Abstract

The First Intermediate Period was a time of cultural innovation and social competition. The collapse of the monarchy and the cultural productions it sponsored paved the way for the emergence of new artistic and cultural expressions, better adapted to a context of fragile authorities and competing local powers. Warfare between rival regional polities became frequent, so tomb scenes and funerary stelae from Middle and Upper Egypt began depicting military actions and men posing as archers. Moreover, local authorities sought the support of local levies and fellow citizens to strengthen and legitimate their fragile rule. Therefore, many monuments and inscriptions celebrate successful command, effective leadership, and caring about one’s city and its inhabitants. These conditions favoured the emergence of cultural innovations and social values aiming to express new identities. Depicting weapons, mainly bows, was crucial in this respect in some areas of Southern Egypt and echoed comparable phenomena occurring in neighbour regions like Nubia and the Levant.

Keywords:

archer; bow; cultural contact; Early Bronze Age; Egypt; ethnicity; identity; masculinity; Nubia; trade 1. Introduction

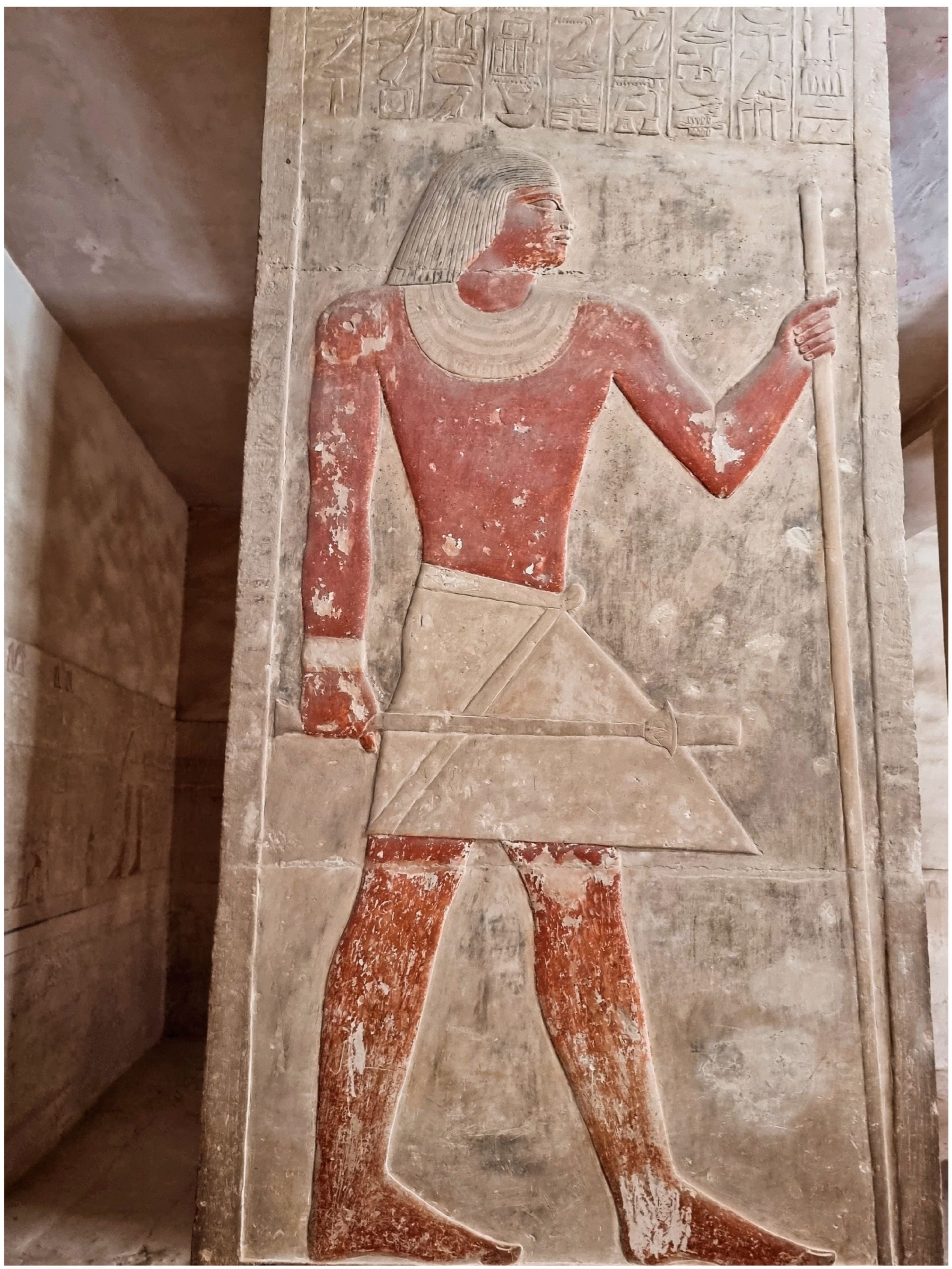

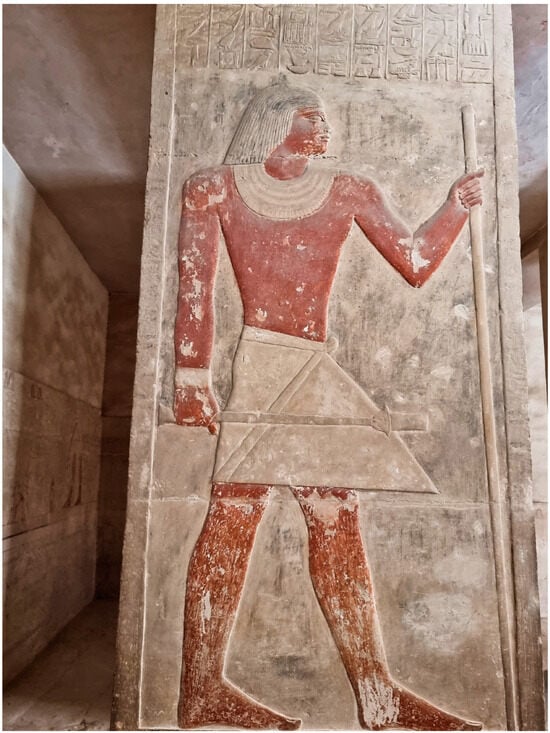

The canonical representation of masculine authority in statues and wall scenes of the Old Kingdom (approximately 2613–2160 BC; Figure 1) consisted of a man holding a stick, wearing high-quality clothes and power insignia (specifically skirts, sceptres, necklaces, or wigs) (Figure 2). Usually, he surveyed diverse activities taking place in his household, from agricultural labour and craft production to leisure, such as travelling by boat, spearing fish, or hunting fowl. Size contributed to accentuating that he—more rarely she—was the centre of an ordered world in which diverse categories of people gravitated around him. Subordinates and family members were represented at a lesser scale, and only in some cases was his wife depicted with the same size. Finally, other scenes emphasized more sportive, daring actions, like hunting with hounds, throwing sticks, and spearing hippopotamuses in a fluvial or marsh environment (Baines 2013). Significantly, warfare was irrelevant then to express the qualities of human audacity and command. When inscriptions and, much more rarely, decorated scenes referred to warfare, they evoked the organizational ability of the tomb’s owner (as in the case of Weni; see Strudwick 2005, pp. 354–55) or represented sieges of fortified settlements but never mentioned his direct implication in the combats (Monnier 2014). The only exception appears at Elephantine, on the southern border of Egypt. Its leaders were specialists in trade and contacts—the latter not always peaceful—with their African neighbours. Therefore, they mentioned either military actions against such populations, following the orders of the Pharaoh, or adverse circumstances, like being murdered by hostile populations or simply dying while carrying out a mission for the king abroad (Strudwick 2005, pp. 327–40). If a standard pose summarized what an efficient official was supposed to be in the third millennium BC, it was that of a diligent scribe or a dignified functionary performing the administrative and governmental duties expected from him.

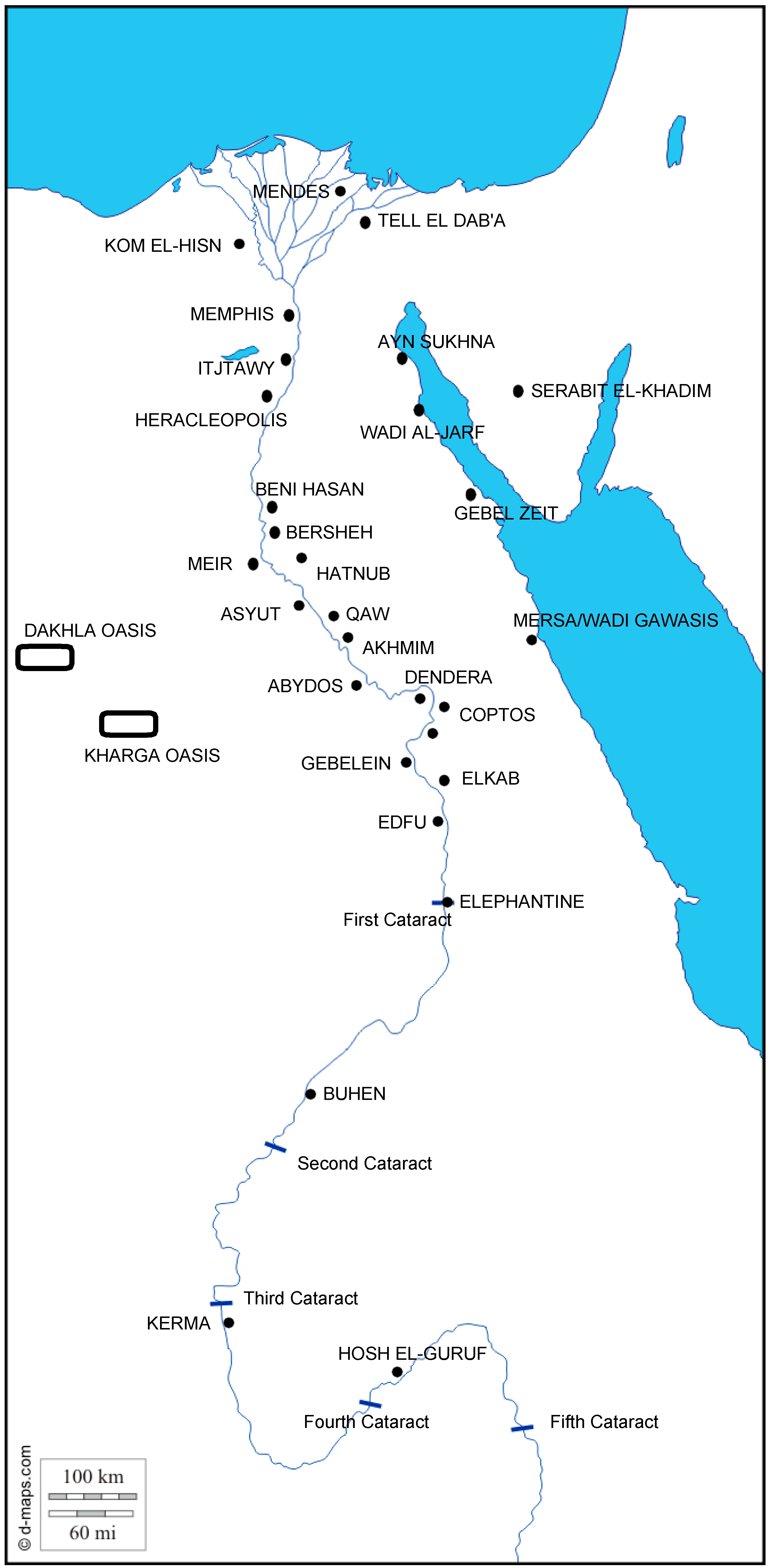

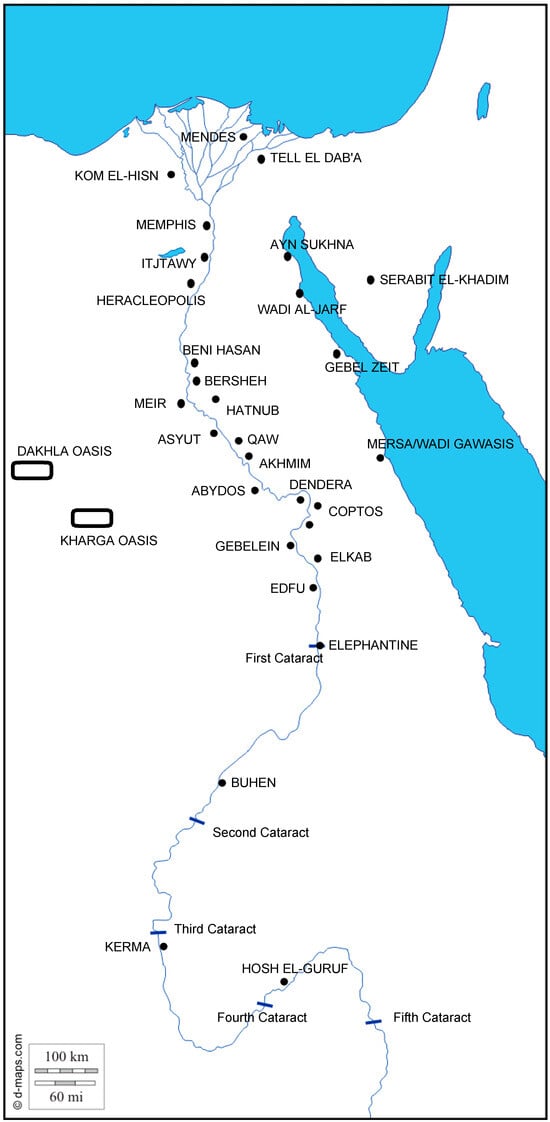

Figure 1.

Map of Egypt.

Figure 2.

Prof. Mortel, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons, URL: URL (accessed on 2 October 2024): https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tomb_of_Mereruka,_vizier_of_Teti,_6th_dynasty,_ca._2330_BCE;_Saqqara_(22).jpg.

However, things changed when the unified monarchy ended around 2160 BC, replaced by political conflict, territorial fragmentation, and rivalry between regional powers. The scope of action of many political actors became reduced to the local sphere, with no superior uncontested authority—like former pharaohs—capable of arbitrating among factions, imposing decisions over nobles and officials, or ruling the territory effectively under its alleged control. Consequently, this new political scenario introduced considerable challenges and transformations in the ideological domain as well, particularly when ambitious regional actors turned to warfare to solve conflicts and modify the existing balance of power. Leadership then expressed the personal qualities and initiative of local authorities, not obedience to administrative superiors or compliance with directives decided elsewhere. At the same time, fellow townspeople provided levies and political support, so leaders should gain their respect, provide for their needs, and conduct them aptly into battle. New icons emerged in this context, and one of the most popular in Egyptian visual arts was leaders represented as archers (Fischer 1962). Former symbols of authority—like sticks—continued to be used. Nevertheless, bows also gained relevance, a phenomenon also found outside the Nile Valley (Couturaud 2020).

In this article I will evaluate a particular icon that appeared in some private monuments of Southern Egypt between 2150–2000 BC, most particularly in the area between Elephantine and Coptos. Some Nubian and Egyptian men were represented holding a bow, a feature usually interpreted as if they were warriors and, in the case of Nubians, mercenaries in the service of Egyptian local leaders. However, wearing or being buried with weapons became a distinctive masculinity mark across Eurasia and North-Eastern Africa at the end of the third and the beginning of the second millennium BC. Moreover, bows were important tools in creating masculine identities in Nubia since 2500 BC. Finally, weapons do not necessarily suggest that their holders were warriors or were involved in military activities. They could also be merchants, as it happened in the Levant in this period. Having in mind that Nubians frequented Southern Egypt since the fourth millennium BC, particularly in the area where the majority of representations of bowmen come from, and that colonies of traders called miteru are well documented in localities like Elephantine or Gebelein around 2700–2500 BC, I will argue that bows became a mark of masculine identity that arrived to southern Egypt from Nubia around 2150 BC. Intense trading contacts between Egypt and Nubia favoured its diffusion there in a context of flourishing new identity expressions (Loprieno 1988; Moreno García 1997, 2016, 2018a; Moers 2004; Matić 2020; Pitkin 2023), so bows and bowmen do not necessarily nor always correspond to military activities but to new ways of expressing masculine identity.

2. Military Leadership

Little is known about the precise circumstances that culminated around 2160 BC to end the monarchy that had ruled Egypt for a thousand years. The epigraphic record shows no apparent signs of conflict or that the Pharaoh’s authority was contested. The rich repertory of royal decrees and inscriptions from Coptos, for example, describes the activities of local rulers at the service of the crown, which never included specific measures to face economic crisis, crop shortage, internal trouble, or foreign menace (Goedicke 1967, pp. 163–225; Mostafa 2014). As happened in other periods of Egyptian history, like the successions of Pepi II or Ramesses II, when kings died at a very advanced age after exceptionally long reigns, and when several of their presumptive heirs had passed away before their respective fathers, these conditions altered the expectations and strategies of many actors to the succession to the throne. Perhaps secondary actors tried their chances in an open political setting, so rivalries and power instability weakened the usual chain of command and the legitimacy channels that emanated from the royal palace. Another aspect to consider is that foreign exchanges flourished during this period, including contacts with new regions like the Aegean, so some local actors may have chosen to profit from these possibilities and act independently (Moreno García 2017). Obscure local kings emerged then, not only in Egypt but in Nubia as well, but the rare sources and monuments that mention them hardly cast any light on the scope of their authority (Williams 2013). Three factors seem crucial nevertheless: these kings were able to mobilize enough resources to build great monuments (like Dara: Monnier and Legros 2021) or send expeditions to the quarries (Wadi Hammamat); they are attested in regions deeply involved in foreign exchanges like the Wadi Hammamat (pathway to the Red Sea), Asyut (well connected to Nubia and the oases of the Western Nubia), and Elephantine (several Nubian “pharaohs” are documented in nearby graffiti: Williams 2013); and the earliest account of internal conflict and warfare seems related to control over flows of wealth (Moreno García 2017).

The inscriptions and decoration in the tomb of Ankhtifi of Mo’alla provide crucial clues about these events and the emerging new ideological values and their repercussions on the art produced by local rulers (Vandier 1950). According to his biographical account, Ankhtifi belonged to the family that ruled the third province of Upper Egypt and was trusted to restore order in the neighbouring province of Edfu and face rebellious Coptos and Thebes. The role of the monarchy seems somewhat blurred in the conflicts he faced. Ankhtifi seems to have acted in the king’s name and claims to be accountable before the crown’s regional delegate, the Upper Egypt’s overseer, and his council. However, Ankhtifi apparently relied on his own resources, as if the monarchy could only turn to a local authority to confront rebels and restore order in the south. At the same time, the geographical scope of Ankhtifi’s interventions suggests that he profited from the situation to expand his influence in southern Upper Egypt and eliminate rivals there. The third province of Upper Egypt remained his primary basis of power (he was ḥrj-tp ‘ȝ n Wṯz-Ḥr Nḫn “great chief of the second and third provinces of Upper Egypt” as well as jmj-r mš‘ n Nḫn “overseer of the troop of the third province of Upper Egypt”). From there, he extended his authority to Elephantine (the first province of Upper Egypt) and delivered foodstuffs to the sixth province (Dendera) and Nubia. Furthermore, he displayed military titles like jmj-r mš‘ “overseer of the troops, general” and rȝ mš‘ “mouth of the troops”, and his inscriptions give vivid details about campaigns against the Theban rebels, involving attacks on walled settlements in a landscape dotted with forts. He also took great pride in claiming that he was the vanguard of his troops and that he led his men gallantly (Vandier 1950, pp. 198–99). Finally, the scenes in his tomb include the representation of Nubian archers (Vandier 1950, plates 26, 35), war scenes (Vandier 1950, pp. 126–28, fig. 63–64), and a Nubian herder holding a bow (Vandier 1950, plate 20).

The presence of Nubians deserves some attention. Ankhtifi boasted about delivering food to the land of Wawat—Lower Nubia—and incorporated Nubian soldiers into his army. At the same time, in his tomb depictions he wears a coloured skirt atypical for Egyptian high officials (Vandier 1950, plates 14 and 40) but current among Nubians and foreigners. Finally, he holds two titles very uncommon in Upper Egypt outside Elephantine, those of jmj-r ‘w “overseer of interpreters” and jmj-r ḫȝswt “overseer of deserts/foreign countries”. Therefore, his duties were similar to those traditionally exerted by the Elephantine rulers, and he even obtained Nubian military support. The areas of Mo’alla and nearby Gebelein reveal traces of foreign peoples settled there since at least the middle of the third millennium BC. Shortly afterwards, other Nubian leaders provided military and political support to the contending Egyptian factions of the late third millennium BC. Nubian soldiers were represented in tombs at Elephantine, Gebelein, Asyut, or Thebes. Epigraphic evidence corroborates this impression, with Nubians engaged in Theban armies (like Tjehemau) or settled at Gebelein and Rizeiqat (Ejsmond 2017, 2019). The tomb of Iti of Gebelein, a “great chief of the province”, is exemplary. He was represented there holding a bow (Egyptian Museum Turin, photos 32 and 69: plates E00083 and E00077). Other scenes depict a Nubian (photos 70 and 71: plates C01287 and B00443), soldiers (photo 33: E00077), war prisoners (photo 77: plate C01443), and exotic African fauna like a giraffe (photo 64: plate C01442).1

The iconography of this period corroborates the importance of warfare. If Ankhtifi claimed to have attacked walled towns, several scenes from elite tombs in Middle and Upper Egypt (Beni Hassan, Thebes) and royal monuments (Deir el-Bahari) represent forts besieged and attacked by armies just before and during the period of reunification under Theban king Mentuhotep II, around 2050 BC (Monnier 2014). These same tombs also depict Asian soldiers, thus confirming the idea that the contingents of Nubian and Asian soldiers at the service of Egyptian regional lords favoured the diffusion of foreign weapons and military techniques in the Egyptian Valley. Thus, the frequent presence of Nubian, Asian, Libyan, and Eastern Desert populations in Middle Egypt could explain their participation in the conflicts in which local rulers were involved, such as those that erupted during the reign of Amenemhat I, according to a graffito from the time of governor Nehri I of Bersheh: “I prepared my troop of recruits and I set out for the fight with my city. It was I who acted as its rearguard in Shedytsha. No men were with me but my retinue; (but) people of the (foreign) lands of Medja and Wawat, Nubians and Asiatics, and Upper and Lower Egyptians were united against me; (yet) I came back, triumphant […] my city in its entirety being with me without loss […] I made my house as a door for every one who came, being in fear, on the day of strife” (Moreno García 2017, pp. 116–17). Warfare, contacts abroad, and the circulation of goods between Egyptian provinces and foreign territories thus appear closely connected with the emergence of new identities based on martial attitudes.

However, the Nubian influence in Egypt, particularly in Upper Egypt, may be due to a complex set of factors beyond the purely military sphere. Nubians and desert peoples frequented Upper Egypt well before the late third millennium BC. The papyri of Gebelein and the inscribed wooden box that contained these documents dated around 2500 BC, mention desert and foreign peoples settled in the area of Gebelein. Another papyrus fragment enumerates a list of mjtrw “long-distance traders”. Nubians also crossed the southern border of Egypt and were buried north of Elephantine since the late fourth millennium BC, a practice that continued in later centuries (an example in Moeller and Marouard 2018, pp. 39–40). One can mention the Pan-Grave people buried in their own cemeteries, close but outside the Egyptian settlements in Upper and Middle Egypt in the first half of the second millennium BC, or the continuous presence of Nubians and desert peoples around Gebelein in the Ramesside period, just to mention a few cases (Moreno García 2018a with bibliography). The activities of these peoples seem more related to small trade and herding than warrior occupations, particularly in the area between Gebelein and Elkab (Friedman 1992, 2000). However, scholars continue to privilege the interpretation of Nubians in Egypt as mercenaries at the service of their Egyptian masters, particularly during the late third millennium BC and the first centuries of the second millennium BC. According to this view, Nubians were deprived of any agency and could only fulfil a very specific but subordinate occupation, serving the interests of Egyptian actors. Thus, the stelae representing nḥsj “Nubians” discovered in the area of Gebelein should correspond to a colony of mercenaries, an interpretation popularized by the seminal article of Fischer (Fischer 1961) and reproduced by many other scholars since then (cf. Ejsmond 2017; Pitkin 2023; Hafsaas-Tsakos 2020, pp. 169–71; Meurer 2020; a more nuanced position in Raue 2019, pp. 570–72). Yet this interpretation is based more on Egyptological preconceptions than on social realities, which were more diverse and in which Nubian peoples fulfilled active roles as traders or intervening in Egyptian political matters as partners and allies (Matić 2014; Wegner 2018). Therefore, the representation of Nubians holding a bow may evoke a possible military occupation but also, and perhaps more decisively, a masculine identity marker imported in some regions of Egypt from Nubia due to the traditional cultural and economic links between both territories. In fact, the late third millennium BC was a time in which a new masculine identity related to the possession, representation, and burial of weapons spread across Eurasia and northeastern Africa. Depictions of Egyptian and Nubian men holding bows in southernmost Egypt (but not elsewhere) may thus correspond to the arrival of new cultural values into the area of Elephantine and Coptos as it became more integrated in the international economic networks of the early Middle Bronze Age (Moreno García 2017; Shemai of Coptos was involved in maritime expeditions to the southern Red Sea in the years previous to the rebellion of his province: Mostafa 2014, pp. 42–52).

3. International Influence: A New Masculine Identity?

The turn of the third millennium BC witnessed profound changes in the construction of masculine identities across the ancient Near East, principally related to the expansion of trade and mobile lifestyles and the diffusion of new weaponry (Wengrow 2009; Gernez 2018; Morris 2020, pp. 136–38; Couturaud 2020; Montanari 2021; in the case of Egypt, Diamond 2021 [with bibliography]). Many tombs of the Levantine Middle Bronze Age contained abundant metal objects and weapons, which leads to the conclusion that they reflected the male-warrior status of the individuals buried there. However, this interpretation has been challenged on several grounds, particularly because of its oversimplified correlation between grave goods, social status, and warfare (Wengrow 2009; Cohen 2012; Gernez 2011, 2014–2015; Doumet-Serhal 2014; Kletter and Levy 2016; Prell 2019b; Itach et al. 2022). Other possibilities point to the fact that the deceased were simply part of the local elite, even members of trading communities. Therefore, the wealth increase and trade expansion in the Levant and neighbouring regions during the Middle Bronze Age, together with advances in metallurgical techniques, inspired new burial customs based on shifting ideas about value and adult masculine identity.

Indeed, during the early second millennium BC, people expressed and emphasized their identity using particular burial practices in which weaponry played a prominent role. Individuals buried with daggers and particular axes expressed their status and importance through this prestigious equipment, which was not necessarily related to warfare or personal protection. At least in some cases, their status seems associated with caravan trade, as the presence of donkeys interred in some tombs suggests (Burke 2019; D’Andrea 2019; Prell 2019a, 2019b, 2021). Other items related to trade and exchanges, like the diffusion of balance weights in Egypt from 1700 BC and female figurines called “paddle dolls” from the very end of the third millennium BC, confirm this relationship (Prell and Rahmstorf 2019; Moreno García 2019). Several burials discovered at Kom el-Hisn, in the Western Delta, dating from the First Intermediate Period, are unique because they display Levantine weapons typical of contemporary “warrior tombs” found in the Levant (Wenke et al. 2016, pp. 348–50). However, the burials and weapons found at this locality did not necessarily correspond to the presence of foreign soldiers, mercenaries, or other military personnel. Quite the contrary, the visibility and apparent prosperity of Kom el-Hisn and nearby localities in the Western branch of the Nile seem related to the sudden relevance of this waterway and the consolidation of a trade route that connected the Aegean to the Western Delta, the Fayum area, Middle Egypt, and Nubia (Moreno García 2017; Manzo 2022). Similar weapons have also been discovered in areas under Heracleopolitan control or further south, like Sheikh Farag, Helwan, and, perhaps, Abydos (Prell 2021, pp. 135–43). Furthermore, the epigraphic record confirms the relevance of Asian warriors in the armies of the Heracleopolitan kingdom because several officials were overseers “of the troops of Asians (Aamu)” (Moreno García 2017, pp. 102–3). Finally, the First Intermediate Period saw the first attestation of the term ḏȝmw, which designated recruits and inexperienced soldiers as opposed to warriors ‘ḥȝwtjw (Stefanović 2007), in a fragmentary inscription from Hagarsa related to fighting (Kanawati and McFarlane 1995, p. 15). Another expression with military connotations, ‘nḫ n nwt “soldier of the town militia”, goes back to the same period (Berlev 1971).

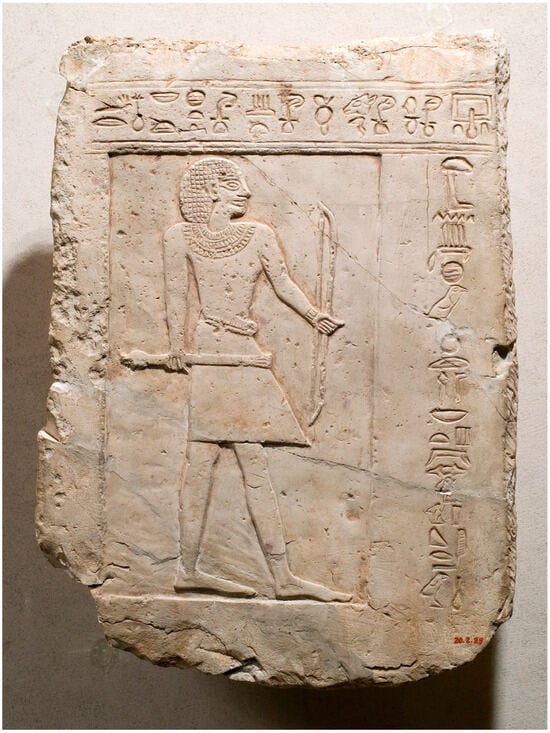

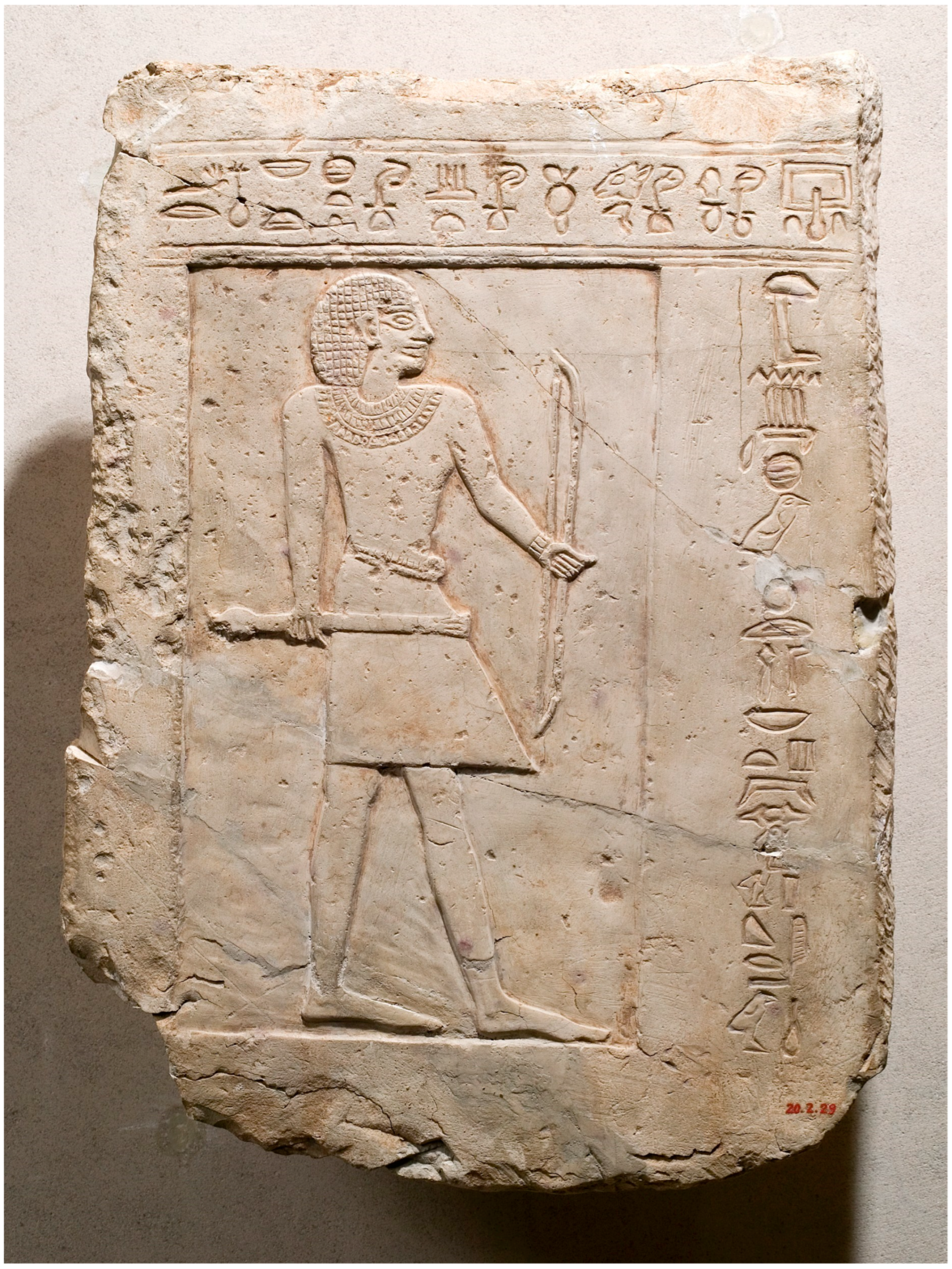

In this context, the motif of a man holding a bow became popular in many decorated stelae of the First Intermediate Period (Pitkin 2023, pp. 87–106) (Figure 3). This was a time of armed conflicts between rival local leaders, so many of them bore titles related with the direction of troops (like jmj-r mš‘ “overseer of the army”, attested at Edfu, Mo‛alla, Gebelein, Thebes, Dendera, Naga ed-Der, Akhmim, Hagarsa, and Asyut) or boasted about their commanding qualities. Sobeknakht of Dendera recalls in his stela the style of the famous inscription of Ankhtifi: “I prepared the vanguard of the troops (ḥȝt ḏȝmw), and I supplied it with all the strong nedjes (=modest one) at the time. I fought amid the valiant troops, and I did not go forth empty” (Silverman 2008). Holding a bow emphasized martial leadership in a pose that gained prestige and relevance (Fischer 1962). Governor Khety I of Asyut claimed: “I am one strong of bow, mighty with his arm, one much feared by his neighbours. I formed a troop of spearmen [… a troop of] bowmen, the best ‘thousand’ (=troop?) of Upper Egypt” (Lichtheim 1988, pp. 28–29). In some cases, men were buried with their bows, as in the tomb of Iqer from Dra Abu el-Naga (Galán 2015) and others from Asyut and Thebes (Cartwright and Taylor 2008).

Furthermore, this pose reproduced conventions about masculinity that foreigners could easily understand. Not by chance, the Nubians settled in the area of Gebelein represented themselves as archers during the First Intermediate Period, in what is usually interpreted as a military colony of warriors serving their Egyptian masters (Fischer 1961; Ejsmond 2017; Pitkin 2023, pp. 87–106). Nubian soldiers were represented, in fact, in the tombs of local leaders in Upper Egypt, like Elephantine, Mo‘alla, Thebes, and Asyut (Bietak 1985) and employed by Thebans and Heracleopolitans and their respective allies (Fischer 1961; Darnell 2003, 2004; El-Khadragy 2008). However, one cannot exclude, at least in part, that the Nubians living in Gebelein were depicted according to the new values that characterized men and masculinity and not because of any military function. In fact, they could also have been hunters (Ejsmond 2019, p. 34), and hunting scenes from the late third and early second millennium BC represented Nubian and Libyan auxiliaries. Perhaps this may explain a unique scene from Sharuna, dated from the late Old Kingdom, in which the tomb owner, Pepiankh/Ipi, his wife, and another man were represented holding bows (Schenkel and Gomaà 2004, plate 2). The exceptional depiction of a lady in this pose is particularly remarkable because only very rarely were Egyptian women depicted holding bows, always in warfare scenes (Matić 2021, pp. 40–41).

Figure 3.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons, URL (accessed on 2 October 2024): https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Funerary_stela_of_the_bowman_Semin_MET_20.2.29.jpeg.

Figure 3.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons, URL (accessed on 2 October 2024): https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Funerary_stela_of_the_bowman_Semin_MET_20.2.29.jpeg.

The discovery at Asyut of a decorated tomb with military scenes reveals that the use of Nubian troops was in no way limited to the southern Theban kingdom. Provincial warlords in the service of the northern Heracleopolitan rulers also enlisted them in their armies. The so-called “Northern soldiers-tomb”, probably from the late Eleventh Dynasty, displays four rows of men holding shields and battle axes (Abdelrahiem 2020, pp. 17–19, plates 38–39). Military scenes are well known from the scenes of other provincial necropoles, like Mo‛alla and Qubbet el-Hawa. However, what makes Asyut unique is that the decoration of some tombs depicted Nubian and Egyptian soldiers together in a provincial army. Thus, the tomb of Iti-ibi-iqer shows four registers of spearmen and archers headed by a troop commander on one wall of the chapel, whilst warriors were depicted on two registers on another wall. Armed with bows and battle axes, they are shown in various attitudes attacking some enemy, and Nubian archers are included among these soldiers. More Nubian archers are represented in a desert hunting scene on the chapel’s southern wall (El-Khadragy 2008, pp. 227–28). One might add the two sets of wooden models representing a troop of Nubian archers and a troop of Egyptian spearmen found in the tomb of Mesethi. All these Asyutian scenes and models appear in the tombs of provincial governors, each in command of a local troop of soldiers (Moreno García 2010, p. 28) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

URL (accessed on 2 October 2024): Aidan McRae Thomson, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nubian_Archers.jpg.

As for Egyptians, only kings were represented hunting with bows and arrows in the scenes of the Memphite region during the Old Kingdom. In contrast, some scenes from royal funerary complexes represented rows of warriors equipped with this weapon (Arnold 1999). For this reason, the representation of Egyptians holding a bow in many stelae from the First Intermediate Period deserves some comments. Of the twenty-five stelae from the First Intermediate Period—before the late Eleventh Dynasty—depicting the owner holding a bow and arrows, eighteen belong to native Egyptians and seven to Nubians. However, their geographical distribution shows some peculiarities. Native Egyptians are recorded only in stelae from Upper Egyptian provinces: Dendera (sixth province of Upper Egypt: one example), Coptos (fifth province of Upper Egypt: twelve stelae), and Thebes (fourth province of Upper Egypt: five stelae). Iwt, an official from Coptos, was “overseer of interpreters of the (Nubian) land of Yam” (Fischer 1964, pp. 27–30), so the local presence of Nubians may explain the abundance of stelae representing bowmen in Coptos. Nubians appear in the Theban province (six stelae) and the Third province of Upper Egypt (one case). In other instances, the Nubians represented in the stelae did not hold a bow and arrows: Thinis (eighth province of Upper Egypt: two stelae) and Thebes (fourth province of Upper Egypt: thirteen stelae) (Pitkin 2023, pp. 91–94). Holding a bow and arrows was thus a particular characteristic of the stelae from the Coptite and Theban provinces. However, it was absent in stelae from other regions with a significant presence of Nubian soldiers, like Asyut. That both provinces rebelled against the Memphite kings, according to Ankhtifi’s inscription, and that Ankhtifi’s titles and mission seem connected with Nubia suggest that Nubian culture may have played a crucial role in the construction of a new Egyptian masculinity related to the use of bows. Another clue that points in the same direction is the frequent presence in Theban burials of “paddle dolls”, the protective female figurines that represent exotic foreign women, in all probability Nubians, while their occurrence is much rarer in the tombs from Middle Egypt or the Memphite region (Moreno García 2017, p. 107). Finally, holding weapons never became a mark of masculine identity in Middle and Lower Egypt despite the Levantine presence there in the late third and early second millennium BC. Officials and dignitaries were represented according to the dress and dignity codes developed in the Old Kingdom, where sticks, necklaces, and specific garments and insignia were fundamental to express rank and prestige.

4. A Nubian Origin?

Indeed, the Nubian influence on Egyptian culture and customs may have been considerable at the end of the third millennium BC (Moreno García 2018a, 2018b). Bows, accompanied by quivers, arrows, and wrist guards, are exclusively found in male burials from Kerma from 2300 BC until 1750 BC. However, large wooden sticks, reminiscent of a shepherd’s staff, are only found in female graves (Honegger and Fallet 2015; Honegger 2023, p. 74). Weapons served thus to characterize gender differences and, in the case of the bows, they were not necessarily placed in tombs to express the activity of the deceased, but also had a symbolic connotation related to male status (Honegger 2023, p. 77). Additionally, dogs were often found in the tombs of Nubian archers during the very late third millennium BC as well (Manzo 2016, p. 13). Later on, during the first half of the second millennium BC, Nubians from the Kerma culture were buried with daggers and show frequent skeletal trauma, hence their interpretation as warriors (Hafsaas-Tsakos 2013; Manzo 2016; Prell 2021, p. 143). However, the early presence of weapons at Kerma, from the late third millennium BC, suggests that military values and ideology played an essential role in the nascent identity of the Kush kingdom (Manzo 2016). Not by chance, the bow was considered the typical Nubian weapon by the Egyptians, who named the southern lands the “Bow-land” (Tȝ Stj).

The contrast with the cultural influence of Levantine weaponry is notable. The Levantine weapons found in the cemetery of Kom el-Hisn or the scenes with Levantine warriors that decorated Egyptian tombs played no role in how Egyptians represented themselves before and after the reunification of Egypt. Quite the contrary, such scenes show a sharp contrast between Egyptians and Asians in the weapons and clothes they used (Jaroš-Deckert 1984, plates 1, 3, 14, 17, leaflet 1). Perhaps the survival and prestige of the Memphite traditions in the north blocked the manifestation of alternative identities built on different, imported values. The weight of such traditions may explain why holding bows and arrows disappeared in the representation of Egyptian officials once the unified monarchy was restored, except for hunting scenes.

5. Conclusions

The First Intermediate Period was a time of profound socio-political changes. The absence of a central authority, replaced by rival regional powers, inaugurated an era of uncertainty and legitimacy quest. It was also a time of increasing trade and diffusion of cultural codes easily recognizable across borders because of the frequent contacts between peoples from different origins. Levantine peoples, for instance, crossed and settled in Lower and Middle Egypt, integrated into Egyptian armies and favoured trading exchanges between the Nile Valley and the Levant, before and after the reunification of Egypt under the Theban king Mentuhotep II. One such code concerned using weapons to build a new masculine identity. However, Egyptians showed little interest in displaying Levantine weapons and instead preferred the bow. This particularity and the restricted geographical diffusion of bows represented in private monuments, almost exclusively in Egypt’s southernmost provinces, suggest that other influences operated in this choice. Nubians had been buried with bows, irrespective of age, since the last centuries of the third millennium BC, a practice not necessarily related to military activities but to a new masculine identity. When Nubians became increasingly involved in Egyptian affairs during the First Intermediate Period, it is plausible that the bow also created new masculine identities in Egypt, especially in those provinces where Nubians lived and fought with their Egyptian neighbours. Egyptian art and, in particular, its rich repertoire of images, stelae, and statuary proves thus invaluable to detect the changes that redefined masculine identity and self-representation in a time of deep social and political changes. Thanks to Egyptian art, these changes found a powerful means of expression that influenced the construction of social and gender identities across borders.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | https://archiviofotografico.museoegizio.it/en/archive/gebelein/northern-hill/painted-tomb-of-iti-and-neferu/ (accessed on 2 October 2024). |

References

- Abdelrahiem, Mohamed. 2020. The Northern Soldiers-Tomb (H11.1) at Asyut. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Dorothea. 1999. Group of archers. In Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 264–67. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, John. 2013. High Culture and Experience in Ancient Egypt. Sheffield: Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- Berlev, Oleg D. 1971. Les prétendus ‘citadins’ au Moyen Empire. Revue d’Égyptologie 23: 23–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bietak, Manfred. 1985. Zu den nubischen Bogenschützen aus Assiut. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Ersten Zwischenzeit. In Mélanges Gamal Eddin Mokhtar. Edited by Paule Posener-Krieger. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, vol. I, pp. 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Aaron. 2019. Amorites in the Eastern Nile Delta: The identity of Asiatics at Avaris during the Early Middle Kingdom. In The Enigma of the Hyksos. Volume I. Edited by Manfred Bietak and Silvia Prell. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright, Caroline, and John H. Taylor. 2008. Wooden Egyptian archery bows in the collections of the British Museum. The British Museum Technical Research Bulletin 2: 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Susan L. 2012. Weaponry and warrior burials: Patterns of disposal and social change in the southern Levant. In The 7th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Edited by Roger Matthews and John Curtis. London: The British Museum and University College London, vol. 2, pp. 307–19. [Google Scholar]

- Couturaud, Barbara. 2020. Kings or soldiers? Changes in the figurative representation of fighting heroes by the end of the Early Bronze Age. In Tales of Royalty. Notions of Kingship in Visual and Textual Narration in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Elisabeth Wagner-Durand and Julia Linke. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 109–37. [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea, Marta. 2019. Before the cultural koinè: Contextualising interculturality in the ‘Greater Levant’ during the Late Early Bronze Age and the Early Middle Bronze Age. In The Enigma of the Hyksos. Volume I. Edited by Manfred Bietak and Silvia Prell. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 13–45. [Google Scholar]

- Darnell, John C. 2003. The rock inscriptions of Tjehemau at Abisko. Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 130: 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnell, John C. 2004. The route of Eleventh Dynasty expansion into Nubia. An interpretation based on the rock inscriptions of Tjehemau at Abisko. Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 131: 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, Kelly-Anne. 2021. Masculinities and the mechanisms of hegemony in the Instruction of Ptahhotep. In His Good Name: Essays on Identity and Self-Presentation in Ancient Egypt in Honor of Ronald J. Leprohon. Edited by Christina Geisen, Jean Li, Steven Shubert and Kei Yamamoto. Atlanta: Lockwood Press, pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Doumet-Serhal, Claude. 2014. Mortuary practices in Sidon in the Middle Bronze Age: A reflection on Sidonian society in the second millennium BC. In Contextualising Grave Inventories in the Ancient Near East. Edited by Peter Pfälzner, Herbert Niehr, Ernst Pernicka, Sarah Lange and Tina Köster. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ejsmond, Wojciech. 2017. The Nubian mercenaries of Gebelein during the First Intermediate Period in the light of recent field research. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections 14: 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ejsmond, Wojciech. 2019. Some thoughts on Nubians in Gebelein region during First Intermediate Period. In Current Research in Egyptology 2018. Edited by Marie Peterková Hlouchová, Dana Bělohoubková, Jiří Honzl and Věra Nováková. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- El-Khadragy, Mahmoud. 2008. The decoration of the rock-cut chapel of Khety II at Asyut. Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 37: 219–41. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Henry George. 1961. The Nubian mercenaries of Gebelein during the First Intermediate Period. Kush 9: 44–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Henry George. 1962. The archer as represented in the First Intermediate Period. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 21: 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Henry George. 1964. Inscriptions from the Coptite Nome, Dynasties VI–XI. Roma: Pontificium Institutum Biblicum. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Renee. 1992. Pebbles, pots and petroglyphs: Excavations at HK64. In The Followers of Horus. Studies Dedicated to Michael Allen Hoffman. Edited by Renee Friedman and Barbara Adams. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Renee. 2000. Pots, pebbles and petroglyphs, part II: 1996 excavations at Hierakonpolis Locality HK64. In Studies in Ancient Egypt in Honour of H. S. Smith. Edited by Anthony Leahy and John Tait. London: Egypt Exploration Society, pp. 101–8. [Google Scholar]

- Galán, José Manuel. 2015. 11th Dynasty burials below Djehuty’s courtyard (TT 11) in Dra Abu el-Naga. Bulletin of the Egyptological Seminar 19: 331–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gernez, Guillaume. 2011. The exchange of products and concepts between the Near East and the Mediterranean: The example of weapons during the Early and Middle Bronze Ages. In Intercultural Contacts in the Ancient Mediterranean. Edited by Kim Duistermaat and Ilona Regulski. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 202. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 327–41. [Google Scholar]

- Gernez, Guillaume. 2014–2015. Tombes à armes et tombes de guerriers au Liban au Bronze Moyen. In The Final Journey. Funerary Customs in Lebanon from Prehistory to the Roman Period. Edited by Guillaume Gernez. Archaeology and History in the Lebanon 40–41. London: The Lebanese British Friends of the National Museum, pp. 45–73. [Google Scholar]

- Gernez, Guillaume. 2018. Metal weapons. In Arcane Interregional. Vol. II: Artefacts. Edited by Marc Lebeau. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 39–76. [Google Scholar]

- Goedicke, Hans. 1967. Königliche Dokumente aus dem Alten Reich. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Hafsaas-Tsakos, Henriette. 2013. Edges of bronze and expressions of masculinity: The emergence of a warrior class at Kerma in Sudan. Antiquity 87: 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafsaas-Tsakos, Henriette. 2020. The C-Group people in Lower Nubia: Cattle pastoralists on the frontier between Egypt and Kush. In The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia. Edited by Geoff Emberling and Bruce B. Williams. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 157–77. [Google Scholar]

- Honegger, Matthieu. 2023. The Archers of Kerma: Warrior Image and Birth of a State. Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies 8: 69–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honegger, Matthieu, and Camille Fallet. 2015. Archers’ tombs of the Kerma Ancien. Documents de la Mission Archéologique Suisse au Soudan 6: 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Itach, Gilad, Dor Golan, and Shirly Ben Dor Evian. 2022. An elite Middle Bronze IIA warrior tomb from Yehud, Central Coastal Plain, Israel. Bulletin of the American Society of Overseas Research 388: 153–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroš-Deckert, Brigitte. 1984. Das Grab des Jnj-jtj.f: Die Wandmalereien der XI Dynastie. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Kanawati, Naguib, and Ann McFarlane. 1995. The Tombs of El-Hagarsa. Vol. III. Sydney: Australian Centre for Egyptology. [Google Scholar]

- Kletter, Raz, and Yosi Levy. 2016. Middle Bronze Age burials in the Southern Levant: Spartan warriors or ordinary people? Oxford Journal of Archaeology 35: 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtheim, Miriam. 1988. Ancient Egyptian Autobiographies Chiefly of the Middle Kingdom: A Study and an Anthology. Freiburg-Göttingen: Universitätsverlag and Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Loprieno, Antonio. 1988. Topos und Mimesis. Zum Ausländer in der ägyptischen Literatur. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Manzo, Andrea. 2016. Weapons, ideology and identity at Kerma (Upper Nubia, 2500–1500 BC). Annali Sezione Orientale 76: 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, Andrea. 2022. Ancient Egypt in Its African Context. Economic Networks, Social and Cultural Interactions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matić, Uroš. 2014. ‘Nubian’ archers in Avaris: A study of culture historical reasoning in archaeology of Egypt. Issues in Ethnology and Anthropology 9: 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matić, Uroš. 2020. Ethnic Identities in the Land of the Pharaohs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matić, Uroš. 2021. Violence and Gender in Ancient Egypt. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Meurer, Georg K. 2020. Nubians in Egypt from the Early Dynastic Period to the New Kingdom. In The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia. Edited by Geoff Emberling and Bruce B. Williams. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller, Nadine, and Gregory Marouard. 2018. The development of two early urban centres in Upper Egypt during the 3rd millennium BC. The examples of Edfu and Dendara. In From Microcosm to Macrocosm. Individual Households and Cities in Ancient Egypt and Nubia. Edited by Julia Budka and Johannes Auenmüller. Leiden: Sidestone, pp. 29–58. [Google Scholar]

- Moers, Gerald. 2004. Unter den Sohlen Pharaos: Fremdheit und Alterität im pharaonischen Ägypten. In Abgrenzung—Eingrenzung: Komparatistische Studien zur Dialektik kultureller Identitätsbildung. Edited by Frank Lauterbach, Fitz Paul and Ulrike-Christine Sander. Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Philologisch-Historische Klasse, Dritte Folge, Band 264. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 81–160. [Google Scholar]

- Monnier, Franck. 2014. Une iconographie égyptienne de l’architecture défensive. Égypte Nilotique et Méditerranéenne 7: 173–219. [Google Scholar]

- Monnier, Franck, and Rémi Legros. 2021. Le complexe funéraire monumental de Dara (reconstitution et datation). Journal of Ancient Egyptian Architecture 5: 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Montanari, Daria. 2021. Four broad fenestrated axes in the British Museum: some considerations on a symbolic weapon between the 3rd and the 2nd millennium BC. Egitto e Vicino Oriente 25: 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno García, Juan Carlos. 1997. Études sur l’administration, le pouvoir et l’idéologie en Égypte, de l’Ancien au Moyen Empire. Ægyptiaca Leodiensia, n° 4. Liège: Centre d’informatique de Philosophie et Lettres, pp. 1–92. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno García, Juan Carlos. 2010. War in Old Kingdom Egypt (2686–2125 BCE). In Studies on War in the Ancient Near East. Collected Essays on Military History (AOAT, 372). Edited by Jordi Vidal. Münster: Ugarit Verlag, pp. 5–41. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno García, Juan Carlos. 2016. Social inequality, private accumulation of wealth and new ideological values in late 3rd millennium BCE Egypt. In Arm und Reich—Zur Ressourcenverteilung in prähistorischen Gesellschaften (8. Mitteldeutscher Archäologentag). Edited by Harald Meller, Hans Peter Hahn, Reinhard Jung and Roberto Risch. Halle: Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte Halle (Saale), pp. 491–512. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno García, Juan Carlos. 2017. Trade and power in ancient Egypt: Middle Egypt in the late third/early second millennium BC. Journal of Archaeological Research 25: 87–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno García, Juan Carlos. 2018a. Elusive ‘Libyans’: identities, lifestyles and mobile populations in NE Africa (late 4th—early 2nd millennium BCE), Journal of Egyptian History 11: 147–84. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno García, Juan Carlos. 2018b. Leather processing, castor oil, and desert/Nubian trade at the turn of the 3rd/2nd millennium BC: some speculative thoughts on Egyptian craftsmanship. In The Arts of Making in Ancient Egypt: Voices, Images, Objects of Material Producers, 2000–1550 BC. Edited by Gianluca Miniaci, Juan Carlos Moreno García, Stephen Quirke and Andréas Stauder. Leiden: Sidestone Press, pp. 159–73. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno García, Juan Carlos. 2019. Textile display in Middle Kingdom Egypt (late third/early second millennium BC): Symbolism, social status and long-distance trade. In Textiles in Ritual and Cultic Practices in the Ancient Near East from the Third to the First Millennium BC (AOAT 431). Edited by Salvatore Gaspa and Matteo Vigo. Münster: Ugarit Verlag, pp. 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, Helen. 2020. Machiavellian masculinities: Historicizing and contextualizing the “civilizing process” in ancient Egypt. Journal of Egyptian History 13: 127–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, Maha M. F. 2014. The Mastaba of Šmȝj at Nag‘ Kom El-Koffar, Qift. Volume 1: Autobiographies and Related Scenes and Texts; Cairo: Ministry of Antiquities and Heritage.

- Pitkin, Melanie. 2023. Egypt in the First Intermediate Period: The History and Chronology of its False Doors and Stelae. London: Golden House Publcations. [Google Scholar]

- Prell, Silvia. 2019a. A ride to the netherworld: Bronze Age equid burials in the Fertile Crescent. In The Enigma of the Hyksos. Volume I. Edited by Manfred Bietak and Silvia Prell. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 107–24. [Google Scholar]

- Prell, Silvia. 2019b. Burial customs as cultural marker: A ‘global’ approach. In The Enigma of the Hyksos. Volume I. Edited by Manfred Bietak and Silvia Prell. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 125–47. [Google Scholar]

- Prell, Silvia. 2021. The Enigma of the Hyksos Volume III: Vorderasiatische Bestattungssitten im Ostdelta Ägyptens—Eine Spurensuche. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. [Google Scholar]

- Prell, Silvia, and Lorenz Rahmstorf. 2019. Im Jenseits Handel betreiben Areal A/I in Tell el-Dabʿa/Avaris—die hyksoszeitlichen Schichten und ein reich ausgestattetes Grab mit Feingewichten. In The Enigma of the Hyksos. Volume I. Edited by Manfred Bietak and Silvia Prell. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, pp. 165–97. [Google Scholar]

- Raue, Dietrich. 2019. Nubians in Egypt in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC. In Handbook of Ancient Nubia. Edited by Dietrich Raue. Berlin-Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 567–88. [Google Scholar]

- Schenkel, Wolfgang, and Farouk Gomaà. 2004. Scharuna I. Der Grabungsplatz, die Nekropole, Gräber aus der Alten-Reichs-Nekropole. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, David P. 2008. A reference to warfare at Dendereh, prior to the unification of Egypt in the Eleventh Dynasty. In Egypt and Beyond: Essays Presented to Leonard H. Lesko. Edited by Stephen E. Thompson and Peter Der Manuelian. Providence: Department of Egyptology and Western Asian Studies, Brown University, pp. 319–31. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanović, Danijela. 2007. Ḏȝmw in the Middle Kingdom. Lingua Aegyptia 15: 217–29. [Google Scholar]

- Strudwick, Nigel C. 2005. Texts from the Pyramid Age. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. [Google Scholar]

- Vandier, Jacques. 1950. Mo‛alla: la tombe d’Ankhtifi et la tombe de Sébekhotep. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner, Josef. 2018. The stela of Idudju-Iker, Foremost-one of the Chiefs of Wawat. New evidence on the conquest of Thinis under Wahankh Antef II. Revue d’Égyptologie 68: 153–209. [Google Scholar]

- Wengrow, David. 2009. The voyages of Europa: Ritual and trade in the eastern Mediterranean circa 2300–1850 BC. In Archaic State Interaction: The Eastern Mediterranean in the Bronze Age. Edited by William A. Parkinson and Michael L. Galaty. Santa Fe: School of Advanced Press, pp. 141–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wenke, Robert J., Richard W. Redding, and Anthony Cagle. 2016. Kom el-Hisn (ca. 2500–1900 BC). An Ancient Settlement in the Nile Delta. Atlanta: Lockwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Bruce. 2013. Three rulers in Nubia and the early Middle Kingdom in Egypt. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 72: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).