Abstract

The representation of Spain, and Spanishness in general, at sites of collective identity in the United States and Canada requires scholarly attention. Many monuments, which range from statues and museums to capitol buildings and national parks, continue to commemorate colonial times despite broader public awareness of the association between colonization and racialized violence, as well as the explicit movement toward decolonization. This commemorative material also demonstrates how non-Spanish settlers have appropriated historical moorings of Spain and its colonial past to reinforce and whitewash their identities in places such as New Mexico and Texas, and even in Newfoundland and Labrador. How monuments are funded and gain public support is another vector that points to the ways that identity—particularly, white identity—informs monumental architecture in ways that exclude people of colour, as well as women, who, when featured in monuments, are usually dehumanized as concepts rather than being the actors of settler-colonialism. This article explores these challenging topics with the aim of articulating a roadmap for future scholarship on this subject.

They take the shape of an obelisk dedicated to Christopher Columbus (Baltimore, Maryland, 1792), the relief of his bust in the Capitol rotunda (Washington, District of Columbia, 1824), and a statue depicting him as a child referred to as “the dreamer” (Vancouver, British Columbia, 1870). An outsized cohort of monuments commemorating and celebrating Christopher Columbus exists in both Canada and the United States compared with the Caribbean islands he visited, such as Hispaniola. Place names reinforce these connections, with seven settlements in Ontario, Quebec, and the Yukon named for Columbus, not to mention 22 streets in Quebec alone, in addition to the province of British Columbia and the Columbia River, and 146 more throughout the United States (GNBC 2023; USBGN 2023). Both countries also have places commemorating other agents of Spanish expansion into the Americas, including Ferdinand Magellan (c. 1480–1521), Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), Hernando de Soto (c. 1500–1542), Francisco Vázquez de Coronado (1510–1554), Juan de Oñate (1550–1626), Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra (1743–1794), and Alejandro Malaspina (1754–1810).

Monuments of this nature usually encompass architectural structures, whether in the form of a building or large-scale statue, such as the Columbus Memorial Statue and Fountain (1912) located in Columbus Circle (Union Station) in Washington, D.C., and the American-funded Monument to Columbus (also known as the Monument to the Discovering Faith, 1927–1929) featuring a 37-metre statue of Columbus facing the direction in which his ships sailed in 1492 in the southwestern city of Huelva, Spain. The scale of such built environments leaves the viewer feeling diminutive next to, or even completely enclosed within, the monument, which itself provokes curiosity and reflection, as well as engagement with the place’s purpose (Trouillot [1995] 2015, pp. 119–24). Lawrence Vale refers to these spaces as mediated monuments, being place emblems and symbols associated with modernity and progress, and statuary programmes representing a state’s history, all of which are contextualized through media campaigns that construct and shape their purpose as signifiers of a created past (Vale 1999, pp. 391–92). Emblems can be understood as a collection of symbols that link somehow to our identities; some will be more meaningful to us than others depending on who we are, and they usually form part of broader visualizations of ideology that express belongingness to a nation (i.e., flags and coats of arms), heritage or religious groups (i.e., the cross, signifying Christianity), and so on.

The scale of monuments sets them apart from other aspects of the built environment—they are intended to stick out, to project into our consciousness, and to connect to our present. Their theatricality lends itself to the narratological significance conveyed by monuments, whether in literal form from an explanatory plaque or a tour guide’s description, or through the monument’s projection of symbolic images. Landscape architecture, moreover, knits together a suite of plaques, dedicated fountains or benches, and statues to provide a structured, thematic, and often commemorative experience. Many historical city centres use landscape architecture to weave together historical monuments to further develop their coherence, on the one hand, while monetizing them through tourism, on the other.

As Peter van der Krogt contends in his research into Columbian monuments, the movement toward commemorating people like Columbus swelled in the late eighteenth century when former colonies transformed into nations in search of an origin story (van der Krogt 2023). European immigration over the last two centuries has reinforced colonial ties with the metropole, intensifying the desire to see actors of colonization from elsewhere in the world on the periphery of our identities as North Americans. In contrast, in recent decades, some forms of Spanish-colonial commemoration have been re-examined in regions colonized by Spain between 1492 and 1898. Commemoration, in these two contexts, either enables or opposes the delinking required to achieve decolonization in places such as the Americas (Mignolo 2007, pp. 449–514).

Delinking can be seen in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, where a Columbus statue was removed in 1987. Venezuela changed its holiday celebrating the cultural encounter marked by the arrival of white people, El Día de la Raza, to become the Día de la Resistencia Indígena in 2002. In a Latin American and Caribbean context, these reassessments of the value of Spanishness and Europeanity demonstrate how post-colonial identities forge different pathways untrodden by and delinked from a former colonizer and early modernity. But in Canada and the United States, the opposite—an embrace of early modernism through various forms of commemoration that celebrate past achievements, events, and their associated actors—seems to characterize monuments referring to Spain.

How is it that two countries for the most part disconnected from Columbus’s travels—Canada and the United States—have cultivated prominent monuments and sites for commemorating Spanish colonization, even in the twenty-first century? What does this desire to anchor colonial histories to architectural geographies sometimes unmoored from Spanish colonization say about Canadian and American values and identity? And how do race and racism inform and order that identity in sites designed to commemorate and celebrate the Spanish colonizer and to educate the broader public?

Through four case studies, and building upon the work of scholars such as Michel-Rolph Trouillot ([1995] 2015), I examine how Hispanicity and Spanish-colonial history have become appropriated and colonized for the purpose of shaping white identity in places such as Montreal, Newfoundland, and Louisiana. Early modernism provides a powerful discourse for identity programming. Place emblems, from coats of arms and frescos and reliefs to national and state legislatures and historic city centres, serve important roles in connecting the present to an early modern past. In parallel, I contrast commemorative material in areas touched by Spanish colonization—from Puerto Rico and New Mexico to Texas and British Columbia—to understand how the commemoration of Spanish colonization further deracinates Indigenous identities and histories from American and Canadian conceptions of themselves. By focusing on place emblems located in sites of Canadian and American collective identity—parliaments, capitol buildings, state museums, historical sites, and parks—this article complicates the modus operandi of the public-facing technologies we rely upon for shaping our identities.

The Comingling of Early Modernism, Fantasy Heritage, Heritage Tourism, and Monumental Architecture

Early modernism is defined as the assertion of early modernity (c. 1492–1800) in the late modern period (1800s–present). As a construct, early modernism is less interested in historical truth; rather, it discursively revives notions, referents, and historical moments from the early modern period, in this case, by making use of and even celebrating the so-called European Age of Discovery (Clarke 1996, p. 6; Gerzic and Norrie 2019, pp. 2–3). Early modernism creates an imaginary past in which alternative histories can thrive and influence our present, becoming bound up in our identities in sometimes uncritical ways. Early modernism underpins monuments created in the last 250 years or so that celebrate pre-1800 activities, such as colonial actors and discovery narratives. Furthermore, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Canada and the United States experienced mass immigration, which caused entanglements between different races, ethnicities, and religions in a time in which the quadricentennial of the Spanish invasion was celebrated with ceremonies, commemorative statues, scholarly work, and painting (Trouillot [1995] 2015, pp. 124–36). The parallel emancipation and enfranchisement of Black people and women’s suffrage, and concerted land theft from Indigenous peoples, today force us to deal with the ills engendered by early modernity (Kaufman and Sturtevant 2020, pp. 53–54; O’Brien 2010, p. 145; Wollenberg 2018, pp. 65–84).

This tension makes early modernist monuments contested as sites of commemoration. Many place emblems provide a location for traditional values, ideals, and objectives to share an imaginary or romanticized past with early modern roots (Cook 2019, p. 367). The halls of most seats of state, provincial or territorial, and national governments verbalize and iconize these goals for collective identity, which range from liberty and prosperity to commerce and justice, being steppingstones in a state’s origin story (Fox-Davis and Grafton 1991; Lears 1981, p. 142; Mock 2011; Pass 2016, p. 598). In the balance, however, early modernism in our present resurrects trauma associated with settler-colonial violence (i.e., the genocide of Indigenous peoples and the enslavement of Black people). It also results in commemorating mostly white men as actors in early modern narratives meant to glorify and provide a telemetry for white presence today in North America (Mignolo 1995). These uses for early modernism leave other demographics realizing and vocalizing their objections to having a white masculine past imposed upon them.

Decolonization in other milieux, such as Lisbon and its former colonies, has failed to prevent heritage tourism and commerce from being key means through which mythologies about early modern expansion abroad, in the case of Portugal, which mirrors the Spanish imperial experience, continue to be generated and reinforced through colonial-era monuments and celebrations of them manufactured for tourists and citizens alike (Domingos and Peralta 2023, pp. 1–24). Public discourse on this subject necessarily implicates the tourism industry, which uses monuments to attract visitors, and reveals a phenomenon that requires further consideration with respect to the appropriation of Spanishness in North America. Fantasy heritage captures the genealogical and cultural imagination through baseless claims to belongingness, such as pretendianism (a claim to be Indigenous when one is not; Kolopenuk 2023, pp. 468–73). For our purposes, fantasy heritage draws upon the belief that Spanishness nests into one’s ancestral past despite there being no clear linkage to Spain in one’s family line. In places such as Puerto Rico, fantasy heritage grows out of the claim to tri-cultural ancestry as a result of African, European, and Indigenous intermixing (Fusté 2020, pp. 120–31; Gil 2021). This phenomenon is particularly acute in the American Southwest, as well as the region’s monumental architecture. As we will see, a similar sense of attachment to Columbus and Italianicity appears to fuel his commemoration in North America in ways linking him to Spanish colonization as well as Catholicism.

As Frank G. Pérez and Carlos F. Ortega observe, “As a cultural enterprise, heritage tourism is a mixture of past and current events, a union between history and its use, often through exploitation, by contemporary community or regional elites” (Pérez and Ortega 2019, p. 14). In contrast to fantasy heritage, heritage tourism seeks to celebrate and monetize a place’s past through sites that usually feature monuments. As Derek H. Alderman establishes, artists, tour guides, community activists, government officials, museum curators, and business leaders serve influential roles as memorial entrepreneurs who shape how the public views and understands its past. Importantly, Alderman warns that “Remembering is accompanied, simultaneously, by a process of forgetting—an excluding of other historical narratives and identities from public consideration” (Alderman 2022, p. 31). It is this linkage between asserting a vague sense of Spanish identity and the uncritical acceptance of this claim that makes monumental architecture problematic from a racialized point of view.

From a narratological perspective, heritage tourism and fantasy heritage comingle to produce story arcs through history, whose protagonists often reflect the tourism cohort a place wishes to attract, and whose antagonists are likely gone, silenced, or overcome by the story’s hero. These sorts of narratives influence our collective memory as a society, and we then make fantasy historical accounts have presence through the shared elements of our identities (Shackel 2001, pp. 655–70). Fantasy heritage synchs into heritage tourism through the racialization of actors within the narrative, with white Spanish missionaries exemplifying this practice in monuments such as the XII Travelers Memorial (El Paso, Texas), explored in due course, through the belief in their selflessness, benevolence, and their roles in modernizing the region and seemingly caring for “helpless” Indigenous folks. These sorts of qualities and contributions model ones that become idealized through monumental architecture as a means of educating the broader public.

These connections between fantasy heritage and heritage tourism have economic implications. If a city desires to attract economic investment through tourism, for instance, through structured touristic experiences in the form of a guided tour or costumed tourism staff, it may shape the narrative portrayed through its heritage programming to appeal to the target demographics who will then spend their tourism dollars in their city. This cycle creates a feedback loop, whereby tourism is difficult to divorce from racism and sexism, on the one hand, while it reinforces the hierarchies of our identities by placing them on display—white male heroes having the greatest presence and power, women, for the most part, absent or dehumanized as allegorical concepts, and people of colour occupying the drudges of powerlessness, poverty, enslavement, and paganism from which they must be saved.

The capitol building in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, exemplifies this hierarchy in its monumental architecture. The region was not colonized by Spain, but the country did govern the former French colony of Louisiana from 1763 to 1803, shortly before it joined the United States in that year. Two sculptures by Lorado Taft bookend the 34-storey capitol’s grand staircase, one called “The Patriots” and the other “The Pioneers” (Figure 1). The latter statue features two columns of men on either side of some chests, behind which rises an allegorical figure reminiscent of Columbia, representing America, in her colonizing trek through the U.S. in John Gast’s American Progress (1872). The men represent early modern settler typologies positioned in chronological order, beginning, to the left, with a Spanish soldier dressed in early sixteenth-century armour—a reference to the Narváez-Cabeza de Vaca-de Soto expeditions along the region’s golf coast—followed by a missionary, a partly nude Indigenous man, a settler carrying tools, and then a hunter wearing a tasselled leather jacket (Figure 2). Across the stairs, the Columbia figure surmounted upon the chests is paired with the sixteenth-century Spanish soldier standing over a group of late modern settlers, also configured in two parallel columns. The Ellensburg Daily Record interpreted the female figure and two men at the front of each column in “The Pioneers” as “the spirit of adventure hovering over DeSoto and LaSalle” (Ellensburg Daily Record 1932).

Figure 1.

“The Pioneers” (1932) monumental sculpture in front of the Louisiana State Capitol building by Lorado Taft. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Figure 2.

Detail of “The Pioneers.” Author’s photo.

The presence of the Spanish in this context examples how fantasy heritage works by emphasizing Spanish colonial history, on the one hand, as well as the temporal inaccuracy of pointing to a pre-eighteenth-century Spanish settler presence in the region. The married notions of progress (the allegorical figure of Adventure-Columbia) and patriotism (the sixteenth-century Spanish soldier) furthermore greet visitors to the capitol complex. In parallel, the region also has many places that acknowledge the area’s French colonization, including the Acadian Memorial and Museum in nearby St. Martinville, Louisiana, built and operated in part by Acadian ancestors following their settlement in the 1750s and 1760s. This last example demonstrates how a sense of belongingness to a historical culture—French-speaking white settlers expelled by the British from Atlantic Canada, who then started anew in Louisiana—seeps into the identities of people generations removed and who no longer speak French or practice Acadian customs, and who have likely intermarried with non-Acadians for generations.

When fantasy heritage comingles with early modernism in this way, white exceptionalism as well as a false sense of a shared past become exulted in monumental architecture. The chronological placement of settlers in “The Pioneers,” moreover, demonstrates how Indigenous presence becomes disappeared from the demographic landscape of collective identity. They are neither first nor last but middled and contrasted by their lack of clothing against the indumenta that characterizes and periodizes white analogues (O’Brien 2010; Beck 2019). In other areas of the U.S. colonized by Spain, however, this discursive strategy becomes complicated by additional considerations of race.

Juan de Oñate in Texas and New Mexico

Juan de Oñate (c. 1550–1626) launched an expedition into the regions now known as New Mexico and Texas. He is most known for “la toma,” the moment in which he invaded the region in 1598. He seized Indigenous land in the present-day American Southwest and punished those who resisted him. Oñate was prosecuted by the Spanish crown in 1606 for what became known as the Acoma Massacre, where nearly 1000 Acoma were killed and 800 Indigenous women and men enslaved, with the men punished by amputating one of their feet. In the United States, some 40 sites commemorate Juan de Oñate as a Spanish founder of white civilization through names, plaques, statues, and architectural complexes (Historical Marker Database 2023; Fields 2022, pp. 471–87). I will focus on three such sites: Santa Fe’s historic centre (New Mexico), the Northern Rio Grande National Heritage Center (Alcalde, New Mexico), and the XII Travelers Memorial (El Paso, Texas).

Despite history remembering him as a Spanish conquistador through monumental architecture, and even in his English-language Wikipedia article, Oñate helped to create New Mexico’s earliest mestizaje. Born in present-day Zacatecas (Panuco), Mexico, to a conversa mother and a Basque conquistador, Oñate as a criollo went on to marry the great-granddaughter of Moctezuma (who was also the granddaughter of Hernán Cortés), Isabel de Tolosa Cortés de Moctezuma; their mestizo son became the first governor of Santa Fe. From a Spanish blood purity perspective, Oñate’s offspring would be categorized as not only criollo on Oñate’s side but also mestizo through his wife’s lineage, being an important distinction in the Spanish assessment of blood quantum. As Pérez and Ortega assess, “Oñate may have been part of the mestizaje, or cultural intermixing of Spaniard and Indian that created the Mexican people, but fantasy heritage turned him Spanish. He is thus a European, which is to say White, safe, and hegemonic” (Pérez and Ortega 2019, p. 30).

Statues and monuments must be seen in the context of the sites where they are placed. In Santa Fe, New Mexico, Cathedral Park contains a monument of the Oñate expedition, being the earliest Hispanophone settlers in the region, erected to celebrate the 400th anniversary of the Spanish invasion of the area. Supporting the upper register of the statue—from which face various types of settlers (white women, children, and, of course, men)—are the animals that the Spanish introduced into the region that would support their settlement. The adjacent Cathedral Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi was built between 1869 and 1886 on the site of two seventeenth-century and eighteenth-century Spanish churches. The building’s bronze doors display 20 vignettes that depict Spanish colonization and evangelization in the area. Part of the cathedral survives from 1717; this is now called La Conquistadora chapel in celebration of the Spanish reconquest following the Pueblo Revolt in 1680; it contains a wooden Madonna that Alonso de Benavides (c. 1578–1635) brought to New Mexico in 1626. The church’s coat of arms, which greets the visitor upon nearing its bronze doors, as well as on the floor within the church, display the Spanish crown’s colours (gold and red), as well as the date of the city’s founding (1610), and the symbol of Castile, Spain (a castle), on its shield.

A block away, borne along streets with names such as East San Francisco Street and West Palace Avenue is the Palace of the Governors site, which today forms part of the New Mexico History Museum complex. Lauded as the oldest European-constructed building in the continental United States, although it has undergone extensive renovations over the last century, it dates to 1610 and is where Oñate’s mestizo son, Cristóbal, lived while serving as the region’s governor. As the colonial seat of New Mexico, the building symbolizes Spanish colonization, as well as civilization and modernity, and in contrast to the Indigenous populations, whiteness; it also signifies collective state identity because the building served as its territorial capitol before New Mexico became a state. Meanwhile, the state’s history museum facing the former capitol building provides context for the region’s colonization and history.

The presence of material commemorating Spanish colonization has sparked mixed reactions about maintaining or removing monuments. In the late 1990s, when statues relating to colonialism began to attract greater scrutiny, the vocabulary being used at the time underlines the blending of race and heritage when it comes to Spanishness. One New Mexican newspaper demonstrates this problem. Referring to Oñate’s statuary, the author reflects that “To Hispanics, he was a gutsy trailblazer who bravely settled a New World,” and to some New Mexicans, he was a “Spanish conquistador” who settled the area. Oñate’s identity clearly intersects with the author’s sense of “Hispanic,” which cannot be Mexican-American because they were disenfranchised in the area and were already being referred to as Chicanos, Latinos, and Mexicans; Hispanic in this context refers to Spanish (The Robesonian 1998, 9A; Geyer 1998, 14A).

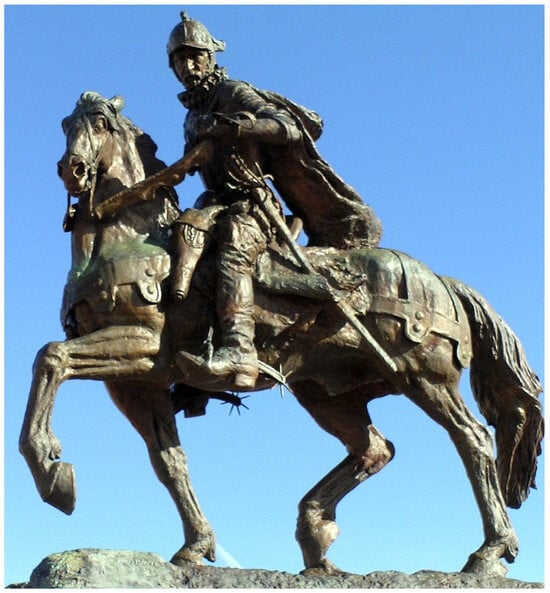

Oñate’s 12-foot-high equestrian bronze statue was created and installed in 1993 to mark his settlement in the area as well as the creation of a centre where visitors could learn about the man (Figure 3). It was removed from the Northern Rio Grande National Heritage Center in Alcalde, New Mexico, on a day that coincided with a protest against his commemoration in monument form in 2020, which was to dovetail with a right-wing counter-protest in favour of it remaining. LGBTQ2+, Black Lives Matter, and Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women supporters were satisfied to see this symbol of colonialism and genocide removed from public sight, whereas older, white Spanish-speaking men saw nothing wrong with the statue. They credit Oñate with introducing beasts of burden alongside transformative forms of agriculture and technology in ways that are linked to the region’s identity as cattle ranchers (Fields 2022, p. 471). References to Oñate extend beyond statues in this region of the U.S. as well; his name appears on street and building names and is associated with cultural events and even school mascots.

Figure 3.

Juan de Oñate on his horse (1993) by Reynaldo Rivera at the Northern Rio Grande National Heritage Centre in Alcalde, New Mexico. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.

As suggested by “Hispanic” pointing to Spanish heritage, the region is also impacted by the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century rise of residents affecting “Spanish-American” identity, which is different than Chicano, Hispanic, and Latino identities—the latter ones being clearly anchored to North American experiences of Hispanicity as people of colour relative to white people (Fields 2022, p. 474). While themselves not necessarily from Spain, their racial, geographical, and linguistic association with Oñate, who is usually identified as a Spaniard, created a form of collective identity for New Mexico’s Spanish-speaking population who have historically been marginalized by white Anglo Americans. Put a different way, people today who claim Oñate or, in the eastern part of the country, Pocahontas as a relative from 400 centuries ago can hardly be considered Spanish or Indigenous, whether from a blood quantum or cultural perspective, if there is no sustained genealogical or cultural heritage. The case of Louisiana Acadian identity may well reflect this problem of cultural appropriation as well, but likely to a lesser degree.

The perception that Spanish speakers in the region were of mixed heritage therefore met resistance among those espousing Spanish-American identity who emphasised their assumed European backgrounds and distanced themselves from racial stereotypes associated with Mexicans. Blood purity, in the Spanish sense of the concept, became one means through which Spanish-Americans asserted their racial superiority over non-Spanish Hispanophones in New Mexico. Through this paradigm, all Mexicans are people of colour, whereas Spanish-Americans are white (Nieto-Phillips 2004). This form of Spanish-American identity was fostered, in this case, through the interaction between whiteness and the Spanish language, which then became grafted upon the geography of Spain as a mythical point of origin, even though the geographical proximity of Mexico, as well as the vestiges of Spanish colonization in the area, rather point to a mestizo origin for most “Spanish-Americans.” Mestizo in the Spanish-colonial sense of the word refers to an individual of mixed racial heritage, for instance, possessing both New-Spain-born Indigenous and Spanish-born white backgrounds (Sue 2013).

The identity furthermore obviates the fact that Mexican-born white people of Spanish heritage—criollos—were themselves viewed as belonging to a lower class than Spanish-born white people—peninsulares (for a useful resource on the broader implications of the politics of blood in an early modern context, see Coles et al. 2015). This contrast between criollos and Spanish -Americans pushes us to think more broadly about how the identity expressed in this region mythologizes a collective sense of self, such that the Spanish government sent a delegation to New Mexico in 1998 to meet with Indigenous groups with the hopes of reconciling and protecting Oñate’s memory even though he was not a Spaniard and introduced mestizaje into the region (Rolwing 1998, 5C). The New Mexican government and its cultural institutions have invested in the concept of being a tri-cultural people—which mirrors how Puerto Rico, explored in due course, accounts for the composition of its people as well as its racialized history—being Indigenous or Mexican -American of colour (the latter being a means of obviating Spanish-speaking mixed and Indigenous people from the present), white Spanish -American, and white Anglophone (Mitchell 2005, pp. 101–21). The romanticization of the state’s racial composition has allowed its tourism industry to evade accounting for the colonial violence of its past.

Pushing back against commemorating Oñate and others similar to him also challenges the assertion of unsubstantiated Spanish -American identity. In El Paso, Texas, the XII Travelers Memorial located in the city’s Pioneer Plaza features statues that embody the region’s foundation myth of hero typologies (from Spanish conquistador to Benito Juárez), one of which includes Oñate, erected in 2007. This statuary programme collectively reinforces the complexity and porosity of borderlands identities and the racialized hierarchies that they inscribe while expressing what Gerardo Manuel Castillo has called a white, masculine sense of “us” versus a coloured sense of “them”. While 82% of El Paso’s population self-identify as Hispanic, which is not a specific racial category, 57% of them also identify as white, which helps us see the degree to which Spanish heritage has been appropriated in the city (Castillo 2023, pp. 8–11). As the director of a film about the statue’s creation contended while justifying the importance of the statue, “With very good intensions you want to promote Hispanic history and culture in a very Hispanic town” (Garay 2008, B4), thereby emphasizing the assumption that white Spanish speakers identify with Spain through Oñate, who they presume—not dissimilar to the Spanish delegation in New Mexico—to be of European origin.

The 36-foot-high bronze statue of Oñate in Pioneer Plaza that cost USD 2 million features him astride his rearing horse as he realizes the historical moment for which he is most known in the area, “la toma.” In places such as Albuquerque, New Mexico, broader calls to remove Oñate from the names of schools have been somewhat successful, bolstered by recent scrutiny of monuments and those who decide to invest in them. In the case of confederate and conquistador statues, there is a clear connection between groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and the erection of statues that project white greatness. The El Paso mayor and Klan member, Thomas Calloway Lea (1877–1945), promoted the idea of using local history to boost tourism in the area through projects such as the XII Travelers. The monument’s sculptor based his series on an illustrated book by Lea’s son (Pérez and Ortega 2019, p. 57).

The XII Travelers project also features the Fray García Monument as the initial statue, erected in 1996, celebrating the arrival of Christianity to the area as well as the establishment of missions and European agricultural practices in 1659 (Figure 4). García de San Francisco (1602–1673) came to Mexico from Spain in 1629, served as a Franciscan priest, and in 1659, established the Our Lady of Guadalupe mission. It was strategically located along the Camino Real, thereby linking El Paso with what became Ciudad Juárez. The statue depicts him with a pendant of Guadalupe—an increasingly powerful cult for an Indigenized Mary during his lifetime—around his neck, holding a length of wood, which became a beam used to edify the mission, and at his feet are mission grapes, signifying European agriculture.

Figure 4.

The Fray García Monument (1996) by John Sherrill Houser located in Pioneer Plaza, El Paso, Texas. Courtesy of XIITravelers.org.

Returning to the backers of identity projects such as this one, the XII Travelers advisory board includes an honorary Consul of Spain—a pro-Spanish advocate—and the project has had stilted development since its approval in 1988. While García’s statue was placed as planned in Pioneer Plaza, Oñate’s was moved to the El Paso airport and renamed “The Equestrian” to avoid explicit association with Oñate and his legacy. The statue’s history points to the broader process through which the monument was conceived. When shortlisting the subject matter of the twelve statues, the planning committee agreed on four people of Spanish origin—three supposed Spanish, one enslaved Black soldier (Cabeza de Vaca, Estebánico, and Oñate and García)—and four people of Anglo-Saxon origin—three men and one woman (Zebulon Pike, James Magoffin, John Wesley Hardin, and Susan Shelby). It also considered three Mexican-born officials (Juan Batista de Anza, Pancho Villa, and Juárez), one African American (Henry Ossian Flipper), and two monuments relating to the region’s Indigenous peoples (Castillo 2023, pp. 13–14). The complex of statues idealizes colonial activities and actors in all but two cases, which, as Castillo argues, must be read through the prism of the city’s tourism and economic development objectives. This balance of white to non-white people reflects the racialized presence in Louisiana’s capitol entrance.

Furthermore, the project’s conceptualization of “travellers” promotes the conversion of foreigners into settlers, on the one hand, and synchs into the tourist’s own activities as one exploring El Paso for perhaps the first time. These traveller typologies maintain racial and vocational separations between white Anglophones and Hispanophones, Blacks, and Indigenous groups. In so doing, the project reflects these socio-cultural divisions back at the viewer, who is meant to see himself in the statues. Despite these limitations around identity, monuments such as this one have also become sites of Indigenous survivance and resurgence. When Oñate’s statue in Alcalde, New Mexico, was vandalized in 1998—the removal of one of the statue’s feet—it amounted to a message of retribution for Oñate’s own crimes against the region’s Acoma warriors four centuries earlier. The vandalism also demonstrated that these sites of commemoration are perishable.

Exploration furthermore invites others to embrace Oñate in contemporary contexts. When the governor broke ground for New Mexico’s Space Port America project in 2009, he was pictured surrounded by men attired in sixteenth-century Spanish clothing (Pérez and Ortega 2019, pp. 28–29). The comparison of Spanish settler-colonialism in this region to the potential for similar colonization in outer space is clear, as is the fantasy heritage that ascribes adventuring, mineral-seeking, spacecraft-riding explorers to the region’s white Spanish spirit.

El Capitolio of San Juan, Puerto Rico

According to the 2020 Census, Puerto Rico’s racial makeup is about 0.5% Indigenous, 7% Black, 17% white, and 50% mixed, with the remainder identifying as other categories. Researchers have long known, however, that anti-Blackness in this U.S. territory has influenced how people self-identify, with mixed-race and Black people opting to check “white” on the country’s census (Godreau 2018, pp. 129–51; also see Niell 2015; Niell 2021; USCB 2020). And despite its small white population, the island’s monumental architecture exhibits a significant degree of whitewashing (blanqueamiento), particularly in light of Puerto Rico’s rosy portrayal of the three peoples—Taino, African, and Spanish—blending together to create the Puerto Rican people.

Not far from the Capitolio (capitol building) in San Juan is a water monument called “Raíces” (Figure 5), meaning “roots,” unveiled in 1992 for the quincentennial of Columbus’s first voyage (although he visited the island on his second voyage in 1493). It was designed by Spanish sculptor, Luis Antonio Sanguino de Pascual (Capó García 2023, p. 385). The island’s labour potential, in Spain’s eyes, was quickly monopolized, and the Indigenous Taino population suffered from European-borne disease. The enslaved Africans who followed in their wake were joined by white Spanish-speaking criollos borne on the island, and Spain continued to exploit the island over the next 400 years for sugar, tobacco, and coffee until the late nineteenth century (Nichols 2019, pp. 449–63). It is in this light that the fictive convergence of three identities—Indigenous, Black, and white—informs the island’s programme of collective identity. The explanatory plaque for Raíces, however, refuses to engage explicitly with the mythology behind Puerto Rico’s racial composition. Instead, it defines the central, elevated figure as an allegorical woman representing the island; her nude body and Caucasian features contrast against the Taino and African figures that flank her on the fountain’s middle register.

Figure 5.

The Raíces fountain in old San Juan, Puerto Rico (1992), by Miguel Carlo. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.

Nearby, the Capitolio complex exhibits many references to Spanish colonial times, including an inset stone marking the location of the legislative assembly on the capitol grounds, versions of which also serve as the territory’s seal and coat of arms (Figure 6). Beyond the lion and castle signifying the arms of Spain, as well as the Catholic Kings, it also features the initials F and I, for Ferdinand and Isabel, along with elements from their coat of arms (a yoke and arrows), which were later used by the party of the Spanish dictator, Francisco Franco (1892–1975). This medallion is reproduced throughout the Capitolio in its cupula and large stained-glass and ceramic arrangements. Despite broader movements to remove colonial symbols in Puerto Rico, particularly after 2020 (Aljazeera 2020), symbols such as the ones embedded in the territory’s coat of arms have yet to be problematized.

Figure 6.

Inset stone marking the territorial legislative assembly of Puerto Rico (2012). Photo courtesy of the author.

Across from the visitor’s entrance on the Capitolio’s eastern door is a ceramic mural depicting “Un Siglo de Democracia” (a century of democracy), which reproduces the territorial seal from the northern side of the complex and explains how “los pueblos que recuerdan la historia forjan el mejor camino hacia el futuro” (the peoples who remember history forge a better path toward the future). Behind the inscription monument, the mural offers the viewer several vignettes depicting governance, primarily by white people, and when Black or mixed-race rulers are included, their skin is whitened. Similarly, around the Capitolio’s impressive cupula are murals, which punctuate the four corners of the upper level, each featuring white people from different eras of the island’s colonial and post-colonial existence as an American colony and territory. One by Rafael Tufiño depicts the abolition of slavery with a shirtless Black man raising his arms in triumph foregrounded by a group of white politicians.

As a collection of monumental sites, the absence of Afro-Latinidad in commemorative material contrasts with the racial reality of the island and its historical causes from colonization and slavery. Indeed, as Isar P. Godreau, Mariluz Franco Ortiz, and Sherry Cuadrado contend, the island’s school children are not exposed to slavery, mestizaje, or blanqueamiento from a curricular perspective. When they visit sites of collective identity such as the Capitolio, moreover, they—most of whom are Black or mixed-race—encounter deeply colonial forms of commemoration alongside representations of white people and to a much lesser degree Indigenous people whom they are taught have become extinct (Godreau et al. 2008, pp. 115–35). The emphasis on whiteness also points to the conditions of coloniality under which Puerto Ricans lived after their island ceased to be a Spanish colony and transformed into a U.S. territory.

The Capitolio itself is a complex created by architects who trained in the United States and Europe, who imported Spanish revival and neoclassical styles as well as a mainland monumental architectural aesthetic to San Juan, for instance, the inclusion of a cupula, which most American capitol buildings have. Similar to the mainland, vague signifiers of Indigeneity help to project collective identity and values for concepts such as democracy. As Hartman observes, “the building’s architecture reenacted the social hierarchies and histories of empire in the ancient tradition, with the United States taking the place of Rome” (Hartman 2022, p. 237). The imperial agenda of the United States in this era, then, resonates with how Louisiana, New Mexico, and Texas have commemorated their connection to Spanish colonialism—however tenuous it was in the case of Louisiana—because through the semblance of a Spanish past, these states could position themselves as subsequent leaders of imperial greatness, following in the footsteps of Spain.

Coastal Historical Sites of Canada

Similar to the United States, Canada’s east and west coasts are punctuated with historical sites that acknowledge a fleeting Spanish presence in the area, of which two provide important context for the appropriation of identity seen in American monumental architecture relating to Spanish colonization—Red Bay National Historic Site in Labrador, marking the sixteenth-century Spanish Basque Atlantic whale fishery, and the Yuquot National Historic Site in British Columbia, commemorating late-eighteenth-century Spanish Pacific exploration.

In contrast to most of the sites studied so far, both intentionally preserve ruins, remains, and surviving structures from each period, and neither site is intended to explicitly inform domestic tourists about their own identities. Their isolated locations make them different from urban monumental architecture in that rather than heritage tourism, Canadians have increasingly been seeking out rural tourism that draws them afar and can be combined with other forms of recreational activity, such as kayaking (Ramos et al. 2016, p. 210). As protected national sites, they offer a complex landscape architecture that makes use of the topographical features that attracted Spaniards to the area, in addition to the built environment. These sites for the most part characterize the Spanish as visitors disconnected from heritage tourism relating to Canadians as target audiences.

That being said, the Red Bay National Historic Site was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2013, and not far away is a second UNESCO site marking the landings of Vikings, which puts it on the horizon of tourists from around the world, including Spain, who commune with their nation’s past when visiting Red Bay. The UNESCO designation underlines the sorts of activities it aspires to recognize—in this case, European visits to eastern Canada as well as resource extraction. The museum complex offers costumed guides, scale models of buildings, artifacts and photography, as well as a documentary that visitors can watch in the museum’s theatre that covers Basque history in Newfoundland four centuries ago, making it the earliest and most sustained location of Spanish contact within the U.S. and Canada. It features a sixteenth-century Basque fishing boat (chalupa) and offers seasonal programming that includes a tasting of sixteenth-century Basque pintxos (tapas or small snacks). The complex therefore attempts to offer a simulation of Basque whaling life, which includes the remains of the shipwrecked vessel, San Juan, near Saddle Island. This nao inspired international cooperation between Canada and Spain to create a life-size replica of the vessel—a project for which a museum complex has opened in Gipuzkoa, Spain, with the goal of bringing the San Juan to Labrador in 2026. In addition to whale processing equipment from the period, Red Bay also has a museum, wharves, living quarters, a cemetery, and interpretive material for the underwater remains.

Canadian coastal areas are littered with former sites of resource extraction that have now become locations for heritage preservation and tourism. Place identity has therefore transformed into a means of using a community’s bygone industries to sustain the community today, while in tandem, the presence of touristic infrastructure disincentivizes resource extraction. As Allison Gill and Erin Welk contend, rural tourism becomes associated with healthier landscapes free of the contaminants and business of urbanity, which once again points to how class and economic means—and, therefore, racialized socioeconomic levels of prosperity—inform who gets to visit sites that are more isolated and costly to access (Gill and Welk 2007, pp. 169–83). Ecotourism mixes with whiteness, as Bruce Erickson observes, when tourism establishes either distance and difference between the tourist and the target of his gaze, or proximity and relatedness (Erickson 2018, p. 44). A site’s whiteness, in the case of a Basque fishing settlement in Labrador, reinforces the place identity of white visitors, whether from Canada or Spain, in a land historically inhabited by Indigenous and Inuit peoples, stimulating feelings of belongingness that may also work across the Atlantic by fomenting a connection for Canadians with northern Spain. Sites such as this one convert the other—Basques—into us—Canadians. The opposite is also possible: Canadians visiting the museum where the replica of the San Juan is under construction learn about these historical ties between the two countries’ Atlantic coastal regions, all of which contrasts remarkably with how whiteness stratifies identity in the American Southwest. Whether in New Mexico or Labrador, then, racism becomes an essential building block in the touristic experience and therefore projects from its monumental architecture.

The Yuquot National Historic Site in British Columbia deepens this observation about whiteness and familiarity. Located in Friendly Cove, Nootka Island, British Columbia, it falls within the traditional lands of the Mowachaht/Muchalaht (Nootka) First Nation and was designated a national historical site in 1923 for the brief Spanish settlement located there in the late eighteenth century. Juan José Pérez Hernández (c. 1725–1775) is credited as being the first Spaniard to come to the region in 1774. Bodega y Quadra followed in his wake in 1775, leading to a sustained Spanish presence in the region, claims upon which were contested by other nations, including by James Cook (1728–1779) for the British. The Spanish colony of Santa Cruz de la Nuca was founded in 1789 but only lasted a few years, mostly due to the Nootka Convention, which resulted in ceding control to Britain.

Yuquot offers visitors an impressive view of water and topography, as well as a considerably varied built environment that includes a whaling facility, a Spanish fort and related village, and an English fur trading facility, as well as wharves. As the site of the Nootka Convention, the village represents white diplomacy between the British and Spanish and foregrounds Mowachaht/Muchalaht ancestral presence in the same place. Today inhabited by a Mowachaht/Muchalaht family as well as some lightkeepers, the facility offers a glimpse into what life was like in the Spanish settlement. This may well be the only Indigenous-run Spanish-colonial tourism operation in Canada through which the historical site’s monetization benefits Indigenous people rather than one or more levels of government.

In contrast, in 1995, the Land of Maquinna Cultural Society formed to both promote and recover Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation heritage and to lobby to have Yuquot re-designated as a national historical site from an Indigenous perspective; this was approved in 1997 (Quan 2017). The cultural society seeks to raise money by offering tourist experiences in Yuquot, building a museum and interpretive centre to house cultural heritage once it is repatriated from the various institutions around the world that hold it, and maintaining settler-colonial heritage located within this First Nation’s territory. The space, which will be called Nis’Maas after chief Maquinna’s big house, serves as an Indigenous-colonial centre where visitors can learn more about Maquinna’s interactions with the likes of Bodega y Quadra as well as about Indigenous presence, industry, and culture (Price 2020, pp. 21–22). The opportunity to develop such a site resists tourism’s settler-colonial white normativity while envisioning a museological space that will contest the usually Eurocentric narrative associated with sites of Spanish colonization so as to reclaim space and the history that it occupies.

This intervention into Spanish colonial presence can be seen in the First Nation’s renovation of a church formerly associated with the colony and since converted into the Yuquot Tourism Centre. By recontextualizing this space, which greets visitors as they approach from the water, the Mowachaht/Muchalaht appropriate part of the Spanish outpost from the 1790s.

After a restoration process in the 1950s, the government of Spain bestowed two stained-glass panels upon the First Nation, which now reside in the church. The first of these shows a Spanish and British boat off the coast of the sound in the moment of negotiating the convention, dated 28 August 1792 and written in Spanish (Figure 7). Titled “Reunión de los capitanes Bodega-Quadra y Vancouver” (meeting between captains Bodega-Quadra and Vancouver), the panel projects sincerity and politeness behind the exchange. The whiteness of the captains’ skin glows with the light behind it, while the Maquinna people passively look on at the accord’s realization. Confronting these vestiges of colonial architecture and the panels that commemorate them are Indigenous carvings and other objects that usually find themselves marginalized in settler museological spaces, and which have no role in the Spanish panels. In this way, Indigenous material and ceremonial culture occupy a monument to Spanish colonization, and the First Nation has plans to expand this influence potentially throughout the region.

Figure 7.

Stained-glass panel from the Last Spanish Exploration National Historic Event complex gifted by the Embassy of Spain to Canada. Photo courtesy of https://slowboat.com/2017/09/friendly-cove-yuquot/and Laura Domela. Accessed 15 September 2023.

That being said, the influence of foreign nations over commemorative material—whether the nao San Juan or the stained-glass panels—also points to broader ways that our sense of collective identity can be shaped exogenously.

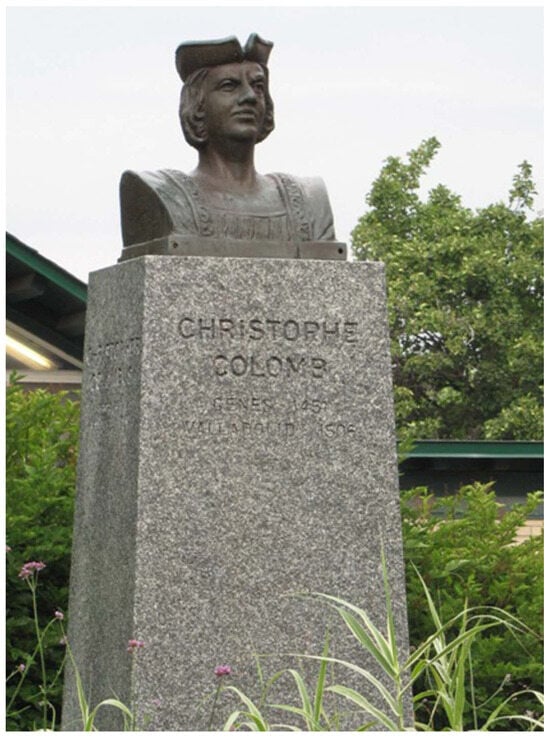

The Columbuses and Catholic Kings of Montreal

In contrast to the southern United States, Canada has had little early modern contact with Spain, with the exception of its coastal regions. In the country’s interior, however, several programmes of monumental architecture commemorate Spanish colonization. The bronze bust of Columbus in Montreal’s Parc de Turin was purchased by the Centre Amerigo Vespucci, the Fédération italo-canadienne du Québec, the Knights of Columbus, and the City of Montreal (Figure 8). Its placement in the city’s Little Italy neighbourhood and a park named for an important Italian city, in 1976 was meant to revive the community’s memory of the explorer’s Genovese and not Spanish roots.

Figure 8.

The bronze and granite bust of Columbus (1976) in Parc Turin in Montreal by Armand de Palma. Photo courtesy of Art Public Montréal.

Similarly, in Montreal’s Parc Sir-Wilfrid-Laurier, located along the Avenue Christophe-Colomb, a bronze monument to Isabel “la católica,” Queen of Castile, who supported Columbus’s initial expedition, was gifted to the city in 1959 by the Instituto de Cultura Hispánica de Madrid and the consul general of Spain (Art Public Montreal 2023). It was vandalized with red paint in 2015 for Isabel’s “crimes against humanity” in supporting the colonization of the Americas. In an interview with Vice.com, the anonymous artist responsible for vandalizing the statue cited Isabel’s role in establishing the Spanish Inquisition, exiling Jews and Muslims from Spain, invading and committing genocide in the Americas, and so on. About the statue, they offered a parallel context for imagining “if history went a different way and Germany went to Poland and offered them a bust of Hitler” (Noël 2015). This statue highlights how commemorative monuments incite division because people value and view history differently. For some, Isabel and Columbus represent power, ambition, moral rectitude, and accomplishment, whereas for others, they are responsible for genocide, land theft, religious zealotry, and, in general, human rights abuses. The monuments then become a flashpoint for public discourse across starkly divergent lines.

As Analays Alvarez Hernandez observes, ethno-cultural monuments such as these two are often sponsored and funded by diasporic groups, sometimes in conjunction with governments, charities, and corporations (Alvarez Hernandez 2019, p. 43). As such, “Ethno-cultural monuments are forms of intentional place and identity building that can be understood simultaneously as assertions of power over particular areas as well as social agents fostering a sense of belonging or neighborhood” (Alvarez Hernandez 2019, p. 47). This practice has resulted in an unusual emphasis on monuments that have little to no connection to Canada’s past precisely because the groups who sponsor them represent newcomers and settler constituencies with ties to elsewhere in the world. Monuments of this nature tend to express pride in one’s non-Canadian past, or favour associations of power and authority with historical figures such as Columbus and Isabel.

At the same time, and as shown by the XII Travelers Monument, national interests outside of North America exercise influence over commemorative sites. In the case of the stained-glass panels and bust of Isabel—both gifts of the Spanish government in the 1950s—the timing of these diplomatic gifts coincided with a Francoist agenda aimed at opening up Spain and improving its economy. What Spain then deemed worthy of commemorating within a settler-colonial milieu may be at odds with broader movements against, in that case, European struggles with fascism. Pro-fascist states supplying historical monuments to democratic ones seem to have had a second purpose beyond international relations to potentially shape ideology in other countries.

Ethnocultural monuments also appeared across the U.S. in the 1920s–1970s, many relating to Columbus and Vespucci that were sponsored by Italian heritage groups. Ostensibly, throughout the twentieth century, the rhetoric of manifest destiny had become widely absorbed into American identity. One monument to Columbus in Denver, Colorado, exemplifies this sentiment. A 15-foot-tall sculpture of Columbus with his arms and legs extended similar to the Pythagorean man and enclosed within a series of circles that create a sphere around him, was erected in 1970 by an Italian American couple (the Adamos) to the “Italian Visionary and Great Navigator. This bold explorer was the first European to set foot on uncharted land, on a West Indies beach in 1492. His four voyages brought Europe and America together, forever changing history. A new nation was to rise. A new Democracy was born.” The pedestal supporting the statue was covered with a graffiti mural portraying a crow resting within a human skeleton as part of the Black Love Mural Festival in 2020 (Calhoun 2020; Solomon 2020), being another means through which these monuments become appropriated and the spaces they occupy reclaimed by, in this case, Indigenous and Black peoples.

Conclusions

When we think about museums and parks as carceral spaces, we acknowledge how they limit who can access them and under what conditions. As spaces meant to direct and control our gaze—a cupola that draws our eyes skyward, an inscription at the foot of a large statue that demands to be read—monuments tend to be designed to direct how we interact with them. Capitol and legislative buildings offer restricted access to parts of the building and altogether exclude individuals who must work elsewhere during the workweek because they are usually closed during the evenings and on the weekends. Certain demographics typically have more leisure time as well as the finances to afford tourism, which leaves those without such means unable to access monuments. When thought of along racialized lines, therefore, and given the whiteness of monument culture in places such as Canada and the United States, the use of Columbuses, Bodega y Quadras, and Oñates forces us to contend with how Spanishness has been harnessed to racialize collective identity in Anglophone and Francophone North America for different purposes.

The comingling of early modernism, fantasy heritage, and heritage tourism in monumental architecture demonstrates broader trends in the propagation of white identity in problematic ways. While statues such as those of Columbus and Oñate have been removed or recontextualized following public protests against the violence that they inscribe upon the landscape, the fact is that monuments to these men continue to permeate Canada and the United States through statues, paintings, place names, and the buildings and grounds that house them. This article has focused on Spanishness, but it is clear that similar commemorative programmes exist for British and French—and, therefore, white—colonial identities, as exampled by the Acadian Museum in St. Martinville, Louisiana. In contrast, monuments to Black history in Canada and the United States are limited and often characterized by hardship and survivance, in the case of the privately funded Legacy Museum recognizing Black excellence alongside racial violence and slavery located in Montgomery, Alabama.

Who supports monumental infrastructure is an important question that requires further investigation, as the Legacy Museum operates through a network of Black organizations, whereas Oñate’s El Paso statue is funded through municipal government as well as interest groups from the private sector, including local businesses. To what degree is white history more easily funded than that of Indigenous and Black peoples, and how does this apparent disparity further entrench white supremacy into our identities from a public spending perspective? As the sources I point to throughout this article demonstrate, there is surging interest on the part of scholars to better understand how monuments inform our identities, but there remains little work that critically questions the racism and sexism underlying these monuments. How many street names in the U.S. and Canada celebrate the masculine actors of settler-colonial violence? How might public funding for monuments and their maintenance be redirected in more equitable ways? How could national or provincial committees on monuments assist municipalities in developing policies aimed at avoiding the implication of colonial violence in their commemorative programmes? These questions just scratch the surface of a broader array of problems facing North Americans while we gaze upon sites of collective identity.

Funding

This research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada through Insight Development Grant 430-2023-00180.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Alderman, Derek H. 2022. Commemorative Place Naming: To Name Places, to Claim the Past, to Repair Futures. In The Politics of Place Naming: Naming the World. Edited by Frédéric Giraut and Myriam Houssay-Holzschuch. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Aljazeera. 2020. Puerto Rico Looks to Colonial Legacy as Statues Tumble in US. Aljazeera, July 11. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez Hernandez, Analays. 2019. The Other(’s) Toronto Public Art: The Challenge of Displaying Canadians’ Narratives of a Multicultural/Diasporic City. RACAR: Revue d’art Canadienne/Canadian Art Review 44: 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Art Public Montreal. 2023. Monument à Christophe Colomb. Available online: https://artpublicmontreal.ca/en/oeuvre/monument-a-christophe-colomb/ (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- Beck, Lauren, ed. 2019. Firsting in the Early Modern Transatlantic World. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, Patricia. 2020. Goodbye, Columbus? Civic Center Park Statue Off City Website… For Now. Westword, June 24. [Google Scholar]

- Capó García, Rafael V. 2023. Monuments to Mestizaje and the Commemoration of Racial Democracy in Puerto Rico. Visual Anthropology Review 39: 350–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, Gerardo Manuel. 2023. El memorial de los XII viajeros del suroeste en El Paso, Texas: La construcción de una identidad regional en una ciudad de frontera de los EE.UU. Anthropologica 41: 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Bruce. 1996. Dora Marsden and Early Modernism: Gender, Individualism, Science. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coles, Kimerly Anne, Ralph Bauer, Zita Nunes, and Carla L. Peterson, eds. 2015. The Cultural Politics of Blood, 1500–1900. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Megan L. 2019. Blazon. New Literary History 50: 363–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos, Nuno, and Elsa Peralta, eds. 2023. Legacies of the Portuguese Colonial Empire: Nationalism, Popular Culture and Citizenship. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Ellensburg Daily Record. 1932. The Evening Record, March 22, no. 136.

- Erickson, Bruce. 2018. Anachronistic Others and Embedded Dangers: Race and the Logic of Whiteness in Nature Tourism. In New Moral Natures in Tourism. Edited by Bryan S. R. Grimwood, Kellee Caton and Lisa Cooke. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, Alison. 2022. Visualizing Juan de Oñate’s Colonial Legacies in New Mexico. Journal of Genocide Research 24: 471–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox-Davis, Arthur Charles, and Carole Belanger Grafton. 1991. Heraldry: A Pictorial Archive for Artists and Designers. Newburyport: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Fusté, José I. 2020. Schomburg’s Blackness of a Different Matter: A Historiography of Refusal. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 24: 120–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, Anabelle. 2008. Film Shows Fight over El Paso Conquistador Statue. Victoria Advocate, July 14. [Google Scholar]

- Geographical Names Board of Canada. 2023. Canadian Geographical Names Database. Available online: https://geonames.nrcan.gc.ca/search-place-names/search (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- Gerzic, Marina, and Aidan Norrie, eds. 2019. From Medievalism to Early-Modernism: Adapting the English Past. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer, Georgie Anne. 1998. War of the Statues. The Victoria Advocate, August 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, Guillermo Rebollo. 2021. Whiteness in Puerto Rico: Translation at a Loss. London: I.B. Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, Allison, and Erin Welk. 2007. Natural Heritage as Place Identity: Tofino, Canada, a Coastal Resort on the Periphery. In Managing Coastal Tourism: A Global Perspective. Edited by Sheela Agarwal and Gareth Shaw. Blue Ridge Summit: Channel View Publications, pp. 169–83. [Google Scholar]

- Godreau, Isar P. 2018. Racial Nationalisms in the US Territory of Puerto Rico. In Latino Peoples in the New America: Racialization and Resistance. Edited by José A. Cobas, Joe R. Feagin, Daniel J. Delgado and Maria Chávez. New York: Routledge, pp. 129–51. [Google Scholar]

- Godreau, Isar P., Mariolga Reyes Cruz, and Mariluz Franco Ortiz. 2008. The Lessons of Slavery: Discourses on Slavery, Mestizaje, and Blanqueamiento in an Elementary School in Puerto Rico. American Ethnologist 35: 115–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, Joseph R. 2022. Making Islands Beautiful (Again?): Rhetorics of Neoclassicism in the US Insular Empire. In Imperial Islands: Art, Architecture, and Visual Experience in the US Insular Empire after 1898. Edited by Joseph R. Hartman. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 223–44. [Google Scholar]

- Historical Marker Database. 2023. Available online: https://www.hmdb.org/ (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Kaufman, Amy S., and Paul B. Sturtevant. 2020. The Devil’s Historians: How Modern Extremists Abuse the Medieval Past. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kolopenuk, Jessica. 2023. The Pretendian Problem. Canadian Journal of Policial Science 56: 468–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lears, T. J. Jackson. 1981. No Place of Grace: Antimodernism and the Transformation of American Culture, 1880–920. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, Walter. 1995. The Darker Side of the Renaissance: Literacy, Territoriality, and Colonization. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mignolo, Walter. 2007. Delinking: The Rhetoric of Modernity, the Logic of Coloniality and the Grammar of De-Coloniality. Cultural Studies 21: 449–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Pablo. 2005. Coyote Nation: Sexuality, Race, and Conquest in Modernizing New Mexico, 1880–1920. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mock, Steven. 2011. Symbols of Defeat in the Construction of National Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, Lizzy. 2019. Our Own Monument: Landscape in the Linguistic Others of Quebec and Puerto Rico. American Review of Canadian Studies 49: 449–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niell, Paul B. 2015. Urban Space as Heritage in Late Colonial Cuba: Classicism and Dissonance on the Plaza de Armas of Havana, 1754–1828. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Niell, Paul B. 2021. Architecture, Domestic Space, and the Imperial Gaze in the Puerto Rico Chapters of Our Islands and Their People (1899). In Imperial Islands. Edited by Joseph R. Hartman. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 103–21. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto-Phillips, John M. 2004. The Language of Blood: The Making of Spanish-American Identity in New Mexico, 1880s–1930s. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. [Google Scholar]

- Noël, Brigitte. 2015. Montreal Statue in Blood in Protest of Queen Isabella. Vice.com, December 17. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, Jean M. 2010. Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians out of Existence in New England. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pass, Forrest D. 2016. Strange Whims of Crest Friends: Marketing Heraldry in the United States, 1880–1980. Journal of American Studies 50: 587–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Frank G., and Carlos F. Ortega. 2019. Deconstructing Eurocentric Tourism and Heritage Narratives in Mexican American Communities: Juan de Oñate as a West Texas Icon. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Price, John. 2020. Relocating Yuquot: The Indigenous Pacific and Transpacific Migrations. BC Studies 204: 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, Douglas. 2017. The Race to Preserve a B.C. First Nation’s History and the Village Where There Is Only One Couple Left. National Post, August 10. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, Howard, Mark C. J. Stoddart, and David Chafe. 2016. Assessing the Tangible and Intangible Benefits of Tourism: Perceptions of Economic, Social, and Cultural Impacts in Labrador’s Battle Harbour Historic District. Island Studies Journal 11: 209–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolwing, Rebecca. 1998. Indian Tribes, Spanish Seek to Settle 400-Year Old Grudge. The Sunday Courier, February 15. [Google Scholar]

- Shackel, Paul A. 2001. Public Memory and the Search for Power in American Historical Archaeology. American Anthropologist 103: 655–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, Jon. 2020. Black Love Mural Festival Protects Monuments from Graffiti. Westword, June 11. [Google Scholar]

- Sue, Christina A. 2013. Land of the Cosmic Race: Race Mixture, Racism, and Blackness in Mexico. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- The Robesonian. 1998. New Mexico Grapples with Celebrating a Spanish Conquest. The Robesonian, May 1. [Google Scholar]

- Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 2015. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press. First published 1995. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. 2020. Census. Available online: https://data.census.gov/table/DECENNIALPL2020.P1?g=040XX00US72 (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- U.S. Board on Geographic Names. 2023. Geographic Names Information System. Available online: https://edits.nationalmap.gov/apps/gaz-domestic/public/search/names (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- Vale, Lawrence J. 1999. Mediated Monuments and National Identity. The Journal of Architecture 4: 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Krogt, Peter. 2023. Geographical Distribution of Monuments for Christopher Columbus. Available online: https://vanderkrogt.net/columbus/texts/shd_paper.html (accessed on 5 October 2023).

- Wollenberg, Daniel. 2018. Medieval Imagery in Today’s Politics. Leeds: ARC Humanities Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).