Abstract

This article presents the methodology and collective work strategies that constitute the Club de Lectura y Museo Comunitario de Sierra Hermosa (Sierra Hermosa Community Museum and Reading Club) in Zacatecas, Mexico, a space founded by visual artist Juan Manuel de la Rosa, a native of this place. The museum emerged as a small library in 2000; and a short time after its founding, the museological program incorporated textile workshops and an exhibition gallery for a collection organized with local and external donations. It also operates with a system of rotation within the town. This article reviews the historical, theoretical, and critical implications around the conception and action of the museum, with a focus on the colonial and the migration status that sustains the reality and history of this rural locality, situated on the Tropic of Cancer in the north of Mexico. In the context of extreme violence, extractive politics, and migratory crisis in Zacatecas, this article analyzes two artistic productions by the local painter Luis Lara and artist Cristóbal Gracia, developed in the context of this experimental and rural museum curatorial program. Moreover, this article redefines concepts such as the border, mobility, and cultural contact in an artistic, museological, and pedagogical context, and proposes alternatives to study Sierra Hermosa’s memory, history, and landscape.

1. Introduction

In recent years, scholars have studied museums in order to critique their construction and operation as instruments of modernity. These institutions have been understood to be discursive tools that utilize history, heritage, and identity as a foundation built on collections that are comprised of various objects, each distinct in nature (Preziosi and Farago 2004). Since their conception at the end of the 18th century, museums have represented one of the most effective formats to constitute citizenship in the nation-state, in dialogue with disciplines like history, art history, botany, ethnography, and archaeology. Museums use exhibitions as a framework to condition subjectivity, giving form to a set of artifacts via certain aesthetics and specific technologies (vitrines, pedestals, framed objects, dividing walls) that provoke contemplation of the object, operating under the expectations of the public (Déotte 2008) The sets of objects that compose museum collections have the particularity of having been extracted from specific sites through programs sustained by imperialism and capitalist colonialism. In the exhibitions, they are decontextualized in favor of a hegemonic narrative that presumes a truth constituted exclusively under the Western paradigm (White 2004). In addition, recent analyses have delved deeper into the history of museology and its repercussions, in search of alternatives capable of fissuring the racist, patriarchal, and classist conditions inherent in these institutions, or indeed, strategies that could disrupt the disciplinary referents of governmentality and the power/knowledge binomial, as described by Michel Foucault (Preziosi and Farago 2004).

Ever since authors like Carol Duncan posed a line of questioning that positioned these venues as structures for ritual scenarios (Duncan 2005), diverse social processes, politics, and economic conditions have unleashed radical positions against traditional museology, in the context of various anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and anti-patriarchal movements.1 Postcolonial and decolonial theories have opened “new paradigms of both signification and subjectivization, offering alternative interpretative tools that promote a reconfiguration of a planetary reality” (Chambers et al. 2014, p. 14). In the context of globalization and neoliberal economics, we have borne witness to an extreme moment of global neocolonialism, or as Achille Mmembe explains, a violent process of expropriation, appropriation, and defense exasperated by property (Chambers et al. 2014). Under this critical gaze, migration and transcultural differences appear to be examples that seek to fracture modernist and nationalist projects.2

As Michele Greet and Gina MacDaniel Tarver explain, examples of museums in Latin America oscillate between opposing poles: “as organizations that negotiate cultural construction within the Latin American diaspora and shape constructs of Latin America and its nations; and as venues for the contestation of elitist and Eurocentric notions of culture and the realization of cultural diversity rooted in multiethnic environments” (Greet and Tarver 2018, p. 1). In this context, it makes sense to highlight how artists, theorists, and critics in different periods have signaled alternative options to Western institutional models; the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende in Chile and the Micromuseo in Peru are but two examples (Pinochet Cobos 2016).

This article re-examines the recent critiques of the museum in order to understand its position in Latin America and the particularities of thought in the region (Dussel et al. 2011).3 It intends to break with a national story, which modern museums so often reinforce to construct models of citizenship, and to outline a relationship with other examples from the continent to forge a transnational link (Tenorio 1998). Through this exercise, it also seeks to break with a generalist discourse of global culture, in order to demarcate a regional genealogy.4 This stands as an alternative museology to the colonial logics described previously, having existed for decades in this context as a concrete form of resistance.5 Furthermore, the last two decades have seen the ascent of ultraconservatism and generalized misogyny in the hemisphere, together with extreme threats against migrants, feminized bodies, indigenous communities, and people of African diaspora. In response, these groups have armed various mobilizations that have insisted on other forms of political organization, accompanied by different ways to construct material, ritual, visual, and sensible production (Tinta Limón 2021). Therefore, this article responds to the resignification of the institutionalism in art, centered on the possibilities of the museum from a logic that seeks to visualize a network of critical musealities. It is not only about studying this example in the context of community museums or Mexican museums, but also in a broader network.

Following these reflections, this study will address the case of the Club de Lectura y Museo Comunitario de Sierra Hermosa (Sierra Hermosa Community Museum and Reading Club), located in the semi-desert of Zacatecas. This project forms a line of questioning and series of attempts to transform Mexican and Latin American museums, in the contexts of the diaspora and necropolitics, as outlined in postcolonial and decolonial studies.

Likewise, it is part of a critical model that posits the museum as a tool of resistance against the renewed processes of colonization.6 As a metaphor to better understand the contribution of this community museum, I will reference the film Bacurau, directed by Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles (Mendonça Filho and Dornelles 2019). This gory ”weird western” tells the story of a small town in the Brazilian sertão that, after the death of its matriarch, suddenly disappears from the map. In the face of digital geographic erasure, the town is invaded by a group of foreign (mostly American) snipers, whose mission is to exterminate its inhabitants in a manner close to that of an imaginary video game. Faced with this tragic panorama, the community unites and, with the help of a leader of sorts, manages to overcome the invaders. As much as it may seem like fiction, this narrative is very close to Sayak Valencia’s description of the operation of necro-patriarchy in northern Mexico (Valencia 2018a). Extractivist projects carried out for the sake of the accumulation of capital have caused extermination scenarios close to those shown in Bacurau for decades. Similar to the townspeople of Bacurau who took up arms, the community museum and the objects it protects are activated as weapons for defense of a similar sort. Via acts of re-communalization of the museum’s collection and remembrance that maintains an anthropophagic logic, they manage to defend their territory and are victorious. In this regard, this museum in Zacatecas, and its collection and archives, assume a kind of resistance to these generalized processes of neocolonialism and displacement.

I also take Cristina Rivera Garza’s aesthetic proposal of disappropriation as a model to historicize the desert, which functions as a collective narrative and counterpoint to extractive (epistemological) logic in literature (Rivera Garza 2019). Regarding the territory as a subject or character, Rivera Garza activates this methodology by combining family anecdotes, historical archives, fictional references (José Revueltas), and the landscape itself. In dialogue with these literary and film works, this article describes one curatorial program that seeks to attack the traditional notions of museum, monument, and archive as observed in the museological trajectory and the cases to be analyzed.

This research also tries to visualize a methodology that emerges from thinking about family history. The museum implies a space of personal memory; action that expands and connects through the construction of a collective archive and operates in dialogue with the tools of feminist theory.7 My relationship with the museum is direct and this writing represents an attempt to explain substantial changes in the nature of the museum. In the beginning, this space functioned as an artist’s museum, that is, a museological proposal that extends, experiments, and relates to an artistic practice, in this case a painter. Subsequently, the museum generated other forms of organization and started a redefinition as a community museum. After the death of De la Rosa, the museum’s founder, this condition compelled a collectivization and feminization of the space. I consolidated my involvement as a curator, a professional relationship, as it was emotional, considering that my father was the founder. From 2021, the project needed greater collaboration with other agents, some that live far from the community and other inhabitants of the community, the majority being women.8 This condition is not exclusive to Sierra Hermosa, as María de Lourdes Salas Luévano explains.9 Since 2000, a process of feminization in rural areas in Zacatecas has been caused by “constant male migration to the United States and/or urban areas within the country in search of employment” (Salas Luévano 2009, p. 105). On the one hand, this condition can make communities vulnerable to displacement provoked by drug trafficking or mining dispossession, intensified in recent years due to the exploration of lithium deposits (Lerma Catalán 2023). On the other hand, it could also represent a moment of reorganization and collective resistance, as occurred with this museum.

This article describes the creation of the Sierra Hermosa Community Museum and Reading Club. It tells the story of the conception of the initial project as a library, organized by the artist Juan Manuel de la Rosa and the transformation it has undergone in the last 20 years. The article offers a chronology and examines the aims of the museum’s funding and early decades with the process, with the objective of demonstrating its characteristics as a museological model. It presents two cases of recent artistic production, exhibiting their working methods, and it proposes a consideration of two examples as categories that are reformulated and linked to the constitution of the museum, seen from a critical angle: the painting of artist and shepherd Luis Lara that allows reflection on the colonial past of the place and its architectural history and a sculpture by Cristóbal Gracia that presents an alternative to the definitions of the archive and the public museum.

2. The Museum

The Club de Lectura y Museo Comunitario de Sierra Hermosa (Community Museum and Reading Club of Sierra Hermosa) started as a small library for local children with the donation of 200 books in 2000, as a project by the late artist Juan Manuel de la Rosa (1945–2021). It was installed next to the elementary school in connection with the former Instituto de Cultura de la Ciudad de México (ICCM, Mexico City Institute of Culture) reading clubs organized by the poet, playwright, and cultural promoter, Alejandro Aura, who was invited directly by De la Rosa to Sierra Hermosa. Soon after its creation, the library developed its own character. Reading was the perfect excuse to create or redefine new spaces where the community could learn, discuss, and think together. Then, textile and sewing workshops were added. In 2008, an initial donation of artworks led to the opening of an exhibition room, located in a recovered space of the old Hacienda de Sierra Hermosa. Some of the inaugural artists included Manuel Felguérez, Pedro Coronel, Rafael Coronel, Ismael Guardado, Santiago Cárdenas, and Francisco Toledo.10 The collection is owned by the community and operates according to a rotation among the residents, which complements the library’s functioning. The rotation system follows the circulation model of a public library, that is, members of the community can borrow the works, take them home, and later return them to the collection. Also, in partnership with the rural school and the reading club, a communal kitchen has been organized with the village mothers, as it is usually the women that support the museum and the very life of the community.

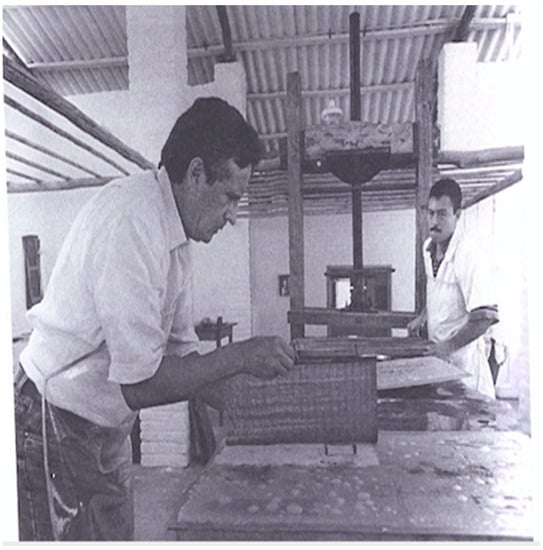

The painter, sculptor, ceramist, engraver, and papermaker, Juan Manuel de la Rosa was born in Sierra Hermosa, Villa de Cos, Zacatecas. He studied at the Taller de Artes Plásticas of the University of Nuevo Leon in 1962. Two years later, he entered the Escuela de Pintura, Escultura y Grabado “La Esmeralda” of the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes (National Institute of Fine Arts). Throughout his career, De la Rosa studied the connection between practices considered artistic and those considered crafts, but mainly techniques for making paper by hand, in countries such as France, Egypt, the United States, Japan, and Fiji. De la Rosa dedicated his plastic research to the elaboration of paper for artistic work, conceiving this support as a key to the work itself, going through the study of papyrus, amate, and “a la cuba” paper.11 Parallel to these investigations, he delved deeply into the origins of the artistic techniques, from the study of various sources to the precise formulas, and even went in search of the natural pigments such as cochineal (tlapanochestli), indigo (añil), Brazilian wood (Palo de Brasil), and the purple sea snail (tixinda). From these elements, he created a visual lexicon to express the diaspora he embodied ever since he left the desert and the Sierra Hermosa—one he shared with many peasants exiled from these lands (Salas Luévano 2009). He shaped a personal artistic vocabulary conveyed through images, colors, symbols, and materials that encompassed a wide and diverse production. De la Rosa’s work often evokes the desert he left as a child, i.e., the round horizon, the ocher reds, the salty dryness, and the azure skies of his own Zacatecas. Out of this need, the museum was born, like a landmark for the landless to finally retrace their roots12 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Alejandro Aura, El halcón. Artist book edited by Juan Manuel de la Rosa and Reading Club “Las Aureolas del Desierto”, Sierra Hermosa Zacatecas, 2008. Printed by Instituto Zacatecano de Cultura Ramón López Velarde. Editorial design by Óscar Estrada. Juan Manuel de la Rosa Archive.

In 2000, De la Rosa expanded his didactic vocation ever-present in his explorations. First, he founded the Taller de Papel (Paper Workshop) for the Foundation of San Lorenzo de Barichara, Colombia, in 2001. Given the violence and displacement that the country had endured in recent decades, this project emerged as an alternative collective for a group of women, mostly students of papermaking. From that moment on, they worked as laurentes (paper craftsmen), and continue to do so. At the same time, De la Rosa proposed el Club de Lectura “Las Aureolas” de Sierra Hermosa (Las Aureolas, Sierra Hermosa Reading Club), later called the Community Museum and Reading Club.

In the years since its founding, the library’s collection has grown, reaching over 10,000 titles, with a vast choice of children’s literature. This is an important resource for the community, since the club is also a complement to the education—nationally underfunded and thus permanently in crisis—that children receive at the Benito Juárez school, where pre-school, elementary, and telesecundaria (TV-based learning system in Mexico, developed mainly for rural communities) levels are taught. Reading turned out to be the ideal way to claim new spaces where the inhabitants and their visitors (from the municipality, the state, and the country) could share, discuss, and rethink their relationship to books and to the reading process.

Then, De la Rosa invited friends and colleagues who could share with locals, as well as promote other activities related to reading such as dance, music, theater, history, cooking, and cinema.13 Thus, the reading club gradually became a museum. A sense of playing a game, as declared by De la Rosa, was the essence of both, “Here the children are invited to enjoy, rather than to endure, the act of reading”.14 Not surprisingly, it was an artist that devised this bridge from the word to the image, especially because he cared deeply about the relationship between poetry and the visual arts, edition, and painting, as seen in the many artist’s books he created in collaboration with Alejandro Aura over the decades. Thus, the museum was born from the library, which, in 2008, added the recovered building that houses the museum’s collection. Also, being an artist committed to manual labor, as with the crafting of handmade paper that supports his work15 and his collaborations with women’s groups (Chapa and Ávila 2008), the reading club offered alternatives for artists. For example, at a crucial moment, it was decided that there would be no boundaries between art and “artisan”, that is, all works in the collection hold the same rank, whether they were made by “professional” artists or local creators.

This community museum project did not consider “cultural impact” as a requirement or objective in its conception.16 Quite the opposite, the basis for artistic production and cultural practices inside the space recovers the notion of impact from another perspective. Therefore, this institution’s aims are framed by an ongoing question. How can a museum serve its community by confronting the colonial and modern legacies of Western hegemony? Zacatecas is characterized as a state where migration has historically been present. It is a geographical zone and cultural landscape that forms part of what Paul Kirchhoff delineated as Aridoamérica in the mid-twentieth century, and who described the area’s pre-Columbian populations as predominantly nomadic (Flores et al. 1995). However, the recent displacement, especially to the United States, has had various stages since the end of the 19th century until now. This process has been intensified via “the consequent liberation of a significant mass of workers that still lingered there; coupled with the few pockets of agricultural growth and the null creation of alternative occupations” (Salas Luévano 2009, p. 89). The said problem has increased drastically in recent years after environmental crises and drug violence continue to threaten communities.

From this perspective, migration is the concept that condenses the idea of impact. Sierra Hermosa’s inhabitants have been in a state of constant mobility, as part of a long process of displacement to the United States and other larger cities in Mexico over the last decades (Henderson 2011). Through this process, the conditions for “cultural impact” have depended on the continued exchange this town and its local culture have with external references, especially with the North. In this regard, displacement has determined the conceptualization of Sierra Hermosa’s artistic and cultural production, considering mobility as a constitutive element of its museology.

As an “artist museum” since its conception, this entity stands in opposition to formal institutions. Elena Filipovic defined the relation between artistic and curatorial practice as a possibility of redefining counternarratives: “In the process, they often disown or dismantle the very idea of ‘exhibition’ as it in conventional thought, putting its genre, category, format, or protocols at stake and thus entirely shifting the terms of what an exhibition could be” (Filipovic 2018, p. 8). Filipovic explained how, before the professionalization of the “curator”, artists were endeavoring to choose the location, organize the scenography, select featured artworks, and even devise the financing scheme. This process in the context of Latin American art represents a way to explore ways of radicalization, as the genealogy of utopic or alternative museologies demonstrates (Longoni 2019) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Juan Manuel de la Rosa making paper from fique and pineapple, Fundación San Lorenzo de Barichara, Colombia, 2001. Juan Manuel de la Rosa Archive.

The activities and program of the Museo Comunitario y Club de Lectura de Sierra Hermosa can be divided into three phases: from 2000 to 2008, from 2009 to 2016, and from 2017 onwards.17 In the first phase, the library was the mainstay for every activity and operation at the museum. After the first donation of 200 books and the following collection’s growth, the main challenge was how to activate the space. Here, traditional stipulations defined by an official educational program have not worked. Instead, activities have been derived from different understandings of the ways of reading and the concept of a book. Some of the events started with an interdisciplinary connection with local festivities, for example, a bullfight, concerts, theater, talks about regional history, traditional dances, literature festivals, and community kitchen demonstrations.18 In 2008, the recovery of the old school for the ranchers of the hacienda was carried out. From this conservation process, De la Rosa proposed to fund a gallery with a series of donations, then enriched from 2017 through complementary contributions from various contemporary artists. On the one hand, this action implied the formation of the first public contemporary art collection in Zacatecas. On the other hand, this exhibition space disputed the ideal of aesthetic contemplation defined by modern and traditional museology, combining its functions as a gallery and classroom. Recently, activities have focused on thinking about how to open the museum to public space. From workshops and activities dedicated to the art and library collections to the incorporation of an online school program, these artistic and pedagogical interventions have been adapted due to the increased violence in Zacatecas over the last decades (Lomnitz 2023). The COVID-19 pandemic and the constant assaults, kidnappings, and disappearances on freeways in the whole state of Zacatecas meant that frequent journeys to the community by artists, writers, editors, and historians dropped considerably. Since 2020, instead of organizing multiple activities, these events have emphasized the need to consolidate and preserve the museum’s programming: the library, the school, and the collection. Also, it is a moment of diffusion for the museum, which happened recently with a recent retrospective show titled “Fuerza del desierto. The Sierra Community Museum and Reading Club”, in Human Resources (Los Angeles, California, 2023).19

This article presents the questions that arise after working in this museum for seven years. This experience has let us understand the nature of this space and, above all, it proposes a new definition of the very idea of a museum (Murawska-Muthesius and Piotrowski 2015). So far, it is possible to say that, since its origin, this collective gamble has kept a clear heterodoxy, since the way the terms museum, community museum, heritage, and collection are thought expresses a particularity that differentiates it from other parallel projects,20 despite exceptions that have maintained a structure of their own, also clashing with national rhetoric.21

3. The Hacienda

Sierra Hermosa, Zacatecas is a small town on the Mexican Tropic of Cancer. The history of this ranchería dates back to the colonial period, once a cattle ranch belonging to the Marquisate of Jaral del Berrio.22 This new hacienda was joined to the neighboring structures, part of a larger group that belonged to the family and provided agricultural goods to other properties throughout New Spain, many dedicated to mining, in what are now the states of Durango, San Luis Potosí, Guanajuato, and Querétaro.23 The site was part of the Reino de Nueva Galicia (New Kingdom of Galicia), an entity of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, which included the current states of Jalisco, Nayarit, Aguascalientes, and Zacatecas. The final settlement took some time, given that this area did not have direct access to water, as was the case of Bañón and Pozo Hondo, two adjacent haciendas.24 However, despite its difficulties, the Sierra Hermosa hacienda endured from 1740 well into the 19th century25 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Sierra Hermosa, Hacienda Façade, Villa de Cos, Zacatecas.

The case of Sierra Hermosa became relevant as further studies of the colonial economy during the viceroyalty were published. Historian Ana Guillermina López Murillo has shown how this property was part of a regional and interregional scheme that conflated the interests of mining and land exploitation. The Campa-Cos and Berrio-Saldívar “belonged to a select group of viceregal families (in conjunction with the Marquis of San Miguel de Aguayo, Antonio Puyade, Antonio Bassoco y Castañiza, and the Yermo family) both sheep farmers, who supplied the capital of the viceroyalty with meat during the second half of the 18th and the early 19th centuries” (López Murillo 2016, p. 101). Well covered by these studies were the enterprises that supplied the large cities of New Spain and oversaw the livestock production within the haciendas, where the concentration of land ownership was a key element in the production and transportation networks of the viceroyalty, as well as the alliances with other important families and royal officials that assisted them in business and related legal matters.

From another perspective, this project proposes an alternative to studying this history from personal and affective memory. What happened to this place after its heyday? How did the promise of land distribution and fair labor after the independence movement in the early 19th century and the Mexican Revolution during the first decades of the 20th century? What other elements of the past could today trace another historical journey? And, above all, what does architecture such as that of the hacienda mean for those who still live in this place? Emphasizing this case has implied an act of resistance, in the face of a generalized process of depopulation in northern Mexico and the subsequent denial enforced by the authorities, for reasons that include displacement due to violence, mining, and drought, with the only alternative being to move to the United States or leave for other larger cities, or in the worst of the cases, be introduced or captured by the narco-economy.

This analysis compels a dialogue with other crises that are taking place in the art world as a system. This process coincides with the quest for renewal and self-criticism of all related art institutions and their underlying foundations, i.e., museums, archives, and collections. From these questions, new reflections are ignited. What other museologies exist? Is it possible to create a museum that transcends the colonial-patriarchal conditions of its context? What other alternatives for the creation of an archive can we imagine? How can we write another way of historical narration? How can collections be rethought? How can we expand restitution onto other aspects of reality? And what other functions can a museum and a community library envision?

This study starts from a personal and yet collective history. It coincides with a commitment to artistic production as an alternative form of research and even a quest for knowledge. In the case of the Mexican literature, the writer Cristina Rivera Garza confirms this dual methodology and creative condition as entanglement with the book of essays Los muertos indóciles. Necroescritura y desapropiación (Rivera Garza 2013) and the works of fiction in which she sets in motion such polarities, such as Autobiografía del algodón (Rivera Garza 2020) and El invencible verano de Liliana (Rivera Garza 2021). In some ways, our methodology also proposes an alternative narrative to traditional historiography. As in Autobiografía del algodón, where the non-human and the landscape represent a subject of history; or the brave excavation of personal memory in order to understand life beyond the crime itself as an act of justice, exposed in El invencible verano de Liliana. Sierra Hermosa is not only a case that lets us understand the repercussions of the colonial economy, its working conditions, and land legislation, but also their relationship with the neo-liberal and neo-colonial policies of exploitation. Within Mexico’s contemporary outlook, Zacatecas turns out to be a hot spot at the crossroads of the necro- and narcoeconomies (Valencia 2018b).

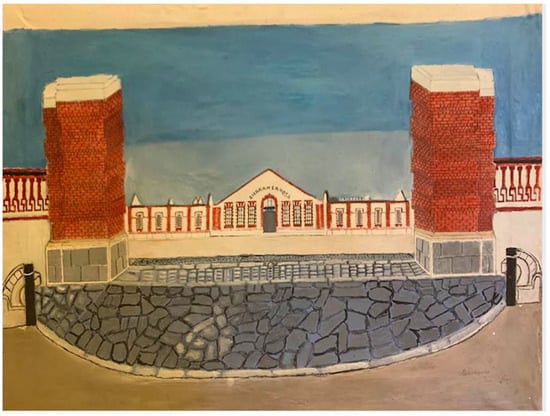

The Hacienda de Sierra Hermosa was so named having as a reference the Sierra de Sarteneja, in the Central Mesa, a notable geological feature of the Sierra Madre Oriental. Below this hill, there is a valley of semi-desert quality with a landscape full of mesquites, gobernadoras, grasslands, huizaches, lechuguillas, nopales, snakes, coyotes, badgers, field rats, and roadrunners. For centuries, this mountain range, now exploded as an onyx mine, has served as a geographic landmark for those traveling between the south and north of the country, since it points the way to the national frontier and also towards the border with the Cerro del Sabino, that is, between the states of Zacatecas and San Luis Potosí. The official name of Sierra Hermosa is Benito Juárez, and yet, it is the abandoned structures that lend a unique flavour to this location when compared to the surrounding settlements of La Mancha, Pabellón de Dolores, and Sarteneja. The architecture of the hacienda, despite its disrepair and abandonment, still alludes to an eclectic style and a symbolic monumentality. The monogram of the last owner, Manuela Moncada, crowns the friezes carved on the pink quarry stone typical of Zacatecas (Sarmiento Pacheco 2005). The first architectural complex was divided into two parts. The first section was dedicated to the livestock and agriculture (shearing, stables, silos), and the second section was dedicated to the living quarters, with a house built around a central patio, an adjoining church, and an orchard (with rooms and a structure similar to that of the other church). In 1938, General Saturnino Cedillo resigned as Secretary of Agriculture when he rebelled against President Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–1940) from San Luis Potosí (Martínez Assad 2010). Cedillo arrived at Sierra Hermosa and dismantled the hacienda, taking with him all the luxury items, many brought from Europe (tapestries, paintings, furniture, utensils, even two marble lions that welcomed visitors at the main entrance), leaving only the infrastructure, which now resembles an abandoned shell.26 Then, the house was sold and divided into four parts, of which, to date, two of these families (cattle ranchers mainly) continue to live in the best-preserved sections.

Most of the current population (settled a mile away from the old hacienda) has turned out to be children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of the hacienda workers. Sierra Hermosa’s houses are made of adobe, although concrete is being seen through the interventions carried out with remittances. The inhabitants, in times of the Marquesado and before the Revolution, were market gardeners, carpenters, blacksmiths, cooks, and scribes. Two of the hardest jobs were cleaning the ixtle to obtain fiber or doing the shearing. After they sheared the sheep, they were given a five-cent coin, one of those forged and designed exclusively for Sierra Hermosa, at the Zacatecas Mint.27 Nowadays, the hacienda continues to mark a separation between people and social classes. For example, the old church does not offer continuous service to the community, except when the family living there agrees to let them in, especially during major holidays. The relics kept in the hacienda’s church, such as the reed Christ on the altar, cannot be worshipped regularly. Instead, they must go to another church on the main street, at the entrance of the village, next to the rural school. There, the most relevant image is the Virgin of Guadalupe, made in the textile workshop by a master weaver, who lived and taught in Sierra Hermosa for some years.

Undoubtedly, the power of this ruin is its potential for historical redefinition. It is an echo of the past challenging the present that even yet suggests a future (Benjamin 2010). As Walter Benjamin points out, a ruin reminds us of the exploitation ingrained in its own spacious, grandiose memory (Jelin and Langland 2002). Thus, the hacienda is a land with dual meanings. On the one hand, the ghosts of those colonial power structures, for example, the tapestries, gnawed walls, and empty pilasters, are the roofless splendor of a long-gone sight. On the other hand, it points to revolution and rebirth, an old regime brought down, forlorn, and forgotten. This architecture also represents a critical monument. Monuments support a paradox that oscillates between perpetuity, considering their materiality, and a changing condition of their meaning. Following Mbembe’s reflection, the hacienda represents a monument: This site invited activation of a collective memory and, at the same time, an awareness of a process of destruction or erasure (Mbembe 2006).

A specific artistic work reflects this matter: The shepherd/painter Luis Lara often fills his paintings with such architectural elements. These empty structures, loaded with memories, are reinterpreted by him. Being self-taught, Lara divides his work into two areas he has named the commercial and the experimental. The first group of production deals with the typical elements of the environment, which are mostly horses that are recognizable and suitable for the local market. The second exploration focuses on the landscape and panorama as a reframing, dedicated to studying the hacienda’s façade. Lara produces his characteristic elongated canvases to encompass, as he explains, the breadth of the architecture only from his viewpoint. The compositions he creates depend on the connection between his body-eye and the architecture, since he does not have or use any reference to the Cartesian method of the perspective with a specific distance which allows him not to lose sight of the façade or the main entrance of the hacienda. Lara’s paintings represent the distance between the old marquisate construction and the beginning of the road that leads to the small village, of barely 50 houses, built as the living quarters of these menial laborers, courtiers, blacksmiths, and carpenters. And so, the relation of this shepherd with the monument allows him to rebuild and, in some way, restore the abandoned architecture through the painting. In this act, Lara reuses those ruins and endows them with another temporality and meaning (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Luis Lara, Sierra Hermosa, Hacienda Façade, acrylic on canvas, 2018. Private collection.

The history of the Sierra Hermosa hacienda and the town reveals the particularities of this museum and reading club. Community museums in Mexico propose speaking from their own histories as a form of microhistory that fights against the hegemonic narrative. On the one hand, on certain occasions, these cultural spaces continue a strategy and demarcation of specific periods in connection with the nationalist project. From this status, they can demonstrate how it is related to and part of this canonical discourse, as happens in community museums linked to the INAH, as Mario Rufer has studied (Rufer 2016). On the other hand, other radical proposals have disputed the official narrative and politics from different resistance movements by revolutionary, autonomous, or anti-capitalist organizations.28 An example of these alternative museologies is the Cherán Site Museum and Cultural Center, dedicated to remembering the Purépecha legacy and the struggle for autonomy against the government, loggers, and drug traffickers in Michoacán.29

In the case of Sierra Hermosa, local history has determined the museum’s conception, represented in various elements that are part of its program, including architectural, visual, literary, gastronomic, and material elements. From the study of architecture, the hacienda is present as a historical register and constant symbol of the colonial past in paintings, photographs, and oral history related to the Mexican Revolution; in addition, vernacular construction contrasts with the concrete of migrant architecture.30 Painting is an accompaniment and reaffirmation of an imaginary of the desert, but also a possibility of a reformulation of reality by presenting abundance where there is drought, or pictorial interventions in traditional objects, as we observe in Francisco Lara’s images as well as intervened crafts as belts or horseshoes, another example of local painting.

Luis Lara’s work lets us understand the links between the landscape and the history of the place, which confirms a distance from the traditional models of art. This creator started painting from an empirical education and is part of a small group of painters from the area who portray motifs of the rural environment, mostly animals such as horses and cattle. However, his interest in painting goes further, since he has developed a format that breaks with the idea of the canonical perspective. Luis lives in a house next to the hacienda’s entrance. His relationship with this architecture is direct and constant. From this experience, he has produced works that he calls “explorations” dedicated to studying the architecture of the ruin, especially from large panoramas that reconstruct this ancient building, by not using a Euclidean organization of the composition.

4. The Archive

In this article, I have explored the relationship between geography and history in order to understand the nature of the Sierra Hermosa Community Museum and Reading Club. These twenty years have given me and the museum collaborators enough to rethink traditional art institutions and define alternatives. Through this experimental museology, in the museum we started to materialize and visualize, nourished by counter-archives, nomadic museologies, and fabulations that suggest new possibilities to narrate our history and to delight a possibility of memory and future. As this space constantly questions and redefines the idea of what the “museum” is, so do the works produced in it or that are part of the project. That is the case of the sculpture El escarabajo y el oficio de tomar un descanso, created by artist Cristóbal Gracia, in collaboration with architects Valentina de la Rosa and Luis Manuel Chacón, builders and farmers Alberto Gutiérrez and Gustavo Ibarra, and environmentalist Frida Robles (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Pedagogical activity at a community museum. Workshop by Gemma Argüello, Appropriations: Thinking the Collection Outside the Museum”, 2020. Works by Francisco Toledo, Ramiro Chávez, Manuela García, and Luis Lara.

Cristobal Gracia’s project is part of an artistic and theoretical program organized between 2016 and 2020, which functioned in parallel and in dialogue with local artistic productions. Among the participants were Wendy Cabrera Rubio, Iraq Morales, Giacomo Castagnola, Mauricio Andrade, Miguel Fernández de Castro, Israel Urmeer, and Gracia himself. During this residency, the museum’s lines of action were re-opened. The history of the museum and its possible renovations in the face of new scenarios were analyzed. The genealogies and networks of this project with other referents in Mexico and Latin America were also considered, either as utopian museums or as community museums, from the Museum of Solidarity in Chile to the Community Museum of Valle de Xico, and from the Museo del Barro to Kaqjay Moloj in Guatemala (Ashton et al. 2013; Pinochet Cobos 2016; Moloj 2019). Each collaborator proposed a series of projects focused on three aspects, i.e., file generation, infrastructure, and pedagogy, and as part of the results, in 2018, the Fuerza del Desierto Festival was organized.31

Recently, the curatorial program for the community museum has wondered about the actual relevance of this project and the role of contemporary art in places as isolated as Sierra Hermosa, Zacatecas. This space started a process where art functioned as a strategic visualization against erased, shared memory, as survival and resistance against economic and social violence. So far, this space, which started as an artist’s museum, has expanded its organization, functions, and expectations. With the expansion and consolidation of different museological strategies, as a collectivity we continue thinking about how to open the program and the collection to the public space with the aim of understand the nature of a migrant village.

The City Council of Villa de Cos and the Department of Education and Culture offered to commemorate the first anniversary of the death of Juan Manuel de la Rosa, which included his appointment as Illustrious Citizen of Villa de Cos by the unveiling of a bust and plaque. The Community Museum of Sierra Hermosa rejected it as an outdated civic gesture, in tune with De la Rosa’s own opinions. What the ceramist and papermaker always saw in sculptural intervention on the streets, in squares, and in gardens, was a transformation of the context and a dialogue with architecture (as seen in the unrealized project for the Tropic of Cancer, which he sought to erect in the middle of the desert). Instead, as a curator, I proposed the production of a sculpture for the esplanade of the museum in Sierra Hermosa. I considered Cristobal Gracia because of his friendship with De la Rosa as well as his full involvement with the sculptural medium (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Cristóbal Gracia, El escarabajo y el oficio de tomar un descanso (The Beetle and the Craft of Taking a Break), public sculpture, concrete, 2022. In collaboration with architects Valentina de la Rosa and Luis Manuel Chacón, builders and peasants Alberto Gutiérrez and Gustavo Ibarra, and environmentalist Frida Robles. Sierra Hermosa Community Museum and Reading Club, Zacatecas.

In 2016, Gracia was invited as an artist guest with Daniel Aguilar Ruvalcaba to collaborate with the Sierra Hermosa Community Museum and Reading Club. It was not the first time Gracia met Juan Manuel de la Rosa. In one visit to the group exhibitions organized by the collective Yacusis. Grupo de Estudios Sub-Críticos, these two artists met and found their shared enthusiasm and restlessness. Gracia recalls, “He was a great mystery, there was no way I could define this character. So many things at the same time, I didn’t know just where, and when, and how to place him” (Gracia 2022). Later, Gracia was able to unveil the mystery. He says that when he learned that displacement was the essence of his new friend’s work, he could finally understand him. The sculptor observes how the artist conveyed this: “He had a touch of the foreign, of ancient travels, held by a rural soul –deep-rooted and well-grounded” (Gracia 2022).

Eventually, curiosity turned out to be reciprocal. One of their common passions was their interest in traditional trades. The work El escarabajo y el oficio de tomar un descanso (The Beetle and the Craft of Taking a Break) refers to and illustrates this connection. Gracia says that one day, while walking through Zacatecas, De la Rosa asked him about his work. He showed him documentation of the exhibition Aquatania. Parte I. Un hombre debe ocupar el lugar que Dios le otorga—caminos selváticos o las calles de Hollywood—y pelear por las cosas en las que cree (Aquatania. Part I. A Man Must Occupy the Place God Gives Him—Jungle Roads or the Streets of Hollywood—and Fight for the Things He Believes In) that he held at the gallery El Cuarto de Máquinas (2015–2016). For that occasion, Gracia revisited Acapulco’s relationship with the film industry, specifically Hollywood, through the story of the Romanian born actor Johnny Weissmuller. The focus was on Tarzan and the Sirens (1948), the last film in a series, for which the actor spent his last days at the Los Flamingos Hotel. The project, based on its recreation, produced a complex body of sculptures, photographs, paintings, and installations that pointed to the collaboration of Mexican artists Gabriel Figueroa (1907–1997) and Gunther Gerzso (1915–2000) right within the film. Within the series, Gracia presented a sculpture made of palm tree trunks intervened with geometric steel figures, inspired by Gerzso’s abstract paintings and his scenographic work as well as the ocean landscape. Thus, concern with the environment was another bond between them. De la Rosa asserted joyfully that a version could be made with palms and yuccas from the desert. Thus, they wondered how the Tropic of Cancer’s vegetation would look as a sculpture. Ever since that talk, Gracia’s take on the landscape was transformed forever.

The homage unveiled for this solemn act was based on that reference to Aquatania. First, Gracia increased the scale, then he switched positive spaces to negatives from the original piece. One of the most salient transformations was this overturning of the standing sculpture, which was instead placed horizontally. This variation challenged the traditional idea of a monument or public sculpture, which is usually vertical (a hallmark of the patriarchal regimes that produce them). By laying it down, it suddenly was different. A place for rest and thought. A work that by denying verticality could, in parallel, echo simply the landscape. This final resolution unites all the conditions and implications of this community museum. Each artistic production in this museum follows three axes: the creation of a collective archive focused on microhistory, territory, and a critical genealogy; the development of pedagogy in links between art and literature; and finally, the redefinition of public space. This piece, a celebration of a friendship between artists, is a tribute to displacement, the essence of De la Rosa’s work, both in its function (dedicated to a pause for contemplation) and in its construction (made by the nomadic inhabitants of Sierra Hermosa, Alberto Gutiérrez and Gustavo Ibarra). Thus, this sculpture bench beckons restoration to the body and the memory, while being a living archive of the desert’s vegetation, in dialogue with the study that Frida Flores started in this landscape, an environmentalist who started working as a guest researcher (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Sierra Hermosa Community Museum and Reading Club, Zacatecas.

This article introduced the history of the colonial and extractive past in Sierra Hermosa in the context of a recent crisis related to the growing violence of the narcoeconomy and necropolitics in Mexico. It is an examination of the history of the museum, its characteristics, and long-term transformations over twenty years since its founding in the service of understanding new, community-based museological strategies. While the nature of the museum initially depended on the proposal of the artist founder of the space, it was later redefined by a group of women, including this author, where a dynamic museology that considers the history and nature of this place has been developed. The article also considers the history of the colonial and extractive past in Sierra Hermosa in the context of a recent crisis related to the growing violence of the narcoeconomy and necropolitics in Mexico and how it has impacted local museum practices. The two examples presented, i.e., the series of paintings by Luis Lara, an inhabitant of the locality, and Cristóbal Garcia, an invited artist, each demonstrate artistic strategies that utilize the community museum as a site of reclamation, either through a pictorial reflection on the ruins of the hacienda that gives its name to the town or from a reinterpretation of the public monument, carrying out, instead, a living archive proposal. This article argues that the forms of artistic production developed in this experimental museum offer new possibilities for historical narration and configuration of collective archives.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not appliable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | From 2020, various institutions have opened multiple forums, seminars, and exhibitions to rethink museological programs and seek options that shape another museum model and give access to other communities and subjectivities that had been displaced. In the case of Latin America, it stands out: Véxoa. We know (2020) at the Pinacoteca de São Paulo in Brazil curated by Naine Terena. |

| 2 | The Postcolonial Museum outlines a perspective that places the Mediterranean at the center and proposes a tension between the global and the local, inviting a different type of narration, decentered and re-elaborated under the notion of the diaspora. De Angelis, Ianniciello, and Michaela Quadraro, “Introduction: Disruptive Encounters—Museums, Arts and Postcoloniality” (Chambers et al. 2014, pp. 14–15). |

| 3 | Paulo Henrique Martins, “Sistema-mundo globalizaciones y América Latina”, in (Bialakowsky et al. 2015, p. 67). The history of the American continent makes concrete the building blocks that have constructed our current world-system, as has been demonstrated since the 1960s by various theories of political economy based on a critique of developmentalism and dependency. Such theorists include Andre Gunder Frank, Samir Amin, Theotonio Dos Santos, and Immanuel Wallerstein, while authors such as Aníbal Quijano and Sylvia Wynter outline critiques of modernity and coloniality. |

| 4 | Gustavo Buntinx. “El empoderamiento de lo local”. Typescript of paper delivered at “Circuitos latinoamericanos/Circuitos internacionales. Interacción, roles y perspectivas”, Feria de Arte de Buenos Aires (arteBA), May 2005, ICAA RECORD ID 1065640 (accessed on 30 May 2023). Buntinx refers to the construction of democracies for Latin America where the periphery plays a relevant role in the face of the strategic erasures of the global project: “[A]rduous and unavoidable mission of regenerating the state and public institutions of art, penetrating and transforming its inoperative museums and academies, its devastated archives, its anachronistic schools. Contribute from there to the radical and critical reform of those States that are today, so many times, a special factor of inequities and underdevelopment in our societies”. |

| 5 | Adele Nelson, “Mário Pedrosa. El museo de Arte Moderno y sus márgenes”, in (Pineda and Rodríguez 2017, pp. 54–63). In dialogue or in parallel with this critical tradition, I can also cite authors such as Mário Pedrosa or Juan Acha, who from the perspective of heterodox Marxism and other theoretical references of communication, radical pedagogy, structuralism, dependency theory, presented antecedents and links that proposed museologies that were later assumed as radical models: those that seek to break the hierarchies of cultured art and crafts, or subjects that incorporate indigeneity, blackness, or those with mental health problems. |

| 6 | In 2018, the government published some statistics that announced the disappearance of 20 of the 58 municipalities in Zacatecas, including Villa de Cos, where Sierra Hermosa is located (Valadez Rodríguez 2018). |

| 7 | These references range from Sara Ahmed to Raquel Gutiérrez Aguilar. Cfr. (Ahmed 2015; Gutiérrez Aguilar 2017). |

| 8 | In my case, I live in Mexico City and Oaxaca. I have had a relationship with Sierra Hermosa since I was a child, travelling frequently to visit family, as did my sister the architect Valentina de la Rosa, who also collaborates with the museum. In the case of the online high school teacher Faviola Lara, she lives in Saltillo, Coahuila. The other direct collaborators, such as Soledad Ramírez de la Rosa, Britney Cardona, Ilse Botello, Gabriela Ríos, are residents of Sierra Hermosa. This phenomenon is a contsant in the population; given the high rate of migration, there are constant trips by family members from different parts of the country and the United States to the community on certain dates of the year. |

| 9 | This process of feminization affects activities such as: agriculture and the trade of products like fabrics, garments, and handicrafts. In addition, it affects family organization: “With the migration of men, transformations are brought about in the social organization of communities; some of them manifest themselves inside homes with the weakening of the traditional family structure”. Cfr. (Salas Luévano 2009, p. 105). |

| 10 | In 2017, a new donation scheme was promoted by Cristóbal Gracia and Daniel Aguilar Ruvalcaba, as a part of the curatorial project proposed by this writer. The donations were made by both national and local artists, with the paintings of Luis Lara, and Francisco Lara, the sculptures of Noé Maciel, and the textiles of Yuri Ríos and Gabriela Gámez. The unveiling of the works took place at the inauguration of the exhibition “Éxitos de ayer y hoy. Primera muestra de la colección del Museo Comunitario de Sierra Hermosa”. This event was a public display of the museum’s inventory, to be held in full by the inhabitants of Sierra Hermosa. Next to the works created for the project (such as those produced by Miguel Fernández de Castro, Israel Urmeer and Wendy Cabrera Rubio); 30 donations, were made by artists such as Ramiro Chávez, Álvaro Verduzco, Yolanda Segura, Sofía Garfias, Madeline Santil, Marco Aviña, Marek Wolfryd, Sangree, Manuela García, Mauricio Limón, Jael Orea, Valentina Díaz, Darinka Lamas, Santiago Robles, Ektor García, Carlos Iván, Wimpy Salazar, Gala Berger, Galia Basail, Cecilia Miranda, Chelsea Culprit, Lisa Giordano, among others. |

| 11 | The traditional craft of hand-making paper, or Washi, is practised in three communities in Japan: Misumi-cho in Hamada City, Shimane Prefecture, Mino City in Gifu Prefecture and Ogawa Town/Higashi-chichibu Village in Saitama Prefecture. The paper is made from the fibres of the paper mulberry plant, which are soaked in clear river water, thickened, and then filtered through a bamboo screen. Washi paper is used not only for letter writing and books, but also in home interiors to make paper screens, room dividers and sliding doors. Most of the inhabitants of the three communities play roles in keeping this craftsmanship viable, ranging from the cultivation of mulberry, training in the techniques, and the creation of new products to promote Washi domestically and abroad. In Spanish, “A la cuba” refers to the tub where the paper pulp is prepared (UNESCO 2014). Washi, Craftsmanship of Traditional Japanese Hand-Made Paper. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J6C8ESEAeAo (accessed on 6 June 2023). |

| 12 | Several studies and interviews confirm that massive migration from the community took place during the 1950s and 1960s, due to a drought crisis and foot-and-mouth plague that led to severe depopulation. The original inhabitants of Sierra Hermosa and other places in Zacatecas moved to the United States or began a diaspora to other northern states in the throes of rapid industrialization: Nuevo León, Coahuila, and Chihuahua. |

| 13 | For these activities to succeed, and the donations to continue, the artist’s direct involvement—both in management and promotion—proved crucial. To a lesser extent, so was some municipal and state support. As of 2017, some grants were also applied for. Among them are William Bullock Chair Award, MUAC-UNAM, 2017, Fundación Jumex 2018, and Patronato Arte Contemporáneo 2019. |

| 14 | The interview was conducted by architect Adán González of the Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo with Juan Manuel de la Rosa as part of the William Bullock Grant, MUAC-UNAM, September 2017. |

| 15 | Julles Heller includes Juan Manuel de la Rosa in what has been called “the paper revolution”, a 1970s artistic movement where paper is the work and not the medium. See (Heller 1978). |

| 16 | Cultural impact is a concept that describes the changes in the quality of life of a local entity, transformations that affect individuals’ surroundings (architecture, arts, customs, rituals, etc.). Cfr. (Boyd et al. 2018). |

| 17 | Since 2016, I have been working as the coordinator of the museum’s adaptation and renovation. This action implies one interconnection between a professional field and personal history. Sierra represents a case of study, but mostly, a strategy for recovering and understanding my family memory. |

| 18 | The bullfight was organized with the support of a local rancher who donated the fighting bull. The music style from the concerts has covered from classic music, with the presentation of The World Orchestra, to local music, performed by the village violinist and guitar player from town, Juan Botello and Bérulo Uribe Montoya. For the theater and literature events, the program introduced formal actors or writers, in combination with historical plays (pastorelas) and oral tradition (Corridos from the Revolution and Cristero War), only memorized by Hermenegildo Ríos. |

| 19 | “Fuerza del desierto. The Sierra Community Museum and Reading Club”, Human Resources, April, 2023. https://www.h-r.la/event/fuerza-del-desierto-the-sierra-hermosa-community-museum-and-reading-club/ (accessed on 6 June 2023). |

| 20 | Mario Rufer’s work lets us see the bonds between the idea of the community museum and that of the archive from a postcolonial perspective, specifically from a reading of the Cameroonian theorist Achille Mbembe. Rufer has studied the demands for a public record and the uses of the recent past in Argentina through museums, monuments, and memorials, as well as in South Africa. For Rufer, in both areas, the aim was to reveal the “other” within the state’s narrative when challenged by critical, historical circumstances. In Mexico, however, the state’s clear hold over national culture has forced community museums to conciliate and absorb the official histories and moderate their own. Rufer thus concludes that, while other areas may yet find their truer voices, in Mexico the past tends to be voiced by bureaucrats. See (Rufer 2016, pp. 85–113). |

| 21 | A relevant case of considerable impact in many realms, including contemporary art, as a “radical, ambitious and unpretentious experiment” is the Museo Comunitario del Valle de Xico, created in 1996 to protect the community’s heritage. It is mainly a series of pre-Hispanic pieces augmented with other donated objects. As Pablo Lafuente and Michele Sommer explain: “The museum belongs to and within the community. It thrives in the community just as the community thrives in it”. See (Lafuente and Sommer 2017), (Spring/Summer 2017), https://www.afterall.org/journal/issue.43/-history-is-made-by-the-people- (accessed on 18 June 2022). |

| 22 | According to some sources, the hacienda was founded when the Moncada family was granted use of these lands and moved the Hacienda de Sierra Vieja to Sierra Hermosa. Historian Homero Adame has done intensive research on this estate. He indicates that the title of marquisate was granted to Miguel de Berrio Zaldívar in 1774. He married Anna María de la Campa y Cos, Countess of San Mateo de Valparaíso, whose daughter married the fortune hunter Pedro de Moncada. The heyday of the estate came during the 19th century, with the third and last Marquis of Jaral de Berrio, took over El Carro, La Ventilla, and Troncoso. Miguel Berrio y Saldivar’s fortune is representative of the kind of wealth that Creole families and their heirs could muster in the states of Zacatecas and San Luis Potosí since the 17th centurythrough mining, agriculture, and the sheer power of royal appointments. See (Adame 2010). |

| 23 | Some of the properties that belonged to this marquisate were the Hacienda de San Diego de Jaral, in Guanajuato, and the Palacio de los Marqueses del Jaral del Berrio, later called Palacio de Iturbide, in Mexico City. |

| 24 | The lands of Sierra Hermosa had several owners since the 17th century, and the hacienda was not consolidated until the Moncada family settled there. See (Sarmiento Pacheco 2005, p. 131). |

| 25 | The importance of the Hacienda de Sierra Hermosa can be seen in various local documents as well as in certain contemporary reports. The Westminster Review, in a section dedicated to America and pointing to independent Mexico, published a study on agriculture, cattle raising, and mining in 1827. On the haciendas and their operation, it mentions the exploitation in the latifundia system: “The principal dependientes upon an hacienda receive a very small salary, in lieu in which they are allowed to keep a certain quantity of life stock, upon the land. Many of the Rancheros of the conde de Jaral on the Hacienda of Sierra Hermosa, adjoining the states just mentioned, who have only four or five dollars a month in money, possess as many as eighty thousand goats, with an atajo of eighty or a hundred horses”. See: (Ward 1828, p. 496). |

| 26 | Martha Beatriz Loyo Camacho have studied from the reference of General Joaquín Amaro, Sierra Hermosa’s revolutionary history (Loyo Camacho 2003, pp. 17–20). |

| 27 | Juvenal Noriega, Lidia de la Rosa, Hermenegildo Ríos, Luis Lara, Juan Botello, Series of Interviews, September 2016. |

| 28 | Recently, other museum projects in different contexts work in the rural environment. A relevant example is INLAND, Campo Adentro, Spain, which was destined to work as a school for shepherds and cheese producers. INLAND’s participation was important in Documenta 15 (2022). Kimberly Cordova explains the transition between the work at the camp and its collaboration in a exhibition space: “Founded by artist Fernando García-Dory in 2009, Campo Adentro, anglicized to INLAND, links artistic and agrarian labor in a freewheeling and difficult-to-define practice that merges community organizing and leadership development with ecological and pastoral aesthetic inquiry. A central aim of ruangrupa and INLAND’s work is a desire to square off with capitalism’s orientation to time and geography as device of value extraction. Both have been clear that their interest is in building community, activism, and experimental inquiry. Objects on display, which most people equate with capital-A art, here are really just pretext. So, with the true focus on public programming and participatory action, none of which had yet to transpire during the press week, all the presentations were somewhere between zero and roughly eighty-seven percent ready, depending on what one considers ‘the work’. The effect was the feeling of arriving to social justice art summer camp, but a week too early and not necessarily invited” (Córdova 2022). |

| 29 | In 2011, the Purépecha community of Cherán decided to confront organized crime, loggers, and politicians. Since that movement, a group of creators from different generations have accompanied this project through an artistic process by collectively managing and following the decisions of the Consejos de Mayores (High Council) and neighborhood authorities. |

| 30 | Migrant architecture is a type that responds to the phenomenon of remesas, or money that is sent from the United States. The artist Sandra Calvo explains: “The production process is regulated by a constant flow of information and remesas. The migrants send to their familiaes –as well as money– photos, magazine cuttings, and sketches by theselves, all of which are references for the design. The lots where they build these mansions are built are generally close to the houses of their relatives, a gesture that concerns rootedness, a sense of belonging, but also necessity”. Cfr. (Arellano 2021) https://www.archdaily.mx/mx/960115/copias-de-abandono-la-arquitectura-como-reflejo-de-procesos-migratorios-entre-mexico-y-estados-unidos (accessed on 8 June 2023). |

| 31 | The Fuerza del Desierto Festival included: the play Amor en el desierto zacatecano II. La maldición del Chupacabras by Wendy Cabrera Rubio in collaboration with Manuel Plazola; The projection and collective drawing El día que atrape al Correcaminos by Israel Urmeer; a demonstration of Juan Manuel de la Rosa’s desert gastronomy and community cooking; the presentation of the imaginary shop of the museum of John Birtle. Cfr. (De la Rosa 2019, no. 14) http://caiana.caia.org.ar/template/caiana.php?pag=articles/article_2.php&obj=348&vol=14 (accessed on 2 March 2023). |

References

- Adame, Homero. 2010. Haciendas del Altiplano, Historia(s) y leyendas. San Luis Potosí: Gobierno del Estado, Secretaría de Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Sara. 2015. La Política Cultural de las Emociones. Mexico City: UNAM-PUEG. [Google Scholar]

- Arellano, Mónica. 2021. Copias de Abandono: La arquitectura como reflejo de procesos migratorios entre México y Estados Unidos. Archdaily. April 21. Available online: https://www.archdaily.mx/mx/960115/copias-de-abandono-la-arquitectura-como-reflejo-de-procesos-migratorios-entre-mexico-y-estados-unidos (accessed on 14 May 2023).

- Ashton, Dore, Carla Macchiavello, and Carla Miranda. 2013. 40 años Museo de la Solidaridad por Chile: Fraternidad, arte y política 1971–1973. Santiago de Chile: Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Walter. 2010. Tesis Sobre la Historia y Otros Fragmentos. Bogotá: Ediciones desde Abajo. [Google Scholar]

- Bialakowsky, Alberto L., Marcelo Arnold Cathalifaud, and Paulo Henrique Martins, eds. 2015. El pensamiento en América Latina. Diálogos en ALAS. Buenos Aires: Editorial Teseo. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, Roy, María Eugenia Ibarrarán, and Roberto Vélez Grajales. 2018. Understanding the Mexican Economy: A Social, Cultural, and Political Overview. Bingley: Emerald Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, Iain, De Angelis Alessandra, Ianniciello Celeste, Orabona Mariangela, and Quadraro Michaela. 2014. The Poscolonial Museum. The Arts of Memory and the Pressure of History. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Chapa, María Elena, and María del Refugio Ávila. 2008. Mujeres Artífices del Papel. Entrevista con Juan Manuel de la Rosa. Monterrey: Instituto Estatal de las Mujeres, Gobierno de Nuevo León. [Google Scholar]

- Córdova, Kimberly. 2022. Field Notes: Kim Córdova on INLAND at Documenta 15. e-flux, July 26. [Google Scholar]

- De la Rosa, Natalia. 2019. Un Museo en el Trópico de Cáncer: Primeros Acercamientos Para el Desvío Comunitario. Caiana: Revista de Historia del Arte y Cultura Visual del Centro Argentino de Investigadores de Arte (CAIA). [Google Scholar]

- Déotte, Jean-Louis. 2008. El museo no es un dispositivo. Available online: http://www.lauragonzalez.com/ImagenCultura/Deotte_2008_ElMuseoNoEsUnDispositivo.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Duncan, Carol. 2005. Rituales de Civilización. Translated by Ana Robleda. Madrid: Nausícaä. [Google Scholar]

- Dussel, Enrique, Eduardo Mendieta, and Carmen Bohorquez. 2011. El Pensamiento filosófico latinoamericano, del Caribe y “latino” (1300–2000): Historia, Corrientes, Temas y Filósofos. Mexico City: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Filipovic, Elena. 2018. Artist As Curator: An Anthology. Köln: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, Zavala, Marco Antonio, and Roberto Ramos Dávila. 1995. Zacatecas. Síntesis Histórica. Texas: University of Texas. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia, Cristóbal. 2022. Independent Artist, Mexico City, Mexico and New Haven, CT, USA. Personal communication, June. [Google Scholar]

- Greet, Michele, and Gina McDaniel Tarver, eds. 2018. Art Museums of Latin America: Structuring Representation. Londres: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Aguilar, Raquel. 2017. Horizontes Comunitarios Populares. Producción de lo común más allá de las políticas estado-céntricas. Madrid: Traficantes de Sueños. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, Julles. 1978. Papermaking. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, Timothy J. 2011. Beyond Borders. A History of Mexican Migration to the United States. Chichester: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Jelin, Elizabeth, and Victoria Langland, eds. 2002. Monumentos, Memoriales, y Marcas Territoriales. Madrid: Siglo XXI. [Google Scholar]

- Moloj, Kaqjay. 2019. KAQJAY (2006–////). Mexico City: Fiebre Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Lafuente, Pablo, and Michele Sommer. 2017. ‘History is made by the people’: Fragments on the Museo Comunitario del Valle de Xico. Afterall Journal 43: 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerma Catalán, Martín. 2023. “Una tercera parte del territorio estatal, el 31.7%, está concesionado a las mineras”. La Jornada Zacatecas. April 23. Available online: https://ljz.mx/23/04/2023/una-tercera-parte-del-territorio-estatal-el-31-7-esta-concesionado-a-las-mineras/ (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Lomnitz, Claudio. 2023. “Antropología de la zona del silencio”. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=blPVxzmyeeA (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- Longoni, Ana. 2019. Ya no abolir los museos sino reiventarlos. Algunos dispositivos museales críticos en América Latina. Caiana: Revista de Historia del Arte y Cultura Visual del Centro Argentino de Investigadores de Arte (CAIA). [Google Scholar]

- López Murillo, Ana Guillermina. 2016. Empresarios ganaderos novohispanos del siglo XVIII. Los condes de San Mateo de Valparaíso y marqueses de Jaral de Berrio. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, Zacatecas, Mexico. [Google Scholar]

- Loyo Camacho, Martha Beatriz. 2003. Joaquín Amaro y el proceso de institucionalización del Ejército Mexicano, 1917–1931. Mexico City: FCE. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Assad, Carlos. 2010. El Camino de la Rebelión del General Saturnino Cedillo. México City: Océano. [Google Scholar]

- Mbembe, Achille. 2006. Le Messager. Available online: http://africultures.com/que-faire-des-statues-et-monuments-coloniaux-4354/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Mendonça Filho, Kleber, and Juliano Dornelles. 2019. Bacurau. Paris: SBS Productions. [Google Scholar]

- Murawska-Muthesius, Katarzyna, and Piotr Piotrowski. 2015. From Museum Critique to the Critical Museum. Farnham Surrey, England. Farnham: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, Mercedes, and Mafalda Rodríguez, eds. 2017. Mário Pedrosa. De la Naturaleza Afectiva de la Forma. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. [Google Scholar]

- Pinochet Cobos, Carla. 2016. Derivas del museo en América Latina. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Dirección General de Artes Visuales. Palabra de Clío: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. Ciudad de México: Siglo Veintiuno Editores. San Andrés Cholula, Puebla: Universidad de las Americas. [Google Scholar]

- Preziosi, Donald, and Claire Farago, eds. 2004. Grasping the World. The Idea of the Museum. Aldershot: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Garza, Cristina. 2013. Los muertos indóciles. Necroescritura y desapropiación. Mexico City: Tusquets Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Garza, Cristina. 2019. El drama del desierto. La escritura geológica de José Revueltas. Mexico City: Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, UNAM. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=etXXohyvtgY&t=1307s (accessed on 8 July 2023).

- Rivera Garza, Cristina. 2020. Autobiografía del algodón. Mexico City: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Garza, Cristina. 2021. El invencible verano de Liliana. Mexico City: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Rufer, Mario. 2016. El patrimonio envenenado: Una reflexión ‘sin garantías’ sobre la palabra de los otros. In Disciplinar la Investigación: Archivo, Trabajo de Campo y Escritura. Madrid: Siglo XXI, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, pp. 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- Salas Luévano, María de Lourdes. 2009. Migración y Feminización de la Población rural 2000–2005. El caso de Atitanac y La Encarnación, Villanueva, Zacatecas. Zacatecas: Tesis de doctorado en Ciencias Políticas, Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmiento Pacheco, Oliverio. 2005. Las haciendas entre el Real de Minas. Pozo Hondo, Bañón y Sierra Hermosa en el siglo XVIII, acercamiento a la historia de Villa de Cos. Zacatecas: Gobierno del Estado de Zacatecas y Municipio de Villa de Cos. [Google Scholar]

- Tenorio, Mauricio. 1998. Artilugios de la Nación. México en las Exposiciones Universales, 1880–1930. México City: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [Google Scholar]

- Tinta Limón. 2021. Chile em Chamas. A Revolta Antineoliberal. Translated by Igor Peres. Tinta Limón Series. Research and Interviews. São Paulo: Editoral Elefante. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2014. Washi, Craftsmanship of Traditional Japanese Hand-Made Paper. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J6C8ESEAeAo (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Valadez Rodríguez, Alfredo. 2018. ‘Tienden a desaparecer’ 20 de los 58 municipios de Zacatecas. La Jornada Zacatecas. Available online: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2018/02/19/estados/026n1es (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Valencia, Sayak. 2018a. Gore Capitalism. Translated by John Pluecker. Cambridge: The MIT Press. South Pasadena: Semiotext(e). [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, Sayak. 2018b. Psicopolítica, celebrity culture y régimen live en la era de Trump. Norteamérica 13: 235–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, Henry George. 1828. Mexico in 1827. The Westminster Review 9: 480–90. [Google Scholar]

- White, Hayden. 2004. The fictions of factual representation. In Grasping the World. The Idea of the Museum. Edited by Donald Preziosi and Claire Farago. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, pp. 22–35. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).