Abstract

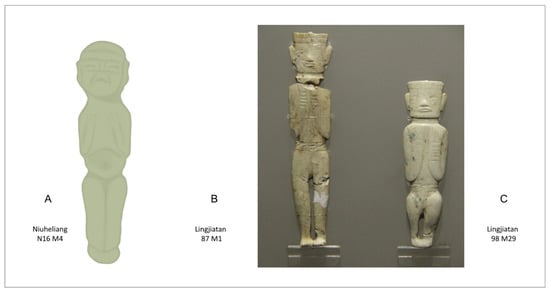

Jade artifacts produced in prehistoric China continue to generate extensive scholarly interest. In the absence of textual data, inferring how works functioned in Jade Age communities remains challenging. This paper focuses on Hongshan 红山 culture (4500–3000 BCE) jades, a distinctively styled corpus primarily recovered from late fourth millennium BCE graves in northeastern China. Recent finds within and beyond the Hongshan core zone have enriched the jade inventory and expanded the known scope of its stylistic variations. The analysis sheds light on enigmatic types, reveals the complex representational nature of this corpus, and clarifies the mimetic intentions that resulted in the soft rounded forms characteristic of the style. Most objects examined were unearthed at Hongshan ceremonial centers and have sound excavation pedigrees. Their study relies on contextual archaeological data and comparative visual analysis and draws on the broader Hongshan material world. Further considerations include environment, funerary practices, materiality, cognition, and human anatomy. Ultimately, the paper uncovers new paradigms of figural representation that should open fresh investigative avenues for specialists of early China. Preliminary evaluation of jades unearthed further south at Lingjiatan 凌家滩 and Liangzhu 良渚 sites suggests that some late Neolithic societies adopted Hongshan practices. Current evidence hints at members of prehistoric communities attempting, through jade works, to rationalize their physical circumstances and assert their social power by symbolically fusing with elements of their environments.

1. Introduction

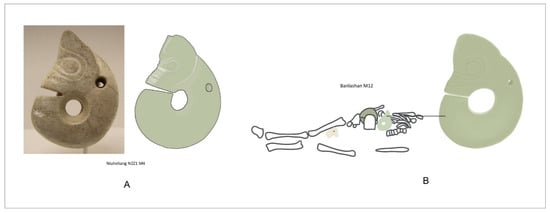

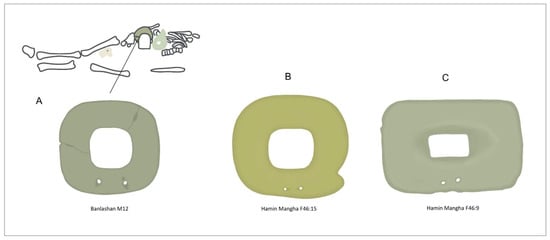

Prior to turning molten alloys into sumptuous bronze vessels that today’s visitors admire in museum galleries, inhabitants of ancient China had spent millennia transforming other substances into exquisite artifacts. During the Neolithic period, jade became a matrix of choice to craft an array of objects that archaeologists generally discover entombed with the deceased. Excavations have revealed a dramatic increase in the production of jade objects over the course of the Neolithic period, so much so that early China specialists classify the last phase as the Jade Age (3500–2000 BCE) (; ; ; ). Archaeological work conducted in northeast China continues to yield prehistoric jades, at once reinforcing well-established cultural corpuses and delighting specialists. This was the case in the last decade with finds from the Banlashan 半拉山 cemetery, a site located 13 km from Chaoyang City in Liaoning Province, and the Hamin Mangha 哈民忙哈 settlement in Horqin Left Banner, Inner Mongolia (, ; ; ). Excavations at Hamin Mangha led to the sensational discovery of burned houses filled with piled human remains, signs of a hasty site abandonment attributed to a plague outbreak approximately 5000 years ago (). The jades recovered at the site presented specialists with a novel corpus of forms reminiscent of well-known types produced in the Hongshan 红山 cultural sphere. Banlashan, securely located further south within the Hongshan culture (4500–3000 BCE) core zone in the Daling 大凌 River valley, generated better-established jade types from more conventional funerary and ceremonial contexts.1 Architectural features uncovered revealed a burial ground used over three centuries in the last part of the fourth millennium BCE. Alongside its jades, this cairn cemetery generated bottomless clay cylinders, anthropomorphic sculptures, an enclosed, stone-faced, and elevated platform area, and sacrificial pits, all consistent with material traces unearthed at other late Hongshan (3500–3000 BCE) jade-yielding ceremonial centers at Caomaoshan 草帽山 in Aohan Banner of Inner Mongolia (), Hutougou 胡头沟 in Fuxin 阜新 county (), Dongshanzui 东山嘴 in Kazuo 喀左 county (), and the more extensive Niuheliang 牛河梁 complex in Lingyuan 凌源 and Jianping 建平 counties2 (; ). Ceremonial centers functioned as magnets for communities that sustained their livelihood through hunting, gathering, and agriculture, and that lived in small villages made of semi-subterranean houses scattered throughout an area spanning northeastern Hebei province, southeastern Inner Mongolia, and western Liaoning province in northeast China. Scholars suppose that the centers, manned by ritual specialists, served surrounding populations, and helped sustain broader socio-political cohesion (; ; ). The ritual sites generally also functioned as resting places for select community members. Archaeologists often find the tombs near and inside large communal stone cairns associated with elevated platforms. They occasionally unearth jades from sacrificial pits and ritual platforms, but the majority come from these graves, solely furnished with jade burial goods. Scholars have posited that the tomb occupants were members of the Hongshan elite.3

Well known to scholars of early China, Hongshan jades have entered the visual field and captivated the interest of a broader contemporary public. Museum collections and auctions offer opportunities for modern viewers to see the often-enigmatic shapes that prehistoric people gave to these objects. Introductory surveys and monographs on the arts, archaeology, and emergence of civilization in China often feature jades from Hongshan tombs. These artifacts remain significant in quests to understand a remarkable culture, which experts of the prehistoric northeast consider as “the first clear steps toward complex social, political, and economic organization in this part of the world” (). Scholarly investigations, however, have largely focused on the ideology of Hongshan communities and highlighted its link to historical Han China (). Hongshan jades and the symbolism possibly embodied in their shapes are perceived as a window onto past values and beliefs. Regularly, discussions on these 5000-year-old artifacts imply that some Chinese cultural aspects date back to Hongshan times.4

The present analysis intervenes in a rich scholastic tradition, sustained in the United States with the exhaustive work of Elizabeth Childs-Johnson.5 The unearthing of Hongshan jades from tombs yielding little stratigraphic data has encouraged typological, taxonomic, and spatial distribution analyses to infer their relative dating and thus assist in the periodization of graves (; ). These objects further stimulated inferences about the status and role of tomb occupants, the power they held in society, their command of ritual activities, and the control they exerted over the valued substance. To that effect, functional classifications often assign some jades to the category of ritual objects (; ). Material provenance studies suggest that Hongshan communities relied primarily on jade from Xiuyan 岫岩in Liaoning Province, but also point at more distant origins such as the Lake Baikal area in Russia (). Typologically diverse, Hongshan jades include forms used for body grooming and adornment. A few graves notably generated three-holed implements believed to have functioned as combs. Excavators sometimes unearth bracelets, the most common jade type, wrapped around the forearms of long-deceased tomb occupants, leaving no doubt about function. Scholars surmise that small apertures produced on other types facilitated attachment to garments and suspension from bodies. In the quest to understand the values, beliefs, and religious activities that sustained prehistoric Hongshan communities, substantial attention has turned to the symbolism of these artifacts. The recent essays of Cui Yanqin 崔岩勤 and Zhang Chi 张弛 exemplify recurrent links between zoomorphic jades and putative religious beliefs (; ). Some jade forms have served to support the idea that significant beliefs date back to pre-Bronze Age times and to validate the idea that Hongshan communities generated incipient forms of the Chinese cultural tradition ().6 Examples include the emergence of the dragon (), cosmology and related concepts ranging from yin 阴 and yang 阳 to heaven and constellations as well as shamanism, another interpretative paradigm whose impact endures in the academic discourse (; ; ; ; ; ). Li Xinwei 李新伟 recently integrated the concepts of cosmology and shamanism and suggested that Hongshan jades helped the elite display its control of sacred cosmology during public rites ().7 However, evidence still does not support putative links between Hongshan jades, shamanism, and cosmology. Nor can it prove that Hongshan practices and ideology relate to later Chinese rituals and cosmological precepts ().

While used to support hypotheses regarding social, political, or religious processes as well as putative cosmological interests or broader belief systems, Hongshan jades have puzzled specialists. Their growing repertoire with secure archaeological contexts offers exciting avenues for fresh investigation of what some regard as the prehistoric “culture that turned jade-working into a high art”.8 This study will endorse the proposition that some jades worn in life may have functioned as amulets (). However, the analysis does not aim to uncover how the jades functioned in social, political, or religious contexts. Instead, it considers the topic through the double prism of style and how jade objects represented in the Hongshan cultural sphere. Therefore, in lieu of a teleological approach, our focus recenters on the circumstances by which jade forms came into being. Some of the questions this study attempts to answer include: Where does the distinctive style of Hongshan jades come from? How might analyzing their style help us better understand what some enigmatic types represent? How can we explain the occurrence of different styles within the corpus of some Hongshan jade types? Southern jade-working communities at Lingjiatan 凌家滩 in modern Anhui province adopted some Hongshan jade types but reproduced them through their own stylistic expression (). Did communities closer to the Hongshan cultural sphere adopt the style of Hongshan jades?

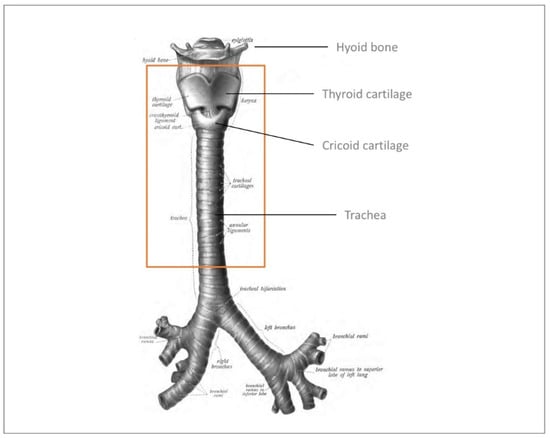

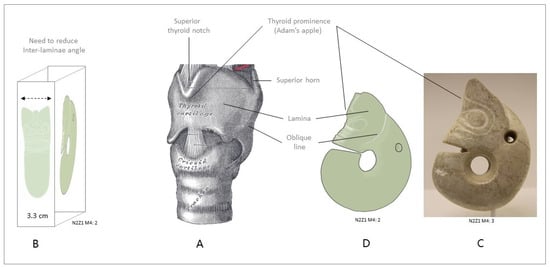

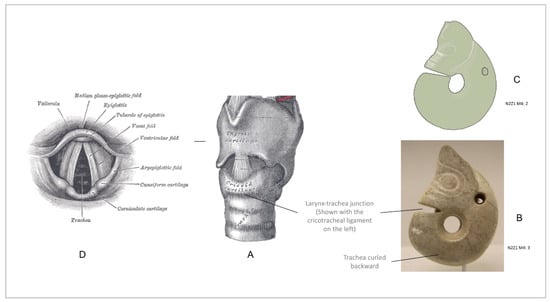

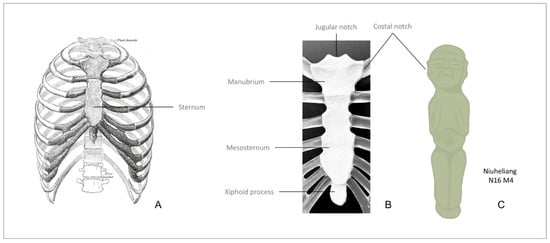

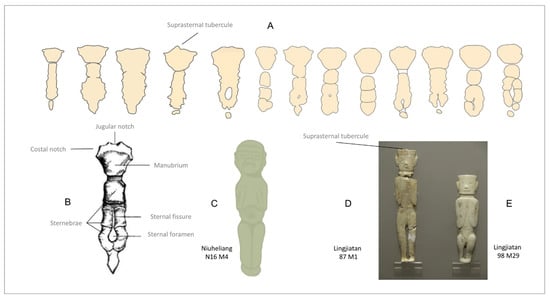

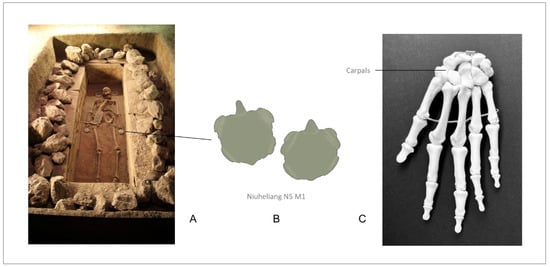

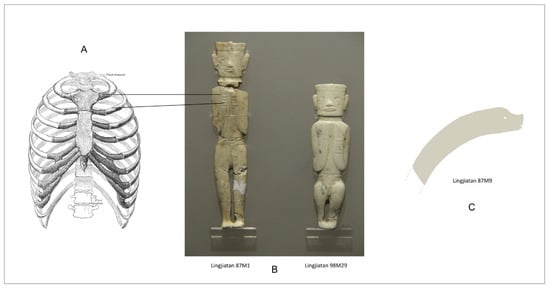

The often-enigmatic Hongshan jades have puzzled the scholarly world. This study leads us to rethink what these artifacts represent through the prism of how they represented from the standpoint of their original makers and users. A first step will entail preparing a foundation to reconsider these Jade Age objects. To that end, we refocus attention on the peculiar physical characteristics that we associate with the Hongshan jade style, on the visual cultural landscape in which they appeared, and on enduring interests in material-representation synergies in Neolithic northeastern China. In the second step, the examination exposes how the already remarkable corpus of Hongshan figural works is richer than we assumed. Indeed, as detailed comparative analyses reveal, numerous Hongshan jades represent human bones and cartilage. Individual analyses will explore how significant jade types correspond to specific human skeletal constituents. They also illustrate how some jades featuring zoomorphic aspects resulted from a two-step process. First, while looking at human skeletal constituents, sentient beings (likely jade-makers) projected zoomorphic mental images on human osseus configurations. This cognitive process, known as pareidolia, has led to the emergence of figural imagery in prehistoric communities throughout the world, including China (). Second, jade-makers embodied these zoomorphic mental images when they represented human bones and cartilage. Our examination suggests that jade-makers, like the craftsmen who produced clay figural works for ceremonial centers, were interested in naturalism.9 Unlike the image-makers who worked with clay, however, jade craftsmen had less medium to spare. At any given time, their access to raw jade could have been inadequate, or the size of mineral blocks would have limited what they could produce. They faced other obstacles. The subtractive processes they used to shape their medium into desired forms required that they conceptualize a form before extracting it from a raw mineral block. In their quest to naturalistically represent human skeletal constituents, they faced two additional challenges: the often large three-dimensionality of their bony models as well as their complex morphology. To remediate these obstacles, Hongshan jade-makers developed strategies. For savvy use of material, they employed jade slabs to represent some large skeletal body parts. In other instances, they engaged in a more synecdochical approach, and simply represented one bone segment to stand for an entire bone. They abstracted complex osseo-morphs into elemental shapes. They devised conventions to render each body part in jade. Their works nevertheless evidence formal variations resulting from enhanced abstraction, more limited skills, time constraints, or personal whim. Regardless of the shape they gave to the renderings, jade-makers made sure to confer an organic quality to their works. These physical characteristics are precisely what modern viewers associate with the style of Hongshan jades. Ultimately, the Hongshan style resulted from mimetic interests and the solutions that jade-makers devised to enhance the naturalism of their necessarily abstracted skeletal representations. In the third step, our study expands beyond the Hongshan world. First, diachronically, we consider how the Hongshan jade style may have perdured in northeast China following that culture’s demise. Second, synchronically, we investigate the influence that Hongshan jades and associated representational interests had on southeastern jade-producing cultures. Preliminary evaluation of jades unearthed at Lingjiatan in Anhui province and Liangzhu 良渚 culture (3300–2300 BCE) sites in the Yangzi River delta suggest that these jade-working cultures gave selective reception to Hongshan practices. Lingjiatan and Liangzhu jade-makers appear to have embraced two Hongshan habits: the reproduction of human skeletal constituents with jade and the embodiment of pareidolia-induced figural imagery into jade forms. Furthermore, the style of Lingjiatan somatic representations identified in this study appears to derive from three factors: local aesthetic sensibilities, variations in human osteo-morphology, and likely efficiency requirements.

Methodologically, our exploration relies mostly on objects unearthed during archaeological excavations conducted in the Hongshan world, at Lingjiatan and at Liangzhu sites. Their study draws on contextual archaeological data, comparative visual analysis, the broader Hongshan material world, environmental factors, funerary practices, materiality, cognition, and human anatomy. For ethical purposes, the author photographed full-sized polyvinyl chloride bone models cast from original skeletons in China.

2. The Hongshan Jade Style

Hongshan jade-makers worked in communities whose ceremonial centers offered a rich visual experience. When mourners placed jades inside graves near or embedded in large cairns, the surrounding man-made environments were rich in textures, shapes, and colors. For example, ceremonial centers at Banlashan and Caomaoshan presented visitors not only with funerary cairns but also a display of colorful lithics used to erect or line enclosures and elevated altar platforms. Rusticated and wedge-shaped blocks of yellow sandstone complemented gray volcanic rocks (rhyolite) and white limestone at Banlashan. At Caomaoshan, red volcanic rocks (tuff) alternating with white ashlar blocks and yellow sandstone offered another visual experience. Beyond these rock features, conical ceramic turrets and multiple large bottomless red clay cylinders presented viewers with surfaces textured or painted in black, red, and white.10 During funerary processes and sacrificial offerings, greenish to whitish jades would have stood out as comparatively monochromatic if not pale.

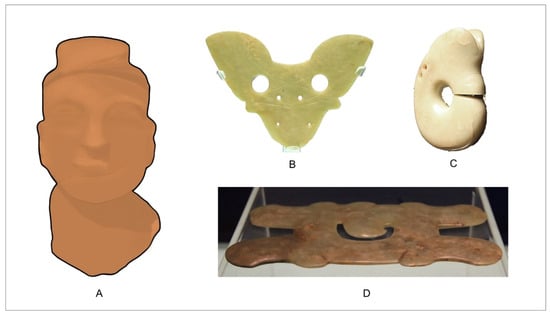

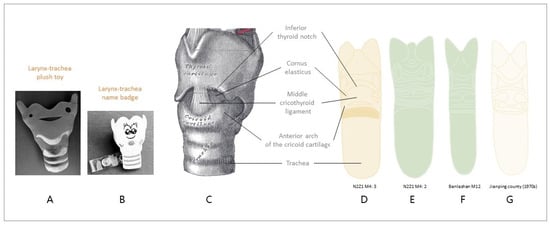

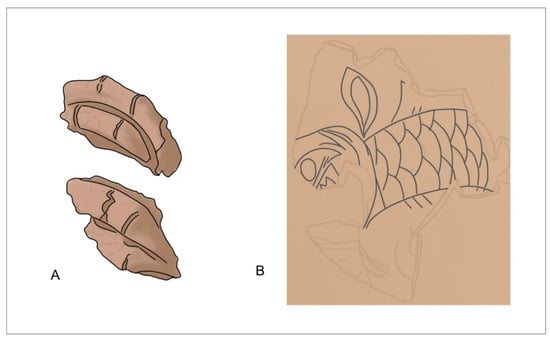

Sculptures done in stone or clay complemented the already stimulating sights.11 Large zoomorphic stone arrangements occupied platforms at Caomaoshan.12 Archaeologists uncovered better-known animal-shaped renderings at the so-called Goddess Temple 女神庙 further south at Niuheliang. Built between the last phases of burials at this grand ceremonial complex, the semi-subterranean feature yielded an array of heretofore unseen sculptural works. The archaeological team did not complete the excavation, but remains found thus far have revealed striking unbaked clay renderings, including an animal lower jaw and a feathered body. Scholars surmise that the high-relief anthropomorphic body parts found inside the structure belonged to larger-than-life or life-size renditions of complete bodies. All the remains found in the two temple chambers evidence a strong interest in mimicking life-like forms. Over the years, other discoveries within the Hongshan cultural sphere have generated a robust corpus of anthropomorphic sculptures. These works confirm a predilection for forms and form relationships with counterparts in the physical world. This representational style, known as naturalism, is exemplified here by a red tuff head found at Caomaoshan (Figure 1A). The large size and naturalistic clay and stone renderings of the Hongshan world remain unparalleled in the known corpus of figural imagery from fourth millennium BCE China. Current data clearly indicate that core zone jade-makers intervened in a rich representational tradition marked by a copious display, and perhaps manipulation, of anthropomorphic, and to a lesser extent zoomorphic, representations at ceremonial centers. We still do not know whether the same people made clay, stone, and jade artifacts and renderings. Nevertheless, we can assume that stone-work, architectural features, artifacts, and sculptures in the visual environment affected the aesthetic sensibilities of jade-users and viewers. So, one might ask: If Hongshan people favored works done in a naturalistic representational style for their ceremonial centers, what did they think of the style used by jade-makers to craft objects deposited in graves? If Hongshan communities wanted and appreciated carefully modeled, detailed, and life-like renderings, how could jade-makers get away with their barely legible sculptures of creatures? (Figure 1B,C). Likewise, if their contemporaries favored three-dimensional or high-relief sculptures, how did craftsmen render their flat jade plaques appealing? (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

(A) Anthropomorphic sculpture (tuff) found at Caomaoshan (Source: Léa Bass (LB) and Sandrine Larrivé-Bass (SLB) on Procreate); (B) Jade plaque from tomb N2Z1 M21 at Niuheliang; (C) Jade pig-dragon at the Capital Museum, Beijing, (Source: Courtesy of Gary Todd, Ph.D.); and (D) Jade plaque at the Liaoning Museum, Shenyang (Source: Courtesy of Gary Todd, Ph.D.).

The formal qualities of jades illustrated in Figure 1 at first glance warrant us to dissociate these artifacts from the concept of naturalism. Seemingly lacking referents in external reality, the three jades appear abstract. If they do not represent entities from the material world, a derivative assumption may be that they stood for something associated with the spiritual world. We then might deduce that people who attended funerals at colorful ceremonial centers featuring naturalistic works did not expect jade-makers to engage in a representational style aimed at naturalism in the first place. However, our analysis will highlight that Hongshan jade-makers were striving towards naturalism.13 They achieved their mimetic goals through an approach that combined several strategies and met the aesthetic sensibilities of their communities.

In a seminal article on Hongshan jades written before a broad corpus could be analyzed, Elizabeth Childs-Johnson captured what still aptly characterizes their style: “The Hongshan style is typified by a respect for expressive sculptural form and material luster. A jade’s edge is methodically rounded, and the surface carefully burnished in creating a wet, unctuous sheen. Features are delineated either as soft ridges and grooves, forming undulating wave patterns or as very shallow channels, creating delicate lines marking tusks or wrinkles of a snout. Lines defining features on smaller pieces may be crude but this quality is due to the limitations of size. Lathe marks sometimes appear, as on the interior of some horse hoof jades. In almost all cases the jade is handled as if modeled out of soft, pliable clay despite the jade’s otherwise obdurate hardstone property. Certain jades, such as the ‘pig-dragon’ and ‘horse hoof’ shapes, stand out three-dimensionally, expressive more as sculptures than as flat, two-dimensional images. Stylistically, Hongshan jades can be defined as both naturalistic and conceptual” (). The author further highlighted their sensuosity, a trait still emphasized in more recent characterizations.14 Since Meyer Shapiro’s 1953 publication of an essay on the topic, the term style has met detractors in art historical circles (). They include Robert Bagley, a scholar of art and archaeology in early China, who consigned the concept to the realm of arbitrary constructs (). Both authors, however, value visual comparisons to tease out more in-depth characterizations. Briefly relocating Hongshan jades in broader aesthetic and representational environments enabled a few observations. Another juxtaposition of the same jades with a product of the southeastern Liangzhu culture (3200–2300 BCE) might help refine what characterizes their style (Figure 2). Viewers confronted with the comparison would likely agree that the southern jade (Figure 2A) seems abstract too, in the sense that it may not have a referent visible in external reality. Further, they may qualify the Liangzhu object as comparatively more detailed, angular, rectilinear, and geometric. They might observe that smooth edges and thickness modulation confer a pulse on Hongshan jades. Ultimately, viewers may propose that Hongshan objects exhibit biomorphic qualities nonexistent in the Liangzhu form. Our study suggests that these four jade works are all representational and reproduce organic forms through stylistic expressions grounded in different visual environments.

Figure 2.

(A) Liangzhu culture jade cong at the Shanghai Museum; (B) Jade plaque from tomb N2Z1 M21 at Niuheliang; (C) Jade pig-dragon at the Capital Museum, Beijing; (D) Jade plaque at the Liaoning Museum, Shenyang (Source for the four photographs: Courtesy of Gary Todd, Ph.D.).

3. Stylistic and Evocative Considerations

Discussion on the style of Hongshan jades should focus on both macro- and micro-level concerns. The term style generally elicits distinctions among formal habits or conventions discernible within given places, times, or cultures, as well as the more idiosyncratic treatments individual craftsmen give to their work. Hongshan jade-makers undoubtedly produced artifacts whose shared aspects modern observers associate with Hongshan cultural expression. We certainly can account for the standards Hongshan jade-makers devised to represent entities and the distinct surface and edge treatments they tended to use. However, discerning concomitant individual crafting styles is more challenging. We do not know how many people produced the artifacts retrieved from Niuheliang and Banlashan tombs. Archaeologists dated these burials to the later phase of the Hongshan period (3500–3000 BCE), but limited stratigraphic data restrict inferences on the frequency or intensity of jade production over the course of that period. Formal distinctions exist among jades of the same type, but how these might correspond to different hands eludes us. A single person indeed could have produced several, but varied their work. Any inference about individual style would be tenable if we overemphasized the value Hongshan community members attributed to conventions, overlooked the freedom jade-makers likely enjoyed, and underestimated the creative and cognitive capacities of these prehistoric individuals. On that latter point, this study shows that Hongshan jade-makers at times relied on the same cognitive processes that Pablo Picasso and other Cubist artists deployed and demanded from their twentieth-century viewers. Considering formal variations within each jade category through the prism of putative personal styles could thus be misleading. Moreover, it would presuppose that the root of these variations lies solely in the jade-makers’ touch. Our study shows that formal variations within jade types at times resulted from the morphological variants observed in the represented entities. Reflecting on stylistic variations for the purpose of seriation remains helpful. Variants may indeed assist in estimating the sequence in which the objects were produced. Once we can identify principles formulated by Hongshan jade-makers, we may discern subsequent deviations from those standards. Knowing what entities craftsmen sought to represent in the first place would help develop sound seriation-based hypotheses. Their creations are undoubtedly puzzling.

The enigmatic shapes and imagery of Hongshan jades do not help elucidate the socio-religious life of communities who buried these artifacts with the deceased at ceremonial centers. Nor do we know the status of community members who crafted these jades, their relation to the deceased, or their involvement in rituals performed around death. While the jades’ placement inside tombs underscores their significance in socio-religious contexts, how community members felt about the objects and the creatures represented on them eludes us. Scholars of early China have sought to identify these zoomorphs to shed light on the beliefs that animated Hongshan communities. That search has led to a narrowed list consisting of bears, pigs, insects, birds, tortoises, dragons, phoenixes, and pig-dragons. In our quest to understand the Hongshan world, we may have overestimated the importance of represented creatures (and perhaps our faculty to identify some), underestimated the evocative power of materials during crafting processes, and overlooked the position of jades vis-à-vis the buried bodies. Ultimately, the approach may have obscured what Hongshan jade-makers were representing in the first place.

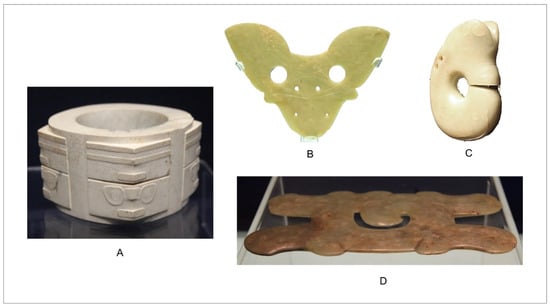

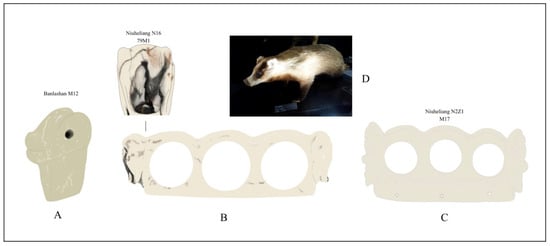

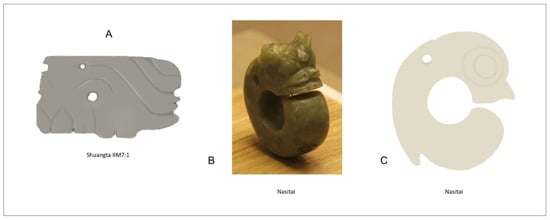

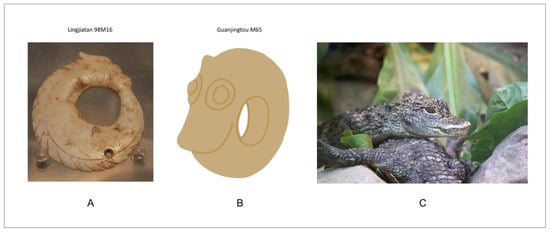

Two Hongshan jades featuring zoomorphic heads will help illustrate the issue (Figure 3A,B). The 2014–16 excavations conducted at the Banlashan site generated a jade representing the head of a creature (Figure 3A). Excavators introduced the object as an animal head-shaped handle finial (). A more recent analysis identifies a bear head and points to the ongoing significance of bear imagery in northeastern China from the Xinglongwa 兴隆洼 culture (6200–5200 BCE) to the Hongshan period (). Another jade calls our attention. Reports introduced a double-headed jade retrieved in 1979 from tomb N16 79M1 at Niuheliang as exhibiting two bear heads (Figure 3B) (). Excavators allocated the same animal species to clay paws, an ear, and a nose found inside the Goddess Temple (N1J1B), as well as a clay jaw recovered from the temple’s southern chamber (N1J1A) (). The jade’s original placement near the buried man is unknown, as it was found outside a disturbed tomb. The ornamental rope-pattern lining its lower edge reinforces the functional interpretation generally attributed to the object: a hair comb (). Despite the formal commonalities exhibited by these two Hongshan bear representations (Figure 3A,B), attention to material qualities encourages a reassessment of the bear classification. The unearthing of Asian black bear (Selenarctos thibetanus) bones at Niuheliang leaves no doubt that Hongshan communities were familiar with the species (see ). How communities involved in hunting and gathering felt about these impressive and potentially dangerous animals is a mystery. The species attribution for the two jade artifacts remains uncertain, as alternative identifications could apply. The creatures’ equally rounded ears and elongated snouts limit the range of options. Extending consideration to material factors may help. The Niuheliang jade coloration, mostly ivory with black and brown streaks, does not correspond to the pelt of Asian black bears. The black nose on each head, however, suggests that the jade-maker sought to exploit color streaks in the raw lithic used to craft the three-holed implement. In this context, we cannot exclude the possibility that the color streaks embedded in the medium inspired the thought of representing a specific animal species. The other jade comb retrieved at Niuheliang (from N2Z1 M17) exhibits a more unified creamy coloration, which better corresponds to the human heads crafted on its ends (Figure 3C). A possible contender whose snout, ear shape, and natural pelt find echo in the double-headed bear jade is the badger (Meles meles), a genus recovered at Niuheliang (Figure 3D) (see ).

Figure 3.

(A) Jade zoomorph from M12 at Banlashan; (B) Jade comb from tomb N16 79M1 at Niuheliang; (C) Jade comb from tomb N2Z1 M17 at Niuheliang (Source for the three images: LB and SLB on Procreate); (D) Badger (Meles meles) (Source: Daderot, CCO, via Wikimedia Commons).

The jade animal head unearthed more recently at Banlashan raises related issues. The artifact recalls a Hongshan jade exhibited at the National Palace Museum in Taipei (Figure 4C). These two jade heads exhibit remarkably similar eyes and ears, while their tapered lower bodies remain unparalleled in the known repertoire of Hongshan jades. Yet, the two creatures represented are undeniably distinct: one shows an avian figure, while the other evokes a mammal. Excavators hypothesized that the Banlashan jade functioned as a finial and its narrowed, tapered end as a tenon (). They speculated that it ornamented the handle of a large ceremonial stone ax found on the tomb occupant’s waist. This would be the first known occurrence of a ceremonial ax-handle deposited inside a Hongshan tomb, with others being found further south in other Neolithic cultures (). At this time, nothing makes certain that the Banlashan jade functioned as an ax-handle finial or that its mellow-looking creature represented a bear.15

Figure 4.

(A) Jade zoomorph from tomb M12 at Banlashan and (B) partial ground plan of tomb M12 at Banlashan showing the jade in situ (Source for the two images: LB and SLB on Procreate); (C) Jade zoomorph at the National Palace Museum, Taipei (Source: Courtesy of Gary Todd, Ph.D.); (D) Femoral condyles and shaft (Source: Author).

Stylistic considerations could explain why the avian jade creature and the Banlashan jade head exhibit the same ear-like projections. They might even point to a single jade-manufacturing site for the two artifacts. An alternative hypothesis involving material factors, however, can explain the recurrence and resemblance of both their ear-like projections and tapered lower bodies. To that point, the Banlashan jade position inside tomb M12 is significant. The object was found at mid-height of the deceased’s right thigh bone (Figure 4B). Remarkably, commonalities on both jades correspond to morphological features visible on the distal end and shaft of a human femur (Figure 4D).16 The creatures’ flat rounded ears recall femoral condyles, and their body wedging echoes the tapering occurring on the bone shaft. The bird jade exhibits similar condyle-like projections, and its body displays a ridge extraordinarily similar to the ridge (linea aspera) extending along a femoral shaft.

The badger heads adorning the Niuheliang comb emerged primarily because the black and brown mineral veining evoked the pelt of the animal. Natural patterning in the substance could be exploited to represent an animal whose cream-colored pelt featured black and brownish stripes. It happened to be a badger, an animal whose ears required that the craftsperson create rounded, projecting appendages. In contrast, the idea for the Banlashan bear-like creature emerged out of an osseous substrate (human femur), which a craftsman sought to partially reproduce in jade. The bone’s morphology brought to the jade-maker’s mind the image of a three-dimensional creature’s head. For this to happen, the jade-maker experienced pareidolia, a subjective cognitive process that entails projecting mental images onto natural material configurations or objects, as when, for example, one sees an animal in a cloud formation against a blue sky or a human figure in the root of a plant. Associated with artistic creativity throughout the world, perceptive imagination is linked to the emergence of figural imagery in prehistoric China beyond Hongshan culture.17 A foray into the wider world of Hongshan jades will show that this discrete cognitive process catalyzed figural representation beyond the jade creature retrieved from tomb M12 at Banlashan. The person who made this jade head experienced pareidolia triggered by more than form-likeness between the femoral condyles and ears. A more holistic set of triggers extending to other resemblances between bone and jade applied as well.

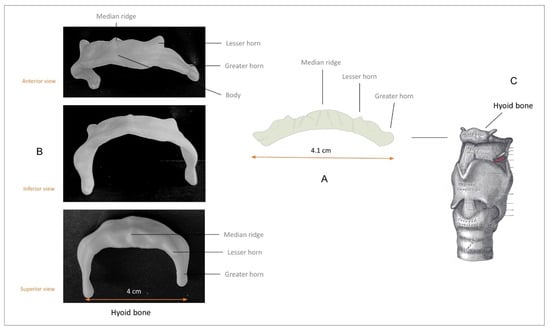

4. Jade, Bones, Mimesis, and Style

Symptomatic of a wider phenomenon involving human bone reproduction in Neolithic China, the Banlashan animal head jade did not emerge in a cultural and perceptive vacuum. Earlier interests and practices laid the ground for the cross-material phenomenon to emerge. Image-makers in Neolithic China at times displayed interest in a material-representation synergy, i.e., a partiality towards substances whose physical attributes are reminiscent of other substances (). In the area occupied by Hongshan communities in northeastern China, craftsmen working in the earlier Xinglongwa culture sought to represent, approximate, or at least evoke certain raw materials through other substances. For example, they used the lining of shells to represent teeth, acknowledging the whiteness and shine of enamel. They also selected jade to represent bone objects. At Chahai 查海, an important Xinglongwa culture site in Fuxin county of northwestern Liaoning province, people used jade to represent bone scoops (bixingqi 匕形器) regularly found at Neolithic sites (see ; ). At Chahai and the Baiyinchanghan 白音长汗site in Inner Mongolia, community members further used the material to craft small tubes. While they perhaps functioned as beads, they also evoked bone shaft sections (see ; ). A Hongshan tomb at Niuheliang (N2Z1 M26) yielded a similar 4 cm long tubular jade (see ). Archaeologists found the object on the right side of the deceased’s chest, apparently between the upper arm bone (humerus) and a lower bone (radius or ulna). Perhaps the object functioned as a bead, but its extremities exhibit different diameters, and a protuberance running along its shank recalls the ridge running along a humerus, radius, or ulna bone shaft.18 Hongshan jade crafting practices may well have entailed signifying a long bone through a single, elemental component (a shaft segment or a long-bone end). A synecdochical approach focused on representing one portion to stand for an entire long bone allowed craftsmen to save some valuable jade material while approximating the natural girth of their bony referent.

We cannot determine what came first in Xinglongwa culture—the sight of jade lumps whose aspect was reminiscent of bones and consequently triggered the thought of transforming a lump of this rare substance into a bone implement or bone-like bead, or simply the idea of representing bone artifacts in a rare material. The uncanny resemblance of jade and bone likely made the substances cross-referential, as visual aspects shared by both materials encouraged craftsmen to substitute one for the other. Nephrite, the type of jade used at Xinglongwa culture sites, is a silicate of calcium, iron, and magnesium, whose felted microcrystalline structure renders it notoriously tough and thus hard to abrade. The material comes in hues and colors directly affected by its mineral components. For instance, a magnesium-rich silicate matrix tends to appear grayish white; a few iron oxides may add yellow-brown or brown streaks to the matrix, while an iron-rich nephrite will verge towards dark green (; ). Apart from the color variability possible in nephrite (demonstrated by Xinglongwa culture jades), the mineral also exhibits varied degrees of translucence and opaqueness that artisans would have appreciated.19 Notably, nephrite’s translucence and opaqueness is also visible on bones, a material that Xinglongwa people were used to handling and looking at when making tools. Bones primarily are an opaque substance formed by living organisms combining cells and fibers embedded in a variety of minerals (particularly calcium phosphate, from which bones derive their hardness) and proteins (notably collagen, which confers tensile strength), but they also incorporate translucent patches of cartilage, a tough connective tissue composed of collagen fibers ranging in color from yellowish to bluish-white. Perhaps the unusual similarity of nephrite and bone invited substitution and stimulated a desire to reproduce these bone objects ().

The Xinglongwa and Hongshan people shared cognitive and perceptive predispositions. They did not handle the unprocessed raw materials used to make objects in a perceptual vacuum. In small communities accustomed to slaughtering animals for food and turning their bones into tools, jade-makers were better acquainted with the sight and feel of osseous remains than we are. The visual and material environments in which the Xinglongwa and Hongshan people lived were close enough; they also were profoundly different from ours. Projecting contemporary expectations about what constitutes mimesis on jade works would be misguided and prevent deeper appreciation for the array of representational endeavors these neolithic communities engaged in. In prehistoric China, mimesis operated on a range of levels and through a combination of perceptive channels (). How and how well a jade artifact may have represented another entity depended on more than form alone. Material resemblance between bone and jade would have contributed to how mimetic any bone representation made with jade would have appeared to Xinglongwa and Hongshan community members. In other words, naturalism would have been judged at both the formal and material levels.

Related contextual factors deserve attention when addressing Hongshan jade styles. These objects were experienced in milieus where people appreciated better than we do the qualities that bone shared with jade. In such a perceptual context, jade-makers could rely on material resemblance in their mimetic enterprise and lessen their attention to formal likeness. Another factor, position-induced associations, likely lowered the formal resemblance threshold viewers expected. The physical proximity between the jades and the bodies they accompanied inside tombs enhanced the object–bone link. As the next section aims to show, Hongshan community members tended to position jades on or near the human skeletal constituents they represented. The jade objects’ proximity to their somatic referents likely further reduced original viewers’ expectations about how formally naturalistic a jade bone needed to look. In turn, these prehistoric circumstances deserve our attention when assessing Hongshan jade styles. Indeed, they ought to lower our threshold of what constitutes form-likeness when we assess jade’s naturalism. They additionally ought to increase awareness that Hongshan viewers perceived abstracted jade forms as more mimetic than we might. Ultimately, a greater tolerance for jade somatic abstractions should expand the range of stylistic variants we identify for each jade type under study.

5. Hongshan Jade Bones

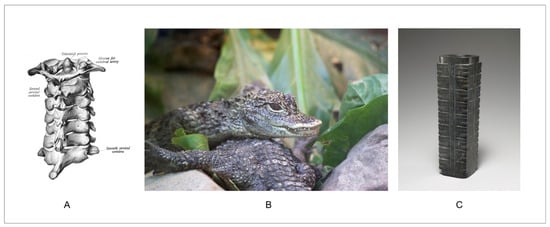

5.1. Human Bones in the Visual Environment

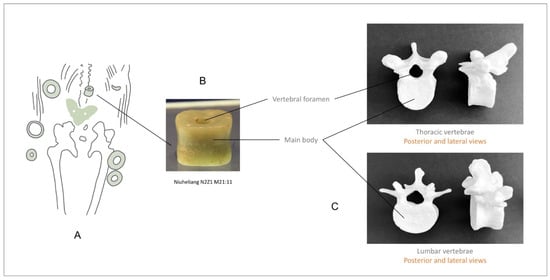

Visual exposure to human skeletal remains in the Hongshan cultural sphere far exceeded the experience of most modern humans. Hongshan communities practiced secondary burials, as demonstrated by the large quantity of such tombs at the Niuheliang and Banlashan cemeteries. The practice entailed unearthing the decayed remains of a person buried a first time and burying the skeletal remains a second time. This funerary practice exposed communities to the sight, manipulation, and transportation of human bones. Another activity possibly subjected community members to the view of human body parts. Skeletal remains found around or embedded in sacrificial altars and pits point to the possibility that human sacrifices occurred at Dongshanzui and Niuheliang (; ). Katrinka Reinhart discussed cases of human sacrifice, post-mortem dismemberment, and transportation of body parts in other parts of China during Neolithic times (). The presence of human and donkey bones inside an altar sacrificial pit at Banlashan (JK1), of human bones under the altar at the Niuheliang Locality 5, and of partial skeletons inside Hongshan graves imply that some Hongshan ritual activities performed at ceremonial centers may have involved human bodies. Secondary burials, and perhaps human sacrifices, must have heightened the visual knowledge and awareness that community members had of human anatomy. These practices also provide some context for how jade-makers would have had access to human bones. Once human bones entered the visual field of Hongshan communities, their members became susceptible to developing the type of associations that contemporary osteologists make. Descriptions of osseous components tend to involve body imagery, notably referring to the “head” or “neck” of a bone. Radiologists, moreover, are prone to pareidolia-induced mental images involving animals when observing bones (; ). Let us now turn our attention to the world of jades unearthed from Hongshan graves.

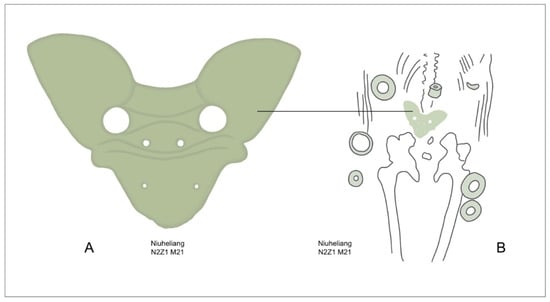

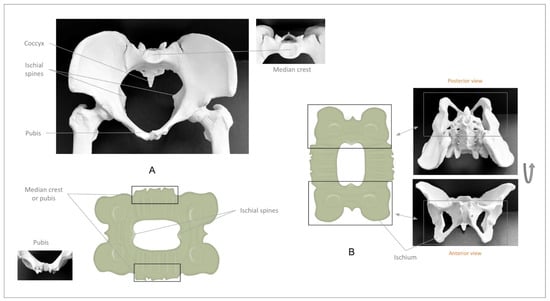

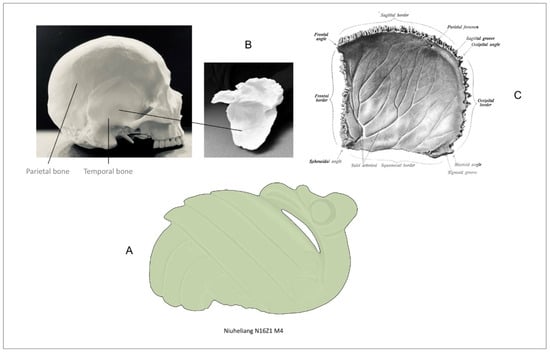

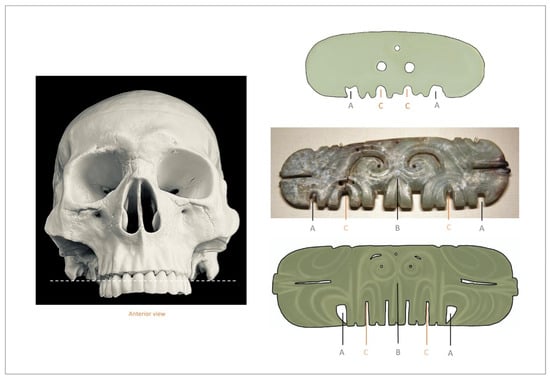

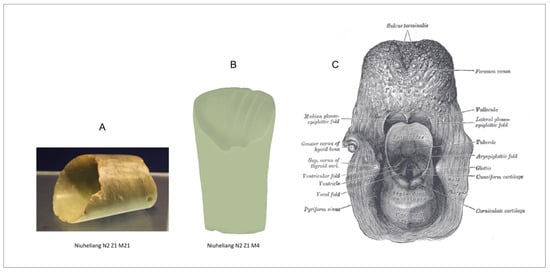

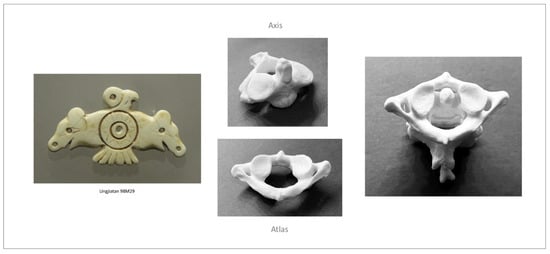

5.2. A Creature

In 1989, archaeologists opened the N2Z1 M21 tomb at Niuheliang, the resting place of a man who died in his thirties towards the end of the fourth millennium BCE. The tomb contained 20 jades, a large number by Hongshan standards. Among those interred with the deceased, a 14.7 cm wide wedge-shaped jade plaque remains unique in the known jade corpus (Figure 5A). A ground plan of the tomb shows the object in situ placed flat on the deceased’s pelvic area (Figure 5B). Thin, sunken lines of unmodulated width and circular apertures give the jade the appearance of a creature’s head seen from a frontal vantage point. Classified by archaeologists as an ‘animal mask’ (; ), the arresting piece led specialists of early China to note a resemblance with pigs and pig-dragons, mysterious creatures quintessentially associated with this northeastern jade tradition. The piece does exhibit facial features evocative of a creature. However, the jade’s triangular shape, size, and placement on the deceased raise the possibility of a more fundamental link with skeletal remains.

Figure 5.

(A) Jade plaque from tomb N2Z1 M21 at Niuheliang and (B) ground plan showing the artifact in situ (Source: LB and SLB on Procreate).

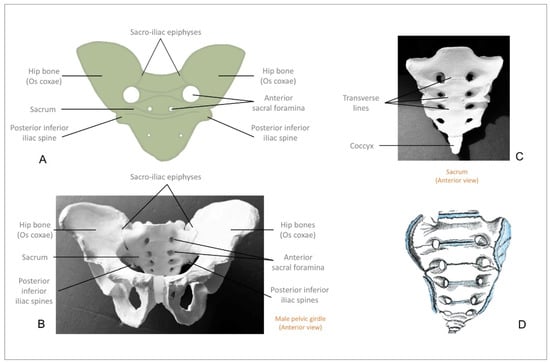

The artifact, indeed, resembles the posterior part of a human pelvic girdle and, more precisely, a composite of two hip bone wings and a sacrum (Figure 6A,B). Significant pelvic girdle components, hip bones (os coxae), articulate with the vertebral column through the sacrum–coccyx complex. The wedge-shaped sacrum itself consists of vertebrae aggregate, which tends to fuse in old age with the coccyx, a smaller vertebral group marking the end of the axial skeleton (see ). To capture this significant skeletal articulation point linking the vertebral column to the basin and lower limbs, the jade-maker did not seek to represent the more complex pelvic osseous ensemble. To render the shape of a sacrum articulated with posterior hip bone segments, the person simply trimmed a lump of nephrite into a triangular mass. Not that this was an easy task, as jade is a notoriously hard substance that requires intensive abrasion to cut. A subsequent task entailed lowering the upper edge center to create lateral projections. Two diaglyph lines standing for sacro-iliac epiphyses sufficed to enhance the hip bone–sacrum legibility. Intent on fashioning a realistic reproduction, the craftsperson incorporated other human bone features, but not without giving them a zoomorphic twist. This impulse likely resulted from observations of sacral morphological features. Before growing into a compact osseous mass (Figure 6C), the human sacrum consists of five isolated sacral vertebrae that fuse together through a lengthy process (). The resulting delineations and openings at fusion points were not lost on the jade-maker. Once bonded, the bony mass bears circular apertures between sealed vertebrae. These holes (sacral foramina) allow nerves and veins to pass through the fused bone mass and correspond to circular apertures made on the jade. Also visible on a human sacrum are horizontal lines (transverse lines) left where the sacral vertebrae merge. Their fusion degree is age-dependent, so the resulting horizontal lines (transverse lines) range from open (unfused) to barely visible threads (fully fused).20 The two uppermost sacral vertebrae do not fully fuse before puberty (). The jade-maker (or an intermediary community member) must have observed a not-fully-fused human sacrum and projected onto it the mental image of a grinning creature (Figure 6D).21 By slightly modifying the size or position of sacral features (sacral foramina and transverse lines) replicated on the jade bone, the craftsperson skillfully reproduced the mental image. The circular openings became signs supporting two referents: sacral foramina and a creature’s eyes and nostrils. The thin intaglio lines representing transverse lines also operated as definers of facial features (notably the mouth). Additional jades analyzed later in this article incorporate pareidolia-induced mental imagery incurred during visual and physical engagement with human bones.

Figure 6.

(A) Jade plaque from tomb N2Z1 M21 at Niuheliang (Source: LB and SLB on Procreate); (B) Human pelvic girdle; (C) Human sacrum (Source: Author); (D) Partially unfused sacrum (Source: Gray’s Anatomy of the Human Body, 1918; public domain).

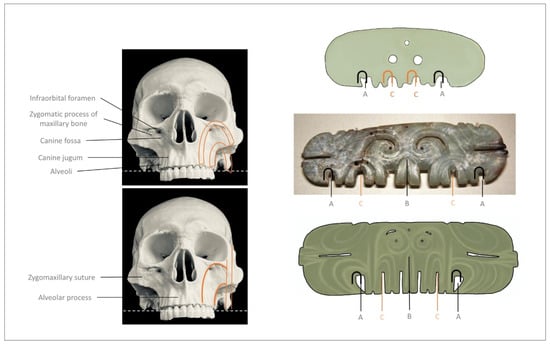

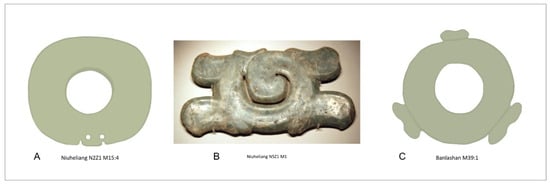

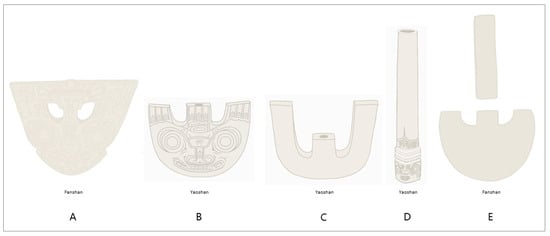

5.3. Hooked-Cloud Shapes (勾云形)

5.3.1. Overview

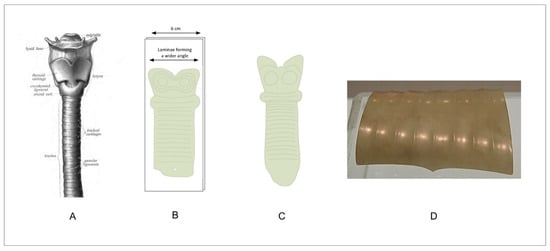

This jade category consists of irregular rectangular plaques defined by two parallel wavy horizontal sections connected through two shorter vertical segments. The ensemble frames a central aperture partially filled with a hook-shaped appendage. With that basic shape as model or in mind, craftsmen have engaged in substantial stylistic variations, resulting in a wide array of configurations observable in museum collections. Archaeologists discovered the hooked-cloud plaque shown in Figure 7 inside a Niuheliang tomb (N5Z1 M1). This mysterious jade type has invited a breadth of iconographic interpretations (; ; ). Associated with cloud imagery, the plaques have been viewed as celestial bodies or sculptural portrayals of an array of creatures: deer, boar, horned owl, phoenix, dragon, pig-dragon, turtle, or the taotie 饕餮, a common motif on Bronze Age artifacts.22 Since these hooked-cloud plaques have recognized archaeological contexts, our analysis first will focus on specimens retrieved from tombs at Niuheliang and one from M1 at Hutougou. This controlled corpus will help establish a baseline. Less than a centimeter thick, these flat artifacts range in length from 8.8 to 22.5 cm. Most occupy a comparable position vis-à-vis the buried body: the waist area.23 This common placement is critical to understanding what Hongshan craftsmen had in mind when abrading raw jade into these enigmatic artifacts—the jades represent the bony human pelvic area some were found atop inside graves. This osseous assembly is more complex and occupies a greater volume than the posterior section represented on the sacro-iliac jade analyzed earlier (Figure 6A). It consists of a three-dimensional bony ring (pelvic girdle) articulated through notches (acetabula) with the proximal ends of the femurs. Jade-makers faced challenges in reproducing this skeletal structure.

Figure 7.

“Hooked-cloud” jade plaque from tomb N5Z1 M1 at Niuheliang (Source: Courtesy of Gary Todd, Ph.D.).

Twenty-first century viewers acquainted with contemporary illustrations of human pelvic girdles articulated with the femurs (Figure 8A) might be disappointed by pre-modern renderings (Figure 8B–E). Recent two-dimensional diagrams owe much to prints and drawings done by artists who, since the Renaissance, have been interested in human anatomy, shading-based modeling, and volumetric perspectival composition. Modern readers of books on anatomy might even expect to find frontal, lateral, and dorsal skeletal views, exemplified here by what J.G. Heck did for his 1851 Iconographic Encyclopedia of Science (Figure 8B). Following the perspectival tradition, each illustration renders skeletal details observed from a single vantage point. Image-makers working outside that tradition resorted to an array of representational strategies, opting for flattened and abstracted forms capturing different angles within a single, compressed representational field (Figure 8C–E).

Figure 8.

(A) Diagram of a female skeleton (Source: Mikael Häggström, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons); (B) Heck, J. G. Iconographic Encyclopaedia of Science, Literature, and Art Vol.1 (1851), Plate 122 (Public domain); (C) Woodcut illustration of a human skeleton in Hieronymus Brunschwig’s Buch der Cirurgia; Strasbourg: Johan Grüninger, 1497, Plate 261 (Public domain); (D) Illustration of a human skeleton in Mansur ibn Ilyas, Tashrih-i badan-I insan [Anatomy of the Human Body], Iran, ca. 1390, Plate 57 (Public domain); (E) Nomenclature of human bones in Song Ci, Collected Records on Washing Away of Unjust Imputations, 1843 edition (Public domain).

Disconnected from perspectival conventions and expectations, Hongshan jade-makers followed principles akin to those lauded since the advent of Analytic and Synthetic Cubism. To appreciate their creations, we first need to set aside expectations about what representations ought to be. Far from being illusionistic by current standards, the jade compositions remain no less representational than modern renderings. The craftsmen had no qualms about conflating several vantage points within the same plane to account for their model’s three-dimensionality. They indeed faced constraints that impacted what they could do: the limited availability, size, and shape of raw jade. Slabs were economical for image-makers unconcerned by representational conventions of other times. Collapsed pelvic girdles visible when exhuming decayed bodies for secondary burial displayed an osseous structure compressed onto a more level plane, a sight that further legitimated flat renderings. As the analysis will show, some craftsmen managed to replicate remarkable anatomic details within the flattened field allocated by jade slabs. They developed their own standards, but evidence shows that they were open to stylistic variation, notably when pareidolia-induced figural imagery emerged.

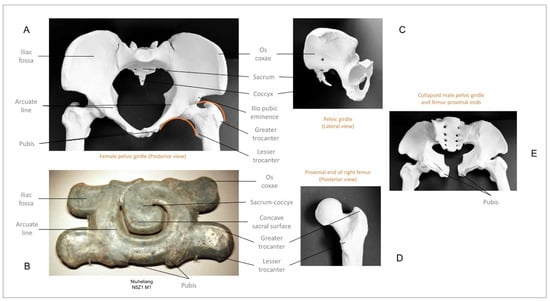

5.3.2. Representational Conventions at Niuheliang and Hutougou

A comparative analysis between a skeletal replica and a hooked-cloud plaque found inside tomb N5Z1 M1 at Niuheliang will help establish how this Hongshan jade type is the sculptural rendering of a human skeletal midsection (pelvic girdle and upper femurs) (Figure 9A,B). Publications regularly present the jade plaques, with their central hook extending upward. Plaques in situ, however, tend to have the hook extending downward towards the deceased’s feet. The N5Z1 M1 jade follows the proper orientation as its hook extends downward into the central aperture, like the vertebral column’s lowest segment (sacrum–coccyx complex) does towards the pelvic inlet (Figure 9A).24 To signify the complex nature of this skeletal structure, jade-makers devised a solution: an appendage projecting downward and whose tip points rightward. The convention brought resolution to a challenge: representing the sacrum–coccyx’s triangular shape while acknowledging that it curves anteriorly towards the pubis. Evidently, a flat slab could not accommodate the depth effect. Aware that the sacrum–coccyx angle is best appreciated when looking at a pelvic girdle from the side, jade-makers rendered it as if observed from a lateral left viewpoint (hence the hook pointing rightward) (Figure 9C). By conflating more than one vantage point, Hongshan craftsmen accounted for the three-dimensional nature and pointy shape of a curved, osseous appendage extending into a hollow girdle. To acknowledge the sacral surface’s concave nature, they abraded the jade appendage to give its central plane a smooth, slightly sunken aspect. They used a similar surface treatment to represent other concave bony surfaces. They reduced hip bones (os coxae) to lateral upper segments, featuring smooth, rounder outer edges. Craftsmen allowed the jade plaque to approximate the hip bones’ thickness but abraded their central plane down to reproduce the concave surface of the iliac fossae (Figure 9A,B). To represent this smooth depressed area, jade-makers applied the wagouwen 瓦沟纹 surface treatment so quintessentially linked to the style of Hongshan jades. Another convention consisted of abstracting the pelvic ring into a spiral ending in the sacrum–coccyx complex. Craftsmen reproduced the relief line surrounding the pelvic inner ring (arcuate line). Further form reduction was required to represent lower skeletal components. They made lower lateral segments slightly longer than their two upper counterparts, here echoing the width between two femurs whose heads articulate with the girdle through acetabula. The craftsmen extended the arch, spanning from the greater femoral trochanter edges to the iliopubic eminences on the girdle. They offered the same treatment to the arch bridging the lesser femoral trochanters and the pubis (orange arches in Figure 9A). They represented depressed areas between femoral heads and trochanters through smooth surface depressions akin to those used to render the iliac fossae of hip bones (Figure 9D). They also reproduced the pubis as visible on a collapsed pelvic girdle (Figure 9E).

Figure 9.

(A,C) Female pelvic girdle (posterior and lateral views) (Source: Author); (B) Jade plaque from tomb N5Z1 M1 at Niuheliang (Source: Courtesy of Gary Todd, Ph.D.); (D) Proximal end of the right femur (posterior view); and (E) Collapsed male pelvic girdle (Source: Author).

To sum up, faced with the difficult task of representing a complex three-dimensional bone structure featuring uneven surfaces on a flat jade slab, Hongshan craftsmen developed conventions. They abstracted forms, reducing them to elemental shapes: a spiral ending in a pointed tip stands for a girdle ring–sacrum–coccyx osseous complex; four lateral segments signify two iliac wings and two femoral heads articulated with the girdle. They conceived of their jade midsections as sculptural forms, but needed to compress their volume. To that end, they conflated into a single flat field the structures observed from different vantage points (lateral and posterior). To account for some sunken bony surfaces (iliac fossae), they abraded jade planes into smooth concave planes. They used the same surface treatment to represent other sunken features of the bones.

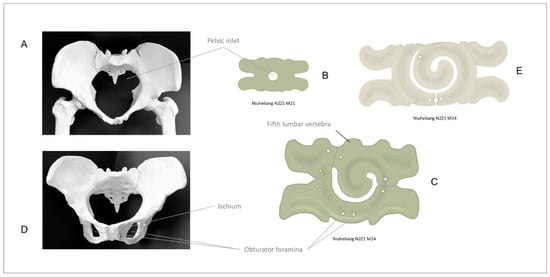

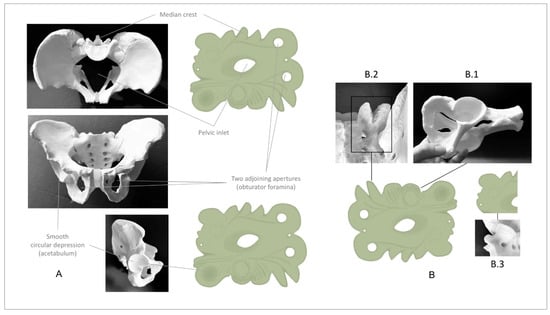

5.3.3. Stylistic Variations at Niuheliang and Hutougou

Most hooked-cloud jades found at Niuheliang and Hutougou exhibit the conventions identified in the previous section. Some plaques display stylistic variations, defined here as tangible departures from these standardized forms. First, some formal variants resulted from the subtraction, or addition, of morphological features observed on the bony models represented. This applies to the diminutive plaque from tomb N2Z1 M21, whose pelvic inlet the jade-maker reduced to a sacrum-free circular opening. Slight rotations exerted on a female pelvic girdle observed from a superior view expose or conceal the sacrum’s projection into the pelvic inlet (Figure 10A,B). The jade from tomb N2Z1 M24 exhibits other changes derived from bone morphology (Figure 10C). Its maker added the fifth lumbar vertebra atop the sacrum and two lower apertures representing the openings (obturator foramina) on the ischium bones (Figure 10C,D). Therefore, we need to reconsider the attachment function generally ascribed to these double apertures. Second, other formal variants occurred when craftsmen engaged in greater form abstraction. This applies to the N2Z1 M14 plaque (Figure 10E) and its similar counterpart from grave M1 at Hutougou. The makers further abstracted the pelvic ring–sacrum–coccyx spiral, reducing the osseous form to a coiled band of unmodulated width, ending in a rounded tip. Moreover, they created four identical jade segments to denote upper and lower lateral projections, therefore employing a single form to stand for skeletal components of different shapes (iliac wings and femoral upper sections). In doing so, they relied on a discrete cognitive ability they shared with fellow community members: the capacity to communicate through visual signs.

Figure 10.

(A,D) Pelvic girdles (Source: Author); (B) Jade plaque from tomb N2Z1 M21 at Niuheliang; (C) Jade plaque from tomb N2Z1 M24 at Niuheliang; and (E) Jade plaque from tomb N2Z1 M14 at Niuheliang (Source: LB and SLB on Procreate).

Readers familiar with the work of twentieth-century Cubists may notice that Hongshan craftsmen followed similar representational approaches: forms abstracted into elemental shapes, several vantage points conflated within a flattened field, and forms reduced to signs standing for several referents. Two plaques exhibiting more striking stylistic variations even reveal that these prehistoric jade-makers engaged in semiotic play akin to that evidenced in Cubist compositions (Figure 11A,B). Discovered on the deceased’s pelvis inside N2Z1 M23 and N2Z1 M26 at Niuheliang, the jades not only exhibit greater formal changes but also incorporate zoomorphic aspects. Following representational habits, their makers reduced osseous–morphological features to basic shapes while rendering a skeletal midsection as if observed from multiple vantage points. However, they conceived of the works as sculptural and the surfaces as representational fields. The jades concomitantly embody a human midsection and the mental images of creatures visualized on the bony models. For this purpose, the craftsmen did not shy from engaging in semiotic play. They indeed created forms (signifiers) whose meaning (signified) shifted within each composition.25

Figure 11.

(A) Double-owl jade plaque from tomb N2Z1 M26 at Niuheliang, and (B) Phoenix and dragon jade plaque from tomb N2Z1 M23 at Niuheliang (Source: LB and SLB on Procreate).

- The Double-Owl Plaque

Archaeologists discovered the first of these two jades on the waist of a man buried inside N2Z1 M26. They identified the two avian heads visible on the thin (0.6 cm thick) 12.9 by 9.5 cm plaque as owls (Figure 12A). I classify the plaque as a midsection skeletal rendering. Its maker gave the work a conventional silhouette (two parallel, wavy horizontal sections framing a central aperture), but omitted the sacrum and elongated the pelvic inlet. The composition, however, includes anatomic details absent from more conventional examples. To include some of these details, the craftsperson had to engage manually with a bony pelvic girdle. As detailed in Figure 12A, the work presents an oval central aperture lined with opposite prongs, inspired by ischial spines. Its parallel three-pronged crenelations stand for the corrugated edges of pubic bones or sacral crests. As for the conspicuous avian faces embedded in the jade pelvic matrix, pareidolia-induced vision may well have struck a person (the craftsmen or an intermediate) who manipulated a human pelvic girdle. A 180-degree rotation sufficed to conjure up the sight of two different avian faces that the craftsman then rendered on the jade plaque (Figure 12B). To operate, the mental images depended on semiotic reordering, a process whereby a bony configuration functioned as a sign whose signified changed upon rotating the pelvic girdle. Observed from a posterior view, the osseous structure features a coccyx (here reduced to a sign) that is readable as an upward pointy projection on a bird’s head (signified 1). From an anterior view, however, the same coccyx points toward another referent: an avian beak (signified 2). A similar phenomenon occurs with the two pelvic girdle ischia. Reduced to a sign, each ischium stands for a wattle-like appendage observed from the same anterior view. From a posterior view, the same bony formation stands for another signified: an excrescence above an avian eye. The jade plaque itself demonstrates that the Hongshan craftsmen engaged in semiotic play. The two opposing pointy protuberances on the inner rim stand for three distinct referents. They represent bony ischial spines (signified 1) that operate as two different avian features. Each spine stands for a beak (signified 2) and a head protuberance (signified 3): a beak on the upper face and a head protuberance on the lower bird. Hongshan viewers would have noticed, if not appreciated, the semiotic play in this jade composition.

Figure 12.

(A,B) Osseo-morphology of a rotated pelvic girdle as source of inspiration for the double-owl plaque (Source: LB and SLB on Procreate; photographs by the author).

- 2.

- The Phoenix and Dragon Plaque

As the double-headed owl plaque shows, once Hongshan jade-makers conceptually reduced skeletal midsections to irregular rectangular shapes and pelvic inlets to voids, they enjoyed stylistic freedom. Archaeologists discovered a jade inside N2Z1 M23 deposited on the tomb occupant’s pelvis (Figure 13A). From its zoomorphic imagery, they inferred that Hongshan communities already worshipped the phoenix and the dragon, two mythical creatures associated with historical China. I classify the item as a midsection skeletal representation, which demonstrates a tenuous attachment to representational standards and shows the artistic freedom enjoyed by its maker. The plaque orientation in Figure 13A corresponds to the placement made by mourners who deposited the jade on the tomb occupant. By doing so, they deliberately positioned jade skeletal details on top of the corresponding bony areas they represented. So, the three-pronged crenelation on the plaque’s upper edge was atop the deceased’s sacral median crest. The smooth circular depression on the plaque’s lower left corner corresponds to the deceased’s right hip socket (acetabulum), the articulating point for the thigh bone and hip bone. The person who crafted the artifact paid attention to another significant anatomic detail overlooked in other renditions: the two large openings (obturator foramina) on the ischium bones. The craftsperson could rely on shared knowledge with other community members who, used to seeing human bones in the context of secondary burial practices, knew that pelvic girdles feature a large pelvic inlet but also two adjacent apertures (obturator foramina). The three openings’ differentiated sizes and relative positioning on the jade plaque sufficed to activate their representational charge in viewers’ minds. The jade-maker, moreover, embodied the pareidolia-induced mental images experienced during the manipulation and observation of bony models (Figure 13B). Lateral plaque rotations reveal three different profiles: a “dragon” and two avian heads. Two collapsed hip bones (os coxae) can notably produce a profile reminiscent of the “dragon” head (Figure 13B.1). Once more, the jade-maker could rely on fellow community members’ appreciation of signs pointing at different referents. Accordingly, the smooth circular depression added to mark a hip socket (acetabulum) could carry another semantic charge: a creature’s nostril. Two short and pointy bony projections (superior articular processes visible on a sacrum’s upper edge) near a circular opening (a sacral foramen through which blood vessels and nerves pass) likely evoked the mental image of a left-facing long-beaked bird (Figure 13B.2). Observed from the other side, the same bony formation may have inspired the creation of the avian head profile positioned near the sacral crest (Figure 13B.3).

Figure 13.

(A,B) Osseo-morphology of a rotated pelvic girdle as source of inspiration for the phoenix and dragon jade plaque; (B1–B3) Osseous configurations conducive to pareidolia-induced imagery (Source: LB and SLB on Procreate; photographs by the author).

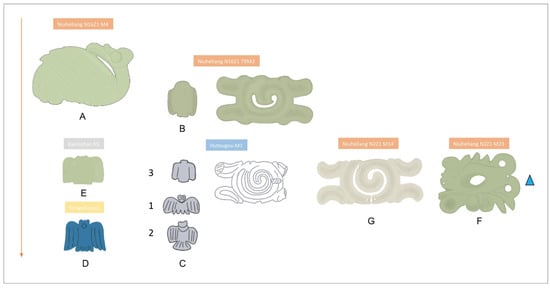

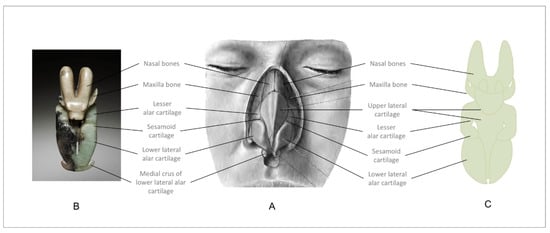

5.4. Birds at Niuheliang, Hutougou, Dongshanzui, and Banlashan

5.4.1. Styles and Seriation

Archaeologists working at Hongshan culture sites have excavated a few other jade bird representations (Figure 14). They include an exquisite bird profile (Figure 14A) and several smaller avian figurines discovered at Niuheliang (Figure 14B), Hutougou (Figure 14C), Dongshanzui (Figure 14D), and more recently at Banlashan (Figure 14E). The Dongshanzui image-maker crafted the figurine out of turquoise, a substance also selected for two Hutougou fish-like pendants as well as semi-circular and triangular ornaments recovered from tombs N16 M4 and N2Z1 M23 at Niuheliang (Figure 14F).26 Image-makers likely crafted the Dongshanzui bird figurine from the same turquoise matrix as the pendant found inside N2Z1 M23 at Niuheliang (both items feature a turquoise front and a black back)—a contemporaneous dating for both jades is thus possible. Stylistically, two jade avian figurines from tomb M1 at Hutougou (Figure 14C1,2)) are closer to the Dongshanzui turquoise bird (Figure 14D) than to the Niuheliang jade figurine retrieved from N16 79M2 (Figure 14B). Necks dissociate heads from bodies, feathered wings expand laterally, and tails appear fanned, while well-defined eyes and beaks enliven the avian faces. The third Hutougou figurine (Figure 14C3) is more schematic. Lacking wing bars and facial features, it stylistically appears closer to the Banlashan specimen (Figure 14E). The most abstract of all renditions is the barely representational, unique avian figurine recovered at Niuheliang (Figure 14B) (). The 2.45 cm tall jade lacks facial features and presents vaguer head–body and wing–chest differentiations. The image presents a particularly rounded silhouette, its zoomorphic qualities barely emerging from the mineral matrix. Excavators found this jade bird inside a grave also furnished with a jade skeletal midsection (Figure 14B).

Figure 14.

Preliminary seriation chart for avian figurines excavated at Hongshan culture sites. (A) Niuheliang N16Z1 M4; (B) Niuheliang N16Z1 79M2; (C1–3) Hutougou M1; (D) Dongshanzui; (E) Banlashan K5; (F) Niuheliang N2Z1 M23; (G) Niuheliang N2Z1 M14 (Source for all the images: LB and SLB on Procreate).

Considering stylistic observations explained earlier, the N16 79M2 pelvic–femoral rendering exemplifies early representational conventions, and thus likely predates counterparts found inside N2Z1 M14 (Figure 14G) and N2Z1 M23 (Figure 14F). The assumed contemporaneity of turquoise items found at Dongshanzui and inside N2Z1 M23 further lends support to the hypothesis that the sole avian figurine found at Niuheliang predates other excavated specimens in that Hongshan jade category. Accordingly, nothing suggests that its maker sought to represent the well-defined owl-like bird of prey later depicted elsewhere. As art historians well know, inferring the relative dating of figural works based on how abstracted or formally naturalistic they appear is methodologically unsound. Schematic renderings may predate or postdate more formally mimetic works. Without our initial jade midsections analysis and material evidence (turquoise artifacts), asserting that the barely legible N16 79M2 bird rendering predated more articulated and detailed figurines was untenable. Remarkably, excavators at Niuheliang clearly established that the N16 79M2 tomb postdates the N16 M4 tomb (see ). Consequently, not only did Hongshan craftsmen produce well-defined avian figurines after this simple specimen from Niuheliang, but evidence suggests that they crafted this tenuously representational piece after the exquisite avian plaque found inside N16 M4 (Figure 14A). As placement inside each grave may not correspond to the years during which each was crafted, we cannot specify the relative dating. Setting aside the order in which they were produced, both works exhibit soft rounded outlines, yet exhibit a noticeable mimetic disparity. Attributing this distinction to their makers’ putatively unequal representational talent, however, would rely on the assumption that they sought to represent the unmediated sight of a bird observed in nature. Considering each bird in isolation, focusing on its form and position inside each grave will suggest otherwise.

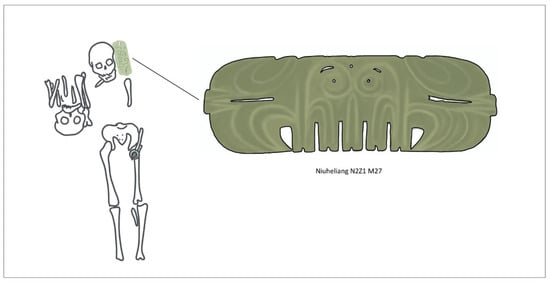

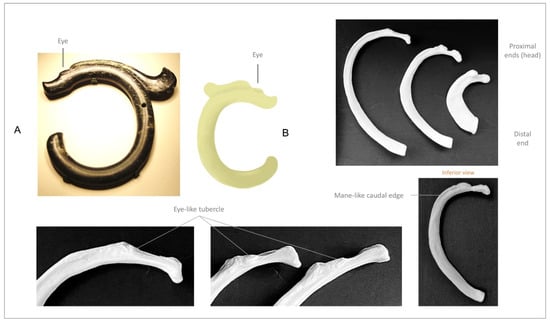

5.4.2. Two Full-Bodied Avian Representations from Locality 16 at Niuheliang

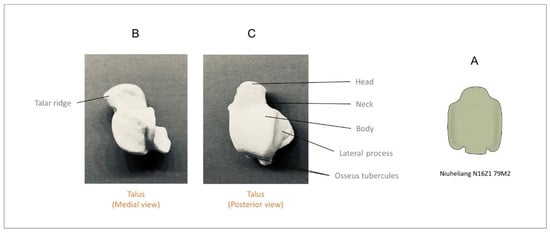

- Small bird

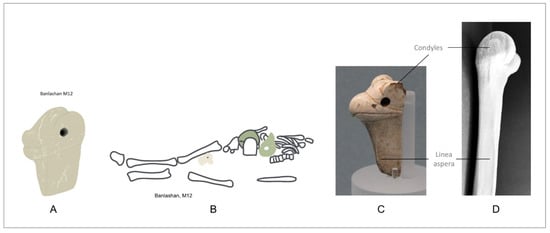

Recovered from N16 79M2 during the 1979 excavations, the 2.45 cm piece was located near the tomb occupant’s feet (Figure 15A) (). The jade is barely representational and devoid of any attention to feet, plumage, or even eyes. Presented en face, its oblong head is disproportionately broad and stout. A wide, soft angle extending from one shoulder to the other signifies the presence of a beak and contributes to the avian interpretation. Facial topography is reduced to a slight depression around the beak area and two tiny V-shaped depressions on the forehead. Narrow lateral ridges, connected to the chest through smooth, concave transitions, denote wings on a centripetally compact body. The chest is broad and squarish. Two notches abraded on the bottom edge evoke a tail. Perhaps its maker simply sought to represent a bird.

Figure 15.

Comparison between a talus bone and the avian figurine found inside tomb N16Z1 79M2 at Niuheliang (Source: (A) LB and SLB on Procreate; (B,C) photographs by the author).

However, considering crafting practices discussed earlier and the jade’s position near the deceased’s feet, an osteo-morphological link is conceivable. Remarkably, the shape the craftsmen gave to this avian figure echoes the form of a significant tarsal bone (Figure 15B,C). Composed of seven osseous components, the ankle joint complex mediates the lower leg with the sole and toes. Its largest bone at the heel (calcaneus) supports the second largest ankle bone (talus), which anchors and articulates directly with the tibia and fibula (). The talus figures among the bones regularly described in scientific literature with terms such as “body”, “head”, and “neck”. The terms, respectively, differentiate the bulk, the rounded section articulating with the navicular bone, and the recessed area separating the two. The medial view of a talus shown here may be conducive to a pareidolia-induced image of a bird profile, its lateral process evoking a wing (Figure 15B). The bone’s resonance with the profile of a bird likely explains why osteologists call a pointy excrescence present on a talus head a “beak” (see ). Even in the absence of a sharply pointed growth on a talus head, morphological variations of human taluses regularly possess a talar ridge whose shape and location may suffice to evoke the idea of a beak (see ). The superior view of this human bone, achieved through a 90-degree lateral rotation, lends support to the hypothesis that a human talus inspired the 79M2 jade-maker (Figure 15C). From this perspective, the bone exhibits a broad neck, a stout head, and a wide squarish body reminiscent of the 79M2 bird rendering. The bird’s recessed wing placement against the chest is echoed in the talus, which features a lateral process similarly recessed on part of the bone designated as its ‘body’ in Figure 15C. The two lower osseous tubercules occupy the position representing the bird’s tail on the Niuheliang figurine.

- 2.

- Big Bird

During subsequent excavations conducted at Niuheliang Locality 16, archaeologists found inside tomb M4 a jade plaque positioned underneath the five-thousand-year-old skull of a man who had died in his forties. The 19.5 cm long jade represents a bird introduced as a swan, a phoenix, or a heavenly bird (; ). The creature displays a plumaged profile reduced to a semi-circular body and a proportionately large beak and head (Figure 16A). The avian figure is in a resting position (its head faces backward), but its open eye preempts concluding that it is asleep. An unusual combination of physical features challenges species identification. The figure has an elongated neck, a thick, long, downward curving beak, a prominent nostril operculum-like bulge, and a large circular eye from which a wide wedge-shaped extension projects. Without this prominent appendage crowning the eye and extending toward the neck, the creature could pass for a swan or a bird of prey. Its peculiar characteristics perhaps belonged to an extinct avian species observable in the Hongshan environment.

Figure 16.

Endocranial osseo-morphology as source of inspiration for the phoenix jade plaque (Source: (A) LB and SLB on Procreate; (B) photographs by the author; and (C) Gray’s Anatomy of the Human Body, 1918; public domain).

Considering the jade’s position underneath the deceased’s skull, we nevertheless may entertain the possibility of a link between the artifact and skull osteomorphology. Indeed, it may well be that the image-maker paid close attention to a human endocranial cavity. A skull’s inner walls present features that, through pareidolia, may conjure the mental image of a bird. In particular, the medial view of a temporal bone evokes an avian head seen in profile (Figure 16B). Remarkably, the skull image shares with the jade bird the unusual aggregate of physical features noted earlier. This resonance alone may have conjured in the jade-maker’s mind the image of a bird and sufficed to inspire the jade. However, other morphological factors may have played an additional part. A human endocranial cavity exhibits surface patterns that could lead to the perception of plumage (Figure 16C). The jade-maker likely noticed that blood vessel marks looked like feathers. The brain and its envelope (the outer meningeal sheet called dura matter) leave notable imprints on their bony, protective surroundings. Part of the complex craniovascular system, middle meningeal vessels traverse the dura matter endosteal layer. As the brain cortex exerts pressure on these vessels, their traces are imprinted onto the endocranial wall (). Physical factors, ranging from blood pressure to vessel size, affect the dimensions of these imprints, and evidence shows that they tend to fade through adulthood. The middle meningeal artery imprint generally starts at the base of the skull near the temporal bone and extends upward on the parietal bone toward the back of the skull. The artery stem generally divides into three branches (bregmatic, obelic, and lambdoidal), out of which smaller veins may branch, resulting in variable endocranial imprints described as pseudo-fractal (). While this classification may not apply to the jade bird plumage pattern, the latter still results from three primary sunken lines whose main orientation corresponds to that of bregmatic, obelic, and lambdoidal branches visible on a temporal and its adjacent parietal bone (Figure 16C).

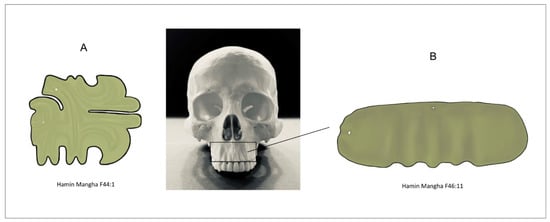

5.5. Fanged Beast Faces (有齿兽面)

5.5.1. Overview

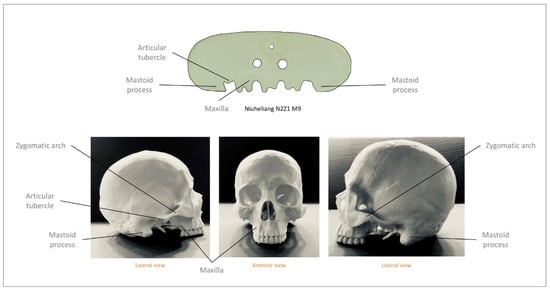

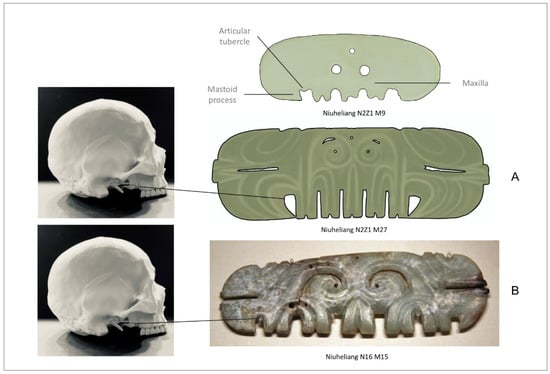

Another significant category in the Hongshan jade repertoire encompasses plaques deemed to represent the face of a fanged animal or a monster. The abstracted form jade-makers gave to these represented entities has challenged any secure identification. An array of interpretations has linked the form to a person undergoing a shamanic trance, a bird, a phoenix, a dragon, a pig-dragon, the taotie, or a tiger. The excavators of the Niuheliang sites classify them as “hooked-cloud” shaped objects ().

This study focuses on pieces scientifically unearthed from Hongshan tombs, a list thus limited to artifacts recovered from Localities 2 and 16 at Niuheliang. The objects range in length from 6.2 cm to the 28.6 cm plaque discovered near the deceased’s head inside tomb N2Z1 M27 (Figure 17).27 The plaques appear to represent not a fanged creature but rather part of a toothless human skull. Here again, Hongshan jade-makers faced challenges from the availability and size of raw jade, which presumably rarely matches the volume of human skulls. Any attempt at size approximation—which they appear to have sought in other osseous representations—required creative solutions. To reduce the positive space taken up by the represented forms, slabs once again proved economical for craftsmen willing to conflate different vantage points to convey their models’ three-dimensionality. As for the equally complex midsection skeletal forms, representing parts of neuro-cranial and facial bones on flat jade slabs demanded conceptual simplifications. Jade-makers reduced forms and came up with a set of standards observed on the Niuheliang artifacts. Each plaque represents the cranium as a compressed entity.

Figure 17.

Partial ground plan of tomb N2Z1 M27 at Niuheliang with jade plaque in situ (Source: SLB on Procreate).

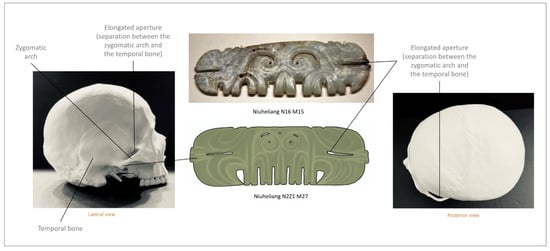

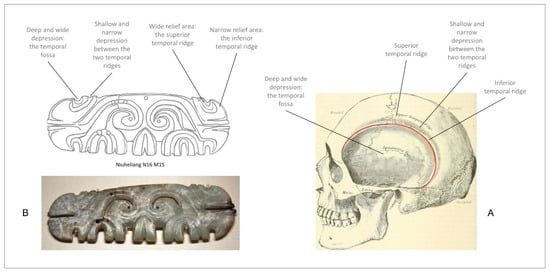

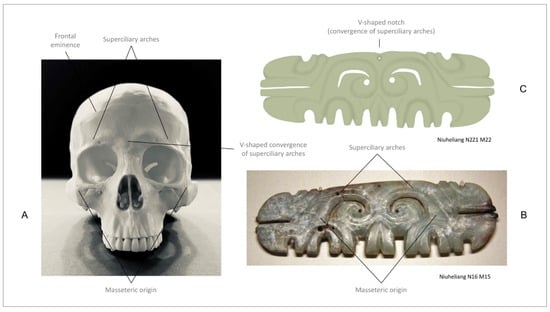

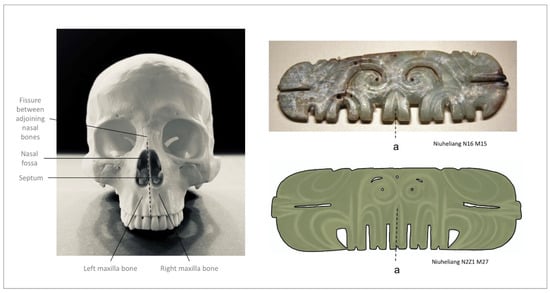

5.5.2. Representational Conventions at Niuheliang

A comparative analysis will demonstrate how the jades represent the osseous structure near which excavators found the 28.6 cm long specimen when they opened N2Z1 M27. The examination will show that the renderings exhibit formal variations resulting from the differentiated reproduction of anatomic details. The human skull replica used for comparative purposes was cast from a skeleton in modern China. Its features are specific to a single, modern individual and, thus, cannot represent all Hongshan community members. A study of skulls found inside graves at Niuheliang concluded that Hongshan people generally shared wide zygomatic bones, a broad and flat face, a narrow nasal aperture, and jaws and orbits of average size. Furthermore, occipital bone deformation observed at both sites on some skulls resulted in flattened posterior surfaces, a cranio-morphologic trait that tends to shorten cranial length (anterior to posterior) and increase facial flatness and width.28 Such characteristics are consistent with the appearance of clay and stone head renderings found at Hongshan sites.