Abstract

In this article, I analyse how the COVID-19 crisis crystalised and fuelled the vigorous role of Amazonian indigenous artists as, what I call, “agents of interface”, enabling connectivity, translation, networking and bridging information, ontologies, claims, and aesthetics. With the pandemic’s spatial restrictions and the reduction of global activity in the arts with a return to focusing on the local, I argue that it is important to look at interfaces as arenas from which to understand further reconfigurations, actions, and values in the arts. Based on the project and exhibition Ite!/Neno!/Here!: Responses to COVID-19 co-curated by the indigenous artist Rember Yahuarcani and me, and on other various initiatives, this paper explores how Amazonian indigenous artists became crucial agents of the interface in four main arenas providing first-hand, real-time information of the impact of COVID-19 at Amazonian urban and rural settings, channelling networks of aid and curation, connecting different agents and worlds, and engaging in curatorial collaborations. I argue that by acting at the interface, artists have reinforced their voices, while pushing for redefinitions of and positions in the art system and suggest that the COVID-19 crisis has introduced a new moment in the configuration of Peru’s art scene.

Peru’s art scene was at the peak of its global visibility in 2019, with indigenous Amazonian art an asset in its transnational positioning. Then COVID-19 arrived, deflating Peru’s international mobility and spirit of celebration. Priorities changed in every domain of life, not excluding the art scene. This article traces the role of indigenous art and artists during the COVID-19 period and argues that this time of crisis crystallised their role as key multiscale political actors, mobilising indigenous claims and agendas and reinforcing networks of collaboration and curation. I contend that indigenous contemporary artists play a vigorous role as “agents of interface”, connecting and translating different spheres and collaborators, and redefining strategies, ways of working, and categories in the crossing. I also suggest that the COVID-19 crisis introduced a new moment in the configuration of Peru’s dominant art scene, and perhaps in the art scene at large.

1. Before COVID-19: 2019 and a Brief Genealogy

In 2019, Peru was invited as a guest country at the Madrid Contemporary Art Fair, ARCOmadrid. Peruvian artists, collectors, curators, museums, and art dealers saw this invitation to a major European art fair as the perfect opportunity to show the world Peru’s compelling art production and scene (see Borea 2021a). Peru’s ARCO organisers situated Indigenous art and people, particularly Amazonian art, at the centre of its publicity, narratives, and events. The Museo de Arte de Lima (MALI) organised the Amazonias exhibition featuring the work of both indigenous and non-indigenous contemporary artists in Madrid’s Matadero art space, which also included the participation of the Murui-Bora Brus Rubio as an artist in residence and the Shipibo artists Olinda Silvano and Silvia Ricopa with a mural, sponsored by Peru’s Ministry of Culture.

As I have explained elsewhere (Borea 2010, 2021a), two decades earlier, “indigenous art” was not related to notions of “the contemporary”: Andean art was linked to ideas of tradition and handicraft; and Amazonian art was not widely seen as art at all. Moreover, until the 2000s, the Amazon, in general, was not included in Peru’s national image, which was essentially represented by two regions, the coast and the Andes; the coast was linked to notions of progress and modernity, and the Andes, with its Inca legacy, to ideas about national roots and traditions. The Amazonian peoples and their art started to become visible in Lima from the 2000s onwards. However, as I have argued, the late visibility and mobility of Amazonian art and artists favoured their incorporation into Peru’s dominant art scene, in contrast to Andean artists and their art, which for decades have only circulated in the regime of the value of “arte popular”, and in a hierarchical relation to “art” (Borea 2017; Borea and Germaná 2008)—nevertheless, more recent changes are also taking place regarding Andean art such as with the work of Venuca Evanan and her networks of collaboration with different agents in the art scene such as art historian and curator Gabriela Germaná.

The redefinition of Peru’s art limits was favoured by a set of mainly local sociopolitical processes. By the 1980s, Amazonian indigenous leaders had organised themselves in organisations to defend their territory. By the end of the 1990s and 2000s, they were in the capital, Lima, claiming their rights and participating in the demonstrations against Alberto Fujimori’s ten-year dictatorial regime. This was a period of intense political participation and visibility for Amazonian leaders at Peru’s national level, and their claims also impacted the artistic arena. The end of Fujimori’s dictatorship in 2000 and the return to democracy led to a period of hope, social, and political renewal. It was a key moment that mobilised interculturality and citizenship agendas and will impact the art sector. Lima’s art circuit and society were in transformation, and Amazonian art began to circulate in this new landscape for the arts. A new group of art curators began to create more inclusive agendas, displaying Amazonian art in strategic venues in collaboration with Amazonian organisations.

Between 2000 and 2009, a series of exhibitions of Amazonian art took place in strategic spaces that gradually consolidated Amazonian art as part of Peru’s contemporary art scene (see Borea 2010, 2021a: Ch. 3). These changes were part of a local, national process: by 2010 Amazonian indigenous contemporary art was already consolidated in Peru at the level of exhibitions and narratives. Indigenous artists’ approach, media, and narratives transformed in response to their gradual involvement in the art scene, and their new inquiries and strategies. With their remarkable mobility across Peru’s territory, indigenous Amazonian artists have played an important role in the growing visibility of Amazonian art, pushing different limits of Peru’s contemporary art scene.

From 2013 onwards, within the context of Marca Peru, the nation’s branding campaign, and the new urban policies of Lima as a creative city with its mural programs, the Shipibo artists Olinda Silvano, Silvia Ricopa, and Wilma Maynas from the Cantagallo Shipibo community in Lima, developed mural techniques in initial collaboration with mestizo artist Alejandra Ballón—since then, their Shipibo Kené murals have achieved wide recognition. This moment intersected with a huge international interest in indigenous art. For example, the Tate opened its First Nations and Indigenous Art curatorial post in 2015; the indigenous artists and curators of the First Nations in Canada and Australia have had a strong influence in attracting this global attention to indigenous art.

Since 2015, the interest of leading museums worldwide in indigenous art, had a local impact on some of Peru’s leading museums, and curators who had not previously considered indigenous art have now begun to consider and promote it; for example, MALI opened its collection of Amazonian Art in 2015. It is this global interest in Amazonian art that located the Amazon at the centre of Peru’s image at Arco Madrid in 2019, and led the MALI to organise the Amazonias exhibition. But, as explained, there was already a long process for situating Amazonian indigenous art in the art circuit, in which indigenous artists were, and are, key agents in challenging limits and categorisations. Amazonias exhibition at ARCO attracted strong critique: indigenous artists not only wanted their work to be there, but they also wanted to be invited as artists with a more active presence; especially as the Amazon, in general, was so central to the programme. Moreover, despite the spotlight on the Amazon, indigenous Amazonian artists were participating in parallel events—outside the main art market space of ARCO (galleries were not representing them).

Paradoxically, this booming image of indigenous art, and particularly Shipibo art, in Madrid—promoted by private art agents and the government—has not found a correlation with improving indigenous living conditions. Indigenous art is promoted by powerful private agents and the Peruvian government today, but indigenous rights to a better quality of life and political voice are still very much neglected. Two months after the Shipibo artists participated in ARCO, Shipibo people who lived in Cantagallo in Lima, where the ARCO Shipibo muralists live, were demanding that the government fulfil its promises of relocation and housing. It was almost three years since a fire had burnt down Cantagallo, and the community was still dispersed. Some Shipibo people decided to go back to Cantagallo and rebuild it. Within a few months, COVID-19 would strongly affect this urban community when they were living in worse conditions than ever.

2. 2020: COVID-19, Global Deacceleration and Multiple Interfaces

COVID-19 caused a sharp break and the deflation of the booming Peruvian art scene. While it had an impact on the art sector worldwide (UNESCO 2021), in Peru, it put a stop to many art agents’ aspirations created by the global participation at ARCO Madrid. I have posited elsewhere that there were three periods in the making of Peru’s dominant contemporary art scene1. Here, I suggest that COVID-19 has initiated a new period with the strengthening of galleries run by young art dealers, a change in MALI’s management with a more local perspective, the end of Art Lima art fair, artists’ stronger self-representation via social media, and other factors that I will explain below.2 In addition, the art world’s growing interest in indigenous art and its ontologies in the art world was not going to stop, but the opposite. With the ecological crisis and the pandemic, at the hand of decolonial agendas and indigenous strategic actions in the already familiar field of the arts, Amazonian indigenous art would gain further attention and circulation.

But here, I explore something else: I argue that the COVID-19 pandemic crystallised the pivotal role of indigenous artists as what I call “agents of interface”. With their expertise in acting across communal, urban, national, and transnational arenas (Borea 2021a) and across worlds (Borea and Yahuarcani 2020) and as key political actors mobilising indigenous ontologies and agendas (Borea 2023), I suggest that indigenous artists have developed various capabilities and strategies for becoming agents of interface by creating and expanding communication, awareness, collaboration, and responsibility. Acting across multiscale arenas and at the interface has enabled them to produce and push for strategic redefinitions. I understand “agents of interface” to mean the actors who actively participate in, use, and create arenas for connection and interrelation, seeking to create communication across scales, times, and worlds (by listening seriously, exchanging ideas while making their voices heard, engaging with different aesthetics and synaesthetic communication, etc.), implementing forms of translation, redefinition, and collaboration, and being open to various sensory experiences with the aim to enhance real communication and empathic and caring relationships across worlds.3 In this article I present interfaces of various kinds, not only those related to virtual environments. As Whitehead and Coffield (2018) argue in their analysis of interface and gallery learning, interfaces are of various kinds that overlap, creating layers of engagement. For these authors, interfaces are physical and non-physical environments that make multidirectional, multidimensional, and multitemporal communication possible and enable transformation. They point out that “the structuring nature of the interface isn’t neutral” (2018: 242): interfaces can enable and disable certain communications, possibilities, and interactions. Addressing the non-neutrality of the interface, a paper by authors from different parts of the world, edited by De la Cadena and Lien (2015), explores the interfaces between anthropology and Science and Technology Studies, and highlights how location shapes the generation of interfaces.4 The language, places, and site of argument generate multiple heterogenous interfaces, which these authors explore as “sites of differences” (2015: 437).

This article draws on the positioned construction of interfaces, recognising its agents not as automatons, but as situated political actors seeking to create communication and dialogue. I suggest that indigenous Amazonian artists became agents of interface in four main arenas during the COVID-19 crisis, crystallising capabilities, networks, self-representation, and transformation. First, they provided first-hand and real-time information about the impacts of and responses to COVID-19 in both rural and urban communities and helped to voice indigenous claims. In doing so, they use social media, art, and exhibitions as sites of interface while pushing forward their self-representation. Second, they were key agents in reinforcing and channelling non-indigenous/indigenous aid and networks of curation where networks themselves became arenas of interface. Third, they offered a visual image and explanation of what COVID-19 is to them, bringing other sets of collaborators and interfacial connectivity across worlds to the fore. And fourth, they engaged in projects and platforms of collaborative curation, opening up arenas of co-designing among curators, engagement with audiences, and new positions within the art circuit. From their experiences of returning home in times of boundary re-makings, to connection across sites and worlds, and to the co-designing of platforms, indigenous contemporary artists play a vigorous role as “agents of interface”.

3. Changing Priorities with COVID-19: Life, Art, and Research Projects

Despite Peru’s indigenous artists’ growing visibility and recognition on the dominant art circuit, there were no indigenous curators, and the market was still precarious. Based on my previous research and long-term collaborations with some of the artists, I proposed the Amazonart project, which was granted a Marie Curie fellowship in 2019–2021.5 The project sought to understand the work, aesthetics, and agendas of indigenous Amazonian contemporary artists as they enter global art circuits and to produce curatorial narratives through a collaborative methodology with Amazonian artists responding to their aim of self-representation. COVID-19 hit the world just as the project was beginning. Life projects paused or changed. Research projects had to adapt quickly.6 I witnessed the artists I was working with re-focusing their work, thoughts, and practice on COVID-19. Through Amazonart, I worked with Rember Yahuarcani, Santiago Yahuarcani, and Harry Pinedo to put together the project HERE: Fighting COVID-19 and Inequalities, which won a grant from the University of York,7 securing them some funding at that difficult time.

The project became an arena for the exchange of information, feelings, and reflections about COVID-19. We communicated via WhatsApp, email, and Facebook, and met over Zoom several times, connecting the Amazonian town of Pebas and Lima in Peru and Norwich in the UK. We discussed Santiago Yahuarcani and Harry Pinedo’s work-in-progress, and the aims of the exhibition to come, where Rember Yahuarcani and I would act as curators. It was the first time Rember would embark on curatorship—I will return to this later. In the process of thinking about the COVID-19 project, two very clear issues emerged. First, the fact of survival. In our conversations, the word “survival” came up powerfully. Memories and fears from past situations resurfaced: previous experiences of epidemics, the rubber era, exploitation, contamination, and deaths. The importance of resistance and their knowledge was also active. Their need was to affirm that they were, are, and continue to be in this fight for survival. The title of the exhibition would highlight this: Here, here, here, in Uitoto, Shipibo, and English (or Spanish): Ite!/Neno!/Here!: Responses to COVID-19.

The other issue was where to hold the exhibition. The response was unanimous: in a commercial art gallery. On looking at the galleries that were still active during COVID-19, we thought that Crisis Gallery, recently created and with young administration, could be interested My colleague Mijail Mitrovic put me in contact with them, and Rember and I sent a proposal. The exhibition took place in November and December of 2020, pushing a step further in the positions already won in the art system by the indigenous artists, that is, in the field of indigenous curation and the market through gallery representation, as I discuss later.

4. The COVID-19 Emergency: Closing Borders and Going Further

With COVID-19 affecting the whole world, Peruvian authorities and Amazonian indigenous peoples expected huge morbidity in the indigenous Amazon due to decades of government negligence towards their communities, and failure to provide basic services such as running water, sewerage, and health care. Amazonian peoples began to prepare themselves to fight COVID-19 in a climate of anxiety and memory: memories of epidemics and genocides due to contacts, contagious, and exploitation (see Espinosa and Fabiano 2022). In this context, in April 2020, the Peruvian Amazonian Indigenous Association, AIDESEP, published an open letter to Peru’s President and several ministers:

“It is not known how many Amazonian indigenous people are infected, simply because our communities are ‘very far away.’ If the authorities do not get there, the ‘tests’ are even less likely to arrive; and the ‘government emergency bonus’ has been planned for urban realities.

We inform the world that the indigenous Amazon is in EMERGENCY and we have decided to close our communal borders in all our territories, given the advance of the threat […]

We request urgent action to prevent tragic consequences or even new ethnocides in some villages (especially those isolated and in initial contact); through the organisational, logistical, and institutional structure of AIDESEP [..]. No governmental entity knows our communities like we do, and even fewer have the logistics to reach them in a territory as wide and complex as the ten Amazon regions. It is time that the State joins forces with the indigenous organisations and does not repeat its delays and wasting of time, which today would be fatal”.8

However, the government did not employ the organisational capacity of AIDESEP, nor did it implement an intercultural approach to health (Pesantes and Gianella 2020). The emergency bonus mentioned in the letter did not initially reach Amazonian indigenous peoples, who were not included on the Ministries of Economy and Health’s lists of “people in poverty”. In Peru, the “issue” of Amazonian peoples is tackled by the Intercultural Section in the Ministry of Culture, encapsulating them in terms of culture. “Culture” can mask poverty, and if “interculturality” is only applied to cultural diversity, it can deny political action. Beyond the government’s dubitative responses, AIDESEP was clear: the borders were closing. To escape the threat of COVID-19, some people moved from their communities to other communities within their nation, but further from cities and river ports.

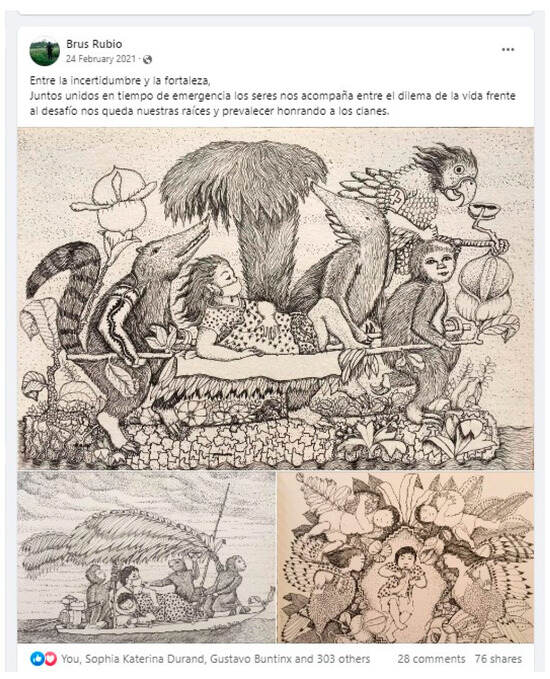

5. Returns: Artist Back and Rediscovery of Home

With the growing number of coronavirus cases in Lima and the indigenous organisations’ announcements that they were closing their communities’ borders, many indigenous and campesino (peasant) peoples who had migrated to Lima decided to go back, to put some distance between themselves and the city, and at least subsist, as work in the city was collapsing. Indigenous artists were no exception: two of the most important indigenous contemporary artists living in Lima returned to their hometowns in the Amazon. Rember Yahuarcani went back to Pebas and Brus Rubio to Pucaurquillo. Both artists witnessed and commented on the situation in the rural Amazon. Facebook was the platform par excellence. Artwork also became an ideal device for recording and reflecting on this time, as I explain and show in the following pages.9 Brus Rubio painted, drew, and posted a series of works reflecting on his people and the world during COVID-19. In one of his posts (Figure 1), he wrote “Together united in times of emergency, the beings accompany us in the dilemma of life, to face the challenge we have our roots and to continue honouring the clans”. The main drawing in the post shows an infected person being carried on a bed of healing plants by the animals/ancestors of each clan that comprises his community—the sloth, the parrot, the anteaters, and the ring-tailed coati—who are on top of a raft on the river. Brus belongs to the sloth clan, the animal that is at the far right of the composition, presiding over the procession. The animals–ancestors of the clans transport the sick person to their roots to gain wisdom and the physical and mental strength to recover.

Figure 1.

Brus Rubio’s post, Between uncertainty and strength, 2021. Source: Facebook. (Courtesy of the artist).

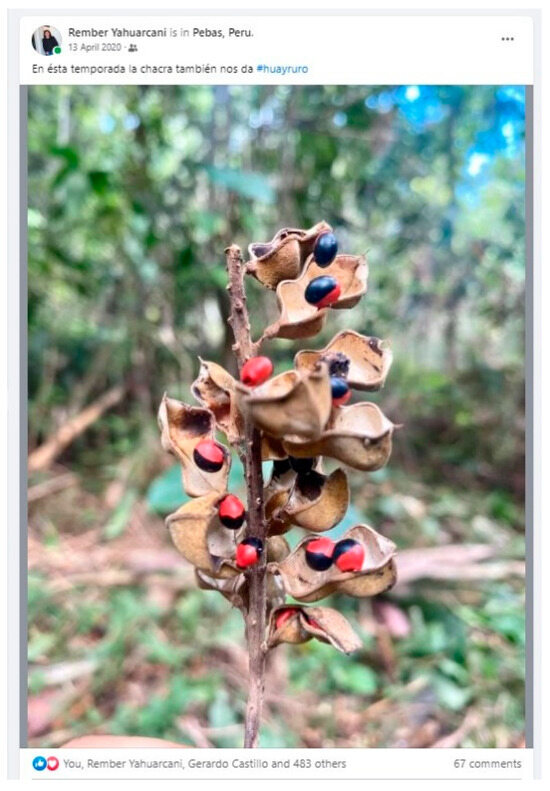

The return to the communities also meant the rediscovery of the Amazon—this time through the eyes and words of talented, recognised artists. For instance, Rember Yahuarcani embarked on photography, showing his followers on Facebook and Instagram the wonders of #Home (see Figure 2 and Figure 3), and wrote an article titled “Portraits of the pandemic: Painting and Photography from my parents’ Chacra”, explaining:

Figure 2.

Rember Yahuarcani’s Facebook posts from Pebas (“There are extraordinary beings” and “The chacra offers us Huayruros [seeds for good luck] in this period too”), 2020. Source: Facebook. (Courtesy of the artist).

Figure 3.

Rember Yahuarcani’s Facebook post from Pebas: “The chacra offers us Huayruros [seeds for good luck] in this period too”, 2020. Source: Facebook. (Courtesy of the artist).

“I am in Pebas. I have passed the entire quarantine of the pandemic here […] It has been a time to rediscover many things that had been left in second place due to my work in Lima and abroad. I continuously come to Pebas to visit the family and participate in daily activities […] But these five months that I have been here, they have allowed me to return with a lot of energy to those activities that had somehow been stopped by the painting. We have made fields, we have sown, we have grazed, we have laid down. It has been to return to activities that connect the indigenous with his world, right? … With the chacra, a bond of affection and love is created”.(Yahuarcani 2021, p. 217)

6. Crossing Borders: People and the Virus

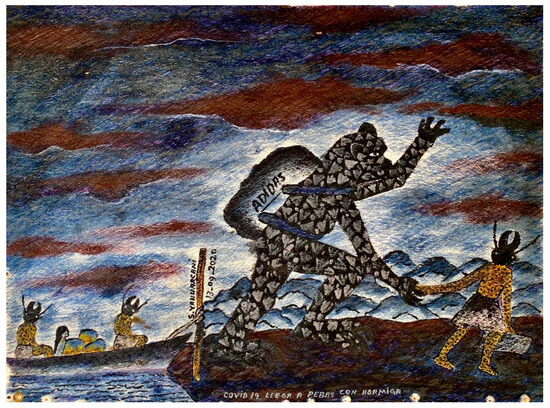

The aim was to close the community borders. But people needed to go to towns or cities to find a bank to collect the government’s emergency bonus. Others went to the city to collect their own money or to shop. With this crossing of borders, the virus reached various communities. In a form of protest, the artist Santiago Yahuarcani painted COVID-19 arrives in Pebas with Hormiga [ant] (see Figure 4; for more information about the COVID-19’s representation, see p. 14). In this work, Santiago Yahuarcani not only denounces the crossing of borders, but also refers to outsiders as a constant threat. He explains this work as follows:

Figure 4.

Santiago Yahuarcani, COVID-19 arrives in Pebas with Hormiga (ants), 2020. Natural dyes on bark (llanchama), 52 × 38 cm. (Courtesy of the artist).

“… there is a family here in Pebas that are called hormigas [ants]. They had the opportunity to leave at the time of the pandemic, to leave secretly to withdraw money they had in the bank. They were who brought the contagion, brought COVID-19. That is what I try to capture here in my work, because they were in a small boat, they were the whole family. And I try to show here that they are arriving, and with them, COVID-19 has come.

COVID-19 is coming. It has a backpack that says ‘Adidas’. He is coming from far away, from China, passing through Europe. So those who always come from there, from far away, from other continents, always come with this type of curse, of brand—that’s why I do that. And he is raising his hand, greeting the people. That is what I have tried to capture”.10

7. Fencing an Urban Community: Soldiers Create Borders

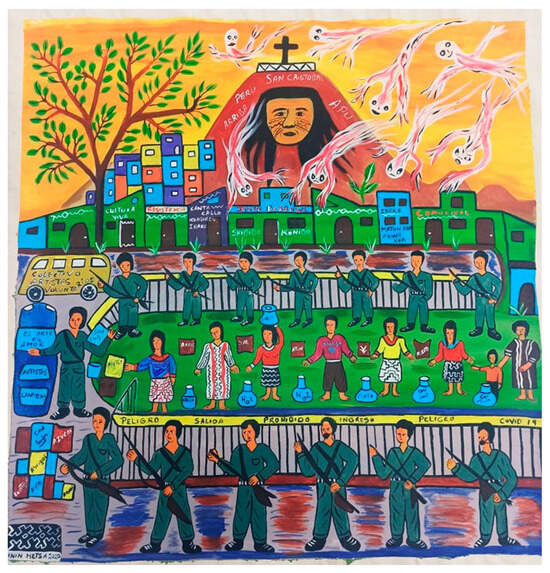

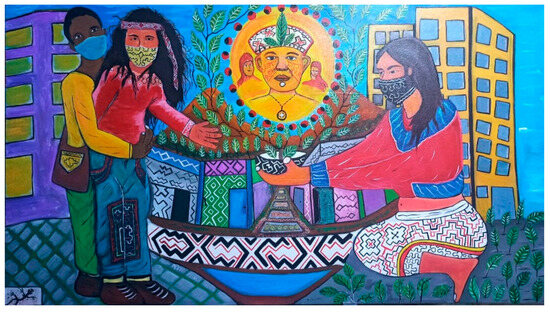

In Lima, the Shipibo Cantagallo urban community has been fighting for official recognition as an “indigenous community” in the city for more than 15 years. However, they have not been recognised, and instead, they have a turbulent story of place-making that includes a fire that destroyed Cantagallo in 2016, causing people to move to other vulnerable places while they were waiting for government aid, but at the end of 2019, they returned to Cantagallo to rebuild their community themselves. A few months before COVID-19 arrived in Lima, the Shipibo leaders had asked the government for portable toilets; the government refused. Cantagallo’s precarious conditions with limited running water and sewerage, located only a 20-minute walk from the Government Palace, directly promoted the rapid spread of the virus. This time, the government delivered a prompt and excessively repressive response: the police surrounded Cantagallo and closed the community with strict policing, blocking the Shipibos’ mobility while the rest of Lima was free to continue as normal. The government created a territorial boundary by strict policing, and not by policies of recognition (Borea 2021b, 2023). Surrounded by police, the Shipibo were supported by aid networks of friends, art agents, and religious groups, who brought food, clothing, and other help to the community. The artist Harry Pinedo captures the police blockade, the aid networks, and the Shipibo people’s understanding of COVID-19 as an airy being from the Yellow world, the world of diseases (Figure 5):

Figure 5.

Harry Pinedo-Inin Metsa, COVID-19 and the political repression, 2020. Acrylic on canvas, 110 × 80 cm. (Courtesy of the artist).

“This is a painting referring to what happened in the Cantagallo Shipibo community, which shows how in the first months of the year 2020 between April, May and June, the police surrounded us since 90% of us, the community, had positive Covid tests. For fear of contagion the police surrounded us, locked us up, and no one could leave or enter, only with permission from the authorities. Neither food. The state helped very little; more was done by the activists, the artists, the Christians, who came to our aid. But it was never the state. What the state, the government did, is send the police, send doctors to do rapid tests, but those tests were not so true […].

They already had their diagnosis that we were not going to resist the virus much. And that means that the police had very close surveillance of us so that we did not go out and infect the city of Lima, because here is the city centre. I have painted that experience so that the history of the struggle for the survival of the indigenous people who are in the capital becomes visible. And there is a struggle for territory, health, and education. And that is part of the problems that there were, and that I am expressing in this painting”.11

8. Interface 1: Self-Representation and Voice: Newspaper, Social Media, and Art

With mobility restrictions and insufficient governmental outreach, indigenous artists became key agents of connectivity. Over the last decade, indigenous artists’ national and transnational mobility equipped them with new skills for acting at different scales, attracting a wide network of agents in the cultural and other spheres. Their national and transnational experiences contributed to their position as key political actors with a strong voice. In times of crisis, indigenous Amazonian art and artists have become powerful agents, and are seen as legitimised actors, to express indigenous realities, claims, and anxieties, to explore and give visibility to local perspectives and responses to the crisis, and to attract and channel aid.

As an opinion columnist in the widely circulated newspaper El Comercio, Rember Yahuarcani wrote three articles related to the impact of COVID-19 in the Amazon.12 In one, he demands that the government and his community protect their eldest members, who were the most vulnerable to COVID-19 and who transmit the peoples’ mythology and knowledge. But more important than newspapers, social media, especially Facebook, became the main public sphere that allowed artists to communicate the situation, transcending frontiers and attracting wider interest, help, and solidarity. Posting their artworks, statements, and news, the artists played a powerful role as agents of the interface. When the Shipibo Cantagallo artist Olinda Silvano-Reshinjabe caught COVID, an immense group of social media followers sent her their best wishes. When the Minister of Culture visited her once she had recovered, Silvano told him:

“Go to the Ucayali, go to the Amazon, the biggest communities, also like us, are there. It would be the first time you set foot in the indigenous communities there, because no one has been there before. We as Shipibo artists have donated, with our art, and that is what we are sending, but it’s not enough: we need action from the state. I ask this on behalf of all artisan mothers”.

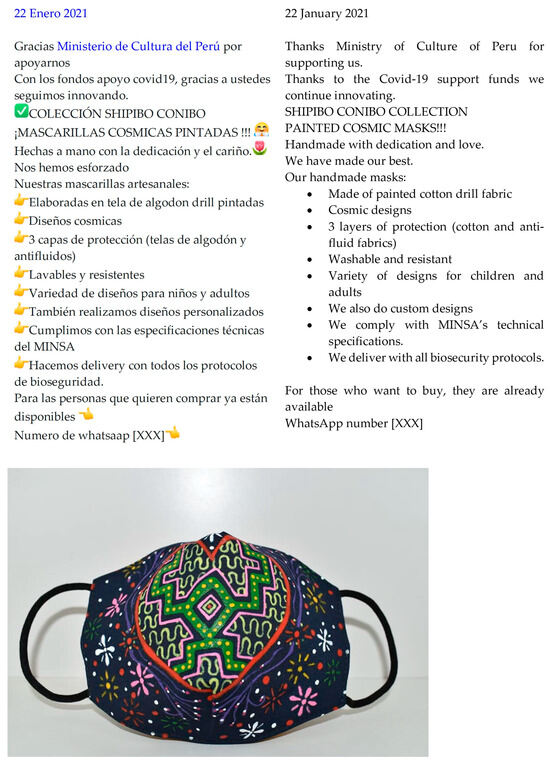

The video of what Olinda Silvano told the Minister circulated widely again. Another key interfacial agent was Olinda’s sister Sadith Silvano, an artist, artisan, designer, cultural manager, and communicator, who increased her activity on social media during these times, rapidly gaining experience in digital communication and becoming an icon of Shipibo entrepreneurship. Before COVID-19, her artistic production had focused on Shipibo fashion design, particularly adding Shipibo designs to garments. Her capacity for testing the market and experimentation led her to create facemasks with Shipibo designs—creativity and posting went hand in hand. These facemasks gained immediate acceptance, and their production extended to a group of “madres artesanas” (artisan mothers). Selling the facemasks gave the women an income and helped others in their urban and rural communities (Soca 2021), through family ties.13 They began offering online workshops teaching the traditional designs and their healing songs. The Shipibo-designed facemasks became an agent of creativity and resistance, protecting the wearer from the virus (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Sadith Silvano’s Facebook post and image, 22 January 2021 (translation mine). (Courtesy of the artist).

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, Marca Peru’s narratives and policies strongly impacted, and offered a discourse for, the positioning of Shipibo Cantagallo mural painting.14 Sadith Silvano also took this approach. Her social media posts, embedded in the Marca Peru narrative and with a strong logic of entrepreneurship, emphasized Shipibo’s creativity, community production, women’s power, and resistance during this time.15 Discourse and practice through entrepreneurship allow Sadith, Olinda Silvano, and other Shipibo Cantagallo agents to bypass—or rather merge—categories of art, artisan, and design and act simultaneously in different and across regimes of values.16 Their own voice in social media encompassing branding narratives, and an art production that offers art-healing-creativity tradition to an art system and cities that intend to reformulate in times of ecological and sanitary crisis have opened these artists other wider channels for the circulation of their art.

9. Interface 2: Networks and Aid: Indigenous–Non-Indigenous Networks for Curation

As Marisol de la Cadena and Orin Starn write “indigenous self-representation involves broad networks of collaboration that include peoples from many walks of life” (De la Cadena and Starn 2007, p. 21). Non-indigenous collaborators also raised awareness of the COVID-19′s impact on the Amazonian communities. For instance, the online posts of the anthropologist Luisa Elvira Belaúnde in LaMula.pe and the 2020 and 2021 editions of the open-access Mundo Amazónico journal edited by Luisa Elvira Belaúnde, Gilton Mendes, and Edgar Bolivar-Urueta were key publications to grasp and communicate the urgencies and responses in the Amazonian communities in real-time; there were many other online events and initiatives with indigenous and non-indigenous participation in support of the Amazonian peoples.

During the COVID pandemic, indigenous artists not only increased the visibility of how COVID-19 was locally experienced in the Amazonian rural and urban communities, but they also became strategic agents to attract and channel aid. Their larger participation in the art field, a result of a set of strategies of both indigenous and non-indigenous agents (Borea 2010, 2021a), provided them with a large network of connections and collaborators. Art and research networks became help and caring networks; for instance, For our wisemen and women was an initiative activated by Brus Rubio’s network that included the anthropologist Wilton Martínez, the Centre of Visual Anthropology, Rubio’s Selva Invisible gallery and its manager, the director of Curuwinsi Cine, Lupe Benites, and others. They created a virtual platform for exhibitions, ancestral performances, film screenings, music, and talks, asking for support of 30 soles per two people. The funds raised were used to support elderly people in Rubio´s community of Pucaurquillo and the surrounding villages. Rubio, who was in Pucaurquillo, distributed the fund. His already renowned art, activism, and public voice made people trust him and contribute to the initiative.

An initiative that had big success was Drawings for the Amazon. I argue that the new booming interest in indigeneity and the Amazon favoured the channelling of aid from non-indigenous art agents to the region –impacted by the high proportion of COVID-19 cases and precarious healthcare establishments. These initiatives allowed prominent art agents and curators who previously had little interest in the Amazon to establish themselves as agents and curators of “indigeneity” while they fostered solid groups of aid and at a time when indigenous art was gaining large global interest. The new networks became networks for curation, providing aid for curation from COVID-19 and the curation of COVID-19 in the art circuit, as I will explain later. Inspired by the Brazilian initiative 300 designs, Drawings for the Amazon was promoted by Miguel López, a renowned international Peruvian curator acting as a director of TEOR/ética in Costa Rica at the time, Christian Bendayán, a curator and artist who had long worked promoting Amazonian art, and the visual artists Eliana Otta and Juan Salas, among others. The voices of the Shipibo film director Ronald Suarez and the artist Olinda Silvano as well as that of the curator Miguel Lopez were repeatedly quoted to promote this initiative.17 The high profile of the art agents involved in organising and communicating the initiative favoured its success, leading to donations of 400 drawings from indigenous and non-indigenous artists within 10 days; these drawings were offered for sale on an online platform from 19 to 31 May 2020. Donors paid $150 and were randomly allocated one of the works. The aim was to raise US$ 60,000 to support the Apostolic Vicariate of Iquitos and Ucamara Radio, both in Loreto, and the Indigenous Asociation Coshikox in Ucayali—all institutions actively helped people during the pandemic.

Other networks of aid included Christian groups and the Catholic church. Other more silent networks included families and workers in long-term contact with the communities. Indigenous peoples also activated their own help and caring networks. For instance, faced with the shortage of goods for sale at local markets and avoiding contact with cities, communities reactivated the exchange of goods between themselves, by passing both the market and the city. Aid networks also bridged urban and rural communities, as in the case of “Comando Matico” (Matico Command).18 Matico is a plant whose leaves are traditionally used to heal bleeding, ulcers, respiratory and digestive problems, and other conditions. The success of matico leaves (Piper aduncum) in fighting COVID-19 in Ucayali communities encouraged young indigenous peoples to transport matico from the Shipibo communities in Amazonian Ucayali to Shipibo Cantagallo in coastal Lima. Comando Matico was created in Yarinacocha-Ucayali in May 2020 to save lives using plants (Belaunde 2020). It offered its services to indigenous and mestizo peoples in Yarinacocha and other parts of the country. As Pesantes and Gianella (2020) affirm, this initiative showed indigenous peoples’ capacity to implement intercultural initiatives when the government was unable to recognise the importance of indigenous traditional knowledge in the battle against COVID-19. As mentioned, indigenous peoples’ cultures and art are an asset to neoliberal cultural policies; however, indigenous rights to adequate services, to decide their project of life in their territory, or to gain real recognition of their knowledge and implementation of interculturality are not yet included in the government’s aims beyond its laws, narratives, and multicultural branding. Cantagallo Shipibo artist Harry Pinedo captures the various interfaces of help, well-being, and health in real time (see Figure 5 and Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Harry Pinedo/Inin Metsa, Sharing our Plants, 2020. Acrylic on canvas, 152 × 86 cm. (Courtesy of the artist).

10. Interface 3: Networks and Aid—Connecting with Other Beings and Breathing Again

Art practices also shone a light on other types of connections that became crucial in curing COVID-19 in the Amazon. Scientists around the world sought to understand the behaviour of the virus and find a cure. Scientific collaborations and the rapid circulation of knowledge were promoted. Politicians backed their actions with scientific data. Visualization techniques became key to the understanding of scientific knowledge and communicating it to society. Most of us became familiar with the image of COVID-19.

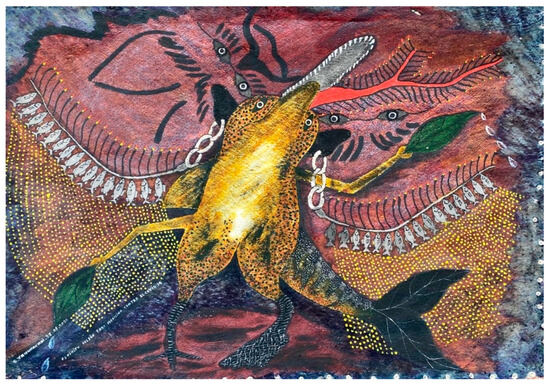

Shamans, who specialise in curing disease and observing and experimenting with plants in the Amazon, also sought to understand the disease and find a cure.The shamans entered in communication with the mothers (owners, spirits, guardians) of plants and animals located in different worlds—the worlds of the water, forest, and sky—asking for help to find the cure. As with all disease, the shamans needed to identify who COVID-19 was, which means that they needed to know who its mother was before they could “domesticate” the disease. Through dreams and “mareaciones” (state after ingested powerful plants or smoking tobacco), they visualized the owner of the coronavirus.19 The Uitoto artist Santiago Yahuarcani, explained to me:

“In conclusion, we have tried to find out who was the owner of the COVID-19. Every disease has an owner for us or a mother. That is where we detected that the mother, or the owner, of COVID-19 was a monster like a gorilla. And that is why I began to draw this being, this monster in my paintings.

The other COVID-19 is from other relatives who had Covid. When they were with a very high fever … in that delirium, they saw some men with hats, like these skinny men with hats, that began to suffocate people”.20

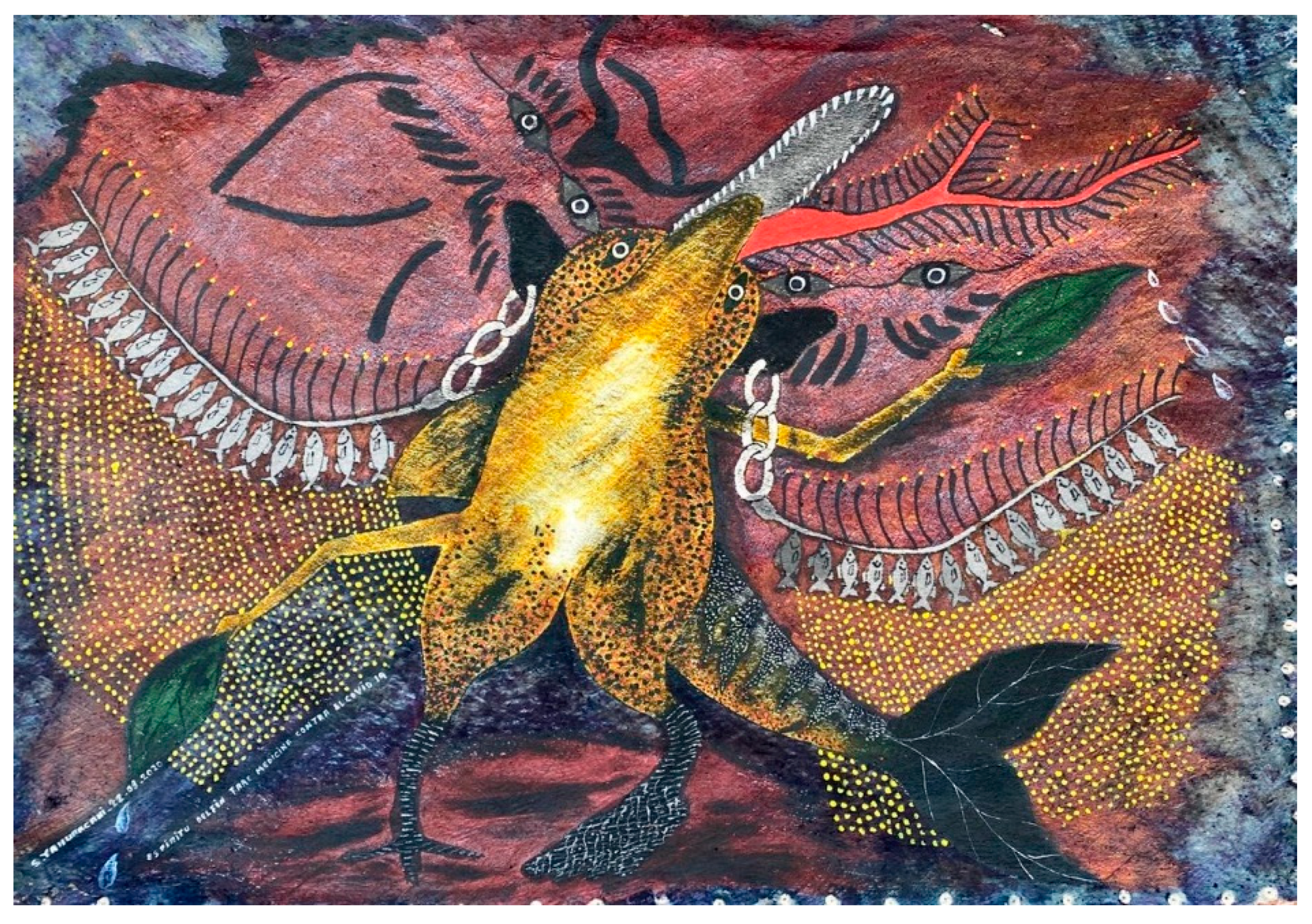

Santiago explained that COVID-19, in a monster-gorilla-like form, is the boss, and the skinny men silhouettes are his assistants who arrive at the time of high fever. COVID-19 was fought using a series of plants. For the Uitoto, the ajo sacha or sacha ajo was the most powerful plant, which was helped by other leaves such as lemon, ginger, star apple, and toe. The mother or spirit of the Dolphin had a leading role in highlighting the use of ajo sacha to Yahuarcani’s family network and other Uitoto people. Talking about his painting, Santiago explained (Figure 8) to me: “This spirit is the most powerful one, who has worked during this pandemic, because he has been the spirit that has tried to seek, to choose, to know the strongest medicine that in this case has come to be the ajo sacha”.

Figure 8.

Santiago Yahuarcani, Spirit of the Dolphin brings medicines against COVID-19, 2020. Natural dyes on llanchama, 98 × 69 cm. (Courtesy of the artist).

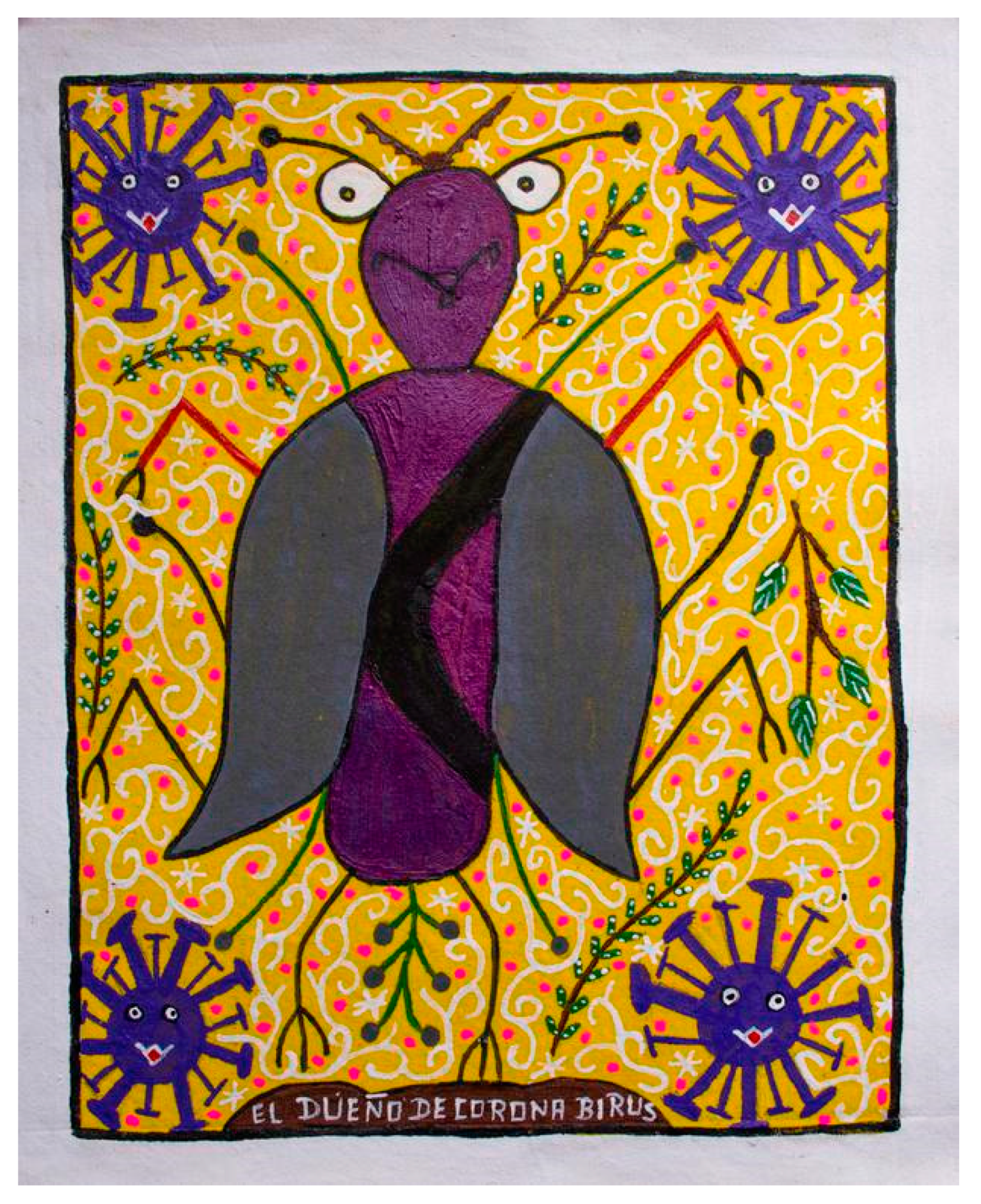

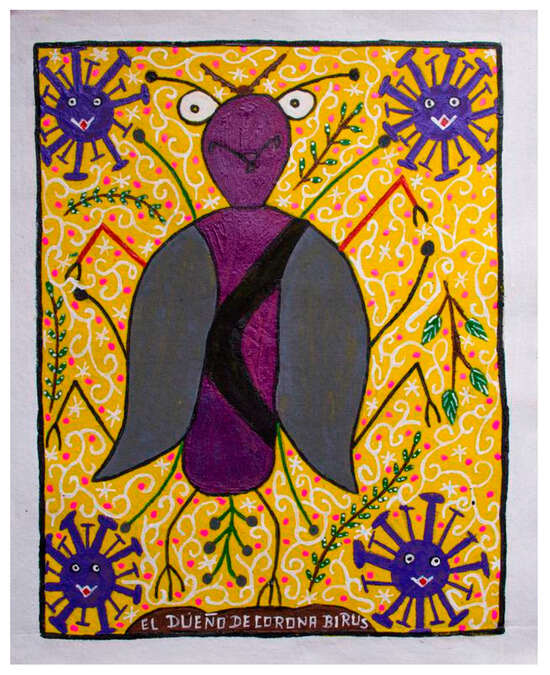

After catching COVID-19, the Shipibo artist Lastenia Canayo–Pecon Quena wanted to have a dream that let her see what COVID-19 was. Her artistic work focused on the materialisation of the ibos (owner, guardians, mother, spirits) of animals, plants, and other beings. She said: “I told my son, I want to see how the virus enters our mouth, our nose—I want to dream about it” (Santos and Díaz 2021). The Owner of Coronabirus (Figure 9) was a result of that dream: “There come glowing spirits like flies that stick towards us. But they are not flies, but the owner of the disease”. (ibid.) Lastenia Canayo has made subsequent versions of this work, as the making of various versions of the same work is part of her artistic practice.21 She has also materialised the owner of matico, the main plant that helped Shipibo people to save their lives and let them breathe again. As scientific visualisation techniques offered an image of COVID-19, indigenous art practices offered an image of the mother of COVID-19 and its cure based on indigenous shamans and artists’ interfacial synaesthetic encounters with other beings, and their power, knowledge, and care.

Figure 9.

Lastenia Canayo/Pecon Quena, The Owner of Coronabirus, 2020. Acrylic on canvas 42 × 34 cm. Christian Bendayán Collection. (Courtesy Christian Bendayán).

11. Interface 4: Exhibitions, Curatorial Collaborations and Self-Representation

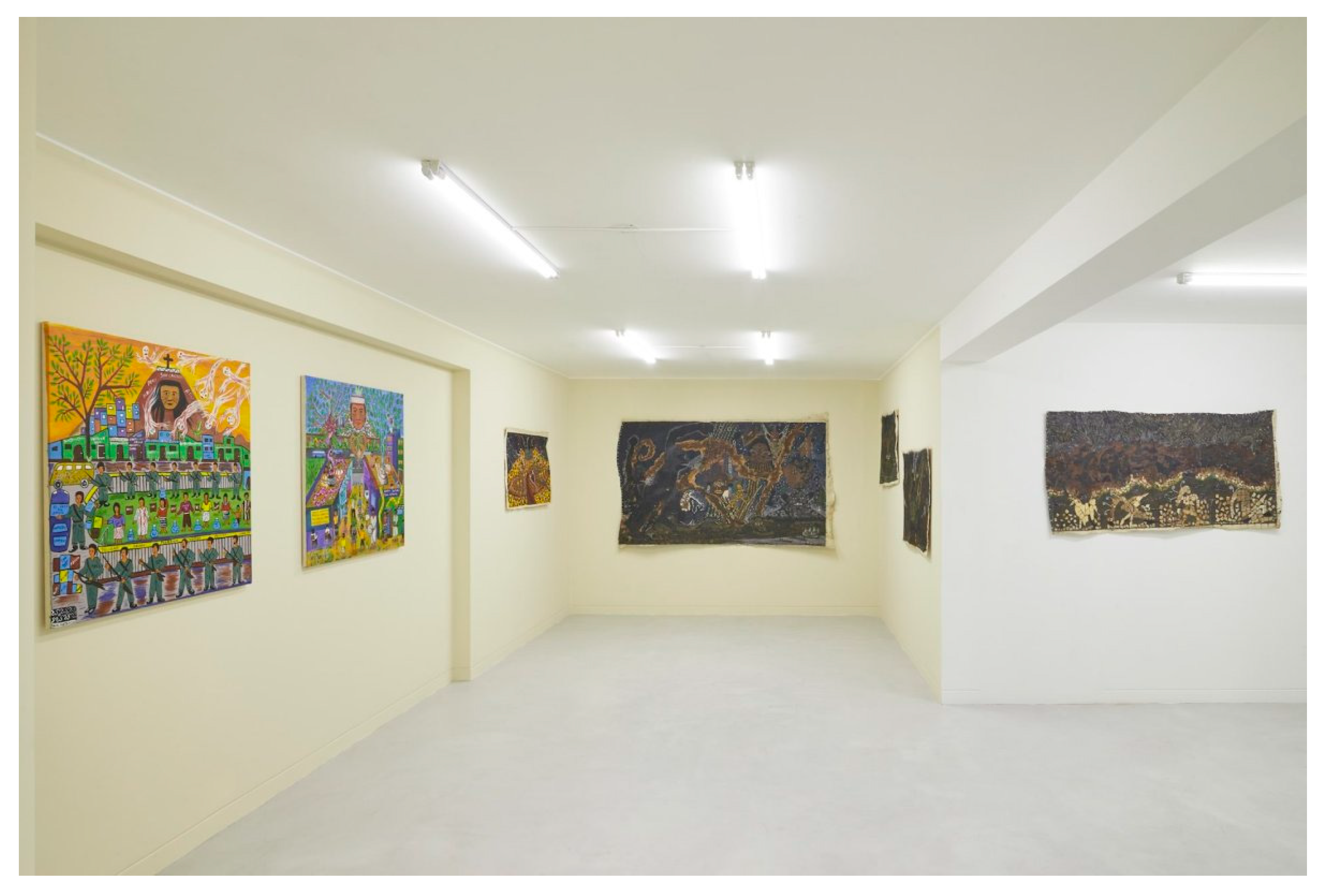

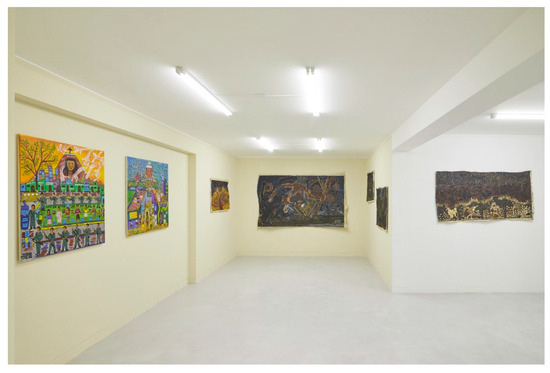

My collaboration with Rember Yahuarcani started in 2009 when David Flores-Hora and I curated the exhibition Once Lunas (Pancho Fierro Gallery, 2009), showing works about the Uitoto calendar by Rember and his father Santiago Yahuarcani. More recently, Rember and I have started to reflect actively on this long-term collaboration, expanding our collaboration from art-based projects to co-authorship. In 2020, the first text we had written together was published. In it, we discussed what rivers are for Amazonian peoples, and how art elucidates the water world that is endangered by capitalist extractive projects (Borea and Yahuarcani 2020). In this chapter, we also reflected in our joint voice—the “we” in the chapter—highlighting a non-neutral but positioned “we”, and what we called later a “bumpy we”. In addition to being an artist, Rember is a writer and columnist for Peru’s main newspaper. With the collaborative approach to the Amazonart project and awareness of the lack of an indigenous curatorial voice in Peru (see the first section of this article), I proposed to Rember that we embark on curating together in response to the urgency of COVID-19. The project offered a real-time platform to reflect, with caring, on what was happening to the indigenous peoples, particularly the Uitoto and the Cantagallo Shipibo peoples, and our well-being in general during the pandemic (Borea 2022). The artworks and exhibition became interfaces with a larger Lima audience on how COVID-19 was being experienced and was being fought back using indigenous Amazonian knowledge with the help of a broad set of collaborators (see pp. 4–5 and Figure 10). The exhibition also created other levels of interface with a larger community through an online event and information.

Figure 10.

Ite!/Neno!/Here!: Responses to COVID-19, 2020. Photo: Juan Pablo Murrugarra. Crisis Gallery. https://crisis.pe/en/exposiciones/ite-neno-here, accessed on 15 June 2023. (Courtesy of the curators).

Ite!/Neno!/Here! became the first exhibition on Peru’s mainstream art circuit to be co-curated by an indigenous person.22 Curating this show together became a learning platform for Rember into curatorial practice and offered me an important third space for curating research. We were invited to events to talk about our experience, and Rember wrote a column in the newspaper El Comercio, reflecting on indigenous curation. In November 2022, at the new Martín Yepez gallery, he put together his first exhibition, NUIO: Back to Origins, as a sole curator, opening new pathways of indigenous self-representation.23 It is important to mention that while the consolidation of Amazonian indigenous art occurred later in Brazil’s art institutions than it did in Peru, indigenous curation grew faster and more strongly from 2017 onwards. For instance, there is the curatorial work of educator and curator Sandra Benites, who was the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP)’s first indigenous curator (2019–2021); of the educator, art historian, and curator Naine Terena, curator of e.g., Véxoa: We Know (Pinacoteca de Sao Paulo, 2020–2021); and of the artists and curators Denilson Baniwa and Jaider Esbell (who died in 2021).

Ite!/Neno!/Here! also played an important role in the art market, as the Crisis gallery started to represent Santiago Yahuarcani. Before this, only the Andean artist Venuca Evanán had had gallery representation—in the Ginsberg gallery—which has ended.24 Santiago Yahuarcani’s work began to circulate at art fairs such as Arco Madrid 2022, with immediate impact: the leading Spanish Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía bought his work, followed by acquisitions of other museums and global participation in an art scene that is regaining its “global” work after COVID-19; hopefully having learned lessons and redefinitions from the times of COVID-19 crisis.

A month after the exhibition Ite!/Neno!/Here!, the exhibition Visual resistance: Aesthetics of a new citizenship (Figure 11) curated by the art historian María Eugenia Yllia and the Murui-Bora artist Brus Rubio, was launched at the Metropolitan Museum of Lima. The curatorial collaboration between Yllia, a key art historian and curator of Peruvian Amazonian art, and the renowned artist and gallery director Brus Rubio was also based on a long-term work. Visual resistance focused on the active role of art in the consolidation of citizenship and the revitalization of diverse knowledge. In November 2022, and with a recent work with indigenous Amazonian artists, the curator Miguel López, in collaboration with the curator and artist Gala Berger and the Shipibo artist and activist Olinda Silvano, launched the exhibition Mother Plants and Struggling Women. Visions from Cantagallo (Figure 12) at the Lima Museum of Contemporary Art as part of their Common Thread project; this was supported by the INSITE Commonplaces curatorial platform. Between mid-2021 and early 2022, the project offered the women of the collective Shinan Imabo (Non Shinanbo-Our Inspiration, created in 2020) a platform for thinking and producing work about their recent experiences of and responses to COVID-19. A selection of this work was shown and an online journal (INSITE Journal 2023) with a series of interviews, texts, and artworks was also launched.

Figure 11.

Visual resistance: Aesthetics of a new citizenship, 2021. Metropolitan Museum of Lima. Facebook. (Courtesy of the curators).

Figure 12.

Mother Plants and Struggling Women. Visions from Cantagallo exhibition, 2022. MAC-Lima. Commissioned by INSITE Commonplaces. MAC-Lima. Photo: Philipp Scholz Rittermann. Insite—Exhibition (insiteart.org). (Courtesy of INSITE).

What I want to highlight here is that during the COVID pandemic, Peru’s Amazonian indigenous agents gained a new position in the art circuit: that of curatorship. The emergence of curatorial collaborations during and since the pandemic not only shows the limitations of curatorship coming only from white mestizo curatorial voices but signals the potential of co-designing and the strengthening of indigenous self-representation not only through artmaking but also through curatorial activity and value making.

12. Final Notes: On the Interface and Art

In this article, I have shown how the COVID-19 crisis crystalised and fuelled the vigorous role of indigenous artists as agents of interface, enabling connectivity, translation, networking and bridging information, ontologies, claims, and aesthetics. With the pandemic’s spatial restrictions, the slowdown of acting globally in the arts, and a return to focusing on the local, I have suggested that it is important to look at the multiple virtual, material, and non-visible interfaces as arenas from which to understand further redefinitions, actions, and values in the art system, and bring attention to the voices, agendas, aesthetics, and strategies of the different agents that activate and participate in them. I have highlighted how the artworks of indigenous artists, their media and social media posts, their networks with other humans and with those of extended humanity,25 and their curatorial collaborations allowed them to bring information, anxieties, and responses of indigenous peoples to COVID-19 into the larger public space and to channel aid and caring into the communities. Acting at the interface, artists have reinforced their own voices and tuned them for a wider audience while pushing for further redefinition of the arts, and its regimes of values, roles, and categories. As I have explained, led by Marca País, an entrepreneurial narrative, Shipibo Cantagallo artists embarked on a more fluid self-definition across regimes of values in the arts. While this had begun before the onset of COVID-19, the strength of self-representation on social media and virtual communication fuelled this redefinition, while other artists and new curators—such as Rember Yahuarcani—reinforced and mobilised categories of “indigenous contemporary art”.

I have discussed the powerful networks of curation that the artists attracted, which calls for a wider understanding of collaborators in the art worlds (Becker 1982) to include networks that cross worlds and mutually connect humans and extended humanity. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic brought time to rethink ways of doing things, to experiment and work together in an atmosphere of caring, which, with indigenous artists’ strong strategies for self-representation, favoured the co-design of exhibitions with curatorial collaborations. These collaborations provided experience and tools for further curatorial activity, expanding the roles Peruvian indigenous agents took on in the art system. Further insight into what it means to act and think through interfaces is necessary. More thinking on and through the interface could allow indigenous and non-indigenous peoples—and other kinds of agents—to co-design better arenas for communication, dialogue, translation, and real collaboration among different actors that might create more solid and fairer transformations.

COVID-19´s spatial restrictions, and the government´s abandonment of its provision of adequate services to communities “afar”, were overcome through multiple actions of connectivity and translation. At the beginning of 2021, many Amazonian indigenous peoples were already referring to COVID-19 as something of the past, vanquished by their ancestors and local plants, and the Amazonian indigenous agents with whom I have worked have pointed out that although COVID-19 caused several deaths, it was not as devastating as projected. Indigenous knowledge and a vast network of collaborators helped indigenous communities to survive, despite the failure of governmental health services in the area. The role of indigenous artists was crucial during the pandemic, and their activity also pushed the limits and roles of the art system further; contributing to what, as I have suggested, is a new period in the configuration of Peru’s dominant art scene, and perhaps of the region at large.

Funding

It is in acknowledgements as the research was with a Marie Curie while the writing period was with a Newcastle University fund.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The research and curatorial aspect of this paper was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme’s Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship (844895), and the time required for the analysis and writing was supported by Newcastle University’s HaSS Faculty Research Fund. This paper has been enriched by the presentation and comments received at the LASA’s panel “Analizando el giro global hacia el arte indígena: Respuestas institucionales, mercado del arte y agencia indígena” (talk with R.Yahuarcani, online, 2021); at the “Indigenous Management of Place and Mobility in Times of Crisis: Explorations from Latin America” workshop (University of Essex, 2021) and at the “Arte Indígena Hoy: Perspectivas críticas y miradas cruzadas” seminar (Adolfo Ibanez University, 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In Configuring the New Lima Art Scene (2021a) I trace the practices of artists, curators, collectors, art dealers and museums, identifying three key moments in the reconfiguration of the contemporary art scene in Lima: artistic exploration and new curatorial narratives; museum reinforcement and the strengthening of Latin American art networks, and the rise of the market. |

| 2 | This argument requires further detail analysis on the various strategies and changes on the Peru’s art scene during this period. For some strategies in museum work in the region see (Osorio 2020). |

| 3 | The work of anthropologists, and curators, is also a practice that produces arenas of interface. I will leave this line of argument for another time. |

| 4 | For more on interface, media, and anthropology, see (Canals 2020). |

| 5 | The Amazonart project—“Conquering Self-Representation: A collaborative approach to the political aesthetical dimension of Amazonian Art”—was a recipient of the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship of the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme. See the project website: https://amazonart-project.com/, accesed on 15 January 2023. |

| 6 | For the redefinition of this project during COVID-19 and discussion about caring and curation see (Borea 2022). |

| 7 | One of the aims of the Amazonart Project was to offer artists tools not yet acquire to enhance the circulation of their work, their voice and their proposals. Training to write applications for projects grants constitutes a way of doing this, although it is sometimes not in the scope for critical discussion of the politics of art accessibility. For the University of York’s COVID-19 project see HERE—human rights defender hub (hrdhub.org), accessed on 15 January 2023. |

| 8 | The full letter can be downloaded here: Aidesep presenta propuesta para el plan de emergencia indígena por el COVID-19—AIDESEP. |

| 9 | Both artists also embarked on creating artistic platforms but for different audiences in their communities. Rubio was going to fulfil his dream of building a place where he could work and teach art and their traditions to the future generations, while Yahuarcani was going to build an art residency for art exchanges with future visitors. |

| 10 | Personal communication for the catalogue Ite!/Neno!/Here!: Responses to COVID-19 to be published in December 2023, downloadable at the Amazonart website. |

| 11 | Forthcoming catalogue (see previous note). |

| 12 | “Sin dinero ni salud, ¿quién protege a la población indígena durante la cuarentena por COVID-19?” (Without money and health: Who protects the indigenous population during lockdown?), El Comercio 15 April 2020; “¿Puede el indígena pensar por el Perú?” (Could Peru be thought by the indigenous people? El Comercio, 10 August 2020; “Los rostros del Ampiyacu: un Proyecto fotográfico que busca visibilizar a los ancianos de Pebas, en Loreto” (The faces of Amapiyacu: a photographic Project that seeks to visibilise the old people from Pebas in Loreto) El Comercio, 16 August 2020. |

| 13 | Violeta Quispe and her mother Gaudencia Yupari, Andean artists in Lima who run a Tablas de Sarhua workshop, also launched their facemasks with immediate acceptance. The Municipality of Lima supported these initiatives in Cantagallo and the Sarhua workshop. |

| 14 | See (Cánepa and Lossio 2019) for Marca Peru, neoliberalism, entrepreneurship and the remaking of identity. Also see (Quinteros et al. 2023) for other examples of how Marca Peru’s logic is embraced in Cantagallo Shipibo film production. |

| 15 | Group production, passing by family networks, is a common form of organisation for indigenous artwork. In Cantagallo, this group of productions have taken the form of “associations”—more related to community politics—and of “collectives”—more related to art forms. However, the role of individual figures in these associations and collectives cannot be denied. |

| 16 | The Andean artist Venuca Evanán and the art historian Gabriela Germaná have explored together the work of Evanán and her agency in moving beyond fixed art categories. They have presented their analysis in events such as “Las Tablas de Sarhua y el arte contemporáneo peruano: ¿Cómo repensar el giro hacia lo indígena desde la autodeterminación y la agencia de los artistas?” LASA 2021. See also (Germaná Róquez 2021). |

| 17 | See https://es.artealdia.com/Noticias/DIBUJOS-POR-LA-AMAZONIA-ADQUIERA-UNA-OBRA-DE-ARTE-PERUANO-Y-AYUDE-A-FRENAR-EL-COVID-19, accessed on 15 January 2023; Arte en campaña: campaña “Dibujos por la Amazonía” recauda fondos para comunidades indígenas de Loreto y Pucallpa|LUCES|EL COMERCIO PERÚ |

| 18 | See (Peluso 2015) and Borea 2023 for a wider discussion on circulation and place-making in and between Amazonian urban and rural communities; see also the case of the facemasks above as another example of indigenous networks of work and care. |

| 19 | For more information about the identification of the mother or father of Coronavirus in different Amazonian groups see (Belaunde et al. 2020; Espinosa and Fabiano 2022). For an explanation of how Andean people in Lima and Ayacucho communities understood and responded to COVID-19, and the artist Edilberto Jiménez’s visual account of this see (Jiménez 2021) (see also García and Pau 2022). |

| 20 | As in note 8. |

| 21 | Lastenia Canayo´s work became part of the project From Voice to Voice Peru launched by the Museum of Contemporary Art-Lima, the newspaper El Comercio, and the telecoms provider Movistar in 2020, replicating an initiative that had started in Colombia and was repeated in Buenos Aires. See De Voz a Voz 10: Lastenia Canayo, la artista de origen shipibo-konibo nos presenta al “dueño” del Coronavirus|LUCES|EL COMERCIO PERÚ |

| 22 | Brus Rubio had previously curated exhibitions at the Selva Invisible gallery—art space that he manages. |

| 23 | See Rember Yahuarcani: “Ha habido una gran apertura al arte indígena, pero el comercio de las obras es totalmente injusto”|Nuio|LUCES|EL COMERCIO PERÚ. |

| 24 | Shipibo Conibo Center is a non-profit organisation based in New York that, among other projects, represents artists and acts as an intermediary between their represented artists and the different galleries. Artists Chonon Bensho and Brus Rubio work with this Centre. |

| 25 | I avoid using non-humans (or more-than-humans) to include plants, animals, and other beings (e.g., their owners) as they share what Viveiros de Castro’s called an “extended humanity” (Viveiros de Castro 1998). |

References

- Becker, Howard. 1982. Art Worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Belaunde, Luisa E. 2020. Comando Matico en Pucallpa Desafía la Interculturalidad Inerte del Estado (Post). LaMula.pe. August 9. Available online: https://luisabelaunde.lamula.pe/2020/08/09/comando-matico-en-pucallpa-desafia-la-interculturalidad-inerte-del-estado/luisabelaunde/ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Belaunde, Luisa E., Gilton Mendes dos Santos, and Edgar Bolívar-Urueta. 2020. Presentación: Reflexiones y perspectivas sobre la pandemia del COVID-19 (Parte 1). Mundo Amazónico 11: 314–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borea, Giuliana. 2017. ‘Arte Popular’ y la imposibilidad de sujetos contemporáneos; o la estructura del pensamiento moderno y la racialización del arte’. In Arte y Antropología. Edited by Giuliana Borea. Lima: Fondo Editorial PUCP. [Google Scholar]

- Borea, Giuliana. 2010. Personal Cartographies of a Huitoto Mythology. Rember Yahuarcani and the Enlarging of the Peruvian Contemporary Art Scene. Revista de Antropologia Social do PPGAS-UFSCar 2: 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borea, Giuliana. 2021a. Configuring the New Lima Art Scene: An Anthropological Analysis of Contemporary Art in Latin America. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Borea, Giuliana. 2021b. ‘Place-Making and World-Making: Three Amazonian Indigenous Artists’ (Rember Yahuarcani, Harry Pinedo/Inin Metsa and Brus Rubio). Exhibition catalogue. Colchester: Art Exchange and Amazonart. [Google Scholar]

- Borea, Giuliana. 2022. COVID-19 and Curating: The Amazonart Project and Two Exhibitions in Times of Pandemic—The Latin American Diaries, SAS, Blog. Available online: https://latinamericandiaries.blogs.sas.ac.uk/2022/03/02/covid-19-and-curating-the-amazonart-project-and-two-exhibitions-in-times-of-pandemic/ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Borea, Giuliana. 2023. The Making of an Urban Indigenous Community: Shipibo art and the battles of place, dignity and a future. In Urban Indigeneities: Being Indigenous in the 21st Century. Edited by Dana Brablec and Andrew Canessa. Tucson: University of Arizona. [Google Scholar]

- Borea, Giuliana, and Gabriela Germaná. 2008. Discusiones teóricas sobre el arte en la diversidad. In Grandes Maestros del Arte Peruano catalogue. Lima: TgP, pp. 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Borea, Giuliana, and Rember Yahuarcani. 2020. Amazonian Waterway, Amazonian Water-worlds: Rivers in Government Projects and Indigenous Art. In Liquid Ecologies in the Arts: Fluidities and Counterflows in Latin America and the Caribbean. Edited by Lisa Blackmore and Liliana Gómez-Popescu. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Canals, Roger. 2020. Los espíritus interfaciales. Comunicación, mediación y presencia en el culto a María Lionza. In Medios indígenas. Teorías y experiencias de la comunicación indígena en América Latina. Edited by Gemma Orobitg. Madrid: Iberoamericana-Vervuert. [Google Scholar]

- Cánepa, Gisela, and Félix Lossio, eds. 2019. La nación celebrada: Marca país y ciudadanías en disputa. Lima: Fondo Editorial Universidad del Pacífico, PUCP. [Google Scholar]

- De la Cadena, Marisol, and Marianne Lien. 2015. Anthropology and STS: Generative interfaces, multiple locations. HAU Forum. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 5: 437–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cadena, Marisol, and Orin Starn, eds. 2007. Indigenous Experience Today. Oxford: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, Oscar, and Emanuele Fabiano, eds. 2022. Las enfermedades que llegan de lejos: Los pueblos amazónicos del Perú frente a las epidemias del pasado y a la COVID-19. Lima: PUCP. [Google Scholar]

- García, Andrea C., and Stefano Pau. 2022. Violencias, imágenes y memoria en el Nuevo Coronavirus y buen gobierno. Memorias de la pandemia de COVID-19 en Perú de Edilberto Jiménez. Letras 93: 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germaná Róquez, Gabriela. 2021. Tablas de Sarhua: Indigenous Aesthetics in the Context of Contemporary Peruvian Art. Ph.D. dissertation, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- INSITE Journal. 2023. Common Thread. Insite Journal. Spring. Available online: https://insiteart.org/common-thread (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Jiménez, Edilberto. 2021. Nuevo coronavirus y buen gobierno. Memorias de la pandemia de COVID-19 en Perú. Lima: IEP, Embajada de España. [Google Scholar]

- Osorio, Camila. 2020. Enseñanzas pandémicas del arte latinoamericano. El País. December 23. Enseñanzas pandémicas del arte latinoamericano|Cultura|EL PAÍS. Available online: https://elpais.com/cultura/2020-12-23/ensenanzas-pandemicas-del-arte-latinoamericano.html (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Peluso, Daniela. 2015. Circulating between Rural and Urban Communities: Multisited Dwellings in Amazonian Frontiers. Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 20: 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesantes, Maria A., and Camila Gianella. 2020. ¿Y la salud intercultural?: Lecciones desde la pandemia que no debemos olvidar. Mundo Amazónico 11: 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinteros, Alonso, Alex Vailati, and Gabriela Zamorano. 2023. Producción documental en Latinoamérica. In Antropologías Visuales Latinoamericanas. Edited by Gisela Cánepa, Giuliana Borea and Alonso Quinteros. Lima: FLACSO, PUCP, In press. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Geraldine, and David Díaz. 2021. Matico Guardian’s Fight against the Coronavirus|Ojo Público. Available online: https://ojo-publico.com/especiales/visiones-del-coronavirus/en/peru-shipibo/ (accessed on 15 June 2023).

- Soca, Melanie. 2021. Sadith Silvano. La artista Shipiba que con su cultura enfrenta al COVID-19. La Antigona. May 4. Sadith Silvano: La artista amazónica que con su cultura enfrenta al COVID-19|La Antigona. Available online: https://laantigona.com/sadith-silvano/ (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- UNESCO (Naylor, Richard, Jonathan Todd, Martha Moretto, and Traverso Rosella). 2021. Cultural and Creative Industries in the Face of COVID-19: An Economic Impact Outlook. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. 1998. Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 4: 460–88. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead, Christopher, and Emma Coffield. 2018. The multiple interfaces of engagement: Towards a new conception of gallery learning. Museum & Society 16: 240–59. [Google Scholar]

- Yahuarcani, Rember. 2021. Retratos de la pandemia: Pintura y fotografía desde la chacra de mis padres. Mundo Amazónico 12: 216–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).