Outside the Palaces: About Material Culture in the Almoravid Era

Abstract

1. Introduction: Brief Overview of the Almoravid Heritage Legacy

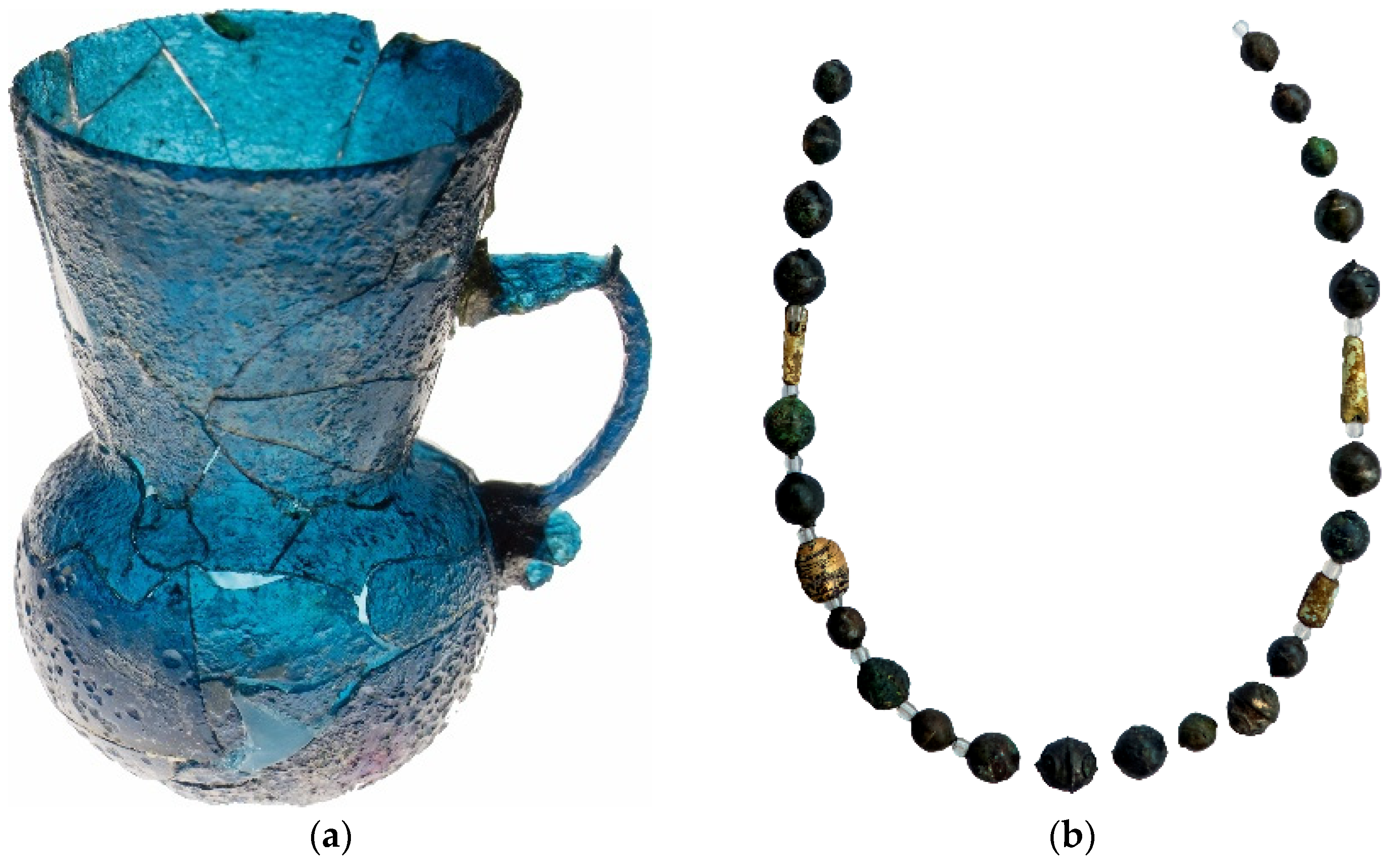

2. Archaeological Context: Albalat as Case Study

3. Ceramics and Everyday Artifacts

- a.

- Research Scope

- b.

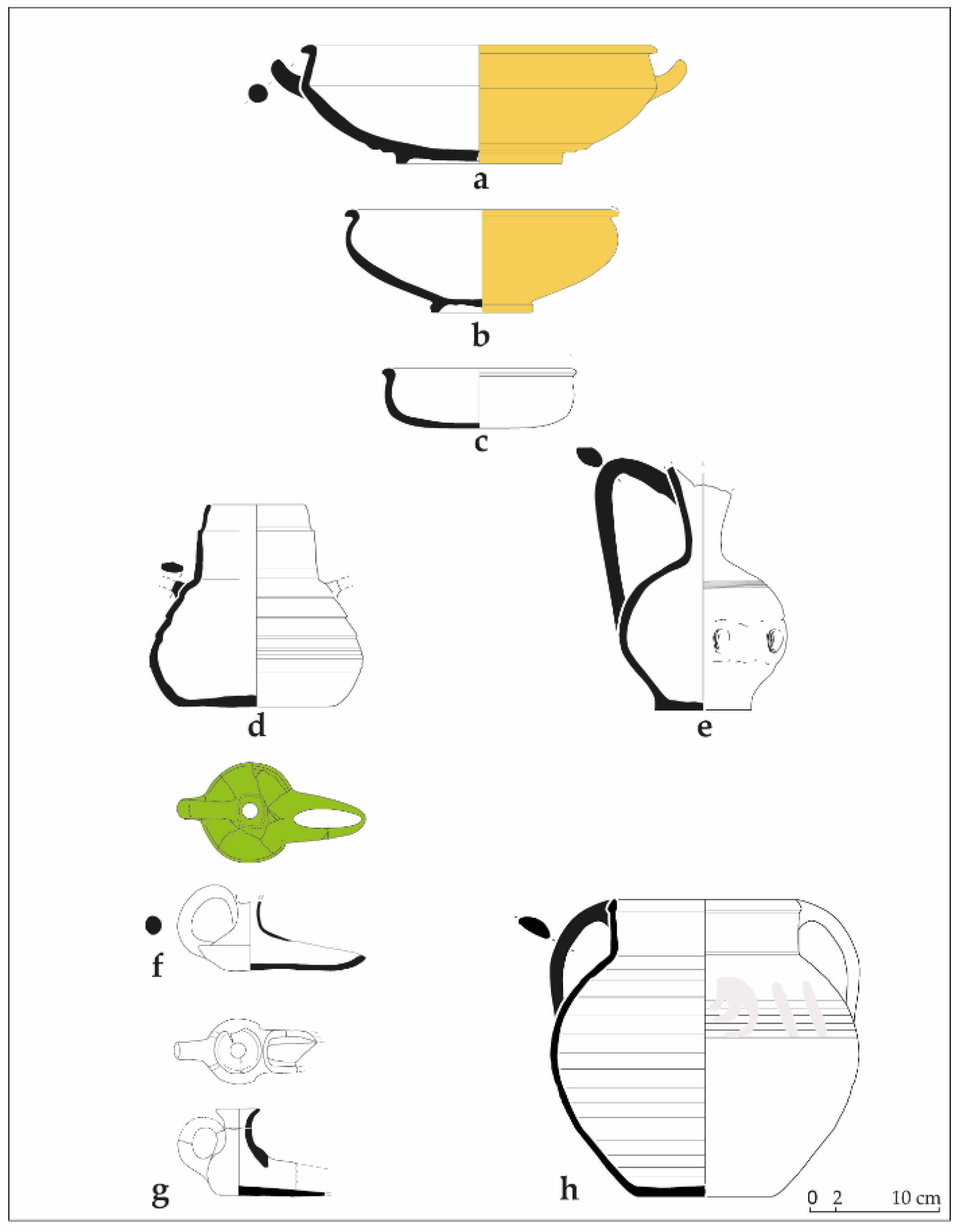

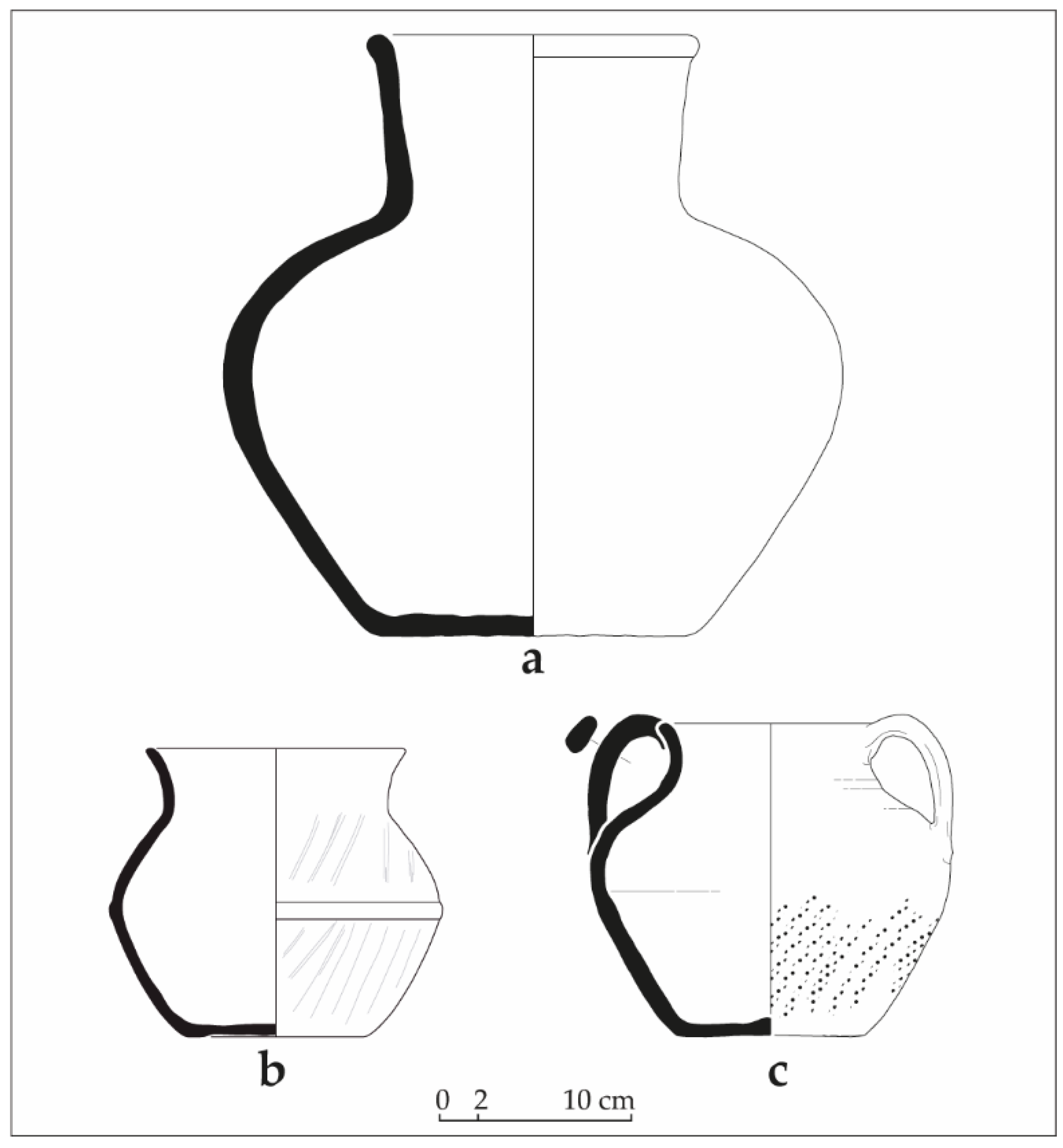

- Pottery Assemblages at Albalat

- c.

- Productions and Supply Networks

- d.

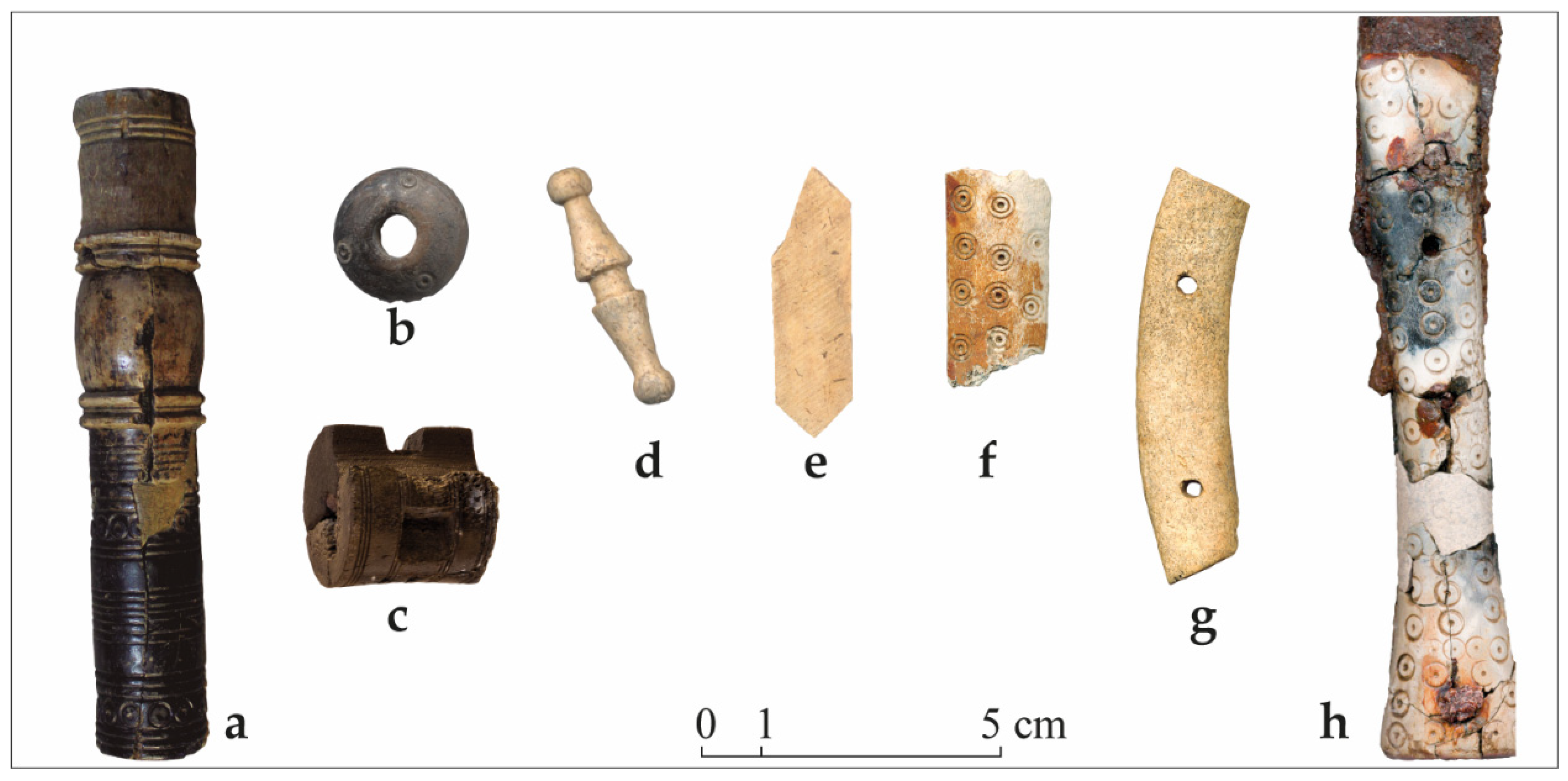

- Beyond Ceramics: The Case of Worked Bone and Antler

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | An overview in https://www.britannica.com/topic/Almoravids#ref83234 (accessed on 28 October 2024) and (Norris 1993, pp. 583–89). |

| 2 | Most of the 14C dating analyses conducted on various contexts associated with the last occupation phase (15 in total plus additional ones from older levels)—using charcoal, seeds, or, in one case, deer antlers—, indicate a BP date range of approximately 945–1010 ± 30 BP. In these cases, calibrated intervals range between AD 991–1166, such as S4-I/6188: AD 974–1150 (Beta–552449), S3-P/5395: AD 991–1154 (LY-18241), S3-C3/5026 AD 993–1153 (LY-16299) or S4-E2/6543: AD 1022–1159 (LY-19413 [GrM]). Obviously, these dates need to be compared with other data, especially in cases of discrepancies. In the case of building C-1, the dating of a burnt framework provided an interval of AD 887–1017 (Lyon-20332 [GrM]). However, the coins found in it—including eight dinars dated to 1118–1119 and a qirat discovered in the latrine minted between 1128 and 1138—indicate that the 14C dating is older than the last occupation phase. In this specific case, the possibility of an old wood effect or material reuse must be considered. |

| 3 | The remains are being conserved through conservation campaigns with the participation of students from the Higher Schools of Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Assets from Madrid and Pontevedra. |

| 4 | By Catherine Richarté (Inrap and Ciham UMR5648) and Claudio Capelli (university of Genoa—DISTAV), through to petrographic analysis. |

| 5 | By Some 3D artifacts models available at https://sketchfab.com/albalat (accessed on 28 October 2024); some photos in the freely accessible public repository https://www.nakala.fr/search/?q=keyword:%22Albalat%22 (accessed on 28 October 2024). |

| 6 | Charcoal remains associated with these bone plaques were studied by Mónica Ruiz Alonso, CCHS-CSIC. |

References

- Al-Balāṭ. Vida y Guerra en La frontera de Al-Andalus. 2017. Sophie, Gilotte, and Yasmina Cáceres Gutiérrez, eds. Cáceres: Diputación de Cáceres-Junta de Extremadura. Available online: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-01643193/file/catalogoexpo_ALBALAT_red.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Almagro, Antonio. 2020. Arquitectura religiosa almorávide. In Arqueología de Al-Andalus Almorávide. Edited by Rafael Azuar Ruíz. Alicante: MARQ, pp. 163–90. Available online: https://digital.csic.es/bitstream/10261/223019/3/almagro_2020ArqRAlmoravide.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Azuar Ruíz, Rafael. 1985. Castillo de la Torre Grossa (Jijona). Alicante: Diputación de Alicante-Museo Arqueológico Provincial. Available online: https://www.marqalicante.com/contenido/genericas/torregrossa.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Azuar Ruíz, Rafael. 2018. Les produccions ceràmiques de safes i platets a la Valéncia d’època taifa (segle XI). In L’Argila de la Mitja Lluna. La Cerámica Islámica a la Ciutat de València. 35 Anys D’arqueologia Urbana. Valencia: Museu d’Història de València, Ajuntament de València, pp. 121–47. [Google Scholar]

- Azuar Ruíz, Rafael, ed. 2020. Bronces andalusíes de época almorávide. In Arqueología de Al-Andalus Almorávide. Alicante: MARQ, pp. 139–59. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez García, José Javier. 2003. Cerámica almohade en la ciudad de Granada procedente de la excavación del Palacio del Almirante de Aragón. In Cerámicas Islámicas y Cristianas a Finales de la Edad Media. Influencias e Intercambios. Granada: Museo de Ceuta, pp. 141–67. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán Pinzón, José Manuel. 2005. Registros cerámicos de época taifa en Madina Labla (Niebla, Huelva): Un acercamiento tipológico. Huelva Arqueológica 12: 53–76. Available online: https://www.uhu.es/publicaciones/ojs/index.php/huelvahistoria/article/view/943 (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Benito de los Mozos, Federico. 2020. La plata almorávide y postalmorávide: El quirate. Manquso 7, Monographic issue. [Google Scholar]

- Bennison, Amira K. 2016. The Almoravid and Almohad Empires. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom, Jonathan, Ahmed Toufiq, Stefano Carboni, Jack Soultanian, Antoine M. Wilmering, Mark D. Minor, Andrew Zawacki, and El Mostafa Hbibi. 1998. The Minbar from the Kutubiyya Mosque. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Madrid: El Viso. Rabat: Ministry of Cultural Affairs Kingdom of Morocco. Available online: https://www.metmuseum.org/met-publications/the-minbar-from-the-kutubiyya-mosque (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Brisch, Klaus. 1966. Die Fenstergitter und Verwandte Ornamente der Hauptmoschee von Córdoba: Eine Untersuchung zur Spanisch-islamischen Ornamentik. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Bugalhão, Jacinta, Deolinda Folgado, Sofia Gomes, Maria João Sousa, Antónia Gonzalez Tinturé, Maria Isabel Dias, and Maria Isabel Prudêncio. 2008. La production céramique islamique à Lisbonne: Conclusions du projet de recherche POILIX. Paper presented at VIII Congreso Internacional de Cerámica Medieval en el Mediterráneo, Ciudad Real-Almagro, Spain, February 27–March 3; Ciudad Real-Almagro: Asociación Española de Arqueología Medieval, pp. 373–89. [Google Scholar]

- Buttard, Léa. 2021. Marcas gliptográficas en Albalat. Estado de la cuestión. Nuevas líneas de estudio de jóvenes investigadore en arqueología. In III Jornadas del Master en Arqueología. Granada: Universidad de Granada-Escuela Internacional de Posgrado, pp. 167–84. [Google Scholar]

- Buttard, Léa. 2023. Une historiographie des jeux de plateaux médiévaux, à partir du corpus d’Albalat (IXe–XIIIe siècles). L’Entre-Deux 20. Available online: https://www.lentre-deux.com/?b=288 (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Camacho Cruz, Cristina, and Rafael Valera Pérez. 2019. Espacios domésticos en los arrabales occidentales de Qurṭuba: Tipos de viviendas, análisis y reconstrucción. Antiquitas 31: 59–92. [Google Scholar]

- Canto García, Alberto. 2017. Tesorillo de dinares. In Al-Balāṭ. Vida y Guerra en la Frontera de Al-Andalus. Edited by Gilotte Sophie and Yasmina Cáceres Gutiérrez. Cáceres: Diputación De Cáceres-Junta De Extremadura, pp. 204–6. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona Ávila, Rafael, Dolores Luna Osuna, and Mª. Ángeles Jiménez Higueras. 2009. Aproximación a la producción cerámica de un horno de barras de época almohade de los alfares de Madinat Baguh (Priego de Córdoba). In VIII Congreso Internacional de Cerámica Medieval en el Mediterráneo. Ciudad Real: Asociación Española de Arqueología Medieval, pp. 1041–49. [Google Scholar]

- Catarino, Elena, Sandra Cavaco, Jaquelina Covaneiro, Isabel Cristina Fernandes, Ana Gomes, Susana Gómez, Maria José Gonçalves, Mathieu Grangé, Isabel Inácio, Gonçalo Lopes, and et al. 2012. La céramique islamique du Ġarb al-Andalus: Contextes socio-territoriaux et distribution. In Atti del IX Congresso Internazionale sulla Ceramica Medievale nel Mediterraneo. Edited by Sauro Gelichi. Venezia: All’Insegna del Giglio, pp. 429–41. [Google Scholar]

- Cavilla Sánchez-Molero, Francisco. 2005. La Cerámica Almohade de la Isla de Cádiz (Ŷazīrat Qādis). Cádiz: Universidad de Cádiz. [Google Scholar]

- Cavilla Sánchez-Molero, Francisco. 2007. La cerámica almohade del suroeste peninsular: Producciones estandarizadas. In La Cerámica en Entornos Urbanos y Rurales en el Mediterráneo Medieval. Edited by Alberto García and Fernando Villada. Granada: Museo de Ceuta, pp. 403–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cavilla Sánchez-Molero, Francisco. 2008. Cerámicas musulmanas procedentes de la posada del Mesón: Aproximación a la cerámica de época Taifas de Cádiz. In Estudios Sobre Patrimonio, Cultura y Ciencia Medievales. Cadiz: Agrija Ediciones, vol. 9/10, pp. 55–84. [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres Gutiérrez, Yasmina, and Sophie Gilotte. 2021. Entre Fogones Almorávides: Un conjunto excepcional del s. XII. In Actas del VI Congreso de Arqueología Medieval (España-Portugal). Ciudad Real: Asociación Española de Arqueología Medieval, pp. 503–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres Gutiérrez, Yasmina, Claudio Capelli, Nicolas Garnier, Sophie Gilotte, Jorge De Juan Ares, and Catherine Richarté. 2016. Les ḫâbiyat-s (jarres) d’Albalat (1ère m. XIIe siècle, Estrémadure). Vers une approche pluridisciplinaire. In Actes Du 1er Congrès International Thématique De L’AIECM3. Jarres et Grands Contenants Entre Moyen Âge et Epoque Moderne. Montpellier: AIECM3, pp. 311–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cáceres Gutiérrez, Yasmina, Sophie Gilotte, Catherine Richarté, and Jorge De Juan Ares. 2021. Les précurseurs des céramiques almohades. Décors estampés, impressions et motifs plastiques d’époque Almoravide à Albalat (Cáceres, Espagne). In 12th Congress Aiecm3 on Medieval & Modern Period Mediterranean Ceramics. Proceedings. Edited by Platón Petridis, Anastasia G. Yangaki, Nikos Liaros and Elli-Evangelia Bia. Athens: National Hellenic Research Foundation, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, vol. 3, pp. 681–88. [Google Scholar]

- Clapés Salmoral, Rafael. 2019. La formación y evolución del paisaje suburbano en época islámica: Un ejemplo en el arrabal occidental de la capital omeya de al-Andalus (Córdoba). Arqueología y Territorio Medieval 26: 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constable, Olivia R. 1994. Trade and Traders in Muslim Spain: The Commercial Realignment of the Iberian Peninsula, 900–1500. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cressier, Patrice. 2020. Arqueología del Magreb almorávide. Elementos de bibliografía. In Arqueología de Al-Andalus Almorávide. Edited by Rafael Azuar Ruíz. Alicante: MARQ, pp. 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Cressier, Patrice, and Sophie Gilotte. Forthcoming. Pour une archéologie des Almoravides (Al-Andalus-Maghreb). In Renouveler Al-Andalus. Les frontières de Philippe Sénac. Edited by Carlos Laliéna and Sébastien Gasc. Toulouse: Presses Universitaires du Midi.

- El Khammar, Abdeltif. 2006. Le mobilier des mosquées médiévales du Maroc d’après les sources textuelles. Al-Andalus Magreb 13: 79–94. Available online: https://revistas.uca.es/index.php/aam/article/view/7614 (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- El Khammar, Abdeltif. 2018. Les mosquées du Maroc: Bilan et perspectives de recherches. In L’archéologie au Maroc Entre le Texte Historique et L’enquête de Terrain. Actes du premier Congrès National sur le Patrimoine Culturel Marocain. Edited by Mohamed Belatik, Alaoui Mohamed Kbiri, Samir Kafas, Ahmed Saleh Ettahiri and Abdellah Fili. Rabat: ALINSAP, pp. 172–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ettahiri, Ahmed S. 2014. À l’aube de la ville de Fès. Découvertes sous la mosquée al-quarawiyin. Dossiers d’Archéologie 365: 42–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ettahiri, Ahmed S., Abdallah Fili, and Jean-Pierre Van Staëvel. 2012. Nouvelles recherches archéologiques sur la période islamique au Maroc: Fès, Aghmat et Îgîlîz. In Villa 4. Histoire et Archéologie de l’Occident Musulman (VIIe-XVe Siècle): Al-Andalus, Maghreb, Sicile. Edited by Philippe Sénac. Toulouse: CNRS—Université Toulouse-Le Mirail, pp. 157–81. [Google Scholar]

- Fili, Abdallah, Ahmed S. Ettahiri, Jean-Pierre Van Staëvel, and Ihssane Serrat. 2020. Première approche typologique de la céramique protoalmohade d’Igīlīz (Maroc). Bulletin d’Archéologie Marocaine 25: 101–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fili, Abdallah, and Ihssane Serrat. 2020. Céramique médiévale de Fès. In Etudes et Travaux d’archeologie Marocaine. Kuala Lumpur: INSAP, vol. 12, pp. 193–217. [Google Scholar]

- Fili, Abdallah, Ronald Messier, and Chloé Capel. 2018. Aghmat, la découverte de la première capitale almoravide. In Le Patrimoine Culturel Marocain, la Croisée des chemins ed.; Paris: Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication, pp. 256–77. [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes Santos, María del Camino. 2009. El siglo XII en Cercadilla a través de los materiales cerámicos. Avance de resultados. In VIII Congreso Internacional de Cerámica Medieval en el Mediterráneo. Ciudad Real-Almagro: Asociación Española de Arqueología Medieval, pp. 327–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes Santos, María del Camino. 2010. La Cerámica Medieval de Cercadilla, Córdoba. Decoración, tipo, función. Junta de Andalucía: Consejería de Cultura, pp. 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Galán y Galindo, Ángel. 2005. Marfiles Medievales del Islam: Catálogo de Piezas. Córdoba: Cajasur. [Google Scholar]

- García Porras, Alberto. 2016. La producción de cerámica en Almería entre los siglos X y XII. In Cuando Almería era Almariyya: Mil Años en la Historia de un Reino. Edited by Lorenzo Cara. Almeria: Instituto de Estudios Almerienses, pp. 273–92. [Google Scholar]

- García Villanueva, María Isabel, and Josefa Pascual Pacheco. 2018. Ceràmica de l’etapa nord-africana a València. In L’argila de la Mitja Lluna: La Ceràmica Islàmica a la Ciutat de València: 35 Anys D’arqueologia Urbana. Valencia: Museu d’Història de València, pp. 195–232. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido García, José Antonio, and Sophie Gilotte. 2021. Albalat: Posibilidades y limitaciones de los análisis faunísticos para la caracterización de los últimos momentos de un asentamiento fronterizo andalusí. In L’alimentation en Méditerranée Occidentale aux Epoques Antique et Médiévale. Archéologie, Bioarchéologie et Histoire. Edited by Marianne Brisville, Audrey Renaud and Núria Rovira. BiAMA 29. Aix-en-Provence: Presses Universitaires de Provence, pp. 111–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, Rui Filipe, and Rafael Santiago. 2024. As cerâmicas almorávidas do Castelo de Sesimbra. Dinâmicas de poder e ocupação do território Gil. In Terra, Pedras e Cacos do Garb al-Andalus. Edited by Jacinta Bugalhão, Isabel Cristina Fernandes, Susana Gómez-Martínez, Helena Catarino, Sandra Cavaco, Jaquelina Covaneiro, Ana Sofia Gomes, Maria José Gonçalves, Isabel Inácio, Marco Liberato and et al. Trabalhos de Arqueologia 57. Lisboa: Património Cultural, I.P., pp. 193–204. [Google Scholar]

- Gilotte, Sophie. 2011. Aux Marges d’al-Andalus. Peuplement et Habitat en Estremadure Centre-Orientale (VIIIe–XIIIe siècles). coll. Humanoria 356. Helsinski: Academia Scientiarum Fennica. [Google Scholar]

- Gilotte, Sophie. 2019. Albalat (Prov. Cáceres): La dernière bataille. Traces archéologiques du siège de 1142. In Da Conquista De Lisboa À Conquista De Alcácer: Definição E Dinâmicas De Um Território De Fronteira. Edited by Isabel Cristina F. Fernandes and Maria João V. Branco. Palmela: Edições Colibri, pp. 81–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gilotte, Sophie. 2020a. ¿En La Mano De Dios? La cuestión del poder en una aglomeración de la frontera almorávide: Puntualizaciones arqueológicas desde Albalat (Cáceres). In Poder y Comunidades Campesinas en el Islam Occidental (Siglos XII–XV). Edited by Alberto García Porras and Adela Fábregas García. Granada: Universidad de Granada, pp. 171–98. Available online: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-02981042v1/document (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Gilotte, Sophie. 2020b. Pinceladas sobre la arquitectura y el urbanismo de un pequeño centro urbano fronterizo en época almorávide. Albalat (Cáceres). In Arqueología de Al-Andalus Almorávide. Edited by Rafael Azuar Ruíz. Alicante: MARQ, pp. 211–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gilotte, Sophie, and Xoan Moreno Paredes. 2022. Albalat (Romangordo, Cáceres): Una década de trabajos en una fortificación almorávide del valle medio del río Tajo. In Actualidad de la Investigación Arqueológica en España IV (2021–2022). Conferencias Impartidas en el Museo Arqueológico Nacional; Madrid: Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, pp. 201–20. Available online: https://www.man.es/man/dam/jcr:aeb8fd55-0c60-4362-be05-62ae8acca2b3/2022-aae-ciclo-iv.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Gilotte, Sophie, and Yasmina Cáceres Gutiérrez. 2024. Las pesas de red cerámicas del siglo XII del yacimiento de Albalat (Cáceres). In XIII Congreso Internacional Sobre Cerámica Medieval y Moderna en el Mediterráneo. Edited by Alberto García, Miguel Busto, Laura Martín and María José Peregrina. Madrid: La Ergástula, pp. 141–44. [Google Scholar]

- Gilotte, Sophie, Léa Buttard, Yasmina Cáceres Gutiérrez, Alberto Llamas Herrero, and Alba González Gil. 2023. Albalat: Un édifice singulier du secteur nord. Bulletin Archéologique des Écoles Françaises à L’étranger [Online]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilotte, Sophie, Pauline De Keukelaere, and José Antonio Garrido García. 2021a. Un taller de materia ósea en la frontera de Al-Andalus. In Actas del VI Congreso de Arqueología Medieval (España-Portugal). Edited by Manuel Retuerce Velasco. Ciudad Real: Asociación Española de Arqueología Medieval, pp. 373–80. [Google Scholar]

- Gilotte, Sophie, Yasmina Cáceres, Catherine Richarté, Nicolas Garnier, and Claudio Capelli. 2024. Lo que cuentan los candiles: Una aproximación a la economía local de Albalat. Paper presented at XIV Congress AIECM3 on Medieval and Modern Period Mediterranean Ceramics, Ravenna, Italy, November 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gilotte, Sophie, Yasmina Cáceres Gutiérrez, and Jorge De Juan Ares. 2016. Un ajuar de época almorávide procedente de Albalat (Cáceres, Extremadura). In Proceedings of 10th International Congress on Medieval Pottery in the Mediterranean. Edited by Maria José Gonçalves and Susana Gómez Martínez. Silves: Edição Câmara Municipal de Silves, Mértola: Campo Arqueológico de Mértola, vol. 2, pp. 763–75. [Google Scholar]

- Gilotte, Sophie, Yasmina Cáceres Gutiérrez, Claudio Capelli, Nicolas Garnier, Jorge De Juan Ares, and Catherine Richarté. 2021b. A Remarkable Jar With Architectural Decoration: An Almohad Precedent? In 12th Congress Aiecm3 On Medieval & Modern Period Mediterranean Ceramics. Proceedings. Edited by Platón Petridis, Anastasia G. Yangaki, Nikos Liaros and Elli-Evangelia Bia. Athens: National Hellenic Research Foundation, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, vol. 2, pp. 841–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, Ana, Alexandra Gaspar, João Pimenta, António Valongo, Paula Pinto, Henrique Mendes, Susana Ribeiro, and Sandra Guerra. 2001. A cerâmica pintada de época medieval da Alcáçova do Castelo de S. Jorge. In Garb. Sitios Islamicos del Sur Peninsular; Edited by Manuel Lacerda, Miguel Soromenho, María Ramalho, María de Magalhaes and Carla Lopes. Lisboa-Mérida: Ministério da Cultura—Instituto Português do Património Arquitectónico e Arqueológico, Consejería de Cultura, pp. 119–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, Rosa Varela. 2003. Silves (Xelb), Uma Cidade do Gharb Al-Andalus: A Alcáçova. Trabalhos de Arqueologia 35. Lisboa: Instituto Portugués de Arqueologia. [Google Scholar]

- González Ballesteros, José Ángel, and María Ángeles Muñoz Espinosa. 2024. Análisis de los contextos cerámicos del recinto I del conjunto arqueológico de San Esteban (Murcia). In XIII Congreso Internacional sobre Cerámica Medieval y Moderna en el Mediterráneo. Edited by Alberto García, Miguel Busto, Laura Martín and María José Peregrina. Madrid: La Ergástula, pp. 651–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Martínez, Susana. 2014a. Cerámica Islámica de Mértola. Mertola: Museu de Mertola—Campo Arqueológico de Mértola. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Martínez, Susana. 2014b. Las cerámicas taifas del suroeste peninsular. In Bataliús III: Estudios Sobre el Reino Aftasí. Edited by Juan Zozaya Stabel-Hansen and Guillermo S. Kurtz Schaefer. Badajoz: Gobierno de Extremadura, Consejería de Educación y Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Martínez, Susana. 2018. La cultura material del Garb al-Andalus en el siglo XI. In Ṭawā’if. Historia y Arqueología de los Reinos de Taifas (Siglo XI). Edited by Bilal Sarr. Granada: Alhulia, pp. 139–76. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Martínez, Susana, Ligia Rafael, and Santiago Macias. 2010. Habitat e utensílios na Mértola almóada. Cuadernos de Madīnat al-Zahrā 7: 175–95. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Martínez, Susana, Maria José Gonçalves, Isabel Inácio, Constança Dos Santos, Catarina Coelho, Marco Liberato, Ana Gomes, Jacinta Burgalhao, Helena Catarino, Sandra Cavaco, and et al. 2016. A cidade e o seu territorio no Gharb al-Ándalus a través da cerámica. In Proceedings of 10th International Congress on Medieval Pottery in the Mediterranean. Edited by Maria José Gonçalves and Susana Gómez Martínez. Silves: Edição Câmara Municipal de Silves, Mértola: Campo Arqueológico de Mértola, vol. 1, pp. 19–50. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.26/18420 (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Gutiérrez González, Francisco Javier, and Arancha Mendívil Uceda. 2023. Producciones cerámicas islámicas procedentes de Madīnat Saraqusta. Saldvie 23: 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibn Ḥawqal, Abū al-Qāsim Muḥammad. 1971. Kitāb Ṣūrat Al-Arḍ. In Configuración del mundo, fragmentos alusivos al Magreb y España, Textos Medievales. Translated by María José Romani Suay. Valence: Anubar, vol. 26. [Google Scholar]

- Iñíguez Sánchez, María del Carmen. 2024. La organización del espacio productivo en los alfares de época islámica en Málaga. In XIII Congreso Internacional Sobre Cerámica Medieval y Moderna en el Mediterráneo. Edited by Alberto García, Miguel Busto, Laura Martín and María José Peregrina. Madrid: La Ergástula, pp. 219–26. [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo Benito, Ricardo. 1999. Vascos, la Vida Cotidiana en una Ciudad Fronteriza de Al-Andalus. Colección “Imágenes y palabras” 28. Toledo: Junta de Comunidades de Castilla La Mancha. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/97706987/Vascos_La_Vida_cotidiana_en_una_ciudad_fronteriza_de_al_Andalus_Catalogo_de_la_Exposici%C3%B3n_Exhibition_catalogue_1999_ (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Jiménez Castillo, Pedro, and Julio Navarro Palazón. 1997. Platería 14. Sobre Cuatro Casas Andalusíes y su Evolución (Siglos X–XIII). Murcia: Centro de Estudios Árabes y Arqueológicos “Ibn Arabí”. Available online: https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/14413 (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Jiménez Castillo, Pedro, José Luis Simón García, and José María Moreno Narganes. 2024. Las producciones cerámicas de La Graja (Higueruela, Albacete). Una alquería andalusí del s. XI. In XIII Congreso Internacional Sobre Cerámica Medieval y Moderna en el Mediterráneo. Edited by Alberto García, Miguel Busto, Laura Martín and María José Peregrina. Madrid: La Ergástula, pp. 439–50. [Google Scholar]

- Labarta, Ana, Gilotte Sophie, Belén Sanmartin Freitas, Ignacio Montero Ruiz, and Óscar García Vuelta. 2023. Collar de época almorávide hallado en Albalat. Revista De Estudios Extremeños LXXVII-3: 1183–224. Available online: https://www.dip-badajoz.es/cultura/ceex/reex_digital/reex_LXXVII/2021/T.%20LXXVII%20n.%203%202021%20sept.-dic/00124459.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Lagardère, Vincent. 1989. Les Almoravides. Paris: L’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Lévi-Provençal, Évariste. 1957. La fondation de Marrakech. In Mélanges d’Histoire et d’Archéologie de L’Occident Musulman. Hommage à Georges Marçais. Alger: Imprimerie officielle, vol. 2, pp. 117–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lintz, Yannick, Claire Déléry, Bulle Tuil Leonetti, Louise Carlat, and Rosène Declémenti. 2014. Le Maroc Médiéval. Un Empire de l’Afrique à l’Espagne. Edited by Yannick Lintz, Claire Déléry and Bulle Tuil. Paris: Musée du Louvre—Hazan. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, Virgílio, Susana Gómez Martínez, and Lígia Rafael. 2012. Arrabalde Ribeirinho. Museu de Mértola. Mértola: Campo Arqueológico de Mértola. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos Cobaleda, María. 2015. Los Almorávides: Arquitectura de un Imperio. Grenada: University of Grenada. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos Cobaleda, María, dir. 2018a. Al-Murābiṭūn (Los Almorávides): Un Imperio Islámico Occidental. Estudios en Memoria del Profesor Henri Terrasse. Grenade: Junta de Andalucía. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos Cobaleda, María. 2018b. Los almorávides y el fin de las taifas. Continuidad y/o ruptura. In Ṭawā‘if. Historia y Arqueología de los Reinos Taifas. Edited by Bilal Sarr. Grenada: Alhulia, pp. 683–702. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos Cobaleda, María, and Dolores Villalba Sola. 2019. Fronteras entre el arte almorávide y Almohade: Oposición Y Complementariedad. In Da Conquista De Lisboa À Conquista De Alcácer (1147–1217). Definições E Dinâmicas De Um Território De Fronteira. Edited by Isabel Cristina F. Fernandes and Maria João V. Branco. Lisbon: Edições Colibri, pp. 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Núñez, Maria Antonia. 2020. Al-Andalus durante el período almorávide a través de la documentación epigráfica. In Arqueología de Al-Andalus Almorávide. Edited by Rafael Azuar Ruíz. Alicante: MARQ, pp. 61–77. [Google Scholar]

- Melero García, Francisco. 2012. El ataifor estampillado andalusí. A propósito del conjunto documentado en el vertedero medieval de Cartama (Málaga). Debates de Arqueologia Medieval 2: 109–28. [Google Scholar]

- Meunié, Jacques, Henri Terrasse, and Gaston Deverdun. 1957. Nouvelles Recherches Archéologiques à Marrakech. Publications de l’Institut des Hautes Études Marocaines LXII. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Narganes, Jose María. 2019. Tejiendo en casa: Las actividades de hilado-tejido en el espacio doméstico de Al-Andalus (ss. XII–XIII). In VII Congreso de Arqueología Medieval (España-Portugal). Edited by Susana Gómez, Miguel Ángel Hervás and Manuel Melero. Ciudad Real: Asociación Española de Arqueología Medieval, pp. 429–33. [Google Scholar]

- Motos Guirao, Encarnación. 2003. La cerámica almohade al sur de Jaén. In Cerámicas Islámicas y Cristianas a Finales de la Edad Media. Influencias e Intercambios. Granada: Museo de Ceuta, pp. 83–140. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Palazón, Julio, and Alfonso Robles Fernández. 1996. Liétor: Formas de Vida Rurales en Šarq Al-Andalus a Través de una Ocultación de los Siglos X–XI. Miscelánea Medieval Murciana. Murcia: Centro de Estudios Árabes y Arqueológicos Ibn Arabi. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Palazón, Julio, and Pedro Pedro Jiménez Castillo. 2007. Siyasa. Estudio Arqueológico del Desploblado Andalusí (ss. XI–XIII). Murcia: El Legado Andalusí. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Harry T. 1993. Al-Murābiṭūn. In Encyclopaedia of Islam 2 (EI2). Leiden: J. Brill, vol. 7, pp. 583–89. [Google Scholar]

- Orives. La Joyería de Filigrana Cacereña. 2022. Cáceres: Junta de Extremadura-Museo de Cáceres. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/124629651/Orives_La_joyer%C3%ADa_de_filigrana_cacere%C3%B1a (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Partearroyo Lacaba, Cristina, and Miriam Ali de Unzaga. 2020. Tejidos del periodo almorávide: Hallazgos recientes, revisión y nuevos datos. In Arqueología de Al-Andalus Almorávide. Edited by Rafael Azuar Ruíz. Alicante: MARQ, pp. 93–138. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual Pacheco, Josefa, Pau Armengol Machí, María Isabel García Villanueva, Lourdes Roca, and Enrique Ruiz. 2009. La producción cerámica almohade en la ciudad de Valencia. El alfar de la calle Sagunto. In VIII Congreso Internacional de Cerámica Medieval en el Mediterráneo. Edited by Juan Zozaya, Manuel Retuerce, Miguel Ángel Hervás and Antonio de Juan. Ciudad Real-Almagro: Asociación Española de Arqueología Medieval, pp. 355–71. [Google Scholar]

- Peña Martín, Salvador, and Miguel Vega Martín. 2006. Rebuilding the contexts of the Andalusi epigraphic legacy: ‘The Friend of God’ in the Almoravid numismatic discourse. TRANS: Revista de Traductología 3: 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Asensio, Manuel, and Pedro Jiménez Castillo. 2018. El ajuar cerámico almorávide en Sarq Al-Andalus. Al-murābitūn (los almorávides). In Un Imperio Islámico Occidental: Estudios en Memoria del Profesor Henri Terrasse. Edited by María Marcos Cobaleda. Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y el Generalife, pp. 161–221. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Asensio, Manuel, and Vicent Estall i Poles. 2012. Primera aproximación a la cerámica dorada islámica hallada en la excavación arqueológica de la Alcazaba de Onda. In I Congreso Internacional Red Europea de Museos de Arte Islámico. Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife-Victoria & Albert Museum, pp. 189–218. Available online: https://www.alhambra-patronato.es/publicaciones/no-1-i-congreso-internacional-red-europea-de-museos-de-arte-islamico (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Pérez Martín, Irene, and Elena Salinas Pleguezuelo. 2025. La vida cotidiana de Al-Mariyya en el siglo XII a través de su ajuar cerámico. Arqueología y Territorio Medieval 32: 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retuerce Velasco, Manuel. 1998. La Cerámica Andalusí de la Meseta. Madrid: CRAN, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Retuerce Velasco, Manuel. 2024. Cerámica almohade. In Calatrava la Vieja I. El fin de la Presencia Almohade en Calatrava y su paso al reino de Castilla Según las Fuentes Escritas y Arqueológicas. La Excavación Arqueológica de la Torre n° 27 de la Muralla. Edited by Manuel Retuerce Velasco. Madrid: Opera Prima, pp. 144–274. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Aguilera, Ángel. 1999. Estudio de las producciones postcalifales del alfar de la Casa de los Tiros (Granada). Siglos XI-XII. Arqueologia Medieval 6: 101–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ros, Jérôme, José Antonio Garrido Garcíam, Mónica Ruiz Alonso, and Sophie Gilotte. 2018. Bioarchaeological results from the House 1 at Albalat (Romangordo, Extremadura, Spain): Agriculture, Livestock and Environment at the Margin of al-Andalus. Journal of Islamic Archaeology 5: 71–102. Available online: https://journal.equinoxpub.com/JIA/issue/view/49 (accessed on 28 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Ros, Jérôme, Sophie Gilotte, Nicolás Losilla, and Thierry Pastor. 2024. Dieta vegetal en al-Andalus: El aporte del estudio de dos pozos Negros en Albalat (Extremadura). In Actas del VII Congreso de Arqueología Medieval. Sigüenza: Asociación Española de Arqueología Medieval, pp. 115–22. [Google Scholar]

- Rosselló Bordoy, Guillermo. 2009. El concepto de la cerámica medieval: Entre Madîna Ilbîra y Hisn al-‘Araq. In Actas del VIII Congreso Internacional de Cerámica Medieval. Ciudad Real: Asociación Española de Arqueología Medieval, vol. 2, pp. 703–10. [Google Scholar]

- Roux, Corinne, and María F. Guerra. 2000. La monnaie almoravide: De l’Affrique à l’Espagne. Revue d’archéométrie 24: 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salado Escaño, Juan Bautista, and Ana Arancibia Román. 2003. Málaga durante los imperios norteafricanos: Los almorávides y almohades, siglos XI–XIII. Mainake 25: 69–102. Available online: https://www.cedma.es/catalogo/mainake.php?ref=13015 (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Salinas Pleguezuelo, María Elena. 2012. La Cerámica Islámica de Madinat Qurtuba de 1031 a 1236. Cronotipología y Centros de Producción. Ph.D. dissertation/thesis, Universidad of Córdoba, Córdoba, Spain. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10396/7830 (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Salinas Pleguezuelo, María Elena, and María del Carmen Méndez Santiesteban. 2008. El ajuar doméstico de una casa almohade del siglo XII en Córdoba. Anejos de Anales de Arqueología Cordobesa 1: 265–78. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas Pleguezuelo, María Elena, Belén Alemán Ochoterena, and Irene Pérez Martín. 2024. Arquitectura doméstica y cultura material en la Almería islámica del siglo XII. In VII Congreso de Arqueología Medieval (España-Portugal). Edited by Susana Gómez, Miguel Ángel Hervás and Manuel Melero. Ciudad Real: Asociación Española de Arqueología Medieval, pp. 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Sanabria Murillo, Diego. 2022. La cerámica musulmana del cerro del Castillo (Capilla, Badajoz). NORBA, Revista de Historia 34–35: 11–52. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=9721993 (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Sauvaget, Jean. 1949. Sur le minbar de la Kutubīya de Marrakech. Hespéris 36: 313–19. [Google Scholar]

- Serrat, Ihssane. 2024. La céramique de l’habitat d’Igiliz-n-Warghen (Anti-Atlas, Maroc): Dynamique de production et d’échanges durant le xiie siècle. Afrique: Archéologie & Arts 20: 109–10. [Google Scholar]

- Serrat, Ihssane, Ahmed Saleh Ettahiri, and Abdallah Fili. 2019. La céramique glaçurée du niveau almoravide de la mosquée al-Ḳarawiyyīn de Fès: Étude typologique. Bulletin D’archéologie Marocaine 24: 111–26. [Google Scholar]

- Silva Santa-Cruz, Noelia. 2013. La Eboraria Andalusí del Califato Omeya a la Granada Nazarí. BAR International Series 2522; Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Simón García, José Luis, José María Moreno Narganes, and Pedro Jimenez Castillo. 2024. Castellar de Meca Revisited. The Islamic Occupation (9th–12th Centuries). Madrider Mitteilungen 65: 326–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, Cláudio. 1988. Mértola Almoravide et Almohade. Mértola: Ministère des Affaires Culturelles du Royaume du Maroc - Câmara Municipal de Mértola. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, Cláudio, and Santiago Macias. 1998. O Legado Islâmico em Portugal. Lisbon: Fundação círculo de leitores. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés, Fernando, Susana Díaz del Diego, Francisco Javier Duran Castellano, and Esther Sordo Romero. 2001. La cerámica andalusí de la ciudad de Badajoz. Primer período (siglos IX–XII), según los trabajos en el antiguo Hospital Militar y en el área del aparcamiento de la c/de Montesinos. In Garb. Sitios Islámicos del sur Peninsular; Edited by Manuel Lacerda, Miguel Soromenho, María Ramalho, María de Magalhaes and Carla Lopes. Lisbon and Merida: Ministério da Cultura—Instituto Português do Património Arquitectónico e Arqueológico, Consejería de Cultura, pp. 377–99. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas Calderón, José. 2021. La cerámica estampillada almohade del albacar de Trujillo. Alcántara 91: 87–107. Available online: https://archivo.dip-caceres.es/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/06-091-06.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Vera Reina, Manuel, and Pina López Torres. 2009. La producción trianera (Sevilla) en época almohade. In VIII Congreso Internacional de Cerámica Medieval en el Mediterráneo. Edited by Juan Zozaya, Manuel Retuerce, Miguel Ángel Hervás and Antonio de Juan. Ciudad Real-Almagro: Asociación Española de Arqueología Medieval, pp. 429–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zapata Parra, José Antonio, and María Isabel Muñoz Sandoval. 2006. Estudio de un ajuar cerámico almorávide hallado en Lorca. Alberca 4: 95–113. Available online: http://www.amigosdelmuseoarqueologicodelorca.com/alberca/pdf/alberca4/articulo6.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Zozaya, Juan. 2007. Los candiles de piquera. In Tierras del Olivo. El Olivo en la Historia. Granada: Junta de Andalucía, Fundación El Legado Andalusí, pp. 125–35. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gilotte, S.; Cáceres Gutiérrez, Y. Outside the Palaces: About Material Culture in the Almoravid Era. Arts 2025, 14, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14020026

Gilotte S, Cáceres Gutiérrez Y. Outside the Palaces: About Material Culture in the Almoravid Era. Arts. 2025; 14(2):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14020026

Chicago/Turabian StyleGilotte, Sophie, and Yasmina Cáceres Gutiérrez. 2025. "Outside the Palaces: About Material Culture in the Almoravid Era" Arts 14, no. 2: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14020026

APA StyleGilotte, S., & Cáceres Gutiérrez, Y. (2025). Outside the Palaces: About Material Culture in the Almoravid Era. Arts, 14(2), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts14020026