Abstract

The church of Saint Mamas is a small, domed structure that lies close to Menetes village in Karpathos. It preserves most of its painted decoration, consisting of the scene of the Ascension of Christ on the dome and saintly figures on the rest of the surfaces. A dedicatory inscription, read here for the first time, dates the frescoes to 1312/3 and places them in the broader context of precisely dated monuments. Certain features of the iconographic program, such as the presence of healer saints (Panteleemon and Kyprianos) but mostly of the officiating Pope Sylvester and the passage used in the codex of Christ Pantocrator on the apse of the altar, lead us to interesting conclusions concerning, among other things, the perception of anti-Latin propaganda in the islands of the South Aegean. Also, the stylistic affinities between the art of Karpathos and Crete corroborate the diachronic interrelations between the two islands. The church of Saint Mamas is an exceptional example and one of the few Byzantine-decorated monuments that survive on the island.

1. The Historical Background

Karpathos, the second-largest island of the Dodecanese group in the southeastern Aegean Sea, has always been a stop of north–south and east–west maritime routes since ancient times. Especially in the Byzantine era, Karpathos served the route linking Alexandria and other Egyptian harbors with Constantinople and the Black Sea, along the coastline of Asia Minor1. In the 11th century, when the Byzantines were beset by the Turks in the east and the Normans in the west, the Dodecanese islands played a very important role in the defense of the empire. The Byzantine navy had stations at Rhodes or Karpathos since both islands had naval bases (Ahrweiler 1966, pp. 225, 345).

At the end of the 13th and in the first decades of the next century, the situation in the eastern Mediterranean and particularly in the Aegean was turbulent, with pirates constantly attacking coastal settlements (Maltezou 2019, p. 229). The expansion of the Venetians and other Latins into the Aegean also affected the island of Karpathos, and the political situation became uncertain. Latins and Turks were active in the region, with Crete as a major target since 1210.

Close relations between Karpathos and Crete are attested since antiquity. In the Middle Ages, there are certain curious references about Crete importing wheat from islands, including Karpathos (Thiriet 1959, pp. 274–75, 327). In any case, the size of the island and its relatively small productive capacity, alongside possible population growth, necessarily led to imports of products from neighboring Crete2. Karpathos remained under Byzantine rule until 1301, when the noble Andrea Cornaro was already planning to conquer the island for himself and, if he succeeded, to become a vassal of the emperor. It seems that the island was finally occupied, together with Kassos and Saria3, before 1309 by Cornaro, who succeeded the Genoese. Venice, at war with Byzantium since 1296, effectively encouraged its citizens and other dependents to occupy the Aegean islands. Meanwhile, after the repeated attacks of the 13th century, Karpathos was devastated by Turkomans in 1302 or 13034. From 1306, the Hospitallers were busy conquering Rhodes and the neighboring islands; a few years later, in 1313, taking advantage of Cornaro’s absence, they seized Karpathos. Cornaro appealed to Venice, whose intervention indicates that the island was already considered a Venetian protectorate and, as such, was included in all subsequent treaties with the Turks (Zachariadou 1983, p. 95). Karpathos and Kassos became objects of contention between Venice and the Hospital, in the shadow of the pivotal claim on Kos5. In 1316, after three years of negotiations, during which the Hospitallers accepted the arbitration of Venice, the Venetians regained sovereignty over the island, as Cornaro became a feudatory of Crete6.

2. The Church of Saint Mamas

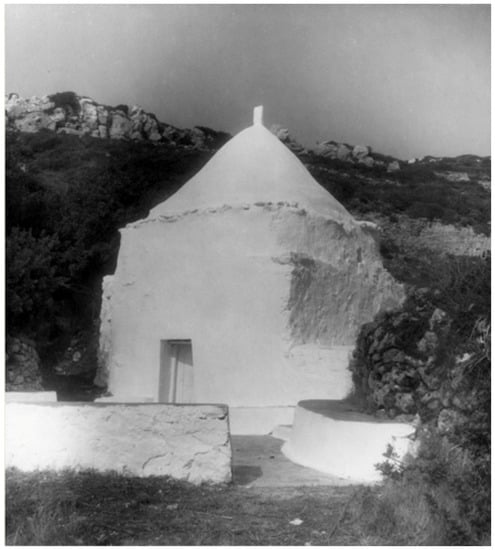

The chapel of Saint Mamas stands not far from the village of Menetes in southern Karpathos, on a slope of the verdant area of Exeles7 (Figure 1). It is a small building measuring 2.66 × 2.68 m. Today, the building might be whitewashed, but that does not hamper us from identifying that it has been built with rubble masonry. The church’s plan is square, sporting a conical dome and an inscribed eastern arch. The square interior chamber is articulated by a small square niche on the north wall and an eastern conch, eccentrically placed. The latter has a two-stepped built-in structure that today is used for the altar. The conical dome is built with the corbelling technique and rests on a very low-rising octagonal drum. The external octagonal pseudo-drum (Figure 2) has been inscribed onto the square of the building, leaving four segments of its circular perimeter to project at the corners of the square. These have been interpreted as early manifestations of squinches, although it seems that, presumably, that is not the case. Through these squinch-like segments, the dome is inscribed to the building and its thrusts are transferred to the walls. Four tiny windows pierce the base of the dome and light the interior. The portal at the west is built with simple jambs and a flat arch formed by, apparently, a monolithic lintel.

Figure 1.

Karpathos, Exeles, Saint Mamas.

Figure 2.

Saint Mamas, the conical dome.

Structurally, the building conforms to the practicalities of the island; the abundance of dolomitic stone dictated the rubble masonry with which it has been built. Whether or not, prior to its consecration to a church, it was an Islamic mesjit it is an interesting premise that accords with the eccentrically built conch and the similar findings from Crete. Architecturally, the conical domes have been present in the wider Aegean area since the 7th century, e.g., the building attached to the south in the Drossiani complex, or the Vangelistra church of the 8th/9th c. at ancient Minoa in Amorgos until the late 14th century in Chios (Drandakis 1988, pp. 20–22; Marangou 2002, pp. 316–19, pl. 220a; Vassi 2012, pp. 67–68, 160–62, 165, 258–70). That their presence owes its reception and appropriation from cultural exchanges with the Arabs would look highly probable, but it is worth noting that the corbelling technique itself was part of a vernacular building tradition practiced in the Aegean, as the insular cases of Saria (Deligiannakis and Karabatsos 2017) and Halki (Sigala 2018, pp. 356–57) attest to. The restoration of the building in the 1960s might have taken away important information from the masonry of the church that could corroborate an early dating for the edifice, but that does not negate the fact that the painting consisted of part of a program to update the building and render it appropriate for Orthodox worship (Sigala 2018, p. 356, with the literature).

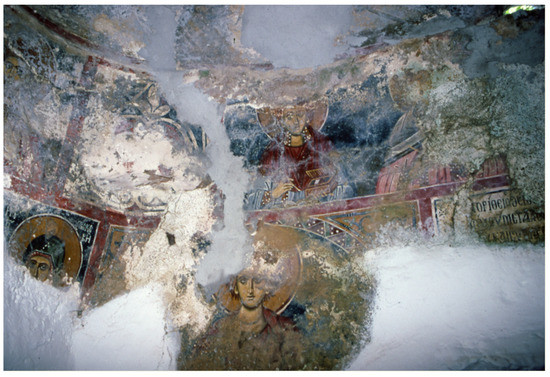

3. The Painted Decoration

The chapel preserves most of its painted decoration, but in a rather bad condition and partly covered by plaster. The iconographic program, due to its dimensions, is compact. Christ Pantocrator is depicted in the semidome of the apse and the Ascension in the dome. Officiating bishops flank the apse: Saint Athanasius on the left and Saint Eleutherius on the right. Above them, at the upper left, is the damaged bust of a male saint. On the south wall, close to Eleutherius, stands Saint Nicholas, and next to him the damaged figure of another officiating bishop with dark hair. Above Saint Nicholas is the bust of Saint Cyprian. On the west wall, Saint Paraskevi stands on the right close to the door. Above her are an unidentified female saint on the left and Theodore Stratelates on the right. On the north wall, the lower tier is occupied by the patron saint, Mamas, to the left, and Saint Sylvester to the right, with the dedicatory inscription between them; above Sylvester are the busts of two medical saints; a third, close to Athanasius, is seriously damaged. The four pendentives are decorated with white floral swirls.

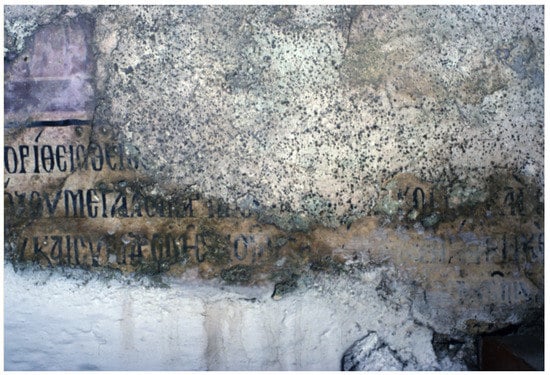

On the north wall, next to the image of the patron Saint Mamas, the dedicatory inscription (Figure 3) in four lines with capital letters on a white background reads:

Figure 3.

The dedicatory inscription.

ΙҀOΡΊΘΕΙ O ΘΕΊOC……………………………………………………….

(EN)ΔΌΞOΥ ΜΕΓAΛOΜAΡ(C MAMA ΔΙ) ΚΌΠ ΚAῚ (ΞO)

(ΔO)Υ ΚAΙ CΥΝΔΡOΜH͂C ΚOA(N)ṬI(NOY)…………………….ΚỌ

………………………………………....…. Ҁ̣W ΙΝΔ A΄ (6821 = 1312/3)

The holy (chapel) of the Glorious Megalomartyr Mamas was painted by the labor and expenses and contribution of Constantine Ko….. 6821, indiction 11th.

The inscription is badly preserved, with much of it missing and some parts illegible. It informs us that the church of the glorious megalomartys Mamas8 (his name is now missing, but he is depicted in a niche next to the inscription) was decorated with the labor9, expenses, and help of Constantine. The part of the text that follows is missing, but luckily, at the very end, one reads the year 6821 = 1312/3 and the 11th indiction, which precisely dates the painted decoration.

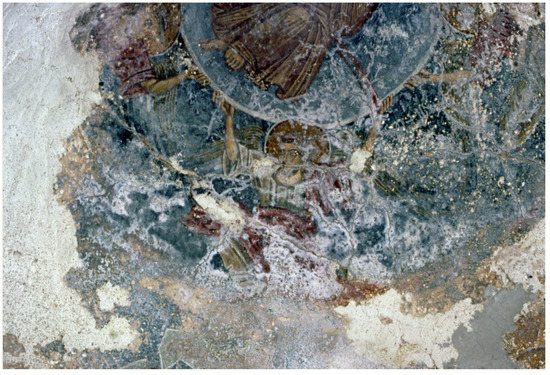

The Ascension of Christ occupies most of the vault (Figure 4). In the center, Jesus is seated inside a round, light blue mandorla, lifted by four angels. He is blessing with his right hand and in his left is holding a tied scroll. On either side of the mandorla, between the pairs of the angels’ hands, the inscription: H AΝA/Λ̣HΨΙC. The Virgin Mary and the apostles are witnessing the scene.

Figure 4.

Dome, the Ascension.

The apse is occupied by the monumental figure of Christ Pantocrator (Figure 5). The scroll in his hand reads Ζῶν ἄρτος ὁ/(ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ κα)ταβ(ὰς)10 (The Living Bread that descended from Heaven). This Eucharistic inscription is known from the Hermeneia of Fournas (Papadopoulos Kerameus 1909, pp. 228, 279), but this version, with the biblical verse slightly changed, appears unique in monumental art11. It is attested only on the panagiarion of Andreas Ritzos at Patmos (Chatzidakis 1977, pp. 64–65, pl. 88) and, later, in post-Byzantine times, the Christ in the Melismos is occasionally inscribed «Ζωηφόρος άρτος».12 On either side of his head, the sigla (XC) are inscribed in large red medallions. Such abbreviations within usually red roundels appeared in the 12th century but continued until the Late Byzantine period (Papamastorakis 2001, p. 66), such as, for example, in the second layer of the painted decoration of the church of the Virgin at Archatos (1285) on Naxos (Konstantellou 2019, p. 207, fig. 264) and several other examples from Crete, until as far as the beginning of the 16th century13. The lower zone consists of saints’ busts.

Figure 5.

Apse, Christ Pantokrator.

On the south wall, an elderly officiating bishop with a white beard holds a scroll with a six-lined faded inscription, (META TOΥΤΩΝ ΚAΙ HΜΕΙC)/ΤΩΝ ΜA[ΚA]/ΡΊΩΝ ΔΥ[ΝA]/ΜΕΩΝ (ΔΕ)/ΠOΤṬ(A ΦΙΛA)/(Ν)(ΩΠΕ)14. Only traces of the last letters of his hagionym survive, but his iconography and the text plausibly identify him with Saint Nicholas (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

South wall, Saint Nicholas.

On the west wall, a female saint is partly preserved (Figure 7). She wears a light green maphorion and holds a white glass bottle. No eponym has survived. The iconography, with the simple, green maphorion and bottle, recalls Saint Anastasia Pharmakolytria in the narthex of the church of Panagia Asinou in Cyprus, dating from the late 13th century (Kalopissi-Verti 2008, pp. 115–22). The depiction of Saint Anastasia is suited to the healing character of the church as well as its funerary context.

Figure 7.

West wall, female saint.

Saint Theodore Stratelates, inscribed Ọ AΓỊO (ΘΕOΔΩΡOC) O ҀΡAΤΙ(AΤHC), is portrayed in the usual manner, as a young man with brown, curly hair and a short beard. In his right hand, he holds the martyr’s cross and raises his left palm (Figure 8). Saint Theodore Stratelates15 is highly venerated on Karpathos, since his only known iconographic cycle, dating from 1399, is found in his church at Aperi, not far from Menetes (Mastrochristos 2011).

Figure 8.

West wall, Saint Theodore Stratelates.

Saint Eleutherius, (O AΓΙOC ΕΛΕΥ)ΘΈΡΙ, is portrayed with dark hair and with dark crosses on a whitish phelonion (Figure 9). The saint is often depicted behind the altar, either among the officiating bishops or among the deacons.

Figure 9.

Saint Eleutherius.

On the lower zone of the west wall, north side, is Saint Paraskevi H A/ΓΊ/Ạ ΠAΡACΚΕ/B, in her usual representation with a dark blue maphorion16 (Figure 10). Only part of her head is visible under the layers of plaster. The association of Saint Paraskevi with the homonymous day of Holy Week (Friday), i.e., the day of the Passion, was one of the reasons that she was often represented in the murals of churches, particularly those of funerary function (Gerstel 2015, p. 66). She is also closely associated with the cult of the Holy Cross (Mouriki 1993, pp. 253–54; Kaffenberger et al. 2021, pp. 347–48). For this reason, she is usually depicted close to Saint Kyriake17. Above her, Theodore Stratelates can be seen. She was also known as an intercessor to God on behalf of shepherds and farmers (Konstantellou 2019, p. 255, with the literature). The saint was very popular in Byzantium and the south of Italy (Andronikou 2017, pp. 11–13).

Figure 10.

West wall, Saint Paraskevi.

Saint Athanasius’ image is only identified by its accompanying inscription (O AΓΙOC) AΘAΝA/CIO; only part of his head and halo has survived18.

The image of the patron Saint Mamas19 is framed by a painted proskynetarion20 (Figure 11). The young saint is depicted with tousled hair and a red mantle, holding the martyr’s cross in his right hand. To the right of his head, part of the inscription is preserved: MA/MA. The lower parts of the image are whitewashed.

Figure 11.

North wall, Saint Mamas.

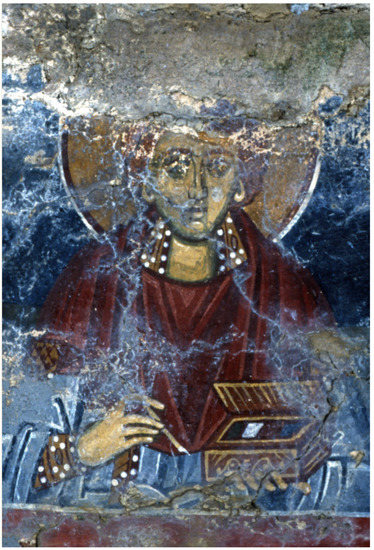

Two healing saints are depicted next to each other. The first is young, with curly hair, holding a casket on his left and a spoon that looks like a lance to his right21 (Figure 12). On the right is part of his hagionym, (ΠA)ṆTE(ΕHΜΩΝ). Saint Panteleemon, a doctor from Nicomedia22, was highly venerated in the eastern parts of the Byzantine Empire, particularly in Rhodes and the nearby islands23. Next to him, another saint with a pink chiton and a light blue cloak also holds a spoon and casket, but is heavily damaged and cannot be identified. He might be one of the two most important Anargyroi, Saint Kosmas or Damian (Kyriakos 2018), or Saint Hermolaus.

Figure 12.

North wall, Saint Panteleemon.

The bust of a grey-haired bishop with a medium-sized beard is inscribed O A/ΓΙ/OC Κ(ΠΡΙ)/AΝO, Saint Cyprian of Antioch (Ramseger n.d.; Endrich 1994; Galavaris 1969, pp. 103–8) (Figure 13). In the Hermeneia, Saint Cyprian is described as young, with curly hair and a long, forked beard (Papadopoulos Kerameus 1909, pp. 156, 194, 269). This type is followed, for example, at the church of the Virgin at Valsamonero in Crete, and because of that, the young version of the saint is identified with the bishop of Carthage (Bormpoudaki 2020, p. 78, pl. 8α). However, at St Mamas, we have Saint Cyprian of Antioch, depicted as an elderly bishop, as in the Refectory of the Monastery of Saint John the Theologian on Patmos (late 12th century) (Kollias 1986, fig. 32). He is also shown as elderly with a long beard in the bema of the Panagia tou Arakos at Lagoudera, Cyprus (1192) (Konstantinidi 2018, p. 70, pl. 32). A close parallel to ours is the depiction of Cyprian in the church of Saint John the Evangelist at Kato Valsamonero, Rethymnon (c. 1400) (Spatharakis 1999, pp. 125–26, 328, fig. 134). The saint is also occasionally portrayed in the narthex, as in the church of the Virgin Mary in Kapetaniana, Monofatsi, Crete (1401/2) (Spatharakis 2001, p. 159), or among the officiating bishops, as in the church of Saint John the Evangelist at Kroustas Merabellou at Lasithi, Crete (1347/8) (Spatharakis 2001, p. 94).

Figure 13.

South wall, Saint Cyprian of Antioch.

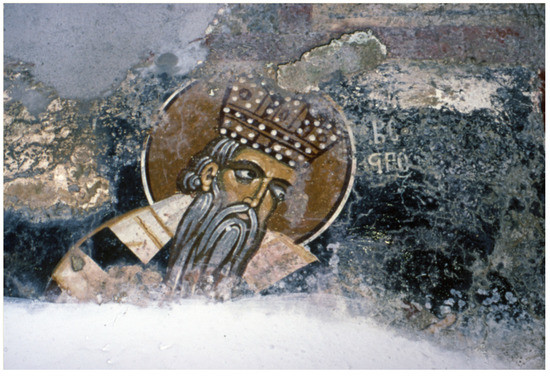

The officiating Saint Sylvester, Pope of Rome, has a long, grey beard and is wearing a phelonion with dark crosses and an episcopal tiara (Figure 14). To the right is the inscription C/ΒΕ/ҀΡO/. More about the monuments where the image of the saint is attested will follow in the next chapter.

Figure 14.

North wall, Saint Sylvester.

4. Observations on the Iconography

The iconographic program of the church of Saint Mamas suits the dimensions of the monument and the configuration of a small, domed church. Only one scene, the Ascension, is chosen—indeed, no more could have fit in such a small edifice. The Christ Pantocrator painted in the conch of the apse is a rather regular feature in churches of the Byzantine periphery. Of course, its eschatological character is far more prominent in burial chapels; otherwise, the multivalent significance of the scene renders it appropriate for wider use. The Ascension is typically painted on the vault of the bema and placed in front of the apse; the scene is vested with rich symbolism and theological connotations that refer to the Last Judgement. Saint Mamas, to whom the church is dedicated, was a healer and protector of agriculture. The majority of the saints in the church are healers (Figure 15), the most prominent of these being Saint Panteleemon, the par excellence physician saint, and the rarely occurring Cyprian. This particular group of saints was, in all likelihood, chosen as healers due to the endemic character of certain diseases, whose frequent appearance was a recurrent threat to the population of the islands during the Middle Ages.

Figure 15.

West wall, the healing saints Paraskevi and Mamas.

Out of the group of holy women, the pair of female saints Paraskevi and Kyriake is a typical case of saints with twofold significance, as is almost always the case in the saintly figures of this edifice. Mamas, for example, protector of husbandry and agriculture, is dominant in the program but so is Kyriake, protector of the harvest. Also, the presence of the very popular military saint Theodore Stratelates may be associated with his reputation for healing.

Alongside the soteriological and eschatological character, the iconographic program of the church is full of choices that support the Orthodox dogma. The text in the gospel held by Christ and the presence of Pope Sylvester, whose discussion follows, proclaim the Orthodox faith and reflect the theological concerns of the donor in a period of turbulence for the islands in the south Aegean.

5. Why Saint Sylvester?

The depiction of Pope Sylvester in the church decoration, a leading figure in the iconography of Roman popes in Byzantine art, deserves special comment. Sylvester was born in Rome and was pope between 314 and 335, succeeding Miltiades. He is honored as a saint by both the Latin and Orthodox rites and commemorated on 2 January by the patriarchate of Constantinople (Duchesne 1955, pp. 170–201; Delehaye 1902, pp. 365–66; Halkin 1957, pp. 239–42; Eustratiades 2010, p. 424). Accounts of his life vacillate between myth and reality. In the fictional account of his life, Actus Silvestri, written in the 4th-5th century, he is said to have cured of leprosy and then baptized Constantine the Great24. John Malalas, in the 6th century, attributed Constantine’s baptism to Saint Sylvester (Malalas 2000). In later texts, he also appears as a resolver of various doctrinal issues. After the 9th century, the influence of a text on the subject of the spurious Donation of Constantine was a stimulus to his reputation: according to this, the emperor granted Sylvester and his successor popes supremacy and privileges over the Eastern Church, with the secular authority subordinate to the ecclesiastical one (see Jenkins and Kitzinger 1967, p. 237, n. 10; Walter 1970b, pp. 171–72). This narrative, possibly introduced in Constantinople through the emissaries of Pope Leo IX in 1053 (Bara 2017, p. 113), reached the height of its popularity in the period after 1204, when it became more widely known in ecclesiastical circles. Its appeal increased in times of decline, with its reference to Saint Constantine the Great, founder of the Byzantine capital. The oldest Greek manuscripts narrating the episode date to the 13th century. As has been observed, this anti-Byzantine forgery had a deep effect on the Orthodox literature in the fields of law and ritual (Angelov 2009). It was occasionally used as a vehicle for ecclesiastical resentment (Bara 2017) against the political hierarchy, part of the continuing argument developed for the primacy of the church of Rome in the Latin state of Constantinople until 1261 (Angelov 2009, pp. 118–19). In particular, closer interaction, hostile or otherwise, occurred between Latin and Orthodox scholars on the topic, as did the growing popularity of the topic among ecclesiastical circles. The conflict between the churches flared up after the second Council of Lyon (1274), in which loyalty to the pope and acceptance of the Latin rite had been professed. Latin propaganda on other issues, such as the issue of unleavened bread25, used the Donation of Constantine as an argument for the supremacy of the Church of Rome. The aftermath of the Council (Fougias 1994, pp. 281–93) deeply divided the empire, as the security objective that motivated the emperor was not attained. Regarding Sylvester’s rank in the ecclesiastical order, it is worth noting that immediately after the recapture of Constantinople by the Byzantines in 1261, relics of the pope were displayed in the treasury of St Sophia. According to an inventory of 1397 compiled by order of patriarch Matthew I, the relics were supposedly kept in a monastery near St Sophia (Guran 2007, pp. 138–39). The increased prominence of Sylvester should definitely be taken into account when researching the relative frequency of his appearance in 14th-century monuments.

In 1312/3, the date of the decoration of the Karpathos church, the emperor was Andronicus II Palaiologus. The Uniate policies of the previous emperor, Michael VIII, had died with him. After his accession to the throne in 1282, Andronicus II imprisoned the uniate patriarch John Beccus and pressed on with the denunciation of the Council of Lyon (1274). The restoration of Orthodox views, after a period of crisis within the Orthodox church around the Trinitarian doctrine, was accompanied in 1310 by the resolution of the Arsenite schism with the victory of the anti-Uniate Arsenites, enemies of Michael VIII and followers of strict church discipline26. Regarding the Donation of Constantine and its place in popular consciousness, it is no coincidence that in patriarch Athanasius’ letter of resignation in 1309, Constantine’s relationship with Pope Sylvester is used as a powerful justification for the position and privileges he had enjoyed on the patriarchal throne. A little later, Matthaios Vlastaris, in his preface to the Syntagma, a compilation of ecclesiastical regulations, cites Constantine and Sylvester as a model relationship, in setting aside ideological and political ambition27. In the end, the Donation was totally rejected by the Orthodox church as a forgery between 1433 and 146028.

Pre-schismatic popes, such as Saint Sylvester, even if not particularly frequent, are not absent from the iconographic programs of Byzantine churches29. However, illustrated lives of the saint associated with Constantine are to be found only in Western art (Peers 2000, p. 287, n. 56; Vassilaki 1987, pp. 75–76).

Preserved in the church of SS Sylvester and Martin of Tours in Rome (509–514) is one of his oldest depictions (Wilpert 1916, pl. 96). The baptism of Constantine the Great by Sylvester was depicted in St Polyeuktos at Constantinople (6th century) (Mango and Ševčenko 1961, p. 245, n. 14; Milner 1994, pp. 73–81). In Santa Maria Antiqua (705/6), he is displayed in full length (Maskarinec 2018, pl. 16).

He is then included in the Menologion of Basil (Il Menologio 1907, p. 291), in two miniatures of the Smyrna manuscript of Physiologus30, and in eight scenes of the Psalter Vaticanus Graecus 75231. In the latter, only the baptism of Constantine is identifiable; in the other scenes, Sylvester’s unexpected presence has yet to be interpreted. Among portable works, mention should be made of the third leaf of the hexaptych of the Sinai monastery (second half of the 11th century) (Galavaris 2009, p. 77, fig. 7) and a partially preserved cross in the Dumbarton Oaks collection, supposed to have belonged to patriarch Michael I Cerularius (1043–1058). Constantine the Great is depicted being blessed by Sylvester, who holds icons of Peter and Paul.32 He also appears in various menologia scenes33.

He is also found at the diaconicon of the katholikon of Hosios Loukas (second quarter of the 11th century) (Diehl 1889, p. 57; Diez and Demus 1931, fig. 30; Vitaliotis 2003, p. 145, fig. 4), of St Sophia, Ochrid (1052–1056) (Ðurić 1963a, pp. 32–33; Acheimastou-Potamianou 1994, pp. 214–15, fig. 23; Todić 2008, p. 108, fig. 2). The saint also appearson the inside of the arch in front of the prothesis in the katholikon of the Daphni monastery (c. 1100) (Lampakis 1899, p. 81; Diez and Demus 1931, fig. 77; Panayotidi 2019, p. 200, fig. 8), in the central apse in Monreale (1170–1180) (Brodbeck 2010, pp. 722–25; Abulafia and Naro 2013, p. 313), in the diaconicon of the katholikon of the Kosmosoteira monastery (second half of the 12th c.) (Skawran 1982, p. 166; Konstantinidi 1989, pp. 305–6, fig. 2) and in the church of the Transfiguration of at Chortiatis (end of the 12th c.) (Tsigaridas 2021, pp. 127–28).

He is also depicted in the apses at Ani (1215–1225) and Achtala (1205–1213) (Ataç 2022, figs 5, 7.7), in the diaconicon of St John “Kalyvitis’ at Psachna in Euboea (1245) (Emmanouel 1991, pp. 138, 141, fig. 6), in the prothesis at Sopoćani (1263–1268) (Altripp 1998, p. 173; Okunev 1929, pp. 120 sqq.; Millet and Frolow 1957, pl. 1 (3–4), 2–3, 4 (4), 98 (1); Ðurić 1963b, pp. 54, 112, figs I–II; Todić 2002, pp. 465–74, figs 2–3), on the south wall of the sanctuary of Porta-Panagia at Trikala (1283–1289) (Tsitouridou 1981, pp. 868, 872, figs 3, 5), at Christos of Veroia (Pelekanidis 1994, fig. 71), in the diaconicon of St. Nicholas Orphanos (1310–1320) (Xyngopoulos 1964, fig. 83; Tsitouridou 1978, p. 35, fig. 6; Tsigaridas 2021, p. 364), and on the side walls of the Holy Altar of the katholicon of Vatopedi Monastery (1311/2) (Toutos and Fousteris 2010, p. 121); as officiating bishop in the Annunciation at Karan (1340–1342) (Kašanin 1926–1927, p. 187, pl. 11, 39, 40; Konstantinidi 2008, pp. 132, 136, 197, fig. 160) and at Prokupljie (1350) (Tasić 1967, p. 129 sqq, pl. 2–3) and on the south wall of the Old Metropolis of Edessa (shortly before 1385 or 1389) (Tsigaridas 2021, p. 120, figs 75, 76). He flanks Constantine the Great in the scene of the First Ecumenical Council in the narthex of the katholicon of the Pantokrator Monastery in Dečani (Walter 1970a, p. 273; Petković and Bosković 1941, fig. CCII.3). He is also represented at Staro Nagoričino (1317) (Millet and Frolow 1957, III, pl. 72.2), in the King’s church in Studenica (1314) (Miljković-Pepek 1967, fig. XCI), at Prophet Elias in Žiča (1317) (see Karamperidou 2009, p. 87, n. 434), and in the north pastophorion in St Nicholas at Curtea de Argeş (14th c.)34. He is officiating in the Holy Trinity Resava/Manasija (1407/8–1418)35 in the (detached frescoes) of St Photeine at Veroia (14th–15th c.) and in the Panagia Vrestenitissa (c. 1400) (Drandakis 1979, p. 170, fig. 13). In Cyprus, the saint occurs at St Nicholas of the Roof at Kakopetria, Cyprus (Stylianou and Stylianou 1997, p. 71) (second half of the 14th c.), and his bust is included in the representation of the Seventy Apostles in St Heraklidios at Kalopanagiotis (15th c.) (Papageorgiou 2007, p. 31, fig. 22).

His depictions in the Byzantine churches of Crete make up a separate chapter of particular importance in the present discussion. In a medallion in the barrel vault of the sanctuary of the Panagia at Prasses, Rethymno (c. 1300) (Spatharakis 1999, pp. 159, 161), on the north wall of the sanctuary of the Panagia Faneromeni at Hagios Ioannis, Mylopotamos (c. 1300) (Giapitsoglou 2011, p. 50; Spatharakis 2010, pp. 21, 23, 39, fig. 18; Schmidt 2020, pp. 28–29), as a bust on the barrel vault of the sanctuary in St Michael at Kavalariana, Selinos (1327/8)36, and in St Constantine at Kritsa (1354/5), he baptizes Constantine in the first of the three scenes of his vita37. In the Panagia at Palia Roumata, Kissamos, Chania (1359/60), he is depicted on the north wall of the sanctuary (Spatharakis 2001, pp. 73, 108), while in the sanctuary of the Eisodia at Sklaverochori Pediada (end of the 14th c), he is depicted as a bust on a parapet wall, wearing a papal tiara (Borboudakis 1991, fig. 188α).

In these murals, which are the most interesting due to the proximity of Crete to Karpathos, it seems that the iconographic type of saint is not always the same38. For example, in Faneromeni he appears tonsured with short black hair and a beard. In any case, his presence in St Mamas on Karpathos seems to be a unicum in the islands during the Byzantine era.

As we have seen, he is frequently found among officiating bishops. The depiction of the popes of Rome usually in the prothesis could be justified, as the Melismos takes place there. This statement marks a fundamental difference between the Orthodox and the Latins, with the use of unleavened bread by the Westerners in the Eucharist (Ghioles 2009, pp. 25–26). It should be noted, however, that Sylvester is represented at least as often in the diaconicon.

His depictions proliferate in post-Byzantine monuments, as an echo of his association with the Donation of Constantine. For example, in St Stephen at Nessebar (1598/9) (Bacheva 2022, figs 1a, 1b), a full-length Sylvester stands next to Constantine, from whose side—it should be noted—Saint Helen is missing. His depiction with the triregnum, the papal tiara, links him to Western iconography. In Bãlimeşti, the baptism of Constantine is depicted in the iconographical circle of the Archangel Michael39. The anti-Latin discourse, which makes use of papal emblematic portraits in response to Catholic propaganda, was also found in post-Byzantine churches in Moldova (Bedros 2019, pp. 1–18). In other cases, however, there are features arguing in favor of a Latin influence: in a mural of 1709/10, it is argued that his inclusion expresses a pro-union spirit (Acheimastou-Potamianou 1997, pp. 178–83).

Statistically, Roman popes were not a popular choice throughout the Middle and Late Byzantine period (Walter 1982, pp. 220–22). Sylvester was chosen because of his dominant position in his relations with Emperor Constantine and his leading role compared with other popes. His depiction in Byzantine art seems to follow certain rules: his presence can be read in some cases as a demonstration of the ecumenical spirit of Orthodoxy or from the viewpoint of the superiority of ecclesiastical over secular power. We should not overlook it as a visual expression of symphoneia (the fidelity manifested towards the Byzantine heritage) and as a claim to the various approaches to apostolic tradition by local Churches, as the See of Rome never lost its preeminence. Thus, the interpretation of Sylvester’s presence in the monuments is understandable40, probably including particular political dimensions.

Concerning the so-called Michael Cerularius’ cross, the patriarch of Constantinople is said to have ordered a cross in 1057: this was initially identified with the partially preserved specimen in the Dumbarton Collection. In the top fragment and as a principal subject, Saint Constantine is depicted bowing to the icons of Peter and Paul, presented to him by Pope Sylvester41. According to Mango, the conversion of Constantine is implied42. Although the connection of this particular cross to Cerularius has been reasonably disputed43, the implications of the iconographic choices point to a political context related to the conflict about supremacy between the two powers in the empire at the time. Cerularius linked his patriarchate44 to the moral authority of the pope, considered superior, and claimed a dimension for his position close to that of kingship. It should be noted that the scene on the cross, although associated with Constantine the Great, is not included in his pictorial circles in the Eastern world. A related example concerning the contemporary significance of the Donation of Constantine is the slightly later claims of Leo, bishop of Chalcedon (+1094), already mentioned. Cases such as these can be associated with the activity of dissatisfied metropolitans and members of the patriarchal clergy.

In the Smyrna manuscript of the Physiologus, the depictions of Sylvester raise the issues of the prominence of Saint Peter and papal authority (Peers 2000, pp. 288–90) and are convincingly ascribed to contemporary political and theological thought in the milieu of patriarch Cerularius and the emperors (Corrigan 1997, pp. 201–12). In St Sophia at Ohrid, an iconographically important monument, bishops of the First Ecumenical Council, are depicted in the apse45. However, the multitude of church representatives, including those from the See of Rome, reminds us of the role claimed by the diocese of Ohrid after the region was recaptured by the Byzantines. The ritual of the preparation of Holy Communion, and more specifically the use of leavened and crossed bread in the Communion of the Apostles and the Liturgy of Basil the Great, was assigned a doctrinal symbolism. The sponsor of the frescoes, archbishop Leo Chartophylax, was a fierce polemicist against the Latins; he played an active role in the conflict on unleavened bread, which had much to do with the refusal to accept papal sovereignty, an affair that led to a schism between the churches of Constantinople and Rome in 1054.

The desire to highlight the ecumenical character of the Church, threatened by the predatory disposition of the Latins, is dynamically depicted in the Panagia Kosmosoteira, which includes a number of pre-schismatic popes of the See of Rome, among other patriarchs. In general, in 11th- and 12th-century monuments with a strong theological influence, papal portraits often appear representing the plenitude of the apostolic tradition for the Church, as well as a polemical anti-Latin discourse. At Ani and Achtala, Sylvester was chosen by the donors, the Mkhargdzeli family, to portray their loyalty to the pope in their search for Latin support (Ataç 2022, pp. 235–50). At St John Kalyvitis, osmosis with Western elements can be explained by the Latin domination of Euboea (Emmanouel 1991, p. 141). The depiction of the Seventy Apostles, including Sylvester, in St Heraklidios at Kalopanagiotis, an extremely rare subject in the Byzantine era46, was indirectly linked to the Union of Churches (Eliadis 2019, p. 32).

The presence of Sylvester in the northern monuments, mainly those of Serbia and in the Serbian sphere of influence, indirectly highlights the role attributed to him: Constantine the Great became a model for the Slavic monarchy, its leaders claiming the epithet of New Constantine47. This practice spread to Bulgaria and Russia. The depiction of the pope fits into this context by alluding to the desire of the Slavic leadership to align itself with Constantine and those associated with him. This new dimension of the interest in Sylvester by the Serbian dynasty was reflected not only in the monuments in which he was depicted but also in the translation of the work of Matthaios Vlastaris into Serbian (Guran 2007, p. 138). The promotion of the rulers of the Slavs as “new Constantines” accorded with the messages inherent in the depiction of Sylvester48.

In St Constantine at Kritsa, according to Maria Vassilaki (Vassilaki 1987, p. 82), in the baptism of Constantine, Sylvester is replaced by an Orthodox bishop49. In this case, alongside the attempt to appropriate Constantine, through his vitae in the iconographical programs of the Byzantine churches of Crete, the drive to weed out Western elements is marked by the omission of Pope Sylvester from the scene. In contrast, in St Michael at Kavalariana, his presence probably reflects the pro-Western inclination of the donors,50 perhaps a Uniate minority in a conservative region. The depictions of Sylvester in Crete, an island under Venetian rule, deserve a more thorough examination.

In post-Byzantine monuments, a few of which have already been mentioned, the presence of Sylvester, often with other pre-schismatic popes, reflects and emphasizes other parameters, although it is not always clear whether this is due to the unconscious absorption of traits of Western art or signs of pro-Western partisanship. These possibilities will not be considered here, as copying without conscious choice cannot be ruled out.

In conclusion, the frescoes of St Mamas on Karpathos reveal the attitude of the donor and perhaps also the experiences of the painter of the frescoes in relation to the dispute between the Latin and Orthodox churches; it also provides an insight into current political events on the island and in the wider geographical region.

The anti-Latin elements in the iconography of St Mamas are not alone at this time in the Greek-speaking lands. They fit into the context of open challenges by anti-Uniates and anti-Latin Christians, as well as expressions of the opposite, in the iconographic programs of the time51.

In 1281, the donor of St George at Karinia in Mani included the Maccabee martyrs in the decoration: this could be read as a statement of opposition to the Uniate policy of Michael VIII in defense of the Orthodox faith, although his authority was recognized in the donor inscription and the depiction of the Palaeologan eagle emblem in the semicylinder of the bema (Takoumi 2021, pp. 64–65).

In the case of the Panaghia Chrysaphitissa in Lakonia (1289/90) (Albani 2000, pp. 47, 103–4, pl. 13, 18b), the opinion has been expressed that the iconographic program had an anti-Union slant, covertly referring to the controversy of the unleavened bread and emphasizing the doctrinal differences between the two rites: the liturgical lamb is depicted in the middle of the disc with the cross-marked bread instead of the Christ of the Melismos on the altar.

A third case occurs in the Transfiguration at Pyrgi on Euboea (1296). The sequence of Melismos and the Pentecost emphasizes the Orthodox perception regarding the issues that were raised again at the Council of Lyon concerning the filioque and the validity of holy communion with unleavened bread (Konstantinidi 2008, p. 93).

Also, in the Savior at Akoumia, at Hagios Vasileios, Crete (c. 1300), and later in St John at Selli, Rethymnon (1411) (Konstantoudaki-Kitromilidou 2014, pp. 101–2), the rare detail of the appearance of the bust of God the Father in the Baptism, instead of the usual Manus Dei, perhaps to emphasize the emanation of the Holy Spirit from him, is a response to the filioque of the Latins.

6. The Style of the Frescoes

The earliest observations of the style of the frescoes of St Mamas (Katsioti 1996–1997, p. 291) suggested a date of execution of around 1300. This has been confirmed by the correct reading of the inscription. The linearity of the forms and the rendering of the drapery derives from the late Komnenian style, which, after a manner, survived into the 14th century. For example, the Christ of the Ascension (Figure 16) has the drapery divided into layers consisting of linear segments, a characteristic found in monuments around and after the turn of the century52. The harsh, prismatic folds (Figure 17 and Figure 18) can be compared to the frescoes (Spatharakis 2015, p. 34; Konstantoudaki-Kitromilidou 2014, fig. 13) of the Savior at Akoumia, Hagios Vasileios, Crete, and specifically to the depiction of the Betrayal of Judas, or, again, in the Christ from the Ascension in the Panagia of Kissos at Hagios Vasileios (c. 1315) (Spatharakis 2015, p. 149; Fraidaki 2014, fig. 4). Also, the spindle-shaped ends of the garments (Figure 19 and Figure 20) are found throughout Greece in conservative monuments, such as in Crete at St George, Lyttos, (1321)53, St. Irene, Mourne, Hagios Vasileios (1320–1330)54, St. Constantine, Kritsa (1354/5)55, but also in Taxiarches at Desfina (1332) (Sotiriou 1962–1963, pl. 49).

Figure 16.

The Christ of the Ascension.

Figure 17.

The Ascension, the apostles (detail).

Figure 18.

The Ascension, the Virgin (detail).

Figure 19.

The Ascension, the apostles (detail).

Figure 20.

The Ascension, an apostle (detail).

At the same time, the attempt to introduce new trends must be acknowledged, such as the application of the «volume style» in the rendering of the figures and their spatial distribution (Figure 21 and Figure 22), as seen in the progressive monuments of the late 13th century. The arrangement of the Ascension across the dome, a unicum in the Dodecanese, reveals a painter who exploits available space while keeping to the conventions of the composition. He interferes with the proportions of the figures to achieve a certain fluidity but is hesitant and clumsy in the rendering of the volumes. It is worth noting the disproportionately large limbs and wide shoulders of the figures in the attempt to fill oversized dimensions.

Figure 21.

The Ascension, the apostles (detail).

Figure 22.

The Ascension, the apostles, the Virgin, and an angel (detail).

The faces, with heavy, shadowed eyes and a characteristic squint, gaze sternly upon the viewer (Figure 10, Figure 12, Figure 14 and Figure 23). The features are linear and organized geometrically. For example, the neck is rendered in the shape of a truncated cone fitted to oval faces, Saint Mamas being a typical example (Figure 11). In this respect, Mamas could be compared to the head of Saint George the church of the Panagia in the village Drymiskos in Hagios Vasileios, Rethymnon (1317/8) (Spatharakis 2001, fig. 42; Varthalitou 2014, pls. 16, 23), despite the somewhat harsher contours and features. Heads such as that of John in three-quarters from the Ascension are comparable to the angels from the southeast cupola at St. John in Episcopi, Mylopotamos (c. 1300) (Spatharakis 2010, p. 246).

Figure 23.

The Ascension, apostle Andrew (detail).

The bare flesh is dominated by a whitish ochre (Figure 24). The contours are strongly emphasized with a demarcated olive-green shadow, a regular feature of many monuments of the period (Figure 25). The geometric rendition of the features is found in monuments of Laconia, such as St Nikitas at Kipoula (probably last quarter of the 13th century) (Drandakis 1995, p. 347, pl. 82) and Saint Michael in Sotira in Kalopyrgos Drys in Mani (second layer, end of the 13th century) (Drandakis 1975, pl. 173 β). In the painting of the church, the accentuation of the features with small details in the figures is avoided, apart from the two small vertical lines at the root of the nose. The highlighting of prominent parts can be compared with the more voluminous style of the frescoes in the church of the Panagia, Haghios Mamas, at Mylopotamos, Rethymnon (1312–1321)56.

Figure 24.

The Ascension, apostle John (detail).

Figure 25.

The Ascension, angels holding the mandorla (detail).

In terms of style, there are no similarities between St Mamas and contemporary monuments of Karpathos, such as the frescoes of St George in Lefkos (beginning of the 14th century) (Katsioti 1996–1997, p. 291). Comparisons with contemporary monuments in Crete inevitably lead to the suspicion that the painter was a Cretan. This is supported by the relations between Karpathos and that great island: trade, historical developments, connections, and proximity, as the fortunes of the island were inextricably linked with Crete. The painting of the church has close affinities with Cretan art, although more detailed comparisons are not easy. However, the technique differs from, say, that of the Veneris family with their squat, almost conservative stylized forms57.

Links with the art of Crete do not end here. In 1399, the embellishment of another church on Karpathos, St Theodore (Aïs Thoris), near Aperi, has affinities with Crete. It is suggested that its founder, the monk Hilarion, perhaps came from there. This argument derives not only from the style but also from the ecclesiastical history of the two islands (Mastrochristos 2011). The trade routes from Crete to Constantinople, as has been noted at the beginning, passed by Karpathos. Art traveled through artists and patrons. In this way, even a very important Cretan icon of the Virgin Mary, dating from the 15th century and possibly attributed to Andreas Ritzos or his workshop, ended up on the barren island of Kasos58.

7. Conclusions

The small, domed chapel of St Mamas is a rare example of the corbelling technique. Its conical dome resembles monuments on the nearby islet of Saria, although its origin and dating are still open to discussion.

The painted decoration is dated precisely to 1312/3 and consists of the Ascension on the dome, the Pantocrator in the apse, and saints. The small dimensions of the chapel led to a compact iconographic program marked by eschatological and soteriological symbolism, healing, and the Orthodox rite. Particularities such as the quotation on the gospel held by Christ and the presence of the healer Saint Cyprian and Pope Sylvester have led to fruitful observations and discussions.

From a stylistic point of view, the precisely dated murals give the impression of an art conservative in iconography and manner, based on older models, although new trends are also detectable amongst the archaisms. Relationships can be noticed with contemporary Byzantine art in Crete, whose influence on nearby territories dependent on it, such as Karpathos, is also attested in other cases.

Of particular interest is the inclusion of Pope Sylvester in the iconographical program of St Mamas. The texts related to the spurious Donation of Constantine spread and became extremely popular. They were used on a case-by-case basis either by Uniates or as models in the relations between the secular authority and ecclesiastical claims to power. A decisive factor in the choice of Sylvester was his special relationship with Constantine the Great. Sylvester’s supposed connection with the founder of the Byzantine capital was presented as legitimate and welcomed. The Donation provided a template for the relationship between church and state, and Sylvester was presented on several occasions as a pillar of good relations between the secular and the ecclesiastical authority. Its dismissal as an 8th-century forgery was still a long way off.

It is no coincidence that in Crete, the iconographical cycles of Constantine as a saint developed at about the same time. We should recall the invocation of the saint as σταυροφόρος (Theocharopoulou 2002, p. 300) in St Constantine, Mylopotamos (1313/4), which refers to his connection with the cross as a symbol. Archaeological evidence on Karpathos, such as the inscription on a cornice from the basilica in Pigadia59, also testifies to the prominent position assumed by the cross shortly after 961, when the great victory against the Arabs and the glorious recapture of Crete were compared to the Elevation of the Cross by Emperor Heraclius, the conqueror of the Persians60. On Karpathos, therefore, as in Crete, it is not difficult to link Constantine the Great and those associated with him, such as Pope Sylvester, with the significance of the Holy Cross. On the island of Karpathos, where the stories about the cross were part of the living tradition, those who were connected with its discovery and elevation, even indirectly, were deeply respected: the glorious victories of the Byzantines, Constantine the Great as a visionary of the cross, Pope Sylvester who converted him to Christianity, and the Byzantine emperors who were sometimes addressed as «New Constantine»61. The connection of the cross with Constantine and thus with Sylvester accords quite satisfactorily with the placement of the latter on the east wall of the church as co-officiating. In addition, the proximity of the pope to the Pantocrator, who holds an open book inscribed with a reference to the «living bread», is a direct reminder of the issue of unleavened bread that resurfaced to trouble the faithful after the Second Council of Lyon (1291). More broadly, through the depiction of Sylvester, the pope is claimed by the Orthodox Church, and the close ties of the Latin-controlled areas with the Byzantine Empire are highlighted. It is not known whether any attempt was made to impose Latin liturgical practices on Karpathos, including the use of unleavened bread. There are no reports of Latin priests there or of the infiltration of Western religious attitudes. However, this particular choice indicates either a borrowing from Crete, probably the native land of our painter, or is a reminder of the conflicts of the time and the religious pressures possibly experienced by the locals. Such a pictorial practice could equally be interpreted in light of the fervent polemic against the Latin church, in order to protect the pious from confusions about dogma. In order to preserve the Orthodox Christian identity from a perceived threat, a multitude of devices of non-violent resistance was invented, including a pretense at compliance, combined with a wait-and-see mindset towards various Latins who took control of the islands, in the ultimate hope of restoring Byzantine rule.

In this context, the inclusion of Sylvester in the murals of St Mamas on Karpathos in 1312/3 probably coincides with a broad ideological reaction against the Latin domination of Greek-speaking territories: their occupation of Aegean islands may well have intensified the old feeling of hostility. Let us recall that Byzantine resentment against the Venetians led to a public riot in Constantinople in 1182, with significant loss of life. It is therefore likely that on Karpathos, at St Mamas at Exeles, during ongoing political and religious upheavals, perhaps even in relation to the reaction against Latin rule, the depiction of a pre-schismatic pope associated with Constantine the Great comprises a means of expressing an anti-Uniate attitude. The islands, even having been under a variety of foreign masters, seem to have been unwaveringly oriented towards Constantinople.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and N.M.; methodology, A.K. and N.M.; software, A.K. and N.M.; validation, A.K. and N.M.; formal analysis, A.K. and N.M.; investigation, A.K. and N.M.; data curation, A.K. and N.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K. and N.M.; writing—review and editing, A.K. and N.M.; visualization, A.K. and N.M.; supervision, A.K. and N.M.; project administration, A.K. and N.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Margarita Voulgaropoulou for the invitation to participate in the present volume. Many thanks are due to Anna-Maria Kasdagli and Prodromos Papanikolaou for their valuable help. The pictures belong to the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | (Udowitch 1977, pp. 510–12). For Karpathos in the medieval times: (Malamut 1988, pp. 40, 85, 92, 158–59, 283, 291, 327, 347, 370, 393, 435, 600; Katsioti and Kiourtzian 2016; Kiourtzian 2021; Katsioti 2021), with recent bibliography. |

| 2 | For imports of wheat from Crete to Karpathos, (Luttrell 1999, p. 755). |

| 3 | (Zachariadou 1983, p. 11). The attacks continued, since in June 1318 the Duca di Candia reported to Venice a Turkish raid against Karpathos, (Zachariadou 1980, pp. 827–28). |

| 4 | (Zachariadou 1983, p. 6). Maybe this explains the fact that in 1307, the island’s village Volada bears a Turkish name. (Pokorny 2008). |

| 5 | For the relations of Venice with the Hospitallers: (Luttrell 1958; Zachariadou 1981, pp. 111–12). |

| 6 | For the backstage, see (Heslop 2017). |

| 7 | For the church, brief mentions in (Moutsopoulos 2012, pp. 388–400), with some misunderstandings of the iconographic program pp. 398–99. (Katsioti 1996–1997, pp. 290–91). |

| 8 | Transcribed as Μάμα instead of Μάμαντος because of the limited space offered. Cf: «σωματοθίκι διαφέροτα τοῦ ἁγίου Μαμᾶ (καὶ) Μακεδονίου», ΜAΜA ΙΙΙ, no. 786. |

| 9 | (Moutsopoulos 2012, p. 398) read only the beginning of the inscription and misinterpreted the word κόπου as κορυφαίου. |

| 10 | Ιω. 6,51: «ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ἄρτος ὁ ζῶν ὁ ἐκ τοῦ οὐρανοῦ καταβάς· ἐάν τις φάγῃ ἐκ τούτου τοῦ ἄρτου, ζήσεται εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα. καὶ ὁ ἄρτος δὲ ὃν ἐγὼ δώσω, ἡ σάρξ μού ἐστιν, ἣν ἐγὼ δώσω ὑπὲρ τῆς τοῦ κόσμου ζωῆς». Cf. (Rigopoulos 1978) for the bread and its significance in Judaism. |

| 11 | For the usual inscriptions on the gospel of Christ, see, e.g., (Kalopissi-Verti 2006, p. 120). |

| 12 | (Vokotopoulos 1990, pp. 59–61). In the 17th century, (Chouliaras 2009, p. 186). |

| 13 | For example, in the church Christ of the Deesis of the church of Phaneromene in Agios Ioannes at Mylopotamos (c. 1300): (Giapitsoglou 2011, p. 71, fig. 78); the Christ Pantocrator of the church of Saint Spyridon in Apostoloi Amari (c. 1300): (Spatharakis and van Essenberg 2012, pl. 586); the Pantocrator at the church of the Virgin at Kissos (1315) and the Christ in the apse of the church of Saint Anthony at the village of Agia Pelagia (c. 1400): (Spatharakis 2015, figs 1, 7, 147); the Christ of Saint Antonios at Margarites, Mylopotamos (beginning of the 15th century): (Spatharakis 2010, pl. 419). In other cases, the medallions include parts of the epithet Pantocrator, such as the church of Saint Marina in Mourne (1300–1320) (Albani 1993–1994, p. 211; Spatharakis 2015, fig. 399). In other examples, the medallions include the abbreviations accompanying the Mother of God (MP ΘΥ), e.g., the Virgin Mary from the homonymous church at Thronos, Amari (c. 1300): (Spatharakis and van Essenberg 2012, p. 586); the murals of St Nicholas at Maza Apokoronas in Crete (1325) on the image of the seated Virgin Mary: (Spatharakis 2001, fig. 60); the Virgin Mary of the church of Saint Paraskevi at Amari (1516), (Spatharakis and van Essenberg 2012, pl. 2), etc. |

| 14 | Aγία Aναφορά, Ευχή Β΄: «Μετὰ τούτων καὶ ἡμεῖς τῶν μακαρίων δυνάμεων, Δέσποτα φιλάνθρωπε, βοῶμεν καὶ λέγομεν: Ἅγιος εἶ καὶ πανάγιος Σὺ καὶ ὁ μονογενής σου Υἱὸς καὶ τὸ Πνεῦμά σου τὸ Ἅγιον. Ἅγιος εἶ καὶ πανάγιος καὶ μεγαλοπρεπὴς ἡ δόξα σου». (Brightmann 1896, p. 324,5; Trempelas 1935, pp. 106, 14; Konstantinidi 2008, p. 224 n. 19). |

| 15 | For the iconography of Saint Theodore Stratelates, see: (Weigert 2008). For Saint Theodore, see (Walter 1999, 2003, pp. 44–66; Delehaye 1909, p. 15; Mavrodinova 1969; Oikonomidès 1986). More recently: (Haldon 2016). |

| 16 | She usually has no ornaments on her clothes, unlike other female saints (Kefala 2015, p. 204). For the saint’s iconography, see: (Koukiaris 1994; Walter 1995). |

| 17 | As in the Panagia “stis Giallous” in Naxos (1288/9): (Chatzidakis 1989, p. 103, fig. 6) (Nikolaos Drandakis) or in Saint Nicholas at the Castle of Zarnata (second half of the 15th century) (Drandakis et al. 1981, p. 484). For the two saints and their symbolisms, (Gerstel 1998, p. 100; Gerstel 2015, p. 66). |

| 18 | The saint is often portrayed among the officiating bishops; see, for instance, (Konstantinidi 2008, p. 229). |

| 19 | For the iconography of Saint Mamas, see (Marava-Chatzinikolaou 1995; Balicka-Witakowska 1966; Gabelić 1986; Bonovas et al. 2013). For the saint’s vita, (Kyrris 2001; Spatharakis et al. 2003; Ruggieri 2018; Tsilipakou 2018). |

| 20 | (Kalopissi-Verti 2006, pp. 107–32). For the painted ones, p. 113 ff. |

| 21 | For the medical tools in Byzantine painting, see (Parani 2003, pp. 204–5; Charitopoulos 2014; Pajić 2014). |

| 22 | For Saint Panteleemon’s life, passion, and hymnography: (Makris 2009; Caserta 2009; Passaris 2009; Gerstel 2012; Papanikolaou 2017, pp. 204–8), with the literature. See also, recently: (Starodubcev 2018, p. 55 ff). |

| 23 | For his cult in the islands of the Dodecanese, (Katsioti 2012, pp. 670–71; Papanikolaou 2017). |

| 24 | (Fletcher 1852, p. 118), states that Constantine was baptized shortly before his death by the bishop of Nicomedia, Eusebius, who was a follower of Arius and subsequently ascended the throne of Constantinople. See also (Dölger 1913, pp. 377–447). (Dagron 2007, pp. 145–48). The status of Eusebius may have been the pretext for the Orthodox version of the baptism of Constantine. |

| 25 | One of the basic theological and liturgical differences between Orthodox and Latin Christians was the issue of leavened and unleavened bread, which was widely discussed at the Councils of Lyon and of Ferrara-Florence, (Gill 1959), ch. 1, The background, pp. 1–15. For the dispute, see (Leib 1924; Smith 1978). The issue of unleavened bread seems to have dominated Byzantine consciousness thereafter even more than the questions of the filioque and papal sovereignty, cf. (Erickson 1970). |

| 26 | (Kontogiannopoulou 1998, p. 177). The Arseniates spread the word that the emperor Michael took communion with unleavened bread, see also (Gounaridis 1999, pp. 102–3, 218). |

| 27 | For all this, see comments by (Angelov 2009, pp. 104–12). |

| 28 | As from Makarios of Ankara, (Angelov 2009, pp. 122–24). Other Western scholars followed. See also (Fried 2007, p. 3). |

| 29 | For depictions of popes in Byzantine art, see (Passaris, forthcoming). |

| 30 | 11th century: (Peers 2000, pp. 267–92), esp. pp. 276–77. |

| 31 | 11th century: (De Wald 1942, pp. 13, 20, 25, 31–32). In f. 51r (Psalm 16) Sylvester is depicted holding a closed gospel and burning incense to the sons of Korah before an icon of the Virgin and child; on f. 142v (Psalm 42), he is pictured conversing with King David, a theme that recurs; on f. 193v (Psalm 62) he is represented by a group of three worshippers with strange headdresses; on f. 298v (Psalm 94), he is depicted with a group of believers approaching the sanctuary; and finally, on f. 322v (Psalm 104), he prays before the Ark of the covenant. For the ms, see also (Jenkins and Kitzinger 1967, p. 247, n. 15; Kalavrezou-Maxeiner 1982, pp. 453–45; Walter 1982, p. 60). For the views and interpretation of the illustration, see (Kalavrezou et al. 1993; Crostini and Peers 2016). From what is inferred, there was a narrative cycle of his life, which, however, does not seem to coincide with the better-known one, in the church of the Quattro Coronati. Besides the two scenes in the Smyrna Physiologus manuscript, a further scene with Sylvester and musicians is also unique: (Peers 2000, p. 287, n. 56). One wonders whether the vita of Sylvester is intertwined with the iconographical cycle of Saint Constantine, something likely, judging from a later icon (1732, by Emmanuel, the priest) (Vassilaki 1987, pp. 82–83; Walter 2006, pp. 122–25, figs 119–29): it shows scenes from the life of Constantine, where the apostles Peter and Paul appear in a dream to Constantine, a scene that, in reality, belongs to the vita of Sylvester. |

| 32 | (Jenkins and Kitzinger 1967, pp. 233–49; Cotsonis 1994, p. 81; Mango 1988, pp. 41–49). The scene depicts the episode of Constantine’s miraculous healing from leprosy after a dream he had with Peter and Paul or, as Mango believes, Constantine’s conversion to Christianity. Mango rejects the connection of the object with Michael Cerularius and suggests it came from a chapel dedicated to Saint Constantine in an Asia Minor monastery. |

| 33 | Cf. he is depicted in the Vat. gr. 1156 (11th c), (Mijović 1973, p. 195). Kryptoferris Da XII (11th c), (Mijović 1973, p. 201). Tbilisi A. 648 (12th c), (Mijović 1973, p. 193). Paris. gr. 1561, f. 7v (13th c.), (Mijović 1973, p. 204). |

| 34 | (Barbu 1986, p. 53), iconographic inventory under numbers 62–66 (Bedros 2019, fig. 4). |

| 35 | (Todić 1995, pp. 57–61, 149, 153, pl. 32, 56–59. 61, 101, 107; Konstantinidi 2008, p. 215, fig. 267; Prolović 2017, pp. 188–89, fig. 117, 120). Sylvester is depicted in the last part of the procession. |

| 36 | (Spatharakis 2001, pp. 73–74), where Constantine the Great is shown without Helen. As he notes, the reference to the Venetians as rulers of Crete is quite exceptional. (Lymberopoulou 2006, p. 45) did not identify the bishop, nor comment on the pictorial choice of Constantine without Helen. |

| 37 | (Spatharakis 2001, p. 98). In contrast, (Vassilaki 1987, pp. 75, 80–82, n. 34, pl. 33α) considers that in this scene it is not Sylvester who baptizes Constantine, but another bishop. For the scenes of Constantine’s life beyond the churches of Crete, see (Vassilaki 1987; Walter 2006, pp. 111–26), and sporadically, (Theocharopoulou 2002, pp. 315–25, 344–47). |

| 38 | According to Ermeneia he is represented as an old man with a long beard, see (Papadopoulos Kerameus 1909, p. 154). Ὁ Σίλβεστρος, πάπας Ῥώμης, γέρων μακρυγένης, λέγει: «Σοὶ παρακατιθέμεθα τὴν ζωὴν ἡμῶν». |

| 39 | (Bedros 2019, p. 14, n. 94, fig. 11). Mango’s hypothesis about the so-called cross of Kerularios and its connection with a chapel dedicated to Constantine comes to mind, (Mango 1988, p. 48). |

| 40 | Perhaps the depictions of Sylvester in Serbian churches are not unrelated to the one recorded in the Σύνταγμα of Matthaios Vlastaris in 1335, but it had already existed from the early 13th c. The abbreviated version of the Donation highlights the role of Sylvester in order to support the supremacy of the patriarchate of Constantinople, which enjoys the privileges of the See of Rome as the beneficiary of the Donation. For references to the text of Vlastaris, see (Angelov 2009, pp. 107–8). |

| 41 | A similar scene appears in the murals of the life of Pope Sylvester in SS. Quattro Coronati in Rome (1243–1254), see (Jenkins and Kitzinger 1967, p. 247, fig. 3; Walter 2006, fig. 50), and in a manuscript of the early 14th century, see (Jenkins and Kitzinger 1967, p. 247, n. 13a). |

| 42 | (Mango 1988, p. 46). And not the subordination of the secular to ecclesiastical authority. |

| 43 | (Mango 1988, p. 46). As is the view that the pieces of the cross belong to a single item. |

| 44 | (Jenkins and Kitzinger 1967, pp. 235–39). About Cerularius, see also (Angold 1994, pp. 236–46). |

| 45 | As in the funerary chapel of Cozia, (Bedros 2019, p. 7, n. 25). |

| 46 | For the representation of the 70s, see (Aspra-Vardavaki and Emmanouel 2005, pp. 226–28). |

| 47 | (Guran 2007, pp. 136–38). But it was not only the Serbian kings who were New Constantines. It was used for Heraclius after his victories over the Persians and also for Basil I (867–886), see (Der Nersessian 1962, p. 220, n. 108). On the use and the significance of the epithet Novus Constantinus for Heraclius, (Bell 1913, pp. 395–405), while later, (Grégoire 1935) deals with other cases as well. See also (Walter 2006, pp. 104–6). |

| 48 | (Guran 2007, pp. 142–57). For the connection of the Nemanjić dynasty with Constantine, see (Đurić 2000). |

| 49 | Moreover, the Paschal Chronicle, compiled shortly after 629, attributes the baptism of Constantine to Eusebius of Nikomedia (ed. Dindorf, Chronique paschal 1832), as does a text by the monk Alexander, perhaps from the 6th century (PG 86, 4019–4049). |

| 50 | The depiction of Constantine the Great without Helen is perhaps a reference to the Venetians as rulers of Crete, something quite exceptional, see (Spatharakis 2001, p. 73; Lymberopoulou 2006, p. 45), who also notes the peculiarities observed due to the invocation of the Venetians in the owner’s inscription. |

| 51 | (Kalopissi-Verti 2021, pp. 59–78). Such is the case of Latin-ruled Orthodox Cyprus and the expressions of hostility against Western religious standards, see (Kyriacou 2018, pp. 38–48). |

| 52 | As in St. Demetrius at Makrichori on Euboea, in the Omorfi Ekklisia at Aegina (1289), and Saint George Vardas on Rhodes (1289/90), see (Katsioti 1996–1997, p. 291). |

| 53 | See the archangel Gabriel, (Spatharakis 2001, fig. 54). |

| 54 | See the Christ from Anastasis, (Spatharakis 2015, p. 387). |

| 55 | See angel from Ascension, (Spatharakis 2001, fig. 88). |

| 56 | See St Mamas, (Spatharakis 2001, fig. 24). |

| 57 | About the Veneris family, see recently, (Ioannidou and Papathanasiou 2021, pp. 269–85). |

| 58 | The icon is currently under conservation and thus the observations are preliminary. It is, however, definitely a Cretan masterpiece dating to the 15th century. |

| 59 | Today at the Archaeological Museum of Karpathos (Katsioti and Kiourtzian 2016). |

| 60 | The so-called cross of Cerularius was also indirectly associated with the Holy Cross because of the representation of the conversion of Constantine by Sylvester: (Mango 1988, p. 47), in citing a collection of miracles of the archangel attributed to Michael Psellos, with acuity pointed out that the triumphant Heraclius, conqueror of the Persians, dedicated a cross in a chapel of Constantine in a monastery of the archangel Michael of the so-called Sykees in Asia Minor and argues that it is the same one, to which, according to the narrative, a revetment was added, apparently of silver, in the 11th c. We consider that the inclusion in the iconographical circle of the archangel of the scene of the Baptism of Constantine in Bãlimeşti confirms the view of the connection of the scene and the cross with the archangel Michael. |

| 61 | Emperor Michael VIII was also hailed as New Constantine, as the restorer of the Empire immediately after the recapture of Constantinople in 1261, see (Dagron 1977, pp. 191–202; Macrides 1980, pp. 15, 23–24, n. 55). In the Protaton, Michael VIII’s successor, Andronicus, also appears to be depicted as Constantine the Great (or the saint as Andronikos?), without Saint Helen; he appears in a position often chosen in the Serbian monuments for the portraits of donor kings, namely in the western part of the church, sideways, near the entrances, see (Vassilakeris 2013). |

References

- Abulafia, David, and Massimo Naro. 2013. La Cathédrale de Monreale. La splendeur des mosaiques. Paris: Cerf. [Google Scholar]

- Acheimastou-Potamianou, Myrtali. 1994. Βυζαντινές Τοιχογραφίες. Athens: Ekdotiki Athinon. [Google Scholar]

- Acheimastou-Potamianou, Myrtali. 1997. Εικόνες της Ζακύνθου. Athens: Ιερά Μητρόπολις Ζακύνθου και Στροφάδων. [Google Scholar]

- Ahrweiler, Hélène. 1966. Byzance et la mer: La marine de guerre, la politique et les institutions Maritimes de Byzance aux VIIe-XVe siècles. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Albani, Jenny. 1993–1994. Oι τοιχογραφίες του ναού της Aγίας Μαρίνας στον Μουρνέ της Κρήτης. Ένας άγνωστος βιογραφικός κύκλος της αγίας Μαρίνας. Deltion tes Christianikes Archeologikes Etaireias 19: 211–22. [Google Scholar]

- Albani, Jenny. 2000. Die Byzantinischen WandmalereienderPanagia Chrysaphitissa-Kirchein Chrysapha, Lakonien. Athens: Christian Archaeological Society. [Google Scholar]

- Altripp, Michael. 1998. Die Prothesis und ihre Bildausstattung in Byzanz unter besonderer Berücksichtung der Denkmäler Griechenlands. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang GnbH. [Google Scholar]

- Andronikou, Anthi. 2017. Southern Italy, Cyprus, and the Holy Land: A Tale of Parallel Aesthetics? The Art Bulletin 99: 6–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelov, Dimiter G. 2009. The Donation of Constantine and the church in Late Byzantium. In Church and Society in Late Byzantium. Edited by Dimiter Angelov. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University, pp. 91–144. [Google Scholar]

- Angold, Michael. 1994. Imperial renewal and orthodox reaction. Byzantium and the eleventh century. In New Contantines. The Rhythm of Imperial Renewal in Byzantium, 4th-13th Centuries, Papers from the Twenty-Sixth Spring Symposium of Byzantine Studies. St Andrews March 1992. Edited by Paul Magdalino. Aldershot: Ashgate, pp. 231–46. [Google Scholar]

- Aspra-Vardavaki, Maria, and Melitta Emmanouel. 2005. H μονή της Παντάνασσας στον Μυστρά. Oι τοιχογραφίες του 15ου αιώνα. Athens: Commercial Bank of Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Ataç, Nergis. 2022. Yüzyilda Anadolu ve Kafkasya: Mkhargrdzeli Sülalesine Baǧli Mimirade Papa I. Sylvester Figürü. SEFAD 47: 235–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacheva, Tereza. 2022. Pope Sylvester from the St. Stephen Church in Nessebar. In Personalia, Art Readings 2021. Edited by Emmanuel Mutavof and Margarita Kuyumdzieva. Sofia: Institute of Art Studies, pp. 169–89. [Google Scholar]

- Balicka-Witakowska, Εwa. 1966. Mamas: A Cappadocian Saint in Ethiopian Tradition. In Λειμών, Studies Presented to Lennart Rydén on his 65 Birthday. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Uppsaliensis, pp. 211–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bara, Péter. 2017. The Use of the Donation of Constantine in Late-Eleventh-Century Byzantium: The Case of Leo Metropolitan bishop of Chalcedon. Chronica 17: 106–25. [Google Scholar]

- Barbu, Daniel. 1986. Pictura murală din Țara Românească în secolul al XIV-lea. Bucharest: “Meridiane” Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Bedros, Vlad. 2019. The Popes of Rome in Post-Byzantine Wall Paintings from Romania. Anastasis Research in Medieval Culture and Art 6: 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Harold Idris. 1913. A dating clause under Heraclius. BZ 22: 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonovas, Nikolaos, Agathoniki Tsilipakou, and Christodoulos Hatzichristodoulou. 2013. H τιμή του αγίου Μάμαντος στη Μεσόγειο: ένας ακρίτας άγιος ταξιδεύει. Exhibition Catalogue. Thessaloniki: Μουσείο Βυζαντινού Πολιτισμού. [Google Scholar]

- Borboudakis, Manolis. 1991. «Παρατηρήσεις στη ζωγραφική του Σκλαβεροχωρίου». In Ευφρόσυνον. Aφιέρωμα στον Μανόλη Χατζηδάκη, Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού. Athens: Ταμείο Aρχαιολογικών Πόρων και Aπαλλοτριώσεων, vol. 1, pp. 375–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bormpoudaki, Maria. 2020. O αρχικός ναός της Παναγίας της Oδηγήτριας. In ΜyrtaliAcheimastou-Potamianou, Angeliki Katsiotiand Maria Bormpoudaki, Oι τοιχογραφίες της μονής του Βαλσαμονέρου. Aπόψεις και φρονήματα της ύστερης βυζαντινής ζωγραφικής στη βενετοκρατούμενη Κρήτη. Athens: Kέντρο Έρευνας της Βυζαντινής και Μεταβυζαντινής Τέχνης, Aκαδημία Aθηνών, pp. 53–180. [Google Scholar]

- Brightmann, Frank Edward. 1896. Liturgies Eastern and Western, I, Eastern Liturgies. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brodbeck, Sulamith. 2010. Les Saints de la Cathédrale de Monreale en Sicile. Iconographie, Hagiographie et Pouvouir Royal à la fin du XIIe siècle. Rome: École Française de Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Caserta, Claudio. 2009. Pantaleone da Nicomedia Santo tra Cielo e Terra: Reliquie, Culto, Iconografia. I santi Venuti Dall’oriente. Trifone e Barbara sul Cammino di Pantaleone. Napoli: Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane. [Google Scholar]

- Charitopoulos, Evangelos. 2014. Ιατρικά εργαλεία σε παραστάσεις ιαματικών αγίων. Περιπτώσεις από τοιχογραφημένους ναούς του Aμαρίου. In H επαρχία Aμαρίου από την αρχαιότητα έως σήμερα. Πρακτικά Διεθνούς Επιστημονικού Συνεδρίου, Δήμοι Κουρητών και Συβρίτου 27–31 Aυγούστου 2010. Edited by Stergios Manouras. Athens: Belfast Byzantine Enterprises, vol. 1, pp. 303–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzidakis, Manolis. 1977. Εἰκόνες τῆς Πάτμου. Athens: Εθνική Τράπεζα της Ελλάδος. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzidakis, Manolis. 1989. Βυζαντινή τέχνη στην Ελλάδα. Νάξος. Athens: Μέλισσα. [Google Scholar]

- Chouliaras, Ioannis. 2009. H εντοίχια θρησκευτική ζωγραφική του 16ου και 17ου αιώνα στο δυτικό Ζαγόρι. Athens: Ριζάρειο Ίδρυμα. [Google Scholar]

- Chronique paschale. 1832. Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae. 2 vols, Edited by Ludvig Dindorf. Bonnae: Weber. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, Kathleen. 1997. The Smyrna Physiologos and Eleventh-century Monasticism. In Work and Worship in the Theotokos Evergetis 1050–1200. Edited by Margaret Mullet and Anthony Kirby. Belfast Byzantine Texts and Translation. Belfast: Belfast Byzantine Enterprises, pp. 201–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cotsonis, John. 1994. Byzantine Figural Processional Crosses. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. [Google Scholar]

- Crostini, Barbara, and Glenn Peers, eds. 2016. A Book of Psalms from Eleventh Century Byzantium: The Complex of Texts and Images in Vat. Gr. 752. Cittá del Vaticano: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. [Google Scholar]

- Dagron, Gilbert. 1977. Byzance et l’Union, 1274. In Année charniére, Mutations et continuités, Colloques internationaux du CNRS 558. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, pp. 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Dagron, Gilbert. 2007. Emperor and Priest. The Imperial Office in Byzantium. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Wald, Ernest T. 1942. The Illustrations in the Manuscripts of the Septuagint, III, Psalms and Odes, 2, Vaticanus graecus 752. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Delehaye, Hippolyte. 1902. Propylaeum ad Acta Sanctorum Novembris, Synaxarium Ecclesiae Constantinopolitanae e Codice Sirmoniando. Brussels (Louvain 21954). [Google Scholar]

- Delehaye, Hippolyte. 1909. Les légends grecques des saints militaires. Paris: Librairie Alphonse Picard et Fils. [Google Scholar]

- Deligiannakis, Georgios, and Vassilis Karabatsos. 2017. Palatia of Saria, a Late ‘Nesopolis’ of Provincia Insularum: A Topographical Survey. In New Cities in Late Antiquity. Documents and Archaeology (Bibliothéque de lAntiquité Tardive 35). Edited by Efthymios Rizos. Turnhout: Brepols, pp. 267–80. [Google Scholar]

- Der Nersessian, Sirarpie. 1962. The Illustrations of the Homilies of Gregory of Nazianzus Paris.Gr. 510. A Study of the Connection between Text and Images. DOP 16: 195–228. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl, Charles. 1889. L’église et les mosaiques du couvent de Saint-Luc en Phocide. Paris: Bibliothéque des écoles françaises d’ Athènes et de Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Diez, Ernst, and Otto Demus. 1931. Byzantine Mosaics in Greece. Hosios Lucas and Daphni. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dölger, Franz Joseph. 1913. Die Taufe Konstantins und ihre Probleme. In Konstantin der Grosse und seine Zeit, Gessammelte Studien. Festgabe zumKonstantins-Jubiläum 1913 und zum goldenen Priesterjubiläum von Mgr. Dr. A. de Waal. In Verbindung mit Freunden des deutschen Campo Stato in Rom (XIX. Supplementheft der Römischen Quartalschrift). Freiburg: Herder, pp. 377–447. [Google Scholar]

- Drandakis, Nikolaos. 1975. Έρευναι εις την Μάνην, ΠAΕ (Πρακτικά της Εν Aθήναις Aρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας) 1975, A’. 184–96. [Google Scholar]

- Drandakis, Nikolaos. 1979. Παναγία ἡ Βρεστενίτισσα. In Πρακτικά A΄ Λακωνικού Συνεδρίου (Σπάρτη-Γύθειο, 7–11 Ὀκτωβρίου 1977), ΛακΣπΔ΄. pp. 160–85. [Google Scholar]

- Drandakis, Nikolaos. 1988. Oι παλαιοχριστιανικές τοιχογραφίες στη Δροσιανή της Νάξου. Athens: Ταμείο Aρχαιολογικών Πόρων και Aπαλλοτριώσεων. [Google Scholar]

- Drandakis, Nikolaos. 1995. Βυζαντινές τοιχογραφίες Μέσα Μάνης. Athens: Archaeological Society. [Google Scholar]

- Drandakis, Nikolaos, Eleni Doris, Sophia Kalopisi, Victoria Kepetzi, and Maria Panagiotidi. 1981. Ἔρευνα στὴ Μάνη, Πρακτικά της εν Αθήναις Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας. Athens Archaeological Society. 449–578. [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne, Louis. 1955. Le Liber Pontificalis. Paris: E. Thorin. [Google Scholar]

- Ðurić, V. 1963a. Die Kirche der Hl. Sophie in Ohrid. In Reihe Kunstdenkmäler in Jugoslawien. Beograd: Jugoslavija. [Google Scholar]

- Ðurić, V. J. 1963b. Sopoćani. Beograd: Umetnichki Spomenitsi Jugoslavije. [Google Scholar]

- Đurić, Vojislav J. 2000. Le nouveau Constantin dans l’art serbe medieval. In ΛΙΘOΣΤΡΩΤOΝ, Studien zur byzantinischen Kunst und Geschichte. Festschrift für Marcell Restle. Edited by Birgitt Borkopp and Thomas Steppan. Suttgart: Anton Hiersemann Verlag, pp. 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Eliadis, I., ed. 2019. Palaeologan Reflections in the Art of Cyprus (1261–1489), Exhibition Catalogue. Nicosia: Archibishop Makarios III Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouel, Melita. 1991. Die Fresken der Kirche des Hosios Ioannes Kalybites auf Euboia. Byzantinoslavica 52: 136–44. [Google Scholar]

- Endrich, E. 1994. Cyprian von Karthago. LCI 6: 12–14. Available online: https://brill.com/display/db/lcio?language=en (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Erickson, John H. 1970. Leavened and unleavened: Some Theological Implications of the Schism of 1054. St Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 14: 155–76. [Google Scholar]

- Eustratiades, Sofronios. 2010. Ἁγιολόγιον τῆς Ὀρθοδόξου Ἐκκλησίας. Athens: Apostoliki Diakonia of the Church of Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, J. 1852. Life of Constantine the Great. London: Kessinger Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fougias, Methodios G. 1994. H εκκλησιαστική αντιπαράθεσις ελλήνων και λατίνων από της εποχής του Μεγάλου Φωτίου μέχρι της Συνόδου της Φλωρεντίας. Athens: Apostoliki Diakonia of the Church of Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Fraidaki, Athina. 2014. Oι τοιχογραφίες του ναού της Παναγίας στον Κισσό Aγίου Βασιλείου. In Πρακτικά Διεθνούς Επιστημονικού Συνεδρίου. H Επαρχία Aγίου Βασιλείου από την αρχαιότητα μέχρι σήμερα, vol. Β’, Βυζαντινοί χρόνοι–Βενετοκρατία. Rethymno: Ενωση Συλλόγων Επαρχίας Aγίου Βασιλείου “O Πρέβελης”, pp. 153–84. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, Johaness. 2007. Donation of Constantine and Constitutum Constantini. The Misinterpretation of a Fiction and its Original Meaning. Millennium-Studies in the Culture and History of the First Millennium C.E. Edited by Wolfram Brandes, Alexander Demandt, Helmut Krasser, Hingegen Leppin and Peter von Möllendorff. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Gabelić, Smiljka. 1986. Contribution to the Iconography of Saint Mamas and Saints with Attributes. Unpublished Fresco of St. Mamas and St. Vlasios ‘Voucolos’. In Πρακτικά Β ’ Διεθνούς Κυπριολογικού Συνεδρίου. Nicosia: Εταιρεία Κυπριακών Σπουδών, vol. 2, pp. 577–81. [Google Scholar]

- Galavaris, George. 1969. The Illustrations of the Liturgical Homilies of Gregory of Nazianzus. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galavaris, George. 2009. An Eleventh Century Hexaptych of the Saint Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai. Venice and Athens: Hellenic Institute of Byzantine and Post Byzantine Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Gerstel, Sharon. 1998. Painted Sources for Female Piety in Medieval Byzantium. DOP 52: 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]