Abstract

Scholarship has described Deir el-Medina as a sophisticated community composed of highly trained and educated individuals, at least compared to most ancient Egyptian villages that were primarily focused on agrarian labor. The tombs at Deir el-Medina indicate that some community members were well-off financially and may have aspired to reach elite levels in ancient Egypt’s social hierarchy. However, this understanding of Deir el-Medina’s community lacks the nuance of the hierarchical structure that defines success and status among the workers, artists, and craftspeople living in the community. This paper will investigate how one’s status within the community might dictate the allocation of artistic roles in the execution of painted royal tomb scenes. It will explore who within the community would have the privilege of depicting the primary motifs of a tomb and who would be responsible for less noticeable areas of the tomb.

1. Introduction

Deir el-Medina is a planned settlement nestled in the Theban cliffs, adjacent to the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens. The village was founded during the reign of Thutmoses I in the 18th Dynasty (1550–1295 BCE) to house the workmen needed to excavate and decorate the royal tombs, along with their families. Deir el-Medina is unusual because it is an exceptionally well-preserved domestic site, due to its location in the desert, away from the area of inundation and modern settlements. The wealth of textual, artistic, and archeological data provides rich insights into the day to day lives of the people who lived there for a span of about 500 years. Compared to other towns in ancient Egypt, which were likely centered around agriculture, Deir el-Medina’s community primarily consisted of scribes and artists.1 While urban centers, such as nearby Thebes, supported some privileged, educated populations, Deir el-Medina is unique for its high ratio of skilled and educated inhabitants. The site is also noteworthy because of its general isolation from other ancient populations and communities (Babcock 2022, p. 22).

Gaston Maspero began work in Deir el-Medina in the 1880s to preserve the site from looters who were removing objects to sell to private collectors and European museums (Gobeil 2018, p. 315). From 1905 to 1909, the ancient town was excavated by Ernesto Schiaperelli for the Museo Egizio in Turin, after which the concession was passed to Georg Möller who worked on site for the Königliche Museen (now the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin). Möller left the site at the beginning of the First World War, and the Institut français d’archéologie orientale (IFAO) took over. In 1921, Bernard Bruyère, representing the IFAO, began excavating some of the decorated tombs adjacent to the settlement. His work continued until the early 1950s, during which time he discovered new tombs and chapels. Bruyère also excavated “The Great Pit”, which had never been explored before because of the logistical difficulties that it presented (Gobeil 2018, p. 318). The pit, which is 50 m deep, yielded remarkable results, including over five thousand ostraca, or limestone flakes, which contained letters, inventory lists, work journals, and receipts (Bruyère 1926, no. 360). In addition to the ostraca, numerous hieratic papyri have been found at the site (Haring 2022, p. 52). These finds form one of the richest depositories of ancient texts providing clear evidence that the town was primarily occupied during the Ramesside period, or the 19th and 20th Dynasties (1292–1090 BCE). Because of this, the scope of this study is focused on Deir el-Medina’s community during the Ramesside period.

Much of the textual data that Bruyère recovered also provide insights into how labor was organized. Labor was structured into a clear hierarchy to efficiently control the workers and their rate of production. The entire work crew responsible for constructing and decorating the royal tombs was known as a “gang” (jsṯ), which was divided into two sides: the “right” and the “left”, each of which was responsible for working on the corresponding side of the tomb (Gabler 2018, p. 14; McDowell 1999, pp. 4–5; B. Davies 1999, p. xix). Each group was led by two foremen, or the “Great ones of the crew” (ꜥꜣ n jsṯ). Administrative documents indicate that most workmen were called “men of the crew” (rmṯ-jsṯ). Some of these men could be promoted to draftsmen (sš-kd), who were chiefly responsible for painting and decorating the royal tombs. Other workers included the chisel bearers (ṯ’y-mḏꜣṯ), responsible for relief carving, and those who assisted the foremen (jdnw) (Cooney 2007, p. 13). The total number of workmen assigned to the tomb could fluctuate according to the demands of the king (B. Davies 2017, p. 205; McDowell 1999, p. 5; B. Davies 1999, p. xix). So, while workers typically inherited their positions within the community, which was also characteristic of other professions in ancient Egypt (Brewer and Teeter 1999, pp. 77–79; Keller 1993, p. 51), there was opportunity for mobility; some artists could be invited into the crew, and others could leave, or be compelled to leave to seek work elsewhere (Collier 2014, pp. 6–9; McDowell 1994, pp. 42–43; Lesko 1994, p. 39).

For this paper, I am examining the relationships among the artists, and specifically the painters, who lived in the village and who were primarily tasked to decorate the royal tombs during the Ramesside period. There seems to have been a hierarchy among painters, because there was a head painter (ḥrj sš-kd) who oversaw the work of the other draftsmen (sš-kd) from both “left” and “right” sides (Keller 2001, p. 74; Bogoslovsky 1980, pp. 94–95). Sometimes, though, the terms seem to be interchangeable, as one text may refer to an individual both as a ḥrj- sš-kd and a sš-kd (Bogoslovsky 1980, p. 95). While this hierarchical structure was determined by one’s hereditary rights and seniority, other hierarchical divisions were likely at play.

I propose that the skillfulness of a painter in Deir el-Medina, which may not necessarily correlate with seniority or lineage, might also dictate which artistic motifs and images a painter could be assigned in the royal tombs. This paper, therefore, defines how skillfulness was assessed in Ramesside Deir el-Medina and how skill may impact one’s professional standing as a painter in the royal tombs.

To establish what would be considered skillful by Ramesside painters in Deir el-Medina, this paper assumes that the treatment of the figures and motifs within the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings and Queens set the standards of what was considered skillful painting. To gain a foundational understanding of how skillful painting was achieved, we must first examine the drawings of the figured ostraca, or illustrated limestone flakes, from Deir el-Medina. The quality of drawing among these ostraca varies greatly. But many of these are clearly drawn by artists who are practicing their painterly skillsets, often with the goal of depicting forms that are consistent with the style of painting found in the royal tombs.

Inherkhau’s (ii) tomb (TT 359) is also specifically addressed in this study because it clearly shows the different skill levels of two painters, the brothers Hormin (i) and Nebnefer (ix). While they both held the same position within the community of painters at Deir el-Medina, Hormin (i) was clearly more skilled at painting than Nebnefer (ix). The visual inconsistency in Inherkhau’s (ii) tomb, which is a result of Hormin (i) and Nebnefer’s (ix) difference in skill, is unlike what one would find in a royal tomb, where artistic hands were usually managed to achieve a standard of visual consistency (Laboury 2020, p. 94). Knowing this, it is possible that Nebnefer (ix) did not have the same kinds of painting assignments as Hormin (i) in royal tomb contexts, despite possessing the same occupational title and working in the same gang. Such a method of organizing artistic labor in the royal tombs ensures that its paintings conform to an overall royal aesthetic that serves divine royal authority.

This paper has two goals. One is to explore how skillfulness was assessed in Ramesside Deir el-Medina. The second is to consider how skill may impact one’s professional standing as a painter in the royal tombs. The latter goal involves using a previously overlooked cross-cultural comparison to investigate the mechanisms of labor organization and artistic training in Deir el-Medina, the centuries-old bronze-casting guild of the Benin kingdom in the modern nation of Nigeria. Oral tradition in Benin states that one’s skill and experience in royal bronze-casting determines who should depict what on the bronze plaques that are installed in the royal court. This practice may bear similarities to the assessment and organization of painters in the Ramesside royal tombs.

2. Defining Terms

Whether there was a concept of art in ancient Egypt has been discussed extensively (Babcock 2022, pp. 28–29; Baines 2015, pp. 2–3; Baines 2007, p. 299). Egyptologists have noted that ancient Egyptian art had a fundamentally different purpose from modern and Eurocentric conceptions of what art is supposed to be, which prioritizes aesthetics and is divorced from function. One art historical philosophy that encapsulates this idea, “Art for art’s sake”, birthed a theoretical movement in 19th century Europe, which has been engrained in European and American thought ever since (Lamarque 2010, p. 205; Greenberg 1961, p. 5). This definition of art also affected how theorists and critics defined “the artist” as an independent creative genius, unbeholden to workshops, guilds, and patrons (Singer 1954, pp. 345–47). Ancient Egyptian creators would not be considered artists under these criteria (Laboury and Devillers 2022, pp. 163–65; Baines 2015, pp. 2–3; Laboury 2012, p. 199), resulting in uncertainty about what to call them (Andreu-Lanoë 2022, pp. 68–69). However, this paper is not concerned with justifying the presence of art or artists in ancient Egypt. As Dimitri Laboury and Alisée Devillers have noted, art history is moving away from its initial Euro-centric and modern-centric foundations, and so it would be appropriate for Egyptology to reject these parameters as well (Laboury and Devillers 2022, p. 165).

This paper acknowledges that art in ancient Egypt was not solely defined by its aesthetic qualities and was often intricately linked with practical functions. Within the ancient Egyptian context, art is not necessarily concerned with personal expression or creativity. Instead, art was expected to follow visual rules and iconography to communicate messages and ideas effectively. In this sense, ancient Egyptian art may also be seen as an example of visual design. Ancient Egyptian artists had to carefully consider how form, color, and layout could produce images, monuments, and objects that serve religious and/or funerary requirements, affirm identities, promote kingship, or fulfill other societal needs (Cooney 2007, pp. 2–3). The value of an artwork, which can be defined by its effectiveness and/or its materiality, has been discussed from the perspective of the patron or the beholder, and from an economic perspective (Cooney 2007, p. 5). This paper, however, considers how artists valued their own skill level, and how they may have measured their skill against one another.

Thus, we must define what we mean by “style” and “skill” and to clarify the difference between the two, so that the terms are not conflated. According to the Oxford Dictionary, “style” is a “manner of doing something”, perhaps in order to achieve a “distinctive appearance”. “Skill”, however, is the ability to render something well, and reflects an artist’s ability to fulfill their intentions effectively. Much like our characterization of ancient Egyptian “art” or “artists”, our understanding of skill and style comes from an etic perspective. Nonetheless, these are useful terms that can explain how an artist renders and executes an idea or concept visually and materially.

Traditionally and typically, the term “ḥmw.ṯ” is normally translated as “craft”, which in the English language has a different connotation from “art”, a mutable concept influenced by context (Babcock 2022, p. 28). But also, Laboury and Devillers observe that ḥmw.ṯ has connotations related to “mastery” in contrast to something simply being “made”, which is expressed by the verb jrj (Laboury and Devillers 2022, p. 165). A ḥmw.ṯ is an image or an object composed with a care that exceeds any basic utilitarian purpose and considers aesthetics and design in the process of making (Babcock 2022, p. 30; Laboury and Devillers 2022, p. 166; Laboury 2012, pp. 374–76). One could consider themselves as a ḥmw.w or a skilled practitioner of ḥmw.ṯ in various disciplines and media, such as painting and sculpture, and sandal-making and carpentry; the latter media might not be included in the traditional canon of art history, which is still biased toward painting and sculpture (Laboury and Devillers 2022, p. 168).

The term “workshop” is also loaded or unclear because it has varying meanings related to how one defines where artists work, what materials are used, how specializations are organized, etc. (Boonstra 2020, p. 66; Connor 2018, p. 11; Kasfir and Förster 2013, pp. 1–3). For the sake of this paper, I define a royal workshop as a community of artists who are producing images and designs specifically for the king and the structures that uphold divine royal authority.

3. Deir el-Medina and Hierarchy of Labor

The information gleaned from reconstructing the hierarchies of labor dedicated to tomb decoration and construction is usually focused on economics, such as comparing the salaries and general wealth of certain people vis-à-vis others (Lesko 1994, pp. 20–25). There is also an interest in determining the kind of work certain positions entailed. For instance, we know that the two chief workmen were responsible for each side of the gang while a scribe oversaw the entire crew (Lesko 1994, p. 19). Socio-economic differences are evident among these ranks (Janssen 1975, pp. 12–19).

Because the “captains” supervised the work in the tomb, they also enjoyed a considerable amount of authority within the village and were paid higher rations than other members of the gang (Cooney 2007, p. 15; McDowell 1999, p. 5; Janssen 1997, p. 17; Janssen 1975, p. 463). However, the variety of skills exercised below the rank of “captain” or “scribe” do not seem to be ranked consistently, regardless of any prerequisite training and expertise. Because of unclear recording keeping, it is difficult to understand how “skilled” laborers, such as carpenters, sculptors, and draftsmen, were paid compared to “unskilled” stonecutters, the ones who cut the tomb into the mountainside (Janssen 1997, p. 18). There seems to be a considerable variation in wages, but a skilled artist could presumably earn extra income more easily than an unskilled laborer through “outside”, non-royal commissions (Cooney 2007, p. 14; Lesko 1994, p. 21).

Kathlyn Cooney, interested in the organization of labor in the private (non-royal) sector of the funerary goods market in Western Thebes, examined how the Deir el-Medina artists formed an “informal workshop” separate from the “royal workshop” responsible for producing art for the king (Cooney 2006, p. 49). An informal workshop was more flexible, and allowed individuals to pool their talents and function within the already existing formal hierarchical roles embedded in the royal working environment (Cooney 2006, p. 45). The basis of reconstructing how the work for private tombs was organized and functioned are the thousands of ostraca and papyri from Deir el-Medina that served as records and receipts (Cooney 2006, fn. 12–17). In these documents, the specific titles of an artist are mentioned, which correspond to the type of work that person performed. In most texts, Cooney notes that the titles that the artist used in these private documents are the same ones that he used as a member of the official work crew of the royal tombs (Cooney 2006, p. 46). Accordingly, painting and decoration is almost always done by people with the titles sš-kd, “scribe of forms”, or sš, “scribe”. Cooney explains, however, that some men with the title rmṯ-jsṯ, or “man of the crew” also sometimes painted private funerary objects or worked on carpentry tasks. Within the informal workshops, a “workman” could execute painting and carpentry, whereas in the royal tombs, a “workman” would probably be limited to the less desirable tasks that a “draftsman” could avoid (Cooney 2006, pp. 46–47).

Examining the labor organization in informal workshops shows that not all hierarchical structures are explicitly expressed within a community. I presume that there were unrecorded/unspecified hierarchical structures that existed among the title-bearing painters at Deir el-Medina. I also assume that individuals acknowledged inherited titles and seniority, but that they also informally or unofficially ranked each other based on the skill level they recognized in one another (Collier 2014, p. 6; Collier 2004, p. 19). Not every draftsman is equal, which is clear from the visual evidence that demonstrates a wide range of artistic skill (Babcock 2022, pp. 42–43).2 The hereditary nature of the workforce at Deir el-Medina means that there were individuals who learned as they worked on the royal tombs (Cooney 2012, p. 164).

4. Measuring Skill?

One might claim that it is impossible to determine if a work of art is “good” or “bad” because of the persistent assertion that art is subjective. To some extent, this is true. An artwork or artist that one person values may be detested by another, which could be because of personal preferences, but also cultural references (Pariser et al. 2007). How we determine if a work of art is skillful must be contextualized according to an artist’s intention, which is sometimes described as “style”, but which is in fact distinct from “skill”, as this paper explained earlier.

In his discussion of ancient Egyptian artistic conventions, John Baines states, “A style is a crucial vehicle of discourse and of the maintenance of a society’s identity” (Baines 2007, p. 302). For the ancient Egyptians, the royal style of a given time, which considers proportions, the quality of line, and the overall composition, is used to express the power and legitimacy of the king and his governance. For messages to be conveyed properly in visual media, style must be executed with skill and precision. Thus, though tastes for different styles may shift with time and depend on geographical location, a certain level of skill would be required to meet the standards of the reigning king, or the leaders of any royal artistic workshop. In this sense, there must have been objective, measurable artistic standards that were expected of artists working on the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens.

Presumably the works of art made for the king, or for the state in general, would be consistently of the highest quality, even when considering some disparities in regional stylistic tastes (Connor 2018, p. 16). Minor differences in the visual details of a given style serve as reminders that individual hands are responsible for royal and “official” artwork. But these individual “stylistic” differences may not necessarily be intentional, as Simon Connor demonstrated in his examination of ancient Egyptian sculpture and artistic workshops (Connor 2018, p. 14).

Another caveat to assessing an overall style is that in some cases, one may see slight variations in artistic details within the same royal monument. Vanessa Davies, for instance, observed subtle differences in the hieroglyphic signs on either side of the lintel in the Sanctuary of the Ithyphallic Amun. She recognized the different hands as those who came from the “left” and “right” sides of the workman’s crew. Specifically, she notes the treatment of the curves of the back of the pintail ducks: on the right side of the lintel, the back of the duck is much higher and has a pointed beak; meanwhile, on the left, the beak is quite flat while the back is sloping (V. Davies 2017, p. 214). While Davies describes these differences as representative of different “styles”, I think the visual disparities are too subtle to describe them as anything more than individual “signatures” or “handwritings” working within an “official” or “royal” style. Realistically, most people would not notice or measure such subtle differences, as the entire doorframe from the sanctuary uses visually consistent hieroglyphic signs overall (V. Davies 2017, Figure 9). Additionally, there are many factors that can cause artists to lack consistency and uniformity in their drawings or paintings (Bettles 2022, p. 585). In sum, we must be cautious when we label visual discrepancies as “individual styles”. Afterall, ancient Egyptian artwork is a result of a collective practice that suppressed individual styles and adaptions (Laboury 2012, p. 203; Bryan 2017, pp. 13, 18). The use of the grid, which served as a guide for proportions and consistency in two-dimensional artwork throughout most of ancient Egyptian history, is an example of this. Even when grids were not used, as is the case for Ramesside painting, figures still conformed to what was considered “ideal” or “normative” (Robins 1994, p. 259).

But among works of art and monuments made for private individuals, visual consistency and uniformity may be more lacking. Artistic skill may be more varied, since the skillfulness of a work may depend on what the patron could afford (Cooney 2007, pp. 124, 127).3

Also, the looser hierarchy evident in the informal workshops meant that some members of the Deir el-Medina “gang” would have been able to perform types of work that they would not be able to execute in the royal tombs (Cooney 2006, p. 47). This is significant, because members of the community who painted images and objects for non-royal commissions but who were not officially recognized as a sš or sš-kd, and especially not a ḥrj- sš-kd, might have a less developed painterly skillset than those who did.

One method through which one can study the variation in skill among artists working in ancient Egypt is through close visual examination, which involves the Morellian method (V. Davies 2017, p. 203).4 This technique is named after the inventor of connoisseurship, Giovanni Morelli, who used a hierarchy of anatomical details and styles to attribute Italian painting to an artist or school (Laboury 2012, p. 203). Traditionally, this method is used to gauge the stylistic variation among different European painters. Laboury has used this method in ancient Egyptian painting to identify the style of a period, group, or even individual (Laboury 2012, p. 203). Additionally, Laboury has found this method useful in determining skill and measuring the relative skill levels among a group of artists working in the same environment and attempting to conform to a uniform style.5 I consider this to be the most productive application of this technique in examining ancient Egyptian art (Laboury and Tavier 2016, p. 58; Laboury 2012, p. 205). But using this technique to measure skill only works when one understands what the desired style of a work of art is.

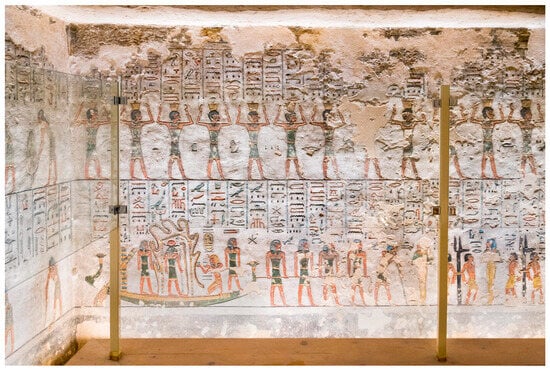

I propose that the paintings from 19th and 20th dynasty royal tombs would be the artistic standard, or models of emulation, for the Deir el-Medina artists working on their and their family’s tombs.6 Furthermore, Theban elites outside the village may have also sought artists associated with Deir el-Medina to work on their tombs because of the community’s familiarity with the royal funerary style (Cooney 2012). One characteristic to consider when assessing if a painter has successfully mastered this style is the fluid quality of a figure’s outline, which is delicate in its thinness, but which also demonstrates some calligraphic weight in certain parts of the linework. Color and how effectively color is applied may also be assessed (Hartwig 2023, pp. 96–97). In royal tombs, colors typically stay within their boundaries and there is sometimes an attempt at modeling or representing delicate textures, such as the translucency of linen (Figure 1). The spacing of the figures seems pre-planned so that no elements look too cramped or spaced too far apart (Figure 2). Proportions are also consistent, despite artists abandoning the grid system during the Ramesside period and relying more on freestyle drawing. One’s ability to freehand draw consistent proportions and repeat common compositional layouts would have been a result of continuous practice, likely performed on many of the figured, or illustrated, ostraca believed to be from Deir el-Medina (Cooney 2012, p. 161).

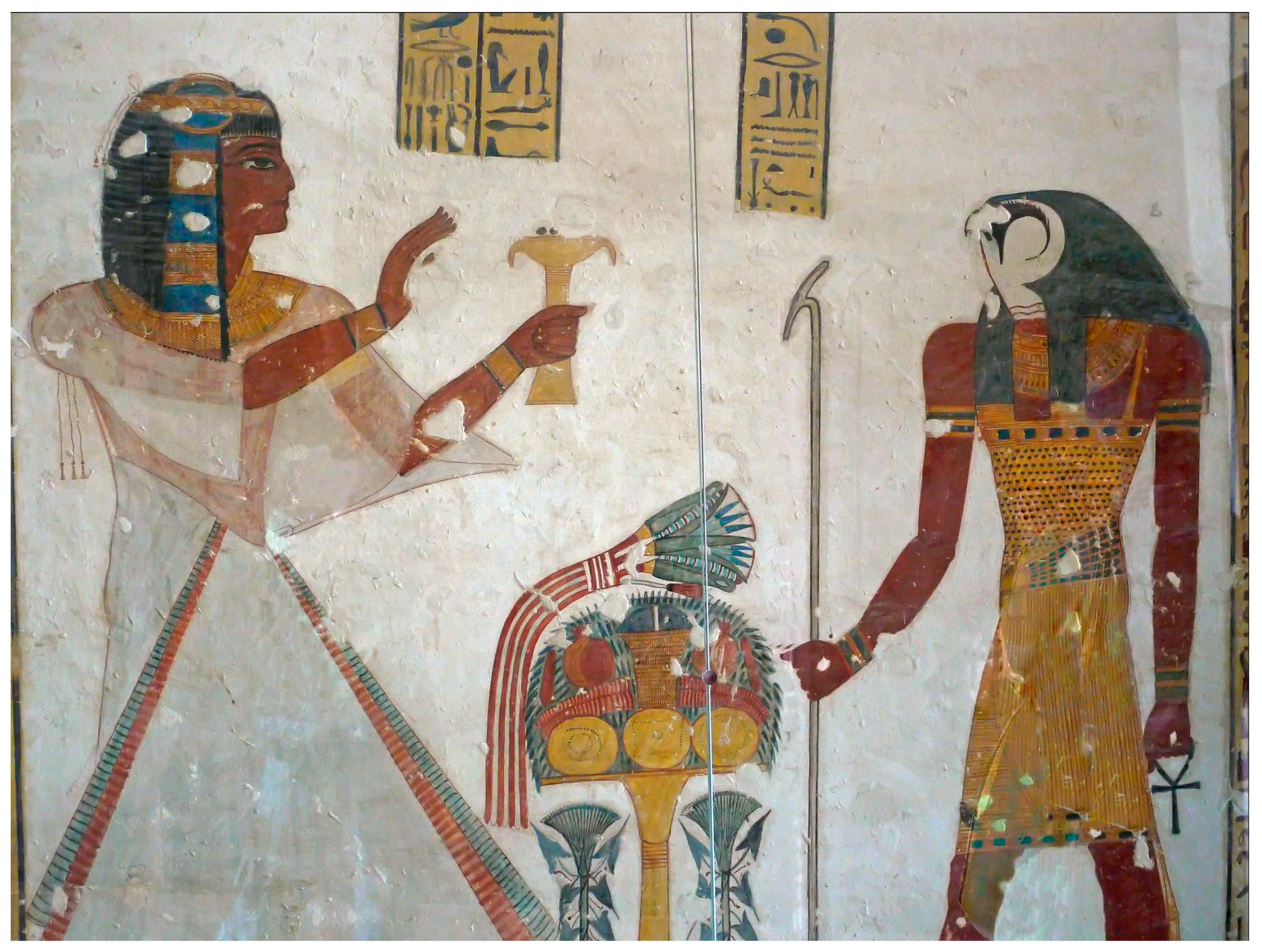

Figure 1.

KV 10 Montuherkhepeshef, Valley of the Kings, Thebes, Luxor. kairoinfo4u, <flickr.com/photos/manna4u/3331551796/in/album-72157614772189273/> accessed on 12 March 2024.

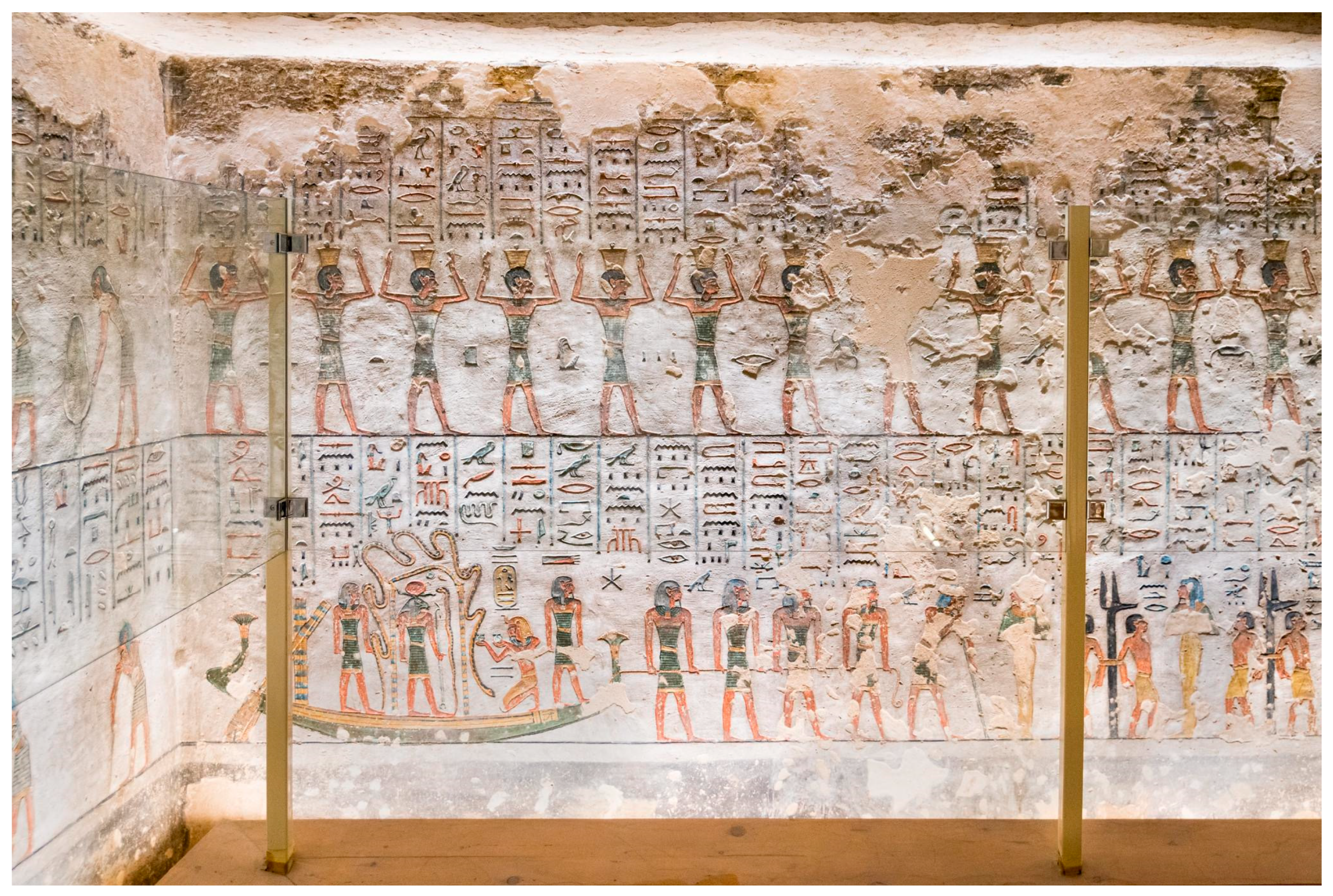

Figure 2.

Tomb of Ramses III, KV 11, Side chamber Fa. kairoinfo4u, <flickr.com/photos/manna4u/50845547111/in/dateposted/> accessed on 12 March 2024.

Bengt Peterson was able to use the provenanced examples of figured ostraca to show that higher quality drawings were localized in the Valley of the Kings, where the painters worked. Meanwhile, Deir el-Medina, whose population included the young, inexperienced family members who would one day inherit the artistic roles of their forebearers, yielded figured ostraca that demonstrated a much broader range of skills (Peterson 1974, p. 23).

One set of ostraca, which include images of anthropomorphized animals, are unprovenanced but presumed to be from Deir el-Medina because of their material and the high quality of some of the images. The higher quality illustrations of these human-like creatures were probably drawn by artists who painted the royal tombs (Babcock 2022, p. 43, Cat. 11). But the others are lacking in skill, and feature shaky linework that is consistent with someone unaccustomed to their materials (Babcock 2022, pp. 43–44, Cat. 14). The less talented artists may attempt to correct their drawings, and do not paint with the fluid, calligraphic strokes that are characteristic of a skilled hand. Sometimes, among the poorer quality ostraca drawings, the proportions of the figures are incongruent with what one finds in royal funerary Ramesside painting. The arrangement of the figures may also be cramped or overlap clumsily. The variation in the quality of this group of ostraca may be because they are examples of popular and personal piety that is well attested at Deir el-Medina (Luiselli 2018, pp. 207–9). Likely, they are religious offerings that could have been made by anyone in the community, whether they were official painters or not (Babcock 2022, pp. 98–99).

The uses of the figured ostraca from Deir el-Medina and its adjacent areas are varied. They can serve as votives, be used as surfaces for practice sketches, and be tools for apprenticeship. The latter, the “teaching” ostraca, include drawings that have instructor corrections or images in which a teacher has created a model drawing for an aspiring artist to copy (Keller 1993, p. 51). Cooney has argued that many of these ostraca demonstrate “informal” training, where artists learn through emulation and repetition. The process was one of constant skill building between familial generations (Cooney 2012, p. 164). Some figured ostraca also include images that seem more “complete” because they include polychromatic coloring, for instance. But “completeness” is relative and depends on the purpose of the figured ostracon. In the case of “teaching” ostraca, uncolored pieces may not necessarily be “incomplete” if their primary use was to teach royal iconography or basic brush and pen skills. Thus, the appearance of “teaching” ostraca will vary depending on the “lesson” and the needs of the one learning.

Another way to appreciate the spectrum of artistic skill and value at Deir el-Medina is to examine the tombs that were built and designed by the workmen adjacent to the settlement. Inherkhau’s (ii) tomb at Deir el-Medina is particularly interesting because it offers a clear identification of two of its artists, Hormin (i) and Nebnefer (ix), whose names and titles are written throughout the tomb chapel.7 Coincidentally, these artists were brothers who shared the same title, sš-kd (Cherpion and Corteggiani 2010, p. 24; Keller 2001, p. 73). While their familial relationship and the textual inscriptions indicate that they were equals, the artistic output of these two men could suggest that there was a slight difference in how they were viewed by the community of painters.

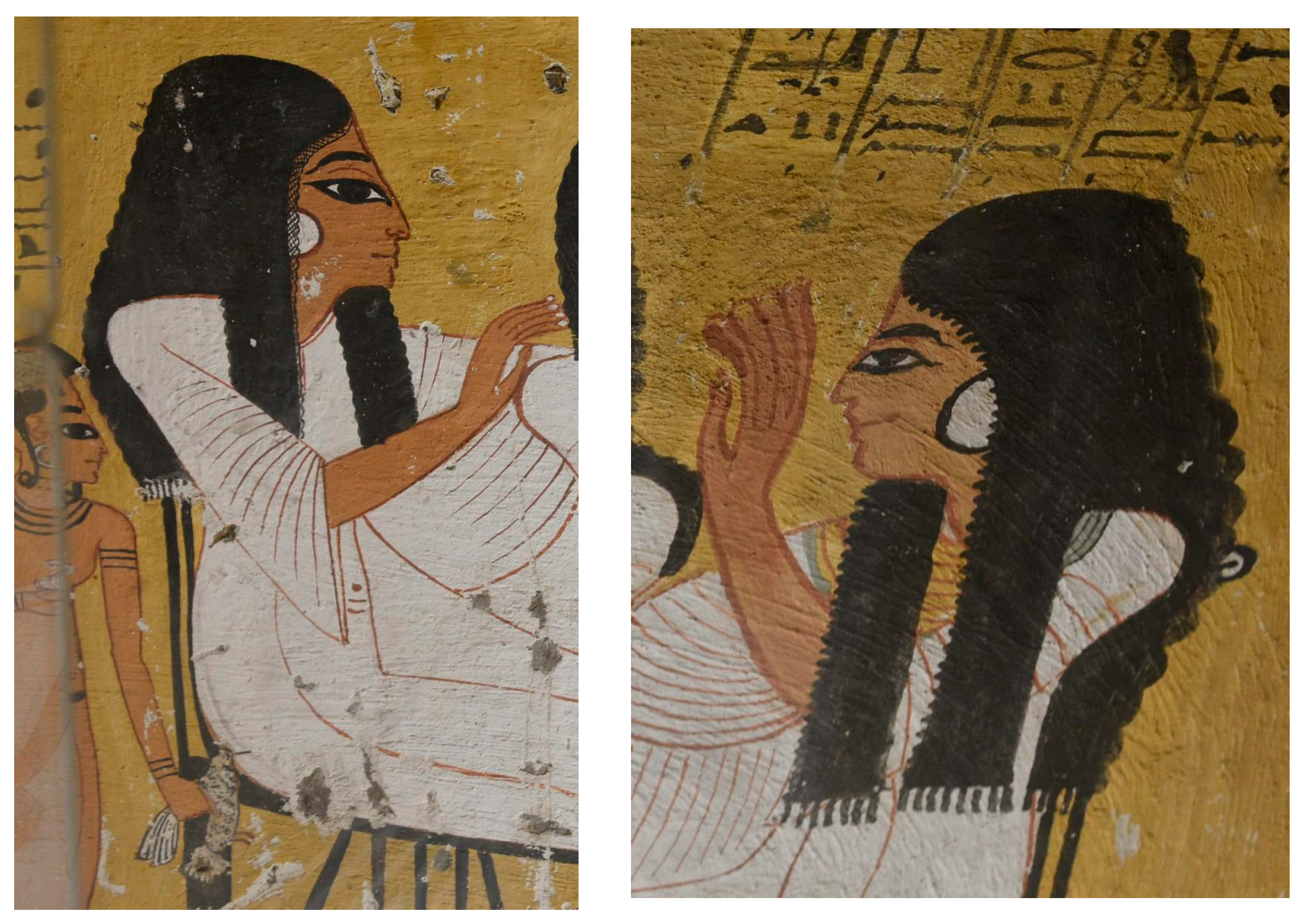

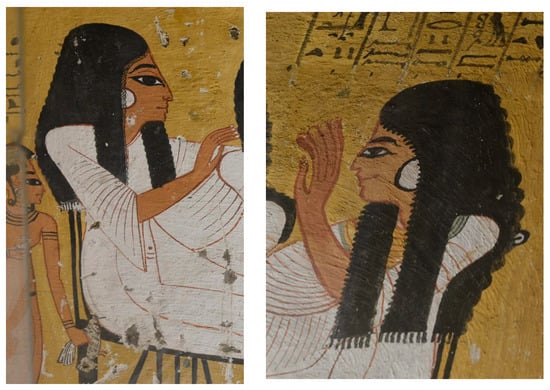

Although they both conform to a single style, Nadine Cherpion, Jean-Pierre Coreggiani, and Cathleen Keller describe Hormin (i) as being the more talented of the two. This assessment is supported when one compares the quality of Hormin’s (i) visual motifs to his brother’s (Cherpion and Corteggiani 2010, pp. 113, 158; Keller 2001, p. 80).8 Hormin’s (i) linework is clear and consistent whereas Nebnefer’s (ix) linework is less confident in that it demonstrates inconsistencies in its thickness (Figure 3). His superior painting abilities are evident even when, or perhaps because of, the ways he deviates from the traditional iconography and style that is typical of contemporaneous royal painting. But overall, when we compare Nebnefer’s (ix) and Hormin’s (i) paintings to the royal funerary style seen in the tombs of Ramesses III (KV 11) and IV (KV2), which were decorated around the same time as Inherkhau’s (ii) tomb, we see that Hormin (i) is better equipped to skillfully emulate the royal painting style found in the nearby Valley of the Kings.

Figure 3.

A comparison of Hormin’s (i) painting skills (left) with Nebnefer’s (ix) (right). Richard Mortel. <https://tinyurl.com/srw6mkfb/> and <https://tinyurl.com/msd9nhws/> accessed on 12 March 2024.

Despite their differences in skill, Hormin (i) and Nebnefer (ix) worked together on the same walls in Inherkhau’s (ii) tomb. There does not seem to be any indication that one artist was given special treatment in the types of motifs they could design and paint. Rather, it appears that Hormin (i) and Nebnefer (ix) shared the work equally (Keller 2001, p. 87, Figure 12) and were likely seen as equals in this non-royal context.

Indeed, these artists were apparently professional equals; they both had the same title and worked on the left side of the Deir el-Medina gang under the same chief workman. But I do not believe that they were necessarily treated as equals in the royal tombs. Nebnefer (ix) had not mastered painting on the same level as his brother, and despite being older (Keller 2001, p. 78), I wonder if Hormin (i) was given more desirable painting assignments in the royal tombs. Afterall, studies indicate that more talented artists were given more important tasks (Laboury 2020, p. 94; Bryan 2017, p. 19; Hartwig 2013, p. 160; Bryan 2010, pp. 1003–4). In the context of the royal workshop, there was likely an unofficial hierarchical ranking that provided Nebnefer (ix) with greater standing than his brother, despite being his equal “on paper”. In this case study, we see that studying the images may provide us with a better glimpse of the unrecorded competition that may have existed among the painters of the royal tombs.

5. Understanding Artistic Training and Workshops at Deir el-Medina through Comparisons to European Traditions

Other notable tombs that feature identifiable artists responsible for their decoration are TT 65 and TT 113, which were painted by the chief painter of Deir el-Medina, Amenhotep (iv), son of Amennakht (v) (Laboury 2023, p. 118; Keller 2003, pp. 95–96; Bács and Parkinson 2011). Amenhotep (iv) was a particularly skilled painter, especially when compared to some of his contemporaries in pre-Ramesside Deir el-Medina (Laboury 2012, pp. 119–25); this led Laboury to describe Amenhotep (iv) as “the kind of artist the Renaissance have designated a pictor doctus”, or an educated painter who would be able to imagine new compositions adeptly for his patrons (Laboury 2023, p. 119; Laboury 2016, p. 389). In this comment, Laboury draws a parallel between the highest skilled ancient Egyptian painters and the concept of a European “master painter” of the Medieval and Renaissance ages, a recurring theme in his scholarship (Laboury and Devillers 2022, p. 173; Laboury 2016, fn. 27; Laboury 2015).

Laboury’s identification of certain ancient Egyptian artists as “masters” moves beyond acknowledging that they are skilled in their craft, because the term also implies that these “master painters” had apprentices or underlings. This understanding of how artistic labor was organized was also made earlier by Norman de Garis Davies, who noted collaborative work between a “master” and an “apprentice” in the painted decoration of two New Kingdom tombs (De Garis Davies 1923, p. 3). Drawing boards and figured ostraca are cited as additional evidence that the master–apprenticeship system was being used in ancient Egypt to train young scribes, and aspiring craftsmen and artists (Laboury 2016, p. 384; Lazardis 2010, pp. 7–8; Galán 2007, pp. 103–4).

But Cooney rightfully cautions us to not immediately apply a European master–apprenticeship model to Deir el-Medina, and perhaps also to ancient Egypt more broadly. She argues that there was likely spontaneous, informal sketching that allowed the artists at Deir el-Medina to learn, practice their craft, and to experiment with new artistic forms. Such “communities of practice” involved the artists who were decorating the royal tombs, as well as any offspring of these artists whose goal or destiny would be to also work in the royal tombs one day. Thus, there was not necessarily a strict master–pupil relationship within the Deir el-Medina community like that found in the workshops of Medieval and Renaissance Europe (Cooney 2012, p. 166).

During the European Renaissance, workshop masters were admired for their individual style (Baxandall 1972, p. 26). Accordingly, not every Italian Renaissance master artist would insist that their students learn to paint or sculpt in their specific “manner” (Brooks 2015, p. 4). Rather than teach consistency in style, master artists in Renaissance Europe sometimes encouraged apprentices to explore their own “manner” or style of painting (Brooks 2015, p. 4). Renaissance artists were concerned with humanism, and a sense of individualism that was surely different from the ancient Egyptian sense of personhood and individuality.9 This is not to deny, however, that originality and individual creativity existed in ancient Egypt. As we have seen in this study, painters sometimes signed their work and incorporated unique motifs and details into their art (Sainz 2016, p. 212).

Another major difference between the workshop models of Renaissance Europe and of Ramesside Deir el-Medina is the sense of ownership. During the European Renaissance, families could claim ownership of a workshop, which could be passed down through generations (Maze 2013, p. 787). However, while an ancient Egyptian artist may have inherited a position or title within a royal workshop, they did not necessarily inherit its community of laborers and artists. The formal, royal workshop in ancient Egypt was in the service of the king and royal power, and not an institution aligned with an individual or family.

The Italian Renaissance was shaped by neoplatonic and humanist ideas, which stemmed from a fascination with Classical Greek culture. So even when useful insights are gleaned from making these cultural parallels, the approach may perpetuate Euro-centric perspectives or emphasize Egypt’s role in the history of “the Western tradition”. Thus, I have been actively studying cross-cultural comparisons to other “non-Western” and, specifically, African cultures. While the parallels to the African kingdom of Benin are not one to one, or always relevant, the comparisons nonetheless provide an additional and useful lens through which to understand ancient Egyptian art making. Using Benin as a point of comparison is also an attempt to further decenter European perspectives in studying ancient Egyptian art and its makers.

6. Understanding Artistic Training and Workshops at Deir el-Medina through Comparisons to the Royal Workshops of Benin

Like ancient Egypt, the kingdom of Benin in modern-day Nigeria is structured in a rigid hierarchy, and the king, or oba, has divine origins, granting him absolute rule over his people (Igbafe 2007, p. 41). Royal guilds and workshops are established with the purpose of creating royal and ceremonial images.10 Membership of Benin’s guilds, much like the titles attested in Deir el-Medina’s community of laborers and artists, is hereditary (Plankensteiner 2010, p. 39). The Ineh n’Igun Eronmwon, the head of the bronze-casters of Benin, leads the entire guild and ensures that the oba’s commissions are completed. The royal guilds in Benin are still active today and have been functioning almost continuously for centuries (Gunsch 2018, p. 106).

During Benin’s pre-colonial times, the palace chiefs of the king were part of the seven Uzama Nihinron, or kingmakers. One of their responsibilities was to oversee the professional bodies assigned to palace organizations, such as the artists who worked in the royal guilds. Within these guilds were the bronze-casters, ivory and woodcarvers, weavers, bead-workers, ironsmiths, and leather workers (Plankensteiner 2010, p. 40). Of these groups, the bronze-casters enjoyed the highest rank and prestige, with the ivory-makers following close behind, making objects that were often restricted to private areas of the palace that were inaccessible to the public (Plankensteiner 2010, p. 40).

One primary difference between the community of bronze-casters in Benin and the painters at Deir el-Medina is that Benin’s bronze-caster population seems to have been more closed (Odiahi 2017, p. 180). While painters may have been brought from outside Deir el-Medina, depending on what needed to be accomplished at the royal tombs (B. Davies 2017; Collier 2014), it is incredibly rare for an “outsider” to be accepted into the bronze guild of the oba. Furthermore, while painters and craftsmen in Deir el-Medina were free to work on private commissions, it was not until the late 19th century that bronze-casters in Benin could work for non-royal patrons (Gunsch 2018, p. 106; Odiahi 2017, p. 184). Another notable difference between the two communities is their physical proximity to the king. While Deir el-Medina’s painters were distant from the royal residence, and not the only painters fulfilling royal commissions in Egypt, the bronze-casting guild in Benin was centralized within the palace (Gunsch 2018, p. 106).

Nonetheless, the hereditary nature of the artistic positions within Deir el-Medina and Benin’s royal bronze workshop is a strong connection that these two artistic traditions share. Understanding why this role is inherited may give us a glimpse into how artistic talent, skill, and creativity was understood in ancient Egypt. Benin mythology states that the art of bronze casting is a divine gift. Within Beninese mythology, “the first” bronze-caster, Igueghae, did not learn the artform from anywhere but was instead born with it (Odiahi 2017, p. 179).11

There are no texts, to my knowledge, that explicitly state that the ancient Egyptians believed their artists were divinely inspired. But an argument can be made that those ancient Egyptian artists who created images and objects that functioned to ensure the maintenance of royal, divine, and social order considered themselves to be more important, or “special”, than those who did not.

Laboury has noted that certain texts indicate that artists, particularly painters, would liken themselves to the elite scribal profession to garner more respect and social currency (Laboury 2016). Scribes were not only respected for their education, but also, I would argue, for their close relationship with the divine. As people who were able to read and write in a language given by the gods and created words and images that harnessed power (Wilkinson 1992, pp. 9–10), it is hard to imagine that they would not see themselves and their familial line as being “touched” by the gods. Niv Allon’s study of a statue of a scribe being supported by the god Thoth in the form of a baboon supports the idea that scribes may have thought of themselves as divinely guided and inspired (Allon 2013, p. 99). Painters and draftsmen who sought to align themselves with the scribal tradition may have felt similarly. But of course, no one, even if they are given divine artist gifts, can produce skillful works of art that conform to specific, royal standards, without practice and experience.

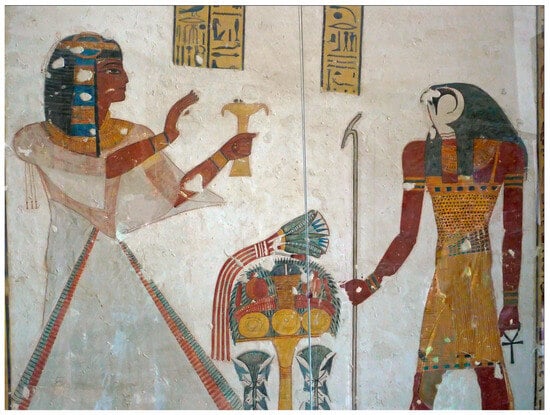

Gunsch’s art historical analysis of the workshop markings and stylistic changes of the bronze-casters guild of Benin indicate that apprentices and junior members would have worked alongside the more experienced artists (Gunsch 2018, pp. 108–10). There is not a strict master–pupil relationship as there was in the Italian Renaissance workshops, since members within the guild teach each other. Junior members would have been responsible for the smallest elements of decoration and the preparation of the bronze molds, while more skillful artists would work on the primary figures of each plaque (Figure 4). Even today, people within the bronze guild are grouped according to a perceived level of skill or experience (Odiahi 2017, p. 181). Similarly, I suspect that the artists at Deir el-Medina were informally grouped according to skill level, which would dictate what artistic responsibilities they had in decorating the royal tombs.

Figure 4.

Snake plaque, Edo peoples, from Court of Benin, Nigeria, Bronze, 16th–17th century. MMA 1979.206.96.

7. Conclusions and Future Inquiries

Just as Gunsch proposed that the junior members of the bronze guild produced the small background details of the bronze plaques for the Benin court, the less experienced painters from Deir el-Medina would be responsible for the minor figures and simpler, repetitive patterns found in the royal tombs. For instance, the five-armed star patterns found on the ceilings of many New Kingdom royal tombs are undemanding and easy to replicate. The fact that these paintings are on the ceiling would also make it more difficult for one to scrutinize them from the ground.12 It is likely that experienced artists would have supervised junior artists in painting simple ceiling designs or allowed them to paint without supervision (Bács 2023, p. 13).

A painter could train their hand with simple designs until they were ready for more complicated patterns and motifs, and figures. A “scribe of forms”, (sš-kd) and perhaps even someone close to being promoted to that rank would have created the red line drawings that would eventually be painted over with bold, black outlines. The final black linework would have been executed by the most skilled and experienced painters, such as the higher ranking “chief of scribe of forms” (jrj sš-kd) (Bryan 2017, p. 19; Hartwig 2013, p. 160; Bryan 2010, pp. 1003–4; Bogoslovsky 1980, p. 93). One imagines that there was inherent and encouraged competition among the artists to move up the ranks or to be assigned more important details and steps in the tomb’s decoration.

The overall consistency in the artistic skill evidenced in ancient Egyptian royal imagery was achieved through official and unofficial hierarchies of labor and rankings within the artistic community. Young painters in Deir el-Medina’s Ramesside community, destined to work in the royal tombs because of their birthright, would be trained in their craft through informal apprenticeship at a young age. For large-scale royal projects, training was likely provided by painters other than the “chief of scribe of forms”. I believe that the painters from each side of the gang determined who taught whom based on their assessment of the skill and experience levels that they observed in the group. This structure would resemble the instructional methods of the Benin bronze-casting workshop.

Some painters excelled in their medium more than others, which might be reflected in promotions and title differences. But as seen in the case of Hormin (i) and Nebnefer (ix), there could still be some variability in skill among professional equals. The skillfulness of one’s hand at reproducing the royal funerary style and one’s understanding of iconography and spatial layout were surely acknowledged, assessed, and used as hierarchical markers even on a “casual” or unofficial level.

An interesting avenue for art historically minded Egyptologists to explore more deeply is the current and past practices of the Beninese royal artist workshops and guilds. In ancient Egypt, and in Benin, one purpose of art is to serve as a means of effectively conveying messages about divine royal identity; it is thus a reflection of prestige. However, this prestige is not only limited to the final product, the patron, or audience; it is also intricately woven into the collaborative and hierarchical processes of artistic creation. Examining how skill is valued within the hierarchical structure of Benin’s bronze-working guild in the past and today might provide valuable insights into similar dynamics in ancient Egypt’s workshops, including the one at Deir el-Medina. Furthermore, Benin could provide insight into the status of artists and makers who are not seen as individual geniuses but as part of a divinely inspired collective whose mission is to serve royal authority and divinity. This perspective contrasts with European traditions that often emphasize individual creativity over communal contributions. Of course, exploring other non-European artistic workshops that are dedicated to divine kingship would also be fruitful and bring fresh art historical perspectives to Egyptology.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers of this article for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | There are also workers in the village who were unrelated to the decoration of the tomb, but which helped keep the village functional (Gabler 2018; Janssen 1997). |

| 2 | This is true within the scribal tradition at Deir el-Medina as well. Sennefer, despite claiming himself to be “the son who writes correctly, who has made his name (=of his father) alive” made many linguistic mistakes (Sartori 2023, p. 661; (Van Heel and Haring 2003, p. 4). Also, Qenhirkhopshef (i), despite his experience, is notorious for his poor writing skills (Van Heel and Haring 2003, p. 4.). |

| 3 | Studies of the cost of illustrated Books of the Dead indicate costs fluctuated. One parameter that effected the price of an illustrated papyrus was the skillfulness of an image’s draftsmanship (Babcock 2022, p. 35; Cooney 2007, p. 91). |

| 4 | Davies, however, problematizes the ability of how one can determine individual style through her examination of hieroglyphic signs carved at Medinet Habu (V. Davies 2017, pp. 206–7). |

| 5 | Related to this is the idea of a uniform cultural style. The idea of a uniform cultural style was explored thoroughly in the European tradition with Baxandall’s theory of the “Period Eye” (Baxandall 1972, pp. 29–108). |

| 6 | Keller has noted that the burial chambers of the Deir el-Medina tombs are clearly linked iconographically to the royal tomb. Like me, Keller characterizes the royal tomb painting style as defining an overall “royal style” (Keller 1993, pp. 60, 62). |

| 7 | Inherkhau’s (ii) tomb is also interesting because it includes patterns and details that are unusual or unique (Cherpion and Corteggiani 2010, pp. 40–41, 115, 120–21, Pl. 23, Pl. 47). |

| 8 | Hormin’s (i) greater talent or at least experience may also be evident in that he is much more creative in his compositions. Throughout Inherkhau’s (ii) tomb, Hormin (i) experiments with design and includes unique details, such as his interpretation of the Great Tomcat (Babcock, forthcoming). |

| 9 | For instance, see Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, a 16th century body of work that compiles a series of artist biographies. For ancient Egyptian perspectives on identity see (Laboury 2010, p. 4; Assmann 1996, p. 81). |

| 10 | Such as the ivory tusks found at the royal altars in Benin. See (Blackmun 1987, p. 82; Blackmun 1984, p. 26). |

| 11 | There is also a debate as to whether bronze-casting originally came from Benin or Ife (Odiahi 2017, p. 179). |

| 12 | Not all ceiling patterns are simple. The astronomical ceiling in KV17 requires mastery of form. Also, some repetitious patterns are more challenging to emulate, which is evidenced in TT 354. The unbalanced and irregular ceiling design indicates some ignorance about how to paint this pattern effectively (Laboury 2023, p. 125). |

References

- Allon, Niv. 2013. The Writing Hand and the Seated Baboon: Tension and Balance in Statue MMA 29.2.16. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 49: 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Andreu-Lanoë, Guillemette. 2022. ‘Workmen’, ‘Craftsmen’, ‘Artists’? Unknown archives helping to name the men of the community of Deir el-Medina. In Deir el-Medina: Through the Kaleidoscope, Proceedings of the International Workshop, Turin, Italy, 8–10 October 2018. Edited by Federico Poole, Paolo Del Vesco and Susanne Töpfer. Modena: Franco Cosimo Painini Editore, pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, Jan. 1996. Preservation and Presentation of Self in Ancient Egypt. In Studies in Honor of William Kelly Simpson 1. Edited by Peter der Manuelien. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, pp. 55–81. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock, Jennifer Miyuki. 2022. Understanding Ancient Egyptian Aesthetics. In Ancient Egyptian Animal Fables: Tree Climbing Hippos and Ennobled Mice. CHAN 128. Leiden: Brill, pp. 28–54. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock, Jennifer Miyuki. forthcoming. A Feline-Hare from Deir el-Medina. Soule le Ciel Étoile Proscynème cordial au Dr. Nadine Guilhou-Ambroise. Journal of the Hellenic Institute of Egyptology.

- Bács, Tamás. 2023. Tomb Painting in an Age of Decline. In Occasional Proceedings of the Theban Workshop. Mural Decoration in the Theban Necropolis. Edited by Betsy M. Bryan and Peter F. Dorman. Studies in Ancient Cultures 2. Chicago: Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures of the University of Chicago, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bács, Tamás, and Richard Parkinson. 2011. Wall Paintings from the Tomb of Kyneby at Luxor. Egyptian Archaeology 39: 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, John. 2007. On the Status and Purposes of Ancient Egyptian Art. In Visual and Written Culture in Ancient Egypt. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 298–337. [Google Scholar]

- Baines, John. 2015. What is Art? In A Companion to Ancient Egyptian Art. Edited by Melinda K. Hartwig. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Baxandall, Michael. 1972. The Period Eye. In Painting and Experience in 15th Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 29–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bettles, Elizabeth. 2022. Digitally distinguishing ‘hands’ that painted hieroglyphs in tombs at Deir el-Medina. In Deir el-Medina: Through the Kaleidoscope. Proceedings of the International Workshop, Turin, Italy, 8–10 October 2018. Edited by Federico Poole, Paolo Del Vesco and Susanne Töpfer. Modena: Franco Cosimo Painini Editore, pp. 578–98. [Google Scholar]

- Blackmun, Barbara W. 1984. Art as Statecraft: A King’s Justification in Ivory. A Carved Tusk from Benin. Geneva: Musée Barbier-Müller. [Google Scholar]

- Blackmun, Barbara W. 1987. Royal and nonroyal Benin: Distinctions in Igbesanmwan Ivory Carving. Iowa Studies in African Art 2: 81–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bogoslovsky, Evgent S. 1980. Hundred Egyptian Draughtsmen. Zeitschrift fûr Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 107: 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, Stephanie. 2020. Finding Scarab Amulet Workshops in Ancient Egypt and Beyond: ‘Typological’ vs. ‘Material’ Workshops. In Approaches to the Analysis of Production Activity at Archaeological Sites. Edited by Anna K. Hodgkinson and Cecilie Lelek Tvetmarken. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 65–83. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, Douglas J., and Emily Teeter. 1999. Egypt and the Egyptians. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, Julian. 2015. Introduction. In Andrea del Sarto: The Renaissance Workshop in Action. Edited by Julian Brooks, Desnie Allen and Xavier F. Salomon. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bruyère, Bernard. 1926. Rapport sur les fouilles de Deir el-Medineh. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, vol. 3, No. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, Betsy. 2010. Pharaonic Painting through the New Kingdom. In A Companion to Ancient Egypt. Edited by Alan B. Lloyd. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 990–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, Betsy. 2017. Art-Making in Texts and Contexts. In Illuminating Osiris: Egyptological Studies in Honor of Mark Smith. Edited by Richard Jasnow and Ghislaine Widmer. Material and Visual Culture of Ancient Egypt 2. Columbus: Lockwood Press, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cherpion, Nadine, and Jean-Pierre Corteggiani. 2010. La tombe d’Inherkhâouy (TT 359) à Deir el-Medina. MIFAO 128. Cario: Institut Français d’archéologie orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, Mark. 2004. Dating Late XIXth Dynasty Ostraca. Egyptologische Uitgaven 18. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut Voor Het Nabije Oosten. [Google Scholar]

- Collier, Mark. 2014. The Right Side of the Gang in Years 1 to 2 of Ramesses IV. In The Workman’s Progress: Studies in the Village of Deir el-Medina and Other Documents from Western Thebes in Honour of Rob Demarée. Edited by B. J. J. Haring, O. E. Kaper and R. van Walsem. Leiden and Leuven: Nederlands Instituut Voor Het Nabije Oosten and Peeters, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, Simon. 2018. Sculpture Workshops: Who, Where and For Whom? In The Arts of Making in Ancient Egypt: Voices, Images, and Objects of Material Producers 2000–1550 BC. Edited by Gianluca Miniaci, Juan Carlos Moreno García, Stephen Quirke and Andréas Stauder. Leiden: Sidestone Press, pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cooney, Kathlyn M. 2006. An Informal Workshop: Textual Evidence for Private Funerary Art Production in the Ramesside Period. In Living and Writing in Deir el-Medina: Socio-Historical Embodiment of Deir el-Medine Texts. Edited by Andreas Dorn and Tobias Hofmann. Basel: Schwabe Verlag, pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cooney, Kathlyn M. 2007. The Cost of Death: The Social and Economic Value of Ancient Egyptian Funerary Art in the Ramesside Period. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. [Google Scholar]

- Cooney, Kathlyn M. 2012. Apprenticeship and Figured Ostraca from the Ancient Egyptian Village of Deir el-Medina. In Archaeology and Apprenticeship: Body Knowledge, Identity, and Communities of Practice. Edited by Willeke Wendrich. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, pp. 145–70. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Benedict. 1999. Who’s Who at Deir el-Medina: A Prospographic Study of the Royal Workmen’s Community. Egyptolosiche Uitgaven XIII. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut Voor Het Nabije Oosten. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Benedict. 2017. Variations in the Size of the Deir el-Medina Workforce. In The Cultural Manifestations of Religious Experience. Studies in Honour of Boyce G. Ockinga. Edited by Camilla Di Biase-Dyson and Leonie Donovan. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, pp. 205–12. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Vanessa. 2017. Complications in the stylistic analysis of Egyptian Art: A look at the Small Temple of Medinet Habu. In (Re)productive Traditions in Ancient Egypt, Proceedings of the Conference Held at the University of Liège, Liège, Belgium, 6–8 February 2013. Edited by Todd Gillen. Liège: Presses Universitaires de Lièges, pp. 203–27. [Google Scholar]

- De Garis Davies, Norman. 1923. The Tomb of Two Officials of Tuthmosis the Fourth (Nos. 75 and 90). London: Egypt Exploration Society. [Google Scholar]

- Gabler, Kathrin. 2018. Who’s Who around Deir el-Medina. Untersuchungen zur Organisation, Prosopographie und Entwicklung des Versorgungspersonals für die Arbeitersiedlung und das Tal der Könige. Egyptolosiche Uitgaven XXXI. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut Voor Het Nabije Oosten. [Google Scholar]

- Galán, José M. 2007. An Apprentice’s Board from Dra Abu el-Naga. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 93: 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobeil, Cédric. 2018. L’histoire des fouilles de l’IFAO à Deir el-Medina. In À L’Œuvre On Connaît l’Artisan… de Pharaon!: Une siècle de recherches françaises à Deir el-Medina (1917–2017)I. Edited by Hanane Gaber, Laure Bazin Rizzo and Fréderic Servajean. Milan: SilvanaEditoriale, pp. 315–24. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1961. Art and Culture: Critical Essays. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gunsch, Kathryn Wysocki. 2018. The Benin Plaques: A 16th Century Imperial Monument. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Haring, Ben J. J. 2022. Late Twentieth Dynasty Ostraca. In Deir el-Medina: Through the Kaleidoscope. Proceedings of the International Workshop, Turin, Italy, 8–10 October 2018. Edited by Federico Poole, Paolo Del Vesco and Susanne Töpfer. Modena: Franco Cosimo Painini Editore, pp. 44–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig, Melinda, ed. 2013. The Tomb Chapel of Menna (TT 69): The Art, Culture, and Science of Painting in an Egyptian Tomb. ARCE Conservation Series 5; Cairo: The American University of Cairo Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hartwig, Melinda. 2023. Scribal Captions and Paintings in the Tomb Chapel of Neferrenpet (TT 43). In Occaisional Proceedings of the Theban Workshop. Mural Decorations in the Theban Necropolis. Studies in Ancient Cultures 2. Edited by Betsy M. Bryan and Peter F. Dorman. Chicago: The University of Chicago, pp. 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Igbafe, Philip Aigbana. 2007. A History of The Benin Kingdom: An Overview. In Benin Kings and Rituals: Court Arts from Nigeria. Edited by Barbara Plankensteiner. Gent: Snoeck, pp. 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, Jac. J. 1975. Commodity Prices from the Ramessid Period: An Economic Study of the Village of Necropolis Workmen at Thebes. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, Jac. J. 1997. Village Varia: Ten Studies on the History and Administration of Deir el-Medina. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut Voor Het Nabije Oosten. [Google Scholar]

- Kasfir, Sideny Littlefield, and Till Förster. 2013. African Art and Agency in the Workshop. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, Cathleen A. 1993. Royal Painters: Deir el-Medina in Dynasty XIX. In Fragments of a Shattered Visage: The Proceedings of the International Symposium on Ramesses the Great. Edited by Edward Bleiberg, Rita Freed and William Murnane. Memphis: Memphis State University, pp. 50–67. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, Cathleen A. 2001. A family affair: The decoration of Theban Tomb 359. In Colour and Painting in Ancient Egypt. Edited by W. Vivian Davies. London: British Museum Press, pp. 73–93. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, Cathleen A. 2003. Un artiste égyptien à l’oeuvre: Le dessinateur en chef Amenhotep. In Deir el-Médineh et la Vallée des Rois: La vie en Égypte au temps des pharaons du Nouvel Empire. Actes du colloque organisé par le musée du Louvre les 3 e 4 mai 2002. Edited by Guillemette Andreu. Paris: Khéops/Musée du Louvre, pp. 83–114. [Google Scholar]

- Laboury, Dimitri. 2010. Portrait versus Ideal Image. In UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Edited by Elizabeth Frood and Willeke Wendrich. Los Angeles: UCLA Library. Available online: http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz0025jjv0 (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Laboury, Dimitri. 2012. Tracking Ancient Egyptian Artists, A Problem of Methodology. In Art and Society. Ancient and Modern Contexts of Egyptian Art, Proceedings of the International Conference Held at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, Hungary, 13–15 May 2010. Edited by Katalin Anna Kóthay. Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts, pp. 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Laboury, Dimitri. 2015. The Master Painter of the Tomb of Amenhotep Sisi, Second Priest of Amun under the Reign of Thutmose IV (TT 75). In Joyful in Thebes: Egyptological Studies in Honor of Betsy M. Bryan. Edited by Richard Jasnow and Kathlyn M. Cooney. Atlanta: Lockwood Press, pp. 327–38. [Google Scholar]

- Laboury, Dimitri. 2016. Le scribe et le peintre: À propos d’un scribe qui ne voulais pas être pris pour un peintre. In Aere Perennius: Mélanges égyptologiques en l’honneur de Pascal Vernus. Edited by Philippe Collombert, Dominique Lefèfre, Stéphane Polis and Jean Winand. Leuven, Paris and Brisol: Peeters, pp. 371–96. [Google Scholar]

- Laboury, Dimitri. 2020. Designers and Makers of Ancient Egyptian Monumental Epigraphy. In The Oxford Handbook of Egyptian Epigraphy. Edited by Vanessa Davies and Dimitri Laboury. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 85–101. [Google Scholar]

- Laboury, Dimitri. 2023. On the Alleged Involvement of the Deir el-Medina Crew in the Making of Elite Tombs in the Theban Necropolis During the Eighteenth Dynasty: A Reassessment. In Mural Decorations of the Theban Necropolis: Papers from the Theban Workshop 2016. Edited by Betsy M. Bryan and Peter F. Dorman. Studies in Ancient Cultures 2. Chicago: Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures of the University of Chicago, pp. 115–37. [Google Scholar]

- Laboury, Dimitri, and Alisée Devillers. 2022. The Ancient Egyptian Artists: A Non-Existing Category? In Ancient Egyptian Society. London: Routledge, pp. 163–81. [Google Scholar]

- Laboury, Dimitri, and Hugues Tavier. 2016. In Search of Painters in the Theban Necropolis of the 18th Dynasty: Prolegomena to an analysis of pictorial practices in the tomb of Amenenope (TT 29). In Artists and Colour in Ancient Egypt, Proceedings of the Colloquium Held in Montepulciano, Italy, 22–24 August 2008. Edited by Valérie Angenot and Francesco Tiradritti. Studi Poliziani di Eggitologia 1. Montepulciano: Missione Archeologica Italiana a Luxor, pp. 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lamarque, Peter. 2010. The Uselessness of Art. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 68: 205–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lazardis, Nikolaos. 2010. Education and Apprenticeship. In UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. Edited by Elizabeth Frood and Willeke Wendrich. Los Angeles: UCLA Library. Available online: http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz0025jxjn (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Lesko, Barbara. 1994. Rank, Roles, and Rights. In Pharaoh’s Workers: The Villagers of Deir el Medina. Edited by Leonard H. Lesko. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, pp. 15–40. [Google Scholar]

- Luiselli, Michela. 2018. Les différentes formes de piété personnelle à Deir el-Medina. In À L’Œuvre On Connaît l’Artisan… de Pharaon!: Une siècle de recherches françaises à Deir el-Medina (1917–2017)I. Edited by Hanane Gaber, Laure Bazin Rizzo and Fréderic Servajean. Milan: SilvanaEditoriale, pp. 207–29. [Google Scholar]

- Maze, Daniel Wallace. 2013. Giovanni Bellini: Birth, Parentage, and Independence. Renaissance Quarterly 66: 783–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McDowell, Andrea G. 1994. Contact with the Outside World. In Pharaoh’s Workers: The Villagers of Deir el Medina. Edited by Leonard H. Lesko. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, Andrea G. 1999. Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Odiahi, Ese Vivian. 2017. The Origin and Development of the Guild of Bronze Casters of Benin Kingdom up to 1914. International Journal of Arts and Humanities, Bahir Dar-Ethiopia 6: 176–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariser, David, Anna Kindler, Axel van den Berk, Belidson Dias, Wan Chen Liu, and Belidson Diaz. 2007. Does Practice Make Perfect? Children’s and Adults’ Constructions of Graphic Merit and Development: A Crosscultural Study. Visual Arts Research 33: 96–114. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, Bengt Julius. 1974. Zeichnungen aus einer Totenstadt: Bildostraka aus Theben-West ihre Fundplätze. Themata und Zweckbereiche mistamt einem Katalog der Gayer-Anderson-Sammlung in Stockholm. Stockholm: Medelhavsmuseet. [Google Scholar]

- Plankensteiner, Barbara. 2010. Benin. Milan: 5 Continents Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Robins, Gay. 1994. Proportion and Style in Ancient Egyptian Art. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sainz, Immaculada Vivas. 2016. The Artist in His Context: New Tendences on the Research of Ancient Egyptian Art. Trabajos de Egtipologīa: Papers on Ancient Egypt. La Laguna: Universidad de La Laguna, pp. 203–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, Marina. 2023. Talking Images: A semiotic and visual analysis of three Eighteenth-Dynasty chapels in Deir el-Medina (TT8, TT340, TT354). In Deir el-Medina: Through the Kaleidoscope. Proceedings of the International Workshop Turin 8th–10th October 2018. Edited by Susanne Töpfer, Paolo Del Vesco and Federico Poole. Turin: Museo Egizio, pp. 651–76. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, Irving. 1954. The Aesthetics of ‘Art for Art’s Sake’. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 12: 343–50. [Google Scholar]

- Van Heel, Donker, and B. J. J. Haring. 2003. Writing in a Workman’s Village. Egyptolosiche Uitgaven XVI. Leiden: Nederlands Instituut Voor Het Nabije Oosten. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, Richard H. 1992. Reading Egyptian Art. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).