Abstract

Although situated at the geographic margin of the early modern Atlantic World, the Pacific coast of Peru was an important region in the development of African diasporic material culture. Adopting an interdisciplinary material historical approach, we present the first systematic discussion of the known Afro-Atlantic-style tobacco pipes to be archaeologically recovered in Peru. Eighteen Afro-Atlantic-style tobacco pipes or pipe sherds dating to Peru’s Spanish colonial period have been identified across sites in the coastal cities of Lima and Trujillo and from a vineyard hacienda in rural Nasca. Tobacco pipes are among the most recognized and debated forms of early modern Atlantic African and diasporic expressions of material culture, as such, they present a powerful entry point to understanding the aesthetic consequences of colonial projects and diverse articulations across the Atlantic World. The material history of Afro-Atlantic smoking culture exemplifies how aesthetics moved between localities and developed diasporic entanglements. In addition to the formal analysis and visual description of the pipes, we examine historical documentation and the work of nineteenth-century Afro-Peruvian watercolorist Francisco (Pancho) Fierro to better understand the aesthetics of Afro-Andean smoking culture in Spanish colonial and early Republican Peru.

1. Introduction

With its Pacific littoral, the Andean region was situated at the geographic margin of the early modern Atlantic World. Paul Gilroy’s theorization of the Black Atlantic (Gilroy 1993; see also Linebaugh 1982; Thompson 1983) holds that African and African diasporic experiences were crucial to the development of modernity, specifically in the circum-Atlantic. To highlight the unique qualities of the African diaspora in the Andean region, and specifically its coast, Heidi Feldman (2005, 2006) coined the term “Black Pacific” as a diasporic counterpart to Gilroy’s Black Atlantic. She maintains that the region’s present marginal status in African diasporic scholarship mirrors its geographical location at the edge of the Atlantic World, rendering African descendants in the Andean countries of Ecuador, Peru, Chile, and Bolivia largely invisible both at home and internationally. However, a careful examination of African diasporic material culture from Peru’s colonial and early Republican periods allows for a reconsideration of the notion of the Black Pacific as remote and wholly distinct from broader diasporic culture in the early modern Atlantic World.

At the interdisciplinary nexus of art history, archaeology, and social history, “material histories” offer both the tools and perspectives to move beyond the text-centered archives, and to approximate how materials and aesthetic production circulated in the early modern world (Corcoran-Tadd 2022). This tendency of material history has the potential to illuminate questions surrounding how the substantial and significant branch of the African diaspora in the Andes articulates with the broader Atlantic World (Weaver 2022). Such a material and interdisciplinary approach to past culture can center aesthetics, by which we mean the consequences of political and economic processes as actors engage in meaning-making in the world as experienced through the senses (Rancière 1999, 2004, 2010; Weaver 2021).

During the Spanish colonial period, from 1532 to 1821, over 100,000 enslaved Africans were imported to Peru (Aguirre 2000, p. 64). Cities and haciendas along the Pacific coast were the principal destinations for most, although agricultural, mining, and textile production in the highlands also demanded enslaved labor (Bowser 1974; Arrelucea Barrantes and Cosamalón Aguilar 2015). Like many contemporary leading coastal cities in the early modern New World, the viceregal capital, Lima, and the north coastal city of Trujillo were Black metropolises. Enslaved and free Africans and their descendants accompanied the first waves of conquistadores, but were still a small minority when Lima and Trujillo were first settled by Spaniards in 1534. By the turn of the seventeenth century, Lima was a city with a majority Afro-descendant population, including many of mixed ancestry. Figures sent to the Crown by the Archdiocese of Lima in 1636 recorded nearly 54% of the total population of the city as belonging to African-descended “casta” (racio-caste) categories (Bowser 1974, p. 341). In the same period, Trujillo included 32.9% Afro-descendants among free and enslaved residents in 1604, and this demographic had grown to 55.7% by 1784 (Coleman 1976, p. 44, Table II). Nearing the end of the colonial period, the experience of the majority of enslaved Afro-descendants shifted markedly from rural agro-industrial labor on haciendas to urban life. The 1791 census records the total enslaved population in the viceroyalty at just over 40,000 individuals, nearly 74% of which were in Lima (see Flores Galindo 1991, p. 81, Cuadro 1). Only 12% lived and labored outside the cities of Lima, Trujillo, and the highland center of Arequipa.

Notably, by the late eighteenth century, over half of the urban African descendant population were free people. Although the universal abolition of slavery was not gained in Peru until 1854, there were multiple pathways to manumission, including purchasing one’s liberty through participation in the market economy with artisanal production or selling produce from garden plots. Enslaved status followed the matriline, and individuals of mixed European or native Andean ancestry born to enslaved mothers retained enslaved status, while those born to enslaved fathers and free women inherited the liberty of their mothers. In this article, we use the term “Afro-Andean” to encompass the diverse African and African-descended population of Peru’s Black Pacific, not just to signify those of African descent living in the Andes, nor only to imply mixed heritage. An integral facet of the Black Pacific is that Andean and African-descendant worlds cannot be treated as separate spheres, as they often are in Andeanist scholarship.

Adopting a material historical approach, here we present the first systematic discussion of the known Afro-Atlantic-style tobacco pipes to be archaeologically recovered in Peru. Tobacco pipes are among the most recognized and debated forms of early modern Atlantic African and diasporic expressions of material culture, as such, they present a powerful entry point to understanding the aesthetic consequences of colonial projects and diverse articulations across the Atlantic World. Although anchored in decorative motifs originating in West and West Central Africa, African-style tobacco pipes developed unique characteristics in a transatlantic space between the Americas and Atlantic Africa. That is to say, in the Atlantic World, African diasporic cultures emerged in the spaces between continents and political and hegemonic realities—the material history of Afro-Atlantic smoking culture exemplifies how aesthetics moved between localities and developed diasporic entanglements.

Due to historical archaeology’s relatively slow development in Peru in contrast with the subfield’s prominence in North America and the Caribbean, the type and number of historical sites systematically excavated across the Andean nation are limited, and research has rarely focused on the African diaspora (see VanValkenburgh et al. 2016; Weaver et al. 2016). Still, a sample of eighteen Afro-Atlantic-style tobacco pipes or pipe sherds has been identified across urban/suburban sites in Lima and Trujillo and from a vineyard hacienda in rural Nasca (see Figure 1). This assemblage underscores the diasporic connections and interconnections between South America’s Pacific coast and the broader Atlantic World during Peru’s colonial and early republican periods. Specifically, a material history of Afro-Peruvian tobacco pipes and Afro-Andean smoking culture offers a vantage point for understanding the circulation of unique diasporic markers of visual culture and other aspects of sensorial experience. It also brings to the fore the unique contributions of Africans and their descendants to early modern smoking culture in Peru, apart from tobacco smoking’s deep associations with elite Spanish and Creole culture.

Figure 1.

Map of Peru with the locations of Trujillo, Lima, and Nasca indicated. Map by B. Weaver.

2. Afro-Diasporic Materiality and Afro-Atlantic Pipes

A long-held debate in African diaspora studies relates to questions of cultural continuity between descendant groups in the Americas and African societies, leading to a perennial search for “Africanisms”, and those who have emphasized cultural creativity (see Yelvington 2001, pp. 231–32). Afro-Atlantic-style tobacco pipes have been central to this debate in archaeology, especially linking visual similarities in pipe morphology or decorative techniques and motifs across transatlantic space or emphasizing how such traditions have “hybridized” with European or indigenous American cultural expressions. The discontents of the search for so-called Africanisms have largely contested the uncritical way in which specific cultural traits in diasporic material culture have been linked to certain African cultural groups, regardless of demonstrable historical evidence for a connection (see DeCorse 1999).

At present, most scholars of African diasporic materiality acknowledge that both cultural creativity and continuity were at play in the production of the diversity of material expressions across diasporic space. Archaeologists of the African diaspora in Latin America Sampeck and Ferreira (2020) put forward that there is no creativity without memory, and memory is equal to materiality. Indeed, enslaved Africans managed to produce new objects from their collective memory, making use of diverse materials found in the Americas, and creatively borrowed and exchanged aesthetic expressions with other cultural groups. While we refrain from resorting to hybridization theory as a general model of cultural engagement (see Silliman 2015), we recognize the creative aesthetic exchange of actors of African descent, who strategically integrated signs from across sub-Saharan Africa, as well as from Europe and America, in the use, modification, and production of material culture.

By the late sixteenth century, tobacco from the Americas had been introduced to West and West Central Africa through European traders and slavers (see Duvall 2017). Complex smoking rituals developed alongside the diversity of indigenous religious practices and customs (Lemire 2021). Early African smoking equipment began to develop unique properties from its European and indigenous American counterparts, borrowing motifs from the visual culture of ritual pottery and other portable ritual material culture (Ozanne 1964). At the same time, African descendants throughout the European colonial Americas influenced, borrowed, and innovated in the production of smoking pipes. Together, smoking cultures from across the Atlantic World influenced the production of a broad category of smoking equipment we term “Afro-Atlantic”. This includes pipes produced during the pre-colonial Atlantic period of West and West Central Africa, as well as at the fringes of the Atlantic World on Peru’s Black Pacific coast. While it is important to maintain and understand distinctions in the various contexts where smoking pipes were produced in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as the local distinctions in various regions of the Americas, such portable material culture and the technology for its manufacture traveled far and quickly. We cannot understand local African or diasporic smoking cultures without taking into account the entangled political and economic machinery that generated its diverse materialities.

Some Afro-Atlantic pipes originating in sub-Saharan Africa made their way to the Americas through networks of exchange or were smuggled on the bodies of trafficked human beings. For example, at the cemetery of the enslaved of Newton Plantation in Barbados, an individual was buried with a West African pipe, attributed by archaeologists Handler and Norman (2007) as originating from along the Gold Coast (Ghana). Enslaved Africans trafficked across the Atlantic occasionally brought some small personal objects with them, such as beads, cowries, or pipes with short shanks. As Handler (2006) and Handler and Norman (2007) point out, the African pipe could have been smuggled by its owner, or, in an atypical circumstance, various participants in the slave trade approved of the individual keeping such an object. It is also possible that the individual acquired the pipe from Western or enslaved or free African intermediaries traveling between Atlantic Africa and the Caribbean.

Most instances of Afro-Atlantic pipes registered in the Americas, however, did not originate in Africa. They were manufactured across various regions on the two American continents, and most were modeled with short shanks, also called socket-stem pipes. A hollow reed, or stem, is inserted into the end of the shank to facilitate the transfer and inhalation of smoke. The stem could be replaced when necessary, and prevented injuries to the hands caused by the burning tobacco. Unlike European kaolin pipes, Afro-Atlantic-style pipes generally have a thick paste that makes them durable for use while the smoker is working (Schávelzon 2003). These pipes were typically fired in a reducing atmosphere, producing a blackish or gray tone, although there is evidence of pieces produced in an open kiln with orangish-fired paste.

Across Latin America, particularly in the Spanish Caribbean (Ortíz 1940, p. 299) and the Río de la Plata region (Schávelzon 2003, pp. 88, 146–47), historical documentation refers to this style of pipes as “cachimba” or “pito” (whistle). The dimensions and morphology of these pipes are diverse. In the Chesapeake Bay region, most pipes were molded rather than modeled, but these constitute a spectrum from closely resembling African forms to matching the proportions of European styles, and many bear indigenous elements (Agbe-Davies 2015; Emerson 1988, 1994, 1999). In Ceruti and Richard (2023) studied a collection of Afro-Argentine pipes excavated at the seventeenth-century site of Santa Fe La Vieja and categorized the pipes by the arrangement of the bowl’s tobacco chamber in relation to other parts. They arrived at four general types: tubular, angular, “monitor”, and “tipo hornillo”.

These morphologies are almost always accompanied by creative ornamentation, typically presenting techniques such as engravings, linear or geometric incisions, or rouletted impressions. These form triangles, stars, zig-zag patterns, dotted registers, and grooves. Camilla Agostini (2009) and Marcos Souza and Agostini (2012, p. 118) identified some incised repeating patterns on Afro-Brazilian tobacco pipes as similar to sub-Saharan facial and body scarification practices. Others have recognized pipe motifs as representations of cosmograms (Cornero and Ceruti 2012, p. 69, Figure 1; Souza and Lima 2022, p. 13, Figure 15; Patiño and Hernández 2017, p. 235, Figure 5). A few examples are sculptural, with anthropomorphic or zoomorphic representations. These decorations occur on the lip of the bowl or in the distal, mesial, or basal parts of the bowl. In many instances, the shank is also decorated. Afro-Atlantic-style pipes without decoration are rarely recorded.

Because of this diversity of morphology and decoration, the analysis of Afro-Atlantic pipes has focused most heavily on their role in diasporic visual culture, often ignoring other sensory aspects. Of course, these visual aspects are important aspects of smoking aesthetics. Pipe smoking indicates certain aspects of a smoker’s identity, such as status and standing within a community, including visible and tangible links to a diversly understood diaspora. Pipe decorations likely served as multivalent signs communicating diversely to different spectators. However, the other qualities of a pipe, its heft in a smoker’s hand, for example, make up an important aspect of the sensorial experience. Smoke can be seen and smelled, and is the vehicle for nicotine’s stimulating effects, offering temporary respite from the hardships of enslaved life.

In a very specific example of transatlantic movement, Norman (2015) has made use of Robert Farris Thompson’s (1973) “aesthetic of the cool” to discuss the use of the tobacco pipe by Cudjo Lewis (born Oluale Kossola, ca. 1841–1935), a former enslaved man of royal Dahomeyan origin who helped found Africa Town, Alabama. In the Dahomeyan tradition, pipes are closely related to accessing the “coolness” in spirituality (Norman 2015), relating to a metaphor of moral aesthetic accomplishment for having control, individual composure, and social stability, and is related to purity, transcendental balance, and power (Thompson 1973, p. 41). Norman suggests that, in a diasporan context, smoking indicates one’s status and references one’s own personal power and importance in maintaining social stability and the dignity of one’s personal composure. In this sense, the smoker could transcend the status of “slave”. In Dahomey, the pipe was an extension of the elements of coolness, and specifically related to the deification of the royal family. Men were served their pipes by their wives; the old smoked while the young waited (Norman 2015). Of course, from a diasporan perspective, smoking culture transcended the boundaries of gender and age, and important enslaved women and men have been found buried with elaborate slave-made or modified pipes.

3. Afro-Peruvian Tobacco Pipes

In this section, we offer an analysis and description of all eighteen archaeologically recovered Peruvian Afro-Atlantic tobacco smoking pipes (represented by complete artifacts and diagnostic fragments). These pipes were recorded in different types of archaeological interventions in the cities of Lima, Trujillo, and the Jesuit haciendas of Nasca. Most of the pipes found in Lima, and the specimen from Trujillo, were recovered in archaeological interventions that were not academic research projects but rather archaeological supervision for broader architectural preservation programs at historic sites. We offer a visual analysis of each pipe, not to reduce their forms and motifs as retained sub-Saharan cultural practices but rather to demonstrate the range of variation. This diversity in the Peruvian sample bears similarities to styles in the broader Black Atlantic, underscoring the emergence of this type of material culture as a globalized commodity linking communities of smokers across transatlantic spaces.

3.1. Lima

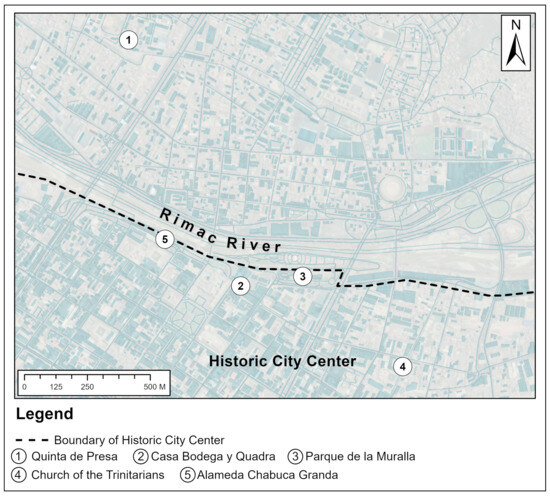

In the Peruvian capital, a total of eleven Afro-Atlantic pipes have been recorded among three viceregal properties where historical archaeological excavations were carried out (see Figure 2). These individual specimens include both fragments and complete pipes and come from properties in and around the historic city center. As noted above, Lima was a city with a majority Afro-descendant population from the beginning of the seventeenth century until Peruvian independence (Tardieu 2003; Jouve Martín 2008).

Figure 2.

Map of present-day Lima with the locations of the sites yielding Afro-Atlantic pipes. Map by B. Weaver.

3.1.1. Quinta de Presa

The first known group of Afro-Atlantic pipes recovered archaeologically in Lima were found during excavations that began in 1976 as part of conservation efforts at the Quinta de Presa site led by García Soto and Zavallos Zavallos (1981). Constructed in the rococo style in the 1760s, the Quinta del Marques de Prensa was the suburban home of Pedro Carrillo de Albornoz, a younger son of Diego Miguel Carrillo de Albornoz y de la Presa, the IV Count of Montemar. On the outskirts of colonial Lima, beyond the city’s wall and located on the opposite side of the Rímac River, the rural property was inherited by Carrillo from his aunt Isabel de la Presa Carrillo de Albornoz, the house’s namesake. In addition to the residence, the property includes a mill, outbuildings, a courtyard, and extensive gardens.

The archaeological project identified the remains of an earlier seventeenth-century house approximately 90 cm below the surface, associated with Lima’s Spanish-Creole aristocracy. Six pipe bowl elements were from this pre-Quinta context, in an area adjacent to the patio accessing the eighteenth-century house and on the side opposite the mill complex. Finding large amounts of carbon, copper ore, and pieces of bronze hardware, García and Zavallos concluded that they were excavating a forge for the production of bronze and/or copper objects (García Soto and Zavallos Zavallos 1981, p. 285). It is possible, then, that these pipes were associated with enslaved or free African-descended metalsmiths.

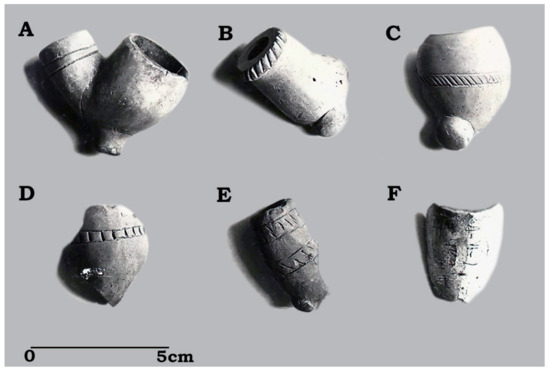

In a macroscopic analysis of the artifacts from Quinta de Presa based on a photograph supplied to us by Gárcia, five are diagnostic pipe stummel fragments and one is a complete element (see Figure 3). The complete pipe stummel is about 5 cm long; it has a short shank and a convex bowl with a height of 3 cm. Likewise, it exhibits a decoration based on two incised lines around the shank, very close to the ferrule, the area where the reed stem would be inserted (Figure 3A). All of these pipes feature or suggest a prominent heel at the base of the bowl.

Figure 3.

Afro-Atlantic-style pipes recovered from Quinta de Presa. (A) complete pipe, (B) pipe shank fragment, and (C–F) pipe bowl fragments. Edited from a photograph courtesy of Rubén Garcia Soto. Layout by J. Solano.

The second pipe fragment (Figure 3B) is decorated with short diagonal lines forming a series of rhombi offset by about 70° in an annular band. The third pipe fragment (Figure 3C) features a similar annular band but around the central part of the bowl, and the diagonal hashes are incised in the opposite direction. Similarly, the fourth pipe fragment (Figure 3D) features a mesial incised band around the bowl, but the hashes are vertical and more distant from one another. In contrast to these patterns of singular annular bands with all of the hashes at the same angle, the fifth fragment (Figure 3E) features two annular bands covering the distal and mesial parts of the bowl and contain zigzag triangle-like designs. Unfortunately, the quality of the photograph does not allow for a complete description of the decorative motif of the sixth fragment (Figure 3F), but the bowl may feature a punctated design.

An Argentine Afro-Atlantic pipe recovered in Alta Gracia (Córdoba) and described by archaeologist Daniel Schávelzon (2003, p. 246, Figure 2) bears a number of similarities to the Quinta de Presa pipes. Dating to around 1810, the Argentine pipe presents incised lines around its shank, as well as annular incised bands on the distal and mesial parts of the bowl, containing diagonal hashes and others that form a reticulate. Like the Quinta de Presa pipes, the Argentine pipe also has a heel, typical of kaolin European-style pipes.

3.1.2. Casa Bodega y Quadra

Complementing the Quinta de Presa pipes are four complete non-European style pipes, one glazed and three unglazed, recovered from archaeological excavations carried out at the Casa Bodega y Quadra in Lima’s historic city center (see Figure 4). These pipes contrast with two European-style heeled kaolin pipes recovered from the same site. In 2004 and 2005, an urban renewal program carried out by the Metropolitan Municipality of Lima in the second block of Jirón Ancash, formerly the Calle del Rastro de San Francisco, in Lima’s historic city center, allowed for the conservation and restoration of several large colonial and early republican homes built on the Rímac river’s ravine. These properties included the Casa de las Trece Puertas, Casa del Balcón Ecléctico, Casa Mendoza, Casa del Rastro, and Casa Bodega y Quadra. During these interventions, the latter property presented abundant evidence of archaeological material, leading to the development of two archaeological projects at the Casa Bodega y Quadra. The first was directed by Daniel Guerrero in 2005, and the second by Fhon in 2010 (Fhon Bazán 2016, p. 147). The property became an archaeological site museum in 2012.

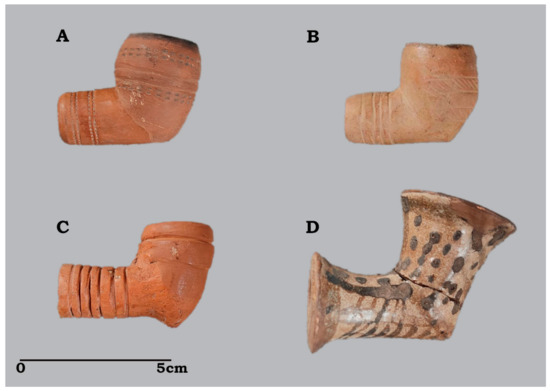

Figure 4.

Pipes recovered from Casa Bodega y Quadra. (A,B) Afro-Atlantic-style pipes with short shank, (C) Afro-Atlantic-style pipe with slightly longer shank, and (D) tin-enameled short-shank pipe. Photographs by M. Fhon. Layout by J. Solano.

Excavation at Bodega y Quadra revealed evidence of the Rastro de San Francisco butchery and slaughterhouse, established by the city in 1552. An enslaved Black butcher named Antón was purchased by the city, but because his management of the butcher shop was indispensable, he was manumitted as a condition of his public employment (Cabildos de Lima [1552] 1935, p. 548). By the end of the seventeenth century, the elite domestic construction within the block extended throughout the lots, building over the butchery (Fhon Bazán 2010). By this time, domestic service by enslaved people had greatly expanded across the city, employing enslaved labor in elite homes, monasteries, and hospitals. For the first time, the urban demand for enslaved labor entered competition with the haciendas of the viceroyalty. In the eighteenth century, the Bodega y Quadra family held a number of enslaved persons devoted to domestic service (Morales Cama and Herrera 2009).

At the Bodega y Quadra home, enslaved women were charged with cooking, child care, laundry, and maintaining the household. Enslaved men would have driven the carriages and assisted Tomás de la Bodega y Quadra with his trade as a merchant. As revealed through documentation of urban households across the viceroyalty, urban elites also often held enslaved tradesmen at their homes. Evidence of small-scale pottery production in the form of pottery wheels, kiln furniture, and ceramic wasters at the Casa Bodega y Quadra suggests that the enslaved tradesmen employed by the family may have included at least one potter.

The three complete ceramic pipe bowls that resonate with Afro-Atlantic aesthetics were recovered from contexts across the site. The pipes vary in the length of their shanks but are otherwise typical of standardized dimensions for this class of material culture. They also show signs of use due to the evidence of burning in the bowl.

The first specimen (BQ 177; Figure 4A) presents a combination of decorative techniques: four fine denticulated lines, called incised roulettes (Monroe 2002, p. 3), create a sequence of incisions around the pipe’s shank. This same technique is replicated in the distal and mesial parts of the bowl, associated with two incised angular lines. The use of similar decorative techniques and motifs are also recorded on African American pipes in the Chesapeake region of colonial Virginia (Agbe-Davies 2015, p. 38, Figure 2.1).

The second pipe stummel (BQ 180; Figure 4B) shows four shallow incised lines around the shank. Likewise, the mesial and distal areas of the frontal sector of the bowl are decorated with two horizontal bands with diagonal hashes. The third element (BQ 178; Figure 4C) is distinct from the first two, with its slightly longer shank ringed with six deep incised lines. In addition, it has two incised lines that surround the distal and mesial areas of the bowl, and rather than the fully-formed heel characteristic of the Quinta de Presa pipes, the specimen features a protuberance at the base. African-made pipes from the Ghana region (Ozone 1962 in Souza and Lima 2022, p. 9, Figure 9) present similar annular motifs to those recorded in Casa Bodega y Cuadra.

Another pipe (BQ 179; Figure 4D) is glazed in tin enamel and bears a polychrome motif typical of baroque majolica wares. This suggests local manufacture in the city, perhaps by a ceramicist engaged in the production of tableware. Both the shank and the bowl are flanged, and the motif features irregular dark brownish-black spots arranged on a cream background in files running from the bowl’s rim to the ferrule at the shank’s edge. The inferior area from the heel to the ferrule is decorated with curved linear hash marks. All four of these pipes contrast with two mostly complete European-style kaolin pipes also recovered at Bodega y Quadra. The latter were deeply associated with Spanish and Creole elite smoking culture in the viceroyalty. Although we do not assume a strict division of smoking equipment between African-descended and non-African-descended smokers, three of these pipes resonate with Afro-Atlantic pipes from elsewhere in the Atlantic World. In contrast, the majolica glazed pipe appears to be an Afro-Andean innovation.

3.1.3. Parque de La Muralla

In 2004, after excavations along the left bank of the Rímac between Abancay and Lampa avenues adjacent to the San Fransico convent revealed seventeenth-century domestic architecture and a segment of colonial Lima’s northern perimeter wall, SERPAR (Servicio de Parques de Lima) opened the Parque de La Muralla as a public park. Among the artifacts displayed at the park’s small interpretive center and site museum are two Afro-Atlantic-style tobacco pipes recovered from excavations of the elite residences. Much like at the nearby Casa Bodega y Quadra, enslaved African-descended domestics would have served these homes, and it is not surprising to find materials associated with the urban Black population.

Both pipe stummels feature annular incised and rouletted patterns. The first (see Figure 5A) bears three rouletted bands along the shank. Each of the bands is made up of two tight parallel rows of small rectilinear impressions. The bowl is decorated with six parallel deep incised annular bands. Only the left side of the bowl remains, adorned with a modeled and applied seal or emblem atop these incisions. The second pipe (Figure 5B) from this site has a slightly more prominent heel. Like the first pipe, this stummel bears three annular bands around the shank. The first is a deep incision; the other two consist of stamped roulette rhomboids. The incised parallel lines around the lateral and anterior areas of the bowl are discontinuous except for the central line around the medial register. The lines terminate in a stamped triangle, suggesting that the stylus used to inscribe the bowl was triangularly tipped.

Figure 5.

Lateral views of Afro-Atlantic-style pipes recovered from Parque de La Muralla (A,B). Photographs by Diana Allccarima Cristómo. Layout by J. Solano.

3.1.4. Barrios Altos

Excavators from the Municipal Program for the Recuperation of the Historic Center of Lima, or ProLima (Programa Municipal Para la Recuperación del Centro Histórico de Lima) have recovered at least three Afro-Atlantic-style pipes in recent excavations associated with conservation work in Lima’s downtown. ProLima was initiated in the years leading up to the 2021 bicentennial anniversary of the Republic. Two pipe examples were recovered in the Barrios Altos neighborhood. The first was encountered during a project focused on excavating the city’s early canals (El Pregonero 2024, p. 9). It is elaborated with diagonal hashes around a raised ferrule ring and a series of parallel incised lines on the anterior lower and mid-section of the bowl above its modest heel (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Anterior and lateral views of Afro-Atlantic-style pipe recovered from Barrios Altos. Photograph courtesy of ProLima. Layout by J. Solano.

The second pipe was recovered from excavations at the Church of the Trinitarians (Order of the Most Holy Trinity and of the Captives). This artifact came to our attention in a photograph posted to Instagram by ProLima (ProLima (@prolima_chl) 2024), and we contacted the archaeological team for more details (see Figure 7). The pipe is a complete stummel, similar in form to Bodega y Quadra specimen BQ 178 (Figure 4C), with a pointed heel or spur. The shank features several deep annular bands, as does the upper and central areas of the bowl. The interior is also burned from use.

Figure 7.

Anterior and lateral views of Afro-Atlantic-style pipe recovered from Church of the Trinitarians. Photograph courtesy of ProLima. Layout by J. Solano.

3.1.5. Alameda Chabuca Granda

Recent excavations by Prolima revealed another Afro-Atlantic-style pipe at the Alameda Chabuca Granda. Behind Lima’s Government Palace, this promenade along the left bank of the Rímac River was named in honor of the criolla singer-songwriter María Isabel (Chabuca) Granda Larco, who appropriated Afro-Peruvian music. The site was formerly a public market and, until the 1950s, the location of the Casa Concha, a mansion built in the style of a neoclassical Venetian palace. Before the construction of the Casa Concha by the noble Vega del Ren family in the nineteenth century, several colonial elite households occupied the area, and the tobacco pipe dates to this period.

The tobacco pipe stummel recovered at this site features a robust and prominent heel (see Figure 8). The ferrule is raised near the mortise and bears an annular incised pattern of diagonal marks, likely produced from fingernail impressions. Similarly, the central anterior area of the bowl displays an incised band made from two thin parallel lines hatched with short diagonal markings. ProLima may yet have recovered other examples, but as laboratory analysis is ongoing for their diverse projects across the historic city center, very few details of their findings over the past few years have yet been made public.

Figure 8.

Lateral views of Afro-Atlantic-style pipe recovered from Alameda Chabuca Granda. Photograph courtesy of ProLima. Layout by J. Solano.

3.2. Trujillo

A single Afro-Atlantic-style pipe (Figure 9) has thus far been identified in the City of Trujillo, on Peru’s north coast. The pipe was recorded during excavations for a civil project in the historic city center within the framework of an archaeological monitoring plan (Monzón 2019). The excavations took place along a pedestrian sidewalk of Jirón San Martín, block five (adjacent to the Corcuera Notary Office). The stratum associated with the pipe contained other material culture from the colonial and republican periods.

Figure 9.

Lateral and posterior views of Afro-Atlantic-style pipe recovered in Trujillo. Photograph and layout by J. Solano.

The artifact was studied by Solano and colleagues (2022) and identified as a short shank, composite pipe fired in an open kiln. Its ornamentation consists of shallow, thick incised lines, forming a zigzag pattern around the bowl. The back of the bowl features punctations filling one of the large triangles made by the zigzag incisions. This type of decoration resonates with widespread motifs across West Africa. The bowl’s interior also exhibits evidence of burning (Solano et al. 2022). Particular to this specimen are the small, scattered traces of enamel across its surface, which suggest that it was originally covered in a tin-enameled glaze, like the pipe recorded at Casa Bodega y Cuadra in Lima (BQ 179; Figure 4D). As far as we know, these are the only two enameled Afro-Atlantic-style pipes reported thus far in Peru.

The Trujillo pipe is similar to those manufactured and distributed in Virginia, especially those with motifs of facing incised triangles (Monroe 2002, p. 49, Figures 389, 396, 397, 400). However, the techniques of decoration differ. Still, this type of zigzag decoration encircling the pipe bowl has been found among Afro-Atlantic pipes in Brazil (Souza and Lima 2022, p. 8, Figure 7FM, 7V), although the incisions are smaller and repeat over the pipe bowl’s surface.

3.3. Nasca

In 2009, in south coastal Peru, the Haciendas of Nasca Archaeological Project, directed by Weaver, became the first archaeological project explicitly focused on the African diaspora in the country. The project investigates the diversity of the daily lived experiences of enslaved Afro-Andean laborers at two large vineyard hacienda systems owned by the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) between 1619 and 1767, as well as the post-Jesuit material histories of the estates. At the end of the Jesuit period, these were the largest and most valuable vineyards in the viceroyalty, producing high-quality wines and grape brandy (“aguardiente de la uva”, today called “pisco”) and enslaving nearly 600 individuals. During excavations in 2013, two Afro-Atlantic-style tobacco pipe bowl fragments were recovered from refuse middens associated with enslaved residents at the core of the former hacienda San Joseph de la Nasca (present-day San José) (Weaver 2015).

The first fragment (Figure 10A) was recovered from Locus 1299, Unit 8. The ceramic pipe bowl sherd exhibits an annular band of stamped or incised facing triangular designs delineated by fine incised lines. At its thickest, the pipe bowl fragment measures 5.8 mm, making it a very fine and high-quality example of what is a common motif across the Americas (Cornero and Ceruti 2012, p. 74, Figure 6; La Rosa n.d., p. 11, Figure 5B; Letieri et al. 2009, p. 62; among others) and Atlantic Africa (Clist 2018, p. 299, Figure 21.5; Clist et al. 2018, p. 244, Figure 19.3–4).

Figure 10.

Afro-Atlantic-style pipes recovered at the site of the Hacienda San Joseph de la Nasca (A,B). Photographs by B. Weaver. Layout by J. Solano.

The pipe with an incised triangular motif bears a strong resemblance to the seventeenth-century pipe recovered at Quinta de Presa in Lima (García Soto and Zavallos Zavallos 1981, Figure 19). The motif also appears on pipes recovered in excavations from the Kingdom of Dahomey in Benin (Norman 2008, p. 338), Notsé in Togo (Aguigah 1986, p. 353), the seventeenth-century maroon community at Palmares in Brazil (Orser 1996, p. 126), and maroon sites of Santo Domingo (in the Dominican Republic) and Cuba (Arrom and García Arévalo 1986, pp. 50, 64, 65).

The second pipe bowl fragment (Figure 10B) recovered at San Joseph de la Nasca is also very thin and fine, and came from Locus 1395, Unit 9. The sherd includes part of the bowl’s rim and bears a series of parallel incised bands that would have extended around the bowl. It resembles decorative motifs typical of Afro-Atlantic-style pipes from Argentina (Gancedo 1973, p. 74, Plate III—1840), as well as those produced in the South and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States (Monroe 2002, p. 52, Figure 424). All of these also possess a certain correlation with African pipes (Clist 2018, p. 327, Figures 21, 31–24). While the Nasca pipes share stylistic similarities with those from other regions of the diaspora as well as Atlantic Africa, they break with the dominant pattern of pipes with thick paste. It is clear that the potters who made the Nasca pipes were highly skilled due to the quality of the paste used in their elaboration; these artisans were perhaps even the skilled amphora jar potters (“botijeros”) enslaved at San Joseph.

4. Toward a Material History of Afro-Andean Smoking Culture

The above descriptions primarily contribute to an understanding of Peruvian Afro-Atlantic tobacco smoking pipes as visual culture; we recognize that is but one aspect of their social and aesthetic value. It is our intent to launch the beginnings of a material history of such portable material culture that seeks to understand these artifacts’ place, not solely as representatives of Afro-Peruvian visual vocabulary nor to reduce them to mere smoking equipment but rather to contextualize their place in what was surely a diversity of Afro-Andean experiences in the colonial and early Republican periods. While there are relatively limited Peruvian primary sources that might offer insight into the role of smoking in everyday life among African descendants, we start by drawing some clues from Afro-Peruvian visual culture, specifically in the watercolors of Francisco (Pancho) Fierro Palas (1810–1879).

4.1. The Nineteenth-Century Watercolors of Pancho Fierro

Few portraits of Afro-Andean subjects engaged in everyday activities exist from the Spanish colonial period (see Walker 2017). However, in the early Republican Period, Afro-descended visual artist Pancho Fierro produced a body of watercolors that paid careful attention to a diversity of urban and rural personae, including Afro-Andeans (Barrón 2018). Although Fierro did not date his own work (Palma 1935, p. xv), the dates assigned to the bulk of his images range from 1830 to 1850. This is significant because he captures life in coastal Peru after Peruvian independence in 1821 but before emancipation in 1854. The association of Afro-Andean identity with pipe smoking can be seen in his work. Fierro often produced multiple iterations of the same prototypical subject in different poses or with slightly different clothing or accessories. Smoking equipment is precisely the type of detail that varies between these distinct versions. Fierro paints figures from a diversity of backgrounds, smoking rolled tobacco or cigars, but he restricts pipe smoking almost exclusively to his Afro-Andean male and female subjects.

Several of Fierro’s watercolors in the Hispanic Society Museum collection depict figures smoking cigars, including Black Bullfighter on Horseback, Peru (Fierro Palas ca. 1840a), Creole [Peruvian-born White man] on Horseback, Lima (Fierro Palas ca. 1840b) and Woman Smoking in a Yellow Shawl, Lima (Fierro Palas 1830–1860b). The bullfighter is identified by handwriting under the figure as “Capeador Arredonado”, Esteban Arredonado, one of the most popular bullfighters in nineteenth-century Lima (Porras Barrenechea and Bayly 1959, p. 67; see also Barrón 2018, p. 74). The woman with the yellow shawl appears also to be of African descent.

Likewise, Yale University Art Gallery holds a watercolor attributed to Fierro that has been given the title Indian Woman Smoking Cigar in Front of Breadstand (Fierro Palas ca. 1850a; Figure 11). Given the attention to his subjects’ skin tones and facial characteristics, it is likely Fierro’s intent was not to portray a native Andean woman but a woman of both African and Indigenous ancestry (“casta zamba”). Curators and collectors unfamiliar with the rich diversity of identities in nineteenth-century coastal Peru were likely to mislabel Fierro’s subjects. Another watercolor in the same collection, attributed to Fierro, Piquanteria [sic. Picantería] (Fierro Palas ca. 1850c), depicts a server and patrons eating lunch at a traditional restaurant. A light-skinned and light-haired woman shrouded by a mantel sits adjacent to a row of wine jars (“botijas”) and smokes a thin cigar.

Figure 11.

(Left): Detail of Fierro Palas, Francisco (attributed), ca. 1850. Indian Woman Smoking Cigar in Front of Breadstand, watercolor on paper, H 19.7 × 24.6 cm. Accession Number: 1967.36.20. Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven. Photograph in public domain. (Right): Detail of Fierro Palas, Francisco (attributed), ca. 1850. Woman with Basket on her Head, watercolor on paper, H 22.5 × 17.1 cm. Accession Number: 1967.36.32. Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven. Photograph in public domain.

The Yale Gallery also holds several watercolors attributed to Fierro that depict Afro-descended figures smoking tobacco pipes. Among the most illustrative scenes of daily life in Lima, Interior of an Inn (Fierro Palas ca. 1850b), depicts a majority African-descended crowd engaged in an “ágape”, in which guests support the family of a recently buried loved one with food and financial donations (Figure 12). They are gathered in the open-air courtyard inside the hall of a Black confraternity rather than an inn (Sánchez 2021, p. 78). The space is marked as such, with a devotional painting of the Virgin and given the Afro-Peruvian subjects in the paintings depicting heroes of Peruvian independence. Dressed in black and with his face covered, the head of the family sits at the table at the center of the scene, receiving the support of the guests. As is the tradition to date in rural Afro-descended coastal communities, the deceased’s grieving wife sits on the floor next to the table. To the left of the image, at the feet of a seated elderly couple, are African-style drums, “güiros”, and a thumb piano. At the right margin are a pair of women covered in black mantles bearing West African facial scarification. A woman conversing with a group of mourners with black headscarves to the right of the table smokes a pipe. The other pipe smoker in the scene is an elegantly dressed man in purple pantaloons and poncho, a narrow-brimmed hat, and carrying a “bastón” (a cane associated with office or high status).

Figure 12.

Upper register: Fierro Palas, Francisco (attributed), ca. 1850. Interior of an Inn, watercolor on paper, H 44.7 × 58.8 cm. Accession Number: 1967.36.40. Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven. Photograph in public domain. Lower register: details of Interior of an Inn featuring an Afro-Peruvian man (left) and woman (right) smoking tobacco pipes.

Interior of an Inn offers context for the type of persons who might smoke pipes and in which particular social settings. An “ágape”, where comforting food, drink, and music are shared, is seemingly an appropriate occasion for smoking a tobacco pipe. Dressed in their finest clothing for mourning, the smokers signal their relatively high status within their community.

As he did with smokers of cigars, Fierro also produced individual portraits of persons smoking pipes apart from scenes like Interior of an Inn. He produced a series of portraits of a chandler selling candles in the street, and variations depict the man with (e.g., Vendedor de Velas, (Fierro Palas ca. 1850–1860) or without a pipe (e.g., Tallow chandler, Peru, Fierro Palas 1830–1860a). Woman with Basket on her Head (Fierro Palas ca. 1850d; Figure 11) at the Yale Gallery features an archetypical subject for Fierro, who appears in several variations (e.g., Fierro Palas 1830–1860a). The woman, a dark-skinned Afro-Peruvian, is depicted balancing a basket and smoking a pipe.

Figures like candle sellers or the women carrying baskets are engaged in labor in public settings and may even be the owners of their own enterprises. In most of his depictions of cigars and tobacco pipes, a cloud of smoke emanates from the smoking equipment. While the cigars are often signaled with an expedient line, care is given to the image of the pipe, including alluding to its multisensorial properties carried in the tobacco smoke. Fierro’s work is illustrative of the various types of individuals who may have been found smoking either cigars or tobacco pipes in early Republican Peru. It is clear that Fierro was aware of the unspoken rules that governed Afro-Peruvian smoking culture and, through his own visual language, indexed its multisensorial aesthetics.

4.2. A Paucity of Pipes? Contextualizing Smoking Culture

Peru’s Pacific coastline stretches for over 3000 km. It is surprising that in that totality of space, and after nearly fifty years of various historical archaeological projects, there are so few known examples of Afro-Atlantic-style tobacco pipes. What might the known specimens signify about how they were used and by whom?

This question relies on knowing more about the frequency and distribution of such pipes in the past. As referenced above, while archaeological projects, especially those associated with architectural historic preservation projects, have become more commonplace in Peru since the 1970s, they are still vastly outnumbered by archaeologies of the periods prior to the arrival of the Spaniards in 1532. Due to ideal environments for multimillennial archaeological preservation and foreign fascination with ancient Peruvian cultures, Peru derives nearly 7% of its GDP from foreign and national tourism, much of which is associated with visits to archaeological sites. Ancient Peruvian archaeology looms large in the country, and few national archaeologists have formal training in historical archaeology or experience with colonial and early Republican material culture.

This results in two consequences for historical archaeology. First, there are relatively few historical archaeological projects where the sole principal investigator is Peruvian, and therefore there are relatively few historical archaeological projects operating in the country. Second, because many contract archaeologists lack familiarity with historical archaeology, technical reports for supervision or conservation projects tend to be light on description and omit details for the material culture dating post-1532. That is to say that not enough sites have yet been systematically excavated by archaeologists trained in working with material culture dating to the colonial and early Republican periods. Additionally, there may be other pipes in the repositories of the Peruvian Ministry of Culture that were not adequately identified or described in official technical reports and, therefore, go unknown to the greater archaeological community.

In the context of specific archaeological sites, or rather a collection of archaeological sites, such as the Jesuit vineyard haciendas of Nasca, we find some evidence that tobacco pipes might have been restricted among certain enslaved persons. Weaver and his team excavated a diversity of contexts at the cores of the principal haciendas of San Francisco Xavier de la Nasca, San Joseph de la Nasca, and San Joseph’s eighteenth-century annex, Hacienda La Ventilla, yet only recovered two Afro-Atlantic pipe sherds. This is curious because historical documents suggest that there were regular disbursements of tobacco to the enslaved population.

Historian Pablo Macera found among a number of instructions from Jesuit provincial superiors to administrators of Jesuit haciendas specific mandates for the distribution of tobacco, often mentioned along with food and clothing (Macera 1966, p. 45). Certain instructions detail that high-quality meat, tobacco, and alcohol (“aguardiente”) were to be given to the enslaved laborers on important feast days (Macera 1966, p. 92). At the Jesuit haciendas of Nasca, receipts from the first decade of the eighteenth century indicate several annual purchases of tobacco for the enslaved population (AGN 1702–1708, f.15r). The inventories produced in 1767 during the Jesuit expulsion and Crown expropriation of Jesuit holdings also list tobacco stores at each estate; some of this product was purchased from tobacco plantations in the Peruvian north coastal town of Zaña (ANC 1767a, f.269r; 1767b, f.242v). It remains unclear from these documents precisely who among the enslaved on these estates received gifts of tobacco, although it was likely given to both men and women of higher status. In his comprehensive study of Jesuit hacienda expenditures, historian Nicolas Cushner also found that tobacco was regularly purchased, but he argues that “the quantities purchased were so small that it was probably only given to a few officials and foremen” (Cushner 1980, p. 199). Whatever the case, the enslaved at haciendas would have smoked tobacco during special occasions and feast days rather than as a habit of everyday life.

In previous publications, Weaver (2015, 2018; Weaver et al. 2019) has argued that the relative paucity of tobacco pipes recovered from middens associated with the enslaved communities suggests that relatively few individuals used such pipes, instead smoking rolled tobacco or cigars. Following Cushner and considering that potentially higher-ranking enslaved individuals such as master craftsmen and “caporales” (foremen) had more regular access to tobacco, the use of a tobacco pipe, specifically an Afro-Atlantic-style pipe, might, therefore, indicate the relatively high status of the smoker.

As described above, the tobacco pipe as a marker of status is also suggested by other archaeologists working elsewhere in the Americas, and the restricted nature of pipe smoking is seen in Fierro’s watercolors. In Lima, the six pipes recovered from the seventeenth-century context at Quinta de Presa were seemingly associated with a bronze or copper forge. Bronzesmiths in West Africa were held in high regard by their societies, and enslavers sought individuals with such skills for work on estates and urban smithing trades in the Americas. The smiths employed at Quinta de Presa would have ranked high among the enslaved labor force, and access to tobacco and associated smoking equipment might even be expected. The concentration of Afro-Atlantic-style pipes near the forge and absent from other excavated contexts at Quinta de Presa, could be explained as a question of social rank and enslaved hierarchy.

Similarly, skilled enslaved individuals and tradespeople in the employ of the Bodega y Quadra family may have had access to privileged goods as well. Urban life was paradoxical in that there was both constant surveillance at elite residences and the possibility to pass into the anonymity of crowds and opportunities to form community beyond the household. During time away from the household, the enslaved partook in the rites and events of confraternities, attended dances in public plazas, and met in public chicha taverns to drink and engage in conversation. Skilled enslaved tradespeople also participated in market life, purchasing and selling goods. Among the goods acquired may have been tobacco and smoking pipes. In Buenos Aires, shops called “pulperias” specifically sold “pitos de negro” (Schávelzon 2003, p. 163). Although such documentation has not yet been discovered for Lima or Trujillo, shops may have similarly been a source for acquiring such pipes. Pipes may have been purchased either by enslaved or free Afro-Andeans, or by estate or household management for distribution to enslaved workers.

The distribution of the known Peruvian Afro-Atlantic pipes suggests that they are not an anomaly, nor were they primarily acquired as contraband, secreted into the region by enslaved people. Estate sites like the haciendas of Nasca and Quinta de Presa suggest that not all African-descended smokers used them and that they were likely a marker of status for enslaved and free persons in both rural and urban Peru. These data do not allow us to conjecture as to the size of the industry in colonial and early Republican Peru responsible for their production, but it is also clear that such production was artisanal. Each pipe was modeled, not molded or mass-produced. The decorative techniques and motifs are variable, suggesting that each pipe was individualized and that there may have been a special indexical relationship between a pipe and its smoker. Pipes may have even been commissioned by their owners. As more systematic historical archaeology is conducted in the country, such as those conservation projects led by ProLima, it is certain that other pipes will be found that may clarify these questions.

5. Final Reflections

Aesthetics are the consequences of political and economic processes as actors engage in meaning-making. The purpose of this article was not to identify specific connections to sub-Saharan traditions but to document the range and aesthetic interventions related to Peruvian Afro-Atlantic pipes and how African descendants in the “Black Pacific” of the Andean region intervened in the aesthetic production through smoking culture. As a type of visual culture and creative expression, the assemblage of Peruvian pipes emerges from a number of African and diasporic traditions and does not represent a unified corpus of production. This pattern resonates with tobacco pipes found elsewhere in the Americas, and indeed African-style pipes in general, which developed unique characteristics in a transatlantic space between the Americas and Atlantic Africa.

With this first systematic discussion of the known Afro-Atlantic-style pipes that have been archaeologically recovered in Peru, we hope to initiate a broader discourse on the phenomenon of Afro-Atlantic pipes. Until now, such discussions have not included material culture from the Black Pacific. The Peruvian Afro-Atlantic pipes emphasize the diasporic entanglements between the Andean region and the broader Atlantic World during Peru’s colonial and early republican periods. Early scholarly discussions about this style of pipes focused on their inherent hybridity or locating Africanisms within their morphology or decoration. Rather, we suggest a material historical and aesthetic approach focusing on understanding the creative and multivalent interventions of pipe producers who developed pipes for specific local cultural contexts while at the same time participating in an economy of signs that circulated from the Pacific edge of the Atlantic World to the interior of Atlantic Africa.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in the conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation and writing of the original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

While the individual research projects that recovered the artifacts discussed in this piece, funding for the collaborative writing of the manuscript was provided by Florida State University, Department of Art History.

Data Availability Statement

All materials recovered from the various excavations discussed in this article are housed at designated repositories overseen by the Peruvian Ministry of Culture. The accompanying documentation for these archaeological projects is also held by the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Peru.

Acknowledgments

We owe a debt of gratitude to many generous individuals and institutions who have made this research possible. Firstly, we thank our colleagues and community partners involved in our own research projects and programs, namely the Proyecto Arqueológico Haciendas de Nasca, Museo del Sitio Bodega y Quadra, and the Proyecto de Investigación de Colecciones de Materiales Arqueológico—Trujillo. Photography of the pipes from the Parque de La Muralla collection was facilitated by Diana Allccarima Cristómo (conservator of cultural materials at the Museo de Sitio Bodega y Quadra) and Carmen Chauca (Director of the Museo de Sitio del Parque de La Muralla [SERPAR]). Thank you to our colleagues at ProLima who provided information and artifact photographs: Ernesto Olazo Rázuri (Operations Manager of the ProLima archaeological team), Cristian Almonacid Paredes (Director of the Proyecto de Investigación de las Portadas, Baluartes y Tajamares de La Muralla de Lima), Diego Pariona Espinoza (Director of the Proyecto de Investigación Canalés de Lima Sector de la Iglesia de las Trinitarias), and José Luis Hermoso Alvarado (field archaeologist of the Proyecto de Investigación Canalés de Lima Sector de la Iglesia de las Trinitarias). Rubén García Soto of the Peruvian Ministry of Culture Ica office provided information and photographs from the Quinta de Presa excavations. Thank you to Nathalie Monzón (Director of the Proyecto de Monitoreo Arqueológico de la Zona Monumental de Trujillo). Special thanks to Juan Castañeda, Vicenta Guerra, Juana Paz, Flavia Zorzi, and Meghan Weaver. We very much appreciate the invitation to participate in this thematic issue from guest editors Paul Niell and Emily Thames, and we are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers who enriched this study with their comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Agbe-Davies, Anna S. 2015. Tobacco, Pipes, and Race in Colonial Virginia: Little Tubes of Mighty Power. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press. [Google Scholar]

- Agostini, Camilla. 2009. Cultura material e a experiencia africana no sudeste oitocentista: Cachimbos de escravos em imagens, historías, estilos e listagens. Topoi 10: 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguigah, Dola A. 1986. Le Site de Notsé: Contribution à l’archéologie du Togo. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, Université du Paris I, Paris, France. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre, Carlos. 2000. La población de origen africano en el Perú: De la esclavitud a la libertad. In Lo Africano en la Cultura Criolla. Edited by Carlos Aguirre. Lima: Fondo Editorial del Congreso de la República, pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Archivo General de la Nación del Perú, Archivo Colonial, Lima, Perú [AGN]. 1702–1708. Cuentas de la Hacienda San José de la Nazca y del oficio del Colegio del Cuzco, Correspondientes a los años 1702 y 1708, C-13, Leg. 128, C.1.

- Archivo Nacional de Chile, Santiago de Chile [ANC]. 1767a. Testimonio de la Hacienda San Joseph de Nasca. Vol. 344 #17. [Google Scholar]

- ANC. 1767b. Verdadero testimonio de la hacienda de viña nombrada San Francisco Xavier de la Nasca, Yca. Vol. 344, #16. [Google Scholar]

- Arrelucea Barrantes, Maribel, and Jesús A. Cosamalón Aguilar. 2015. La Presencia Afrodescendiente en el Perú: Siglos XVI–XX; Lima: Ministerio de Cultura del Perú.

- Arrom, José Juan, and Manuel A. García Arévalo, eds. 1986. Cimarron. Santo Domingo: Fundación García Arévalo. [Google Scholar]

- Barrón, Josefina. 2018. Pancho Fierro: Un Cronista de su Tiempo. MUNILibro15. Lima: Municipalidad de Lima. [Google Scholar]

- Bowser, Frederick P. 1974. The African Slave in Colonial Peru 1524–1650. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cabildos de Lima. 1935. Libros de Cabildos de Lima, Volume 4: Libros de Cabildos de Lima: 1548–1553. Edited by Bertram Tamblyn Lee and Juan Bromley. Lima: Torres Aguirre. First published 1552. [Google Scholar]

- Ceruti, Carlos, and Alejandro Richard. 2023. ¿Quién fumó en estos “cachimbos”? La colección de pipas cerámicas de Santa Fe la vieja (Cayastá, dpto. Garay, prov. de Santa Fe, Argentina). Folia Historica del Nordeste 46: 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clist, Bernard. 2018. Les pipes en terre cuite et en Pierre. In Une Archéologie des Provinces Septentrionales du Royaume Kongo. Edited by Bernard Clist, Pierre de Maret and Koen Bostoen. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 297–327. [Google Scholar]

- Clist, Bernard, Nicolas Nikis, and Pierre de Maret. 2018. Séquence Chrono—Culturelle de la poterie Kongo. In Une Archéologie des Provinces Septentrionales du Royaume Kongo. Edited by Bernard Clist, Pierre de Maret and Koen Bostoen. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 243–79. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, Katherine. 1976. The Decadencia of a Spanish Colonial City: Trujillo, Peru, 1600–1784. Bulletin of the Society for Latin American Studies 25: 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran-Tadd, Noa. 2022. Introduction: Towards a material history of Colonial Latin America. Colonial Latin American Review 31: 573–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornero, Silvia, and Carlos Ceruti. 2012. Registro arqueológico afro-rioplatense en Pájaro Blanco, Alejandra, Santa Fe: Análisis e interpretaciones. Teoría y Práctica de la Arqueología Histórica Latinoamericana 1: 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cushner, Nicholas P. 1980. Lords of the Land: Sugar, Wine, and Jesuit Estates of Costal Peru, 1600–1767. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeCorse, Christopher R. 1999. Oceans apart: Africanist perspectives of diaspora archaeology. In ‘I, too, Am America’: Archaeological Studies of African-American Life. Edited by Theresa A. Singleton. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, pp. 132–55. [Google Scholar]

- Duvall, Chris S. 2017. Cannabis and Tobacco in Precolonial and Colonial Africa. African History. Published Online 31 March 2017. Available online: https://oxfordre.com/africanhistory/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277734-e-44 (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- El Pregonero. 2024. El secreto de la Maravillas: Investigación arqueológica en curso da pistas sobre estructuras subterránea relacionada con los antiguos canales de Lima. No. 46 (June 2024). [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Matthew C. 1988. Decorated Clay Tobacco Pipes from the Chesapeake. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Matthew C. 1994. Decorated Clay Tobacco Pipes from the Chesapeake: An African Connection. In The Historic Chesapeake: Archaeological Contributions. Edited by Barbara J. Little and Paul A. Shackel. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, Matthew C. 1999. African Inspirations in a New World Art and Artifact: Decorated Tobacco Pipes from the Chesapeake. In ‘I, too, Am America’: Archaeological Studies of African-American Life. Edited by Theresa A. Singleton. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, pp. 47–75. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, Heidi Carolyn. 2005. The Black Pacific: Cuban and Brazilian Echoes in the Afro-Peruvian Revival. Ethnomusicology 49: 206–31. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, Heidi Carolyn. 2006. Black Rhythms of Peru: Reviving African Musical Heritage in the Black Pacific. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fhon Bazán, Miguel Á. 2010. Secuencia Constructiva en el área de la casa Bodega y Cuadra del siglo XVI al XVIII. Paper presented at the Simposio Internacional de Arqueología Histórica, Lima, Perú, August 13. [Google Scholar]

- Fhon Bazán, Miguel Á. 2016. Excavaciones arqueológicas en la Casa Bodega y Quadra en el Centro Histórico de Lima. Boletín De Arqueología PUCP 21: 145–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierro Palas, Francisco. 1830–1860a. Tallow Chandler, Peru; Watercolor on Paper, H 30.7 × W 23 cm. Accession Number: A2276. New York: The Hispanic Museum and Library. Available online: https://hispanicsociety.emuseum.com/objects/948/black-laundress-smoking-a-pipe-profile-right-lima (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Fierro Palas, Francisco. 1830–1860b. Woman Smoking in Yellow Shawl, Lima; Watercolor on Paper, H 10.9 × W 16.2 cm (irregular). Accession Number: LA1741. New York: The Hispanic Museum and Library. Available online: https://hispanicsociety.emuseum.com/objects/2580/woman-smoking-in-yellow-shawl-lima (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Fierro Palas, Francisco. ca. 1840a. Black Bullfighter on Horseback, Peru; Watercolor on Paper, H 30.7 × W 23 cm. Accession Number: A2211. New York: The Hispanic Museum and Library.. New York: The Hispanic Museum and Library. Available online: https://hispanicsociety.emuseum.com/objects/7872/bullfighter-on-horseback-peru (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Fierro Palas, Francisco. ca. 1840b. Creole on Horseback, Lima; Watercolor on Paper, H 22.9 × W 19.9 cm (irregular). Accession Number: A3300.14. New York: The Hispanic Museum and Library. Available online: https://hispanicsociety.emuseum.com/objects/11354/creole-on-horseback-lima (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Fierro Palas, Francisco. ca. 1850–1860. Vendedor de Velas. Watercolor on Paper. Lima: Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes. [Google Scholar]

- Fierro Palas, Francisco (attributed). ca. 1850a. Indian Woman Smoking Cigar in Front of Breadstand; Watercolor on Paper, H 19.7 × 24.6 cm. Accession Number: 1967.36.20. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery. Available online: https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/10800 (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Fierro Palas, Francisco (attributed). ca. 1850b. Interior of an Inn; Watercolor on Paper, H 44.7 × 58.8 cm. Accession Number: 1967.36.40. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery. Available online: https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/10860 (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Fierro Palas, Francisco (attributed). ca. 1850c. Piquanteria; Watercolor on Paper, H 23.3 × 18.9 cm. Accession Number: 1967.36.37. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery. Available online: https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/10850 (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Fierro Palas, Francisco (attributed). ca. 1850d. Woman with Basket on her Head; Watercolor on Paper, H 22.5 × 17.1 cm. Accession Number: 1967.36.32. New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery. Available online: https://artgallery.yale.edu/collections/objects/10837 (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Flores Galindo, Alberto. 1991. La Ciudad Sumergida, Aristocracia y Plebe en Lima, 1760–1830, 2nd ed. Lima: Editorial Horizonte. [Google Scholar]

- Gancedo, Omar Antonio. 1973. Descripción de las pipas de fumar tehuelches de la colección Francisco P. Moreno y Estanislao Zeballos. Revista del Museo de La Plata 8: 47–74. [Google Scholar]

- García Soto, Rubén, and Abraham Zavallos Zavallos. 1981. Informe Final de Estudio Arqueológico Histórico de la Quinta de Presa. Lima: Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Gilroy, Paul. 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Handler, Jerome. 2006. On the Transportation of Material Goods by Enslaved Africans During the Middle Passage: Preliminary Findings from Documentary Sources. African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter 9: 16. [Google Scholar]

- Handler, Jerome, and Neil Norman. 2007. From West Africa to Barbados: A Rare Pipe from a Plantation Slave Cemetery. The African Diaspora Archaeology Newsletter 10: 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jouve Martín, José Ramón. 2008. Esclavos de la ciudad letrada: Esclavitud, escritura y colonialismo en Lima (1650–1700). Lima: IEP. [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa, G. n.d. Aproximaciones a la Cerámica Fabricada por Cimarrones en Cuba. Una Contribución Arqueológica, Unpublished manuscript.

- Lemire, Beverly. 2021. Material Technologies of Empire: The Tobacco Pipe in Early Modern Landscape of Exchange in the Atlantic World. MAVCOR Journal, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letieri, Fabián, Gabriel Cocco, Guillermo Frittegotto, Leticia Campagnolo, Cristina Pasquali, and Carolina Giobertita. 2009. Catalogo Santa Fe la Vieja. Bienes Arqueológicos del Departamento de Estudios Etnográficos y Coloniales de la Provincia de Santa Fe. Santa Fe: Gobierno de Santa Fe—Consejo Federal de Inversiones. [Google Scholar]

- Linebaugh, Peter. 1982. All the Atlantic Mountains Shook. Labour/Le Travailleur 10: 87–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Macera, Pablo. 1966. Instrucciones Para el Manejo de las Haciendas Jesuitas del Perú, (ss. XVI–XVIII). Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Facultad de Letras y Ciencias Humanas, Departamento de Historia. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, J. Cameron. 2002. Negotiating African-American Ethnicity in the Seventeenth-Century Chesapeake: Colono Tobacco Pipes and the Ethnic Uses of Style. Oxford: Archaeopress. [Google Scholar]

- Monzón, Nathalie. 2019. Informe final del Proyecto de monitoreo arqueológico “Suministro, transporte, montaje, desmontaje, pruebas y puesta en servicio de la remodelación de redes de distribución primaria, secundaria, alumbrado público y acometidas domiciliarias en el centro histórico de Trujillo IIE localizado en el departamento de La Libertad, provincia de Trujillo, distrito de Trujillo”. Unpublished manuscript. Trujillo, Perú. [Google Scholar]

- Morales Cama, Joan Manuel, and Patricia Herrera. 2009. El Cónsul Tomás de la Bodega y Quadra y su ilustre descendencia limeña en el siglo XVIII. Revista del Archivo General de la Nación, Lima 129: 47–93. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, Neil L. 2008. An Archaeology of West African Atlanticization: Regional Analysis of the Huedan Palace Districts and Countryside (Bénin), 1650–1727. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, Neil L. 2015. On Cudjo’s Pipe: Smoking Dialogs in Diasporic Space. Paper presented at the 48th Conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology (SHA), Seattle, WA, USA, January 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Orser, Charles E., Jr. 1996. A Historical Archaeology of the Modern World. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ortíz, Fernando. 1940. Contrapunteo Cubano del Tabaco y el Azúcar. Havana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales. [Google Scholar]

- Ozanne, Paul. 1964. Tobacco Pipes of Accra and Shari. Legon: Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, Angelica. 1935. Pancho Fierro: Acuarelista Limeño. Lima: San Martín y CIA, S.A. [Google Scholar]

- Patiño, Diógenes, and Martha C. Hernández. 2017. The historical archaeology of black people and their descendants in Cauca, Colombia. Journal of Historical Archaeology, and Anthropological Sciences 4: 230–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras Barrenechea, Raúl, and Jaime Bayly. 1959. La Lima de Pancho Fierro. Lima: Instituto de Art Contemporáneo. [Google Scholar]

- ProLima (@prolima_chl). 2024. Durante el virreinato del Perú, el uso. Instagram, 21 January. [Google Scholar]

- Rancière, Jacques. 1999. Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy. Translated by Julie Rose. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rancière, Jacques. 2004. The Politics of Aesthetics. Edited and Translated by Gabriel Rockhill. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Rancière, Jacques. 2010. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. Edited and Translated by Steven Corcoran. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Sampeck, Kathryn, and Lucio Menezes Ferreira. 2020. Arqueología Afro-Latinoamericana: Temas, problemas y afro-reparación. Revista de Arqueología Histórica Argentina y Latinoamericana 13: 59–99. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Susy. 2021. Francisco Pancho Fierro y la memoria visual afrodescendiente de la guerra de Independencia del Perú. Anales del Museo de América 29: 173–90. [Google Scholar]

- Schávelzon, Daniel. 2003. Buenos Aires Negra. Arqueología de una Ciudad Silenciada. Buenos Aires: Emecé. [Google Scholar]

- Silliman, Stephen W. 2015. A requiem for hybridity? The problem with Frankensteins, purées, and mules. Journal of Social Archaeology 15: 277–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, Jerry, Juan Castañeda, and Flavia Zorzi. 2022. Una pipa con diseño afro procedente del centro histórico de Trujillo, Perú. Revista de Arqueología Histórica Argentina y Latinoamericana 15: 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, Marcos, and Camilla Agostini. 2012. Body marks, pots and pipes: Some correlations between African scarifications and pottery decoration in eighteenth and nineteenth-century Brazil. Historical Archaeology 46: 102–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, Marcos, and Tania Lima. 2022. Olhando, desejando, in-corporando: Cachimbos de barro na construção de comunidades diaspóricas. Vestígios— Revista Latino-Americana De Arqueologia Histórica 16: 7–27. [Google Scholar]

- Tardieu, Jean-Pierre. 2003. Los esclavos de los jesuitas del Perú en la época de la expulsión (1767). Caravelle 81: 61–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Robert Farris. 1973. An Aesthetic of the Cool. African Arts 7: 40–43, 65–67, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Robert Farris. 1983. Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- VanValkenburgh, Parker, Zachary Chase, Abel Traslaviña, and Brendan J. M. Weaver. 2016. Arqueologia historica en el Perú: Posibilidades y perspectivas. Boletin de Arqueologia PUCP 20: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Walker, Tamara J. 2017. Exquisite Slaves: Race, Clothing, and Status in Colonial Lima. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, Brendan J. M. 2015. Perspectivas para el desarrollo de una Arqueología de la diáspora africana en el Perú: Resultados preliminares del Proyecto Arqueológico Haciendas de Nasca. Allpanchis 80: 85–120. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, Brendan J. M. 2018. Rethinking the political economy of slavery: The hacienda aesthetic at the Jesuit vineyards of Nasca, Peru. Post-Medieval Archaeology 52: 117–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, Brendan J. M. 2021. An Archaeology of the Aesthetic: Slavery and Politics at the Jesuit Vineyards of Nasca. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 31: 111–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, Brendan J. M. 2022. Reflections on ‘material histories’ and the archaeology of slavery in Peru. Colonial Latin American Review 31: 591–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, Brendan J. M., Abel Traslaviña, Parker VanValkenburgh, and Zachary Chase. 2016. Arqueologia historica en el Perú: La sociedad andina en la transición económica, política y social. Boletin de Arqueologia PUCP 21: 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Weaver, Brendan J. M., Lizette A. Muñoz, and Karen Durand. 2019. Supplies, Status, and Slavery: Contested Aesthetics of Provisioning at the Jesuit Haciendas of Nasca. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 23: 1011–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelvington, Kevin A. 2001. The Anthropology of Afro-Latin America and the Caribbean: Diasporic Dimensions. Annual Review of Anthropology 30: 227–60. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).