Abstract

Humans have been monitoring light from the solar system to tell the time and plan activities since Time Immemorial. This is an analysis regarding why Native Americans living in the upper Colorado River Basin chose to monitor light from the western sky using a light marker that is approximately 4.02 miles long and 2.07 miles wide, or approximately 12.7 square miles. The light catching is accomplished in a massive geoscape by carefully calibrated and engineered stone markers. The scale of this light marker and its functional topographic components makes it one of the biggest and most elaborate in North America. As such, it is a World-Balancing geosite. This analysis is based on 522 ethnographic interviews, with 316 that were conducted during the Canyonlands National Park (Canyonlands NP) ethnographic study and 206 that were conducted during two BLM ethnographic studies. The findings are situated among tribally approved ethnographic findings from more than a dozen other studies conducted by the authors.

1. Introduction

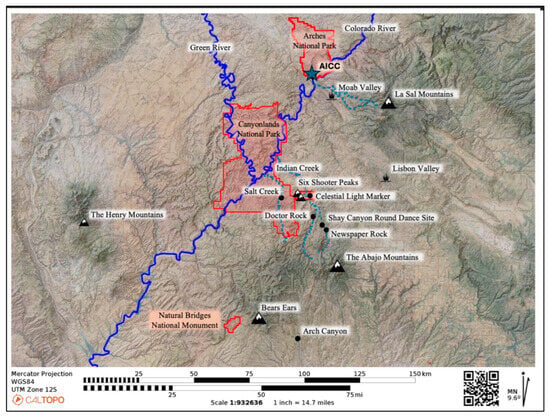

This analysis of places in the western United States of America is centered in the southeastern state of Utah near Canyonlands National Park and the Colorado River and in the state of Colorado near Hovenweep National Monument, Mesa Verde National Park, and along the San Juan River (Figure 1). It is an ethnographic analysis of a Celestial Light Marker that spans a culturally recognized spiritual hydrological system called Indian Creek, which is recognized by Native Americans as being traditionally used by them for a variety of ceremonies. The term Celestial Light Marker is used because it is operationally defined as any light from the solar system that can be marked at this location. Terms that are not used, such as solar light and solar calendar, often imply exclusive measures of daytime used to mark times of the year; however, importantly, this is but one of the kinds of light marked here.

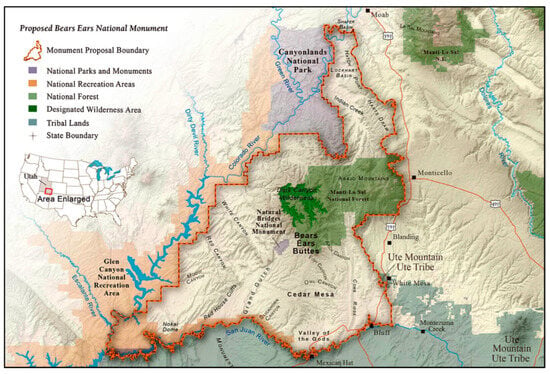

Figure 1.

Indian Creek study area in the highly politicized Bears Ears National Monument, outlined in red (Bears Ears Intertribal Coalition 2025).

The marker and hydrological system have been interpreted by various Native American tribal representatives in our ethnographic studies, but this is the first integration and situation of those findings. This analysis is also carried out using four other light marker studies that have been conducted by the authors. The analysis uses the dominant interpretive cultural and climate framework of the region called the Mesa Verde World.

This is an engineered Celestial Light Marker; as such, it represents a kind of rock art. Engineered rock art platforms have been documented in many areas but are rare in the western US. The reasons for engineering this light marker in this hydrological system thus requires an interpretation of a much broader cultural landscape and history. Given that the region surrounding the study site is well documented and interpreted as a component of the Mesa Verde World, the rock art can be interpreted in terms of (a) why it was placed at this location and (b) when it was primarily used. This analysis suggests that it was a World-Balancing geosite.

The scholars associated with the findings used for this analysis have been involved in more than 60 ethnographic studies with more than 100 participating American Indian Tribes and Pueblos. These scholars confirm their commitment to conducting these studies in order to more fully protect the heritage objects, places, and history of the participating contemporary peoples. As outsiders in space and time, we scholars stipulate that a full understanding of these heritage issues cannot and perhaps should not be known; however, the broad outlines of their purpose and contemporary importance as ancestral heritage is essential for establishing culturally appropriate and sustainable preservation methods, visitor interpretations, and land management policies (Stoffle et al. 2020). Today, most Native American heritage lands involved in this analysis are managed by USA federal agencies whose lands surround the Indian Creek study area (Figure 1).

Nothing is more culturally sensitive than the terms used to describe these heritage objects, places, and history. The object of this analysis is thus titled the Celestial Light Marker, which is used instead of solar marker, solar calendar, or other terms that imply more specific functions, times used, and potential cultural affiliations (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

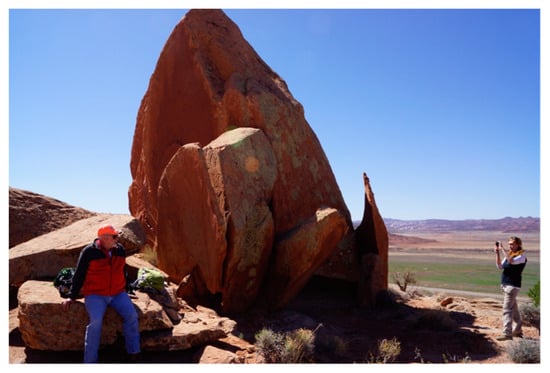

Figure 2.

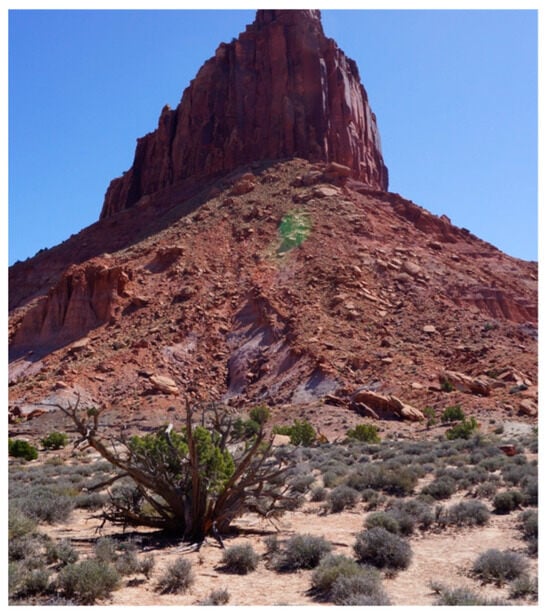

The peaks framing the Celestial Light Marker from dance grounds (source: Stoffle).

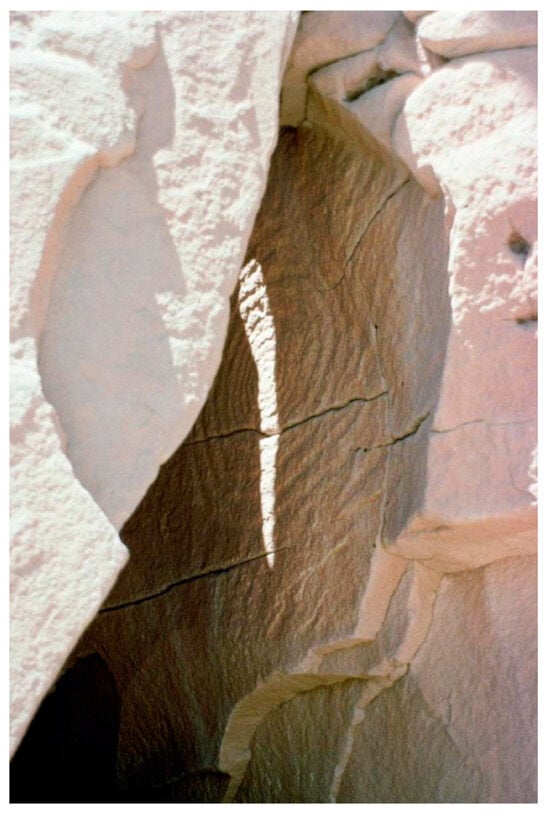

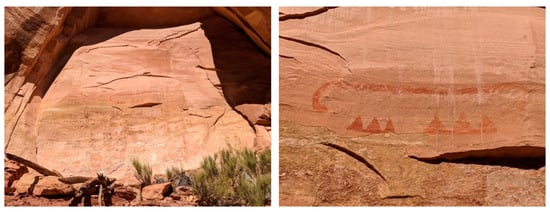

Figure 3.

Engineered stone marker on a ledge above Indian Creek (source: Stoffle).

It is not known what kind of light the engineers intended to use in order to tell time using the stone marker and rock art. We do know that the light, however it was focused, landed directly on the nearby natural sandstone wall with many rock peckings. It is not known if the foundation rocks or the light marker changed in structure and function over thousands of years of ceremonial use. It is also not known whether or not the location of the rock art was modified by moving the stones to where they are now. Given the ancient roots of this geosite and the continual modification needed for the light marker to be accurate over long periods, it is assumed that some shifts in structure and location have occurred in the 40,000 years of Native use of this area.

Based on past ethnographic studies with Native American representatives conducted at similar places, in addition to this study, a few points can be surmised:

- Celestial specialists, including sky watchers (or the term astronomers) and light-marking engineers, were needed to produce this complex light marker and associated ceremonial areas.

- Both celestial lights during both the day and night could have been marked.

- Different celestial light sources, such as stars, patterns of celestial objects, planets, our moon, and our sun, were probably involved.

- The documented purpose of marking and keeping track of celestial lights over time, according to tribal representatives, involved knowing the time of the season and coordinating ceremonies needed to balance the world and help it sustain life. Time was a critical marker of life events.

2. Ethnographic Background Studies

Given the sensitive nature of this study, it is important to understand that the analysis is directly based on and in keeping with approved tribal and pueblo representatives who shared cultural information during our ethnographic studies. These include four Celestial Light Marker studies on (1) a solar calendar in Utah, (2) the sandstone arches and hoodoos in Arches National Park, (3) the light-marking structures at Hovenweep National Monument, and (4) the world-famous time marker atop Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Park. These four Celestial Light Marker studies and our National-Park-Service-funded study of Canyonlands National Park are combined in this analysis with Indian Creek studies funded by the Bureau of Land Management. Together, they are the foundation of this analysis. Each of the ethnographic studies provided specific findings that are both illustrated and briefly discussed. The current analysis purports to understand the Indian Creek Celestial Light Marker in terms of (a) why it was placed at this location and (b) when it was primarily used.

This analysis argues that it was a World-Balancing geosite. World-Balancing geosites such as Sugar Loaf Mountain on the Colorado River and a range of Origin Locations (Van Vlack et al. 2024) are selected by Native Americans to restore balance and resolve major and widespread environmental or social problems such as drought or sickness. The analysis argues that the Celestial Light Marker was especially critical to the people of this region, who used it as a component of World-Balancing ceremonies to understand and resolve large-scale weather and climate changes occurring from AD 1200 to 1300, when the Little Ice Age began.

Our past ethnographic studies considered the traditional Native American uses of their ancestorial lands and why they created various Celestial Light Markers. These markers were used to understand time. Such knowledge was needed by religious leaders to schedule and coordinate ceremonies. Some ceremonies involved controlling and influencing the weather and climate conditions that most influenced agricultural economies, which supported large farming populations. Snow and rain were essential sources for irrigated farming along streams and rivers; however, the warmer and wetter conditions from 500 AD to 1300 AD provided major support for dryland farming. The latter style of farming was especially vulnerable to changes in regular patterns of rain and snowfall, as well as the amount of water provided to the streams and rivers.

Archaeology and rock art studies have documented how ancient humans responded to changes in the environment, including those associated with climate shifts during the mid-Holocene in Patagonia, South America (Villanueva et al. 2024). Menhir rock erection and relocation occurred in Neolithic coastal Britany (Tilley 1997, 2004). People changed their lives and land uses because of a volcanic eruption in 2360 BP in Southwest British Columbia, Canada (Angelbeck et al. 2024). Shifting river paths due to melting glaciers and weather shifts occurring about 16,000 years ago were documented in rock art in the Coso Mountains of California (Whitley 1998, 2013; Whitley et al. 2020). Multiple geological events that occurred in the Great Basin during the Pleistocene and Holocene have been documented in oral history and rock art (Ruuska 2025). So, there is evidence from oral history and rock art regarding the human ceremonial responses to climate changes such as those discussed in this analysis.

2.1. Case One: Solar Calendar in Utah

The solar calendar located on a high and narrow sandstone fin on a mountain side above major aboriginal farming areas along Santa Clara River in Utah has been included in other publications, so details are not repeated here (Stoffle et al. 2008). This geosite with rock peckings appears to be isolated, unlike the other examples in this analysis, which have a clear position in a much larger geological and cultural landscape. It is important to note, however, that a stream of celestial light passes into the cave from a V-shaped crack above the entrance and shines on a large sandstone slab, which has been smoothed and elevated to receive the light. According to Native representatives, the edge of the slab has time grooves, and the smoothed slab is covered with dozens of connected rock peckings. The slab was moved to catch the celestial light and, in some way, activate a message connected with both time and the many connected peckings. It was physically engineered to function as a Celestial Light Marker according to tribal representatives.

2.2. Case Two: Arches National Park, Utah

The area called Arches National Park contains more than 2000 places where upright sandstone features have eroded to produce what the NPS (2024) calls windows and what Native representatives participating in ethnographic studies call portals (Figure 4 and Figure 5). “Arches” is a term that they both use. The 2000 arches face in all directions and, thus, are open to many celestial features, as well as the culturally important regional Sky Islands (Stoffle et al. 2016, 2020). This was an ecologically connected landscape during the Pleistocene, but the much warmer and dryer Holocene climate divided it into a woodland forest in the high mountains and arid valleys, thus creating what is called Sky Islands.

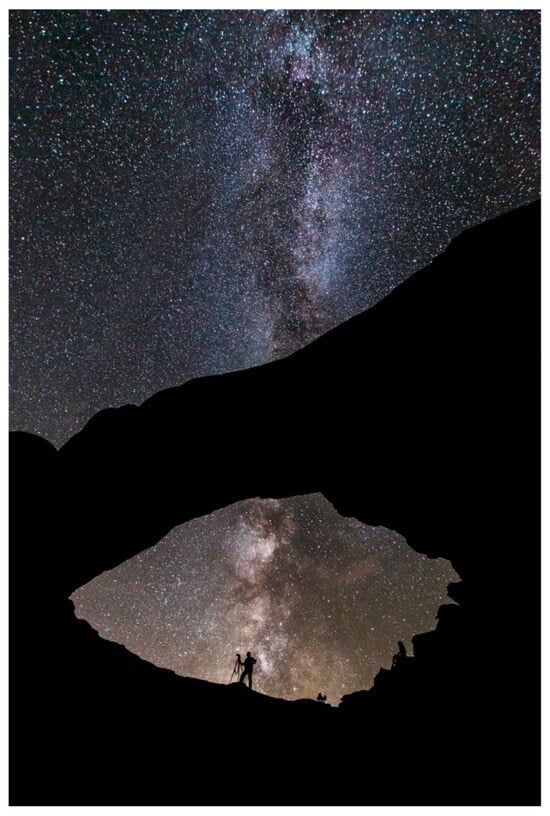

Figure 4.

Arch and hoodoos (source: Stoffle).

Figure 5.

Night sky through and around an arch (NPS and Frank 2024).

Native people believe the arches were made at Creation to be used to mark the times for ceremonies, as a place for ceremonies, and as portals to other times and dimensions. Again, the complexity of these Celestial Light Markers has been discussed elsewhere, but key for these analyses is that the markers include hoodoos and arches. In addition, the study established that night lights and events were key.

2.3. Case 3: Hovenweep National Monument, Utah and Colorado

Hovenweep National Monument is composed of Celestial Light Markers that include walls that were engineered to have holes through them to permit the passage of celestial light (Stoffle et al. 2019, 2020). Some structures were built in relationships with each other so that they marked time with shadows of light between and on buildings. Tall, multistoried stone towers were built to view the sky, pray to distant Sky Islands, and conduct ceremonies. Some prayers were made to at the springs below the towers through the massive rocks on which they were constructed (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Square tower on a massive vertical free-standing stone at the head of a canyon (source: Stoffle).

Structures associated with ceremonial underground kivas often were concentrated at springs at the heads of small canyons. Structures at these locations had tall multi-storied square towers and were surrounded by square or round towers on the canyon rim. These structures were used, according to tribal representatives, to tell time and pray for rain and snow. Prayers asking for rain and snow were sent into the nearby spring and then descended into small streams, from which they flowed to the San Juan River and then to the Colorado River. The prayers were then carried by the big river to the Pacific Ocean. In the ocean, these payers were given to the water and clouds, which returned to the Sky Islands and wide dry plains. Beyond this analysis, there are useful ethnographic comparisons of the cultural meaning of rocks and springs among the Cherokee (Loubser and Ashcraft 2020).

Other prayers were sent from the tops of towers and directed to the Sky Islands, which were asked to talk with the clouds from the ocean and request that they bring the rain to the mountains and agricultural fields and to do so when most needed by the crops.

Hovenweep was a place for the religious leaders from around the Mesa Verde World to again gain control of the weather as they had in earlier years. Now, with more frequent and longer droughts and rain falling at times when it was least useful for agriculture, the priest class of the Mesa Verde World came together in the AD 1200s to make a ceremonial village like no other. As Hovenweep structures were constructed, and the combinations of buildings and kivas were used to talk with the water and pray for better weather. The structures were among the finest ever made. Clearly, they were the product of skilled construction engineers, and each was planned by astronomers to capture and mark celestial light. Some examples are provided here (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Stone structures with celestial-light-marking holes in walls (source: Stoffle).

Structures in the Cajon Unit in one of the Hovenweep canyons were built along the canyon edge and on a single massive natural stone that emerges from the canyon bottom near the spring (Figure 8 and Figure 9). All structures on the canyon edge have walls containing holes through which celestial light is emitted to mark time. The structures have primary outside walls that are built to cast shadows against each other, and in so doing, they tell the time.

Figure 8.

Cajon Unit stone structures with walls that mark time with shadows (source: Stoffle).

Figure 9.

Cajon Unit structures with multiple holes in walls (source: Stoffle).

Nearby the structures on the canyon edge is an small engineered rock shelter located under the canyon rim. This rock shelter has an engineered outside wall that is designed to capture celestial light that shines through it in ground stone depressions, each of which represents one of the five visible planets in our solar system (Figure 9). Nearby is a shallow cave with a stone-built wall that has two large planned holes that cast light on carved holes representing visible planets.

The spring at the Cajon Unit geosite still regularly emits water; when there is a full stream, it runs into the San Juan River. Native representatives said that prayers from inside the kiva and structures would go directly into the stream and the river.

2.4. Case Four: Fajada Butte, Chaco Culture National Historic Park, New Mexico

In the early 1990s, the NPS funded an ethnographic study of a geosite called Fajada Butte, which is located in a geoscape (Chaco Canyon) and in a geo-region (the Chaco Cultural Interaction Sphere). Without question, based on Native responses, these places are framed by the topography and geology of the area (Stoffle et al. 1994). The geotrails are primarily for pilgrimages and ceremonies, and they radiate for hundreds of miles in all directions. All of these geo-components are now recognized by scholars and Native people alike as contributing to the Chaco Culture World; therefore, the current name, Chaco Culture National Historic Park, is accurate from multiple perspectives.

Before the ethnographic study of Fajada Butte, it primarily was known as the location of one of the most complex solar and moonlight markers in North America (Sofaer et al. 1979; Sofaer and Sinclair 1982). After seven tribes and pueblos participated in the ethnographic study, Fajada Butte was understood as much more complex than just the Celestial Light Marker. The Native findings were reviewed and approved by all of their cultural departments and governments (Stoffle et al. 1994). This ethnographic study was initially focused on what was then the famous Celestial Light Marker on a charismatic butte. The Native participants agreed that such a marker is only understood according to the objects, places, and landscapes within which it is culturally and historically embedded. One cannot understand the geosite of Fajada Butte and the light marker alone.

The following is a list of the top 11 culturally significant components of Fajada Butte according to on-site visits by tribal and pueblo representatives (Stoffle et al. 1994). These components are organized from the top down to the base of Fajada Butte. The Sun Dagger is important, but it is only one among the other components. For some representatives, the rooms for astronomers and the peckings that were only reached from their roofs were the key components. The contemporary Eagle Nest was generically viewed as a temporal connection of the heritage of the Fajada Butte complex beginning at Creation and continuing throughout early times and through today. As each visiting set of tribal and pueblo representatives passed below the Eagle Nest, a feather dropped into the group. The prayer shrine on top of Fajada Butte is used for contemporary Native American communities to transport prayers to other spatial and temporal dimensions.

- 1.

- Prayer shrine on top of Fajada Butte;

- 2.

- Contemporary ceremonial area on top, now used by the Native American Church;

- 3.

- Eagle’s Nest edge, rim of the Butte, and falling feathers;

- 4.

- Sun Dagger just below the top of the Butte;

- 5.

- Rooms where astronomers lived along the edge of the upper side;

- 6.

- Calendars and symbols near the roofs of astronomers’ rooms;

- 7.

- Minerals, mostly on top;

- 8.

- Hogan on the lower flank of Fajada Butte;

- 9.

- Petroglyph panel away from the base of Fajada Butte;

- 10.

- Support for family living and cooking quarters—north and south of Fajada Butte;

- 11.

- Plants used by American Indians are widely distributed around the base of the Butte.

It is important to note that all 11 of these cultural components were perceived by the Native representatives to be among the reasons that Fajada Butte was and is an important heritage geosite for Native Americans today. A key observation and cultural interpretation of Fajada Butte is the difficulty of intellectually resolving—much less merging—the epistemological differences between Western science and Native science. The following are two examples of this difficulty.

3. Tsa’aktuyga (A Hopi Perspective)

Ta’a, pay nu’ yev tuyqat tungway’a, hal owi, pan itam aw wuuwaya kye i’ pamhimu papiq oovi piw tu’awi’ytaqw pam himu taawa haqe’ qalawmaqwtsa’lawngwu; himu tiingaviwngwu. Pam songa put aw awiwaniqw paniqw payoovi itam panwat tungwayani, Tsa’aktuyga. Papiq pam ang tuvoyla’at pe jryunggwhaqe’ taawa pakye’, haqe’ galawmagw put pant hapi tsa’lawngwu so’onge yaapiqooveqa. Pay yan itam son it qa aw oovi panayani, Hopivewat tsa’aktuyga.Tsa’akmongwit hapi i’ tiingappi’ata, tsa’lawpi’at piiwu.(Translated by Hopi Scholar Emory Sekaquaptewa)

Verily, I have given a name to the rock point here, that is to say, we have concluded that this is something that represents the place from which someone [appropriate] makes his announcements giving the positions of the sun [from season to season]; so that preordination of life- giving activities [i.e., ceremonies, planting, harvesting, etc.] can be given. It is undoubtedly used for that purpose, that is the reason we have given it the name, Tsa’aktuyqa. There are line drawings [on the rock] up there for marking sunsets [on the horizon], telling the positions of the sun that he must announce from up there. This is the way we are going to enter it [in the report], that according to Hopi practice this is the announcing point. The Crier Chief uses this as his place of declaring preordinations, his announcements. (Figure 10) Figure 10. Fajada Butte, NPS Chaco Culture National Historic Park (source: Van Vlack).

Figure 10. Fajada Butte, NPS Chaco Culture National Historic Park (source: Van Vlack).

4. A Western Scientific Perspective

At the summer solstice, before midday, the shafts of light illuminating the cliff face interact with the large spiral in a visually striking manner (UCAR 2024). Shortly past 11:00 am local solar time, a small spot of sunlight first appears above the large spiral. It lengthens vertically into a very narrow, downward-pointing elongated triangle (or “dagger”). The dagger continues growing and moving downward until, around 11:15 am, it cleanly bisects the spiral almost over its entire height. At this point, the sun is high enough in the sky for the overhang above the site to begin casting a shadow on the slabs, and in doing so, it cuts off the upper end of the dagger (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Sun Dagger (Source: UCAR 2024).

A lesson from these foundational Celestial Light Marker studies is that, while some commonalities can exist, the differences between Western science and Native science are difficult to resolve because they are rooted in epistemological differences. Similarly, while multiple tribes and pueblos often have a common heritage and understanding of a geosite, each cultural group has different interpretations of these geosites, including their origin, history, and purpose.

5. The Study Area

Some of the tribal and pueblo interpretations used in this analysis are specific to this ethnographic study area, while other interpretations are applicable to the surrounding cultural region or geoscape, and still others refer to general Native American epistemologies of how these heritage places are temporally related over thousands of years and spatially connected across hundreds of miles. The Mesa Verde World is an archaeological term for this larger region. Similarly, the temporal scales vary in their interpretations. Even the concept of time is regularly disputed. These different scales of interpretation occur because Native cultural landscapes exist without regard to contemporary Western boundaries of space and time (see Section 11).

In this analysis, the study area is called the American Indian Crossing of the Colorado River (AICC) (Figure 12). This term reflects an ancient functionally integrated cultural area that has been defined at the request of tribal and pueblo participants who wish that, through this designation, others will better understand Native cultural heritage objects, history, and places. These Native American representatives stipulate that their heritage should be interpreted, understood, and managed holistically, as was done aboriginally.

Figure 12.

Study area: The American Indian Crossing of the Colorado River (AICC) and a portion of the Mesa Verde World (source: Van Vlack et al. 2025a).

The AICC area where Native Americans lived and conducted ceremonies for tens of thousands of years includes the Abajo Mountains to the south, the La Sal Mountains to the northeast, 2000 sandstone arches in Arches National Park to the northeast, the Henry Mountains to the west, and the major traditional trade and travel trail (which is a geotrail) that crosses the Colorado River. This ancient and primary geotrail crosses the geoscape at Moab Valley, but it subsequently crosses the Green River to the north, the Mancos and La Plata Rivers to the east near Mesa Verde, and the San Juan River to the South. This ancient geotrail connects the broader region physically and spiritually.

According to hundreds of ethnographic interviews, the AICC and its component features have been culturally important places for all of the participating Native American representatives since Time Immemorial or Creation. Ancient Clovis and Folsom spear points have been found in the AICC area, but they do not define the earliest occupation of the AICC. Recent geoarchaeological studies have documented the presence of Native people in an even broader region called the Colorado Plateau of the Southwest United States. Therefore, the broadest temporal frame for this heritage analysis is operationally defined as the late Pleistocene, which occurred between 128,000 BP and 11,700 BP, and the Holocene, from 11,700 BP to modern times. Scientific studies document Native Americans by at least 37,000 BP, with geoarchaeological dates of 23,000 to 21,000 BP at White Sands, New Mexico (Bennett et al. 2021; Pigati et al. 2023) and 38,900 BP to 36,250 BP at the Hartley locality, a mammoth kill site situated near the Rio Puerco, New Mexico (Rowe et al. 2022). These geoscientific dates indicate that Native peoples of this region experienced this environment as a massive wetland filled with lakes, rivers, and swamps and later as an arid desert with small streams and artesian springs (Grayson 1993). Timekeeping and celestial marking would have been adjusted to understand climate changes (Villanueva et al. 2024), and massive geological changes would be remembered with oral history during these periods (Angelbeck et al. 2024).

This heritage analysis builds on the burgeoning academic literature that has responded to the United Nations’ call for the identification of geological places and landscapes as cultural heritage deserving preservation (Brocx and Semeniuk 2017). The ICUN and the WCPA have a Geoheritage Specialist Group that has documented the need for such new heritage preservation approaches (IUCN 2024). This need is illustrated by the 20 published peer-reviewed papers in the Special Issue of the journal Land entitled Geoparks, Geotrails, and Geotourism—Linking Geology, Geoheritages, and Geoeducation, edited by Brocx and Semeniuk (2022). This Special Issue included studies from Europe, Australia, the USA, Latin America, and Asia. Subsequently, published articles on this topic are illustrated by Geoheritage and Cultural Heritage Overview of the Toba Caldera Geosites, North Sumatr, Indonesia (Muzambiq et al. 2024). These studies document a range of complexities involved in preserving, interpreting, and managing complex geoheritage. Practitioners of the profession of geology, through the International Commission on Geoheritage (IUGS 2024), have responded by identifying significant geosites around the world using both their science and humans’ significance as criteria (IUGS 2024).

The current analysis draws on these new geoheritage approaches for the identification, interpretation, and management of Earth Places because the structure and function of the Celestial Light Marker significantly depends on the geology and topography of the lands involved.

All of the participating tribes and pueblos have an ongoing cultural association with the AICC (Figure 12). They have stipulated that this is a culturally and functionally integrated area that is interlaced with pilgrimage trails and has been since Time Immemorial. The AICC is best understood as a component of the Mesa Verde World. The term geoscape is used for the AICC and Mesa Verde World given the many special topographic features that structured these cultural places.

Participating tribes and pueblos stipulate that they are from this area and the Mesa Verde World, even if they live elsewhere today, and that they continue to keep the area, the region, and their connections alive in their ceremonies and prayers. They maintain that these are living ceremonies that were established at Creation for the use of all Native peoples. Like the people themselves, these geological and topographical places remain alive, and all are committed to their original purpose of providing balance to the world.

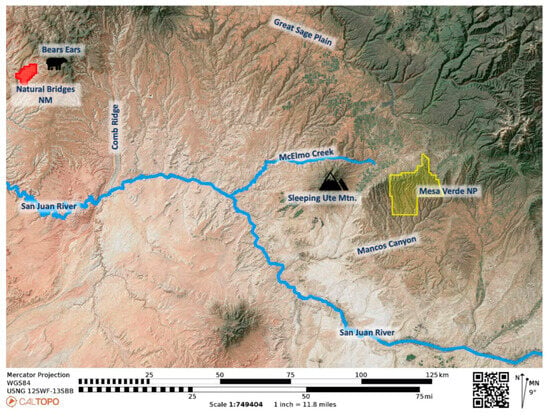

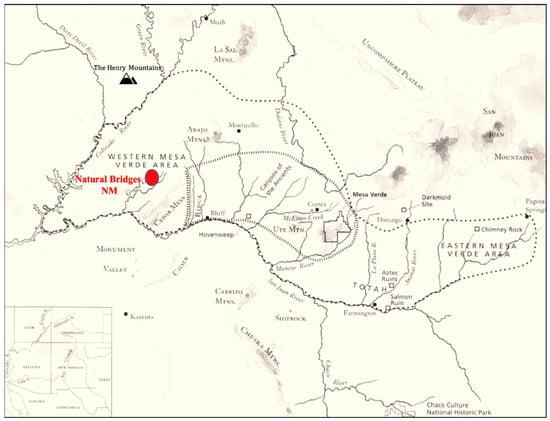

The Mesa Verde World

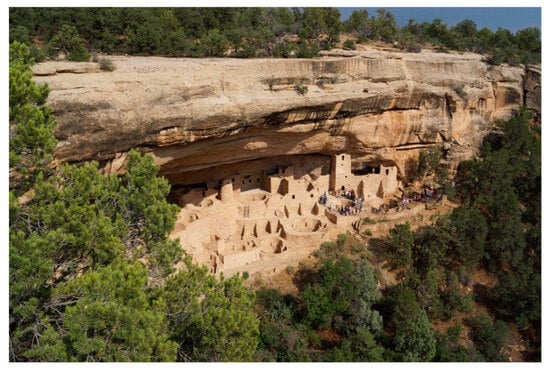

Late 19th Century and early 20th Century scientific efforts to understand the character of the Native American people who lived in this region and made its spectacular stone structures began on a large south-sloping mesa with deep canyons that is called Mesa Verde (Figure 13). These stone cities built in the alcoves of high canyon walls on this isolated forested mesa caught the imagination of the world as expedition after expedition explored it, excavating the structures and carrying away human remains and artifacts (Figure 14). Cliff Palace is pictured here under a canyon rim alcove surrounded by cedar forests (Figure 15). The name Cliff Palace reflects the notion that the ceremonial or political elite lived here and elsewhere on the isolated mesa.

Figure 13.

The Mesa Verde World with Mesa Verde National Park in Yellow, the mesa, and San Juan River in Blue (source: Stoffle).

Figure 14.

Canyons atop Mesa Verde (source: Stoffle).

Figure 15.

Cliff Palace on Mesa Verde (source: Stoffle).

Eventually, U.S. national concerns that European museums were stealing trainloads of U.S. heritage caused the passage of the Antiquities Act of 1906 (U.S. Congress 2025), which gave the U.S. president the power to define national monuments and regulate archaeological excavations and the removal of artifacts. The charismatic stone cities of Mesa Verde, in fact, would become the center of southwestern archaeological research and teaching which would stimulate theories and speculation about why Indian people chose to live on this high mesa and build large cities in isolated places.

Today, Mesa Verde and its heritage are managed by the U.S. National Park Service, and the park has become a U.N. World Heritage Site. The isolated mesa-top communities and the way of life remain wildly popular for millions of tourists. The term Mesa Verde society, however, has become somewhat of a distraction from the emerging story of the much larger and more complex functionally integrated set of communities living elsewhere.

Mesa Verde society was influenced by the diverse geology and topography of the isolated mesa, with steep sides, a high elevation, and dense forest. On Mesa Verde, farming was a challenge because the mesa lacks large streams and even surface water, so rainfall was essential, and only limited irrigation from springs, small streams, and engineered ponds was possible. Large communities lived in sandstone alcoves, but many people lived in isolated farm homes.

Far away from this isolated mesa, people lived in small, dispersed communities or rancherias on the more open and expansive Great Sage Plain (See Figure 16), where farming was largely supported by rainfall. A few large rivers, such as the San Juan, did support larger irrigated farming communities. Archaeological studies have been carried out, such as those associated with the BLM-managed Canyons of the Ancients National Monument (Canyons of the Ancients 2024) in Colorado. New archaeological studies identified thousands of farming locations beyond Mesa Verde, and it became clear that the people of Mesa Verde were but a portion of a larger, culturally similar, and interconnected society that existed for hundreds of miles in all directions. Thus, the initial archaeological studies of Mesa Verde were too temporally and spatially restrictive to understand what life was like for the Native people of the broader region (see the discussion in Section: The World According to Pimm and Tribal Elders).

Figure 16.

Archaeologists’ interpretation of the Mesa Verde World (sourced from Noble 2006; Varien 1999; Wilshusen and Glowacki 2017).

After hundreds of years of population growth, which began around AD 500, these small farm residences supported by dryland farming were increasingly moved according to the plans of religious leaders to be near Great Houses with large central structures, kivas, and dance grounds. This style of community life began to typify the region around AD 1050.

In order to make more accurate generalizations, as well as distinctions in regional archeology, settlement patterns, and ecological variation, Noble (2006) and others (Varien 1999; Wilshusen and Glowacki 2017) reframed earlier theories into a much larger and more complex model of this region as part of a culturally, economically, politically, and religiously integrated society called the Mesa Verde World (Figure 16).

The Mesa Verde World model stretched from west to east, from the Colorado River in Utah, past Mesa Verde proper to east of the present town of Durango, Colorado. For the purpose of this analysis, the Mesa Verde World also extended from the north along the flanks of the La Sal Mountain Massif to the San Juan River in the south. Archaeologists called the region the Mesa Verde World after the famous place named Mesa Verde.

While the isolated Mesa Verde is the term of reference in this archaeological region, most people lived somewhere else, and there are no current arguments that it was the center of the region. The Great Sage Plain, for example, is located to the north and east of Mesa Verde and was a place of great agricultural productivity that supported large farming communities with large central ceremonial structures (Wilshusen and Glowacki 2017). These large agricultural communities located away from Mesa Verde were more typical of those that existed throughout the broader Mesa Verde World.

Finally, in the early 21st Century, archaeological surveys and excavations of the surrounding areas challenged the notion that Mesa Verde was the cultural center and replaced it with research findings that there were many other population centers with large ceremonial areas containing groups of kivas and dancing grounds. Evidence shows that these Great House centers would be concentrated under the guidance of religious leaders who guided the performance of ceremonial activities, which involved weather control in the hopes that tens of thousands of farming people would have bountiful crops.

Further evidence from four regional ethnographic studies in Arches NP (Stoffle et al. 2016), Canyonlands NP (Stoffle et al. 2017), Hovenweep NM (Stoffle et al. 2019); and Natural Bridges National Monument (Stoffle et al. 2022) document that Native American farmers lived and occupied an area west of the La Sal Mountains and to the south towards Cedar Mesa. These studies now incorporate settlements located north of the Abajo Mountains extending to Salt Creek and Indian Creek in the Canyonlands area and the farm communities in Moab Valley. These populations lived beyond the boundaries posed by archaeologists in the earlier works on the Mesa Verde World, and certain criteria of that designation were not met. However, the communities and lifestyles were culturally similar, and by including the communities along Cedar Mesa, the northern slopes of the Abajo Mountains, and the villages along the Colorado River, the population data suggest that another 10,000 people lived within these northern areas. It appears that large farming communities situated in a culturally integrated regional society of approximately 80,000 people lived in the western and central Mesa Verde World.

These other population centers, which were located in open areas with large ceremonial centers with groups of kivas and community dancing grounds, would be concentrated under the guidance of religious leaders to perform ceremonial activities involving weather control. The 800-year period from 500 AD to 1300 AD was fraught with shifts in weather despite the wetter and warmer environment. So, the concentrated Big House settlements and ceremonial areas in the later part of this period were occupied in the hopes that tens of thousands of farming people would have bountiful crops. Our data indicated that this was the primary social and environmental setting within which the Celestial Light Marker was a key feature.

In summary, the Mesa Verde World (Noble 2006) was developed over an 800-year period from approximately AD 500 to AD 1300. The rise of the Mesa Verde World was preceded and built on a thousand years of experimentation with cultigens as a part of a horticultural economy that mostly relied on small-scale plant management, natural food gathering and conservation, and hunting. The early portions of this period involved climate changes that included warmer weather and increased rainfall. Such a climate shift occurred throughout North America and, thus, resulted in dramatically improved dryland and irrigated farming conditions, population growth, and evolving social complexity.

The post-Mesa Verde World began during the Little Ice Age and continued for hundreds of years from AD 1300 to the mid-1800s. A colder climate, less predictable weather patterns, and less rainfall greatly reduced or eliminated the dryland and irrigated farming that had supported the earlier rise of populations. So, during the Little Ice Age, Native lifestyles and population sizes were quite different from what they had been during the previous 800 years. Native American social, demographic, and cultural responses to the Little Ice Age are contested by some scholars. However, some speculate that the region was no longer occupied; for example, see Leaving Mesa Verde (Kohler et al. 2012). Native American representatives who were involved in our ethnographic studies, however, maintained that they never abandoned this ancestorial homeland, even though some people did move to other areas for their primary residence. Other Native American representatives maintained that they never left their traditional homelands but did change their lifestyles.

In this analysis, we argue that the Celestial Light Marker was primarily used in the ceremonial activities of the people in the surrounding AICC and Mesa Verde World. It may also have served similar functions before and after this time, but given the centrality of celestial light calendars in helping structure weather ceremonies related to agriculture, it must have occupied a central position during the period of climate change that ended the Mesa Verde World.

6. Methods

A total of 522 ethnographic interviews provide the foundation of this Celestial Light Marker analysis, including 316 with the NPS and 206 with the BLM. These ethnographic studies funded by federal agencies were conducted by trained cultural anthropologists from the University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ (Stoffle et al. 2017), Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ, and the Heritage Lands Collective, Cortez, Colorado (Van Vlack et al. 2024). An ethnographic overview and assessment (EOA) study was funded by the NPS and conducted at Canyonlands National Park. This EOA included Indian Creek and the viewscapes from the park. The Bureau of Land Management ethnographic partnership study and the Moab ethnographic study focused on management areas surrounding the Canyonlands, especially the Indian Creek area and the Abajo Mountains, and to the north along the Colorado River.

No confidential information was sought during any of the involved ethnographic studies. Participating appointed tribal and pueblo representatives, their cultural departments, and their governments reviewed, edited, and approved their own chapters in these reports for public use.

6.1. Canyonlands National Park EOA

The Canyonlands NP ethnographic overview and assessment (EOA) occurred from 2015 to 2016 (Stoffle et al. 2016). The study involved six tribes and pueblos, including the (1) Pueblo of Zuni, (2) Southern Ute Indian Tribe, (3) Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, (4) Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians, (5) Navajo Nation, and (6) Hopi Tribe. Representatives of each tribe and pueblo participated in their own confidential interviews conducted by a trained ethnographer. A total of 316 formal data collection events occurred.

The overall objective of the EOA was to prepare an ethnographic report for Canyonlands NP that documents and evaluates culturally significant American Indian objects, natural resources, places, and cultural landscapes. These ethnographic findings can be used to support public education and park interpretation to increase understanding of American Indian tribes’ and pueblos’ traditional connection with the park. The findings of this report are available to the public (no sensitive cultural information was sought) and can be used as inputs into park management plans, environmental assessment work, and interpretation planning, as well as in other park-resource-related management decisions.

6.2. BLM Utah Monticello Field Office Ethnographic Information Partnership

The two-part BLM study focuses on how to best inform the Monticello Field Office (MFO) officials regarding Native American tribal connections to the Cedar Mesa area and how they have utilized the ethnographic resources found within this complex landscape. To accomplish these goals, the BLM funded Van Vlack through the Heritage Lands Collective to design and conduct a two-phase research study. Phase One focused on building an ethnographic literature review of traditional tribal associations with the MFO, including the greater Cedar Mesa area (Van Vlack et al. 2025b). Phase Two involved tribal site visits to places within the MFO, including Indian Creek and Bears Ears National Monument (Van Vlack et al. 2025a).

A second BLM-funded study was entitled Moab Ethnographic Study: Southern Paiute and Ute Perspectives (Van Vlack et al. 2023). This study occurred from 2019 until 2023. This study involved Native American cultural landscape perspectives of the lands around the town of Moab, Utah and those in between Arches and Canyonlands National Parks. Also included were lands to the north, such as the Book Cliffs, Utah. For this project, HLC brought traditionally associated tribes to a range of places throughout the study areas and interviewed tribal representatives regarding meanings according to cultural history, traditional/current use, and management recommendations. The second study involved representatives of the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. These appointed cultural experts provided 102 interviews on several places, including Indian Creek (Van Vlack et al. 2023).

6.3. Issues of Ethnographic Analysis

A critical methodological issue raised in this analysis and elsewhere is completing the analysis. In general, there is a tendency in technical reports to get to “the answer”, and sometimes, this is more or less possible. More common is the issue of cultural multivocality. Two examples are provided here.

6.4. Group Interpretation Agreement

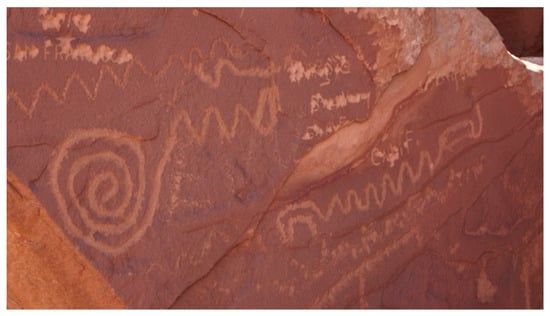

Native representatives identified a pecked spiral and sandal footprint as having been left by their migrating clans, who subsequently returned to their respective pueblos. All American Indian people identified footprint peckings, such as those at Newspaper Rock, as part of their physical and spiritual travel. Similarly, spiral peckings, which are located throughout the greater Arches NP and Canyonlands NP region, were noted as significant cultural features representing travel (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Sandal footprint at the Moab Panel, footprints at Newspaper Rock, and a spiral at the Celestial Light Marker (source: Stoffle and Van Vlack).

6.5. Tribally Specific Interpretations

In addition to general agreement regarding the meanings of some peckings, there were others that had widely different interpretations. At one large pecking panel in the Canyonlands, the Zuni identified a spatially isolated pecking as representing their origin climbing up a reed (called Phragmites) into the Present World Dimension (Figure 18). The reed also grows in the park wetlands nearby. The combination of the pecking depicting their emergence up the reed pecking and the contemporary presence of the Phragmites reed makes the area culturally special to the Zuni (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

Phragmite pecking and Phragmite plant held by a Zuni representative (source: Stoffle).

At the same rock panel are peckings of people riding horses (Figure 19). These peckings were interpreted as repressed Ute horse riders in historic times. Both the Ute tribal representatives and the NPS call this the Ute Panel, and both have no interpretation of the Phragmite pecking. In addition, while the Ute representatives focused on the horse riders, most other cultural representatives focused on the peckings of large mountain sheep, mountain lions, and small dogs.

Figure 19.

The Ute Panel (source: Van Vlack).

The issue of rock pecking panels telling only one story with their images is widely discussed by scholars. This so-called Ute Panel is much more complex than horse riders, especially given that mountain sheep are Spirit Helpers for all participating tribes. The best resolution of multivocality, in our opinion, is to present all cultural interpretations in the technical report and not to assign the rock pecking panel to one cultural group. The key is having the representatives and their governments review the multivocal presentation in the report and then provide them with official recognition in park spaces, such as in official reports and displays that convey heritage interpretations to tourists.

7. The Celestial Light Marker

The Celestial Light Marker, which is the focus of this analysis, can only be understood as a functionally integrated component of the land, the people, and the history of this region; it is referred to above using the terms the American Indian Crossing of the Colorado River (or AICC) and the Mesa Verde World. The Native people interviewed in this study viewed these lands as a special component of Creation. Here, there are natural elements that made it possible for Native people to thrive; therefore, their large communities filled the valleys for 2000 years with many irrigated and dryland farming communities.

Central here is water, and given our operational definition in this analysis, these natural features have existed in various forms since the late Pleistocene and through the Holocene. Rivers, lakes, and wetlands have always provided habitats for birds, fish, and mammals of all sizes and varieties, including the mastodon, an image of which is pecked into a sandstone wall near the town of Moab. The rapid changes in elevation between valleys and mountains created a variety of ecozones with diverse and abundant flora and fauna. The Colorado River has carved deep, vertical, and almost impassible canyons that line its banks for hundreds of miles upstream and downstream of the contemporary town of Moab, Utah. At this low canyon wall crossing is the AICC because there are no canyon walls on either side of the river, and the smooth bottom results in quiet water that is easily passable year-round. In the winter today and certainly in the past, the quiet river often freezes over, and it can easily be crossed. The major cross-country AICC trail is followed by the Old Spanish Trail, regional roads, and now major highways along the ancient lines of least resistance that it defined.

Indian Creek was interpreted by Native representatives as a spiritual area primarily used for ceremonies (Figure 1). The headwaters of Indian Creek are the Abajo Mountains and Elk Ridge Sky Island, and at the river mouth, it joins the Colorado River. The neighboring Salt Creek to the west supported massive residential communities based on dryland and irrigated farming. Newspaper Rock is an almost unique collection of rock peckings located where Indian Creek Canyon begins. The river is lined with almost constant rock peckings on the canyon rim and walls. Lower down the river (that is, to the north) is a Ghost Dance site, which was probably chosen because it was already a traditional Round Dance ceremony area. Further downstream, there is an area for curing that contains a large Medicine Rock. The Celestial Light Marker is about a mile further downstream.

The Celestial Light Marker encompasses 12.7 square miles of socially constructed and physically engineered geoscapes. This area roughly measures 4.02 miles from east to west and 2.73 miles from north to south. Elevations are key in defining views and capturing light. From sea level to its top, the North Peak is 5612 feet high. The North Peak, from its mesa base to its top, is 6242 feet in elevation. The mesa base of South Peak is 5461 feet above sea level, and its top is 6074 feet in elevation.

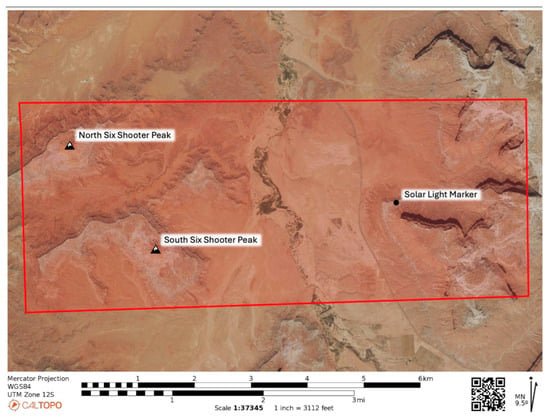

The Celestial Light Marker viewscape spans Indian Creek, which flows to the north at 5128 feet above sea level (Figure 20). The marker sits at a fallen mesa-top remnant on a lower ledge at 6263 feet high. Behind the Celestial Light Marker is a mesa at 6601 feet above sea level. Some features of the geosite are presented next with minimum interpretation. The exception to this point is the speculation that the slabs at the marker have been moved and set in place. This is argued based on the presence or lack of desert varnish and lichen, which is a hybrid colony of algae or cyanobacteria.

Figure 20.

The Celestial Light Marker is highlighted in the red box, and it spans Indian Creek.

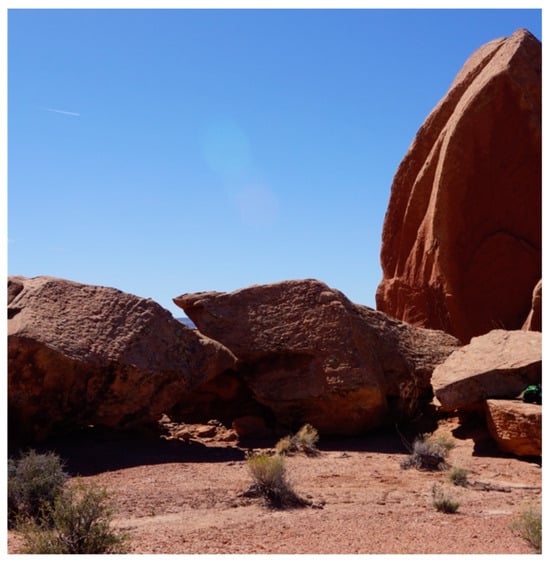

7.1. Fallen Mesa Remnant

The Celestial Light Marker is a component of a nearby mesa (Figure 21), a portion of which has fallen. The remnant mesa cap rock is isolated on what was once another geological feature but now is a narrow sandstone ledge (Figure 22). The sand on top of the ledge is smooth and level, thus contributing to the development of a ceremonial dance ground nearby. The broken piece of mesa cap contains minerals underneath, including purple clay soil, which is valued by several pueblo peoples as a colorful paint for ceremonies. The purple clay has been identified by tribal and pueblo representatives in multiple ethnographic studies as a valued resource. It is especially so when it derives from a spiritual place such as the Celestial Light Marker.

Figure 21.

Mesa above the Celestial Light Marker, with purple clay at the base (source: Van Vlack).

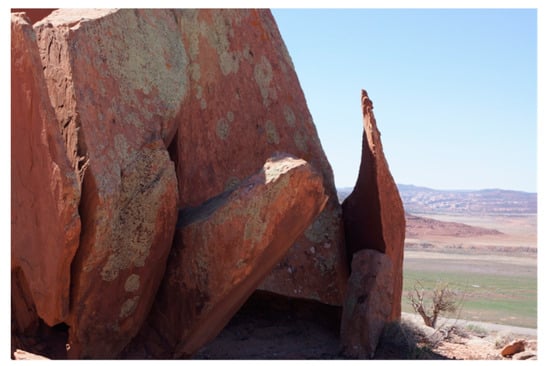

Figure 22.

Fallen and broken mesa caprock used to engineer the Celestial Light Marker (source: Van Vlack).

7.2. Upturned and Supported Stone Slab

On the south side of the fallen mesa caprock is a slab of sandstone that has been engineered to capture, guide, and mark celestial light from the peaks to the west (Figure 23). The light is guided by a pointer that has been sharpened and set upright so it that it casts light or shadows on a single rock panel of peckings.

Figure 23.

Engineered upright slab that focuses light (source: Van Vlack).

It is speculated by the authors that at least three of the sandstone slabs were moved from a former position where they resided for a sufficiently long period that lichen grew on their upper surfaces (Figure 24). The light pointer, the rock supporting the pointer, and the slab on which peckings have been placed to receive light from the pointer all have surfaces without evidence of weathering or lichen growth.

Figure 24.

Engineered and sharpened pointer and support rock in a carved notch (source: Stoffle).

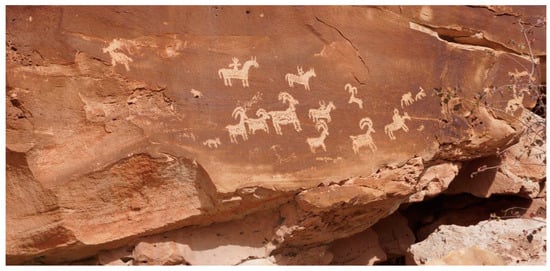

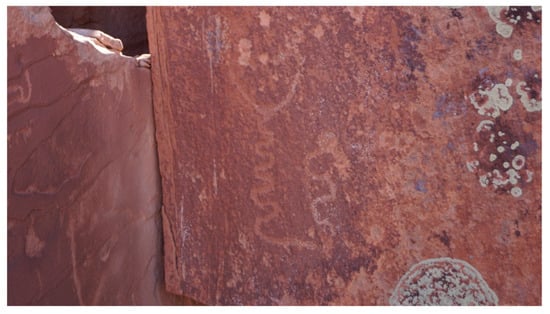

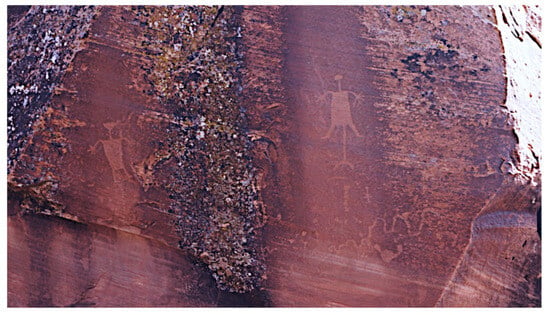

7.3. Celestial-Light-Marking Peckings

To the east of the engineered sandstone pointer, the light is guided to a flat sandstone slab that is approximately six feet tall and is apparently a natural component of the fallen mesa caprock (Figure 25 and Figure 26). Light guided to this panel would come from the west. This large sandstone block appears to have been engineered to be in its current place given that the face is towards the west, from which it receives light. The sandstone block that contains these peckings is covered with desert varnish and faces to the north. Desert varnish occurs when the sun-facing surface of a rock remains in place for thousands of years and has been transformed by the constant radiation and heat. The close-up of the north-facing panel documents a sharp line of desert varnish that contrasts with the west-facing surface, which has no desert varnish.

Figure 25.

Flat sandstone face orientated toward light from the west (source: Stoffle).

Figure 26.

Close-up of the pecking on a flat sandstone face receiving light from the west; note the clean surface on the north edge (source: Stoffle).

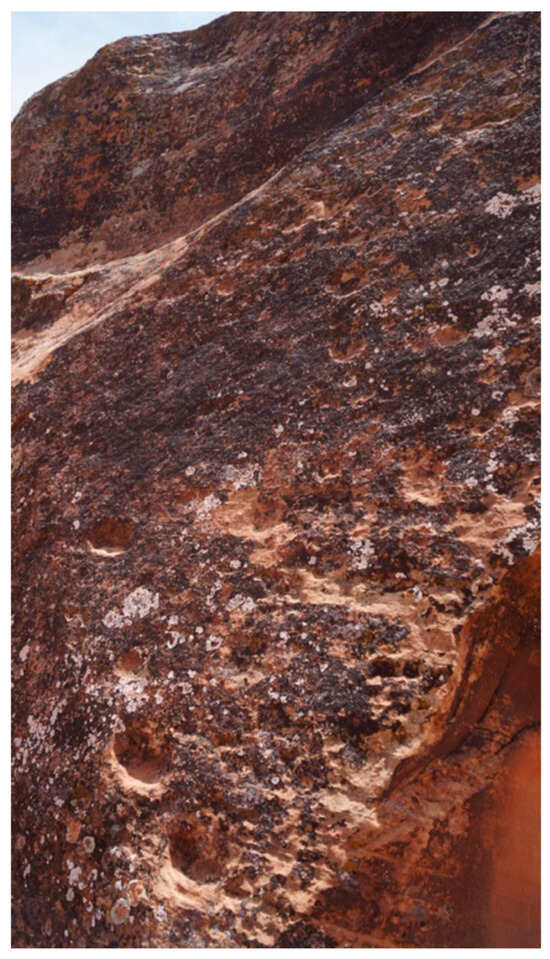

The large boulder containing the west-facing peckings physically touches the larger north-facing surface of the mesa remnant (Figure 27). The west-facing face does not have lichen on it, but the north face does. That north-facing remnant contains peckings, but light from the engineered marker does not currently reach that rock wall. Lichen grows on the north face but not on the west face, suggesting that the latter stone was moved to provide a location to make peckings that can receive and mark light.

Figure 27.

North-facing flat sandstone face with multiple lichens (source: Stoffle).

7.4. The Dance Grounds

The fallen mesa-top remnant sits on a hard, resistant sandstone ledge that fully supports the light marker and is a parallel surface that extends out to the north for about 260 feet before it curves to the east, thus establishing a corner that defines the dance grounds (Figure 28). The surface of the dance grounds is solid underneath and flat but is generally composed of and covered with soft fine sand. The dance ground is covered with offerings of exotic materials, such as chert flakes, pottery pieces, shell bead fragments, chipped stones, and pieces of yellow ochre (Figure 29 and Figure 30).

Figure 28.

The dance grounds to the north of the fallen mesa-top remnant (source: Stoffle).

Figure 29.

Dance ground covered with “offerings” of chert, pottery sherds, yellow paint pigment, chipped stones, and, apparently, seashell fragments (source: Stoffle).

Figure 30.

Yellow minerals often used in paint found on the dance grounds (source: Stoffle).

7.5. The Bracketing Peaks

From all points on the dance grounds, there is a clear view to the south toward the upper Indian Creek, to the west, including the two peaks and the mountains beyond, to the north along the Indian Creek as it flows towards the Colorado River, and to the east up the sharp face of the mesa. The Celestial Light Marker is connected to light that comes from between or near the two peaks illustrated in Figure 31.

Figure 31.

Peaks to the west of the marker (source: Stoffle).

One elder shared the following when he first viewed the area from the highway:

I am just speculating but, of these two points [Six-Shooter Peaks], I am sure there is something there, a site or something that uses these two as a calendar. Maybe the sun goes far to the left during the summer solstice and comes back during the winter solstice, in between the two. I am sure that it is very significant in some way during that time of the year. There may be something to the west of this area.

Another elder pointed out the following:

So that [solar panel] is the observation point. When you have something like that, there is probably something like the mounds [in Indian Creek] you guys just passed. When you get to that point, you look west and east. There is going to be something prominent, either a structure or something there, or a shrine that they used in ceremonies. So that would tell them the times of year. When it reaches its point, then certain ceremonies or things would happen.

8. Analysis Summary: Eleven Key Features

The following are eleven key features of the Celestial Light Marker that adjoins Canyonlands National Park in Utah. These cultural, social, and topographic features were chosen based on ethnographic interviews about this Celestial Light Marker, its immediate surroundings, and where these are situated in the land-based geoscape termed the American Indian Crossing of the Colorado River in this analysis. These key features are the following:

- It is located in a spectacular geological landscape or geoscape.

- It involves views of distant sacred Sky Islands, which are snowcapped mountains.

- It spans Indian Creek, which is a spiritual area that (a) derives from the Abajo Mountains, a Sky Island, (b) contains miles of continuous rock peckings and paintings, and (c) is a tributary of the sacred Colorado River.

- It is visually bracketed to the west by the tall and narrow sandstone Six-Shooter Peaks.

- It receives celestial light that comes from between the peaks and especially a U-shaped dip between the peaks.

- Celestial lights rise and set as planets, stars, patterns of lights, and the Milky Way.

- It is built from a fallen remnant of a 6601-foot mesa but persists as a geosite isolated on a narrow, high ledge above Indian Creek.

- It is associated with a large flat dance and ceremonial area covered with offerings.

- It is near populous ancient Native American irrigated farming communities.

- It is within the viewscape of lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management and the National Park Service.

- It is touched and valued by millions of national and international tourists, including hikers, ecologists, archaeologists, and technical rock climbers.

9. Indian Creek Geoscape

Indian Creek is a culturally integrated geoscape with which we can better explain the Celestial Light Marker that spans it. Indian Creek is considered a spiritual geoscape and, thus, primarily contains geosites used for ceremonies (see Map Figure 12). Currently, based on archaeological and ethnographic research, the Indian Creak geoscape is known to have the following geosites: (1) Newspaper Rock, (2) Shay Canyon Peckings, (3) a Round Dance site that was probably used as a Ghost Dance site in 1890, (4) a Medicine Area with a Doctor Rock, (5) a Ceremonial Preparation cliff face with structures, and (6) a ceremonial support community consisting of at least one large mound with kivas and structures. Most of these geosites are well known, but only three are analyzed here.

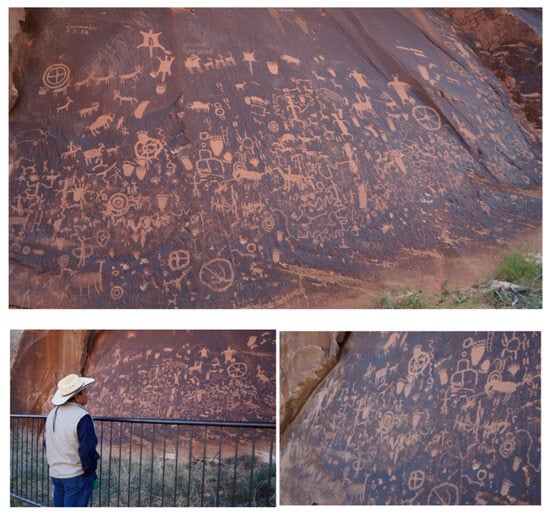

9.1. Geosite One: Newspaper Rock

The pecking location called Newspaper Rock (Figure 32) is located in the upstream portion of Indian Creek as it descends from the Abajo Mountains. Multiple peckings on a single hard rock panel are rare in the region. Native representatives interpreted the whole geosite, but they tended to focus on symbols recognized from their heritage, such as the Utes responding to the person on horseback. All agreed that this location was culturally important and connected to their ancient tribal heritages.

Figure 32.

Tribal elder interpretating Newspaper Rock, Indian Creek, Utah (source: Stoffle).

Medicinal and food plants grow in abundance at this location, and the former are especially located under the panel behind the tourist fence. The area is wet, as it is near Indian Creek, and it is surrounded by large cottonwood trees. All tribes value the plants of the area, and many especially like the cottonwood trees, which are used in ceremonies.

According to a tribal elder who interpreting the peckings:

The other ones, the circles with asterisks inside of it, some of those represent all edible flowers before they bear fruits. See that is why there is abundance here. And when you see all these associated, next to the baby footprints, it is telling us there is abundance. Especially the left handprint, see that left handprint there? Left hand is a feminine symbol. It means prosperity, it means longevity everything good is a left symbol. A right-hand symbol is completely the opposite. That means challenges. It is masculine. It also means strength or power. The left hand is everything good. Especially if you see baby footprints or handprints next to that. It is really a good story written on this side.

According to a tribal elder:

[Newspaper Rock] is saying a lot. A lot of activity going on, like hunting buffalo, deer, and bighorn sheep. A lot of it is drawn over old inscriptions. See the dark ones are underneath and the light ones are on top? See the man on the horse? I believe the most recent ones are Ute.

According to a tribal elder, “Those creatures, those represent certain dances that have happened. That is my interpretation. Probably a dance”.

According to another tribal elder:

It is a good name, newspaper, but we call them libraries of our history. Our ancestors left this information behind so that in the future, when their children, us, come back, we can identify what they left behind. I am really thankful that our ancestors had the foresight to look into their future and leave information like this behind.

One tribal elder said, “That one up there definitely has his Puha (Creation Energy) from the deer. See him, deer head? He could have been the Buckboss”.

Another tribal elder added:

The footprints and then the handprints, especially the left handprint is a very good symbol. And then baby footprints are a really good sign. There are certain styles of footprints that are modern versus ancient. The one on the left is ancient. This one I think is relatively old. See those baby foots? It symbolizes something, a very good life that they had at that time. A lot of children were born, really good crops and plenty of game, stuffs like that.

9.2. Geosite Two: Medicine Area and Doctor Rock

Along Indian Creek, a few miles from Newspaper Rock and the canyon with the peckings is an area recognized as having been used for medicine. Central to it is a large, isolated Doctor Rock (Figure 33). On one face of the Doctor Rock is a series of peckings (Figure 34). The top of the rock can be accessed through a series of steps carved into the rock, suggesting that it was where the medicine was strongest and the doctoring occurred.

Figure 33.

Acoma representatives and ethnographers at the Doctor Rock (source: Van Vlack).

Figure 34.

Close-up of two sets of peckings on the Doctor Rock (source: Van Vlack).

The Doctor Rock is tall and steep-sided. Our ethnographic interviews at other Doctor Rocks, such as at (1) Eagle Head in Escalante Valley (Stoffle et al. 2024), (2) the tonal engineered flack rock portal on the Nevada Test Site (Stoffle et al. 2024), and (3) the volcanic plug called Vulcans Anvil located in the middle of the Colorado River, Grand Canyon National Park (Van Vlack et al. 2024), provide evidence that Doctor Rocks are ceremonially used from their tops. In the case of this Indian Creek Doctor Rock, the steps to the top have been cut up one side (Figure 35). Normally, access to the top by a person with a medical or spiritual need requires them to be on the top of the rock, and they are doctored there by multiple persons.

Figure 35.

Cut Steps Extending to Top of the Doctor Rock (Source Van Vlack).

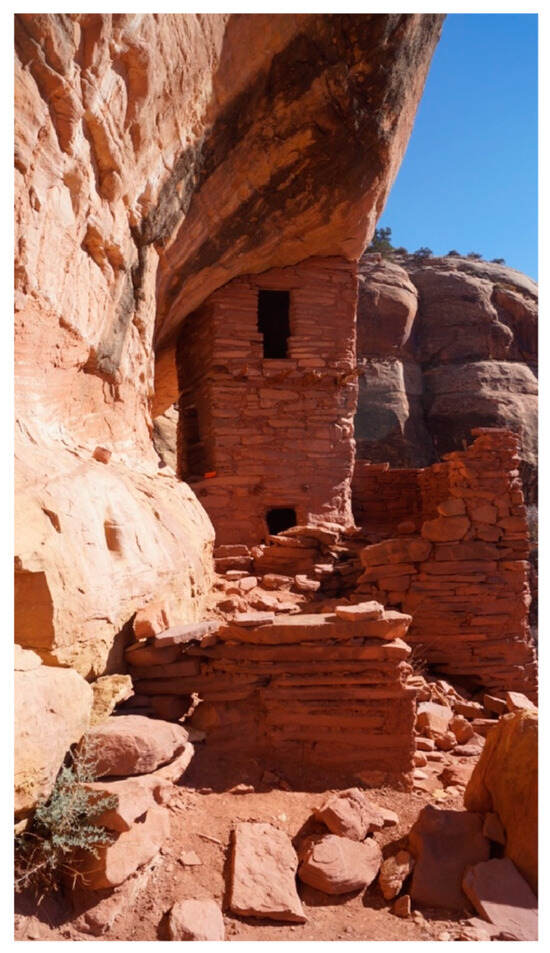

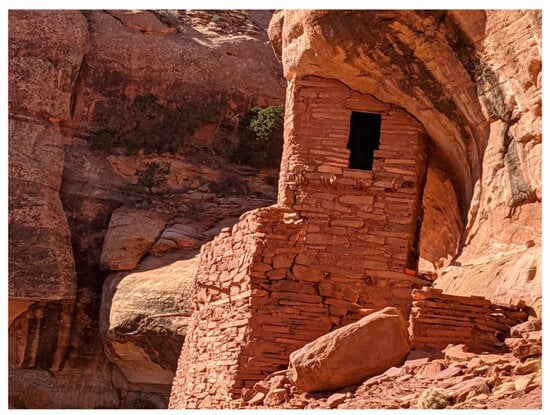

9.3. Geosite Three: Cliff Complex

Doctoring paraphernalia and a place for doctors to prepare themselves are normally near a Doctor Rock but are private and located away from any residential areas. The Indian Creek Doctor Rock has a series of multilevel towers located more than 300 feet above the valley bottom on a nearby narrow and steep cliff edge. The tribal representatives argued that this is a ceremonial area. Medical paraphernalia could have been stored here, and inside, open spaces are provided for doctors to prepare themselves for doctoring (Figure 36 and Figure 37). After doctoring, the participants required purification, and there was a spring on the ledge near the structures.

Figure 36.

Cliff structure near the Doctor Rock (source: Van Vlack).

Figure 37.

Cliff structure and spring near Doctor Rock (source: Van Vlack).

Next to the structures on the cliff face is a high smooth sandstone face on which there are a number of paintings and rock peckings (Figure 38). Some figures are painted with red pigment, others are made from white pigment, and still others are pecked into the face of the rock.

Figure 38.

Rock peckings and red painted figures next to cliff structures (source: Van Vlack).

Pueblo representatives from Zuni said during a site visit that the nearby Doctor Rock is connected with the cliff-face structures, the paintings on the high wall, and the spring on the narrow ledge of the cliff face. It is argued based on tribal interpretations that the Doctor Rock is ceremonially connected with the cliff-face complex, including the spring. The two areas are 1400 feet apart, and the cliff complex is 300 feet directly above the valley bottom. The Celestial Light Marker is six miles from these ceremonial features.

10. Heritage of Indian Creek

It has been argued based on Native American interviews (see Section 6) that Indian Creek, from its headwaters in the Abajo Mountains to its mouth where it joins the Colorado River, has been a spiritually special geoscape since Time Immemorial. A few geosites along its length have been discussed in this analysis, which is centered on the Celestial Light Marker, dance grounds, and western twin peaks. The Indian Creek hydrological system is enormously complex in terms of its topography, ecology, and Native American heritage places. In addition, some ceremonial support places that are apparently not tied to geology have been left out of this analysis to protect them from intrusion and potential damage. The road to the Canyonlands National Park has been constructed along Indian Creek, and it annually directs hundreds of thousands of tourists, including technical rock climbers and recreational campers, to the area. Our data argue that this culturally special hydrological system warrants special protection from damage or insult to preserve Native American heritage that is shared by dozens of tribes and pueblos.

An example of the range of interpretations provided by pueblo representatives is that from Acoma. At the Doctor Rock site, Acoma Pueblo representatives expressed that they felt deep connections with the Indian Creek area, interpreting it as a part of their ancestors’ sacred migration journey to their current home. While detailed symbol-specific interpretations were not provided due to cultural sensitivity issues, Acoma Pueblo representatives shared that some of the symbols on the Doctor Rock narrate the Acoma migration histories and represent landmarks of the migration journeys of the early Acoma people. They also emphasized that such places as the boulder and other similar spots within the Indian Creek area, including Newspaper Rock, are alive, as they are able to remember stories and names that were and are told to them. The Acoma people thus still visit these places of rocks, canyons, and rivers in their dreams and prayers and, to this day, speak to them as is appropriate for communication with living beings.

11. Discussion

The concern for knowing about space and time has been culturally central for all the Native American tribes and pueblos while they were living in the Mesa Verde World and, subsequently, for their ancestors wherever they live today. This is a cultural fact borne out by every annual ceremony of each Native group today. Of the hundreds of interviews conducted during this research, no tribe disputed the notion that they look to the solar system to understand time and, subsequently, structure their scheduling of which behaviors and ceremonies should occur.

Participating tribal representatives generally agreed that during the peak of the Mesa Verde World period, people were subject to the advice and control of a powerful religious elite. They supported this elite by moving their homes near Big Houses and collectively participating in ceremonies there to balance the world, which was becoming less predictable. However, the droughts became longer, and the rains fell at the wrong times. The weather changed but generally became colder and dryer. During the 1200s AD, these communities were entering what is now called the Little Ice Age, and the productive agricultural surplus that supported a stable way of life was coming an end. During 70 years in the 1200s, at Hovenweep, the religious elite worked together to once again achieve control over the balance of the universe, but by 1270, a long drought would cause their citizens to lose faith and stop supporting them.

Interestingly, today, these Native people continue to believe in the epistemological principles that guided their balancing behaviors for hundreds of years during the Mesa Verde World period, but now performances of balancing ceremonies are primarily accomplished in local kivas by groups of experts with special knowledge. The power of the religious elite ended, and they never reemerged, but ancient Native understandings of the universe persisted.

Without a central coordinated religious body of specialists but with a common epistemological theory that they could affect massive worldwide change, up to 32 Native tribes coordinated during two cultural movements to balance the world (Stoffle et al. 2000). These were the 1870 and 1890 Ghost Dance movements. It is not clear whether or not the Indian Creek Celestial Light Marker contributed to ceremonies associated with these movements, but there is evidence of a Ghost Dance ceremony occurring in Indian Creek near the Celestial Light Marker.

The World According to Pimm and Tribal Elders

For more than a year, Richard Stoffle served on a committee on Marine Protected Areas appointed by the National Research Council (NRC 2001), which provided an opportunity to work with the ecologist Stewart Pimm. During their frequent meetings, Pimm was observed rapidly reviewing hundreds of ecology research proposals for the National Science Foundation and manuscripts for science journals. His speed was impressive, and he explained that scholarly research in ecology was regularly limited by myopia, where (1) the scholar selects too few species or natural variables for study when the explanation of a phenomenon involves more key missing ones and (2) the scholar selects an overly narrow temporal frame when what is being studied happens over longer time periods.

With the perspectives from his book The World According to Pimm (Pimm 2001) and his earlier work (Pimm 1991), we continued discussions about the structure of research at the NRC meetings. It became clear that similar limits occur in Native American heritage research. Studies by Tilley (1997, 2004), including Phenomenology of Landscapes: Places, Paths, and Monuments, were also instructive in our development of landscape interviews. Pimm’s biology and Tilley’s archaeological methods suggested ways to better listen to and explain the interpretations of tribal elders participating in studies. With the advice of tribal elders, a Native American cultural landscape data collection form was produced (See Supplementary Material). In response to their recommendations, our landscape interviews now always use large paper maps to mark the broader ideas of what we now call geoscapes. The cultural value of places was not lost in this process; instead we began writing about what Native elders define as the functional interrelations between living places in the formation and operation of geoscapes.

Although our research team has authored articles and more than a dozen ethnographic reports, a problem of credibility persists among federal land managers. Western-trained scientists have had personal and scholarly difficulties accepting as either true or real what Native elders have said about the land, animals, plants, and living stone portals as elements of a Living Earth. With other scholars, we began to frame this as an epistemological divide. Such barriers in environmental communication (Sjolander-Lindqvist et al. 2022) are not easily understood, and almost never do the two cultures agree that the opposing view is fully correct. At best, however, the two views can be placed side by side and given equal credit in environmental interpretation and management. Some U.S. federal agencies call this cultural multivocality.

A major difficulty in environmental communication is that Western-trained scholars and managers are taught to believe what they can see and systematically document. Native elders work with knowledge that is ancient, and it has been tested over great periods and with many variables considered. This is the foundation of Native Science (Johnson and Aldridge 2024; Stoffle et al. 2024). Western-trained scholars term Native Science a matter of faith, and some ancient knowledge does become embedded in religious practices. Still, Native Science cannot persist unless it provides accurate explanations of nature and does so for great periods of time. The religious elite of the Mesa Verde World were no longer supported when the weather continued to change, even though the fundamental beliefs of the people persisted. Native people in the region shifted their lifestyles from primarily depending on agricultural production to a mixed economy that relied on wild fauna and flora, horticultural management of semidomesticated plants, and agriculture where it was possible. No one uses medicine that does not work, so a Doctor Rock that does not heal becomes empty and unused.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/arts14020025/s1.

Author Contributions

R.S. was senior Principal Investigator on the Arches NP, Canyonlands NP and Hovenweep NM studies. K.V.V. is the Principal Investigator for the MFO project and served as the Principal Investigator for the Moab Ethnographic Study. H.L. served as key research personnel on the projects. All three helped write, edit, and fact check during the production of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

Funding for the referenced research projects were provided by the National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Angelbeck, Bill, Chris Springer, Johnny Jones/Yaqalatqa, Glyn Williams-Jones, and Michael C. Wilson. 2024. Líĺwat Climbers Could See the Ocean from the Peak of Qẃelqẃelústen: Evaluating Oral Traditions with Viewshed Analyses from the Mount Meager Volcanic Complex Prior to Its 2360 BP Eruption. American Antiquity 89: 378–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bears Ears Intertribal Coalition. 2025. Bears Ears National Monument Map. Available online: https://www.bearsearscoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/uw_BearsEars_Proclamation_8.5x11.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Bennett, Matthew R., David Bustos, Jeffrey S. Pigati, Kathleen B. Springer, Thomas M. Urban, Vance T. Holliday, Sally C. Reynolds, Marcin Budka, Jeffrey S. Honke, Adam M. Hudson, and et al. 2021. Evidence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum. Science 373: 1528–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brocx, Margaret, and Vic Semeniuk. 2017. Towards a Convention on Geological Heritage (CGH) for the Protection of Geological Heritage. Geophysical Research Abstracts 19: EGU2017-11284. [Google Scholar]

- Brocx, Margaret, and Vic Semeniuk. 2022. Geoparks, Geotrails, and Geotourism—Linking Geology, Geoheritage, and Geoeducation. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/land/special_issues/geoparks_geotrails_geotourism (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Canyons of the Ancients. 2024. Canyons of the Ancients National Monument; Cortez Colorado: Bureau of Land Management. Available online: https://www.blm.gov/programs/national-conservation-lands/colorado/canyons-of-the-ancients (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Grayson, Donald K. 1993. The Desert’s Past: A Natural Prehistory of the Great Basin. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2024. World Commission on Protected IUCN 2024. International Union for Conservation of Nature. World Commission on Protected Areas 2021–2025. Available online: https://iucn.org/our-union/commissions/iucn-world-commission-protected-areas-2021-2025 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- IUGS. 2024. IUGS: International Commission on Geoheritage. Available online: https://iugs-geoheritage.org/ (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Johnson, Edward A., and Susan M. Aldridge, eds. 2024. Natural Science and Indigenous Knowledge: The Americas Experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, Timothy A., Mark D. Varien, Aaron M. Wright, and Kristin A. Kuckelman. 2012. Mesa Verde Migrations: New Archaeological Research and Computer Simulation Suggest Why Ancestral Puebloans Deserted the Northern Southwest United States. American Scientist 96: 146–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loubser, Johannes H. N., and Scott Ashcraft. 2020. Gates Between Worlds: Ethnographically Informed Management and Conservation of Boulders in the Blue Ridge Mountains. In Cognitive Archaeology: Mind, Ethnography, and the Past in South African and Beyond. Edited by David Whitley, Johannes Loubser and Gavin Whitelaw. London: Routledge, Taylor Francis Group, pp. 247–69. [Google Scholar]

- Muzambiq, Said, Robert Sibarani, Zaid Perdana Nasution, and Gustanto Gustanto. 2024. Geoheritage and Cultural Heritage Overview of the Toba Caldera Geosite, North Sumatra, Indonesia. Smart Tourism 5: 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Park Service. 2024. Fajada Butte: Chaco Culture National Historical Park. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/places/fajada-butte-overlook.htm (accessed on 16 December 2024).