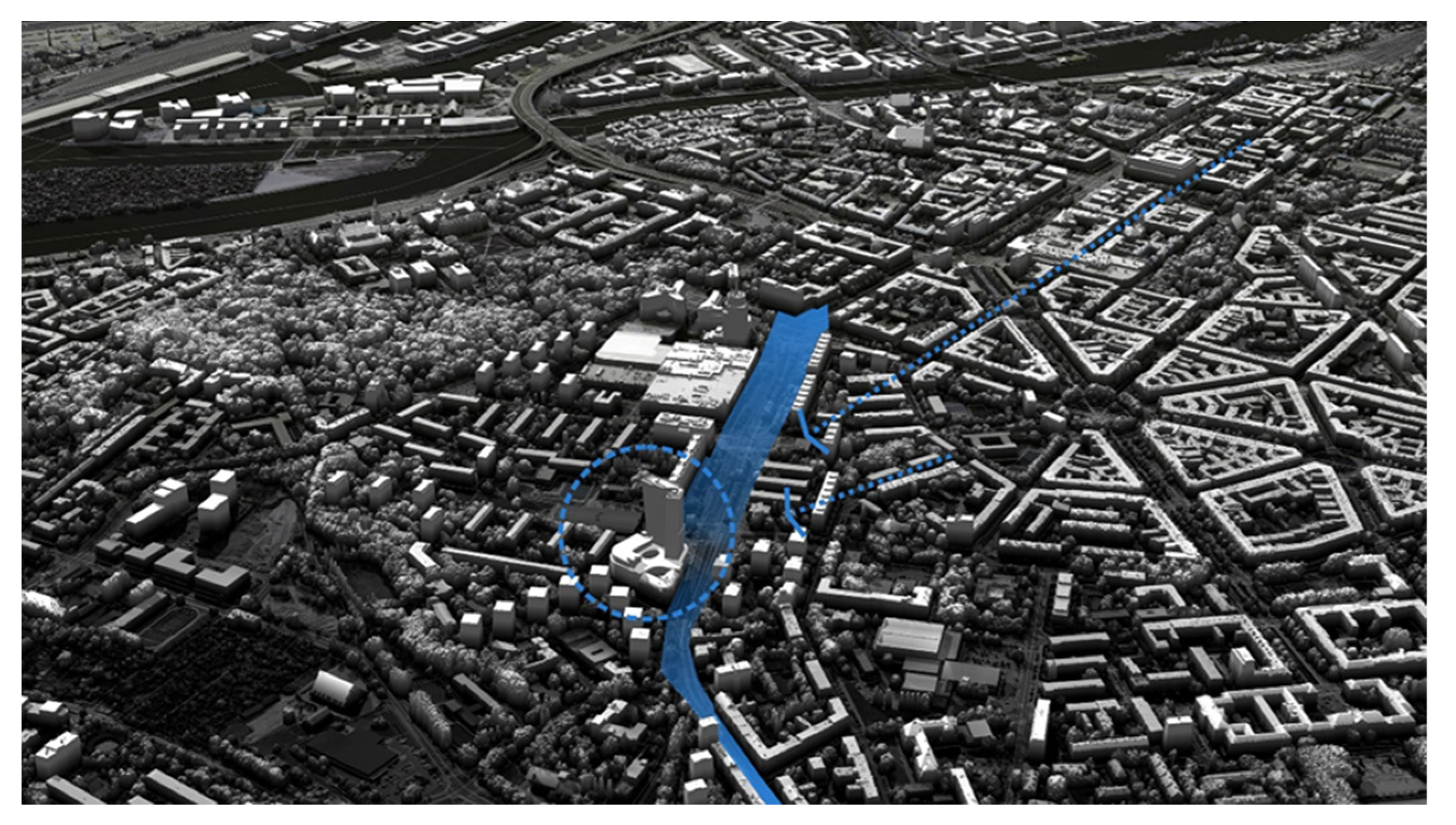

Figure 3.

Urban location of the Hanza Tower closing off the urban interior of Wyzwolenia St. with the perfect exposition of a high-rise building. Source: Urbicon Spółka z o.o. (Szczecin, Poland).

The contemporary urban structure of Szczecin consists of several types of buildings that dominate the area of the city. One quarter of it is made up of street buildings, dating mainly from the 19th and the first half of the 20th century. The tenement houses that comprise this urban structure are about 18–20 m high. In many cases, there are still gaps in the development between them, mainly due to their destruction over time in Allied bombing raids during World War II. The structures of the downtown buildings are interspersed with modernist buildings in the form of apartment blocks and service pavilions, built mainly in the 1960s and 1970s.

4.3. The History of Szczecin’s (Stettin’s) Urban Development

The history of settlement in the area of modern Szczecin dates back to the early Middle Ages, but the first urban forms appeared in the 12th century. In 1243, Szczecin obtained city rights under the Magdeburg Law, and in 1248 it became a member of the association of cities of Hanse (the Hanseatic League). The golden period of the city’s development emerged in the 16th century when, under the rule of the Pomeranian Dukes, the city gained a number of new buildings, including a magnificent castle, dominating the valley of the western arm of the River Oder.

The victory of Prussia over France and the establishment of the German Empire in 1871 significantly influenced the further spatial development of the city. One consequence of these events was Prussia’s receipt of enormous war contributions from France and a redefinition of the security of the German state. A special commission, appointed by Emperor Wilhelm I on 30 May 1873, decided to liquidate eight German fortresses within the Reich, including the fortress in Szczecin (Ptaszyński 2007). As a result of this decision, it became possible to develop an urban agglomeration and expand the city limits to include many surrounding villages and hamlets. Some of the areas left after moats, bastions, and ravelins had been demolished became park areas, but they were mostly converted into construction cones, which enabled the creation of new urban structures for the city and the development of Szczecin.

The urban layout of Szczecin, as a city with a compactly planned composition, has at its core the form of a medieval city founded on a regular plan, slightly distorted by the topography of the terrain, which features an escarpment approximately 20 m high. The part of the city located on the Oder River (known as Podzamcze) is connected to the higher area around the castle of the Pomeranian Dukes and the chartered city by means of a rectangular street grid. The city was once surrounded by defensive walls with numerous masonry towers, a moat, and several fortified gates. In the 17th century, Szczecin gained a new ring of bastion fortifications, which turned the city into a fortress and prevented its territorial development for many years. The main dominant feature of the composition of the medieval city was the Gothic church of St. Jacob, with a tower rising over the city, accompanied by the towers of other churches, the castle of Pomeranian Dukes, and the city hall. The dominant feature of St. Jacob’s church tower has significant compositional importance even to this day.

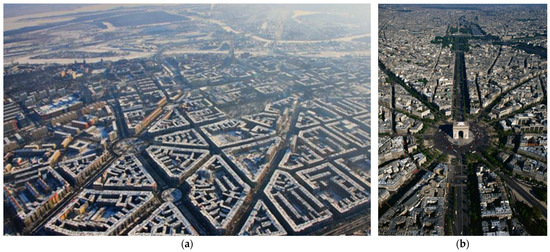

The first city development plans in the area of the former fortifications were drawn up by city construction advisor and engineer James Hobrecht (Gwiazdowska 2016) in 1864. Beginning in 1859, he was in charge of developing a new plan for the expansion of Berlin. In connection with this undertaking, he made a 3-month study trip to Hamburg, Paris, London, and other English cities in 1860, acquainting himself with the plans being undertaken there and the implementation of city reconstruction. It is worth mentioning that it was at this time that the reconstruction of Paris, led by Baron Georges Haussmann, was underway. In London, after the ecological disaster of the poisoning of the Thames River by sewage in 1858, known as the Great Stink, a modern municipal sewage system was being built. James Hobrecht drew directly on these experiences when planning the urban expansion of the capital of Prussia, Berlin, and thereafter in his plans for the urban development and sewage system of Stettin (Szczecin). After receiving approval on the plan for the expansion of Berlin, Hobrecht left Berlin and took the position of building counselor in Szczecin, where he worked for 7 years (Łopuch 1999). This history helps to explain the similarities between the urban planning and infrastructure of Szczecin and the plans for the reconstruction of Paris and London illustrating the modernity and affinity of their conceptions (Figure 4). Ultimately, in 1874, the Szczecin City Council decided to correct James Hobrecht’s plans, leaning toward the solutions applied in Paris by Georges Haussmann. The mayor (R. Burscher) and the construction advisor (K. Kruhl) were advocates of this concept. The plan for the main urban axis of the new streets of Szczecin adopted a French-style pattern: a star-shaped arrangement of streets radiating from a large main circular square (Grunwaldzki Square in Szczecin—8 streets; Place Charles de Gaulle in Paris—12 streets). The creation of the star-shaped squares of Szczecin is accompanied by legends about their compositional location, similar to those used in the construction of the pyramids at Giza in Ancient Egypt. Another concept mentions astronomical patterns and refers to their composition according to the constellation of stars in the Orion Star Constellation.

Figure 4.

(a) The XIX c. Szczecin tenant housing structure with roundabouts is the planning result of Hobrecht and Kruhl. Source: photo by courtesy of C. Skórka. (b) A view of the Place d’Etoile with the Champs Elysee axis in Paris, the often-quoted example for Szczecin’s urban structure provenance from the French urbanist Haussmann. Source: Wikipedia commons.

When the fortress bastions were demolished and new residential districts were planned for the developing city, the dominant feature of the tower of St. Jacob’s church was treated as the starting point for the main axes of the city streets, extending beyond the downtown layout, and constituting the framework for the future spatial development of the city. The second determinant of the layout of these main streets as the developmental axes of Szczecin was Parade Square, adjacent to the western line of the fortifications. James Hobrecht, the author of the city expansion plan, also marked out the peripheral streets and designed roundabouts at the intersections of the main city arteries. The developments built along these designated lines were accentuated at the most important street intersections by means of tower corners in original forms, with compositional accents, emphasizing the expressive layout of the city’s spatial composition.

As a result of the loss of the Second World War by the German Reich (1939–45), the structure of the city of Szczecin was largely ruined by bombing raids by the Allied forces. The peace treaty of Potsdam in 1945 assigned the eastern territories of Germany, including the German industrial port city of Stettin, one of the most important centers of the war industry of the Third Reich, to Poland. The reconstruction of the cities in the territories obtained by Poland was carried out in the spirit of the ‘social realism style’ up to 1956, in a similar manner to that of other countries of the Soviet bloc, and later on in the CIAM-style modernism of the 1950s and 1960s. In the reconstruction of cities, the idea of recreating the urban layout of the Prussian (German) period was initially strongly rejected in favor of modern urban planning and the modern ‘big plate’ concrete housing blocks of the time. The 1980s and 1990s brought further changes, which were reflected in the development of Szczecin, leading to a change in the ownership of the properties and enabling the present location of the Hanza Tower (processes of communalization and privatization of previously state-owned lots). These events began a new chapter in the history of this place and, consequently, that of the City of Szczecin.

The postmodernism of the 1990s introduced integrative thinking in urban development, allowing both reconstructive and modern methods of urban recovery and development.

The year 2004, the year of Poland’s accession to the European Union, marked a new chapter in the history of the city. There was an obvious desire to emphasize this fact in Szczecin, to emphasize Szczecin’s wish to ascribe to Western cultural values and to highlight the opening of a new page in its history. This need to create a symbol of the present day in a city still spatially fragmented and largely degraded coincided with the idea of building high-rise buildings as signifiers, marking this significant moment in history. The Hanza Tower, with its iconic layers, has become a symbol of this new launch of a European Szczecin. The name of the Hanza Tower skyscraper was chosen as a reminder of the historical affiliation of Szczecin to the European trade association of cities from the 13th to the 16th centuries (the Hanseatic League).

Many studies have already been conducted on the subject of urban change and the development of Szczecin in the period from 1871 to the present day. This subject has been explored by (Stępiński 1994), (Włodarczyk 1994), (Kozińska 2002), and (Gwiazdowska 2016), among others.

4.4. The Context of the Hanza Tower Location

Architecture is always place-connected and place-building. The location of the Hanza Tower is marked by a history of numerous transformations. The first buildings in this area were built in the nineteenth century as an enclosure of the communication route running north from the city center to the town of Police through multi-story tenement houses. In the 1930s, at the corner of Wyzwolenia St. and Odzieżowa St., an industrial building for men’s clothing (Herrenkleiderfabrik) was built, which was soon turned into a department store for Karstadt AG.

After the end of World War II, the ‘Karstadt’ company was replaced by a Polish state-owned clothing company called ‘22 Lipca’ (Eng. trans. ‘July 22’), which produced uniforms and workwear on a conveyor belt system. In 1967, the clothing factory received a new name: ‘Dana’. The company developed very well, which allowed for the construction of additional production halls in a modern, eight-story building in the 1960s, the Hanza Tower building predecessor. The Dana Clothing Industry plant employed over 3.5 thousand people at the peak of the company’s development. The symbolism of this place as a historic workplace for many people is an important element of this location, and the clothing company once operating here is clearly associated with the rise of Szczecin as a city of modern fashion.

4.5. The Development History of the Hanza Tower Concept

In 2008, the first concept of a high-rise building on the Dana Clothing Industry site was created. From the very beginning, the existing, oldest part of the former Dana clothing plant complex had been planned for adaptation. This unique building, symbolizing the architectural style of early modernism with artificial concrete façade cladding from the 1930s, has been declared to be of conservation protection status. This monumental corner building has finally been converted into the four-star Hotel Dana. The clothing factory adjacent to this building in the 1970s was, under the new plans, outlined for demolition. In its place, the concept of a residential building over 100 m high, featuring balconies and a glass façade was developed. The authors of the initial concept for the development of this area came from the architectural office of Laguarda Low (Dallas, TX, USA) (Figure 5). Following 2008, further design work on various concepts and project details was carried out, and under the author’s supervision, the implementation of both the Dana Hotel and the Hanza Tower high-rise building was realized by the co-author of this article, Prof. Zbigniew Paszkowski PhD Arch. DSc., Barbara Paszkowska MSc. arch., along with their Szczecin-based Architectural Design Office Urbicon Spółka z o.o. (Szczecin, Poland), using a multi-branch team (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5.

(a) The initial concept of the building by Laguarda Low Architects from Dallas (USA) Source: urbanity. (b,c) The final concept (visualization) of the Hanza Tower project and the Hotel Dana restoration project was performed by Urbicon Spółka z o.o. as permitted for construction by the Municipality of Szczecin. Source: Urbicon Spółka z o.o.

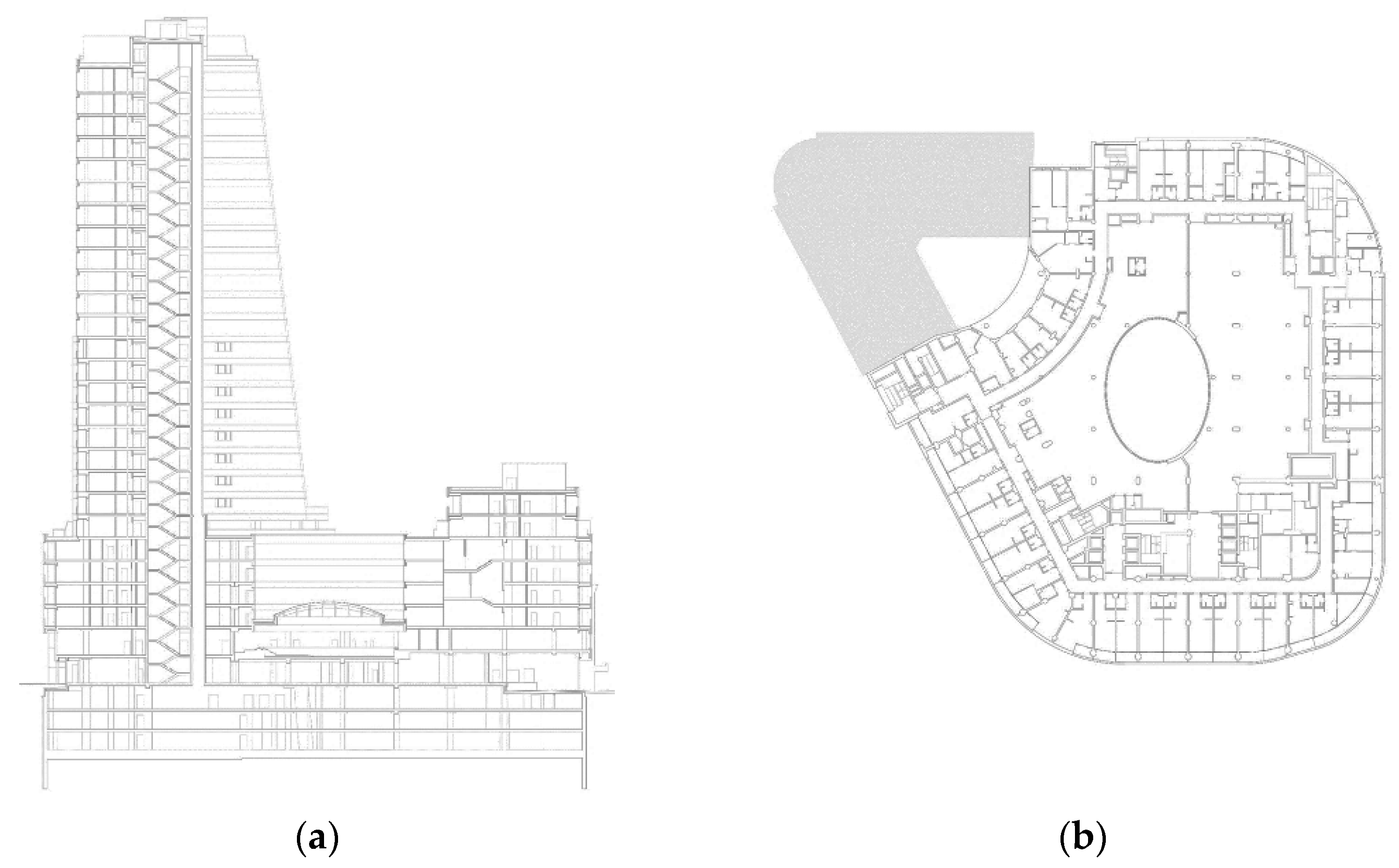

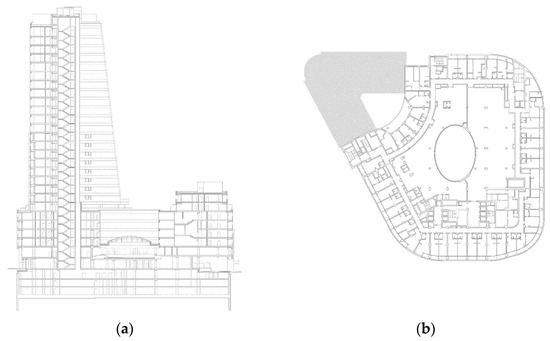

Figure 6.

(a) Cross-sections of different parts of the building with differentiated heights. (b) The footprint of the floor of the building’s podium. Source: Urbicon Spółka z o.o.

Numerous different concepts for the use of the planned high-rise tower were created, which naturally also influenced its shape. This volatility of the concepts was the result of local changes in the real estate market related to the global financial crisis that impacted the global economy in 2008. This situation contributed to delays in the construction of the facility and led to many design changes, dictated by changing external conditions and social needs.

4.6. Geometry of the Hanza Tower Building

The structure of the Hanza Tower is not freestanding but is adjacent to the historic corner building with a sandstone-clad facade, which was adopted for hotel purposes and serves as part of the overall Hanza complex. The context of this historic building was essential in the creation of the lower part of the Hanza Tower, known as the podium. The six-story podium fulfills several compositional roles: it reveals the scale of the neighboring buildings, “captures” the human scale of the complex, and aligns with the street lines and the partially rounded boundaries of the site. The podium, in the shape of an irregular oval with six floors, features neutral graphite large-format ceramic tiles cladding the façade, with cut-in openings for windows and loggias. To adapt to the social and commercial function of the ground floor, the podium received modern double-storey high arcades from the street side, supported by powerful columns to invite clients and residents and to provide a human scale entrance. The main entrance to the building is open onto a small roundabout, providing a comfortable driveway to the front door. The roof above the podium is partly occupied by a roof garden and partly by the technical rooms of the air conditioning system. This technical part was designed to be hidden behind a steel lattice structure, which serves as a support for plants, which will form a green cover over the technical part of the roof. The largest part of the roof on the podium is occupied by the high-rise element, the so-called tower, which reaches 22 floors above the podium and contains more than 500 apartments, with a height of 115 m from the level of the ground floor entrance area. The high-rise Hanza Tower building, particularly its glazed and dramatically slanted tower, is visible from many points of the city and in panoramas viewed from a distance (Paszkowski 2022).

The composition of this object in shots from a close perspective is formed by the piling up of shapes, starting from the so-called podium, through to the superstructure, which features a curved boomerang-like projection, to the slightly rising, tilted tower part of the building. In the design process, one of the priorities set up by the developer was to retain the sail-like form of the tower part of the building and its height.

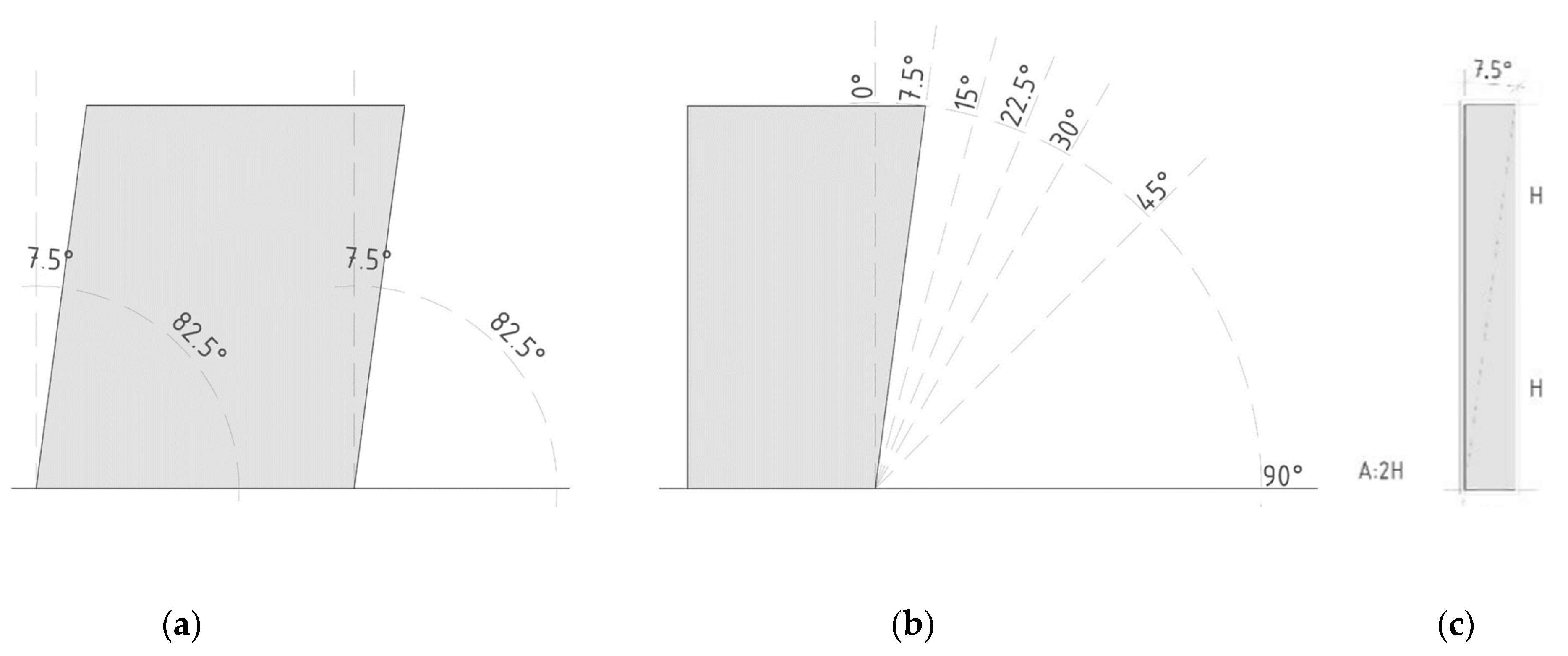

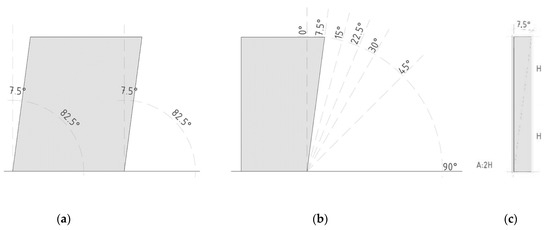

The ends of the curved tower part of the building are cut at an angle of 7.5 degrees—one end angled outward and the other one angled inward. Slanted walls were designed, rising to a height of more than 100 m with a curved façade (Figure 7). Shaped in this way, the geometry of the building’s architecture creates a structure such that, when viewed from different sides of the building and from different distances, a very different image of its spatial shape emerges. The observation of this geometrically complex architectural mass reveals an interesting phenomenon of the apparent variability of the shape of the mass and its aesthetic potential, depending on the point it is observed from (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

(a–c) Diagrams of the facades (a,b) of the upper part above the “podium” of the Hanza Tower show the relationship between the height of this part of the building’s floor and the 7.5° angle of the sloping side walls. Scheme (c) shows the proportions of the modular division of the facade grid. The module of the facade grid with A—width, H—height, by 2H (two heights of the module) has a diagonal slant with an angle of 7.5°. Designed by the authors.

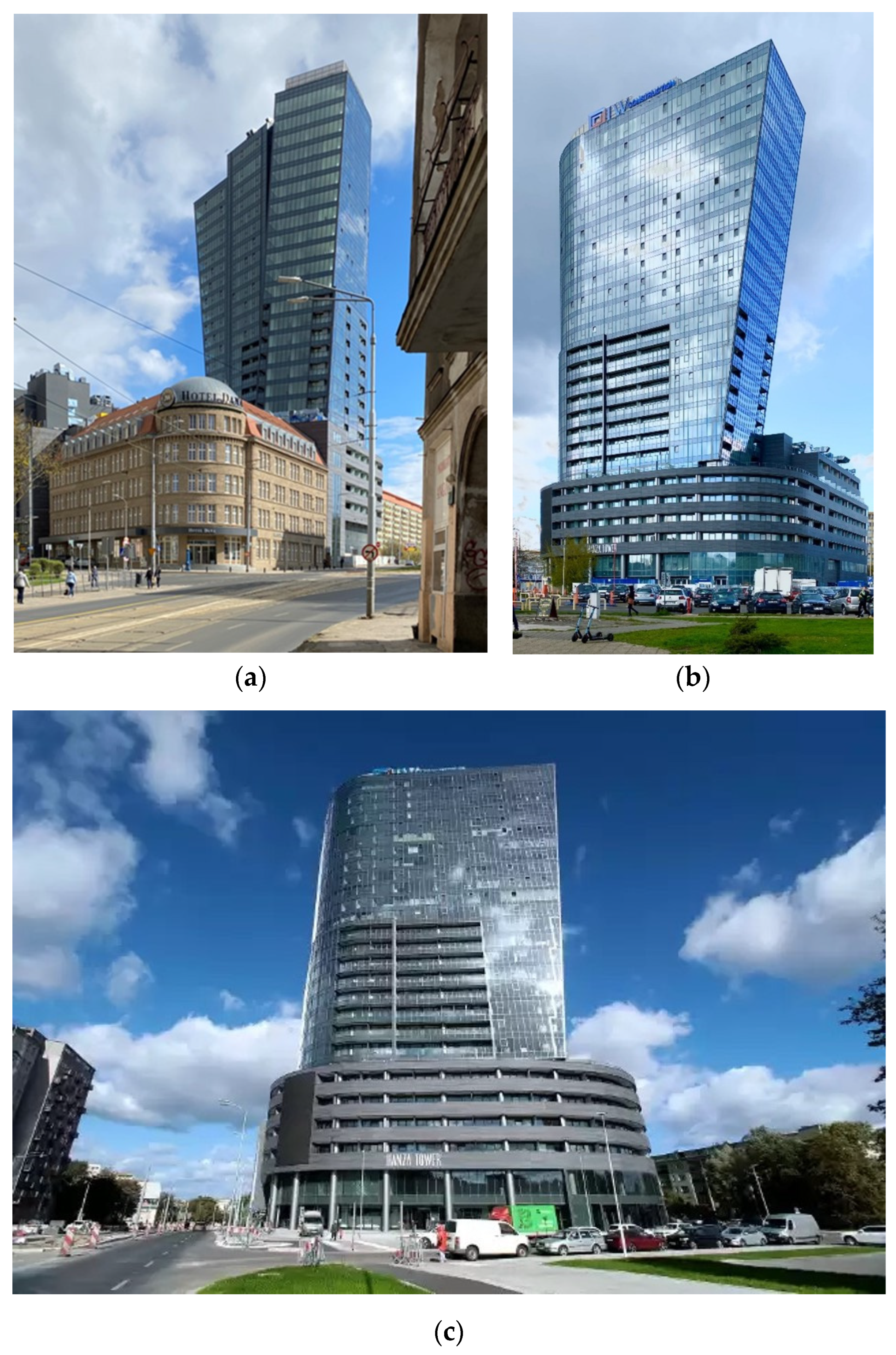

Figure 8.

(a) The front corner and the facades of the adjacent building of Hotel Dana in its realized form, 2023, present a truthful connection of old-fashioned and modern facades aligned along the street line with corresponding roof heights. (b,c) The Hanza Tower building in its realized form, 2023, presents aesthetic potential depending on the point of observation. Photos taken by authors.

4.7. The Hanza Tower in Urban Composition

The urban composition of the city of Szczecin, defined by James Hobrecht on the basis of the building regulations of the Prussian state, consists of straight streets intersecting at various angles. These streets form quarters of compact five-story buildings with pulpit or steep roofs covered with ceramic tiles. The quarters are built of adjoining townhouses with drive-through gates and inner courtyards. The corners of the quarters are beveled and accented with turrets in the roof structure with individual character. Street axes are oriented to buildings that are historical spatial dominants. The most characteristic elements of the urban layout of the streets are street traffic roundabouts, surrounded by tenement houses and featuring a green area in the center. Some streets are avenues with a green belt in the axis of the street with rows of trees. Streetcar tracks have been laid in the axis of wider avenues. The streetcar is the primary means of public transportation, introduced in Szczecin back in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The principle of creating sectional, straight streets, axially connected by roundabouts and accentuating the corners of intersections with taller buildings, became the dominant principle of spatial design of the urban structure during the expansion of Szczecin in the 19th century. After the tragic destruction of the city during the Second World War, during the post-war reconstruction period, this rule, although abandoned in favor of socialist modernism, did not lose its significance. Destroyed street frontages were rebuilt along the lines of their original composition, with tall buildings placed at roundabouts. It was in this context of the permanence of the general compositional layout of the city, defined in the 19th century, that the idea of building the Hanza Tower was realized.

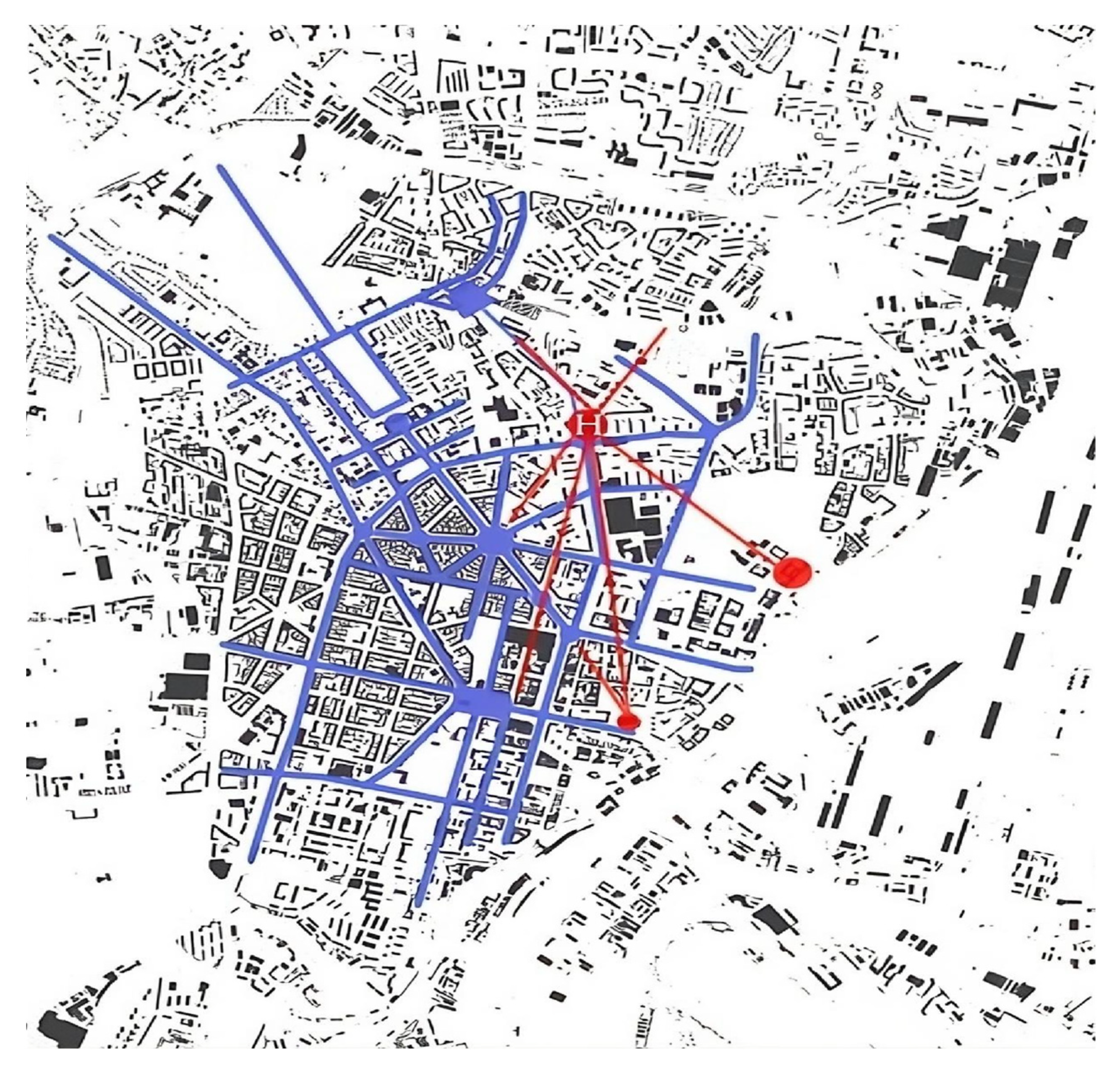

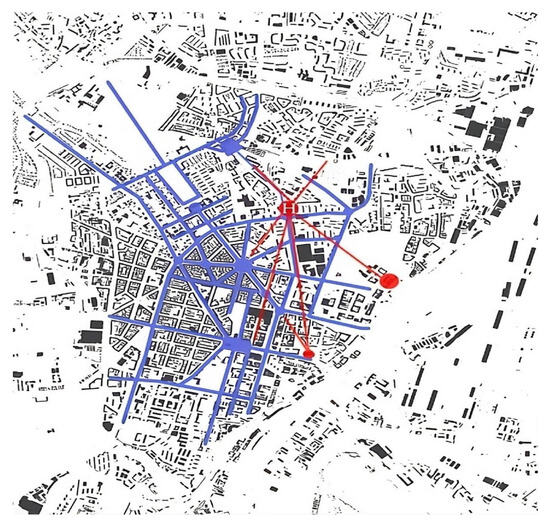

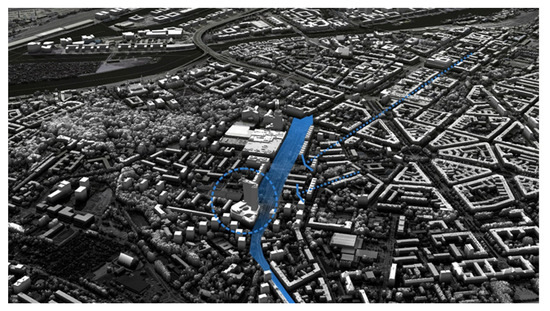

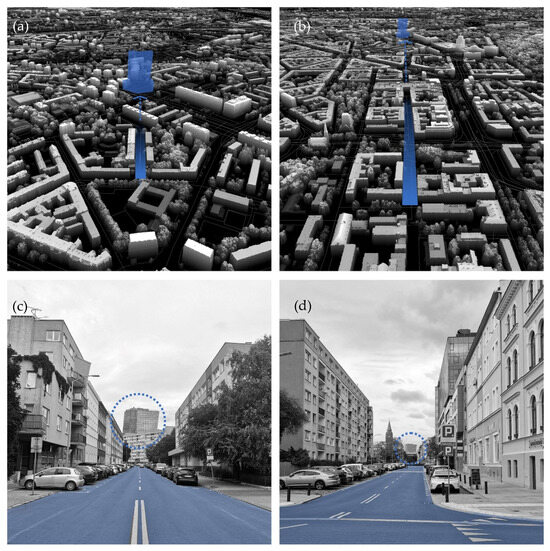

The urban composition of the Szczecin city center plays an important role in the perception of the Hanza Tower building. We can distinguish two basic characteristic types of views: wide riverside panoramas and narrow street perspectives. The first type is associated with the exposure of a large part of the city, in which we can see the most important spatial dominants of Szczecin. In these panoramas, the Hanza Tower is usually visible in the company of another high-rise building—the Pazim building (Figure 1). In the second type of view, the Hanza Tower is at the culmination of the axes of some streets in the city center. The street axes marked in the illustration (Figure 9 and Figure 10) constitute a diverse background, on which the skyscraper is superimposed. The wide viewing area of Wyzwolenia Avenue displays the building from the very ground floor (Figure 8c). From the narrow visual perspectives of Podhalańska Street (Figure 11a,c) and Kaszubska Street (Figure 11b,d), the building is visible at the visual closure of the streets. In this case, it adds depth and interest to the observed perspective, encouraging the observer to move in that direction.

Figure 9.

The urban composition of axial streets connecting the roundabouts and squares that form a network of relationships and dependencies in Szczecin’s city center (marked in blue). The red dots indicate the locations of the main urban dominants (Hanza Tower, St. Jacob’s Cathedral, and the Provincial Government Building), adding a network of visual connections (marked in red) and focal points related to the urban composition. Prepared by the authors.

Figure 10.

Localization of the Hanza Tower in the urban composition, with selected street axes highlighted in blue. Visualization of DSM model of Szczecin by authors.

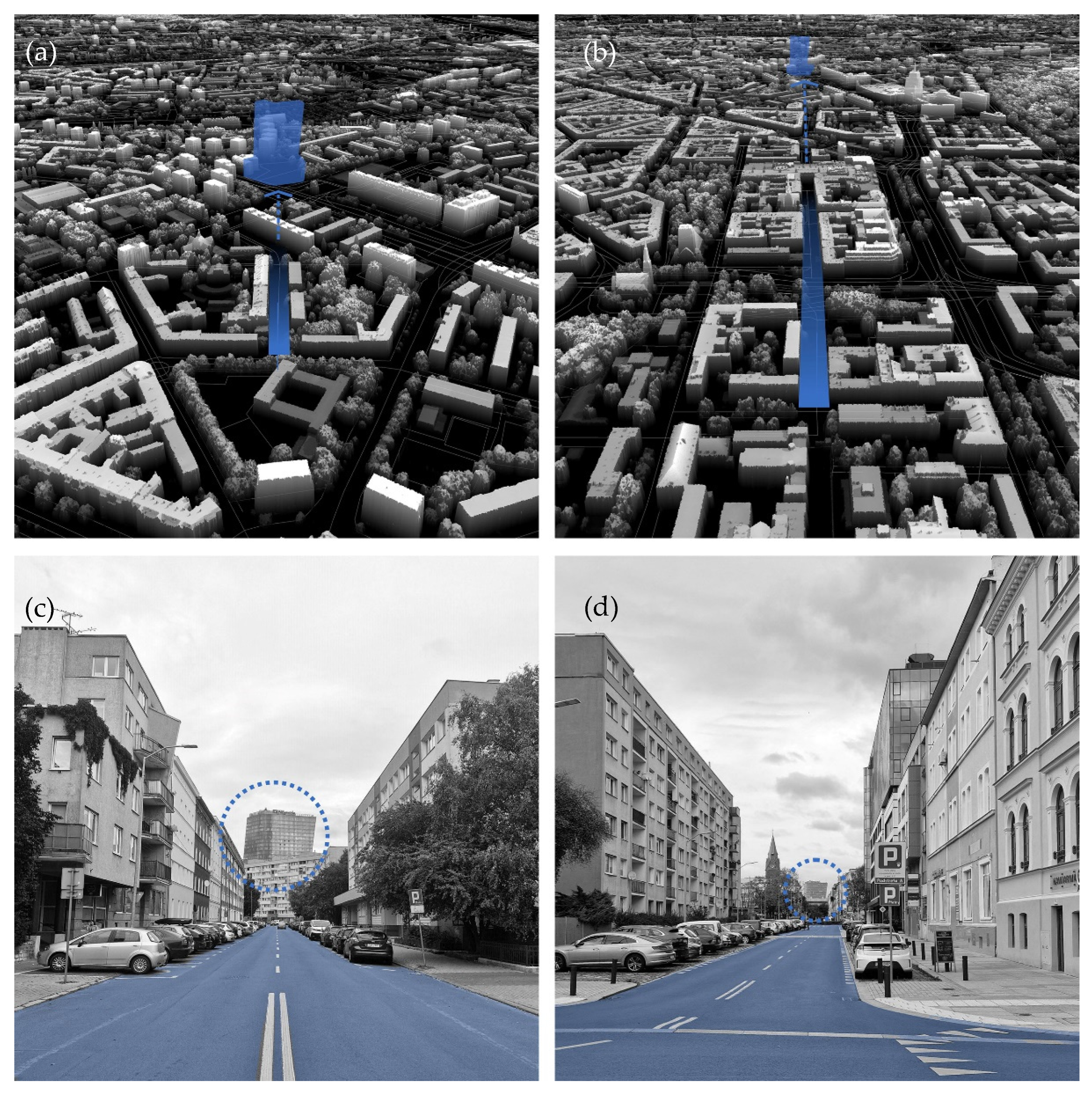

Figure 11.

The Hanza Tower is an element of the urban composition visible at the end of the Podhalańska and Kaszubska street axes—here shown on the photos and visualizations projected onto the Digital Surface Model (DSM) of Szczecin. The DSM is a high-resolution, three-dimensional representation of the Earth’s surface, including all objects and features present on it. The visualizations are rendered by the authors.

As illustrated by the photographs in Figure 11, the location of the Hanza Tower building at a nodal point in the urban layout of Szczecin’s inner city allowed for spatial closure of urban interiors and the establishment of a better spatial orientation in the city. In the narrow visual perspectives of Podhalańska Street (Figure 11a,c) and of Kaszubska Street Figure 11b,d), the Hanza Tower is visible at the visual closure of the streets. In this case it adds depth and interest to the observed perspective, encouraging the observer to move in that direction. The location of the high-rise building in the compositional node of the urban structure of the city consolidates and stabilizes this structure, contributing to the clarity of the composition of the entire city.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Summary of the Research Results

The theoretical, introductory part of the paper discusses the development of high-rise buildings within contemporary urban planning and their role and significance within urban composition. However, the location of high-rise buildings is not usually preceded by research on their impact on the city’s silhouette and surroundings, nor in relation to their deliberate location at the nodal points of a city’s urban composition. Many contemporary high-rise buildings are located in areas referred to as the CBD (Central Business District), purchased by investors, and not always selected on the basis of a pre-implementation analysis of their location and their impact on the urban structure and surroundings (Example: Warsaw CBD).

Modern tall buildings are constructed mainly as solitary, self-presenting sculptural objects with little regard to or without reference to their context. This might be a sign of the atrophy of urbanism or simply an approach without regard to the existing built environment (Example: Sky Tower Wrocław, Sopot residential towers).

High-rise buildings evoke several concerns regarding their rationality and influence on the local and global climate, depending on personal attitudes. In the analysis of this social approach, reported in Section 2.2, such extreme differences are described in more detail.

The architectural form of skyscrapers in Poland reflects the demands of the capital market in Poland and the local ambitions of particular cities. Skyscrapers are the majority of investments of foreign entities, and then their architecture usually reflects current global trends, or the construction plans of domestic investors, for whom one of the main determinants of architectural form is the relationship of price to aesthetic effect, with an obvious preference for optimal prices. In this situation, it is difficult to talk about architecture that reflects or develops world trends. This is all even more difficult in buildings with a residential function, where the ultimate owners become housing communities bringing together the owners of individual units, for whom the high cost of purchasing a unit and the cost of apartment maintenance is a major concern, and architectural form plays a minor role, despite its importance for marketing reasons. In this situation, one should view the emergence of high-rise buildings with a residential function (as is the case with Hanza Tower) as an exceptional phenomenon.

An important feature of Hanza Tower is that its architecture is derived from its urban context, and together with the old, adopted remains of the urban fabric, it builds a unique and significant composition, marking new times in the development of the city of Szczecin.

Szczecin is an ambitious city, but with a strong sense of being undervalued as a city far from the national capital and other metropolitan centers. This sense of being on the margins of major developments in Poland, including trends in the construction of high-quality high-rise buildings, has been reduced with the construction of the high-rise Hanza Tower. This investment was not only the ambition of the investor but was also positively received by the public of Szczecin already at the stage of the design concept.

High-rise buildings in Polish cities with a similar ambition have been built or are planned in Wrocław, Sopot, Rzeszów, Toruń, Poznań, or Kraków, among others.

The Hanza Tower, designed by a local architectural firm well-informed about the character of the city and its historic development, illustrates a contextual approach to architectural design. It maintains a relationship to its context due to the division of the building into a podium section, aligned to the scale of the surrounding buildings, and the tower section at the scale of the city panorama.

The dynamic shape of the curved tower evokes the form of a sail, symbolic of the city of Szczecin, which is surrounded by rivers and lakes, creating a gateway to the open sea, and is a well-developed sailing hub with marinas, a port, shipyards, and other maritime facilities. In this way, not only is the urban location of this tall building significant, but also its architectural form, having a significant, symbolic meaning for the city of Szczecin. The Hanza Tower is an example of comprehensive urban planning in relation to the placement of a high-rise building at a nodal point, through which the building has become an integral element of the city’s urban structure.

Due to its unique architectural form and height, the Hanza Tower is a special skyscraper that meets the criteria of a work of architecture, as this building has also become a significant new element in the overall urban plan of the city of Szczecin. As can also be seen, due to VIS ex-ante analytical studies, although the Hanza Tower is visible from far distances, the height of the building does not interfere with important views of the panoramic silhouette of Szczecin, in particular the view of the Wały Chrobrego urban layout from the other bank of the West Oder.

In addition to its significance in the panorama and urban structure of the city, Hanza Tower has improved the quality of the space around the building. A new public space is being created around the project with an entrance plaza, a new street, and green areas emerging. A traffic roundabout with the streetcar line has been rebuilt at the foot of the skyscraper as a further improvement of the urban infrastructure, perpetuating the ’star constellation’ of Szczecin’s urban concept.

This architectural project was implemented adopting the concept that the building would serve as a multi-functional facility with combined residential, service, commercial, and congressional functions. In addition to the pure pragmatism of its functional and spatial layout and the use of technical solutions ensuring the functioning of the building, an architectural form of unique shape and method of articulation has been created: a form that is both complex and multi-faceted, despite the simplicity of the means of its external formal expression. The Hanza Tower building, together with the adjacent historic building, the so-called Old Dana, which has been converted into a hotel, has created a unified complex that consciously displays the differences in scale and architectural form, without hiding the effect resulting from the passage of time between the two architectural structures: the old and the new one. The composition of the Dana Hotel, which is a medium-height block with a classic ceramic multi-sloped roof, set against a structure over 100 m high with a structural facade, creates a spatial tension that enhances the mutual context of these two extremely different worlds of architecture.

5.2. Discussion

Several discussion points concerning the erection of the Hanza Tower building are presented in the second section of this paper. In many cases, high-rise buildings may be viewed as oppressive or contributing to a reduction in the quality of city life.

The construction of high-rise buildings in the city, despite the different feelings they evoke amongst the inhabitants of the city, is, however, inevitable. This is due to the direction of the development of construction and architecture, the shrinking area of land available for development, as well as the ambitions of investors and their customers’ dreams of living above the clouds. Tall buildings will be perceived for many years as the carriers of an urban identity. High-rise buildings should be accepted by residents because they mark progress in technical development and symbolize prosperous cities (Oleński 2014; Twardowski 2020). Regardless of the genesis of high-rise buildings, they are perceived as a symbol of a city’s development and prestige (Jasiński 2008).

There is also great concern about car parking spaces. The location of a high-rise building should provide good accessibility and the ability to park cars in built-in parking spaces, which have been provided in the Hanza Tower on three underground levels. It is, however, also a matter of urban policy to provide and promote public and alternative means of transportation in cities of growing density (Zadeh and Pati 2014).

From the point of view of an integrated landscape and heritage protection approach, concerns are being voiced about whether tall buildings disturb the historical composition of a city. It is obvious that tall buildings should not interfere with the city’s historical composition or significant views of city panoramas. This can be examined before construction permission is granted. In order to fulfill this condition, an initial analysis should be performed, and protection zones established. This does not mean, however, that tall buildings should not be built at all. Every case should be carefully examined on its own merits (Ghazaleheniya and Akçay 2023).

Tall and high-rise buildings, similar to other objects of local importance, such as historic buildings, as well as street grids, green areas, river embankments, public places, and even industrial facilities, should play their compositional role within the city, making it comprehensively functional and accessible for all, as well as safe and sane. Some studies indicate that the spatial heterogeneity of high-rise buildings in terms of their height and use exists across multiple spatial scales, which also provides some insights for urban policymakers and planners (Zhang and Tang 2023).

Szczecin is an interesting example of the compositional analysis of a city. Taking Szczecin as an example of a mature philosophy of urban composition is justified because the historical development of the city has resulted in Szczecin becoming a city created on the basis of an urban composition of axes, avenues, dominants, and architectural accents arranged in the carefully organized order of a street network. The tradition of this method of urban planning, beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, coincides with the reconstruction of Paris by Baron Haussmann, the reconstruction of London, and James Hobrecht’s expansion plans for Berlin. The layout of street roundabouts surrounding the downtown area of Szczecin was designed by James Hobrecht, the same architect as that of the Berlin expansion plan, and was also influenced by the late Baroque urban layout of Baron Haussmann’s transformation of Paris.

Moreover, it is also worth mentioning the historic towers of significant buildings in the city of Szczecin: these urban accents within the city’s structure have become important elements of its historic urban layout. A characteristic of this concept is the accentuation of the corners of the tenement houses of the 19th-century quarters with turrets. The Hanza Tower building represents the next generation of this large-scale ‘stellar structure’ model of urban planning, which began in the 19th century and is likely to be continued into the future, but of course, updated with modern architectural forms.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Case Study Conclusions

The urban structure can be seen as a set of historical layers, which (if possible) should remain legible within the urban structure, even after crucial transformative changes. The central city area of Szczecin is an example of these changes and the careful urban planning in order to recreate the well-structured fabric of the city.

As a result of research using tools such as the Visual Impact Size (VIS) method, the height of the Hanza Tower was adjusted in the pre-planning stage of the project to match the scale of the cityscape and built environment in its vicinity.

The architectural form of the building, which falls somewhere between Abstract Symbolism and Abstract Conceptualism (Wood 2004), was shaped in the unique form of a large sail, a reference to the maritime character of the city of Szczecin—a place of sailing marinas, a seaport, and shipyards. In addition, the tilted and curved walls of the tower give it a dynamic character. The public acceptance of high-rise buildings in the city as elements carrying symbolic value depends, to a great extent, on the social recognition of their architectural form and on their different connotations in meaning.

The analyzed building (Hanza Tower) is situated in the context of the historical urban composition of Szczecin, accentuating the nodal point of the historical street grid composition and creating a new enclosure of the representative avenue by transforming one of the most important central axes of the commercial section of Wyzwolenia Street, connecting the Hanza Tower with the Old Town area.

It is expected that the construction of the Hanza Tower building will have a positive domino effect, i.e., it will contribute to the gradual modernization of the neglected area around the skyscraper. In this way, this urban acupuncture with its architectural icon will contribute to urban renewal, stabilizing the original urban concept of Szczecin, which began over 150 years ago, and opening the structural urban planning for future development.

The urban location of the Hanza Tower building is an expression of contemporary trends in architecture, whilst at the same time referencing the historical composition of the city by maintaining the street line and combining modern architecture with the historic building of the Dana Hotel.

This case study shows that modern architecture does not have to oppose history but can, in fact, be a contemporary interpretation of its continuation.

6.2. General Conclusions

High-rise buildings are important structural elements within the urban composition of cities, which can contribute to their flourishing and development. They can influence the cityscape positively due to the three-dimensionality of their urban composition, strengthening the disposition of urban districts of important significance, the layout of main streets, and the performance of outstanding pieces of architecture. Therefore, analyses that enable the precise simulation of the impact of planned high-rise buildings on the cityscape are crucial.

Situating high-rise buildings in an existing city within a balanced scale of development requires careful analysis. Mistakes in the location of tall buildings frequently result from the inability to foresee the impact of a new building on a cityscape and on the existing, often historic urban structure and can cause the urban composition to deteriorate. Simulations also have to be undertaken to confirm the positive visual impact of tall buildings seen from observation points from remote distances, with the aim of securing the expected, significant influence of high-rise buildings on the cityscape.

The creation of city districts with a predominance of high-rise buildings means that within the general landscape, the perception of a complex of tall and high-rise buildings and their compositional and architectural distinction and individualism is less clear and therefore more difficult to define.

The location of tall buildings in the city’s urban structure as singular, self-presenting objects should contribute to the creation of the urban composition of the city as a whole.

The construction of high-rise buildings in metropolitan city centers is not just the result of the ambitions of cities and private investors. Growing urbanization pressures already require planning for their location in the centers of existing cities. Therefore, in order to minimize the negative effects of inner-city locations of tall buildings and to create new spatial values in cities, further studies on methods for selecting the best locations for tall buildings are necessary. It is also necessary to carry out further research into optimizing the planning of tall buildings, including in particular the difficult issue of analyzing the relationship of planned tall buildings to existing historic urban structures.

The location and height of tall new buildings, if properly situated and planned, can enhance the value of existing urban layouts and cultural heritage, combining new and old structures into interesting compositions and presenting a visual timeline of urban, technical, and artistic developments. The approach toward the urban development presented in the above statements we can describe as the sustainable urban composition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.W.P. and K.C.; methodology, Z.W.P. and K.C.; software, K.C.; validation, Z.W.P. and N.E.P.-K. formal analysis, K.C.; investigation, K.C.; resources, Z.W.P. and N.E.P.-K.; data curation, Z.W.P.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W.P.; writing—review and editing, N.E.P.-K.; visualization, K.C. and N.E.P.-K.; supervision, Z.W.P.; project administration, Z.W.P.; funding acquisition, K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the West Pomeranian University of Technology in Szczecin.

Data Availability Statement

Visualizations and spatial analyses were performed using our own software created at the West Pomeranian University of Technology in Szczecin. The analyses used a 3D model of the city built from a regular point cloud: DSM and DTM. This data is publicly available on https://mapy.geoportal.gov.pl/ accessed on 10 December 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Natalia Emilia Paszkowska-Kaczmarek was employed by the company Urbicon Spółka z o.o. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Akristiniy, Vera, and Yulia Boriskina. 2018. Vertical cities—The new form of high-rise construction evolution. E3S Web of Conferences 33: 01041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Mir Maqsud. 2010. Sustainable urban life in skyscraper cities of the 21st century. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 129: 203–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Mir Maqsud, and Kheir Al-Kodmany. 2012. Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat of the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. Buildings 2: 384–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusaed, Amjad, and Assd Almssad. 2019. City Phenomenon between Urban Structure and Composition. In Sustainability in Urban Planning and Design. London: IntechOpen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyńska, Klara. 2018a. A brief history of tall buildings in the context of cityscape transformation in Europe. Space and Form 36: 281–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyńska, Klara. 2018b. High Precision Visibility and Dominance Analysis of Tall Building in Cityscape. Computing for a Better Tomorrow 36: 481–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyńska, Klara. 2020. Computational Methods for Examining Reciprocal Relations between the Viewshed of Planned Facilities and Historical Dominants—Their integration within the cultural landscape. Paper presented at the Anthropocene, Design in the Age of Humans—Proceedings of the 25th CAADRIA Conference, Bangkok, Thailand, August 5–6; Edited by Dominik Holzer, Walaiporn Nakapan, Anastasia Globa and Immanuel Koh. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University, vol. 1, pp. 853–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyńska, Klara. 2021. Selected aspects of tall building visual perception—Example of European cities. Space and Form 48: 241–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyńska, Klara, Waldemar Marzęcki, and Paweł Rubinowicz. 2022. Protection and Development of the Cityscape and High-Rise Buildings Based on the 2020–2021 Composition Study of Szczecin. Krakow: Teka Komisji Urbanistyki i Architektury Oddziału Polskiej Akademii Nauk w Krakowie. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazaleheniya, Ismaeel, and Ayten Özsava Akçay. 2023. The Impact of Tall Buildings within the Existing and Historical Urban Environment. NEU Journal of Faculty of Architecture 4: 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilinsky, Alberta. 1951. Perceived size and distance in Visual Space. Psychology Revue 58: 460–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwiazdowska, Małgorzata. 2016. Ochrona i Konserwacja Zabytków Szczecina po 1945 Roku. Szczecin: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego. ISBN 9788379720873. [Google Scholar]

- Gyurkovich, Jacek. 1999. Znaczenie form Charakterystycznych w Ukształtowaniu i Percepcji Przestrzeni. Wybrane Zagadnienia Kompozycji w Architekturze i Urbanistyce. Krakow: Politechnika Krakowska. [Google Scholar]

- Ilgın, Hüseyin Emre, and Özlem Nur Aslantamer. 2024. Investigating Space Utilization in Skyscrapers Designed with Prismatic Form. Buildings 14: 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasiński, Artur. 2008. Znaczenie budynków wysokich i wysokościowych we współczesnej urbanistyce. Space and Form (Przestrzeń i Forma) 10: 233–44. [Google Scholar]

- Jasim, Sumayah Layij. 2020. High-Rise Dominants in the Urban Landscape of Baghdad: Architecture and Composition. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Architecture: Heritage, Traditions and Innovations (AHTI 2020). Amsterdam: Atlantis Press, pp. 276–85, ISSN 2352-5398. ISBN 978-6239-056-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimimoshaver, Mehrdad, Mastooreh Parsamanesh, Farshid Aram, and Amir Mosavi. 2021. The impact of the city skyline on pleasantness; state of the art and a case study. Heliyon 7: e07009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozińska, Bogdana. 2002. Rozwój Przestrzenny Szczecina od Początku XIX Wieku do II Wojny Światowej. Szczecin: Muzeum Narodowego w Szczecinie. ISBN 8388341103. [Google Scholar]

- Larcombe, Danica-Lea, Eddie van Etten, Alan Logan, Susuan L. Prescott, and Pierre Horwitz. 2019. High-Rise Apartments and Urban Mental Health—Historical and Contemporary Views. Challenges 10: 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Maosu, Fan Xue, Yijie Wu, and Anathony G. Yeh. 2022. A room with a view: Automatic assessment of window views for high-rise high-density areas using City Information Models and deep transfer learning. Landscape and Urban Planning 226: 104505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łopuch, Wojciech. 1999. Dzieje Architektoniczne Nowoczesnego Szczecina 1808–1945. Szczecin: Książnica Pomorska. [Google Scholar]

- Moor, Valery K., and Elena A. Erysheva. 2018. High-rise buildings in the structure of an urbanized landscape and their influence on the spatial composition and image of the city. E3S Web of Conferences 33: 01011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshaver, Merhard Karimi, Farshad Negintaji, and Hamid Reza Zeraatpisheh. 2015. The appearance of place identity in the urban landscape by using the natural factors (a case study of Yasouj). Journal of Architecture and Urbanism 39: 132–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]