Aleijadinho’s Mestiço Architecture in Eighteenth-Century Brazil: Inventing Brazilian National Identity via a Racialized Colonial Art

Abstract

1. Introduction: The Origins of the Myth

2. The Society of Eighteenth-Century Minas Gerais

3. The “Emancipation” of the Mestiço Artist in the 1920s: The Modernist Interpretation of Aleijadinho

3.1. The Modernist Excursion to Minas Gerais in 1924

3.2. Mário de Andrade’s Discussion of the Baroque of Minas Gerais: Originality, Tradition, and Race

4. “Deformed” Baroque, Utopian Baroque

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

| 1 | All translations from Portuguese are mine unless stated otherwise. |

| 2 | (de Oliveira 2014). For a study on the architectural typologies in Minas Gerais, see (Smith 1939). |

| 3 | See especially the second chapter of (de Grammont 2008). |

| 4 | (de Oliveira 1985, p. 20). According to Myriam de Oliveira, the first historical mention to Lisboa’s career dates back to 1766, when the artist received an important commission from the Church of Saint Francis of Assisi in Vila Rica. |

| 5 | See commented edition of Bretas’ account: (Bretas [1858] 2002, p. 76); and (de Grammont 2008, p. 86). |

| 6 | See also (de Grammont 2008, p. 69). |

| 7 | (Bazin 1963, p. 97). The actual passage in Eschwege reads “lame hands”. |

| 8 | (Bazin 1963, p. 97). The original text refers to an artist “who had no hands”. |

| 9 | See also (de Grammont 2008, p. 138). |

| 10 | The Museu da Inconfidência, in Ouro Preto, shows, side by side, three receipts signed by Aleijadinho, the last one being from 1802. Perhaps someone versed in calligraphy could have compared the signatures, but this lies beyond my abilities. For the reproduction of several other signed receipts, and further records that attest to Aleijadinho’s involvement in many projects, refer to (de Andrade 1938). |

| 11 | I choose to use the Portuguese term—mestiço—instead of the Spanish mestizo, which is more commonly used in English, because of the broader meaning the concept has in its Portuguese application. While the word mestizo refers to people of mixed European and Indigenous American ancestry, the classification in Portuguese assumes a much less defined meaning, describing an individual originating from any possible ethnical mixture between European, African, Indigenous, Asian, and/or any non-mixed racial identity. In Portuguese, the word mestiço can be used as a noun or an adjective. A fundamental trait of Brazilian society, this identity is essential to the country’s self-awareness and was theorized in several moments of its history. While mestiço means essentially the same as the word pardo, commonly included in official records and statistics, the word mestiço carried utopian undertones in the 20th century. |

| 12 | “Paulista” in Portuguese is the adjective that defines people and things from the state (or former captaincy) of São Paulo. |

| 13 | (Antonil [1711] 2011, p. 219). Father Antonil refers to a mestiço man (“um mulato”) who was the first one to have discovered gold in the area of Cataguás. The first pieces of gold were discovered in 1697 in the rivers, an indicator of the existence of gold deposits in the mountains. This particular type of gold was covered in a black color, from which the name Ouro Preto derives. Acting upon this news, several bandeiras initiated, literally, a treasure hunt, and with it, the period of intense exploration that lasted less than a century. |

| 14 | (Antonil [1711] 2011, p. 224); (Souza 2006, p. 154). According to Laura de Mello e Souza, before the end of the century, the population of Minas Gerais was estimated at 380 thousand inhabitants, originating from several parts of the Portuguese Empire. |

| 15 | (Schwarcz and Starling 2015, p. 114). On the mythic or utopian resonance of Minas Gerais in the 18th century, see (Souza 2022). |

| 16 | Quitandeiras were Black trader women directly associated with the quilombos, fortified settlements housing communities of escaped enslaved people, spread in remote areas throughout the colony. According to Tania Costa Tribe, the occupation of Black and mestiço street vendors “often functioned as an important pathway towards the acquisition of freedom and social mobility”. See (Tribe 1996). |

| 17 | Tomás Antônio Gonzaga, Cartas Chilenas (Gonzaga 2006), Third Letter, verses 140–145. “Também, nas grandes levas, os escravos/Que não têm mais delitos que fugirem/Às fomes e aos castigos, que padecem/No poder de senhores desumanos./Ao bando dos cativos se acrescentam/Muitos pretos já livres e outros homens/Da raça do país e da européia”. |

| 18 | Tomás Antônio Gonzaga, Cartas Chilenas (Gonzaga 2006), Fifth Letter, verses verses 60–64, and 234–245. |

| 19 | Most famously, the Inconfidência Mineira (1789), a revolt of republican demands, was headed by members of the white, literate elite including Tomás Antônio Gonzaga himself. Other revolts against the Crown (mostly tax-related) were plotted by members of the high society, such as that of São Romão in 1739, and the Revolt of Felipe dos Santos in 1720, which was the first time that a Governor executed a rich, white man in the colony. |

| 20 | (Souza [1999] 2006, p. 168). For more on the coartação, how it differed from the conditional manumission, and the political condition of the freed population, see the whole chapter in (Souza [1999] 2006, pp. 151–74). |

| 21 | (Schwarcz and Starling 2015, p. 126). In the year 1776, Minas Gerais was composed of 25,7% of mestiços, exceeding the 22.1% of white individuals, while 52,2% of the population was Black. Data from 1821 show that being a mestiço represented an advantage in the slavery system: 149,635 mestiços were free, against only 51,544 Black individuals. In percentages, 14,4% of the total mestiço population was enslaved, while among the Black population, the number rose to 75.6%. For more data see: (Maxwell [1973] 2004). See also (Tribe 1996). |

| 22 | Not exactly the rule, and yet far from being just an exception, the famous biographies of Chica da Silva and Matias de Crasto Porto embody this somewhat authorized social and economic ascension among the people of color in eighteenth-century Minas Gerais. Matias de Crasto Porto was the classic type of wealthy man during the heyday of the mining society. His inventory of 1742 shows a diversified economic activity based on investments, garnishments, and credits, and dependent on a high number of enslaved people. The presence in the inventory of sumptuous pieces and luxurious fabrics suggests connections with international trade and the adoption of a lifestyle consistent with that of the European wealthy classes. When Crasto died, all his possessions were inherited by his illegitimate, mestiço children. Chica da Silva constitutes a more famous case. The daughter of a Portuguese man and an enslaved woman, she was born into slavery but granted freedom in adulthood by her former master and later life partner, João Fernandes de Oliveira. Although they were never officially married, they had many children together who received noble titles in the Portuguese court. Adopting the name of Francisca da Silva de Oliveira, Chica da Silva became one of the richest and most influential women of Minas Gerais. |

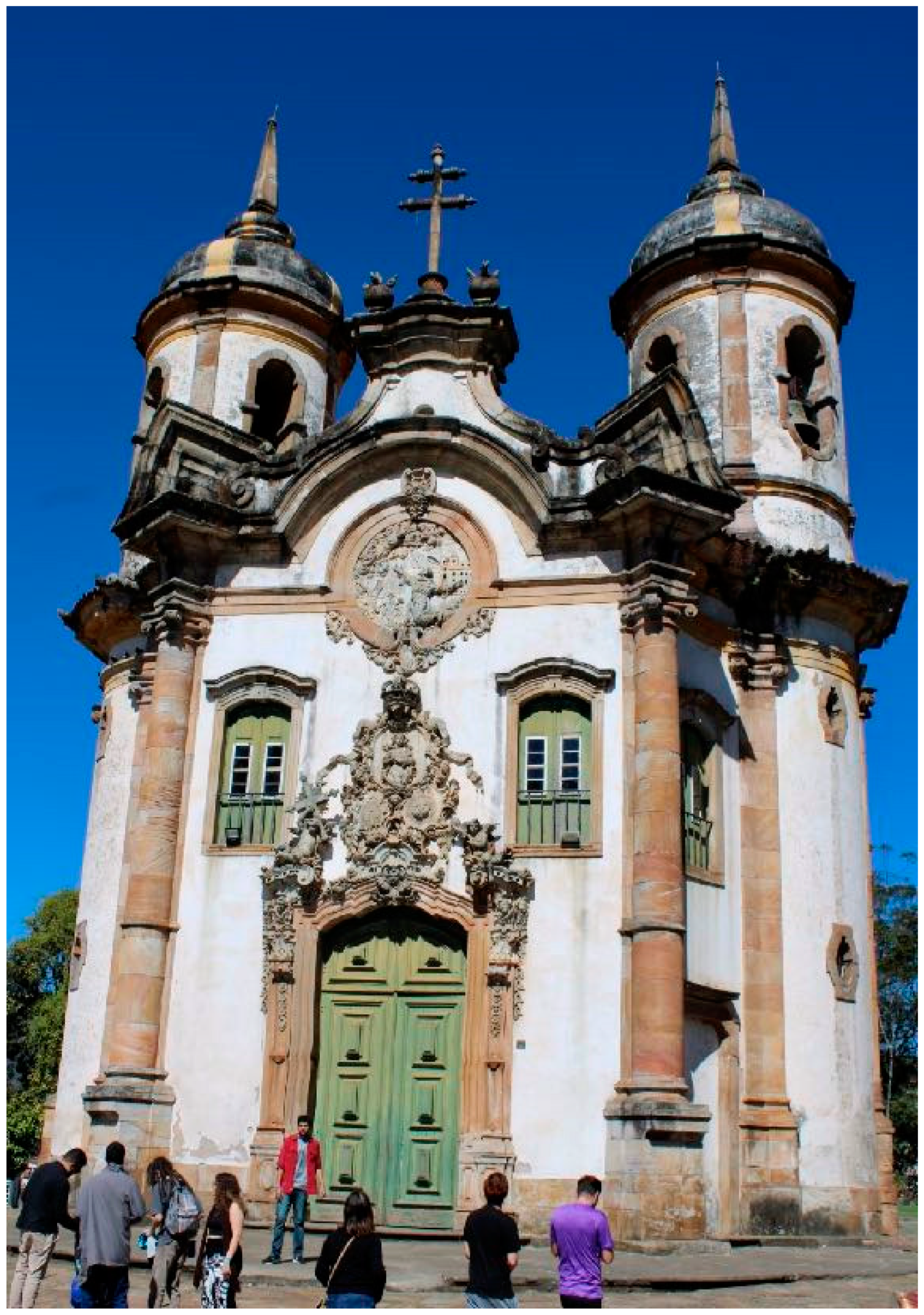

| 23 | Mário de Andrade had been traveling to the colonial cities of Minas Gerais from 1917 onwards, which made him a natural leader in the modernist trip of 1924. |

| 24 | I will from now on often refer to Mário de Andrade and Tarsila do Amaral by their first names, with the familiarity customary to Brazilian readers. |

| 25 | (do Amaral 1923, p. 2). “Caipira” is the Portuguese word that describes the simple people from the countryside. For Brazilians, the word refers to things and people that are provincial, simple, or naive. While the word can sometimes acquire a pejorative connotation, Tarsila uses it as an opposition to the cosmopolitan city and international academicism. This influenced Tarsila’s view of the region and relates to the particularities of primitivism in Brazilian modernism. Primitivism, here, is manifested by a certain nativist interest and the belief in the purity of mineiro region. Purity, naïveté, and simplicity, in turn, relate to the idea of “original”, and “primary”. Throughout Mário’s essays, which will be discussed below, “primitive” mostly relates to the originating, foundational, and primordial. |

| 26 | Camila Maroja, “From São Paulo to Paris and Back Again”, Stedelijk Studies, Issue #9 Modernism in Migration (Maroja 2019): 4. Translation by Camila Maroja. (Maroja 2019). |

| 27 | The first text is divided into two publications in February and June of 1920. Strangely enough, the February edition contains the word “conclusion” after the title despite being the first publication. The text published in February attempts to be an introduction to religious art in Brazil, while the one of June focuses solely on Minas Gerais. |

| 28 | While the Church of São Pedro dos Clérigos is attributed to the Portuguese architect Antônio Pereira de Sousa Calheiros, many professionals partook in the construction of the church in São João del Rei. Germain Bazin’s attribution to the Portuguese Francisco de Lima Cerqueira is still valid since he can be identified as the author of the frontispiece and the octagonal towers, but these are later developments to the original project, whose author remains unknown. Two further lateral altars are attributed to Joaquim Francisco d’Assis Pereira, a native of São João del Rei. See (Bazin 1956) and the collection Roteiros do Patrimônio: (de Oliveira and dos Santos 2010a, p. 133) and (de Oliveira and dos Santos 2010b, p. 67). |

| 29 | (de Andrade 1920b, p. 105). Regarding the association between the elliptical floor plans in Minas Gerais and Francesco Borromini’s work in Rome, see (Bury 1955). |

| 30 | (de Andrade 1920a, p. 96). Mário also praises the modern architect Georg Przyrembel, who would be responsible for the architecture section at the Modern Art Week of 1922, for being able to find inspiration in traditional architecture. See (de Andrade 1920b, p. 111). |

| 31 | “um surto coletivo de racialidade brasileira”. See (de Andrade [1928] 1984, p. 13). |

| 32 | (de Andrade [1928] 1984, pp. 14–16). Later in the text, Mário nevertheless elevates the condition of “mestiço” above nationality: “[Aleijadinho] is a mestiço more than a fellow countryman. He is just Brazilian because he happened to be in Brazil”. See (de Andrade [1928] 1984, p. 42). |

| 33 | (de Andrade [1928] 1984, p. 30). The attribution of the church of Saint Francis of Assisi in São João del Rei to Aleijadinho is not unanimous. According to some scholars, the church was designed by Aleijadinho, who was also responsible for the medallion on the façade, some of the sculptures in the interior, the first two altars next to the chancel arch, and the image of St. John the Apostle. The high altar was also designed by the artist but has been completely altered by Francisco Lima Cerqueira and Luís Pinheiro. Francisco de Lima Cerqueira produced almost all the sculptures and carvings seen in the church. A famous sketch of the church’s facade, believed to be by Aleijadinho, is displayed as such at the Museu da Inconfidência in Ouro Preto. |

| 34 | (de Andrade [1928] 1984, pp. 41–42). About the nature of such “deformations”, Mário draws, earlier in the essay, an opposition between “plastic” and “expressionistic” characteristics. He suggests a first stage of “healthy” plastic alteration of the imported European conventions, and a second stage of adaptations of “expressionistic and gothic” nature that obey the artist’s inner emotions and are connected to the artist’s disability and physical suffering. The intention is clearly to connect the deformations in Aleijadinho’s art to the ones in his body. Furthermore, since Mário attributes the plastic phase to the localities of Ouro Preto and São João del Rei (where his major architectural projects are), while the expressionistic phase is connected to Congonhas (where his major sculptural work is), one can argue that the discussion of “plastic” and “expressionistic” deformations could also reflect an opposition between curvilinear architecture and sculpture. |

| 35 | See, among others, (Smith 1939); (Smith 2012); (Levy 1944); (Keleman 1951); (Bury 1955); (Bazin 1956); (Bury 2006). |

| 36 | This association was first drawn by Bury. See (Bury 1955). |

| 37 | The treatise was in fact once part of a library collection in Minas Gerais but got lost at some point and is now untraceable. See (de Oliveira Pedrosa 2018) and (Bazin 1963, pp. 88–89). Through what other means Aleijadinho might have learned his trade is also debatable. According to Bretas, he learned to draw mostly from his father, the Portuguese architect, and the painter João Gomes Batista. Bretas also assumes that Aleijadinho may have visited elementary school and had some knowledge of Latin. In a country of illiterates, Aleijadinho also knew how to read and write (Bretas 1858a). Germain Bazin argues that Aleijadinho then learned woodcarving with José Coelho de Noronha. Meanwhile, the historian and preservationist Rodrigo Melo Franco sustained that the woodcarver Francisco Xavier de Brito had a significant influence on Aleijadinho’s artistic education. Acknowledging the question of where Aleijadinho might have learned his trade as a major problem for art historians working with colonial Minas Gerais, James E. Hogan collected in 1981 a bibliography on this subject (Hogan 1981). For more recent studies, see André Guilherme Dornelles Dangelo (Dangelo 2006), A cultura arquitetônica em Minas Gerais e seus antecedentes em Portugal e na Europa: Arquitetos, mestres-de-obras e construtores e o trânsito de cultura na produção da arquitetura religiosa nas Minas Gerais setecentistas, Ph.D. dissertation, UFMG, 2006; and André Guilherme Dornelles Dangelo, “As gravuras e a tratadística em circulação nas Minas Gerais setecentistas e sua influência na produção da obra de Antonio Francisco Lisboa (1738–1814)”, Simposio Internacional Arte, Tradición y Ornato en el Barroco, (Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 2017). Myriam de Oliveira’s publication O Aleijadinho e Sua Oficina—Catálogos das Esculturas Devocionais (de Oliveira 2022) focusses on Aleijadinho’s work as a sculptor, and emphasizes his workshop and cooperation with further professionals, thus exploring the question of authorship and training. |

| 38 | For an introduction to the theorization of mestiçagem, mestizage, and afroamericanism in the broader Latin American context in the 20th century, refer to (Valdés 2000). |

| 39 | Although the overlapping time frame is striking, it is not known to me whether Guido and Mário were familiar with each other’s work. |

| 40 | Lezama Lima defined the inclusion of Inca symbols into the Herrerian buildings as the “Inca rebellion”, which is resolved in an “egalitarian contract” once Inca “cultural and racial” elements are forced to be admitted into the repertoire of Hispanic forms. Similarly, Lima argues that Aleijadinho “symbolizes the artistic rebellion of the Black”, while his triumph is “to question the stylistic models of his time, forcing upon them his own”, thus signaling the country’s readiness for rebellion. Interestingly, Lima subordinates “lo lusitano” to Hispanic identity and appropriates Aleijadinho as the “culmination of the American Baroque”, or of “our Baroque”. See (Lima [1957] 2017). See also (Salgado 1999). |

| 41 | The question of the differences between the Baroque in Brazil and in Spanish America is relevant at this point. Hispanic hybridizations such as the Andean Baroque produced astonishing works of architecture that conjugate pre-Columbian symbols and the imported Herrerian style, like the Church of San Lorenzo de Carangas in Potosí, Bolívia. Meanwhile, the incorporation of Indigenous and/or African imagery into the Baroque buildings in Minas Gerais is harder to grasp at first sight, though it is verifiable in specific situations. Agreeing with Gilberto Freyre, in 1939 the American art historian Robert Chester Smith had already made this point, by stating “from all the former European colonies in the New World it was Brazil that most faithfully and consistently reflected and preserved the architecture of the mother country”. See (Smith 1939); and (Freyre 1937). |

| 42 | (de Andrade [1928] 1984, p. 13). Italics are mine |

| 43 | (de Andrade [1928] 1984, p. 25). Italics are mine. |

References

- Amaral, Aracy. 1997. Blaise Cendrars no Brasil e os Modernistas. São Paulo: Editora, p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Antonil, André João. 2011. Cultura e Opulência do Brasil por suas Drogas e Minas. Brasília: Edições do Senado Federal. First published 1711. [Google Scholar]

- Avancini, José Augusto. 1994. Mário e o Barroco. Revista Instituto Estudos Brasileiros 36: 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazin, Germain. 1956. L’Architecture Religieuse Baroque au Brésil. Tome I. São Paulo: Museu de Arte. [Google Scholar]

- Bazin, Germain. 1963. Aleijadinho et la Sculpture Baroque au Brésil. Paris: Le Temps. [Google Scholar]

- Bretas, Rodrigo José Ferreira. 1858a. Traços biographicos relativos ao finado Antonio Francisco Lisboa, distincto escultor mineiro, mais conhecido pelo appellido de—Aleijadinho. Correio Official de Minas, August 19, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bretas, Rodrigo José Ferreira. 1858b. Traços biographicos relativos ao finado Antonio Francisco Lisboa, distincto escultor mineiro, mais conhecido pelo appellido de—Aleijadinho. Correio Official de Minas, August 23, 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Bretas, Rodrigo José Ferreira. 2002. Antônio Francisco Lisboa O Aleijadinho. Belo Horizonte: Editora Itatiaia. First published 1858. [Google Scholar]

- Bury, John. 1955. The Borrominesque Churches of Colonial Brazil. Art Bulletin XXXVII: 103–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bury, John. 2006. Arquitetura e Arte no Brasil Colonial. Myriam Ribeiro de Oliveira (org). Brasília: IPHAN. [Google Scholar]

- Cândido, Antonio. 2006. Literatura e Sociedade. Rio de Janeiro: Ouro sobre azul. [Google Scholar]

- Cândido, Antônio. 1975. Formação da Literatura Brasileira (Momentos Decisivos). Belo Horizonte—Rio de Janeiro: Editora Itatiaia. [Google Scholar]

- de Andrade, Mário. 1920a. Arte Religiosa no Brasil: Conclusão. Revista do Brasil 50: 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- de Andrade, Mário. 1920b. Arte Religiosa no Brasil. Revista do Brasil 54: 102–11. [Google Scholar]

- de Andrade, Mário. 1984. O Aleijadinho. In Aspectos das Artes Plásticas no Brasil. Belo Horizonte: Editora Itatiaia, pp. 11–42. First published 1928. [Google Scholar]

- de Andrade, Rodrigo Melo Franco. 1938. Contribuição para o estudo da obra do Aleijadinho. Revista do Patrimônio 2: 255–64. [Google Scholar]

- de Grammont, Guiomar. 2008. Aleijadinho e o Aeroplano. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, Myriam Andrade Ribeiro. 1985. Aleijadinho Passos e Profetas. Belo Horizonte: Editora Itatiaia. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, Myriam Andrade Ribeiro. 2014. Aleijadinho e o IPHAN: De Rodrigo Ferreira Bretas a Rodrigo Melo Franco de Andrade. In A Terra mais Perto do Céu. Brasília: IPHAN. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, Myriam Andrade Ribeiro. 2022. O Aleijadinho e Sua Oficina—Catálogos das Esculturas Devocionais. São Paulo: Capivara. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, Myriam Andrade Ribeiro, and Olinto Rodrigues dos Santos. 2010a. Ouro Preto e Mariana. Brasília: IPHAN, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira, Myriam Andrade Ribeiro, and Olinto Rodrigues dos Santos. 2010b. São João del Rei e Tiradentes. Brasília: IPHAN, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira Pedrosa, Aziz José. 2018. Modelos, formas e referências para os retábulos em Minas Gerais: O caso do tratado de Andrea Pozzo. Revista Historia Autónoma 13: 103–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Amaral, Tarsila. 1923. O estado actual das artes na Europa, Tarsila do Amaral, a interessante artista brasileira, dá nos suas impressões. Correio da Manhã, December 25. [Google Scholar]

- Dangelo, André Guilherme Dornelles. 2006. A Cultura Arquitetônica em Minas Gerais e Seus Antecedentes em Portugal e na Europa: Arquitetos, Mestres-de-Obras e Construtores e o Trânsito de Cultura na Produção da Arquitetura Religiosa nas Minas Gerais Setecentistas. Ph.D. dissertation, UFMG, Belo Horizonte, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Dangelo, André Guilherme Dornelles. 2017. As gravuras e a tratadística em circulação nas Minas Gerais setecentistas e sua influência na produção da obra de Antonio Francisco Lisboa (1738–1814). In Simposio Internacional Arte, Tradición y Ornato en el Barroco. Belo Horizonte: Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. [Google Scholar]

- Freyre, Gilberto. 1937. Sugestões para o estudo da arte brasileira em relação com a de Portugal e a das colônias. Revista do Patrimônio 1: 41–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzaga, Tomás Antônio. 2006. Cartas Chilenas. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, James E. 1981. The Contemporaries of Antonio Francisco Lisboa: An Annotated Bibliography. Latin American Research Review 16: 138–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keleman, Pál. 1951. Baroque and Rococo in Latin America. New York: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Hannah. 1944. Modelos europeus na pintura colonial. Revista do Patrimônio 8: 7–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, José Lezama. 2017. La Expresión Americana. Ciudad del México: Tierra Firme. First published 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, Lourival Gomes. 2003. Barroco Mineiro. São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva. First published 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Maroja, Camila. 2019. From São Paulo to Paris and Back Again. Stedelijk Studies 9: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, Kenneth. 2004. Conflicts & Conspiracies. Brazil and Portugal 1750–1808. New York and London: Rutledge. First published 1973. [Google Scholar]

- de Menezes, Ivo Porto. 1978. Manuel Francisco de Araújo. Revista do SPHAN 18: 83–114. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, César Augusto. 1999. Hybridity in New World Baroque Theory. The Journal of American Folklore 112: 316–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarcz, Lilia M., and Heloisa M. Starling. 2015. Brasil: Uma Biografia. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Stuart B. 1988. Segredos Internos—Engenhos e Escravos na Sociedade Colonial 1550–835. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Robert Chester. 1939. The colonial architecture of Minas Gerais. Art Bulletin 21: 110–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Robert Chester. 2012. Robert Smith e o Brasil—Vol. 1—Arquitetura e Urbanismo. Nestor Goulart Reis Filho (org). Brasília: IPHAN. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, Laura de Mello e. 2006. Norma e Conflito. Aspectos da História de Minas no Século XVIII. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG. First published 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, Laura de Mello e. 2006. O Sol e a Sombra Política e Administração na América Portuguesa do Século XVIII. São Paulo: Companhia Das Letras. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, Laura de Mello e. 2022. O Jardim das Hespérides. Minas e as Visões do Mundo Natural no Século XVIII. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. [Google Scholar]

- Tribe, Tania Costa. 1996. The Mulatto as Artist and Image in Colonial Brazil. Oxford Art Journal 19: 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, Eduardo Devés. 2000. Afroamericanismo e identidad en el pensamiento Latino-Americano en Cuba, Haiti y Brasil, 1900–1940. Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies/Revue canadienne des études latino-américaines et caraïbes 25: 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weddigen, Tristan. 2017. Hispano-Incaic Fusions: Ángel Guido and the Latin American Reception of Heinrich Wölfflin. Art in Translation 9: 92–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ammann, L. Aleijadinho’s Mestiço Architecture in Eighteenth-Century Brazil: Inventing Brazilian National Identity via a Racialized Colonial Art. Arts 2023, 12, 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12050214

Ammann L. Aleijadinho’s Mestiço Architecture in Eighteenth-Century Brazil: Inventing Brazilian National Identity via a Racialized Colonial Art. Arts. 2023; 12(5):214. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12050214

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmmann, Laura. 2023. "Aleijadinho’s Mestiço Architecture in Eighteenth-Century Brazil: Inventing Brazilian National Identity via a Racialized Colonial Art" Arts 12, no. 5: 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12050214

APA StyleAmmann, L. (2023). Aleijadinho’s Mestiço Architecture in Eighteenth-Century Brazil: Inventing Brazilian National Identity via a Racialized Colonial Art. Arts, 12(5), 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts12050214