2.1. Drawings of the City Walls and Towers of Towns and Cities including Their Castles and/or Citadels

2.1.1. Alcalá la Real (Figure 3)

Alcalá la Real is depicted in fol. 26 of

Ms. 1180 B.N. (

Mozas Moreno 2018, p. 347). In fols. 163 and 203v, he also wrote the name of the town, but only added the drawing of its coat of arms and a text note on the first of these, leaving the rest of these folios blank.

Figure 3.

Sketch of Alcalá la Real drawn by Martín Ximena Jurado. Ms. 1180 B.N., fol. 26.

Figure 3.

Sketch of Alcalá la Real drawn by Martín Ximena Jurado. Ms. 1180 B.N., fol. 26.

On the back of fol. 26, there is text with different spelling signed by Francisco de Bilches Pedraza (1575–1649), the Jesuit in charge of the excavations in the Alcázar of Baeza between 1629 and 1640. Given the format of the paper, which is different from that of most sheets of the manuscript, and the way that it had been folded, not coinciding with the limits of these folios, it might have been a letter sent to Ximena Jurado where he reused the blank side.

Alcalá la Real is labelled and underlined in lighter ink at the head of the page, and three walled enclosures are depicted in black.

The lowest of these contains the name of the town in black ink with the same spelling and writing style as the title. This must have been the only text that accompanied the drawing initially, as all the others are in lighter ink. A church, labelled “Santo Domingo de Silos”, was drawn in the lower enclosure. The wall that encloses it from below and from the sides has 10 towers and three gates, while the wall that separates it from the main enclosure of the city has four towers and two gates.

This central enclosure is presided over by the church of “Santa María”, which appears with a line running through it, as if it has been crossed out. It is included in an inner enclosure with five wall towers and what appears to be a larger bell tower. Beneath, there are up to four enclosures and just as many gates, two of which are crowned with a tower. The walled perimeter has 19 towers and three gates. On the left side of the sketch, there is a tower that appears to be free-standing to which a gate is appended, but next to which one can read the following text in red: ‘Here the wall meets this large tower and where they join, there is a gate’.

In the upper right-hand corner, the motte fortress is drawn with its main tower and two stretches of wall that connect to the perimeter ramparts.

Folio 163 seems to have been intended to contain information about Alcalá la Real, as is stated in black, but it only contains the drawing of the coat of arms of the city and the following text: ‘There are those who write that this city is the one that Ptolemy calls Calicula. But it does not seem to have enough foundation: I noticed in that town when I was there, that it has no trace of anything Roman, but only of Moors’.

On the other hand, in fol. 203v, on the back of the map with the description of the kingdom and bishopric of Jaén from 1641, he also noted “Alcalá la Real, o de Abenzaide”, but the sheet remained blank.

Alcalá la Real has the typical layout of a city from al-Andalus: a castle or citadel, an alcazaba or fortified upper quarter, the medina as an extension or continuation of the citadel, and an outer enclosure in the form of a suburb (

Eslava Galán 1999, pp. 365–72). The fortified city is located on a hill whose summit is more than 1030 m above sea level, on a plateau covering three hectares, at one of the vital points on the route linking Cordoba with Granada. The natural escarpments, which are very steep, with slopes of almost 100 m above the surrounding territory, contributed to the creation of great defensive elements.

The origin of the walled enclosure can be dated back to around 727, when the fortress was built by Bādīs b. Ḥabūs, later becoming the centre of the Muladi rebellions against Cordoba in 889. The configuration of the defensive enclosure took its final shape during the Nasrid period in the second half of the 13th century, taking advantage of pre-existing fortifications that housed Qal‘at Banī Sa’īd, the castle of Benzayde or Abenzaide for the Christians. In 1340, Alfonso XI of Castile laid siege to the city, making it surrender in 1341 after large breaches were inflicted on the outer wall. The Crown of Castile called it the Fortress of Alcalá la Real or Ciudadela de La Mota, and great effort was made to repair and upgrade it due to its strategic position on the main road from Cordoba to Granada (

Eslava Galán 1999, pp. 365–72).

Being an archaeological site, material dating back to prehistoric times has been found in the fortress. Excavations have revealed that the intense use of the citadel between the 14th and 16th centuries led to the destruction of the levels of most of the structures from the Andalusi period. Along with numerous elements from the last phase of occupation between the 16th and 17th centuries, a large number of storage structures from the Roman period were found, which may have been used as medieval cisterns or silos, such as those located around the Iglesia Mayor Abacial, built in the 14th century (

Moya García 1999a, pp. 132–44;

1999b, pp. 288–300;

Calvo Aguilar and Pérez Arjona 2012, pp. 1187–95).

The general layout of this city in al-Andalus was organised into several fortified complexes. The most important enclosure was to the citadel, located on the broad plateau that crowns the motte. The interior space was divided by a wall that ran from north to south, creating a larger space to the west and another to the east, which is where the citadel itself and the Iglesia Mayor Abacial are located today. The citadel is composed of masonry and is the result of repairs carried out after the Castilian conquest. A large part of this complex was surrounded by a first stretch of wall that encircled the rest of the medina. It was originally built of rammed earth, but was later covered, and in some cases replaced, by masonry walls. These were reinforced at irregular intervals by towers, some circular and others rectangular.

This would have been the primitive village nucleus of Alcalá and its interior could be accessed via a pathway embedded within the walls that ascended from the north-eastern part of the outskirts of the city to the citadel. It included different gates such as Puerta de Santiago, Puerta de San Bartolomé, Puerta de la Imagen, Puerta de la Plaza, and Puerta del Peso de la Harina.

In addition to the upper enclosure, the progressive increase in population led to the occupation of land on the eastern slope, which made it necessary to enclose other areas with walls of which there are still remains. This first enclosure used to be the outer defences of the medina, and is formed by a large stretch of wall that encircles the south-eastern slope of the motte. Its first layout may have been built around the 11th and 12th centuries in rammed earth or mortar, and covered between the 13th and 14th centuries with thick masonry walls (

Castillo Armenteros and Castillo Armenteros 1997).

This other walled enclosure would have protected the so-called Arrabal Viejo or Arrabal de Santo Domingo, located on the eastern slope of the motte under the citadel’s protection, acting as the left flank of the main entrance to the fortress.

Depicted in fol. 63 of

Ms. 1180 B.N. (

Mozas Moreno 2018, p. 353), there is a very simple sketch of the Rock of Martos seen from the north, crowned by the upper fortress. Fols. 151v and 158 are labelled with the name of the town, but were otherwise left without content.

Figure 4.

(

a) Sketch of La Peña de Martos (the Rock of Martos) drawn by Martín Ximena Jurado.

Ms. 1180 B.N., fol. 63; (

b) Another drawing with the city of Martos, published in 1643 in his book about the history of the city of Arjona (

Ximena Jurado 1643, p. 162. Arjona Municipal Archive).

Figure 4.

(

a) Sketch of La Peña de Martos (the Rock of Martos) drawn by Martín Ximena Jurado.

Ms. 1180 B.N., fol. 63; (

b) Another drawing with the city of Martos, published in 1643 in his book about the history of the city of Arjona (

Ximena Jurado 1643, p. 162. Arjona Municipal Archive).

In the chapter on Latin inscriptions on stone supports located ‘in the district of Martos of the Order of Calatrava, in Martos’ (fols. 60–70), the Rock of Martos is represented in a frontal view, with a very simplified image of the northern elevation of the high fortress, with its circular towers and the gate on this flank (fol. 63). In this sketch, however, in the motif is not that of the said fortress, but the existing Latin inscriptions: ‘On the Rock of Martos, [there is] an altar and idol chapel carved with these letters’ and ‘on the corner of a tower in the wall next to the houses of Bernardino de Avoz’, already in the urban area. In fol. 70 of Ms. 1180 B.N., he introduced a drawing with the ‘arms of Martos, castle of its colour in a field of gold in this form the castle on the rock’, which alluded to the iconic image of this rock fortress.

Another drawing of the ‘altar and idol chapel’ labelled ‘The Town of Martos: Colonia Augusta Gemella Tuccitana’ was introduced in his book

Anales de la ciudad de Arjona (

Ximena Jurado 1643, p. 162). In this work, they are represented in a pseudo-perspective formed by elevations in a succession of planes containing the towers, walls, and individualised dwellings with gabled roofs of the village of Martos in its lower part as well as the high fortress in the upper part.

There were two fortifications in Martos: the one at the rock was a magnificent castle located at an altitude of more than 1000 m above sea level, and the one in the town around 774 and to the north-west of the aforementioned high promontory.

In the walled enclosure that surrounded Martos, which was oval-shaped in an east–west direction, the low fortress is represented in the form of a towered bastille. Some remains of this fort can still be seen such as the keep, the Almedina (the tower of the city), and the Albarrana

5 as well as sections of the city wall. Although it is not represented, on the other side of the hill, there was another wall that started at the foot of the rock and reached the high fortress.

During the Late Middle Ages, the Command of the Calatrava Military Order controlled this region. They built their main castle on top of La Peña of Martos as a symbol of their power in this region. This fortification had a key role in protecting this territory from attacks from the Nasrid kingdom of Granada during the 13th to the 15th century (

García-Pulido et al. 2020).

Some scholars have argued that there was already a fortification on La Peña at that time, which would have controlled this territory (

Gutiérrez Pérez 2009a, pp. 25, 52;

2013, pp. 11–16). In 1224, Ferdinand III of Castile began the first military incursions into the upper Guadalquivir Valley, supporting the local ruler of Baeza (al-Bayyāsī). In the Navas de Tolosa Treaty (1225) between the two parties, the Castilian king gained Martos. Ferdinand III initially entrusted Count Álvar Pérez de Castro with Martos. The brother of the Almohad Caliph, Abū-l-‘Ulā, laid siege to the settlement in 1227 (

Olivares Barragán 1992, p. 180). The fortified city withstood the assault, but La Peña fell into the attacker’s hands. After these events, at the end of 1228, the Castilian king entrusted the Order of Calatrava with the defence, rule, and organisation of Martos and its surroundings (

Gutiérrez Pérez 2009b, pp. 34, 48) including Víboras and Porcuna (

Ruiz Fúnez 2010, p. 154).

In 1238, the first ruler of the Nasrid Dynasty, Muḥammad I, laid siege to the fortress. Seven years later, Martos was surrounded by an army from Granada during a raid. However, the intent to take the fortress failed because of the support from the forces sent by Ferdinand III. The city was also the home base of the Castilian conquest of Jaén, which ended in 1246. From them on, the Nasrid border came to lie to the south of the Command of Martos.

After the death of Ferdinand IV of Castile in 1312, a new period of instability began. The Nasrid king Ismaīl I seized the opportunity to launch one of the most intense attacks on the district of Martos. This happened in 1325, after the defeat of a Castilian inroad against Granada. The sultan subjected Martos to an exhausting siege in which gunpowder was used for the first time in this territory (

Eslava Galán 1990, pp. 155–56;

1999, pp. 225–30). According to Ibn al-Jaṭīb, the city was taken, raided, and destroyed (

Burgos Núñez 1998, pp. 37–45), although the castle of La Peña was not conquered. During the 15th century the pressure from Castile moved the border further south (

Castillo Armenteros and Alcázar Hernández 2006, pp. 171, 173), which did not prevent the Nasrid operations against the city during the next few decades. Among the most important ones was the attack by Abū-l-Ḥassān ‘Alī’s army (Nasrid king from 1464 to 1482 and from 1483 to 1485). All of these assaults forced the Order to adapt their fortresses, until the instability of the border land disappeared after the conquest of Granada in 1492. From then on, the castle of La Peña was gradually abandoned until it fell into ruin (

García-Pulido et al. 2020, pp. 1–29;

García-Pulido and Navarro Palazón 2023, pp. 145–52).

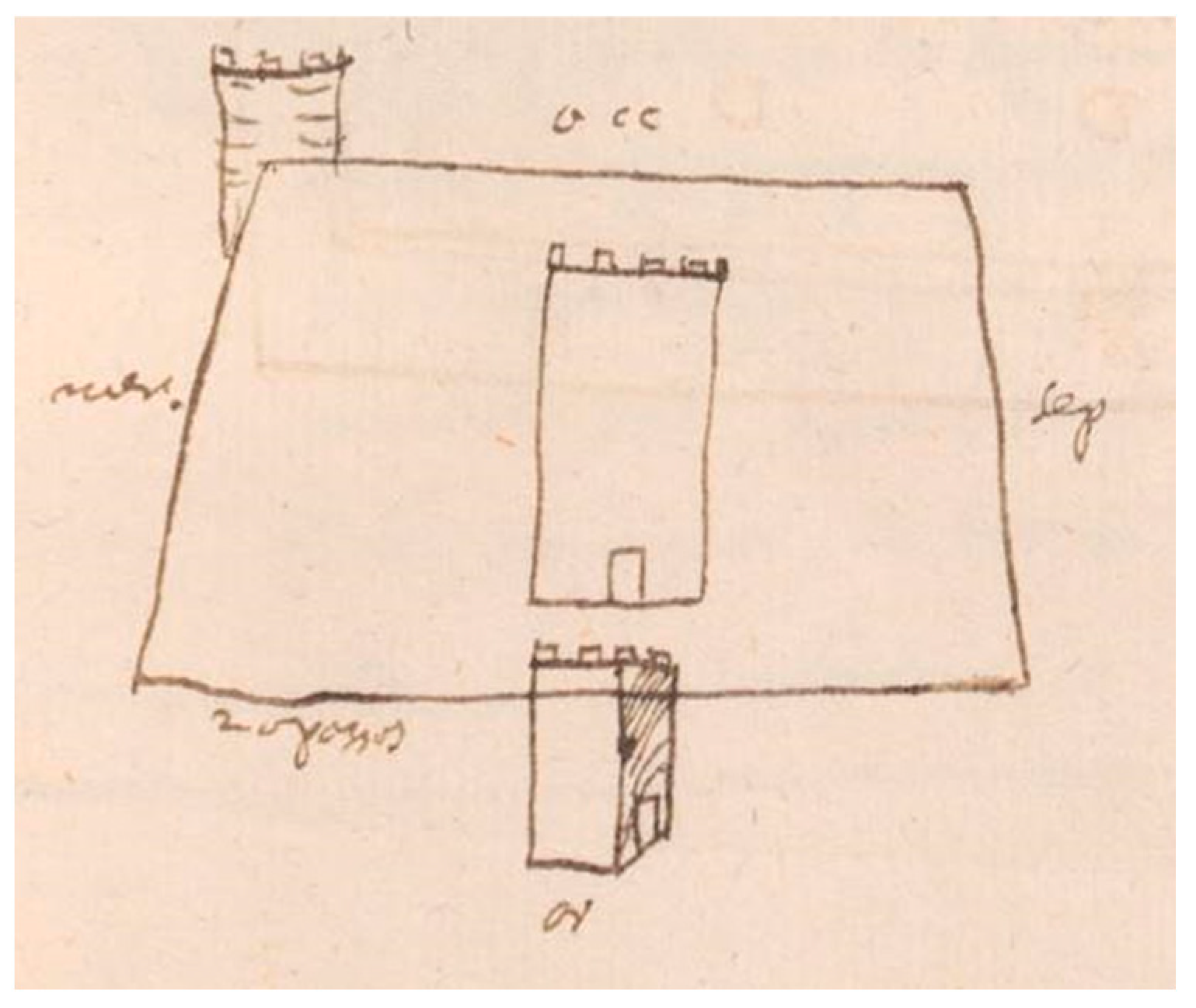

2.1.3. Castle of Linares (Figure 5)

This is sketched twice in fols. 109v and 110 of the Ms. 1180 B.N., the second of which is labelled “Armas de la villa de Linares” (‘Arms of the town of Linares’) with a lighter ink. This municipality appears on the list of places in the bishopric of Jaén in fols. 133 recto and verso, but he did not dedicate a complete folio to it.

Figure 5.

Two sketches of the castle of Linares drawn by Martín Ximena Jurado. Ms. 1180 B.N., fols. 109v (a) and 110 (b).

Figure 5.

Two sketches of the castle of Linares drawn by Martín Ximena Jurado. Ms. 1180 B.N., fols. 109v (a) and 110 (b).

At the end of the chapter that Ximena Jurado dedicated in

Ms. 1180 B.N. to the antiquities ‘in the town of Linares’ (fol. 96v) and ‘in Cazlona [Cástulo]’ (fol. 97), in fol. 109v, he introduced two fragments of inscriptions that would be ‘in the door of the ante-wall of the castle of Linares’ and ‘in the tower of the door of the castle of Linares’. He accompanied them with a pseudo-perspective sketch of the castle, although he did not label the name, as he did in fol. 110 (

Eslava Galán 1999, pp. 362–65).

In this first sketch (fol. 109v), he indicated that the inner walled enclosure would have been 28 paces on the north and south sides and 22 on the east and west walls. It would have had five cylindrical crenellated towers, four on the corners with access from the parapet, where battlements are depicted on two sides, and one on the south wall. The crenellated gate-tower would be prismatic and closer to the north-west corner tower. The outer wall would have been 38 paces on the north and south walls and 32 on the east and west, with some cylindrical towers without battlements and a crenellated tower with arrow slits protecting the bridge to the east, which spanned the moat to an open gate in the outer wall. Initially, there may have been an albarrana tower on this site, possibly of a different shape, isolated from the whole, until the parapet and moat were added.

In the sketch in fol. 110, he gave the same dimensions: from the eastern (left) to the western (right) front ‘28 paces through the hollow’, and from the northern (bottom) to the southern (top) ‘22 paces, through the hollow’. Its perimeter was ‘140 paces on the outside, square in shape’. This castle would have had a wall on which Ximena Jurado drew six cylindrical crenellated towers with access to a raised gate from the parapet, four at the corners, and one in the centre of the west and east sides. The square gate-tower with direct access would have been on the north front, and although he depicted it more or less in the centre of the canvas, he wrote ‘more distance’ next to the tower on the north-east corner. It would have had an ‘ante-wall’ that would also have had turrets, with a cylindrical tower without battlements but with arrow slits. It was located on the north side, protecting the bridge that crossed the moat to reach an open gateway over the ante-wall.

Francisco de Torres, in his history of Baeza, which he began around 1633 and finished in 1677, described this fortress as follows (

Mozas Moreno 2018, p. 354):

‘The castle of Linares is in the middle of the town, very old, strong and well built… It is adorned with six square towers, five round and one square, which rises above the gate facing north with a strong and high crenellated wall, which makes a spacious courtyard. It has another parapet with some towers, moats and loopholes, where a platform is formed, before entering the castle, and after the parapet, which at least takes more than 1500 fighting men, with a deep and narrow entrance.’

The enclosure may date from the 13th century, passing into Christian hands after the surrender of Baeza around 1227. They reinforced the fortress with machicolations and the raising of slender towers that protruded over the parapet to give them more autonomy, replacing the previous quadrangular and rammed earth towers with other cylindrical masonry towers. In the 15th century, this fortress took on an active role in the civil wars, which led to the reinforcement of the outer walls. The settlement that gave rise to Linares from Cástulo was formed around the castle.

The circular keep with an upper machicolation in the north-west corner is the only remaining defensive element of this castle, together with some parts of the wall. It was demolished between 1803 and 1804 by order of Francisco María Solano Ortiz de Rosas, Marquis of La Solana and General Captain of Andalusia.

In 2011, an archaeological intervention was carried out that revealed the existence of the remains of a second keep next to this tower, which could be the existing access to the northern interior wall of the castle. The work carried out revealed, next to the tower, the entrance bridge to the fortress as well as a double wall and what could have been a large religious building (

Martínez Aguilar 2012).

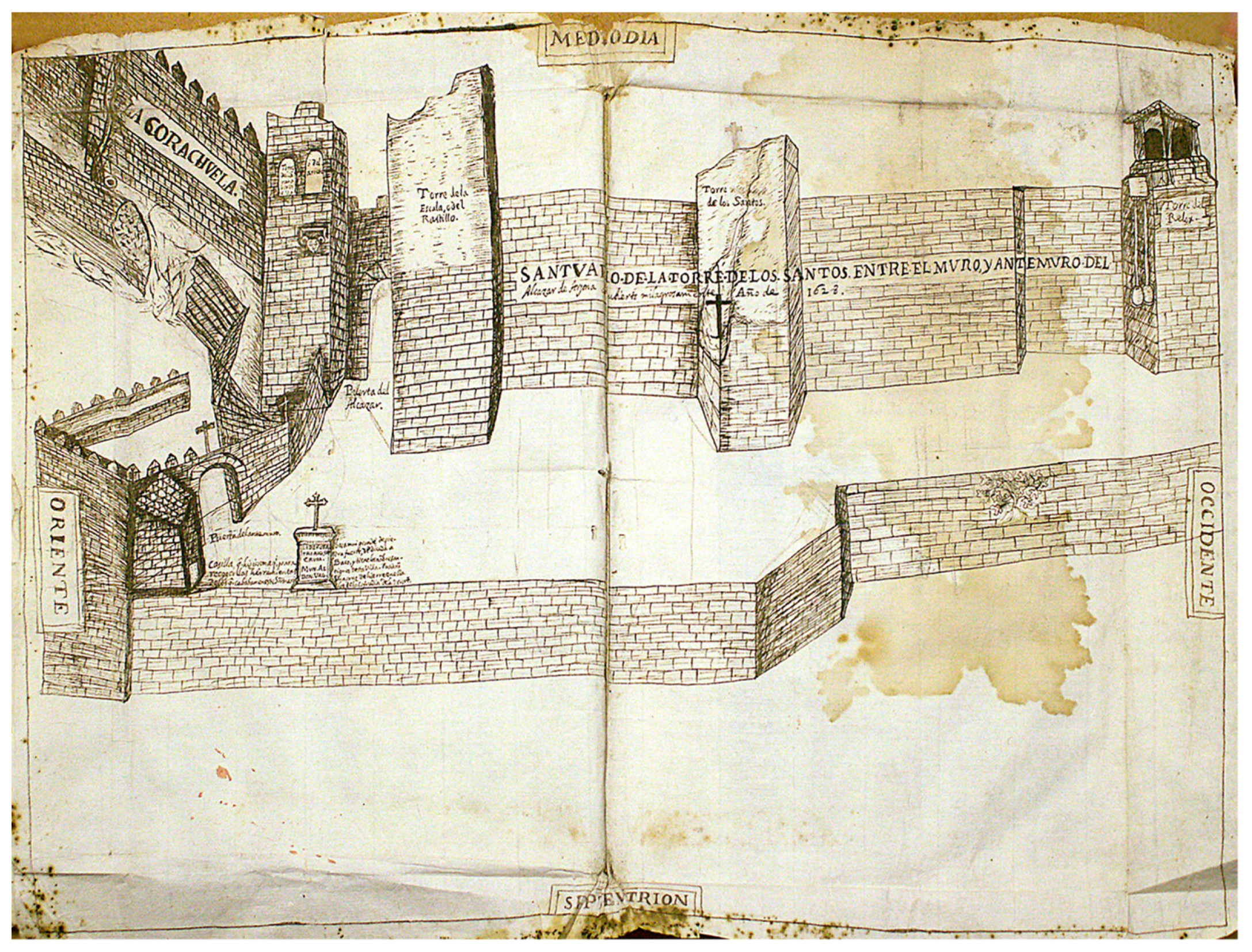

Ximena Jurado dedicated a large drawing to it in fol. 134 (

Mozas Moreno 2018, pp. 340, 343), which is larger than the rest of the sheets of

Ms. 1180 B.N. It contains one of the most elaborate sketches of this manuscript. It is framed by a double line on which it is written the year when Ferdinand III of Castile definitively conquered Baeza. This date seems to have been repainted in black ink, at least the last two digits, a correction that is more visible in the name of the municipality. Ximena Jurado seems to be putting forward a hypothesis of the walled structure of the city at the time of the Christian conquest. Nevertheless, the drawing shows urban elements that are anachronistic for this time such as the defensive elements of the city recently won from the Almohads, together with the main civil and religious buildings and public spaces that would have been built from that time onwards.

The drawing is made on a sheet of paper folded in four parts that is twice the size of the rest of the manuscript, so it may well be the insertion of a previously completed sheet, given that the annotations on the back have nothing to do with the sketch and are arranged differently in each of the quadrants. Furthermore, when this folio was inserted into the manuscript, it was cut out, which affected the text on the back, but not the text on the side on which the sketch is drawn.

Figure 6.

Sketch of Baeza drawn by Martín Ximena Jurado. Ms. 1180 B.N., fol. 134.

Figure 6.

Sketch of Baeza drawn by Martín Ximena Jurado. Ms. 1180 B.N., fol. 134.

The drawing was done in lighter ink, but several texts that had faded more were rewritten in darker ink, possibly not by Ximena Jurado himself. Although the form of the superimposed letters attempts to adapt to the initial writing, in other cases, terms were completed or duplicated with a different spelling. This can be seen in the cardinal points, which the author spelt as usual: “sep. [septentrional]” (northern), “merid. [meridional]” (southern), “occ. [occidental]” (western), “or. [oriental]” (eastern), and rewritten with the words “norte” (north) and “oeste” (west), or the abbreviations “m.” [meridies] (south) and “es.” [este] (east).

The drawing contains an abundance of text, both inside and outside the built spaces and at the foot of or next to the most important buildings. In addition, numbering was introduced with capital letters that refer to a legend with the names of the gates of Baeza. These are as follows:

‘A. Jaén Gate and its Tower of María Antonia.

B. Puerta del Rastro and Puerta del Barbudo.

C. Azacaya Gate.

D. Gate of the Schools and San León Gate.

E. Cañuelo Gate.

F. Úbeda Gate.

G. Quesada Gate.

H. Granada Gate.

I. Postigo Gate.

K. El Postigo.

L. Puerta del Conde de Haro.

M. That tower is the fourth tower of the Alcazar starting from the western and northern corner towards the south, it has an arch, and that arch is called Puerta del Lobo.

N. Puerta de los Cueros, one enters through it from the Alcazar to the village, and the tower is called Puerta de las Doncellas’.

Within the walls, at the centre of the image, there is text saying: ‘Baeza. Its wall has 1550 paces of circuit, and its Alcázar has 500, and the Alcazar and all the most ancient parts have their walls and antemurals’.

As religious buildings within the walls, “La catedral de Santa María” and the churches of San Miguel, San Pedro, San Gil, San Juan (on an initially crossed-out drawing of the cathedral), Santa Clara de Monjas, Santa Ana (with the name rewritten in a different type of ink and lettering), and the hermitage of San Benito were drawn and labelled. “Las escuelas” [the schools], “las escuelas Viejas” [the old schools], “Hospital de López Martínez”, and the space occupied by “Casa Real y Episcopal” were also highlighted.

In the western part, the enclosure of “El Alcázar” was depicted, protected by an outer wall. The enclosure of the castle was drawn standing on some rocks at the highest point, and on the other side of the exit, the palace. Further on, in the upper left-hand corner of the sketch, the icon of a tower represents the towns of Begíjar, Lupión, and, on the other side of the River Guadalimar (with “Bethis” crossed out), is the rewritten word “Castillo”, which in the original may have been “Cástulo”, together with some words that are unintelligible because they have been smudged with fresh ink, deliberately it seems, and between which vineyards were kept.

Other urban elements outside the walls included the fish, scriveners, and the firewood squares, the butcheries, the so-called “Taza” and “Cañuelo” fountains, the market, the road to Jaén, and the streets called “Las Barreras” and “La Merced” next to the enclosure of the convent of La Merced, which was marked with a cross. On the other side of this street, a broken row of undifferentiated houses was drawn on the elevation, the only residences represented in the sketch.

With a hexagonal prismatic shape, represented in axonometric view compared to the rest of the elements that are shown in a top–down elevation, the “Tower of the Altars where the soldiers are housed” (known today as Los Aliatares Tower) is drawn in hypertrophy, with a bugle-shaped pennant hanging from a mast hanging out of a window. That this tower has a rectangular prismatic shape has, in fact, nothing to do with Ximena Jurado’s detail.

The perimeter of the walls of Baeza was about 2.5 km long, with 53 towers or turrets and another six in the fortress. As for the gates, those at Barbudo, Azacaya, Cañuelo, and Úbeda were double, while the rest were single.

This settlement has a prominent position at the western end of the district of Las Lomas, dominating the Guadalquivir Valley, and the richness of its land has made human settlement possible since prehistoric times. It had precedents from the Bronze Age, in the Iberian period (when it was an important Oretan site), Carthaginian, and Roman times. The Andalusi fortification of Baeza would have had its origin in the works undertaken in 886 by the governor of Jaén. Shortly afterwards, the warlord Umar ibn Ḥafṣūn added the fortress to his domain and held it for almost 20 years.

During the 9th century, the kingdoms of Granada, Seville, and Almería were at war with each other. Alfonso VII of Castile conquered Baeza in 1146, but in 1157, it was taken back by the Almohads, only to be taken two years later by Ibn Mardanīsh of Murcia. During the reign of the Almohad Caliph Yūsuf I (1163–1184), the city must have been fortified as part of his construction programme.

On 21 July 1212, a few days after the Battle of Navas de Tolosa, the Christian army reached Baeza, finding it unguarded and deserted, although it was not taken. No major damage must have been caused to the defences, as they withstood a siege from 1224 to 1225 when a local warlord, al-Bayyāsī, rebelled against the Almohad Caliph al-‘Ādil. After this, the citadel finally came into the possession of the Castilians when al-Bayyāsī offered it in return for their help. After his death, the Mudejar population tried to recover it without success, and after the revolt was put down, they were exiled in 1226, when it began to be repopulated with Christian settlers. Fernando I ceded it as a lordship to the knight Sancho Sánchez, who in turn suffered a long siege by the Nasrid king in 1268. The place underwent further sieges in 1407, 1464, and 1475, the latter due to the Castilian Civil War (1351–1369). Within this walled enclosure were the castle-palace of the royal authority and the church, later converted into the collegiate of Santa María del Alcázar.

In 1476, the fortress was demolished on the orders of the Catholic Monarchs so that it would no longer be used as a defence during the struggles within the nobility. At that time, there was a confrontation between the Carvajales families, who were more predominant in Úbeda, and the Benavides, who were dominant in Baeza. Nowadays, only ruins remain and some of the walls have been torn down. The southern front of the wall, adjacent to the fortress, has also disappeared (

Eslava Galán 1999, pp. 342–50).

As a result of this destruction, the hill gradually lost settlers, to the point of being almost uninhabited in the 18th century and the collegiate church was transferred to the parish of San Andrés (

Rodríguez Molina 1985).

Ximena Jurado drew this sketch in the context of the crisis of the 17th century, which had a particular impact on Baeza, preventing the consolidation of institutions as represented by the cathedral chapter or the university. In addition, many of the city’s fortified structures were already in ruins or had disappeared, which is why he would have formulated a graphic hypothesis about the configuration of its defences at the time of the conquest in 1227, or once Christian rule over the city was established, protecting itself against the Nasrids.

2.1.5. Castle of Baños de la Encina (Figure 7)

Profusely drawn on the following page (fol. 135), it is also larger than most of the folios in

Ms. 1180 B.N. It contains a representation of one of the best preserved fortresses from al-Andalus. It is labelled “Alcazar de Baños” (

Mozas Moreno 2018, pp. 340–41) and is accompanied by a rubric. The detailed drawing is framed in a simple rectangle and contains the cardinal orientations “septentrion” (north), “medio día” (south), occidente (west), and “oriente” (east) including only the word “norte” (north) arranged vertically, in a different font and darker ink.

Figure 7.

Sketch of the castle (Alcázar) of Baños de la Encina drawn by Martín Ximena Jurado. Ms. 1180 B.N., fol. 135.

Figure 7.

Sketch of the castle (Alcázar) of Baños de la Encina drawn by Martín Ximena Jurado. Ms. 1180 B.N., fol. 135.

The interior of the enclosure includes a long handwritten description:

‘The ground plan of the Castle (“Alcázar”) de Baños, which is six leagues from Baeza to the north, is almost 250 paces in circumference, and has as many towers and in such a distance it preserves as drawn here. It is situated in the Sierra Morena to the south of it, on the summit of a very high and curly hill, and today it has no population or houses within it. It is surrounded by population on all sides, if not on the west. And to enter this fortress there is only a small gate between two towers on the south side, and to enter from the fortress to the castle there is another small gate behind the round tower that divides it from the castle. All the walls and towers are made of rammed earth, except for the keep, which is made of stone’.

Some lines of this text are interrupted when they reach a box containing a perspective drawing of a cylindrical curbstone, above which is labelled “aljibe” (water cistern).

The hill on which the fortress of Burgalimar (from Arabic Burŷ al-ḥammām, Castle of the Baths) stands is at an altitude of 429 m above sea level, from which one can see a vast expanse of land as far as the surrounding mountain ranges. It is located in the extreme south-west of the municipality of Baños de la Encina (Holm Oak Baths).

This fortification was conquered in 1147 by Alfonso VII before passing back to Almohad power in 1157. In 1189, it was taken by the troops of Alfonso VIII of Castile and Alfonso IX of León to be recovered again by the North Africans in 1212 on their way to the Battle of Navas de Tolosa. Despite its defeat in that confrontation, it remained in their hands until it was definitively conquered by Ferdinand III of Castile in 1225 (

Eslava Galán 1999, pp. 357–58).

The castle adapts to the relief of the hill on which it stands, with an irregular ground plan in the shape of a seven-sided parallelepiped. Along its walls are 14 square towers (Ximena Jurado drew 15) with a reduced ground plan and the keep, popularly known in Spanish as the Almena Gorda, has a trapezoidal ground plan and a curved north-east front, although Ximena Jurado drew it in a cylindrical shape.

The gateway has direct access, flanked by two towers, without the defensive bend that characterises Andalusi fortresses. Ximena Jurado drew another in front of it in the antemurium with a similar layout, without being unprofiled.

After the conquest, the Castilians added some elements: a keep with three barbicans on its outer façade, which came to replace the easternmost of the original towers, and an inner division, which came to enclose part of the fortress, with a circular keep that today appears to be severely crumbling, joined to the rest of the fortress by a wall of rammed earth. In Ximena Jurado’s depiction, it is crowned with parallelepiped battlements.

The castle of Baños also had an ante-wall or barrier surrounding the ramparts, well represented in Ximena Jurado’s drawing. Today, it has almost completely disappeared except for the vestiges that may be preserved inside the houses on Calle de Santa María.

All of the rammed earth work including the walls with its 14 towers with traces of masonry and arrow slits was erected during the Andalusi period, while the masonry part was constructed after the Christian conquest in 1147, being limited to the keep and the inner cylindrical tower. On the ground floor of the keep, the remains of the old Almohad tower can be seen.

The square towers have lost their internal division on the ground plan, although the access openings are at different heights. The lower ones are at the same level as the ground, while the upper ones are at the level of the parapet or walkway.

The entrance to the castle, on the southern flank, is formed by a horseshoe arch, sheltered under another arch of the same type, but slightly pointed. On the inside, there is another pointed arch with its abutment, flanked by two of the square towers.

The walls and towers of the fortress are topped by concrete merlons, erected during one of the restorations in the 1970s. The walls have caissons with heights ranging from 70 to 90 cm, with a predominance of 75 cm (

Muñoz-Cobo Rosales 2009, p. 62). They have a false break-up of mock ashlars measuring 0.80 × 2.05 m, with plaster lines of 10 cm. Their dating has been controversial, as, together with the castle of El Vacar in Cordoba, they have been used to justify the claim that this motif was a feature of the Caliphate period in the 10th century (

Ferrer Morales 1996, pp. 6–9;

Muñoz-Cobo Rosales 2009, pp. 57–106). It was thus argued that the only work of Almohad origin would be the rammed earth wall (

Cerezo Moreno and Eslava Galán 1989, p. 74). However, archaeological research has confirmed that the wall and towers containing the mock masonry were also erected at that time (

Moya García 2016). Despite the controversial attribution and provenance of an inscription from 967–968, made during the reign of the Umayyad Caliph al-Ḥakam II, decontextualised and transferred to the Spanish National Archaeological Museum in 1907, which has traditionally been linked to the construction of this fortress (

Canto García and Rodríguez Casanova 2006, pp. 57–66), the very construction techniques used in the rammed earth walls have led to the main workmanship of Burgalimar being ascribed to Almohad building (

Azuar Ruiz and Ferreira Fernandes 2014, p. 401).

2.1.6. Andújar (Figure 8)

Drawn in fol. 138, it is also larger than most of the folios in

Ms. 1180 B.N. It contains a sketch labelled ‘the city of Andújar’, and on the right side, again “Anduxar” vertically and in small letters (

Mozas Moreno 2018, p. 345).

Figure 8.

Sketch of Andújar drawn by Martín Ximena Jurado. Ms. 1180 B.N., fol. 138.

Figure 8.

Sketch of Andújar drawn by Martín Ximena Jurado. Ms. 1180 B.N., fol. 138.

In this case, the text was inserted in the upper right-hand corner, indicating: ‘Plan of the walls of the city of Andújar. It has 1060 paces. On the eastern front, 150 paces. On the northern, 240. On the western, 240. On the southern, 430. It is next to the Guadalquivir River on the northern bank. It has four very large octagonal towers at the four corners’. This text was written after indicating the cardinal points “septentrion”, “meridies”, “occidente”, and “oriente”; as the latter was covered by the text, it was rewritten in capitals with the letters following the line of the wall.

To the south of the walled city, where an ante-wall stood, runs the Guadalquivir River, which could be crossed. Ximena Jurado indicated ‘the bridge has a tower in the middle, and has 16 arches’, drawing this infrastructure with four arches and a tower between them.

It seems that the walled enclosure of Andújar was built in the Almohad period at the end of the 12th century or very early 13th century, according to a single plan, as it was a strategic town that controlled the passage to the Guadalquivir Valley. The citadel must have been built at the same time.

The perimeter of its walls was trapezoidal in shape. It had as many as 12 gates, but initially, there were no more than seven. The fortification as a whole comprised 48 towers, four more distant octagonal towers facing the river, an albarrana tower, an ante-wall, an embankment, and moats. On the side that faced the river, it had a fortress that had completely disappeared in the 17th century. It served to reinforce the walls of the town and controlled the access to the town from the north.

Part of this fence was covered with ashlar masonry in the 15th century. When the city outgrew the enclosure inside the walls, streets were built along the walls, and houses began to be built attached to them.

The Andújar enclosure survived until well into the 19th century, but today, only a meagre 5% of the original perimeter, which was about 1470 m, has been preserved (

Eslava Galán 1999, pp. 70–79).

Fol. 152 of

Ms. 1180 B.N. was intended to contain information on this municipality, but the folio is empty. However, Ximena Jurado devoted up to nine personalised drawings to the city in other books, from urban views and planimetries to the representation of detailed areas of the town, where excavations had been carried out in search of relics (

Ximena Jurado 1643, pp. 3–8).

Ximena Jurado was sent to Arjona in 1642 to collaborate in the excavations of relics. As a result of this work, around this year and in the following one, he published two books in which the drawings were included. Perhaps for this reason, fol. 152 of the Ms. 1180 B.N., where “Arjona” is labelled, appears empty, which is also the case for the nearby town of Arjonilla (fol. 151). It does include abundant epigraphic, numismatic, and heraldic documentation between fols. 48 and 56, assigning it up to fol. 59 with blank pages on which it was planned to introduce more inscriptions. This is the chapter entitled “en la villa de Arjona, y su Arziprestadgo”, where he also includes antiquities located in Arjonilla, Cotrufes, Hardon, and Herrerías. Among them, he drew a ‘column of alabaster, which is inside the castle of Arjona in the corner of a tower, which makes an arch to the keep’ (fol. 48), another ‘at the entrance of the Alcázar in the foundation of the Torre del Ariete’ (fol. 49), and two pedestals that ‘are inside a cistern, which seems to be the work of the Moors. The vault of the cistern rests on them’ (fol. 48v). This water tank is located next to the Church of Santa María del Alcázar, built over the Andalusi mosque, which in turn was built over a primitive late Roman-Visigothic church, constructed over the temple erected in honour of Caesar Augustus. This cistern was probably built in the Almohad period. It is divided into three naves covered with a brick vault, which rest on the pedestals that supported the statues in the Roman temple, one of which is dated to 21 BC.

The most interesting part of his history of the town of Arjona is the one that deals with the period from the 13th century to 1643, with the different chronicles and a series of documents such as privileges and grants awarded to the Council of Arjona (

Ximena Jurado 1654). In this book, he structures the study along a chronological line with various news items, with the aim of highlighting the importance of Arjona through the figure of its Christian martyrs, Saint Bonoso and Saint Maximiano, in order to glorify them as agreed at the Council of Trent. Both brothers were natives of Iliturgi, near present-day Mengíbar. They were officers in the Roman army who refused to abandon their faith, for which they were martyred in 308. This news would have been collected in the ‘Acts of Martyrdom in Urgavo de la Betica’ (Arjona), written around 312 by Saint Felix, Bishop of Guadix, who presided over the Council of Elvira in Granada. They were later sent to Toledo and collected by Flavio Lucio Dextro in the 5th century in his

Cronicón de Omnimoda Historia or

Historia Universal, fragments of which were printed in Saragossa in 1619 by Fray Juan de Calderón. They were illustrated in 1627 with notes and commentaries by Licenciado Rodrigo Caro and Fray Francisco de Bivar. This text may have favoured the climate for promoting the search for skeletal remains in 1629 to which the desired category of religious relics could be attributed.

In his history of the town of Arjona, Ximena Jurado provided an extensive description of the town of Arjona (

Ximena Jurado 1643, pp. 3–8) to go with his drawings:

‘This place is noble and illustrious for its great antiquity, the greatness of its population, the defence of its walls, […] chosen as a court by the Moors, the head of a kingdom at one time, the origin and beginning of the House and Kingdom of the Arab Kings of Granada […].

[…] it is all surrounded by walls and towers, once strong, all made of lime and stone, and now, for the most part, ruined and chipped. The shape of the town is like that of a boat. In the walls there are 24 towers and four gates.

All of which are fortified, each one with two stone towers, very strong with such an art, that one of these towers covers the door in such a way that from the outside it cannot be seen, and thus it is necessary to enter through it with a certain roundabout way, with whose turns they were very safe from the war machines with which the opponents intended to break them when they attacked this town.

The Alcázar is situated on the top of the hill, on the south side; its shape is thus round, because it has only two corners at the two ends of the southern wall, which is somewhat straight.

This Alcázar is surrounded on all sides by walls and ante-walls, with many strong towers along the circumference of the wall; it has twenty towers and in this respect in the ante-wall; it has three gates […].

At the eastern gate of the Alcázar is the castle with ten towers […]. It had a moat around this castle for its better defence; its gates were two, both small; one on the inside of the Alcázar, to go out of the castle to the same Alcázar and main square that is located in front of the gate, which looks to the north, and another to go out of the same castle to the town. The circumference of the Alcázar is 1633 rods and that of the castle 267.’

In the surroundings of Arjona, a human presence can be attested to since the Palaeolithic Age by the findings of pieces of stone and human remains, given the possibilities of exploitation presented by the countryside of Jaén. In the Plaza de Santa María in Arjona is located a plateau that corresponds to the first village centre and the highest social prestige of the town from at least the Bronze Age (2000–700 BC), as attested to by the possible discovery of an Argaric burial place in 1628, which was incorrectly thought to be the relics of Christian martyrs (

Castro Latorre and Eslava Galán 2022, pp. 86–87, 116–17, 203–4). In the Iberian period, the village was an important

oppidum, which, together with its neighbours Iliturgi, Isturgi, and Obulco, received privileged status from Caesar after the Battle of Muda. It became one of the first settlements to achieve full Roman citizenship with the title of Municipium Albium Urgabonense.

In the Andalusi period, it became the citadel of the city, with a wall, ante-wall, and fortress. The Andalusian citadel integrated as part of its ante-wall has some stretches of the Iberian wall from the 3rd century BC, with its characteristic sloping form. As a whole, Arjona had one of the most complete sets of urban fortifications on the Iberian Peninsula with three lines of walls, twenty-two towers, two watchtowers, a fortress, a castle, and a cistern. It had an outer walled enclosure that embraced the town, the citadel with the fortress at one end as well as the administrative and commercial quarter with its own walled enclosure and its ante-wall.

In this period, it was called Qal‘at Arŷūna, where the Banū Bāhilah settled after the conquest. The city took part in the final battles of the Emirate of Cordoba (9th century), at which time its walls were reinforced.

Tradition has it that on 19 July 1195, on the day of the Battle of Alarcos, the last great Muslim victory on the peninsula, Muḥammad b. Yūsuf b. Naṣr, commonly known as Ibn al-Aḥmar, was born in Arjona. He was to become the founder of the Nasrid Dynasty (Muḥammad I) and of the last Islamic kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula after settling in Granada, which was more protected and further away from the border, following the Christian conquest of the Guadalquivir Valley after the Battle of Navas de Tolosa (1212). He managed to establish himself as a ruler by using the prestige acquired through his exploits during border battles and the support of the members of his family, the Banū Naṣr, or Banū l-Aḥmar, and of his relatives the Banū Ašqīlūla.

Arjona fell into the hands of Ferdinand III of Castile thanks to a pact with Ibn al-Aḥmar in the spring of 1244, in which houses and inheritance were given to his knights. In 1433, the castle ended up belonging to the Order of Calatrava, while the rest of the citadel belonged to the town council. In the middle of that century, the defences of Arjona underwent successive repairs due to its involvement in the civil war between Juan II and the Infante Don Enrique, who would end up being enthroned as Enrique IV of Castile.

Arjona contains remains of different chronologies and building traditions. Some rests of the primitive Iberian oppidum are preserved at Plaza del Mercado, which was extended in Roman times to an enclosure that embraced part of the foothills. After the Muslim conquest, from the year 888 onwards, an intense remodelling would have taken place. The builders of the fortress reused the remains of the old walls and added towers or raised their structures. In 1132, Arjona was considered a strong and safe place, which enabled it to resist subsequent sieges in 1244, 1277, 1316, and 1367.

The work published in 1634 by Ximena Jurado shows that the outer wall was ruined and chipped, that a large part of the keep had collapsed, and that at several places, the only remains left of the Alcázar wall were its foundations. This deterioration escalated from 1639 onwards due to the plundering of its building materials (

Eslava Galán 1986, pp. 25–91;

1999, pp. 79–93).

The drawings that Ximena Jurado published in his works show the process of graphic production that he followed, from the taking of quick notes and sketches in Ms. 1180 B.N., to the further elaboration of some of the folios that he inserted folded in that manuscript, to the final presentation of this graphic material in a book.

In the case of Arjona, he made both territorial and urban drawings, which were more detailed for the places where excavations were being carried out.

He drew a territorial map (

Ximena Jurado 1643, p. 7) quite similar in layout to the ‘Description of the kingdom and bishopric of Jaén’ (

Figure 1), and depicted with higher detail the north-western quarter of the previous map, in the area where Arjona is located (

Figure 9). He also drew an urban view of “La Villa de Arjona” (

Ximena Jurado 1643, p. 8). In this drawing, there are also two coats of arms, the details of which he had already sketched in

Ms. 1180 B.N. This drawing is similar in style to that of the town of Martos, where he resolves this type of view more correctly; with the walls, towers, and gates in pseudo-conical aerial view (a front elevation view with superimposition of planes of depth, although without applying perspectival criteria), and with the western wall erroneously depicted. The walls are not cut into ashlar, but their lines tend to be horizontal. In the interior, the houses are depicted in a very motley manner, with no clear distinction between streets or public spaces. To this end, simple and disproportionate iconic drawings of houses are introduced, with their undifferentiated elevation view, with two windows, a door, and a grated gable roof. This filling resource makes it difficult to identify relevant buildings, although the three churches can be seen by the bell tower crowned by a cross; however, they are not larger than the houses, nor are they labelled. Neighbourhoods outside the walls can also be seen with groups of houses without boundaries, next to the hermitages, recognisable by the belfry on the roof. The citadel is fenced in, with its ante-wall visible as well as the castle and the area of the San Nicolás sanctuary, which is marked with a cross. The mountainous relief he drew towards the south shows that the town is high up and overlooks a hillside.

The latter, in the form of pseudo-axonometric views with abundant explanatory texts, more faithfully show the real state in which the fortifications of Arjona were found.

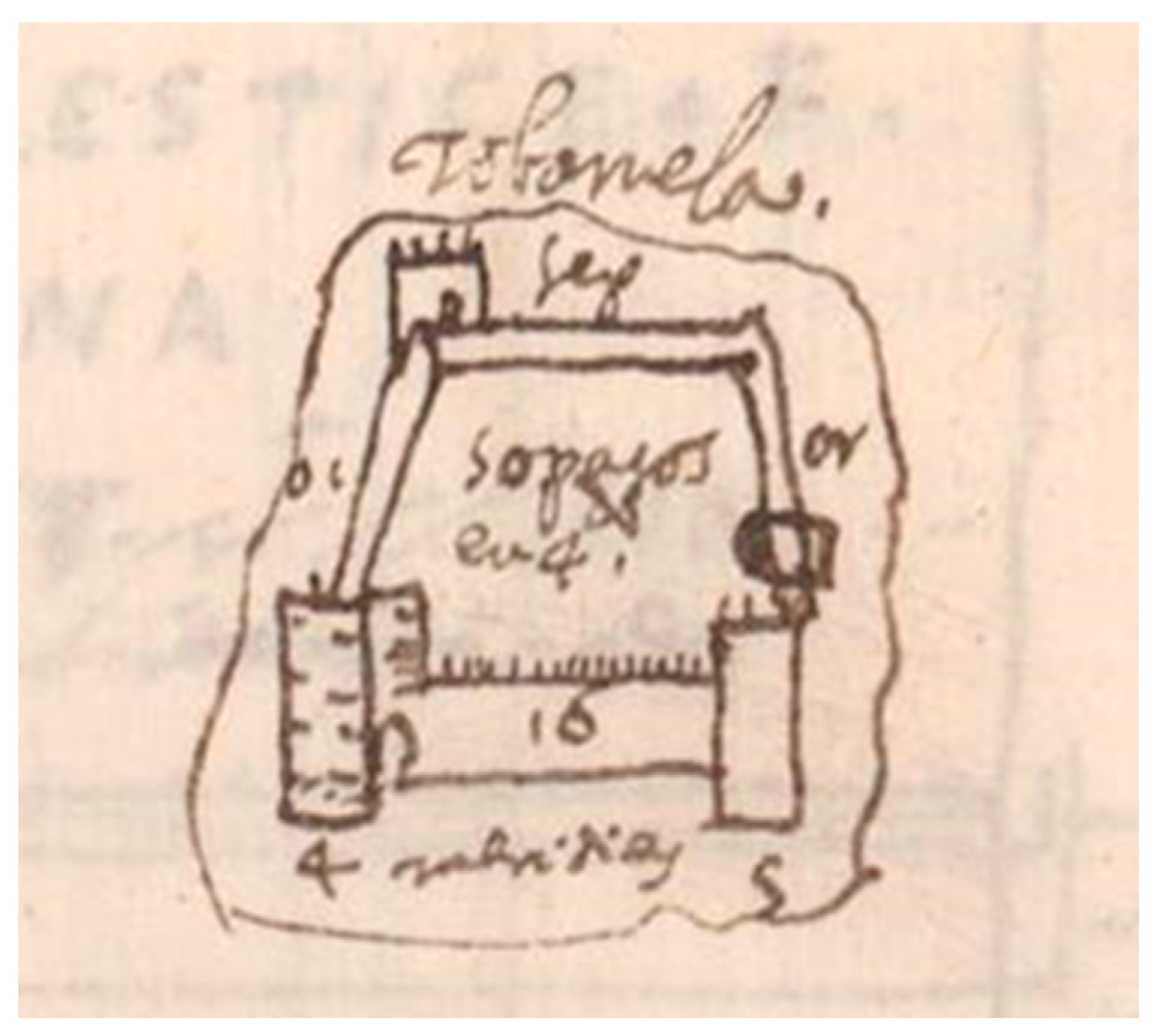

The first plan is entitled ‘Description of the town of Arjona’ (

Figure 10). It shows a plan view of the circuit of the city walls, with the walls, towers, and gates folded inwards and hierarchised according to their size as well as the enclosure of the citadel and castle in greater detail, also indicating the layout of the outer walls with their profusion of breaks and outlines (

Ximena Jurado 1642, plan 1). The most important religious and civil buildings are not indicated. He also referred to the ‘Sanctuary where Saints Bonoso and Maximian and many other Christian Saints suffered martyrdom in the Persecutions that the Roman Emperors raised against the Church’.

The second plan follows the same drawing criteria, zooming in with greater detail on the area next to the citadel and the castle where the excavations had been carried out (

Figure 11). Using a system of icons, the positions of the objects found in the ‘moat of the castle’ and in the sanctuary of San Nicolás are indicated. In this plan, he introduced a generalised quartering of the masonry of the towers and walls, with the representation of certain details such as some of the battlements (

Ximena Jurado 1642, plan 2). In addition to his generalised criterion of marking the four cardinal points with words instead of a compass rose, two simple graphic scales were introduced.

The third drawing has a more elaborate graphic scale and a compass (

Ximena Jurado 1642, plan 3), which represents in cavalier perspective the area of the findings in the sanctuary of San Nicolás (

Figure 12), with references to different towers and other fortifications in this area.

The fourth drawing is a ‘description of the Sanctuary’ (

Ximena Jurado 1642, plan 4) with a pseudo-axonometric view, indicating the state of conservation of the towers, gates, and walls with an exploded view of the walls (

Figure 13). Thus, it shows where the ‘bossed or diamond-shaped’ ashlars were found, which he attributed to the ancient period. In addition to the labels and interior texts, he introduced a legend with Latin letters in capital letters.

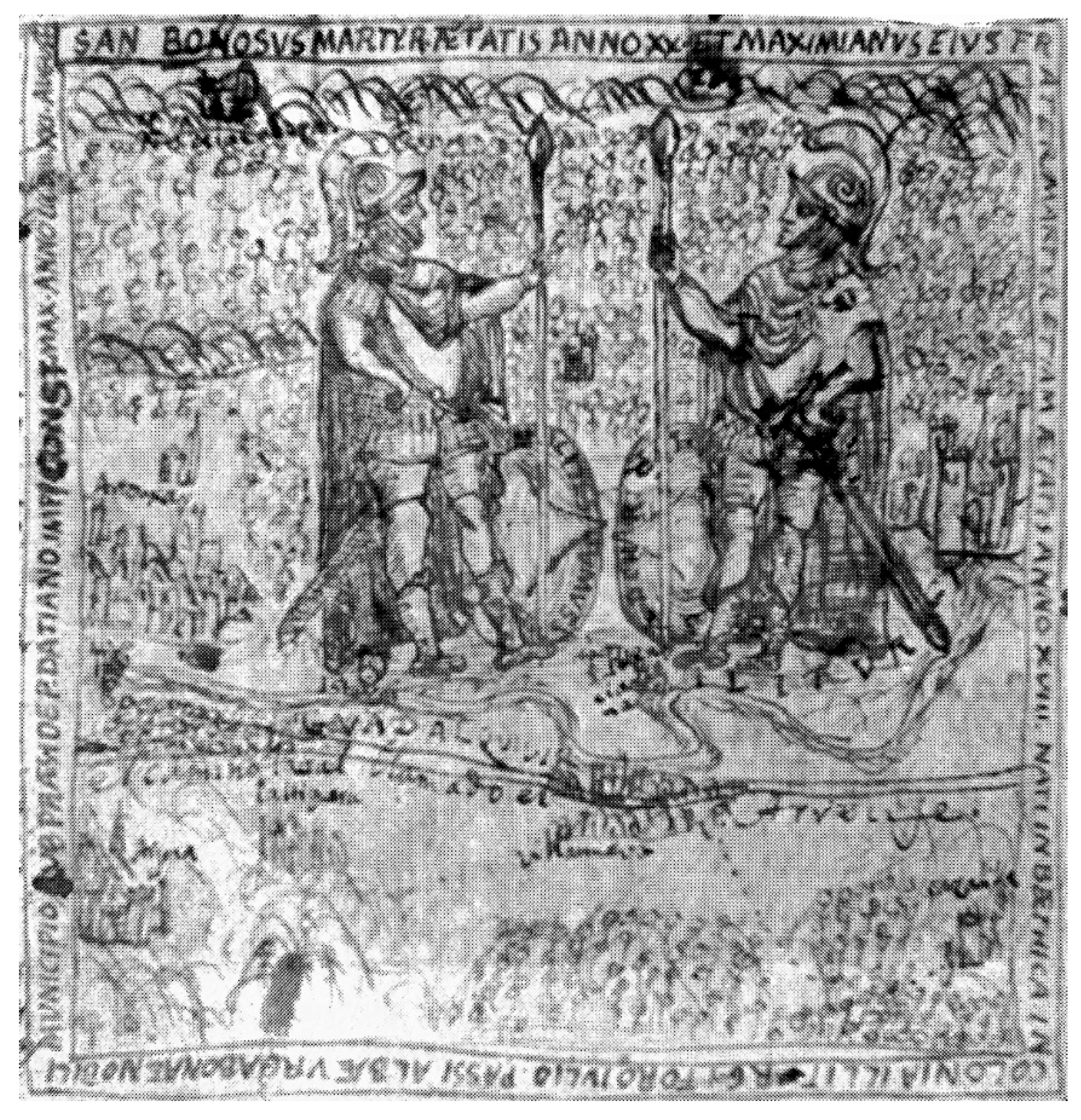

In chapter 29 of his history of the town of Arjona, he drew several idealised scenes of the martyrdom of the Roman soldiers Bonoso and Maximianus in the town of Arjona (

Ximena Jurado 1643, pp. 116–18). He depicted three graphic sequences in the manner of comic vignettes. In these images, he also drew the walls, towers, and gates of the Alcázar following a similar criteria of representation to the previous ones (

Figure 15). He also drew a frontal territorial view of the section of the Guadalquivir Valley as it passed through the eastern part of the Jaén countryside (

Figure 16), the place where he came from, placing his home town—Villanueva—at the centre with the royal road called “el Arrecife” (from Arabic

al-raṣīf) going through it. The town of Arjona was placed in the lower left-hand corner of this drawing (

Ximena Jurado 1643, p. 121).