Abstract

This article reflects on the translation of gallery space into a virtually immersive experience in an era of remote access. Curators and scholars such as Mary Nooter Roberts, Susan Vogel, Carol Duncan, Tony Bennet, Stephen Greenblatt, Judith Mastai, and Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett have discussed the myriad of ways in which the experience of culturally significant objects and sites in person has been critical to the study of art and its history. Focusing on theories of curation and display, I utilize practice-based examples from six virtual reality (VR) exhibitions produced in three different institutional contexts: the International Journal of Digital Art History’s online gallery, the European Cultural Center’s Performance Art program, and the Digital Humanities program at the University of California, Los Angeles. By documenting and analyzing the extended reality (XR) methods employed and the methodological approaches to the digital curatorial work, I address some of the challenges and opportunities of presenting objects in virtual space, offering comparisons to those faced when building physical exhibitions. I also consider how digital modalities provide a distinctly different paradigm for epistemologies of art and culture that offer greater contextualized understandings and can reshape exhibition documentation and the teaching of curatorial practice and museum studies.

1. Introduction

In September of 2019, just before the COVID-19 pandemic swept the globe, Johanna Drucker, as the featured author for the International Journal for Digital Art History’s (DAHJ) fourth issue, turned to science fiction in her article “The Museum Opens.” Writing of an imagined future for museums and archives in a digital age, she describes a world in which physical reality and current standard digital information systems (e.g., linked data, visualization, and computational analytics) are seamlessly integrated with virtual synthetic reality interfaces. While she took a skeptical stance out of ethical concern for the “spectacularization of cultural memory experience,” she was not envisioning a world in which remote access became the primary source of contact for scholars, students, and visitors alike (Drucker 2019).

In 2021 and 2022, the GLAM1 sector saw enormous growth in the use of extended reality or XR technology in arts and cultural heritage. If necessity is the mother of invention, many arts institutions and related organizations took the opportunity during the pandemic closures to learn and invest in this arena. While digital methods have long been used for preservation, over the past decade, and particularly in the last several years, they have become essential for offering remote access to cultural objects and spaces. The pandemic shifted the way museums and galleries interacted with the public, escalating their digital engagement beyond simply offering their collection databases online. For example, the Getty Villa produced an immersive digital experience for their exhibition “Mesopotamia: Civilization Begins,” which used a combination of video, 3D imaging, and story to virtually share exhibition objects. While the exhibition is now closed, the immersive experience can still be accessed at https://mesopotamia.getty.edu/ (accessed on 13 October 2024). Although the production of resources such as this can be incredibly time-consuming and expensive, they allow for the educational and exposure work of the exhibition to be extended beyond its designated run time and outside of the museum’s physical walls. They also can serve as documentation, something that has often been lacking in terms of the preservation of exhibition work.

In the era of remote access, gallery and exhibition spaces began to explore more deeply how their physical environments can be translated into a virtually immersive experience. Translation—conveying ideas across knowledge systems—has always been a core skill associated with museology and curatorial practice. In her article “Exhibiting Episteme: African Art Exhibitions as Objects of Knowledge,” Mary Nooter Roberts writes, “Exhibition making involves ‘complex dynamics of access to and translatability of different cultures’ thought systems.” (Roberts 2008). She stresses the role of narrativity in relation to exhibitions, which has been explored by scholars such as Bruce Ferguson and Mieke Bal, but acknowledges that we might not always have the same reference points (See Ferguson 1996, pp. 175–90; Bal 1996). In Nooter Roberts’ case of exhibiting African art, her point about translation was not just about understanding the visual vocabulary and grammar of an exhibition and its objects, but how curators communicate systems of thought to others who might not have the same understandings or points of cultural reference. Susan Vogel and Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett have written in detail about how the act of display changes an object (See Vogel 1991; Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1991). The manipulation of symbolic meaning through the control of the exhibition’s apparatus of installation and all of the exhibition scaffolding shapes the visitor’s experience profoundly.

Referencing her experience as a curator, Susan Vogel writes that “almost nothing displayed in museums was made to be seen in them,” emphasizing the intervention aspect of museum and curatorial work that brings objects created outside of the institution’s walls into an exhibitionary complex (Vogel 1991, p. 191). Grouped together, artifacts take on new meanings. She suggests that “An art exhibition can be construed as an unwitting collaboration between a curator and the artist(s) represented, with the former having by far the most active and influential role,” due to the interpretive nature of the curator’s job (Ibid). The way in which knowledge is presented is part of the overall power structures that shape societies. Curators often become bridge builders working within hegemonic structures and translating histories for the masses, and their epistemological frameworks have the power to shape ideologies and norms for the general public that wander their halls.

Curators began applying these valuable skills with new urgency to virtual programming, virtual exhibitions, and virtual art markets during the pandemic shutdowns. Online programming, like Virtual MOCA or VMOCA, was produced with families in mind, so that people could still have cultural experiences while maintaining safe distancing practices.2 Even though MOCA eventually reopened, the Virtual Studio Visits and various lecture series remain accessible through the VMOCA webpage. The digital content remains useful for reaching audiences that may be searching for specific thematic content for research or examples for classrooms. In addition, new forms of curatorial practice and display emerged with the use of WebVR technologies. For example, the German gallery Peer-to-Space has been bringing together curators, artists, and virtual reality builders to produce virtual exhibitions using the Mozilla Hubs platform.3

From immersive tours, to webinars, to the rise of non-fungible tokens (NFTs), the interface between art institutions and audiences is more diverse and digital than ever.4 As a result, curators, scholars, educators, artists, and related staff have had to learn and adapt to a rapidly changing landscape and often unfamiliar terrain. As GLAMs move forward, how much of this experimentation will continue and what have we learned from the process? In this article, I reflect on the translations of gallery space in an era of remote access. The curation, display, and visitation of culturally significant sites has always been critical to the study of art and its history. By sharing recent work, I will address some of the challenges and opportunities of presenting objects in virtual space based on my own experience building virtual reality exhibitions.

Focusing on theories of curation and display, I will utilize practice-based examples from six virtual reality (VR) exhibitions produced in three different institutional contexts: the International Journal of Digital Art History’s online gallery, the European Cultural Center’s Performance Art program, and the Digital Humanities program at the University of California, Los Angeles. By documenting and analyzing the extended reality (XR) methods employed and the methodological approaches to the digital curatorial work, I will address some of the challenges and opportunities of presenting objects in virtual space, offering comparisons to those faced when building physical exhibitions. I also consider how digital modalities provide a distinctly different paradigm for epistemologies of art and culture that offer greater contextualized understandings and can reshape exhibition documentation and the teaching of curatorial practice and museum studies.5

2. Expanding Epistemological Paradigms in Digital Curatorial Practice

The translation of gallery spaces into virtual environments does more than simply offer a new medium for curatorial practice—it challenges the foundational epistemologies of art and culture. Historically, the curation of art has been grounded in physical space, with the museum or gallery acting as the primary context through which knowledge is organized and disseminated. This physicality is integral to the construction of meaning in art objects, as the placement, lighting, and spatial relationships between works all contribute to the narratives constructed by curators (Ferguson 1996, p. 181). However, with the advent of digital exhibitions, we encounter a distinctly different paradigm of knowledge production that has the potential to radically reshape how art is understood, studied, and taught.

Digital curatorial practices invite us to reconsider the boundaries of art interpretation and historical narratives. This shift aligns with the ideas of cultural theorists like Walter Benjamin, who famously questioned the “aura” of art in his essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Benjamin argued that the aura—the unique presence and authenticity tied to an artwork’s original context—diminishes when reproduced (Benjamin [1935] 1969). In the digital age, this notion is tested further, as virtual curations are not mere reproductions but immersive, often reimagined, spaces where context is fluid, and art is no longer bound to physical constraints.

Rather than detracting from the artwork’s meaning, digital exhibitions can offer expanded epistemological frameworks that enrich our understanding. For example, in the virtual gallery space, curators can present multiple contexts simultaneously, allowing for a more pluralistic and layered interpretation of artworks (e.g., multiple virtual installations with the same digital objects). This directly challenges the traditional museum model, where curatorial authority and fixed interpretations dominate.6

Moreover, digital curations can facilitate more inclusive and expansive epistemological frameworks by integrating diverse perspectives that may be constrained by the logistics of physical exhibitions. This aligns with the work of art historians such as Mary Nooter Roberts, who emphasizes the role of curators as translators between cultures and knowledge systems (Roberts 2008, p. 172). In a digital context, this role of translation becomes even more complex and dynamic. The flexibility of virtual exhibitions and public accessibility of the digital platforms used in creating them allows for different types of curators from various cultural and social backgrounds to participate in the curatorial practice, thereby offering alternative epistemological viewpoints that challenge the hegemonic narratives often perpetuated by traditional institutions.

The epistemological shift brought about by digital curating also has implications for how we understand historical narratives in art. The spatial and temporal fluidity of virtual galleries allows curators to disrupt linear historical progressions, offering instead a more fragmented or rhizomatic approach to storytelling. This resonates with Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s concept of the rhizome, where knowledge is seen as non-hierarchical and interrelated across multiple entry and exit points (Deleuze and Guattari [1980] 1987). In a virtual exhibition, curators can more easily present artworks (if digitized) from different periods, geographies, and media in conversation with one another, breaking down the traditional silos of art history and fostering new interpretations that are more reflective of the interconnectedness of global culture. The practical hurdles that take immense time, effort, and expense (e.g., securing loan agreements and insurance for the works, working with registrars to ensure the safety of the objects in transport and installation) are no longer relevant. Instead, curators need only to consider if the use of the object falls under fair use, a creative commons license, or copyright.

Additionally, digital exhibitions afford curators the opportunity to engage with the inherent variability of digital media. Digital curations are increasingly mutable—they can be updated, reconfigured, or expanded over time, often in much quicker and less costly ways than physical installations. Curators must consider the implications of this flexibility on how art is preserved, interpreted, and understood in the long term. In this sense, digital curations can be seen as living documents, constantly open to reinterpretation and renegotiation. How often and what drives these decisions will become of increasing importance.

Virtual exhibitions and digital curation intersect profoundly with notions of permanence, preservation, history, and memory. In her book When We Are No More: How Digital Memory Is Shaping Our Future, Abby Smith Rumsey delves into how the digital age is transforming the way we store, access, and interpret knowledge, raising critical questions about the longevity and authenticity of digital memory (Rumsey 2016). Virtual exhibitions, as a form of digital curation, embody these concerns by shifting how cultural artifacts are preserved and experienced. In contrast to traditional museum displays, where objects are subject to time and physical deterioration, digital curation offers the possibility of indefinite preservation through replication and digitization. However, Rumsey argues that digital memory is fragile, as it relies on constantly evolving technologies and platforms that may become obsolete.7 This directly ties to virtual exhibitions, where questions of preservation, access, and technological dependence come into play—will future generations be able to access these digital spaces in the same way?

In addition, Rumsey’s exploration of how digital memory is reshaping our understanding of history and identity aligns with the opportunities and challenges presented by virtual exhibitions. In digital spaces, curators can recontextualize objects, creating dynamic, increasingly multilayered narratives that challenge static, traditional interpretations of cultural heritage. Yet, as Rumsey notes, this abundance of digital information can also lead to a sense of impermanence or overload, where critical historical context might be lost amidst rapidly proliferating digital content. Virtual exhibitions, therefore, are not just a tool for broadening access to art and history, but also a reflection of the larger existential questions about how humanity will archive, recall, and interpret its cultural memory in an increasingly digital future.

2.1. Translation Between Physical and Digital Spaces: Rethinking Spatial and Temporal Dynamics in Digital Exhibitions

The translation of art from physical to digital spaces involves far more than mere replication of objects in a virtual environment—it calls for a fundamental rethinking of how space and time are configured in exhibitions. Traditionally, the physical gallery space has played a pivotal role in framing the viewer’s experience of art. As emphasized by curator and cultural theorist Bruce W. Ferguson, the materiality of walls, the architectural flow of rooms, the placement of objects, and the physical proximity of the viewer to the artwork all shape the curatorial narrative (Ferguson 1996, p. 181). However, in digital exhibitions, these spatial dynamics are dramatically altered, giving rise to new opportunities and challenges for curators.

In the digital realm, the concept of space itself takes on a fluid and often boundless quality. Where physical galleries are constrained by walls, floor plans, and finite room dimensions, virtual exhibitions operate within what appears to be an infinite space. This capacity for endless expansion presents both liberating possibilities and curatorial dilemmas. For instance, digital spaces allow for the arrangement of artworks without concerns for physical limitations like crowd control, building codes, or even gravity. In Mozilla Hubs, for example, curators can arrange objects floating in mid-air, alter the scale of artworks in ways that would be impossible in real life, or create multiple pathways through an exhibition, inviting visitors to explore a non-linear narrative. This flexibility opens up a realm of creative possibilities that allow curators to experiment with innovative exhibition designs that might challenge traditional notions of curation.

The shift from physical to digital space also has significant implications for the visitor’s spatial experience. The virtual gallery can simulate an immersive environment, but it is not bound by the limitations of physical perception or bodily movement. Visitors can “fly” through spaces, teleport between rooms, or zoom in on artworks in ways that transform their interaction with the material. This dynamic alters the role of the body in experiencing art. In a physical gallery, the body’s navigation through space, the time it takes to walk between objects, and the effort required to examine details of a piece all contribute to the experience. In contrast, the digital environment compresses these physical limitations, allowing viewers to move rapidly, instantaneously altering their position and perspective. As cultural theorist Michel Foucault notes in his concept of “heterotopias”, spaces can be “other” in that they juxtapose multiple, often contradictory, realities (Foucault 1984). The digital space becomes a heterotopia par excellence, where art, time, and space are continually reconfigured, offering a kind of disembodied experience that challenges traditional curatorial strategies centered on the embodied visitor.

Furthermore, the digital translation of art opens up possibilities for curators to challenge the notion of liveness. In physical exhibitions, the concept of “liveness” refers to the immediacy of the viewer’s presence in the same space as the artwork, especially in performance art or time-based media. Scholars like Brian O’Doherty, Peggy Phelan, Jon McKenzie, and Diana Taylor examine artists who are exploring their own sets of questions about art and unspoken assumptions about how art is made, shown, or experienced (O’Doherty 1996; Phelan 1993; McKenzie 2001; Taylor 2003). As these scholars suggest, the experience of art in a physical space can emphasize the ephemeral and fleeting nature of certain works, heightening the viewer’s awareness of time and place.

In virtual exhibitions, liveness is reinterpreted. Live elements, such as real-time interactions with avatars or streaming performances, create a sense of presence, but the viewer’s experience of liveness is mediated through screens and digital interfaces. The digital environment allows curators to experiment with delayed or looping presentations, blending live elements with pre-recorded material, which raises questions about the authenticity of the experience. In digital curations, liveness becomes a construct, one that can be manipulated to offer new forms of engagement while simultaneously problematizing traditional notions of presence and immediacy.

The translation from physical to digital space also raises important questions about the meaning of site-specificity. Many artworks are created with a particular physical context in mind, where the site itself—whether it be a gallery, an urban space, or a natural environment—contributes to the work’s meaning. In translating these works to a digital format, curators must grapple with how to preserve or reinterpret site-specificity in a virtual context. While some artworks may lose a significant portion of their meaning when divorced from their intended site, others may gain new meanings when recontextualized in a digital space. For example, the artwork’s relationship to the digital architecture, the interactions it allows with virtual visitors, and the environmental simulations within the virtual space all contribute to new layers of interpretation. Here, we can reference Henri Lefebvre’s theories of the production of space, where space is seen not as a neutral backdrop but as something actively produced and shaped by social, cultural, and political forces (Stanek 2011). In digital curation, space is indeed a product of design and code, and its meaning is continuously negotiated between the curatorial intent and the viewer’s experience.

2.2. Artifacts Gaining New Meaning in Digital Spaces: Recontextualization, Curatorial Authority, and User Experience

One of the most profound transformations that occurs when artifacts are presented in both digital and physical spaces is the way they take on new meanings. Curators are working within an art market or system of art. Scholar and museum professional Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett writes about how the perception of objects changes as they are moved through this process and make their way into an exhibition display (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1991). The authoritative act of selection by a curator for this purpose of display bestows a higher level of significance on objects. In what ways is meaning-making of objects being shaped by digital spaces, and how might it differ from the traditional curatorial process in physical exhibition spaces, particularly in terms of accessibility, audience interaction, and the mediation of cultural or historical narratives?

In a physical gallery, curators carefully orchestrate the arrangement, lighting, and proximity of objects, creating a controlled environment that influences how viewers interpret the works. Like physical museum and gallery spaces, the digital space is not simply a neutral vessel for the display of objects; rather, it is an active participant in the recontextualization of artworks, shifting how they are perceived and understood. The digital environment, however, alters the curatorial framework in ways that allow for even greater manipulation of meaning.

In traditional curatorial theory, the context in which an artifact is displayed is central to its meaning. Susan Vogel, Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, and Mieke Bal, for example, have written extensively about how objects in museums often undergo a transformation when removed from their original context and placed in an exhibition space (Vogel 1991; Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1991; Bal 1996). This phenomenon is amplified in the digital realm, where the artifact is not just removed from its original setting but is often reconstructed, resized, or reimagined entirely. In a virtual exhibition, curators have the freedom to alter the scale of objects, change their placement within the virtual environment, or even animate them, allowing the artifact to be experienced in ways that would be impossible in physical space. These digital manipulations can imbue the artifact with new symbolic meanings or increase its aesthetic effects, as its relationship to the surrounding digital architecture and other exhibited works becomes more fluid.

For example, a sculpture that might be confined to a plinth in a physical gallery can float in mid-air in a digital exhibition or be viewed from angles that would be impossible in a real-world setting. This recontextualization shifts the viewer’s perception of the object, creating a new interpretive framework that alters the artifact’s historical, cultural, or symbolic meaning. The virtual space thus acts as a kind of palimpsest, where layers of meaning can be added or erased, depending on the curatorial choices. This opens up new possibilities for engaging with artifacts, but it also complicates the interpretive process, as the original meaning of the artifact may be obscured or overshadowed by the curatorial interventions.

Finally, the digital environment’s potential for variability introduces a new layer of meaning to artifacts. Unlike physical exhibitions, which are static and fixed in time, digital exhibitions can be continuously updated, reconfigured, or expanded. This fluidity allows curators to experiment with new interpretations over time, adding or removing elements as the exhibition evolves. As a result, the meaning of the artifact is not fixed but dynamic, subject to ongoing reinterpretation as new contexts, technologies, and narratives emerge. This variability aligns with Jacques Derrida’s concept of différance, where meaning is always deferred and never fully realized (Derrida 1982). In the digital space, artifacts are always in a state of becoming, with their meaning continually shaped and reshaped by curatorial choices, technological advancements, and viewer interactions.

The inherent fluidity of digital exhibitions also allows for an unprecedented degree of adaptability. Curators can respond to new developments in the art world, add new works to the exhibition, or adjust the narrative in response to user feedback. This adaptability introduces a dynamic aspect to curatorial practice that is not typical in traditional exhibitions. In this sense, digital exhibitions are never truly complete; they are living, evolving spaces that can grow and change over time.

This flexibility in both user experience and narrative structure introduces new opportunities for curators to explore themes of variability, impermanence, and change. In digital exhibitions, curators can embrace the ephemerality of the medium, acknowledging that the narrative is not fixed but constantly in flux. This dynamic approach to curation challenges the traditional museum’s emphasis on permanence and stability, offering a more fluid and experimental way of engaging with art.

At the same time, curators must remain mindful of the potential risks that come with this variability. The open-ended nature of digital exhibitions can make it more difficult to maintain a coherent narrative or ensure that visitors take away key messages. Without careful design and thoughtful use of interactive elements, the narrative can become too diffuse, leaving visitors feeling lost or overwhelmed by the multiplicity of options. Therefore, curators must strike a balance between offering freedom and maintaining a level of guidance that ensures a meaningful and cohesive experience.

By embracing the unique affordances of digital platforms—such as multi-user interaction, spatial navigation, and real-time updates—curators can create exhibitions that are more dynamic, inclusive, and responsive to the evolving landscape of art and culture. The variability inherent in these platforms offers curators new ways to think about narrative structure and user engagement, pushing the boundaries of what exhibitions can achieve. Ultimately, digital exhibitions provide fertile ground for experimentation, where curators and visitors alike can explore new forms of interaction and meaning-making in the ever-changing landscape of virtual space.

In the following case studies, I will examine how these affordances have been utilized in specific virtual exhibitions I have created, focusing on the ways in which I have been able to use digital tools to create immersive, interactive, and accessible experiences. Each case will illustrate the distinct possibilities and challenges of digital curation, from rethinking spatial dynamics to fostering global participation, highlighting the potential of virtual exhibitions to reshape the future of art and cultural engagement.

3. DAHJ Gallery and ECC Performance Art Virtual Exhibitions

As the Director of the Digital Art History Journal Gallery (DAHJ Gallery), I implemented the use of the same technology as Peer-to-Space, which is the Mozilla Hubs WebXR platform, for our online gallery space.8 The DAHJ Gallery launched its first two VR exhibitions in 2021. In addition, I have lectured on the use of extended reality technologies for performance for the Performance Art branch of the European Cultural Center and we have opened three VR exhibitions to showcase student work from all the performance art classes. The following shares some key aspects of what I have learned while conducting this virtual exhibition work and how I have translated it into a capstone course for my digital humanities students at UCLA. I argue that not only can this methodological approach to exhibition-making help connect curatorial work with additional audiences, but it can also change the way we educate students on issues and methods of display.

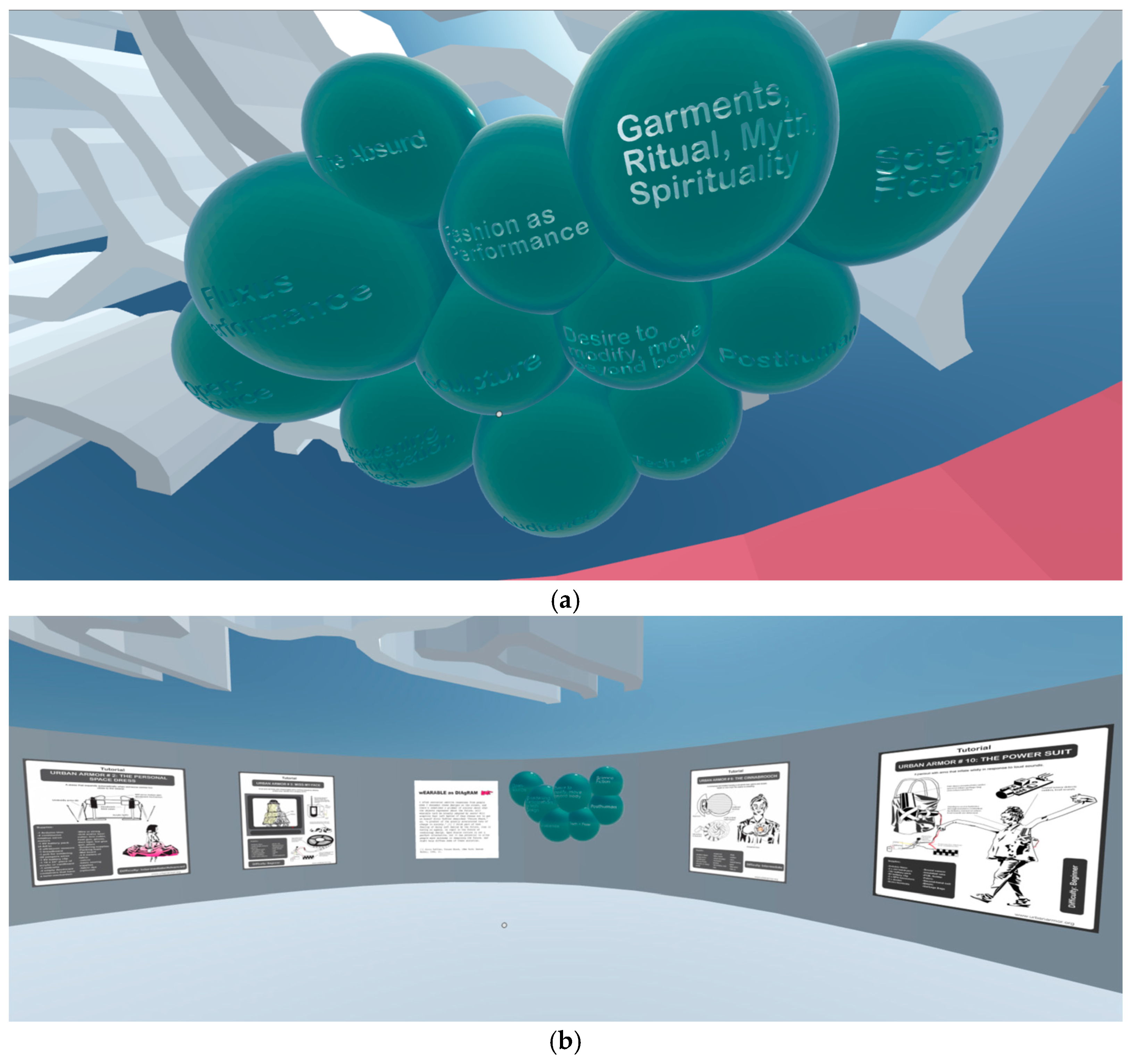

3.1. Absurdist Electronics: Wearable Coping Mechanisms, Techno-Anxiety and Thoughts on Dada

“Absurdist Electronics: Wearable Coping Mechanisms, Techno-Anxiety and Thoughts on Dada” was the DAHJ’s first virtual exhibition and the largest retrospective of Kathleen McDermott’s work to date.9 The exhibition focused on McDermott’s work with wearables, a medium which is especially well-suited to an absurdist response because the body in relation to technology has historically been subject to conflicting narratives, often limited to the utopia/dystopia binary. Taking inspiration from Dada tactics of using absurdity to blur boundaries and redirect attention, McDermott seeks to promote a more liminal conversation around the future of wearables, subverting principles of control and rationalism, which dominate commercial wearable design.

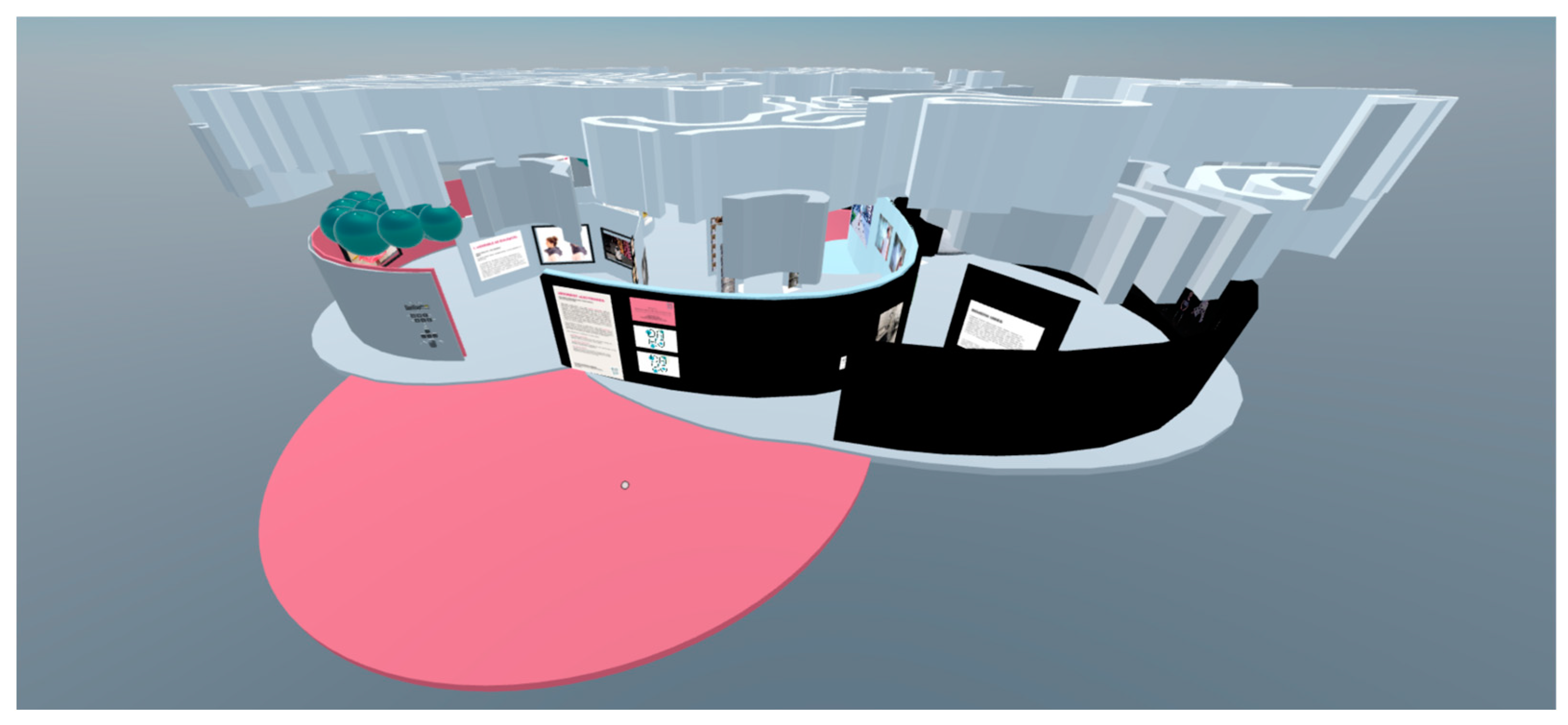

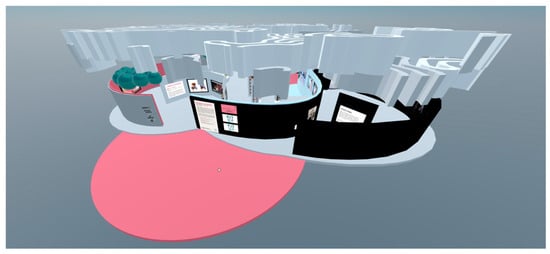

I worked closely with McDermott, who is also a professor at NYU, over several months to produce a 3D installation space which complimented the work and its ethos (Figure 1). A virtual exhibition method is well-suited for the retrospective format. Retrospectives usually involve a large number of artworks, and we could design the space to easily accommodate the over sixty works we virtually installed.

Figure 1.

Exhibition installation from an above angle.

In addition, the virtual environment made it possible to display works in a way that may have been cost-prohibitive in a physical space (e.g., GIF and video works fill the walls, which would have required monitors to hang in a typical gallery, or in another section of the installation, photographs repeated on columns in a mechanical manner, which would have been a large print order, if it were being installed in a physical space. See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

View of the repeating column installation.

We also experimented with the placement of wall labels, didactic elements, and artworks. Some wall labels were placed on the floor, and we reused a stamp from a Dadaist Manuscript of a pointing hand to direct visitors to the referred work (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

View of the exhibition object label placed on the floor.

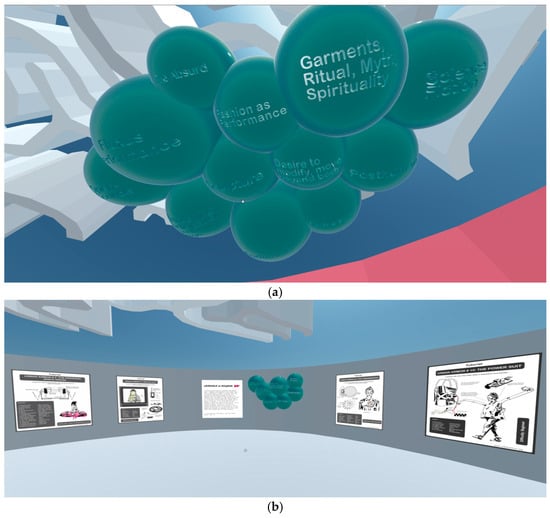

I turned diagrams of McDermott’s into globe structures, which hung above visitors in one area and emerged from the wall in another (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 4.

These images show the installation of the dimensional diagrams. The first view (a) shows how one was hung near the ceiling. The second (b) shows the diagram emerging from the wall.

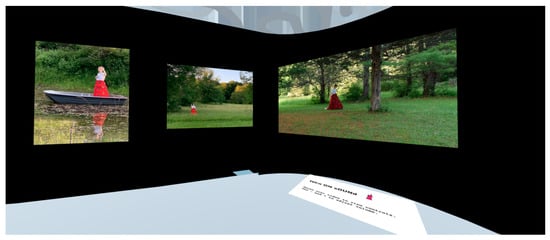

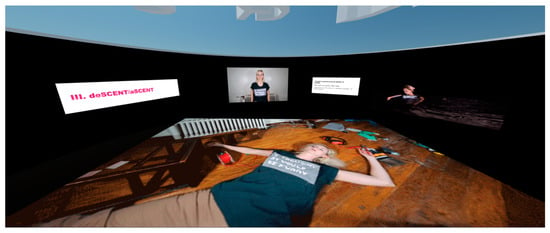

We placed one of her works on the floor in one section, echoing the subject figure of the work, who is lying on the floor (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

In one of the works in the GIF series “I thought it would be funny (an epitaph, an apology)” the artist Kathleen McDermott is lying on the floor. In the installation, that GIF file was placed on the floor of the installation space for that series.

While none of these installation methods would be new to a physical installation, they may offer more of a challenge, both in terms of cost and execution, than they presented for us within the virtual space.

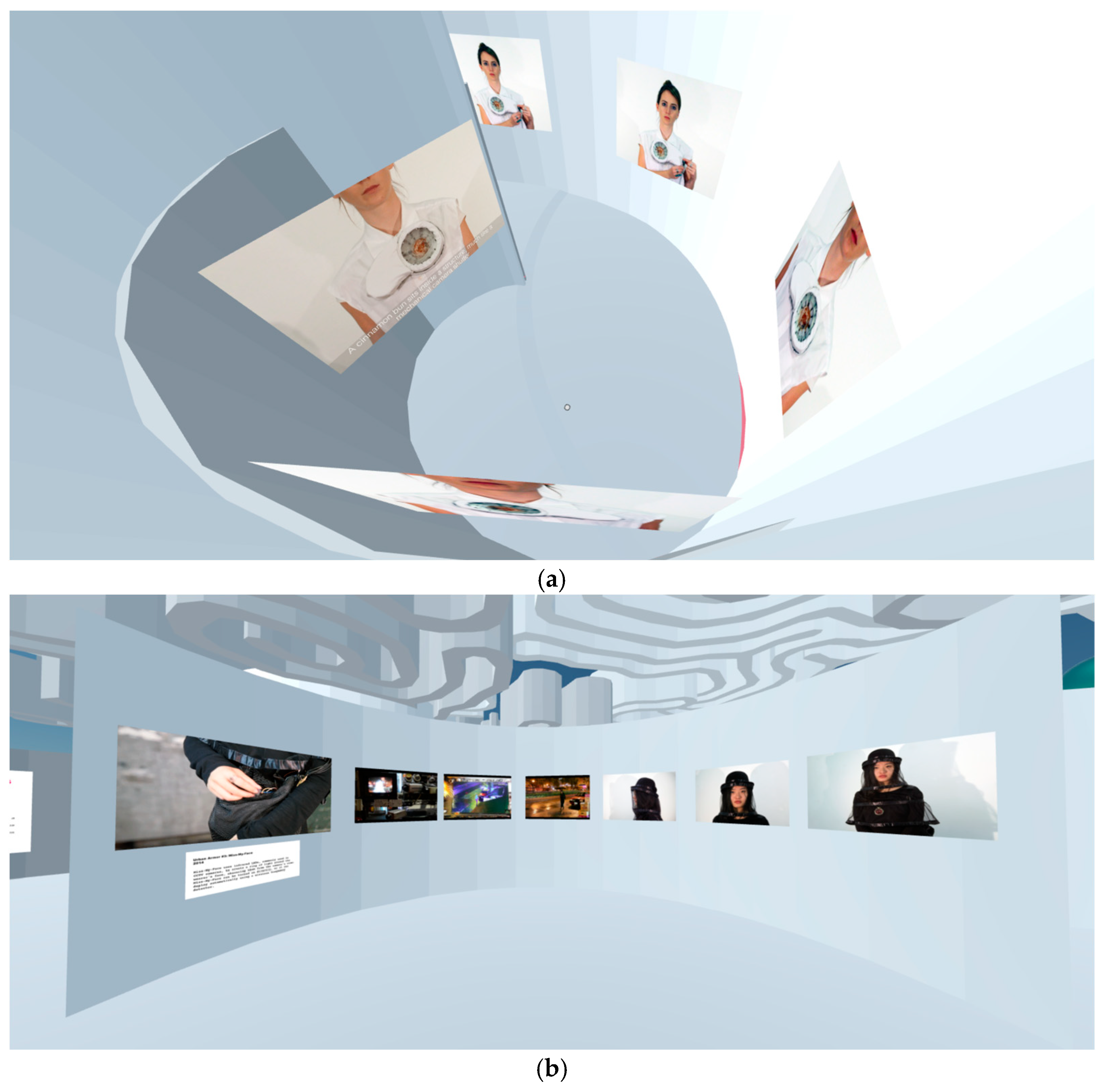

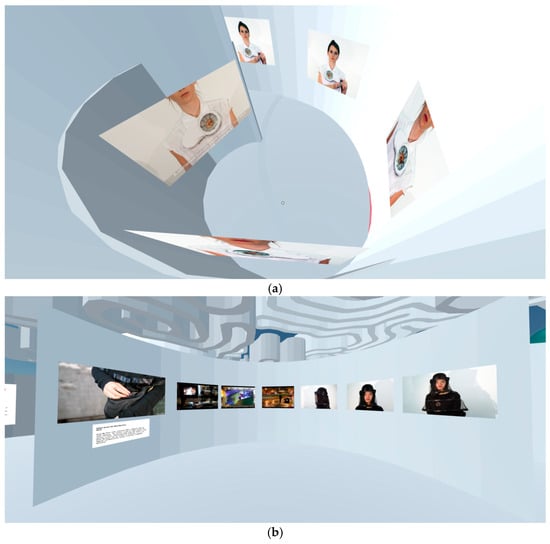

That is not to say there weren’t challenges. McDermott’s designs have many circular aspects to them, which I chose to reflect within the layout. In addition, when bringing dimension to the blueprint, I added an area with a sunken floor and a floating ceiling (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

These images show a view of: (a) the level change in the floor of the installation space and (b) the floating ceiling that was placed above.

The resulting cloud-like shape presented a challenge for installation with its curved walls and different floor levels (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

These installation views demonstrate the difficulty of placing flat file displays along curved walls. In the first image (a), the installation space designed to display “Urban Armor #6: The Cinnabrooch” mimicked the curvature of the mechanical brooch in the piece. The acute curve required some of the works to float further away from the walls. That challenge is less apparent in the installation of “Urban Armor #3: Miss-My-Face” in the second image (b), where the curve of the wall was not as severe.

Aligning digital assets with curved walls is much more difficult, making it a highly tedious process.10

Another critical element to the digital installation process is collaboration. Digital methods can allow for collaboration that might not have been able to happen otherwise or on such equal footing. Curating a physical exhibition remotely presents challenges in terms of thoroughly relaying details of the installation work (e.g., the location may not have accessible WiFi or a strong internet connection for video conferencing, the camera offers limited views, and the CAD drawing does not accurately match the current layout.) While working on this virtual exhibition, McDermott and I were able to meet biweekly over zoom for several months, and since our exhibition space was entirely virtual, we were able to review it simultaneously—examining how certain design choices looked in real time and rearrange as we needed. In this experience, collaboration could be detail-oriented when it came to installation, despite our remote status and virtually mediated exchanges. As discussed by digital art theorists like Christiane Paul, this mode of collaboration not only democratizes the curatorial process but also enhances the fluidity and immediacy of artistic production (Paul 2015). The ability to review, revise, and adjust design elements instantly—without the physical limitations of traditional exhibition spaces—enabled a much more iterative and creative curatorial process. As Beryl Graham, Sarah Cook, and Steve Dietz note in their examination of curating new media art, the fluidity of digital environments can give rise to experimental methods of display, where artworks can be recontextualized or reimagined in ways that are less feasible in a physical gallery setting (Graham et al. 2010).

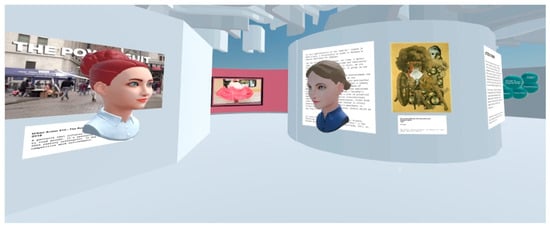

Furthermore, the digital installation was utilized to conduct an avatar artist interview within the virtual exhibition (Figure 8).11 The life of an exhibition extends beyond the placement of artworks within a designed space but encompasses the public programs that frame the key themes and central concepts to visitors. Scholars and practitioners like Mary Nooter Roberts, Judith Mastai, Janna Graham, and Shadya Yasin have highlighted the need to have community and artist involvement within the curatorial process and exhibition programming (Roberts 1994, pp. 52–54; Mastai 2008; Graham and Yasin 2008, pp. 157–72). While many have kept engagement alive through Zoom (e.g., UCLA’s ArtSci webinars12 and the MIT Open Documentary Lab lecture series13), the avatar artist interview allowed for a discussion to happen in situ.

Figure 8.

View of the virtual avatars of Francesca Albrezzi and Kathleen McDermott in the exhibition “Absurdist Electronics: Wearable Coping Mechanisms, Techno-Anxiety and Thoughts on Dada” to conduct an interview with the artist about her works.

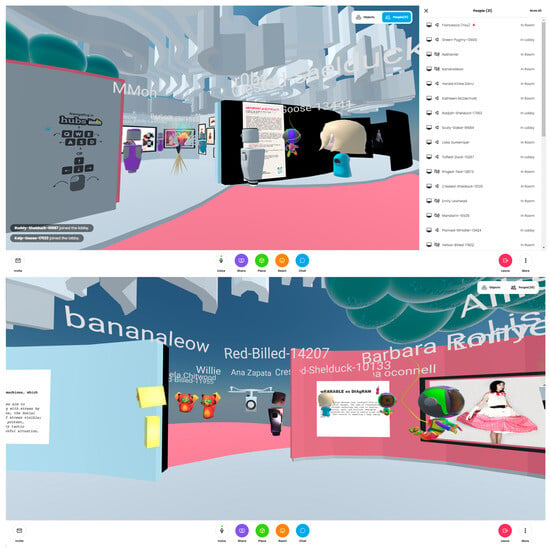

We also simulated this feeling of sharing the exhibition space with other visitors through gallery opening events. The WebXR platform used for the exhibition—Mozilla Hubs—allows for many avatars to occupy this space at once (Figure 9).14

Figure 9.

These images are from the opening reception of the exhibition “Absurdist Electronics: Wearable Coping Mechanisms, Techno-Anxiety and Thoughts on Dada” held on 24 June 2021.

Users can enable their mic to talk with other avatars in the space, and sound is spatially aware in the virtual platform. This means if a user is closer to an avatar that is talking or a video work with sound, it will be louder and if that user moves away from that object or avatar, it will sound softer and harder to hear. While users have to bring their own beverages and snacks, these virtual gatherings do provide a similar level of excitement, fun, and connection to others that would be typical for attending an in-person exhibition launch (Kenderdine and Yip 2018, p. 275).

Those involved in the making of the exhibition are able to give opening speeches to mark the occasion, and visitors are able to navigate around the space, and talk with others about the work they are viewing. These digital gatherings facilitate real-time conversations and exchanges, enabling curators to gather direct feedback from audiences, further enriching the collaborative nature of the exhibition process. The integration of spatial audio, real-time chat, and avatar interactions represents a rethinking of the role of the curator—not only as a mediator of objects but as a facilitator of dialogue and engagement within a digital ecosystem, where “authenticity vested in objects is not always solely located in their materiality.”15

3.2. Zonas de Contacto: Art History in a Global Network?

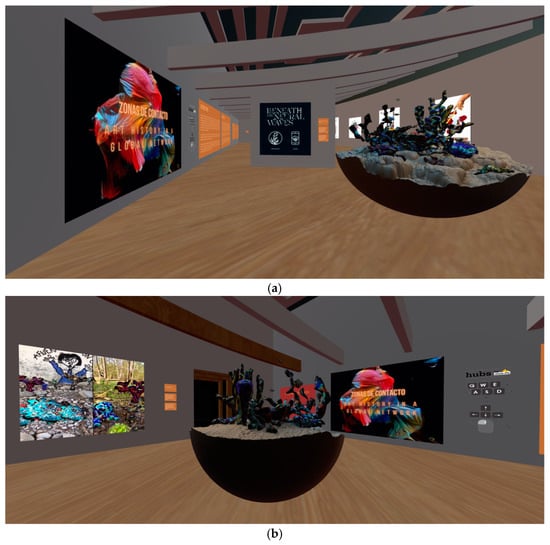

The second DAHJ VR exhibition was “Zonas de Contacto: Art History in a Global Network?” (Figure 10)16 The year 2021 marked twenty years since Mary Louise Pratt, Professor of Spanish and Portuguese Languages and Literatures, proposed the notion of a “contact zone” as a place where culture is negotiated and challenged. The anniversary became the thematic anchor for the exhibition, while acknowledging that art can bridge or destabilize disciplines and methods in ways that reframe histories and bring new insights. Still, on a global scale, there are many issues of inequality in terms of access to technology. Therefore, the exhibition’s central question was: What do these contact zones look like today? Born out of and opened in conjunction with a collaborative journal issue between H-ART17 (a trilingual journal based in Bogotá, Colombia) and the DAHJ, the exhibition addresses themes of digital art of the Spanish and Portuguese-speaking world broadly defined, including colonial histories and frontier technologies, imagined futures, post-colonial realities and networks, ongoing global or historical inequities, Latinx challenges and barriers (be they linguistic, sociological, or infrastructural), and artifacts as data or data as object. Operating as a form of praxis, the VR exhibition expands the journals’ discussions into areas of artistic production.

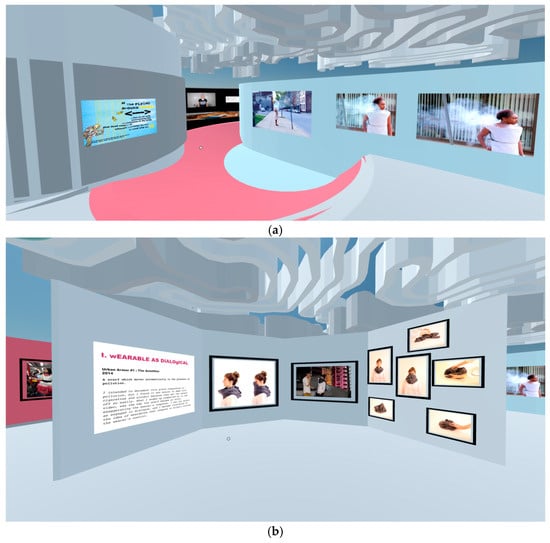

Figure 10.

These images are of “Zonas de Contacto: Art History in a Global Network?” The first (a) is the view from the spawn point of the exhibition. The second (b) is a view of the entrance area where visitors spawn into the virtual environment.

Moreover, the focus on Latinx artists and themes that challenge colonial histories reflects the broader discourse in curatorial practice about decolonization and inclusivity. Scholars such as Irit Rogoff and Mieke Bal have long argued that exhibitions have the power to reframe histories by placing marginalized voices and narratives at the center of cultural discourse (Rogoff 2006; Bal 1996). In the case of “Zonas de Contacto”, the curatorial team applied this framework by foregrounding works that engage with issues of identity, diaspora, and colonial legacies. This aligns with contemporary curatorial strategies that aim to disrupt hegemonic narratives and offer counter-hegemonic representations through exhibition themes and design (Corrin 1994).

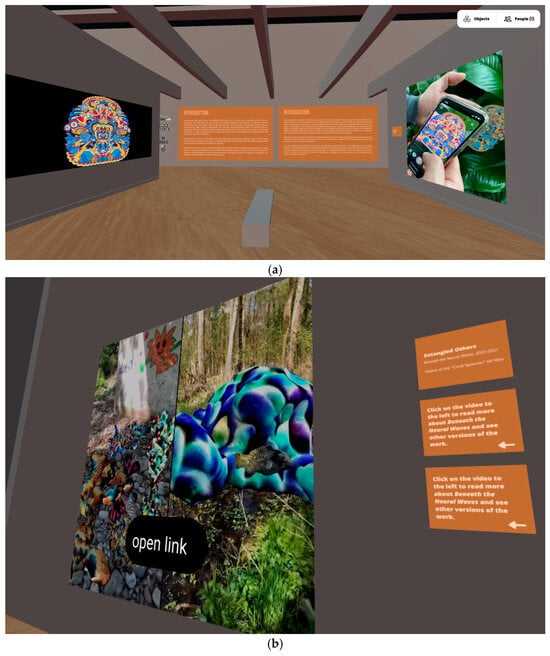

Because of the close collaboration between the two journals, everything in the exhibition was bilingual (Figure 11). Although this requires double the work, having labels in two languages greatly increased accessibility, helped us to foster inclusivity, and acknowledged the lived experience of the artists included. In curating Zonas de Contacto, the decision to embrace bilingualism was not merely a practical choice but a deliberate curatorial intervention rooted in the theory of “contact zones” as proposed by Mary Louise Pratt. Pratt defines contact zones as “social spaces where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power” (Pratt 1991). This curatorial decision not only provided linguistic access but also symbolically bridged cultural and geographic divides, reinforcing the exhibition’s theme of cultural negotiation within a global network.

Figure 11.

These images show how labels were duplicated in the environment to provide both Spanish and English access to content. In the first image (a), the exhibition introduction is in view. The second image (b) provides an example of how the bilingual labels were offered near the works. In each case, the design of the label remained the same.

Producing a bilingual exhibition was only possible thanks to my co-curator Ana María Zapata and Bárbara Romero Ferrón, who also worked on the translations. Other DAHJ staff participated as well: Emily Lawhead assisted with the creation of wall label descriptions, Justin Underhill helped with the shaping of the call for papers and the call for artists, and Harald Klinke and Liska Surkemper, the co-founders of the DAHJ, provided supportive feedback. The critical takeaway evidenced here is that the production of the exhibition was a true team effort in the same fashion as any physical exhibition.18 In terms of our process, we used Canva, a free web-based design tool, for most of our wall label designs, allowing us to quickly duplicate and keep our text looking consistent.19

By leveraging digital tools, the exhibition also sought to address issues of accessibility in ways that physical exhibitions might not be able to. As Claire Bishop notes, the digital realm offers unique opportunities for democratizing access to art, particularly for global and underrepresented communities (Bishop 2022). However, this democratization is not without its challenges. As scholars like Tara McPherson have discussed in their work on digital divides, access to the necessary technology is often uneven, particularly across socioeconomic and geographic lines, which can exacerbate existing inequalities in access to art and cultural experiences (McPherson 2012). While digital platforms can transcend geographic limitations, they also require technological literacy and access to high-speed internet—resources that are not equally available in all regions. Thus, while the exhibition aimed to create a “contact zone” through its inclusive curatorial approach, it also highlighted the ongoing challenges of digital equity, echoing broader discussions in the field about the limitations of digital spaces for truly inclusive participation (Graham and Yasin 2008, pp. 157–72). It is worth noting that only one person at a time can be logged in to Spoke, the Mozilla Hubs environment building platform, to make changes in the environment.20 For this reason, it was logical to leave the digital installation work to one person, with regular reviews of that progress to receive feedback.

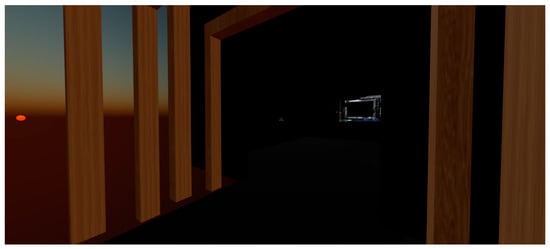

In terms of the design choices, there are some key differences from the “Absurdist” Electronics exhibition described above. The “Zonas De Contacto” exhibition scene is set at twilight instead of midday, which gives the exhibition an entirely different tone and echoes the theme of liminality that is present in the exhibition’s framing (Figure 12). This transitional space symbolizes a departure from conventional understandings of art and culture, inviting visitors to confront colonial histories and the complexities of post-colonial realities. Within this liminal environment, the exhibition becomes a contact zone where diverse narratives intersect. Visitors engage with works that reflect ongoing global inequities, Latinx challenges, and the tension between technological advancements and sociological barriers. The twilight ambiance encourages a reflective exploration of imagined futures, prompting discussions about identity and belonging in a digitally connected world.

Figure 12.

A view from the “outdoor” walkway in the “Zonas de Contacto: Art History in a Global Network?” exhibition environment that shows the twilight environmental setting. The main exhibition space is covered by a floating, open ceiling, which allows for the darkened sky to be visible.

As in theater or film, staging can change the effect of an exhibition. Adjusting light takes on a whole new dimension in the virtual space, where you are also world-building.21 In virtual reality, curators can and should consider how these environmental settings will affect the reception of the work. As visitors move through this space, they not only experience transformation but also engage with artifacts that blur the lines between data and object. This interplay emphasizes the role of digital art in addressing historical narratives and envisioning new possibilities. Ultimately, the exhibition’s liminality fosters a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness of these themes, inviting visitors to emerge with a more nuanced perspective on their own identities and the global landscape.

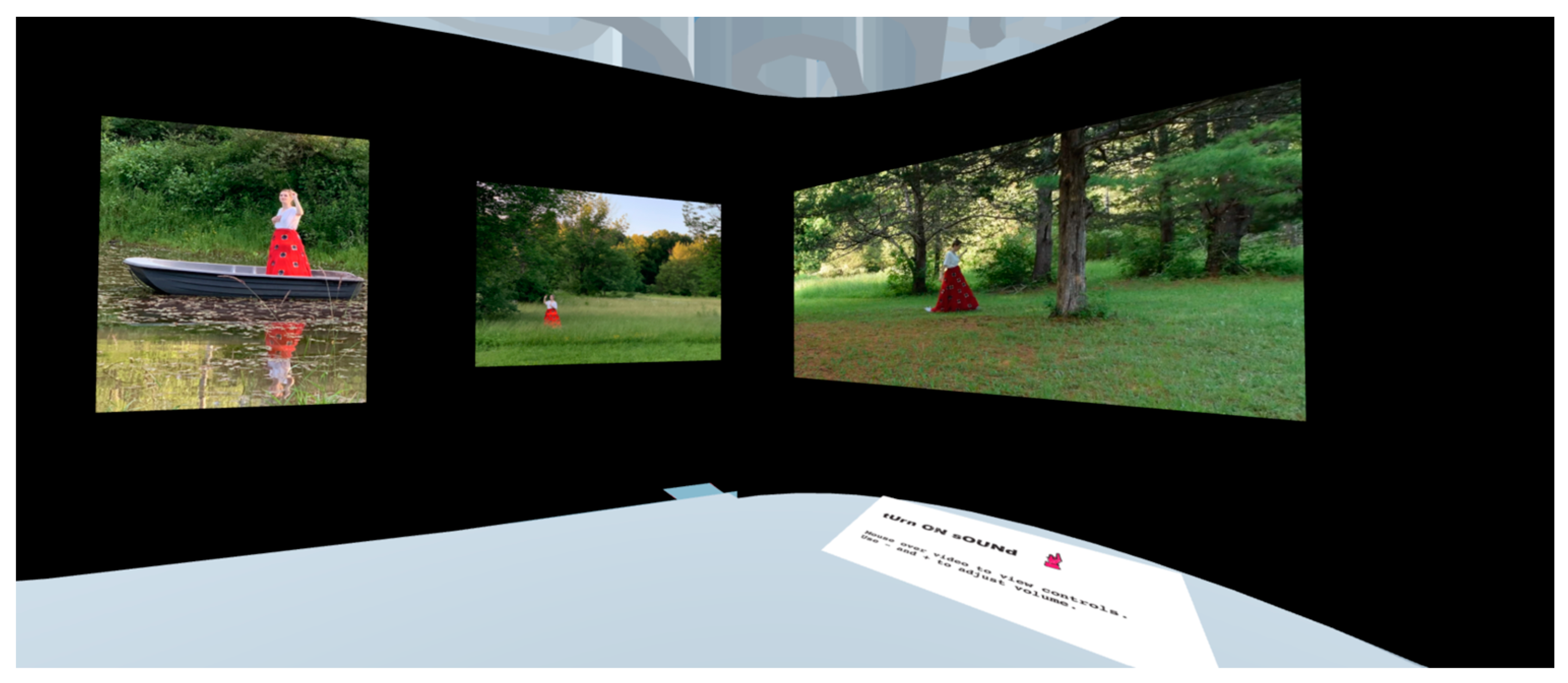

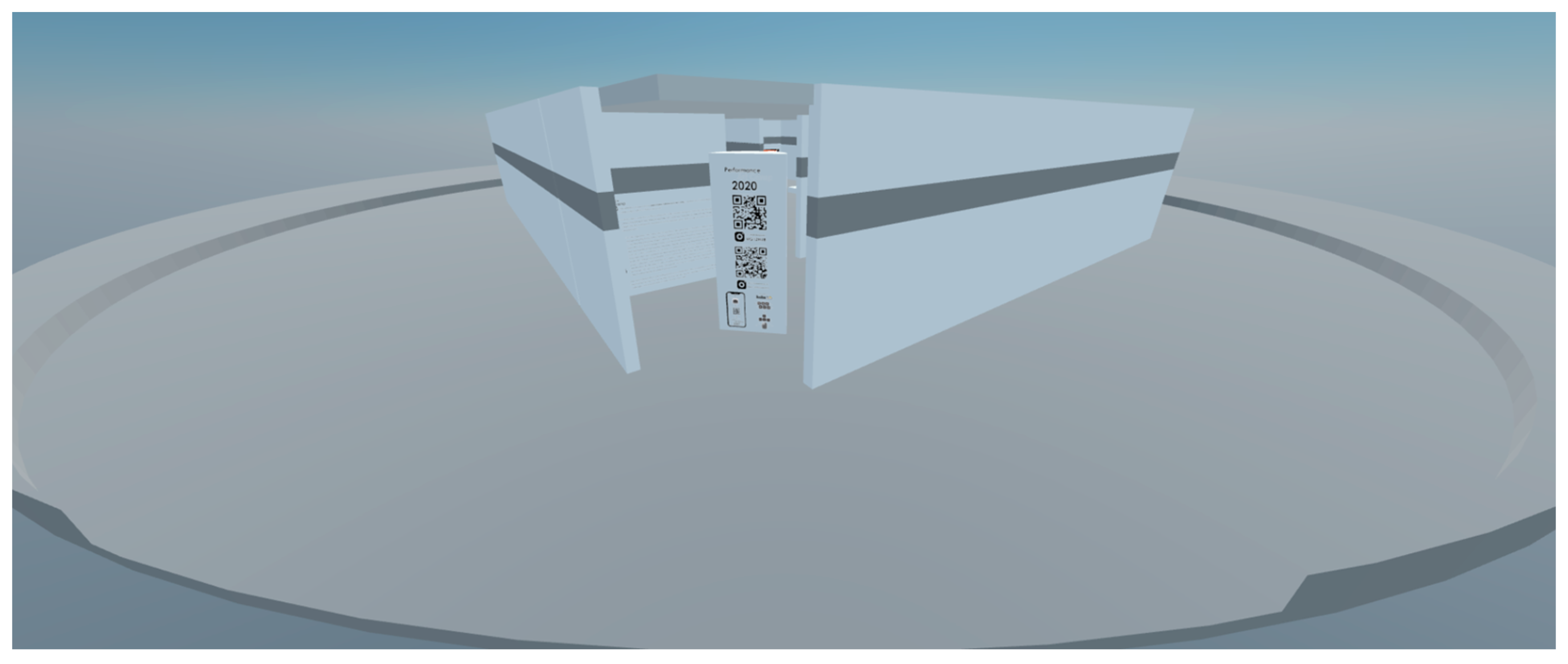

World-building has always been part of exhibition making, whether it is in the physical or virtual world. Exhibitions such as “Art/Artifact” by Susan Vogel and Mary Nooter Roberts at the Center for African Art in New York and “Mining the Museum” by Fred Wilson at the Maryland Historical Society situated the semiotics of display as a central concept22. Installation artists in particular are cued into the whole environment as a medium for their work. In “Zonas De Contacto”, we included a work by Annabel Castro called “Outside in: exile at home,” which was originally conceived as an installation of projected real time edited video within an entirely darkened room (Castro 2020). The virtual installation attempted to recreate those conditions as closely as possible by building a separate black box room for the video works (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

These images detail how the auxiliary room for Annabel Castro Meagher’s video installation “Outside in: exile at home” was incorporated into the exhibition space. The first image (a) provides a view from above, showing how the walkway extends out to the right and bridges the black box space with the rest of the exhibition. The second image (b) is a view of the two video works installed on two separate walls in the dark environment. Images (c,d) provide views from either side of the walkway to show how visitors would enter and exit the space.

Our collaborative conversations explored the possibility of programming the work so that visitors would start at a different point within the video work any time they entered; however, when loaded, the environment will start all the video-based works at the same time and there is not a way to script or code to change aspects of the space using the backend editor interface, Spoke. Instead, we were able to loop the videos and because it is set apart from the rest of the works, visitors will enter the space after the work has already started to play and the variety as to when they choose to enter that space closely mimicked the randomized start points of the original work. As exhibition work continues to expand across the reality-virtuality continuum, it will remain essential to critically examine the semiotics of display that are at play with in-person installations and consider how best to translate these works across the digital spectrum (Milgram and Kishino 1994).

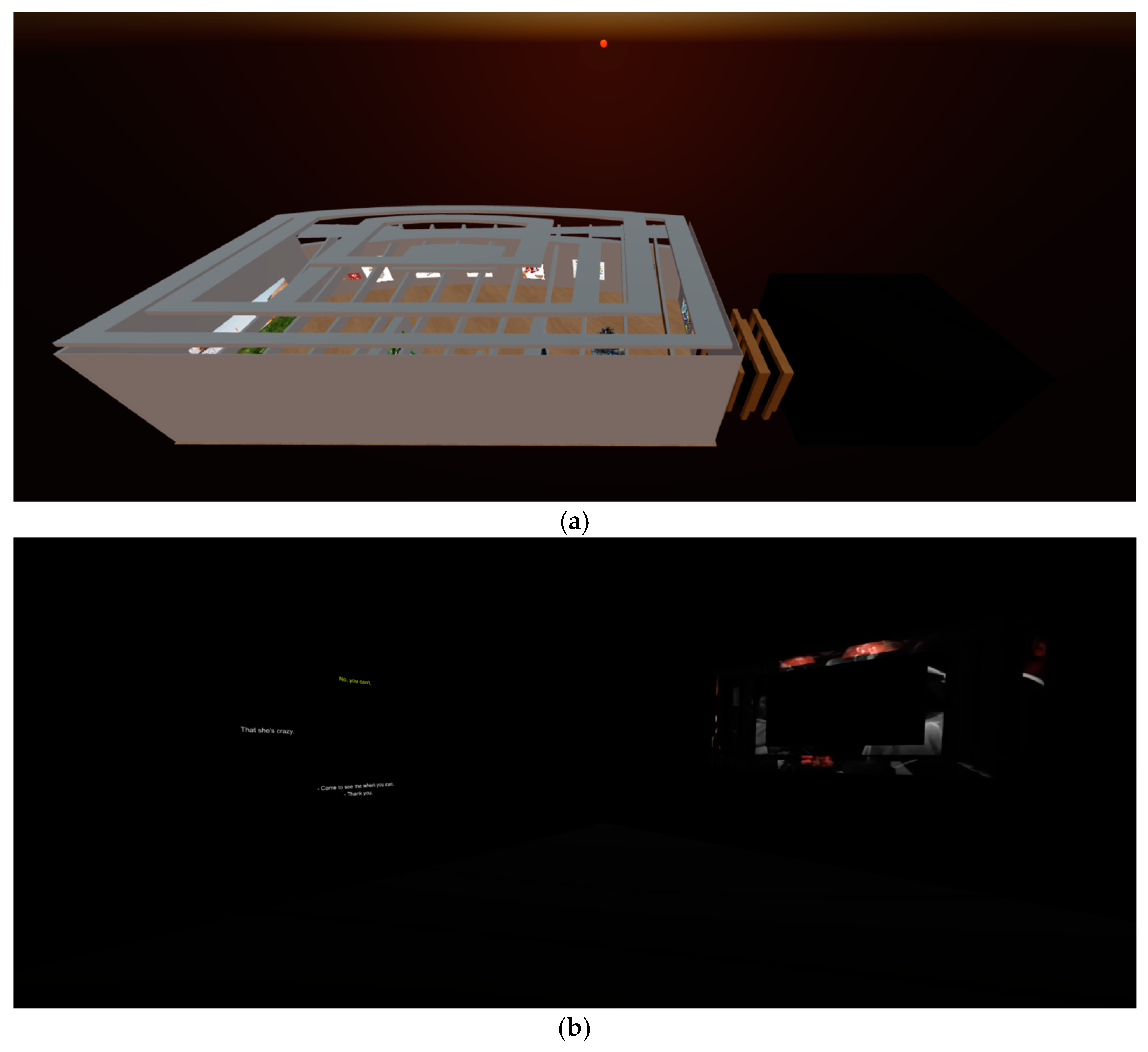

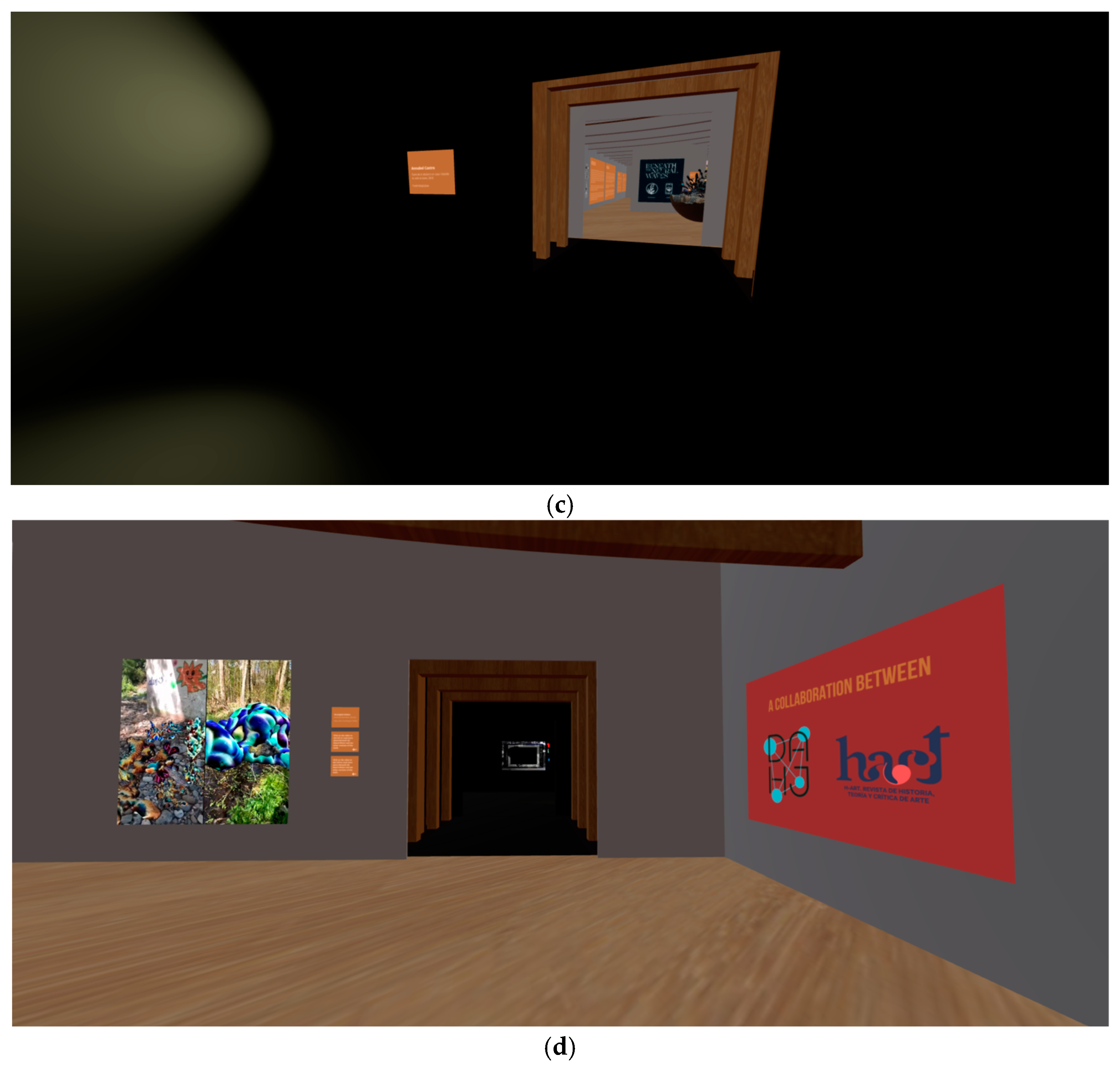

3.3. ECC Performance Art VR Exhibitions

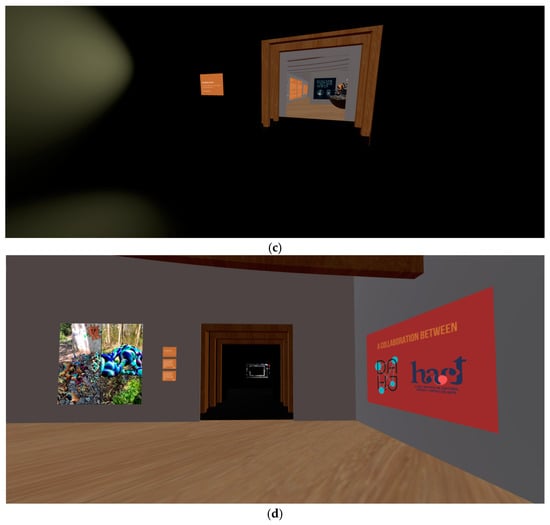

There is something to be said for not designing a custom space for every exhibition, especially for organizations that plan on showing new work fairly frequently. Such was the case for the design of a digital space for the European Cultural Center’s (ECC) online Performance Art program. Running year-round classes in which students are producing and sharing work through video conferencing, the question became: how can an online institute repeatedly showcase student work with an aspect of liveness, echoing the performance work itself? The WebXR environment provided their community with a virtual gathering space to interact in real time with the performance works and other gallery visitors.

ECC Performance Art opted for a design that was spacious and simple enough that it could be reused over and over again (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

View of the ECC Performance Art exhibition gallery space from the outside.

This approach is both cost- and time-efficient. After the initial investment, small walls or installation pedestals are added as needed to tailor the space to new work, which is not dissimilar from how many commercial and educational gallery spaces operate (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

This image is of the installation from 2021. The red arrows indicate where an additional partial wall and display platform were added, making minor adjustments to the space for this particular installation.

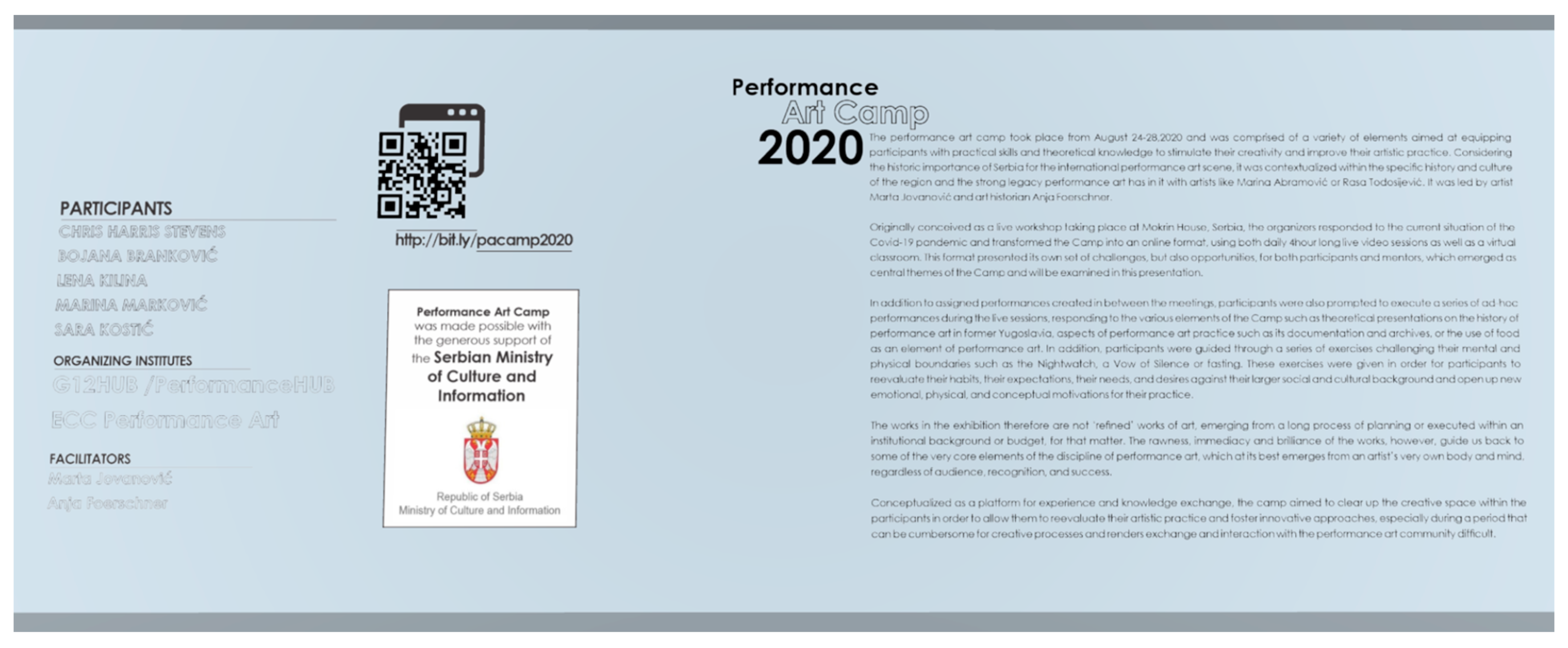

An added benefit is that after artworks have been installed in the virtual space once, the general coordinates for the position, rotation, and scale of virtual objects can be reused to cut down on the installation time of the replacement objects.23 The fourth installation in the space launched in January of 2024 with a new virtual exhibition of student performance art works, and is currently being migrated to a new platform due to the sunsetting of the Mozilla Hubs platform.

4. Lessons Learned

Virtual installations provide artists and organizations an opportunity to reach wider audiences. Digital audiences can be situated globally, but occupy the same virtual environment, providing a shared experience and live and long-term access. The crucial limitations to working in WebVR involve data rates and general familiarity with the technology. Despite substantial and rapid WebXR developments, there are several key elements to note for providing an ideal experience. While Mozilla Hubs is a platform that can be loaded in a headset or on a desktop, many people do not own headsets, so they are limited to the desktop experience. When operating in the desktop experience, it can be difficult to adapt to the navigation methods that are required to move about the space. Thus, it is helpful to place navigation directions on the website prior to visitors entering the virtual exhibition, as well as a graphic in the space that reminds people which keys they need to use with their mouse to move around (Figure 16). The graphic should always be placed within the sight line of the spawn point, or the point of arrival in the space, so people can easily see how to navigate immediately upon entrance.24

Figure 16.

Taken from the exhibition’s spawn point, this image of the ECC Performance Art exhibition gallery shows the navigation graphic outlined in red to indicate the design and placement of it. The arrows indicate the 3D graphics that appear when assets are loading in the WebXR Mozilla environment.

On the creator side, the platform only allows for assets to be loaded if they are under 128 MB. This usually means that videos will have to be compressed before they are ingested. Additionally, the more assets you have within an environment, the more likely you are to have issues with loading assets. While you can embed video and image assets from outside sources via a link, this method creates a less stable asset since it is not hosted locally and usually results in an increase of loading issues. Slow loading times result in the audience viewing multicolor boxes until the assets are rendered.

In other cases, videos can sometimes be glitchy or slow to run. Unfortunately, for older computers or users with slow or intermittent internet connections, the experience may be quite poor, if it is an extremely heavy environment—one that is rich with big files that need time and top data speeds to load well.

One solution to minimize the number of assets in the environment is to build a companion website or webpage that allows users to access artist information outside of the exhibition environment (Figure 17). Many exhibitions today have additional resources available for visitors on their institution websites to promote further engagement. Placing a link or QR code in the virtual gallery allows artists’ bios, headshots, and social media information to be a click away, but prevents what would be additional assets from weighing down the main virtual exhibition environment.

Figure 17.

In the exhibition of ECC Performance Art featuring student work from their 2020 camp, a QR code was placed on a wall within the space, encouraging visitors to learn more about the featured artists by visiting the companion website.

5. Changing Exhibition Practice Education

Based on these virtual exhibition experiences and others, I have developed and taught two capstone courses on digital curation for the UCLA Digital Humanities (DH) program.25 Through the course, students learned the fundamentals of curation. Working with the UCLA Library Digital Collections,26 students selected the main themes of the exhibition, identified, and sought permission to use related digital artworks and resources, wrote wall labels, and planned a launch event. In addition, students had the opportunity to learn how to build a 3D environment for the works to be displayed and/or make use of 3D models in their virtual exhibition, using Mozilla Hubs and Spoke as a VR platform for exhibition.

In the first iteration, I worked with five students to create an exhibition with the James Arkatov Jazz Photograph Collection.27 In the second, I worked with three students on separate digital collections-based exhibitions. The small class sizes allowed for project flexibility as the students were introduced to new tools and techniques each week. Since UCLA’s digital collections make use of IIIF,28 students used Mirador as a digital light table to present on possible thematic groupings of works in the collections.29 Google Jamboard was utilized to sketch various exhibition layouts, and then the final layout was prototyped in 3D using Tinkercad.

In the spring of 2024, I shifted to a lecture/seminar framework for the course, where we simultaneously covered historical and ethical examples relating to display, while building with selected local special collections material. In terms of the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL), the tools of WebVR and Web3 can change the way we teach exhibition practice to those entering the museum field, providing more hands-on training.30 Virtual realities—like exhibitions—are negotiated, representative, and carefully curated (Albrezzi 2019, pp. 188–229). Building digital galleries can play a crucial role in how students learn about the methods applied within exhibition-making. Using digital tools will better prepare students for the field through experiential learning and enhance their ability to realize their creative and scholarly potential. A praxis approach with WebXR tools also allows for students to more easily iterate their ideas, which can lead to a faster learning process (Grant 2021).

In terms of more general education, research has demonstrated the productive value of the arts and arts education.31 Arts education scholar and advocate Ken Robinson argued that the creative skills taught in arts classrooms are invaluable across disciplines and increasingly important within a world that is driven by fast innovation (Robinson 2011). In an increasingly hybrid world, digital literacy is highly valued. Thus, learning how to leverage the human sensorium and a network of cultural contexts to effectively communicate through design with digital tools is a meaningful paradigm shift. In addition, exhibition-building emphasizes the importance of contextual information, which allows for a bigger picture to be seen and can provide in situ understanding, despite being remote.32

6. Conclusions

Whether you see them as “image-texts”, in the vein of J. T. Mitchell, or as an act of translation, following the ethos of Walter Benjamin, virtual exhibitions are acts of creation.33 During the pandemic, growing interest and demand was a catalyst for development of digital exhibition spaces. However, virtual exhibitions are not facsimile experiences in lieu of the real-world versions. WebXR can offer curators and audiences on par displays of digital works. In addition, the digital tools offer hands-on learning opportunities, expanding the reach of practice-based learning for exhibition work.

In the years ahead, digital gallery spaces may become an increasingly integrated part of the metaverse and the growing digital marketplace that is happening with the use of blockchain and cryptocurrencies. Already there are a number of gallery spaces within various metaverse environments (e.g., tzland is a virtual world and marketplace for 3D NFT work that is built with the tezos blockchain).34 However, the digital art market’s rapid growth has not been without challenges. The speculative nature of cryptocurrency markets has introduced volatility, where art is often bought and sold as an asset class rather than for its aesthetic or cultural value. Additionally, the environmental impact of blockchain technology—specifically, the energy consumption required to maintain blockchain networks—has sparked debates about the sustainability of these practices. Concerns about copyright infringement and the potential for art theft in the NFT space have also emerged, leading to calls for better regulation and protection for artists.

Despite these issues, digital galleries and blockchain technologies have democratized access to the art world. Artists from diverse backgrounds now have the opportunity to reach global audiences and profit from their work in ways that were previously limited by geography or institutional gatekeeping. The art market is being reshaped by these digital tools, raising new questions about value, ownership, and the future of artistic production.

For now, digital galleries allow for some of the same interactions that physical exhibitions do and provide us with methods to achieve designs and scholarly arguments that might not be possible in the non-virtual world. In this evolving landscape, virtual exhibitions provide a unique opportunity to reimagine how we curate, teach, and engage with art. These exhibitions offer a living, flexible platform for knowledge production, enabling curators to foster global conversations and explore new narrative structures that reflect the interconnectedness of contemporary culture. As curators continue to experiment with these technologies, they must balance innovation with ethical responsibility, ensuring that virtual exhibitions remain sustainable, inclusive, and critically engaged. As Mary Nooter Roberts stated, “[E]xhibitions are never passive representations, but are themselves “objects of knowledge,” and this does not change when the practice involves digital modalities (Roberts 2008, p. 171). Virtual exhibitions are not merely substitutes for physical spaces; they represent a distinct and evolving form of knowledge production that will continue to redefine the future of art curation and education.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No applicable datasets. All referenced data materials were cited in the article.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to my colleagues at the DAHJ and ECC Performance Art, and all the other collaborators and artists I have worked with on the virtual exhibitions discussed in this article and beyond. I appreciate your willingness to experiment and create together. Thank you to UCLA’s Digital Humanities program for allowing me to share my passion for digital curation with our students, which inspired the SoTL work that is presented in this article. I also thank Lisa M. Snyder for her constructive notes, which always make the work stronger.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | GLAM is an acronym for galleries, libraries, archives, and museums. |

| 2 | See: https://www.moca.org/virtual (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 3 | See: http://www.peertospace.eu/ (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 4 | Artists and art investors finally embraced the blockchain. I say “finally” because I have been talking about these technologies since 2015 when bitcoin and the blockchain were extremely nascent, but stood out as a way of being able to track provenance of digital art and provide artists with royalties. There are still many issues within this new digital market space, but artists are now selling their art digitally through these systems, and it has, for better or worse, transformed the art market on a global scale. |

| 5 | I have argued this in my previous work. See (Albrezzi 2019). |

| 6 | A notable exception would be a traveling exhibition that shifts slightly to fit each site on the tour. However, the intention is typically to keep the installation close to the original design. |

| 7 | Take, for example, the sunsetting of the Mozilla Hubs platform hosted by Mozilla on 31 May 2024. The code is open source, and a community is rallying to support personal installations of the software: https://hubsfoundation.org/. Platforms like MUD Verse by the MUD Foundation allow for Spoke files from Mozilla Hubs to be uploaded: https://www.mud.foundation/mud-verse (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 8 | The exhibitions are accessible via the platform (https://hubs.mozilla.com/, accessed on 30 May 2024) and are built using the WebXR editor, Spoke (https://hubs.mozilla.com/spoke/, accessed on 30 May 2024). I have provided training on how to use and create with these platforms, which can be found at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UWbU6zJILyY (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 9 | The archived exhibition can be found at: https://dahj.org/galleries#/absurdist-electronics/ (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 10 | Because of this, I consider this a more advanced digital exhibition design and would caution beginners to start with such a layout. I would recommend using hexagonal shapes and working with single-level designs until a strong proficiency is gained. Even at that point, it is important to account for the extra installation time it will take to adjust works for the variation in the wall angles, as opposed to installing on a single flat wall. |

| 11 | View the archived interview at: https://vimeo.com/639288271 (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 12 | See https://artsci.ucla.edu/ and https://vimeo.com/artsci (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 13 | See http://opendoclab.mit.edu/ and http://opendoclab.mit.edu/lecture-series/ (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 14 | Under Mozilla Hubs’ usual service, users are limited to a 50 avatar maximum in the space at once. However, there is no limit to how many users can be in the “lobby” for a Mozilla Hubs room, though the performance “may decrease once there are over one hundred people in the lobby,” according to the Mozilla Hubs documentation (see https://hubs.mozilla.com/docs/hubs-faq.html, accessed on 30 May 2024). In the lobby, you can see aspects of the space and hear those in the room who are talking via their avatars. |

| 15 | The pleasure of these experiences was measured in the anecdotal positive feedback our team experienced from those who attended. Though we have yet to conduct formal user experience evaluations, the majority of the qualitative responses have indicated that people find the experiences novel and enjoyable. Scholars such as Stephen Greenblatt have described how wonder and resonance can work in concert to produce the most impactful exhibition experience—one in which the visitor is both awed by and more deeply informed by an object simply by experiencing it under the right circumstances. See (Greenblatt 1990). In the wider field, we are seeing that virtual engagement can increase attendance dramatically. When the University of Southern California partnered with the Pacific Asia Museum to create a Matterport tour of their exhibition, they saw a significant increase in their web traffic after the virtual facsimile was launched. They also saw that their physical attendance was boosted from 30 to 40 to over 800 visits. Bethany Montagano, the museum’s director, said, “It democratized the exhibition and its messages, opened them up to a broader audience and made our important work much more accessible.” See https://today.usc.edu/virtual-art-museum-tours-exhibitions-after-covid-pandemic/ (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 16 | The archived exhibition can be found at https://dahj.org/zonas-de-contacto (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 17 | See https://revistas.uniandes.edu.co/index.php/hart/index (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 18 | Not every exhibition team operates in the same way. For a useful guiding resource regarding building a functional exhibition team, see (Laurie and Powell 2018). |

| 19 | See https://www.canva.com/ (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 20 | For building in Spoke by Mozilla Hubs, it is best to have a designated creator or to create a schedule assigning separate times to work in the environment for each modeler. However, some modeling software does allow for simultaneous collaboration. When teaching the basics of modeling to students, I have used Tinkercad’s web interface (https://www.tinkercad.com/, accessed on 13 October 2024), which operates much like Google Docs, in order to allow simultaneous editing of a model in one virtual space. |

| 21 | World-building is a concept that professor and production designer Alex McDowell has taken to another level at USC’s World Building Media Lab, where it is defined as “an experiential, collaborative and interdisciplinary practice that integrates imagination and emergent technologies, creating new narratives from inception through iteration and prototyping into multimedia making.” See https://worldbuilding.usc.edu/ (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 22 | For more information regarding these exhibitions, see (Vogel 1991; Corrin 1994). |

| 23 | To quickly substitute an asset in Spoke, users can, without placing the asset, copy the url from the href property of the new asset. Users can then navigate to the old asset that needs to be replaced, and substitute the new url in the href property section. This will automatically replace the old asset with the new asset, maintaining the same property coordinates and characteristics in the process. |

| 24 | See Figure 16. |

| 25 | To view a summary and some photos of the student project, visit https://dh.ucla.edu/blog/the-power-of-jazz-undergraduate-capstone-project/ (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 26 | I was more flexible regarding this requirement for the graduate students I worked with, and allowed them to utilize resources related to their research. |

| 27 | See the collection at https://digital.library.ucla.edu/catalog/ark:/21198/zz001dzc12 (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 28 | IIIF or the International Image Interoperability Framework is an open standard for sharing high-quality images online. Learn more about it at https://iiif.io/ (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 29 | See https://projectmirador.org/ (accessed on 13 October 2024). |

| 30 | I have written previously about the ways most exhibition practitioners receive training through museum or gallery internships, and the issues surrounding the apprenticeship approach to museum education. See “Chapter 7: For Posterity and Pedagogy: Using 3D Models and 360 Capture to Preserve Exhibitions and Teach Museum Studies” in (Albrezzi 2019, pp. 188–229). |

| 31 | Some of the most recent publishing in this area includes (Susan and Ross 2023; Carnwaith 2023). |

| 32 | See “Chapter 7: For Posterity and Pedagogy: Using 3D Models and 360 Capture to Preserve Exhibitions and Teach Museum Studies” in (Albrezzi 2019, pp. 189–90). |

| 33 | For more on image-texts, see (Mitchell 2010). Regarding the application of Benjamin to exhibition practice, see (Roberts 2008). |

| 34 | See https://www.tz1and.com/ (accessed on 13 October 2024). On the subject of the metaverse for showcasing art, NFTs have proven that the so-called “10 k series” has been an effective marketing and fund-building tool for artists. However, more boutique-style selling is still hindered by some cultural and technological hurdles, such as the instability of the cryptomarkets and rapidly changing blockchain technological landscape. Nevertheless, this opens up possibilities for the minting of virtual exhibitions themselves, where curators and artists alike could receive commissions and royalties if the exhibition sells on the blockchain. For more on the NFT art market, see (Vilá and Sofia 2023). |

References

- Albrezzi, Francesca. 2019. Virtual Actualities: Technology Museums and Immersion. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5tc2q2dt (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Bal, Mieke. 1996. The Discourse of the Museum. In Thinking About Exhibitions. Edited by Reesa Greenberg and Bruce W. Ferguson. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 1969. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In Illuminations. Edited by Hannah Arendt. Translated by Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books. First published 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, Claire. 2022. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. New Edition. Tenth Anniversary re-edition. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Carnwaith, John. 2023. Creatives Count. Detroit: WolfBrown. Available online: https://racstl.org/wp-content/uploads/RAC-Creatives-Count-Report-FINAL-11.9.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Castro, Annabel. 2020. Outside in: Exile at home an algorithmic discrimination system. Artnodes 26: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrin, Lisa G. 1994. Mining the Museum: Artists Look at Museums, Museum Look at Themselves. In Mining the Museum: An Installation by Fred Wilson. New York: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus. Translated by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p. 21. First published 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Derrida, Jacques. 1982. Différance. In Margins of Philosophy. Translated by Alan Bass. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, Johanna. 2019. The Museum Opens. International Journal for Digital Art History 4: 2.1–2.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, Bruce W. 1996. Exhibition rhetorics: Material speech and utter sense. In Thinking About Exhibitions. Edited by Reesa Greenberg and Bruce W. Ferguson. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1984. Of Other Spaces, Heterotopias. Translated from Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité 5: 46–49. Available online: https://foucault.info/documents/heterotopia/foucault.heteroTopia.en/ (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Graham, Beryl, Sarah Cook, and Steve Dietz. 2010. Rethinking Curating: Art After New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, Janna, and Shadya Yasin. 2008. Reframing Participation in the Museum: A Syncopated Discussion. In Museums After Modernism: Strategies of Engagement. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Adam. 2021. Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know. New York: Viking an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Greenblatt, Stephen. 1990. Resonance and Wonder. In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. Edited by Ivan Karp. Washington, DC and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. 43–56, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Kenderdine, Sarah, and Andrew Yip. 2018. The Proliferation of Aura. In The Routledge Handbook of Museums, Media and Communication. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara. 1991. Objects of Ethnography. In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. Edited by Ivan Karp and Steven Lavine. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laurie, Brigid, and John Powell. 2018. A Guide to Exhibition Development, Smithsonian Exhibits. Landover: Smithsonian Exhibits. Available online: http://exhibits.si.edu (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Mastai, Judith. 2008. There is No Such Thing as a Visitor. In Museums After Modernism: Strategies of Engagement. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., pp. 173–77. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, Jon. 2001. Perform or Else: From Discipline to Performance. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, Tara. 2012. Why Are the Digital Humanities so White? or Thinking the Histories of Race and Computation. Debates in the Digital Humanities 1: 139–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgram, Paul, and Fumio Kishino. 1994. A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays. IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems 77: 1321–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, William J. Thomas. 2010. What Do Pictures Want?: The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Doherty, Brian. 1996. The Gallery as Gesture. In Thinking About Exhibitions. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Christiane. 2015. Digital Art, 3rd Rev. ed. Farnborough: Thames & Hudson Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, Peggy. 1993. Unmarked: The Politics of Performance. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, Mary Louise. 1991. Arts of the Contact Zone. Profession 34. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25595469 (accessed on 13 October 2024).

- Roberts, Mary Nooter. 1994. Does an object have a life? In Exhibition-Ism:Museums and African Art. New York: Museum for African Art. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Mary Nooter. 2008. Exhibiting Episteme: African Art Exhibitions as Objects of Knowledge. In Preserving the Cultural Heritage of Africa: Crisis or Renaissance. Edited by Kenji Yoshida and John Mack. Muckleneuk: Unisa Press, vol. 13, pp. 170–86. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Ken. 2011. Out of Our Minds: Learning to Be Creative, fully rev. and updated ed. Oxford: Capstone. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff, Irit. 2006. Terra Infirma: Geography’s Visual Culture. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rumsey, Abby Smith. 2016. When We Are No More: How Digital Memory Is Shaping Our Future. New York: Bloomsbury Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanek, Lukasz. 2011. Henri Lefebvre on Space: Architecture, Urban Research, and the Production of Theory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, p. ix. [Google Scholar]

- Susan, Magsamen, and Ivy Ross. 2023. Your Brain on Art: How the Arts Transform Us, 1st ed. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Diana. 2003. The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vilá, Quiñones, and Claudia Sofia. 2023. A Brave New World: Maneuvering the Post-Digital Art Market. Arts 12: 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, Susan Mullin. 1991. Always True to the Object, in Our Fashion. In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. Edited by Ivan Karp and Steven D. Lavine. London: Routledge, pp. 191–204. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).