“Grand Narratives” and “Personal Dramas”: (Re)reading the Masterpieces by Artemisia Gentileschi

Abstract

1. Introduction: La grande pittrice

2. Traumatised Figures: Judiths and Susannas

“Whereas Vasari used the device of biography to individualize and mythify the works of artistic men, the same device has a profoundly different effect when applied to women. The details of a man’s biography are conveyed as the measure of the ‘universal’, applicable to all mankind; in the male genius, they are simply heightened and intensified. In contrast, the details of a woman’s biography are used to underscore the idea that she is an exception; they apply only to make her an interesting case. Her art is reduced to a visual record of her personal and psychological make up”.

“… tales of secret, legendary tortures evoking the ghosts of wives who had been cloistered or poisoned, who had disappeared without trace, ghosts who seemed to mingle with this group of living women, subtly goading them into ideas of revenge which, with the smell of the turpentine, made their nostrils flare. From time to time, very rapid, harsh glances were darted towards the model and passed beyond him, glittering. Then the women would turn their back on him, make a show of suddenly and affectionately remembering the artist and her painting, crowding around to note its progress, to admire it in their own way: ‘The sheet looks like silk: was Holofernes a prince?’ ‘Blood from the throat is darker than that’ ‘Is that how you hold a dagger?’ ‘I wouldn’t be able to stick it in’ “I would’ ‘I’d love to try’. ‘All that blood…’ They always came back to the blood that Artemisia was painting, a carnage woven, drop by drop like embroidery on the white linen”.

“Even if Artemisia intended her canvas as a personal vendetta against Tassi, the mood with which she infused it is barely distinguishable from that of Caravaggio’s picture. The goriness and violence are similar, as is the distaste for the task shown by the two Judiths. In both, a feeling akin to sadness is combined with a finicky fear of dirtying one’s clothes”.

“In her painting, Susanna and the Elders, she represented the people who harried her. The head of one of the two men which, earlier, Orazio had mercilessly obliterated, would now wear Agostino Tassi’s fine dark curls. Faceless, his eyes hidden, he merged into the other figure, that of an older man–perhaps Cosimo Quorli. Or maybe the grey hair, straight nose and sharply angled eyebrow evoked another likeness: that of Orazio Gentileschi.”.

“Its biblical basis is the story of a political execution carried out by a widow who puts herself at risk in the camp of the besieging enemy in order to kill the general, and thus to dishearten his troops and liberate her people from a deadly siege which her slain enemy has mounted”.

“The painting Judith is not about revenge. Yet it is about killing. But it is a metaphor, a representation in which the literalness of killing a man is displaced on to a mytheme wherein the action is necessary, politically justified, not personally motivated”.

3. The Contemporary Faces of Artemisia

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Italian: “a female painter”. |

| 2 | The allegorical description of La Pittura (Painting) provided by Ripa opens with the following lines: ‘’Donna bella, con capelli neri et grossi, sparsi et ritorti in diverse maniere, con le ciglia inarcate che mostrino pensieri fantastichi, si cuopra la bocca con una fascia ligata dietro a gli orecchi, con una catena d’oro al collo, dalla quale penda una maschera et habbia scritto nella fronte ‘imitatio’.” (Ripa [1593] 1764). Reynolds in her article dedicated to Artemisia’s self-portraits provides the English translation of the above-quoted fragment: ”A beautiful woman, with full black hair, dishevelled, and twisted in various ways, with arched eyebrows that show imaginative thought, the mouth covered with a cloth tied behind her ears, with a chain of gold at her throat from which hangs a mask, and has written in front ‘imitation’.” (after: Reynolds 2016, p. 178). As the author comments: ”Although in her self-portrait Gentileschi leaves out the gagged mouth (symbolising that the painting is dumb), the artist’s dishevelled hair (representing the divine frenzy of artistic creation) and the chain around her neck, from which hangs the mask of imitation, both echo Ripa’s description.” (Reynolds 2016, p. 178). It is worth adding that Mary D. Garrard, in her study on body language, in particular, the “signature postures” characteristic of Gentileschi’s paintings, in a very intersting way analyzes hand movements (especially so called: dotta mano, that is: “learned hand” motif) depicted in another Allegory of Painting (c. 1630, the collection of Galleria d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini) attributed to Artemisia (Mary D. Garrard 2006, pp. 27–28). |

| 3 | Another allegorical work consistent with Ripa’s description, worth mentioning here, is a medal honouring the great Bolognese artist Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614). (Schaefer 1984) The medal was designed by Felice Antonio Casoni and struck in 1611. It is now in the British Museum. At the time of Artemisia Gentileschi’s artistic debut, Fontana was already highly esteemed as a female painter, referred to as ’Pictrix’ in the Latin inscription on the aforementioned medal. |

| 4 | Please note that in this article, I am referring to the Grove Press edition of 2001 (Lapierre [1998] 2001), while the first edition in French was published by Éditions Robert Laffont (Alexandra Lapierre [1998] 2001). |

| 5 | In the Appendix to her novel (to its part II. titled Judith), Lapierre provides additional notes: “I have made a point of letting the magistrates, the witnesses and the defendants speak exactly as they did nearly four hundred years ago. I have merely clarified the circumstances as necessary, and put them into their historical and legal context (…) I had the proceedings of Tassi’s 1612 trial on charges of rape and procurement running through my head day and night. Although substantial extracts have been published by Eva Menzio in her outstanding edition, I felt it was important to go back to the original, and to transcribe and retranslate the whole document.” (Lapierre [1998] 2001, p. 386). See also: (Eva Menzio 1981). |

| 6 | Anna Banti also authored a three-act play inspired by Artemisia’s biography, titled Corte Savella (1960). It is discussed in Monica L. Streifer’s article on the “feminist intersections of painting and theater”. “In Corte Savella, Banti gives voice to one of the first women recognized in her own time as a master painter, a woman whose story was and often is misconstrued and whose art is often judged in light of the rape she suffered at the hands of her tutor.” (Streifer 2017, p. 1). |

| 7 | “She was the first woman to achieve a stature fully commensurate with her male counterparts. Her story of surviving rape and the public exposure of the trial, alongside scholars’ assertions that her paintings articulate a protofeminist viewpoint, have made her a modern feminist icon.” (Ffolliott 2021). |

| 8 | For example, in the preface to a comprehensive and engaging collective publication that explores the motif of rape in contemporary performing arts-featuring Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith on the cover-Maria Anita Stefanelli discusses art as a form of self-therapy and touches on the mechanism of cathartic compensation: “As a gifted independent female artist with a painful past, that she strove to fully acknowledge, and, above all, to come to terms with, Gentileschi’s painterly skills undoubtedly helped to heal her wounds. With the basic principles and mechanisms of spatial arrangement that she had to acquire in order to become a painter, she might also have absorbed, from Judith, the strength that she needed to maintain the struggle. Indeed, she did activate those principles and mechanisms of spatial arrangement; she did obtain the power to overcome the violence that she had experienced; she did become a model for other women: a model, if not the model. A woman who tried hard, at her own expense, not to be overcome by circumstances–and to live, if not happily ever after, then at least with her personal dignity intact” (Stefanelli 2016, p. 11). |

| 9 | An outline of the abundance of scientific studies dedicated to Artemisia Gentileschi would exceed the scope of this article. The reader is referred to several recent monographs: (see: Barker 2017; Locker 2015; Baldassari 2016). |

| 10 | Caravaggio, directed by Derek Jarman, Great Britain 1986. |

| 11 | Italian: “masterpieces”. |

| 12 | In his famous Vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori, (published in Florence, first in 1550, and subsequently in 1568), Giorgio Vasari dedicated a separate chapter to a Bolognese sculptor, Properzia de Rossi (ca. 1490–1530). Vasari describes her as giovane virtuosa (“young female virtuoso”; Vasari 1568, p. 172). In the context of biography-oriented approaches to women’s art, it is particularly interesting to consider de Rossi’s relief depicting the biblical scene of The Temptation of Joseph by the Wife of Potiphar (Museo di San Petronio, Bologna). Vasari (1568, p. 173) suggests that this work may have been a reflection, or projection, of Prudenzia’s unhappy love affair. (see: Vasari 1568, p. 173). |

| 13 | Typical comments on “Gentileschi’s revenge” are as follows: “The rape, and the desire to avenge herself, were a parallel to what we know was the inspiration for so many paintings by the extraordinary Baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi. She didn’t actually murder the man who violated her, but she turned the horror of her own life into scenes of women’s vengeance on the men at whose hands they had suffered. She used biblical stories to portray, in exquisite paintings, her fury at the sexual violence she herself had endured.” (Jenni Murray 2018). The phrase: “the theatre of revenge” appears even on Christie’s website, in Andrew Graham-Dixon’s article published on the occasion of the first major Artemisia’s exhibition held at the National Gallery in London (primarily planned for 3 October 2020–24 January 2021). (Graham-Dixon 2020). Megan Nolan takes a different angle in her 2020 Art Review article titled Artemisia Gentileschi Is More Than a Revenge Fantasy: “It is understandable that long-time devotees of Artemisia’s work may be frustrated by a one-note perception of her in con-temporary media, where she is often experienced primarily as an angry woman whose career was a grand act of vengeance against her abuser. In recent years her painting Judith Beheading Holofernes (1612–13) has cropped up repeatedly to accompany writings about male violence against women–the figures serve as a sort of ancient relation to recent rape-revenge fantasies in films of wounded women turned mad with wrath (…). This is an overly–possibly even offensively–simplistic reading of Artemisia, but it isn’t necessary to instead completely ignore authorship and context. While it would be a travesty to reduce Artemisia to a victim of rape, it is not an insult to consider her particular life when it comes to how we read her work” (Nolan 2020). |

| 14 | In his article titled ‘Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why it Matters’, Jesse Locker sheds new light on the biblical context of her works, referring to her as a ‘religious painter’. Locker notes that while Artemisia is often associated with depictions of ‘powerful ancient heroines’, her oeuvre extends beyond this narrow categorisation. “So it is easy to forget that many of her works, even if not the most celebrated ones today, are religious paintings. In 1968, R. Ward Bissell even went so far as to suggest that the libertine Artemisia preferred to paint ‘scenes that did not require her to acknowledge the presence of Divinity’. But a significant number of the new discoveries suggest that she was famous in her own time to a large extent because of her treatment of traditional religious subjects”. (Locker 2021). Among these new discoveries there is a beautiful painting of Christ Blessing the Children (Sinite Parvulos) of 1626. See also: (Locker 2015). |

| 15 | In her commentary on palm gestures in Gentileschi’s Judith and Her Servant (ca. 1625, Institute of Arts, Detroit), Mary D. Garrard notes that: “This arresting gesture dramatizes not the women’s power, but their vulnerability. It’s a visual cry of alarm at a moment of danger”. (Garrard 2006, p. 6). |

| 16 | In his article on the mediatization of Marina Ambamović’s performances, Marcel Bleuler notes that: “It is a popular pattern in the mediatization of female artists to implicitly consider their artistic practice as a compensation strategy”. (Bleuler 2018, p. 141). |

| 17 | Latin: “a female painter”. |

| 18 | In his 1918 essay, Freud offers an interpretation of the biblical figure Judith. He argues that: “The taboo of virginity and something of its motivations has been depicted most powerfully of all in a well-known dramatic character, that of Judith in Hebbel’s tragedy Judith und Holofernes. Judith is one of those women whose virginity is protected by a taboo. Her first husband was paralyzed on the bridal night by a mysterious anxiety, and never again dared to touch her (…). When the Assyrian general is besieging her city, she conceives the plan of seducing him by her beauty and of destroying him, thus employing a patriotic motive to conceal a sexual one. After she has been deflowered by this powerful man, who boasts of his strength and ruthlessness, she finds the strength in her fury to strike off his head, and thus becomes the liberator of her people. Beheading is well-known to us as a symbolic substitute for castrating; Judith is accordingly the woman who castrates the man who has deflowered her, which was just the wish of the newly married woman expressed in the dream I reported.” (Freud [1918] 1957, p. 207) See also: (Abraham [1920] 1927). |

| 19 | A separate extended article has been devoted to the analysis of this psychoanalytic ‘bestiary’, its evolution, and its presence in contemporary fine arts. (Stępnik 2023). |

| 20 | Luciano Garbati, Medusa with the Head of Perseus, 2008, bronze. See, e.g.,: (Stępnik 2023; Julia Jacobs 2020). |

| 21 | In the context of motherhood motif in Gentileschi’s painting, see, e.g.,: Madonna and Child, attributed to Artemisia Gentileschi, ca. 1613–1614, Galleria Spada, Rome. |

| 22 | According to Gina Siciliano, it is necessary to conduct thorough historical research and avoid projecting contemporary perspectives onto historical figures. “The more I learned about 17th-century Europe, the more important it felt to convey this era politically and socially, which led to some wordy/text-heavy areas. But making a wordy graphic novel felt necessary in order to put Artemisia into context. Otherwise, we’re just projecting our own modern mindset onto her.” (after: Treves n.d.b). |

| 23 | In her 2001 book, Mary D. Garrard references her critics, including her polemics with Griselda Pollock, as she notes in the preface: “There have been three basic critiques of my Gentileschi studies, which come from several quarters and the most recently rehearsed by Griselda Pollock. First is that I read Artemisia’s art as simple autobiographical expression. Second is that I essentialize her into a timeless figure whose art represents monolithic and historically unchanging woman’s perspective. In fact these two alleged fallacies are in conflict (…)”. And, further in the text Garrard reckons that her main argument was that “biographical experience and metaphoric expression are historically and specifically–not universally or deterministically–conjoined in Artemisia’s art, an art that, in its radical departure from masculinist convention, not only may resonate for women in general but has demonstrably done so for many modern women.” (Mary D. Garrard 2001, p. xix). |

References

Filmography

Arte, a series directed by Takayuki Hamana, Japan 2020 (12 episodes).Artemisia, directed by Agnès Merlet, France/Germany/Italy 1997.Artemisia Gentileschi. Warrior Painter/Artemisia Gentileschi: pittrice guerriera, directed by Jordan River, Italy 2020.Secondary Sources

- Abraham, Karl. 1927. The Female Castration Complex. In Selected Papers of Karl Abraham. Translated by Douglas Bryan, and Alix Strachey. London: Hogarth Press, pp. 339–40. First published 1920. [Google Scholar]

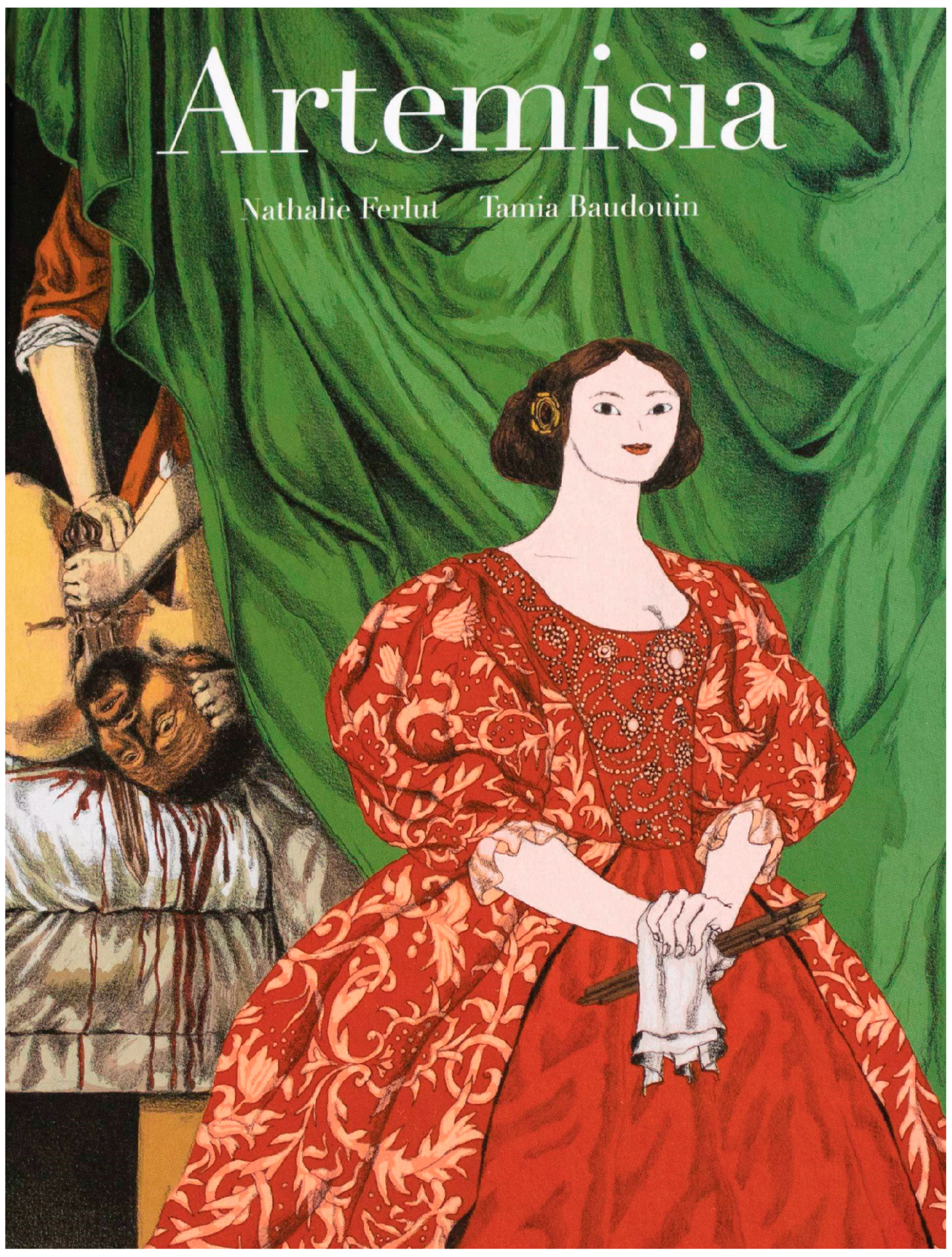

- Artemisia. 2021. A Graphic Novel Written by Nathalie Ferlut. Illustrated by Tamia Baudouin. Translated by Maëlle Doliveux, and Andrew Dubrov. Philadelphia: Beehive Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, Mieke. 1999. Quoting Caravaggio: Contemporary Art, Preposterous History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, Mieke, ed. 2006. The Artemisia Files: Artemisia Gentileschi for Feminists and Other Thinking People. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baldassari, Francesca, ed. 2016. Artemisia Gentileschi e il suo Tempo. Milan: Skira. [Google Scholar]

- Banti, Anna. 2004. Artemisia. Translated by Shirley D’Ardia Caracciolo. With an introduction by Susan Sontag. Lincoln: University of Nebraska. First published 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, Sheila, ed. 2017. Artemisia Gentileschi in a Changing Light. Turnhout: Harvey Miller. [Google Scholar]

- Barrington, Breeze. 2020. The trials and triumphs of Artemisia Gentileschi. Apollo. The International Art Magazine. April 25. Available online: https://www.apollo-magazine.com/artemisia-gentileschi-london/ (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Bazin, Germain. 1986. Histoire de l’histoire de l’art: De Vasari à nos jours. Paris: Albin Michel. [Google Scholar]

- Bleuler, Marcel. 2018. In Bed with Marina Abramović: Mediatizing Women’s Art as Personal Drama. In The Mediatization of the Artist. Edited by Rachel Esner and Sandra Kisters. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 131–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cavazzini, Partizia. 2001. Artemisia in Her Father’s House. In Orazio and Artemsia Gentileschi. Edited by Keith Christiansen and Judith Walker Mann. New Haven: Yale University Press, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 282–95. [Google Scholar]

- Cixous, Hélène. 2003. The Laugh of Medusa, (fragment). In The Medusa Reader. Translated by Keith Cohen, and Paula Cohen. Edited by Marjorie B. Garber and Nancy J. Vickers. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 133–34. First published 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Elizabeth S. 2000. The Trials of Artemisia Gentileschi: A Rape as History. The Sixteenth Century Journal 31: 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, Barbara. 2007. The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. London and New York: Routledge. First published 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ffolliott, Sheila. 2021. Oxford Bibliographies entry: Artemisia Gentileschi. Published on 24 February 2021. Available online: https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199920105/obo-9780199920105-0164.xml (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Freud, Sigmund. 1957. The Taboo of Virginity. In The Standard Edition of the Complete Works of Sigmund Freud. Edited and Translated by James Strachey. In collaboration with Anna Freud. London: Hogarth Press, vol. XI, pp. 191–208. First published 1918. [Google Scholar]

- Garrard, Mary D. 1980. Artemisia Gentileschi’s Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting. The Art Bulletin 62: 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrard, Mary D. 2001. Artemisia Gentileschi around 1622: The Shaping and Reshaping of an Artistic Identity. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garrard, Mary D. 2006. Artemisia’s Hand. In The Artemisia Files: Artemisia Gentileschi for Feminists and Other Thinking People. Edited by Mieke Bal. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Dixon, Andrew. 2020. Artemisia Gentileschi and the Theatre of Revenge. Christie’s com. Available online: https://www.christies.com/en/stories/artemisia-gentileschi-and-the-theatre-of-revenge-04ebd7cce6284ee09b4a00369a062748 (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Irigaray, Luce. 1974. Speculum de l’autre Femme. Paris: Éditions de Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Julia. 2020. How a Medusa Sculpture From a Decade Ago Became #MeToo Art. The New York Times. October 13. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/13/arts/design/medusa-statue-manhattan.html (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- LaBarge, Emily. 2020. The blazing world. Artforum. December 18. Available online: https://www.artforum.com/slant/emily-labarge-on-the-art-of-artemisia-gentileschi-84635 (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Lapierre, Alexandra. 2001. Artemisia: A Novel. Translated by Liz Heron. New York: Grove Press. First published 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Locker, Jesse. 2015. Artemisia Gentileschi: The Language of Painting. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Locker, Jesse. 2021. Artemisia Gentileschi: What Wasn’t in the London Exhibition and Why It Matters. Art Herstory (blog). February 16. Available online: https://artherstory.net/artemisia-gentileschi-what-wasnt-in-the-london-exhibition-and-why-it-matters/ (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Longhi, Roberto. 1916. Gentileschi, padre e figlia. L’arte 19: 245–314. [Google Scholar]

- Longhi, Roberto. 1952. Il Caravaggio. Milan: Aldo Martello. [Google Scholar]

- Lyotard, Jean-François. 1979. La Condition Postmoderne: Rapport sur le Savoir. Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Menzio, Eva. 1981. Artemisia Gentileschi/ Agostino Tassi: Atti di un Processo per Stupro. Milano: Edizioni delle donne. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, Jenni. 2018. The Vengeance of Artemisia Gentileschi. The Renaissance Era Painter Had Her Share of #MeToo Moments. Literary Hub. October 12. Available online: https://lithub.com/the-vengeance-of-artemisia-gentileschi/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Nolan, Megan. 2020. Artemisia Gentileschi Is More Than a Revenge Fantasy. Art Review. Published 20 October 2020. Available online: https://artreview.com/artemisia-gentileschi-is-more-than-a-revenge-fantasy/ (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Panofsky, Erwin. 1939. Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, Griselda. 1999. The Female Hero and the Making of a Feminist Canon. In Eadem, Differencing the Canon: Feminist Desire and the Writing of Art’s Histories. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 97–127. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, Griselda. 2006. Feminist Dilemmas with the Art/Life Problem. In The Artemisia Files: Artemisia Gentileschi for Feminists and Other Thinking People. Edited by Mieke Bal. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, pp. 169–206. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, Anna. 2016. Playing a Role. In Portrait of the Artist. Edited by Anna Reynolds, Lucy Peter and Martin Clayton. London: Royal Collection Trust, pp. 158–201. [Google Scholar]

- Ripa, Cesare. 1764. Iconologia. Perugia: Piergiovani Constantini, vol. 4, Archive.org. Available online: https://archive.org/details/iconologiadelcav04ripa/page/386/mode/2up?view=theater (accessed on 7 March 2023). First published 1593.

- Salomon, Nanette. 1991. The Art Historical Canon: Sins of Omission. In (En)gendering Knowledge: Feminists in Academe. Edited by Joan Hartmann and Ellen Messer-Davidow. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, Nanette. 2006. Judging Artemisia: A Baroque Woman in Modern Art History. In The Artemisia Files: Artemisia Gentileschi for Feminists and Other Thinking People. Edited by Mieke Bal. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, pp. 33–62. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, Jean O. 1984. A Note on the Iconography of a Medal of Lavinia Fontana. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 47: 232–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, Gina. 2019. I Know What I Am: The Life and Times of Artemisia Gentileschi. A graphic novel. Seattle: Fantagraphics. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanelli, Maria A. 2016. Preface: Spectacular Violence. In Performing Gender and Violence in Contemporary Transnational Contexts. Edited by Maria A. Stefanelli. Milan: Edizioni Universitarie di Lettere Economia Diritto, pp. 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Stępnik, Małgorzata. 2023. Sphinx and Gorgons: The Evolution of the Psychoanalytic Bestiary—Reinterpretations. Translated by J. Szelągiewicz. View. Theories and Practices of Visual Culture 35. Available online: https://www.pismowidok.org/en/archive/2023/visualising-psychoanalysis/sphinx-and-gorgons (accessed on 3 May 2023).

- Streifer, Monica L. 2017. Anna Banti Stages Artemisia Gentileschi: Feminist Intersections of Painting and Theater. California Italian Studies 7: 1–20. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9w95s8jq (accessed on 3 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Tabbat, David. 1991. The Eloquent Eye: Roberto Longhi and the Historical Criticism of Art. Differentia: Review of Italian Thought 5: 109–34. Available online: https://commons.library.stonybrook.edu/differentia/vol5/iss1/14 (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Tilford, Nicole. 2012. Susannah and Her Interpreters. In Women’s Bible Commentary. Edited by Carol A. Newsom and Sharon H. Ringe. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, pp. 432–35. [Google Scholar]

- Treves, Letizia. n.d.a. Artemisia in Her Own Words. Available online: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/past/artemisia/artemisia-in-her-own-words (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Treves, Letizia. n.d.b. Artemisia in Ballpoint Pen: Gina Siciliano and Letizia Treves in Conversation. Available online: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/exhibitions/past/artemisia/in-conversation-gina-siciliano-and-letizia-treves (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Vasari, Giorgio. 1568. Vita di M[adonna] Prudenzia de Rossi, Scultrice Bolognese in Idem, Vite de’ più eccellenti Pittori, Scultori e Architettori. Florence: Giunti, pp. 171–74. Available online: https://books.google.pl/books?redir_esc=y&hl=it&id=ePjZX3bHDJYC&q=virtuosa#v=onepage&q=properzia%20de%20rossi&f=false (accessed on 5 November 2023).

- Vreeland, Susan. 2002. The Passion of Artemisia. New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stępnik, M. “Grand Narratives” and “Personal Dramas”: (Re)reading the Masterpieces by Artemisia Gentileschi. Arts 2024, 13, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020043

Stępnik M. “Grand Narratives” and “Personal Dramas”: (Re)reading the Masterpieces by Artemisia Gentileschi. Arts. 2024; 13(2):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020043

Chicago/Turabian StyleStępnik, Małgorzata. 2024. "“Grand Narratives” and “Personal Dramas”: (Re)reading the Masterpieces by Artemisia Gentileschi" Arts 13, no. 2: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020043

APA StyleStępnik, M. (2024). “Grand Narratives” and “Personal Dramas”: (Re)reading the Masterpieces by Artemisia Gentileschi. Arts, 13(2), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts13020043