Abstract

In art-historical terms, a self-portrait in assistenza refers to an artist having inserted their own likeness into a larger work. In Renaissance-era art, more than 90 examples have been identified, famously including Botticelli’s Adoration of the Magi (c. 1478/1483). There, Botticelli glances out from the painting, making direct eye contact with the viewer, a feature that appears in other self-portraits of the type. In ancient Egypt, it was not commonly accepted that an artist would lay claim to it, especially when the work’s scale imposed diversification of tasks to be performed or teamwork organized on a workshop basis. This article will present evidence discovered in the Chapel of Hatshepsut in her temple at Deir el-Bahari that can be interpreted as a self-portrait in assistenza and indicates that Djehuty, Overseer of the Treasury under Hatshepsut, took the lead role there. If this identification is valid, the room’s decoration gains an additional layer of meaning and may be “read” in terms of Djehuty’s message, comparable to Botticelli gazing out from his Adoration of the Magi. This ancient Egyptian case will illustrate how that artist-designer, in interweaving subtle indicators of his involvement in the work, expresses awareness both of his intellectual skills and of his pride in creation.

1. Introduction

In the Egyptological discourse, common knowledge has it that ancient Egyptian art is an anonymous art, even an art without artists.1 Indeed, despite that era’s broad social need for artistic production and thus of its artist-makers, the prevailing custom of not signing works has resulted in many thousands of preserved artworks we cannot link to their makers (for an overview, see Oppenheim 2006, pp. 216–19; Laboury 2012, pp. 199–200; Allon and Navrátilová 2017; Laboury and Devillers 2023, pp. 163–65). A difficulty in the identification of an actual author derives, on the one hand, from collective dimensions of artistic production (notable case studies: Baines 1989; Bryan 2001; Pieke 2011)—the environment in which developing individual style is subordinated to overriding conditions of homogeneity. On the other hand, the picture might be obscured by the omnipresence of a given work’s patron, who, as Jan Assmann has emphasized (Assmann 1987; 1996, pp. 55–56 and ff.; summary in Assmann 1991, pp. 139–40), “‘self-thematized’ himself through the work of art” while the object maker “withdraws his own identity from his creation”. (The quotation follows Laboury 2012, p. 199).2

Even though some ancient Egyptian makers can be identified (as will be discussed below), in the royal context—i.e., when a state commission was involved—instances in which specific names can be linked to their creations are infrequent. The fundamental reason for this seems to be the scale of work conducted in those mostly monumental endeavors, which logically imposed the diversification of tasks to be performed.

In this article, I will present one rare example of a royal monument in which, while under the patronage of Hatshepsut, the female pharaoh, the designer of its decoration seems to introduce features indicating his identity in a way art history calls a self-portrait in assistenza. The term, coined by André Chastel (1971, pp. 537–40), is applied to cases in which a work’s maker inserts their own likeness into a narrative scene comprising multiple figures (alternatively, it is described as “participant”, “bystander”, or “embedded” self-portrait). In European art, this device occurs as early as the Quattrocento and is considered a form of artistic signature before written signatures became commonplace.3

While the term is borrowed from early modern European art history, where it has been thoroughly researched (e.g., Ames-Lewis 2000, pp. 208–43; Reynolds 2016, pp. 164–71), cases identified in ancient Egyptian art are numerous, as underlined for the first time by Dimitri Laboury (2015, pp. 328–29 and ff.).4 This demonstrates that the issue is not at all limited to European art and that it did not, in fact, emerge in the early Renaissance (cf. n. 3 in the present paper). What is more, it seems ill-suited to claim the emergence of the need for such self-portraits because of humanist concerns (implicitly, again, typical of the European cultural legacy). On the contrary, it may be postulated that human-centered values and ideas—those focusing on a human being in general and the intellectual abilities of an artist in particular—may be successfully found in cultures and societies earlier than Quattrocento and outside Europe,5 as will be demonstrated by our case below.

Be that as it may, the Renaissance examples of self-portraits in assistenza, whose social and other contexts are well understood, will provide a background against which our ancient Egyptian case will be presented. As we will see, despite the fact that these two societies—so distant in terms of time and place—were quite different in many aspects, the figure of the artist, with their creative force and the awareness of their uniqueness—resulting from the possession of that force—is to be seen as the bridge between these two societies, indeed, their common ground. Further similarities may be found in the high esteem and social position artists enjoyed, as well as in their own aspirations to the intellectual elite of their time, through demonstrating diversity of skills and thorough education (for the Renaissance, see Blunt 1962, pp. 48–57 and passim). Through the presentation below of several aspects of European self-portraits in assistenza, it is postulated that similar features are also to be found in ancient Egypt. This conclusion, again, encourages the search for parallel instances in other cultures and in other parts of the world.

In Renaissance art, an important factor in the inclusion of a “self-portrait in assistenza” signature is the artist’s planned interaction with the viewer: while the composition’s subject can be interpreted without recognizing its maker’s features, a viewer’s appreciation will be enhanced by understanding that a work is intended to operate on more than one level—and many contemporaries would have recognized an artist’s autobiographical intention (Reynolds 2016, p. 166).

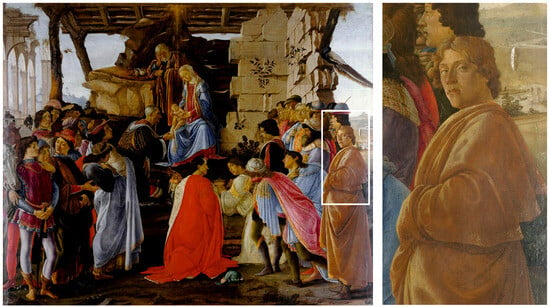

The Adoration of the Magi, commissioned from Botticelli by the banker Gaspare Zanobi del Lama for his family chapel in the Santa Maria Novella church in Florence (Figure 1), is one of the most celebrated examples of this. In the composition, the painter placed himself on the far-right side, making direct eye contact with the viewer. This artistic device of a gaze toward the observer, lateral position, and specific attitude—all are indices of discretion and compositional integration yet at the same time of distinction, serving to ensure firm recognition of the individual who has been represented (Laboury, personal communication, 10 August 2023)—is well known and acknowledged in dozens of artworks from that period (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Botticelli, The Adoration of the Magi. Altarpiece of Santa Maria Novella, Uffizi Gallery, Florence, tempera on wood (111 × 134 cm), c. 1478–83. Detail: the author’s self-portrait in assistenza.

Figure 2.

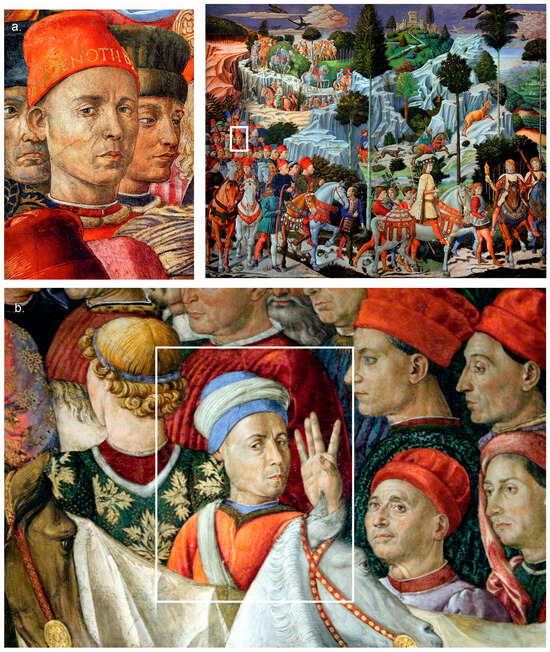

Benozzo Gozzoli, frescoes in the Magi Chapel, Palzzo Medici-Riccardi, Florence, 1459–62: (a) East wall, The Procession of Caspar; (b) detail from the West wall, The Procession of Melchior. In squares and enlarged detail in (a): the author’s self-portraits in assistenza.

Figure 3.

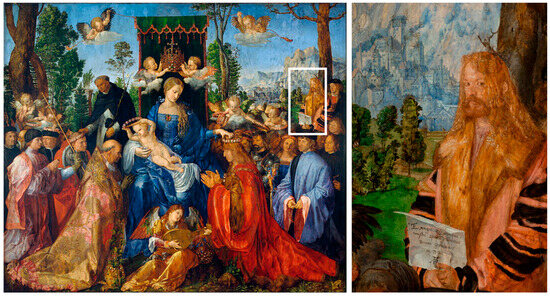

Albrecht Dürer, The Feast of the Rosary, National Gallery of Prague, oil on panel, 162 × 192 cm, 1506. Detail: the author’s figure holding a piece of paper with the Latin inscription reading “Albrecht Dürer the German spent (i.e., finished [this] within) the space of five months. 1506” (translation after Peština 1962, p. 24).

TExchanging eye contact with the observer is a powerful message, immediately grasping the audience’s attention, and is made all the more emphatic when the portrait is recognized, as if declaring that “what you see is by my mind and by my hand”.6 Additional indicators are sometimes provided: in the case of Benozzo Gozzoli’s self-portrait (Figure 2a), he wears a red hat inscribed with Opus Benotii, “Benozzo’s work”, to be considered a signature proper and, at the same time, as a pun on words plausibly communicating that the author wants this fresco cycle—and himself—to be ben noti (well noted) by a viewer (Ames-Lewis 2000, p. 228). On the cycle’s opposite wall, where the retinue of another Magus is represented, beside the painter’s inserted likeness we see the raised right hand (of an individual depicted next to him), calling attention to the concept of recta manus: the skillful hand that made the opus in question (Ames-Lewis 2000, pp. 215–16).

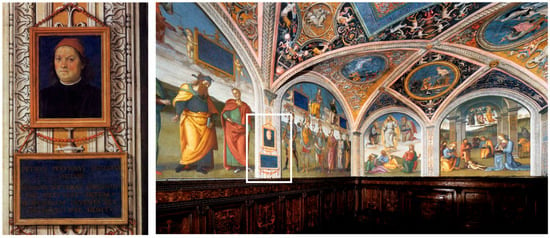

It is broadly recognized in art history that self-promotion is the meaning of a self-portrait in assistenza (Chastel 1971, p. 537 uses the expression “glorification”), underscoring the artist’s practical, intellectual, and even social positions (Ames-Lewis 2000, pp. 228–34, 239–43). One can consider an additional motivation: pride in creation, the ability to bring an image into existence, and the sense of being somehow unique in this respect. An inscription attached to another self-portrait, included in frescoes in the Colleggio del Cambio in Perugia (Figure 4), reads: “Pietro Perugino, celebrated painter. If the art of painting became lost, he would restore it. If it had never been invented, he alone could bring it to this point” (Ames-Lewis 2000, p. 2018).

Figure 4.

Pietro Perrugino, frescoes in Collegio del Cambio, Perugia, 1500. Detail: the author’s self-portrait and his self-description.

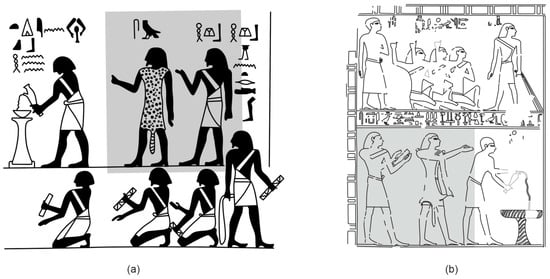

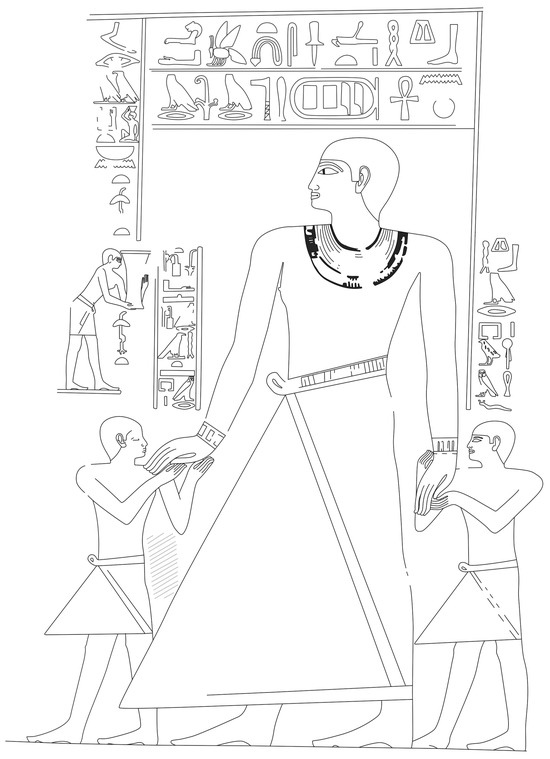

In ancient Egypt, in contrast to the communis opinio about anonymity in its art noted above, dozens of artists’ signatures have been recorded, many of them categorized as self-portraits in assistenza (for an overview and examples, see Oppenheim 2006, p. 216, n. 3; Laboury 2015, passim, esp. nn. 1 and 4; notable earlier studies on the matter are Ware 1927; Junker 1959; see also n. 4 in this paper); and yet, the number of identified artists remains low compared to the quantity of preserved ancient Egyptian artworks that were never signed.7 One of these signed works (Figure 5) is an oft-cited case of Seni of the Old Kingdom, the painter (sS qd(wt), “scribe of forms”) claiming to have decorated a governor’s tomb at Akmim being alone (wa.kw) (Kanawati and Woods 2009, pp. 9–10; Laboury 2012, p. 201; 2016, pp. 379–81; Laboury and Devillers 2023, pp. 172–73).

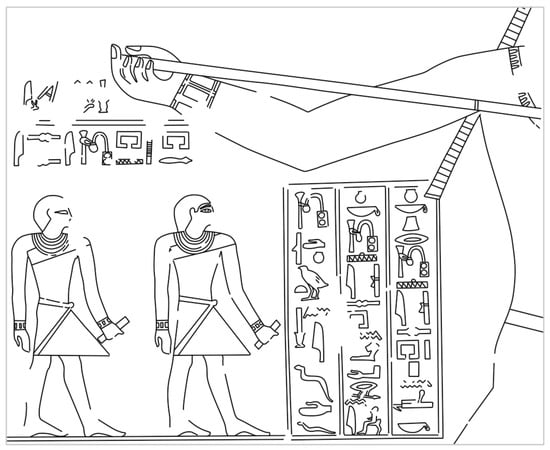

Figure 5.

Self-portrait in assistenza of two artist-brothers in an Old Kingdom tomb at Akhmim: the scribe of forms, Seni, and the scribe of the house of the god’s books of the Great House, Isesi (drawn by the author, after Kanawati and Woods 2009, Fig. 5). Although Seni boasts of being the only artist, he is shown together with his brother, Isesi. An identical representation comes from a neighboring—slightly earlier—tomb, where the same two brothers worked, and where Isesi seems to have been the main designer, as reflected in the focus put on him in that corresponding scene. Note that both artists wear a sash across their chests and hold papyrus scrolls in their hands, both typical attributes of a lector-priest. The role of lector-priests in the design process of mural decorations is commented on below.

This brings us again to the issue of collective work in monumental projects, including ancient Egyptian temples, and the problem of ascribing the resulting production to one person, even when we assume it to have been finished within a single reign and not, as with the Karnak temple, for example, a construction process lasting for centuries, as would be required with many European cathedrals.

In the context of our interest in a relief-decorated building, the case of the Parthenon in Athens may be illustrative. There, Pheidias is considered the person who conceived the decorative scheme and oversaw the execution of the reliefs (Neils 2005, pp. 219–20; Lapatin 2005, pp. 262–63; Laboury 2012, p. 200), and thus, on record as its main artistic author, the contributions of the rest of his team are absorbed into his name:8

[13.4] His [Pericles’] general manager and general overseer was Pheidias, although the several works had great architects and artists besides. Of the Parthenon, for instance, with its cella of a hundred feet in length, Callicrates and Ictinus were the architects (…).[13.9] But it was Pheidias who produced the great golden image of the goddess, and he is duly inscribed on the tablet as the workman who made it. Everything, almost, was under his charge, and all the artists and artisans, as I have said, were under his superintendence, owing to his friendship with Pericles.(Plutarch 1916; it is noteworthy that this was written ca. five centuries after the Parthenon’s construction).

With the Temple of Hatshepsut harmoniously integrated within Deir el-Bahari’s rocky landscape (Figure 6a), the building process is considered to have lasted through this female pharaoh’s entire reign (ca. 1473–58 BC: Roehrig et al. 2005, p. 6), i.e., approximately 15 years (Arnold 1975, col. 1017 with n. 6). Senenmut—the most prominent individual at Hatshepsut’s court (for his career overview, see Helck 1958, pp. 356–63, 473–78; Ratié 1979, pp. 243–64; Dorman 1988, passim, esp. 165–81; 1991; 2005, pp. 107–9; Roehrig 2005b, pp. 112–13; Shirley 2014, pp. 188–93; Allon and Navrátilová 2017, pp. 25–39)—is the person usually considered its architect and by extension the designer of its decoration. The most explicit declaration of Senenmut’s involvement in Hatshepsut’s building projects is found on his statue from Karnak (CG 579):

[It has been ordered] to the high steward Senenmut to supervise every work of the king (i.e., Hatshepsut) [parenthetical explanations are by the present author] in Ipet-sut (i.e., the Karnak temple) in southern Iunu (i.e., Thebes) [in the temple of A]mun called Djeser-djeseru (i.e., the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari), in the House of Mut in Isheru (i.e., Mut precinct in Karnak), in the Southern Sanctuary of Amun (i.e., the Luxor Temple) [satisfying the heart of the Majesty] of this noble god and magnifying the monuments of the Lady of the Two Lands.(Urk. IV, 409.5–12; Dorman 1988, pp. 126–27; the English translation follows Taterka 2015, pp. 30–31).

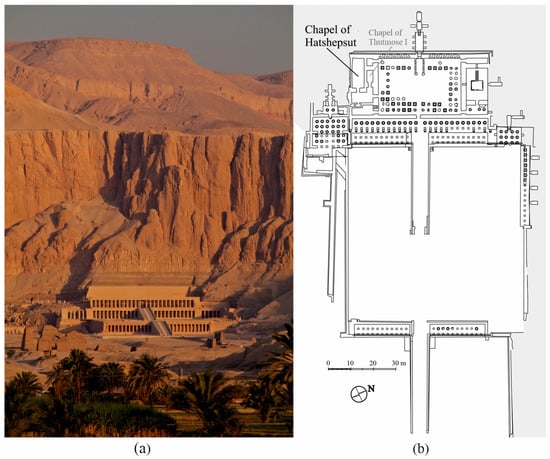

Figure 6.

The Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari: (a) general view (photo M. Jawornicki/@PCMA UW); (b) plan (T. Dziedzic/@PCMA UW).

At this point, however, Peter Dorman’s statement cannot be overlooked: “[t]he common claim that Senenmut was the architect of Deir el-Bahari is based largely on his holding the rare title ’Overseer of works of Amun in Djeser-djeseru’ (…), but it is otherwise unsubstantiated” (Dorman 2005, p. 108; see also Dorman 1988, pp. 175–76 with n. 72). Indeed, the function of an “Overseer of Works” implies supervision of a building project (i.e., logistical coordination over works being executed in the construction of a given monument). This is by no means the equivalent of designing a monument’s decorations, which may be especially relevant in that other of Senenmut’s contemporaries were far more precise about their roles in various of Hatshepsut’s architectural projects and also held the title “Overseer of Works” (Ratié 1979, p. 165 with n. 6; Dorman 1988, pp. 175–76 with n. 72; Dorman 2005, p. 108 with n. 14; Bryan 2006, p. 86; in the final section of this article, several of these contemporaries will be discussed).9

Thus, the question remains open regarding who (and how many) held responsibility for ideas that led to the Deir el-Bahari temple, from its placement and its terraced shape to the number of its sanctuaries and, ultimately, the content and appearance of its wall decoration (cf., e.g., Arnold 2005, p. 135). Taking into account the scenario in which a monument may have multiple principal makers shall not prevent us from considering its design stage, however, and imagining its existence in draft form, then going further into the earliest stage when it was but an imagined form. Laboury and Devillers (2023, p. 165) have summarized this: “The number of actors in the making of the artwork is above all a matter of efficiency, mainly determined by the quantitative importance of the task to carry out; and moreover, its increase never annihilated the creative mind that designed the work”.

In what follows below, the aim is to present one person who is detectable, as I will argue, in his role in designing the decoration in one of the temple rooms. This is by no means intended to advocate the view that this person was the sole designer even in this single room, as will be demonstrated. The room that will be focused on is known as the Chapel of Hatshepsut, located on the temple’s third terrace (Figure 6b) and intended for Hatshepsut’s mortuary cult. Its lateral north and south walls are decorated with what are referred to as offering scenes, typical of this type of cult space (Stupko-Lubczynska 2016b).

2. The Adoration of the Magi in the Renaissance and the Ancient Egyptian Offering Scene—A Common Place?

Before presenting the Chapel of Hatshepsut’s assumed self-portrait in assistenza, let’s return to the Adoration of the Magi theme, focusing on the development of composition and content in artistic realizations of that theme. The aim here is to highlight features that may help us understand an artist’s motivation for inserting their own image through the lens of the interplay between the scene’s overall sociocultural message and their personal reception of it. In Renaissance art, the Adoration of the Magi appears among the most favored subjects due to its potential to fulfill a need to display real historical figures recognizable to an assumed contemporary viewer. The Botticelli altarpiece (Figure 1) mentioned above, on display in Santa Maria Novella, thus admired over the centuries by many in Florence, features numerous of its painter’s contemporaries along with him and his patron, chief among these being members of the Medici family, headed by Cosimo the Elder and his two sons attired as the Magi (Vasari [1550] 1991, pp. 226–27; Hatfield 1976, pp. 68–100; O’Malley 2019, pp. 7–8; Zambrano 2019, pp. 20–21 with n. 26).10 Indeed, there seems no better theme for demonstrating earthly power with all its splendor while maintaining a humble attitude towards Mary and the Child’s superior, divine figures (Shackford 1923).

In considering the potential for variability in representing the retinues of the Magi, what becomes conspicuous is contrasting focal representations of the Virgin and Child, with the latter being the most consistently iconic image in Christian artistic tradition. When these central figures are considered, attempting to compare Madonna iconography (Figure 7)—in the rocks, in the rose garden, in church, with saints, with contemporary donors to the artwork, and, among these other themes, with the Magi—with ancient Egyptian iconography, a comparably iconic image that comes to mind is the deceased seated at the offering table (Figure 8; note that images in Figure 7 and Figure 8 cover a similar period of time: over a thousand years). When one takes into account these scenes’ respective developments in content, motifs can be seen in parallel: elaboration from a simple image to much more complex compositions is observable, with the core remaining unchanged, even fossilized, while what surrounds it can be customized in keeping with current trends and other variables, with freedom potentially given to the artist to demonstrate personal invenzione: from the deceased shown with or without an offering list to the presence of family members, pets, in varying attire, and so forth.11

Figure 7.

Variations on a theme of Madonna and Child: (a) Virgin and Child between Saints Theodore and George, VI/early VII century AD, encaustic on wood, 68.5 × 49.7 cm, St. Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai, Egypt; (b) Rebrandt van Rijn, The Holy Family, 1634, oil on canvas, 183.5 × 123 cm, Alte Pinakothek, München, Acc. No. 1318; (c) Mary Cassatt, Mother and Child (The Oval Mirror), ca. 1899, oil on canvas, 81.5 × 65.7 cm, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Acc. No. 29.100.47.

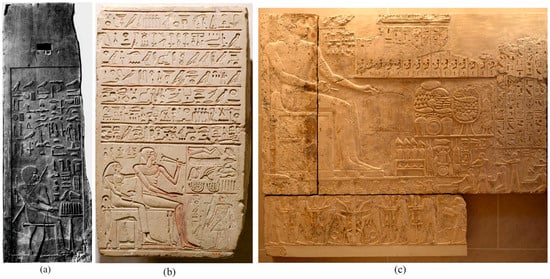

Figure 8.

Variations on a theme of the deceased at the offering table: (a) panel of Hesyra, Third Dynasty, c. 2667–40, cedar wood, Cairo CG 1426 (Quibell 1913, Pl. XXI); (b) funerary stela of Megegi and Henit, Eleventh Dynasty, c. 2059–51 BC, limestone, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Acc. No. 14.2.6; (c) relief decoration from the offering room of Ramses I at Abydos, c. 1295–94 BC, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Acc. No. 11.155.3a.

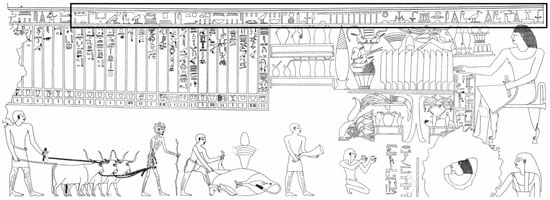

In codified offering scenes decorating the lateral walls in Old Kingdom royal offering chapels (Figure 9), which were 30 cubits long (15.6 m), the broadest freedom is observed in the offering procession, in which rows of courtiers are displayed bringing various gifts toward the main figure (on these scenes and their development, see Stupko-Lubczynska 2016b; 2023, pp. 210–12). Were one to step out of the ancient Egyptian artistic convention and look at these scenes frontally, the similarity with what Adorations of the Magi represent leaps to the fore: in both cases, we find the enthroned figure centrally placed within the crowd of subordinates arriving to pay them homage.12

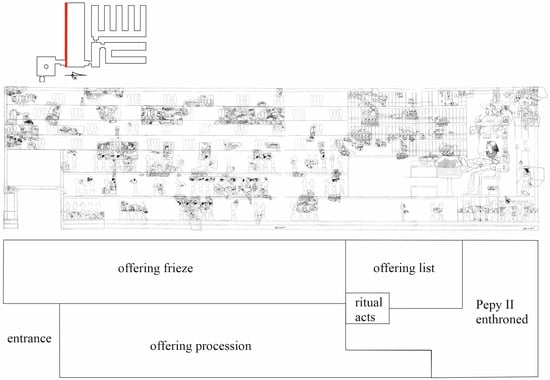

Figure 9.

Offering hall in the pyramid temple of Pepy II, Sixth Dynasty, c. 2278–2184 BC, South Wall (Jéquier 1938, Pls. 61–2; chart by the author).

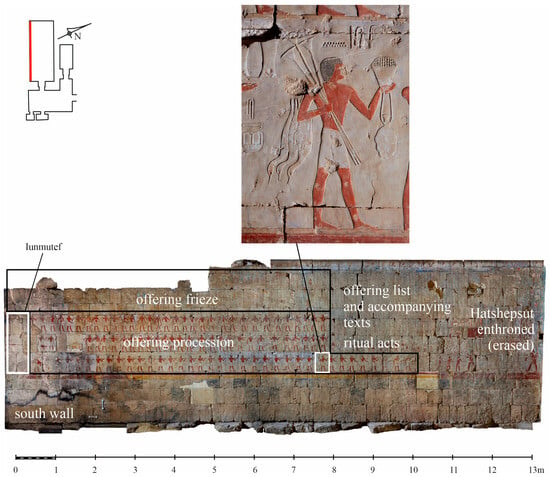

In Old Kingdom offering scenes, figures appearing in the procession represented real people (Jéquier 1938, pp. 57–63) and are labeled with their name and relevant titles (Figure 10). The Chapel of Hatshepsut decoration exemplifies over a millennium of tradition in decorating this type of room. Here too, long lateral walls are adorned with codified offering scenes of classical composition and content, differing in that the offering bearers, precisely one hundred on each wall, all lack names, their titles seeming to be random choices in most cases (Stupko-Lubczynska 2016b, pp. 260–73; some exceptions are noted below), with 12 figures having no title at all.

Figure 10.

Offering hall of the pyramid temple of Pepy II, North wall, detail: an offering bearer named Nipepy (Jéquier 1938, Pl. 91).

3. A Unique Title in the Chapel of Hatshepsut: A Self-Portrait in Assistenza?

Compared to other extant royal offering processions, the one in the Chapel of Hatshepsut is in the best state of preservation, allowing us to assess its content in the most reliable way. Among its two hundred figures (including 12 aforementioned figures with no title), in only two cases are titles not preserved (S II/32 and N I/513), meaning only a single percent is missing from the entire material. Very few titles in the procession across both walls present a single occurrence; in most cases, they can be considered puns on associations between a title and the product being brought by a given individual: a visual link that is semantically irrelevant and can be interpreted as an artist’s amusement and/or a wink towards a future viewer. Thus, mdHw-nswt nwD, the royal maker of pressed-oil perfume (S II/21), brings perfume jars; jmj-rA nw(w), overseer of hunters (S II/5), brings a gazelle from a desert hunt; and wr mDw mHw, the chief of tens of Lower Egypt (N II/22) brings a calf, a “product” of pastoral Delta lands (on these titles, see Stupko-Lubczynska 2016b, pp. 271–72, with further references).14 The rest of the titles in the Chapel have nothing in common with the iconography of their holders.

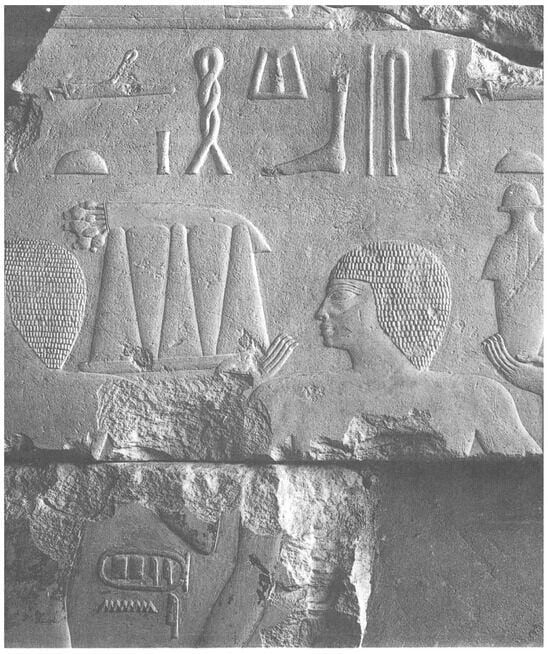

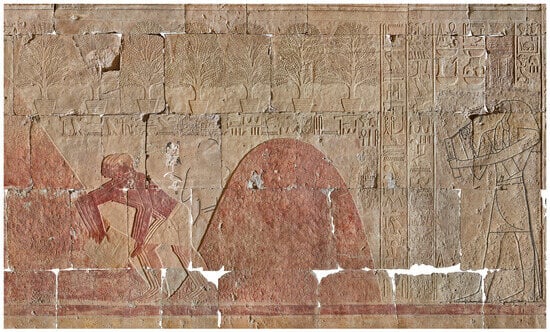

One title stands out from the group of “unique” titles described above. It appears on the North wall in the lowermost register (N I/9); it is the title that seems to indicate a self-portrait in assistenza (Figure 11). It signifies jmj-rA pr[wj-HD], Overseer of the [Double] House of [Silver], i.e., the Treasury (on this title and its holder’s responsibilities in the New Kingdom, see Helck 1958, pp. 182–91; Awad 2002).15 In contrast to other distinct titles in the Chapel, there is no link between this title and the product being offered. Here, it is a piece of meat with ribs, as many other figures represented on the North wall carry (for the meaning of meat’s prevalence on this wall of the Chapel, see Stupko-Lubczynska 2017, pp. 230–32, Figs. 16 and 18; 2016b, pp. 219–35).

Figure 11.

The Chapel of Hatshepsut, North wall. Detail: an offering bearer with the title of the Overseer of the Treasury, a presumed self-portrait in assistenza (photos: M. Jawornicki, J. Kościuk/@PCMA UW; drawings: the author).

In terms of the entire composition of the scene, the placement of jmj-rA pr[wj-HD] is exceptional: first in the bottom register—i.e., at eye level for the visitor—after the group of lector-priests and courtiers presenting severed ox forelegs and fowl; they are linked to the Opening of the Mouth ritual, which constitutes a fossilized component in the complex offering scenes (see Stupko-Lubczynska 2016b, pp. 90–104).16 Thus, the Overseer of the Treasury leads the offering procession proper, in which a considerable amount of artistic freedom is to be observed, as indicated above (for more detail, see Stupko-Lubczynska 2023).

In Hatshepsut’s times, the title Overseer of the Treasury was held by Djehuty, owner of Theban tomb (TT) 11 (see below). Two other officials used the same title: Senemiah, owner of TT 127, and Senenmut (Helck 1958, pp. 400–1; 508–9 [3]; Awad 2002, pp. 47, 49, 214–15; Bryan 2006, pp. 85–86; Shirley 2014, pp. 208–10).17 Assuming that the figure designated jmj-rA pr[wj-HD] is in fact a self-portrait in assistenza (further argumentation is presented below), a logical assumption posits that when one points to their identity using a single title, it would be their most prominent one. With Senenmut, Overseer of the Treasury is one among his wide array of titles and is used quite rarely to mark him compared to other titles, the most lucrative of which (and most frequently used in his monuments) were jmj-rA pr (wr), (Great) Steward, and jmj-rA pr (wr) n jmn, (Great) Steward of Amun (Dorman 1988, pp. 203–11); notably, these two titles are used interchangeably in Senenmut’s ex voto figures in the Hatshepsut temple (cf. n. 9 in this article). As Peter Dorman states, “after Hatshepsut’s accession in year 7,18 Senenmut’s primary office was that of the Steward of Amun (…); references to the royal treasury (…) appear no more” (Dorman 1988, p. 171 with n. 40; see also the discussion in Shirley 2014, pp. 190–91).

Senemiah’s responsibility in the Treasury, meanwhile, appears to have been that of an accountant (Bryan 2006, p. 86; Shirley 2014, pp. 208–10). This effectively excludes him as a candidate for responsibility over the Chapel’s decorative program. As JJ Shirley (2014, p. 210) comments about Senemiah’s tomb (TT 127) and its decorative program, “[t]he prominence of the reception of goods from throughout Egypt and foreign lands combined with an apparent lack of mention of any of Hatshepsut’s monuments would also seem to indicate that he was not overly involved with her building program (…)”.

Taken together, the above evidence prompts identification of Djehuty as the Overseer of the Treasury shown in the Chapel, who owned TT 11, whose other title was Overseer of All the King’s Works (Table 1), and who has long been acknowledged among Hatshepsut’s courtiers involved in her building projects, including Deir el-Bahari (Breasted 1906, p. 153; Kees 1953, pp. 54–55; Hayes 1957, pp. 89–90; Hayes 1960, p. 39 [with Djehuty referred to as “an architect”]; Helck 1958, pp. 397–400; Ratié 1979, pp. 165, 271–72; Dorman 2005, p. 109, n. 14; Bryan 2006, p. 86; Bickel 2013, p. 207; Shirley 2014, pp. 195–98; Galán 2014, pp. 248–50; Engellmann-von Carnap 2014, p. 342; Galán and Díaz-Iglesias Llanos 2020; see also n. 9 in this article). Further evidence for this identification is presented in the next sections of this paper.

Table 1.

Titles and offices of Djehuty in TT 11, with variants and the number of their attestations (after Galán 2014, Table 11.3, with minor changes in order and translation).

Anticipating the reader’s question on Djehuty’s physical involvement in the creation of the Chapel’s decoration, one has to stress that even if we are right in “reading” the title as the signature of its artistic author, it is not to be understood as the execution of the reliefs personally by him.

The operational sequence of Egyptian reliefs has been recognized as a multi-stage process organized on a workshop basis involving numerous people (see Stupko-Lubczynska 2022, pp. 87–90, with further literature). It comprised (1) the planning of the decoration on a portable medium; (2) transposing that composition, using red paint, onto the walls with the help of a grid (the surface of the walls was previously prepared and divided into smaller sections); (3) further elaboration, in black paint, of the sketched drawing (at that stage, details were added); (4) introducing the texts to accompany images (in a similar two-step manner, using red and black paint); (5) carving (also in several minor steps) over the final version of the drawings and texts (i.e., over the black lines); and finally, (6) painting the finished reliefs.19

The steps involved different workforces, and we may securely assume that the drawing, writing, and painting were executed by different people than the carving (scribes and draftsmen vs. sculptors). The preparatory drawings and texts could be applied by the same or different persons (the question of artists’ literacy is a complicated issue that cannot be elaborated here; on it, see Laboury 2016, 2023). The draftsmen and scribes of the preparatory drawings and the painters applying the colors to the finished relief were not necessarily the same people. While stages 1–4 can be characterized as creative ones, i.e., when corrections and alterations could be introduced, the same cannot be said about stages 4 and 5, as the latter were deprived of that initial inventiveness and were, in most cases, mechanical executions of what was planned and approved beforehand.20

A stylistic examination of the relief execution in the Chapel of Hatshepsut invites such a conclusion too, as the workmanship is consistent throughout the entire room. Even though it demonstrates a variation of skills between the master sculptor(s) and apprentices (see Stupko-Lubczynska 2022, pp. 91–95), the distribution of their work is not related to the semantic level of any of the elements comprising the Chapel’s decorative layout but rather corresponds to the complexity of particular motifs. As far as the state of preservation allows us to judge, the carving technique of the figure entitled “the Treasurer” does not stand out, in that respect, from the rest of the images in the Chapel, nor does it demonstrate any reworking. The same concerns other figures studied below as “meaningful ones”.

This leads us to the assumption that the idea of inserting the “telling” title could have emerged at the stage of decoration planning, at the latest at the stage of elaborating the preparatory drawings and texts on the wall (i.e., when the draftsmen and scribes were operating), but ahead of the carving stage. Thus, we argue, Djehuty could have been the author (or one of the authors, see below) of the design that was eventually created and took its final shape through the endeavors of other people.21

4. Djehuty the Scribe

Djehuty’s tomb, TT 11 at Dra Abu el-Naga, currently under study by José Manuel Galán and his team, is known for its extremely innovative and conceptual design.22 For instance, Djehuty is the only one among his contemporaries to have cryptographic texts on his tomb facade (Espinel 2014, with references to the earlier literature). This text, which the tomb’s owner is said to have written (Espinel 2014, p. 327), can be seen to manifest Djehuty’s familiarity with restricted religious knowledge and his scribal proficiency (Espinel 2014, pp. 319–29), as well as a playful statement and public message, as it “served as Djehuty’s ’business card’ for the most educated visitors and as a lure for trained scribes ready to face up to, or play in, an intellectual challenge” (Espinel 2014, p. 326).23

Along with these enigmatic texts, Djehuty’s tomb displays one of the most complete versions of the Opening of the Mouth ritual (Serrano 2014) and hymns to Amun-Ra and Amun (Galán 2015), while his burial chamber—among the few of his time to be decorated—contains a wide selection of the Book of the Dead chapters (Galán 2014; Díaz-Iglesias Llanos 2017, 2019). In sum, it has been emphasized that the whole of Djehuty’s tomb presents “a monument devoted to written culture” (Galán and Díaz-Iglesias Llanos 2020, p. 159; for an overview, see also Espinel 2014, pp. 327–28; Ragazzoli 2016, pp. 159–60).

According to Galán (2014, p. 249), Djehuty’s most prominent professional title, Overseer of the Treasury, appears in his tomb at least four times preceded by the title sS, “scribe” (overall, the title “scribe” occurs six times there, cf. Table 1). In this context, sS is to be considered a more general indication: as an erudite’s social classifier (on scribal identity and self-discourse, see, e.g., Ragazzoli 2010, 2013, pp. 276–82; 2019; Navrátilová 2015, pp. 268–72; Allon and Navrátilová 2017, passim).

The semantic field of the notion “scribe” may also include artists, which is discussed in more detail in the next section. Interestingly, among Senenmut’s numerous monuments, which seemingly demonstrate a very conscious fashioning of himself, none refers to him as a scribe (cf. Dorman 1988, p. 175; Allon and Navrátilová 2017, p. 26).

5. Djehuty the Artist

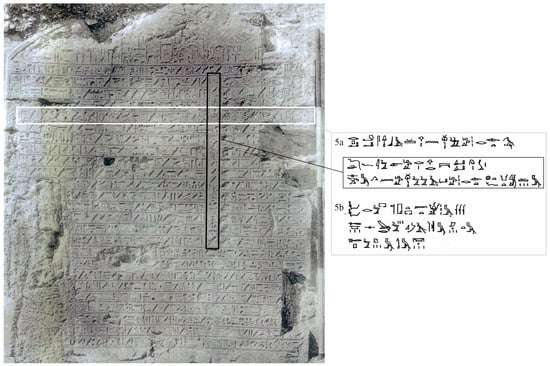

The primary document quoted in the context of Djehuty’s involvement in Hatshepsut’s building activities is his autobiographical inscription, known as the Northampton stela, placed on his tomb’s facade (Urk. IV, 419.13–431.5; Spiegelberg 1900; Breasted 1906, pp. 153–58; Marquis of Northampton et al. 1908, pp. 15–17, Pl. I; Galán 2014, pp. 248–50; Galán and Díaz-Iglesias Llanos 2020, pp. 152–55). Set below the lunette with the first line containing an invocation to Amun-Ra and the cartouches of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, the 15 lines that follow (2–16) present Dehuty’s titles and epithets. They are interrupted by a text column serving as a refrain and introducing the 15 projects Djehuty took charge of, which continue in the horizontal lines. Each project is provided with brief characteristics emphasizing the valuable products used in it to underscore Djehuty’s responsibilities as an Overseer of the Treasury. Just below this, in six uninterrupted horizontal lines (17–22), Djehuty describes his involvement in tabulating products from Hatshepsut’s expedition to the land of Punt, which she organized in year 9 of the joint reign (Galán and Díaz-Iglesias Llanos 2020, pp. 159–60 and ff.).

Djehuty’s work in Deir el-Bahari is recorded in line 5 of the stela (Figure 12):

| [Horizontal 5a] | The hereditary prince who instructs Hmww to work, Djehuty, |

| [Vertical (refrain)] | he says: “I acted as a chief spokesman (rA-Hry) who gives instruction(s) (tp-rd), I led Hmww to work according to the tasks (to be done) in |

| [Horizontal 5b] | Djeser-djeseru, the Temple of Millions of Years; its great doors made of copper (and) decorated (Xpw) with electrum” (Urk. IV, 422.6–11). |

Figure 12.

Autobiographical stela of Djehuty (Marquis of Northampton et al. 1908, Pl. 1); detail: line 5 of the text mentioning Djehuty’s work in the Temple of Hatshepsut and the “refrain” column (Urk. IV, 422.6–11).

The term Hmww appears twice in this passage (once in the vertical text of the “refrain”, i.e., pertaining to the rest of the projects being enumerated, as well) and is a key element here: while this term has long been taken to relate simply to the craftsmanship sphere (see, e.g., this quoted passage’s translation in Galán 2014, pp. 249–50; Galán and Díaz-Iglesias Llanos 2020, p. 153, and the translation of a corresponding text on the stela of Irtysen (Louvre C 14) in Bryan 2017, p. 4 [lines 6 and 8]), the most recent research (Laboury 2016, pp. 374–76; Ragazzoli 2019, pp. 395–98; Laboury and Devillers 2023, pp. 166–67) convincingly demonstrates that the designation Hmww is to be understood instead as “art-practitioners/experts”, just as the term Hmwt (Wb III, 84, 9–16) refers to the concept of art that encompasses, inter alia, the ability to invent and create (see n. 1 in this article). Important to considerations that appear briefly above on the artist’s creative force, usage contexts of the term Hmwt, which can also refer to medicine, ritual, and magic, demonstrate that “Hmwt is about an art and expertise that is efficient in making things happen or even in making things about, and not a matter of mimesis” (Stauder 2018, p. 252).

To return to Djehuty’s self-presentation on his Northampton stela, its text’s sophisticated composition in lines 2–16 makes the section stand out. It may be read line by line, including the refrain each time as presented above, or alternatively as two independent text blocks: (1) the list of Djehuty’s titles and epithets and (2) that of his deeds or projects, each with its own internal structure. While the projects list (2) is thought to be composed chronologically (Niedziółka 2003, p. 411; Shirley 2014, p. 196 with n. 78), it is with the list of Djehuty’s titles and epithets (1)—each line starting with jrj-pat HAtj-a, “Noble and Count”—that a reader is provided with an immediate glance into his verbal self-portrait. Here, following Djehuty’s actual professional and priestly obligations, from which he has selected those of Overseer of the Treasury and Overseer of Priests in Hermopolis (lines 2–3, respectively, Urk. IV, 420.16–421.7), is a litany characterizing the excellence of his mental abilities and accuracy in performing duties assigned to him by the pharaoh, which then heads into the final lines that may be seen as a culmination of Djehuty’s self-definition (lines 15–16, Urk. IV, 427.3–12):

JJ Shirley (2014, p. 196 with n. 75) assumes a probability that Djehuty was overseer of the Hmww before being assigned any oversight of Hatshepsut’s monuments and becoming Overseer of the Treasury. Setting aside the chronological progression of his career—given that our understanding is accurate of the Northampton stela’s composition of his self-presentation—the function of the overseer of the royal Hmwt, structurally summarizing the listing that describes him as a professional and a person, seems of utmost value for Djehuty, on par with his self-designation as an excellent scribe.

| [line 15] | the Sealbearer of the King of Lower Egypt, the Overseer of all the Hmw-ship24 of the King of Upper Egypt, |

| [line 16] | a Great Friend of the Lord of the Two Lands, an excellent scribe who acts with his hands. |

The term “excellent scribe”, so commonly met in the autobiographical proclamations, is reminiscent, on the one hand, of the artist Irtysen’s initial self-definition on his Louvre stela, jnk grt Hmww jqr m Hmwt.f, “I am, indeed, an artist excellent in his art” (on this in a broader context, see Stauder 2018, pp. 250–51; Laboury and Devillers 2023, p. 173). On the other hand, Djehuty’s final emphasis, put on being a scribe, resembles the autobiographical inscription of the Mayor of Thebes Ineni (Shirley 2014, pp. 176–77) in his tomb, TT 81. There, Ineni’s lengthy achievements in various building projects under Thutmose I (Hatshepsut’s father), including his tomb in the Valley of the Kings (Urk. IV, 53.15–62.9; Dziobek 1992, pp. 44–54), culminate with the scribal title (Urk. IV, 62, 9). For our considerations here, it is important to note that at some point in his career, Ineni was Overseer of the Treasury, just like our Djehuty (Dziobek 1992, pp. 77, 80, 122–23 [texts 18a, 18n], Pl. 27; Awad 2002, pp. 213–14, with n. 1).

Studies on artists in ancient Egypt underscore that the title sS can have multiple meanings, as the verbal root sS meant “to write” but also “to draw, paint, decorate, and even conceive a decoration of a monument” (Laboury 2020, p. 87; 2016, pp. 379–81; see also above, Figure 5). In addition, sS may be an abbreviated version of the title sS qd(wt), or “scribe of forms”, that is, “an artist, draughtsman, painter” (Navrátilová 2015, pp. 247–48; Hartwig 2023, pp. 91–92; on the profession of sS qd(wt), see, e.g., Laboury 2012, pp. 200–3; Stefanović 2012; Allon and Navrátilová 2017, pp. 54, 99–101). The latter function is notably exemplified by the case of the scribe of forms of Amun, Pahery from Elkab (Allon and Navrátilová 2017, pp. 13–24), who states in his autobiographical inscription “it was my pen that made me famous”25 and who is identified—by his own self-portrait in assistenza—as a maker of the decoration of his grandfather’s tomb, Ahmose son of Ebana (T Elkab 5) (Laboury 2012, p. 201 with n. 11; 2023, pp. 131–32; Laboury and Devillers 2023, pp. 172–73). “According to the image of Paheri in the tomb of Ahmose, to be a scribe means to be an artist who creates living memories”, state Allon and Navrátilová (2017, p. 22).

This meaning of the word “scribe” as defining someone who designs things is of special importance for our considerations here, all the more so given that a certain Djehuty appears as many as six times among scribes who left their secondary inscriptions in the tomb of Antefoqer/Senet, TT 60, including “positive reactions” to the decoration they found there (this expression borrowed from Den Doncker 2012, p. 24).26 In the Eighteenth Dynasty, this Middle Kingdom tomb was eagerly visited—with aesthetic and antiquarian interests, as it is commonly held—in search of inspiration from ancient models to be implemented in ongoing building projects (Ragazzoli 2013, p. 284; 2023; Den Doncker 2012, 2017, 2023; Espinel 2014, p. 320; see also Stupko-Lubczynska 2021; on visitors’ inscriptions outside the Theban Necropolis in Memphis, Beni Hassan, and Asyut, attesting to the same practice and motivation, see Navrátilová 2015, 2023; Hassan 2016; Verhoeven 2023).

Out of 67 graffiti in TT 60 (Ragazzoli 2013), the number of Djehuty signatures—written “in a beautiful literary hieratic typical of the time of Hatsheput/Thuthmose III” (Ragazzoli 2023, p. 141)—is impressive; in that tomb, in fact, Djehuty is the most frequently attested “scribe” (Ragazzoli 2013, p. 277, Fig. 5). One of Djehuty’s graffiti (60.24) is particularly remarkable (Ragazzoli 2023, pp. 141, 143–44, Figs. 8.4, 8.5). It represents a sitting scribe with the attributes of his trade and is accompanied by a text in cursive hieroglyphs and in retrograde (the latter technique shows off a writer’s scribal skills). All told, “the graffito bears witness to a remarkable understanding of the funerary decorum where it is inserted” (Ragazzoli 2023, p. 141).

Can we identify the “scribe” Djehuty who paid a visit to TT 60 with Treasurer Djehuty? According to Alexis Den Doncker (personal information, 10 August and 22 December 2023; also Den Doncker 2023), there is contextual evidence suggesting this identification. Grafitto 60.7 (Ragazzoli 2013, p. 302) commemorates a visit by three “scribes” in TT 60: Djehuty, Nehesy, and Rau (the latter name is only known for the official who replaced Senenmut as Steward of Amun, cf. Shirley 2014, pp. 235–36). In Hatshepsut’s Punt Portico, nearly this same group appears, with Treasurer and scribe Djehuty on the West wall (see below, Section 6.3) and on the North wall, Nehesy, Sealbearer of the King of Lower Egypt (Htmtj bjtj) (on Nehesy, see Shirley 2014, pp. 193–95), Senenmut, and a third, anonymous official are depicted together (Naville 1898, Pl. 86; Urk. IV, 354.15–7; Galán and Díaz-Iglesias Llanos 2020, p. 165; some would like to recognize Djehuty as the third man, cf. Helck 1958, pp. 347, 399). In addition, the link between “scribe” Djehuty and Treasurer Djehuty may be supported by iconographical and textual references to TT 60 in Djehuty’s tomb, TT 11 (Serrano in press), which one may understand as a result of the “working” visit(s) he made to TT 60, as with the more explicit case of Amenemhat, steward of the Vizier under Thutmose III and owner of TT 82, who also left his “scribal” signature in TT 60 (Den Doncker 2012, pp. 30–31; 2017, pp. 335–36, 343–45; Ragazzoli 2013, pp. 284, 313 [graffito 60.33]).

In light of this evidence for Djehuty as a scribe (which we can understand as both a “literatteur” and as an “artist”), and reflecting his words on the Northampton stela:

may we understand this as an ancient Egyptian way to say, “I was the one responsible for the design (and/or overseeing the execution) of its decorations”? In this respect, one may consider the case of Meryra, a scribe of the god’s books, in the Twentieth Dynasty tomb of Setau at Elkab (T Elkab 4), about whom exactly the opposite is being claimed—that he was sole conceiver of that tomb’s decorative design—with notable use of the same phraseology (Kruchten and Delvaux 2010, pp. 88–93; Pls. 16–7, 53 [text 2.3.1.3.2], 78 [top]):27I acted as a chief spokesman (lit. superior mouth, rA-Hrj) who gives instructions (tp-rd), I led Hmww to work (sSm.n.j Hmww r jrt) according to the tasks (to be done) in Djeser-djeseru,

it is his own heart who leads him (sSm.f), without any chief spokesman (rA-Hrj) who gives him instructions (tp-rd). (For) he is a scribe excellent with his fingers (…).28

Notably, the Mayor of Thebes Ineni, mentioned above, who is very explicit about his participation in royal construction projects under Thutmose I—and whom we can consider Djehuty’s immediate predecessor in the position of the king’s designer—summarizes his involvement in those projects in similar wording (Urk. IV, 57.15–58.6; Dziobek 1992, pp. 51, 53 [l. 13–4], Pl. 63 [6a–5]):

What I planned was for my descendants,It was the Hmw-ship of my heart, my performance (sp) (consisted) in knowledge.Instructions (tp-rd) were not given to me by the elder.I led (xrp) by being […],by being a chief spokesman (rA-Hrj) of every work.

Djehuty’s acting as a superior mouth who gives instructions to Hmww is also indicated in other data provided by what is termed the Dra Abu el-Naga apprentice’s board. This artefact was discovered in the vicinity of TT 11 (Galán 2007) and seems to complete Djehuty’s virtual portrait. On its recto, the board contains two depictions of the pharaoh’s statue (shown frontally, i.e., not in accordance with principles of ancient Egyptian two-dimensional human figuration); the right figure is clearly executed by a more assured hand, indicating that the board was a training device, on which an apprentice practiced by copying the master’s model. Also on this side is an opening passage from what is known as the Book of Kemit (a collection of epistolary formulae, cf. Allon and Navrátilová 2017, pp. 111–13; Motte 2024); here, two columns of that text are written three times, once by the master, twice by a student.29 On the board’s verso, a single figure of the king is drawn, hunting fowl. This meaningful artifact containing exercises in three different fields of Hmwt—statuary, two-dimensional decoration, and writing—is assumed to have once formed Djehuty’s burial equipment (Galán 2007, p. 115). If so, it would have served as a tool in (re)constructing the tomb owner’s identity, linking him to his profession, regardless of his status as the board’s master-artist or apprentice, given that every master was once an apprentice.

6. Djehuty the God

6.1. Djehuty, the Divine Lector-Priest

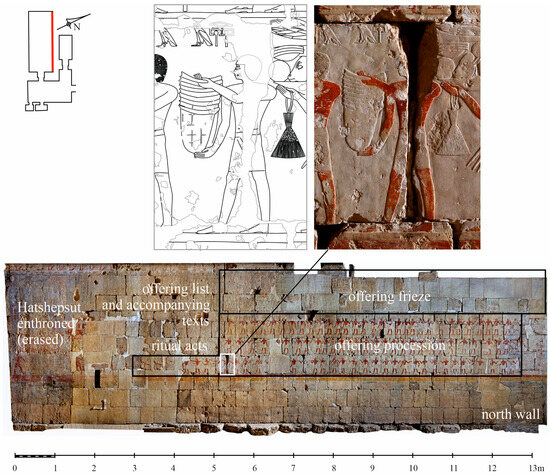

The evidence presented thus far seems to characterize Djehuty as a true polymath, something of a Leonardo da Vinci of his epoch. Returning to the Chapel of Hatshepsut and its North wall, there is a compositional element that has been left out of the analysis thus far, but which—if we are accurate in identifying the figure labeled jmj-rA pr[wj-HD] as Djehuty of TT 11—adds a new layer of meaning to the entire scenario. The element in question is located behind the offering bearers and represents no less than the god Djehuty (Thoth), paired on the opposite wall by the god Iunmutef, with both deities represented with a hand raised in the gesture of recitation (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

The Chapel of Hatshepsut with the figures of Iunmutef and Djehuty/Thoth closing the offering processions on the South and North walls, respectively (photos: M. Jawornicki, J. Kościuk/@PCMA UW; drawings: the author; black lines: preserved relief, grey: reconstruction; in Thoth’s case, two reconstruction versions are proposed for the text in front of his figure).

These two elements have been commented on elsewhere (Stupko-Lubczynska 2016a; 2016b, pp. 279–318); here only a brief summary will be presented, relevant to the present argumentation. Both gods evidently constitute a new element in the codified offering scenes, not documented in this context before Hatshepsut’s times (along with the Chapel of Hatshepsut, Iunmutef and Thoth are included in offering scenes in niches of the temple’s third terrace, cf. Stupko-Lubczynska 2016a, p. 145, Fig. 3; 2016b, pp. 287–88). In tracing this motif’s evolution, one can conclude that Iunmutef and Thoth are the divine personifications of two priests, the sem-priest and the lector-priest (Xrj-Hbt), respectively, with these latter two present in offering scenes since the Old Kingdom (Stupko-Lubczynska 2016b, pp. 69–72, 283, with references to further literature) (Figure 14). In their priestly roles, Iunmutef and Thoth refer to the two essential components of the mortuary cult: carrying out ritual activities performed by the sem-priest acting as a substitute for the deceased’s heir and reciting accompanying sacred texts, led by the lector-priest.

Figure 14.

A sem-priest and a lector-priest (highlighted in grey) in the representation of the ritual acts performed in front of the deceased; (a) the tomb of Khnumhotep at Beni Hassan (BH 3), Middle Kingdom (drawn by the author after Newberry 1893, Pl. XXXV, detail); (b) the tomb of Antefoqer/Senet, TT 60 (drawn by the author after Davies 1920, Pl. XXVIII).

In iconographic terms, the two gods take over characteristic features of their priestly prototypes: Iunmutef, whose name translates as Pillar-of-his-Mother, is shown clad in the leopard-skin robe typical of the sem and possessing his lock of youth, while the god Djehuty is represented wearing the lector-priest’s diagonal sash across his chest and holding a papyrus scroll in his hand.

6.2. The Hermopolitan Connection: Possessing Restricted Knowledge

One of the most popular epithets of Djehuty/Thoth, generally considered the god of writing and knowledge, was the Lord of the God’s Speech (nb mdw-nTr), pointing him out as the divine author of sacred texts (Leitz 2002, pp. 654–55; Spiess 1991, pp. 149–52; Schott 1972). It was used interchangeably with another epithet, the Lord of Khemenu/Hermopolis, after Thoth’s main cult center (Leitz 2002, pp. 716–18).

Significantly, the text Thoth pronounces on the North wall of the Chapel of Hatshepsut (Stupko-Lubczynska 2016a, pp. 133–34; 2016b, p. 281) can be traced to offering formulas popular in the Middle Kingdom in the Hermopolis area (el-Bersha, Meir, and Asyut) in which the offering to the deceased is given by Thoth, the double shrines (jtrtj), and the Heliopolitan Ennead, according to writing that Thoth has given (or made) in the house of the god’s books (xft sS pn rdj/jr n DHwtj m pr mDAt-nTr [with variants]) (Griffith and Newberry 1895, pp. 35, 40, 45, Pl. XVII; Blackman 1915, p. 16, Pls. VI–VII [Figure 15 in the present article]; Schott 1963; Barta 1968, pp. 56, 60 [Bitte 15d–g]; Spiess 1991, p. 82 [Doc. No. 37]; Willems 2007, pp. 36 [2], 73 [1], Pls. XLVI, LII).30

Figure 15.

Offering scene in the tomb of Ukhhotep son of Senbi (Meir B2), Middle Kingdom; in square: the offering formula mentioning Djehuty/Thoth and the house of the god’s books (Blackman 1915, Pls. VI–VII).

When we return to the career of Treasurer Djehuty (Table 1), his relations to the Hermopolitan region are evident from his titles: Overseer of Priests in Khemenu, High Priest/Great of Five in the House of Thoth, Overseer of Priests of Hathor, Lady of Qis (Cusae), and Governor of Herwer (located north of Hermopolis). This may have served to indicate Djehuty’s place of origin (Galán 2014, p. 250 with nn. 15–19; Díaz-Iglesias Llanos 2019, p. 149; Galán and Díaz-Iglesias Llanos 2020, pp. 155–56 with nn. 16–17); from there, it may be assumed, his professional path had started.

There seems to be a subtle interlink in the Chapel of Hatshepsut between Treasurer Djehuty and the god Djehuty; at the very least, we as viewers are invited to forge such a link (on who could be a recipient of this message in the times of Hatshepsut, see below; see also our note 6 on the concept of internal and external viewer). If that was indeed the author’s intention, with the god Djehuty occurring here as the Lord of the God’s Speech, the patron of the house of the god’s books, and the divine lector-priest, it seems to point to the expertise often bestowed upon artists involved in conceiving a monument’s decoration, namely, the access they have to restricted knowledge. Many of these artists bear titles “lector-priest” and/or “scribe of the god’s books”, as is the case with Meryra of the Twentieth Dynasty who has been mentioned above as one who was led by his heart, and Isesi, his Old Kingdom colleague who worked in tandem with his brother (cf. Figure 5), and Irtysen, the Middle Kingdom artist whose claims on his stela include possessing knowledge of “the secret of the god’s speech” (sStA n mdw-nTr) (Stauder 2018, pp. 251–53; for more on the role of the scribe of the god’s books in conceiving decorative schemes, see Vernus 1990, pp. 39, 49 with n. 13; see also Chauvet 2015, pp. 68–69; Laboury and Tavier 2016, p. 65, n. 31; Laboury and Devillers 2023, pp. 173–74; for more general discussion on restricted knowledge, see Baines 1990, pp. 8–10; Eyre 2013, pp. 297–98, 310–11).

Given that Djehuty originated from the Hermopolis region, he could have been familiar with tombs in the Meir necropolis, where local governors of the city of Qis were buried, many of whom had been—as with our Djehuty—“the overseer of priests of Hathor Lady of Qis” (Beinlich 1984, cols. 73–74; Warkentin 2018, pp. 222–23; Galán and Díaz-Iglesias Llanos 2020, p. 156, n. 16, with further literature).31

Standing out in the rather compact Meir burial site are the Old Kingdom (Sixth Dynasty) rock-cut tombs of Pepyankh the Middle (Meir D2) and his grandson Pepyankh the Black (Meir A2). In both tombs, their main artists would have been identifiable, appearing in a number of scenes that include several self-portraits in assistenza (Kanawati and Woods 2009, pp. 10–14; Lashien 2017, pp. 139–64; Hassan and Ragazzoli 2023, pp. 226–27). In the grandfather’s tomb, the artist was one Kaiemtjenenet, while in the grandson’s tomb, it was a certain Ihyemsapepy Iri, who must have belonged to the artistic elite (and who seems to have been active also in Memphis, cf. Lashien 2017, pp. 159–61). These artists are most often entitled (interchangeably or complementary) as “lector-priest”, “scribe of the god’s books of the Great House”, at times, “scribe of forms”.

Remarkably, Pepyankh the Middle (Meir D2), the grandfather, who was the overseer of the priests of Hathor Lady of Qis, was himself a lector-priest, a scribe of the god’s books, and a scribe of forms. These titles are mentioned on the facade of his tomb (Blackman 1924, Pl. IVA [1]; Kanawati 2012, pp. 32–33, Pl. 75a–b), which indicates the high esteem this official, also the Vizier and the overseer of the Double Granary, paid to the artistic part of his career (for the full titulary of Pepyankh the Middle, see Blackman 1924, pp. 1–3; Kanawati 2012, pp. 11–13).

Pepyankh the Black (Meir A2) carried similar administrative titles to those of his grandfather but with no connection to the clergy of Hathor from Qis; he was, however, a lector-priest and—as with our Djehuty—jmj-rA pr-HD (Blackman and Apted 1953, pp. 16–17; Kanawati and Evans 2014, pp. 11–13). The tomb of the grandson is only partly decorated in relief with very detailed modeling, while the majority of its walls are left at the preparatory-drawing stage, executed in black lines (Hassan and Ragazzoli 2023, p. 224, with Figs. 7–9). Within these unfinished compositions, a number of names and titles were added as secondary captions; notably, one identifies the figure of a lector-priest who takes part in the burial rites with Ihyemsapepy Iri, the main artist (Kanawati and Woods 2009, p. 13, Phot. 16; Hassan and Ragazzoli 2023, p. 222 with Fig. 6 and ff.) (Figure 16).32

Figure 16.

The tomb of Pepyankh the Black (Meir A2), Old Kingdom. The main artist of the tomb decoration, Ihyemsapepy Iri, as a lector-priest (Photo: Chloé Ragazzoli).

In this tomb, the overall emphasis put on artistic themes is outstanding (cf. the scene of the tomb owner visiting the artistic workshop, labeled “viewing all the works of the Hmw-ship”, Blackman and Apted 1953, pp. 25–26, Pl. XVI [Figure 21 in the present article, below], and two unique scenes displaying Ihyemsapepy Iri at work, placed immediately in front of the tomb owner’s face, labeled “viewing the work of the scribe of forms”, Blackman and Apted 1953, pp. 27–29, Pls. XVIII–XIX, XXI; see also Kanawati and Woods 2009, p. 10 with Fig. 7; Hassan and Ragazzoli 2023, pp. 226–27 with Fig. 10c; Laboury and Devillers 2023, p. 177 with Fig. 15.5).

Among his self-portraits in assistenza in Meir A2, Ihyemsapepy Iri occurs as an offering-bearer in two offering scenes, which is reminiscent of the inclusion of our Overseer of the Treasury in the Chapel of Hatshepsut. On the North wall of Room 5, Ihyemsapepy Iri is the third figure in the lowermost row of the procession, among the lector-priests bringing hpS-legs, followed by one Seshshen, who is thought to have worked in this tomb as Ihyemsapepy Iri’s assistant (Hassan and Ragazzoli 2023, p. 226). On the West wall of the room, Ihyemsapepy Iri is again represented in the corresponding place and with the same attitude, this time as the second person, while on the South wall, where the composition of the West wall is continued, Seshshen is depicted as the third figure in the row, presenting fowl (Blackman and Apted 1953, pp. 42–45, Pls. XXXIII.1, XXXIV, XXXVI; Hassan and Ragazzoli 2023, Fig. 10 b, e).

Djehuty’s familiarity with the tombs in Meir is a matter of speculation, as is any sense he may have felt of being the successor of great men of the past buried there. For sure, he shared with them some of his administrative and priestly functions. Also, these people appear to have been interested in art and were close to artists, with some being the artists themselves (as the argumentation here contends Djehuty was). Given all that, it may be postulated that Djehuty got inspiration for his self-portrait in assistenza from the tomb of Pepyankh the Black (Meir B2) with the recurrent representation of Ihyemsapepy Iri as a renowned artist (on a local and maybe even countrywide scale). In this unfinished tomb, both its reliefs and preparatory drawings were executed with the utmost mastery, which makes it a remarkable monument to the “encapsulated” work in progress. Bearing this in mind, one cannot avoid imagining the interest the tomb may have aroused in such an artistic person as (we assume) our Djehuty, who may have been interested in studying its workmanship, just as the present-day art historian would.33

6.3. Counting the Marvels of Punt

An exploitation of the homonymity between Djehuty’s name and that of the god and a pun on the associations aiming to highlight similarities in professional (and mental) characteristics—that in art historical terms function as self-portrait in figura (Chastel 1971, p. 538)34—is not limited to the Chapel of Hatshepsut in the Deir el-Bahari temple.

Another example is found in the Punt Portico of the temple’s second terrace (Figure 17), as has been noted by several scholars (Naville 1898, p. 17, Pl. LXXIX; Breasted 1906, pp. 153–54; Bickel 2013, p. 207; Galán 2014, p. 251 with n. 20; Galán and Díaz-Iglesias Llanos 2020, pp. 163–64; Taterka 2019, pp. 195–96; 2020, pp. 122–23). Here, the “measuring of the fresh antjw-myrrh (…) and the marvels of Punt” (Urk. IV, 335.13–4) is depicted as an act performed by four anonymous men, behind whom a fifth figure had stood, erased most probably in the times of Hatshepsut (see below). The accompanying inscription’s remains may be read as [sS jmj-rA pr-HD DHwtj], thus identifying this figure with the owner of TT 11 (also notable, again, is Djehuty’s professional title, Overseer of the Treasury, preceded by the title “scribe”). Behind the scene, the god Djehuty is shown, who according to the inscription is “recording in writing, calculating quantity, (and) summing up in millions, hundreds of thousands, tens of thousands, thousands and hundreds, receiving the marvels of the lands of Punt” (Urk. IV, 336.6–9; the English translation follows Taterka 2020, p. 123).35

Figure 17.

The Punt Portico in the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari. A scene of measuring the antjw-myrrh with the traces of the erased figure of Djehuty (photo: M. Jawornicki/@ PCMA UW; tracing by the author, black: preserved relief lines, grey: reconstruction).

This situation is similar to the one in the Chapel of Hatshepsut; however, one difference is that in the Punt Portico both Djehuties, the man and the deity, appear in their ability as somebody who is skilled in counting and measuring, an aspect of Djehuty—so obvious for an Egyptian audience—as a moon god connected with all calculation matters (cf. Kurth 1986, cols. 505–6; Spiess 1991, pp. 164–65; Assmann 2001, pp. 80–81), including NB architecture, which requires knowledge of astronomy, among other things.36

Notably, the interrelation between Djehuty the man and Djehuty the god does not go exclusively in a uniform top-bottom direction (the man emulating the abilities or functions of his divine patron) but is instead a mutual one: the god Djehuty in the Punt Portico reliefs is given responsibilities that, in reality, were entrusted to Treasurer Djehuty, his earthly namesake. The latter’s excellence in counting “all the marvels of Punt” is underscored in his autobiographical inscription in the Northampton stela (esp. in lines 17–18, Urk. IV, 428.5–12), and activities similar to those shown in the Punt Portico are found in the transverse hall of TT 11, with the figure of Djehuty depicted overseeing the entire composition (a more detailed discussion is in Galán and Díaz-Iglesias Llanos 2020, pp. 159–65). Also noteworthy is that this scene in TT 11 is placed in the transverse hall to the left of the main axis, recalling the Punt Portico’s position in Hatshepsut’s temple.37

One can wonder if this mutual association between the god and the man—made too obvious and possibly sacrilegious for a viewer of the period—was the reason Djehuty’s figure was erased from the Punt Portico scene, as has been assumed (Galán and Díaz-Iglesias Llanos 2020, p. 165; contra Taterka 2020, p. 123, n. 577). Erasing Djehuty’s figure is certainly typical of alterations during Hatshepsut’s times, executed when temple decoration was still in progress, as is attested, e.g., in the Chapel of Hatshepsut, where changes seem semantically irrelevant and affect a bird’s species or offering bearers’ attire [per this author’s personal observation]. One has to point out, however, that Senenmut’s name, where his figure appears on the North wall of the Punt Portico in front of Hatshepsut’s throne, was erased in a similar manner as Djehuty’s entire figure (Taterka 2015, pp. 33–34), though there is no reason to link Senenmut to the god Thoth and the intention would seem to have been different for the erasure of this name. Attempting to be objective, there is no proof that erasure in the case of both officials was simultaneous or that the motivation in both cases was these officials’ damnatio memoriae (as some scholars seem to suggest: Helck 1958, pp. 347, 400; Taterka 2015, pp. 33–34; also, Taterka 2020, p. 123, similar to Galán and Díaz-Iglesias Llanos 2020, pp. 165–66 [for Djehuty alone, though with some reservations]). Furthermore, nothing clearly indicates where such a command may have come from (or that Hatshepsut ordered it). In the case of Djehuty’s figure, a possibility exists—given the delicacy of the figure’s removal—that this was the designer’s own alteration, a step so well-known over the course of art history. Galán and Díaz-Iglesias Llanos (2020, p. 163) rightly note that Djehuty’s figure is “squeezed” into the scene, suggesting its subsequent addition. Remarkably, this addition had been made before the carving in this place was started, as the relief itself and the background surrounding it show no alterations (as it would be if the figure was incised into the already smoothed background [for such a case, see Stupko-Lubczynska 2022, pp. 96–97, Fig. 10]). In considering this scenario, it could have been Djehuty who first decided, at the stage preceding the relief execution, to add his own image to the already planned scene and then to remove its already sculpted form—for many various reasons that now evade us, whether compositional, ideological, or otherwise.

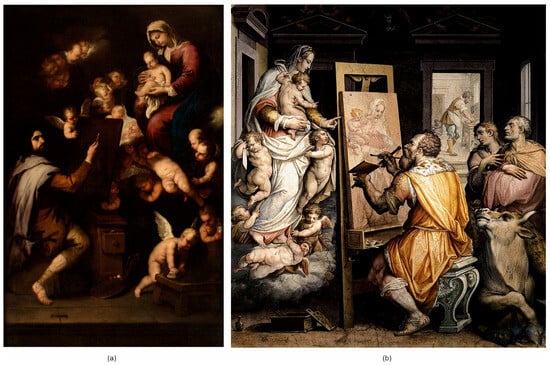

6.4. Self-Portrait in Figura

In Western European art, a prime example of the self-portrait in figura is the image of Saint Luke the Evangelist represented as a painter (Figure 18). This saint can be considered a Christian counterpart of the god Djehuty, lord of knowledge and writing, the divine author of sacred texts, and patron of artists and scribes, for Christian tradition recognizes Luke as a scholar (author of the Third Gospel and the Acts of Apostles), a physician, painter of the first icon of the Virgin Mary (Raynor 2015; Peter 2016, pp. 93–94; Libina 2019), and patron of many artistic guilds in Western Europe (including the Accademia di San Luca in Rome, e.g., Matthijs 2021).

Figure 18.

(a) Luka Giordano, St. Luke painting Virgin Mary: a self-portrait in figura, 285.2 × 186.1 cm, between 1650 and 1654, Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico; (b) Giorgio Vasari, St. Luke Painting the Virgin Mary, c. 1565, Basilica della Santissima Annunziata.

Emphasizing ties between artist and patron, which in Treasurer Djehuty’s case seem to allude to the god Djehuty’s intellectual abilities, playing on their homonymous names, can be compared to one of the Renaissance era’s earliest embedded self-portraits, in which Taddeo di Bartolo set his own likeness as the face of Saint Judas Thaddeus, shown among other saints at the feet of the Virgin Mary (Figure 19). Taddeo’s face stands out through its more differentiated features and expression, through the indicative glance out of the painting, and also through the depiction of his hands, recalling “the scholastic orator’s technique of checking off points by counting on his fingers. The gesture could then precociously call attention to the analogy later drawn between painting and rhetoric, but is more probably an early signal of the painter’s recognition of the importance to him of the hand that wields his brushes” (Ames-Lewis 2000, p. 215). This interpretation echoes Djehuty’s summarizing statement in the Northampton stela of being “the overseer of all the Hmw-ship” and “the excellent scribe who acts with his hands”, interconnecting two aspects: his expertise and scribal erudition (i.e., the idea) and mastery of his hands (i.e., the execution, putting the idea into being).

Figure 19.

Taddeo di Bartolo, Assumption of the Virgin, 1401. The altarpiece of the Montepulciano cathedral. Detail: the author’s assumed self-portrait in figura.

7. Conclusions

Florence Ames-Lewis, writing about Renaissance-era self-portraits in assistenza, states that they are “vehicles for suggesting the artist’s intellectual skills or aspirations: they demonstrate his knowing concern with antiquarianism, or his understanding of allegory, or his desire to be rated alongside humanists. Few Renaissance self-portraits, if any, are likely to have been simply depictions of the individual: the self-portrait is a natural medium by which the artist can communicate aspects of his self-image”. In line with this, if the cumulative evidence from the North wall in the Chapel of Hatshepsut reveals self-portraits in assistenza and in figura that, when combined, point to Djehuty, Overseer of the Treasury and owner of TT 11, the following aspects of that self-created image are being communicated:

- (a)

- his professional identity as an Overseer of the Treasury and also as a lector-priest, with the latter title in all its sociocultural implications of an initiate into restricted knowledge, an intellectual, and an artist-designer. Our Overseer of the Treasury, by underlining links with the god Djehuty, Lord of Divine Speech, and playing on aspects including their homonymous names while exploring associations within the circle of the scribal milieu, seems to posit himself as an earthly incarnation of this god, pointing to twin aspects of his mental abilities: erudition and the more public extension of artistic creativity (in the Chapel of Hatshepsut), along with strict aspects connected with calculations and measurements (in the Punt Portico). This complementary vision of a person recalls the case of Pahery in Elkab, noted above, who, according to Allon and Navrátilová (2017, pp. 13–14, 17–24), emphasizes in his tomb his occupation as an administrative scribe, busy with reckoning matters, and in his grandfather’s tomb creates his image as a literate artist.

- (b)

- the Chapel text accompanying the god Djehuty seems to comment on its author’s awareness of past sources, possibly pointing to Hermopolis, the region of his origin. Bearing in mind that Djehuty’s proclamation constitutes part of the earliest version of the spell incorporated in what is referred to as the Ritual of Amenhotep I (Stupko-Lubczynska 2016a), and assuming that Treasurer Djehuty could have been its author, might this assumption be extended onto the other “first versions” of religious compositions on the walls of the temple of Hatshepsut, including the Stundenritual on the ceiling of the Chapel of Hatshepsut (Barwik 1998) and the Book of Night, the Theological Treatise, and the Baboon Text in the Solar Complex (Karkowski 2003, pp. 161–64, 167–78, 180–220, Pls. 29–31, 37–39)? This issue requires further research.

- (c)

- as an Overseer of the Treasury, the first figure in the offering procession proper, and the divine ritualist closing it, Djehuty would have emphasized his social position, i.e., the closeness of his relations with Hatshepsut, patroness of the entire monument and the Chapel’s focal figure. In the scenes in question, Djehuty’s presence is established to perform the mortuary ritual for her, while this place in offering scenes is usually occupied by the deceased’s heir—for instance, in a neighboring room to the Chapel of Hatshepsut, the Chapel of Thutmose I, the female pharaoh is depicted on both walls, acting in this place for her father (Barwik 2021, pp. 42, 58, Pls. 12, 13).

Djehuty’s case in the Chapel of Hatshepsut, in the complexity of its structure and in the subtlety of its message, is comparable to ancient Egyptian cryptography, as both operate on several levels (adding rather than hiding information), as has been discussed above, and display an exclusive insider’s knowledge.38 Cryptography usually aims “to attract attention, to cause the passer-by to pause and read” (Stauder 2018, p. 262). One has to note that the Chapel of Hatshepsut, as with other sanctuaries in the temple, was a place of severely restricted access; thus, any intent for a message to be communicated to the broader public can be excluded. Once the decoration was finished, its cryptographic message became virtual rather than directed to a certain recipient. This seems to illustrate the author-designer’s will to immortalize himself regardless of whether the message will be legible to anyone (see n. 6 in this article on the “internal” viewer imagined by the author). The religious plane on which the Chapel reliefs were believed to operate cannot be excluded, however.39 An alternative motivation that can be imagined was pure amusement at the design stage, with the author-designer possibly consulting with and commenting to his closest collegial circle, evidently appealing also to artists/artisans executing the Chapel reliefs, who must have constituted quite a large group (on them, see Stupko-Lubczynska 2022 and above). Another assumed audience circle for the encrypted message could have been the priestly personnel who were entering the Chapel to perform the mortuary cult. Among them were lector-priests who, as it has been underlined above, were often involved in the design process. Obviously, two distinct facets of the image reception can be distinguished here: with the first, the artwork is conceived as an object with encoded information about its author; with the second, it is a functioning iconographic environment within its religious setting (same as it has been underscored for portraits of donors; and further, self-portraits in assistenza, in early modern art, cf. n. 3 in the present article). Operating on both these levels, the encrypted “signature” fits precisely into the punning spirit of Hatshepsut’s time (Galán et al. 2014, passim), the time of which Treasurer Djehuty appears as one of the brightest stars.

The expression “punning spirit” has been borrowed from Ames-Lewis (2000, p. 228), who uses it to comment on one of Benozzo Gozzoli’s aforementioned self-portraits in assistenza. This, along with other interrelations noted in this article between ancient Egyptian art and that of the Italian Renaissance (and art in general), serve as bricks in integrating Egyptology into the general art-historical discourse.

8. Further Questions: An Individual Design or Collective Work?

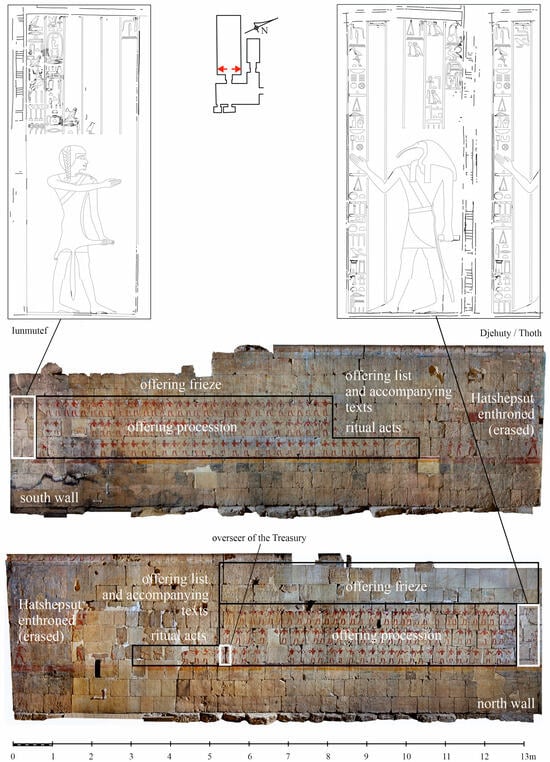

A reader can readily notice that the discussion so far, in concentrating on the North wall in the Chapel of Hatshepsut, presents only half of the picture, as that decoration has its mirror counterpart on the opposite South wall, where the god Iunmutef closes the procession. Previous studies on motifs incorporated into these two seemingly symmetrical compositions indicate that they should be “read” as a sequence, with the South wall preceding the North one (Stupko-Lubczynska 2017). This reading applies, among other things, to the figures of Iunmutef and Djehuty/Thoth, along with their speeches (Stupko-Lubczynska 2016a).

A question arises immediately: What does the title indicate of the figure represented on the South wall in the place corresponding to that of the Overseer of the Treasury, whom the argumentation in this article identifies with Djehuty of TT 11? There, the offering bearer S I/9 is labeled sS a(w) n(w) nswt: the Scribe of the King’s Documents (Figure 20). One must admit that this title is not as telling as that of the Treasurer in the first place because it occurs several times in the Chapel, twice more on the South wall (S I/17 and S III/3) and once on the North wall (N I/8), where, however, its placement just ahead of the Overseer of the Treasury may be significant.

Figure 20.

The Chapel of Hatshepsut, South wall. Detail: an offering bearer with the title of the Scribe of the King’s Documents, a pair to the Overseer of the Treasury on the North wall (Photo: M. Jawornicki/@PCMA UW; tracing by the author).

The title occurs regularly in the Old (Jones 2000, p. 838 [No. 3057]) and Middle Kingdoms (Ward 1982, p. 158 [No. 1360]), but seems to be out of use in the times of Hatshepsut (not attested in Taylor 2001; Al-Ayedi 2006; Herzberg-Beiersdorf 2020). Significantly, when it was used, the holders of this title belonged to the upper circle of officials connected to the Vizier and/or the Overseer of the Treasury. There are cases recorded of a person holding the vizierate and being simultaneously the Overseer of the Scribes of the King’s Documents and the Overseer of the Treasury; quite often, these titles and, in addition, the title of the Overseer of All the King’s Works were united in one person, indicating their responsibility for the royal building projects (for the Old Kingdom: Strudwick 1985, pp. 199–250, 276–335; Krejčí 2000, passim, esp. Table 1; for the Middle Kingdom: Grajetzki 2009, pp. 17–18, 22, 67, 83–84; one such person was Senedjemib Inti, mentioned above [see n. 2 in this article]).

Apart from the title, the figure depicted in the Chapel is not completely indistinctive. From the compositional point of view, this man—bringing the “bunch” of waterfowl and other Delta-related products (several very similar figures occur on the Chapel’s two walls, see Stupko-Lubczynska 2023, pp. 226–29 with Fig. 12.23)—is placed after the first eight figures linked to the Opening of the Mouth Ritual (just as those preceding the Treasurer on the North wall), but before those bringing oils and linen (the latter comprising a separate compositional unit [Stupko-Lubczynska 2017]). Hence, in terms of iconography, the figure with the title Scribe of the King’s Documents looks like an insertion. Here, we observe a situation opposite to that on the North wall, where the Treasurer is completely integrated into the “iconographic fabric” of the rest of the offering bearers bringing meat but stands out with his title.

If the figure with the archaizing title of the Scribe of the King’s Documents on the South wall is of any meaning, whom may we identify with it? Can Djehuty have wanted to point out his identity in two complementary aspects, linking himself with both offering bearers and divine ritualists, Iunmutef (the sem-priest) and Thoth (the lector-priest)—just as Hatshepsut, in the neighboring Chapel of Thutmose I, is depicted on the two walls as the figure performing the mortuary liturgy for her father (Barwik 2021, Pls. 12, 13)?

In light of our argument linking the pair of gods and the priestly pair (the sem- and lector-priests), some premises may indicate such an interpretation. Clues lead us once again to Meir. Recalling Djehuty’s possible familiarity with the decorative program in tombs there and with their owners’ careers (overlapping in part with his own professional path), one can note that the tomb owners mentioned above (Pepyankh the Middle of Meir D2, Pepyankh the Black of Meir A2, and Ukhhotep son of Senbi of Meir B2) all bear along with the title of lector-priest, as was discussed above, the additional title of sem-priest, while Pepyankh the Middle bears also the title of the Overseer of the Scribes of the King’s Documents (Blackman 1924, p. 2; 1915, p. 2; Blackman and Apted 1953, p. 16). May we regard these men as Djehuty’s source of inspiration for cryptographic information incorporated in the Chapel?