Abstract

Lessing’s Laokoon from 1766 is still an important text in the discussion on the borders between different arts and their media. Especially in the 20th century, texts were written that referred back to Lessing’s seminal text. One of the most important ones, which will receive a detailed discussion, is Clement Greenberg’s “Towards a Newer Laocoon”. The discussion will on the one hand start from the observation that drawing borders between different arts and their media has always had political implications. On the other hand, this discussion will be related to the transformation to digital media in the late 20th century. By reading Greenberg and discussing some examples from art, especially from the recent field of AI-generated imagery, the concept of “digital modernism” and its political implications will be introduced. The two main findings are as follows: Firstly, it might be problematic to construct a progression from medium-centered to multimedial art since both tendencies coexist in contemporary art. Secondly, the current situation once again points to the politics of drawing borders between different arts (and their respective media).

1. Introduction: Politics of Media Borders

Ever since its publication in 1766, Lessing’s Laokoon has been a source for discussions on how to draw borders between different arts and their media1 and what should legitimately be done with them (see amongst many others Wellbery 1984; Burwick 1999). There are even many famous texts that reference the Laokoon in their titles: Irving Babbitt’s The New Laokoon from 1910, Rudolf Arnheim’s paper “A New Laocoön: Artistic Composites and the Talking Film” from 1938 (Arnheim [1938] 2006) and Clement Greenberg’s “Towards a Newer Laocoon” from 1940, to mention some well-known examples.

The modest goal of this essay is to add a footnote to this impressive and complex discussion. Firstly, I want to address a question: Is the fact that many texts in modernity draw borders between the arts and their media, and even more to the point, that they feel the urge to do so, not in itself a political gesture? If so, renouncing or problematizing media borders is also a political gesture (see Schröter 2010). Secondly, I will try to relate this question to the medial situation of the late 20th and early 21st century, that is, to digital technologies and their effects on borders between media and arts.

What I call the “Laocoon moment” is when borders between the arts and their media are drawn or withdrawn and thereby problematized. Sometimes (and perhaps even most often) this happens without explicitly mentioning Lessing and his Laokoon—but this text from 1766 is seen as a paradigmatic case even today. One situation in which Laocoon moments happen is when established aesthetic conceptions are worn out. Lessing opposed the classical paradigm “ut pictura poesis” that was handed down from antiquity. It equates painting and poetry in a fundamental way and therefore ignores their different potentials. In the Paragone in the Renaissance and later, it was discussed which form of art might be the leading one—this was a political question in the sense that a hierarchy of the arts was debated. Lessing rejected this in a way—not coincidentally reminding us of his play Nathan the Wise, where he argued for tolerance between the religions—because his question was not which art is the highest form, that is, the king of the arts. Instead, he argued that the different art forms were equal in rank but different in possibilities. While painting and sculpture are concerned with space, poetry is to be centered around time. There are different political models implicated in these different ways of comparing and classifying the arts.2 The seeming equality of the arts is described in very political metaphors of borders: “Nevertheless, the mutual relation which exists between poetry and painting may be likened to the rational policy of two neighboring and friendly states […]” (Lessing 1836, p. 178). In a close reading, Mitchell (1986, pp. 105–7) showed that the alleged equality of the arts in Lessing is permeated by nationalist ideology. Moreover, and even more importantly, the equality includes an implicit gender hierarchy (108–111). Lessing’s fundamental “categories of space and time are never innocent” (100).

As stated above, this discussion did not end with Lessing—on the contrary. In 1910, Babbitt drew on the Laokoon to criticize what he saw as the “pseudo-classic” and then “romantic” confusion of the arts: “The nineteenth century witnessed […] a general confusion of the arts, as well as of the different genres within the confines of each art” (Babbitt 1910, p. ix). He even tries to extend Lessing’s argument, since Babbitt opposes “especially the attempts to get with words the effects of music and painting” (x), while music was not prominent in the Laokoon (see Richter 1999). In doing so, Babbitt draws a somewhat surprising analogy: “[Lessing] is in some respects the most masculine figure Germany has produced since Luther; and without being too fanciful one may follow out certain analogies between the role played by Luther and that played by Lessing in an entirely different field” (Babbitt 1910, pp. 36–37; here again gender implications are obvious; see on this also Gustafson 1995). The work of Luther, arguing for a fresh reading of the holy scriptures and criticizing the distortion of the scriptures by the practice of the Catholic church, is compared to that of Lessing, who is described as a “lover of boundaries and distinctions, and of the clearly defined type” (Babbitt 1910, p. 39). We should perhaps not make too much of this comparison between Luther and Lessing. This political implication might not be as systematic as Lessing’s move from the question of which art might be the primary one to a more egalitarian scenario, but at least for Babbitt, it was seemingly unavoidable to equate Lessing’s efforts to clarify the rightful realms of the different arts with an important reformative, and therefore unavoidably political, gesture.

Since this issue is centered on contemporary visual arts and Clement Greenberg, and as his insistence on purity in the different arts is mentioned explicitly in the exposé, I will focus on the Laocoon moment of Greenbergian modernism. Although Greenberg’s plea for purity in the arts in his “Towards a Newer Laocoon” is nowadays seen as a worn-out paradigm, superseded in the 1970s by new (“postmodern” as it was then called) approaches that rejected Greenberg’s insistence on medial purity, it has had a comeback with the advent of digital technologies and the aesthetic challenges they pose. The questions of whether, how and in which way the arts should be separated are still relevant.

In Section 2, I want to discuss Greenberg’s approach, especially in “Towards a Newer Laocoon”. I will emphasize some of the political implications—especially his insistence on the “medium”, since this base is significantly transformed by the technological and political changes in the late 20th and early 21st century. As with Lessing’s categories of space and time, the media (technological or otherwise) operating on and with space and time today are never innocent. In Section 3, I will discuss the, perhaps somewhat surprising, idea that the modernist strategy of media reflexivity has not disappeared since the 1960s—it coexists beside intermedial approaches and especially in a new form, as “digital modernism”. In Section 4, I will come back to the political questions of drawing borders between arts and media in regard to this phenomenon by discussing a controversial, AI-generated image by Boris Eldagsen.

2. Greenberg’s “Towards a Newer Laocoon”

In “Towards a Newer Laocoon” (and in many later texts), Clement Greenberg ([1940] 1988, pp. 26–27) argued for a purification of the arts. Similar to Babbitt, he accused romanticism of a confusion of the arts. More precisely, Greenberg argues that there can be a “dominant art form” (24) in a given epoch. This resembles the Paragone, although it is not meant normatively (in the sense that one art should be the leading art) but simply descriptively (although it is left open if such a dominant medium must necessarily exist in every epoch). For the 17th century in Europe, he defined literature as the dominant art form. This dominance had a destructive effect on the other arts: “The dominant art in turn tries itself to absorb the functions of the others. A confusion of the arts results, by which the subservient ones are perverted and distorted; they are forced to deny their own nature in an effort to attain the effects of the dominant art. However, the subservient arts can only be mishandled in this way when they have reached such a degree of technical facility as to enable them to pretend to conceal their mediums” (24; emphasis in the source). Here we can already find political metaphors: dominance and submission. Techniques are so highly developed in the subservient arts that an illusionistic dissimulation of the medium is achieved. The subservient arts are forced to hide themselves in a way. It is an interesting question how exactly this is supposed to work: insofar as the given technique is at least possible in the medium, how can it make the medium invisible? The prime example for Greenberg is the illusionistic image-space that developed after the invention of perspective in the Renaissance. To the extent to which we seem to look through a fenestra aperta into a scene or a story, painting emulates the narrative operations of literature (at least if “painting and sculpture [are] in the hands of the lesser talents”, 25). In romanticism, this situation became worse because painting was understood as a channel of expressing the artist’s inner world. “It was not realistic imitation in itself that did the damage so much as realistic illusion in the service of sentimental and declamatory literature” (27). In Greenberg’s eyes, the “avant-garde” was a kind of resurrection of the arts. “The history of avant-garde painting is that of a progressive surrender to the resistance of its medium; which resistance consists chiefly in the flat picture plane’s denial of efforts to ‘hole through’ it for realistic perspectival space” (34). By showing that a painting is a painted, opaque surface, the avant-garde destroyed illusionistic image-space and made the medium as the basis of the art of painting visible.

Before I come to the political implications of Greenberg’s approach, I want to point out a less-discussed aspect: First, drawing clear borders around a medium and purifying it from problematic influences of other media (or only of the dominant medium?) seems not to be the only strategy of the avant-garde. In section IV of his seminal paper, Greenberg discusses the “second variant of the avant-garde’s development” (30). “It is easy to recognize this variant, but rather difficult to expose its motivation” (30): “Each art would demonstrate its powers by capturing the effects of its sister arts or by taking a sister art for its subject. Since art was the only validity left, what better subject was there for each art than the procedures and effects of some other art” (30)? An intensified simulation of sister arts is the other strategy of the avant-garde. Interestingly, music plays an important role here—on the one hand as an art that was especially infected by this second variant: “Music, in flight from the undisciplined, bottomless sentimentality of the Romantics, was striving to describe and narrate (program music)” (30).3 On the other hand, and more importantly, Greenberg saw music as a kind of structural model for the arts: “But only when the avant-garde’s interest in music led it to consider music as a method of art rather than as a kind of effect did the avant-garde find what it was looking for. It was when it was discovered that the advantage of music lay chiefly in the fact that it was an ‘abstract’ art, an art of ‘pure form’” (31; emphasis in the source). He concludes: “Guiding themselves, whether consciously or unconsciously, by a notion of purity derived from the example of music, the avant-garde arts have in the last fifty years achieved a ‘purity’ and a radical delimitation of their fields of activity for which there is no previous example in the history of culture” (32). It is a somewhat paradoxical argument that the purity, let us say of painting, is found in the model of music. Similarly to the point mentioned above that it seems surprising that a given art should use its medial possibilities to conceal its medium, this suggests a complexity of the notion of medium. One form of intermedial relations can be called “ontological intermediality” (Schröter 2012)—meaning that even the most basic definition of the specificity of a given medium requires relations to other media (at least in the sense that medium A is as such different from medium B). In that sense, pure media are not given, but they have to be constructed from a primordial intermediality. The practice of Jackson Pollock, an important example in Greenberg for reflexive, pure painting, is not a realization of an essence of the medium of painting that has been found, but the construction of an example of such a “pure” medium.

After the sentence in which he declared the “radical delimitation of [of the arts’] fields of activity” (Greenberg [1940] 1988, p. 32), he writes: “The arts lie safe now, each within its ‘legitimate’ boundaries, and free trade has been replaced by autarchy. Purity in art consists in the acceptance, willing acceptance, of the limitations of the medium of the specific art” (32). That the “radical delimitation” is connected to “legitimate boundaries” relates to the paradoxical figure of the medium finding the model of its purity in another medium. But moreover, “free trade has been replaced by autarchy”. In this quote, quite close to Lessing’s “two neighboring and friendly states” (Lessing 1836, p. 178), the political implications become clear. As has been analyzed by Clark (1982), Greenberg’s discourse (at least at the time and in the context when “Toward a Newer Laocoon” was written) was indeed quite political, since he was close to Trotskyism. Therefore, his privileging of “autarchy” in spite of “free trade” between the arts is not surprising, since Marxism–Leninism at that time preferred autarchy in the economy (and the practice of the USSR exactly followed this model, although Greenberg as a Trotskyist of course rejected the Stalinist form of socialism). This Trotskyist–Marxist underpinning is evident in “Towards a Newer Laocoon”: “I find that I have offered no other explanation for the present superiority of abstract art than its historical justification” (Greenberg [1940] 1988, p. 37). As Clark (1982) underlined, Greenberg tried to justify the emergence of the avant-garde as a form of saving bourgeois culture from its own decay. The unfolding of purity and medial reflexivity in art is not an abstract, immanent process of the history of art, but a result of social and political circumstances (see also Guilbaut 1980). The avant-garde, although itself a product of bourgeois society, that is, capitalism, saves culture from the mass culture of Kitsch: Greenberg’s Laocoon Moment was the (at least alleged) crisis of bourgeois society in the 20th century and the hope that avant-garde culture could preserve at least some form of culture.4

3. Digital Modernism

What is somewhat absent from Greenberg’s approach, although he explicitly mentions the “advances in science and industry” (Greenberg [1939] 1988, p. 22), is the role of changing technical media. As he was a Trotskyist (and therefore as a materialist), one would expect him to have been aware firstly of the material underpinnings of cultural production (and what else is his emphasis on the “medium”?) and secondly on the role of photography and cinema in Soviet art of the 1920s. There are traces of this. For example, in “Towards a Newer Laocoon” he surprisingly writes: “If the poem, as Valéry claims, is a machine to produce the emotion of poetry, the painting and statue are machines to produce the emotion of ‘plastic sight’” (Greenberg [1940] 1988, p. 34). This comparison of classical arts to machines can be read as a kind of Freudian slip pointing to the emerging role of technological media (in the stricter sense) since the 19th century, which had begun to extend and redefine the range of artistic media. If we come back to Greenberg’s idea that there might be a dominant medium, is it really still music in the second half of the 20th century? Are there not new “machines”—like photography,5 cinema, television, video—and finally the computer? One could argue that the dominant medium in the field of art is not identical to the medium (or the media) that dominates the rest of society. In this light it is important that Greenberg criticizes Kitsch as being “mechanical” (Greenberg [1939] 1988, pp. 12–13: “mechanically”), stating that “Kitsch is a product of the industrial revolution” (11). There seems to be a certain anti-technical stance in Greenberg6 that became more and more incompatible with the changes in the art world in the 1960s. Internal problems of the Greenberg paradigm aside,7 new technologies appeared in the art scene—especially video—which, according to Rosalind Krauss (1999a, p. 30), caused the concept of media reflexivity as the basis of art to disappear because media like video were involved in practices that were too disparate. Thus, in the 1970s and 1980s, forms of art flourished that broke with any media-reflexive purism and instead worked with multi- and intermedial strategies—often in the form of “installations”: “As is typical of what has come to be called postmodernism, this […] work is not confined to any particular medium” (Crimp 1979, p. 75; Greenberg 1981 was unsurprisingly critical of this development). As a result, Greenberg’s role as a critic declined, and even his early follower Rosalind Krauss proclaimed a “post-medium condition” (Krauss 1999a). From today’s perspective, Greenberg’s insistence on the medium seems to be “hopelessly outdated” (Rebentisch 2021, p. 124; translation by the author).8 In a way, the “advances in science and industry” (Greenberg [1939] 1988, p. 22) disrupted Greenberg’s paradigm—so it seems. Or as he put it himself in an again somewhat drastic and political way: “The scene of visual art has been invaded more and more, lately, by other mediums than those of painting or sculpture” (Greenberg 1981, p. 92; emphasis by the author).

After the collapse of the Greenberg paradigm, it comes unexpected that media reflexivity is again playing a certain, if not important, role among newer artists. Juliane Rebentisch notes “that in intermedial contemporary art […] the knowledgeable reference to the various traditions of the arts and the possibilities of their media […] plays an important role” (Rebentisch 2013, p. 105; translation by the author).9 Interestingly, only one page earlier she points out that the “role of technologies and new media in this context should not be underestimated”, especially with regard to the “thematization of older means of representation in newer ones (painting in film), for example” (104; translation by the author). It seems that especially artists operating in the “medium of digitality” (104; translation by the author)10 are paying attention to these questions again.

Almost at the same time as the Greenberg paradigm seemed to vanish from art (in the mid-1960s), in the very first experiments with the computer as a medium, Greenbergian questions were raised anew. A. Michael Noll’s text “The Digital Computer as a Creative Medium” from 1967 (Noll 1967a; see also Noll 1967b) is one example of this. Given the inherited and still influential role of Greenbergian concepts,11 in order to identify a practice with computers as artistic, it was necessary to reflect on a medium, and therefore, the computer was described as just that. Noll argues similarly to Greenberg: “The resistance of the canvas or its elastic give to the paint-loaded brush, the visual shock of real color and line, the smell of the paint, will all work on the artist’s sensibilities. […] So it is that an artist explores, discovers, and masters the possibilities of the medium” (Noll 1967a, p. 90; see again Greenberg ([1940] 1988, p. 34) on resistance of the medium).

The question then follows what possibilities and resistances the medium of the computer unfolds in artistic work, because “computers are a new medium. They do not have the characteristics of paint, brushes, and canvas” (Noll 1967a, p. 90; emphasis in the source). Noll notes that what is new about the computer is the ability to mathematically model (approximately and partially) the specific processes that characterize other media in general. To the extent that the computer is used to simulate traditional media, it appears as a medium itself. The artistic practice that provided the model for the concept of the computer as an artistic medium was abstract painting—the title page of Noll’s text is adorned by a graphic that is at least vaguely reminiscent of Bridget Riley’s Op-Art. Certainly, for experiments with computers, especially in the 1960s, when the possibilities of computer graphics were limited (limitations of the medium, so to speak), recourse to geometric-constructive variants of abstract painting are obvious, since these are relatively easy to formalize and display.12

Noll’s question was whether it is possible to mathematically generate works of art based on the formalization of existing works. An example of this is that he presented one real and one mathematically simulated Mondrian and asked a (non-representative) sample of viewers which was the real Mondrian. The majority of viewers thought the computer image was the real Mondrian—ergo, the simulation of the painterliness of painting seemed successful (although one can doubt this proof of “artiness” of these examples of computer art). Noll’s and similar ideas (by Frieder Nake and many others) as a whole refer to a fundamental property of the medium computer, namely to be able to approximately and partially imitate all other media—either by measuring and simulating the properties of the technical dispositif (as later in what were called “photorealist computer graphics” for example; see Bouatouch and Bouville 1992) or by sampling the signals of different media (sounds, images, etc.) and using them as material. Noll’s experiment in what was a little later referred to as “information aesthetics” (Nake 2012) might not have been successful in the sense that this became a central new form of art. But it pointed to the transformations that the inherent complexity of the “medium” was undergoing through the “advances in science and industry”, as Greenberg put it (Greenberg [1939] 1988, p. 22). Greenberg’s above-mentioned “second variant” of the avant-garde—“[e]ach art would demonstrate its powers by capturing the effects of its sister arts or by taking a sister art for its subject” (Greenberg [1940] 1988, p. 30)—is again becoming a possibility with computers.

With digital media, a kind of “digital modernism” becomes possible, in which media can be envisioned anew, simulating but also transforming them, while at the same time exploring the possibilities of the underlying computational infrastructure. If Greenberg is right that music was the structural model for modernist painting, we might now say that the computer becomes a new model—at least partially. For example, Thomas Ruff remarks with regard to his digitally processed porn photos from the Internet, the Nudes: “If I work with a certain medium, then I also want to reflect this medium in the picture” (Ruff 1999, p. 75; translation by the author).13 Ruff’s Nudes reflect on what digitalized, sampled photography means under the conditions of the Internet, what the economies of circulation are, which visual patterns repeat, how the indexical link connecting the image to sexual practices is necessary or not for a phantasmatic economy of desire, how the intentionally blurred pictures relate to painterly aesthetics but also to questions of visibility, invisibility and censorship, etc. In the preface to his book net.art 2.0 from 2001, Tilman Baumgärtel explicitly refers to Greenberg to legitimize the artistic status of “net art” via its self-reflexive procedures: “There are several attributes of Net art [sic] comparable to ‘flatness’ for painting […]: globality, connectedness, immateriality, interactivity, equality and multimedia” (Baumgärtel 2001, p. 27: emphasis by the author). Interestingly enough, and reminiscent of the complexities of the medium as discussed above, “multimediality” is a medium-specificity of net art, according to Baumgärtel. “Greenberg’s principles can be applied so easily to an art that has so little to do with the paintings he preferred because every sort of art is also media art” (27). The computer becomes the structural model of every art. In line with this is Rebentisch’s assessment (Rebentisch 2013, p. 106) that despite all intermedial transgression, “the sometimes more, sometimes less stable fields of the traditional arts” (Rebentisch 2013, p. 103; translation by the author)14 still exist. This should not be seen as a kind of regressive left-over; it just shows that Greenberg’s idea that there are different variants of media-reflexive art might still be valid (besides forms of art that have very different, e.g., political, interests—and to draw this border is a political gesture in itself). In times of digital possibilities, it might still be interesting to ask what painting can achieve, e.g., compared to painterly strategies with digital imaging. Pollock constructed examples for specific painting—today examples for specific digital artworks are constructed, as is argued by Ruff, Baumgärtel and many others.

Greenberg’s idea of the medium also reappeared in theoretical discourse. In Rosalind Krauss’s work, it has received a critical appraisal insofar as she emphasizes the necessity “to reclaim the specific from the deadening embrace of the general” (Krauss 1999b, p. 305).15 She sees in the work of James Coleman, William Kentridge and others the effort to “reinvent” a specific medium by recourse to media-historically obsolete techniques (slide show in Coleman’s case; drawn animation, 16 mm film in Kentridge’s), but in a way that emphasizes the “differential” character of the medium, meaning that a medium is not only a material of a certain kind, but a historically sedimented layering of conventions (Krauss 1999a, p. 53; 2000). Moreover: the “medium” of Coleman and Kentridge is, again, in itself multimedial—sound and images.

The Laocoon Moment of the 1960s onwards is the intrusion of new technologies, like video or the computer, into the artistic field, which disrupts older notions of medium specificity, but not to do away with it altogether, but to reinvent the “medium” over and over again.16 In that sense, Lessing’s drawing of borders is still and unavoidably with us.

4. The Politics of Digital Modernism Today: One Example

The questions Lessing posed in his Laokoon are still relevant. There is no linear progression from the paradigm of medium specificity to an inter- or multimedial plurality, but both tendencies coexist—as they did in the past, too17—even if relative dominance might vary. The question of how to draw borders between different arts and media and how to transgress them (which presupposes borders) becomes especially relevant in an epoch in which ever new technologies based on the computer emerge and are soon used artistically. In each case, the question of the new “medium’s” specificity—compared to other media—is posed anew. And as suggested above, a newly invented “medium” can be itself a multimedial entity, pointing again to the complexity of the medium and its relations to other media and multimedia.

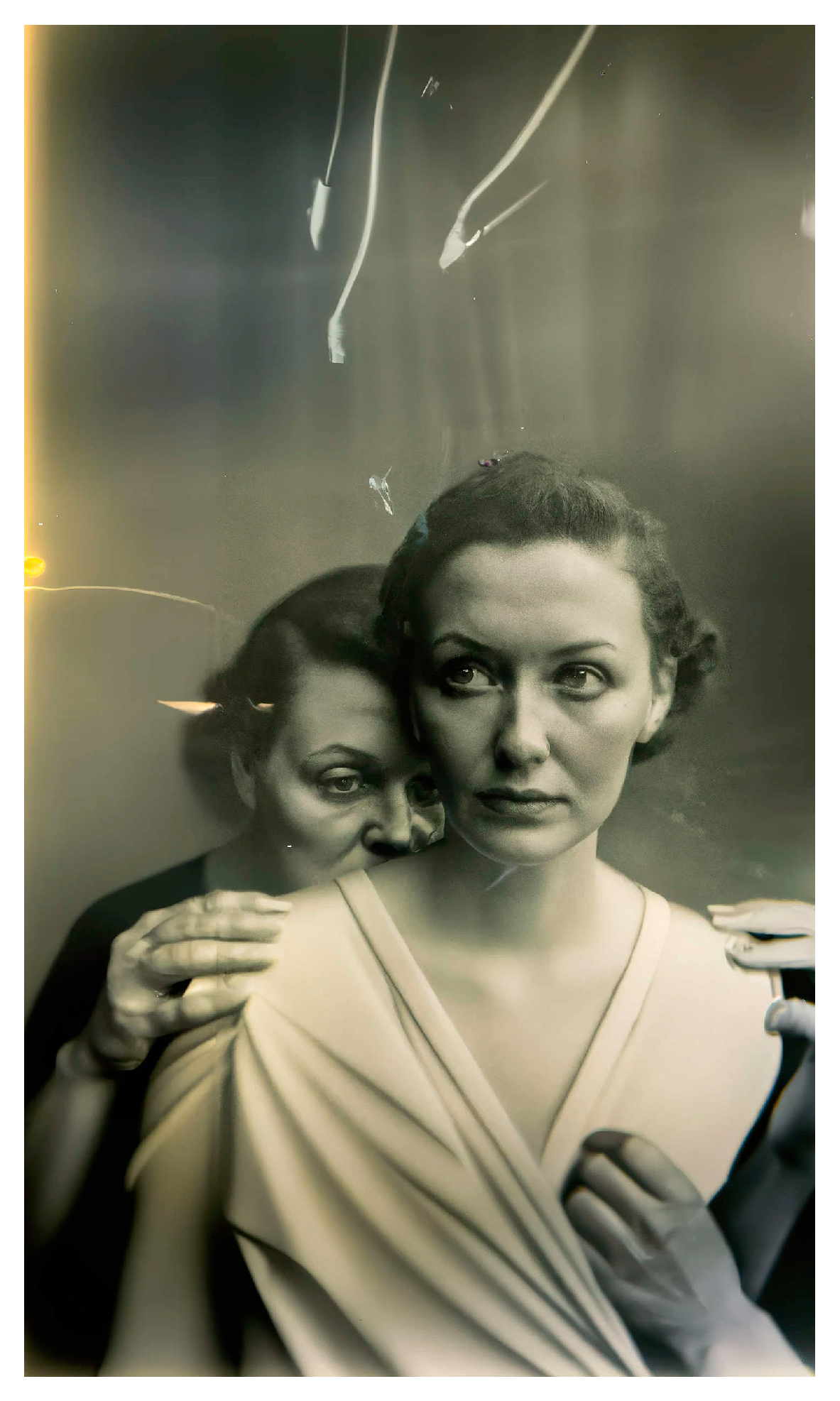

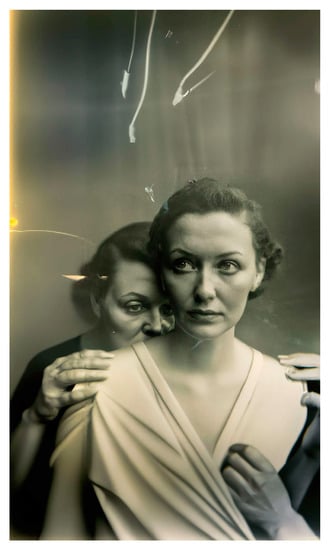

An interesting example is the recent and somewhat excited discussion on “Artificial Intelligence-generated pictures”. Generated with software like Dall-E, Stable Diffusion or Midjourney18 from huge databases of publicly available images, these images often resemble strange, dreamlike photographs with certain little bizarre aberrations. The generation process is started—in a surprising reversal of “ut pictura poesis”—by making a textual “prompt”. The widespread diffusion of these images in recent times revived the seemingly never-ending discussion of what photography really “is”: The Berlin-based photographer Boris Eldagsen just started that debate again by turning in an AI-based image (called “The Electrician”, see Figure 1) in a prestigious photography contest and winning a prize for it, which he rejected. He argued that he wanted to ask what AI images are in contrast to photography (see https://www.eldagsen.com (accessed 9 August 2023)). A new medium was even postulated: promptography. This is, again, a question of medium specificity: AI-based images seem to have their specificity in their statistical character, as contrasted to simulated photorealism in computer graphics or to the indexical image of photography (Meyer 2022).

Figure 1.

Boris Eldagsen, PSEUDOMNESIA | The Electrician, 2022, courtesy of Photo Edition Berlin. Reprinted with permission of the artist.

With such artistic interventions, the questions of media borders and their implications are posed again. And moreover, in the same movement, the computational medium is examined—it is not innocent, just as Mitchell argued that Lessing’s basic categories are not innocent. Data are not innocent. What are the datasets from which AI-based images are generated? How are copyrights violated by including artists’ images in the databases? How are these databases biased? How are the images to be situated in the problematic (colonial) history of statistics? What are the politics of reference in a world flooded with statistically generated images (besides Photoshop manipulation, photorealist computer graphics, and finally, photographs)? If it is at all possible, how can we discriminate photography from its many simulations and re-creations? Even Greenberg’s early Marxist19 tendencies seem to still be relevant since the diffusion and expansion of digital technologies cannot be separated from their historical and contemporary implications in “digital capitalism” (see among many others Betancourt 2015). The questions of capitalist accumulation are of central relevance for digital culture accumulating huge amounts of data that then can become the base for new forms of images like AI-based images. Their emergence would have been impossible without the accumulation of data by big social media companies. Drawing borders between AI-based images and photography—think of the example of Ruff’s Nudes or Baumgärtel’s net art mentioned above—invokes questions of, to put it in Greenberg’s terms (Greenberg [1940] 1988, p. 32), “free trade” and “autarchy”: on one hand, there is the (oh so) free20 circulation of images used for excessive profit accumulation of big platform companies. At the same time, there is autarchy in the secrecy and opacity of the algorithms used. We find a free crossing of media boundaries on the surface of digital technologies while the software companies enclose and veil their sources of data, their algorithms, etc. Artistic strategies today, regardless of in which medium or in which multimedial assemblage they are used, will need to reflect on this situation.

The Laocoon Moment is still with us—and will be renewed in every moment.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | When I speak of “arts” and “media”, I shorten a complex discussion, especially since the centrality of the notion of “medium” is a product of the 20th century (but see my discussion on Greenberg below). “Arts” are the wider, often institutionalized, uses of media for artistic purposes, while media are basically materials, technologies and their sedimented conventions used for these artistic purposes. |

| 2 | The Paragone had another political level, too—it was about the question of justifying the visual arts as artes liberals and so to give art forms like paintings or sculptures, and therefore the labor of artists, a higher and more respected rank overall. There is plenty of literature on the Paragone; see (Schnitzler 2007) for trying to relate it to the 20th century; see also Lippert (2019, pp. 1–24). |

| 3 | Greenberg senses a potential self-contradiction on this point: “That music at this point imitates literature would seem to spoil my thesis” (Greenberg [1940] 1988, pp. 30–31). |

| 4 | There is another layer of political implications here. The painting of Pollock and others, labeled as “Abstract Expressionism”, was, as Cockroft (1974) has famously shown, also a weapon in the ideological Cold War—but only in an anti-Greenbergian way, since it was about understanding, for example, Pollock’s painting as “expression” (of “free subjectivity” in an existentialist spirit) and not mainly as media reflexivity. Therefore, Greenberg’s critique of the reduction of painting to a channel of expression in romanticism was contradicted in an unexpected way. |

| 5 | Actually, Rosalind Krauss (1999b, p. 292) has argued—with reference to Walter Benjamin—that photography became the dominant medium in the 20th century: “As a theoretical object, photography assumes the revelatory power to set forth the reasons for a wholesale transformation of art that will include itself in that same transformation”. |

| 6 | In the Collected Essays there are only two essays on photography and some more mentions (which I cannot discuss here in detail), but nothing on cinema or on video (video could be expected in Vol. 4, covering 1957–1969, but it cannot be found in the index). In one of his papers on photography, a review of an exhibition by Edward Weston, he describes photography as a “relatively mechanical and neutral […] medium” (Greenberg [1946] 1988, p. 61). He criticizes Weston’s approach for producing “a hard, mechanical effect that seems contrived and without spontaneity” (61). Here we can see again that the “mechanical” is a problem for Greenberg, continuing an older tradition in which the technical, automatic, mechanical procedures of media like photography (and others) are viewed with a certain suspicion. This essay on Weston is also interesting in other ways, since he not only allows, but even demands, that photography—in stark contrast to his musings on painting—should follow literature as a paradigm (63; remember his remarks on the literary in music mentioned above). He even criticizes Weston for “excessive concentration on the medium” (63), as if there were no specificity of the photographic medium worth being used—or being constructed in exemplary artistic experiments. |

| 7 | Greenberg’s program of a self-reflexive purification of painting and other art forms gradually became immanently problematic in the early 1960s, for soon the self-analytical reduction of painting threatened to cross the boundary beyond which “a picture stops being a picture and turns into an arbitrary object”, and which Greenberg had called not to cross but “to be observed and indicated” (Greenberg [1960] 1995, p. 90). Ultimately, new developments such as Minimal Art emerged that shifted the emphasis away from media specificity (Judd 1965) and seemed to produce such “arbitrary objects”; Judd called them “specific objects”. |

| 8 | Original: “[H]offnungslos veraltet”. |

| 9 | Original: “[I]ntermediale[n] Gegenwartskunst […] der kenntnisreiche Bezug auf die verschiedenen Traditionen der Künste und die Möglichkeiten ihrer Medien […] eine wichtige Rolle”. |

| 10 | Original: “Rolle der Technologien und neuen Medien in diesem Zusammenhang nicht zu unterschätzen”; “Thematisierung älterer Darstellungsmittel in neueren (der Malerei im Film) beispielsweise”; “Medium der Digitalität”. |

| 11 | Cf. (Krauss 1999a, p. 6): “[F]rom the 60s on, to utter the word ‘medium’ meant invoking ‘Greenberg’ […]”. Whether Noll, as a computer scientist, was familiar with this discourse, however, must remain open. At nearly the same time, early media theory discovers the computer as a medium too: McLuhan (1964, p. 43) described the “media of communication from speech to computer”. Groys (2000, pp. 73–79) underlined that McLuhan’s media theory was actually inspired by Greenberg’s modernism and his insistence on the medium. |

| 12 | There is, as far as I can see, only one mention of computer art in Greenberg ([1969] 1995 p. 294)—Greenberg criticizes the geometricisim of all new art forms in the 1960s. There is no specific discussion of art based on computers. |

| 13 | Original: “Wenn ich mit einem bestimmten Medium arbeite, dann will ich dieses Medium auch im Bild reflektieren”. |

| 14 | Original: “[D]ie mal mehr, mal weniger stabilen Felder der traditionellen Künste”. |

| 15 | The “deadly” character of the generic, as Krauss puts it in citing Thierry de Duve’s conceptual pair of the specific (reference to the medium) and the generic (reference to the question “what is art?”) lies in the fact, according to Krauss, that anything can appear as art at will (see as the paradigmatic example of Duchamp’s readymades), and thus with the disappearance of the specific in art, the specificity of art is also at risk of collapsing. On this, see Rebentisch (2013, pp. 106–16). |

| 16 | As Groys (2000 p. 74) puts it: “This search for the sincerity of the medial continued in the advanced art of the twentieth century; it also continued throughout the epochs of multimediality and so-called postmodernity”. |

| 17 | The dominance of modernism after 1945 made alternative approaches already existing at that time invisible. Later, the dominance of inter- and multimedial approaches concealed artistic strategies still relying on the medium—but the sheer importance of painting on the art market, at the latest having a revival in the 1980s with, let us say, “new wild painting”, should make us aware of how important classical arts (and their media) still are, even if they no longer follow a Greenbergian program of abstraction and reduction. Regarding this, questions of the critical and academic constructions of the history of art become relevant (other, and perhaps more important, examples are the exclusion of women or art from the Global South from the history of art). |

| 18 | See https://openai.com/product/dall-e-2; https://stablediffusionweb.com; https://www.midjourney.com (accessed 9 August 2023). |

| 19 | The Trotkyist aspects will be ignored here since that political current is mostly obsolete today. But Marx’s critique of political economy is still relevant and even became more important after the great financial crisis of 2008. |

| 20 | Besides questions of filtering image circulations in social media, censorship, exclusion of parts of the world, etc. |

References

- Arnheim, Rudolf, ed. 2006. A New Laocoön: Artistic Composites and the Talking Film. In Film as Art, 12th ed. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, pp. 199–230. First published 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Babbitt, Irving. 1910. The New Laokoon. An Essay on the Confusion of the Arts. Boston and New York: Houghton Miflin Company. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgärtel, Tilman. 2001. [net.art 2.0] Neue Materialien zur Netzkunst. Nürnberg: Verlag für moderne Kunst. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt, Michael. 2015. The Critique of Digital Capitalism. An Analysis of the Political Economy of Digital Culture and Technology. Brooklyn: Punctum Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bouatouch, Kadi, and Christian Bouville, eds. 1992. Photorealism in Computer Graphics. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Burwick, Frederick, ed. 1999. Lessing’s Laokoon: Context and Reception. Poetics Today 20. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Timothy James. 1982. Clement Greenberg’s Theory of Art. Critical Inquiry 9: 139–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockroft, Eva. 1974. Abstract Expressionism. Weapon of the Cold War. Artforum XII: 39–41. [Google Scholar]

- Crimp, Douglas. 1979. Pictures. October 8: 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1988. Avant-Garde and Kitsch. In The Collected Essays and Criticism. Vol. 1: Perceptions and Judgements, 1939–1944. Edited by John O’Brian. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, pp. 5–22. First published 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1988. The Camera’s Glass Eye. Review of an Exhibition of Edward Weston. In The Collected Essays and Criticism. Vol. 2: Arrogant Purpose, 1945–1949. Edited by John O’Brian. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, pp. 60–63. First published 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1988. Towards a Newer Laocoon. In The Collected Essays and Criticism. Vol. 1: Perceptions and Judgements, 1939–1944. Edited by John O’Brian. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, pp. 23–38. First published 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1995. Avant-Garde Attitudes. New Art in the Sixties. In The Collected Essays and Criticism. Vol. 4: Modernism with a Vegeance, 1957–1969. Edited by John O’Brian. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, pp. 292–303. First published 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1995. Modernist Painting. In The Collected Essays and Criticism. Vol. 4: Modernism with a Vegeance, 1957–1969. Edited by John O’Brian. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, pp. 85–93. First published 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, Clement. 1981. Intermedia. Arts Magazine 56: 92–93. [Google Scholar]

- Groys, Boris. 2000. Under Suspicion. A Phenomenology of Media. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guilbaut, Serge. 1980. The New Adventures of the Avant-Garde in America: Greenberg, Pollock, or from Trotskyism to the New Liberalism of the ‘Vital Center’. October 15: 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, Susan E. 1995. Absent Mothers and Orphaned Fathers: Narcissim and Abjection in Lessing’s Aesthetic and Dramatic Production. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Judd, Donald. 1965. Specific Objects. Arts Yearbook 8: 74–82. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss, Rosalind. 1999a. ‘A Voyage on the North Sea’. Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition. New York: Thames & Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss, Rosalind. 1999b. Reinventing the Medium. Critical Inquiry 25: 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, Rosalind. 2000. ‘The Rock’. William Kentridge’s Drawings for Projection. October 92: 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessing, Gotthold Ephraim. 1836. Laocoon or the Limits of Poetry and Painting. London: J. Ridgway & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Lippert, Sarah J. 2019. The Paragone in Nineteenth Century Art. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McLuhan, Marshall. 1964. Understanding Media. The Extensions of Man. London and New York: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Roland. 2022. Im Bildraum von Big Data. Unwahrscheinliche und unvorhergesehene Suchkommandos: Über Dall-E 2. Cargo 55: 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, William J. T. 1986. The Politics of Genre: Space and Time in Lessing’s Laocoon. Representations 6: 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nake, Frieder. 2012. Information Aesthetics: An Heroic Experiment. Journal of Mathematics and the Arts 6: 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, Michael. 1967a. The Digital Computer as a Creative Medium. IEEE Spectrum 4: 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noll, Michael. 1967b. Computers and the Visual Arts. Design Quarterly 66/67: 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebentisch, Juliane. 2013. Theorien der Gegenwartskunst zu Einführung. Hamburg: Junius. [Google Scholar]

- Rebentisch, Juliane. 2021. Singularität, Gattung, Form. In Die Kunst und die Künste. Ein Kompendium zur Kunsttheorie der Gegenwart. Edited by Georg W. Bertram, Stefan Deines and Daniel Martin Feige. Berlin: Suhrkamp, pp. 123–37. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, Simon. 1999. Intimate Relations: Music in and around Lessing’s Laokoon. Poetics Today 20: 155–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ruff, Thomas. 1999. Suchmaschinen. Ein Interview von Susanne Leeb. Texte zur Kunst 36: 71–75. [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler, Andreas. 2007. Der Wettstreit der Künste. Die Relevanz der Paragone-Frage im 20. Jahrhundert. Berlin: Reimer. [Google Scholar]

- Schröter, Jens. 2010. The Politics of Intermediality. Acta Univ. Sapientiae, Film and Media Studies 2: 107–24. [Google Scholar]

- Schröter, Jens. 2012. Four Models of Intermediality. In Travels in Intermediality. Edited by Bernd Herzogenrath. Hanover and New Hampshire: Dartmouth College Press, pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wellbery, David. 1984. Lessing’s Laocoon. Semiotics and Aesthetics in the Age of Reason. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).